- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

27 Poverty and Crime

Patrick Sharkey, Associate Professor of Sociology, New York University.

Max Besbris, PhD Student in Sociology, New York University.

Michael Friedson, Postdoctoral Fellow, New York University.

- Published: 05 April 2017

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article examines theory and evidence on the association between poverty and crime at both the individual and community levels. It begins with a review of the literature on individual- or family-level poverty and crime, followed by a discussion at the level of the neighborhood or community. The research under consideration focuses on criminal activity and violent behavior, using self-reports or official records of violent offenses (homicide, assault, rape), property crime (burglary, theft, vandalism), and in some cases delinquency or victimization. The article concludes by highlighting three shifts of thinking about the relationship between poverty and crime, including a shift away from a focus on individual motivations and toward a focus on situations that make crime more or less likely.

The relationship between poverty and crime is complex. There is substantial evidence indicating that poverty is associated with criminal activity, but it is less clear that this relationship is causal or that higher levels of poverty in a neighborhood, a city, or a nation necessarily translate into higher levels of crime. Perhaps the most powerful illustration of this empirical reality comes from the simple observation made by Lawrence Cohen and Marcus Felson several decades ago in introducing their “routine activities theory” of crime. During the 1960s, when poverty and racial inequality were declining in American cities, the crime rate was rising ( Cohen and Felson 1979 ). The experience during the economic downturn from 2008–2012 provides a more recent example. Despite the rise in poverty and sustained unemployment over these years, crime has not risen in any remarkable way. The implication is that in order to understand the relationship between poverty and crime it is necessary to move beyond the assumption that more poor people translates directly into more crime.

One of the major shifts in criminological thinking, spurred in large part by Cohen and Felson’s ideas, is an expansion of focus beyond the characteristics or the motivations of potential offenders and toward a broader view of what makes an incident of crime more or less likely. This entails a shift from a focus on who is likely to commit a crime toward a focus on when, where, and why a crime is likely to occur ( Birkbeck and LaFree 1993 ; Katz 1988 ; Wikström and Loeber 2000 ). The basic insight of routine activities theory is that the likelihood of a crime occurring depends on the presence of a motivated offender, a vulnerable victim, and the absence of a capable guardian ( Sampson and Wikström 2008 ). Whereas traditional approaches to understanding crime focus primarily on the first element of this equation, the offender, these approaches ignore the two other moving parts: the vulnerable victim, and the presence or absence of capable guardians ( Wikström et al. 2012 ).

The “situational” perspective on crime has important implications for understanding the complexities of the relationship between poverty and crime. It forces one to consider how poverty affects the motivations of offenders, how poverty affects the vulnerability and attractiveness of potential targets, and how poverty affects the presence of capable guardians. We will consider each of these issues throughout the chapter. The research that we review reinforces the point that crime cannot be understood primarily in terms of individual characteristics, incentives, or resources. It has to be understood in terms of situations, attachments, networks, and contexts. This insight is central to a wide range of research in the field, and it frames our approach to considering the relationship between poverty and crime.

In this chapter we review theory and evidence on the relationship between poverty and crime at the level of the individual and at the level of the community. We make no attempt to be comprehensive, but instead we focus on major patterns of findings in the literature and important theoretical and empirical advances and developments. The research that we review considers criminal activity and violent behavior, using self-reports or official records of violent offenses (homicide, assault, rape), property crime (burglary, theft, vandalism), and in some cases delinquency or victimization. This approach, which reflects the dominant focus of research in criminology and sociology, places less emphasis on (or ignores completely) other types of less visible, underreported or understudied criminal activity or deviant behavior, including crime or abuse committed by police or elected officials, domestic violence, crimes committed in prison, and many types of financial or “white-collar” crime. It is important to acknowledge that the disproportionate focus on what might be thought of as “street crime” is likely to lead to biased conclusions about the overall strength of the relationship between poverty and crime. This bias arises due to the dearth of research on crime occurring outside of low-income communities (most notably white-collar crime) and because of the use of official records to measure criminal activity. Official reports of arrests reflect some combination of criminal activity, enforcement, and reporting. These are potential sources of bias that are present in much of the criminological literature and thus are present in this review as well.

The chapter proceeds with a review of the literature on individual- or family-level poverty and crime. Although the literature demonstrates a consistent association between poverty and crime, there are multiple interpretations of this association that have been put forth in the literature. Poverty may lead directly to some types of criminal activity. However, the link between poverty and crime also may be spurious, or it may be mediated by other processes related to labor force attachment, family structure, or connections to institutions like the military or the labor market. We then move to the level of the neighborhood or community. Again, the literature shows a consistent positive association between community-level poverty and crime, although the functional form of this relationship is less settled. A prominent strand of research has argued that community-level social processes play a central role in mediating the association between poverty and crime, generating resurgent interest in the importance of social cohesion, informal social control, and other dimensions of community organization that help explain the link between poverty and crime.

Our review of the literature concludes by highlighting three shifts of thinking about the relationship between poverty and crime: (1) a shift away from the idea that criminal activity is located within the individual, and toward a perspective that locates the potential for criminal activity within networks of potential offenders, victims, and guardians; (2) a shift away from a focus on individual motivations and toward a focus on situations that make crime more or less likely; and (3) a shift away from a focus on aggregated deprivation as an explanation for concentrations of crime and toward a consideration of community social processes that make crime more or less likely.

Individual Poverty and Crime

Evidence for a positive association between individual or family poverty and criminal offending is generally strong. A review of 273 studies assessing the association between different dimensions of social and economic status (SES) and offending concludes that there is consistent evidence from multiple national settings that individuals with low income, occupational status, and education have higher rates of criminal offending ( Ellis and McDonald 2001 ). However, evidence based on self-reported data on delinquent behavior is less consistent ( Tittle and Meier 1990 ; Wright et al. 1999 ). A recent study based on comparable surveys conducted in Greece, Russia, and Ukraine showed no consistent association between social and economic status and various self-reported measures of delinquent or criminal behavior ( Antonaccio et al. 2010 ).

