Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write a Thesis

I. What is a Thesis?

The thesis (pronounced thee -seez), also known as a thesis statement, is the sentence that introduces the main argument or point of view of a composition (formal essay, nonfiction piece, or narrative). It is the main claim that the author is making about that topic and serves to summarize and introduce that writing that will be discussed throughout the entire piece. For this reason, the thesis is typically found within the first introduction paragraph.

II. Examples of Theses

Here are a few examples of theses which may be found in the introductions of a variety of essays :

In “The Mending Wall,” Robert Frost uses imagery, metaphor, and dialogue to argue against the use of fences between neighbors.

In this example, the thesis introduces the main subject (Frost’s poem “The Mending Wall”), aspects of the subject which will be examined (imagery, metaphor, and dialogue) and the writer’s argument (fences should not be used).

While Facebook connects some, overall, the social networking site is negative in that it isolates users, causes jealousy, and becomes an addiction.

This thesis introduces an argumentative essay which argues against the use of Facebook due to three of its negative effects.

During the college application process, I discovered my willingness to work hard to achieve my dreams and just what those dreams were.

In this more personal example, the thesis statement introduces a narrative essay which will focus on personal development in realizing one’s goals and how to achieve them.

III. The Importance of Using a Thesis

Theses are absolutely necessary components in essays because they introduce what an essay will be about. Without a thesis, the essay lacks clear organization and direction. Theses allow writers to organize their ideas by clearly stating them, and they allow readers to be aware from the beginning of a composition’s subject, argument, and course. Thesis statements must precisely express an argument within the introductory paragraph of the piece in order to guide the reader from the very beginning.

IV. Examples of Theses in Literature

For examples of theses in literature, consider these thesis statements from essays about topics in literature:

In William Shakespeare’s “ Sonnet 46,” both physicality and emotion together form powerful romantic love.

This thesis statement clearly states the work and its author as well as the main argument: physicality and emotion create romantic love.

In The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne symbolically shows Hester Prynne’s developing identity through the use of the letter A: she moves from adulteress to able community member to angel.

In this example, the work and author are introduced as well as the main argument and supporting points: Prynne’s identity is shown through the letter A in three ways: adulteress, able community member, and angel.

John Keats’ poem “To Autumn” utilizes rhythm, rhyme, and imagery to examine autumn’s simultaneous birth and decay.

This thesis statement introduces the poem and its author along with an argument about the nature of autumn. This argument will be supported by an examination of rhythm, rhyme, and imagery.

V. Examples of Theses in Pop Culture

Sometimes, pop culture attempts to make arguments similar to those of research papers and essays. Here are a few examples of theses in pop culture:

America’s food industry is making a killing and it’s making us sick, but you have the power to turn the tables.

The documentary Food Inc. examines this thesis with evidence throughout the film including video evidence, interviews with experts, and scientific research.

Orca whales should not be kept in captivity, as it is psychologically traumatizing and has caused them to kill their own trainers.

Blackfish uses footage, interviews, and history to argue for the thesis that orca whales should not be held in captivity.

VI. Related Terms

Just as a thesis is introduced in the beginning of a composition, the hypothesis is considered a starting point as well. Whereas a thesis introduces the main point of an essay, the hypothesis introduces a proposed explanation which is being investigated through scientific or mathematical research. Thesis statements present arguments based on evidence which is presented throughout the paper, whereas hypotheses are being tested by scientists and mathematicians who may disprove or prove them through experimentation. Here is an example of a hypothesis versus a thesis:

Hypothesis:

Students skip school more often as summer vacation approaches.

This hypothesis could be tested by examining attendance records and interviewing students. It may or may not be true.

Students skip school due to sickness, boredom with classes, and the urge to rebel.

This thesis presents an argument which will be examined and supported in the paper with detailed evidence and research.

Introduction

A paper’s introduction is its first paragraph which is used to introduce the paper’s main aim and points used to support that aim throughout the paper. The thesis statement is the most important part of the introduction which states all of this information in one concise statement. Typically, introduction paragraphs require a thesis statement which ties together the entire introduction and introduces the rest of the paper.

VII. Conclusion

Theses are necessary components of well-organized and convincing essays, nonfiction pieces, narratives , and documentaries. They allow writers to organize and support arguments to be developed throughout a composition, and they allow readers to understand from the beginning what the aim of the composition is.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Find anything you save across the site in your account

A Guide to Thesis Writing That Is a Guide to Life

“How to Write a Thesis,” by Umberto Eco, first appeared on Italian bookshelves in 1977. For Eco, the playful philosopher and novelist best known for his work on semiotics, there was a practical reason for writing it. Up until 1999, a thesis of original research was required of every student pursuing the Italian equivalent of a bachelor’s degree. Collecting his thoughts on the thesis process would save him the trouble of reciting the same advice to students each year. Since its publication, “How to Write a Thesis” has gone through twenty-three editions in Italy and has been translated into at least seventeen languages. Its first English edition is only now available, in a translation by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina.

