- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Religion in schools in the united states.

- Suzanne Rosenblith Suzanne Rosenblith Clemson University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.46

- Published online: 28 June 2017

The relationship between religion and public education has been fraught with misunderstanding, confusion, tension, and hostility. Perhaps more so than other forms of identity, for many, religion evokes a strong sense of exclusivity. Unlike other forms of identity, for many, particularly the religiously orthodox, religious identity is based on a belief in absolute truth. And for some of the orthodox, adherence to this truth is central to their salvation. Further, unlike cultural identity, religion is oftentimes exclusive in its fundamental claims and assertions. In short, matters of religious faith are indeed high stakes. Yet its treatment in public schools is, for the most part, relatively scant. Some of this is because of uncertainty among educators as to what the law permits, and for others it is uncertainty of its rightful place in democratic pluralistic schools.

- public education

- first amendment

Introduction

This article seeks to provide an overview of the historical, legal, and curricular relationship between religion and public schooling in the United States. This relationship, often fraught with tension, attempts to reconcile often incommensurable public goals. The article begins with a review of the history of religion in the public domain. Since public schools are often thought of as microcosms of society, it is important to understand the relationship of religion within society. Following this overview, the article delves more deeply into seminal court cases that have more or less cemented the legal constraints of religion in public education. With legal parameters in mind, the next section explores the relationship of religion in public schools from curricular perspectives. Moving beyond a discussion of creationism in science class, this section aims to examine the benefits of broader inclusion of religious perspectives as a way to approximate pluralistic and democratic schools. The final section explores broader concerns for a liberal democracy—pluralism, autonomy, and respect—as it wrestles with the appropriateness of religion and religious identity in public schools.

History of Religion in the Public Sphere

To understand the contemporary relationship between religion and public schooling requires a review of the history of religion in the public sphere. Many schoolchildren in the United States have been taught that the first European settlers to the colonies fled Europe and the Church of England to seek freedom to exercise their religious beliefs. And while this is true, far from the feel-good narrative that some like to extend (Baritz, 1964 ), the first settlers, the Puritans, were an extremely rigid and dogmatic group of religious believers who settled in the colonies not for freedom of religion but to practice and entrench their religious beliefs (Kaveny, 2013 ). They did not believe in a secular state but rather believed their version of Christianity to be predominant, and as far as they could see, the only justifiable established religion (Fiske, 1889 ). The Puritans believed Satan lurked around every corner and that religion was the essential tool to ward off Satan’s trickery. This in fact was the basis for the 1647 Old Deluder Satan Act (Constitution Society, 1647 ).

Common School Movement

As time progressed after the American Revolution, leaders like Horace Mann and Benjamin Rush made calls for a more organized public school system (Rudolph, 1965 ). Horace Mann famously called for the creation of the Common School (Hinsdale, 1898 ). Though Mann grew up, like so many, in a deeply religious home, he did not think these new public schools needed to be centrally religious. That is, their focus was not to be on inculcating biblical views, but rather for Mann, the focus of the Common School was to cultivate a tolerant, what we might call today, pluralistic, citizenry (Mann & Massachusetts Board of Education, 1957 ). Morality, more so than literal scriptural reading, was what Mann called for. For Mann, the chief concern in creating this Common School was attending to the increasing social strife that came as a result of the development of industry (Mann, 1965 ). Further, Mann was concerned about racial/ethnic hostility as the newest waves of immigrants to the United States were from Southern and Eastern Europe. Not only did they look different than the Northern and Western European immigrants, but they came with different languages, customs, and cultures. Assimilating them into a decidedly American culture was a goal for Mann and his allies (Hayes, 2006 ). All in all, the most orthodox religious believers were supportive of Mann’s efforts because these common schools exuded what was considered a nondenominational Protestantism (Moore, 2000 ). On the one hand was the belief that if you wanted the kind of hard-working, morally upright, conscientious citizens, then religion necessarily needed to be a part of the Common School. On the other hand, the religion that was foundational to the school did not need to be sectarian so as to privilege one group to the exclusion of others.

And so the Common School and then the Public School very much functioned with a role for religion—in many/most states, the school day began with a biblical recitation. In many schools, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries , McGuffey Readers were the main textbook (Westerhoff, 1978 ). The Readers , unlike their predecessor the New England Primer , mirrored this nondenominational Protestantism by inculcating morality through a veiled Christianity as opposed to a direct and overt use of the King James Bible in efforts to educate young citizens to become literate. For example, the New England Primer had a solemn prayer to be recited everyday, which states, “Oh Lord God, I beseech thee, of thy fatherly goodness and mercy to pardon all my offenses which in though, word, or deed, I have this day committed against thee and thy holy law” ( The New England Primer , 1805 ). The McGuffey Reader , in comparison, invoked a more nondenominational, less orthodox, religious tone. In one of its lessons it states, “I hope you have said your prayers and thanked your Father in Heaven for all his goodness … for your good health, and a blessing of home” (McGuffey, 1836 ).

Modernization and Industrialization

A significant, some might argue fatal, shift for those advocating the centrality of religion to public schools came in the early mid- 20th century . As has always been the case, public schools, serving as microcosms of society, reflect not just the dominant values and ethos of society, but also serve an important economic and intellectual purpose. That is, to the degree that the needs of society change, so must the public schools. Public schools were the central place to prepare the young for future citizenship. While an important part of that citizenship was moral and social, increasingly with industrialization, that role was also intellectual and economic (Fraser, 2001 ). The frame through which public schools cultivated curriculum changed substantially. For example, the type of citizen and future worker needed expanded from someone who was morally upright to someone who could contribute to the burgeoning Scientific and Industrial Revolutions. Shifting from the absolutism and fixidity of religion to the flexibility and tentativeness of science required a rethinking of pedagogy and curriculum (Greene, 2012 ). Further, with the country’s religious diversity increasing and the country itself maturing, religion seemed to be less central to the public schools. In contrast, understanding that ethical decision-making required an understanding of the context in which a person might find herself as opposed to the absolutes favored by religious belief, required a more open-ended, what today we might call, critical reasoning approach, to teaching and learning (Sears & Carper, 1998 ). The idea that the world was not absolute and fixed but ever changing, caused a real need for a different sort of education. As nondenominational Protestantism lost its stronghold over public schools in favor of a more science-focused secularism, Christian Orthodox—the Evangelical—become its harshest critics. They argue that the removal of God (religion) from the public sphere is a threat to their faith and a violation of their rights (Larson, 1997 ). Court cases related to religion and public education seem to lend some credence to their claims. The tension between the religiously orthodox, specifically evangelical Christians, and the secular public schools began in the mid- 20th century and has persisted to the present day (Deckman, 2004 ).

To survey popular media, particularly cable news, one might depict the current state of tension between those advocating for more religion in public schools and those advocating for its removal in the following way. On the one hand you have religious zealots making calls for prayer, creationism, released time, religious clubs, posting the Ten Commandments (Rogers, 2010 ; Shreve, 2010 ) and to the other extreme you have atheist zealots who refuse to consider any idea that has some association with religion as appropriate for public schools (Hedges, 2008 ). While these caricatures might fit some in each of these groups, contrary to the popular media depiction is, instead, a conflict built upon a reliance on different aspects of the first part of the First Amendment. That is, those advocating for more religion in public schools cite the “Free Exercise Clause” as the basis for their demands (Hodgson, 2004 ), while those arguing for a relatively “religious free public school” argue that anything less than this would be an instantiation of government support or “Establishment” of religion (Long, 2012 ). Given this, it is important to understand the legal context in which these tensions arise.

Religion and the Law

Perspectives on establishment.