Given this conflicting evidence, it is important to clarify that the claims made in this section are based primarily on research that examines poverty or economic resources and that considers criminal offending as an outcome. Evidence for an association between economic resources and crime is more consistent across settings and is generally quite strong, particularly in the United States ( Bjerk 2007 ). As a whole, however, the studies reviewed do not appear to provide strong evidence that these relationships are causal, nor is the overall association between poverty and crime particularly surprising—this association is consistent with virtually all individual- and family-level theories of criminal behavior. Poverty is associated with self-control and cognitive skills ( Hirschi and Gottfredson 2001 ), with family structure and joblessness ( Matsueda and Heimer 1987 ; Sampson 1987 ), with children’s peer networks ( Haynie 2001 ; Haynie, Silver, and Teasdale 2006 ), and with the type of neighborhoods in which families reside and the types of schools that children attend ( Deming 2011 ; Wilson 1987 ). The association between individual poverty and criminal offending may reflect some combination of all of these pathways of influence.

Alternatively, poverty may have direct effects on crime if the inability to secure steady or sufficient financial resources leads individuals to turn to illicit activity to generate income or if relative poverty in the midst of a wealthy society generates psychological strain ( Merton 1938 ). The “economic model of crime,” put forth formally by economist Gary Becker (1974) and elaborated and refined by an array of criminologists ( Clarke and Felson 1993 ; Cornish and Clarke 1986 ; Piliavin et al. 1986 ), suggests that crime can be explained as the product of a rational decision-making process in which potential offenders weigh the benefits and probable costs/risks of committing a crime or otherwise becoming involved in criminal activities ( Becker 1974 ). Much of the research assessing the economic model of crime has focused on deterrence, or the question of whether raising the costs of criminal behavior reduces crime. However, the theory also has direct implications for the study of poverty and crime, as it suggests that individuals lacking economic resources should have greater incentives to commit crime. Despite the abundance of evidence for an association between economic resources and criminal offending, there is little convincing research demonstrating a direct causal effect. For instance, the experimental programs that are most frequently cited for evidence on the effect of income on various social outcomes—such as the income maintenance experiments of the 1970s or the state-level welfare reform experiments of the 1990s—did not assess impacts on crime ( Blank 2002 ; Munnell 1987 ).

There are, however, a small number of studies that provide persuasive, if not definitive, evidence supporting a direct causal relationship between individual economic resources and crime. One example is a recent study that exploits differences in cities’ public assistance payment schedules in order to assess whether crime rises at periods of the month when public assistance benefits are likely to be depleted. As predicted by the economic model, crimes that lead to economic gain tend to rise as the time since public assistance payments grows, while other types of crime not involving economic gain do not increase ( Foley 2011 ). Another example comes from a set of experimental studies in which returning offenders from Georgia and Texas were randomly assigned to receive different levels of unemployment benefits immediately upon leaving prison, while members of the control group received job-placement counseling but no cash benefits ( Berk, Lenihan, and Rossi 1980 ; see also Rossi, Berk, and Lenihan 1980 ). Although the results are generalizable only to returning offenders, they show that modest supplements of income reduce subsequent recidivism.

A larger base of evidence suggests that unemployment (and underemployment or low wages) is causally related to criminal offending, with a stronger relationship between unemployment and property crime as compared with violent crime ( Chiricos 1987 ; Fagan and Freeman 1999 ; Grogger 1998 ; Levitt 2001 ; Raphael and Winter-Ebmer 2001 ). This finding from the quantitative literature finds support in ethnographic studies arguing that the absence of stable employment and income are important factors leading to participation in informal and illicit profit-seeking activity, ranging from drug distribution and burglary to participating in informal or underground economic markets ( Bourgois 1995 ; Venkatesh 2006 ; Wright and Decker 1994 ).

The evidence linking unemployment with criminal behavior can be interpreted in multiple ways. Economists studying this relationship tend to view criminal activity as a substitute for employment in the formal labor market. From this perspective, individuals who cannot find work or whose wages are low, relative to opportunities in the informal or illicit labor market, are likely to choose criminal activity as an alternative (or supplemental) source of income ( Fagan and Freeman 1999 ; Grogger 1998 ). Criminological and sociological perspectives acknowledge the importance of income as a mechanism underlying the relationship between joblessness and crime but view employment as one of many social bonds that connect individuals to other individuals and to institutions in ways that reduce the likelihood that they will become involved in criminal activity. In their life-course model of deviance and desistance, Robert Sampson and John Laub describe the set of attachments that individuals form at different stages in the life course, including college attendance, military service, and entrance into marriage ( Sampson and Laub 1993 , 1996; Laub and Sampson 2003 ). The formation and maintenance of individuals’ bonds to romantic partners and family, to employers and institutions, and the informal social controls that arise from these social bonds do not only reduce the probability of criminal activity but also help explain patterns of desistance over time. Marriage and employment, for example, can alter the offending trajectory of individuals by serving as turning points from the past to the present, by increasing supervision and responsibilities, and by transforming roles and identities ( Laub and Sampson 2003 ).