We in the English-speaking world have survived thirty-seven years without “How to Write a Thesis.” Why bother with it now? After all, Eco wrote his thesis-writing manual before the advent of widespread word processing and the Internet. There are long passages devoted to quaint technologies such as note cards and address books, careful strategies for how to overcome the limitations of your local library. But the book’s enduring appeal—the reason it might interest someone whose life no longer demands the writing of anything longer than an e-mail—has little to do with the rigors of undergraduate honors requirements. Instead, it’s about what, in Eco’s rhapsodic and often funny book, the thesis represents: a magical process of self-realization, a kind of careful, curious engagement with the world that need not end in one’s early twenties. “Your thesis,” Eco foretells, “is like your first love: it will be difficult to forget.” By mastering the demands and protocols of the fusty old thesis, Eco passionately demonstrates, we become equipped for a world outside ourselves—a world of ideas, philosophies, and debates.

Eco’s career has been defined by a desire to share the rarefied concerns of academia with a broader reading public. He wrote a novel that enacted literary theory (“The Name of the Rose”) and a children’s book about atoms conscientiously objecting to their fate as war machines (“The Bomb and the General”). “How to Write a Thesis” is sparked by the wish to give any student with the desire and a respect for the process the tools for producing a rigorous and meaningful piece of writing. “A more just society,” Eco writes at the book’s outset, would be one where anyone with “true aspirations” would be supported by the state, regardless of their background or resources. Our society does not quite work that way. It is the students of privilege, the beneficiaries of the best training available, who tend to initiate and then breeze through the thesis process.

Eco walks students through the craft and rewards of sustained research, the nuances of outlining, different systems for collating one’s research notes, what to do if—per Eco’s invocation of thesis-as-first-love—you fear that someone’s made all these moves before. There are broad strategies for laying out the project’s “center” and “periphery” as well as philosophical asides about originality and attribution. “Work on a contemporary author as if he were ancient, and an ancient one as if he were contemporary,” Eco wisely advises. “You will have more fun and write a better thesis.” Other suggestions may strike the modern student as anachronistic, such as the novel idea of using an address book to keep a log of one’s sources.

But there are also old-fashioned approaches that seem more useful than ever: he recommends, for instance, a system of sortable index cards to explore a project’s potential trajectories. Moments like these make “How to Write a Thesis” feel like an instruction manual for finding one’s center in a dizzying era of information overload. Consider Eco’s caution against “the alibi of photocopies”: “A student makes hundreds of pages of photocopies and takes them home, and the manual labor he exercises in doing so gives him the impression that he possesses the work. Owning the photocopies exempts the student from actually reading them. This sort of vertigo of accumulation, a neocapitalism of information, happens to many.” Many of us suffer from an accelerated version of this nowadays, as we effortlessly bookmark links or save articles to Instapaper, satisfied with our aspiration to hoard all this new information, unsure if we will ever get around to actually dealing with it. (Eco’s not-entirely-helpful solution: read everything as soon as possible.)

But the most alluring aspect of Eco’s book is the way he imagines the community that results from any honest intellectual endeavor—the conversations you enter into across time and space, across age or hierarchy, in the spirit of free-flowing, democratic conversation. He cautions students against losing themselves down a narcissistic rabbit hole: you are not a “defrauded genius” simply because someone else has happened upon the same set of research questions. “You must overcome any shyness and have a conversation with the librarian,” he writes, “because he can offer you reliable advice that will save you much time. You must consider that the librarian (if not overworked or neurotic) is happy when he can demonstrate two things: the quality of his memory and erudition and the richness of his library, especially if it is small. The more isolated and disregarded the library, the more the librarian is consumed with sorrow for its underestimation.”

Eco captures a basic set of experiences and anxieties familiar to anyone who has written a thesis, from finding a mentor (“How to Avoid Being Exploited By Your Advisor”) to fighting through episodes of self-doubt. Ultimately, it’s the process and struggle that make a thesis a formative experience. When everything else you learned in college is marooned in the past—when you happen upon an old notebook and wonder what you spent all your time doing, since you have no recollection whatsoever of a senior-year postmodernism seminar—it is the thesis that remains, providing the once-mastered scholarly foundation that continues to authorize, decades-later, barroom observations about the late-career works of William Faulker or the Hotelling effect. (Full disclosure: I doubt that anyone on Earth can rival my mastery of John Travolta’s White Man’s Burden, owing to an idyllic Berkeley spring spent studying awful movies about race.)