The first part of the first amendment to the U.S. Constitution reads, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof” (U.S. Const. amend. I). The establishment clause , as it is commonly called, is meant to protect individuals from the establishment of an official state religion. In contrast, the function of the free exercise clause is to protect individual religious freedom. In terms of legal impact, the establishment clause has historically garnered more attention because of the wide-sweeping impact a legal decision will have. In contrast, free exercise cases address issues that pertain largely to religious minorities, so the impact is smaller and more context dependent.

Typically, when justices decide Establishment Clause cases they are asked to determine whether an enactment effectively establishes, or supports, a state religion. There are generally three different judicial perspectives on establishment, strict separation, accommodation, and neutral separation. Strict separationists invoke the idea of a wall separating Church and State. For strict separationists there is no instance in which an enactment would be tolerated (Neuhaus, 2007 ). Accommodationists point to the Framers’ “original intent” and argue that the only thing the Framers were concerned about in terms of the role of religion in government was the establishment of an official State Church. Barring this, certain accommodations are permissible as long as government does not prefer one religion to another (Massaro, 2005 ). Finally, the neutral separation position examines enactments with a slightly different lens arguing that what is most important is official State neutrality between religion and non-religion and thus argue that to adhere to the establishment clause may mean at times accommodating religion if it is to maintain neutrality between religion and non-religion (Fox, 2011 ; Temperman, 2010 ). Generally speaking, when focusing on the major court cases that have impacted public education, the neutral separation position has carried the day when it comes to issues such as school prayer, religious instruction, and released time.

Immediately following the Civil War, Congress passed the 14th amendment that states, “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States … ” What this means is one’s national citizenship is one’s highest source of rights. The degree to which state laws contradict federal/constitutional laws, state laws must give way. For our discussion this is important because it is the application of the 14th amendment to the 1st amendment that holds public schools and public school employees to the restrictions of the 1st amendment ( Everson v. Board of Education ). The 14th amendment application to the 1st amendment is also essential since it is the states, rather than the federal government, that hold substantive influence over public school curriculum and policy.

Several watershed cases have firmly established the preference for the neutral separation position. In McCollum v. Board of Education ( 1948 ), the court struck down an Illinois program that provided time during the school day on school premises for “released time” for religious instruction. Arguing that school personnel were involved with the administration and execution of this program was tantamount to supporting religion it was found unconstitutional. In contrast, the courts sided with the school district in Zorach v. Clauson ( 1952 ) where students were released from the school premises (with parental permission) during the school day for religious instruction arguing that it was the school’s job to maintain neutrality between religion and non-religion, and since it was the parents and students who voluntarily signed up for the released time program, the school did not violate the establishment clause by permitting such a program to continue.

Key Court Cases

In the middle of the 20th century it was commonplace for the school day to begin with a religious prayer or invocation. Beginning in 1962 , cases made their way through the courts, and in every instance the court found such prayers violated the establishment clause. Engel v. Vitale ( 1962 ) concerned a New York State Board of Regents Prayer that was to be read over the intercom system in every New York public school at the start of each school day, “Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers, and our country. Amen.” The court ruled that the prayer violated the establishment clause because although, nondenominational (in a sense), it still favored religion over non-religion. Further, because the prayer was broadcast at the start of the school day, students had no choice (captive audience) but to listen. The following year, the court in an 8-1 decision in Abington School District v. Schempp ( 1963 ) determined that a commonwealth of Pennsylvania law that read, “Ten verses from the Holy Bible shall be read without comment at the opening of each public school on each school day” was unconstitutional. Of greater importance in this case was the distinction made between the unconstitutionality of practicing religion in public school with the constitutionally permissible act of studying religion in public school. That is, if there is an educational purpose to studying religion, then presumably this would be permissible. The fact that the law included the clause “without comment” made it appear to the majority of justices that it served a devotional, rather than an educational, purpose. The second significance of this case is that it offered the first two of what later became a three-prong test used to adjudicate Establishment clause cases. The first prong asks what is the primary purpose of the enactment? Is it religious or secular? The second prong asks what is the primary effect of the enactment—religious or secular? In cases where the primary purpose and effect are secular the enactment is said to be permissible. This formula is particularly useful when determining whether curriculum, such as evolution or creationism, for example, is permitted. Epperson v. Arkansas ( 1968 ) addressed the matter of an Arkansas law prohibiting the teaching of evolution. The law was ruled unconstitutional on the grounds that the primary purpose of the law was to advance and protect a religious view. Following the Epperson decision was the famous case Lemon v. Kurtzman ( 1971 ). It was famous mainly because of the establishment of the third prong used to adjudicate establishment clause cases. At issue in this case was the question of whether public schools could reimburse private schools for the salaries of their teachers who taught secular subjects. Since the majority of the private schools were parochial, the matter fell under establishment. In deciding that it was unconstitutional for the public schools to pay the salaries of the parochial school teachers, the court determined that while primary purpose and primary effect were central to deciding constitutionality, a third prong, which says that the enactment must not foster an excessive entanglement between religion and government was needed. Paying the salaries of private school teachers who teach secular subjects may not serve a primarily religious purpose or have a primarily religious effect, but it certainly would foster an excessive entanglement between government and religion in that government would be very involved with accounting for their investments in a parochial school.

Contemporary Tensions

Other important Establishment Clause cases related to education include Wallace v. Jaffree ( 1985 ). This case dealt with the constitutionality of moments of silence. In this case, the state of Alabama allowed for a moment of silence for the purpose of meditation or private prayer. While moments of silence with no explicit purpose have been found constitutional, this law was found unconstitutional on the grounds that it had a clear religious purpose. Edwards v. Aguillard ( 1987 ) concerned a Louisiana “balanced treatment act,” a law that required creationism be taught alongside evolution to maintain neutrality. The court, in a 7-2 decision found the law unconstitutional according to all three prongs of the Lemon test. The courts have ruled similarly in more recent court cases such as Selman v. Cobb County School District ( 2006 ), which ruled that “warning labels” on evolution texts violated the Establishment Clause as well as Freiler v. Tangipahoa Parish Board of Education ( 1997 ) where the majority ruled that a “disclaimer” teachers were required to read before teaching evolution was unconstitutional.

In summary, since the 1940s when the 14th amendment was applied to the 1st amendment, public schools have been limited in what counts as permissible in relation to religion and public schooling. Summing up the legal parameters nicely is a document issued by the federal government entitled, “Federal Guidelines for Religious Expression in Schools ( 1997 ).” These guidelines, developed by a wide ranging panel first commissioned during the Clinton administration and then reauthorized under George W. Bush, emphasize that restrictions on religious expression are limited to school personnel while in their official capacity. Students, in contrast, have free range to express their religious beliefs in public schools, “short of harassment.” So although the religious orthodox have claimed that God has been removed from the public schools, the legal record tells us that free exercise has only been limited in the case of school officials and not students. For example, under the Equal Access Act ( 1984 ), student-initiated religious groups are permitted at schools. However, teachers cannot create or lead these groups, though they are allowed to monitor them.

Free Exercise

It is worth mentioning briefly the role of the free exercise clause in public schools. The chief function of the free exercise clause is to provide protection to religious minorities where laws created by the majority might serve unintentionally to restrict their free exercise. The most famous free exercise case related to public schools is, Wisconsin v. Yoder ( 1972 ). In this case, members of the Amish community requested an exemption from state compulsory attendance laws. Wisconsin law required all students to attend school until the age of 16. The Amish requested an exemption from the last two years of schooling (what essentially would have amounted to the first two years of high school). Their rationale was that the exposure Amish children would have could undermine their very way of life; indeed they claimed it threatened their survival. Ultimately, the court sided with the Amish for two very different reasons. First, acknowledging the importance of an education for participation in public life, the court reasoned that because the Amish live a self-sufficient life and by all outward expressions are a successful social unit, the exemption was warranted. Second, they reasoned that laws should not serve to threaten the very way of life of a religious minority group and the state ought to be respectful, not hostile, to minority religious views.