The implication is that the relationship between poverty and crime may not be direct and causal; it is plausible that this relationship may be indirect or even spurious. Unemployment is only one characteristic that may confound the relationship between poverty and crime, but there are many others. Growing up in a single-parent household or in a community dominated by single-parent households is strongly related to criminal activity and also is associated with poverty ( Sampson 1987 ; Sampson and Wilson 1995 ). Association with delinquent peers is another potential confounder, as are cognitive skills, work ethic, and exposure to environmental toxins like lead or environmental stressors like violence ( Anderson 1999 ; Matsueda 1982 , 1988 ; Nevin 2007 ; Reyes 2007 ; Stretesky and Lynch 2001 ).

This discussion leaves us with three possible models of the relationship between individual or family poverty and crime. The first model posits that this relationship is direct and causal. In this model, which is reflected in the economic model of crime, poverty and the inability to secure stable and well-paid employment in the formal labor market provide greater incentives for individuals to commit crimes in order to generate income and associated benefits. The second model posits that the relationship between poverty and crime is mediated by other processes, such as the formation of social attachments to romantic partners, jobs, or institutions like the military. The third model posits that the association between poverty and crime is spurious and is the result of bias due to confounding factors. This model would suggest that poverty is linked with crime because it is associated with other criminogenic characteristics of the family or the individual.

The evidence available provides the strongest support for the first two models. Poverty is likely to be linked to crime both because the poor have greater incentives to commit crime and because poverty affects individuals’ environments, their relationships, their developmental trajectories, and their opportunities as they move through different stages of the life course. The strongest evidence in support of this conclusion comes from the literature on unemployment, wages, and crime. However, there is very little convincing evidence that focuses purely on the direct effect of poverty on crime. We consider this to be an important gap in the literature.

Community Poverty and Crime

Despite the myriad ways that individual poverty may be linked with individual criminal activity, the aggregation of individuals who have greater incentives or propensity to commit crime does not necessarily lead to more crime in the aggregate. One simplistic illustration of why this is the case emerges when we return to the situational framework of offenders, victims, and guardians with which we began the chapter. Focusing in particular on the presence of attractive and vulnerable victims, one might conclude that in areas where poverty is concentrated there are likely to be fewer attractive victims vulnerable to potential offenders ( Hannon 2002 ). If one were to consider only the second dimension of the crime equation, one might arrive at the hypothesis that in periods where poverty is rising or in places where poverty is concentrated there should be fewer crimes committed. Just as with theories that focus only on the prevalence of motivated offenders, this hypothesis is simplistic and incomplete.

Theories that focus exclusively on the number of potential offenders or the number of potential victims within a community are equally deficient because they do not consider the ecological context in which criminal activity takes place. Moving beyond the individual-level analysis of crime requires a consideration of social organization within the community; the enforcement of common norms of behavior by community residents, leaders, and police; the structure and strength of social networks within a community; and the relationships between residents, local organizations, and institutions within and outside the community ( Sampson 2012 ; Sampson and Wikström 2008 ).

An illustrative example comes from the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) program, a social experiment that randomly offered vouchers to public housing residents in five cities that allowed them to move to low-poverty neighborhoods. The most common reason that families gave for volunteering for the program was that they wanted their children to be able to avoid the risks from crime, violence, and drugs in their origin neighborhoods ( Kling, Liebman, and Katz 2007 ). However, when data on criminal activity were analyzed years later, the results showed that youth in families who had moved to neighborhoods with lower poverty were no less likely to report having been victimized or “jumped,” seeing someone shot or stabbed, or taking part in violent activities themselves ( Kling, Liebman, and Katz 2007 ; Kling, Ludwig, and Katz 2005 ). A complicated set of findings emerged, with very different patterns for girls and boys. Whereas girls reported feeling more safe in their new communities, boys in families that moved to low-poverty neighborhoods were less likely to have been arrested for violent crimes but more likely to be arrested for property crimes, to have a friend who used drugs, and to engage in risky behaviors themselves ( Clampet-Lundquist et al. 2006 ; see also Sharkey and Sampson 2010 ).

The results from Moving to Opportunity reveal the complex ways in which individuals and aspects of their social environments interact to make crime more or less likely. Boys in families that moved to new environments may have changed their behavior with new opportunities for property crime available to them, but they may also have been subject to greater scrutiny from their new neighbors and from law enforcement. Girls in the same families were likely to be seen in a different light by neighbors and police, leading to different behavioral and social responses ( Clampet-Lundquist et al. 2006 ). The interaction between the characteristics of youths themselves; the types of potential targets that existed in their new communities; and the level of supervision, suspicion, and policing in the new communities created an unexpected pattern of behavior within the new environment.

This example highlights the complexity of community-level models of poverty and crime. In an attempt to synthesize some of the core ideas that have been put forth in the criminological literature on community-level crime, we focus on three stylized facts that guide our discussion of the community-level relationship between poverty and crime. First, crime is clustered in space to a remarkable degree ( Sampson 2012 ). This empirical observation has been made repeatedly by scholars in different settings and in different times, but the study of space and crime has been refined considerably in recent years. Crime is not only spatially clustered at the level of the neighborhood or community, but it is concentrated in a smaller number of “hot spots” within communities ( Block and Block 1995 ; Sherman 1995 ; Sherman, Gartin, and Buerger 1989 ). The spatial dimension of crime leads to questions about the underlying mechanisms that might explain why certain spaces or areas appear to be criminogenic. Over the past few decades, the concentration of poverty has emerged as a primary explanatory mechanism.