In his foreword to Eco’s book, the scholar Francesco Erspamer contends that “How to Write a Thesis” continues to resonate with readers because it gets at “the very essence of the humanities.” There are certainly reasons to believe that the current crisis of the humanities owes partly to the poor job they do of explaining and justifying themselves. As critics continue to assail the prohibitive cost and possible uselessness of college—and at a time when anything that takes more than a few minutes to skim is called a “longread”—it’s understandable that devoting a small chunk of one’s frisky twenties to writing a thesis can seem a waste of time, outlandishly quaint, maybe even selfish. And, as higher education continues to bend to the logic of consumption and marketable skills, platitudes about pursuing knowledge for its own sake can seem certifiably bananas. Even from the perspective of the collegiate bureaucracy, the thesis is useful primarily as another mode of assessment, a benchmark of student achievement that’s legible and quantifiable. It’s also a great parting reminder to parents that your senior learned and achieved something.

But “How to Write a Thesis” is ultimately about much more than the leisurely pursuits of college students. Writing and research manuals such as “The Elements of Style,” “The Craft of Research,” and Turabian offer a vision of our best selves. They are exacting and exhaustive, full of protocols and standards that might seem pretentious, even strange. Acknowledging these rules, Eco would argue, allows the average person entry into a veritable universe of argument and discussion. “How to Write a Thesis,” then, isn’t just about fulfilling a degree requirement. It’s also about engaging difference and attempting a project that is seemingly impossible, humbly reckoning with “the knowledge that anyone can teach us something.” It models a kind of self-actualization, a belief in the integrity of one’s own voice.

A thesis represents an investment with an uncertain return, mostly because its life-changing aspects have to do with process. Maybe it’s the last time your most harebrained ideas will be taken seriously. Everyone deserves to feel this way. This is especially true given the stories from many college campuses about the comparatively lower number of women, first-generation students, and students of color who pursue optional thesis work. For these students, part of the challenge involves taking oneself seriously enough to ask for an unfamiliar and potentially path-altering kind of mentorship.

It’s worth thinking through Eco’s evocation of a “just society.” We might even think of the thesis, as Eco envisions it, as a formal version of the open-mindedness, care, rigor, and gusto with which we should greet every new day. It’s about committing oneself to a task that seems big and impossible. In the end, you won’t remember much beyond those final all-nighters, the gauche inside joke that sullies an acknowledgments page that only four human beings will ever read, the awkward photograph with your advisor at graduation. All that remains might be the sensation of handing your thesis to someone in the departmental office and then walking into a possibility-rich, almost-summer afternoon. It will be difficult to forget.

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Mary Norris

By Joshua Rothman

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

How to write a thesis statement, what is a thesis statement.

Almost all of us—even if we don’t do it consciously—look early in an essay for a one- or two-sentence condensation of the argument or analysis that is to follow. We refer to that condensation as a thesis statement.

Why Should Your Essay Contain a Thesis Statement?

- to test your ideas by distilling them into a sentence or two

- to better organize and develop your argument

- to provide your reader with a “guide” to your argument

In general, your thesis statement will accomplish these goals if you think of the thesis as the answer to the question your paper explores.

How Can You Write a Good Thesis Statement?

Here are some helpful hints to get you started. You can either scroll down or select a link to a specific topic.

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned

Almost all assignments, no matter how complicated, can be reduced to a single question. Your first step, then, is to distill the assignment into a specific question. For example, if your assignment is, “Write a report to the local school board explaining the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class,” turn the request into a question like, “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” After you’ve chosen the question your essay will answer, compose one or two complete sentences answering that question.

Q: “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” A: “The potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class are . . .”

A: “Using computers in a fourth-grade class promises to improve . . .”

The answer to the question is the thesis statement for the essay.

[ Back to top ]

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned

Even if your assignment doesn’t ask a specific question, your thesis statement still needs to answer a question about the issue you’d like to explore. In this situation, your job is to figure out what question you’d like to write about.

A good thesis statement will usually include the following four attributes:

- take on a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree

- deal with a subject that can be adequately treated given the nature of the assignment

- express one main idea

- assert your conclusions about a subject

Let’s see how to generate a thesis statement for a social policy paper.

