What Is A Research (Scientific) Hypothesis? A plain-language explainer + examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

If you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably noticing that the words “research hypothesis” and “scientific hypothesis” are used quite a bit, and you’re wondering what they mean in a research context .

“Hypothesis” is one of those words that people use loosely, thinking they understand what it means. However, it has a very specific meaning within academic research. So, it’s important to understand the exact meaning before you start hypothesizing.

Research Hypothesis 101

- What is a hypothesis ?

- What is a research hypothesis (scientific hypothesis)?

- Requirements for a research hypothesis

- Definition of a research hypothesis

- The null hypothesis

What is a hypothesis?

Let’s start with the general definition of a hypothesis (not a research hypothesis or scientific hypothesis), according to the Cambridge Dictionary:

Hypothesis: an idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved.

In other words, it’s a statement that provides an explanation for why or how something works, based on facts (or some reasonable assumptions), but that has not yet been specifically tested . For example, a hypothesis might look something like this:

Hypothesis: sleep impacts academic performance.

This statement predicts that academic performance will be influenced by the amount and/or quality of sleep a student engages in – sounds reasonable, right? It’s based on reasonable assumptions , underpinned by what we currently know about sleep and health (from the existing literature). So, loosely speaking, we could call it a hypothesis, at least by the dictionary definition.

But that’s not good enough…

Unfortunately, that’s not quite sophisticated enough to describe a research hypothesis (also sometimes called a scientific hypothesis), and it wouldn’t be acceptable in a dissertation, thesis or research paper . In the world of academic research, a statement needs a few more criteria to constitute a true research hypothesis .

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis (also called a scientific hypothesis) is a statement about the expected outcome of a study (for example, a dissertation or thesis). To constitute a quality hypothesis, the statement needs to have three attributes – specificity , clarity and testability .

Let’s take a look at these more closely.

Need a helping hand?

Hypothesis Essential #1: Specificity & Clarity

A good research hypothesis needs to be extremely clear and articulate about both what’ s being assessed (who or what variables are involved ) and the expected outcome (for example, a difference between groups, a relationship between variables, etc.).

Let’s stick with our sleepy students example and look at how this statement could be more specific and clear.

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

As you can see, the statement is very specific as it identifies the variables involved (sleep hours and test grades), the parties involved (two groups of students), as well as the predicted relationship type (a positive relationship). There’s no ambiguity or uncertainty about who or what is involved in the statement, and the expected outcome is clear.

Contrast that to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – and you can see the difference. “Sleep” and “academic performance” are both comparatively vague , and there’s no indication of what the expected relationship direction is (more sleep or less sleep). As you can see, specificity and clarity are key.

Hypothesis Essential #2: Testability (Provability)

A statement must be testable to qualify as a research hypothesis. In other words, there needs to be a way to prove (or disprove) the statement. If it’s not testable, it’s not a hypothesis – simple as that.

For example, consider the hypothesis we mentioned earlier:

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

We could test this statement by undertaking a quantitative study involving two groups of students, one that gets 8 or more hours of sleep per night for a fixed period, and one that gets less. We could then compare the standardised test results for both groups to see if there’s a statistically significant difference.

Again, if you compare this to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – you can see that it would be quite difficult to test that statement, primarily because it isn’t specific enough. How much sleep? By who? What type of academic performance?

So, remember the mantra – if you can’t test it, it’s not a hypothesis 🙂

Defining A Research Hypothesis

You’re still with us? Great! Let’s recap and pin down a clear definition of a hypothesis.

A research hypothesis (or scientific hypothesis) is a statement about an expected relationship between variables, or explanation of an occurrence, that is clear, specific and testable.

So, when you write up hypotheses for your dissertation or thesis, make sure that they meet all these criteria. If you do, you’ll not only have rock-solid hypotheses but you’ll also ensure a clear focus for your entire research project.

What about the null hypothesis?

You may have also heard the terms null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis, or H-zero thrown around. At a simple level, the null hypothesis is the counter-proposal to the original hypothesis.

For example, if the hypothesis predicts that there is a relationship between two variables (for example, sleep and academic performance), the null hypothesis would predict that there is no relationship between those variables.