This leads to our second stylized fact: the level of poverty in a community is strongly associated with the level of crime in the community ( Patterson 1991 ; Krivo and Peterson 1996 ). This relationship is found not only in the United States but also in nations such as the Netherlands and Sweden, where the levels of concentrated poverty and violent crime are substantially lower (e.g., Sampson and Wikström 2008 ; Weijters, Scheepers, and Gerris 2009 ). Despite the robustness of this relationship across contexts, there is conflicting evidence on the functional form of this relationship. One of the central arguments in William Julius Wilson’s classic book The Truly Disadvantaged (1987) was that urban poverty in the United States transformed in the post–civil rights period, and the new type of concentrated neighborhood poverty that emerged during this period led to the intensification of an array of social problems including a sharp rise in violent crime. Sampson and Wilson (1995) argue that areas of concentrated poverty provide a niche where role models for youth are absent and residents are less fervent in enforcing common norms of behavior, leading to elevated levels of crime. This argument has served as a primary explanation for the rise and concentration of urban crime from the 1960s through the 1990s, but it has been challenged recently by research investigating the form of the relationship between neighborhood poverty and crime. Analyzing data on neighborhood crime from 25 cities in 2000, Hipp and Yates (2011) find no evidence that crime rises sharply in extreme-poverty neighborhoods. All types of crime rise with the level of poverty in the neighborhood, but for most types this relationship levels off as the neighborhood poverty rate reaches 30 percent or higher. As the most rigorous study conducted to date on the form of the relationship between neighborhood poverty and crime, we believe the findings from this article should provoke further theoretical and empirical investigations into this important issue.

Discussions about the functional form of the relationship between community poverty and crime lead directly into a broader discussion about the mechanisms underlying this relationship. An extensive ethnographic literature demonstrates how the threat of violence can come to structure interpersonal interactions and outlooks in areas of extreme poverty, creating the need for individuals to take strategic steps to avoid violence ( Anderson 1999 ; Harding 2010 ). The emergence of patterned responses to community-level poverty and violence involving the adoption of unique frames and repertoires of action becomes visible in this research, with consequences that can affect individual behavior and reinforce the atmosphere of threat, further weakening informal social controls and trust within the community ( Anderson 1999 ; Small, Harding, and Lamont 2010 ).

The importance of community trust, social cohesion, and informal social controls has been theorized and analyzed in a resurgent literature on community social processes and crime and violence. The third stylized fact about communities and crime is that social processes at the level of the community appear to play a central role in mediating the association between poverty and crime. In their classic work on the organization of communities and rates of juvenile delinquency, Shaw and McKay (1942) argued that community organization is lower and crime and delinquency are higher in neighborhoods with low social and economic status, high levels of ethnic heterogeneity, and high levels of residential mobility. In the last few decades these ideas have served as the basis for a resurgent interest in the role that structural characteristics of communities play in facilitating informal social controls, in strengthening or weakening community organization, and in increasing or reducing crime ( Sampson and Groves 1989 ; Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls 1997 ).

The research of Robert Sampson and several colleagues lies at the heart of this resurgence. With the concept of collective efficacy, Sampson builds on the ideas of Shaw and McKay but puts forth a more refined theory of the role of community-level social processes in influencing patterns of crime and violence. In addition to the three dimensions of communities on which Shaw and McKay focused, this research analyzes the importance of family structure and rates of family disruption as central factors influencing the capacity of a community to supervise and monitor teenage peer groups and to establish intergenerational lines of communication, social cohesion, and informal social controls. The “social process turn” ( Sampson, Morenoff, and Gannon-Rowley 2002 ) in research on neighborhoods and crime leads to a new understanding of the link between neighborhood poverty and crime. According to this perspective, neighborhood poverty is associated with criminal activity not because of the aggregation of motivated offenders, but rather because of community-level dynamics that create an environment in which informal social controls over activity in public space are weakened. Community-level poverty is linked with family structure, residential mobility, the density of housing, labor force detachment, physical disorder, legal cynicism, civic and political participation, and community organization, all of which are associated with crime ( Hagan and Peterson 1995 ; Krivo and Peterson 1996 ; Sampson 2012 ; Sampson and Lauritsen 1994 ).

Comparative research is beginning to assess whether the focus on community social processes is applicable in different national settings. Some research using the same methods developed to study collective efficacy in Chicago suggests that the basic relationships are similar in very different places. For instance, in comparable studies conducted in Chicago and Stockholm, neighborhood collective efficacy was found to have a remarkably similar, inverse association with violent crime ( Sampson and Wikström 2008 ). However, such similarities do not suggest that models of poverty, collective efficacy, and community violence can be blindly transferred across national contexts. In a study of Belo Horizonte, Brazil, Villarreal and Silva (2006) find that neighborhood social cohesion is not predictive of crime rates. In a context in which national policies have led to a retrenchment of public sector employment and the welfare state ( Portes and Hoffman 2003 ), the authors argue that informal networks of reciprocity and exchange are central to community sustainability but also have led to a proliferation of informal labor market activity and have emerged at a time of rising crime and violence. This study provides an example of how the relationships among neighborhood social cohesion, neighborhood poverty, and crime may vary across different local or national contexts.

Summary of the Evidence and Three Shifts of Thinking

The evidence we have reviewed suggests a set of core findings that characterize the relationship between poverty and crime at the level of the individual and the community. First, poverty is strongly associated with crime at both levels of analysis. In the rational choice, or economic model, of crime, the individual-level relationship between poverty and criminal behavior is assumed to be direct and causal, but most theoretical models do not make this assumption. We have uncovered very little empirical research that provides convincing evidence for a direct causal relationship between individual poverty and criminal activity. Some suggestive research is consistent with a causal relationship, but most research does not assess it directly. Instead, most theoretical and empirical evidence suggest that poverty is linked with criminal behavior through individual characteristics and conditions associated with poverty, such as joblessness, family structure, peer networks, psychological strain, or exposure to intensely violent environments.

At the level of the community, there is again a strong relationship between poverty and aggregated rates of crime. However, the most prominent theoretical and empirical work on the topic suggests that this relationship is mediated by community-level social processes that facilitate social cohesion and trust and that act to limit criminal activity in the community. Poverty is thus viewed as one of several characteristics of communities that lead to the breakdown of community organization, in turn leading to higher rates of crime.

