- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

The Effects of Drug Addiction on the Brain and Body

Signs of drug addiction, effects of drug addiction.

Drug addiction is a treatable, chronic medical disease that involves complex interactions between a person’s environment, brain circuits, genetics, and life experiences.

People with drug addictions continue to use drugs compulsively, despite the negative effects.

Substance abuse has many potential consequences, including overdose and death. Learn about the effects of drug addiction on the mind and body and treatment options that can help.

Verywell / Theresa Chiechi

Drug Abuse vs. Drug Addiction

While the terms “drug abuse” and “drug addiction” are often used interchangeably, they're different. Someone who abuses drugs uses a substance too much, too frequently, or in otherwise unhealthy ways. However, they ultimately have control over their substance use.

Someone with a drug addiction uses drugs in a way that affects many parts of their life and causes major disruptions. They can't stop using drugs, even if they want to.

The signs of drug abuse and addiction include changes in behavior, personality, and physical appearance. If you’re concerned about a loved one’s substance use, here are some of the red flags to watch out for:

- Changes in school or work performance

- Secretiveness

- Relationship problems

- Risk-taking behavior

- Legal problems

- Aggression

- Mood swings

- Changes in hobbies or friends

- Sudden weight loss or gain

- Unexplained odors on the body or clothing

Drug Addiction in Men and Women

Men and women are equally likely to develop drug addictions. However, men are more likely than women to use illicit drugs, die from a drug overdose, and visit an emergency room for addiction-related health reasons. Women are more susceptible to intense cravings and repeated relapses.

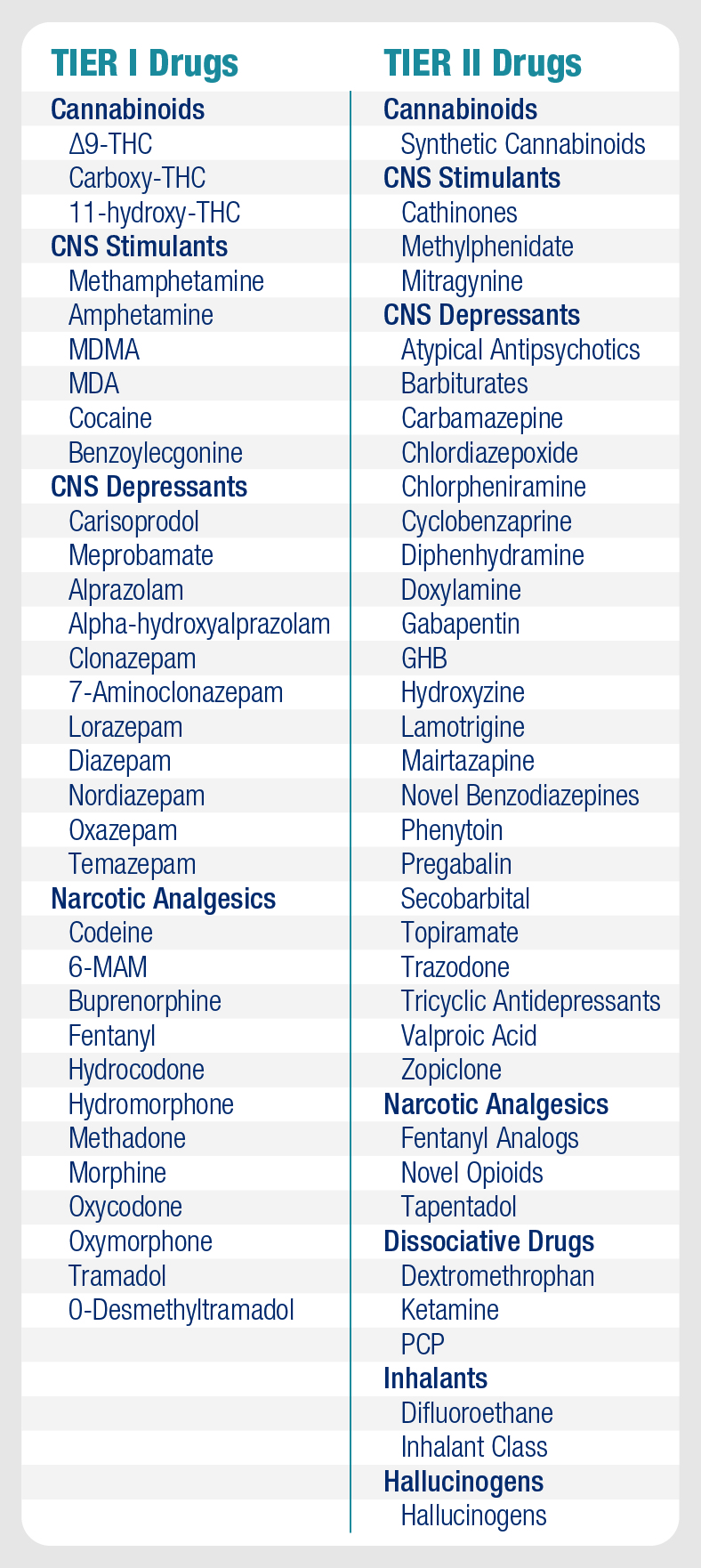

People can become addicted to any psychoactive ("mind-altering") substance. Common addictive substances include alcohol , tobacco ( nicotine ), stimulants, hallucinogens, and opioids .

Many of the effects of drug addiction are similar, no matter what substance someone uses. The following are some of the most common effects of drug addiction.

Effects of Drug Addiction on the Body

Drug addiction can lead to a variety of physical consequences ranging in seriousness from drowsiness to organ damage and death:

- Shallow breathing

- Elevated body temperature

- Rapid heart rate

- Increased blood pressure

- Impaired coordination and slurred speech

- Decreased or increased appetite

- Tooth decay

- Skin damage

- Sexual dysfunction

- Infertility

- Kidney damage

- Liver damage and cirrhosis

- Various forms of cancer

- Cardiovascular problems

- Lung problems

- Overdose and death

If left untreated drug addiction can lead to serious, life-altering effects on the body.

Dependence and withdrawal also affect the body:

- Physical dependence : Refers to the reliance on a substance to function day to day. People can become physically dependent on a substance fairly quickly. Dependence does not always mean someone is addicted, but the longer someone uses drugs, the more likely their dependency is to become an addiction.

- Withdrawal : When someone with a dependence stops using a drug, they can experience withdrawal symptoms like excessive sweating, tremors, panic, difficulty breathing, fatigue , irritability, and flu-like symptoms.

Overdose Deaths in the United States

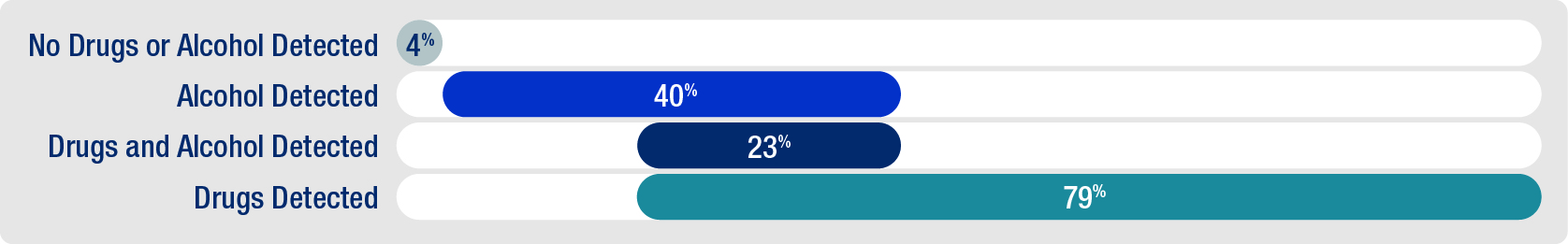

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), over 100,000 people in the U.S. died from a drug overdose in 2021.