Brainstorm the topic . Let’s say that your class focuses upon the problems posed by changes in the dietary habits of Americans. You find that you are interested in the amount of sugar Americans consume.

You start out with a thesis statement like this:

Sugar consumption.

This fragment isn’t a thesis statement. Instead, it simply indicates a general subject. Furthermore, your reader doesn’t know what you want to say about sugar consumption.

Narrow the topic . Your readings about the topic, however, have led you to the conclusion that elementary school children are consuming far more sugar than is healthy.

You change your thesis to look like this:

Reducing sugar consumption by elementary school children.

This fragment not only announces your subject, but it focuses on one segment of the population: elementary school children. Furthermore, it raises a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree, because while most people might agree that children consume more sugar than they used to, not everyone would agree on what should be done or who should do it. You should note that this fragment is not a thesis statement because your reader doesn’t know your conclusions on the topic.

Take a position on the topic. After reflecting on the topic a little while longer, you decide that what you really want to say about this topic is that something should be done to reduce the amount of sugar these children consume.

You revise your thesis statement to look like this:

More attention should be paid to the food and beverage choices available to elementary school children.

This statement asserts your position, but the terms more attention and food and beverage choices are vague.

Use specific language . You decide to explain what you mean about food and beverage choices , so you write:

Experts estimate that half of elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar.

This statement is specific, but it isn’t a thesis. It merely reports a statistic instead of making an assertion.

Make an assertion based on clearly stated support. You finally revise your thesis statement one more time to look like this:

Because half of all American elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar, schools should be required to replace the beverages in soda machines with healthy alternatives.

Notice how the thesis answers the question, “What should be done to reduce sugar consumption by children, and who should do it?” When you started thinking about the paper, you may not have had a specific question in mind, but as you became more involved in the topic, your ideas became more specific. Your thesis changed to reflect your new insights.

How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

1. a strong thesis statement takes some sort of stand..

Remember that your thesis needs to show your conclusions about a subject. For example, if you are writing a paper for a class on fitness, you might be asked to choose a popular weight-loss product to evaluate. Here are two thesis statements:

There are some negative and positive aspects to the Banana Herb Tea Supplement.

This is a weak thesis statement. First, it fails to take a stand. Second, the phrase negative and positive aspects is vague.

Because Banana Herb Tea Supplement promotes rapid weight loss that results in the loss of muscle and lean body mass, it poses a potential danger to customers.

This is a strong thesis because it takes a stand, and because it's specific.

2. A strong thesis statement justifies discussion.

Your thesis should indicate the point of the discussion. If your assignment is to write a paper on kinship systems, using your own family as an example, you might come up with either of these two thesis statements:

My family is an extended family.

This is a weak thesis because it merely states an observation. Your reader won’t be able to tell the point of the statement, and will probably stop reading.

While most American families would view consanguineal marriage as a threat to the nuclear family structure, many Iranian families, like my own, believe that these marriages help reinforce kinship ties in an extended family.

This is a strong thesis because it shows how your experience contradicts a widely-accepted view. A good strategy for creating a strong thesis is to show that the topic is controversial. Readers will be interested in reading the rest of the essay to see how you support your point.

3. A strong thesis statement expresses one main idea.

Readers need to be able to see that your paper has one main point. If your thesis statement expresses more than one idea, then you might confuse your readers about the subject of your paper. For example:

Companies need to exploit the marketing potential of the Internet, and Web pages can provide both advertising and customer support.

This is a weak thesis statement because the reader can’t decide whether the paper is about marketing on the Internet or Web pages. To revise the thesis, the relationship between the two ideas needs to become more clear. One way to revise the thesis would be to write:

Because the Internet is filled with tremendous marketing potential, companies should exploit this potential by using Web pages that offer both advertising and customer support.

This is a strong thesis because it shows that the two ideas are related. Hint: a great many clear and engaging thesis statements contain words like because , since , so , although , unless , and however .

4. A strong thesis statement is specific.

A thesis statement should show exactly what your paper will be about, and will help you keep your paper to a manageable topic. For example, if you're writing a seven-to-ten page paper on hunger, you might say:

World hunger has many causes and effects.

This is a weak thesis statement for two major reasons. First, world hunger can’t be discussed thoroughly in seven to ten pages. Second, many causes and effects is vague. You should be able to identify specific causes and effects. A revised thesis might look like this:

Hunger persists in Glandelinia because jobs are scarce and farming in the infertile soil is rarely profitable.

This is a strong thesis statement because it narrows the subject to a more specific and manageable topic, and it also identifies the specific causes for the existence of hunger.

