- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Macroeconomics

Explaining the World Through Macroeconomic Analysis

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/0__mary_hall-5bfc262446e0fb005118b2a7.jpeg)

When the price of a product you want to buy goes up, it affects you. But why does the price go up? Is demand greater than supply? Does the cost go up because of the raw materials needed to make it? Or, is it a war in an unknown country that affects the price?

To answer these questions, we need to turn to macroeconomics. Macroeconomic analysis provides a way to understand the world through studying the economy.

Key Takeaways

- Macroeconomics is the branch of economics that studies the economy as a whole.

- Macroeconomics focuses on three things: National output, unemployment, and inflation.

- Governments can use macroeconomic policy including monetary and fiscal policy to stabilize the economy.

- Central banks use monetary policy to increase or decrease the money supply, and use fiscal policy to adjust government spending.

What Is Macroeconomics?

Macroeconomics is the study of the behavior of the economy as a whole. This is different from microeconomics, which concentrates more on individuals and how they make economic decisions. While microeconomics looks at single factors that affect individual decisions, macroeconomics studies general economic factors.

Macroeconomics is very complicated, with many factors that influence it. These factors are analyzed with various economic indicators that tell us about the overall health of the economy.

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis provides official macroeconomic statistics.

Macroeconomists try to forecast economic conditions to help consumers, firms, and governments make better decisions:

- Consumers want to know how easy it will be to find work, how much it will cost to buy goods and services in the market, or how much it may cost to borrow money.

- Businesses use macroeconomic analysis to determine whether expanding production will be welcomed by the market. Will consumers have enough money to buy the products, or will the products sit on shelves and collect dust?

- Governments turn to macroeconomics when budgeting spending, creating taxes, deciding on interest rates, and making policy decisions.

Macroeconomic analysis broadly focuses on three things—national output (measured by gross domestic product), unemployment, and inflation.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Output, the most important concept of macroeconomics, refers to the total amount of goods and services a country produces, commonly known as the gross domestic product (GDP) . This figure is like a snapshot of the economy at a certain point in time.

When referring to GDP, macroeconomists tend to use real GDP , which takes inflation into account, as opposed to nominal GDP , which reflects only changes in price. The nominal GDP figure is higher if inflation goes up from year to year, so it is not necessarily indicative of higher output levels, only of higher prices.

The drawback of GDP is that information has to be collected after a specified time period has passed. Therefore a figure for the GDP today would have to be an estimate.

GDP is nonetheless a stepping stone into macroeconomic analysis. Once a series of figures is collected over a period of time, they can be compared, and economists and investors can begin to decipher business cycles, which are made up of the periods alternating between economic recessions (slumps) and expansions (booms) that occur over time.

From there we can begin to look at the reasons why the cycles took place, which could be government policy, consumer behavior, or international phenomena, among other things. Of course, these figures can be compared across economies as well. Hence, we can determine which foreign countries are economically strong or weak.

Based on what they learn from the past, analysts can then begin to forecast the future state of the economy. It is important to remember that what determines human behavior and ultimately the economy can never be forecasted completely.

The Unemployment Rate

The unemployment rate tells macroeconomists how many people from the available pool of labor (the labor force) are unable to find work.

Macroeconomists agree when the economy witnesses growth from period to period, which is indicated in the GDP growth rate, unemployment levels tend to be low . This is because, with rising (real) GDP levels, we know the output is higher and, hence, more laborers are needed to keep up with the greater levels of production.

The third main factor macroeconomists look at is the inflation rate , or the rate at which prices rise. Inflation is primarily measured in two ways: the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the GDP deflator. The CPI gives the current price of a selected basket of goods and services that is updated periodically. The GDP deflator is the ratio of nominal GDP to real GDP.

If nominal GDP is higher than real GDP, we can assume the prices of goods and services have been rising. Both the CPI and GDP deflator tend to move in the same direction and differ by less than 1%.

Demand and Disposable Income

What ultimately determines output is demand . Demand comes from consumers, from the government, and from imports and exports.

Demand alone, however, will not determine how much is produced. What consumers demand is not necessarily what they can afford to buy, so to determine demand, a consumer's disposable income must also be measured. This is the amount of money left for spending and/or investment after taxes.

Disposable income is different from discretionary income, which is after-tax income, less payments to maintain a person's standard of living.

To calculate disposable income, a worker's wages must be quantified as well. Salary is a function of two main components: the minimum salary for which employees will work and the amount employers are willing to pay to keep the employee. Given that demand and supply go hand in hand, salary levels will suffer in times of high unemployment, and prosper when unemployment levels are low.

Demand inherently will determine supply (production levels) and an equilibrium will be reached. But in order to feed demand and supply, money is needed. A country's central bank (the Federal Reserve in the U.S.) typically puts money in circulation in the economy. The sum of all individual demand determines how much money is needed in the economy. To determine this, economists look at the nominal GDP, which measures the aggregate level of transactions, to determine a suitable level of the money supply .

What the Government Can Do

There are two ways the government implements macroeconomic policy. Both monetary and fiscal policy are tools the government uses to help stabilize a nation's economy. Below, we take a look at how each works.

Monetary Policy

A simple example of monetary policy is the central bank's open market operations . When there is a need to increase cash in the economy, the central bank will buy government bonds (monetary expansion). These securities allow the central bank to inject the economy with an immediate supply of cash. In turn, interest rates—the cost to borrow money—are reduced because the demand for the bonds will increase their price and push the interest rate down. In theory, more people and businesses will then buy and invest. Demand for goods and services will rise and, as a result, the output will increase. To cope with increased levels of production, unemployment levels should fall and wages should rise.

On the other hand, when the central bank needs to absorb extra money in the economy and push inflation levels down, it will sell its Treasury bills , or T-bills. This will result in higher interest rates, which will cause less borrowing, less spending, and less investment. It will also decrease demand, which will ultimately push down the price level (inflation) and result in less real output.

Fiscal Policy

The government can also increase taxes or lower government spending in order to conduct a fiscal contraction . This lowers real output because less government spending means less disposable income for consumers. And, when more of a consumer's wages go to taxes, demand will also decrease.

A fiscal expansion by the government would mean taxes are decreased or government spending is increased. Either way, the result will be growth in real output because the government will stir demand with increased spending. In the meantime, a consumer with more disposable income will be willing to buy more.

A government will tend to use a combination of both monetary and fiscal options when setting policies that deal with the economy.

What Are the Key Macroeconomic Indicators?

The key macroeconomic indicators are the gross domestic product, the unemployment rate, and the rate of inflation.

What Is the Purpose of Macroeconomic Analysis?

Macroeconomic analysis allows a country to monitor its economic health, develop sound policies and practices, and sustain suitable growth.

How Does the Government Influence Macroeconomics?

The two main ways a government can influence macroeconomics is through monetary policy and fiscal policy. Monetary policy helps control the flow and quantity of money in an economy while fiscal policy uses government spending and taxation to influence economic conditions.

The Bottom Line

The performance of the economy is important to all of us. We analyze the economy by primarily looking at the national output, unemployment, and inflation. Although it is consumers who ultimately determine the direction of the economy, governments also influence it through fiscal and monetary policy.

International Monetary Fund. " Macroeconomic Policy and Poverty Reduction ."

International Monetary Fund. " Monetary Policy: Stabilizing Prices and Output ."

