- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Here Are the Poetry Books to Read in 2024

14 titles to add to your tbr pile.

As a reader, I love this moment when we look ahead to the new year’s literary landscape, considering and prioritizing what to read first, wondering what will enthrall us. Sure, an anticipated list can have the delicious capriciousness of an amuse-bouche; in the end, it doesn’t tell you much about the full menu. But isn’t that the joy of it? There’s still so much left to discover.

David Woo and I have gathered a little more than a baker’s dozen of titles for you from a year that will also offer Marie Howe’s New and Selected (Norton); new collections from Andrea Cohen ( The Sorrow Apartments, Four Way Books) and Geffrey Davis ( One Wild World Away, BOA); and a slate of debuts that includes Diego Baez’s Yaguareté White (University of Arizona Press) ; Sarah Ghazal Ali’s Theophanies (Alice James Books); and Yalie Saweda Kamara’s Besaydoo (Milkweed). Forgive us, readers, we aren’t very good at anticipation: when we had the books in hand, we dove in. Welcome to our poetry preview for 2024, and please come back every month for more.

–Rebecca Morgan Frank

“Close, closer,” Diane Seuss writes in her new book Modern Poetry , “to that sheeted edge.” As I turn the pages of poetry books in 2024, I hope to see glimpses of that edge, the edge of something in extremis, perhaps, but also the edge of the piece of paper, which is also the edge of a poet’s mind. Strange transfigurations of form, startling intensifications of moral and political perception, unexpected evocations of consciousness—I anticipate a full range of astonishments in the new year.

Some of the books will be extensions of oeuvres I’ve pleasurably followed for years by poets seeking to achieve the next culmination in the life of their artistry, like Victoria Chang’s With My Back to the World (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), Don Mee Choi’s Mirror Nation (Wave Books), Kwame Dawes’s Sturge Town (Norton), Tracy Fuad’s Portal (University of Chicago), Joyelle McSweeney’s Death Styles (Nightboat Books), Carl Phillips’s Scattered Snows, to the North (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), Donald Revell’s Canandaigua (Alice James Books), and Corey Van Landingham’s Reader, I (Sarabande). Other books will be by poets who are new to me and, I hope, new to themselves, finding their edge for the reader’s astonishment.

–David Woo

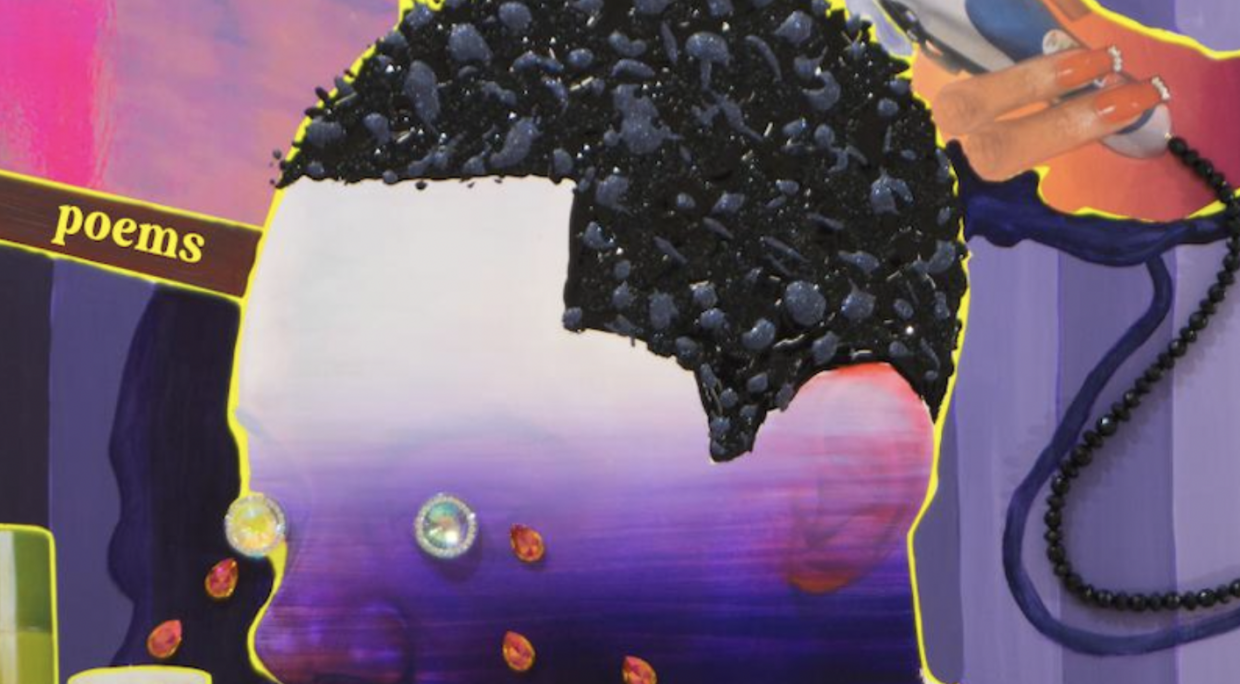

Diana Khoi Nguyen, Root Fractures (Scribner, January 30)

Diana Khoi Nguyen ’ s Root Fractures builds from her lauded debut, Ghost Of , a Kate Tufts Discovery Award winner and a finalist for the National Book Award with further investigations of family histories of grief and displacement. In this new collection, absence and omission evolve into a formidable sense of presence and narrative.

A series of poems called “Root Fractures” carries on the multimedia hybridity of photograph and textual cutouts, layers, and fades of her earlier collection, while her series Đổi Mới (which in English translates to renew or renovate, and also refers to economic reforms in Vietnam in the 1980’s) turns to the sentence as its tool, through prose poems, and, occasionally a more fragmented weaving essayistic form. The threads between the books makes me wonder if this will evolve into a trilogy of sorts; I am already anticipating what comes next from her. –RMF

Anne Carson, Wrong Norma (New Directions, February 6)

“The dark side of self-creation,” wrote Louise Glück, “is its underlying and abiding sense of fraud.” Even with a writer of justly vast reputation as the great Canadian poet Anne Carson, each time I open a new book of hers I find myself entertaining the notion that her strangeness and originality may, in fact, be that of a trickster who magics her audience into a state of hallucinatory submission. But surely this is the uncanny way in which true originality operates. Each time I resist Carson’s work, I end up joyously succumbing to her undeniable strengths: the profligate array of innovative forms, the mesmerizing creation and decreation of selves, the classical erudition, the sublimely weird inner life.

Wrong Norma continues the Carsonesque tradition, from its amusing title calling to mind not only Norma Desmond but Carson’s recent performance piece Norma Jeane Baker of Troy (a conflation of Marilyn Monroe and Euripides), its promiscuous arrangements of prose poems, apparently autobiographical vignettes, and short fictions (“long afternoons at the kill house”), off-kilter verse translations (a portion of Plato’s Symposium entitled “OH WHAT A NIGHT”), empathetic insights into the enigmas of others including John Ashbery (“a personality disposed to careless joy in any situation”), interludes of handwritten marginalia around stressed swatches of gnomic typewritten phrases, and even a poignant, illustrated depiction of Paul Celan’s encounter with Martin Heidegger.

As with Carson’s previous books, Wrong Norma is magisterially contrarious in conception, an omnium-gatherum text ensconced in a sui generis sensibility, a “commonplace struggle to know beauty” that doesn’t preclude uncommonly beguiling pronouncements: “Is it proper to use the informal 2nd-person singular pronoun tu or toi when addressing the sky.” “To survive you need an edge.” “Can you treat everything as an emergency without losing the reality of time, which continues to drip, laughtear by laughtear?” –DW

Penelope Pelizzon, A Gaze Hound That Hunteth By the Eye (University of Pittsburgh Press, February 13)

Penelope Pelizzon’s third collection promises a wit and formal ease. Her playful allusions range from D.H. Lawrence– “trio of nephews,/ avid hagiographers/ who praise the body’s stinks and stews” in “Orts and Slarts,” to Henry Howard – “The Soote Season” in which “yoga-goers hoist mats/ rolled cigar-wise in eco-cotton wrappers,” to Sappho–“Some Say,” in which “gray hairs are the smoke off ships / whose burning all night bloodied the eastern sky.”

