PhD Competence Model

- Once you have downloaded the file, you must first extract the ZIP file;

- Then right-click on the file, then 'properties', then 'unblock'.

References:

Doctoral school

PhD Competence Model

The Amsterdam UMC Doctoral School aims at creating an infrastructure to promote and support this excellence level training. PhD candidates are challenged to model their own learning processes. Offering a self-assessment tool for PhD competences is one way to encourage PhD candidates to self-reflect on their capacities and further develop themselves

Collectively the University Medical Centers have defined a set of core competences for PhD candidates as a guideline for professional career development, and to recognize acquired competences. Of course these competences are also very relevant for postdoc's

The PhD Competence Model (the download doesn't work inside the CDW or VIEW) is designed as an easy-to-use self-assessment tool. It reflects the competences an AMC PhD candidate should have acquired by the end of his/her PhD track, depending on his/her career perspective.

The emphasis of the model is on personal development and career orientation. The user evaluates his/her level on the given competence, using a 5-point scale from zero to five (excellent). A score of three reflects an average level based on peer group. The final profile can be viewed in a spider graph. The results are available offline only. The PhD Competence Model can be used yearly to monitor progress

Tips for use

- The tool is for self-assessment purposes only. It is explicitly not to be used as an appraisal or assessment tool

- We recommend that you consult peers and your supervisors for feedback

- Select a number of competencies per year that you would like to develop; the competence categories may differ per year based on your research goals and ambitions

- Use the completed self-evaluation as part of your PhD Plan, and extrapolate your learning objectives for the coming year (i.e. Intended Learning Outcomes or ILO's)

- Competences are shown in behavior. Note the references and examples of behavior used to evaluate your level on each specific competence, so that you can compare your performance levels over the years

- Once your individual profile is completed, it is important to consult available courses, workshops etc to enhance your skills. See the Amsterdam UMC Doctoral School course program

- The tool can also be used as input for career planning discussions or even for job applications (employers and employees)

- Whilst the model was designed for PhD candidates, it can of course be used in postdoctoral careers also

Back to "PhD Trajectory"

PhD Competence Model

PhD Competence model The PhD Competence Model is a self-assessment tool to increase awareness of needed and acquired competences for PhD candidates, to improve career planning.

The Dutch University Medical Centers (NFU) designed the PhD Competence Model: an instrument to enhance the professional and career development of a PhD candidate . The model helps PhD candidates more efficiently direct their time towards improving skills areas that are most needed for their own personal career development .

We encourage PhD candidates to challenge themselves and model their own learning processes in order to become a highly qualified future professional in an international environment. The PhD C ompetence model is one way to encourage self-reflect ion on capacities to further develop one self. Seven competence areas are defined: at the centre Research Skills and Knowledge, surrounded by Responsible Conduct of Research, Personal Effectiveness, Professional Development, Leadership and Management, Communication, and Teaching. Each area comprises a number of specific competences.

The PhD Competence Model is explicitly not designated for assessment or appraisal and for commercial purposes. This model can be used free of charge.

Instructions

- Download the tool via the website: https://phdcompetencemodel.nl .

- In order to use the PhD Competence Model application through the given link , a n Excel file will have to be downloaded and saved locally. The model can be used by opening the file in Excel on a Windows or Apple PC.

- Evaluate the level on the given competence, using a 5-point scale from zero to five (excellent). A score of three reflects an average level based on peer group.

- A PhD candidate can consult their peers and their supervisors for feedback.

- Competences are shown in behaviour . Note the references and examples of behaviour used to evaluate a PhD candidate’s level on each specific competence, so that they can compare their performance levels over the years.

- The final profile can be viewed in a spider graph. The results are available offline only.

- The PhD Competence Model can be used yearly to monitor progress, and as input for career planning discussions or even for job applications.

- We recommend that PhD candidates s elect a number of competencies per year that they would like to develop; the competence categories may differ per year based on their research goals and ambitions.

- Use the completed self-evaluation as part of the individual Training and Supervision Plan (TSP) and extrapolate learning objectives for the coming year.

- An o verview of Erasmus MC Graduate School courses can be found In the E UR course catalogue .

- The model can also be used by postdoctoral researchers.

Mijn situatie

- Spoedsituatie

- Ik heb een afspraak

- Mijn kind heeft een afspraak

- Ik wil verwijzen naar Amsterdam UMC

- Ik wil mijn bezoek plannen

Overzichten

- Poliklinieken en verpleegafdelingen

- Specialismen

- Bijzondere zorg (Expertisecentra)

- Soorten zorgverleners

- Wachtlijstinformatie

- Patiëntenfolders

- Laboratoriumbepalingen

- Gegevens wijzigen

- Mijn Dossier

- Rechten en plichten

- Route en parkeren

- Coronamaatregelen

- Ik wil arts worden

- Ik wil een academische opleiding in de zorg

- Ik ben aios

- I'm an international student

- Ik ben docent

Locatie AMC

- Opleiding Geneeskunde

- Opleiding Medische informatiekunde

- Opleiding Biomedische wetenschappen

- Medisch specialistische vervolgopleidingen

- Opleiding Verpleegkunde (HvA)

- Paramedische opleidingen (Hva) en stages

- PhD Courses (Graduate School)

- Bij- en nascholing/professionalisering

- Master Evidence Based Pratice in Health Care

- Master Health Informatics

- Faculty Development

- Instituut Onderwijs en Opleiden/Onderwijssupport

- Het Medical Skills and Simulation Center

Locatie VUmc

- Overzicht alle opleidingen

- Overzicht opleidingen per thema

- Overzicht opleidingen per doelgroep

- Over Amsterdam UMC

PhD Competence Model

AMC PhD candidates should be equipped to pursue a career inside or outside academia after their PhD track. Excellence in the doctorate level training of PhD candidates as highly qualified future professionals in an international environment is essential.

The AMC Graduate School aims at creating an infrastructure to promote and support this excellence. PhD candidates are challenged to model their own learning processes. Offering a self-assessment tool for PhD competences is one way to encourage PhD candidates to self-reflect on their capacities and further develop themselves.

Collectively the University Medical Centers have defined a set of core competences for PhD candidates as a guideline for professional career development, and to recognize acquired competences. Of course these competences are also very relevant for postdoc's. The PhD Competence Model * is designed as an easy-to-use self-assessment tool. It reflects the competences an AMC PhD candidate should have acquired by the end of his/her PhD track, depending on his/her career perspective.

*the download doesn't work inside the CDW of View.

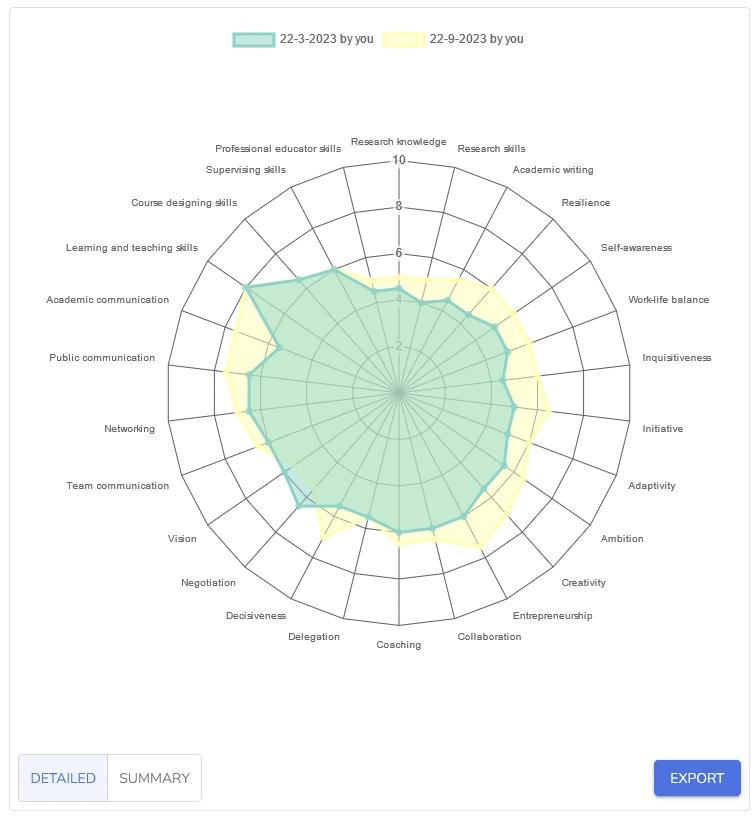

The emphasis of the model is on personal development and career orientation. The user evaluates his/her level on the given competence, using a 5-point scale from zero to five (excellent). A score of three reflects an average level based on peer group. The final profile can be viewed in a spider graph. The results are available offline only. The PhD Competence Model can be used yearly to monitor progress.

