When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- SpringerLink shop

Discussion and Conclusions

Your Discussion and Conclusions sections should answer the question: What do your results mean?

In other words, the majority of the Discussion and Conclusions sections should be an interpretation of your results. You should:

- Discuss your conclusions in order of most to least important.

- Compare your results with those from other studies: Are they consistent? If not, discuss possible reasons for the difference.

- Mention any inconclusive results and explain them as best you can. You may suggest additional experiments needed to clarify your results.

- Briefly describe the limitations of your study to show reviewers and readers that you have considered your experiment’s weaknesses. Many researchers are hesitant to do this as they feel it highlights the weaknesses in their research to the editor and reviewer. However doing this actually makes a positive impression of your paper as it makes it clear that you have an in depth understanding of your topic and can think objectively of your research.

- Discuss what your results may mean for researchers in the same field as you, researchers in other fields, and the general public. How could your findings be applied?

- State how your results extend the findings of previous studies.

- If your findings are preliminary, suggest future studies that need to be carried out.

- At the end of your Discussion and Conclusions sections, state your main conclusions once again .

Back │ Next

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 9. The Conclusion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The conclusion is intended to help the reader understand why your research should matter to them after they have finished reading the paper. A conclusion is not merely a summary of the main topics covered or a re-statement of your research problem, but a synthesis of key points derived from the findings of your study and, if applicable, where you recommend new areas for future research. For most college-level research papers, two or three well-developed paragraphs is sufficient for a conclusion, although in some cases, more paragraphs may be required in describing the key findings and their significance.

Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Importance of a Good Conclusion

A well-written conclusion provides you with important opportunities to demonstrate to the reader your understanding of the research problem. These include:

- Presenting the last word on the issues you raised in your paper . Just as the introduction gives a first impression to your reader, the conclusion offers a chance to leave a lasting impression. Do this, for example, by highlighting key findings in your analysis that advance new understanding about the research problem, that are unusual or unexpected, or that have important implications applied to practice.

- Summarizing your thoughts and conveying the larger significance of your study . The conclusion is an opportunity to succinctly re-emphasize your answer to the "So What?" question by placing the study within the context of how your research advances past research about the topic.

- Identifying how a gap in the literature has been addressed . The conclusion can be where you describe how a previously identified gap in the literature [first identified in your literature review section] has been addressed by your research and why this contribution is significant.

- Demonstrating the importance of your ideas . Don't be shy. The conclusion offers an opportunity to elaborate on the impact and significance of your findings. This is particularly important if your study approached examining the research problem from an unusual or innovative perspective.

- Introducing possible new or expanded ways of thinking about the research problem . This does not refer to introducing new information [which should be avoided], but to offer new insight and creative approaches for framing or contextualizing the research problem based on the results of your study.

Bunton, David. “The Structure of PhD Conclusion Chapters.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 4 (July 2005): 207–224; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Conclusion. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

The general function of your paper's conclusion is to restate the main argument . It reminds the reader of the strengths of your main argument(s) and reiterates the most important evidence supporting those argument(s). Do this by clearly summarizing the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem you investigated in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found in the literature. However, make sure that your conclusion is not simply a repetitive summary of the findings. This reduces the impact of the argument(s) you have developed in your paper.

When writing the conclusion to your paper, follow these general rules:

- Present your conclusions in clear, concise language. Re-state the purpose of your study, then describe how your findings differ or support those of other studies and why [i.e., what were the unique, new, or crucial contributions your study made to the overall research about your topic?].

- Do not simply reiterate your findings or the discussion of your results. Provide a synthesis of arguments presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem and the overall objectives of your study.

- Indicate opportunities for future research if you haven't already done so in the discussion section of your paper. Highlighting the need for further research provides the reader with evidence that you have an in-depth awareness of the research problem but that further investigations should take place beyond the scope of your investigation.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is presented well:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize the argument for your reader.

- If, prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the end of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from the data [this is opposite of the introduction, which begins with general discussion of the context and ends with a detailed description of the research problem].

The conclusion also provides a place for you to persuasively and succinctly restate the research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with all the information about the topic . Depending on the discipline you are writing in, the concluding paragraph may contain your reflections on the evidence presented. However, the nature of being introspective about the research you have conducted will depend on the topic and whether your professor wants you to express your observations in this way. If asked to think introspectively about the topics, do not delve into idle speculation. Being introspective means looking within yourself as an author to try and understand an issue more deeply, not to guess at possible outcomes or make up scenarios not supported by the evidence.

II. Developing a Compelling Conclusion

Although an effective conclusion needs to be clear and succinct, it does not need to be written passively or lack a compelling narrative. Strategies to help you move beyond merely summarizing the key points of your research paper may include any of the following:

- If your essay deals with a critical, contemporary problem, warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem proactively.

- Recommend a specific course or courses of action that, if adopted, could address a specific problem in practice or in the development of new knowledge leading to positive change.

- Cite a relevant quotation or expert opinion already noted in your paper in order to lend authority and support to the conclusion(s) you have reached [a good source would be from your literature review].

- Explain the consequences of your research in a way that elicits action or demonstrates urgency in seeking change.

- Restate a key statistic, fact, or visual image to emphasize the most important finding of your paper.

- If your discipline encourages personal reflection, illustrate your concluding point by drawing from your own life experiences.

- Return to an anecdote, an example, or a quotation that you presented in your introduction, but add further insight derived from the findings of your study; use your interpretation of results from your study to recast it in new or important ways.

- Provide a "take-home" message in the form of a succinct, declarative statement that you want the reader to remember about your study.

III. Problems to Avoid

Failure to be concise Your conclusion section should be concise and to the point. Conclusions that are too lengthy often have unnecessary information in them. The conclusion is not the place for details about your methodology or results. Although you should give a summary of what was learned from your research, this summary should be relatively brief, since the emphasis in the conclusion is on the implications, evaluations, insights, and other forms of analysis that you make. Strategies for writing concisely can be found here .

Failure to comment on larger, more significant issues In the introduction, your task was to move from the general [the field of study] to the specific [the research problem]. However, in the conclusion, your task is to move from a specific discussion [your research problem] back to a general discussion framed around the implications and significance of your findings [i.e., how your research contributes new understanding or fills an important gap in the literature]. In short, the conclusion is where you should place your research within a larger context [visualize your paper as an hourglass--start with a broad introduction and review of the literature, move to the specific analysis and discussion, conclude with a broad summary of the study's implications and significance].