The law, then, sets clear parameters for what constitutes an establishment of religion and when individual free exercise should take precedent over generally applicable laws. One can conclude from this discussion that, contrary to the claim made by the religiously orthodox, public schools are not hostile to religion but rather are welcoming of religion in the public school in so far as it serves an educational purpose. This next section treats curriculum. Where, if at all should religion reside in the curriculum? What are the strengths and limitations of its inclusion? And finally, how does its inclusion contribute to cultivating a democratic ideal?

Curriculum serves as a battleground in education. Perhaps more than other dimensions of schooling, it tells us what is worth knowing and understanding. Curriculum, however, does not exist in a vacuum. Curriculum can be a deeply political issue, especially when dealing with the topics of science, history, and religion (Erekson, 2012 ). There is also significant discussion on who should set the curriculum priorities (the local school district, the states, or the federal government) as well as how much freedom teachers should have to move away from the set curriculum (Webb, 2002 ). How the curriculum treats religion has often created controversy. This is an even more complex issue in a society that is becoming both more non-religious as well as more religiously diverse (Pew Religious Center, 2015 ). Herbert Kliebard, the preeminent American curriculum historian, identifies four primary groups who have vied for supremacy in schools. These groups sought to define the U.S. educational curriculum in the late 19th and early 20th centuries . They were humanists, social meliorists, those focused on child development, and social efficiency educators (Kliebard, 2004 ; Labadee, 1987 ). Depending on which view enjoyed currency at a particular time in history, could determine whether religion, in some form, found its way into the formal narrative of schooling. Whereas the humanists were primarily concerned with fostering in students intellectual skills through the traditional disciplines, social meliorists thought curriculum should have a focus on activism—social improvement. Developmentalists thought that it was important to design curriculum around the development of the individual learner and social efficiency advocates thought curriculum should be limited to preparation for the workforce. As one examines different movements to include religion within the curriculum it is valuable to note which theoretical model is invoked. For these curricular approaches provide a lens into the view of religion with respect to larger society.

Religious Ways of Knowing

Discussions about the place of religion in the public schools are generally limited to robust discussions of the relevance and place of creationism in science classes (Berkman & Plutzer, 2010 ). Limiting discussions to creationism and science misses far more consequential arguments for an important and relevant role for religion in the public schools. Warren Nord has made perhaps the most convincing and comprehensive arguments for the centrality of religious ways of knowing to all disciplines (Nord, 2010 ). Nord argues that we fail to adequately teach common disciplines such as history and economics if we do not also provide religious ways of examining these disciplines (Nord & Haynes, 1998 ). For Nord it is not so much that religious perspectives have a stronger purchase on the truth of things, but rather the religious lens or a religious lens asks different sorts of questions than non-religious lenses and thus enlarges the conversations about various historical perspectives, economic theories, etc. For example, religion can serve as a type of critique of our current market-driven society or it can enlarge conversations related to scientific development, environmental sustainability, etc. (Nord, 1995 ). Nord, however, is not alone in his calls for including religion (religious perspectives) in the public school curriculum. Stephen Prothero and others have made a strong call for religious literacy (Prothero, 2007 ). Particularly since the terrorist attacks of 2001 in the United States, there has been a collective realization that, generally speaking, Americans are largely ignorant when it comes to understanding much about religion (Moore, 2007 ). Politicians and media outlets have often exploited this ignorance to create fear about Muslims, refugees, and the religious other. The contention goes, the more illiterate we are, the more religious intolerance predominates. This illiteracy is not limited to Islam, but can be said to be a general religious illiteracy (Wood, 2011 ). Nel Noddings has also made a forceful case for providing students with opportunities to explore existential questions in the public school classroom (Noddings, 2008 ). She argues that students already come to school bogged down with these types of questions, so schools have an obligation to help students make sense of them (Noddings, 1993 ). The Bible Literacy Project, an ambitious project endorsed by a wide range of academics and theologians provides a well-sourced textbook that can be used in schools (Bible Literacy Project, 2015 ). Though, their intentions may be less educational and more religious, many states have passed legislation permitting the teaching of the Bible in public schools (Goodman, 2006 ). The Bible used for literary or historical reasons seems justifiable (and fully constitutional). Furthermore, a “policy of inclusion” toward religion is vital for the “demands of a liberal, pluralist state” (Rosenblith, 2010 ).

Multiculturalism

A recent text by philosopher Liz Jackson makes the case that Muslims, in particular, are done a disservice when schools do not attend substantively to the study of Islam in schools. Her argument is based on three essential claims. First, in the absence of a substantive treatment in schools, citizens are left with popular culture depictions of Muslims (Jackson, 2010 ). These characterizations typically misrepresent Muslims. Second, the ways in which Muslims are depicted in social studies textbooks also take a narrow view. That is Muslims and Islam are largely depicted beginning in 2001 through the lens of terrorism (Jackson, 2011 ). Finally, Jackson argues that preservice teacher preparation programs do not do sufficient work in preparing future social studies teachers to be knowledgeable about Muslims and Islam, and therefore they are ill-equipped to disrupt the narratives perpetuated in textbooks or through popular culture (Jackson, 2011 ). It was not until the 2007 edition of the Banks and Banks Handbook on Multicultural Education that religion was even included as a form of identity (Banks & McGee Banks, 2007 ). Perhaps, U.S. schools should set up a system to certify teachers in the area of religious studies as they will “need to have the knowledge, skills, and dispositions” that would be expected in other disciplines (Rosenblith & Bailey, 2008 ). Other nations with liberal and pluralistic traditions such as Great Britain have been able to integrate religion into the curriculum while still embracing diversity and civic values (Rosenblith & Bailey, 2008 ).

Curricular Opportunities

There are many ways in which religion can be addressed in public school curricula that are both constitutionally permissible and educationally justifiable. Schools could provide world religion survey courses so that students have at least a superficial understanding of the range of religions in the world. Schools could offer controversial issues classes where religion could serve as both a topic and a perspective. Schools can study religious perspectives on a variety of current issues. Discussing religion does not need to lead to conflict or violence but can rather create an environment for “healthy, robust dialogue” (Rosenblith, 2008a ). In an increasingly diverse society, the ability to understand the perspectives of those from other faiths is vital for social cohesion and peace. Ignoring differences does not make intolerance dissipate but often allows stereotypes and antagonism to flourish. A pluralism that merely engages in “eschewing matters of truth, is wholly inadequate. It is inadequate because it fosters ignorance” (Rosenblith, 2008a ).

Central to carving out a curriculum that is both constitutionally permissible and educationally justifiable is framing it within a theory that honors the pluralistic and democratic commitments of public schools. Religious curriculum should contribute “to the public good” by helping students “develop knowledge and dispositions to resist religious intolerance and bigotry” and to understand and respect the “religious other” (Rosenblith, 2008b ).

Democracy, Autonomy, Pluralism

A central question when considering the role of religion in public education is grounded in questions about the role of the school, the rights of individuals, and the rights of groups. Perhaps more than many other forms of identity, religion casts the inherent tensions in bold terms. To paraphrase John Rawls’s central question in Political Liberalism , how does a society deeply divided on doctrinal grounds learn to get along (Rawls, 2005 )? To complicate matters further, even if we were to determine a mutually agreeable way forward for groups who are deeply divided by religious and political beliefs, what role would even more diverse individuals within those groups have in articulating their vision for a good life? These questions figure centrally in an understanding of religion and public schools.