The world is gross and beautiful from a dog’s eye view, in the destructive landscape of gypsy moths, and within the world of aging and changing desires; the speaker of “Wishes for Fifty” invokes, “Let there be / lascivity with sexy / librocubicularists.” (Librocubicularists are those who read in bed, if you didn’t already know this essential word for readers of Lit Hub.) Pelizzon, who balances a life between college professor at UConn and traveler to temporary homes in Syria, Namibia, South Africa, and Italy with a foreign diplomat spouse, offers a keen eye and ear to whatever she turns her attention to in this romp and bite of a collection. –RMF

Diane Seuss, Modern Poetry (Graywolf Press, March 5)

If the capacious version of the sonnet that Seuss used in her previous collection, the award-winning frank , proved a gorgeous way to rein in—structure, organize, make into art—the enthrallingly candid rovings of her mind, her new book takes the canon itself as inspiration, or perhaps a copy of an old poetry anthology left in a puddle, adapting its forms to her special subject matter, the poet who somehow sprang from the mud of a non-literary or even anti-literary background.

“What I know of literature, of history, is spotty,” Seuss claims, dubiously, as if readers were expecting her to be Gibbon or Harold Bloom. The self-deprecation (“For my people / it is the flaw that counts”) is of a piece with the deconstructive impulse at the heart of this book, the desire to privilege the “itches and psychological riches” of the working class over the aristocratic milieu, “dust-covered / and ornate,” from which the poetic tradition arose, carving up and reshaping the venerable forms in the image of her life: her quatrains are intentionally baggy, her villanelle refuses to be a villanelle, although her loose blank verse is stately and self-revealing, like a 21st-century Wordsworth.

All of these riffs on aspects of poetry (“that snarling, flaming bitch”) are frame and afflatus, as forms should be, for the true art of Seuss’s poetry, which lies in the ingeniously offhand style with which she presents her riveting, full-frontal insights about people, like Jim the queer drama teacher who thought they should marry but was really in love with “The Boy in The Fantasticks ,” the lovers who lied to her or to whom she lied (“I’ve said big dick when I meant small dick”), or the raw and barely viable self itself, always trying and never attaining the nebulous goal of being a better self: “Inside, Diane, you suffer / and your suffering is you.” –DW

Cindy Juyoung Ok, Ward Toward (Yale University Press, March 5)

Perhaps the most distinguished prize for a first poetry book is the Yale Series of Younger Poets, which is legendary for the tenure of W. H. Auden, who selected John Ashbery, Adrienne Rich, W. S. Merwin, and James Wright. While there is a plethora of prizes now—like the Academy of American Poets prize, whose 2024 release will be Sara Daniele Rivera’s The Blue Mimes (Graywolf Press), or one that was new to me, the Trio Award for emerging poets, whose forthcoming title is Christian Gullette’s Coachella Elegy (Trio House Press)—Rae Armantrout’s choice of Cindy Juyoung Ok’s Ward Toward for the Yale prize will represent all the exciting debuts I’m looking forward to this year.

With brio and sorrow, Ok’s book investigates such subjects as hospitalization for a major depressive disorder, the anti-Asian Atlanta spa shootings, and the failures of romantic and familial love. She is equally at home in parables, dream states, and more abstract contemplation: “Hypercorrection reveals an anxiety around the appearance of knowing and belonging.”

Using a variety of formal devices, including poems written in Korean-inflected English and one in the shape of Korea, she moves through a range of emotional tenors to touch the heart of her life as a “younger poet.” Ok’s métier in this lovely debut is an elegantly discursive, analytical style studded with ironies: “When bitten, ignore the instinct to pull, instead / pushing the latched body part further into // the biting mouth. This will lead to release, / though perhaps then it all starts again.” –DW

Rowan Ricardo Phillips, Silver (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, March 5)

“Poetry is séance and silence and science,” Phillips writes in Silver , his fourth collection. The seance summons a presiding spirit of this collection, the Wallace Stevens of the late-Romantic meditative eloquence (the lights at Key West that “mastered the night and portioned out the sea”). The silence is that of a place in the woods away from the pandemic where the speaker goes to cull “from those cold mountaintops the next fire.” The silence is that of a grandmother dying on the cusp of the pandemic. The science is the prosody of air and metal that lifts a silver plane with its silver contrail above the woods and the silver of the rental car to which the speaker rushes to avoid an expired parking meter, also silver, as the grandmother expires. “And I will be nothing but poetry,” the speaker says in his mournful solitude, “A blank in the blankness of the long game.”

The poems are more forthright than Stevens, more directly autobiographical and socially equitable, but the dedication with which Phillips approaches the art of poetry is, like Stevens, tonic and inspiring. “To be bottomless, atemporal, absent of hierarchy, and just,” he enjoins in “Biographia Literaria. “To accept that poetry is older than reflex, that it predates intention, that it is the breath your breath takes before you breathe.” – DW

Jean Valentine, Light Me Down: The New and Collected Poems (Alice James, April 9)

Ever since Jean Valentine died in 2020, there’s been a hole left in the American poetic landscape, or perhaps I should say dreamscape. Her previous New and Collected, which won the National Book Award in 2004, gave way to the spare and stirring grief, memory, and visions of her later work that includes three of my favorites: Little Boat, Break the Glass, and Shirt in Heaven. What an enormous gift to have one of our major poets collected anew, and to have these new poems to discover. Let the countdown to this April release begin. –RMF

Reginald Shepherd, The Selected Shepherd (University of Pittsburgh Press, April 9)

In his last book, before his premature death from cancer, Shepherd (1963-2008) wrote, “The dead move fast, nowhere / to nowhere in no time at all.” To read him and others with posthumous collections forthcoming this year, like The Collected Poems of Delmore Schwartz and Invisible Mending: The Best of C. K. Williams (both Farrar, Straus and Giroux), is to slow the departure of the dead and situate them in the somewhere of one’s passionate attention to their pages.

By the time of his death, Shepherd was attaining the status of a poet’s poet, with his command of literature, his aesthete’s attention to style, his restless metamorphosis from book to book (six in all), and his lacerating honesty. He was outspoken about a Bronx tenement upbringing with a difficult single mother who was dissipated, alcoholic, and suicidal (“You were my mother; I love you more / dead”) and about his identity as an HIV-positive, Black, gay man whose preference was handsome white men (he labeled himself a “snow queen”), but he complicated these themes through the ruthless clarity of his self-knowledge. For example, in “Hygiene,” a poem about Jeffrey Dahmer, who murdered many men of color, Shepherd wrote, “Every white man on the bus looks / like him, what I’d want to be destroyed / by, want to be.”

Jericho Brown’s selections return to the literary scene a poet who now looks like a gainfully conflicted forerunner of the confessional poetic practice of many queer and BIPOC poets today as well as a source of enduring aesthetic contemplation, like the tremblingly elliptical love poem “A Little Knowledge,” “The poems I wanted were nothing / like my heart: nothing joined / us together, nothing held us apart.” – DW

Arthur Sze, The Silk Dragon II: Translations of Chinese Poetry (Copper Canyon Press, April 16)

The artistic interpretations that we call “translations” are central to my love of poetry, helping me to imagine with greater immediacy other cultures and epochs, however circumscribed a work may be by the English language. Among the translations I’m looking forward to this year include Stephen Mitchell’s version of Catullus: Selected Poems (Yale University Press), Brian Henry’s of Tomaž Šalamun’s Kiss the Eyes of Peace (Milkweed Editions), Robin Myers’ of Javier Peñalosa M.’s What Comes Back (Copper Canyon), Jeff Clark’s of Stéphane Mallarmé’s A Roll of the Dice (Wave Books), Edward Snow’s of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Book of Hours (Norton), and Peter Filkins’ of Ingeborg Bachman’s Darkness Spoken (Zephyr Press).

As is evident in his award-winning collected poems, The Glass Constellation (Copper Canyon), Arthur Sze’s poetic practice has always made the thematic ranges and sensory detailing of classical Chinese poetry central to his own imagination, like the woodblock carver in the poem “Water Calligraphy” who “peels off pear shavings, stroke by stroke, / and foregrounds characters against empty space.” The Silk Dragon II is an augmented edition of The Silk Dragon (2001), adding 18 new translations, mostly of poets since the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), to a working poet’s selection of more than a millennium of Chinese poems that have engaged and inspired him.