Failure to reveal problems and negative results Negative aspects of the research process should never be ignored. These are problems, deficiencies, or challenges encountered during your study. They should be summarized as a way of qualifying your overall conclusions. If you encountered negative or unintended results [i.e., findings that are validated outside the research context in which they were generated], you must report them in the results section and discuss their implications in the discussion section of your paper. In the conclusion, use negative results as an opportunity to explain their possible significance and/or how they may form the basis for future research.

Failure to provide a clear summary of what was learned In order to be able to discuss how your research fits within your field of study [and possibly the world at large], you need to summarize briefly and succinctly how it contributes to new knowledge or a new understanding about the research problem. This element of your conclusion may be only a few sentences long.

Failure to match the objectives of your research Often research objectives in the social and behavioral sciences change while the research is being carried out. This is not a problem unless you forget to go back and refine the original objectives in your introduction. As these changes emerge they must be documented so that they accurately reflect what you were trying to accomplish in your research [not what you thought you might accomplish when you began].

Resist the urge to apologize If you've immersed yourself in studying the research problem, you presumably should know a good deal about it [perhaps even more than your professor!]. Nevertheless, by the time you have finished writing, you may be having some doubts about what you have produced. Repress those doubts! Don't undermine your authority as a researcher by saying something like, "This is just one approach to examining this problem; there may be other, much better approaches that...." The overall tone of your conclusion should convey confidence to the reader about the study's validity and realiability.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8; Concluding Paragraphs. College Writing Center at Meramec. St. Louis Community College; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Leibensperger, Summer. Draft Your Conclusion. Academic Center, the University of Houston-Victoria, 2003; Make Your Last Words Count. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin Madison; Miquel, Fuster-Marquez and Carmen Gregori-Signes. “Chapter Six: ‘Last but Not Least:’ Writing the Conclusion of Your Paper.” In Writing an Applied Linguistics Thesis or Dissertation: A Guide to Presenting Empirical Research . John Bitchener, editor. (Basingstoke,UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), pp. 93-105; Tips for Writing a Good Conclusion. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Conclusion. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; Writing Conclusions. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Writing: Considering Structure and Organization. Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Writing Tip

Don't Belabor the Obvious!

Avoid phrases like "in conclusion...," "in summary...," or "in closing...." These phrases can be useful, even welcome, in oral presentations. But readers can see by the tell-tale section heading and number of pages remaining that they are reaching the end of your paper. You'll irritate your readers if you belabor the obvious.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8.

Another Writing Tip

New Insight, Not New Information!

Don't surprise the reader with new information in your conclusion that was never referenced anywhere else in the paper. This why the conclusion rarely has citations to sources. If you have new information to present, add it to the discussion or other appropriate section of the paper. Note that, although no new information is introduced, the conclusion, along with the discussion section, is where you offer your most "original" contributions in the paper; the conclusion is where you describe the value of your research, demonstrate that you understand the material that you’ve presented, and position your findings within the larger context of scholarship on the topic, including describing how your research contributes new insights to that scholarship.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

- << Previous: Limitations of the Study

- Next: Appendices >>

- Last Updated: May 21, 2024 11:14 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

The Conclusion: How to End a Scientific Report in Style

- First Online: 26 April 2023

Cite this chapter

- Siew Mei Wu 3 ,

- Kooi Cheng Lee 3 &

- Eric Chun Yong Chan 4

868 Accesses

Sometimes students have the mistaken belief that the conclusion of a scientific report is just a perfunctory ending that repeats what was presented in the main sections of the report. However, impactful conclusions fulfill a rhetorical function. Besides giving a closing summary, the conclusion reflects the significance of what has been uncovered and how this is connected to a broader issue. At the very least, the conclusion of a scientific report should leave the reader with a new perspective of the research area and something to think about.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Writing and publishing a scientific paper

Too good to be true?

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

Goh, Z.-H., Tee, J. K., & Ho, H. K. (2020). An Evaluation of the in vitro roles and mechanisms of silibinin in reducing pyrazinamide and isoniazid-induced hepatocellular damage. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21 , 3714–3734. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21103714

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Swales, J. M., & Feak, C. B. (2012). Academic writing for graduate students (3rd ed.). University of Michigan Press.

Book Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for English Language Communication, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

Siew Mei Wu & Kooi Cheng Lee

Pharmacy, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

Eric Chun Yong Chan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Siew Mei Wu .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Chemical and Molecular Biosciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Susan Rowland

School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Louise Kuchel

Appendix 1: Tutorial Notes for Conclusion Activity

1.1 learning outcomes.

At the end of the tutorial, you should be able to:

Identify and demonstrate understanding of the roles of Conclusion section of research reports

Analyze the rhetorical moves of Conclusion and apply them effectively in research reports

1.2 Introduction

The Conclusion of a paper is a closing summary of what the report is about. The key role of a Conclusion is to provide a reflection on what has been uncovered during the course of the study and to reflect on the significance of what has been learned (Craswell & Poore, 2012). It should show the readers why all the analysis and information matters.

Besides having a final say on the issues in the report, a Conclusion allows the writer to do the following:

Demonstrate the importance of ideas presented through a synthesis of thoughts

Consider broader issues, make new connections, and elaborate on the significance of the findings

Propel the reader to a new view of the subject

Make a good final impression

End the paper on a positive note

(University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2019)

In other words, a Conclusion gives the readers something to take away that will help them see things differently or appreciate the topic in new ways. It can suggest broader implications that will not only interest the readers, but also enrich their knowledge (Craswell & Poore, 2012), and leave them with something interesting to think about (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2019).

1.3 About the Conclusion Section

In most universities, undergraduate students, especially those in the last year of their programs, are required to document their research work in the form of a research report. The process of taking what you have done in the lab or from systematic review, and writing it for your academic colleagues is a highly structured activity that stretches and challenges the mind. Overall, a research paper should appeal to the academic community for whom you are writing and should cause the reader to want to know more about your research.

As an undergraduate student in your discipline, you have the advantage of being engaged in a niche area of research. As such, your research is current and will most likely be of interest to scholars in your community.

A typical research paper has the following main sections: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. The other front and back matters of a research paper are the title, abstract, acknowledgments, and reference list. This structure is commonly adopted and accepted in the scientific fields. The research report starts with a general idea. The report then leads the reader to a discussion on a specific research area. It then ends with applicability to a bigger area. The last section, Conclusion, is the focus of this lesson.

The rhetorical moves of a Conclusion reflect its roles (see Fig. 54.1 ). It starts by reminding the reader of what is presented in the Introduction. For example, if a problem is described in the Introduction, that same problem can be revisited in the Conclusion to provide evidence that the report is helpful in creating a new understanding of the problem. The writer can also refer to the Introduction by using keywords or parallel concepts that were presented there.