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. " Comparing the Consumer Price Index With the Gross Domestic Product Price Index and Gross Domestic Product Implicit Price Deflator ."

Federal Reserve System. " Open Market Operations ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/RealGDP_Final_4190456-2a2ba1af9b9b49bfb59dcce76c6c5de0.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.7: Conclusion and Key Concepts

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 45751

- Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine

- Trent University & Concordia University via Lyryx

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

In this chapter we have looked at indicators of macroeconomic activity and performance, and the measurement of macroeconomic activity using the national accounts. We have not examined the conditions that determine the level of economic activity and fluctuations in that level. An economic model is required for that work. In the next chapter we introduce the framework of a basic macroeconomic model.

Key Concepts

Macroeconomics studies the whole national economy as a system. It examines expenditure decisions by households, businesses, and governments, and the total flows of goods and services produced and incomes earned.

Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) , prices and inflation rates , and employment and unemployment rates are indicators of macroeconomic activity and performance.

Fluctuations in the growth rate of real GDP, in inflation rates, and in unemployment rates are important aspects of recent economic performance in Canada.

The expenditures by households, production of goods and services by business, and the incomes that result are illustrated by the circular flow of real resources and money payments.

The National Accounts provide a framework for the measurement of the output of the economy and the incomes earned in the economy.

Nominal GDP measures the output of final goods and services at market prices in the economy, and the money incomes earned by the factors of production.

Real GDP measures the output of final goods and services produced, and incomes earned at constant prices.

The GDP deflator is a measure of the price level for all final goods and services in the economy.

Real GDP and per capita real GDP are crude measures of national and individual welfare. They ignore non-market activities, the composition of output, and the distribution of income among industries and households.

- Previous Chapter

- Next Chapter

- 1 0000000404811396 https://isni.org/isni/0000000404811396 International Monetary Fund

Two themes dominated the discussions at the seminar. How do macroeconomic policies and the environment interact? How important is it that the Fund staff become aware of this interaction and take it into account in dealing with member countries?

Sessions 1, 2, and 3 of the seminar were devoted mainly to the first theme, while Session 4 focused primarily on the second theme. The seminar opened with welcoming remarks, which provided to the participants the background of Fund work on the environment, and closed with concluding remarks, which, among other things, looked forward to establishing priorities for Fund work on the environment.

In her welcoming remarks, Margaret Kelly reminded participants that the primary mandate of the Fund is to promote international monetary cooperation and exchange rate stability and to help member countries solve their balance of payments problems. Nevertheless, should resource depletion or environmental damage in a country be so severe as to affect seriously the longer-term viability of its balance of payments, the IMF staff cannot but be involved. Kelly described how Fund staff work on the environment has so far focused on monitoring the research of other specialized institutions and developing an understanding of the links between macroeconomic policies and conditions and the environment—thereby enabling the staff to design sound macroeconomic policies.

Interrelationships Between Macroeconomics and the Environment

In dealing with links between macroeconomics and the environment, the first three sessions of the seminar reviewed the conclusions of readily available studies using alternative analytical frameworks (Session 1), the urgency and feasibility of integrating the environment into national accounts (Session 2), and case studies of the possible impact on the economy of integrating environmental objectives into macroeconomic policymaking (Session 3).

- Impact of Macroeconomics on the Environment

The Ved Gandhi and Ronald McMorran paper highlighted four conclusions that have been reached by the analyses carried out in the partial equilibrium framework. First, macroeconomic stability is a minimum and necessary condition for preserving the environment. Second, environmental degradation is generally caused by market, policy, and institutional failures relating to the use of environmental resources. Third, macroeconomic policies can have an adverse impact on the environment but only when market, policy, and institutional failures exist, although it is difficult in advance to judge how serious these impacts will be. Fourth, macroeconomic policies are inefficient and blunt instruments for mitigating environmental degradation, for which appropriate environmental policies are the most efficient and direct instruments. The authors conclude that only general equilibrium analyses, carried out with the help of computable general equilibrium (CGE) models, can help one reach country-specific conclusions on how the country’s macroeconomic policies, or their reform, are likely to affect the environment.

The Stein Hansen paper begins where the Gandhi and McMorran paper leaves off. Using examples of the research work done in Norway and in the United States, it highlights many advantages of CGE modeling, which, among other things, can help to (1) establish the loss of GDP and the reduction in its growth rate owing to environmental policies aimed at reducing CO 2 and SO 2 emissions, (2) permit policymakers see the direct and indirect consequences for the macroeconomy of alternative uses of revenues from environmental taxes, such as a CO 2 stabilizing gasoline tax, and (3) bring together policymakers (from ministries of finance and economy and the ministry of environment) for a professional and political dialogue and make them recognize the tradeoffs between pursuing alternative macroeconomic and environmental objectives. Hansen also shows (giving the examples of higher stumpage fees and raising the wage rate in Costa Rica) how sometimes general equilibrium results can be quite opposite from the partial equilibrium results. He recognizes that CGE models require lots of reliable data and assumptions, which not all countries have, and certainly most developing countries do not have.

Much like the Gandhi and McMorran conclusions, Hansen points out partial equilibrium impacts of fiscal discipline, exchange rate and trade liberalization, interest rate and credit policy reform, and external debt relief, especially in developing countries. These can be both negative and positive at the same time, depending upon environmental policies, and can in the end yield “uncertain” final outcomes. Nonetheless, he suggests that macroeconomic policies of developing countries would greatly improve the environment if the following measures were undertaken: (1) avoid reducing small and fragile environmental and health care budgets, (2) curtail fertilizer, pesticide, water, and energy subsidies, (3) restructure health budgets from capital-intensive curative hospitalization to labor-intensive preventive primary health care, (4) include land-reform and property-right measures in the reform program in order to facilitate internalizing the environmental externalities resulting from malfunctioning land markets, (5) increase taxes and lower subsidies that affect forests and other natural resources, and (6) ensure that external debt relief is not used to finance environmentally harmful projects.

Andrew Steer, in commenting on both papers, agreed with their overall conclusions that the impact of macroeconomic policy reforms on the environment is generally positive. He highlighted the four paths through which this comes about. First, macroeconomic instability promotes high discount rates and short-term calculations, guaranteeing environmental destruction through excessive natural resource exploitation and deforestation, while macroeconomic stabilization encourages environmentally sound decisions by economic agents. Second, although a curtailment of aggregate demand in theory helps the environment through less consumption, less depletion, and less waste, cuts in environmental public expenditures (as a part of a reduction in public expenditures to reduce fiscal imbalances) in certain cases may be detrimental to protecting the environment. Third, macroeconomic policy reforms affect the environment through relative price shifts. Most of these impacts, especially those which move the economy from subsidized input prices toward world prices, help improve the quality of the environment. However, as Hansen and Gandhi and McMorran point out, the impact will also depend on a number of features of the economy, especially whether or not complementary “first-best” environmental policies exist. Fourth, structural reforms relating to financial sector, accountability of state-owned enterprises, property rights, and the like, often associated with macroeconomic adjustment programs, also promote economic efficiency and reduce waste. As with relative price shifts, for structural reforms to work for sustainable development and not against it, certain preconditions must exist. As an illustration, privatization can easily become a cause for air and water pollution if environmental policies are absent or civil society is weak and lacks empowerment.