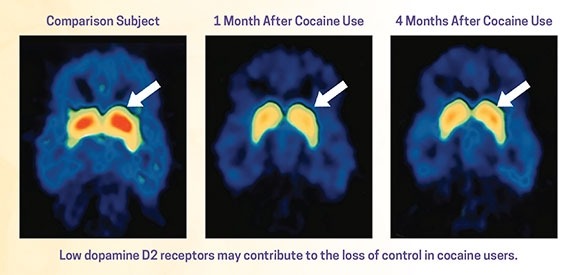

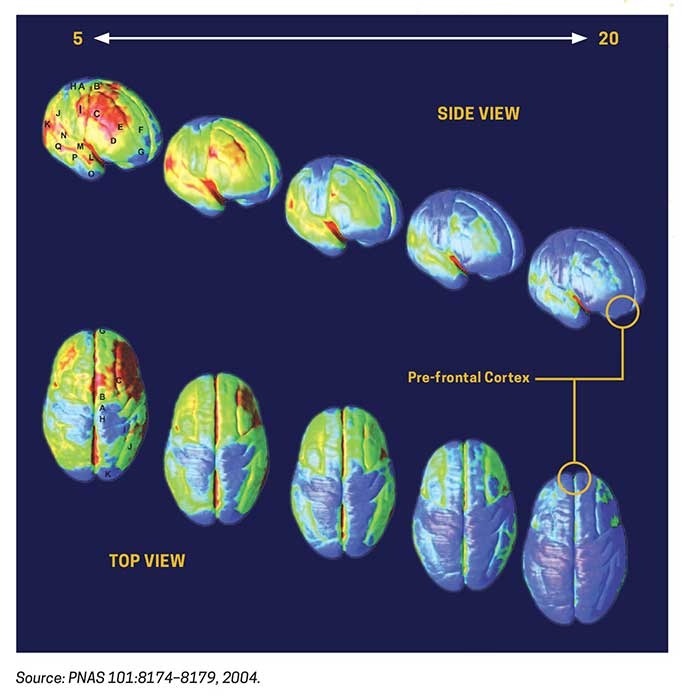

Effects of Drug Addiction on the Brain

All basic functions in the body are regulated by the brain. But, more than that, your brain is who you are. It controls how you interpret and respond to life experiences and the ways you behave as a result of undergoing those experiences.

Drugs alter important areas of the brain. When someone continues to use drugs, their health can deteriorate both psychologically and neurologically.

Some of the most common mental effects of drug addiction are:

- Cognitive decline

- Memory loss

- Mood changes and paranoia

- Poor self/impulse control

- Disruption to areas of the brain controlling basic functions (heart rate, breathing, sleep, etc.)

Effects of Drug Addiction on Behavior

Psychoactive substances affect the parts of the brain that involve reward, pleasure, and risk. They produce a sense of euphoria and well-being by flooding the brain with dopamine .

This leads people to compulsively use drugs in search of another euphoric “high.” The consequences of these neurological changes can be either temporary or permanent.

- Difficulty concentrating

- Irritability

- Angry outbursts

- Lack of inhibition

- Decreased pleasure/enjoyment in daily life (e.g., eating, socializing, and sex)

- Hallucinations

Help Someone With Drug Addiction

If you suspect that a loved one is experiencing drug addiction, address your concerns honestly, non-confrontationally, and without judgment. Focus on building trust and maintaining an open line of communication while setting healthy boundaries to keep yourself and others safe. If you need help, contact the SAMHSA National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357.

Effects of Drug Addiction on an Unborn Child

Drug addiction during pregnancy can cause serious negative outcomes for both mother and child, including:

- Preterm birth

- Maternal mortality

Drug addiction during pregnancy can lead to neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) . Essentially, the baby goes into withdrawal after birth. Symptoms of NAS differ depending on which drug has been used but can include:

- Excessive crying

- Sleeping and feeding issues

Children exposed to drugs before birth may go on to develop issues with behavior, attention, and thinking. It's unclear whether prenatal drug exposure continues to affect behavior and the brain beyond adolescence.

While there is no single “cure” for drug addiction, there are ways to treat it. Treatment can help you control your addiction and stay drug-free. The primary methods of treating drug addiction include:

- Psychotherapy : Psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or family therapy , can help someone with a drug addiction develop healthier ways of thinking and behaving.

- Behavioral therapy : Common behavioral therapies for drug addiction include motivational enhancement therapy (MET) and contingency management (CM). These therapy approaches build coping skills and provide positive reinforcement.

- Medication : Certain prescribed medications help to ease withdrawal symptoms. Some examples are naltrexone (for alcohol), bupropion (for nicotine), and methadone (for opioids).

- Hospitalization : Some people with drug addiction might need to be hospitalized to detox from a substance before beginning long-term treatment.

- Support groups : Peer support and self-help groups, such as 12-step programs like Alcoholics Anonymous, can help people with drug addictions find support, resources, and accountability.

A combination of medication and behavioral therapy has been found to have the highest success rates in preventing relapse and promoting recovery. Forming an individualized treatment plan with your healthcare provider's help is likely to be the most effective approach.

Drug addiction is a complex, chronic medical disease that causes someone to compulsively use psychoactive substances despite the negative consequences.

Some effects of drug abuse and addiction include changes in appetite, mood, and sleep patterns. More serious health issues such as cognitive decline, major organ damage, overdose, and death are also risks. Addiction to drugs while pregnant can lead to serious outcomes for both mother and child.

Treatment for drug addiction may involve psychotherapy , medication, hospitalization, support groups, or a combination.

If you or someone you know is experiencing substance abuse or addiction, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357.

American Society of Addiction Medicine. Definition of addiction .

HelpGuide.org. Drug Abuse and Addiction .

Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services. Warning signs of drug abuse .

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Sex and gender differences in substance use .

Cleveland Clinic. Drug addiction .

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction Drugs and the Brain .

American Heart Association. Illegal Drugs and Heart Disease .

American Addiction Centers. Get the facts on substance abuse .

Szalavitz M, Rigg KK, Wakeman SE. Drug dependence is not addiction-and it matters . Ann Med . 2021;53(1):1989-1992. doi:10.1080/07853890.2021.1995623

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug overdose deaths in the U.S. top 100,000 annually .

American Psychological Association. Cognition is central to drug addiction .

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Understanding Drug Use and Addiction DrugFacts .

MedlinePlus. Neonatal abstinence syndrome .

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Treatment and recovery .

Grella CE, Stein JA. Remission from substance dependence: differences between individuals in a general population longitudinal survey who do and do not seek help . Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;133(1):146-153. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.019

By Laura Dorwart Dr. Dorwart has a Ph.D. from UC San Diego and is a health journalist interested in mental health, pregnancy, and disability rights.

Violence in Families: Assessing Prevention and Treatment Programs (1998)

Chapter: 9 conclusions and recommendations, 9 conclusions and recommendations.

The problems of child maltreatment, domestic violence, and elder abuse have generated hundreds of separate interventions in social service, health, and law enforcement settings. This array of interventions has been driven by the urgency of the different types of family violence, client needs, and the responses of service providers, advocates, and communities. The interventions now constitute a broad range of institutional services that focus on the identification, treatment, prevention, and deterrence of family violence.

