61 intriguing psychology research topics to explore

Last updated

11 January 2024

Reviewed by

Brittany Ferri, PhD, OTR/L

Psychology is an incredibly diverse, critical, and ever-changing area of study in the medical and health industries. Because of this, it’s a common area of study for students and healthcare professionals.

We’re walking you through picking the perfect topic for your upcoming paper or study. Keep reading for plenty of example topics to pique your interest and curiosity.

- How to choose a psychology research topic

Exploring a psychology-based topic for your research project? You need to pick a specific area of interest to collect compelling data.

Use these tips to help you narrow down which psychology topics to research:

Focus on a particular area of psychology

The most effective psychological research focuses on a smaller, niche concept or disorder within the scope of a study.

Psychology is a broad and fascinating area of science, including everything from diagnosed mental health disorders to sports performance mindset assessments.

This gives you plenty of different avenues to explore. Having a hard time choosing? Check out our list of 61 ideas further down in this article to get started.

Read the latest clinical studies

Once you’ve picked a more niche topic to explore, you need to do your due diligence and explore other research projects on the same topic.

This practice will help you learn more about your chosen topic, ask more specific questions, and avoid covering existing projects.

For the best results, we recommend creating a research folder of associated published papers to reference throughout your project. This makes it much easier to cite direct references and find inspiration down the line.

Find a topic you enjoy and ask questions

Once you’ve spent time researching and collecting references for your study, you finally get to explore.

Whether this research project is for work, school, or just for fun, having a passion for your research will make the project much more enjoyable. (Trust us, there will be times when that is the only thing that keeps you going.)

Now you’ve decided on the topic, ask more nuanced questions you might want to explore.

If you can, pick the direction that interests you the most to make the research process much more enjoyable.

- 61 psychology topics to research in 2024

Need some extra help starting your psychology research project on the right foot? Explore our list of 61 cutting-edge, in-demand psychology research topics to use as a starting point for your research journey.

- Psychology research topics for university students

As a university student, it can be hard to pick a research topic that fits the scope of your classes and is still compelling and unique.

Here are a few exciting topics we recommend exploring for your next assigned research project:

Mental health in post-secondary students

Seeking post-secondary education is a stressful and overwhelming experience for most students, making this topic a great choice to explore for your in-class research paper.

Examples of post-secondary mental health research topics include:

Student mental health status during exam season

Mental health disorder prevalence based on study major

The impact of chronic school stress on overall quality of life

The impacts of cyberbullying

Cyberbullying can occur at all ages, starting as early as elementary school and carrying through into professional workplaces.

Examples of cyberbullying-based research topics you can study include:

The impact of cyberbullying on self-esteem

Common reasons people engage in cyberbullying

Cyberbullying themes and commonly used terms

Cyberbullying habits in children vs. adults

The long-term effects of cyberbullying

- Clinical psychology research topics

If you’re looking to take a more clinical approach to your next project, here are a few topics that involve direct patient assessment for you to consider:

Chronic pain and mental health

Living with chronic pain dramatically impacts every aspect of a person’s life, including their mental and emotional health.

Here are a few examples of in-demand pain-related psychology research topics:

The connection between diabetic neuropathy and depression

Neurological pain and its connection to mental health disorders

Efficacy of meditation and mindfulness for pain management

The long-term effects of insomnia

Insomnia is where you have difficulty falling or staying asleep. It’s a common health concern that impacts millions of people worldwide.

This is an excellent topic because insomnia can have a variety of causes, offering many research possibilities.

Here are a few compelling psychology research topics about insomnia you could investigate:

The prevalence of insomnia based on age, gender, and ethnicity

Insomnia and its impact on workplace productivity

The connection between insomnia and mental health disorders

Efficacy and use of melatonin supplements for insomnia

The risks and benefits of prescription insomnia medications

Lifestyle options for managing insomnia symptoms

The efficacy of mental health treatment options

Management and treatment of mental health conditions is an ever-changing area of study. If you can witness or participate in mental health therapies, this can make a great research project.

Examples of mental health treatment-related psychology research topics include:

The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for patients with severe anxiety

The benefits and drawbacks of group vs. individual therapy sessions

Music therapy for mental health disorders

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with depression

- Controversial psychology research paper topics

If you are looking to explore a more cutting-edge or modern psychology topic, you can delve into a variety of controversial and topical options:

The impact of social media and digital platforms

Ever since access to internet forums and video games became more commonplace, there’s been growing concern about the impact these digital platforms have on mental health.

Examples of social media and video game-related psychology research topics include:

The effect of edited images on self-confidence

How social media platforms impact social behavior

Video games and their impact on teenage anger and violence

Digital communication and the rapid spread of misinformation

The development of digital friendships

Psychotropic medications for mental health

In recent years, the interest in using psychoactive medications to treat and manage health conditions has increased despite their inherently controversial nature.

Examples of psychotropic medication-related research topics include:

The risks and benefits of using psilocybin mushrooms for managing anxiety

The impact of marijuana on early-onset psychosis

Childhood marijuana use and related prevalence of mental health conditions

Ketamine and its use for complex PTSD (C-PTSD) symptom management

The effect of long-term psychedelic use and mental health conditions

- Mental health disorder research topics

As one of the most popular subsections of psychology, studying mental health disorders and how they impact quality of life is an essential and impactful area of research.

While studies in these areas are common, there’s always room for additional exploration, including the following hot-button topics:

Anxiety and depression disorders

Anxiety and depression are well-known and heavily researched mental health disorders.

Despite this, we still don’t know many things about these conditions, making them great candidates for psychology research projects:

Social anxiety and its connection to chronic loneliness

C-PTSD symptoms and causes

The development of phobias

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) behaviors and symptoms

Depression triggers and causes

Self-care tools and resources for depression

The prevalence of anxiety and depression in particular age groups or geographic areas

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is a complex and multi-faceted area of psychology research.

Use your research skills to learn more about this condition and its impact by choosing any of the following topics:

Early signs of bipolar disorder

The incidence of bipolar disorder in young adults

The efficacy of existing bipolar treatment options

Bipolar medication side effects

Cognitive behavioral therapy for people with bipolar

Schizoaffective disorder

Schizoaffective disorder is often stigmatized, and less common mental health disorders are a hotbed for new and exciting research.

Here are a few examples of interesting research topics related to this mental health disorder:

The prevalence of schizoaffective disorder by certain age groups or geographic locations

Risk factors for developing schizoaffective disorder

The prevalence and content of auditory and visual hallucinations

Alternative therapies for schizoaffective disorder

- Societal and systematic psychology research topics

Modern society’s impact is deeply enmeshed in our mental and emotional health on a personal and community level.