Tips for use

- The tool is for self-assessment purposes only. It is explicitly not to be used as an appraisal or assessment tool.

- We recommend that you consult peers and your supervisors for feedback .

- Select a number of competencies per year that you would like to develop; the competence categories may differ per year based on your research goals and ambitions.

- Use the completed self-evaluation as part of your individual Training and Supervision Agreement (iTSA), and extrapolate your learning objectives for the coming year (i.e. Intended Learning Outcomes or ILO's).

- Competences are shown in behavior . Note the references and examples of behavior used to evaluate your level on each specific competence, so that you can compare your performance levels over the years.

- Once your individual profile is completed, it is important to consult available courses, workshops etc to enhance your skills. See AMC PhD Course Program .

- The tool can also be used as input for career planning discussions or even for job applications (employers and employees).

- Whilst the model was designed for PhD candidates, it can of course be used in postdoctoral careers also.

Contact: AMC Graduate School

Overview of courses, workshops etc. for competences

Research skills and knowledge:.

See our courses on scientific methods, laboratory skills and research topics in the course schedule and also the IMI-EMTRAIN website with pan-European catalogue of courses for postgraduates and beyond in the biomedical sciences: on-course.eu

Responsible conduct of research:

Come to The AMC World of Science course. See our courses in the course schedule. Or look for more information on the following websites:

- Amsterdam UMC Research Code

- IXA AMC - for scientists

- Nederlandse Gedragscode Wetenschapsbeoefening

- European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity

- Netherlands Research Integrity Network

Personal effectiveness:

See our courses on transferable skills in the course schedule. Go to the website D okter Hoe (in Dutch) or follow courses on Het leerportaal (in Dutch) on the intranet.

Professional development:

See our courses in the course schedule. The AMC Young Talent Fund and Spinoza Fund offer grants for PhD researchers to go abroad. PCDI offers a course on Employability outside academia . The AMC Postdoc Network (Intranet) offers workshops on among others 'Your PhD or Postdoc and beyond' and Career lunches (also for last year PhDs).

Leadership & management:

See our courses on transferable skills in the course schedule. MBA in Healthcare Management , organized by the Amsterdam Business School. The AMC PhD association APROVE organizes a yearly PhD Career Event.

Communication:

See our courses on transferable skills in the course schedule. FameLab is an international competition in pitching your research, organized by the Britsh Council

See our courses on transferable skills in the course schedule. AMC BKO teacher professionalization (Intranet).

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Competency-based assessment for the training of PhD students and early-career scientists

Michael f verderame.

1 The Graduate School, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, United States

Victoria H Freedman

2 Graduate Division of Biomedical Sciences, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, United States

Lisa M Kozlowski

3 Jefferson College of Biomedical Sciences, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Wayne T McCormack

4 Office of Biomedical Research Career Development, University of Florida Health Sciences Center, Gainesville, FL, United States

Associated Data

There are no datasets associated with this work

The training of PhD students and early-career scientists is largely an apprenticeship in which the trainee associates with an expert to become an independent scientist. But when is a PhD student ready to graduate, a postdoctoral scholar ready for an independent position, or an early-career scientist ready for advanced responsibilities? Research training by apprenticeship does not uniformly include a framework to assess if the trainee is equipped with the complex knowledge, skills and attitudes required to be a successful scientist in the 21 st century. To address this problem, we propose competency-based assessment throughout the continuum of training to evaluate more objectively the development of PhD students and early-career scientists.

The quality of formal training assessment received by PhD students and early-career scientists (a label that covers recent PhD graduates in a variety of positions, including postdoctoral trainees and research scientists in entry-level positions) is highly variable, and depends on a number of factors: the trainee’s supervisor or research adviser; the institution and/or graduate program; and the organization or agency funding the trainee. The European approach, for example, relies more on one final summative assessment (that is, a high stakes evaluation at the conclusion of training, e.g. the dissertation and defense), whereas US doctoral programs rely more on multiple formative assessments (regular formal and informal assessments to evaluate and provide feedback about performance) before the final dissertation defense ( Barnett et al., 2017 ). Funding agencies in the US such as the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have recently increased expectations for formal training plans for individuals supported by individual or institutional training grants ( NIH, 2012 ); but these agencies support only a small fraction of PhD trainees via these funding mechanisms. This variation in the quality and substance of training assessment for PhD students and early-career scientists ( Maki and Borkowski, 2006 ) underscores the need for an improved approach to such assessment.

The value of bringing more definition and structure to the training environment has been recognized by professional organizations such as the National Postdoctoral Association , the American Physiological Society /Association of Chairs of Departments of Physiology, and some educational institutions and individual training programs. In addition, a recent NIH Funding Opportunity Announcement places increased emphasis on the development of both research and career skills, with a specific charge that “Funded programs are expected to provide evidence of accomplishing the training objectives”. Lists of competencies and skills provide guidelines for training experiences but they are rarely integrated into training assessment plans.

Based on our experience as graduate and postdoctoral program leaders, we recognized the need both to identify core competencies and to develop a process to assess these competencies. To minimize potential confirmation bias we deliberately chose not to begin this project with a detailed comparison of previously described competencies. Each author independently developed a list of competencies based on individual experiences. Initial lists were wide-ranging, and included traditional fundamental research skills (e.g., critical thinking skills, computational and quantitative skills), skills needed for different career pathways, (e.g., teaching skills), and business and management skills (e.g., entrepreneurial skills such as the ability to develop a business or marketing plan). Although we recognize that many of the competencies we initially defined are important in specific careers, from the combined list we defined 10 core competencies essential for every PhD scientist regardless of discipline or career pathway ( Table 1 ).

Table 1—source data 1.

Core competencies and subcompetencies.

Broad Conceptual Knowledge of a Scientific Discipline refers to the ability to engage in productive discussion and collaboration with colleagues across a discipline (such as biology, chemistry, or physics).

Deep Knowledge of a Specific Field encompasses the historical context, current state of the art, and relevant experimental approaches for a specific field, such as immunology or nanotechnology.

Critical Thinking Skills focuses on elements of the scientific method, such as designing experiments and interpreting data.

Experimental Skills includes identifying appropriate experimental protocols, designing and executing protocols, troubleshooting, lab safety, and data management.

Computational Skills encompasses relevant statistical analysis methods and informatics literacy.

Collaboration and Team Science Skills includes openness to collaboration, self- and disciplinary awareness, and the ability to integrate information across disciplines.

Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR) and Ethics includes knowledge about and adherence to RCR principles, ethical decision making, moral courage, and integrity.

Communication Skills includes oral and written communication skills as well as communication with different stakeholders.

Leadership and Management Skills includes the ability to formulate a research vision, manage group dynamics and communication, organize and plan, make decisions, solve problems, and manage conflicts.