Political theorists take a variety of perspectives on these matters. For some, the purpose of the public school is to privilege the pluralism of the nation and thus must be accommodating to such a degree that all particular groups feel included and valued (Kymlicka, 2001 , 2015 ). For others, the chief purpose of public schools is fundamentally civic and to that end, while schools should try to accommodate differences, they must not do so to such a degree that it jeopardizes a sense of civic identity and the values of a liberal democracy (Macedo, 1995 , 2000 ). While there are still others who fall somewhere in the middle, arguing that schools ought to promote a shared civic identity, but not at the expense of citizens finding the public school inhospitable to their particular religious views. In these instances, schools ought to accommodate religious believers by using levers such as opt-outs for curricular materials they find religiously objectionable if these levers prevent the groups from exiting the public schools (Gutmann, 1995 ). Others stress the importance of individual autonomy for students as the most important goal when looking at the often conflicting values of multiculturalism and civic liberalism (Reich, 2002 ).

Others are concerned about minority voices within particular religious groups (Okin, 1998 ). As Susan Okin points out, out of a desire to accommodate the free exercise of religious minority groups, there can be a denial of the individual rights that are the cornerstone of a liberal society. She asks what societies should do with religious groups that promote forced marriages, remove students from formal education, or prevent any outside socialization (Okin, 2002 ). Even though defenders of religious minorities may say that individuals have exit rights, Okin is concerned if this is truly an option for most people, especially young women who are the most oppressed in these systems. As she states, “even if it were feasible or even possible in a practical sense, exit may not be an option at all desirable, or even thinkable, to those most in need of it” (Okin, 2002 ). She does not believe the state should make special exemptions for religious groups if it endangers individual liberty. To fail to enforce these individual rights is “to let toleration for diversity run amok” (Okin, 2002 ). The prototypical example of this tension can be found in the famous case, Wisconsin v Yoder ( 1972 ). The majority decision sided with the Amish who only wanted their children to study in public schools until the age of 14 out of religious concerns ( Wisconsin v. Yoder , 1972 ). While the case is a moot issue today in an age where the option to homeschool is relatively simple (Gaither, 2008 ), it still generates significant discussion in relation to discussions of individual rights. Certainly the parents have rights that are distinguishable from the state, but many will argue that children have rights distinct from their parents (Worthington & Fineman, 2009 ). While it might be the parents’ interest in securing protection from exposing their kids to ways of life contrary to their own, the question becomes whether children have rights as individual agents and do the parents’ decisions overly determine their children’s futures. This leads to some of the deeper philosophical questions in public education. What role does the state and family play in making sure children have an environment that is both secure and open to individual autonomy?

Exit Rights, Civic Education, and Religious Orthodoxy

This concern spills over into discussion of exit rights. Do children have a right to an education that might lead them to exit their religious group (Lester, 2004 )? Might a robust civic education provide new and different lenses through which children see the world that might make their home belief system less compelling? Should public schools in a pluralist state provide individuals with the kind of education that might lead to their exit from their home faith? Should public schools refrain from a robust civic education in order to protect and allow religious ideologies to flourish? To whom does the public school primarily answer? When is a religious ideology so extreme that to accommodate it seriously undermines the ideals of the American society? These are not easy questions to address and while they are difficult questions to wrestle with in terms of identity broadly understood, they are that much more vexing when it comes to religion. The reason being that religion, unlike culture, rests on epistemological foundations that for those who identify as religiously orthodox, are exclusive, inalienable, and unchanging. Educators are mistaken in simply “conflating” religion as another aspect of culture as it “strips religion” of its “essential qualities” (Rosenblith, 2008a ). This makes the project of civic education, for some, in many ways incommensurable with fostering religious identity. If the idea of a public school is, in part, to bring together people with very different visions of the good life and figure out ways forward, those who believe their very salvation hangs in the balance of one particular vision are understandably not going to be flexible in terms of tolerance and respect for a wide range of beliefs or for the very idea that public schools espouse—good citizenship hangs on an individual’s ability to respect and tolerate those with whom we disagree. In short, the problem becomes a non-starter for the most orthodox, making the civic project that much more difficult. This is of special difficulty for teachers as they seek to “navigate” the tensions between “the religiously orthodox and pluralist public schooling” (Bindewald & Rosenblith, 2015 ).

Religion, Schooling, and Indoctrination

One of the conflicts with integrating religion in schools is whether it is perceived as exposure or indoctrination. A suspicion of indoctrination can create angst in both the non-religious and the deeply orthodox. An extreme example of this fear occurred this past year when a father threatened a teacher because she was teaching about Islam in the class. It led to the closure of a whole school district (Robertson, 2015 ). If we are to have classrooms, which are filled with vibrant students who are open to critical thought, we have to move beyond the anxiety that any discussion on religion is the same as indoctrination. This is why the “trump card” of parental rights in preventing students from being exposed to materials that may conflict with private teachings is problematic (Rosenblith & Bindewald, 2014 ).

If educators approach religion appropriately in the classroom, it should not lead to a concern of indoctrination. Rather, it can be a tool that helps students become more religiously literate and “resist religious intolerance and bigotry and instead learn about the religious other” (Rosenblith, 2008b ). Are we limiting the possibilities for educational vibrancy and civic and multicultural understanding due to an exaggerated fear of religion in the classroom? What if the reasons for teaching religion in the classroom were not an attempt of “relativizing truth” or wanting to “coax students away from the religion of their parents” but rather helping to garner “fair depictions of the other” (Rosenblith & Bindewald, 2014 ). Perhaps, this is the approach to religion in the classroom that the majority of society could agree to.

Within the literature, far less attention has been given to treating the problem than has been given to identifying the problem. Diana Hess and Rob Kunzman have addressed ways forward. Suzanne Rosenblith and Benjamin Bindewald have as well. Hess argues for encouraging a discussion of controversial issues in the classroom as controversy is not an “unfortunate byproduct” of democracy but rather one of its “core and vital elements” (Hess, 2004 ). Hess argues that these controversial conversations should be the “students’ forum” where the teachers’ views do not directly impact the discussion but are integral for the discussions chosen (Hess, 2002 ).

Kunzman argues for “loosening liberal boundaries” in allowing for alternative and more orthodox perspectives in classroom discussion. After all, there is no consensus on what is “reasonable” when it comes to the discussion of religion and controversial issues. A truly civic education can work against the “disenfranchisement” of religious perspectives in the public sphere (Kunzman, 2005 ). He also argues that there will inherently be conflict in a religiously diverse society. Instead of ignoring this, educators should teach students how to navigate these conflicts and help create a greater understanding of religious diversity (Kunzman, 2006 ). He suggests using activities such as role play and field experience to create a more “empathetic understanding” of the other and move students “beyond knowledge to appreciation” (Kunzman, 2006 ). He also suggests letting students be the “source of insider perspective” when it comes to their own religious traditions (Kunzman, 2006 ).

Rosenblith and Bindewald look at this issue from a slightly different angle. They explore how teachers should handle exclusive comments made by the religiously orthodox that may be offensive to other students. They use the example of a student using the Bible to justify statements against homosexuality. They suggest for teachers to not simply ignore or downplay these types of comments, but rather make the distinction regarding arguments based on reason versus those based purely on religious belief. While giving the students the freedom to discuss the issues, teachers can and often should deal with these issues “directly” and with a level of “certitude” (Bindewald & Rosenblith, 2015 ). In another text, they argue for “mutuality,” which is a type of middle ground between “mere tolerance” and “robust respect” (Rosenblith & Bindewald, 2014 ). They see this mutuality as a willingness to engage in a relationship with the religious other (Rosenblith & Bindewald, 2014 ). It means that differences are not necessary “resolved” or “trivialized” but rather students engage in “a process of mutual reciprocity and understanding” (Rosenblith & Bindewald, 2014 ). The ultimate hope is that this will lead to “to a greater realization of justice and tolerance in the larger public sphere” (Rosenblith & Bindewald, 2014 ).