Here are a few examples of societal and systemic psychology research topics to explore in more detail:

Access to mental health services

While mental health awareness has risen over the past few decades, access to quality mental health treatment and resources is still not equitable.

This can significantly impact the severity of a person’s mental health symptoms, which can result in worse health outcomes if left untreated.

Explore this crucial issue and provide information about the need for improved mental health resource access by studying any of the following topics:

Rural vs. urban access to mental health resources

Access to crisis lines by location

Wait times for emergency mental health services

Inequities in mental health access based on income and location

Insurance coverage for mental health services

Systemic racism and mental health

Societal systems and the prevalence of systemic racism heavily impact every aspect of a person’s overall health.

Researching these topics draws attention to existing problems and contributes valuable insights into ways to improve access to care moving forward.

Examples of systemic racism-related psychology research topics include:

Access to mental health resources based on race

The prevalence of BIPOC mental health therapists in a chosen area

The impact of systemic racism on mental health and self-worth

Racism training for mental health workers

The prevalence of mental health disorders in discriminated groups

LGBTQIA+ mental health concerns

Research about LGBTQIA+ people and their mental health needs is a unique area of study to explore for your next research project. It’s a commonly overlooked and underserved community.

Examples of LGBTQIA+ psychology research topics to consider include:

Mental health supports for queer teens and children

The impact of queer safe spaces on mental health

The prevalence of mental health disorders in the LGBTQIA+ community

The benefits of queer mentorship and found family

Substance misuse in LQBTQIA+ youth and adults

- Collect data and identify trends with Dovetail

Psychology research is an exciting and competitive study area, making it the perfect choice for projects or papers.

Take the headache out of analyzing your data and instantly access the insights you need to complete your next psychology research project by teaming up with Dovetail today.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 15 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

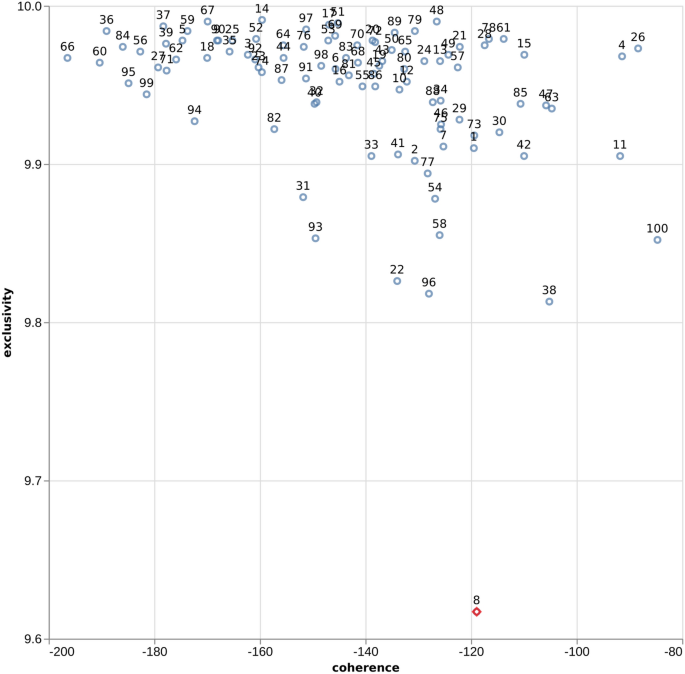

Research Topics & Ideas: Psychology

100+ Psychology Topic Ideas To Fast-Track Your Research

If you’re starting out on the dissertation or thesis journey for your psychology degree, the very first challenge you’ll face is finding a solid research topic . In this post, we’ll help get the topic ideation process started by providing a meaty list of research ideas, spanning a range of psychology sub-disciplines. We’ll also look at some examples from actual theses and dissertations to give you an idea of what these look like in the real world.

NB – This is just the start…

The topic ideation and evaluation process has multiple steps (which we’ll explain a little later). Therefore, it’s important to recognise that this post is only the first step in finding a high-quality psychology-centred research topic. To develop a research topic, you’ll need to identify a clear and convincing research gap , and a viable plan of action to fill that gap.

If this all sounds a bit intimidating, be sure to check out our free dissertation mini-course , which covers the process of writing a dissertation or thesis from A-Z. You can also sign up for our free webinar that explores how to find a high-quality research topic. Alternatively, if you’d like hands-on help, have a look at our 1-on-1 coaching service .

Overview: Psychology-Related Topics

- How to find a research topic (video)

- Behavioural psychology

- Clinical psychology

- Cognitive psychology

- Developmental psychology

- Educational psychology

- Forensic psychology

- Social psychology

- Sports psychology

- Examples of actual dissertation topics

- Free Webinar : Topic Ideation 101

- Where to get extra help

How To Find A Research Topic

In the video below, we explain how to find suitable research ideas (in psychology or any field), and how to then refine those into well-articulated potential topics for your dissertation or thesis. We also discuss a few important evaluation criteria to help you make the right choice for your project.

Below you’ll find a list of research ideas to get your thinking started. Please note that these research topic ideas are intentionally broad and generic, so you will need to refine them a fair deal using the techniques we discussed in the video above.

We’ve grouped the topic ideas based on a few popular areas of psychology to make it a little easier for you to find something in your particular field of interest. That said, there is naturally some overlap between topics, so keep this in mind.

Research Ideas: Behavioural Psychology

- Cultural variation in behaviour and mental health of adolescents during a disaster: a case study

- The impact of parental drug use and risky behaviour on early child development

- The effects of video game violence on aggressive behaviour among teenage boys in school

- The relationship between adverse childhood experiences and adult risk-seeking behaviour

- The impact of physical exercise on anxiety and health-harming behaviour

- The relationship between personality traits and addiction behaviour

- The effects of reinforcement schedules on decision-making and associative learning

- The effects of daily mindfulness practice on stress and anxiety in middle-aged women

- The use of behavioural interventions in the treatment of eating disorders in poorer communities

- Understanding implicit cognitive processes involved in the over-consumption of fast food

- The use of cognitive behavioural therapy for alcohol addiction treatment

- The impact of extensive technology use in children on long-term attention and focus

- The impact of social media on self-destructive behaviour and poor mental health outcomes

- Exploring the role of sleep and sleep deprivation on healthy behaviours

Research Ideas: Clinical Psychology

- The use of mindfulness-based approaches in the treatment of anxiety disorders among college students

- The use of technology in the delivery of psychological services in war-torn countries

- The effectiveness of dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder

- The use of virtual reality technology in the treatment of phobias and PTSD among war veterans

- The role of childhood adversity on adult mental health in immigrant populations in the USA

- The role of genetics and epigenetics in the development of bipolar disorder in Pakistani women: an integrative review

- The effectiveness of pharmacotherapy in the treatment of social anxiety among hikikomori in Japan

- The perception of healthcare workers and patients on the use of teletherapy for the delivery of psychological services

- The impact of social support on mental health outcomes among single parents.