The array of interventions that is currently in place and the dozens of different types of programs and services associated with each intervention represent a valuable body of expertise and experience that is in need of systematic scientific study to inform and guide service design, treatment, prevention, and deterrence. The challenge for the research community, service providers, program sponsors, and policy makers is to develop frameworks to enhance critical analyses of current strategies, interventions, and programs and identify next steps in addressing emerging questions and cross-cutting issues. Many complexities now characterize family violence interventions and challenge the development of rigorous scientific evaluations. These complexities require careful consideration in the development of future research, service improvements, and collaborative efforts between researchers and service providers. Examples of these complexities are illustrative:

- The interventions now in place in communities across the nation focus services on discrete and isolated aspects of family violence. They address different aspects of child maltreatment, domestic violence, and elder abuse. Some

- interventions have an extensive history of experience, and others are at a very early stage of development.

- Many interventions have not been fully implemented because of limited funding or organizational barriers. Thus in many cases it is too early to expect that research can determine whether a particular intervention or strategy (such as deterrence or prevention) is effective because the intervention may not yet have sufficient strength to achieve its intended impact.

- The social and institutional settings of many interventions present important challenges to the design of systematic scientific evaluations. The actual strength or dosage of a particular program can be directly influenced by local or national events that stimulate changes in resources, budgets, and personnel factors that influence its operation in different service settings. Variations in service scope or intensity caused by local service practices and social settings are important sources of "noise" in cross-site research studies; they can directly affect evaluation studies in such key areas as definitions, eligibility criteria, and outcome measures.

- Emerging research on the experiences of family violence victims and offenders suggests that this is a complex population composed of different types of individuals and patterns of behavior. Evaluation studies thus need to consider the types of clients served by particular services, the characteristics of those who benefited from them, and the attributes of those who were resistant to change.

In this chapter the committee summarizes its overall conclusions and proposes policy and research recommendations. A key question for the committee was whether and when the research evidence is sufficient to guide a critical examination of particular interventions. In some areas, the body of research is sufficient to inform policy choices, program development, evaluation research, data collection, and theory-building; the committee makes recommendations for current policies and practices in these areas below. In other areas, although the research base is not yet mature enough to guide policy and program development, some interventions are ready for rigorous evaluation studies. For this second tier of interventions, the committee makes recommendations for the next generation of evaluation studies. The committee then identifies a set of four topics for basic research that reflect current insights into the nature of family violence and trends in family violence interventions. A final section makes some suggestions to increase the effectiveness of collaborations between researchers and service providers.

Conclusions

The committee's conclusions are derived from our analysis of the research literature and discussions with service providers in the workshops and site visits, rather than from specific research studies. This analysis takes a client-oriented

approach to family violence interventions, which means that we focus on how existing services in health, social services, and law enforcement settings affect the individuals who come in contact with them.

- The urgency of the need to respond to the problem of family violence and the paucity of research to guide service interventions have created an environment in which insights from small-scale studies are often adopted into policy and professional practice without sufficient independent replication or reflection on their possible shortcomings. Rigorous evaluations of family violence interventions are confined, for the most part, to small or innovative programs that provide an opportunity to develop a comparison or control study, rather than focusing on the major existing family violence interventions.

- This situation has fostered a series of trial-and-error experiences in which a promising intervention is later found to be problematic when employed with a broader and more varied population. Major treatment and prevention interventions, such as child maltreatment reporting systems, casework, protective orders, and health care for victims of domestic violence, battered women's shelters, and elder abuse interventions of all types, have not been the subjects of rigorous evaluation studies. The programmatic and policy emphasis on single interventions as panaceas to the complex problems of family violence, and the lack of sufficient opportunity for learning more about the service interactions, client characteristics, and contextual factors that could affect the impact of different approaches, constitute formidable challenges to the improvement of the knowledge base and prevention and treatment interventions in this filed.

- In all areas of family violence, after-the-fact services predominate over preventive interventions. For child maltreatment and elder abuse, case identification and investigative services are the primary form of intervention; services designed to prevent, treat, or deter family violence are relatively rare in social service, health, and criminal justice settings (with the notable exceptions of foster care and family preservation services). For domestic violence, interventions designed to treat victims and offenders and deter future incidents of violence are more common, but preventive services remain relatively underdeveloped.

- The current array of family violence interventions (especially in the areas of child maltreatment and elder abuse) is a loosely coupled network of individual programs and services that are highly reactive in nature, focused primarily on the detection of specific cases. It is a system largely driven by events, rather than one that is built on theory, research, and data collection. Interventions are oriented toward the identification of victims and the substantiation and documentation of their experiences, rather than the delivery of recommended services to reduce the incidence and consequences of family violence in the community overall. As a result, enormous resources are invested to develop evidence that certain victims or offenders need treatment, legal action, or other interventions, and comparatively limited funds are available for the treatment and support services themselves—a

- situation that results in lengthy waiting lists, discretionary decisionmaking processes in determining which cases are referred for further action, and extensive variation in a service system's ability to match clients with appropriate interventions.

- The duration and intensity of the mental health and social support services needed to influence behaviors that result from or contribute to family violence may be greater than initially estimated. Family violence treatment and preventive interventions that focus on single incidents and short periods of support services, especially in such areas as parenting skills, mental health, and batterer treatment, may be inadequate to deal with problems that are pervasive, multiple, and chronic. Many programs for victims involve short-term treatment services—less than 6 weeks. Services for offenders are also typically of short duration. Yet research suggests that short-term programs designed to alter violent behavior are often the least likely to succeed, because of the difficulties of changing behavior that has persisted for a period of years and has become part of an established pattern in relationships. Efforts to address fundamental sources of conflict, stress, and violence that occur repeatedly over time within the family environment may require extensive periods of support services to sustain the positive effects achieved in short-term interventions.

- The interactive nature of family violence interventions constitutes a major challenge to the evaluation of interventions because the presence or absence of policies and programs in one domain may directly affect the implementation and outcomes of interventions in another. Research suggests that the risk and protective factors for child maltreatment, domestic violence, and elder abuse interact across multiple levels. The uncoordinated but interactive system of services requires further attention and consideration in future evaluation studies. Such evaluations need to document the presence and absence of services that affect members of the same family unit but offer treatment for specific problems in separate institutions characterized by different service philosophies and resources.

- For example, factors such as court oversight or mandatory referrals may influence individual participation in treatment services and the outcomes associated with such participation. The culture and resources of one agency can influence the quality and timing of services offered by another. Yet little information is available regarding the extent or quality of interventions in a community. Clients who receive multiple interventions (especially children) are often not followed through different service settings. Limited information is available to distinguish key features of innovative interventions from those usually offered in a community; to describe the stages of implementation of specific family violence programs, interventions, or strategies; to explain rates of attrition in the client base; or to capture case characteristics that influence the ways in which clients are selected for specific treatment programs.

- The emergence of secondary prevention interventions specifically targeted to serve children, adults, and communities with characteristics that are

- thought to place them at greater risk of family violence than the general population, along with the increasing emphasis on the need for integration and coordination of services, has the potential to achieve significant benefits. However, the potential of these newer interventions to reduce the need for treatment or other support services over the lifetime of the client has not yet been proven for large populations.

- Secondary preventive interventions, such as those serving children exposed to domestic violence, have the potential to reduce future incidents of family violence and to reduce the existing need for services in such areas as recovery from trauma, substance abuse, juvenile crime, mental health and health care. However, evaluation studies are not yet available to determine the value of preventive interventions for large populations in terms of reduction of the need for treatment or other support services over a client's lifetime.