In our increasingly diverse, global, and interdependent society, confronting, understanding, and respecting the religious other is of paramount importance. In the United States, this places a particular obligation on the public schools to rethink its role in helping young citizens understand the history, complexity, and contributions of religion historically as well as in contemporary contexts. The relationship between religion and public education is one that has been inexorably tied to politics—religious and secular politics. This has led to a relatively ineffective exploration of religion in public schools. Recognizing the direct connection between religious illiteracy and religious intolerance, one can hope that a reconceptualization of the role of religion and public schools, one that takes religion, education, democracy, and pluralism seriously is near. In treating religion, education, democracy and pluralism seriously, the public schools can come closer to fulfilling their obligations to attend at once to individual and collective goals.

- Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203 (1963).

- Banks, J. A. , & Banks, C. A. McG. (2007). Multicultural education: Issues and perspectives (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Baritz, L. (1964). City on a hill: A history of ideas and myths in America . New York: Wiley.

- Berkman, M. B. , & Plutzer, E. (2010). Evolution, creationism, and the battle to control America’s classrooms . New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bindewald, B. J. , & Rosenblith, S. (2015). Addressing orthodox challenges in the pluralist classroom. Educational Studies , 51 (6), 505–506.

- Constitution Society . (1647). The Old Deluder Act . Retrieved from http://www.constitution.org/

- Deckman, M. M. (2004). School board battles: The Christian right in local politics . Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578 (1987).

- Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 (1962).

- Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97 (1968).

- Erekson, K. A. (Ed.). (2012). Politics and the history curriculum: The struggle over standards in Texas and the nation . New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Everson v. Board of Education, 30 U.S. (1947).

- Hinsdale, B. A. (1898). Horace Mann and the common school revival in the United States . New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Fiske, J. (1889). The beginnings of New England: Or, the Puritan theocracy in its relations to civil and religious liberty . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Fox, J. (2011). Separation of religion and state and secularism in theory and in practice. Religion, State and Society , 39 (4), 384.

- Fraser, J. W. (2001). The school in the United Staes: A documentary history (1st ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill

- Freiler v. Tangipahoa Parish Board of Education, 975 F.Supp 819 (1997).

- Gaither, M. (2008). Homeschool: An American history (1st ed). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Goodman, B. (2006, March 29). Teaching the bible in Georgia’s public schools. New York Times .

- Greene, S. (2012). The bible, the school, and the Constitution: The clash that shaped modern church-state doctrine (1st ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gutman, A. (1987). Democratic education . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Gutman, A. (1995). Civic education and social diversity. Ethics , 105 (3), 557–579.

- Hayes, W. (2006). Horace Mann’s vision of the public schools: Is it still relevant? Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

- Hedges, C. (2008). I don’t believe in atheists (1st ed.). New York: Free Press.

- Hess, D. E. (2002). Discussing controversial public issues in secondary social studies classrooms: Learning from skilled teachers. Theory & Research in Social Education , 30 (1), 29–32.

- Hess, D. E. (2004). Controversies about controversial issues in democratic education. PS: Political Science and Politics , 37 (2), 257.

- Hodgson, C. V. (2004). Coercion in the classroom: The inherent tension between the free exercise and establishment clauses in the context of evolution. Next, A Journal of Opinion 9 , 171.

- Jackson, L. (2010). Images of Islam in U.S. media and their educational implications. Educational Studies , 46 (1), 17.

- Jackson, L. (2011). Islam and Muslims in U.S. public schools since September 11, 2001. Religious Education , 196 (2), 173.

- Kaveny, M. C. (2013). The remnants of theocracy: The Puritans, the Jeremiad and the contemporary culture wars. Law, Culture and the Humanities , 9 (1), 59–70.

- Kliebard, H. M. (2004). The struggle for the American curriculum, 1893–1958 (3d ed.). New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Kunzman, R. (2005). Religion, politics and civil education. Journal of Philosophy of Education , 39 (1), 162–164.

- Kunzman, R. (2006). Imaginative engagement with religious diversity in public school classrooms. Religious Education , 101 (4), 518.

- Kymlicka, W. (2001). Politics in the vernacular: Nationalism, multiculturalism and citizenship . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kymlicka, W. (2015). Multiculturalism and minority rights: West and east . Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issuses in Europe: JEMIE , 14 (4), 1–26.

- Labadee, D. (1987). Politics, markets, and the compromised curriculum. Harvard Educational Review , 57 (4), 483–494.

- Larson, E. J. (1997). Summer for the gods: The Scopes trial and America’s continuing debate over science and religion . New York: Basic Books.

- Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971).

- Lester, E. (2004). Gratitude and parents’ right over their children’s religious upbringing. Journal of Beliefs & Values , 25 (3), 295–306.

- Long, E. (2012). Church-state debate: Religion, education and the establishment clause in post war America . Bloomsbury, U.K.: GB.

- Macedo, St. (1995). Liberal civic education and its limits. Canadian Journal of Education , 20 (3), 304–314.

- Macedo, S. (2000). Diversity and distrust: Civic education in a multicultural democracy . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mann, H. (1965). Horace Mann on the crisis in education . Yellow Springs, OH: Antioch Press.

- Mann, H. , & Massachusetts Board of Education . (1957). The republic and the school: Horace Mann on the education of free men . New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Massaro, T. M. (2005). Religious freedom and “accommodationist neutrality”: A non-neutral critique. Oregon Law Review , 84 (4), 935

- McCollum v. Board of Education, 333 U.S. 203 (1948).

- McGuffey, W. H. (1836). McGuffey reader: Eclectic second reader . Cincinatti, OH: Truman and Smith.

- Moore, D. L. (2007). Overcoming religious illiteracy: A cultural studies approach to the study of religion in secondary education (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Moore, R. L. (2000). Bible reading and nonsectarian schooling: The failure of religious instruction in nineteenth-century public education. The Journal of American History , 86 (4), 1581–1599.

- Neuhaus, R. J. (2007). Strict church-state separationists of a fanatical bent routinely claim that exempting religion from government regulation constitutes a violation of the no-establishment provision of the religion clause of the first amendment. First Things: A Monthly Journal of Religion and Public Life , 176 , 80.

- New England Primer . (1805). Retrieved from http://public.gettysburg.edu/~tshannon/his341/nep1805contents.html

- Noddings, N. (1993). Educating for intelligent belief or unbelief . New York: Teachers College Press, Columbia University.

- Noddings, N. (2008). Chapter 13: Spirituality and religion in public schooling. Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education , 107 (1), 185–195.

- Nord, W. A. (1995). Religion & American education: Rethinking a national dilemma . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Nord, W. A. (2010). Does God make a difference?: Taking religion seriously in our schools and universities . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Nord, W. A. , & Haynes, C. C. (1998). Taking religion seriously across the curriculum . Nashville: ASCD.

- Okin, S. M. (1998). Feminism and multiculturalism: Some tensions. Ethics , 108 (4), 661–684.

- Okin, S. (2002). Mistresses of their own destiny: Group rights, gender, and realistic rights of exit. Ethics , 112 (2), 215.

- Prothero, S. R. (2007). Religious literacy: What every Americna needs to know—and doesn’t (1st ed.). San Francisco: Harper.

- Rawls, J. (2005). Political liberalism . New York: Columbia University Press.

- Reich, R. (2002). Bridging liberalilsm and multiculturalism in American education . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Robertson, G. (2015, December 18). Virginia county closes schools as Islam assignment prompts backlash . Reuters .

- Rogers, T. K. (2010). Parental rights: Curriculum opt-outs in public schools (Doctoral dissertation, University of North Texas).

- Rosenblith, S. (2008a). Beyond coexistence: Toward a more reflective religious pluralism. Theory and Research in Education , 6 (1), 114.