Steer also agreed with Hansen that, based on the simulations of CGE models in Norway and the United States, radical environmental policies may not greatly reduce the rate of economic growth in industrial countries. Whether or not the public is ready and willing to accept even that much reduction is another matter.

In the discussion that followed, there was support for the general equilibrium approach and CGE modeling. It was pointed out, however, that with a suitable choice of parameters one can get any result that one wants, and that these models were less useful in generating specific numbers and more useful in supplementing other tools to develop broad trends. On the whole, development of CGE models was not seen as a priority for the use of limited resources in developing countries.

Developing sectoral policies and implementing them effectively were recognized as important for the overall impact of macroeconomic policies on the environment. Given that these sectoral policies had significant feedbacks, a commentator argued that the Fund cannot absolve itself of the responsibility of taking these policies into account. However, there was also a consensus that macroeconomic policy reform was too critical to wait until sectoral policies have been properly designed or effectively implemented.

Ecotaxes were underscored as an important element of environmental policies. The scope for such taxes to replace distortionary income taxes and regressive value-added taxes was explored. Because a tax system must meet the criteria of efficiency, equity, and revenue productivity, it was felt that ecotaxes should supplement, rather than replace, existing broad-based taxes.

One participant stressed the importance of social structures to the environment and the impact of macroeconomic policies on social structures. Although it was argued that the Fund should recognize the importance of social structures in its operational work, the consensus was that because the World Bank had the necessary expertise in matters relating to social structures, the Fund should utilize the knowledge and expertise of the Bank staff in this regard.

It was emphasized that natural resources in many developing countries were exploited excessively because of a nontransparent system of rent-seeking by vested groups and that the Fund staff should therefore encourage a greater transparency in leasing of exploitation rights.

Finally, it was questioned whether strong environmental policies were compatible with an acceptable level of macroeconomic performance.

Here, the general feeling was that reasonably (but not excessively) strong environmental policies may mean some reduction in the level and growth rate of GDP, conventionally measured, but that outcome should not be considered intolerable. The Norwegian simulations, given as major evidence of this conclusion, had broad support.

- Impact of the Environment on Macroeconomy

David Pearce and Kirk Hamilton stressed the impact of pollution and environmental degradation on the macroeconomy, in the first instance through its impact on human capital. They argued and provided evidence that air pollution, caused mainly by a weak transportation policy for fuel conservation and vehicular traffic, often resulted in ill health and premature mortality. Similarly, they argued that a lack of water-treatment facilities led to contamination of water and caused many waterborne diseases.

They further argued that investments in environmental protection, which often had high rates of return and benefits even in terms of conventionally measured GNP, are often ignored in macroeconomic analysis. An example of such investments was afforestation, which could help improve soil fertility and crop yields, increase timber production and other tree products, and produce forest fodder. Such investments, of course, will also have nonmarket returns in the form of biological diversity and carbon storage.

Pearce and Hamilton then took up the issue of depletion of natural resources and degradation of the natural environment (or natural capital) which can have a significant impact on economic welfare and macroeconomy through erosion of what they call the “genuine savings rate.” They felt that the concept of “genuine savings rate,” defined as [GNP-Consumption-Depreciation of produced capital] - [value of “net” depletion of natural resources] - [marginal social cost of “net” accumulation of pollution], is the most relevant way to assess the impact of depletion of natural resources and pollution of the environment on economic welfare and the sustainability of the macroeconomy. In fact, they showed that an economy can have a positive conventionally measured savings rate, derived from conventionally measured national accounts under the system of national accounts (SNA), but a negative genuine savings rate. They emphasized that an economy will be unsustainable and economic welfare will eventually decline, if a negative genuine savings rate persists. Hence, they suggested that only those policy reforms should be implemented that will not only enhance the SNA-based savings rate but will curtail losses resulting from natural resource depletion and environmental pollution.

The authors made heroic attempts to estimate the genuine savings rates for various parts of the world. These estimates reveal that the Middle East and North Africa have negative genuine savings rates; in Latin America and the Caribbean, they have turned from positive to negative in recent years; and in most sub-Saharan African countries, they are consistently negative, holding a serious potential for the unsustainability of their economies.

Pearce and Hamilton therefore concluded with a call for revised economic accounting, for the development of better valuation techniques of nonmarketed natural and environmental resources, and for the Fund in particular to revise its savings and other macroeconomic indicators to incorporate sustainability considerations.

Kirit Parikh, who commented on the Pearce-Hamilton paper, had little difficulty with the authors’ urging that the countries should have a proper transport policy (to curb air pollution) and investments in water treatment (to improve water quality), but found three major flaws in the concept of genuine savings rate. First, in adding man-made physical capital to natural capital, the authors assume a one-to-one substitutability between the two, which is inappropriate. Second, the concept of a genuine savings rate refers strictly to the domestic economy and ignores the environmental damage done elsewhere when a country imports pollution—and natural—resource-intensive products from elsewhere. Third, the authors do not deduct the losses of global commons caused by the lifestyle of a country; as a result, the U.S. economy, for example, comes out being “sustainable” by their criteria.

In the discussion that ensued, the participants noted alternative approaches to the concern for the environment—an all-out approach of the Norwegian kind, in which environmental targets are agreed to with the NGOs and macroeconomic policies are made subject to those constraints, and an incremental approach along the Pearce-Hamilton lines, under which the negative impact of macroeconomic policies on the environment is measured through some index, like the genuine savings rate. Which approach is more suitable for the Fund staff to pursue? While not fully resolved, the latter approach appeared pragmatic and feasible at this stage, since it essentially required the Fund staff to focus on how macroeconomic adjustment was achieved and what its effect was on some index of sustainability.

One participant reminded the seminar that the Fund staff, which did medium-term balance of payments projections, did consider the longer-term sustainability of natural resources, to the extent that the impact of the exhaustion of exportable resources on the medium-term macroeconomic outlook was of serious concern to the Fund. However, environmental economists present wanted the Fund staff to go even further and start looking at the erosion of soil and other environmental resources, which may not necessarily affect the medium-term outlook of exports, but were important to the sustainability of macroeconomic performance, economic welfare, and quality of life.

Another participant reminded the seminar that the concept of sustainability was still not fully defined. What the policymakers should aim at was unclear. Was it sustainability? Over what period? Would environmental damage over the short to medium term be acceptable if it was reversible and helped countries improve their financial and economic situation in the short run, which provided resources to pay for the cost of reversing the damage in the medium to long run? The answer seemed to be yes.

A question was whether there were trade-offs between the rate of macroeconomic adjustment (macroeconomic objectives) and the rate of environmental protection (environmental objectives). Here, the answer was probably yes. However, it was not clear how far macroeconomic adjustment should be forgone in the interest of environmental protection.

- Feasibility of Environmentally Adjusted National Accounts

The Adriaan Bloem and Ethan Weisman paper, as presented by Paul Cotterell, recognized the importance of “green” and “brown” accounts for raising public awareness of environmental issues and toward an understanding of interrelationships between macroeconomy and the environment. However, of the two possible approaches—the physical approach (which would involve the measurement of physical data on natural resources and pollution) and the monetary approach (which would require monetary values associated with the physical data)—they preferred the physical approach as the first step. In their opinion, this approach abstracts from “correct” prices while the monetary approach would require valuations and estimations based upon a variety of sensitive assumptions and modeling of economic behavior.