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

How to Write a Master's Thesis

- Yvonne N. Bui - San Francisco State University, USA

- Description

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

“Yvonne Bui’s How to Write a Master’s Thesis should be mandatory for all thesis track master’s students. It steers students away from the shortcuts students may be tempted to use that would be costly in the long run. The step by step intentional approach is what I like best about this book.”

“This is the best textbook about writing an M.A. thesis available in the market.”

“This is the type of textbook that students keep and refer to after the class.”

Excellent book. Thorough, yet concise, information for students writing their Master's Thesis who may not have had a strong background in research.

Clear, Concise, easy for students to access and understand. Contains all the elements for a successful thesis.

I loved the ease of this book. It was clear without extra nonsense that would just confuse the students.

Clear, concise, easily accessible. Students find it of great value.

NEW TO THIS EDITION:

- Concrete instruction and guides for conceptualizing the literature review help students navigate through the most challenging topics.

- Step-by-step instructions and more screenshots give students the guidance they need to write the foundational chapter, along with the latest online resources and general library information.

- Additional coverage of single case designs and mixed methods help students gain a more comprehensive understanding of research methods.

- Expanded explanation of unintentional plagiarism within the ethics chapter shows students the path to successful and professional writing.

- Detailed information on conference presentation as a way to disseminate research , in addition to getting published, help students understand all of the tools needed to write a master’s thesis.

KEY FEATURES:

- An advanced chapter organizer provides an up-front checklist of what to expect in the chapter and serves as a project planner, so that students can immediately prepare and work alongside the chapter as they begin to develop their thesis.

- Full guidance on conducting successful literature reviews includes up-to-date information on electronic databases and Internet tools complete with numerous figures and captured screen shots from relevant web sites, electronic databases, and SPSS software, all integrated with the text.

- Excerpts from research articles and samples from exemplary students' master's theses relate specifically to the content of each chapter and provide the reader with a real-world context.

- Detailed explanations of the various components of the master's thesis and concrete strategies on how to conduct a literature review help students write each chapter of the master's thesis, and apply the American Psychological Association (APA) editorial style.

- A comprehensive Resources section features "Try It!" boxes which lead students through a sample problem or writing exercise based on a piece of the thesis to reinforce prior course learning and the writing objectives at hand. Reflection/discussion questions in the same section are designed to help students work through the thesis process.

Sample Materials & Chapters

1: Overview of the Master's Degree and Thesis

3: Using the Literature to Research Your Problem

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Developing a Thesis

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Once you've read the story or novel closely, look back over your notes for patterns of questions or ideas that interest you. Have most of your questions been about the characters, how they develop or change?

For example: If you are reading Conrad's The Secret Agent , do you seem to be most interested in what the author has to say about society? Choose a pattern of ideas and express it in the form of a question and an answer such as the following: Question: What does Conrad seem to be suggesting about early twentieth-century London society in his novel The Secret Agent ? Answer: Conrad suggests that all classes of society are corrupt. Pitfalls: Choosing too many ideas. Choosing an idea without any support.

Once you have some general points to focus on, write your possible ideas and answer the questions that they suggest.

For example: Question: How does Conrad develop the idea that all classes of society are corrupt? Answer: He uses images of beasts and cannibalism whether he's describing socialites, policemen or secret agents.

To write your thesis statement, all you have to do is turn the question and answer around. You've already given the answer, now just put it in a sentence (or a couple of sentences) so that the thesis of your paper is clear.

For example: In his novel, The Secret Agent , Conrad uses beast and cannibal imagery to describe the characters and their relationships to each other. This pattern of images suggests that Conrad saw corruption in every level of early twentieth-century London society.

Now that you're familiar with the story or novel and have developed a thesis statement, you're ready to choose the evidence you'll use to support your thesis. There are a lot of good ways to do this, but all of them depend on a strong thesis for their direction.

For example: Here's a student's thesis about Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent . In his novel, The Secret Agent , Conrad uses beast and cannibal imagery to describe the characters and their relationships to each other. This pattern of images suggests that Conrad saw corruption in every level of early twentieth-century London society. This thesis focuses on the idea of social corruption and the device of imagery. To support this thesis, you would need to find images of beasts and cannibalism within the text.

How To Write Your First Thesis

- © 2017

- Paul Gruba 0 ,

- Justin Zobel 1

School of Languages & Linguistics, University of Melbourne SLL, Babel Bldg 608, Melbourne, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

School of Computing & Information Systems, University of Melbourne Comp. Science & Software Engg., Carlton, VIC, Australia

- A practical guide for the entire process of producing a thesis for the first time

- Written by authors with many years of experience advising students

- Provides grounded advice to students who are new to writing extended original research, either undergraduate or graduate coursework

56k Accesses

3 Citations

10 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (9 chapters)

Front matter, transition to your first thesis.