In these lucid translations, Sze offers pleasures for all types of readers, those who want another taste of ancient favorites like Du Fu (“The nation is broken, but hills and rivers remain”) and Li He (“I will cut off the dragon’s feet / and chew the dragon’s flesh”), those new to Chinese poetry (his candid account of one poem’s tortuous process remains the best introduction to the art of Chinese translation that I know of), and those who admire Sze’s own work for its telling specificities, as in Wen Yiduo (“I feed the fire cobwebs, rat droppings, and also the scaly skins of spotted snakes”), and its prismatic finesse, as in Xi Chuan (“The figures acquire the mountains / and waters, just as the mountains acquire the emerald and lapis”). –DW

Stephanie Choi, The Lengest Neoi (University of Iowa Press, May 6)

Selected by Brenda Shaughnessy for the Iowa Poetry Prize, Stephanie Choi’s debut, The Lengest Neoi, revels in formal variation and conversation (with poets, films, language/s, a mother), albeit with twists. A lipogram isn’t a lipogram, but the story of a tattoo with a missing letter; a sonnet crown gets disrupted, or expanded, by missing words and a crossword and with missing words; a series of “sound translations” draw on Jonathan Stalling’s Yíngēlìshi process– there’s much to solve, puzzle over, discover. The collection’s title reflects Choi’s language play: Leng Neoi, which translates from the Cantonese to “Pretty Girl,” becomes “Lengest,” a linguistically hybrid superlative for prettiest. These poems upend “corrections” of language and body–the spine, the jaw. A poem with headgear ends with a mother’s twist of the expander: “she didn’t know /. She was turning/ the song/ right out of me.” –RMF

Li-Young Lee, The Invention of the Darling (Norton, May 14)

The good news for Li-young Lee fans who waited a decade for his last collection, The Undressing (2018), is that 2024 brings another new collection, The Invention of the Darling. The speaker in the title poem of Li-Young Lee’s new collection asks a friend, “Do all lovers begin in hell and end in knowledge?” The catch is revealed in this repeated line: “My friend and I are in love with the same woman.” But this poem feels more tied to the contemporary human world than the rest: expect more elemental and mythopoetical longer poems, characteristically spare in their embrace of the vast (love, death, God), and circular in their choruses of repetition and return through phrases and figures–serpent, hummingbird, and, in the familiar Lee cosmos, mother and father. –RMF

José Antonio Rodríguez, The Day’s Hard Edge (Northwestern University Press, June 15)

“Tender,” “Shelter,” “Entire,” “In the Presence of Sunlight,”– these José Antonio Rodríguez poems from The Day’s Hard Edge perfect the dance between lyric and storytelling, between autobiography and ars poetica, and you may have caught all of them in The New Yorker already. Rodriquez, a queer Chicano poet with a few poetry collections and a memoir under his belt, returns to Northwestern University press with this collection that promises to reflect him at new heights in his work. In “Pilgrim,” he wonders “About plants standing in for our bodies / In poems” –then he turns to roses and Virgen of Guadalupe: “ Yes, she was a deity then,/ But she had inhabited a body once.” These are the rare poems about making that make me want to read more. “I’m not saying I’m better than you,” the speaker of “Mercy” says. “I’ve been a prophet. I’ve been a fool.” I can’t wait to have the full collection in hand: I’m anticipating this as a 2024 favorite. –RMF

Dawn Lundy Martin, Instructions for the Lovers (Nightboat, June 18)

“Elsewhere, corporeal men made to eat at each other’s / necks. Hundreds upon hundreds—a caterpillar, iron in the face.” Dawn Lundy Martin’s newest collection’s offers movement from an embodied lyric fullness to a minimalism or fragmentation; the notes reveal that many of these poems emerge out of collaboration, including text messages and, with poems like “From Which the Thing is Made,” a poetic exchange with Toi Derricote for their collaborative chapbook A Bruise is a Figure of Remembrance (Slapering Hol Press, 2020).

I look forward to spending time with this one: the poems in Instructions for Lovers look to be intimate and bodily, yet textural and textual in the approach to language: “We surrender in the teeming utterance/ of materials soaked with sentences already made in air / and by machines.” And yet, as “No Language Suffices the Body,” concludes, “How long can we live without a body? / Once, the body, once its spiked desire.” –RMF

Danez Smith, Bluff (Graywolf Press, August 24)

Certain moments in Smith’s previous book Homie inhabit me to this day, like the fiercely moving lines that compared a mother’s love to the speaker’s HIV (“i know what it is / to nurse a thing you want to kill // & can’t”) or the glance that the Pakistani girl at the bus stop gave to the Black speaker after a white man asked where she was from, one of those “innocent” questions that led Smith to a meditation on the many colors of oppression (“what advice do the drowned have for the burned? / what gossip is there between the hanged & the buried?”).

Smith’s fourth full-length collection arrives in August and looks to be a restless, passionate admixture of forms, a chopped-up sonnet, prose vignettes and political commentaries, a long poem about the Rondo neighborhood in Smith’s native St. Paul. From the previews of pieces I’ve seen, I expect to hear a forceful and outraged voice as the poet maps the coordinates of queer, Black life in the Twin Cities during the pandemic and the protests after the murder of George Floyd: “When was COVID-19? What infection did I fear last week? The cops are the sickness.” I also sense from some new poems, like “less hope,” a questioning urgency that nudges the outrage into a spiritual or metaphysical realm: “Satan, like you did for God, i sang. / i sang for my enemy, who was my God. / i gave it my best. i bowed and smiled. / teach me to never bend again.” –DW

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Rebecca Morgan Frank and David Woo

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

In Praise of Reading: How Literature Enables Us to Inhabit New Worlds

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Five of the Best Books about Studying Poetry

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

If you’re studying poetry at school or university, or are simply a fan of the world of verse, it’s useful to have some handy guides standing by to assist with the terminology and to shed light on the various poetic forms used by poets, and the sometimes challenging language of poetry.

In our experience, the following five books are among the greatest books for the student of poetry (though there are, needless to say, many more helpful books on the market) and all five books will help the poetry fan to understand and appreciate poetry to a greater degree.

Disclaimer: as an Amazon Associate, we get commissions for purchases made through links in this post.

Subtitled A Guide to Reading Poetry for Pleasure and Practical Criticism , this book – which was updated for a second edition in 2005 – is a wonderfully clear and comprehensive introduction to the appreciation of poetry. John Lennard shows how we can enjoy poetry by understanding its technical features and techniques: his epigraph, from C. L. R. James, suggests a parallel between appreciating cricket and appreciating poetry.

If we know nothing of the technical aspects of the game of cricket, we can still enjoy it, but if we understand how the game works and what techniques the players use, we can ground our enjoyment in something more specific and informed than ‘mere impressionism’. Invaluable for any student of poetry at university (and very helpful for those at school), but also useful for anyone who wishes to understand the rules of metre, rhyme, syntax, and form in more depth.

This is a highly readable introduction to the practice of literary criticism: how to analyse a poem . Padel considers 52 different poems and offers a close reading of them, beautifully bringing out the subtle meanings of the poetry and the ways in which the poet generates such meanings.

Christopher Ricks, The Force of Poetry .

This 1984 volume is a collection of essays written during the 1960s-1980s, by one of the greatest living critics of poetry. Upon reading Ricks’s biography of Tennyson, W. H. Auden called Ricks ‘exactly the kind of critic every poet dreams of finding’.

But Ricks is also a brilliant writer too, with a fondness (some would say weakness) for puns and wordplay of all kinds. He clearly has great fun pondering the significance of a semi-colon or set of parentheses, or the meaning of a particular image or word. This volume includes essays on, among others, medieval poet John Gower , John Milton, Samuel Johnson , Geoffrey Hill, Stevie Smith, and – indeed, William Empson, author of our next book recommendation.

William Empson (1906-1984) was a poet as well as a critic, and this probably helped him to get under the skin, as it were, of many of the poems he analyses in this pioneering work of poetry criticism, published in 1930 and written when he was still only in his early twenties (and completed shortly after he had been expelled from the University of Cambridge when contraceptives were found in his rooms).

Taking his examples from Geoffrey Chaucer as well as T. S. Eliot, Empson wittily examines the various ways in which poets generate ambiguity in their work, from simple examples to more complex and less easily resolved instances. Jonathan Bate called Empson the funniest critic of the twentieth century . He is also one of the most illuminating.

This book is aimed at those who want to understand how poetry works but also want to write it as well, and Fry is an amiable and informative guide, taking us through the various forms and stylistic features poets use. Despite its focus on such things, the book is never dry and manages to inform and educate as well as entertain.

So much for our five recommendations, which we think should adorn the bookshelf of any poetry fan. But have you got an alternative recommendation for ‘best introduction to poetry’ or ‘greatest books for the student of poetry’? If so, let us know – we realise this list of five books is hardly comprehensive, but merely a whistle-stop introduction to what’s out there.

For more poetry help, see our advice for the close reading of poetry and our English literature essay tips . For the word-lover, we recommend this little-known dictionary of weird and wonderful words .

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

4 thoughts on “Five of the Best Books about Studying Poetry”

Add “How Does a Poem Mean?” by poet and critic (and lover of odd words) John Ciardi.