- The effectiveness of integrative therapeutic approaches in the treatment of schizophrenia

- The effectiveness of trauma-focused therapies on post-traumatic growth in domestic abuse survivors

- The role and use of cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression among first-generation students

- The effectiveness of family therapy in addressing childhood trauma and depression

- The impact of cultural mistrust on the diagnosis and treatment of mental health issues in culturally-diverse populations

- The effectiveness of group therapy on post-traumatic stress symptoms among survivors of sexual assault

Research Ideas: Cognitive Psychology

- The impact of lifelong aerobic exercise on cognitive function in old age

- The effects of evening screen use on cognitive development in preschool children

- The impact of sleep deprivation on decision-making among graduate students

- The use of neuroimaging to understand the neural basis of memory retrieval

- The effect of conservative religious homes on social functioning in LGBT+ adolescents

- The role of positive emotions in working memory among high school learners

- The neural basis of decision-making and problem-solving during undergraduate statistic assessments

- The neural basis of language processing among adults learning English as a second language

- The role of technological tools in improving working memory in older adults

- The role of attention in emotional face processing among adult males

- The impact of depression on cognitive function during ageing The impact of daily meditation and mindfulness practice on cognitive function

- The relationship between increased protein intake and improved cognitive function

- The effects of stress on cognitive function among final-year learners

Research Ideas: Developmental Psychology

- The impact of maternal affection on cognitive, social, and emotional development

- The effects of parenting styles on children’s executive function

- The impact of late-night screen use on child development

- The role of digital play on child development outcomes

- Exploring the impact of poverty on early child development in Brazil

- The trauma-informed care as moderating the impact of trauma on child development

- Evaluating the relationship between peer relationship quality and child social development

- The impact of child-targeted media and advertising on child behavioural development

- The role of parental attachment in child resilience

- The moderating impact of culture on bullying and child social development

- The impact of single-parenting on child development in India

- The impact of early educational interventions on child socio-emotional development

- The impact of digital technology use on adolescent development and mental health

- The impact of socioeconomic status on child executive function

- The role of genetics and epigenetics on child neurodevelopmental outcomes linked to depression

Need a helping hand?

Research Ideas: Educational Psychology

- The relationship between self-regulated learning and academic performance in asynchronous versus synchronous learning environments

- Exploring effective parental involvement strategies and their impact on student achievement

- The role of intrinsic motivation in formative assessment in the classroom

- The impact of classroom management and practice on student learning and behaviour

- University students’ preference regarding online learning environments

- The effects of gentrification on student achievement in traditionally poor neighbourhoods

- The impact of teacher expectations and academic self-concept on K12 student mathematics performance

- The use and effectiveness of game-based learning in a high school biology classroom

- The impact of prejudice on the relationship between student motivation and academic performance among Black university students

- The impact of culture on second language English student learning preferences

- The effects of student self-efficacy and engagement on academic performance in secondary school mathematics

- The role of metacognition in learning musicality in hip hop

- The role of small group instruction on teacher efficacy and stress in early childhood education

- The perception and use of multimedia among high school biology teachers in France

- The use of augmented reality applications and its impact on student learning, motivation and attitude

Research Ideas: Forensic Psychology

- The impact of trauma on the psychological functioning of police officers and first responders

- Understanding cultural considerations during forensic psychological assessment and treatment of trauma

- Ethical considerations of the use of AI in forensic psychology in the legal system

- The psychological factors related to recidivism among white collar female offenders in the USA

- The psychological factors related to false confessions among juveniles

- Understanding the use of psychological assessment in the evaluation of eyewitness testimony in criminal courts in England

- The impact of trauma on the reflective functioning of adult female sexual assault victims

- The use and effectiveness of psychological interventions in reducing recidivism among non-violent criminals

- The impact of domestic violence on the mental health and forensic evaluation of men

- Exploring the ethical considerations and use of behavioural analysis in the study of criminal behaviour

- The use and limitations of neuropsychological assessment in forensic evaluations

- The use of social media forensics in evaluating criminal behaviour in violent crimes

- The racialised use of psychological assessment in the evaluation of competency to stand trial in Canada

- Exploring the use and availability of virtual reality technologies in forensic psychology in Spain

- The impact of motivational interviewing-based interventions among criminalized drug users

Research Ideas: Social Psychology

- The impact of prejudice and discrimination on social behaviour among African immigrants in South Africa

- The impact of social networks on behaviour and well-being among young adult females

- The effects of social identity on non-conformity in University students

- The effects of group dynamics on risk-seeking behaviour in adult men

- The impact of social media on the quality of interpersonal relationships among high school learners

- The impact of parental emotional intelligence on pro-social behaviour in children and adolescents

- The effects of conformity and deviance on social attitudes and behaviour during a global recession

- The effects of Tik Tok on social comparison and self-esteem among teenage girls

- Understanding gendered differences in social influence and algorithms on impulsive decision-making

- The effects of social support on mental health among healthcare workers in the UK

- The effects of gender roles on social behaviour among trans teens

- The impact of perceived power and social status on the behaviour of social media influencers

- The impact of social norms on prosocial behaviour among women

- The effects of community participation on aggression and violence in middle-aged men

- The impact of culture and gender on social behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic

Research Ideas: Sports Psychology

- The moderating role of cultural factors on the relationship between mental health and sports performance in team sports

- The role of mindfulness practice in addressing stress and anxiety in young national athletes

- The relationship between team cohesion and performance in cricket teams

- The effect of transformational leadership on female sports teams in Canada

- The effect of positive self-talk on athletic performance and motivation among Olympic athletes

- The use and perception of hypnosis in New Zealand team sports Understanding stress and burnout in University team athletes

- The efficacy of personalised nutrition and diet on athletic performance among sprinters

- Exploring mental preparation techniques and their effect on athletic motivation and resilience among team-sport athletes

- Exploring the perception and understanding of goal-setting characteristics on athletic performance among team coaches

- The effects of motivational feedback on the performance of female gymnasts

- The perception and use of visualization and imagery among coaches as a means to enhance sport performance

- The impact of sports injuries on mental health and recovery in high school athletes

- The moderating role of sleep on mental toughness and sports performance in Olympic athletes

- The use and perception of technology in sports training and performance in little league softball

Psychology-Related Dissertations & Theses

While the ideas we’ve presented above are a decent starting point for finding a research topic in psychology, they are fairly generic and non-specific. So, it helps to look at actual dissertations and theses to see how this all comes together in practice.

Below, we’ve included a selection of research projects from various psychology degree programs to help refine your thinking. These are actual dissertations and theses, written as part of Master’s and PhD-level programs, so they can provide some useful insight as to what a research topic looks like in practice.