These findings lead us to identify three interrelated shifts of thinking that are central to understanding the relationship between poverty and crime. These shifts of thinking reflect the insights of criminologists that have been developed over the past several decades, but they may be less familiar to poverty researchers. The first is a shift away from thinking of the potential for crime as lying within the individual offender and instead thinking of the potential for crime as lying within networks of potential offenders, victims, and guardians situated within a diverse group of contexts and settings ( Papachristos 2011 ; Wikström et al. 2012 ). The field of criminology has a long history of locating the source of criminal activity within the individual. Without denying the importance of individual characteristics in affecting the propensity for criminal activity, and without denying the agency of individual offenders, we argue that the traditionally dominant focus on the offender has stifled progress in understanding variation in crime across places and over time.

This point reflects a second shift of thinking, which involves moving from a focus on individual motivations to a focus on situations ( Wikström et al. 2012 ). Applied to the study of poverty and crime, this shift moves away from the idea that crime is driven primarily by economic calculations. While economic benefit is one important motivation for potential offenders, even the rational choice paradigm has been extended to consider other types of noneconomic rewards arising from criminal offending (e.g., Cornish and Clarke 1986 ). The situational approach to crime, by contrast, expands beyond the motivations of individuals to consider the interactions of offenders, victims, and guardians. The role of poverty as a predictor of criminal offending is much more complex in the situational approach to crime. Poverty may produce more motivated offenders, fewer potential victims (for at least some types of crime), and less effective community guardians. Considered together, one would still expect an association between poverty and crime, but the mechanisms underlying this association are more complex than the economic model suggests.

The third shift of thinking moves beyond a focus on aggregated deprivation as an explanation for concentrations of crime and toward a consideration of community social processes ( Sampson, Morenoff, and Gannon-Rowley 2002 ). Concentrated poverty is one of several characteristics of communities, along with others such as high levels of residential mobility, that tend to disrupt processes of informal social control and social cohesion within communities, or collective efficacy ( Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls 1997 ). The breakdown of collective efficacy provides the context for the emergence of crime and violence within the community, as informal controls over public space are less effective and violations of collective norms of behavior become common.

These three shifts of thinking reflect the findings from a complex theoretical and empirical literature on the relationship between poverty and crime. In the most simplistic model of this relationship, individual poverty causes individuals to commit more crime and the aggregation of poor individuals in a community, a city, or a nation translates directly into more crime. The experience of the United States over the last 50 years demonstrates that this model is not adequate. When poverty is high, crime does not necessarily rise with it. In critiquing the direct, linear, causal model of poverty and crime, we acknowledge that we do not have an equally simple model to replace it. Instead, we argue that the relationship is complex, that it is driven by a number of different mediating mechanisms, and that these mechanisms vary depending on the level of analysis (e.g., individuals, neighborhoods, nations, etc.). While this may not be a particularly satisfying conclusion, the evidence available suggests that it is the most realistic.

Anderson, Elijah . 1999 . Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City . New York: W. W. Norton.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Antonaccio, Olena , Charles R. Tittle , Ekaterina Botchkovar , and Maria Kranidiotis . 2010 . “ The Correlates of Crime and Deviance: Additional Evidence. ” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 47(3):297–328.

Becker, Gary S. 1974 . “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach.” Pp. 1–54 in Essays in the Economics of Crime and Punishment edited by Gary S. Becker and William M. Landes . Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Berk, Richard A. , Kenneth J. Lenihan and Peter H. Rossi . 1980 . “ Crime and Poverty: Some Experimental Evidence from Ex-Offenders. ” American Sociological Review 45(5):766–86.

Birkbeck, Christopher and Gary LaFree . 1993 . “ The Situational Analysis of Crime and Deviance. ” Annual Review of Sociology 19:113–37.

Bjerk, David . 2007 . “ Measuring the Relationship between Youth Criminal Participation and Household Economic Resources. ” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 23(1):23–39.

Blank, Rebecca M. 2002 . “ Evaluating Welfare Reform in the United States. ” Journal of Economic Literature 40(4):1105–66.

Block, Richard and Carolyn R. Block . 1995 . “Space, Place and Crime: Hot Spot Areas and Hot Places of Liquor-Related Crime.” Pp. 145–83 in Crime and Place , edited by J. E. Eck and D. Weisburd (Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 4). Washington, DC: Criminal Justice Press.

Bourgois, Philippe . 1995 . In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chiricos, Theodore G. 1987 . “ Rates of Crime and Unemployment: An Analysis of Aggregate Research Evidence. ” Social Problems 34(2):187–212.

Clampet-Lundquist, Susan , Kathryn Edin , Jeffrey R. Kling , and Greg J. Duncan . 2006 . “ Moving At-Risk Teenagers Out of High-Risk Neighborhoods: Why Girls Fare Better Than Boys. ” Working paper No. 509. Princeton, NJ: Industrial Relations Section, Princeton University.

Clarke, Ronald V. and Marcus Felson . 1993 . Routine Activity and Rational Choice: Advances in Criminological Theory . New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Cohen, Lawrence E. and Marcus Felson . 1979 . “ Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach. ” American Sociological Review 44(4):588–608.

Cornish, Derek B. and Ronald V. Clarke . 1986 . The Reasoning Criminal: Rational Choice Perspectives on Offending . Secaucus, NJ: Springer-Verlag.

Deming, David J. 2011 . “ Better Schools, Less Crime? ” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126:2063–2115.

Ellis, Lee and James N. McDonald . 2001 . “ Crime, Delinquency, and Social Status: A Reconsideration. ” Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 32(3):23–52.