At a more technical level, the null hypothesis proposes that no statistical significance exists in a set of given observations and that any differences are due to chance alone.

And there you have it – hypotheses in a nutshell.

If you have any questions, be sure to leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help you. If you need hands-on help developing and testing your hypotheses, consider our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

16 Comments

Very useful information. I benefit more from getting more information in this regard.

Very great insight,educative and informative. Please give meet deep critics on many research data of public international Law like human rights, environment, natural resources, law of the sea etc

In a book I read a distinction is made between null, research, and alternative hypothesis. As far as I understand, alternative and research hypotheses are the same. Can you please elaborate? Best Afshin

This is a self explanatory, easy going site. I will recommend this to my friends and colleagues.

Very good definition. How can I cite your definition in my thesis? Thank you. Is nul hypothesis compulsory in a research?

It’s a counter-proposal to be proven as a rejection

Please what is the difference between alternate hypothesis and research hypothesis?

It is a very good explanation. However, it limits hypotheses to statistically tasteable ideas. What about for qualitative researches or other researches that involve quantitative data that don’t need statistical tests?

In qualitative research, one typically uses propositions, not hypotheses.

could you please elaborate it more

I’ve benefited greatly from these notes, thank you.

This is very helpful

well articulated ideas are presented here, thank you for being reliable sources of information

Excellent. Thanks for being clear and sound about the research methodology and hypothesis (quantitative research)

I have only a simple question regarding the null hypothesis. – Is the null hypothesis (Ho) known as the reversible hypothesis of the alternative hypothesis (H1? – How to test it in academic research?

this is very important note help me much more

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and objectives are confirmatory in nature. For example,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