- The shortage of service resources and the emphasis on reactive, short-term treatment have directed comparatively little attention to interventions for people who have experienced or perpetrated violent behavior but who have not yet been reported or identified as offenders or victims. Efforts to achieve broader systemic collaboration, comprehensive service integration, and proactive interventions require attention to the appropriate balance among enforcement, treatment, and prevention interventions in addressing family violence at both state and national levels. Such efforts also need to be responsive to the particular requirements of diverse ethnic communities with special needs or unique resources that can be mobilized in the development of preventive interventions. Because they extend to a larger population than those currently served by treatment centers, secondary prevention efforts can be expensive; their benefits may not become apparent until many years after the intervention occurs.

- Policy leadership is needed to help integrate family violence treatment, enforcement and support actions, and preventive interventions and also to foster the development of evaluations of comprehensive and cross-problem interventions that have the capacity to consider outcomes beyond reports of future violent behavior.

- Creative research methodologies are also needed to examine the separate and combined effects of cross-problem service strategies (such as the treatment of substance abuse and family violence), follow individuals and families through multiple service interventions and agency settings, and examine factors that may play important mediating roles in determining whether violence will occur or continue (such as the use of social networks and support services and the threat of legal sanctions).

- Most evaluations seek to document whether violent behavior decreased as a result of the intervention, an approach that often inhibits attention to other factors that may play important mediating roles in determining whether violence will occur. The individual victim or offender is the focus of most interventions and

- the unit of analysis in evaluation studies, rather than the family or the community in which the violence occurred.

Integrated approaches have the potential to illuminate the sequences and ways in which different experiences with violence in the family do and do not overlap with each other and with other kinds of violence. This research approach requires time to mature; at present, it is not strong enough to determine the strengths or limitations of strategies that integrate different forms of family violence compared with approaches that focus on specific forms of family violence. Service integration efforts focused on single forms of family violence may have the potential to achieve greater impact than services that disregard the interactive nature of this complex behavior, but this hypothesis also remains unproven.

Recommendations For Current Policies And Practices

It is premature to offer policy recommendations for most family violence interventions in the absence of a research base that consists of well-designed evaluations. However, the committee has identified two areas (home visitation and family preservation services) in which a rigorous set of studies offers important guidance to policy makers and service providers. In four other areas (reporting practices, batterer treatment programs, record keeping, and collaborative law enforcement approaches) the committee has drawn on its judgment and deliberations to encourage policy makers and service providers to take actions that are consistent with the state of the current research base.

These six interventions were selected for particular attention because (1) they are the focus of current policy attention, service evaluation, and program design; (2) a sufficient length of time has elapsed since the introduction of the intervention to allow for appropriate experience with key program components and measurement of outcomes; (3) the intervention has been widely adopted or is under consideration by a large number of communities to warrant its careful analysis; and (4) the intervention has been described and characterized in the research literature (through program summaries or case studies).

Reporting Practices

All 50 states have adopted laws requiring health professionals and other service providers to report suspected child abuse and neglect. Although state laws vary in terms of the types of endangerment and evidentiary standards that warrant a report to child protection authorities, each state has adopted a procedure that requires designated professionals—or, in some states, all adults—to file a report if they believe that a child is a victim of abuse or neglect. Mandatory reporting is thought to enhance early case detection and to increase the likelihood that services will be provided to children in need.

For domestic violence, mandatory reporting requirements for professional groups like health care providers have been adopted by the state of California and are under consideration in several other states. Mandatory reports are seen as a method by which offenders who abuse multiple partners can be identified through the health care community for law enforcement purposes. Early detection is assumed to lead to remedies and interventions that will prevent further abuse by holding the abuser accountable and helping to mitigate the consequences of family violence.

Critics have argued that mandatory reporting requirements may damage the confidentiality of the therapeutic relationship between health professionals and their clients, disregard the knowledge and preferences of the victim regarding appropriate action, potentially increase the danger to victims when sufficient protection and support are not available, and ultimately discourage individuals who wish to seek physical or psychological treatment from contacting and disclosing abuse to health professionals. In many regions, victim support services are not available or the case requires extensive legal documentation to justify treatment for victims, offenders, and families.

For elder abuse, 42 states have mandatory reporting systems. Several states have opted for voluntary systems after conducting studies that considered the advantages and disadvantages of voluntary and mandatory reporting systems, on the grounds that mandatory reports do not achieve significant increases in the detection of elder abuse cases.

In reviewing the research base associated with the relationship between reporting systems and the treatment and prevention of family violence, the committee has observed that no existing evaluation studies can demonstrate the value of mandatory reporting systems compared with voluntary reporting procedures in addressing child maltreatment or domestic violence. For elder abuse, studies suggest that a high level of public and professional awareness and the availability of comprehensive services to identify, treat, and prevent violence is preferable to reporting requirements in improving rates of case detection.

The absence of a research base to support mandatory reporting systems raises questions as to whether they should be recommended for all areas of family violence. The impact of mandatory reporting systems in the area of child maltreatment and elder abuse remains unexamined. The committee therefore suggests that it is important for the states to proceed cautiously at this time and to delay adopting a mandatory reporting system in the area of domestic violence, until the positive and negative impacts of such a system have been rigorously examined in states in which domestic violence reports are now required by law.

Recommendation 1: The committee recommends that states initiate evaluations of their current reporting laws addressing family violence to examine whether and how early case detection leads to improved outcomes for the victims or families and promote changes based on sound research. In

particular, the committee recommends that states refrain from enacting mandatory reporting laws for domestic violence until such systems have been tested and evaluated by research.

In dealing with family violence that involves adults, federal and state government agencies should reconsider the nature and role of compulsory reporting policies. In the committee's view, mandatory reporting systems have some disadvantages in cases involving domestic violence, especially if the victim objects to such reports, if comprehensive community protections and services are not available, and if the victim is able to gain access to therapeutic treatment or support services in the absence of a reporting system.

The dependent status of young children and some elders provides a stronger argument in favor of retaining mandatory reporting requirements where they do exist. However, the effectiveness of reporting requirements depends on the availability of resources and service personnel who can investigate reports and refer cases for appropriate treatment, as well as clear guidelines for processing reports and determining which cases qualify for services. Greater discretion may be advised when the child and family are able to receive therapeutic treatment from health care or other service providers and when community resources are not available to respond appropriately to their cases. The treatment of adolescents especially requires major consideration of the pros and cons of mandatory reporting requirements. Adolescent victims are still in a vulnerable stage of development: they may or may not have the capacity to make informed decisions regarding the extent to which they wish to invoke legal protections in dealing with incidents of family violence in their homes.

Batterer Treatment Programs

Four key questions characterize current policy and research discussions about the efficacy of batterer treatment, one of the most challenging problems in the design of family violence interventions: Is treatment preferable to incarceration, supervised probation, or other forms of court oversight for batterers? Does participation in treatment change offenders' attitudes and behavior and reduce recidivism? Does the effectiveness of treatment depend on its intensity, duration, or the voluntary or compulsory nature of the program? Is treatment what creates change, or is change in behavior reduced by multiple interventions, such as arrest, court monitoring of client participation in treatment services, and victim support services?

Descriptive research studies suggest that there are multiple profiles of batterers, and therefore one generic approach is not appropriate for all offenders. Treatment programs may be helpful in changing abusive behavior when they are part of an overall strategy designed to recognize and reduce violence in a relationship, when the batterer is prepared to learn how to control aggressive impulses, and

when the treatment plan emphasizes victim safety and provides for frequent interactions with treatment staff.

