Javascript is disabled

- Food and drink

- Accessibility

- Group trips

- Objects and stories

- Formal education groups

- Other Groups

- Home Educators

- FAQs for groups

- Learning resources

- Educator CPD and events

- Researchers

- Dana Research Centre and Library

- Digital library

- Ordering library materials

- Research Events

- Science Museum Group Journal

- Press office

- Volunteering

Free entry Open daily, 10.00–18.00

Science Museum Exhibition Road London SW7 2DD

Book your free admission ticket now to visit the museum. Schools and groups can book free tickets here .

The invention of mobile phones

Published: 12 November 2018

At the dawn of the 1980s, engineers raced to build a cellular phone network from scratch, changing the way we communicate forever.

In the 1970s, television audiences all over the world were familiar with the notion of a hand-held two-way communication device, as seen in the hands of Captain Kirk and Mr Spock in the Star Trek series that began in the late 1960s.

The reality was far from this ideal.

Two-way radiophones had been helping police and military personnel to stay in contact in fast-changing situations since before the Second World War.

But these small, private networks required bulky equipment and were inaccessible to the public.

How were mobile phones invented?

In the 1970s, researchers at Bell Labs in the USA began to experiment with the concept of a cellular phone network. The idea was to cover the country with a network of hexagonal cells, each of which would contain a base station.

These base stations would send and receive messages from mobile phones over radio frequencies. Any two adjacent cells would operate at different frequencies, so there was no danger of interference.

The stations would connect the radio signals with the main telecommunications network, and the phones would seamlessly switch frequencies as they moved between one cell and another.

By the end of the 1970s the Bell Labs Advance Mobile Phone System (AMPS) was up and running on a small scale.

Meanwhile, Martin Cooper, an engineer at the Motorola company in the US, was developing something that came close to the Star Trek communicator that had fascinated him since he first saw it on TV.

We knew that people didn’t want to talk to cars, or to houses, or to offices; they want to talk to other people ... What we believed was that the telephone number should be a person rather than a location. Martin Cooper , inventor and entrepreneur

Martin Cooper, the engineer from Motorola, developed the first hand-held phone that could connect over Bell’s AMPS.

Motorola launched the DynaTAC in 1984. It weighed over a kilogram and was affectionately known as The Brick, but it quickly became a must-have accessory for wealthy financiers and entrepreneurs.

At almost $10,000 at today’s prices, it was not for the ordinary telephone subscriber. The 1987 movie Wall Street cemented its status as an icon of wealth and greed when it showed ruthless financier Gordon Gekko, played by Michael Douglas, walking along a beach talking into his DynaTAC.

What were the first mobile phone networks?

The new mobile technology presented a problem in the USA, where the administration wanted to curb the dominance of AT&T, and in Britain, where Margaret Thatcher’s government wanted to move away from British Telecom’s state monopoly on telecommunications.

The US approach offered contracts to two companies in every city, which resulted in a confusing mish-mash of incompatible networks.

The British government took a different approach. In 1982 it licensed two companies, Cellnet and Vodafone, to operate the country’s first cellular phone networks.

The first calls on the UK mobile network

British engineers developed expertise as ‘radio planners’, mapping the topography as well as the distances as they devised the optimal arrangement for the mobile phone network’s base stations. Too far apart and they would leave holes in the coverage; too close together and the signals would interfere with each other.

The first base stations, large and heavy pieces of kit, were installed in 1984. During a trial period engineers drove around the country making calls to patient volunteers to test the signal strength.

Vodafone launched its network on New Year’s Day, 1985, and Cellnet followed a few days later.

They each expected to win up to 20,000 subscribers within ten years. To their astonishment, three years later they had over half a million subscribers, and network coverage reached 90 per cent of the population.

Vodafone Transportable, launched in 1985.

Were mobile phones popular?

A strong market for mobile technology drove the development of smaller and cheaper phones until there was one to suit every pocket.

It was teenagers—always cultural innovators—who developed extraordinary dexterity and (OMG!) a whole new language of abbreviations, initials and emoticons in the 1990s, as sending text messages became an integral part of their social interaction.

No one would have been more surprised at this development than the companies who first invested in cellular mobile phone networks, thinking they might have a market among wealthy businesspeople keen to acquire the latest gadget.