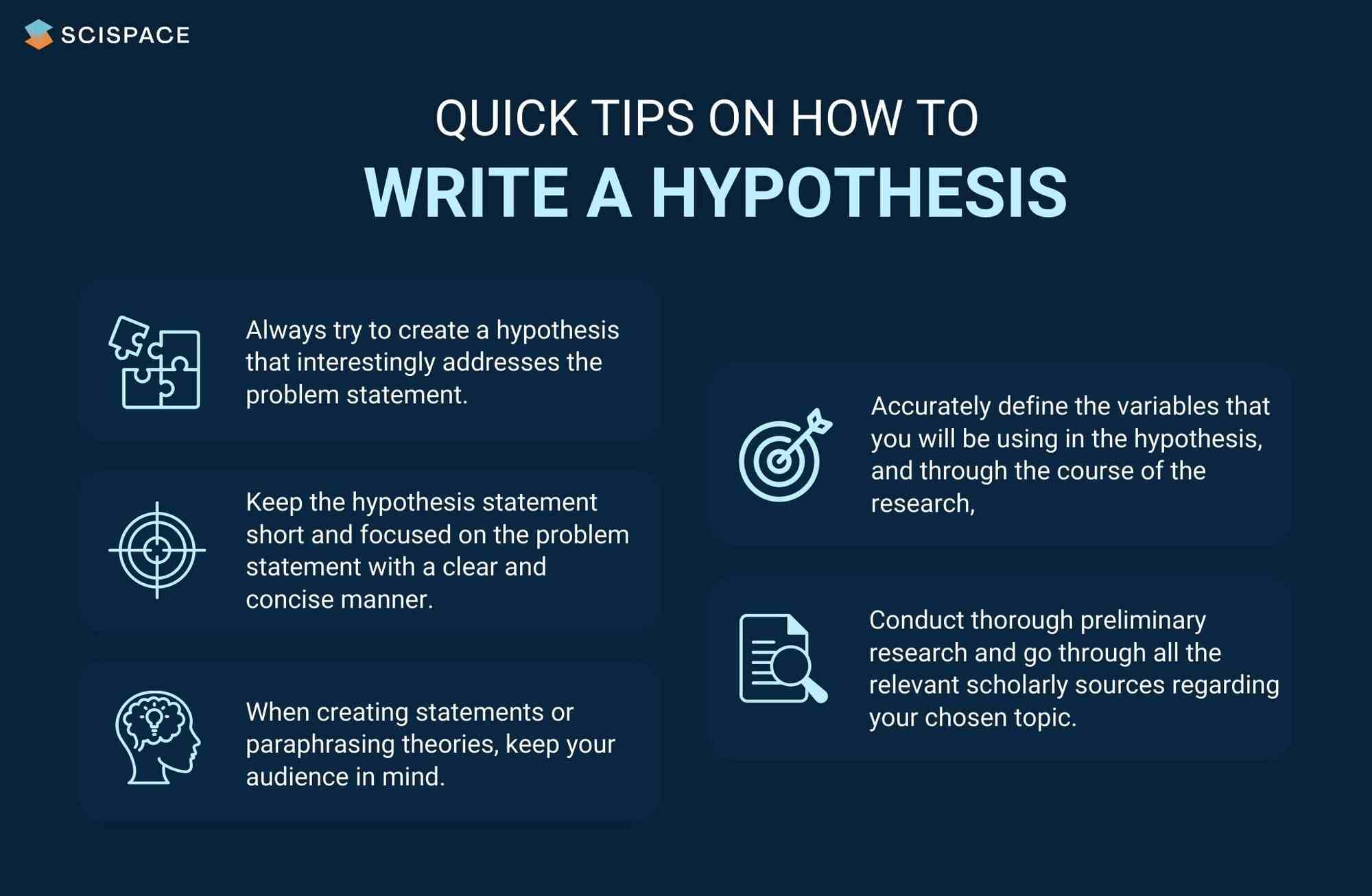

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

Published on May 6, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection .

Example: Hypothesis

Daily apple consumption leads to fewer doctor’s visits.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more types of variables .

- An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls.

- A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

If there are any control variables , extraneous variables , or confounding variables , be sure to jot those down as you go to minimize the chances that research bias will affect your results.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Step 1. Ask a question

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2. Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to ensure that you’re embarking on a relevant topic . This can also help you identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalize more complex constructs.

Step 3. Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

4. Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

5. Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if…then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis . The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

- H 0 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has no effect on their final exam scores.

- H 1 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has a positive effect on their final exam scores.

| Research question | Hypothesis | Null hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| What are the health benefits of eating an apple a day? | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will result in decreasing frequency of doctor’s visits. | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will have no effect on frequency of doctor’s visits. |

| Which airlines have the most delays? | Low-cost airlines are more likely to have delays than premium airlines. | Low-cost and premium airlines are equally likely to have delays. |

| Can flexible work arrangements improve job satisfaction? | Employees who have flexible working hours will report greater job satisfaction than employees who work fixed hours. | There is no relationship between working hour flexibility and job satisfaction. |

| How effective is high school sex education at reducing teen pregnancies? | Teenagers who received sex education lessons throughout high school will have lower rates of unplanned pregnancy teenagers who did not receive any sex education. | High school sex education has no effect on teen pregnancy rates. |

| What effect does daily use of social media have on the attention span of under-16s? | There is a negative between time spent on social media and attention span in under-16s. | There is no relationship between social media use and attention span in under-16s. |

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

A hypothesis is not just a guess — it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 7, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/hypothesis/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, operationalization | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is your plagiarism score.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Introduction to Statistical Hypothesis Testing in Nursing Research

Affiliation.

- 1 Courtney Keeler is an associate professor and Alexa Colgrove Curtis is assistant dean of graduate nursing and director of the MPH-DNP dual degree program, both at the University of San Francisco School of Nursing and Health Professions. Contact author: Courtney Keeler, [email protected] . Bernadette Capili, PhD, NP-C, is the column coordinator: [email protected] . This manuscript was supported in part by grant No. UL1TR001866 from the National Institutes of Health's National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program. The authors have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

- PMID: 37345783

- DOI: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000944936.37768.29

Editor's note: This is the 16th article in a series on clinical research by nurses. The series is designed to be used as a resource for nurses to understand the concepts and principles essential to research. Each column will present the concepts that underpin evidence-based practice-from research design to data interpretation. To see all the articles in the series, go to https://links.lww.com/AJN/A204.