Fagan, Jeffrey and Richard B. Freeman . 1999 . “ Crime and Work. ” Crime and Justice 25:225–90.

Foley, Fritz . 2011 . “ Welfare Payments and Crime. ” Review of Economics and Statistics 93(1):97–112.

Grogger, Jeff . 1998 . “ Market Wages and Youth Crime. ” Journal of Labor Economics 16(4):756–91.

Hagan, John and Ruth D. Peterson . 1995 . “Criminal Inequality in America: Patterns and Consequences.” Pp. 14–36 in Crime and Inequality , edited by John Hagan and Ruth D. Peterson . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Hannon, Lance . 2002 . “ Criminal Opportunity Theory and the Relationship between Poverty and Property Crime. ” Sociological Spectrum 22:363–81.

Harding, David J. 2010 . Living the Drama: Community, Conflict, and Culture among Inner-City Boys . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Haynie, Dana L. 2001 . “ Delinquent Peers Revisited: Does Network Structure Matter? ” American Journal of Sociology 106(4):1013–57.

Haynie, Dana L. , Eric Silver , and Brent Teasdale . 2006 . “ Neighborhood Characteristics, Peer Networks, and Adolescent Violence. ” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 22(2):147–69.

Hipp, John and Daniel Yates . 2011 . “ Ghettos, Thresholds, and Crime: Does concentrated poverty really have an accelerating increasing effect on crime? ” Criminology 49(4):955–90.

Hirschi, Travis and Michael Gottfredson . 2001 . “Self-Control Theory.” Pp. 81–96 in Explaining Criminals and Crime: Essays in Contemporary Criminological Theory , edited by Raymond Pasternoster and Ronet Bachman . Cary: Roxbury.

Katz, Jack . 1988 . The Seductions of Crime: Moral and Sensual Attractions in Doing Evil . New York: Basic Books.

Kling, Jefrey , Jeffrey Liebman , and Lawrence Katz . 2007 . “ Experimental Analysis of Neighborhood Effects. ” Econometrica 75(1):83–119.

Kling, J. R. , J. Ludwig , and L. Katz . 2005 . “ Neighborhood Effects on Crime for Female and Male Youth: Evidence from a Randomized Housing Voucher Experiment. ” Quarterly Journal of Economics 120(1):87–130.

Krivo, Lauren J. and Ruth D. Peterson . 1996 . “ Extremely Disadvantaged Neighborhoods and Urban Crime. ” Social Forces 75(2):619–48.

Laub, John H. and Robert J. Sampson . 2003 . Shared Beginnings, Divergent Lives: Delinquent Boys to Age 70. ” Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Levitt, Steven D. 2001 . “ Alternative Strategies for Identifying the Link between Unemployment and Crime. ” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 17(4):377–90.

Matsueda, Ross L. 1982 . “ Testing Control Theory and Differential Association: A Causal Modeling Approach. ” American Sociological Review 47(4):489–507.

Matsueda, Ross L. 1988 . “ The Current State of Differential Association Theory. ” Crime & Delinquency 34(3):277–306.

Matsueda, Ross L. and Karen Heimer . 1987 . “ Race, Family Structure, and Delinquency: A Test of Differential Association and Social Control Theories. ” American Sociological Review 52(6):826–40.

Merton, Robert K. 1938 . “ Social Structure and Anomie. ” American Sociological Review 3(5):672–82.

Munnell, Alicia H. 1987 . Lessons from the Income Maintenance Experiments. Boston: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Nevin, Rick . 2007 . “ Understanding International Crime Trends: The Legacy of Preschool Lead Exposure. ” Environmental Research 101(3):315–36.

Papachristos, Andrew V. 2011 . “ The Coming of a Networked Criminology? ” Advances in Criminological Theory 17:101–40.

Piliavin, Irving , Rosemary Gartner , Craig Thornton , Ross L. Matsueda . 1986 . “ Crime, Deterrence, and Rational Choice. ” American Sociological Review 51(1):101–19.

Patterson, E. Britt . 1991 . “ Poverty, Inequality, and Community Crime Rates. ” Criminology 29(4):755–76.

Portes, Alejandro and Kelly Hoffman . 2003 . “ Latin America Class Structures: Their Composition and Changes during the Neoliberal Era. ” Latin America Research Review 38:41–82.

Raphael, Steven and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer . 2001 . “ Identifying the Effect of Unemployment on Crime. ” Journal of Law and Economics 44(1):259–83.

Reyes, Jessica Wolpaw . 2007 . “ Environmental Policy as Social Policy? The Impact of Childhood Lead Exposure on Crime. ” Working Paper 13097. Cambridge, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Rossi, Peter H. , Richard A. Berk , and Kenneth J. Lenihan . 1980 . Money, Work, and Crime: Some Experimental Results . New York: Academic Press.

Sampson, Robert J. 1987 . “ Urban Black Violence: The Effect of Male Joblessness and Family Disruption. ” American Journal of Sociology 93(2):348–82.

Sampson, Robert J. 2012 . Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sampson, Robert J. and Byron Groves . 1989 . “ Community Structure and Crime: Testing Social Disorganization Theory. ” American Journal of Sociology 94(4):774–802.

Sampson, Robert J. and John H. Laub . 1993 . Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points through Life . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sampson, Robert J. and John H. Laub . 1996 . “ Socioeconomic Achievement in the Life Course of Disadvantaged Men: Military Service as a Turning Point, circa 1940–1965. ” American Sociological Review 61:347–67.