I’m a fan of John Hollander’s RHYME’S REASON, too. In it he details how to write in a bunch of different classic poetic forms — in those poetic forms. Very entertaining.

Reblogged this on Recommended book and blog news, poetry and tarot inspiration and commented: Glad Stephen Fry was included, this book is the definitive introduction to both common and obscure verse forms and should be on every aspiring poets shelf or those who just love the art

Reblogged this on nativemericangirl's Blog .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Join Discovery, the new community for book lovers

Trust book recommendations from real people, not robots 🤓

Blog – Posted on Friday, Oct 11

60+ best poetry books of all time.

Poetry is an art form that predates written text. It fuses meaning, sound, and rhythm to create magical worlds that offer insights into ourselves – and into the unknown. Since it’s taken to the page, poets have even been able to play with how it looks, using word placement to add yet another layer of meaning. The form almost defies definition, but we know we tend to look to it when we need a little inspiration, to light that spark that only the best poetry knows how to ignite 🔥

If you’re feeling the urge to jump into the world of poetry books, you’ve come to the right place. We’ve compiled a list of collections that should satisfy the breadth and width of most poetic imaginations, from the traditional to the avant-garde. It includes what some consider the best poetry books of all time , alongside lesser-known but equally breathtaking compilations.

Some of the poetry books below are individual collections, while others offer an overview of a certain poet’s work. And then there are anthologies that gather groups of similar poets for closer reflection. Spanning many countries, languages, and time periods, the list below will have you perfectly primed for the endless possibilities that poetry has to offer.

Psst — if you've ever wondered which 20-second poem you can recite while washing your hands, take our quiz below 😉

Which 20-second poem should you recite while washing your hands?

Discover the perfect poem for you. Takes 30 seconds!

Best Poetry Book Classics

1. the complete poems of emily dickinson by emily dickinson (1830–1886).

Excerpt: “'Hope' is the thing with feathers – / That perches in the soul – / And sings the tune without the words – / And never stops – at all –”

2. If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho by Sappho, Translated by Anne Carson (Died 580 BC)

Excerpt: “Come to me now: loose me from hard / care and all my heart longs / to accomplish, accomplish. You / be my ally.”

3. The Rumi Collection by Rumi (1207–1273), Translated by Kabir Helminski

Excerpt: “You know the true value of every article of / merchandise, / but if you don’t know the value of your own soul, / it’s all foolishness.”

4. On Love and Barley: Haiku of Basho by Basho (1644–1694), Translated by Lucien Stark

Basho was not only a 17th-century Japanese haiku master — he was also a Buddhist monk and traveler. He engaged with natural imagery to create his well-known haikus and even his pen name — writing under Basho after being gifted basho trees from a student. On Love and Barley: Haiku of Basho , translates and refines Basho’s work. It also contextualizes it with a foreword by the translator, Lucien Stark, discussing how Basho’s life and beliefs influenced his poetry.

Excerpt: “Spring’s exodus — / birds shriek, / fish eyes blink tears”

5. The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (1265-1321)

Excerpt: “How I came to it I cannot rightly say,/so drugged and loose with sleep I had become/when I first wandered there/from the True Way.”

6. The Complete Sonnets and Poems by William Shakespeare (1564–1616)

Excerpt: " So they lov'd, as love in twain / Had the essence but in one; / Two distincts, division none: / Number there in love was slain.”

7. Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman (1819–1892)

Excerpt: “O I say these are not the parts and poems of the body only, but of the soul, / O I say now these are the soul!”

8. John Donne’s Poetry by John Donne (1572–1631)

Excerpt: “Death, be not proud, though some have called thee / Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so; / For those whom thou think'st thou dost overthrow / Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.”

9. Complete Writings by Phyllis Wheatley (1753-1784)

Excerpt: “But here I sit, and mourn a grov’ling mind, / That fain would mount, and ride upon the wind. / But I less happy, cannot raise the song, / The fault’ring music dies upon my tongue.”

10. The Flowers of Evil by Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867)

Excerpt: “Nature is a temple, where the living / Columns sometimes breathe confusing speech; / Man walks within these groves of symbols, each / Of which regards him as a kindred thing.”

11. The Complete Poetry Of Edgar Allan Poe by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)

Excerpt: “Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, / Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore — / While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, / As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.”

Best 20th-Century Poetry

12. robert frost’s poems by robert frost (1874–1963).

Excerpt: “Something there is that doesn't love a wall, / That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it, / And spills the upper boulders in the sun; / And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.”

13. 100 Selected Poems by e e cummings (1894–1962)

Excerpt: “when the world is puddle-wonderful / the queer / old balloonman whistles / far and wee / and bettyandisable come dancing / from hop-scotch and jump-rope and / it’s / spring”

14. Selected Poems by Mary Oliver (1935–2019)

Excerpt: “The vulture’s / wings are / black death / color but / the underwings / as sunlight / flushes into / the feathers / are bright / are swamped/with light.”

15. The Complete Poetry by Maya Angelou (1928–2014)

Excerpt: “Out of the huts of history’s shame / I rise / Up from a past that’s rooted in pain / I rise”

16. Migration: New and Selected Poems by W.S. Merwin (1927-2019)

Excerpt: “I want to tell what the forests / were like / I will have to speak / in a forgotten language”

17. Selected Poems by Frank O’Hara (1926–1966)

Excerpt: “ there is no snow in Hollywood / there is no rain in California / I have been to lots of parties / and acted perfectly disgraceful / but I never actually collapsed / oh Lana Turner we love you get up”

18. Selected Poems by Langston Hughes (1901–1967)

Excerpt: “O, sweep of stars over Harlem streets / O, little breath of oblivion that is night. / A city building / to a mother’s song. / A city dreaming / to a lullaby.”

19. Ariel by Sylvia Plath (1932–1963)

Excerpt: “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / and eat men like air”

20. The Collected Poems by Audre Lorde (1934–1992)

Excerpt: “But if it’s said / at some future date / that my son’s head / is on straight / he won’t care / about his / hair / nor give a damn / whose wife / I am.”

21. Diving Into The Wreck by Adrienne Rich (1929–2012)

Excerpt: "I came to explore the wreck. / The words are purposes. / The words are maps. / I came to see the damage that was done / and the treasures that prevail."

22. The Essential Neruda: Selected Poems (Bilingual Edition ) by Pablo Neruda (1904 -1973)

Excerpt: “Leaning into the evenings I toss my sad nets / to that sea which stirs your ocean eyes.”

23. The Essential Gwendolyn Brooks by Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Excerpt: “We real cool. We / Left school. We / Lurk late. We / Strike straight. We / Sing sin. We / Thin gin. We / Jazz June. We / Die soon.”

24. I Remember by Joe Brainard (1941-1994)

Excerpt: “I remember “close dancing” with arms dangling straight down. / I remember red rubber coin purses / that opened like a pair of lips, with a squeeze.”

25. Passing Through by Stanley Kunitz (1905-2006)

Excerpt: "In my sixty-fourth year / I can feel my cheek / still burning."

26. The Collected Poems 1912-1944 by H.D. (1886–1961)

Excerpt: “O poplar, you are great/among the hillstones, / while I perish on the path / among the crevices of the rocks.”

27. The Selected Poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892–1950)

Excerpt: “My candle burns at both ends / it will not last the night; / But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends — / it gives a lovely light!”

28. The Selected Poems by Federico Garcia Lorca (1898–1937)

Excerpt: “Is this my friend, your twilight constitutional? / Please use your cane,’you are very old Mr. Lizard, / and the children of the village / may startle you.”

29 . The Dream Songs by John Berryman (1914-1972)

Excerpt: “And the tranquil hills, & gin, look like a drag / and somehow a dog/has taken itself & its tail considerably away / into mountains or sea / or sky, leaving / behind: me, wag.”

30. S.O.S. Poems 1961-2013 by Amiri Baraka (1934-2013)

Excerpt : “We came into the / silly little church / shaking our wet raincoats / on the floor. / It wasn’t water, / that made the raincoats / wet.”

31. Selected Poems by Anna Akhmatova, translated by D.M. Thomas (1889-1966)

Excerpt: “And with you, my first vagary, / I partend. In the east it turned blue. / You said simply: ‘I won’t forget you.’ / I didn’t know at first what you could mean.”