Rhetorical moves of Conclusion (the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Writing Center,2019)

Next is a synthesis and not a summary of the outcomes of the study. Ideas should not simply be repeated as they were in the earlier parts of the report. The writer must show how the points made, and the support and examples that were given, fit together.

In terms of limitations, if it is not already mentioned in the Discussion section, the writer should acknowledge the weaknesses and shortcomings in the design and/or conduct of the study.

Finally, in connecting to the wider context, the writer should propose a course of action, a solution to an issue, or pose questions for further study. This can redirect readers’ thoughts and help them apply the information and ideas in the study to their own research context or to see the broader implications of the study.

1.4 Linguistic Features of the Conclusion Section

In terms of linguistic features, the use of tense in the Conclusion section is primarily present where the writer’s voice, position, and interpretation are prominent. This is followed by the use of the future tense in sharing what is ahead and some use of past when referring to the study that was done. As summarized by Swales and Feak (2012), Table 54.1 presents the frequency of use of the present tense and past tense in a research report.

1.5 Writing the Conclusion Section

Often, writing a Conclusion is not as easy as it first seems. Using the Question and Answer approach, below is a description of what is usually included in the Conclusion section.

How long should the Conclusion be?

One or two paragraphs comprising 1 sentence summarizing what the paper was about

Two to three sentences summarizing and synthesizing the key findings related to the thesis or objectives of the study

One sentence on limitations (if not in Discussion)

One to two sentences highlighting the significance and implications

One sentence on potential directions for further research

Should the objective be referred to in a Conclusion?

An effective Conclusion reiterates the issue or problem the hypothesis or objective(s) set out to solve. It is important to remind the readers what the hypothesis or objective(s) of the report are and to what extent they are addressed

How far should the Conclusion reflect the Introduction?

Referring to points made in the Introduction in the conclusion ties the paper together and provides readers with a sense of closure.

How much summarizing should there be in a Conclusion?

The conclusion can loosely follow the organization of your paper to parallel, but the focus should be on the paper’s analysis rather than on the organization.

Should newly found information be added to a Conclusion?

Well-written conclusions do not bring in new information or analysis; instead, they sum up what is already contained in the paper.

(Bahamani et al., 2017; Markowsky, 2010)

1.6 Task: Analysing a Conclusion Section

Consider Examples 1 to 4. How do the writers communicate the following information?

Restatement of objective(s)

Refection of outcome(s)

Acknowledgment of limitations, if any

Connection to wider context

“According to this study, the use of educational models, such as a Precaution Adoption Process Model (PAPM) that most people are associated with the process of decision-making in higher education will be beneficial. Moreover, in the preparation, development and implementation of training programs, factors like increased perceived susceptibility, and perceived benefits should be dealt with and some facilities should be provided to facilitate or resolve the barriers of doing the Pap smear test as much as possible.”

(Bahamani et al., 2016)

“Community pharmacists perceived the NMS service as being of benefit to patients by providing advice and reassurance. Implementation of NMS was variable and pharmacists’ perceptions of its feasibility and operationalisation were mixed. Some found the logistics of arranging and conducting the necessary follow-ups challenging, as were service targets. Patient awareness and understanding of NMS was reported to be low and there was a perceived need for publicity about the service. NMS appeared to have strengthened existing good relationships between pharmacists and GPs. Some pharmacists’ concerns about possible overlap of NMS with GP and nurse input may have impacted on their motivation. Overall, our findings indicate that NMS provides an opportunity for patient benefit (patient interaction and medicines management) and the development of contemporary pharmacy practice.”

(Lucas & Blenkinsopp, 2015)

“In this review, we discussed several strategies for the engineering of RiPP pathways to produce artificial pep-tides bearing non-proteinogenic structures characteristic of peptidic natural products. In the RiPP pathways, the structures of the final products are defined by the primary sequences of the precursor genes. Moreover, only a small number of modifying enzymes are involved, and the enzymes function modularly. These features have greatly facilitated both in vivo and in vitro engineering of the pathways, leading to a wide variety of artificial derivatives of naturally occurring RiPPs. In principle, the engineering strategies introduced here can be interchangeably applied for other classes of RiPP enzymes/pathways. Post-biosynthetic chemical modification of RiPPs would be an alternative approach to further increase the structural variation of the products [48–50]. Given that new classes of RiPP enzymes have been frequently reported, and that genetic information of putative RiPP enzymes continues to arise, the array of molecules feasible by RiPP engineering will be further expanded. Some of the artificial RiPP derivatives exhibited elevated bioactivities or different selectivities as compared with their wild type RiPPs. Although these precedents have demonstrated the pharmaceutical relevance of RiPP ana-logs, the next important step in RiPP engineering is the development of novel RiPP derivatives with artificial bioactivities. In more recent reports [51 __,52 __,53 __], the integration of combinatorial lanthipeptide biosynthesis with in vitro selection or bacterial reverse two-hybrid screening methods have successfully obtained artificial ligands specific to certain target proteins. Such approaches, including other strategies under investigation in laboratories in this field, for constructing and screening vast RiPP libraries would lead to the creation of artificial bioactive peptides with non-proteinogenic structures in the near feature.”

(Goto & Suga, 2018)

“Our study is the first to assess and characterise silibinin’s various roles as an adjuvant in protecting against PZA- and INH-induced hepatotoxicity. Most promisingly, we demonstrated silibinin’s safety and efficacy as a rescue adjuvant in vitro , both of which are fundamental considerations in the use of any drug. We also identified silibinin’s potential utility as a rescue hepatoprotectant, shed important mechanistic insights on its hepatoprotective effect, and identified novel antioxidant targets in ameliorating ATT-induced hepatotoxicity. The proof-of-concept demonstrated in this project forms the ethical and scientific foundation to justify and inform subsequent in vivo preclinical studies and clinical trials. Given the lack of alternative treatments in tuberculosis, the need to preserve our remaining antibiotics is paramount. The high stakes involved necessitate future efforts to support our preliminary work in making silibinin clinically relevant to patients and healthcare professionals alike.”

(Goh, 2018)

1.7 In Summary

To recap, in drafting the Conclusion section, you should keep in mind that final remarks can leave the readers with a long-lasting impression of the report especially on the key point(s) that the writer intends to convey. Therefore, you should be careful in crafting this last section of your report.