Sampson, Robert J. and Janet L. Lauritsen . 1994 . “Violent Victimization and Offending: Individual-, Situational-, and Community-level Risk Factors.” Pp. 1–114 in Understanding and Preventing Violence: Social Influences (Vol. 3), edited by Albert J. Reiss Jr. and Jeffrey Roth . (National Research Council.) Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Sampson, Robert J. , Jeffrey D. Morenoff , and Thomas Gannon-Rowley . 2002 . “ Assessing ‘Neighborhood Effects’: Social Processes and New Direction in Research. ” Annual Review of Sociology 28:443–78.

Sampson, Robert J. and Per-Olof Wikström . 2008 . “The Social Order of Violence in Chicago and Stockholm Neighborhoods: A Comparative Inquiry.” Pp. 97–119 in Order, Conflict, and Violence , edited by I. Shapiro , S. Kalyvas , and T. Masoud . New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sampson, Robert J. , Stephen W. Raudenbush , and Felton Earls . 1997 . “ Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy. ” Science 277:918–24.

Sampson, Robert J. and William Julius Wilson . 1995 . “Toward a Theory of Race, Crime, and Urban Inequality.” Pp. 37–54 in Crime and Inequality , edited by John Hagan and Ruth D. Peterson . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Sharkey, Patrick and Robert J. Sampson . 2010 . “ Destination Effects: Residential Mobility and Trajectories of Adolescent Violence in a Stratified Metropolis. ” Criminology 48:639–81.

Shaw, Clifford and Henry McKay . 1942 . Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas: A Study of Rates of Delinquency in Relation to Differential Characteristics of Local Communities in American Cities . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sherman, Lawrence W. 1995 . “Hot Spots of Crime and Criminal Careers of Places.” Pp. 35–52 in Crime and Place , edited by J. E. Eck and D. Weisburd . (Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 4). Washington, DC: Criminal Justice Press.

Sherman, Lawrence W. , Patrick R. Gartin , and Michael E. Buerger . 1989 . “Hot Spots of Predatory Crime: Routine Activities and the Criminology of Place.” Criminology 27(1):27–55.

Small, Mario , David J. Harding , and Michele Lamont . 2010 . “ Reconsidering Culture and Poverty ” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 629(1):6–27.

Stretesky, Paul B. and Michael J. Lynch . 2001 . “ The Relationship between Lead Exposure and Homicide. ” Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 155:579–82.

Tittle, Charles R. and Robert F. Meier . 1990 . “ Specifying the SES/Delinquency Relationship. ” Criminology 28:271–99.

Venkatesh, Sudhir . 2006 . Off the Books: The Underground Economy of the Urban Poor . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Villarreal, A. and B. F. Silva . 2006 . “ Social Cohesion, Criminal Victimization and Perceived Risk of Crime in Brazilian Neighborhoods. ” Social Forces 84(3):1725–53.

Weijters, Gijs , Peer Scheepers , and Jan Gerris . 2009 . “ City and/or Neighbourhood Determinants?: Studying Contextual Effects on Youth Delinquency. ” European Journal of Criminology 6(5):439–55.

Wikström, Per-Olof H. , Dietrich Oberwittler , Kyle Treiber , and Beth Hardie . 2012 . Breaking Rules: The Social and Situational Dynamics of Young People’s Urban Crime . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wikström, Per-Olof H. and Rolf Loeber . 2000 . “ Do Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Cause Well-Adjusted Children to Become Adolescent Delinquents? A Study of Male Juvenile Serious Offending, Individual Risk and Protective Factors, and Neighborhood Context. ” Criminology 38(4):1109–42.

Wilson, William J. 1987 . The Truly Disadvantaged. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wright, Richard T. and Scott H. Decker . 1994 . Burglars on the Job: Streetlife and Residential Break-Ins. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Wright, Bradley R. Entner, Avshalom Caspi , Terrie E. Moffitt , Richard A. Miech , and Phil A. Silva . 1999 . “ Reconsidering the Relationship between SES and Delinquency: Causation but Not Correlation. ” Criminology 37(1):175–94.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

The Official Journal of the Pan-Pacific Association of Input-Output Studies (PAPAIOS)

- Open access

- Published: 05 June 2020

Dynamic linkages between poverty, inequality, crime, and social expenditures in a panel of 16 countries: two-step GMM estimates

- Muhammad Khalid Anser 1 ,

- Zahid Yousaf 2 ,

- Abdelmohsen A. Nassani 3 ,

- Saad M. Alotaibi 3 ,

- Ahmad Kabbani 4 &

- Khalid Zaman 5

Journal of Economic Structures volume 9 , Article number: 43 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