Research on the effectiveness of treatment programs suggests that the majority of subjects who complete court-ordered treatment programs do learn basic cognitive and behavioral principles taught in their course. However, such learning requires appropriate program content and client participation in the program for a sufficient time to complete the necessary training. Very few studies have examined matched groups of violent offenders who are assigned to treatment and control groups or comparison groups (such as incarceration or work-release). As a result, the comparative efficacy of treatment is unknown in reducing future violence. Differing client populations and differing forms of court oversight are particularly problematic factors that inhibit the design of rigorous evaluation studies in this field.

The absence of strong theory and common measures to guide the development of family violence treatment regimens, the heterogeneity of offenders (including patterns of offending and readiness to change) who are the subjects of protective orders or treatment, and low rates of attendance, completion, and enforcement are persistent problems that affect both the evaluation of the interventions and efforts to reduce the violence. A few studies suggest that court oversight does appear to increase completion rates, which have been linked to enhanced victim safety in the area of domestic violence, but increased completion rates have not yet led to a discernible effect on recidivism rates in general.

Further evaluations are needed to examine the outcomes associated with different approaches and programmatic themes (such as cognitive-behavioral principles: issues of power, control, and gender; personal accountability). Completion rates have been used as an interim outcome to measure the success of batterer treatment programs; further studies are needed to determine if completers can be identified readily, if program completion by itself is a critical factor in reducing recidivism, and if participation in a treatment program changes the nature, timing, and severity of future violent behavior.

The current research base is inadequate to identify the conditions under which mandated referrals to batterer treatment programs offer a clear advantage over incarceration or untreated probation supervision in reducing recidivism for the general population of male offenders. Court officials should monitor closely the attendance, participation, and completion rates of offenders who are referred to batterer treatment programs in lieu of more punitive sentences. Treatment staff should inform law enforcement officials of any significant behavior by the offender that might represent a threat to the victim. Mandated treatment referrals may be effective for certain types of batterers, especially if they increase completion rates. The research is inconclusive, however, as to which types of individuals should be referred for treatment rather than more punitive sanctions. In selecting individuals for treatment, attention should be given to client history

(first-time offenders are more likely to benefit), motivation for treatment, and likelihood of completion.

Mandated treatment referrals for batterers do appear to provide benefits to victims, such as intensive surveillance of offenders, an interlude to allow planning for safety and victim support, and greater community awareness of the batterer's behavior. These outcomes may interact to deter and reduce domestic violence in the community, even if a treatment program does not alter the behavior of a particular batterer. Treatment programs that include frequent interactions between staff and victims also provide a means by which staff can help educate victims about danger signals and support them in efforts to obtain greater protection and legal safeguards, if necessary.

Recommendation 2: In the absence of research that demonstrates that a specific model of treatment can reduce violent behavior for many domestic violence offenders, courts need to put in place early warning systems to detect failure to comply with or complete treatment and signs of new abuse or retaliation against victims, as well as to address unintended or inadvertent results that may arise from the referral to or experience with treatment.

Further research evaluation studies are needed to review the outcomes for both offenders and victims associated with program content and levels of intensity in different treatment models. This research will help indicate whether treatment really helps and what mix of services are more helpful than others. Improved research may also help distinguish those victims and offenders for whom particular treatments are most beneficial.

Record Keeping

Since experience with family violence appears to be associated with a wide range of health problems and social service needs, service providers are recognizing the importance of documenting abuse histories in their client case records. The documentation in health and social service records of abuse histories that are self-reported by victims and offenders can help service providers and researchers to determine if appropriate referrals and services have been made and the outcomes associated with their use. The exchange of case records among service providers is essential to the development of comprehensive treatment programs, continuity of care, and appropriate follow-up for individuals and families who appear in a variety of service settings. Such exchanges can help establish greater accountability by service systems for responding to the needs of identifiable victims and offenders; health and social service records can also provide appropriate evidence for legal actions, in both civil and criminal courts and child custody cases.

Research evaluations of service interventions often require the use of anonymous case records. The documentation of family violence in such records will

enhance efforts to improve the quality of evaluations and to understand more about patterns of behavior associated with violent behaviors and victimization experiences. Although documentation of abuse histories can improve evaluations and lead to integrated service responses, such procedures require safeguards so that individuals are not stigmatized or denied therapeutic services on the basis of their case histories. Insurance discrimination, in particular, which may preclude health care coverage if abuse is judged to be a preexisting condition, requires attention to ensure that professional services are not diminished as a result of voluntary disclosures. Creative strategies are needed to support integrated service system reviews of medical, legal, and social service case records in order to enhance the quality and accountability of service responses. Such reviews will need to meet the expectations of privacy and confidentiality of both individual victims and the community, especially in cases in which maltreatment reports are subsequently regarded as unfounded.

Documentation of abuse histories that are voluntarily disclosed by victims or offenders to health care professionals and social service providers must be distinguished from screening efforts designed to trigger such disclosures. The committee recommends screening as a strong candidate for future evaluation studies (see discussion in the next section).

Recommendation 3: The committee recommends that health and social service providers develop safeguards to strengthen their documentation of abuse and histories of family violence in both individual and group records, regardless of whether the abuse is reported to authorities.

The documentation of histories of family violence in health records should be designed to record voluntary disclosures by both victims and offenders and to enhance early and coordinated interventions that can provide a therapeutic response to experiences with abuse or neglect. Safeguards are required, however, to ensure that such documentation does not lead to stigmatization, encourage discriminatory practices, or violate assurances of privacy and confidentiality, especially when individual histories become part of patient group records for health care providers and employers.

Collaborative Law Enforcement Strategies

In the committee's view, collaborative law enforcement strategies that create a web of social control for offenders are an idea worth testing to determine if such efforts can achieve a significant deterrent effect in addressing domestic violence. Collaborative strategies include such efforts as victim support and offender tracking systems designed to increase the likelihood that domestic violence cases will be prosecuted when an arrest has been made, that sanctions and treatment services will be imposed when evidence exists to confirm the charges brought against the offender, and that penalties will be invoked for failure to comply with treatment

conditions. The attraction of collaborative strategies is based on their potential ability to establish multiple interactions with offenders across a large domain of interactions that reinforce social standards in the community and establish penalties for violations of those standards. Creating the deterrent effect, however, requires extensive coordination and reciprocity between victim support and offender monitoring efforts involving diverse sectors of the law enforcement community. These efforts may be difficult to implement and evaluate. Further studies are needed to determine the extent to which improved collaboration among police officers, prosecutors, and judges will lead to improved coordination and stronger sanctions for offenders and a reduction in domestic violence.

The absence of empirical research findings of the results of a collaborative law enforcement approach in addressing domestic violence makes it difficult to compare the costs and benefits of increased agency coordination with those achieved by a single law enforcement strategy (such as arrest) in dealing with different populations of offenders and victims. Even though relatively few cases of arrest are made for any form of family violence, arrest is the most common and most studied form of law enforcement intervention in this area. Research studies conducted in the 1980s on arrest policies in domestic violence cases are the strongest experimental evaluations to date of the role of deterrence in family violence interventions. These experiments indicate that arrest may be effective for some, but not most, batterers in reducing subsequent violence by the offender. Some research studies suggest that arrest may be a deterrent for employed and married individuals (those who have a stake in social conformity) and may lead to an escalation of violence among those who do not, but this observation has not been tested in studies that could specifically examine the impact of arrest in groups that differ in social and economic status. The differing effects (in terms of a reduction of future violence) of arrest for employed/unemployed and married/unmarried individuals raise difficult questions about the reliance of law enforcement officers on arrest as the sole or central component of their response to domestic violence incidents in communities where domestic violence cases are not routinely prosecuted, where sanctions are not imposed by the courts, or where victim support programs are not readily available.