Survival Skills includes a variety of personal characteristics that sustain science careers, such as motivation, perseverance, and adaptability, as well as participating in professional development activities and networking skills.

Because each core competency is multi-faceted, we defined subcompetencies. For example, we identified four subcompetencies of Critical Thinking Skills: (A) Recognize important questions; (B) Design a single experiment (answer questions, controls, etc.); (C) Interpret data; and (D) Design a research program. Each core competency has between two to seven subcompetencies, resulting in a total of 44 subcompetencies ( Table 1—source data 1 : Core Competencies Assessment Rubric).

Assessment milestones

Individual competencies could be assessed using a Likert-type scale ( Likert, 1932 ), but such ratings can be very subjective (e.g., “poor” to “excellent”, or “never” to “always”) if they lack specific descriptive anchors. To maximize the usefulness of a competency-based assessment rubric for PhD student and early-career scientist training in any discipline, we instead defined observable behaviors corresponding to the core competencies that reflect the development of knowledge, skills and attitudes throughout the timeline of training.

We used the “ Milestones ” framework described by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: “Simply defined, a milestone is a significant point in development. For accreditation purposes, the Milestones are competency-based developmental outcomes (e.g., knowledge, skills, attitudes, and performance) that can be demonstrated progressively by residents and fellows from the beginning of their education through graduation to the unsupervised practice of their specialties.”

Our overall approach to developing milestones was guided by the Dreyfus and Dreyfus model describing five levels of skill acquisition over time: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient and expert ( Dreyfus and Dreyfus, 1986 ). As trainees progress through competent to proficient to expert, their perspective matures, their decision making becomes more analytical, and they become fully engaged in the scientific process ( Dreyfus, 2004 ). These levels are easily mapped to the continuum of PhD scientist training: beginning PhD student as novice , advanced PhD student as advanced beginner , PhD graduate as competent , early-career scientist (that includes postdoctoral trainees) as proficient , and science professional as expert (see Table 2 ).

We therefore defined observable behaviors and outcomes for each subcompetency that would allow a qualified observer, such as a research adviser or job supervisor, to determine if a PhD student or early-career scientist had reached the milestone for their stage of training ( Table 1—source data 1 : Core Competencies Assessment Rubric). A sample for the Critical Thinking Skills core competency is shown in Table 3 .

Recommendations for use

We suggest that such a competency-based assessment be used to guide periodic feedback between PhD students or early-career scientists and their mentors or supervisors. It is not meant to be a checklist. Rather than assessing all 44 subcompetencies at the same time, we recommend that subsets of related competencies (e.g., “Broad Conceptual Knowledge of a Scientific Discipline” and “Deep Knowledge of a Specific Field”) be considered during any given evaluation period (e.g., month or quarter). Assessors should read across the observable behaviors for each subcompetency from left to right, and score the subcompetency based on the last observable behavior they believe is consistently demonstrated by the person being assessed. Self-assessment and mentor or supervisor ratings may be compared to identify areas of strength and areas that need improvement. Discordant ratings between self-assessment and mentor or supervisor assessment provide opportunities for conversations about areas in which a trainee may be overconfident and need improvement, and areas of strength which the trainee may not recognize and may be less than confident about.

The competencies and accompanying milestones can also be used in a number of other critically important ways. Combined with curricular mapping and program enhancement plans, the competencies and milestones provide a framework for developing program learning objectives and outcomes assessments now commonly required by educational accrediting agencies. Furthermore, setting explicit expectations for research training may enhance the ability of institutions to recruit outstanding PhD students or postdoctoral scholars. Finally, funding agencies focused on the individual development of the trainee may use these competencies and assessments as guidelines for effective training programs.

Why should PhD training incorporate a competency-based approach?

Some training programs include formal assessments utilizing markers and standards defined by third parties. Medical students, for example, are expected to meet educational and professional objectives defined by national medical associations and societies.

By contrast, the requirements for completing the PhD are much less clear, defined by the “mastery of specific knowledge and skills” ( Sullivan, 1995 ) as assessed by research advisers. The core of the science PhD remains the completion of an original research project, culminating in a dissertation and an oral defense ( Barnett et al., 2017 ). PhD students are also generally expected to pass courses and master research skills that are often discipline-specific and not well delineated. Whereas regional accrediting bodies in the US require graduate institutions to have programmatic learning objectives and assessment plans, they do not specify standards for the PhD. Also, there are few – if any – formal requirements and no accrediting bodies for early-career scientist training.

We can and should do better. Our PhD students, postdoctoral scholars, early-career scientists and their supervisors deserve both a more clearly defined set of educational objectives and an approach to assess the completion of these objectives to maximize the potential for future success. A competency-based approach fits well with traditional PhD scientist training, which is not bound by a priori finish dates. It provides a framework to explore systematically and objectively the development of PhD students and early-career scientists, identifying areas of strength as well as areas that need improvement. The assessment rubric can be easily implemented for trainee self-assessment as well as constructive feedback from advisers or supervisors by selecting individual competencies for review at regular intervals. Furthermore, it can be easily extended to include general and specific career and professional training as well.

In its recent report “Graduate STEM education for the 21 st Century”, The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018 briefly outlined core competencies for STEM PhDs. In its formal recommendations specifically for STEM PhD education, the first recommendation is, “Universities should verify that every graduate program that they offer provides for these competencies and that students demonstrate that they have achieved them before receiving their doctoral degrees.” This assessment rubric provides one way for universities to verify that students have achieved the core competencies of a science PhD.

We look forward to implementing and testing this new approach for assessing doctoral training, as it provides an important avenue for effective communication and a supportive mentor–mentee relationship. This assessment approach can be used for any science discipline, and it has not escaped our notice that it is adaptable to non-science PhD training as well.

Acknowledgements

We thank our many colleagues at the Association of American Medical Colleges Graduate Research, Education and Training (GREAT) Group for helpful discussions, and Drs. Istvan Albert, Joshua Crites, Valerie C Holt, and Rebecca Volpe for their insights about specific core competencies. We also thank Drs. Philip S Clifford, Linda Hyman, Alan Leshner, Ravindra Misra, Erik Snapp, and Margaret R Wallace for critical review of the manuscript.

Biographies

Michael F Verderame is in The Graduate School, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, United States

Victoria H Freedman is in the Graduate Division of Biomedical Sciences, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, United States

Lisa M Kozlowski is at Jefferson College of Biomedical Sciences, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Wayne T McCormack is in the Office of Biomedical Research Career Development, University of Florida Health Sciences Center, Gainesville, FL, United States

Funding Statement

The authors declare that there was no funding for this work.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Competing interests

No competing interests declared.

Additional files

Data availability.

- Barnett JV, Harris RA, Mulvany MJ. A comparison of best practices for doctoral training in Europe and North America. FEBS Open Bio. 2017; 7 :1444–1452. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12305. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. Mind over machine: The power of human intuition and expertise in the era of the computer. New York: The Free Press; 1986. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dreyfus SE. The Five-Stage model of adult skill acquisition. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. 2004; 24 :177–181. doi: 10.1177/0270467604264992. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology. 1932; 140 :52. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maki P, Borkowski NA. The Assessment of Doctoral Education: Emerging Criteria and New Models for Improving Outcomes. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- NIH Biomedical Research Workforce Working Group Report. [June 1, 2018]; 2012 https://acd.od.nih.gov/documents/reports/Biomedical_research_wgreport.pdf

- Sullivan RL. The Competency-Based Approach to Training. Baltimore, MD: JHPIEGO Corporation; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . In: Graduate STEM Education for the 21st Century. Leshner A, Scherer L, editors. The National Academy Press; 2018. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- eLife. 2018; 7: e34801.

