How to Cite in APA Style (7th Edition)

- About APA 7th ed.

- In-text Citations

Basic Rules

Dois and urls.

- Webpages, Reports

- Media Works

- Conference, Theses, Data Sets, etc.

- Sample Reference List

- Cite Tables & Figures

- Help You Cite Tools

- Test Your Knowledge

- Online Tutorials & Videos

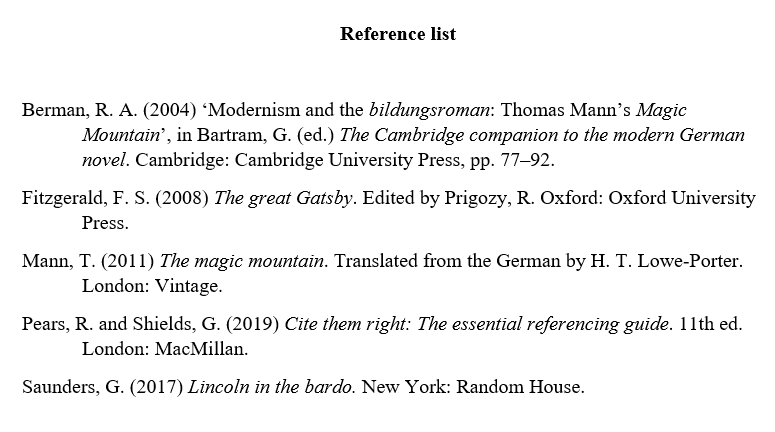

Reference List format

Start of References Page (Section 2.12)

- Start the reference list on a new page after the text and before any tables, figures, and/or appendices.

- The word References should appear in uppercase and lowercase letters, in bold, and centered; do not underline, or put the word "References" in quotation marks.

- See the Sample Reference List on this library guide.

Spacing (Section 2.12)

- Double-space all reference entries (including between and within references), and put them in a hanging indent format, i.e. all lines after the first line of each reference entry should be indented 0.5 inch from the left margin.

References go A-Z by author's surname (Section 9.44)

- Arrange reference entries in alphabetical order by the surname of the first author followed by initials of the author's given name.

4 Key elements of reference entries

Author. date. title. source..

Who | When | What | Where

Nettle, D. (2005). Happiness: The science behind your smile. Oxford University Press.

Diliello, T. C., Houghton, J. D., & Dawley, D. (2011). Narrowing the creativity gap: The moderating effects of perceived support for creativity. Journal of Psychology, 145 (3), 151-172. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2010.548412

See this APA Style page for more details: Elements of Reference List Entries.

Missing information (No author, no date, etc.)

- Check out this APA Style page: Missing Reference Information .

- 1, 2-20 or 21+ authors

- One author with multiple publications

- Different authors with same surname

- 1 author: Invert the authors' name if needed, give surnames first , followed by a comma, and then add the initials.

William SHAKESPEARE → Shakespeare, W.

CHAN Tai Man → Chan, T. M.

- 2 to 20 authors : Use a comma to separate the author's initials from the next author's name. Add an ampersand ( & ) before the final author.

Chan, T. M ., Cheung, B. B ., & Fung, C. C.

- 21 or more authors : Include the first 19 authors' names, then insert an ellipses (but no ampersand), and add the last author's name.

Chan, T. M., Cheung, B. B., Chung, C. C., Ding, D. D., Fung, E. E., Fung, F. F., Fung, G.G., Fung, H. H., Fung, I. I., Hung, J.J., Hung, K. K., Hung, L. L., Hung, M. M., Ip, N. N., Ip, O. O., Ip, P. P., Ip, Q. Q., Ip. R. R., Jiang, S. S., . . . Zhang, Y. Y.

More details: How many names to include in an APA Style reference , Section 9.8

- For several works by the same author or authors in the same order, arrange the reference entries by year of publication, the earliest first.

Chan, T. M. ( 2015 ).

Chan, T. M. ( 2017a ).

Chan, T. M. ( 2017b ).

More details: Section 9.46

- For several works by different first authors with the same surname, arrange the reference entries by different authors with the same surname and different initials alphabetically by first initial(s).

Chan, K. L. (2015).

Chan, T. K. (2013).

More details: Section 9.48

Publication Date

- Enclose the date of publication in parentheses, followed by a period.

Chan, T. M. (2022).

- For a work that includes the month, day, and/or season along with the year, put the year first, followed by a comma, and then the month and date or season.

Chan, T. M. (2022, January 1).

Chan, T. M. (2022, Spring).

- If no date is available, write n.d. in parentheses (Section 9.17) .

Chan, T. M. (n.d.).

More details: Section 9.14

Retrieval Date

Provide a retrieval date in the reference when citing an unstable work that is likely or meant to change over time (dictionary entry, Facebook page, etc.). Use this format to include a retrieval date: Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://xxxxx

More details: Section 9.16 , Elements of Reference List Entries - Retrieval dates

DOI (digital object identifier) is a unique identifier to help you locate a scholarly work (such as journal article, book chapter) online.

A sample DOI link: https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2010.548412

- Include a DOI in the reference entry when it is available, regardless of whether you used the online version or the print version.

- For works without DOIs, include the URLs instead, if available. More details: DOIs and URLs

- For works from academic research databases, do not include database information in the reference. Instead, the reference should be the same as the reference for a print version of the work. More details: Database Information in Reference

- When a DOI or URL is too long, you may use shortened DOI or URL if desired.

More details: Sections 9.34 - 9.36

- << Previous: In-text Citations

- Next: Books >>

- Last Updated: Jan 2, 2024 9:23 AM

- URL: https://libguides.hkust.edu.hk/apa

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

APA Formatting and Style Guide (7th Edition)