Bloem and Weisman pointed out that the traditional measures of national accounts aggregates should not be replaced by green national accounts, but that a supplementary set of satellite accounts should be developed as recognized by the 1993 SNA. However, Bloem and Weisman also recognized that the satellite accounts were “a work-in-progress” and that further research and experience would be needed to develop fully these satellite accounts to integrate the entire financial accounts, the rest of the world account, and the balance sheets. Practical experience with this approach in the United States and the Netherlands provided adequate support for staying with this approach at this stage. Even this approach would require physical data on the environment, which were not always available and whose generation in itself would represent substantial progress.

Peter Bartelmus in emphasized his paper the significance and need for environmentally adjusted national accounts. He quoted the studies on Mexico and Papua New Guinea to show how results and conclusions on growth rates of the economy can vary significantly whether unadjusted or adjusted national accounts were used. He stressed how environmentally adjusted national accounts can facilitate modeling and creation of data relevant for policy analysis for sustainable development. Finally, he suggested that “valuation” of natural resources, notably through maintenance costing of the use of environmental assets can help in full-cost pricing and therefore in the internalization of environmental costs. But he also recognized the many problems and limitations of developing environmentally adjusted national accounts and using them to assess sustainability in growth and development. There are conceptual and statistical difficulties in defining and measuring social (human and institutional) capital. Even with respect to environmental capital, serious problems exist in relation to valuing the environmental services or estimating the depletion and depreciation of environmental assets. Bartelmus, however, felt that techniques designed to overcome data and definitional problems did exist and had been successfully applied in several country case studies.

Bartelmus also argued that integrated environmental-economic accounts can help see the sustainability of economic growth in terms of positive trends of environmentally adjusted net domestic product (EDP). The definition and measurement of a broader concept of sustainable development, on the other hand, would require supplementary physical indicators as, for instance, developed in Frameworks for Indicators of Sustainable Development.

The System of integrated Environmental and Economic Accounting (SEEA), proposed by the United Nations, is based on the revised 1993 SNA. It attempts to measure the sustainability of economic growth in terms of the costs of maintaining both produced and natural assets. Welfare-oriented approaches to national accounts would require the removal from GDP of the so-called “defensive expenditures,” needed to mitigate the effects of pollution. However, both the definition and the elimination of defensive expenditure from accounting aggregates are controversial and inconsistent with conventional economic indicators. The SEEA, therefore, identifies environmental protection expenditures as part of intermediate and final use and only by appropriate classifications.

Bartelmus concluded that the macroeconomy-environment interactions can be studied at this stage by means of “satellite” accounts, parallel to conventional national accounts, without replacing the core accounts of the SNA by environmental ones. He also described the advantages of an integrated information system such as the SEEA. In this context, he indicated a number of direct policy uses of the results of integrated accounting, notably the setting of economic instruments at maintenance cost levels (at the microeconomic level), and the use of environmentally adjusted indicators such as capital (including natural capital), capital accumulation, environmental cost of depletion and degradation, and adjusted aggregates of final consumption and trade (at the macroeconomic level). Bartelmus pleaded for international cooperation to standardize concepts and methods of environmental accounting for worldwide use and application.

Michael Ward, who commented on both papers, noted that neither Bloem and Weisman nor Bartelmus showed exuberance for a fully integrated and comprehensive environmental accounting system. The former take this position because such accounts have many intractable and systemic measurement problems with limited relevance to fiscal and monetary management and the development of overall macroeconomic strategy. The latter believes that the ultimate objective of sustainability should be sustainability of people and their welfare rather than of the economy alone. Ward recapitulated two serious difficulties with an integrated accounting framework. First, there was the issue relating to the quantities—industrial production generates environmentally degrading outputs, such as polluting effluents, wastes, and energy losses, but technological changes can convert such “dirty” residual outputs into “clean” outputs. It was unclear how one should take account of such quantities. Second, there were many issues relating to valuation and pollution. What were the “appropriate” prices, given the ill-conceived interventions by governments, income and wealth inequalities, and intergenerational factors that shape social and economic policies? How should one “price” cross-border environmental externalities? How should one deal with different “valuations” that countries at different stages of development are bound to apply to environmental damage? How to “value” a natural resource being exploited by a multinational monopoly for which competitive markets did not exist? How to know that external costs have not been internalized already into “prices”? Thus, Ward also considered integrated environmental accounting unachievable until the relevant conceptual, methodological, and statistical issues had been resolved.

Nevertheless, he advised that policy practitioners at the Fund and the World Bank can still take certain initiatives. The Fund can remain a macroeconomic organization but can ensure sustainability through an insistence on “green taxes” in its operational work, so that countries achieve a more balanced and rational pattern of progress. The World Bank, on the other hand, should ensure that, at a minimum, all countries have an adequate provision of safe water, solid waste disposal, and clean sanitation, which are the key environmental issues everywhere. The Fund staff could then ensure that government expenditures and investments in these services would be protected from cuts in public outlays following a fiscal stringency. Ward also called on the World Bank to help enhance institutional capacity for environmental protection and, as a start, assess the importance to future development of “big ticket” items of resource depletion and ecological deterioration in a dozen selected developing countries.

The discussion that followed supported the general conclusion that while it would be desirable to have environmentally integrated national accounts, for short-term macroeconomic policy formulation conventional national accounts would suffice. Only one discussant felt that conventional national accounts, especially in economies heavily dependent on natural resources, would send out wrong signals on savings, investments, and balance of payments.

There was also a general agreement, that given serious conceptual and methodological issues, the approach that the 1993 SNA has taken, of creating satellite accounts, was quite acceptable at this stage. Efforts to resolve the serious outstanding issues must nevertheless continue.

- Integrating Macroeconomics and the Environment—Industrial Country Experience

Knut Alfsen describes in his paper how Norway, a small industrial country, has attempted to integrate environmental concerns into its macroeconomic policymaking.

Historically, because natural resources have been important to the Norwegian economy (most important among all OECD countries except for Ireland) natural resource accounting (for energy, fishing, land use, sand, and gravel) was the first step the authorities took, some 20 years ago, primarily to improve long-term conservation and resource management. The accounts consisted of reserves, extraction rates, and domestic end uses, and, in the context of energy accounts, air pollution emission. However, the authorities used only energy accounts information actively (as energy was an input into production and energy output was important to the economy) and integrated this information into macroeconomic modeling.

More recently, however, the coverage of resource and environmental accounts has been broadened. In addition, environmental assets and environmental degradation have been linked to the economic productivity of capital and labor; as a result, the macroeconomic model used in policy formulation has become more versatile. It now contains energy use and associated emissions of nine polluting compounds, generation of various types of wastes, physical effects of air pollution and waste generation, and economic valuation of environmental degradation based on shadow prices of capital and labor. Alfsen pointed out the many questions the authorities have sought to answer with the help of the integrated model. These have included determining the costs in GDP terms (net of indirect gains to the GDP) of meeting targets set in international treaties and protocols and comparing costs in GDP terms associated with meeting environmental targets (i.e., increase in pollution) with those that would accrue if no environmental targets were set. Alfsen admits, however, that the Norwegian model depends heavily on many assumptions and ignores the links between employment and the environment.