Copyright © 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Descriptive and Inferential Statistics in Nursing Research. Keeler C, Curtis AC. Keeler C, et al. Am J Nurs. 2024 Jan 1;124(1):48-52. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0001004944.46230.42. Am J Nurs. 2024. PMID: 38126835

- An Introduction to Implementing and Conducting the Study. Capili B, Anastasi JK. Capili B, et al. Am J Nurs. 2024 May 1;124(5):58-61. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0001016388.26001.50. Epub 2024 Apr 25. Am J Nurs. 2024. PMID: 38661704

- Sample Size Planning in Quantitative Nursing Research. Curtis AC, Keeler C. Curtis AC, et al. Am J Nurs. 2023 Nov 1;123(11):42-46. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000995360.84994.3b. Am J Nurs. 2023. PMID: 37882402

- How Does Research Start? Capili B. Capili B. Am J Nurs. 2020 Oct;120(10):41-44. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000718644.96765.b3. Am J Nurs. 2020. PMID: 32976154 Free PMC article. Review.

- Interpretation and use of statistics in nursing research. Giuliano KK, Polanowicz M. Giuliano KK, et al. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2008 Apr-Jun;19(2):211-22. doi: 10.1097/01.AACN.0000318124.33889.6e. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2008. PMID: 18560290 Review.

- Kessler RC, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(2):184–9.

- Woolridge JM. Fundamentals of mathematical statistics. In: Introductory econometrics: a modern approach . 3rd ed. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning; 2006.

- Gerstman BB. Chapter 9. Basics of hypothesis testing. In: Basic biostatistics: statistics for public health practice . 2nd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2015.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Wolters Kluwer

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

The Research Hypothesis: Role and Construction

- First Online: 01 January 2012

Cite this chapter

- Phyllis G. Supino EdD 3

6034 Accesses

A hypothesis is a logical construct, interposed between a problem and its solution, which represents a proposed answer to a research question. It gives direction to the investigator’s thinking about the problem and, therefore, facilitates a solution. There are three primary modes of inference by which hypotheses are developed: deduction (reasoning from a general propositions to specific instances), induction (reasoning from specific instances to a general proposition), and abduction (formulation/acceptance on probation of a hypothesis to explain a surprising observation).

A research hypothesis should reflect an inference about variables; be stated as a grammatically complete, declarative sentence; be expressed simply and unambiguously; provide an adequate answer to the research problem; and be testable. Hypotheses can be classified as conceptual versus operational, single versus bi- or multivariable, causal or not causal, mechanistic versus nonmechanistic, and null or alternative. Hypotheses most commonly entail statements about “variables” which, in turn, can be classified according to their level of measurement (scaling characteristics) or according to their role in the hypothesis (independent, dependent, moderator, control, or intervening).

A hypothesis is rendered operational when its broadly (conceptually) stated variables are replaced by operational definitions of those variables. Hypotheses stated in this manner are called operational hypotheses, specific hypotheses, or predictions and facilitate testing.

Wrong hypotheses, rightly worked from, have produced more results than unguided observation

—Augustus De Morgan, 1872[ 1 ]—

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

De Morgan A, De Morgan S. A budget of paradoxes. London: Longmans Green; 1872.

Google Scholar

Leedy Paul D. Practical research. Planning and design. 2nd ed. New York: Macmillan; 1960.

Bernard C. Introduction to the study of experimental medicine. New York: Dover; 1957.

Erren TC. The quest for questions—on the logical force of science. Med Hypotheses. 2004;62:635–40.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Peirce CS. Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vol. 7. In: Hartshorne C, Weiss P, editors. Boston: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1966.

Aristotle. The complete works of Aristotle: the revised Oxford Translation. In: Barnes J, editor. vol. 2. Princeton/New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1984.

Polit D, Beck CT. Conceptualizing a study to generate evidence for nursing. In: Polit D, Beck CT, editors. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008. Chapter 4.

Jenicek M, Hitchcock DL. Evidence-based practice. Logic and critical thinking in medicine. Chicago: AMA Press; 2005.

Bacon F. The novum organon or a true guide to the interpretation of nature. A new translation by the Rev G.W. Kitchin. Oxford: The University Press; 1855.

Popper KR. Objective knowledge: an evolutionary approach (revised edition). New York: Oxford University Press; 1979.

Morgan AJ, Parker S. Translational mini-review series on vaccines: the Edward Jenner Museum and the history of vaccination. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:389–94.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Pead PJ. Benjamin Jesty: new light in the dawn of vaccination. Lancet. 2003;362:2104–9.