Vodafone 'Transportable' mobile telephone, 1985

Motorola 'MicroTAC Classic' mobile telephone, 1991-2000

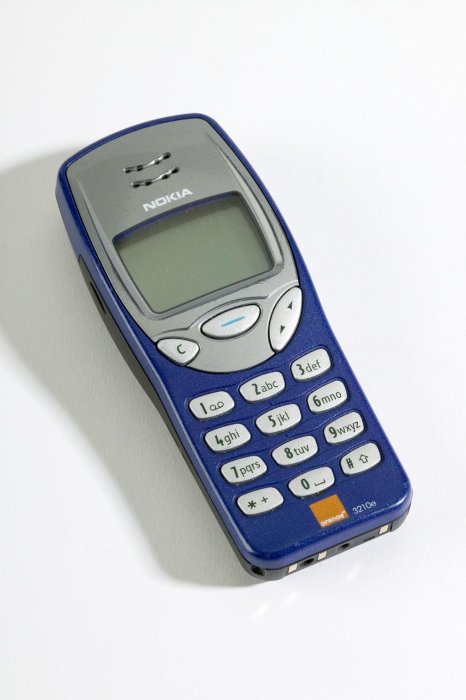

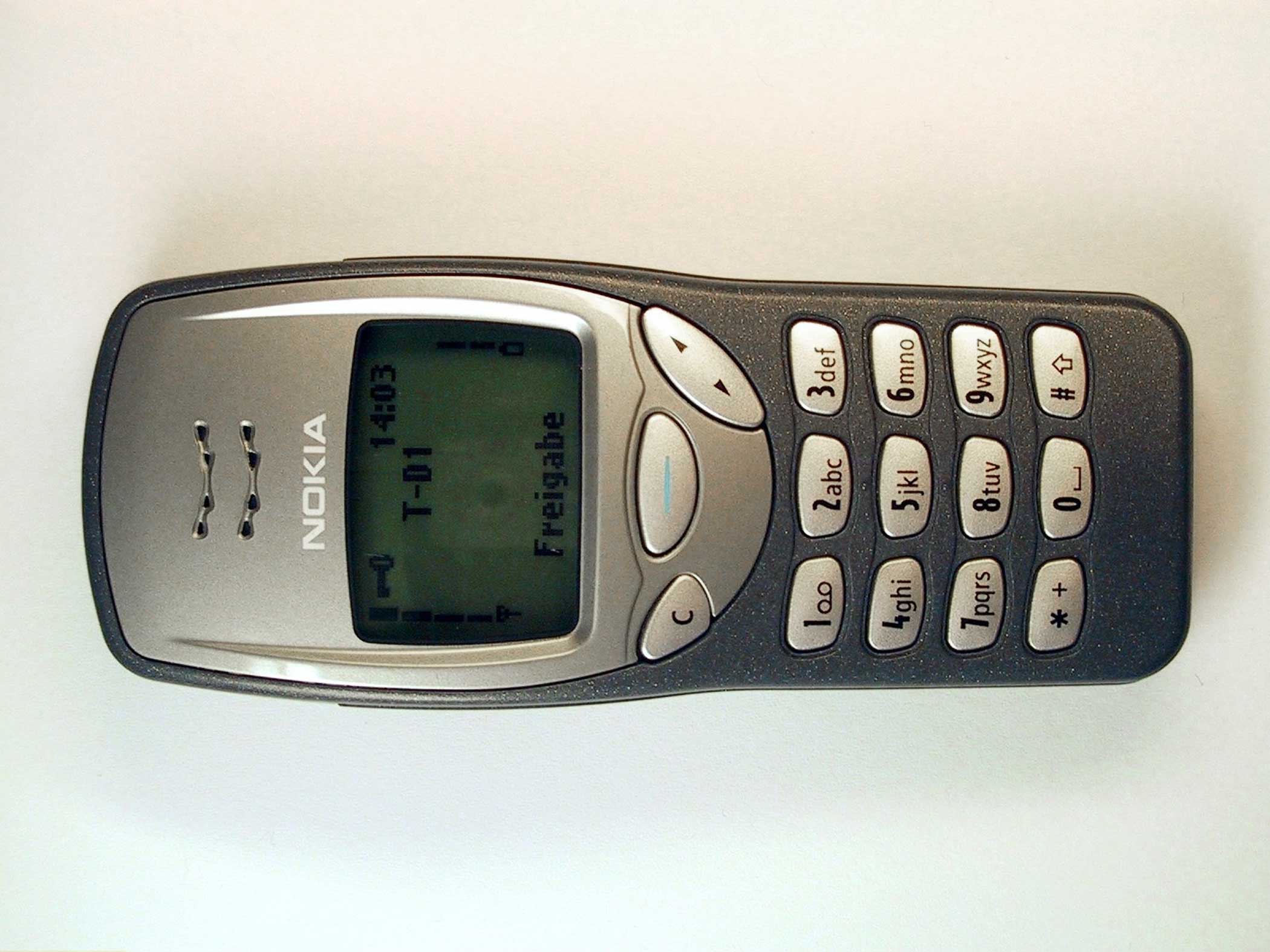

Nokia 3210e mobile phone, Finland, c.1999

Sony Ericsson W800 'Walkman' mobile telephone, 2005-2006

Motorola Timeport L7089 mobile telephone, 1999-2002

Motorola V70 mobile telephone, 2002

Making mobile calling international

Countries besides the UK and USA also developed their own networks, and calls stopped at their borders. Taking their lead from the Nordic countries, which had cooperated to develop networks, a group of European government and industry technocrats came together in 1980 to work towards a common standard.

One of the leading figures was Stephen Temple of the UK’s Department of Trade and Industry (DTI). In 1987 European leaders met in Bonn to sign the agreement that would allow mobile phone users to roam from one country to another, hopping from network to network.

What is GSM?

The common standard agreed in 1987 was called GSM. Originally, it was named for the Groupe Spécial Mobile who had thrashed out the terms, but this subsequently changed to Global System for Mobile Communications.

Unlike the first cellular networks, which had used analogue signals, GSM systems would transmit digitally: they were known as ‘second generation’ or 2G systems.

They would initially use a single radio frequency band, 900 MHz, across Europe, ensuring that users could pick up a signal wherever they were. They would include provision for SMS (short message service, or texting), and would have increased security features.

It wasn’t long before other countries made the decision to adopt the GSM standard, which was a great improvement on what was available in the US.

Nine out of ten people in the world today are now within reach of a terrestrial GSM network. But the rise of smartphone technology has changed the communication landscape again—what will the next mobile revolution look like?

More Information Age stories

A computer in your pocket: The rise of smartphones

Discover how increasingly tiny microprocessors transformed mobile phone technology, changing our lives and our habits in the process.