155k Accesses

46 Citations

268 Altmetric

Metrics details

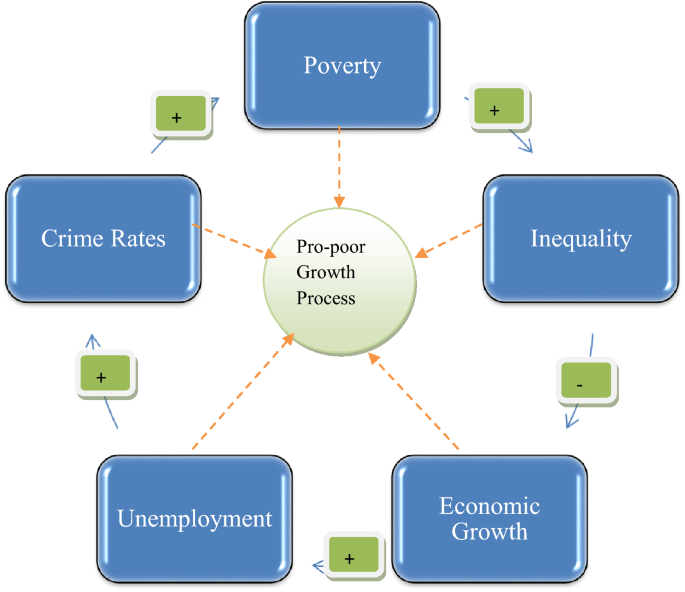

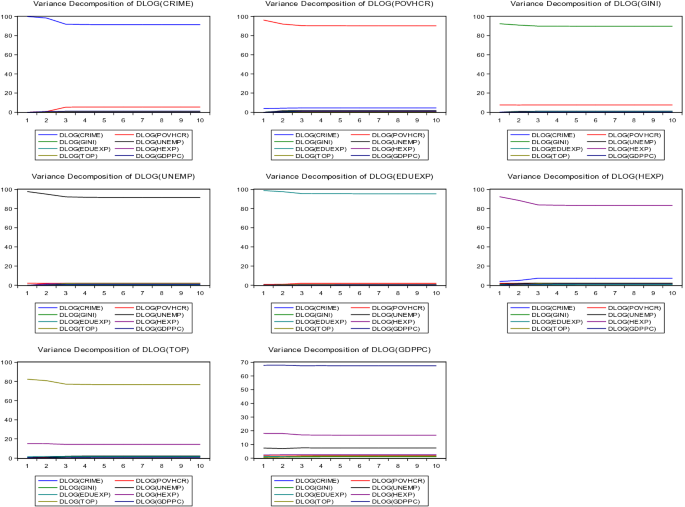

The study examines the relationship between growth–inequality–poverty (GIP) triangle and crime rate under the premises of inverted U-shaped Kuznets curve and pro-poor growth scenario in a panel of 16 diversified countries, over a period of 1990–2014. The study employed panel Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimator for robust inferences. The results show that there is (i) no/flat relationship between per capita income and crime rate; (ii) U-shaped relationship between poverty headcount and per capita income and (iii) inverted U-shaped relationship between income inequality and economic growth in a panel of selected countries. Income inequality and unemployment rate increases crime rate while trade openness supports to decrease crime rate. Crime rate substantially increases income inequality while health expenditures decrease poverty headcount ratio. Per capita income is influenced by high poverty incidence, whereas health expenditures and trade factor both amplify per capita income across countries. The results of pro-poor growth analysis show that though the crime rate decreases in the years 2000–2004 and 2010–2014, while the growth phase was anti-poor due to unequal distribution of income. Pro-poor education and health trickle down to the lower income strata group for the years 2010–2014, as education and health reforms considerably reduce crime rate during the time period.

1 Introduction

The study evaluated different United Nation sustainable development goals (SDGs), i.e., goals 1 and 2 (poverty reduction and hunger), goals 3 and 4 (promotion of health and education), goal 10 (reduced inequalities), and goal 16 (reduction of violence, peace and justice) to access pro-poor growth and crime reduction in a panel of 16 heterogeneous countries. The discussion of crime rate in pro-poor growth (PPG) agenda remains absent in the economic development literature, though Bourguignon ( 2000 ) stressed to reduce crime and violence by judicious income distribution; however, a very limited literature is available to emphasize the need of social safety nets for vulnerable peoples that should be included in the pro-growth policy agenda for broad-based economic growth. Kelly ( 2000 ) investigated the relationship between income inequality (INC_INEQ) and urban crime, and found that INC_INEQ is the strong predictor to influence violent crime rather than property crime, while poverty (POV) and economic growth (EG) significantly affect on property crime rather than violent crime. The policies should be developed for equitable income and sound EG for reducing POV and crime across the globe. Drèze and Khera ( 2000 ) examined the inter-district variations of intentional homicides rate (IHR) in India for the period of 1981 and found that there is no significant relationship between urbanization/poverty and murder rates, while literacy rate has a strong impact to reduce criminal violence in India. The results further indicate the lower murder rate in those districts where female to male ratio is comparatively high. The study emphasized the need to reduce crime, violence and homicides by significant growth policies for sustained EG in India. Neumayer ( 2003 ) investigated the long-run relationship between political governance, economic policies and IHR using the panel of 117 selected countries for the period of 1980–1997 and concluded that IHR can be reduce by good economic and political policies. The results specified that higher income level, good civic sense, sound EG, and higher level of democracy all are connected with the lower homicides rate in a panel of countries. The study emphasized the need to improve governance indicators in order to lowering the IHR across the globe. Jacobs and Richardson ( 2008 ) examined the interrelationship between INC_INEQ and IHR in a panel of 14 developed democracies nation and found that intentional homicides is the mounting concerns in those nations where the inequitable income distribution exists, while results further provoke the presence of young males associated with the higher murder rates in a region. The policies should be formulated caution with care while devising for judicious income distribution with demographic variables in the pro-growth agenda. Sachsida et al. ( 2010 ) found inertial effect on criminality and confirmed the positive relationship between INC_INEQ, urbanization and IHR. The study emphasized the importance of public security spending to reduce IHR in Brazil. Pridemore ( 2011 ) re-assessed the relationship between POV, INC_INEQ and IHR in a cross-national panel of US states and found POV-homicides’ linkages rather than inequality-homicides’ association. The study argued that there is substantially desire to re-assess the inequality-homicides’ linkages as it might be the misspecification of the model. Ulriksen ( 2012 ) examined the relationship between PPG, POV reduction and social security policies in the context of Botswana and found that broad-based social security policies have a significant impact to reduce POV, thus there is a strong need to include social security protections in the pro-poor growth (PPG) agenda for lowering the POV rates across the globe. Ouimet ( 2012 ) investigated the impact of socio-economic factors on IHR in a panel of 165 countries for the period 2010 and found that GIP triangle are strongly connected with the IHR for all countries, while for sub-samples, the results only support the inequality-homicides association rather than POV and EG induced IHR. The results highlighted the importance of GIP triangle to reduce IHR in a panel of selected countries.