Alfsen describes how the model has been used in Norway to identify the economic and environmental effects of introduction of carbon taxes, the decline in emissions (or emission elasticity) when fuel and electricity prices are raised, and the costs to specific sectors of the economy of specific environmental policies.

According to Alfsen, important policy conclusions have been derived from such analyses. On carbon taxes : (1) These are not the most efficient means of reducing NO x emissions. (2) Since national targets of emissions and pollution are unachievable even with high carbon taxes, other measures need to be taken as well. (3) Secondary economic effects of introducing carbon taxes are highly uncertain. (4) Loss of GDP estimates owing to carbon taxes vary with varying assumptions. On emission elasticity : (1) Elasticities depend greatly on the assumptions made. (2) Transport activities have the greatest impact on pollution and the greatest sensitivity for emissions. (3) Energy and capital are complementary inputs and taxation of sulphur emissions reduces long-term economic growth. As to the impact on individual sectors , taxation is found to be the most cost-effective means in Norway for lowering emissions from polluting sectors.

In analyzing why Norway has been successful in integrating environmental concerns into macroeconomic policy formulation, Alfsen could provide only a tentative answer: because of economic, political, and institutional factors. The main economic factor is the importance of natural resources to the society and how they are managed. The main political factor is that organized political groups, including the NGOs, that depend on government funds have supported politicians responding to their needs and objectives. The long experience of Statistics Norway, first with natural resource accounting and later with modeling integrated national accounts for policy formulation purposes, has encouraged dialogue between relevant institutions and actors in the debate. In addition, the Ministry of Finance has come to see environmental taxes as a way of expanding the tax base. These are the peculiar institutional factors. Alfsen is not sure if the Norwegian experience with integrating environmental considerations into macroeconomic policymaking can be replicated in other countries, but he believes that, if properly carried out, it can help break the power of vested interest groups.

Peter Clark, commenting on the Alfsen paper, drew from the Norwegian experience four lessons that he thought could be useful to other industrial countries. First, a model-based integration of environmental and macroeconomic policies facilitates consensus building by resolving differences in opinions and preconceived notions. Second, it places environmental concerns at the center of macroeconomic policymaking. Third, it helps analyze the feasibility of applying major environment policy shocks to the economy. Fourth, it helps identify both direct and indirect effects and nets them out.

Clark also had a few specific questions on Alfsen’s paper: Are there any alternatives to carbon taxes if they are considered inefficient means of reducing NO x ? By assuming that technology is exogenous, thereby denying technological progress, and by assuming that an energy tax is basically a tax on capital, does the model exaggerate the output losses owing to CO 2 taxes? How serious are the employment effects of environmental policies, such as the carbon tax? While Clark agreed that the production of power through hydroelectricity results in little pollution, it does make the country vulnerable to shocks in world prices of oil, which is the alternative form of fuel for energy production. Have the authorities paid attention to these consequences? All in all, Clark believed that that country’s experience held the prospects of wider applicability.

Alfsen’s paper generated much enthusiastic discussion among participants and raised several questions. Must conventional GDP losses result from environmental policies and can they be offset? What are the economic and distributional consequences of carbon taxes and other green taxes? How does the Norwegian CGE model integrate natural resources into the macroeconomy? Are integrated national accounts appropriate for international comparability? Has the monopoly in modeling by Statistics Norway in any way been hazardous, and has it done any damage to policymaking in Norway?

In his reply, Alfsen agreed that there are bound to be, and have been in Norway’s case, some costs to the economy of environmental policies and nobody can foresee whether technological changes will help to reduce these costs. In fact, nobody can foresee the nature and direction of technological change over time. Environmental policies, including eco-taxes, need not have crushing effects on economies, if their revenues are utilized wisely. The distributional consequences of such taxes and policies, however, may not be positive, especially in developing countries where income and wealth distribution is already heavily skewed.

Alfsen agreed that modeling oil and gas is not easy and, in the Norwegian CGE model, the natural resources are largely treated exogenously. He also agreed that integrated national accounts are necessary for international comparability, but not necessarily for the conduct of a domestic policy dialogue. As to the final question, Norway does have a Model Forum, where the shortcomings of various models are continuously discussed, so that the model of Statistics Norway is used after a consensus has been reached. In fact, it is because of the CGE model that the preconceived notion of the NGOs, that all economic growth is bad for the environment, has been corrected.

In connection with environmental taxes, a discussant made the point that, in addition to being supportive of environmental objectives, such taxes can provide finances for reducing the distortionary taxes on labor and capital and can help improve economic efficiency and prospects for economic growth. Environmental taxes were therefore seen as a true win-win policy for the environment as well as the macroeconomy.

- Integrating Macroeconomics and the Environment—Developing Countries

Few developing countries have integrated their environmental objectives and policies with their macroeconomic objectives and policies; many still do not have clear-cut objectives and strategies for environmental protection. Therefore, little is known by way of experience. The country case studies carried out in the World Bank, however, throw much light on what would happen in developing countries if macroeconomics and the environment were integrated.

Mohan Munasinghe and Wilfrido Cruz summarized the main conclusions of recent World Bank case studies. These conclusions are in line with those in the Gandhi and McMorran paper, but the World Bank authors provide abundant evidence for their conclusions. For example, exchange rate reform is seen to be helpful to the environment by correcting the prices of tradables, encouraging wildlife protection and discouraging cattle ranching (in Zimbabwe and Zambia), providing incentives to protect nature preserves and game parks (in Tanzania), and helping expand the forests, and reduce land degradation and losses from floods (in Vietnam).

Pricing and subsidy reform in relation to electricity is shown to have a favorable impact on the environment because of energy conservation and improvements in air quality resulting from a reduction of electricity subsidies (in Sri Lanka) and rangeland improvement resulting from the reduction of livestock subsidies (in Tunisia). Reduction of price distortions and corrections of price signals are shown by the authors as creating significant benefits for the macroeconomy as well as for the environment.

High and unstable interest rates are shown to be detrimental to farm productivity over the longer run (in Brazil), while low and stable interest rates have had a welcome positive influence in curtailing the rate of logging (in Costa Rica).

The case studies also reveal how the beneficial effects of macroeconomic policy changes would have been much greater if complementary environmental policies had been in place. Munasinghe and Cruz emphasize that while the overall benefits of trade liberalization were positive—by promoting exports and encouraging industrialization—they were eroded in certain countries because the relative price changes brought about changes in the structure of production that had undesired side effects on the environment and that were not corrected by appropriate environmental policies. For example, trade liberalization promoted a water-intensive crop, such as sugarcane (in Morocco), that should have been discouraged by raising water charges. It encouraged a surge of (dirty) processing industries (in Indonesia) that could have been curbed by pollution regulations. It encouraged pressure on land resources and increased encroachment on marginal land as well as soil erosion (in Ghana) that could have been constrained by establishing property rights. The case studies of Mexico, Poland, and Thailand were mentioned as evidence of the extreme importance of building institutional capacity in developing countries that would help authorities foresee the undesired effects of macroeconomic reform and adopt appropriate corrective environmental measures.

Basing their arguments on the case studies, Munasinghe and Cruz point to the potential of fiscal cutbacks to damage the environment. Cutbacks in environmental expenditures, though insignificant to begin with, were shown to be environmentally unfriendly (in Thailand, Mexico, Cameroon, Zambia, and Tanzania) while cutbacks in the purchasing power, coupled with population growth, led to deforestation and cultivation of marginal lands (in the Philippines and Cameroon and certain other countries of sub-Saharan Africa).