1.8 References

Bahamani, A. et al. (2017). The Effect of Training Based on Precaution Adoption Process Model (PAPM) on Rural Females’ Participation in Pap smear. BJPR, 16 , 6. Retrieved from http://www.journalrepository.org/media/journals/BJPR_14/2017/May/Bahmani1662017BJPR32965.pdf

Craswell G., & Poore, M. (2012). Writing for Academic Success, 2nd. London: Sage.

Goh, Z-H. (2018). An Evaluation of the Roles and Mechanisms of Silibinin in Reducing Pyrazinamide- and Isoniazid-Induced Hepatotoxicity . Unpublished Final Year Project. National University of Singapore: Department of Pharmacy.

Goto, Y., & Suga, H. (2018). Engineering of RiPP pathways for the production of artificial peptides bearing various non-proteinogenic structures. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology , 46 , 82–90.

Lucas, B., & Blenkinsopp, A. (2015). Community pharmacists’ experience and perceptions of the New Medicines Serves (NMS). IJPP , 23 , 6. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijpp.12180/full

Markowski (2010). WPPD Evaluation form for capstone paper . Retrieved from https://cop-main.sites.medinfo.ufl.edu/files/2010/12/Capstone-Paper-Checklist-and-Reviewer-Evaluation-Form.pdf

Swales, J.M., & Feak, C.B. (2012). Academic writing for graduate students , 3 rd ed. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, The Writing Center. (2019). Conclusions . Retrieved from https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/conclusions/

Appendix 2: Quiz for Conclusion Activity

Instructions

There are 6 questions in this quiz. Choose the most appropriate answer among the options provided.

What does the Conclusion section of a scientific report do?

It provides a recap of report, with reference to the objective(s).

It gives a closure to what has been discussed in relation to the topic.

It shares future direction(s) and in doing so connects to a wider context.

It propels the reader to have an enhanced understanding of the topic.

i, ii, and iii

i, ii and iv

ii, iii and iv

i, ii, iii and iv

The first rhetorical move of the Conclusion section is restatement of objective(s). It …

reminds the reader the objective(s) of the report.

restates reason(s) of each objective of the report.

revisits issue(s) presented requiring investigation.

reiterates the importance of the research project.

The second rhetorical move of the Conclusion section is reflection of outcome(s). It …

summarizes all the findings of the research project.

synthesizes outcomes of the research project.

is a repeat of important ideas mentioned in the report.

shows how key points, evidence, and support fit together.

In connecting to a wider context, the authors …

remind the reader of the importance of the topic.

propose a course of action for the reader.

pose a question to the reader for further research.

direct the reader to certain direction(s).

Following is the Conclusion section of a published article.

“In summary, we have assessed and characterised silibinin’s various roles as an adjuvant in protecting against PZA- and INH-induced hepatotoxicity. Our in vitro experiments suggest that silibinin may be safe and efficacious as a rescue adjuvant, both fundamental considerations in the use of any drug. Further optimisation of our in vitro model may also enhance silibinin’s hepatoprotective effect in rescue, prophylaxis, and recovery. Using this model, we have gleaned important mechanistic insights into its hepatoprotective effect and identified novel antioxidant targets in ameliorating HRZE-induced hepatotoxicity. Future directions will involve exploring the two main mechanisms by which silibinin may ameliorate hepatotoxicity; the proof-of-concept demonstrated in this project will inform subsequent in vitro and in vivo preclinical studies. Given the lack of alternative treatments in tuberculosis, the need to preserve our remaining antibiotics is paramount. These high stakes necessitate future efforts to support our preliminary work, making silibinin more clinically relevant to patients and healthcare professionals alike.” (Goh et al., 2020)

This excerpt of the Conclusion section…

restates objectives of the research.

synthesizes outcomes of the research.

acknowledges limitations of the research

connects the reader to a wider context.

i, ii and iii

What can one observe about the use of tenses in the Conclusion section? The frequency of use of present and future tenses …

demonstrates the importance results being synthesized.

is ungrammatical as the past tense should be used to state the outcomes.

propels the reader to think of future research.

suggests an encouraging tone to end the report.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Wu, S.M., Lee, K.C., Chan, E.C.Y. (2023). The Conclusion: How to End a Scientific Report in Style. In: Rowland, S., Kuchel, L. (eds) Teaching Science Students to Communicate: A Practical Guide. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91628-2_54

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91628-2_54

Published : 26 April 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-91627-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-91628-2

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Conclusion for Research Papers (with Examples)

The conclusion of a research paper is a crucial section that plays a significant role in the overall impact and effectiveness of your research paper. However, this is also the section that typically receives less attention compared to the introduction and the body of the paper. The conclusion serves to provide a concise summary of the key findings, their significance, their implications, and a sense of closure to the study. Discussing how can the findings be applied in real-world scenarios or inform policy, practice, or decision-making is especially valuable to practitioners and policymakers. The research paper conclusion also provides researchers with clear insights and valuable information for their own work, which they can then build on and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

The research paper conclusion should explain the significance of your findings within the broader context of your field. It restates how your results contribute to the existing body of knowledge and whether they confirm or challenge existing theories or hypotheses. Also, by identifying unanswered questions or areas requiring further investigation, your awareness of the broader research landscape can be demonstrated.

Remember to tailor the research paper conclusion to the specific needs and interests of your intended audience, which may include researchers, practitioners, policymakers, or a combination of these.

Table of Contents

What is a conclusion in a research paper, summarizing conclusion, editorial conclusion, externalizing conclusion, importance of a good research paper conclusion, how to write a conclusion for your research paper, research paper conclusion examples.

- How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

A conclusion in a research paper is the final section where you summarize and wrap up your research, presenting the key findings and insights derived from your study. The research paper conclusion is not the place to introduce new information or data that was not discussed in the main body of the paper. When working on how to conclude a research paper, remember to stick to summarizing and interpreting existing content. The research paper conclusion serves the following purposes: 1

- Warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem.

- Recommend specific course(s) of action.

- Restate key ideas to drive home the ultimate point of your research paper.

- Provide a “take-home” message that you want the readers to remember about your study.

Types of conclusions for research papers

In research papers, the conclusion provides closure to the reader. The type of research paper conclusion you choose depends on the nature of your study, your goals, and your target audience. I provide you with three common types of conclusions:

A summarizing conclusion is the most common type of conclusion in research papers. It involves summarizing the main points, reiterating the research question, and restating the significance of the findings. This common type of research paper conclusion is used across different disciplines.

An editorial conclusion is less common but can be used in research papers that are focused on proposing or advocating for a particular viewpoint or policy. It involves presenting a strong editorial or opinion based on the research findings and offering recommendations or calls to action.