Decision letter

In the interests of transparency, eLife includes the editorial decision letter and accompanying author responses. A lightly edited version of the letter sent to the authors after peer review is shown, indicating the most substantive concerns; minor comments are not usually included.

Thank you for submitting your article "Competency-Based Assessment for the Training of PhD Scientists" to eLife . I have assessed your article in my capacity as Associate Features Editor alongside my colleague Peter Rodgers (the eLife Features Editor) and a reviewer who has chosen to remain anonymous.

We all enjoyed reading your article and felt that the framework you have developed provides valuable guidance to PhD training that is currently lacking. Indeed, the reviewer stated that "I would look at introducing such a framework at my institution – this benefits both the student and supervisor".

I would therefore like to invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the following points.

Major revisions

1) There are comments about postdocs that do not always fit the narrative of the article. Therefore, it would be best to remove these to focus upon PhD students. Postdoc training is a lot harder to provide a framework for because it could be for anything between 1–5 years. I appreciate the need for such a postdoc framework but overall feel it is best to focus on the PhD aspects.

2) It is not clear from the article whether any PhD scientists have used your competency-based framework yet. Please could you include a section that discusses:

- How extensively the framework has been used so far

- Any assessments you might have performed of the effectiveness of competency-based training, or feedback you've received from PhD scientists and their advisors who have used the framework

- Any plans you have for implementing the approach more widely, or assessing its effectiveness

3) In paragraph four you state that you did not draw your list of competencies from previous lists, but to avoid confirmation bias developed lists based on your own experiences. Please could you discuss how this method avoided bias – could you not have been biased due to reading existing lists some time previously?

4) Mentioning the NSF and the NIH in the first sentence of the second paragraph makes the article very US focused – moving this sentence to later in this paragraph would make the article less US-centric. The article could also incorporate a deeper overview of other countries and practices. For example, many institutions across Europe require students to publish a number of articles before completion of their PhD, and such a goal does provide a "loose" framework for their development.

5) There are a few potential talking points that could be added to the competencies – there is flexibility as to which of the 10 competencies these points could fit. (1) Supervision of other students – this may develop from undergrad supervision through to MSc and lastly new PhD students. (2) An awareness of Innovation/Commercialisation – such as assay or technique development. (3) Public awareness/accountability – This is probably related to ethics but as most PhDs are public or charity funded then there should be a note relating to engagement with funders to understand their funding/operating mechanisms.

Author response

Major revisions 1) There are comments about postdocs that do not always fit the narrative of the article. Therefore, it would be best to remove these to focus upon PhD students. Postdoc training is a lot harder to provide a framework for because it could be for anything between 1–5 years. I appreciate the need for such a postdoc framework but overall feel it is best to focus on the PhD aspects.

We agree that a full framework for postdoctoral scholars would be complex, however, acquisition of skills continues after PhD completion, regardless of the first post-graduate position, or the ultimate career path. Accordingly we have renamed this category “Early Career Scientist”, and added a footnote describing this category.

2) It is not clear from the article whether any PhD scientists have used your competency-based framework yet. Please could you include a section that discusses: - How extensively the framework has been used so far - Any assessments you might have performed of the effectiveness of competency-based training, or feedback you've received from PhD scientists and their advisors who have used the framework - Any plans you have for implementing the approach more widely, or assessing its effectiveness

We have not deployed this framework yet but are anxious to do so precisely because we have not yet assessed it – we strongly feel that deploying it in the absence of at least concomitant testing to assess its validity would be unfair to trainees given the risk that it could be inappropriately used as a summative assessment tool (which is most definitely not our intent).

We have shared it with colleagues at several meetings of the AAMC’s Graduate Research Education and Training (GREAT) professional development group (this group consists of biomedical PhD program leaders, and associate deans of graduate education and postdoctoral training at US medical schools). We have also shared it with FASEB’s policy subcommittee on Training and Career Opportunities for Scientists. It has been presented at the NIH (NIGMS) and at a recent joint AAMC-FASEB conference. We have received extremely positive feedback. Based on this feedback, we are anxious to share it more widely, and feel that publication in eLife is an excellent vehicle to accomplish this first step.

From the beginning we have been committed to assessing the effectiveness of this framework. As we have presented it, we have had a number of discussions with variety of organizations (scientific societies, private foundations, educational advocacy groups, and others) that have expressed an interest in funding a multi-institutional assessment project. We anticipate that publication would generate additional interest and move the assessment process forward quickly.

As graduate education leaders we are immersed in the issues of the day, and are certainly aware of and had previously read some of the existing lists of competencies; indeed our extensive experience across the many facets of graduate education and postdoctoral training is what prompted us to start this project in the first place. Thus, we agree with the reviewers that ‘avoiding’ confirmation bias is too strong. We have revised the text to more accurately reflect our meaning: our goal was to minimize confirmation bias, which we did by not contemporaneously reviewing the lists of which we were aware when we initiated this project. We have revised the text accordingly.

We have moved the sentences discussing US practices to later in the paragraph. A recent article by Barnett et all (FEBS Open Bio. 7: 1444 (2017)) discussed the lack of formative assessments in the predominant European PhD model in comparison to regular such assessments in the US. While is it true that the US system has regular formative and summative assessments throughout a student’s PhD program (regular dissertation committee meetings, and one or more benchmark examinations during the student’s program), we would argue that the US system is a ‘loose’ framework, to the detriment of our students – hence the importance of this work. We have incorporated this point into the text early in paragraph two.

1) Supervision of others is already built into many of the assessments; we list several here (out of more than 20 milestones):

a) Competency 2 – Deep Knowledge: “Educate others”, “Train others” (at the Early Career Scientist stage)

b) Competency 3 – Critical thinking skills: “Evaluate protocols of others” (at the PhD Graduate Stage”, “Critique experiments of others (at the Early Career Scientist stage)

c) Competency 4 – Experimental skills: “Assist others” (at the Advanced PhD Student stage), “Help Others” (at the PhD Graduate Stage)

2) “Innovation… such as assay or technique development” is already incorporated into Sub-Competency 2B – Design and execute experimental protocols: “Build a new protocol” (at the Early Career Scientist stage). We determined that “Commercialisation” [sic] and other business and entrepreneurship skills are career specific skills that, while certainly important in some careers, are not a “core” PhD competency. We have slightly elaborated the text to bring this point out.

3) As we understand this comment “Public awareness” falls under Sub-competency 8-F “Communication with the public”. We strongly believe that “Public… accountability” is infused in every aspect of Competency 7 -Responsible Conduct of Research and Research Ethics”.

Core competencies for PhD candidates and postdocs

During their training, PhD and postdoc candidates are expected to become independent researchers skilled in (financial) project management, policy/decision making and management. These types of transferable skills stand candidates in good stead not just for an academic career but also for the professional job market beyond the university setting.

Self-assessment tool

Collectively the university medical centres designed a competence model as a self-assessment tool to help you further develop yourself, and to recognize acquired competences. See the NFU PhD Compentence Model .

Types of core compencies

- Research skills and knowledge

- Responsible conduct of science

- Personal effectiveness

- Professional development

- Leadership and management

- Communication

- Radboud specific

For each type of compencies we offer a number of courses if you feel that you use some extra training to enhance these skills.

- mijnRadboud

Courses for PhD candidates

Welcome to Research

- information on how Radboudumc conducts research →

- opportunities for my career within Radboudumc research →

- opportunities to participate or invest in Radboudumc research →

Here you can find all the courses for competencies and transferable skills for PhD candidates offered by Radboudumc and Radboud University.

Radboudumc has defined a set of core competencies for PhD and postdoc candidates as a guideline for professional career development.

Courses Radboudumc

Here you can find all our courses for PhD candidates.

Generic skills training courses are also offered by the RU.

Overview competencies

Formulate clear research questions and hypotheses, design solid research protocols as well as demonstrate in-depth knowledge of ones field.