The implementation of proarrest policies and practices that would discriminate according to the risk status of specific groups is challenged by requirements for equal protection under the law. Law enforcement officials cannot tailor arrest policies to the marital or employment status of the suspect or other characteristics that may interact with deterrence efforts. Specialized training efforts may help alleviate the tendency of police officers to arrest both suspect and victim, however, and may alert law enforcement personnel to the need to review both criminal and civil records in determining whether an arrest is advisable in response to a domestic violence case.

Two additional observations merit consideration in examining the deterrent effects of arrest. First, in the research studies conducted thus far, the implementation

of legal sanctions was minimal. Most offenders in the replication studies were not prosecuted once arrested, and limited legal sanctions were imposed on those cases that did receive a hearing. Some researchers concluded that stronger evidence of effectiveness might be obtained from proarrest policies if they are implemented as part of a law enforcement strategy that expands the use of punitive sanctions for offenders—including conviction, sentencing, and intensive supervised probation.

Second is the issue of reciprocity between formal sanctions against the offender and informal support actions for the victims of domestic violence. The effects of proarrest policies may depend on the extent to which victims have access to shelter services and other forms of support, demonstrating the interactive dimensions of community interventions. A mandatory arrest policy, by itself, may be an insufficient deterrent strategy for domestic violence, but its effectiveness may be enhanced by other interventions that represent coordinated law enforcement efforts to deter domestic violence—including the use of protective orders, victim advocates, and special prosecution units. Coordinated efforts may help reduce or prevent domestic violence if they represent a collaborative strategy among police, prosecutors, and judges that improves the certainty of the use of sanctions against batterers.

Recommendation 4: Collaborative strategies among caseworkers, police, prosecutors, and judges are recommended as law enforcement interventions that have the potential to improve the batterer's compliance with treatment as well as the certainty of the use of sanctions in addressing domestic violence.

The impact of single interventions (such as mandatory arrest policies) is difficult to discern in the research literature. Such practices by themselves can neither be recommended nor rejected as effective measures in addressing domestic violence on the basis of existing research studies.

Home Visitation and Family Support Services

Home visitation and family support programs constitute one of the most promising areas of child maltreatment prevention. Studies in this area have experimented with different levels of treatment intensity, duration, and staff expertise. For home visitation, the findings generally support the principle that early intervention with mothers who are at risk of child maltreatment makes a difference in child outcomes. Such interventions may be difficult to implement and maintain over time, however, and their effectiveness depends on the willingness of the parents to participate. Selection criteria for home visitation should be based on a combination of social setting and individual risk factors.

In their current form, home visitation programs have multiple goals, only one of which is the prevention of child abuse and neglect. Home visitation and family

support programs have traditionally been designed to improve parent-child relations with regard to family functioning, child health and safety, nutrition and hygiene, and parenting practices. American home visiting programs are derived from the British system, which relies on public health nurses and is offered on a universal basis to all parents with young children. Resource constraints, however, have produced a broad array of variations in this model; most programs in the United States are now directed toward at-risk families who have been reported to social services or health agencies because of prenatal health risks or risks for child maltreatment. Comprehensive programs provide a variety of services, including in-home parent education and prenatal and early infant health care, screening, referral to and, in some cases, transportation to social and health services. Positive effects include improved childrearing practices, increased social supports, utilization of community services, higher birthweights, and longer gestation periods.

Researchers have identified improvements in cognitive and parenting skills and knowledge as evidence of reduced risk for child maltreatment; they have also documented lower rates of reported child maltreatment and number of visits to emergency services for home-visited families. The benefits of home visitation appear most promising for young, first-time mothers who delay additional pregnancies and thus reduce the social and financial stresses that burden households with large numbers of young children. Other benefits include improved child care for infants and toddlers and an increase in knowledge about the availability of community services for older children. The intervention has not been demonstrated to have benefits for children whose parents abuse drugs or alcohol or those who are not prepared to engage in help-seeking behaviors. The extent to which home visitation benefits families with older children, or families who are already involved in abusive or neglectful behaviors, remains uncertain.

Recommendation 5: As part of a comprehensive prevention strategy for child maltreatment, the committee recommends that home visitation programs should be particularly encouraged for first-time parents living in social settings with high rates of child maltreatment reports.

The positive impact of well-designed home visitation interventions has been demonstrated in several evaluation studies that focus on the role of mothers in child health, development, and discipline. The committee recommends their use in a strategy designed to prevent child maltreatment. Home visitation programs do require additional evaluation research, however, to determine the factors that may influence their effectiveness. Such factors include (1) the conditions under which home visitation should be provided as part of a continuum of family support programs, (2) the types of parenting behaviors that are most and least amenable to change as a result of home visitation, (3) the duration and intensity of services (including amounts and types of training for home visitors) that are necessary to achieve positive outcomes for high-risk families, (4) the experience

of fathers in general and of families in diverse ethnic communities in particular with home visitation interventions, and (5) the need for follow-up services once the period of home visitation has ended.

Intensive Family Preservation Services

Intensive family preservation services represent crisis-oriented, short-term, intensive case management and family support programs that have been introduced in various communities to improve family functioning and to prevent the removal of children from the home. The overall goal of the intervention is to provide flexible forms of family support to assist with the resolution of circumstances that stimulated the child placement proposal, thus keeping the family intact and reducing foster care placements.

Eight of ten evaluation studies of selected intensive family preservation service programs (including five randomized trials and five quasi-experimental studies) suggest that, although these services may delay child placement for families in the short term, they do not show an ability to resolve the underlying family dysfunction that precipitated the crisis or to improve child well-being or family functioning in most families. However, the evaluations have shortcomings, such as poorly defined assessment of child placement risk, inadequate descriptions of the interventions provided, and nonblinded determination of the assignment of clients to treatment and control groups.

Intensive family preservation services may provide important benefits to the child, family, and community in the form of emergency assistance, improved family functioning, better housing and environmental conditions, and increased collaboration among discrete service systems. Intensive family preservation services may also result in child endangerment, however, when a child remains in a family environment that threatens the health or physical safety of the child or other family members.

Recommendation 6: Intensive family preservation services represent an important part of the continuum of family support services, but they should not be required in every situation in which a child is recommended for out-of-home placement.

Measures of health, safety, and well-being should be included in evaluations of intensive family preservation services to determine their impact on children's outcomes as well as placement rates and levels of family functioning, including evidence of recurrence of abuse of the child or other family members. There is a need for enhanced screening instruments that can identify the families who are most likely to benefit from intensive short-term services focused on the resolution of crises that affect family stability and functioning.

The value of appropriate post-reunification (or placement) services to the child and family to enhance coping and the ability to make a successful transition

toward long-term adjustment also remains uncertain. The impact of post-reunification or post-placement services needs to be considered in terms of their relative effects on child and family functioning compared with the use of intensive family preservation services prior to child removal. In some situations, one or the other type of services might be recommended; in other cases, they might be used in some combination to achieve positive outcomes.