Lee JA. The scientific endeavor: a primer on scientific principles and practice. San Francisco: Addison-Wesley Longman; 2000.

Allchin D. Lawson’s shoehorn, or should the philosophy of science be rated, ‘X’? Science and Education. 2003;12:315–29.

Article Google Scholar

Lawson AE. What is the role of induction and deduction in reasoning and scientific inquiry? J Res Sci Teach. 2005;42:716–40.

Peirce CS. Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vol. 2. In: Hartshorne C, Weiss P, editors. Boston: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1965.

Bonfantini MA, Proni G. To guess or not to guess? In: Eco U, Sebeok T, editors. The sign of three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1983. Chapter 5.

Peirce CS. Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vol. 5. In: Hartshorne C, Weiss P, editors. Boston: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1965.

Flach PA, Kakas AC. Abductive and inductive reasoning: background issues. In: Flach PA, Kakas AC, editors. Abduction and induction. Essays on their relation and integration. The Netherlands: Klewer; 2000. Chapter 1.

Murray JF. Voltaire, Walpole and Pasteur: variations on the theme of discovery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:423–6.

Danemark B, Ekstrom M, Jakobsen L, Karlsson JC. Methodological implications, generalization, scientific inference, models (Part II) In: explaining society. Critical realism in the social sciences. New York: Routledge; 2002.

Pasteur L. Inaugural lecture as professor and dean of the faculty of sciences. In: Peterson H, editor. A treasury of the world’s greatest speeches. Douai, France: University of Lille 7 Dec 1954.

Swineburne R. Simplicity as evidence for truth. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press; 1997.

Sakar S, editor. Logical empiricism at its peak: Schlick, Carnap and Neurath. New York: Garland; 1996.

Popper K. The logic of scientific discovery. New York: Basic Books; 1959. 1934, trans. 1959.

Caws P. The philosophy of science. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand Company; 1965.

Popper K. Conjectures and refutations. The growth of scientific knowledge. 4th ed. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul; 1972.

Feyerabend PK. Against method, outline of an anarchistic theory of knowledge. London, UK: Verso; 1978.

Smith PG. Popper: conjectures and refutations (Chapter IV). In: Theory and reality: an introduction to the philosophy of science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2003.

Blystone RV, Blodgett K. WWW: the scientific method. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2006;5:7–11.

Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H. Epidemiological research. Principles and quantitative methods. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1982.

Fortune AE, Reid WJ. Research in social work. 3rd ed. New York: Columbia University Press; 1999.

Kerlinger FN. Foundations of behavioral research. 1st ed. New York: Hold, Reinhart and Winston; 1970.

Hoskins CN, Mariano C. Research in nursing and health. Understanding and using quantitative and qualitative methods. New York: Springer; 2004.

Tuckman BW. Conducting educational research. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich; 1972.

Wang C, Chiari PC, Weihrauch D, Krolikowski JG, Warltier DC, Kersten JR, Pratt Jr PF, Pagel PS. Gender-specificity of delayed preconditioning by isoflurane in rabbits: potential role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:274–80.

Beyer ME, Slesak G, Nerz S, Kazmaier S, Hoffmeister HM. Effects of endothelin-1 and IRL 1620 on myocardial contractility and myocardial energy metabolism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;26(Suppl 3):S150–2.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Stone J, Sharpe M. Amnesia for childhood in patients with unexplained neurological symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:416–7.

Naughton BJ, Moran M, Ghaly Y, Michalakes C. Computer tomography scanning and delirium in elder patients. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:1107–10.

Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337:867–72.

Stern JM, Simes RJ. Publication bias: evidence of delayed publication in a cohort study of clinical research projects. BMJ. 1997;315:640–5.

Stevens SS. On the theory of scales and measurement. Science. 1946;103:677–80.

Knapp TR. Treating ordinal scales as interval scales: an attempt to resolve the controversy. Nurs Res. 1990;39:121–3.

The Cochrane Collaboration. Open Learning Material. www.cochrane-net.org/openlearning/html/mod14-3.htm . Accessed 12 Oct 2009.

MacCorquodale K, Meehl PE. On a distinction between hypothetical constructs and intervening variables. Psychol Rev. 1948;55:95–107.

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82.