An externalizing conclusion is a type of conclusion that extends the research beyond the scope of the paper by suggesting potential future research directions or discussing the broader implications of the findings. This type of conclusion is often used in more theoretical or exploratory research papers.

Align your conclusion’s tone with the rest of your research paper. Start Writing with Paperpal Now!

The conclusion in a research paper serves several important purposes:

- Offers Implications and Recommendations : Your research paper conclusion is an excellent place to discuss the broader implications of your research and suggest potential areas for further study. It’s also an opportunity to offer practical recommendations based on your findings.

- Provides Closure : A good research paper conclusion provides a sense of closure to your paper. It should leave the reader with a feeling that they have reached the end of a well-structured and thought-provoking research project.

- Leaves a Lasting Impression : Writing a well-crafted research paper conclusion leaves a lasting impression on your readers. It’s your final opportunity to leave them with a new idea, a call to action, or a memorable quote.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper is essential to leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here’s a step-by-step process to help you create and know what to put in the conclusion of a research paper: 2

- Research Statement : Begin your research paper conclusion by restating your research statement. This reminds the reader of the main point you’ve been trying to prove throughout your paper. Keep it concise and clear.

- Key Points : Summarize the main arguments and key points you’ve made in your paper. Avoid introducing new information in the research paper conclusion. Instead, provide a concise overview of what you’ve discussed in the body of your paper.

- Address the Research Questions : If your research paper is based on specific research questions or hypotheses, briefly address whether you’ve answered them or achieved your research goals. Discuss the significance of your findings in this context.

- Significance : Highlight the importance of your research and its relevance in the broader context. Explain why your findings matter and how they contribute to the existing knowledge in your field.

- Implications : Explore the practical or theoretical implications of your research. How might your findings impact future research, policy, or real-world applications? Consider the “so what?” question.

- Future Research : Offer suggestions for future research in your area. What questions or aspects remain unanswered or warrant further investigation? This shows that your work opens the door for future exploration.

- Closing Thought : Conclude your research paper conclusion with a thought-provoking or memorable statement. This can leave a lasting impression on your readers and wrap up your paper effectively. Avoid introducing new information or arguments here.

- Proofread and Revise : Carefully proofread your conclusion for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Ensure that your ideas flow smoothly and that your conclusion is coherent and well-structured.

Write your research paper conclusion 2x faster with Paperpal. Try it now!

Remember that a well-crafted research paper conclusion is a reflection of the strength of your research and your ability to communicate its significance effectively. It should leave a lasting impression on your readers and tie together all the threads of your paper. Now you know how to start the conclusion of a research paper and what elements to include to make it impactful, let’s look at a research paper conclusion sample.

How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

A research paper conclusion is not just a summary of your study, but a synthesis of the key findings that ties the research together and places it in a broader context. A research paper conclusion should be concise, typically around one paragraph in length. However, some complex topics may require a longer conclusion to ensure the reader is left with a clear understanding of the study’s significance. Paperpal, an AI writing assistant trusted by over 800,000 academics globally, can help you write a well-structured conclusion for your research paper.

- Sign Up or Log In: Create a new Paperpal account or login with your details.

- Navigate to Features : Once logged in, head over to the features’ side navigation pane. Click on Templates and you’ll find a suite of generative AI features to help you write better, faster.

- Generate an outline: Under Templates, select ‘Outlines’. Choose ‘Research article’ as your document type.

- Select your section: Since you’re focusing on the conclusion, select this section when prompted.

- Choose your field of study: Identifying your field of study allows Paperpal to provide more targeted suggestions, ensuring the relevance of your conclusion to your specific area of research.

- Provide a brief description of your study: Enter details about your research topic and findings. This information helps Paperpal generate a tailored outline that aligns with your paper’s content.

- Generate the conclusion outline: After entering all necessary details, click on ‘generate’. Paperpal will then create a structured outline for your conclusion, to help you start writing and build upon the outline.

- Write your conclusion: Use the generated outline to build your conclusion. The outline serves as a guide, ensuring you cover all critical aspects of a strong conclusion, from summarizing key findings to highlighting the research’s implications.

- Refine and enhance: Paperpal’s ‘Make Academic’ feature can be particularly useful in the final stages. Select any paragraph of your conclusion and use this feature to elevate the academic tone, ensuring your writing is aligned to the academic journal standards.

By following these steps, Paperpal not only simplifies the process of writing a research paper conclusion but also ensures it is impactful, concise, and aligned with academic standards. Sign up with Paperpal today and write your research paper conclusion 2x faster .

The research paper conclusion is a crucial part of your paper as it provides the final opportunity to leave a strong impression on your readers. In the research paper conclusion, summarize the main points of your research paper by restating your research statement, highlighting the most important findings, addressing the research questions or objectives, explaining the broader context of the study, discussing the significance of your findings, providing recommendations if applicable, and emphasizing the takeaway message. The main purpose of the conclusion is to remind the reader of the main point or argument of your paper and to provide a clear and concise summary of the key findings and their implications. All these elements should feature on your list of what to put in the conclusion of a research paper to create a strong final statement for your work.

A strong conclusion is a critical component of a research paper, as it provides an opportunity to wrap up your arguments, reiterate your main points, and leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here are the key elements of a strong research paper conclusion: 1. Conciseness : A research paper conclusion should be concise and to the point. It should not introduce new information or ideas that were not discussed in the body of the paper. 2. Summarization : The research paper conclusion should be comprehensive enough to give the reader a clear understanding of the research’s main contributions. 3 . Relevance : Ensure that the information included in the research paper conclusion is directly relevant to the research paper’s main topic and objectives; avoid unnecessary details. 4 . Connection to the Introduction : A well-structured research paper conclusion often revisits the key points made in the introduction and shows how the research has addressed the initial questions or objectives. 5. Emphasis : Highlight the significance and implications of your research. Why is your study important? What are the broader implications or applications of your findings? 6 . Call to Action : Include a call to action or a recommendation for future research or action based on your findings.

The length of a research paper conclusion can vary depending on several factors, including the overall length of the paper, the complexity of the research, and the specific journal requirements. While there is no strict rule for the length of a conclusion, but it’s generally advisable to keep it relatively short. A typical research paper conclusion might be around 5-10% of the paper’s total length. For example, if your paper is 10 pages long, the conclusion might be roughly half a page to one page in length.