Demonstrate the ability to make sound ethical and legal choices based on knowledge of accepted professional research practices, relevant policies and guidelines.

Adapt personal qualities and behaviours to achieve improved results.

Improve professional skills to further career prospects

Equipped to manage and develop project ideas as well as facilitate effective team work including problem solving skills. Also able to mentor others (e.g. students).

Demonstrate interpersonal, written, verbal, listening and non-verbal communication skills to be able to effectively and appropriately communicate facts, ideas or opinions to others.

Define the learning outcomes for the target group as well as adequately and suitably convey the material in a motivational manner.

Like attending Radboud Round and other networking and/or informative events organized by Raboudumc or one of the research institutes.

BMS courses free for PhD candidates

The research institute has agreed with Radboud Health Academy that PhD candidates can participate in BMS courses free of charge. However, specific conditions and procedures apply; those are outlined in this manual.

Overview study load

Time invested in courses is expressed in study hours. Study hours are defined by the course organizer or can be calculated.

Time invested in course is expressed in study hours. Study hours include both classroom teaching and time invested in self-study. For many courses, the time investement in hours is given in the course description. For some courses or other activities, this can be calculated using a set of rules. These rules, as well as the study load for a number of popular courses, are given in this document .

In case of discrepancies, the number of study hours in the course description is leading.

Courses at Radboud University

Courses for PhD candidates given at Radboud University can be found in gROW . The full course description lists the number of study hours. Please register for the course to read the full course description; this has no consequences. Only if you register for an ‘Event’, you will be placed in a group.

Courses at Radboudumc

Courses for PhD candidates given at Radboudumc are listed in the Online Learning Environment . Most applicable courses have listed the number of study hours in the course description. If this is not the case, please calculate according to these guidelines.

Courses from Master’s programs

Study load of all courses from Master’s programs are expressed in 'ECTS', which can be found in the course desciptions. One ECTS equals a load of 28 study hours.

- Information for employees

This website uses cookies. Read more about cookies.

Empower your PhD project

The aim of the Empower your PhD project (EmPhD) is for Leiden PhD candidates to gain more self-control over their personal and career development.

Dutch postgraduates say that they do not feel adequately prepared for a job within or outside the academic world. And that in a climate where current developments make it increasingly challenging for them to prepare for their future career. To help PhD candidates with their career development, it is important to improve their career competences.

EmPhD project

Self-reflection, setting goals and entrepreneurship are important career competences for personal development. In the EmPhD project, we examine the effects of an existing self-assessment tool in comparison with interventions where this tool is supported with personal coaching or group intervision among starting PhD students.

The self-evaluation tool is based on the PhD Competence Model that is already in use by other universities and university medical centres. PhD candidates have reported positive experiences with the use of this tool, but its effectiveness in increasing career competences is not yet known.

Research topic

T his project therefore focuses on this research topic and examines whether personal coaching and peer group intervision can enhance the effects of the tool. Once the findings from the study are known, we will advise the university about the use of interventions in this domain.

Our aim is to introduce evidence-based interventions that improve career opportunities for PhD candidates so that they acquire greater self-control over their personal and career development.

View the latest institution tables

View the latest country/territory tables

How young researchers can re-shape the evaluation of their work

Looking beyond bibliometrics to evaluate success.

Annemijn Algra, Inez Koopman, Rozemarijn Snoek

From left to right: Inez Koopman, Annemijn Algra, and Rozemarijn Snoek from Young SiT. Credit: Ivar Pel ( www.ivarpel.nl )

31 March 2020

Ivar Pel ( www.ivarpel.nl )

From left to right: Inez Koopman, Annemijn Algra, and Rozemarijn Snoek from Young SiT.

PhD students are experiencing a major evaluation gap: they are being assessed on criteria that do not match their own research goals, activities, or the role they wish to play in society.

To promote high-quality research, we need to change the incentives and rewards for career advancement in science.

It’s not easy to shift deeply ingrained practices, but finding an alternative to publication numbers as a measure of scientific quality has finally become a priority for research policy.

In 2018, our thinktank, Young SiT, started a grassroots movement at our institution, the University Medical Center Utrecht (UMC Utrecht) in the Netherlands, to reduce our focus on output metrics and promote better science.

As a result, PhD candidates are no longer being evaluated primarily on bibliometrics, but also on their research competencies and professional development.

Involve young scientists

Young SiT takes its name from the Science in Transition (SiT) movement launched at UMC Utrecht in 2013. Its motto is “ Fewer numbers, better science .”

SiT has spurred a broadening of assessment criteria at our institution, for instance, by also weighing the societal impact of a scientist’s work. Dutch universities as a whole have recently embraced a similar change , but they mainly impact senior scientists, allowing little involvement from young researchers.

As young scientists, we want to be involved in shaping the landscape that determines our day-to-day work, since we are the ones who will benefit most (namely, for the rest of our careers).

Young SiT’s goal is to improve and speed up a transition towards more open and responsible research evaluation. Our thinktank consists of 15 young scientists, ranging from PhD candidates to associate professors, all from different disciplines.

Through consensus discussion, we choose themes that we deem both relevant and feasible to tackle, such as responsible research evaluation, public engagement, and open science.

For each theme, we organize a mini-symposium for thinktank members and invited speakers from inside and outside science, such as people working in medical start-ups, to learn from best practices and to brainstorm on how changes can be implemented in young scientists’ daily research practices.

During a mini-symposium on the theme, ‘Career reward systems’, we concluded that young scientists would benefit from an evaluation method that promotes professional diversity and growth, instead of mainly output metrics.

A recent symposium run by Young SiT. Credit: Erik Kottier, UMC Utrecht

Change the evaluation form

Dutch universities often expect PhD dissertations in medical research to consist of at least four publications . At our institution, the PhD candidate evaluation form, which lists publications, abstracts, and prizes, was the main focus of the annual assessment of PhD candidates by their supervisors.

We devised a new evaluation form , based partly on an existing PhD competence model developed by Dutch university medical centers.

Our new form asks the PhD candidate to describe their two best accomplishments, motivated by personal or societal impact. Accomplishments can range from dealing with setbacks to speaking at a conference or a patient organization event.

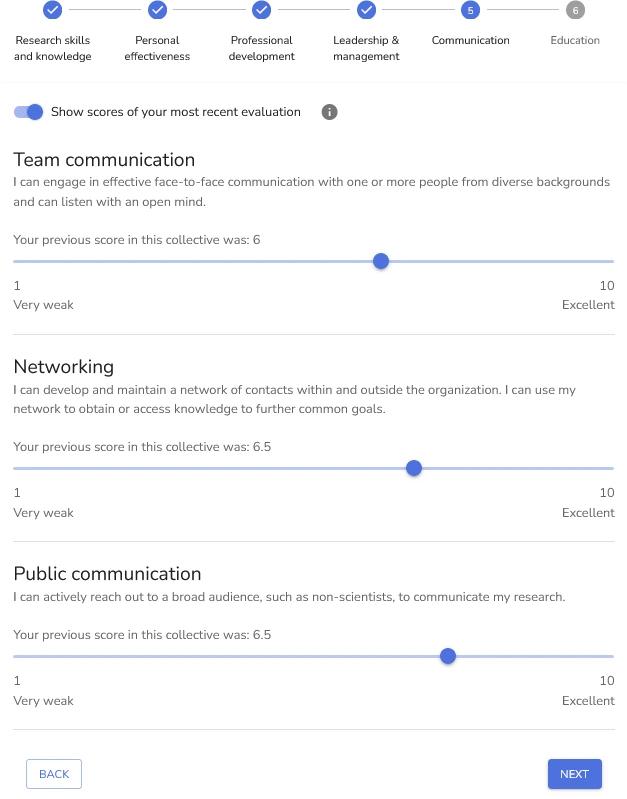

The new evaluation form also asks PhD candidates to self-evaluate their professional growth in research-related competencies, using the online Dutch PhD Competence Model tool . This tool focuses on competencies such as responsible conduct of science, communication, and leadership.