The point made earlier by Hansen that partial equilibrium results can be misleading in certain circumstances is reconfirmed by Munasinghe and Cruz. In Costa Rica’s case, an increase in minimum wages was found to increase deforestation. Directly, it encouraged unskilled workers to move to cities (thus reducing deforestation), but indirectly investors found minimum wage legislation binding in the industrial sector and sought refuge in the agricultural sector (thereby increasing deforestation). The net result was increased conversion of forest land to farming.

Munasinghe and Cruz conclude from the World Bank case studies that economy-wide policies tend to have significant and important effects, but if environmental policies do not exist, there is no assurance that efficiency-oriented economic reforms will be beneficial to the environment. They believe that developing countries have substantial scope for implementing the right environmental policies and suggest a step-by-step approach to integrate the environment into macroeconomic policy formulation at the country level. Toward this, they regard the Action Impact Matrix proposed by them as a versatile analytical tool.

Cielito Habito, in commenting on the paper, agreed with Munasinghe and Cruz that the impact of macroeconomic reforms (and structural adjustment programs) was generally beneficial for the environment and that complementary environmental policies were needed to guard against or mitigate their adverse effects on the environment.

Taking the case of the Philippines, Habito illustrated how the economy-wide policies adversely affected the environment as the environmental policy framework was weak to nonexistent. There was a depletion of forest resources (and soil erosion owing to deforestation), as well as depletion of fisheries, as macroeconomic reforms turned the terms of trade against agriculture and farmers resorted to extensive farming and engaged in overfishing to make up for the loss of income. This process was facilitated by unduly low stumpage fees and liberal licensing rules. The air pollution also grew, owing to the anti-agriculture and pro-industry bias of macroeconomic reforms, as industries enjoyed excessive industrial protection provided by the Government. Water pollution became a serious problem, especially in cities, as public spending on water and sanitation facilities and garbage collection services was grossly inadequate. This pollution was exacerbated by migration from the country to the cities. In the Philippine case, Habito considers the anti-agriculture and pro-industry bias of macroeconomic reforms to be the major culprit.

But he also recognizes that the Philippines needs jobs, incomes, and industries to support her growing population, and that polluting industries may have been accepted because of their backward linkages with agriculture. Habito thus brought forth the trade-off between incomes and jobs and environmental concerns that the authorities of developing countries often face and for which the adoption of complementary environmental policies are absolutely indispensable. Once implemented, these policies have feedback effects on the economy and the prospects of economic growth that should also be taken into account.

Finally, Habito questioned the usefulness of the Action Impact Matrix proposed by Munasinghe and Cruz. Where conditions are changing rapidly and many factors and policies simultaneously affect the environment, he argued that the Matrix is bound to have an extremely limited usefulness. It will also be difficult to use it in practice owing to various constraints, including the paucity of data and analytical tools to balance the conflicting impacts.

In the discussion that followed, one discussant asked if, by stressing the importance of complementary policies, the World Bank and the Fund simply wish to treat the environmental protection as an add-on objective instead of fully integrating it into macroeconomic policy formulation. Another discussant asked Cielito Habito if it were at all possible that the staff of international organizations would ever be able to convince the authorities of developing countries to adopt politically sensitive environmental policies. Another question that was raised related to the emphasis on win-win policies resulting from subsidy reductions and price reforms. Munasinghe and Cruz were asked whether the effects of such reforms were overstated since much of the environmental damage in countries with structural adjustment programs resulted from their social impacts and effects on social structures. At least one participant argued that ignoring the social impacts of adjustment and the role of social structures in environmental damage was shortsighted on the part of the Fund and the Bank.

A participant wanted to know how feasible it was to design and implement environmental taxes in the context of developing countries. Another participant wanted to know if the World Bank had done studies on how the levels and patterns of environmental expenditures of the governments have been affected in countries undergoing severe fiscal stringency.

In response, Munasinghe argued that ensuring that desirable environmental policies will all be in place before macroeconomic reforms are implemented may not always be possible. When macroeconomic reforms cannot wait, it would seem necessary to have complementary policies, at least as add-ons, instead of completely ignoring them. As to the relevance of social structures to the environment, both Munasinghe and Cruz agreed that they were important, although they stressed that little analytical work had been done until now in the Bank as well as elsewhere that would facilitate its integration into the operational work of the Bank and the Fund.

Munasinghe gave many reasons why it is difficult to design adequate environmental taxes. It is not easy to decide who should be made to bear the tax or even determine its level. (Should it be based on the extent of damage, the level of emissions, or the size of the particulate matter that is causing the damage in the first place?) Regarding the impact of structural adjustment programs and fiscal stringency on environmental expenditures, the participants were informed that some work has been done at the World Bank. Another participant pointed out that a recent study of eight countries with structural adjustment programs in recent years showed no decline (as a proportion of GDP) in social expenditures (health and education).

Cielito Habito, responding to a question, thought that, at least in the Philippines, the authorities are now convinced of the urgent need for environmental policies to address the short-term negative impacts of macroeconomic adjustment on the environment.

One Fund staff member reminded the participants that, as a prior step, a synthesis of macroeconomic and environment objectives must take place in the member countries themselves, if the Fund staff is to design macroeconomic reform packages that would be fully supportive of the country’s environmental objectives. Most participants seemed to agree to the urgent need for a coordination of economic and environmental work at the country level itself.

- The Fund and the Environment

The last session of the seminar focused on the Fund and the environment.

Stanley Fischer, in his luncheon remarks on what is reasonable to expect of the Fund in the environment area, stated that the work of the Fund and its staff is guided by the Articles of Agreement, which discourage member countries from resorting to macroeconomic policies “destructive of national and international prosperity” and in fact encourage them to adopt macroeconomic policies which would achieve monetary and financial stability and “contribute thereby … to the development of productive resources.” He argued that although the environment is not referred to in the Articles of Agreement, excessive exploitation of natural resources and increased deforestation, which can occur particularly when appropriate environmental policies are lacking, cannot be ignored because they can give rise to structural balance of payments problems and can reduce economic growth prospects.

He indicated that the Fund’s advice on public policy reforms is generally supportive of the environment; besides, the Fund, working closely with the World Bank, helps countries prepare Policy Framework Papers, which often include plans for addressing environmental problems. The Fund has been also supporting the work on environmental or “green” accounting being carried out by the United Nations, the World Bank, and others.

Finally, environmental issues tend to show up in Fund dealings with member countries in a number of ways. Developing countries, for example, whose economic growth strategy relies heavily on depletable resources are advised to use such resources at an optimal rate. Countries whose economies are still in transition are advised to remove price distortions and subsidies (e.g., for energy) and to eliminate soft budget constraints for state-owned enterprises. Industrial countries, which may already be paying attention to environmental issues, could consider the results of analytical research on the impact of environmental policies and conditions on the macroeconomy and incorporate them in policy formulation.