32. Poems of Paul Celan: A Bilingual German/English Edition by Paul Celan (1920-1970), Translated by Paul Hamburger

Excerpt: "Black milk of daybreak we drink it at sundown / we drink it at noon in the morning we drink it at night / we drink and we drink it / we dig a grave in the breezes there one lies unconfined"

33. A Little Larger Than The Entire Universe: Selected Poems by Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935)

Excerpt: “I believe in the word as in a daisy, / Because I see it. But I don’t think about it, / Because to think is to not understand.”

34 . The Complete Poems by Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979)

Excerpt: “The art of losing isn’t hard to master; / so many things seem filled with the intent / to be lost that their loss is no disaster. / Lose something every day. Accept the fluster / of lost door keys, the hour badly spent. / The art of losing isn’t hard to master.”

35. Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror by John Ashbery (1927–2017)

Excerpt: “A breeze like the turning of a page / Brings back your face: the moment / Takes such a big bite out of the haze / Of pleasant intuition it comes after.”

Best Poetry Books By Living Writers

36. citizen: an american lyric by claudia rankine (1963–).

Excerpt: “You tell your neighbor that your friend, whom he has met, is babysitting. He says no, it’s not him. He’s met your friend and this isn’t that nice young man. Anyway, he wants you to know, he’s called the police.”

37. A Beautiful Marsupial Afternoon by CA Conrad (1966–)

Excerpt: “is it time to become unreasonable? / yes it’s time to become unreasonable!”

38. Felt by Alice Fulton (1952–)

Excerpt: “She dismantled ground and figure / till the fathoms were ambiguous — / a sentence left unfinished / because everyone knows what’s meant,”

39. Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

Excerpt: “does it matter how he got here if we’re all here / to dance? grab a boy! spin him around! / if he asks for a kiss, kiss him. / if he asks where he is, say gone”

40. Oceanic by Aimee Nezhukumatathil (1974–)

Excerpt: “ And that’s how you feel after tumbling / like sea stars on the ocean floor over each other. / A night where it doesn’t matter / which are arms or which are legs / or what radiates and how — / only your centers stuck together.”

41. Night Sky With Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong (1988–)

Excerpt: “Your father is only your father / until one of you forgets. Like how the spine / won’t remember its wings / no matter how many times our knees / kiss the pavement.”

42. There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyonce by Morgan Parker (1988 –)

Excerpt: “What kind of bodies are movable / and feasts. What color are visions / When he opens his mouth / a chameleon is inside, starving.”

43. Life On Mars by Tracy K. Smith (1972–)

Excerpt: “ You lie there kicking like a baby, waiting for God himself / To lift you past the rungs of your crib. What / Would your life say if it could talk?”

44. Autobiography of Red by Anne Carson (1950 –)

Excerpt: “Geryon’s dream began red then slipped out of the vat and ran / Upsail broke silver shot up through his roots like a pup / Secret pup At the front end of another red day”

45. All The Garbage Of The World Unite! By Kim Kyesoon (1955–)

Excerpt: “ Have you ever swallowed a tornado? / A tornado is supposed to be swallowed / through your backbone / My body flips over / my hair becomes as stiff as frozen laundry / and I feel goose bumps down my backbone”

46. Words Under The Words: Selected Poems by Naomi Shihab Nye (1952 –)

Excerpt: "What makes a man with a gun seem bigger / than a man with almonds?”

47. bury it by sam sax (1986–)

Excerpt: “I only want the world / to end when I’m done / with it”

48. A Sand Book by Ariana Reienes (1982 – )

Excerpt: “They taught us the world / Was ending but they were wrong / They hardly taught us anything / Hiding themselves / In the cantaloupe / Light at the witching / Hour.”

49. Picture Bride by Cathy Song (1955–)

Excerpt: “Wahiawa is still / a red dirt town/ where the sticky smell / of pineapples / being lopped off/ in the low-lying fields / rises to mix /with the minty leaves / of eucalyptus/ in the bordering gulch.”

50. When My Brother Was An Aztec by Natalie Diaz

Excerpt: “Angels don’t come to the reservation./Bats, maybe, or owls. Boxy mottled things. / Coyotes too. They all mean the same thing — / death. And death/eats angels I guess, because I haven’t seen an angel/fly through this valley ever.”

51. The Descent of Alette by Alice Notley (1945–)

Excerpt: ““One day, I awoke” “& found myself on” “a subway, endlessly” / “I didn’t know” “how I’d arrived there or” “who I was exactly””

52. Sleeping with the Dictionary by Haryette Mullen (1953–)

Excerpt: You are a U-boat beyond my mind control / You are euthanasia beyond my miasma / You are a urethra beyond my Mysore.”

53. Hanging On Our Own Bones by Judy Grahn (1940–)

Excerpt: “ We were driving home slow, my lover and I / across the long Bay Bridge / one February midnight when midway / over in the far left lane, I saw a strange scene.”

54. A Bernadette Mayer Reader by Bernadette Mayer (1945–)

Excerpt: “Nowadays you guys settle for a couch / By a soporific color cable t.v. set / Instead of any arc of love, no wonder / The G.I. Joe team blows it every other time”

55. Neon Vernacular: New And Selected Poems by Yusef Komunyakaa (1947–)

Excerpt: “That’s the oak I planted / The day before I left town / As if father and son / Needed staking down to earth.”

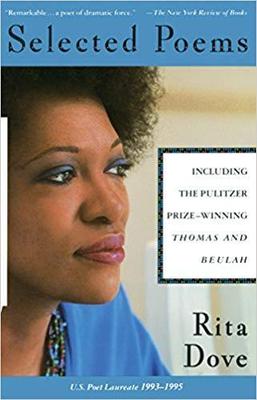

56. Selected Poems by Rita Dove (1952 –)

Excerpt: “I was ill, lying on my bed of old papers / when you came with white rabbits in your arms; / and the doves scattered upwards, flying to mothers / and the snails sighed under their baggage of stone…”

57. Half Light: Collected Poems 1965-2016 by Frank Bidart (1939–)

Excerpt: “The love I’ve known is the love of / two people staring/ not at each other but in the same direction.”

Best Poetry Anthologies

58. sing: poetry from the indigenous americas edited by allison adelle hedge coke.

59. Gurlesque edited by Lara Glenum and Arielle Greenberg

60. The Norton Anthology of Poetry edited by Margaret Ferguson, Mary Jo Salter, and Jon Stallworthy

61. The BreakBeat Poets: New American Poetry in the Age of Hip-Hop edited by Kevin Coval, Quraysh Ali Lansana, and Nate Marshall

Looking for other types of collections to sink your teeth into? Check out these must-read short story compilations.

Continue reading

More posts from across the blog.

The 20 Best Places to Find Cheap Books Online

Finding cheap books online is quick and easy when you know where to look; lucky for you, we’ve done the research to bring you 20 of the best online bookstores.

All the Harry Potter Books in Order: Your J.K. Rowling Reading List

Of all the zeitgeist-defining fiction to come out of the past twenty years, perhaps none has been more universally beloved than the Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling. An incredibly imag...

Launching Your Book on Reedsy Discovery

Whether you’re self-publishing a book for the first time or you’re a veteran indie author, the idea of launching a book is always going to be a little daunting. After all, there are a lot of moving pieces and you only ...

Heard about Reedsy Discovery?

Trust real people, not robots, to give you book recommendations.

Or sign up with an

Or sign up with your social account

- Submit your book

- Reviewer directory

Free Course: Spark Creativity With Poetry

Learn to harness the magic of poetry and enhance your writing.

Advertisement

Supported by

The Best Poetry of 2020

- Share full article

By Elisa Gabbert

- Dec. 12, 2020

I’m uncomfortable using the word “best” on a list — in part because I am just one person whose tastes are subjective. More so, to me it implies that I’ve read every book that came out in 2020 and can therefore rank them like brands of peanut butter (which seem more finite). I didn’t read them all, or even close — I wish my life made that possible. Still, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to talk about some poetry books that I loved this year. My column gives me limited space, so apart from the books I’ve already had a chance to recommend (like Don Mee Choi’s National Book Award-winning “DMZ Colony ” or Chessy Normile’s great debut ), here are several collections that I wasn’t able to write about in full or otherwise feel deserve more attention.

AFRICAN AMERICAN POETRY: 250 YEARS OF STRUGGLE AND SONG , edited by Kevin Young. (Library of America, 1,110 pp., $45.) One of the most exciting anthologies I’ve opened in years, this volume collects work from the earliest days of the African-American poetic tradition (opening with a poem by Phillis Wheatley, who was renamed, as Young writes in the introduction, “after the ship that stole her”) through Emancipation, the Harlem and Chicago Renaissances, the Black Arts Movement and the Dark Room Collective, and bringing us into the 21st century. As Parul Sehgal notes in her review for The Times , the poems “slyly annotate one another” within and across eras. Angelina Weld Grimké’s image of a “straight black cypress” as a “finger / Pointing upwards” prefigures Gwendolyn B. Bennett’s memory of distant “slim palm-trees, / Pulling at the clouds / With little pointed fingers” and both prefigure the fingers in poems by Jericho Brown (“We thought / Fingers in dirt meant it was our dirt”) and Tiana Clark (“Tracing my / finger along the boomerang shape of the Niger River for my blood … red finger pointing up at my dead”), written almost a century later. A wonderful reference, a wonderful gift.