- Paul Gruba, Justin Zobel

Getting Organized

The structure of a thesis, a strong beginning: the introduction, situating the study: the background, explaining the investigation: methods and innovations, presenting the outcome: the results, wrapping it up: discussion and conclusion, before you submit, back matter.

- research writing

- thesis preparation

- dissertation writing

- final project preparation

- thesis structure

- learning and instruction

About this book

Many courses and degrees require that students write a short thesis. This book guides students through their first experience of producing a thesis and undertaking original research. Written by experienced researchers and advisors, the book sets out signposts and tasks to help students to understand what is needed to succeed, including scoping a topic, managing references, interpreting data, and successful completion.

For students, the task of writing a thesis is a transition from structured coursework to becoming a researcher. The book provides advice on:

- What to expect from research and how to work with a supervisor

- Getting organized and approaching the work in a productive way

- Developing an overall thesis structure and avoidance of mistakes such as inadvertent plagiarism

- Producing each major component: a strong introduction, background chapters that are situated in the discipline, and an explanation ofmethods and results that are crucial to successful original research

- How to wrap up a complex project with an extended checklist of the many details needed to be checked before a final submission

Authors and Affiliations

School of languages & linguistics, university of melbourne sll, babel bldg 608, melbourne, australia, school of computing & information systems, university of melbourne comp. science & software engg., carlton, vic, australia.

Justin Zobel

About the authors

Paul Gruba is Associate Professor in the School of Languages and Linguistics, University of Melbourne.

Justin Zobel is Professor in the School of Computing & Information Systems, University of Melbourne.

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : How To Write Your First Thesis

Authors : Paul Gruba, Justin Zobel

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61854-8

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Computer Science , Computer Science (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer International Publishing AG 2017

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-319-61853-1 Published: 06 September 2017

eBook ISBN : 978-3-319-61854-8 Published: 24 August 2017

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XIII, 95

Number of Illustrations : 8 b/w illustrations

Topics : Computer Science, general , Learning & Instruction , Natural Language Processing (NLP) , Popular Social Sciences , Science, Humanities and Social Sciences, multidisciplinary

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

9 Effective Tips for Publishing Thesis As a Book

While they may look alike, a thesis is not a book! The process of publishing thesis as a book is different right from its conception to completion. Created with an intent to target a specific audience, a thesis differs from a book in multiple aspects. Although your thesis topic would surely be relevant to your field of study, it perhaps, can be of interest to a wider audience. In such a case, your thesis can be turned into a book .

In this article, we will shed some light on the possible ways of publishing your thesis as a book .

Table of Contents

What is the Difference Between a Thesis and a Book?

Researchers spend years working on their thesis. A thesis focuses on the research conducted, and is thus published as journal articles . However, in some cases, it may also be published as a book for a wider readership. While both thesis and book writing require effort, time, and are equally longer versions of documents, they are different in several ways.

- A thesis always begins with a question or hypothesis. On the other hand, a book begins with a series of reflections to grab the reader’s attention. To a certain extent, it could be said that while the thesis starts with a question, the book starts with an answer.

- Another major difference between the two is their audience. The content of a thesis, as well as its format and language is aimed at the academic community. However, since the book is written with an intent to reach out to wider audience, the language and format is simpler for easy comprehension by non-academic readers as well.

- Furthermore, thesis is about documenting or reporting your research activities during doctorate; whereas, a book can be considered as a narrative medium to capture the reader’s attention toward your research and its impact on the society.

How to Turn a Thesis into a Book?

The structure of your thesis will not necessarily be similar to the structure of your book. This is primarily because the readership is different and the approach depends on both the audience as well as the purpose of your book. If the book is intended as a primary reference for a course, take the course syllabus into account to establish the topics to be covered. Perhaps your thesis already covers most of the topics, but you will have to fill in the gaps with existing literature.

Additionally, it may be so that you want your book to be a complementary reference not only for one course, but for several courses with different focuses; in this case, you must consider different interests of your audience.

The layout of most thesis involve cross-references, footnotes, and an extensive final bibliography. While publishing your thesis as a book , eliminate excessive academic jargon and reduce the bibliography to reference books for an ordinary reader.