- Rosenblith, S. (2008b). Religious education in a liberal, pluralist, democratic state. Religious Education , 103 (5), 510.

- Rosenblith, S. (2010). Educating for autonomy and respect or educating for Christianity? The case of the Georgia Bible bills. Journal of Thought , 45 (1–2), 26.

- Rosenblith, S. , & Bailey, B. (2008). Cultivating a religiously literate society: Challenges and possibilities for America’s public schools. Religious Education , 103 (2), 159.

- Rosenblith, S. , & Bindewald, B. (2014). Between mere tolerance and robust respect: Mutuality as a basis for civic education in pluralist democracies. Educational Theory , 64 (6), 590, 598, 602.

- Rudolph, F. (1965). Essays on education in the early republic . Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

- Sears, J. T. , & Carper, J. C. (1998). Curiculum, religion, and public education: Conversations for an enlarging public square . New York: Teachers College Press, Columbia University.

- Selman v. Cobb County School District, 449 F.3d 1320. 11th Cir. (2006).

- Shreve, G. (2010). Religion, science and the secular state: Creationism in American public schools. The American Journal of Comparative Law , 58 , 51–58.

- Temperman, J. (2010). State-religion relationships and human rights law: Towards a right to religiously neutral governments (1st ed., Vol. 8). Boston: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Wallace v. Jaffree, 472 U.S. 38 (1985).

- Webb, P. T. (2002). Teacher power: The exercise of professional autonomy in an era of strict accountability. Teacher Development , 6 (1), 47–62.

- Westerhoff, J. H. (1978). McGuffey and his readers: Piety, morality, and education in nineteenth century America . Nashville: Abingdon.

- Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972).

- Wood, S. K. (2011, Winter). Religious illiteracy . Marquette Magazine .

- Worthington, K. , & Fineman, M. (2009). What is right for children? The competing paradigms of religion and human rights . New York: Routledge.

- Zorach v. Clauson, 343 U.S. 306 (1952).

Related Articles

- Islamophobia and Education

- The Controversy of Muslim Women in Liberal Democracies

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 08 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [195.158.225.244]

- 195.158.225.244

Character limit 500 /500

Advertisement

The impact of institutional context on research in religious education: results from an international comparative study

- Open access

- Published: 30 August 2023

- Volume 71 , pages 155–166, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ulrich Riegel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9423-9092 1 &

- Martin Rothgangel 2

647 Accesses

Explore all metrics

On the one hand, research on religious education is done according to a transnational scientific paradigm, on the other hand, it is performed within particular institutional contexts which vary from nation to nation.This raises the question of how institutional context affect research on religious education. The paper addresses this question on the basis of an international study. N = 49 colleagues across Europe as well as Israel, South Africa, South Korea, and Turkey filled in an online-questionnaire regarding their own research. Despite the international character of the sample, research on religious education seems to be practiced quite coherently in regard of the objects of inquiry, the applied methods, and the disciplines the colleagues refer to. The few significant differences indicate that theology and educational studies are slightly more important in contexts of denominational religious education as well as analysing both pupils and processes of teaching and learning. In the context of non-denominational RE, instead, religious studies is slightly more important. These results will be discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Religious Education in European Organisations, Professional Associations and Research Groups

Comparative studies in religious education: perspectives formed around a suggested methodology.

Conclusion: Human Rights and Religion in Educational Contexts. Foundations and Conceptional Perspectives

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The goal and character of religious education are currently the subject of controversial debate. In Europe, for example, some are calling for religious education to be replaced by worldview education (Halafoff et al., 2016 ; van der Kooij et al., 2017 ), while others argue for a more spiritual layout of this subject (Roebben, 2021 ). In Latin America and Africa, in turn, the trending topic seems to be the decolonialization of religious education with the goal of overcoming a dominant Christian bias (Blank de Oliveira & Riske-Koch, 2021 ; Drange, 2015 ; Matemba, 2021 ; Mokotso, 2020 ). And there are still the pending questions of what teachers of religious education have to know to competently teach that subject (Whitworth, 2020 ), which type of knowledge this could be (Moore, 2007 ), and which competencies are required to offer an effective religious education (Helbling & Riegel, 2021 ).

These academic debates take place within diverse institutional contexts regarding the practice of religious education at schools. It reveals a multifaceted picture ranging from various denominational forms to non-denominational ones (Jackson, 2007 ; Kuyk et al., 2007 ; Rosenblith, 2017 ; Rothgangel, et al., 2014a , 2014b , 2020a , 2020b , 2020c ). Of course, this basic distinction between denominational and non-denominational religious education does not capture the manifold forms in which religion is taught at schools in the various national contexts. Going into detail, denominational religious education varies between confessional layouts like in Italy (Giorda, 2015 ), Chile (Guzman et al., 2021 ), or South Korea (Kim, 2018 ) to ones realizing a “learning from religion” approach like in Germany (Kropač, 2021 ). Non-denominational religious education, instead, follows a pure religious studies approach to some extent (Alberts, 2007 ; Kenngott, 2017 ), partly happening within a formative frame of reference which allows for identification with religions and worldviews (Bietenhard et al., 2015 ; Bleisch, 2017 ). Furthermore, there are cross-sectional types of religious education like in Finland, which is in legal perspective denominational and in pedagogical perspective multi-religious (Lipiäinen et al., 2020 ). Finally, in some cases, the character of religious education varies even within one national context. In Germany, for example, denominational education is the default type of religious education, but in the federal states of Bremen and Brandenburg, religion is taught in a non-denominational manner (Kropač, 2021 ).

Despite these pluriform institutional contexts of teaching religion at schools, within the national academic discourses on religious education there seem to exist quite coherent frames of reference. In Italy, for example, the discussion on how to do justice to religious diversity in the classroom takes place within the framework of denominational education. Non-denominational forms are mentioned, but always as alternatives to the default denominational model (Giorda, 2015 ). The same is true for Chile (Guzman et al., 2021 ), South Korea (Kim, 2018 ), and Germany (Kropač, 2021 ). In contrast, in England and Wales, the discussion of whether replacing religious education by worldview education is happening within a non-denominational frame of reference (CoRE. Commission on Religious Education, 2018 ). It seems to be common sense in that particular discourse that religion must be taught at schools beyond specific denominational accounts. The same also applies to the situation in Finland (Ubani et al., 2019 ), Belgium, and the Netherlands (Miedema, 2014 ), as well as the recent discourse in Switzerland (Bleisch, 2017 ).

These academic discourses on religious education are embedded in a transnational understanding of science. Scientific discourse works according to both rational standards and research agendas that do not vary much across national contexts (e.g., Godfrey-Smith, 2003 ; Gutting, 2005 ). Scientific disciplines are characterized by a particular epistemological paradigm, a distinct set of objects to be analyzed, well-defined methods, and a specific set of theories that these analyses refer to. National and regional particularities may be relevant on the level of single projects and discussions, but hardly play a role on the general level. In the postcolonial discourse in religious education, for example, the country’s particular national history is part of the discussion on the national level. Nonetheless, all these national discussions share the same goal of overcoming colonial structures and apply the same epistemology, refer to the same categories, and use similar methods to realize this goal. And if the field of didactic Footnote 1 research is regarded, a recent Delphi study in Germany found that the various didactic disciplines share a common understanding of the objects they analyze, the methods they use in this analysis, and the academic disciplines they refer to (Riegel & Rothgangel, 2023 ).