ARENA, by Lauren Shapiro. (Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 79 pp., paper, $18.) I’m one of those people who prefer sad music when they’re sad, and sad poetry too — someone else’s pain to harmonize with mine. These poems revolve around a single terrible moment (“I was getting a haircut when I received the call. Then I kept receiving it forever”), a reminder of poetry’s filmic ability to slow and stop time: “I opened my arms / to touch the beautiful butterflies / as they landed like leaves coming back / to a dead tree. I was the tree. / I could only understand the present. / I can only understand the present.”

CARDINAL , by Tyree Daye. (Copper Canyon, 57 pp., paper, $16.) A slim collection of beautiful poems about moving (leaving, returning, remembering) — “cardinal” as in the bird but also as in direction. The poems echo one another, with the title of one appearing as a line in another, and echo poetry in general, borrowing lines from Whitman, Rilke, Larry Levis. “The dead know / the work they have done, / and if they are not careful their hands / will stay in the shape of that work.” Among the poems are what appear to be family photographs (slightly blurry, like memories), which deepen the feeling of the book as both elegy and archive.

EMPORIUM , by Aditi Machado. (Nightboat, 112 pp., paper, $16.95.) “Wordplay” isn’t quite the term for what’s going on here; it’s more like linguistic athleticism. If you always choose Scrabble over Risk, crosswords over sudoku, you’ll get so much pleasure from the rhymes and slant rhymes (“The body is pronounced bawdy”; “It’s like innocence way off / in the distance”), double and triple meanings, conjugations and declensions, repetitions that evoke a sense of déjà vu — “Fold this” or “Fold it” or “I fold,” etc., occurs as a refrain that seems to half-reset things, like cutting a deck of cards, or twisting them into a Möbius strip. “The camera is deft, so I am dire. / I look into the mounting of desire … surely, the darkness, metonymic, shall / proceed. / I fold this.”

INHERITANCE , by Taylor Johnson. (Alice James, 69 pp., paper, $18.95.) The voice of these poems hooked me right away — poised between conversational and elevated, with a kind of elegant swagger. Johnson writes about longing and “impossible desire,” about poverty and precarity (“No one like me gets old, or so I thought, even as I watched the days fade into each other. / Was I no one?”), about the struggle and joy of becoming oneself: “Every day I build the little boat … O New Day, I get to build the boat! / I tell myself to live again.”

MUSIC FOR THE DEAD AND RESURRECTED, by Valzhyna Mort. (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 95 pp., $25.) A child in Belarus bears the weight of an accordion and countless repetitive war stories, nightmares of blood and bones and radioactive soil. Mort’s poems tell a secret history (“Silence beats language out of us”); they have the haunting quality of a nursery rhyme in a minor key, the dark magic of a snow-dusted forest. “I, too, am meat braided into a string of thought. / I pray to the trees.”

MY DAILY ACTIONS, OR THE METEORITES , by S. Brook Corfman. (Fordham University, 70 pp., paper, $22.) Poems of fear and foreboding that live with the knowledge of climate crisis, without resorting to self-righteousness or self-flagellation. The form is mostly prose blocks, built of elusive, mysteriously fascinating sentences that often hinge on apparent contradiction, the simultaneity of seemingly opposite states: “Even if Tuxedo Mask kissed me back to life, all Endymion, I think I would stay dead.” “I am a bad imitator and yet this is a good imitation.” “It is hard to talk about. And yet I have filled a notebook.”

WICKED ENCHANTMENT: SELECTED POEMS , by Wanda Coleman. (Black Sparrow, 221 pp., $25.95.) I came to Wanda Coleman through Terrance Hayes, who took her “American Sonnet” form as inspiration for the poems in his own book “American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin” — so I was happy to see that he edited and introduced this new selection of her work in verse (she also wrote fiction and nonfiction) across 20 or so years of her career. These poems are wildly fun and inventive, in the manner of Lewis Carroll or César Vallejo, and frequently hilarious; they seem to cover every human experience and emotion (often anger or just annoyance), as well as states that blur the line between experience and emotion, like pregnancy (“i’m 99% body”), horniness, the freedom of driving a car, perseverance (“i will. with difficulty / but i will”). I love the way she uses a line break so it’s not quite enjambment and not quite an end stop — “i want to go home and wonder how long it’ll take me to hoof it / maybe twenty minutes” — invisible punctuation.

Elisa Gabbert is the author of five collections of poetry, essays and criticism, most recently “ The Unreality of Memory & Other Essays .” Her On Poetry columns appear four times a year.

Follow New York Times Books on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram , s ign up for our newsletter or our literary calendar . And listen to us on the Book Review podcast .

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

New Orleans is a thriving hub for festivals, music and Creole cuisine. The novelist Maurice Carlos Ruffin shared books that capture the city’s many cultural influences .

Joseph O’Neill’s fiction incorporates his real-world interests in ways that can surprise even him. His latest novel, “Godwin,” is about an adrift hero searching for a soccer superstar .

Keila Shaheen’s self-published best seller book, “The Shadow Work Journal,” shows how radically book sales and marketing have been changed by TikTok .

John S. Jacobs was a fugitive, an abolitionist — and the brother of the canonical author Harriet Jacobs. Now, his own fierce autobiography has re-emerged .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Poetry & Poets

Explore the beauty of poetry – discover the poet within

What Is Abstract Poetry

Definition of Abstract Poetry

Abstract poetry is a style of verse which is experimental and abstract, often departing from the conventions of and definitions of traditional poetic forms. It makes use of fleeting and intangible concepts and the means of expression are often loose and open to interpretation. Generally, it is deemed a more cerebral style of poetry, demanding the engagement of the reader to approach new concepts and view the poem in a bigger and more imaginative context.

History of Abstract Poetry

Abstract Poetry has its roots in ancient literature, as many poets through the ages sought to break traditional conventions of poetic language and structure. Such figures as Gertrude Stein and T.S. Eliot are credited with the modern conception of abstract poetry, as they both pushed the boundaries of the form and created works which were focused on embodying intangible things, such as feelings and ideas. Since then, the style of abstract poetry has been applied to many genres, such as rap and spoken word.

Characteristics of Abstract Poetry

Abstract Poetry is, at its heart, an exploration of concepts that transcend traditional language and thought. It is often quite esoteric, in that the focus of the poem is on aspects of the subject which are not immediately noticeable or tangible, such as how a feeling or emotion can be translated into word. Abstract Poetry will also often contain metaphors, allusions, similes and other literary devices to create vivid and evocative language.

Contemporary Uses of Abstract Poetry

Today, abstract poetry is still a powerful form of expression, often used to question the norms of societal structures and to create thought-provoking questions about the world and beyond. Furthermore, it is still a popular form of poetry for performance, allowing for an emotional and intense connection between the poet and their audience.

Examples of Abstract Poetry

The most famous example of abstract poetry is probably T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’, a poem which encapsulates the feeling of spiritual barrenness in the modern world. Similarly, Walt Whitman is well known for his work ‘Leaves of Grass’, a highly abstract and contemplative text which uses large sweeping metaphors in order to explore the human condition.

The Impact of Abstract Poetry

Abstract Poetry has had a profound impact on modern poetry and literature as a whole. Not only has it helped to expand the scope of poetic expression, but it has also pushed poets to think more deeply about the world and to view it in new ways. Furthermore, its popularity has led to more experimental forms of poetry being developed, such as free verse and post-modern poetry.

Criticism of Abstract Poetry

One criticism of abstract poetry is that it can often be overly esoteric, making it difficult to decipher or understand. Furthermore, some have argued that it is too far removed from reality, making it inaccessible to those who are not well versed in literary jargon. Another criticism that it has encountered is that it often lacks structure and a clear message, leading to readers becoming divorced from the poem.

The Role of the Reader in Abstract Poetry

Abstract Poetry often requires its reader to take an active role in order to understand the poem in the way it was intended. This is because the language often relies on connotations and intangible imagery, which requires more liberal interpretations in order to truly grasp the poet’s thought process. It is this engagement with the poem which makes it such a powerful form of expression, as it forces the reader to think outside of convention and to question the ideas of a text.