David Pearce, who initiated the panel discussion on the subject, was of the view that the Fund staff must take the environment into account because it makes little sense to revitalize the economy or bring about macroeconomic stability if it is at the expense of the resource base of the economy on which economic growth ultimately depends. Macro-economic stability without care for the environment will not be sustainable, and, in his opinion, the Articles of Agreement of the Fund do invite the staff to be concerned with sustainability. He argued that the fear that environment was a complex and multifaceted subject for which the Fund economists were not adequately trained was unfounded because the staff of the World Bank and the World Trade Organization have acquired the necessary environmental skills without much difficulty. The fact that the Fund staff already looks at the stock of mineral resource base in economies dependent on minerals, or the stock of oil in economies dependent on oil, or the stock of forests in economies dependent on timber, is already a good beginning. Such work should now be extended to other elements bearing on the environment, for example, soil base for productive agriculture, or the quality of air and water for human health and labor productivity. In his opinion, it will not be too difficult for Fund staff, who are well trained in economics, to acquire the relevant knowledge about the environment and to incorporate environmental concerns in their policy dialogues with the authorities of member countries.

Cielito Habito, the second panel discussant, reemphasized the need for the Fund to take environmental sustainability seriously for it is environmental sustainability that will ensure sustainability of economic growth in the longer run. In his opinion, integrating the environment into the design of macroeconomic programs should be relatively easy and can be done primarily through the design of the fiscal content of the program. On the public expenditure side, every attempt should be made to insulate environmental programs and projects from budgetary cutbacks, or at least prevent such programs and projects from becoming the first to suffer as a result of austerity measures. On the revenue side, the Fund staff could highlight environment-friendly tax measures, such as taxes on petroleum, pollution taxes, and forestry charges, in designing fiscal reform programs. Even in terms of other policy reforms, there was scope for structural adjustment programs to incorporate market-based incentive measures for encouraging the adoption of environmentally sound practices in the productive sectors of the economy, including appropriate pricing of natural resources and environmental charges. Habito was of the firm opinion that developing country policymakers are ready for policies that would support the objective of sustainable development and that environmental considerations are increasingly being woven into overall economic policymaking.

Andrew Steer, the third panel discussant, argued that, even with the knowledge that they currently have, Fund and Bank economists can do at least five things in support of the environment. First, they should be able to assess the first-order impacts of macroeconomic policy reforms on the environment in a more systematic manner. It should not be too difficult for them to prepare environmental impact statements covering, for example, the impact of devaluation and trade liberalization on the exportable extractive sector and on cropping patterns in the agricultural sector, the potential impact of budget cutbacks on public expenditures for environmental protection, and the potential impact of austerity on activity patterns among the poor. Second, having established these first-order impacts and identified the potential adverse effects, if any, they should be able to help countries design “first-best” environmental policies to mitigate such effects and, at the same time, integrate them into adjustment programs. It does not matter whether these policies are actually woven into the adjustment programs or are implemented in parallel; what does matter is that macroeconomic and environmental reforms get implemented simultaneously and effectively. Third, Fund and Bank economists should make every effort to incorporate environmental concerns into calculations of national income and other macroeconomic aggregates. Without this, one will never know if the nations are saving enough for the future. The present focus of Fund and Bank staff on man-made and produced assets only, to the complete neglect of natural assets and human assets, is shortsighted. Fourth, the Fund and Bank economists simply have to gain a better understanding of the impacts that structural reforms have on the environment, via their effects on informal traditional mechanisms, such as water and forest users associations, traditional communal management mechanisms, business-led self-enforcement schemes, voluntary conservation organizations. In Steer’s opinion, they, even more than governments, are the most effective mechanisms for the protection of the environment, especially in a developing country. Fifth, the staff of the two Bretton Woods institutions must build the support for macroeconomic stability and macroeconomic policy reforms within the environmental community, especially the mainstream analytical and professional NGOs. Steer thus saw ample scope for Fund and Bank staff to internalize environmental objectives into macroeconomic policy work even with the current state of knowledge.

Ved Gandhi, acting as the final panel discussant, highlighted what he considered to be the major conclusions of the seminar for the Fund staff. First, ignoring environmental degradation means ignoring its impact on human capital, natural capital, and output, all of which have a bearing on the sustainability of macroeconomic stability and economic growth. The Fund staff is therefore ill advised to ignore instances of serious environmental degradation or depletion of natural resources. Second, green national accounts are not absolutely essential for formulating appropriate short-term financial and macroeconomic policies. The Fund staff need not wait until environmentally adjusted national accounts become ready; until that occurs, they can take into account the most important environmental indicators, including the need for maintaining the basic social services, in designing macroeconomic and fiscal programs. Third, in some industrial countries where computable general equilibrium modeling is prevalent and the authorities have started using this tool in pursuing their economic objectives consistent with environmental targets, the Fund staff can bring this work to bear on their policy dialogues with the authorities. Fourth, the Fund staff can help countries exploit the very many win-win possibilities, giving greater attention to the removal of subsidies on environmentally damaging inputs, adjustment of utility and energy prices, levying or raising of stumpage fees, levying or increasing of environmental taxes, users’ fees, and other measures, and, at the same time, protecting crucial and essential environmental expenditures and investments from budgetary cuts. Fifth, the Fund staff can start examining the National Environmental Action Plans, wherever they exist, and start to bring the economic and environmental ministries together to identify the interest of the authorities in pursuing them. The staff can, then, help the authorities work out the financial and fiscal implications of such plans, if this has not already been done.

Vito Tanzi, in making his concluding remarks, pursued the question of the future involvement of the Fund staff with the environment. He admitted that knowledge about the extent of environmental degradation and the analytical tools readily available to deal with the subject are far from perfect and that prescriptions about environmental problems cannot be made with a great deal of confidence. Besides, one cannot foresee the role of technological change in presenting solutions that may be easier to adopt.

Nonetheless, Tanzi stressed that there are a few things that the Fund staff can do even without necessarily changing the mandate of the institution. They can make themselves aware of environmental concerns of the countries they work on. They can make these concerns enter into macroeconomic policy dialogues with the authorities of all countries, including countries not seeking financial support, to the extent that the authorities wish them to do so. Where the Fund is providing balance of payments support, they can encourage the country authorities to exploit various win-win opportunities highlighted again and again in the seminar. The Fund staff could also encourage developing countries with serious environmental problems and without institutional capabilities to seek assistance from the World Bank to develop appropriate complementary environmental policies for the short run as well as for the long run. Finally, Tanzi emphasized that the pace at which the Fund staff can act on the environment would depend upon the pace at which the countries themselves integrate their environmental concerns into their macroeconomic policymaking.

Within Same Series

- 6. Environmental Policies and Sustainable Development in the Arab World1

- Chapter 1. Summary for Policymakers

- Chapter 5 Summary and Conclusions

- 1. Economic Development of the Arab Countries: The Basic Issues

- 5. Macroeconomic Effects of Carbon Taxes

- XXI. Satellite analysis and accounts

- 1 Introduction and Summary

- Environment

- Chapter 3. Rationale for and Design of Fiscal Policy to “Get Energy Prices Right”

Other IMF Content

- 4 Macroeconomic Policies and the Environment

- 8 Macroeconomics and the Environment: Norwegian Experience

- 3 How Macroeconomic Policies Affect the Environment: What Do We Know?

- Public Expenditure and the Environment

- Public Policy and the Environment

- The IMF and the Environment

- 11 Panel Discussion

- 9 Economy-Wide Policies and the Environment: Developing Countries

- 10 What Is Reasonable to Expect of the IMF on the Environment?