If one relates these different observations to each other, a complex picture emerges. On the one hand, on an international level, there is a controversial debate on both the goal and character of religious education in schools, and there are different institutional contexts in which this subject is taught at school. On the other hand, the academic discussion about religious education takes place within the framework of coherent frames of reference and the self-identification of this academic discourse as a science follows transnational standards. Given this complex picture, the question of how the institutional context on a national level characterizes research in religious education across various countries is raised. From the perspective of systems theory (Runkel & Burkart, 2005 ), one could argue that religious education on the one hand and the academic discourse on religious education on the other hand are two separate systems, each following a particular ratio. According to Luhmann, the basic goal of the educational system is to transmit knowledge and competencies to qualify its users for their future tasks (Luhmann, 2002 ). The scientific system is instead oriented towards corroborating the truth of its hypotheses (Luhmann, 1992 ). Since both goals are basically incompatible, one could assume that the dominant institutional context of religious education on a national level does not coin the academic discourse on religious education.

From an ecosystemic perspective, however, institutional contexts frame the actions of the persons within that context. Bronfenbrenner, for example, distinguishes between mesosystems and microsystems (Lüscher & Bronfenbrenner, 1981 ). While the microsystem represents the individuals’ zones of interactions, the mesosystems reflect the institutional or organizational context of the individuals’ actions. The idea of Bronfenbrenner’s approach is that every microsystem depends on the options and restrictions of the mesosystems in which it is embedded. In our case, religious education researchers are members of faculties and departments at universities and teacher colleges. These faculties and departments more or less mirror the basic structure of the dominant model of religious education in the relevant national context: In countries with a dominant denominational model of religious education, the faculties and departments are, in most cases, of theological character, while in nations with a non-denominational model of religious education, the nature of relevant faculties and departments is usually that of religious studies. From an ecosystemic perspective, such particular institutional characteristics should frame the researchers’ activity and therefore the relevant academic discourse on a national level.

On theoretical grounds, one cannot estimate how much of the character of the academic discourse on religious education on an international level can be explained by systems theory or ecosystemic theory respectively. Therefore, this paper addresses the following research questions:

What are the basic features of research in religious education on an international level?

Does the institutional context of religious education on a national level cause characteristic differences in these features?

2 Sample, method, measures and analysis

To answer these questions, this paper uses data from an international survey. The sample of the international study was collected via academic networks like ISREV and NCRE as well as via contacts within the project "Religious Education in Schools in Europe". Through these channels, the participants were informed about the scope of the study and invited to fill out a questionnaire with both open-ended and closed-ended questions. Finally, 49 religious education teachers across Europe as well as Israel, South Africa, South Korea, and Turkey responded to this invitation. On a national level, the answers are distributed as follows: Norway: 5 answers; Turkey and Greece: 4 answers each; Germany, England and Wales, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Netherlands: 3 answers each; Poland: 2 answers; Czechia, Finland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, South Africa, and South Korea: 1 answer each. 12 participants did not disclose their national background. In terms of religious belonging, 15 participants are protestant, 12 are roman-catholic, 6 Muslim, 1 Jewish, and 6 express another religious tradition. Nine participants did not respond to this question. All respondents work at an institution offering training for future religion teachers and hold a PhD.

2.2 Measures

As indicator of academic discourse, the respondents’ research practice was chosen. From this perspective, the academic discourse is what scholars fundamentally do. This practice was conceptualized according to the three dimensions of (i) objects of inquiry, (ii) methods applied in research, and (iii) the disciplines the respondents refer to in their research. The objects of inquiry reveal the topics that are addressed in research, the methods in use indicate how these topics are addressed, and the reference disciplines offer information on which basic theoretical ground this research takes place. Since these dimensions represent basic patterns of research within the philosophy of science (e.g. Godfrey-Smith, 2003 ; Gutting, 2005 ), this conceptualization of research seems to be appropriate.

In the questionnaire, each dimension was operationalized by a closed-ended question offering a possible operationalization of each dimension, and the participants were asked to estimate how relevant they consider each category of this operationalization in their own research. Respondents were able to answer on a six-point Likert scale (1 = “not important at all”; 6 = “very important”). In order to be able to trace residual options, the option "I cannot assess" was additionally offered.

To assess the relevance of institutional context, the variable of nationality was recoded. The criteria were the dominant frame of reference according to which religious education is discussed in the relevant country. The countries with a denominational frame of reference form one category (Czechia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, South Korea, Turkey) and those with a non-denominational frame form another (England and Wales, Finland, Norway, South Africa, the Netherlands). With this recoded variable, it is possible to test the previously mentioned assumption of the effect of institutional context on academic discourse.

2.3 Analysis

Data analysis follows a two-step procedure. First, to reconstruct the basic features within the field of research in religious education, descriptive statistics of the single categories on the three basic dimensions of methodologies, objects of inquiry, and reference dimensions will be calculated. Because of the ordinal nature of the quantitative data, data analysis refers to median ( Mdn ) and interquartile range ( IQR ) and presents its results as a boxplot graph.

Second, the effect of the institutional context is tested by a Whitney–Mann U -Test. The effect size is calculated by Pearson’s r according to Cohen’s benchmarks (Cohen, 1988). All statistical calculations are done with the software package SPSS 27.

The results will be described according to the two research questions. First, the basic features of research in religious education will be reconstructed, after which the impact of institutional context on this research will be tested.

3.1 The basic features of research in religious education

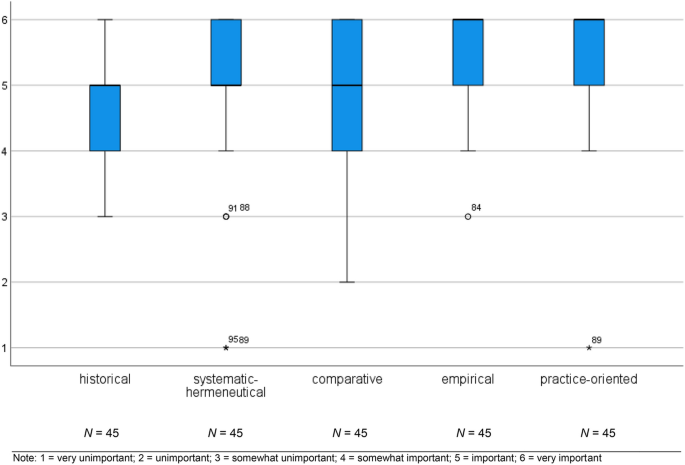

Regarding methodologies, six categories were offered to the participants: historical, systematic-hermeneutical, comparative, empirical, and practice-oriented research. There are two methodical approaches to the field of religious education that show a median of Mdn = 6, namely the empirical and the practice-oriented ones (Fig. 1 ). This indicates that both methodologies are very important in the respondents’ research. The other three methodical approaches have a median of Mdn = 5, indicating that these methodologies are important, but less so. The range of the answers is rather small, with only the comparative approach having an IQR = 2. Further on, there are only three extreme values. All in all, this indicates a rather coherent evaluation of the five methodical approaches within the international sample, with all five offered categories regarded as no less than important as features of methodology in research in religious education.

Boxplots of methods in own research

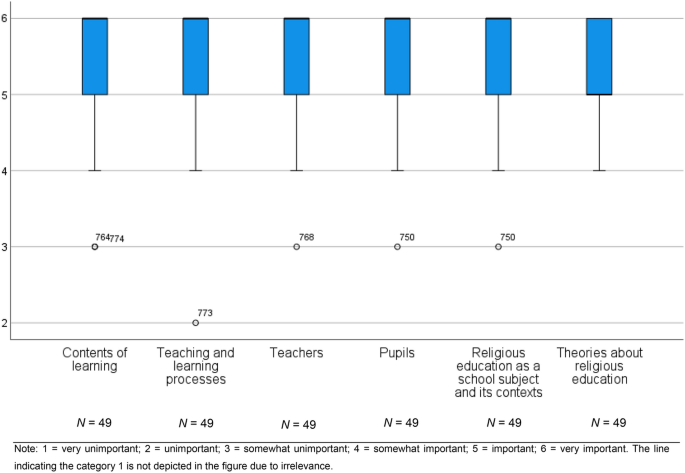

Regarding the objects of inquiry, the respondents were asked, “how important [they] consider the following characteristic topics in [their] own research activities in religious didactics”. The offered categories were contents of learning, the teaching and learning process, teachers, pupils, religious education as a school subject and its contexts, and theories about religious education. All but one topic were regarded as very important with Mdn = 6; only theories about religious education were considered to be important ( Mdn = 5) (Fig. 2 ). Again, the respondents from various countries were quite coherent in their evaluation, with IQR = 1 on all topics and no extreme values.