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

In-Text Citations

Resources on using in-text citations in APA style

Reference List

Resources on writing an APA style reference list, including citation formats

Other APA Resources

popular searches

- Request Info

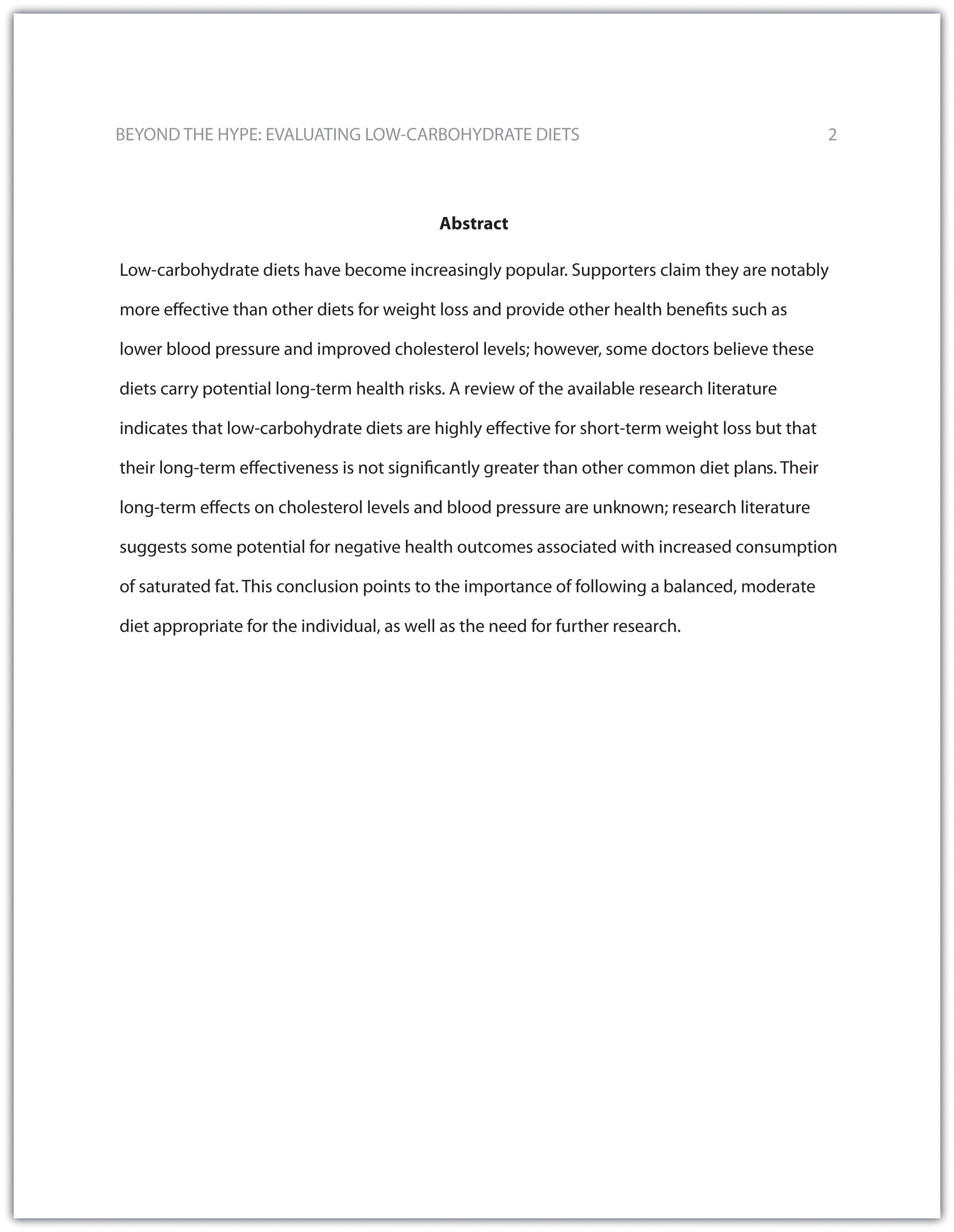

APA Format for End References

APA format is the official style used by the American Psychological Association .

APA style is used primarily in the social sciences and communicates data in a concise style that precisely describes material, makes the relationship between ideas or data as clear as possible, is generally in the active voice, and utilizes the past tense. In addition to being scientific and precise, you must use bias-free and inclusive language when writing in APA style. Your role is to be objective, to be conscious of word choice, and to avoid discriminatory language.

The font should remain the same throughout the paper. Options include 11-point sans-serif fonts, such as Calibri or Arial, and 12-point serif fonts, such as Times New Roman. Ultimately, check with your instructors about their font preferences. All text, including block quotes and the references section, should be double spaced.

Title pages include the paper title (in bold) followed by an extra space, the author (your name), affiliation (department and college), course number and name, instructor, and due date.

Crediting Sources

In-text citations.

In-text citations are included in the body of the paper. They identify the source by the author and its date of publication. Citations always correspond with an entry in the references section at the end of the paper. The two types of in-text citations, narrative and parenthetical, are shown below in the paraphrase and direct quotation examples.

Paraphrasing means summarizing relevant information from a source. This method of borrowing is more commonly used in APA papers than quotations because it allows a writer to maintain their objective voice and combine the source’s ideas with their own. Paraphrases are always cited both in the text of the paper and in the reference page.

Paraphrase example using the narrative citation method

Rogers (1994) compared younger and older adults’ perceptions of economic stress.

Paraphrase example using the parenthetical citation method

The citation information is included at the end of the paraphrase in parenthesis.

In some instances, the hierarchical level at which employees worked significantly impacted their behavior in work groups (Mellers, Ortiz, & Smoot, 2006).

Direct quotations

Direct quotations are limited in APA style papers. Instead, you should paraphrase whenever possible to blend borrowed information with your context and voice. The APA Publication Manual, 7 th Edition notes that a writer should use direct quotations “when reproducing an exact definition, when an author has said something memorably or succinctly, or when you want to respond to exact wording.” The author, years, and page number (or section identifier) is always paired with quoted material through the narrative or parenthetical citation format.

Short quotation example

This example uses the parenthetical in-text citation format.

In several double-blind experiments, "'the placebo effect' . . . disappeared when behaviors were studied in this manner" (Miele, 1993, p. 276).

Reference(s)

McCauley, S. M., & Christiansen, M. H. (2019). Language learning as language use: A cross-linguistic model of child language development. Psychological Review, 126 (1), 1-51. http://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000126

Parenthetical citation: (McCauley & Christiansen, 2019)

Narrative citation: McCauley and Christiansen (2019)

Other Writing Resources

Enhance your academic writing skills by exploring our additional writing resources that will help you craft compelling essays, research papers, and more.

Your New Chapter Starts Wherever You Are

The support you need and education you deserve, no matter where life leads.

because a future built by you is a future built for you.

Too many people have been made to feel that higher education isn’t a place for them— that it is someone else’s dream. But we change all that. With individualized attention and ongoing support, we help you write a new story for the future where you play the starring role.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Referencing

A Quick Guide to Referencing | Cite Your Sources Correctly

Referencing means acknowledging the sources you have used in your writing. Including references helps you support your claims and ensures that you avoid plagiarism .

There are many referencing styles, but they usually consist of two things:

- A citation wherever you refer to a source in your text.

- A reference list or bibliography at the end listing full details of all your sources.

The most common method of referencing in UK universities is Harvard style , which uses author-date citations in the text. Our free Harvard Reference Generator automatically creates accurate references in this style.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Referencing styles, citing your sources with in-text citations, creating your reference list or bibliography, harvard referencing examples, frequently asked questions about referencing.

Each referencing style has different rules for presenting source information. For in-text citations, some use footnotes or endnotes , while others include the author’s surname and date of publication in brackets in the text.

The reference list or bibliography is presented differently in each style, with different rules for things like capitalisation, italics, and quotation marks in references.

Your university will usually tell you which referencing style to use; they may even have their own unique style. Always follow your university’s guidelines, and ask your tutor if you are unsure. The most common styles are summarised below.

Harvard referencing, the most commonly used style at UK universities, uses author–date in-text citations corresponding to an alphabetical bibliography or reference list at the end.

Harvard Referencing Guide

Vancouver referencing, used in biomedicine and other sciences, uses reference numbers in the text corresponding to a numbered reference list at the end.

Vancouver Referencing Guide

APA referencing, used in the social and behavioural sciences, uses author–date in-text citations corresponding to an alphabetical reference list at the end.

APA Referencing Guide APA Reference Generator

MHRA referencing, used in the humanities, uses footnotes in the text with source information, in addition to an alphabetised bibliography at the end.

MHRA Referencing Guide

OSCOLA referencing, used in law, uses footnotes in the text with source information, and an alphabetical bibliography at the end in longer texts.

OSCOLA Referencing Guide

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

In-text citations should be used whenever you quote, paraphrase, or refer to information from a source (e.g. a book, article, image, website, or video).

Quoting and paraphrasing

Quoting is when you directly copy some text from a source and enclose it in quotation marks to indicate that it is not your own writing.

Paraphrasing is when you rephrase the original source into your own words. In this case, you don’t use quotation marks, but you still need to include a citation.

In most referencing styles, page numbers are included when you’re quoting or paraphrasing a particular passage. If you are referring to the text as a whole, no page number is needed.

In-text citations

In-text citations are quick references to your sources. In Harvard referencing, you use the author’s surname and the date of publication in brackets.

Up to three authors are included in a Harvard in-text citation. If the source has more than three authors, include the first author followed by ‘ et al. ‘

The point of these citations is to direct your reader to the alphabetised reference list, where you give full information about each source. For example, to find the source cited above, the reader would look under ‘J’ in your reference list to find the title and publication details of the source.

Placement of in-text citations

In-text citations should be placed directly after the quotation or information they refer to, usually before a comma or full stop. If a sentence is supported by multiple sources, you can combine them in one set of brackets, separated by a semicolon.

If you mention the author’s name in the text already, you don’t include it in the citation, and you can place the citation immediately after the name.

- Another researcher warns that the results of this method are ‘inconsistent’ (Singh, 2018, p. 13) .

- Previous research has frequently illustrated the pitfalls of this method (Singh, 2018; Jones, 2016) .

- Singh (2018, p. 13) warns that the results of this method are ‘inconsistent’.

The terms ‘bibliography’ and ‘reference list’ are sometimes used interchangeably. Both refer to a list that contains full information on all the sources cited in your text. Sometimes ‘bibliography’ is used to mean a more extensive list, also containing sources that you consulted but did not cite in the text.