Williamson GM, Schultz R. Activity restriction mediates the association between pain and depressed affect: a study of younger and older adult cancer patients. Psychol Aging. 1995;10:369–78.

Song M, Lee EO. Development of a functional capacity model for the elderly. Res Nurs Health. 1998;21:189–98.

MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Routledge; 2008.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, 450 Clarkson Avenue, 1199, Brooklyn, NY, 11203, USA

Phyllis G. Supino EdD

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Phyllis G. Supino EdD .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

, Cardiovascular Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Clarkson Avenue, box 1199 450, Brooklyn, 11203, USA

Phyllis G. Supino

, Cardiovascualr Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Clarkson Avenue 450, Brooklyn, 11203, USA

Jeffrey S. Borer

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Supino, P.G. (2012). The Research Hypothesis: Role and Construction. In: Supino, P., Borer, J. (eds) Principles of Research Methodology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3360-6_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3360-6_3

Published : 18 April 2012

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4614-3359-0

Online ISBN : 978-1-4614-3360-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Research in Nursing Practice

Yates, Morgan BScN, RN

Morgan Yates works as an RN in the ED of Surrey Memorial Hospital, Surrey, British Columbia, Canada. Contact author: [email protected] . The author has disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Bridging the gap between clinicians and the studies they depend on.

Research provides the foundation for high-quality, evidence-based nursing care. However, there isn't a direct flow of knowledge from research into practice. When I ask nurses where the “evidence” to guide the development of “evidence-based care” comes from, I get an interesting array of answers, from “researchers” to blank stares, as if there's no connection between the worlds of researchers and bedside nurses.

If research evidence informs our nursing practice, why doesn't it come from all of us? Nurses are inquisitive, think critically about their patients’ care, and want to know the best treatments for their patients—all of which makes them perfectly suited for research. Though the majority of nurses don't have the training to conduct research projects without assistance, they know how to ask questions and they know which questions need answering.

Yet research is often perceived as something undertaken by others far removed from the front lines of nursing practice. I believe that many nurses’ notions about who does or doesn't do research are rooted in our identity as nurses, which often manifests in a belief that “good” nurses are not researchers but instead have excellent clinical skills and can manage any crisis on a unit. A 2007 study by Woodward and colleagues in the Journal of Research in Nursing found that nurse clinicians engaged in research often perceive a lack of support from nurse managers and resentment from colleagues who see the research as taking them away from clinical practice.

The distinction often drawn between nursing research and clinical practice is mirrored in the inconsistent translation of research evidence into practice. Despite widespread promotion of evidence-based practice in nursing, creation of new translational research roles for nurses in major medical centers, and Medicare reimbursement policies in the United States tied to implementation of specific evidence-supported practices, studies continue to suggest much room for improvement. In a September 2014 article in this journal, Yoder and colleagues noted that researchers have consistently found that “nurses who valued research were more likely to use research findings in practice.” Such observations suggest a need for a much stronger link between nurse clinicians and the development of research into best practices. Though this has been discussed for years, I do not yet see research as having infiltrated fundamental views of what constitutes “nursing work.”

My discussions with frontline nurses and nurses involved in research have led me to ask three key questions that need addressing before we can fully integrate research into our professional identity. These are:

- How can nurses strive for high-quality research without focusing on randomized controlled trials?

- What are the barriers to and challenges of being involved in research and how can we address these?

- How can nurses at varying education levels be involved in research?

Nurses could turn many quality improvement (QI) projects into research. Research may be viewed as a continuum, with formal projects at one end and QI projects somewhere along the continuum. Though nurses may not think that QI projects would be of interest to others, with increased understanding of the research process and greater institutional support, some QI projects could easily become research projects.

More bedside nurses are likely to engage in research if

- nursing education is strengthened.

- time away from direct care is allocated for conducting research activities.

- consultant resources such as methodologists and biostatisticians are available to staff.

- institutional and organizational support of research are strengthened.

Many nurses are intimidated by research, but change is possible if we stop seeing research as someone else's job and start making it a part of who we are and what we do. This will pave the way to evidence-based practice truly becoming the norm.

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Evidence-based practice: step by step: the seven steps of evidence-based..., ce: addressing implicit bias in nursing: a review, nursing theory in hospital models of care, ce: a review of the revised sepsis care bundles, early, nurse-directed sepsis care.