Boxplots of objects of inquiry in own research

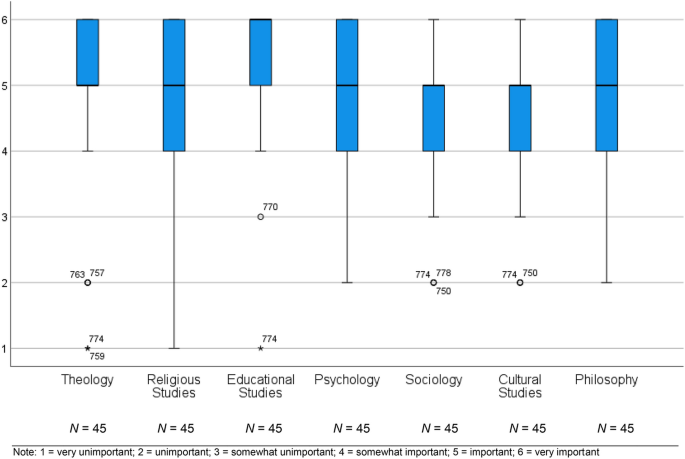

The relevance of the various reference disciplines in religious education research was assessed by the following question: “How important do you consider the following reference disciplines for your own research activities in religious didactics?” The options were theology, religious studies, educational studies, psychology, sociology, cultural studies, and philosophy. Educational studies were the only ones that were very important to most of the respondents ( Mdn = 6), while all other means of reference disciplines were evaluated as important ( Mdn = 5) (Fig. 3 ). This time, there was some variance in the answers, particularly regarding religious studies, psychology, and philosophy. All these disciplines show an IQR = 2, with the whiskers covering the entire spectrum of possible answers in the case of religious studies and the entire spectrum but one answer category in the cases of psychology and philosophy respectively. This is a remarkable finding given the quite coherent responses so far.

Boxplots of reference disciplines in own research

3.2 The impact of institutional context

Assessing the effect of the institutional context on the importance of methodologies, the Mann–Whitney-U-Test brings about one significant difference. The participants within the context of denominational religious education ( Mdn = 6) regard systematic-hermeneutical methodologies as more important than the scholars researching within a context of non-denominational religious education ( Mdn = 5), U (N den = 22; N non-den = 13) = 83.500; z = − 2.318; p = .02). The effect of this difference is medium-sized according to Cohen (1992) ( r = .39). The importance of the other methodologies is not affected significantly by the respondents’ institutional context.

If objects of inquiry are taken into account, two significant differences occur. In both cases, the participants within a denominational context regard the relevant object of inquiry as very important in one’s own research ( Mdn = 6), while the researchers within a non-denominational context regard them as important ( Mdn = 5). These topics are the process of teaching and learning ( U (N den = 24; N non-den = 13) = 73.000; z = − 3.083; p = .002) and the pupils ( U (N den = 24; N non-den = 13) = 82.500; z = − 2.603; p = .009) respectively. The effect of institutional context on the evaluation of processes of teaching and learning is strong ( r = .51), which in the evaluation of the importance of researching pupils is medium-sized ( r = .43).

Finally, institutional context explains the variance in three cases of reference theories to some extent. Theology is a more important reference discipline to respondents from a denominational context ( Mdn = 6) than to those from a non-denominational context ( Mdn = 4) ( U (N den = 24; N non-den = 12) = 75.500; z = − 2.471; p = .013), having a medium-sized effect ( r = .41). Religious studies, in turn, is more important to scholars within a non-denominational context ( Mdn = 6) than to those from a denominational context ( Mdn = 5) ( U (N den = 24; N non-den = 12) = 92.500; z = − 2.121; p = .034). Again, the effect size is medium ( r = .35). Finally, the respondents within a denominational context regard educational studies ( Mdn = 6) as more import than those within a non-denominational context ( Mdn = 5) ( U (N den = 24; N non-den = 13) = 96.500; z = − 2.007; p = .045). The effect of institutional context is medium ( r = .33).

4 Discussion

This article aims to map the field of research in religious education on an international level and to assess the effect of the institutional context on the features of this field. The mapping happened according to the three dimensions of methodologies, objects of inquiry, and reference disciplines. All in all, there are two noteworthy results.

Firstly, across the various countries of this sample, the respondents from religious education predominantly apply empirical and practice-oriented methods, refer theoretically most often to educational studies and theology or religious studies, respectively, and turn out to be generalists in terms of the topics they analyze. Beyond this common ground of research on religious education on international level, there are some categories of lesser importance. If methods are regarded, historical and comparative ones seem to be least important. In view of the recent call for an international knowledge transfer (Schweitzer & Schreiner, 2020 ), the relative importance of comparative methods in particular raises the question of how to promote this transfer. Then, within the reference disciplines, it is religious studies, psychology and philosophy that show a remarkable variance in their importance for the respondents’ research. Some of the participants regard these disciplines as very important, others as unimportant (psychology and philosophy) or even very unimportant (religious studies) for their academic projects. In sum, there is much coherence in the academic discourse on religious education on an international level with some remarkable differences.

Secondly, this paper analyzes the assumption that such differences are caused by the institutional context on a national level. It hypothesizes that the dominant idea of how to teach religion in schools frames the academic discourse on this education. According to the findings, this assumption is true to some extent, but not in the way it was expected. First, four of the five categories with a bigger variance in the answers were not affected by institutional context. Neither the importance of historical and comparative methods nor the importance of psychology and philosophy as disciplines referred to in one’s projects is explained by the fact that religious education in one’s country is taught predominantly according to a denominational or a non-denominational model respectively. Only the importance of religious studies as a reference discipline is explained by this context to some extent. This result points to a rather remote effect of institutional context on the academic discourse in religious education.

Nonetheless, there are six categories with significant differences caused by institutional context. Besides religious studies, which is more important to scholars within a non-denominational context, theology and educational studies are more important reference theories to researchers from a denominational context. The same is true for the use of systematic-hermeneutical methods and the analysis of processes of teaching and learning and pupils respectively. Since the effect of these differences is at least medium-sized, one cannot speak of differences of minor importance. Furthermore, the effect turns out to be significant, although the variance in the answers of five categories (systematic-hermeneutical methods, teaching and learning processes, pupils, theology, educational studies) is rather small. This indicates that institutional context on a national level indeed coins research on religious education. In more detail, it is not the national context itself, but the dominant model of religious education at schools in the country.

From an ecosystemic perspective, these findings are quite plausible (Lüscher & Bronfenbrenner, 1981 ). For example, the denominational context refers to theology as a basic academic discipline which is very skilled in systematic-hermeneutical methods itself (Ford, 2013 ; Jung, 2004 ). At the same time, the higher importance of religious studies in a non-denominational context can be explained by the constitutive role of this academic subject for the relevant type of religious education. The findings further support the often criticized distinction between denominational and non-denominational religious education. Of course, this distinction is rather bold and is not able to map the subtle differences within these basic accounts of how religion is taught at schools (Jackson, 2007 ). Nevertheless, it is able to reconstruct fundamental differences in the study of religious education. Particularly in fields that are not analyzed intensely yet, like the basic features of the academic discourse on international level, it is useful for tracing fundamental patterns and therefore offers a solid basis for more detailed analysis.