- Effects of a Patient Question Prompt List on Outpatient Palliative Care Appointments (McDarby, 2022)

- The role of affect and exercise goals in physical activity engagement in younger and older adults (Stojanovic, 2022)

- Lay Theories about Whether Emotion Helps or Hinders Reasoning and Well-being (Karnaze, 2022)

- The effects of blast-induced traumatic brain injury on two transgenic models of Alzheimer’s Disease (Gann, 2020)

- Understanding the parental mind: Examining the stability of parental reflective functioning across the birth of a child and associations with maternal mind-mindedness (Pitzen, 2021)

- An investigation of ineffective ally behaviours (Collier, 2019)

- Response Inhibition-Related Beta Power: Distinguishing Cognitively Intact Elders by Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease (Evans, 2021)

- Recognition Memory of Extremely High-Frequency Words (Miller, 2019)

- The Relationship between Dementia Caregiver Burden and Caregiver Communications in a Memory Clinic Setting (Martin, 2021)

- Examination of Maternal Versus Paternal Ratings of Child Pre-Injury Functioning in Predicting Child Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms (Sayer, 2021)

- Electromyography As A Means of Predicting The Rubber Hand Illusion (Teaford, 2021)

- Linking Diversity Climate and Feedback Seeking Through Interpersonal Processes and Race Effects (Flores, 2021)

Looking at these titles, you can probably pick up that the research topics here are far more specific and narrowly-focused , compared to the generic ones presented earlier. This is an important thing to keep in mind as you develop your own research topic. That is to say, to create a top-notch research topic, you must be precise and target a specific context with specific variables of interest . In other words, you need to identify a clear, well-justified research gap.

Fast-Track Your Topic Ideation

Still unsure about how to find the right topic for your research project? Check out our private coaching services , where we work with psychology students on a 1:1 basis to help them find the perfect topic.

You Might Also Like:

10 Comments

Great insight

A very interesting site that offers a variety of options regarding research topics.

You’re most welcome

A good platform to get information

Amazing and interesting options 👌

Very useful but had not any field of research in health psychology

I feel honored going through this lovely stuff put together. Thank you so much

I need counseling psychology research topics

very empowering and insightful presentations. Can I be assisted in crafting a school psychology-related research topic about African context

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Social Psychology Research Topics

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Choosing topics for social psychology research papers or projects for class can be challenging. It is a broad and fascinating field, which can make it challenging to figure out what you want to investigate in your research.

Social psychology explores how individual thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are affected by social influences. It explores how each person's behavior is affected by their social environment.

This article explores a few different social psychology topics and research questions you might want to study in greater depth. It covers how to start your search for a topic as well as specific ideas you might choose to explore.

How to Find a Social Psychology Research Topic

As you begin your search, think about the questions that you have. What topics interest you? Following your own interests and curiosities can often inspire great research questions.

Choose a Sub-Topic

Social psychologists are interested in all aspects of social behavior. Some of the main areas of interest within the field include social cognition, social influence, and social relationships investigating subtopics such as conformity, groupthink, attitude formation, obedience, prejudice, and so on.

- Social cognition : How do we process and use information about social experiences? What kinds of biases influence how we engage with other people?

- Social influence: What are the key social factors that influence our attitudes and behavior? What are group dynamics and how do we understand patterns of behavior in groups?

- Social relationships : What are the different types of social relationships? How do they develop and change over time?

To help ensure that you select a topic that is specific enough, it can be helpful to start by confining your search to one of these main areas.

Browse Through Past Research

After narrowing down your choices, consider what questions you might have. Are there questions that haven't been fully answered by previous studies? At this point, it can be helpful to spend some time browsing through journal articles or books to see some examples of past findings and identify gaps in the literature.

You can also find inspiration and learn more about a topic by searching for keywords related to your topic in psychological databases such as PsycINFO or browsing through some professional psychology journals.

Narrow Down Your Specific Topic

Once you have a general topic, you'll need to narrow down your research. The goal is to choose a research question that is specific, measurable, and testable. Let's say you want to study conformity; An example of a good research question might be, “Are people more likely to conform when they are in a small group or a large group?” In this case, the specific topic of your paper would be how group size influences social conformity .

Review the Literature on Your Chosen Topic

After choosing a specific social psychology topic to research, the next step is to do a literature review. A literature review involves reading through the existing research findings related to a specific topic.

You are likely to encounter a great deal of information on your topic, which can seem overwhelming at times. You may find it helpful to start by reading review articles or meta-analysis studies. These are summaries of previous research on your topic or studies that incorporate a large pool of past research on the topic.

Talk to Your Instructor

Even if you are really excited to dive right in and start working on your project, there are some important preliminary steps you need to take.

Before you decide to tackle a project for your social psychology class, you should always clear your idea with your instructor. This initial step can save you a lot of time and hassle later on.

Your instructor can offer clear feedback on things you should and should not do while conducting your research and might be able to offer some helpful tips. Also, if you plan to implement your own social experiment, your school might require you to present to and gain permission from an institutional review board.

Thinking about the questions you have about social psychology can be a great way to discover topics for your own research. Once you have a general idea, explore the literature and refine your research question to make sure it is specific enough.

Examples of Social Psychology Research Topics

The following are some specific examples of different subjects you might want to investigate further as part of a social psychology research paper, experiment, or project:

Implicit Attitudes

How do implicit attitudes influence how people respond to others? This can involve exploring how people's attitudes towards different groups of people (e.g., men, women, ethnic minorities) influence their interactions with those groups. For example, one study found that 75% of people perceive men to be more intelligent than women .

In your own project, you might explore how implicit attitudes impact perceptions of qualities such as kindness, intelligence, leadership skills, or attractiveness.

Prosocial Behavior

You might also choose to focus on prosocial behavior in your research. This can involve investigating the reasons why people help others. Some questions you could explore further include:

- What motivates people to help others?

- When are people most likely to help others?

- How does helping others cause people to feel?

- What are the benefits of helping other people?

How do people change their attitudes in response to persuasion? What are the different techniques that can be used to persuade someone? What factors make some people more susceptible to persuasion than others?

One way to investigate this could be through collecting a wide variety of print advertisements and analyzing how persuasion is used. What types of cognitive and affective techniques are utilized? Do certain types of advertisements tend to use specific kinds of persuasive techniques ?

Another area of social psychology that you might research is aggression and violence. This can involve exploring the factors that lead to aggression and violence and the consequences of these behaviors. Some questions you might explore further include:

- When is violence most likely to occur?

- What factors influence violent behavior?

- Do traumatic experiences in childhood lead to more aggressive behavior in adulthood?