Key Factors to Consider While Publishing Your Thesis as a Book

- Purpose of the book and the problems it intends to solve

- A proposed title

- The need for your proposed book

- Existing and potential competition

- Index of contents

- Overview of the book

- Summary of each book chapter

- Timeline for completing the book

- Brief description of the audience and the courses it would cover

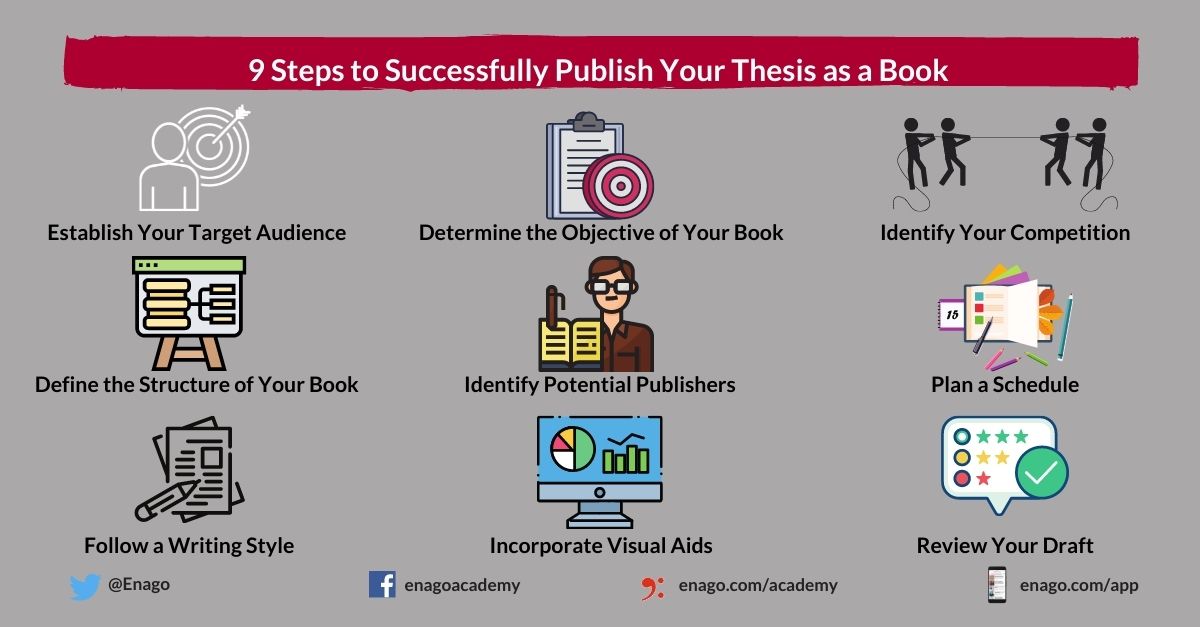

With all of this in mind, here are 9 steps to successfully turn your thesis into a book .

9 Steps to Successfully Publish Your Thesis as a Book!

1. Establish Your Target Audience

Based on the topic of your thesis, determine the areas that may potentially rise interest in your book’s audience. Once you establish your target audience, figure out the nature of book they would like to read.

2. Determine the Objective of Your Book

Reflect on the scope of your book and the impact it would have on your target audience. Perhaps it can be used as a textbook or supplementary for one or more courses. Visualize what the reach of your book may be; if it is a book with an identified local market, an interest that arose in your educational institution, which can be traced to other similar institutions, or if it can have a national or even international reach.

3. Identify Your Competition

Find out which books are already on the market, what topics they cover, what problems do they solve, etc. Furthermore, ask yourself what would be the advantage of your book over those that already exist.

4. Define the Structure of Your Book

If the book is written as part of a curriculum, use that program to define its structure. If it covers several programs, make a list of topics to focus on individually and sequence them in an order based on educational criteria or interest for the potential reader.

5. Identify Potential Publishers

Search for publishers in your country or on the web and the kind of books they publish to see if there is a growing interest in the book you are planning to develop. Furthermore, you can also look at self-publishing or publishing-on-demand options if you already have a captive audience interested in your work.

6. Plan a Schedule

Based on the structure of your book, schedule your progress and create a work plan. Consider that many topics are already written in your thesis, you will only have to rewrite them and not have to do the research from scratch. Plan your day in such a way that you get enough time to fill in technical or generic gaps if they exist.

7. Follow a Writing Style

The writing style depends on the type of book and your target audience. While academic writing style is preferred in thesis writing, books can be written in simpler ways for easy comprehension. If you have already spoken to an interested publisher, they can help in determining the writing style to follow. If you’re self-publishing, refer to some competitor books to determine the most popular style of writing and follow it.