Robeson sings: the first transatlantic telephone cable

Discover how a concert by singer Paul Robeson tested the possibilities of the new transatlantic telephone cable.

From the first crackly telephone call to the ‘smart’ devices, how technology affects the ways we interact.

- Part of the Science Museum Group

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy and cookies

- Modern Slavery Statement

- Web accessibility

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

5th grade reading & vocabulary

Course: 5th grade reading & vocabulary > unit 3.

- Creating objective summaries | Reading

- How can a text have two or more main ideas? | Reading

- How do writers use examples to get their points across? | Reading

- Interpreting text features | Reading

Inventing Progress: reading informational text; Discovering the Process of Invention 5

Discovering the process of invention.

- Our world runs on technology: gadgets and gizmos like computers, cell phones, and cars that drive themselves. The history of technology is built on story after story of great inventors and their brilliant ideas. But where do these ideas come from? And what does it take to bring them to life—to transform a concept into a product? The work doesn’t stop with an inventor’s ingenuity; in fact, the real work begins after the lightbulb moment.

- There’s a reason that inventors like Thomas Edison and the Wright Brothers are better known than others who created more original inventions. All were skilled at navigating the business side of invention. The process of inventing takes more than an innovative idea alone: it also requires money and business savvy. Products begin as prototypes, or early samples, which have to be tested and approved. Market research tells inventors what consumers want or need and what changes are needed so the product will sell. Inventors find out who will buy their products, what consumers expect the product to do, and the best price to charge. Then comes manufacturing, marketing (or promoting and selling) the product, and applying for patents—which are documents that protect the product from being copied. Finally, the inventor has to sell enough of the product to ensure they make enough money to cover costs and keep the product alive.