PhD candidates can create goals based on these competencies, which can serve as a conversation starter and a framework for their annual evaluation.

From idea to implementation

For the implementation of our new evaluation form, we chose the graduate program, Clinical and Experimental Neuroscience, where two of us are currently enrolled, as a starting point.

In the spring of 2019 we pitched our idea to the director, coordinator, and a representative body, and used their feedback to fine-tune and implement our evaluation form.

As of January 2020, around 200 PhD candidates in the graduate program now use this new evaluation form. This has motivated other graduate programs in the university to implement it also.

The Board of Studies of Utrecht University and PhD Council of the Utrecht Graduate School of Life Sciences are both showing interest in implementing our new PhD candidate evaluation form for all 1,800 of their PhD candidates.

Although a new evaluation form might seem like a small change, it empowers PhD candidates to discuss their professional development as part of their assessment. We believe this shows how science can benefit from grassroots movements like our Young SiT initiative.

There are many more themes and ideas that can be tackled like this, as was recently shown by the journal club initiative, ReproducibiliTea , which has set up journal clubs for researchers around the world to promote local open science communities and facilitate discussions about reproducibility of scientific work.

These initiatives show that we do not have to wait for institutions, funders, or journals to involve us. We, as young researchers, can start transforming science now.

Annemijn Algra and Inez Koopman are affiliated with the Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery at UMC Utrecht in the Netherlands. Rozemarijn Snoek is affiliated with the Department of Clinical Genetics at the UMC Utrecht. They write on behalf of the Young SiT.

Select language

Graduate School of Life Sciences

Doctoral thesis, thesis requirements.

At the end of your PhD journey, you will write a doctoral thesis and defend it in public. The doctoral thesis is submitted to the Assessment Committee before the end of your contract (if you are a PhD candidate with employee status). The requirements, procedures, responsibilities and rules are described in the Utrecht University Doctoral Degree Regulations ( English and Dutch ). The supervisory team, as well as the PhD candidate, are responsible for the quality of the research in the doctoral thesis, according to the prevailing standards.

The GSLS provides further details for the content of the doctoral thesis of a GSLS PhD candidate. A PhD journey is a training of a young academic towards an independent scientist, who is fit for a career inside or outside academia. Your doctoral thesis is a written document demonstrating your scientific development.

Thesis content

Your doctoral thesis contains at least a general introduction, publishable research chapters and a general discussion. The chapters in a thesis form a collective unit; you create a thread through your thesis that is reflected upon in the general discussion.

General introduction

In the general introduction, you describe your view of the current state-of-the-art in your discipline. You highlight gaps in scientific knowledge and introduce an overview of your thesis. The general introduction contains information that readers need to know in order to comprehend the context of your research chapters. A review article may be used as part of the general introduction. In that case, a short general introduction and overview of the thesis has to be added. There is explicitly no minimum length for the introduction; quality is the only criterion.

Research chapters

Each research chapter contains work, demonstrating that you followed the scientific research cycle:

- you identify a gap in scientific knowledge;

- you outline an approach;

- you describe an appropriate collection and analysis of data, or existing relevant databases;

- you reflect on the results within the context of the specific field.

The length and format of a chapter, the scientific depth, the quality of data collection and analysis thereof, should be of a level customary to your specific discipline. For further details, please read the section When can a manuscript be part of my thesis? (bottom of page). There is no requirement for the number of research chapters in a thesis: quality, coherence and your specific contributions prevail over quantity. The guideline is 3 or more publishable chapters, but fewer can be justified, for example, by the extensiveness of the work. We define a publishable research chapter as a (future) publication or a substantial part of a more extensive study.

General discussion

Where research chapters, and sometimes the general introduction, are collaborative efforts, the general discussion should be your own product. In this final chapter, you reflect with a birds-eye perspective on your research chapters and notable findings. You identify future opportunities for research, and discuss the impact on the research field and society. There is explicitly no minimum length for the discussion; quality is the only criterion.

Personal and scientific development

Your development is typically broader than the scientific content of your research chapters. You can reflect on your broader personal and scientific development in an attachment to your thesis. This is optional and may be used by the Assessment Committee to acquire a complete picture of you, as an academic in training. However, it falls outside your thesis content, and will not be judged by the Assessment Committee. You may use the GSLS PhD Competence Model (see Chapter 5.1) as a guideline to draft this attachment. Examples of such a PhD portfolio can be found here (pdf).

When can a manuscript be part of my thesis?

- The degree of your scientific contribution determines whether a manuscript can be part of your thesis. Not your position in the list of authors. Therefore, each chapter of your thesis should explicitly indicate how you have contributed to this work. If relevant, this also applies to the general introduction and discussion. Please find examples of author contribution here (pdf).

- Collection of data only by you is not sufficient in itself for inclusion of a chapter. You should have followed the scientific research cycle (see the section ‘Research Chapters’).

- If you, as part of a team effort, have conducted a crucial part of a larger study, but you are not the first, second or last author, the work can still be included in your thesis, as long as you explain your role in the study. If your contribution to that publication is not sufficient in itself to be a chapter, you may supplement the material with your own relevant work.

- A (publishable) research chapter does not already have to be submitted or accepted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal to be included in the thesis. However, you and your supervisors should strive to publish these chapters in peer-reviewed open-access scientific journals. For manuscripts that are published or will be in the future, you will be (co)author of the respective thesis chapters, in recognition of your scientific work.

Note: It is important to know that PhD candidates of Utrecht University are required to offer a digital version of their thesis to the University Library. The thesis will be incorporated into the Utrecht University Repository, the digital scientific archive of the university that is publicly available. You have to possibility to place an embargo on certain chapters of your thesis.

Your manuscript will be sent to the assessment committee using MyPhD (more information can be found here ). The Life Sciences deans would like to inform the committee members about the GSLS guidelines above. Hence, MyPhD sends a letter together with your manuscript. You can find the letter to the assessment committee here .

Utrecht University Heidelberglaan 8 3584 CS Utrecht The Netherlands Tel. +31 (0)30 253 35 50

- Supporting Organizations

- Privacy Policy

- Code-of-Conduct

- Initiatives

- Driving Institutional Change for Research Assessment Reform

Young researchers in action: the road towards a new PhD evaluation

A DORA Community Engagement Grants Report In November 2021, DORA announced that we were piloting a new Community Engagement Grants: Supporting Academic Assessment Reform program with the goal to build on the momentum of the declaration and provide resources to advance fair and responsible academic assessment. In 2022, the DORA Community Engagement Grants supported 10 project proposals. The results of the Young researchers in action: the road towards a new PhD evaluation project are outlined below.