Recommendations For The Next Generation Of Evaluations

Determining which interventions should be selected for rigorous and in-depth evaluations in the future will acquire increased importance as the array of family violence interventions expands in social services, law, and health care settings. For this reason, clear criteria and guiding principles are necessary to guide sponsoring agencies in their efforts to determine which types of interventions are suitable for evaluation research. Recognizing that all promising interventions cannot be evaluated, public and private agencies need to consider how to invest research resources in areas that show programmatic potential as well as an adequate research foundation. Future allocations of research investments may require agencies to reorganize or to develop new programmatic and research units that can inform the process of selecting interventions for future evaluation efforts, determine the scope of adequate funding levels, and identify areas in which program integration or diversity may contribute to a knowledge base that can inform policy, practice, and research. Such agencies may also consider how to sustain an ongoing dialogue among research sponsors, research scientists, and service providers to inform these selection efforts and to disseminate evaluation results once they are available.

In the interim, the committee offers several guiding principles to help inform the evaluation selection process.

- meet the preconditions for experimentation that are described in the other principles outlined below.

With these principles in mind, the committee has identified a set of interventions that are the focus of current policy attention and service innovation efforts but have not received significant attention from research. In the committee's judgment, each of these nine interventions has reached a level of maturation and preliminary description in the research literature to justify their selection as strong candidates for future evaluation studies.

Training for Service Providers and Law Enforcement Officials

Training in basic educational programs and continuing education on all aspects

of family violence has expanded for professionals in the health care, legal, and social service systems. Such efforts can be expected to enhance skills in identifying individual experiences with family violence, but improvements in training may improve other outcomes as well, including the patterns and timing of service interventions, the nature of interactions with victims of family violence, linkage of service referrals, the quality of investigation and documentation for reported cases, and, ultimately, improved health and safety outcomes for victims and communities.

Training programs alone may be insufficient to change professional behavior and service interventions unless they are accompanied by financial and human resources that emphasize the role of psychosocial issues and support the delivery of appropriate treatment, prevention, and referral services in different institutional and community settings. Evaluations of their effectiveness therefore need to consider the institutional culture and resource base that influence the implementation of the training program and the abilities of service providers to apply their knowledge and skills in meeting the needs of their clients.

Evaluation research is needed to assess the impact of training programs on counseling and referral practices and service delivery in health care, social service, and law enforcement settings. This research should include examination of the effects of training on the health and mental health status of those who receive services, including short- and long-term outcomes such as empowerment, freedom from violence, recovery from trauma, and rebuilding of life. Evaluations should also examine the role of training programs as catalysts for innovative and collaborative services. They should consider the extent to which training programs influence the behavior of agency personnel, including the interaction of service providers with professionals from other institutional settings, their participation in comprehensive community service programs, and the exposure of personal experiences in institutions charged with providing interventions for abuse.

Universal Screening in Health Care Settings

The significant role of health care and social service professionals in screening for victimization by all forms of family violence deserves critical analysis and rigorous evaluation. Early detection of child maltreatment, spousal violence, and elder abuse is believed to lead to an infusion of treatment and preventive services that can reduce exposure to harm, mitigate the negative consequences of abuse and neglect, improve health outcomes, and reduce the need for future health services. Screening programs can also enhance primary prevention efforts by providing information, education, and awareness of resources in the community. The benefits associated with early detection need to be balanced against risks presented by false positives and false negatives associated with large-scale screening efforts and programs characterized by inadequate staff training and responses.

Such efforts also need to consider whether appropriate treatment, protection, and support services are available for victims or offenders once they have been detected.

The use of enhanced screening instruments also requires attention to the need for services that can respond effectively to the large caseloads generated by expanded detection activities. The child protective services literature suggests that increased reporting can diminish the capacity of agencies to respond effectively if additional resources are not available to support enhanced services as well as screening.

The use of screening instruments in health care and social service settings for batterer identification and treatment is more problematic, given the lack of knowledge about factors that enhance or discourage their violent behavior. Screening only victims may be insufficient to provide a full picture of family violence; however, screening batterers may increase the danger for their victims, especially if batterer treatment interventions are not available or are not reliable in providing effective treatment and if support services are not available for victims once a perpetrator is identified. Screening adults for histories of childhood abuse, which may help prevent future victimization of the patient or others, may also be problematic without adequate training or mental health services to deal with the possible resurgence of trauma.

Evaluation studies of family violence screening efforts could build on the lessons derived from screening research in other health care areas (such as HIV detection, lead exposure, sickle cell, and others). This research could provide data that would support or contradict the theory that early identification is a useful secondary prevention intervention, especially in areas in which appropriate services may not be available or reliable. The cost issues associated with universal screening need to be considered in terms of their implications for savings in possible cost reductions from consequent conditions (such as the health consequences of HIV infection, sexually transmitted diseases, unplanned pregnancy, substance abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and the exacerbation of other medical conditions) that may occur in other health care areas. Finally, the risks associated with screening (such as the establishment of a preexisting condition that may influence insurance eligibility) require consideration; such issues are already being addressed by some advocacy groups, insurance corporations, and regulatory bodies in the health care area.

Mental Health and Counseling Services

Little is known at present regarding the comparative effectiveness of different forms of therapeutic services for victims of family violence. Findings from recent studies of child physical and sexual abuse suggest that certain approaches (specifically cognitive-behavioral programs) are associated with more positive outcomes for parents, such as reducing aggressive/coercive behavior, compared

with family therapy and routine community mental health services. No treatment outcome studies have been conducted in the area of child neglect. Interventions in this field generally draw on approaches for dealing with other childhood and adolescent problems with similar symptom profiles.

For domestic violence, research evaluations are in the early stages of design and empirical data are not yet available to guide analyses of the effectiveness of different approaches. Major challenges include the absence of agreement regarding key psychosocial outcomes of interest in assessing the effectiveness of interventions, variations in the use of treatment protocols designed for post-traumatic stress for individuals who may still be experiencing traumatic situations, tensions between protocol-driven models of treatment (which are easier to evaluate) and those that are driven by the needs of the client or the context in which the violence occurred, the co-occurrence of trauma and other problems (such as prior victimization, depression, substance abuse, and anxiety disorders) that may have preceded the violence but require mental health services, and the difficulty of involving victims in follow-up studies after the completion of treatment. Variations in the context in which mental health services are provided for victims of domestic violence (such as isolated services, managed care programs, and services that are incorporated into an array of social support programs, including housing and job counseling) also require attention. Topics of special interest include contextual issues, such as the general lack of access to quality mental health services for women without sufficient independent income, and the danger of psychiatric diagnoses being used against battered women in child custody cases.

Collaborative efforts are needed to provide opportunities for the exchange of methodology, research measures, and designs to foster the development of controlled studies that can compare the results of innovative treatment approaches with routine counseling programs in community services.

Comprehensive Community Initiatives

Evaluations of batterer treatment programs, protective orders, and arrest policies suggest that the role of these individual interventions may be enhanced if they are part of a broad-based strategy to address family violence. The development of comprehensive, community-based interventions has become extremely widespread in the 1990s; examples include domestic violence coordinating councils, child advocacy centers, and elder abuse task forces. A few communities (most notably Duluth, Minnesota, and Quincy, Massachusetts) have developed systemwide strategies to coordinate their law enforcement and other service responses to domestic violence.

Comprehensive community-based interventions must confront difficult challenges, both in the design and implementation of such services, and in the selection of appropriate measures to assess their effectiveness. Many evaluations of comprehensive community-based interventions have focused primarily on the

design and implementation process, to determine whether an individual program had incorporated sufficient range and diversity among formal and informal networks so that it can achieve a significant impact in the community. This type of process evaluation does not necessarily require new methods of assessment or analysis, although it can benefit from recent developments in the evaluation literature, such as the empowerment evaluations discussed in Chapter 3 .