A reference list or bibliography is usually mandatory, since in-text citations typically don’t provide full source information. For styles that already include full source information in footnotes (e.g. OSCOLA and Chicago Style ), the bibliography is optional, although your university may still require you to include one.

Format of the reference list

Reference lists are usually alphabetised by authors’ last names. Each entry in the list appears on a new line, and a hanging indent is applied if an entry extends onto multiple lines.

Different source information is included for different source types. Each style provides detailed guidelines for exactly what information should be included and how it should be presented.

Below are some examples of reference list entries for common source types in Harvard style.

- Chapter of a book

- Journal article

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Your university should tell you which referencing style to follow. If you’re unsure, check with a supervisor. Commonly used styles include:

- Harvard referencing , the most commonly used style in UK universities.

- MHRA , used in humanities subjects.

- APA , used in the social sciences.

- Vancouver , used in biomedicine.

- OSCOLA , used in law.

Your university may have its own referencing style guide.

If you are allowed to choose which style to follow, we recommend Harvard referencing, as it is a straightforward and widely used style.

References should be included in your text whenever you use words, ideas, or information from a source. A source can be anything from a book or journal article to a website or YouTube video.

If you don’t acknowledge your sources, you can get in trouble for plagiarism .

To avoid plagiarism , always include a reference when you use words, ideas or information from a source. This shows that you are not trying to pass the work of others off as your own.

You must also properly quote or paraphrase the source. If you’re not sure whether you’ve done this correctly, you can use the Scribbr Plagiarism Checker to find and correct any mistakes.

Harvard referencing uses an author–date system. Sources are cited by the author’s last name and the publication year in brackets. Each Harvard in-text citation corresponds to an entry in the alphabetised reference list at the end of the paper.

Vancouver referencing uses a numerical system. Sources are cited by a number in parentheses or superscript. Each number corresponds to a full reference at the end of the paper.

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples

- APA Referencing (7th Ed.) Quick Guide | In-text Citations & References

How to Avoid Plagiarism | Tips on Citing Sources

More interesting articles.

- A Quick Guide to OSCOLA Referencing | Rules & Examples

- Harvard In-Text Citation | A Complete Guide & Examples

- Harvard Referencing for Journal Articles | Templates & Examples

- Harvard Style Bibliography | Format & Examples

- MHRA Referencing | A Quick Guide & Citation Examples

- Reference a Website in Harvard Style | Templates & Examples

- Referencing Books in Harvard Style | Templates & Examples

- Vancouver Referencing | A Quick Guide & Reference Examples

Scribbr APA Citation Checker

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Research Tips and Tools

Bruin Success with Less Stress

- How to Cite: In the Text and at the End

- What Does This Mean to You?

- You and Copyright

- Copyright: You as Creator

- Copyright: You as Consumer

- Patents and You

- Bruin Bragging Rights

- What Did Carlos and Eddie Learn?

- Explore More

- Send Us Feedback

- Students Getting Sued?

- Student Comments on the News

- Copyright Law and File Sharing

- Urban Myths of Copyright Violations

- File Sharing at UCLA

- Where Does UCLA Stand?

- Fact or Fiction?

- What to Cite

- How to Cite: Choosing a Style

- Works Cited and Reference Lists: The Basics

- Cite as You Write: In-Text Basic Citations

- Quoting, Summarizing and Paraphrasing in a Nutshell

- Tips on Quoting

- Tips on Summarizing

- Tips on Paraphrasing

- Oops: I Thought Your Words Were Mine: Taking Notes

- Working with Friends

- What Did Eddie Learn?

- Quiz Yourself!

- Print Citation Guides

- Tips for Making Research a Little Less Painful

- What Are You Looking At?

- E-mail Citations to Yourself

- Taking Notes

- Keep Track of Searches

- Keep Things in One Place

- Why Print Web Pages?

- Time and Project Management

- Planning and Timing

- Keeping Things on Track

- Resources on Campus

- What Was That Again?

- Tips From Students

- Where Do You Stand?

- Academic Integrity and UCLA Policies

- Things You Don't Want to Do

- Consequences

- Decisions, Decisions...

- Things to Do and Things to Avoid

How to Cite: During and After

Two techniques of citing and documenting sources that are usually required in academic writing are:

- Providing a list of citations at the end of the paper

- Citing within the text of the paper

These two techniques are used together.

Cite At the End

Cite as you write.

Need more? See Resources for UCLA Students.

Plagiarism Isn't Just About Words

Did you know that according to the UCLA Dean of Students, using someone else's data in a computer exercise without authorization is considered plagiarism? It's true. Using someone's statistical data, computer code, or any other type of intellectual property without attributing the source is considered plagiarism. See the Office of the Dean of Students web site for more.

("UCLA Student Conduct Code")

- << Previous: How to Cite: Choosing a Style

- Next: Works Cited and Reference Lists: The Basics >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 11:13 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/bruin-success

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

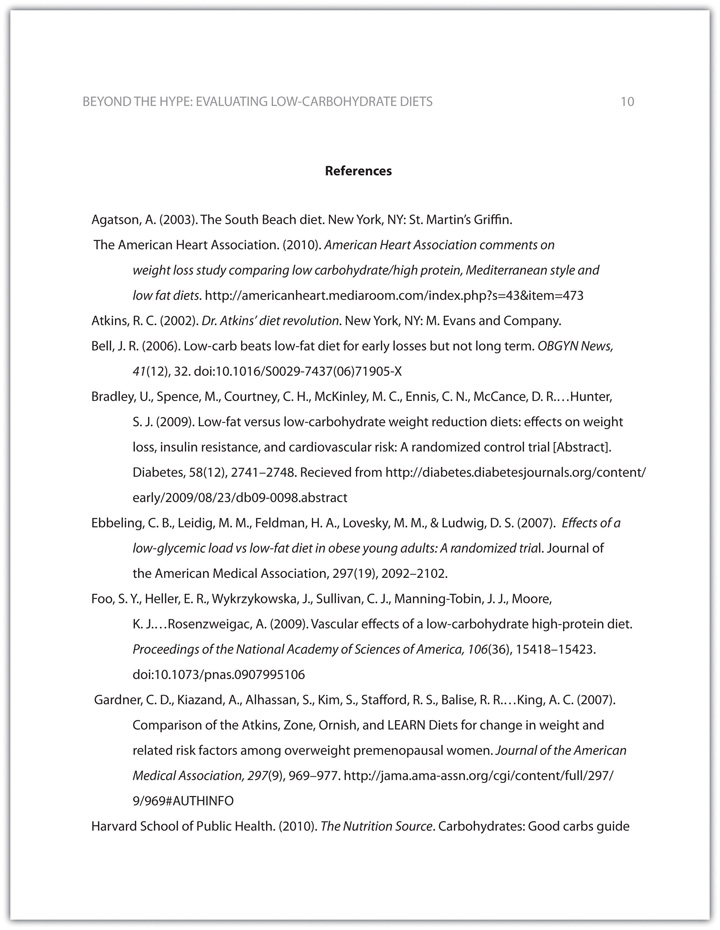

Reference List: Common Reference List Examples

Article (with doi).

Alvarez, E., & Tippins, S. (2019). Socialization agents that Puerto Rican college students use to make financial decisions. Journal of Social Change , 11 (1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.5590/JOSC.2019.11.1.07

Laplante, J. P., & Nolin, C. (2014). Consultas and socially responsible investing in Guatemala: A case study examining Maya perspectives on the Indigenous right to free, prior, and informed consent. Society & Natural Resources , 27 , 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2013.861554

Use the DOI number for the source whenever one is available. DOI stands for "digital object identifier," a number specific to the article that can help others locate the source. In APA 7, format the DOI as a web address. Active hyperlinks for DOIs and URLs should be used for documents meant for screen reading. Present these hyperlinks in blue and underlined text (the default formatting in Microsoft Word), although plain black text is also acceptable. Be consistent in your formatting choice for DOIs and URLs throughout your reference list. Also see our Quick Answer FAQ, "Can I use the DOI format provided by library databases?"

Jerrentrup, A., Mueller, T., Glowalla, U., Herder, M., Henrichs, N., Neubauer, A., & Schaefer, J. R. (2018). Teaching medicine with the help of “Dr. House.” PLoS ONE , 13 (3), Article e0193972. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193972

For journal articles that are assigned article numbers rather than page ranges, include the article number in place of the page range.