- Physician Physician Board Reviews Physician Associate Board Reviews CME Lifetime CME Free CME MATE and DEA Compliance

- Student USMLE Step 1 USMLE Step 2 USMLE Step 3 COMLEX Level 1 COMLEX Level 2 COMLEX Level 3 96 Medical School Exams Student Resource Center NCLEX - RN NCLEX - LPN/LVN/PN 24 Nursing Exams

- Nurse Practitioner APRN/NP Board Reviews CNS Certification Reviews CE - Nurse Practitioner FREE CE

- Nurse RN Certification Reviews CE - Nurse FREE CE

- Pharmacist Pharmacy Board Exam Prep CE - Pharmacist

- Allied Allied Health Exam Prep Dentist Exams CE - Social Worker CE - Dentist

- Point of Care

- Free CME/CE

Hypothesis Testing, P Values, Confidence Intervals, and Significance

Definition/introduction.

Medical providers often rely on evidence-based medicine to guide decision-making in practice. Often a research hypothesis is tested with results provided, typically with p values, confidence intervals, or both. Additionally, statistical or research significance is estimated or determined by the investigators. Unfortunately, healthcare providers may have different comfort levels in interpreting these findings, which may affect the adequate application of the data.

Issues of Concern

Register for free and read the full article, learn more about a subscription to statpearls point-of-care.

Without a foundational understanding of hypothesis testing, p values, confidence intervals, and the difference between statistical and clinical significance, it may affect healthcare providers' ability to make clinical decisions without relying purely on the research investigators deemed level of significance. Therefore, an overview of these concepts is provided to allow medical professionals to use their expertise to determine if results are reported sufficiently and if the study outcomes are clinically appropriate to be applied in healthcare practice.

Hypothesis Testing

Investigators conducting studies need research questions and hypotheses to guide analyses. Starting with broad research questions (RQs), investigators then identify a gap in current clinical practice or research. Any research problem or statement is grounded in a better understanding of relationships between two or more variables. For this article, we will use the following research question example:

Research Question: Is Drug 23 an effective treatment for Disease A?

Research questions do not directly imply specific guesses or predictions; we must formulate research hypotheses. A hypothesis is a predetermined declaration regarding the research question in which the investigator(s) makes a precise, educated guess about a study outcome. This is sometimes called the alternative hypothesis and ultimately allows the researcher to take a stance based on experience or insight from medical literature. An example of a hypothesis is below.

Research Hypothesis: Drug 23 will significantly reduce symptoms associated with Disease A compared to Drug 22.

The null hypothesis states that there is no statistical difference between groups based on the stated research hypothesis.

Researchers should be aware of journal recommendations when considering how to report p values, and manuscripts should remain internally consistent.

Regarding p values, as the number of individuals enrolled in a study (the sample size) increases, the likelihood of finding a statistically significant effect increases. With very large sample sizes, the p-value can be very low significant differences in the reduction of symptoms for Disease A between Drug 23 and Drug 22. The null hypothesis is deemed true until a study presents significant data to support rejecting the null hypothesis. Based on the results, the investigators will either reject the null hypothesis (if they found significant differences or associations) or fail to reject the null hypothesis (they could not provide proof that there were significant differences or associations).

To test a hypothesis, researchers obtain data on a representative sample to determine whether to reject or fail to reject a null hypothesis. In most research studies, it is not feasible to obtain data for an entire population. Using a sampling procedure allows for statistical inference, though this involves a certain possibility of error. [1] When determining whether to reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis, mistakes can be made: Type I and Type II errors. Though it is impossible to ensure that these errors have not occurred, researchers should limit the possibilities of these faults. [2]

Significance

Significance is a term to describe the substantive importance of medical research. Statistical significance is the likelihood of results due to chance. [3] Healthcare providers should always delineate statistical significance from clinical significance, a common error when reviewing biomedical research. [4] When conceptualizing findings reported as either significant or not significant, healthcare providers should not simply accept researchers' results or conclusions without considering the clinical significance. Healthcare professionals should consider the clinical importance of findings and understand both p values and confidence intervals so they do not have to rely on the researchers to determine the level of significance. [5] One criterion often used to determine statistical significance is the utilization of p values.