The Use of Emotion in Abstract Poetry

Abstract Poetry also makes great use of emotional triggers in order to evoke a response from the reader. Whether it comes in the form of a vivid metaphor or an allusion to a deeply held belief, the aim of the poet is to captivate the reader into their world of thought. Thus, the reader is then invited to connect with the poem on an emotional level, getting wrapped up in the message of the work and exploring the implications of it on a deeper level.

How to Write an Abstract Poem

Writing an abstract poem can be a daunting endeavour. However, it is achievable once a few key factors are taken into account. Firstly, it is important to think of the poem as an exploration of ideas and feelings, rather than a traditional story. Secondly, it is important to draw on any experiences or situations which are personally relevant for the poet. Once these have been established, it should be possible to craft a poem which is abstract and personal.

Purpose of Abstract Poetry

The main purpose of Abstract Poetry is not just to entertain, but to make the reader think. A good abstract poem should be able to capture the essence of an idea or emotion without relying on tangible objects or concepts. Furthermore, it should be written in a manner which encourages the reader to probe the poem’s underlying message and to come away with a deeper understanding of the poet’s viewpoint.

Challenges of Abstract Poetry

Writing an abstract poem is not an easy task, as the poet needs to carefully craft language which can be interpreted in many different ways. By embracing ambiguity, the poet must be able to communicate a unique theme without needing direct references or practical examples. Furthermore, they must often take into account the reader’s own feelings when reading the poem and make sure they do not become overwhelmed or confused by its complexities.

Techniques of Abstract Poetry

In order to write an effective abstract poem, poets should keep the following techniques in mind. Firstly, they should use vivid and evocative language and imagery in order to draw in the reader and make them feel as though they are a part of the poem. Secondly, they should try to create an atmosphere of ambiguity to ensure the poem has multiple interpretations. Thirdly, they should think of the poem as a way to bring out the emotions and ideas of their inner self and use unconventional language when expressing these.

The Influence of Abstract Poetry

Abstract Poetry has had a significant influence on modern culture and literature, as it has encouraged people to think outside of the box and to view the world from an alternative perspective. It has allowed for greater expression of emotions and ideas, as it does not rely on traditional language and conventions. As such, it can be seen as an important way for people to communicate their thoughts in a manner which makes them much more accessible to others.

Legacy of Abstract Poetry

The legacy of Abstract Poetry is assured, as it has allowed poets to express their thoughts in a variety of ways. By giving them the freedom to explore ideas which are not often discussed or seen in conventional poetry, it has been able to expand the scope of what is possible with the form. Furthermore, its popularity has also led to more experimental and unique forms of art being produced, as it has opened up a new world of expression to writers and artists alike.

Dannah Hannah is an established poet and author who loves to write about the beauty and power of poetry. She has published several collections of her own works, as well as articles and reviews on poets she admires. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in English, with a specialization in poetics, from the University of Toronto. Hannah was also a panelist for the 2017 Futurepoem book Poetry + Social Justice, which aimed to bring attention to activism through poetry. She lives in Toronto, Canada, where she continues to write and explore the depths of poetry and its influence on our lives.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Abstract Poetry Form: Dream in Absurdity

Here’s what the Abstract (sound) poetry form is:

Abstract poetry or sound poetry relies entirely on the aural quality of the poems produced, often to the complete or partial exclusion of meaning and/or narrative.

Abstract poems were first popularized as an idea by Edith Sitwell, though the concept of sound has always been entwined with poetry to some extent.

So if you want to learn all about the Abstract poetry type, then you’ve come to the right place.

Let’s jump into it!

- Clerihew Poetry Form: Chuckle Through Lines

Types of Poetry: Abstract Poetry

Abstract poetry relies entirely on the sound the poem makes, rather than on the meanings of the individual words.

This is often referred to as the poem’s “aural quality.” For this reason, the genre is sometimes also referred to as sound poetry.

It should be noted that the term “abstract poetry” is sometimes used to refer to poetry that lacks meaning or narrative, but this is not completely congruent with the view we’ll be taking today.

While abstract poems do focus more on sound than on meaning, it’s possible for an abstract poem to have a narrative of some sort still, though it may be nonsensical.

Because of this, there are some instances where a poem’s inclusion or exclusion in the genre is up for debate.

This is because the genre itself tends to be more subjective than objective, except in specific examples where the poem was clearly only interested in sound.

Basic Properties of Abstract Poetry

What Are the Key Features of Abstract Poetry?

Phonetic techniques like rhyme and alliteration are prevalent in abstract poetry, though no one technique or combination of techniques is expected.

Rather than having any prescribed forms or conventions, abstract poetry is essentially a branch of free verse that focuses on bringing musical qualities to the poem.

They can be compared to terms like avant-garde or modern art, in that abstract poems often defy easy categorization and formulaic construction.

Abstract poems discard most of the theory that goes into writing traditional poetry.

Imagery and narrative might be present but are not necessarily the focal point of the poem.

Because of their sound-based qualities, it’s fairly common for abstract poetry to be relegated to oral presentations.

An abstract poem achieves its true form when it’s spoken out loud. Some poets take this to the extreme, only releasing abstract poems in recordings as performance pieces, though this is uncommon.

The thing that makes abstract poetry so resistant to definition is that it exists less as a clear and static denotation and more as a sort of spectrum.

Since most poets experiment with phonetic techniques on some level, it’s hard to grasp a clear cut-off point where a poem leans far enough toward the sound and away from meaning to be considered abstract.

Example of an Abstract Poem

from Popular Song by Edith Sitwell

Lily O’Grady, Silly and shady, Longing to be A lazy lady, Walked by the cupolas, gables in the Lake’s Georgian stables, In a fairy tale like the heat intense, And the mist in the woods when across the fence The children gathering strawberries Are changed by the heat into Negresses, Though their fair hair Shines there

The above excerpt from the beginning of “Popular Song” premiered in Edith Sitwell’s Façade.

In this example, we see that there is some semblance of narrative, at least, but it’s clearly not the focus.

Instead, the poem relies heavily on rhyming and repeating sounds, often making huge leaps between lines that can make the narrative difficult to follow.

This is fine, however, since the narrative largely isn’t the point.

If a listener completely glossed over the narrative only to enjoy the continuous barrage of sounds, then the poem will have done its job.

An abstract poem need only be entertaining.

This example was chosen because it represents one of the most infamous pieces of abstract poetry to date.

Façade was violently hated by critics and even its own performers when it was first performed and became a success more by virtue of being a scandal than by any other measure.

Nonetheless, audiences gradually warmed up to Sitwell’s strange new poetry and the collection of poems ultimately became a success over the next several years.

History of Abstract Poetry

Poems that lean more on sound than meaning first started being popularly called abstract poems around the 1920s, thanks to the influence of English poet Edith Sitwell, who first coined the term.

Sitwell was notoriously rebellious, both in her personality and in the nature of her writing, and emerged as a major poet of the era.

Sitwell was a radical opponent of Imagism, using her poetry to emphasize sound instead of meaning.

She was heavily focused on the performance of poetry.

This has some interesting parallels to the origins of poetry since poems were originally a spoken art form rather than a written one.

It’s worth noting that although Edith Sitwell popularized the term, abstract poetry as an idea had existed long before this.

During World War I, the flourishing Dadaist movement had already been experimenting with audio effects, as did Futurists.

Limericks and nursery rhymes had toyed around with similar notions long before any of these movements.

Some writers who have experimented with sound in poetry, to varying degrees, include Hart Crane, Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, and Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

The degree to which their poems fall under the term “abstract” varies.

It’s worth noting that most poets explore sound in their poetry to at least some degree through commonly used techniques like alliteration, assonance, rhyme, and meter.

The difference here is that those phonetic techniques become the defining feature of the poem, sometimes to the exclusion of anything else.

It is for this reason that abstract poetry routinely comes under fire from critics.

Sitwell herself enjoyed a distinctly controversial career, with many who attacked her personally and professionally.

Even in the modern era, abstract poetry is fairly uncommon, with many poets jumping on the bandwagon to declare that poems should be built on concrete imagery and metaphors with visual elements.

Tips for Writing Abstract Poems

First, I recommend studying the core features listed previously.

Alliteration, assonance, and rhyme will be your primary weapons. Meter, refrains, and anaphora are your secondary weapons.

Focus on looking for the words that sound the best in a line, even if it means compromising the meaning somewhat.

Let’s explore what I mean by “primary” and “secondary.”

Nearly every abstract poem should feature alliteration, assonance, and/or rhyme.