For more on citing electronic resources, see Electronic Sources References .

Article (Without DOI)

Found in a common academic research database or in print.

Casler , T. (2020). Improving the graduate nursing experience through support on a social media platform. MEDSURG Nursing , 29 (2), 83–87.

If an article does not have a DOI and you retrieved it from a common academic research database through the university library, there is no need to include any additional electronic retrieval information. The reference list entry looks like the entry for a print copy of the article. (This format differs from APA 6 guidelines that recommended including the URL of a journal's homepage when the DOI was not available.) Note that APA 7 has additional guidance on reference list entries for articles found only in specific databases or archives such as Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, UpToDate, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, and university archives. See APA 7, Section 9.30 for more information.

Found on an Open Access Website

Eaton, T. V., & Akers, M. D. (2007). Whistleblowing and good governance. CPA Journal , 77 (6), 66–71. http://archives.cpajournal.com/2007/607/essentials/p58.htm

Provide the direct web address/URL to a journal article found on the open web, often on an open access journal's website. In APA 7, active hyperlinks for DOIs and URLs should be used for documents meant for screen reading. Present these hyperlinks in blue and underlined text (the default formatting in Microsoft Word), although plain black text is also acceptable. Be consistent in your formatting choice for DOIs and URLs throughout your reference list.

Weinstein, J. A. (2010). Social change (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

If the book has an edition number, include it in parentheses after the title of the book. If the book does not list any edition information, do not include an edition number. The edition number is not italicized.

American Nurses Association. (2015). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.).

If the author and publisher are the same, only include the author in its regular place and omit the publisher.

Lencioni, P. (2012). The advantage: Why organizational health trumps everything else in business . Jossey-Bass. https://amzn.to/343XPSJ

As a change from APA 6 to APA 7, it is no longer necessary to include the ebook format in the title. However, if you listened to an audiobook and the content differs from the text version (e.g., abridged content) or your discussion highlights elements of the audiobook (e.g., narrator's performance), then note that it is an audiobook in the title element in brackets. For ebooks and online audiobooks, also include the DOI number (if available) or nondatabase URL but leave out the electronic retrieval element if the ebook was found in a common academic research database, as with journal articles. APA 7 allows for the shortening of long DOIs and URLs, as shown in this example. See APA 7, Section 9.36 for more information.

Chapter in an Edited Book

Poe, M. (2017). Reframing race in teaching writing across the curriculum. In F. Condon & V. A. Young (Eds.), Performing antiracist pedagogy in rhetoric, writing, and communication (pp. 87–105). University Press of Colorado.

Include the page numbers of the chapter in parentheses after the book title.

Christensen, L. (2001). For my people: Celebrating community through poetry. In B. Bigelow, B. Harvey, S. Karp, & L. Miller (Eds.), Rethinking our classrooms: Teaching for equity and justice (Vol. 2, pp. 16–17). Rethinking Schools.

Also include the volume number or edition number in the parenthetical information after the book title when relevant.

Freud, S. (1961). The ego and the id. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 19, pp. 3-66). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1923)

When a text has been republished as part of an anthology collection, after the author’s name include the date of the version that was read. At the end of the entry, place the date of the original publication inside parenthesis along with the note “original work published.” For in-text citations of republished work, use both dates in the parenthetical citation, original date first with a slash separating the years, as in this example: Freud (1923/1961). For more information on reprinted or republished works, see APA 7, Sections 9.40-9.41.

Classroom Resources

Citing classroom resources.

If you need to cite content found in your online classroom, use the author (if there is one listed), the year of publication (if available), the title of the document, and the main URL of Walden classrooms. For example, you are citing study notes titled "Health Effects of Exposure to Forest Fires," but you do not know the author's name, your reference entry will look like this:

Health effects of exposure to forest fires [Lecture notes]. (2005). Walden University Canvas. https://waldenu.instructure.com

If you do know the author of the document, your reference will look like this:

Smith, A. (2005). Health effects of exposure to forest fires [PowerPoint slides]. Walden University Canvas. https://waldenu.instructure.com

A few notes on citing course materials:

- [Lecture notes]

- [Course handout]

- [Study notes]

- It can be difficult to determine authorship of classroom documents. If an author is listed on the document, use that. If the resource is clearly a product of Walden (such as the course-based videos), use Walden University as the author. If you are unsure or if no author is indicated, place the title in the author spot, as above.

- If you cannot determine a date of publication, you can use n.d. (for "no date") in place of the year.

Note: The web location for Walden course materials is not directly retrievable without a password, and therefore, following APA guidelines, use the main URL for the class sites: https://class.waldenu.edu.

Citing Tempo Classroom Resources

Clear author:

Smith, A. (2005). Health effects of exposure to forest fires [PowerPoint slides]. Walden University Brightspace. https://mytempo.waldenu.edu

Unclear author:

Health effects of exposure to forest fires [Lecture notes]. (2005). Walden University Brightspace. https://mytempo.waldenu.edu

Conference Sessions and Presentations

Feinman, Y. (2018, July 27). Alternative to proctoring in introductory statistics community college courses [Poster presentation]. Walden University Research Symposium, Minneapolis, MN, United States. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/symposium2018/23/

Torgerson, K., Parrill, J., & Haas, A. (2019, April 5-9). Tutoring strategies for online students [Conference session]. The Higher Learning Commission Annual Conference, Chicago, IL, United States. http://onlinewritingcenters.org/scholarship/torgerson-parrill-haas-2019/

Dictionary Entry

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Leadership. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary . Retrieved May 28, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/leadership

When constructing a reference for an entry in a dictionary or other reference work that has no byline (i.e., no named individual authors), use the name of the group—the institution, company, or organization—as author (e.g., Merriam Webster, American Psychological Association, etc.). The name of the entry goes in the title position, followed by "In" and the italicized name of the reference work (e.g., Merriam-Webster.com dictionary , APA dictionary of psychology ). In this instance, APA 7 recommends including a retrieval date as well for this online source since the contents of the page change over time. End the reference entry with the specific URL for the defined word.

Discussion Board Post

Osborne, C. S. (2010, June 29). Re: Environmental responsibility [Discussion post]. Walden University Canvas. https://waldenu.instructure.com

Dissertations or Theses

Retrieved From a Database

Nalumango, K. (2019). Perceptions about the asylum-seeking process in the United States after 9/11 (Publication No. 13879844) [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Retrieved From an Institutional or Personal Website

Evener. J. (2018). Organizational learning in libraries at for-profit colleges and universities [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. ScholarWorks. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6606&context=dissertations

Unpublished Dissertation or Thesis

Kirwan, J. G. (2005). An experimental study of the effects of small-group, face-to-face facilitated dialogues on the development of self-actualization levels: A movement towards fully functional persons [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center.

For further examples and information, see APA 7, Section 10.6.

Legal Material

For legal references, APA follows the recommendations of The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation , so if you have any questions beyond the examples provided in APA, seek out that resource as well.

Court Decisions

Reference format:

Name v. Name, Volume Reporter Page (Court Date). URL

Sample reference entry:

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/347us483

Sample citation:

In Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Supreme Court ruled racial segregation in schools unconstitutional.

Note: Italicize the case name when it appears in the text of your paper.

Name of Act, Title Source § Section Number (Year). URL

Sample reference entry for a federal statute:

Individuals With Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 et seq. (2004). https://www.congress.gov/108/plaws/publ446/PLAW-108publ446.pdf

Sample reference entry for a state statute:

Minnesota Nurse Practice Act, Minn. Stat. §§ 148.171 et seq. (2019). https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/148.171

Sample citation: Minnesota nurses must maintain current registration in order to practice (Minnesota Nurse Practice Act, 2010).

Note: The § symbol stands for "section." Use §§ for sections (plural). To find this symbol in Microsoft Word, go to "Insert" and click on Symbol." Look in the Latin 1-Supplement subset. Note: U.S.C. stands for "United States Code." Note: The Latin abbreviation " et seq. " means "and what follows" and is used when the act includes the cited section and ones that follow. Note: List the chapter first followed by the section or range of sections.