- Does viewing violent media content contribute to increased aggressive behavior in real life?

Prejudice and discrimination are areas that present a range of research opportunities. This can involve studying the different forms that prejudice takes (e.g., sexism, racism, ageism ), as well as the psychological effects of prejudice and discrimination. You might also want to investigate topics related to how prejudices form or strategies that can be used to reduce such discrimination.

Nonverbal Behavior

How do people respond when nonverbal communication does not match up to verbal behavior (for example, saying you feel great when your facial expressions and tone of voice indicate otherwise). Which signal do people respond to most strongly?

How good are people at detecting lies ? Have participants tell a group of people about themselves, but make sure some of the things are true while others are not. Ask members of the group which statements they thought were true and which they thought were false.

Social Norms

How do people react when social norms are violated? This might involve acting in a way that is outside the norm in a particular situation or enlisting friends to act out the behaviors while you observe.

Some examples that you might try include wearing unusual clothing, applauding inappropriately at the end of a class lecture, cutting in line in front of other people, or some other mildly inappropriate behavior. Keep track of your own thoughts as you perform the experiment and observe how people around you respond.

Online Social Behavior

Does online social networking make people more or less likely to interact with people in face-to-face or other offline settings? To investigate this further, you could create a questionnaire to assess how often people participate in social networking versus how much time they spend interacting with their friends in real-world settings.

Social Perception

How does our appearance impact how people respond to us? Ask some friends to help you by having two people dress up in dramatically different ways, one in a professional manner and one in a less conventional manner. Have each person engage in a particular action, then observe how they are treated and how other people's responses differ.

Social psychologists have found that attractiveness can produce what is known as a halo effect . Essentially, we tend to assume that people who are physically attractive are also friendly, intelligent, pleasant, and likable.

To investigate this topic, you could set up an experiment where you have participants look at photographs of people of varying degrees of physical attractiveness, and then ask them to rate each person based on a variety of traits, including social competence, kindness, intellect, and overall likability.

Think about how this might affect a variety of social situations, including how employees are selected or how jurors in a criminal case might respond.

Social psychology is a broad field, so there are many different subtopics you might choose to explore in your research. Implicit attitudes, prosocial behavior, aggression, prejudice, and social perception are just a few areas you might want to consider.

A Word From Verywell

Social psychology topics can provide a great deal of inspiration for further research, whether you are writing a research paper or conducting your own experiment. In addition to some of the social psychology topics above, you can also draw inspiration from your own curiosity about social behavior or examine social issues that you see taking place in the world around you.

American Psychological Association. Frequently asked questions about institutional review boards .

Storage D, Charlesworth TES, Banaji M, Cimpian A. Adults and children implicitly associate brilliance with men more than women . J Exp Soc Psychol . 2012;90:104020. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2020.104020

Talamas SN, Mavor KI, Perrett DI. Blinded by beauty: Attractiveness bias and accurate perceptions of academic performance . PLoS ONE . 2016;11(2):e0148284. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148284

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Overview of the Scientific Method

8 Finding a Research Topic

Learning objectives.

- Learn some common sources of research ideas.

- Define the research literature in psychology and give examples of sources that are part of the research literature and sources that are not.

- Describe and use several methods for finding previous research on a particular research idea or question.

Good research must begin with a good research question. Yet coming up with good research questions is something that novice researchers often find difficult and stressful. One reason is that this is a creative process that can appear mysterious—even magical—with experienced researchers seeming to pull interesting research questions out of thin air. However, psychological research on creativity has shown that it is neither as mysterious nor as magical as it appears. It is largely the product of ordinary thinking strategies and persistence (Weisberg, 1993) [1] . This section covers some fairly simple strategies for finding general research ideas, turning those ideas into empirically testable research questions, and finally evaluating those questions in terms of how interesting they are and how feasible they would be to answer.

Finding Inspiration

Research questions often begin as more general research ideas—usually focusing on some behavior or psychological characteristic: talkativeness, learning, depression, bungee jumping, and so on. Before looking at how to turn such ideas into empirically testable research questions, it is worth looking at where such ideas come from in the first place. Three of the most common sources of inspiration are informal observations, practical problems, and previous research.

Informal observations include direct observations of our own and others’ behavior as well as secondhand observations from non-scientific sources such as newspapers, books, blogs, and so on. For example, you might notice that you always seem to be in the slowest moving line at the grocery store. Could it be that most people think the same thing? Or you might read in a local newspaper about people donating money and food to a local family whose house has burned down and begin to wonder about who makes such donations and why. Some of the most famous research in psychology has been inspired by informal observations. Stanley Milgram’s famous research on obedience to authority, for example, was inspired in part by journalistic reports of the trials of accused Nazi war criminals—many of whom claimed that they were only obeying orders. This led him to wonder about the extent to which ordinary people will commit immoral acts simply because they are ordered to do so by an authority figure (Milgram, 1963) [2] .

Practical problems can also inspire research ideas, leading directly to applied research in such domains as law, health, education, and sports. Does taking lecture notes by hand improve students’ exam performance? How effective is psychotherapy for depression compared to drug therapy? To what extent do cell phones impair people’s driving ability? How can we teach children to read more efficiently? What is the best mental preparation for running a marathon?

Probably the most common inspiration for new research ideas, however, is previous research. Recall that science is a kind of large-scale collaboration in which many different researchers read and evaluate each other’s work and conduct new studies to build on it. Of course, experienced researchers are familiar with previous research in their area of expertise and probably have a long list of ideas. This suggests that novice researchers can find inspiration by consulting with a more experienced researcher (e.g., students can consult a faculty member). But they can also find inspiration by picking up a copy of almost any professional journal and reading the titles and abstracts. In one typical issue of Psychological Science , for example, you can find articles on the perception of shapes, anti-Semitism, police lineups, the meaning of death, second-language learning, people who seek negative emotional experiences, and many other topics. If you can narrow your interests down to a particular topic (e.g., memory) or domain (e.g., health care), you can also look through more specific journals, such as Memory & Cognition or Health Psychology .

Reviewing the Research Literature

Once again, one of the most common sources of inspiration is previous research. Therefore, it is important to review the literature early in the research process. The research literature in any field is all the published research in that field. Reviewing the research literature means finding, reading, and summarizing the published research relevant to your topic of interest. In addition to helping you discover new research questions, reviewing the literature early in the research process can help you in several other ways.

- It can tell you if a research question has already been answered.

- It can help you evaluate the interestingness of a research question.

- It can give you ideas for how to conduct your own study.

- It can tell you how your study fits into the research literature.