- Whew! That’s a lot of risk and a lot of work. So why do inventors bother? Surprisingly, there are more reasons for inventions than you might think. Some inventors, like Patricia Bath, are fueled by humanitarian passion. Bath’s belief that sight is a basic human right led her to invent a laser that removes cataracts, a cloudiness that forms in the lens of an eye. Ferdinand Petzl was a French spelunker, or cave explorer, who wanted safer equipment to explore caves in the mid-1900s. The gear he needed to safely “spider”, or climb down, into the world’s deepest, darkest caves wasn’t available, so he designed and crafted it himself. Petzl used inventions to solve a problem.

- Sometimes inventions happen by accident. Slinkys and playdough are fun novelties that were invented by people who were trying to make something else. Other inventions have evolved over time. Early versions of the camera and the first modern automobile first appeared in the 1800s, but these inventions have since been reinvented and improved many times over. Although we tend to think of inventors as scientists or engineers, many accomplished inventors were neither—they succeeded through trial and error. Thomas Edison is a perfect example: he was a man with little education and no formal training. Edison tried thousands of filament materials before finding the one that led to his invention of the lightbulb.

- Today, most inventions are corporate—that means they’re created by large companies. Companies like Apple and IBM piggyback onto previous inventions to sustain their businesses and generate profits. Instead of one inventor trying to mold an idea into a product, corporations employ a myriad of inventors. They have the resources to manage a crucial but complex step in the invention process: filing for patents. Patents are what keep other people from copying someone else’s idea.

- Patents are legal documents that allow inventors to stop other people from making, using, or selling their invention for a set period of time. Inventors have to submit a patent application to the patent office in their country. Anyone can file a patent, but the process is complicated. In the United States, it takes about two years to get approval after filing. Once a patent expires, the idea behind the invention is available for anyone to use, so inventors try to make as much money as they can before that happens.

- Now you know a little more about the process of invention. So what do you think? Is there something in your imagination waiting to come out into the world?

Practice Question

- (Choice A) Once a patent expires, the idea behind the invention is available for anyone to use. A Once a patent expires, the idea behind the invention is available for anyone to use.

- (Choice B) Not every inventor who files a patent can afford to hire an attorney and an agent. B Not every inventor who files a patent can afford to hire an attorney and an agent.

- (Choice C) All patents are assigned a patent number which is given by the patent office. C All patents are assigned a patent number which is given by the patent office.

- (Choice D) The technical information about an invention includes a drawing that illustrates how the invention works. D The technical information about an invention includes a drawing that illustrates how the invention works.

- (Choice E) Anyone can file a patent, but the process is complicated and it takes years to get a patent approved. E Anyone can file a patent, but the process is complicated and it takes years to get a patent approved.

- (Choice F) Patents are documents that protect an invention from being copied by someone else. F Patents are documents that protect an invention from being copied by someone else.

The 50 Most Influential Gadgets of All Time

T hink of the gear you can’t live without: The smartphone you constantly check. The camera that goes with you on every vacation. The TV that serves as a portal to binge-watching and -gaming. Each owes its influence to one model that changed the course of technology for good.

It’s those devices we’re recognizing in this list of the 50 most influential gadgets of all time.