Unenacted Bills and Resolutions

(Those that did not pass and become law)

Title [if there is one], bill or resolution number, xxx Cong. (year). URL

Sample reference entry for Senate bill:

Anti-Phishing Act, S. 472, 109th Cong. (2005). https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/senate-bill/472

Sample reference entry for House of Representatives resolution:

Anti-Phishing Act, H.R. 1099, 109th Cong. (2005). https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/1099

The Anti-Phishing Act (2005) proposed up to 5 years prison time for people running Internet scams.

These are the three legal areas you may be most apt to cite in your scholarly work. For more examples and explanation, see APA 7, Chapter 11.

Magazine Article

Clay, R. (2008, June). Science vs. ideology: Psychologists fight back about the misuse of research. Monitor on Psychology , 39 (6). https://www.apa.org/monitor/2008/06/ideology

Note that for citations, include only the year: Clay (2008). For magazine articles retrieved from a common academic research database, leave out the URL. For magazine articles from an online news website that is not an online version of a print magazine, follow the format for a webpage reference list entry.

Newspaper Article (Retrieved Online)

Baker, A. (2014, May 7). Connecticut students show gains in national tests. New York Times . http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/08/nyregion/national-assessment-of-educational-progress-results-in-Connecticut-and-New-Jersey.html

Include the full date in the format Year, Month Day. Do not include a retrieval date for periodical sources found on websites. Note that for citations, include only the year: Baker (2014). For newspaper articles retrieved from a common academic research database, leave out the URL. For newspaper articles from an online news website that is not an online version of a print newspaper, follow the format for a webpage reference list entry.

OASIS Resources

Oasis webpage.

OASIS. (n.d.). Common reference list examples . Walden University. https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/writingcenter/apa/references/examples

For all OASIS content, list OASIS as the author. Because OASIS webpages do not include publication dates, use “n.d.” for the year.

Interactive Guide

OASIS. (n.d.). Embrace iterative research and writing [Interactive guide]. Walden University. https://academics.waldenu.edu/oasis/iterative-research-writing-web

For OASIS multimedia resources, such as interactive guides, include a description of the resource in brackets after the title.

Online Video/Webcast

Walden University. (2013). An overview of learning [Video]. Walden University Canvas. https://waldenu.instructure.com

Use this format for online videos such as Walden videos in classrooms. Most of our classroom videos are produced by Walden University, which will be listed as the author in your reference and citation. Note: Some examples of audiovisual materials in the APA manual show the word “Producer” in parentheses after the producer/author area. In consultation with the editors of the APA manual, we have determined that parenthetical is not necessary for the videos in our courses. The manual itself is unclear on the matter, however, so either approach should be accepted. Note that the speaker in the video does not appear in the reference list entry, but you may want to mention that person in your text. For instance, if you are viewing a video where Tobias Ball is the speaker, you might write the following: Tobias Ball stated that APA guidelines ensure a consistent presentation of information in student papers (Walden University, 2013). For more information on citing the speaker in a video, see our page on Common Citation Errors .

Taylor, R. [taylorphd07]. (2014, February 27). Scales of measurement [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDsMUlexaMY

OASIS. (2020, April 15). One-way ANCOVA: Introduction [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/_XnNDQ5CNW8

For videos from streaming sites, use the person or organization who uploaded the video in the author space to ensure retrievability, whether or not that person is the speaker in the video. A username can be provided in square brackets. As a change from APA 6 to APA 7, include the publisher after the title, and do not use "Retrieved from" before the URL. See APA 7, Section 10.12 for more information and examples.

See also reference list entry formats for TED Talks .

Technical and Research Reports

Edwards, C. (2015). Lighting levels for isolated intersections: Leading to safety improvements (Report No. MnDOT 2015-05). Center for Transportation Studies. http://www.cts.umn.edu/Publications/ResearchReports/reportdetail.html?id=2402

Technical and research reports by governmental agencies and other research institutions usually follow a different publication process than scholarly, peer-reviewed journals. However, they present original research and are often useful for research papers. Sometimes, researchers refer to these types of reports as gray literature , and white papers are a type of this literature. See APA 7, Section 10.4 for more information.

Reference list entires for TED Talks follow the usual guidelines for multimedia content found online. There are two common places to find TED talks online, with slightly different reference list entry formats for each.

TED Talk on the TED website

If you find the TED Talk on the TED website, follow the format for an online video on an organizational website:

Owusu-Kesse, K. (2020, June). 5 needs that any COVID-19 response should meet [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/kwame_owusu_kesse_5_needs_that_any_covid_19_response_should_meet

The speaker is the author in the reference list entry if the video is posted on the TED website. For citations, use the speaker's surname.

TED Talk on YouTube

If you find the TED Talk on YouTube or another streaming video website, follow the usual format for streaming video sites:

TED. (2021, February 5). The shadow pandemic of domestic violence during COVID-19 | Kemi DaSilvalbru [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PGdID_ICFII

TED is the author in the reference list entry if the video is posted on YouTube since it is the channel on which the video is posted. For citations, use TED as the author.

Walden University Course Catalog

To include the Walden course catalog in your reference list, use this format:

Walden University. (2020). 2019-2020 Walden University catalog . https://catalog.waldenu.edu/index.php

If you cite from a specific portion of the catalog in your paper, indicate the appropriate section and paragraph number in your text:

...which reflects the commitment to social change expressed in Walden University's mission statement (Walden University, 2020, Vision, Mission, and Goals section, para. 2).

And in the reference list:

Walden University. (2020). Vision, mission, and goals. In 2019-2020 Walden University catalog. https://catalog.waldenu.edu/content.php?catoid=172&navoid=59420&hl=vision&returnto=search

Vartan, S. (2018, January 30). Why vacations matter for your health . CNN. https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/why-vacations-matter/index.html

For webpages on the open web, include the author, date, webpage title, organization/site name, and URL. (There is a slight variation for online versions of print newspapers or magazines. For those sources, follow the models in the previous sections of this page.)

American Federation of Teachers. (n.d.). Community schools . http://www.aft.org/issues/schoolreform/commschools/index.cfm

If there is no specified author, then use the organization’s name as the author. In such a case, there is no need to repeat the organization's name after the title.

In APA 7, active hyperlinks for DOIs and URLs should be used for documents meant for screen reading. Present these hyperlinks in blue and underlined text (the default formatting in Microsoft Word), although plain black text is also acceptable. Be consistent in your formatting choice for DOIs and URLs throughout your reference list.

Related Resources

Knowledge Check: Common Reference List Examples

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Reference List: Overview

- Next Page: Common Military Reference List Examples

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Referencing: About End-Text References

End-text references.

A reference list contains the information a reader needs to be able to identify and retrieve works cited in a text. This information is in the form of end-text references.

End-text references comprise four elements:

- Author : who is responsible for this work? An author may be an individual; multiple people; a group (government agency, organisation or institution); or a combination of groups and people.

- Date : when was the work published? Date of publication can be year only; year, month and day (exact date); year and month; year and season; or a range of dates (e.g. range of years).

- Title : what is the work called? There are two categories of titles: works that stand alone (e.g. reports, whole books, data sets, webpages, and films), and works that are part of a greater whole (e.g. edited book chapters, podcast and television episodes, and journal articles).

- Source : where can I find the work? This might be a publisher, a web address/URL, or both.

End each element with a full stop, with the exception of the URL or DOI (adding a full stop can interfere with accessing the content using the link).

These elements come together to form an end-text citation that follows this format:

Author. (Date). Title of the work . Source.

Example of an end-text citation for a whole book with no DOI

Grellier, J., & Goerke, V. (2018). Communications toolkit (4th ed.). Cengage Learning Australia.

For a brief (6-minute) introduction to end-text referencing, view the video below:

See below for the specific rules for formatting each element, from author to source (including URLs).

For information about formatting the reference list as a whole, see the page Reference List .

There are some variations to this general reference format depending on the type of work you are citing. Reference Examples can help you format a variety of reference types.

Reference Examples

Specific reference examples.

Examples of types of works that you might want to reference.