The research literature in psychology is enormous—including millions of scholarly articles and books dating to the beginning of the field—and it continues to grow. Although its boundaries are somewhat fuzzy, the research literature definitely does not include self-help and other pop psychology books, dictionary and encyclopedia entries, websites, and similar sources that are intended mainly for the general public. These are considered unreliable because they are not reviewed by other researchers and are often based on little more than common sense or personal experience. Wikipedia contains much valuable information, but because its authors are anonymous and may not have any formal training or expertise in that subject area, and its content continually changes it is unsuitable as a basis of sound scientific research. For our purposes, it helps to define the research literature as consisting almost entirely of two types of sources: articles in professional journals, and scholarly books in psychology and related fields.

Professional Journals

Professional journals are periodicals that publish original research articles. There are thousands of professional journals that publish research in psychology and related fields. They are usually published monthly or quarterly in individual issues, each of which contains several articles. The issues are organized into volumes, which usually consist of all the issues for a calendar year. Some journals are published in hard copy only, others in both hard copy and electronic form, and still others in electronic form only.

Most articles in professional journals are one of two basic types: empirical research reports and review articles. Empirical research reports describe one or more new empirical studies conducted by the authors. They introduce a research question, explain why it is interesting, review previous research, describe their method and results, and draw their conclusions. Review articles summarize previously published research on a topic and usually present new ways to organize or explain the results. When a review article is devoted primarily to presenting a new theory, it is often referred to as a theoretical article . When a review article provides a statistical summary of all of the previous results it is referred to as a meta-analysis .

Most professional journals in psychology undergo a process of double-blind peer review . Researchers who want to publish their work in the journal submit a manuscript to the editor—who is generally an established researcher too—who in turn sends it to two or three experts on the topic. Each reviewer reads the manuscript, writes a critical but constructive review, and sends the review back to the editor along with recommendations about whether the manuscript should be published or not. The editor then decides whether to accept the article for publication, ask the authors to make changes and resubmit it for further consideration, or reject it outright. In any case, the editor forwards the reviewers’ written comments to the researchers so that they can revise their manuscript accordingly. This entire process is double-blind, as the reviewers do not know the identity of the researcher(s) and vice versa. Double-blind peer review is helpful because it ensures that the work meets basic standards of the field before it can enter the research literature. However, in order to increase transparency and accountability, some newer open access journals (e.g., Frontiers in Psychology ) utilize an open peer review process wherein the identities of the reviewers (which remain concealed during the peer review process) are published alongside the journal article.

Scholarly Books

Scholarly books are books written by researchers and practitioners mainly for use by other researchers and practitioners. A monograph is written by a single author or a small group of authors and usually, gives a coherent presentation of a topic much like an extended review article. Edited volumes have an editor or a small group of editors who recruit many authors to write separate chapters on different aspects of the same topic. Although edited volumes can also give a coherent presentation of the topic, it is not unusual for each chapter to take a different perspective or even for the authors of different chapters to openly disagree with each other. In general, scholarly books undergo a peer review process similar to that used by professional journals.

Literature Search Strategies

Using psycinfo and other databases.

The primary method used to search the research literature involves using one or more electronic databases. These include Academic Search Premier, JSTOR, and ProQuest for all academic disciplines, ERIC for education, and PubMed for medicine and related fields. The most important for our purposes, however, is PsycINFO, which is produced by the American Psychological Association (APA). PsycINFO is so comprehensive—covering thousands of professional journals and scholarly books going back more than 100 years—that for most purposes its content is synonymous with the research literature in psychology. Like most such databases, PsycINFO is usually available through your university library.

PsycINFO consists of individual records for each article, book chapter, or book in the database. Each record includes basic publication information, an abstract or summary of the work (like the one presented at the start of this chapter), and a list of other works cited by that work. A computer interface allows entering one or more search terms and returns any records that contain those search terms. (These interfaces are provided by different vendors and therefore can look somewhat different depending on the library you use.) Each record also contains lists of keywords that describe the content of the work and also a list of index terms. The index terms are especially helpful because they are standardized. Research on differences between females and males, for example, is always indexed under “Human Sex Differences.” Research on note-taking is always indexed under the term “Learning Strategies.” If you do not know the appropriate index terms, PsycINFO includes a thesaurus that can help you find them.

Given that there are nearly four million records in PsycINFO, you may have to try a variety of search terms in different combinations and at different levels of specificity before you find what you are looking for. Imagine, for example, that you are interested in the question of whether males and females differ in terms of their ability to recall experiences from when they were very young. If you were to enter the search term “memory,” it would return far too many records to look through individually. This is where the thesaurus helps. Entering “memory” into the thesaurus provides several more specific index terms—one of which is “early memories.” While searching for “early memories” among the index terms still returns too many to look through individually—combining it with “human sex differences” as a second search term returns fewer articles, many of which are highly relevant to the topic.

Depending on the vendor that provides the interface to PsycINFO, you may be able to save, print, or e-mail the relevant PsycINFO records. The records might even contain links to full-text copies of the works themselves. (PsycARTICLES is a database that provides full-text access to articles in all journals published by the APA.) If not, and you want a copy of the work, you will have to find out if your library carries the journal or has the book and the hard copy on the library shelves. Be sure to ask a librarian if you need help.

Using Other Search Techniques

In addition to entering search terms into PsycINFO and other databases, there are several other techniques you can use to search the research literature. First, if you have one good article or book chapter on your topic—a recent review article is best—you can look through the reference list of that article for other relevant articles, books, and book chapters. In fact, you should do this with any relevant article or book chapter you find. You can also start with a classic article or book chapter on your topic, find its record in PsycINFO (by entering the author’s name or article’s title as a search term), and link from there to a list of other works in PsycINFO that cite that classic article. This works because other researchers working on your topic are likely to be aware of the classic article and cite it in their own work. You can also do a general Internet search using search terms related to your topic or the name of a researcher who conducts research on your topic. This might lead you directly to works that are part of the research literature (e.g., articles in open-access journals or posted on researchers’ own websites). The search engine Google Scholar is especially useful for this purpose. A general Internet search might also lead you to websites that are not part of the research literature but might provide references to works that are. Finally, you can talk to people (e.g., your instructor or other faculty members in psychology) who know something about your topic and can suggest relevant articles and book chapters.

What to Search For

When you do a literature review, you need to be selective. Not every article, book chapter, and book that relates to your research idea or question will be worth obtaining, reading, and integrating into your review. Instead, you want to focus on sources that help you do four basic things: (a) refine your research question, (b) identify appropriate research methods, (c) place your research in the context of previous research, and (d) write an effective research report. Several basic principles can help you find the most useful sources.