In general, you do not need to include citations in the research paper conclusion. Citations are typically reserved for the body of the paper to support your arguments and provide evidence for your claims. However, there may be some exceptions to this rule: 1. If you are drawing a direct quote or paraphrasing a specific source in your research paper conclusion, you should include a citation to give proper credit to the original author. 2. If your conclusion refers to or discusses specific research, data, or sources that are crucial to the overall argument, citations can be included to reinforce your conclusion’s validity.

The conclusion of a research paper serves several important purposes: 1. Summarize the Key Points 2. Reinforce the Main Argument 3. Provide Closure 4. Offer Insights or Implications 5. Engage the Reader. 6. Reflect on Limitations

Remember that the primary purpose of the research paper conclusion is to leave a lasting impression on the reader, reinforcing the key points and providing closure to your research. It’s often the last part of the paper that the reader will see, so it should be strong and well-crafted.

- Makar, G., Foltz, C., Lendner, M., & Vaccaro, A. R. (2018). How to write effective discussion and conclusion sections. Clinical spine surgery, 31(8), 345-346.

- Bunton, D. (2005). The structure of PhD conclusion chapters. Journal of English for academic purposes , 4 (3), 207-224.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

7 Ways to Improve Your Academic Writing Process

- Paraphrasing in Academic Writing: Answering Top Author Queries

Preflight For Editorial Desk: The Perfect Hybrid (AI + Human) Assistance Against Compromised Manuscripts

You may also like, how to write a high-quality conference paper, academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, phd qualifying exam: tips for success , ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , should you use ai tools like chatgpt for....

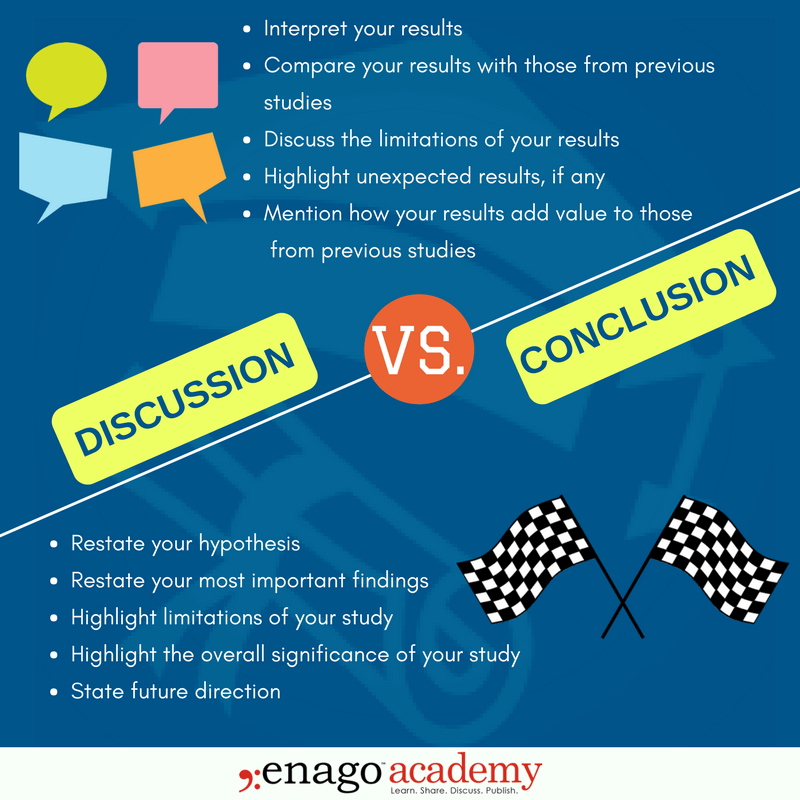

Discussion Vs. Conclusion: Know the Difference Before Drafting Manuscripts

The discussion section of your manuscript can be one of the hardest to write as it requires you to think about the meaning of the research you have done. An effective discussion section tells the reader what your study means and why it is important. In this article, we will cover some pointers for writing clear/well-organized discussion and conclusion sections and discuss what should NOT be a part of these sections.

What Should be in the Discussion Section?

Your discussion is, in short, the answer to the question “what do my results mean?” The discussion section of the manuscript should come after the methods and results section and before the conclusion. It should relate back directly to the questions posed in your introduction, and contextualize your results within the literature you have covered in your literature review . In order to make your discussion section engaging, you should include the following information:

- The major findings of your study

- The meaning of those findings

- How these findings relate to what others have done

- Limitations of your findings

- An explanation for any surprising, unexpected, or inconclusive results

- Suggestions for further research

Your discussion should NOT include any of the following information:

- New results or data not presented previously in the paper

- Unwarranted speculation

- Tangential issues

- Conclusions not supported by your data

Related: Avoid outright rejection with a well-structured manuscript. Check out these resources and improve your manuscript now!

How to Make the Discussion Section Effective?

There are several ways to make the discussion section of your manuscript effective, interesting, and relevant. Hear from one of our experts on how to structure your discussion section and distinguish it from the results section:

Now that we have listened to how to approach writing a discussion section, let’s delve deeper into some essential tips with a few examples:

- Most writing guides recommend listing the findings of your study in decreasing order of their importance. You would not want your reader to lose sight of the key results that you found. Therefore, put the most important finding front and center. Example: Imagine that you conduct a study aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of stent placement in patients with partially blocked arteries. You find that despite this being a common first-line treatment, stents are not effective for patients with partially blocked arteries. The study also discovers that patients treated with a stent tend to develop asthma at slightly higher rates than those who receive no such treatment.

Which sentence would you choose to begin your discussion? Our findings suggest that patients who had partially blocked arteries and were treated with a stent as the first line of intervention had no better outcomes than patients who were not given any surgical treatments. Our findings noted that patients who received stents demonstrated slightly higher rates of asthma than those who did not. In addition, the placement of a stent did not impact their rates of cardiac events in a statistically significant way.

If you chose the first example, you are correct!

- If you are not sure which results are the most important, go back to your research question and start from there. The most important result is the one that answers your research question.

- It is also necessary to contextualize the meaning of your findings for the reader. What does previous literature say, and do your results agree? Do your results elaborate on previous findings, or differ significantly?

- In our stent example, if previous literature found that stents were an effective line of treatment for patients with partially blocked arteries, you should explore why your interpretation seems different in the discussion section. Did your methodology differ? Was your study broader in scope and larger in scale than the previous studies? Were there any limitations to previous studies that your study overcame? Alternatively, is it possible that your own study could be incorrect because of some difficulties you had in carrying it out? The discussion section should narrate a coherent story to the target audience.

- Finally, remember not to introduce new ideas/data, or speculate wildly on the possible future implications of your study in the discussion section. However, considering alternative explanations for your results is encouraged.