- Journal articles

- Newspaper articles

- Magazine articles

- Proprietary databases

- Chapters in a book

- Encyclopaedia entries

- Dictionary entries

- Wikipedia entries

- Republished editions of a book

- Translated books

- United Nations Reports

- Technical reports or standards

- Conference papers

- Code of ethics

- Thesis/dissertation

- TV episodes

- YouTube or streaming videos

- Plays or performances

- Music recordings

- Software or mobile apps

- Online news sources

- Lecture notes and class materials

- Social media

- Format the author's name as family name, comma, first initials. Each initial is separated by a space.

- If the author is an organisation, provide its full name, even if it is abbreviated elsewhere. See below for more information.

- If two authors are both group authors, do not use a comma between them.

- Include up to 20 authors. If a work has more than 20, provide the first 19 authors, an ellipsis (. . .), and then the final name. Do not include an ampersand. The Quick Guide PDF has an example of a work with more than 20 authors.

- A full stop goes at the end of the author element (unless one is there already).

Author, A., Author, B. B., & Author, C.

Bureau of Meteorology & Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation.

When the author is a group, such as a company or a government department, you should provide its full name in the end-text reference, even if it is abbreviated elsewhere. Deciding what counts as its full name can be tricky. You might need to look for an "About Us" or similar page to find out how the organisation should be credited. Visit the APA Style website for more information.

- If a webpage or report is on a government or company website, you should generally use the organisation as the author.

- Sometimes both an individual and a group seem to be the author. If there is a person listed prominently on the work (e.g. on the cover, title page, suggested citation, or the top of an article), that is usually the author; the group would then act as the 'publisher'. Use your judgment to decide who is being presented as the author, and which author would help someone else find the work using your reference.

- If multiple layers of government agencies are listed as the author, use the most specific agency as the author, and include the parent agencies in the source element as 'publisher'.

- Do not include jurisdiction (e.g. Commonwealth of Australia) unless it is needed to distinguish between two organisations that would otherwise have the same name.

The National Cancer Institute is a US-based group which is part of the National Institutes of Health, which is itself part of the Department of Health and Human Services. The author should be only the most specific group:

National Cancer Institute.

The full reference would include the parent bodies as the 'publisher', ordered starting from the largest level, and separated by commas:

National Cancer Institute. (Date). Title of the work . Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. https://www......

Specialised roles

Some reference types, such as films or edited books, routinely credit major contributors who would not be described as the 'author' of the work. For these contributors, include their role in parentheses after their name in the end-text reference. (Do not include the role in the in-text citation.) If the role is editor, it should be abbreviated as (Ed.), or (Eds.) for multiple editors.

Scott, R. (Director).

Cunningham, S., & Turner, G. (Eds.).

Saunders, A. (Host).

Patterson, J. (with Marklund, L.).

If you can not find the author of a work, including a group or organisation that is responsible for the work, use the title in place of the author. The title spot can be left blank. (Formatting for in-text citation is available here .)

Do not cite the author as "Anonymous" unless the work was published under that pseudonym.

Italian government declares state of emergency in flood-ravaged Venice. (2019, November 15). The Age . https://www.theage.com.au/world/europe/italian-government-set-to-declare-state-of-emergency-in-venice-20191115-p53ast.html

Unusual spelling & capitalisation, and titles & ranks

Use the spelling and capitalisation the author uses.

de la Cruz, J.

Johnson-Lee, H., & Johnson Vasquez, L.

If an author's first name is hyphenated, include both initials and the hyphen if both names are capitalised.

Young-Ha Kim ⇒ Kim, Y.-H.

Lee-ann Raboso ⇒ Raboso, L.

Do not include titles and ranks, unless they are part of the author's name.

John Smith, Jr ⇒ Smith, J., Jr.

John Smith, M.D., Ph.D. ⇒ Smith, J.

Lady Gaga ⇒ Lady Gaga.

If the real name of someone who usually publishes under a username is known, give the real name first but include the username in brackets:

Dorsey, J. [@jack].

Only the family name will be included in in-text citations: (Dorsey, 2020).

If only the username is known, do not put it in brackets. The username will be treated as the author's name for in-text and end-text citations, e.g. (mt2mt2, 2015).

Give the date the item was published - usually just the year.

For some items that are published more frequently, such as webpages and newspaper articles, a more specific date is required (if available) to help the reader find the specific work you are citing.

Formatting this element

The date goes within parentheses:

(2012, May 18).

(2019, Spring).

Note that the copyright date at the footer of a webpage is usually not the date the content was published.

If you can not find the publication date for an item, use the abbreviation for "no date":

Titles usually do not keep the same formatting as the original source. Keep the original spelling, but capitalisation and italics in titles are standardised to fit the APA style rules.

Formatting: italics

Titles of stand-alone publications (works that are complete in themselves, like a whole book or a report) are formatted in italics in your end-text references. Titles of items that are part of a larger work (such as articles and chapters) are not in italics.

Stand-alone work:

Project management: The managerial process.

Part of a greater work:

Italian government declares state of emergency in flood-ravaged Venice.

Formatting: capitalisation

There are two types of capitalisation used in APA style referencing:

- Sentence case: Most words are lowercase, except: the first word of the title, the first word of any subtitles, proper nouns (e.g. places and people), and acronyms.

- Title case: Capitalise the first word of the title, the first word of any subtitles, any major or content words, and any word with four or more letters.

Most titles in your end-text referencing will be in sentence case. If you are mentioning the title of a journal as a whole, a newspaper or magazine, an organisation's name, or a publisher, these will usually be in title case.

Sentence case:

The role of occupation in an integrated boycott model: A cross-regional study in China.

Title case:

Health Promotion Journal of Australia.

Gone With the Wind.

Jump to information about:

Edition, report, or volume number

Unusual formats

Original work in another language

Republished or translated works

Works with an edition, report, or volume number

If a work has an edition, report, or volume number, include it in parentheses after the title. Do not put a full stop between the title and this descriptive information. This element is not in italics, even if the title is.

- Use the abbreviation "ed." for edition, and "Vol." for volume.

- Edition is written with numbers, not in superscript: use "6th ed.", not "Sixth ed." or "6 th ed." Revised edition is abbreviated to "Rev. ed."

- For reports, give the report number as it appears on the work, as in the second and third examples below.

Effective security management (6th ed.).

Land management and farming in Australia, 2014-15 (Cat. No. 4627.0).

Foundation to year 10 curriculum: Language for interaction (ACELA1428).

If there is both a volume and an edition, the edition comes first.

Clinical nutrition (2nd ed., Vol. 3).

Works with an unusual format

If the format is something unusual for an academic context (something other than books, journal articles, and reports), you can include a description of the format after the title. The description will not be in italics, even if the title is.

Guide to the wildflowers of Perth [Brochure].

Don't let me be misunderstood [Song].

Journeys towards expertise in technology-supported teaching [Doctoral dissertation, Edith Cowan University].

Works with no title

If the work has no title, use a description of the work in square brackets.

[Map showing local Perth election results in 2018].

Do not use italics for your description, even if the title would usually be in italics.

If this is a work with an unusual format (e.g. Photograph, Lecture recording, or Map), you can include the type as part of the description.

Works in another language

Before you use a work in another language as a reference for an assignment, check with your unit coordinator that this is acceptable. They might prefer that you find an English-language source so that they can check the reference for themselves.

If you are citing a work in a language other than the language of your own writing, and you read that work in its original language, you should include a translation of the title element. The translated title does not need to be literal: it should inform the reader what the work is about. The translation should be within square brackets, following the original title, and is not italicised even if the title is.

Schweriner Café-Besucher tragen Schwimmnudel-Hüte [Visitors to Schwerin cafe wear pool noodle hats for social distancing].

Nihongo no goi tokusei [Lexical characteristics of Japanese language].

All other details should be written in the original language. This will make it easier to locate the source. If the language does not use the Roman alphabet (for instance, if it is written in a language like Hindi, Mandarin, or Arabic; or in Japanese, as in the example above), you should transliterate those details into the Roman alphabet if possible.

Republished or translated works

If a work has been republished in a different year, include information about the original publication date at the end of the reference. If other creators had a significant role in creating the new edition, include information about the editor, translator, or (as below) narrator in parentheses after the title; if the type of work needs explanation, include the type in square brackets. These elements are not in italics, even if the title is. There should be no full stop between the title and extra information in the title element, or after the original publication date.