First, it is best to focus on recent research, keeping in mind that what counts as recent depends on the topic. For newer topics that are actively being studied, “recent” might mean published in the past year or two. For older topics that are receiving less attention right now, “recent” might mean within the past 10 years. You will get a feel for what counts as recent for your topic when you start your literature search. A good general rule, however, is to start with sources published in the past five years. The main exception to this rule would be classic articles that turn up in the reference list of nearly every other source. If other researchers think that this work is important, even though it is old, then, by all means, you should include it in your review.

Second, you should look for review articles on your topic because they will provide a useful overview of it—often discussing important definitions, results, theories, trends, and controversies—giving you a good sense of where your own research fits into the literature. You should also look for empirical research reports addressing your question or similar questions, which can give you ideas about how to measure your variables and collect your data. As a general rule, it is good to use methods that others have already used successfully unless you have good reasons not to. Finally, you should look for sources that provide information that can help you argue for the interestingness of your research question. For a study on the effects of cell phone use on driving ability, for example, you might look for information about how widespread cell phone use is, how frequent and costly motor vehicle crashes are, and so on.

How many sources are enough for your literature review? This is a difficult question because it depends on how extensively your topic has been studied and also on your own goals. One study found that across a variety of professional journals in psychology, the average number of sources cited per article was about 50 (Adair & Vohra, 2003) [3] . This gives a rough idea of what professional researchers consider to be adequate. As a student, you might be assigned a much lower minimum number of references to include, but the principles for selecting the most useful ones remain the same.

Video Attributions

- “ How to Develop a Good Research Topic ” by KStateLibraries . CC BY (Attribution)

- “ Sample PsycINFO Search on EBSCOhost ” by APA Publishing Training . Standard YouTube Licence.

- “ Using Google Scholar (CLIP) ” by clipinfolit . CC BY (Attribution)

- Weisberg, R. W. (1993). Creativity: Beyond the myth of genius . New York, NY: Freeman. ↵

- Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67 , 371–378. ↵

- Adair, J. G., & Vohra, N. (2003). The explosion of knowledge, references, and citations: Psychology’s unique response to a crisis. American Psychologist, 58 , 15–23. ↵

All the published research in that field.

Are periodicals that publish original research articles.

Research reports that describe one or more new empirical studies conducted by the authors.

Articles that summarize previously published research on a topic and usually present new ways to organize or explain the results.

A review article that is devoted primarily to presenting a new theory.

A review article that provides a statistical summary of all of the previous results.

A process in which the reviewers of a research article do not know the identity of the researcher(s) and vice versa.

Books written by researchers and practitioners mainly for use by other researchers and practitioners.

A coherent written presentation of a topic much like an extended review article written by a single author or a small group of authors.

Books that are collections of chapters written by different authors on different aspects of the same topic, and overseen by one or more editors.

A comprehensive electronic database covering thousands of professional journals and scholarly books going back more than 100 years—that for most purposes its content is synonymous with the research literature in psychology.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

2.2 Finding a Research Topic

Learning objectives.

- Learn some common sources of research ideas.

- Define the research literature in psychology and give examples of sources that are part of the research literature and sources that are not.

- Describe and use several methods for finding previous research on a particular research idea or question.

Good research must begin with a good research question. Yet coming up with good research questions is something that novice researchers often find difficult and stressful. One reason is that this is a creative process that can appear mysterious—even magical—with experienced researchers seeming to pull interesting research questions out of thin air. However, psychological research on creativity has shown that it is neither as mysterious nor as magical as it appears. It is largely the product of ordinary thinking strategies and persistence (Weisberg, 1993) [1] . This section covers some fairly simple strategies for finding general research ideas, turning those ideas into empirically testable research questions, and finally evaluating those questions in terms of how interesting they are and how feasible they would be to answer.

Finding Inspiration

Research questions often begin as more general research ideas—usually focusing on some behavior or psychological characteristic: talkativeness, learning, depression, bungee jumping, and so on. Before looking at how to turn such ideas into empirically testable research questions, it is worth looking at where such ideas come from in the first place. Three of the most common sources of inspiration are informal observations, practical problems, and previous research.

Informal observations include direct observations of our own and others’ behavior as well as secondhand observations from non-scientific sources such as newspapers, books, blogs, and so on. For example, you might notice that you always seem to be in the slowest moving line at the grocery store. Could it be that most people think the same thing? Or you might read in a local newspaper about people donating money and food to a local family whose house has burned down and begin to wonder about who makes such donations and why. Some of the most famous research in psychology has been inspired by informal observations. Stanley Milgram’s famous research on obedience to authority, for example, was inspired in part by journalistic reports of the trials of accused Nazi war criminals—many of whom claimed that they were only obeying orders. This led him to wonder about the extent to which ordinary people will commit immoral acts simply because they are ordered to do so by an authority figure (Milgram, 1963) [2] .

Practical problems can also inspire research ideas, leading directly to applied research in such domains as law, health, education, and sports. Does taking lecture notes by hand improve students’ exam performance? How effective is psychotherapy for depression compared to drug therapy? To what extent do cell phones impair people’s driving ability? How can we teach children to read more efficiently? What is the best mental preparation for running a marathon?

Reading in print? Scan this QR code to view the video on your mobile device. Or go to https://youtu.be/nXNztCLYgxc

Probably the most common inspiration for new research ideas, however, is previous research. Recall that science is a kind of large-scale collaboration in which many different researchers read and evaluate each other’s work and conduct new studies to build on it. Of course, experienced researchers are familiar with previous research in their area of expertise and probably have a long list of ideas. This suggests that novice researchers can find inspiration by consulting with a more experienced researcher (e.g., students can consult a faculty member). But they can also find inspiration by picking up a copy of almost any professional journal and reading the titles and abstracts. In one typical issue of Psychological Science , for example, you can find articles on the perception of shapes, anti-Semitism, police lineups, the meaning of death, second-language learning, people who seek negative emotional experiences, and many other topics. If you can narrow your interests down to a particular topic (e.g., memory) or domain (e.g., health care), you can also look through more specific journals, such as Memory & Cognition or Health Psychology .

Reviewing the Research Literature

Once again, one of the most common sources of inspiration is previous research. Therefore, it is important to review the literature early in the research process. Reviewing the research literature means finding, reading, and summarizing the published research relevant to your topic of interest. In addition to helping you discover new research questions, reviewing the literature early in the research process can help you in several other ways.

- It can tell you if a research question has already been answered.

- It can help you evaluate the interestingness of a research question.

- It can give you ideas for how to conduct your own study.

- It can tell you how your study fits into the research literature.

The research literature in any field is all the published research in that field. The research literature in psychology is enormous—including millions of scholarly articles and books dating to the beginning of the field—and it continues to grow. Although its boundaries are somewhat fuzzy, the research literature definitely does not include self-help and other pop psychology books, dictionary and encyclopedia entries, websites, and similar sources that are intended mainly for the general public. These are considered unreliable because they are not reviewed by other researchers and are often based on little more than common sense or personal experience. Wikipedia contains much valuable information, but the fact that its authors are anonymous and may not have any formal training or expertise in that subject area, and its content continually changes makes it unsuitable as a basis of sound scientific research. For our purposes, it helps to define the research literature as consisting almost entirely of two types of sources: articles in professional journals, and scholarly books in psychology and related fields.