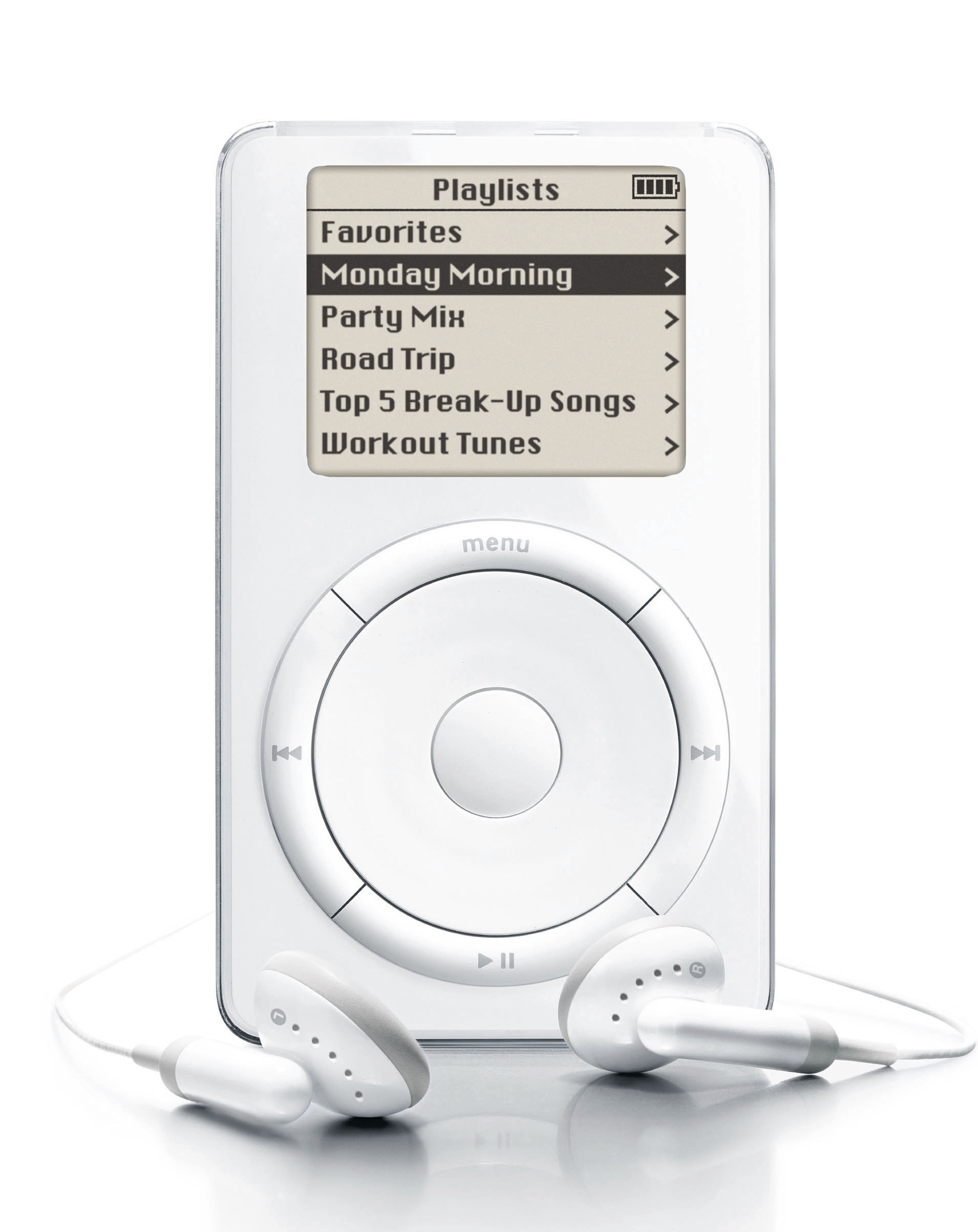

Some of these, like Sony’s Walkman, were the first of their kind. Others, such as the iPod, propelled an existing idea into the mainstream. Some were unsuccessful commercially, but influential nonetheless. And a few represent exciting but unproven new concepts (looking at you Oculus Rift).

Rather than rank technologies—writing, electricity, and so on—we chose to rank gadgets, the devices by with consumers let the future creep into their present. The list—which is ordered by influence—was assembled and deliberated on at (extreme) length by TIME’s technology and business editors, writers and reporters. What did we miss?

( Read TIME’s affiliate link policy .)

50. Apple iPhone

Apple was the first company to put a truly powerful computer in the pockets of millions when it launched the iPhone in 2007. Smartphones had technically existed for years, but none came together as accessibly and beautifully as the iPhone. Apple’s device ushered in a new era of flat, touchscreen phones with buttons that appeared on screen as you needed them, replacing the chunkier phones with slide-out keyboards and static buttons. What really made the iPhone so remarkable, however, was its software and mobile app store, introduced later. The iPhone popularized the mobile app, forever changing how we communicate, play games, shop, work, and complete many everyday tasks.

The iPhone is a family of very successful products. But, more than that, it fundamentally changed our relationship to computing and information—a change likely to have repercussions for decades to come.