An example of this sort of work might be an ebook published in a different year to the original book, a version translated into a new language or format, or a new edition of a classic book; this is not intended for reprints of the same work by the same publisher soon after publication.

Heller, J. (2008). Catch-22 (T. White, Narr.) [Audiobook]. Hachette Audio UK. (Original work published 1961)

Both dates will appear in the in-text reference for these works: (Heller, 1961/2008).

The source of a work is usually:

- The publisher, parent body of an organisation, or overarching website for a webpage

Note that an item might have both a publisher/website and a URL or DOI.

If the publisher is the same group or individual as the author, do not duplicate the information in your reference. You should still include a DOI or URL if appropriate.

Bureau of Meteorology. (2019). Monthly weather review: Australia: September 2019. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/mwr/aus/mwr-aus-201909.pdf

Bureau of Meteorology is both the author and the publisher of this report, so the reference does not have a publisher listed in the source.

DOI/URL notes

- Do not place a full stop after a DOI or URL.

- If there is a DOI, always include it. You do not need to include a URL if there is a DOI.

- If using a URL, use a permanent link if there is one. If possible, link directly to the work you used.

- URLs and DOIs should be live (the reader should be able to click the link), but whether they look like hyperlinks (blue and underlined) or like the rest of your text is a style decision that you can make. Check your assignment guidelines or ask your lecturer if they have a preference.

- DOI should be displayed in the format: https://doi.org/10.xxxx

Oxford University Press.

Australian Institute of Criminology. https://aic.gov.au/publications/special/005

https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.114.015966

YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/charlie#p/u/4/qjIsdbBsE8g

URL shorteners

APA style now allows link shorteners where a link is overly complex or long.

- This advice is aimed largely at student papers: it is usually not appropriate for publication or theses.

- Some URL shorteners only work for a few days, so make sure the link will work for as long as you need it to, including marking and potential appeal periods.

- Check that shortened links are acceptable for your assignment.

- There is no requirement to shorten a URL . Even if a link is very long, you can include it in your reference list.

A URL shortener will take a long URL and make it look more like this:

http://tiny.cc/sp4gpz

Some websites have their own short links that you can use, specific to their site.

APA 7 Tutorial: DOIs and URLs

Learn how to use the two types of electronic retrieval information found in references, digital object identifiers (DOIs) and uniform resource locators (URLs), including how to cite documents retrieved from research databases and websites.

Academic Writer, © 2020 American Psychological Association.

No author

If a work seems to have no author, check to see if an organisation or group might be responsible for it. If there is not a clear group author either, you should use the title in place of the author.

Use the title, or the first few words of the title if it is long, in your in-text citations as well.

The date in a citation refers to the date the content was published. If you can't locate this information, use the abbreviation for "no date" in place of the year: n.d.

Use this abbreviation in your in-text citations as well.

If there is no title, use a description of the work in square brackets.

If the work would usually have a type (e.g. Photograph, Data set, Recording of a play) in brackets after the title, you can include that in the title description.

If a work you used is not available to the intended audience of your assignment or project, consider whether it is appropriate to use it as evidence.

If you decide to use it, you should cite the work as personal communication . This sort of citation does not have a reference list entry, because a reader would not be able to locate the work you used. It uses only in-text citations, with a slightly different format to normal in-text citations.

If you are using your own research data, see Section 8.36 in the APA manual.

In general, cite:

- what is available on the work you are citing, and

- what would make it easy for another person to find that work.

You should have some information for each of the four elements (author, date, title, source), but if a detail does not exist, leave it off.

Missing reference information on the APA Style website.

APA 7 Tutorial: Missing Reference Elements

Learn about the four reference elements of an APA Style reference: the author, date, title, and source.

What Is a DOI?

If there is a DOI for a source you are citing, include it at the end of your reference. This takes the place of a URL.

A digital object identifier ( DOI ) is a unique code used to identify content and provide a persistent link to a document on the internet. A publisher assigns a DOI when a journal article is published and made available electronically.

A DOI will usually be found on the source near other reference elements like title and author. For APA style referencing, you should put the DOI in the following format:

https://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2016.59.1.1

Make sure the DOI does not include EZProxy in the URL. It should just be https://doi.org/10.xxxx. If the DOI is not already in URL format (for instance, the example above might just say DOI: 10.5468/ogs.2016.59.1.1), you can attach "https://doi.org/" to the front of the DOI number.

For further information, refer to Crossref or the APA's Academic Writer tutorial below. Read the information about URL shorteners under Source: formatting and notes above before using a short DOI.

- Crossref's display guidelines

- Academic Writer Quick Guide: DOIs and URLs

- DOI link shorteners

- << Previous: Reference List

- Next: Figures, Tables, & Images >>

- Workshops & Videos

- In-Text Citations

- End-Text Reference Examples

- Reference List

- About End-Text References

- Figures, Tables, & Images

- Creative Commons & Copyright This link opens in a new window

- Australian Legal Materials

- EndNote This link opens in a new window

Common Abbrevations

Some words and phrases are abbreviated in all end-text references in APA style. Here's a list of common abbreviations from Section 9.50 of the Manual . Take note of capitalisation and punctuation.

Library Contact

- [email protected]

- (61) 8 6304 5525

Library Links

- Library Workshops

- ECU Library Search

- Borrowing Items

- Room Bookings

Quick Links

- Academic Integrity

- Ask Us @ ECU

- LinkedIn Learning

- Student Guide - My Uni Start

More about ECU

- All Online Courses

- Last Updated: May 23, 2024 12:13 PM

- URL: https://ecu.au.libguides.com/referencing

Edith Cowan University acknowledges and respects the Noongar people, who are the traditional custodians of the land upon which its campuses stand and its programs operate. In particular ECU pays its respects to the Elders, past and present, of the Noongar people, and embrace their culture, wisdom and knowledge.

How to Write References and Cite Sources in a Research Paper

Table of contents

- 1.1 Academic Integrity

- 1.2 Avoiding Plagiarism

- 1.3 Building Credibility

- 1.4 Facilitating Further Research

- 2.1 APA (American Psychological Association)

- 2.2 MLA (Modern Language Association)

- 2.3 Chicago Style

- 2.4 IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers)

- 3.1 Author(s)

- 3.2 Title of the Source

- 3.3 Publication Date

- 3.4 Publisher

- 3.5 Page Numbers

- 3.6 DOI (Digital Object Identifier) or URL (Uniform Resource Locator)

- 4.1.3 Chicago

- 4.2.1 Citing Multiple Authors

- 4.2.4 Chicago

- 4.3 Page Numbers in In-Text Citations

- 5.1 Formatting and Organizing Your References

- 5.2 Alphabetizing Your References

- 5.3.2 Journal

- 5.3.3 Chapter

- 5.3.4 Conference Paper/Presentation

- 5.3.5 Online Sources

- 6.1 Verify Your Source

- 6.2 Follow the One Style Guide

- 6.3 Verify DOI and URLs

- 6.4 Online Citation Generators

- 6.5 Use University Libraries and Writing Centers

- 7 Leave No Stone Unturned!

Citation is necessary while writing your school essay, a publication, or a Master’s thesis. We all want our efforts to be acknowledged, right? The lack of references and citations can make the source think you are trying to steal their work. Hence, the question is how to go about making references.

Do you want to learn how to cite in a research paper? Then this article is for you, as it contains the details of how to reference when writing a research paper. There is a standard way to do this in educational journals and organizational publications.

Hence, a researcher must understand how to reference their writings or journals. It is another thing to write a journal properly, but crediting the sources is more crucial.

Follow this guide to learn:

- The importance of referencing and citations for your academic works;

- How to cite in APA, MLA, Chicago, IEEE, and ASA styles;

- Essential guidelines to follow for a published work.

Why Referencing and Citation Matter

Another important question is: What is the need for referencing and citation? The major reason for citations in research paper format is to serve as directional cues for the employed knowledge. When you cite, readers can know that some portions of your content belong to you. Hence, it is easier to identify how recent the information is.