The repetitions of sounds are critical to the intentions of abstract poetry, so you absolutely should try to employ one or more of these, though there are no absolutes.

As for your “secondary” tools, meter certainly helps with giving a poem an aural quality, but it’s not by any means mandatory.

It might even inhibit the sound in some ways since it makes the poem more predictable.

Refrains and anaphora have a similar purpose to your primary tools, in that they do feature repetition, but repetition of entire sections of the poem can be stale instead of a novel if done poorly.

The easiest way to envision yourself writing abstract poetry is probably as follows.

Have you ever written a rhyming poem and found yourself thinking that you know the perfect word to use as a rhyme but can’t think of any way to include it without making the meaning incomprehensible?

Abstract poetry demands that you use that rhyme by any means necessary.

Does it require you to jump to a whole new train of thought that has nothing to do with the previous line? Do it.

Abstract poetry doesn’t care about your carefully prepared narrative or the deeper meaning that you just have to scratch at.

Abstract poetry requires you to impulsively and abruptly jump toward the next pleasant sound that comes to mind, regardless of what it might do to the poem’s other qualities.

Words like lollipop and babbling are especially valuable since they give you repeated sounds within a single word.

An abstract poem should sound more like a slightly nonsensical piece of music than a traditional poem.

Poet’s Note

“Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven” is perhaps the most visually impressive name I’ve ever seen for a real person.

Truth be told, there were dozens of poets listed in the sources I researched. The baroness mainly made the cut for a mention because, look at that name.

Comprehensive Collection of Poetry Forms: Craft Words Into Art

Dare to traverse the entire spectrum of poetic forms, from the commonplace to the extraordinary?

Venture from the quintessential Sonnet to the elusive Mistress Bradstreet stanza, right through to the daunting complexity of Cro Cumaisc Etir Casbairdni Ocus Lethrannaigecht.

For those with a zeal to encounter the full breadth of poetry’s forms, this invitation is yours.

Start exploring the vast universe of poetic ingenuity with our comprehensive array of poetry forms right now!

The best poetry books of 2024 so far

May: the strongbox by sasha dugdale.

T here has been so much recent poetry inspired by ancient Greece that I’ve wondered whether there’s anything left to say about the myths at all. Alice Oswald’s Nobody (2019) drew on her beloved Homer; Anne Carson’s H of H Playbook (2021) was a wildly inventive translation of Euripides’s Herakles; Fiona Benson’s Ephemeron (2022) deftly retold the Minotaur myth.

I always approach these collections with some trepidation. I’m not so clued up on the myths, and fit into a trend Andrew Motion has said he’s noticed in his students: that as the years go by, he increasingly has to explain what a poem’s classical references meant.

It’s a relief, then, that Sasha Dugdale doesn’t expect readers to have an encyclopaedic knowledge of Homer. Like her last collection, 2020’s Deformations, her sixth volume The Strongbox is heavily inspired by Greek mythology, but draws on easily recognisable figures (Helen, Paris, Cassandra), and with playfulness, not impenetrability. It’s an ambitious work, with 14 sections ranging from reimaginings of Helen of Troy to the rape of Europa by Zeus.

That 14-part structure isn’t as much of a “strongbox” as it looks on the contents page: the narrative thread keeps threatening to escape. “Narrative appals me,” Dugdale writes, “To lay such details out in print / I want to let it wander off the page / But it can only be as it is.”

She has fun with transposing mythological characters to our modern world; the Fates become “three old women” weaving by the “shapeshifting beam of the telly”, while a retelling of the myth of Persephone slips from beautiful lyricism – “Let me exist underground with the iris / slowly opening my pale hands” – to tabloid-esque headlines: “THE DOWNFALL OF A DIVA … DARK TRUTH A MOTHER HID FROM THE WORLD.”

The first section, “Anatomy of an Abduction”, however, feels directly drawn from our world. “With the sun / appearing over the plane wing”, an abducted girl bears strong resemblance to the Isis bride Shamima Begum, “sitting bolt upright / phrasebook on her lap”. As she tries to get inside the girl’s head, Dugdale’s off-rhymes (thanks/phalanx, marriage/hostage) have an appropriately violent feel in the mouth:

did she offer prayers of thanks did she pass between childhood and marriage like a hostage thrown from one phalanx onto the sand.

In her academic life, Dugdale is a translator of Russian and Ukrainian literature, and the “troops” and “drones” that follow feel particularly close to our current moment.

Other sections are more absurd, often told in the form of playscripts: Helen recounts to Paris her dreams; Hermes washes up in our world and is spoken to by a trippy, Keatsian “pair of livid lips”; Menelaus and his wife Helen have an odd arithmetic class. It’s all part of Dugdale’s rejection of narrative as the only means to tell a story, but this experiment might occasionally lose some readers. She pulls off the point better when she directly addresses it, as when an am-dram group gathers in the second section, this “early stage in the rehearsal process”, to decode the first.

Dugdale is at her best when she writes about memory and déjà vu, “the aching sense … Like water / she has been here before”. What if, The Strongbox asks, all our mistakes are just iterations of previous stories, and women like Begum are in some sense successors of Helen? Consider this one beautiful stanza:

And is remembering merely the sudden exposure of a dream? As when the border guard drags film from the camera’s body—is recall the fatal undoing of the sealed?

Such philosophical questions can only be asked sparingly. Another poet might have tried to unify the disparate parts of this collection by deploying more of them, but it’s good that Dugdale didn’t. There can only be a few echoes before a poem becomes lost in its own reverberating cave. It’s this restraint and carefulness that makes Dugdale’s work as strong as its title. LT

April: The Palace of Forty Pillars by Armen Davoudian

Isfahan – currently in the news as the target of Israeli missile strikes – is home to some of Iran’s greatest architectural jewels, among them the misleadingly named “Palace of 40 Pillars”. It has only half that many. The other 20 are an optical illusion, reflections floating in the lake it faces.

There’s a similar architectural sleight-of-hand to Armen Davoudian’s first book. The contents page lists 20 poems, but the title-poem turns out to contain 20 sonnets all on its own – and some of the best I’ve read in quite some time. The book is filled with mirrors and doubles, recurring images (swans abound), divided halves and unusual perspectives.

It’s a reflective collection in every sense; Davoudian looks back on his childhood in Iran, his Armenian family’s history, and a sexual awakening, from the distance of his new life in America. One sonnet begins by describing his grandfather in Iran, before a poignant shift in perspective reveals that he’s only looking at a framed photo: “I mist the glass and clean / away last summer’s promise to return / the coming summer. I’m always going back / on going back.”

Yes, a bunch of who-I-am-and-where-I-come-from poems: so far, so typical for a debut. But as with all good poetry, what matters isn’t so much what is said as how it’s said. And here the how perfectly matches the what, through the formal devices Davoudian deploys, both in his stanzaic forms – the rubaiyat, the ghazal – and line-by-line, where half-rhymes and subtle metrical effects show a good ear that’s only matched by his good nose. (“Saffron Rice” wryly contrasts the “rosewater” worn by a group of “eligible girls” with “the mulish reek / of stiff-necked single young men gangling // over the tittering crowd for O a glimpse / of that one’s ankle”).

The first sonnet from the “Forty Pillars” sequence begins:

Twenty pillars drip into the pool their likenesses, where the likeness of a boy wavers among the clouds, eyeing the boy who’s waiting for another. All is dual: two rows of roses frame the pool, in twos the swans glide, each on another’s breast, then fuse in a headless embrace.

Isn’t there something wickedly audacious about rhyming “boy” with “boy”? The reflection in the water becomes an exact repetition, while the image of one boy looking at another echoes his poems elsewhere about same-sex desire. Throughout, there’s a sense of wanton pleasure in language. Just listen to the line he summons up to describe walking on a Persian rug: “Redundant roses kiss our sockless feet.”

In one sonnet, his car-mechanic father “bends under the open hood, comes up // twenty years younger in another shop.” Davoudian’s not above nicking a good move, in this case from Seamus Heaney. It’s a nod to “Digging”, a

nd Heaney’s father: “His straining rump among the flowerbeds / Bends low, comes up twenty years away”.

Davoudian wears his literary loves on his sleeve. Heaney is joined in his personal pantheon by the sometimes dandyish, sometimes devastating formalism of James Merrill (he replicates the intricate stanza-form of Merrill’s “The Black Swan”); the 20th-century ghazals of Mehdi Hamidi Shirazi (he translates one); and late Auden , who here shares a page, perhaps for the first time, with Osama bin Laden (Davoudian mentions both in a sonnet about “my ill-matched countries”).