By Inez Koopman and Annemijn Algra — Young SiT, University Medical Center Utrecht (Netherlands)

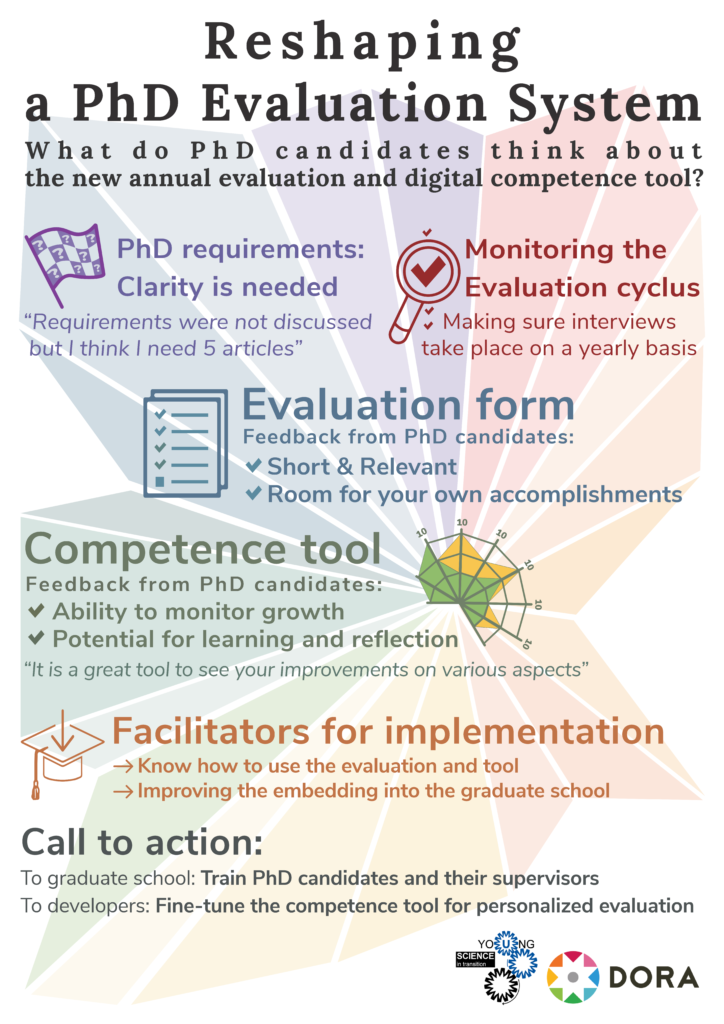

Less emphasis on bibliometrics, more focus on personal accomplishments and growth in research-related competencies. That is the goal of Young Science in Transition’s (Young SiT) new evaluation approach for PhD candidates in Utrecht, the Netherlands. But what do PhD candidates think about the new evaluation? With the DORA engagement grant, we did in-depth interviews with PhD candidates and found out how the new evaluation can be improved and successfully implemented.

The beginning: from idea to evaluation

Together with Young SiT, a thinktank of young scientists at the UMC Utrecht, we (Inez Koopman and Annemijn Algra) have been working on the development and implementation of a new evaluation method for PhD candidates since 2018.1 In this new evaluation, PhD candidates are asked to describe their progress, accomplishments and learning goals. The evaluation also includes a self-assessment of their competencies. We started bottom-up, small, and locally. This meant that we first tested our new method in our own PhD program (Clinical and Experimental Neurosciences, where approximately 200 PhD’s are enrolled). After a first round of feedback, we realized the self-evaluation tool (the Dutch PhD Competence Model) needed to be modernized. Together with a group of enthusiastic programmers, we critically reviewed its content, gathered user-feedback from various early career networks and transformed the existing model into a modern and user-friendly web-based tool.2

In the meantime, we started approaching other PhD programs from the Utrecht Graduate School of Life Sciences (GSLS) to further promote and enroll our new method. We managed to get support ‘higher up’: the directors and coordinators of the GSLS and Board of Studies of Utrecht University were interested in our idea. They too were working on a new evaluation method, so we decided to team up. Our ideas were transformed into a new and broad evaluation form and guide that can soon be used by all PhD candidates enrolled in one of the 15 GSLS programs (approximately 1800 PhD’s).

However, during the many discussions we had about the new evaluation one question kept popping up: ‘but what is the scientific evidence that this new evaluation is better than the old one’? Although the old evaluation, which included a list of all publications and prizes, was also implemented without any scientific evidence, it was a valid question. We needed to further understand the PhD perspective, and not only the perspective from PhD’s in early career networks. Did PhD candidates think the new evaluation was an improvement and if so, how it could be improved even further?

We used our DORA engagement grant to set up an in-depth interview project with a first group of PhD candidates using the newly developed evaluation guide and new version of the online PhD Competence Model. Feedback about the pros and cons of the new approach helps us shape PhD research assessment.

PhD candidates shape their own research evaluation

The main aim of the interview project was to understand if and how the new assessment helps PhD candidates to address and feel recognized for their work in various competencies. Again, we used our own neuroscience PhD program as a starting point. With the support of the director, coordinator, and secretary of our program, we arranged that all enrolled PhD candidates received an e-mail explaining that we were kicking off with the new PhD evaluation and that they were invited to combine their assessment with an interview with us.

Of the group that agreed to participate, we selected PhD candidates who were scheduled to have their annual evaluation within the next few months. As some of the annual interviews were delayed due to planning difficulties, we decided to also interview candidates who had already filled out the new form and competency tool, but who were still awaiting their annual interview with their PhD supervisors. In our selection, we made sure the group was gender diverse and included PhD candidates in different stages of their PhD trajectory.

We wrote a semi-structured interview topic guide, which included baseline questions about the demographics and scientific background of the participants, as well as in-depth questions about the new form, the web-based competency tool, the annual interview with PhD supervisors, and the written and unwritten rules PhD candidates encounter during their trajectory. 3 We asked members of our Young SiT thinktank and the programmers of the competency tool to critically review our guide. We also included a statement about the confidentiality of the data (using only (pseudo)anonymous data), to ensure PhD candidates felt safe during our interviews and to promote openness.

We recruited a student ( Marijn van het Verlaat ) to perform the interviews and to analyze the data. After training Marijn how to use the interview guide, we supervised the first two interviews. All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed. Marijn systematically analyzed the transcripts according to the predefined topics in the guide, structured emerging themes and collected illustrative quotes. We both independently reviewed the transcripts and discussed the results with Marijn until we reached a consensus on the thematic content. Finally, we got in touch with a graphical designer ( Bart van Dijk ) for the development of the infographic. Before presenting the results to Bart, we did a creative session to come up with ideas on how to visualize the generic success factors and barriers per theme. The sketches we made during this session formed the rough draft for the infographic.

The infographic

In total, we conducted 10 semi-structured interviews. The participants were between 26 and 33 years old and six of them were female. Most were in the final phase of their PhD (six interviewees versus two first-years and two in the middle of their trajectory). Figure 1 shows the infographic we made from the content of the interviews. Most feedback we received about the form and the competence tool was positive. The form was considered short and relevant and the open questions about individual accomplishment and learning goals were appreciated. Positive factors mentioned about the tool included its ability to monitor growth, by presenting each new self-evaluation as a spider graph with a different color, and the role it plays in learning and reflection. The barriers of our new assessment approach were often factors that hampered implementation, which could be summarized in two overarching themes. The first theme was ‘PhD requirements’, with the lack of clarity about requirements often seen as the barrier. This was nicely illustrated by quotes such as “I think I need five articles before I can finish my thesis”, which underscore the harmful effect of ‘unwritten rules’ and how the prioritization of research output by some PhD supervisors prevents PhD candidates from discussing their work in various competencies. The second theme was ‘monitoring of the evaluation cyclus’ and concerned the practical issues related to the planning and fulfillment of the annual assessments. Some interviewees reported that, even though they were in the final phase of their PhD, no interviews had taken place, as it was difficult to schedule a meeting with busy supervisors from different departments. Others noted that there was no time during their interview to discuss the self-evaluation tool. And although our GSLS does provide training for supervisors, PhD candidates experienced that supervisors did not know what to do and how to discuss the competency tool. After summarizing these generic barriers, we formulated facilitators for implementation, together with a call to action ( Figure 1 ). Our recommendation to the GSLS, or in fact any graduate school implementing a new assessment, is to further train both PhD candidates and their supervisors. This not only exposes them to the right instructions, but also allows them to get used to a new assessment approach and in fact an ‘evaluation culture change’. For the developers of the new PhD competence tool, this in-depth interview project has also yielded a lot of important user-feedback. The tool is being updated with personalized features as we speak.