In contrast, the evaluation challenges that emerge from large-scale community-based efforts are formidable. First, it may be difficult to determine when an intervention has reached an appropriate stage of implementation to warrant a rigorous assessment of its effects. Second, the implementation of a community-wide intervention may be accompanied by a widespread social movement against family violence, so that it becomes difficult to distinguish the effects of the intervention itself from the impact of changing cultural and social norms that influence behavior. In some cases, the effects attributed to the intervention may appear weak, because they are overwhelmed by the impact of the social movement itself. Third, the selection of an appropriate comparison or control group for community-wide interventions presents formidable problems in terms of matching social and structural characteristics and compensating for community-to-community variation in record keeping.

These challenges require close attention to the emerging knowledge associated with the evaluation of comprehensive community-wide interventions in areas unrelated to family violence, so that important design, theory, and measurement insights can be applied to the special needs of programs focused on child maltreatment, domestic violence, and elder abuse. Although no single model of service integration, comprehensive services, or community change can be endorsed at this time, a range of interesting community service designs has emerged that have achieved widespread popularity and support at the local level. Because their primary focus is often on prevention, rather than treatment, comprehensive community interventions have the potential to achieve change across multiple levels of interactions affecting individuals, families, communities, and social norms and thus reduce the scope and severity of family violence as well as contribute to remedies to other important social problems.

A growing research literature has appeared in other fields, particularly in the area of substance abuse and community development, that identifies the conceptual frameworks, data collection, and methodological issues that need to be considered in designing evaluation studies for community-based and systemwide interventions. As an example, the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention in the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has funded a series of studies designed to improve methodologies for the evaluation of community-based substance abuse prevention programs that offer important building blocks for the field of family violence interventions.

Developing effective evaluation strategies for comprehensive and systemwide programs is one of the most challenging issues for the research community

in this field. No evaluations have been conducted to date to examine the relative advantages of comprehensive and systemwide community initiatives compared with traditional services. Evaluations need to consider the mix of components in comprehensive interventions that determine their effectiveness and successful implementation; the comparative strengths and limitations of inter- and intra-agency interventions; community factors, such as political leadership, historical tensions, diversity of ethnic/cultural composition, and resource allocation strategies; and the impact of comprehensive interventions on the capacity of service agencies to provide traditional care and effective responses to reports of family violence.

Shelter Programs and Other Domestic Violence Services

Over time, most battered women's shelters have expanded their services to encompass far more than the provision of refuge. Today, many shelters have support groups for women residents, support groups for child residents, emergency and transitional housing, and legal and welfare advocacy. Nonresidential services also have expanded, so that any battered woman in the community is able to attend a support group or request advocacy services. Many agencies now offer educational groups for men who batter, as well as programs dealing with dating violence. Some communities have never opened a shelter yet are able to offer support groups, advocacy, crisis intervention, and safe homes (neighbors sheltering a neighbor, for example) to help battered women and their families in times of crisis. In addition to providing services for victims, the battered women service organizations also define their goal as transforming the conditions and norms that support violence against women. Thus these organizations work as agents of social change in their communities to improve the community-wide response to battered women and their children.

Shelter services and battered women's support organizations are ready for evaluations that can identify program outcomes and compare the effectiveness of different service interventions. Research studies are also needed that can describe the multiple goals and theories that shape the program objectives of these interventions, provide detailed histories of the ways in which different service systems have been implemented, and examine the characteristics of the women who do or do not use or benefit from them.

Protective Orders

Protective orders can be an important part of the prevention strategy for domestic violence and help document the record of assaults and threatening actions. The low priority traditionally assigned to the handling of protective orders, which are usually treated as civil matters in police agencies, requires attention, as do the procedural requirements of the legal system. Courts have

accepted alternative forms of due process, including public notice, notice by mail, and other forms of notification that do not require personal contact. Efforts are needed now to compare the effectiveness of short-term (30-day) restraining orders with a longer (1-year) protective order in reducing violent behavior by offenders and securing access to legal and support services for the complainants.

In-depth case studies and interviews with victims who have had police and court contacts because of domestic violence are needed to highlight individual, social, and institutional factors that facilitate or inhibit victim use of and perpetrator compliance with protective orders in different community settings. Such studies could (1) reveal patterns of help-seeking contacts and services that affect the use of protective orders and compliance with their requirements, (2) highlight the forms of sanctions that are appropriate to ensure compliance and to deter future violent behavior, (3) explore the extent to which the effects of protective orders are enhanced in reducing violence if victim advocates, shelter services, or other social support resources are available and are used by the victim in redefining the terms of her relationship with her partner, and (4) examine the extent to which protective orders can mitigate the consequences of violence for children who may have been assaulted or who may have witnessed an assault against their mother.

Child Fatality Review Panels

The emergence of child fatality review teams in 21 states since 1978 represents an innovative effort in many communities to address systemwide implications of severe violence against children and infants. Child fatality review teams involve a multiagency effort to compile and integrate information about child deaths and to review and evaluate the record of caseworkers and agencies in providing services to these children when a report of abuse or neglect had been made prior to a child's death. These review teams can provide an opportunity to examine the quality of a community's total approach to child abuse and neglect prevention and treatment.

The experience of child fatality review teams in identifying systemic features that enhance or weaken agency efforts to protect children needs to be evaluated and made accessible to individual service providers in health, legal, and social service agencies. Key research issues include: the effect of review team actions on the protection of family members of children who have died as a result of child maltreatment; the impact of child fatality review reports on the prosecution of offenders; the influence of review team efforts on the routine investigation, treatment, and prevention activities of participating agencies; the impact of review teams on other community child protection and domestic violence prevention efforts; and the identification of early warning signals that emerge in child homicide investigations that represent opportunities for preventive interventions.

Child Witness to Violence Programs

Child witness programs represent an important development in the evolution of comprehensive approaches to family violence, but they have not yet been evaluated. Evaluation studies of these programs should examine the experience with symptomatology among children who witness family violence, to determine whether and for whom early intervention influences the course of development of social and mental health consequences, such as depression, anxiety, emotional detachment, aggression and violence, and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Such studies could also compare variations in the developmental histories of children who witness violence with those of children who are injured or otherwise are directly victimized by their parents or who witness violence in their communities. Evaluation studies should consider the recommended forms of treatment for these children, the standards of eligibility that determine their placement in treatment programs, and the impact of institutional setting (hospital, shelter, or social service agency) and reimbursement plans on the quality of the treatment.

Elder Abuse Services

Only seven program evaluation studies have been published on elder abuse interventions, none of which includes random groups and most of which involve small sample sizes. Three major issues challenge effective interventions in this area: the degree of dependence between perpetrators and victims, restricted social services budgets, general public distrust of social welfare programs, and the relationship between judgments about competence and the application of the principles of self-determination and privacy to the problem of elder abuse.

Evaluation studies should consider the different types and multiple dimensions of elder abuse in the development of effective interventions. The benefits of specific programs need to be compared with integrated service systems that are designed to foster the well-being of the elderly population without regard to special circumstances. Evaluation research should be integrated into community service programs and agency efforts on behalf of elderly persons to foster studies that involve the use of comparison and control groups, common measures, and the assessment of outcomes associated with different forms of service interventions.

Topics For Basic Research

The committee identified four basic research topics that require further development to inform policy and practice. These topics raise fundamental questions about the approaches that should be used in designing treatment, prevention, and enforcement strategies. As such, they highlight important dimensions of family violence that should be addressed in a research agenda for the field.

birth, infancy, and adolescence. Other issues linked to family formation include the use of corporal punishment in child discipline, gender roles, privacy, and strategies for resolving conflict among adults or siblings.