P values are used in research to determine whether the sample estimate is significantly different from a hypothesized value. The p-value is the probability that the observed effect within the study would have occurred by chance if, in reality, there was no true effect. Conventionally, data yielding a p<0.05 or p<0.01 is considered statistically significant. While some have debated that the 0.05 level should be lowered, it is still universally practiced. [6] Hypothesis testing allows us to determine the size of the effect.

An example of findings reported with p values are below:

Statement: Drug 23 reduced patients' symptoms compared to Drug 22. Patients who received Drug 23 (n=100) were 2.1 times less likely than patients who received Drug 22 (n = 100) to experience symptoms of Disease A, p<0.05.

Statement:Individuals who were prescribed Drug 23 experienced fewer symptoms (M = 1.3, SD = 0.7) compared to individuals who were prescribed Drug 22 (M = 5.3, SD = 1.9). This finding was statistically significant, p= 0.02.

For either statement, if the threshold had been set at 0.05, the null hypothesis (that there was no relationship) should be rejected, and we should conclude significant differences. Noticeably, as can be seen in the two statements above, some researchers will report findings with < or > and others will provide an exact p-value (0.000001) but never zero [6] . When examining research, readers should understand how p values are reported. The best practice is to report all p values for all variables within a study design, rather than only providing p values for variables with significant findings. [7] The inclusion of all p values provides evidence for study validity and limits suspicion for selective reporting/data mining.

While researchers have historically used p values, experts who find p values problematic encourage the use of confidence intervals. [8] . P-values alone do not allow us to understand the size or the extent of the differences or associations. [3] In March 2016, the American Statistical Association (ASA) released a statement on p values, noting that scientific decision-making and conclusions should not be based on a fixed p-value threshold (e.g., 0.05). They recommend focusing on the significance of results in the context of study design, quality of measurements, and validity of data. Ultimately, the ASA statement noted that in isolation, a p-value does not provide strong evidence. [9]

When conceptualizing clinical work, healthcare professionals should consider p values with a concurrent appraisal study design validity. For example, a p-value from a double-blinded randomized clinical trial (designed to minimize bias) should be weighted higher than one from a retrospective observational study [7] . The p-value debate has smoldered since the 1950s [10] , and replacement with confidence intervals has been suggested since the 1980s. [11]

Confidence Intervals

A confidence interval provides a range of values within given confidence (e.g., 95%), including the accurate value of the statistical constraint within a targeted population. [12] Most research uses a 95% CI, but investigators can set any level (e.g., 90% CI, 99% CI). [13] A CI provides a range with the lower bound and upper bound limits of a difference or association that would be plausible for a population. [14] Therefore, a CI of 95% indicates that if a study were to be carried out 100 times, the range would contain the true value in 95, [15] confidence intervals provide more evidence regarding the precision of an estimate compared to p-values. [6]

In consideration of the similar research example provided above, one could make the following statement with 95% CI:

Statement: Individuals who were prescribed Drug 23 had no symptoms after three days, which was significantly faster than those prescribed Drug 22; there was a mean difference between the two groups of days to the recovery of 4.2 days (95% CI: 1.9 – 7.8).

It is important to note that the width of the CI is affected by the standard error and the sample size; reducing a study sample number will result in less precision of the CI (increase the width). [14] A larger width indicates a smaller sample size or a larger variability. [16] A researcher would want to increase the precision of the CI. For example, a 95% CI of 1.43 – 1.47 is much more precise than the one provided in the example above. In research and clinical practice, CIs provide valuable information on whether the interval includes or excludes any clinically significant values. [14]

Null values are sometimes used for differences with CI (zero for differential comparisons and 1 for ratios). However, CIs provide more information than that. [15] Consider this example: A hospital implements a new protocol that reduced wait time for patients in the emergency department by an average of 25 minutes (95% CI: -2.5 – 41 minutes). Because the range crosses zero, implementing this protocol in different populations could result in longer wait times; however, the range is much higher on the positive side. Thus, while the p-value used to detect statistical significance for this may result in "not significant" findings, individuals should examine this range, consider the study design, and weigh whether or not it is still worth piloting in their workplace.