Change the evaluation, change the research culture

The DORA engagement grant enabled us to collect data on our new PhD evaluation method. Next up, we will schedule meetings with our GSLS to present the results of our project and stimulate implementation of the new evaluation for all PhDs in our graduate school. And not only our graduate school has shown interest, other universities in the Netherlands have also contacted us to learn from the ‘Utrecht’ practices. That means 1800 PhD candidates at our university and maybe more in the future will soon have a new research evaluation. Hopefully this will be start of something bigger, a culture change from bottom-up, driven by PhD candidates themselves.

*If you would like to know more about our ideas, experiences, and learning, you can always contact us to have a chat!

Email addresses: [email protected] & [email protected]

1. Algra AM, Koopman I en Snoek R. How young researcher scan and should be involved in re-shaping research evaluation. Nature Index , online 31 March 2020. https://www.natureindex.com/news-blog/how-young-researchers-can-re-shape-research-evaluation-universities

2. https://insci.nl/

3. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1u6BIVzei0HaNHycQ77PY7wP1Oqy0KLqx7sXft2yDHl0/edit?usp=sharing

Haley Hazlett

DORA Steering Committee opportunity: Asia

Improving pre-award processes for equitable and transparent research assessment, copy link to clipboard.

Empower your PhD

Young Science in Transition and InSci collectively initiated the development of this easy-to-use, digital tool inspired by the well-known NFU Ph.D. Competence Model and MERIT (Management, Education, Research, Impact, and Team) Framework. Through both self and peer assessment, academics can make their efforts and competencies in all five MERIT subdomain insightful. Therefore, it adds to our purpose of teasing out academics' authentic capacities and intrinsic motivations and connecting those to the needs of the new (academic) realm.

InSci in action

Get a quick look at how InSci empowers academics to track their competencies.

Fill in an evaluation

You can either fill in an evaluation about yourself or let your peers evaluate you, using competencies provided by your university.

Visualize the results

After you have been evaluated one or more times, you can visualize the results and export them to PDF.

COMMENTS

The PhD Competence Model is a self-assessment tool. It is not to be used for assessment or appraisal. It can be used free of charge. The PhD Competence Model may not be used for commercial purposes. The Dutch University Medical Centers collectively designed the PhD Competence Model in 2016. Current version: September 2017.

This model contains a set of core competencies every PhD candidate should have. Next to academic skills, it emphasises personal development and career orientation. To help you identify what skills and competencies you may want to develop or improve, we encourage you to take a self-assessment of competence development.

PhD Competence Model. In 2016, Dutch University Medical Centres (UMCs) developed the self-evaluation tool based on the PhD Competence Model. Our partners at Utrecht University are making a digital version of the tool available free of charge for our PhD candidates at Leiden University, including for candidates who are not taking part in the study.

The PhD Competence Model (the download doesn't work inside the CDW or VIEW) is designed as an easy-to-use self-assessment tool. It reflects the competences an AMC PhD candidate should have acquired by the end of his/her PhD track, depending on his/her career perspective. The emphasis of the model is on personal development and career ...

The PhD Competence Model contains a set of core competencies every PhD candidate should have. Next to academic skills, it emphasises personal development and career orientation. To help you identify what skills and competencies you may want to develop or improve, we encourage you to take a self-assessment of competence development. This tool, developed by Young Scientists in Transition ...

PhD Plus core modules are associated with one or more of the six competency labels. Trainees can click on individual competency labels (e.g. Leadership & Management) to learn about a series of skills workshops, individual events, PhD stories and and experiential opportunities across core modules that can help develop a specific competency.

COURSES BY COMPETENCE. We encourage you to shape your learning trajectory by making use of the PhD Competence Model. Take the PhD Competence test to find out which core competences are already highly developed, and which ones you can opt to strengthen through one of the courses on offer.

The model can be used by opening the file in Excel on a Windows or Apple PC. Evaluate the level on the given competence, using a 5-point scale from zero to five (excellent). A score of three reflects an average level based on peer group. A PhD candidate can consult their peers and their supervisors for feedback. Competences are shown in behaviour.

For exam-ple, we identified four subcompetencies of Critical Thinking Skills: (A) Recognize important questions; (B) Design a single experiment (answer questions, controls, etc.); (C) Interpret data; and (D) Design a research program. Each core competency has between two to seven sub-competencies, resulting in a total of 44 subcom-petencies ...

the PhD candidate's personal skills. These skills are important to daily-life PhD activities and to prepare PhD candidates for their future careers. The main competences you can further develop as a PhD candidate are Autonomy & Self-management, Working with others, Teaching, Supervising & coaching, Effective Communication. The Transferable skills

The PhD Competence Model * is designed as an easy-to-use self-assessment tool. It reflects the competences an AMC PhD candidate should have acquired by the end of his/her PhD track, depending on his/her career perspective. *the download doesn't work inside the CDW of View. The emphasis of the model is on personal development and career orientation.

The PhD Competence Model is an easy-to-use self-assessment tool to increase awareness of needed and acquired competences for PhD candidates, to improve career planning in- and outside research. ...

Assessment milestones. Individual competencies could be assessed using a Likert-type scale (Likert, 1932), but such ratings can be very subjective (e.g., "poor" to "excellent", or "never" to "always") if they lack specific descriptive anchors.To maximize the usefulness of a competency-based assessment rubric for PhD student and early-career scientist training in any discipline ...

PhD Course Centre GSLS. The GSLS maintains a PhD Course Centre that organises trainings on general skills and competencies of the PhD Competence Model. The development of transferrable skills becomes increasingly important in pursuit of a career inside or outside academia. You are challenged to model your learning process to be well equipped ...

The PhD Competence Model is an eas y- to -use self-. assessment tool to increase awar eness of needed and. acquired competences f or PhD candidat es, to improv e. car eer planning in - and outside ...

Collectively the university medical centres designed a competence model as a self-assessment tool to help you further develop yourself, and to recognize acquired competences. See the NFU PhD Compentence Model. Types of core compencies. Research skills and knowledge; Responsible conduct of science; Personal effectiveness; Professional development

The self-evaluation tool is based on the PhD Competence Model that is already in use by other universities and university medical centres. PhD candidates have reported positive experiences with the use of this tool, but its effectiveness in increasing career competences is not yet known. Research topic

The top three desired categories after Degree and Achievements are Communication, Research, and Interpersonal skills, recorded in close to half of all the PhD postings (. Figure 2. ). In contrast, prior teaching and work experience are considered least important before doing a PhD.

The new evaluation form also asks PhD candidates to self-evaluate their professional growth in research-related competencies, using the online Dutch PhD Competence Model tool. This tool focuses on ...

You may use the GSLS PhD Competence Model (see Chapter 5.1) as a guideline to draft this attachment. Examples of such a PhD portfolio can be found here (pdf). When can a manuscript be part of my thesis? The degree of your scientific contribution determines whether a manuscript can be part of your thesis. Not your position in the list of authors.

The Graduate School of Medical Sciences is committed to offering a high-quality training environment for all its PhD students, making sure that they develop also professional and personal competences that go beyond scientific knowledge - competences that are transferable to careers both inside and outside academia. ... PhD Competence Model as ...

After a first round of feedback, we realized the self-evaluation tool (the Dutch PhD Competence Model) needed to be modernized. Together with a group of enthusiastic programmers, we critically reviewed its content, gathered user-feedback from various early career networks and transformed the existing model into a modern and user-friendly web ...

Young Science in Transition and InSci collectively initiated the development of this easy-to-use, digital tool inspired by the well-known NFU Ph.D. Competence Model and MERIT (Management, Education, Research, Impact, and Team) Framework. Through both self and peer assessment, academics can make their efforts and competencies in all five MERIT ...