Avoiding Confusion in your Conclusion!

Many writers confuse the information they should include in their discussion with the information they should place in their conclusion. One easy way to avoid this confusion is to think of your conclusion as a summary of everything that you have said thus far. In the conclusion section, you remind the reader of what they have just read. Your conclusion should:

- Restate your hypothesis or research question

- Restate your major findings

- Tell the reader what contribution your study has made to the existing literature

- Highlight any limitations of your study

- State future directions for research/recommendations

Your conclusion should NOT:

- Introduce new arguments

- Introduce new data

- Fail to include your research question

- Fail to state your major results

An appropriate conclusion to our hypothetical stent study might read as follows:

In this study, we examined the effectiveness of stent placement. We compared the patients with partially blocked arteries to those with non-surgical interventions. After examining the five-year medical outcomes of 19,457 patients in the Greater Dallas area, our statistical analysis concluded that the placement of a stent resulted in outcomes that were no better than non-surgical interventions such as diet and exercise. Although previous findings indicated that stent placement improved patient outcomes, our study followed a greater number of patients than those in major studies conducted previously. It is possible that outcomes would vary if measured over a ten or fifteen year period. Future researchers should consider investigating the impact of stent placement in these patients over a longer period (five years or longer). Regardless, our results point to the need for medical practitioners to reconsider the placement of a stent as the first line of treatment as non-surgical interventions may have equally positive outcomes for patients.

Did you find the tips in this article relevant? What is the most challenging portion of a research paper for you to write? Let us know in the comments section below!

This is the most stunning and self-instructional site I have come across. Thank you so much for your updates! I will help me work on my dissertation.

Thank you so much!! It helps a lot!

very helpful, thank you

thanks a lot …

this is one of a kind! awesome, straight to the point and easy to understand! Thanks a lot

Thank you so much for this, I never comment on these types of sites but I just had too here as I’ve never seen an article that has answered everyone of the questions I wanted when I searched on Google. Certainly not to the extent and clear clarity that you have presented. Thanks so much for this it has put my mind to ease a bit with my terrible dissertation haha.

Have a nice day.

Helped massively with writing a good conclusion!

Extremely well explained all details in simple and applicable manner, Thank you very much for outstanding article. It really made life easy. Ravi, India.

Thanks a lot for such a nicely explained difference of discussion and conclusion. now got some basic idea to write what.

Thanks for clearing the great confusion. It gave real clarity to me!

Clarified my confusion. Thank you for this article

This website certainly has all of the information I wanted concerning this subject and didn’t know who to ask.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Infographic

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

- Trending Now

Can AI Tools Prepare a Research Manuscript From Scratch? — A comprehensive guide

As technology continues to advance, the question of whether artificial intelligence (AI) tools can prepare…

Abstract Vs. Introduction — Do you know the difference?

Ross wants to publish his research. Feeling positive about his research outcomes, he begins to…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Demystifying Research Methodology With Field Experts

Choosing research methodology Research design and methodology Evidence-based research approach How RAxter can assist researchers

- Manuscript Preparation

- Publishing Research

How to Choose Best Research Methodology for Your Study

Successful research conduction requires proper planning and execution. While there are multiple reasons and aspects…

Top 5 Key Differences Between Methods and Methodology

While burning the midnight oil during literature review, most researchers do not realize that the…

How to Draft the Acknowledgment Section of a Manuscript

Annex Vs. Appendix: Do You Know the Difference?

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

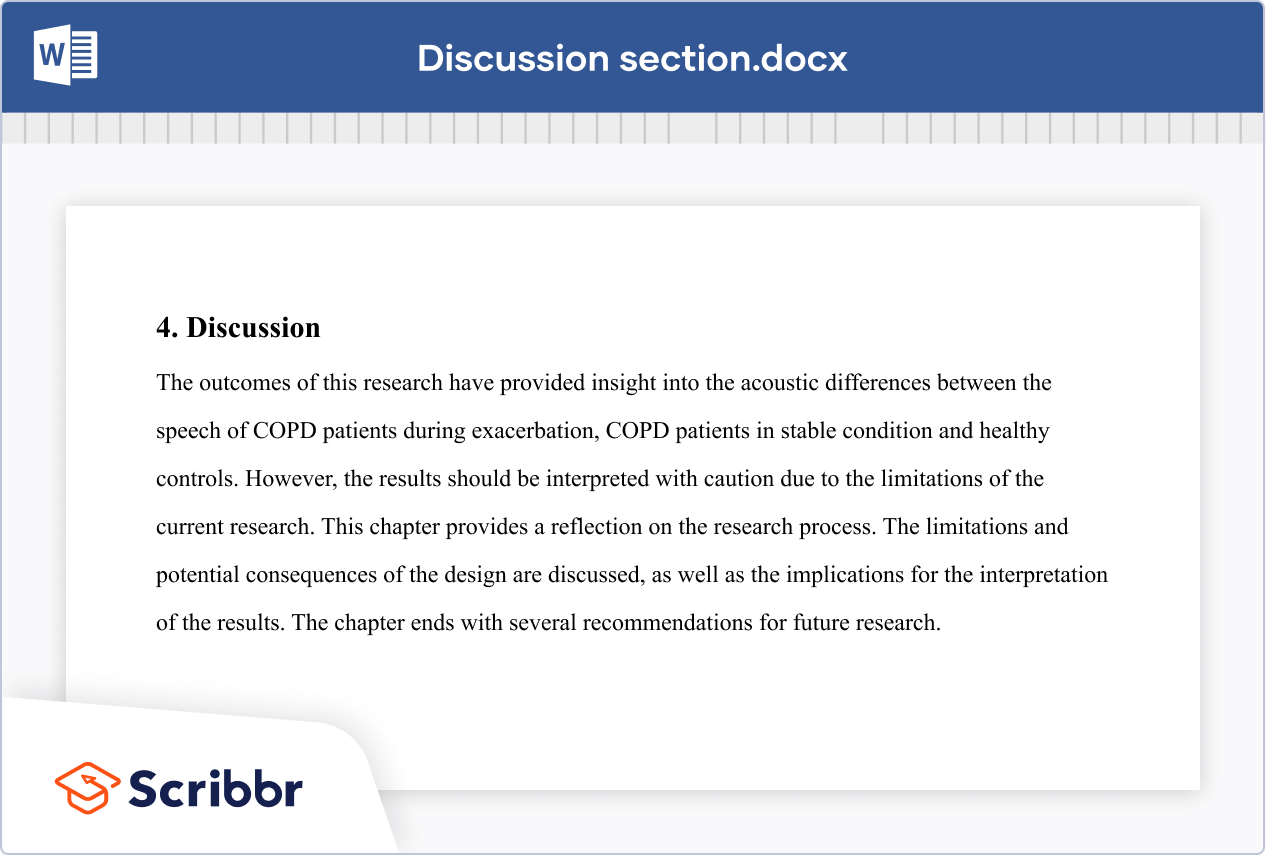

How to Write the Discussion Section of a Research Paper

The discussion section of a research paper analyzes and interprets the findings, provides context, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future research directions.