Professional Journals

Professional journals are periodicals that publish original research articles. There are thousands of professional journals that publish research in psychology and related fields. They are usually published monthly or quarterly in individual issues, each of which contains several articles. The issues are organized into volumes, which usually consist of all the issues for a calendar year. Some journals are published in hard copy only, others in both hard copy and electronic form, and still others in electronic form only.

Most articles in professional journals are one of two basic types: empirical research reports and review articles. Empirical research reports describe one or more new empirical studies conducted by the authors. They introduce a research question, explain why it is interesting, review previous research, describe their method and results, and draw their conclusions. Review articles summarize previously published research on a topic and usually present new ways to organize or explain the results. When a review article is devoted primarily to presenting a new theory, it is often referred to as a theoretical article .

Figure 2.2 Small Sample of the Thousands of Professional Journals That Publish Research in Psychology and Related Fields

Most professional journals in psychology undergo a process of double-blind peer review . Researchers who want to publish their work in the journal submit a manuscript to the editor—who is generally an established researcher too—who in turn sends it to two or three experts on the topic. Each reviewer reads the manuscript, writes a critical but constructive review, and sends the review back to the editor along with his or her recommendations. The editor then decides whether to accept the article for publication, ask the authors to make changes and resubmit it for further consideration, or reject it outright. In any case, the editor forwards the reviewers’ written comments to the researchers so that they can revise their manuscript accordingly. This entire process is double-blind, as the reviewers do not know the identity of the researcher(s) and vice versa. Double-blind peer review is helpful because it ensures that the work meets basic standards of the field before it can enter the research literature. However, in order to increase transparency and accountability, some newer open access journals (e.g., Frontiers in Psychology) utilize an open peer review process wherein the identities of the reviewers (which remain concealed during the peer review process) are published alongside the journal article.

Scholarly Books

Scholarly books are books written by researchers and practitioners mainly for use by other researchers and practitioners. A monograph is written by a single author or a small group of authors and usually, gives a coherent presentation of a topic much like an extended review article. Edited volumes have an editor or a small group of editors who recruit many authors to write separate chapters on different aspects of the same topic. Although edited volumes can also give a coherent presentation of the topic, it is not unusual for each chapter to take a different perspective or even for the authors of different chapters to openly disagree with each other. In general, scholarly books undergo a peer review process similar to that used by professional journals.

Literature Search Strategies

Using psycinfo and other databases.

The primary method used to search the research literature involves using one or more electronic databases. These include Academic Search Premier, JSTOR, and ProQuest for all academic disciplines, ERIC for education, and PubMed for medicine and related fields. The most important for our purposes, however, is PsycINFO, which is produced by the American Psychological Association (APA). PsycINFO is so comprehensive—covering thousands of professional journals and scholarly books going back more than 100 years—that for most purposes its content is synonymous with the research literature in psychology. Like most such databases, PsycINFO is usually available through your university library.

PsycINFO consists of individual records for each article, book chapter, or book in the database. Each record includes basic publication information, an abstract or summary of the work (like the one presented at the start of this chapter), and a list of other works cited by that work. A computer interface allows entering one or more search terms and returns any records that contain those search terms. (These interfaces are provided by different vendors and therefore can look somewhat different depending on the library you use.) Each record also contains lists of keywords that describe the content of the work and also a list of index terms. The index terms are especially helpful because they are standardized. Research on differences between women and men, for example, is always indexed under “Human Sex Differences.” Research on note-taking is always indexed under the term “Learning Strategies.” If you do not know the appropriate index terms, PsycINFO includes a thesaurus that can help you find them.

Given that there are nearly four million records in PsycINFO, you may have to try a variety of search terms in different combinations and at different levels of specificity before you find what you are looking for. Imagine, for example, that you are interested in the question of whether women and men differ in terms of their ability to recall experiences from when they were very young. If you were to enter “memory for early experiences” as your search term, PsycINFO would return only six records, most of which are not particularly relevant to your question. However, if you were to enter the search term “memory,” it would return 149,777 records—far too many to look through individually. This is where the thesaurus helps. Entering “memory” into the thesaurus provides several more specific index terms—one of which is “early memories.” While searching for “early memories” among the index terms returns 1,446 records—still too many to look through individually—combining it with “human sex differences” as a second search term returns 37 articles, many of which are highly relevant to the topic.

Reading in print? Scan this QR code to view the video on your mobile device. Or go to https://youtu.be/fhhctbaVXvk

Depending on the vendor that provides the interface to PsycINFO, you may be able to save, print, or e-mail the relevant PsycINFO records. The records might even contain links to full-text copies of the works themselves. (PsycARTICLES is a database that provides full-text access to articles in all journals published by the APA.) If not, and you want a copy of the work, you will have to find out if your library carries the journal or has the book and the hard copy on the library shelves. Be sure to ask a librarian if you need help.

Using Other Search Techniques

Reading in print? Scan this QR code to view the video on your mobile device. Or go to https://youtu.be/t1ZwgDeX2eQ

In addition to entering search terms into PsycINFO and other databases, there are several other techniques you can use to search the research literature. First, if you have one good article or book chapter on your topic—a recent review article is best—you can look through the reference list of that article for other relevant articles, books, and book chapters. In fact, you should do this with any relevant article or book chapter you find. You can also start with a classic article or book chapter on your topic, find its record in PsycINFO (by entering the author’s name or article’s title as a search term), and link from there to a list of other works in PsycINFO that cite that classic article. This works because other researchers working on your topic are likely to be aware of the classic article and cite it in their own work. You can also do a general Internet search using search terms related to your topic or the name of a researcher who conducts research on your topic. This might lead you directly to works that are part of the research literature (e.g., articles in open-access journals or posted on researchers’ own websites). The search engine Google Scholar is especially useful for this purpose. A general Internet search might also lead you to websites that are not part of the research literature but might provide references to works that are. Finally, you can talk to people (e.g., your instructor or other faculty members in psychology) who know something about your topic and can suggest relevant articles and book chapters.

What to Search For

When you do a literature review, you need to be selective. Not every article, book chapter, and book that relates to your research idea or question will be worth obtaining, reading, and integrating into your review. Instead, you want to focus on sources that help you do four basic things: (a) refine your research question, (b) identify appropriate research methods, (c) place your research in the context of previous research, and (d) write an effective research report. Several basic principles can help you find the most useful sources.