49. Sony Trinitron

Renowned journalist Edward R. Murrow famously described television as “nothing but wires and lights in a box.” Of all such boxes, Sony’s Trinitron—launched in 1968 as color TV sales were finally taking off—stands at the fore of memorable sets, in part for its novel way of merging what to that point had been three separate electron guns. The Trinitron was the first TV receiver to win a vaunted Emmy award, and over the next quarter century, went on to sell over 100 million units worldwide.

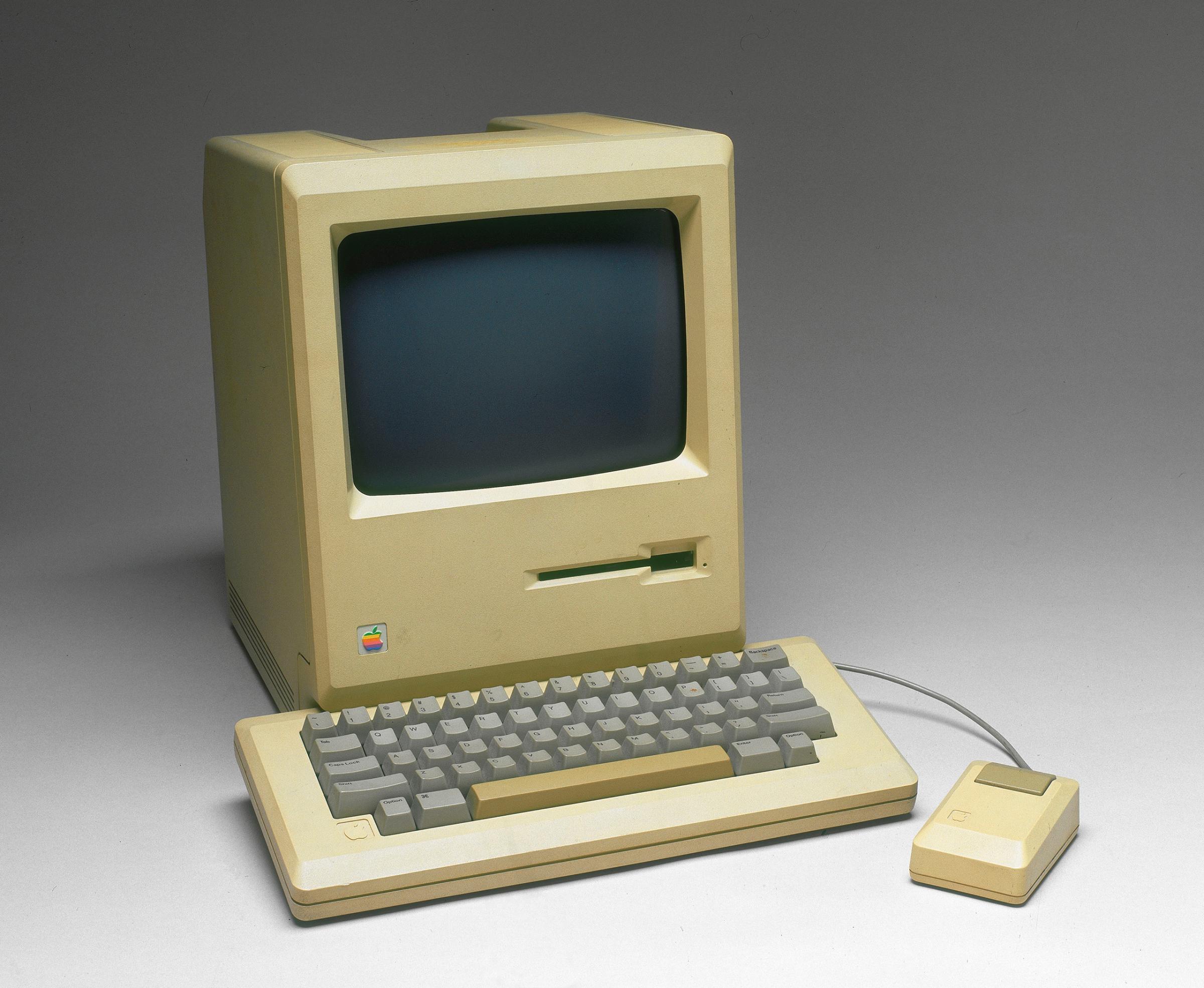

48. Apple Macintosh

“Will Big Blue dominate the entire computer industry? The entire information age? Was George Orwell right about 1984?” That’s how Steve Jobs introduced the ad heralding the arrival of the Macintosh. With its graphical user interface, easy-to-use mouse and overall friendly appearance, the Macintosh was Apple’s best hope to take on IBM. High costs and Microsoft’s successful Windows software conspired to keep the Mac a perennial runner-up. But it forever set the standard for the way human beings interact with computers.