Updated on September 15, 2023

Structure your discussion section right, and you’ll be cited more often while doing a greater service to the scientific community. So, what actually goes into the discussion section? And how do you write it?

The discussion section of your research paper is where you let the reader know how your study is positioned in the literature, what to take away from your paper, and how your work helps them. It can also include your conclusions and suggestions for future studies.

First, we’ll define all the parts of your discussion paper, and then look into how to write a strong, effective discussion section for your paper or manuscript.

Discussion section: what is it, what it does

The discussion section comes later in your paper, following the introduction, methods, and results. The discussion sets up your study’s conclusions. Its main goals are to present, interpret, and provide a context for your results.

What is it?

The discussion section provides an analysis and interpretation of the findings, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future directions for research.

This section combines information from the preceding parts of your paper into a coherent story. By this point, the reader already knows why you did your study (introduction), how you did it (methods), and what happened (results). In the discussion, you’ll help the reader connect the ideas from these sections.

Why is it necessary?

The discussion provides context and interpretations for the results. It also answers the questions posed in the introduction. While the results section describes your findings, the discussion explains what they say. This is also where you can describe the impact or implications of your research.

Adds context for your results

Most research studies aim to answer a question, replicate a finding, or address limitations in the literature. These goals are first described in the introduction. However, in the discussion section, the author can refer back to them to explain how the study's objective was achieved.

Shows what your results actually mean and real-world implications

The discussion can also describe the effect of your findings on research or practice. How are your results significant for readers, other researchers, or policymakers?

What to include in your discussion (in the correct order)

A complete and effective discussion section should at least touch on the points described below.

Summary of key findings

The discussion should begin with a brief factual summary of the results. Concisely overview the main results you obtained.

Begin with key findings with supporting evidence

Your results section described a list of findings, but what message do they send when you look at them all together?

Your findings were detailed in the results section, so there’s no need to repeat them here, but do provide at least a few highlights. This will help refresh the reader’s memory and help them focus on the big picture.

Read the first paragraph of the discussion section in this article (PDF) for an example of how to start this part of your paper. Notice how the authors break down their results and follow each description sentence with an explanation of why each finding is relevant.

State clearly and concisely

Following a clear and direct writing style is especially important in the discussion section. After all, this is where you will make some of the most impactful points in your paper. While the results section often contains technical vocabulary, such as statistical terms, the discussion section lets you describe your findings more clearly.

Interpretation of results

Once you’ve given your reader an overview of your results, you need to interpret those results. In other words, what do your results mean? Discuss the findings’ implications and significance in relation to your research question or hypothesis.

Analyze and interpret your findings

Look into your findings and explore what’s behind them or what may have caused them. If your introduction cited theories or studies that could explain your findings, use these sources as a basis to discuss your results.

For example, look at the second paragraph in the discussion section of this article on waggling honey bees. Here, the authors explore their results based on information from the literature.

Unexpected or contradictory results

Sometimes, your findings are not what you expect. Here’s where you describe this and try to find a reason for it. Could it be because of the method you used? Does it have something to do with the variables analyzed? Comparing your methods with those of other similar studies can help with this task.

Context and comparison with previous work

Refer to related studies to place your research in a larger context and the literature. Compare and contrast your findings with existing literature, highlighting similarities, differences, and/or contradictions.

How your work compares or contrasts with previous work

Studies with similar findings to yours can be cited to show the strength of your findings. Information from these studies can also be used to help explain your results. Differences between your findings and others in the literature can also be discussed here.

How to divide this section into subsections

If you have more than one objective in your study or many key findings, you can dedicate a separate section to each of these. Here’s an example of this approach. You can see that the discussion section is divided into topics and even has a separate heading for each of them.

Limitations

Many journals require you to include the limitations of your study in the discussion. Even if they don’t, there are good reasons to mention these in your paper.

Why limitations don’t have a negative connotation

A study’s limitations are points to be improved upon in future research. While some of these may be flaws in your method, many may be due to factors you couldn’t predict.

Examples include time constraints or small sample sizes. Pointing this out will help future researchers avoid or address these issues. This part of the discussion can also include any attempts you have made to reduce the impact of these limitations, as in this study .

How limitations add to a researcher's credibility

Pointing out the limitations of your study demonstrates transparency. It also shows that you know your methods well and can conduct a critical assessment of them.

Implications and significance

The final paragraph of the discussion section should contain the take-home messages for your study. It can also cite the “strong points” of your study, to contrast with the limitations section.

Restate your hypothesis

Remind the reader what your hypothesis was before you conducted the study.

How was it proven or disproven?

Identify your main findings and describe how they relate to your hypothesis.

How your results contribute to the literature

Were you able to answer your research question? Or address a gap in the literature?

Future implications of your research

Describe the impact that your results may have on the topic of study. Your results may show, for instance, that there are still limitations in the literature for future studies to address. There may be a need for studies that extend your findings in a specific way. You also may need additional research to corroborate your findings.

Sample discussion section

This fictitious example covers all the aspects discussed above. Your actual discussion section will probably be much longer, but you can read this to get an idea of everything your discussion should cover.

Our results showed that the presence of cats in a household is associated with higher levels of perceived happiness by its human occupants. These findings support our hypothesis and demonstrate the association between pet ownership and well-being.

The present findings align with those of Bao and Schreer (2016) and Hardie et al. (2023), who observed greater life satisfaction in pet owners relative to non-owners. Although the present study did not directly evaluate life satisfaction, this factor may explain the association between happiness and cat ownership observed in our sample.

Our findings must be interpreted in light of some limitations, such as the focus on cat ownership only rather than pets as a whole. This may limit the generalizability of our results.

Nevertheless, this study had several strengths. These include its strict exclusion criteria and use of a standardized assessment instrument to investigate the relationships between pets and owners. These attributes bolster the accuracy of our results and reduce the influence of confounding factors, increasing the strength of our conclusions. Future studies may examine the factors that mediate the association between pet ownership and happiness to better comprehend this phenomenon.