Citation for your paper comes with several advantages. They include:

Academic Integrity

The citation affirms the integrity of your academic writing. In this information age, there are several details, and it can be difficult to authenticate. When you reference, it helps readers understand the necessity of the discussed topic. Referencing certain authors can give more authority to your papers.

Avoiding Plagiarism

Plagiarism refers to the mindless lifting of details from another material without acknowledging the details. For the source, they could believe you are stealing from them. In most countries, copyright infringement is a punishable crime and can make you lose your hard work.

Building Credibility

Credibility is the goal of every academic scholar. There is no better way to gain relevance than by citing sources from other credible ones.

Facilitating Further Research

For other researchers like you, providing citations can serve as other sources for more information. It helps them to know other philosophies about the subject.

Choosing the Right Citation Style

Now that the advantages have been established, the new worry is the choice of the right style. There are several styles with their respective peculiarities. For example, the MLA writing style is common in liberal scientific paper citations. Let’s delve more into MLA formatting for research papers and other styles.

APA (American Psychological Association)

The commonest style used by many scholars is APA formatting , especially if there is no stated style. This approach employs the use of in-text citations to explain the source. It’s the simplest form of citation.

Here is an in-text referencing example:

“Exercise is a good way to recover from ailments.” APA, n.d. (American Psychological Association).

The reference style includes:

- The author’s name;

- The author’s name is in parenthesis to follow the referenced excerpt;

- The publication date.

MLA (Modern Language Association)

MLA-style formation is concise and known for its scientific referencing format. The peculiarity of the MLA citation is its source citation, episode title, and document layout. You have to:

- Include the parenthetical citation;

- Create some spaces away from the left margin;

- Include the author’s or source’s name.

Ensure you capitalize every word when including the names. You can employ professional MLA Citation Generators to make the compilation easier. It is perfect for the citation format of scientific papers.

Chicago Style

Chicago’s style is famous for two things:

- The in-text citation within the paper;

- The reference list is at its end.

It is an author-date approach. Hence, the in-text citation for a research paper has the author’s or source name and publication year.

IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers)

This employs the use of numbers. It is chronological as it arranges the citation based on the order of appearance. A click on it takes the reader to the full reference at the end of the paper. To make it easier, you can employ IEEE Citation Maker for a well-curated task. This way, you won’t have to worry about the manual compilation of the IEEE citation style.

This is similar to the author-date approach by Chicago Style. You can:

- Create the quotation;

- Include the parentheses for the author’s name and publication date;

- Add the page number using a colon.

Components of a Citation

Do you want to know how to complete a citation for your professional research paper writing service and research paper? Learn about its components.

The author is also regarded as the source. It is the original writer of the material you are referencing. Sometimes, there may be multiple authors. Do not miss out on anyone while citing a research paper.

Title of the Source

The title of the source is often the name given to the material by the author.

Publication Date

As the name implies, this refers to the date the source was published. Frequently, most writers include it at the start of their material. State the exact month and year of publication, separated with a comma. See example:

“(2016, March 7).”

Including the publisher’s details is only necessary for the full reference. It should be at the end of the paper. It can facilitate further research.

Page Numbers

The page number is necessary, as it helps to easily refer to different sections of the paper.

DOI (Digital Object Identifier) or URL (Uniform Resource Locator)

A DOI is a link to a resource on the internet. The resource can be a book or its chapter. On the other hand, a URL is an address that indicates where the resource can be found. It helps to locate the resource. The use of URLs and DOIs directs readers to the digital identifier of the source.

In-Text Citations

An in-text citation for a research paper is the brief form of the bibliography that you include in the body of the content. It contains the author’s family name and year of publication. It provides enough details to help users know the source in their reference list. Each citation format for research papers is unique.

See citation examples below.

How to Cite Direct Quotations for Each Citation Style

The general rule in referencing is that in-text citations must have a corresponding entry in your reference list. Let’s see how!

There are two types of APA in-text citations:

Parenthetical:

The researchers concluded, “Climate change poses significant challenges for coastal communities” (Johnson & Lee, 2021, p. 78).

In their study on the effects of exercise on mental health, Smith and Johnson (2019) found that regular physical activity was associated with a significant decrease in symptoms of anxiety and depression. According to their research, engaging in exercise three times a week for at least 30 minutes had a positive impact on participants’ overall well-being.

APA in-text citation style employs the source’s name and publication year. A direct quotation will include the page number. Remember, you can generate a citation in a research paper using the APA style via a citation generator.

MLA is known as the scientific style of citation. The uniqueness of MLA Style formatting is the use of a direct quote (in quotes), the Author’s name and page number (in parentheses).

In the novel “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Atticus Finch imparts wisdom to his children, saying, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view… until you climb into his skin and walk around in it” (Lee 30).

For Chicago, you are to include a parenthetical citation, the author’s name, the publication year, and the quote’s page number.

As Adams (2009) argues, “History is a vast early warning system” (53).

IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) style typically uses numerical citations in square brackets for in-text citations. It doesn’t rely heavily on direct quotations in the same way as some other citation styles, like APA or MLA. Instead, IEEE generally prefers paraphrasing and citing the source, but direct quotations can be used when necessary. Here’s an example of a direct quotation in IEEE style:

In-Text Citation:

As stated by Smith, “In most cases, the impedance of the transmission line remains relatively constant throughout its length” [1].

Corresponding Reference Entry:

[1] A. Smith, “Transmission Line Impedance Analysis,” IEEE Transactions on Electrical Engineering, vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 212-225, 2010.

ASA is different because it contains the author’s name, publication year, and even the page number.

According to Smith (2010), “Social institutions shape our behaviors and interactions in profound ways” (p. 45).

How to Cite Paraphrased Information

While writing a college paper, paraphrasing is important to achieve clarity, but it is ideal to cite the source of the paraphrased information. The proper way to cite paraphrased information is to include a parenthetical citation. The style of referencing for all citation styles doesn’t change, but they should be in parenthesis.

“Strength can be defined in terms of ability and acquired skills, according to (Jack et al. 2023).

Citing Multiple Authors

The technique is different when you are citing a source that has multiple authors. For the first-time citation, you should include the names of all the authors. The subsequent activities to generate a citation in APA should only include the first author’s surname and the proper use of ‘et al.’ However, you should include the surname and initials of all these authors in the full reference. Separate the authors with commas and ampersands before the final name.

Two Authors:

When a source has two authors, include both authors’ names in the in-text citation every time you reference the source. Use an ampersand (&) between the authors’ names, and include the year of publication in parentheses. For example:

(Smith & Johnson, 2020) found that…

Three to Five Authors:

When a source has three to five authors, list all authors in the first in-text citation. Use an ampersand (&) between the last two authors’ names. For subsequent citations of the same source, use only the first author’s name followed by “et al.” and the year. For example:

First citation: (Smith, Johnson, & Williams, 2018)…

Subsequent citations: (Smith et al., 2018)…

Six or More Authors:

When a source has six or more authors, you should use “et al.” in both the first and subsequent in-text citations, along with the year. For example:

(Smith et al., 2019) conducted a study on…

Group Authors:

When citing sources authored by a group, organization, or company, use the full name of the group or organization as the author in the in-text citation. If the abbreviation is well-known, you can use the abbreviation in subsequent citations. For example:

First citation: (American Psychological Association [APA], 2019)…

Subsequent citations: (APA, 2019)

When a source has two authors, include both authors’ names in the in-text citation, separated by the word “and.” For example:

(Smith and Johnson 45) found that…

Three or More Authors:

When a source has three or more authors, include only the first author’s name followed by “et al.” in the in-text citation. For example:

(Smith et al. 72) conducted a study on…

If a source has no identifiable author, use a shortened version of the title in the in-text citation. Enclose the title in double quotation marks or use italics if it’s a longer work (e.g., a book or film). For example:

(“Title of the Source” 28) argues that…

(American Psychological Association 62) states that…

Author-Date System:

In the Author-Date system, when a source has two authors, include both authors’ last names and the publication year in parentheses in the in-text citation, separated by an ampersand (&). For example:

(Smith & Johnson 2020) found that…

When a source has three or more authors, you can use “et al.” after the first author’s name in the in-text citation. For example:

(Smith et al. 2018) conducted a study on…