Other Publishers Content

Asian development bank.

- Country Integrated Diagnostic on Environment and Natural Resources for Nepal

- Mongolia: Environment Sector Fact Sheet

- Climate Change, Coming Soon to a Court Near You: International Climate Change Legal Frameworks

- Climate Change, Coming Soon to a Court Near You: Report Series Purpose and Introduction to Climate Science

- Climate Change, Coming Soon to a Court Near You: National Climate Change Legal Frameworks in Asia and the Pacific

- Scaling Natural Capital Investments in the Yellow River Ecological Corridor

- Strengthening the Environment Dimensions of the Sustainable Development Goals in Asia and the Pacific: Knowledge-Sharing Workshop Proceedings

- Yangtze River Protection Law of the People's Republic of China: Overview of Key Provisions and Policy Recommendations

Inter-American Development Bank

- Annual Report on the Environment and Natural Resources 1996

- Annual Report on the Environment and Natural Resources 2002

- Ensuring Healthy Environments

- Annual Report on the Environment and Natural Resources 1998

- Facing the Challenges of Sustainable Development: The IDB and the Environment; 1992-2002

- Annual Report on the Environment and Natural Resources 1997

- Annual Report on the Environment and Natural Resources 1999

- Annual Report on the Environment and Natural Resources 2003: Special Focus; Water

- Evaluation of MIF Projects: Environment

- Blue Ribbon Panel on the Environment: Final Report of Recommendations

Nordic Council of Ministers

- BAT and Cleaner technology in Environmental Permits: Part 1: Summary, Analysis and Conclusion

- Agriculture and the environment in the Nordic countries: Policies for sustainability and green growth

- Siloxanes in the Nordic Environment

- The Nordic Energy Markets and Environment

- Brominated Flame Retardants (BFR) in the Nordic Environment

- Screening of phenolic substances in the Nordic environments

- Using the right environmental indicators: Tracking progress, raising awareness and supporting analysis: Nordic perspectives on indicators, statistics and accounts for managing the environment and the pressures from economic activities

- Selected Plasticisers and Additional Sweeteners in the Nordic Environment

The World Bank

- Mainstreaming the environment: the World Bank Group and the environment since the Rio Earth Summit : fiscal 1995 : summary.

- West Bank and Gaza Environment Priorities Note

- Building Blocks for a Sustainable Future: A Selected Review of Environment and Natural Resource Management in the Republic of Belarus

- Lao PDR Environment Monitor

- Food Safety, the Environment, and Trade

- The Poverty/Environment Nexus in Cambodia and Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Implementation of Environmental Policies: 2010 Environment Strategy.

- Modern Companies, Healthy Environment: Improving Industrial Competitiveness through Potential of Cleaner and Greener Production.

- Transportation and the Environment: A Review of Empirical Literature

- The Macroeconomic Environment for Jobs in South Sudan: Jobs, Recovery, and Peacebuilding in Urban South Sudan - Technical Report II

Table of Contents

- Front Matter

- 1 Macroeconomics and the Environment: Summary and Conclusions

- 2 Welcoming Remarks

- Session 1 Analytics

- 5 How the Environment Affects the Macroeconomy

- Session 2 Integration of Economic and Environmental Accounts

- 6 Environmental Accounting: A Framework for Assessment and Policy Integration

- 7 National Accounts and the Environment

- Session 3 Experience

- Session 4 Looking Ahead

- 12 Concluding Remarks

- Back Matter

International Monetary Fund Copyright © 2010-2021. All Rights Reserved.

- [66.249.64.20|195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Character limit 500 /500

Macroeconomics

Macroeconomics focuses on the performance of economies – changes in economic output, inflation, interest and foreign exchange rates, and the balance of payments. Poverty reduction, social equity, and sustainable growth are only possible with sound monetary and fiscal policies.

Reforms and relief: How Somalia turned a page amid a global debt crisis

Somalia's achievements in debt reduction send a clear signal to the world: the country turned an important page in history—yet big challenges remain ahead.

Rising to the Challenge: Policy Action in Low-Income Countries and the Role of the International Community

How can low-income countries foster economic stability and sustainable growth? Join us to explore solutions and the role of the international community.

Global Economic Prospects

What will it take to generate the kind of investment boom needed to step up productivity, increase incomes, and reduce poverty? Find out in the World Bank's Global Economic Prospects 2024.

Macroeconomics At-A-Glance

Macroeconomics connects together the countless policies, resources, and technologies that make economic development happen. Without proper macro management, poverty reduction and social equity aren't possible.

Macro Poverty Outlook

The twice-annual MPO provides country-by-country analysis and poverty projections for the developing world. Read the full report on 145 countries, download individual country sheets or interact with the data.

Focus Areas

Debt financing is critical for development. When used wisely it can help achieve sustained inclusive growth.

Taxes & Government Revenue

The collection of taxes and fees allows governments to deliver essential public services and achieve broader development goals.

Macroeconomic Analysis

Country Economic Updates

Regional Economic Updates

Public Finance Reviews

Debt Statistics

- Global growth is set for the weakest half-decade performance in 30 years

- By indicator

The global recovery from the 2020 pandemic recession remains subdued, with 2020-24 expected to mark the weakest start to a decade for global growth since the early 1990s—another period characterized by geopolitical strains and a global recession. Learn more.

Global Director, Macroeconomics, Trade and Investment

Stay Connected

News & events, latest events.

Debt & Fiscal Risks Toolkit

The World Bank Group helps countries manage debt and fiscal risks effectively. We offer a specific set of tools and reports to help countries balance the need for financing development while minimizing costs and risk.

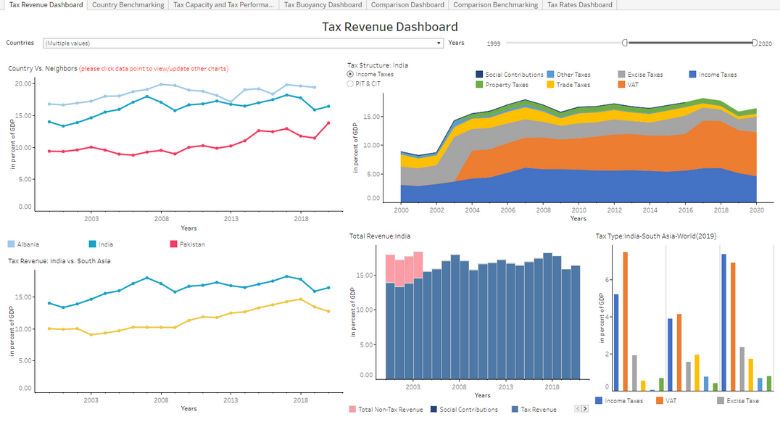

World Bank Revenue Dashboard

The Revenue Dashboard is a tool for benchmarking tax policy performance. The dashboard aims to provide policymakers and researchers with necessary data and information to conduct a high-level analysis of a country's tax ...

Debt Reporting Heat Map

How transparent are IDA countries in their debt reporting practices? This heat map presents an assessment based on the availability, completeness, and timeliness of public debt statistics and debt management documents ...

Innovations in Tax Compliance

A World Bank report demonstrates that building trust in governments is a fundamental step to make tax systems work better, benefiting all citizens.

Work With Us In Macroeconomics

Subscribe to our newsletters, additional resources, areas of expertise.