8. Incorporate Visual Aids

Depending on the subject of your book, there may be various types of visual and graphic aids to accentuate your writing, which may prove lucrative. Give due credit to images, diagrams, graphical representations, etc. to avoid copyright infringement. Furthermore, ensure that the presentation style of visual aids is same throughout the book.

9. Review Your Draft

Your supervisor and the advisory council review and refine you thesis draft. However, a book must be proofread , preferably by someone with a constructive view. You can also use professional editing services or just go ahead with an excellent grammar checking tool to avoid the hassle.

Do you plan on publishing your thesis as a book ? Have you published one before? Share your experience in the comments!

good article

Hello. Nice to read your paper. However, I fell on your article while browsing the net for the exact opposite reason and I think you can equally give me some insights. I am interested, as I earlier said, on how to transform my book into a thesis instead, and how I can defend it at an academic level. I am writing a research work on financial digital options trading and have done a lot of back testing with technical analysis that I explain, to rake thousands of dollars from the financial markets. I find the technical analysis very peculiar and would like to defend this piece of work as a thesis instead. Is it possible? Please you can reply me through e:mail thanks

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

The pen is mightier than the sword, they say, and nowhere is this more evident…

- AI in Academia

- Trending Now

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of…

- Promoting Research

Concept Papers in Research: Deciphering the blueprint of brilliance

Concept papers hold significant importance as a precursor to a full-fledged research proposal in academia…

8 Effective Strategies to Write Argumentative Essays

In a bustling university town, there lived a student named Alex. Popular for creativity and…

Facing Difficulty Writing an Academic Essay? — Here is your one-stop solution!

Role of an Abstract in Research Paper With Examples

How Can You Create a Well Planned Research Paper Outline

What Is a Preprint? 5 Step Guide to Successfully Publish Yours!

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- Page Content

- Sidebar Content

- Main Navigation

- Quick links

- All TIP Sheets

- Writing a Summary

- Writing Paragraphs

- Writing an Analogy

- Writing a Descriptive Essay

- Writing a Persuasive Essay

- Writing a Compare/Contrast Paper

- Writing Cause and Effect Papers

- Writing a Process Paper

- Writing a Classification Paper

- Definitions of Writing Terms

- How to Write Clearly

- Active and Passive Voice

- Developing a Thesis and Supporting Arguments

- Writing Introductions & Conclusions

- How to Structure an Essay: Avoiding Six Weaknesses in Papers

Writing Book Reports

- Writing about Literature

- Writing about Non-Fiction Books

- Poetry: Meter and Related Topics

- Revising and Editing

- Proofreading

TIP Sheet WRITING BOOK REPORTS

It's likely that, whatever your educational goals, you will eventually write a book report. Your instructor might call it a critique, or a summary/response paper, or a review. The two components these assignments have in common are summary and evaluation.

Other TIP Sheets on related topics that might prove helpful in developing a book report, depending on the type of book and the specifics of your assignment, include the following:

- How to Write a Summary

- Writing About Non-Fiction Books

- Writing About Literature

Summary AND evaluation Typically, a book report begins with a paragraph to a page of simple information-author, title, genre (for example, science fiction, historical fiction, biography), summary of the central problem and solution, and description of the main character(s) and what they learned or how they changed.

The following example summarizes in two sentences the plot of Jurassic Park :

Michael Crichton's Jurassic Park describes how millionaire tycoon John Hammond indulges his desire to create an island amusement park full of living dinosaurs. In spite of elaborate precautions to make the park safe, his animals run wild, killing and maiming his employees, endangering the lives of his two visiting grandchildren, and finally escaping to mainland Costa Rica.

On the other hand, a thesis statement for a book report reflects your evaluation of the work; "I really, really liked it" is inadequate. Students sometimes hesitate to make judgments about literature, because they are uncertain what standards apply. It's not so difficult to evaluate a book in terms of story elements: character, setting, problem/solution, even organization. (See TIP Sheet Writing About Literature for ideas on how to handle these standard story elements.) Nevertheless, a good thesis statement should include your reflection on the ideas, purpose, and attitudes of the author as well.

To develop an informed judgment about the work, start by asking yourself lots of questions (for more ideas, see "Evaluation" on the TIP Sheet Writing About Literature). Then choose your most promising area, the one about which you have something clear to say and can easily find evidence from the book to illustrate. Develop this into a thesis statement.

For example, here is what one thesis statement might look like for Jurassic Park (notice how this thesis statement differs from the simple summary above):

In Jurassic Park , Crichton seems to warn us chillingly that, in bioengineering as in chaos theory, the moment we most appear to be in control of events is the exact moment control is already irredeemably lost to us.