47. Sony Walkman

Sony’s Walkman was the first music player to combine portability, simplicity and affordability. While vinyl records were still the most popular music format, the Walkman—originally the “Sound-About” in the United States—played much smaller cassettes and was small enough to fit in a purse or pocket. It ushered in the phenomena of private space in public created by the isolating effect of headphones. It ran on AA batteries, allowing it to travel far from power outlets. Sony eventually sold more than 200 million of the devices, which paved the way for the CD player and the iPod.

46. IBM Model 5150

What would the computer market look like today without the IBM PC? Sure, the world had personal computers before the 5150 was introduced in 1981. But IBM’s sales pitch—bringing Big Blue’s corporate computing prowess into the home—helped make this a wildly successful product. Even more influential than the 5150 itself was Big Blue’s decision to license its PC operating system, DOS, to other manufacturers. That led to the birth of “IBM Compatibles,” the forerunner to almost all non-Apple PCs out there today.

45. Victrola Record Player

Though the phonograph was invented in 1877, it was the Victor Talking Machine Company’s Victrola that first made audio players a staple in most people’s homes. The device’s amplifying horn was hidden inside a wooden cabinet, giving it the sleek look of a sophisticated piece of furniture. Records by classical musicians and opera singers were popular purchases for the device. Eventually, the Victor Talking Machine Company would be bought by RCA, which would go on to become a radio and television giant.

44. Regency TR-1 Transistor Radio

The Regency’s pocket radio was the first consumer gadget powered by transistors, ushering in an age of high-tech miniaturization. A post-WWII innovation developed by Texas Instruments (which had been making devices for the Navy) and Industrial Development Engineering Associates (which previously put out television antennas for Sears), the $49.95, 3-by-5-inch, battery-powered portable was built on technology developed by Bell Labs. From the transistors that amplified the radio signal to the use of printed circuit boards that connected the components to the eye-catching design, many factors conspired to make the TR-1 a holiday must-buy after its November 1954 launch. And as revolutionary as all this tech was, it only scratches the surface of how the Regency — by ushering in truly portable communications — changed the world overnight.

43. Kodak Brownie Camera

Marketed toward children, carried by soldiers, and affordable to everyone, this small, brown leatherette and cardboard camera introduced the term “snapshot” through its ease of use and low cost. Priced at just $1 (with film that was similarly inexpensive) when it was introduced in February 1900, the Brownie took cameras off tripods and put them into everyday use. For Kodak, the low-cost shooter was the hook that allowed the company to reel in money through film sales. And for the rest of the world, it helped captured countless moments and shape civilization’s relationship to images.

42. Apple iPod

There were MP3 players before the iPod, sure, but it was Apple’s blockbuster device that convinced music fans to upgrade from their CD players en masse. The iPod simultaneously made piracy more appealing, by letting people carry their thousand-song libraries in their pockets, while also providing a lifeline to the flailing music industry with the iTunes Store, which eventually became the world’s biggest music retailer. The iPod’s importance extends far beyond music. It was an entire generation’s introduction to Apple’s easy-to-use products and slick marketing. These people would go on to buy MacBooks, iPhones and iPads in droves, helping to make Apple the most valuable technology company in the world.

41. Magic Wand

A few years after a 2002 episode of Sex and the City revealed the electric neck massager’s cultish adoption as a vibrator, Hitachi dropped its brand from the device. But only in name: the Magic Wand —in service since the late-1960s—likely remains the best-known product stateside made by the $33.5 billion Japanese company. (Hitachi makes everything from aircraft engines to defense equipment, but perhaps nothing as personally stimulating.) Though sex therapists and fans have extolled the Wand’s virtues by analogizing it to cars (the Cadillac, the Rolls Royce), it more closely resembles a microphone, with a white plastic shaft—the wand—and a vibrating head—presumably, the magic.

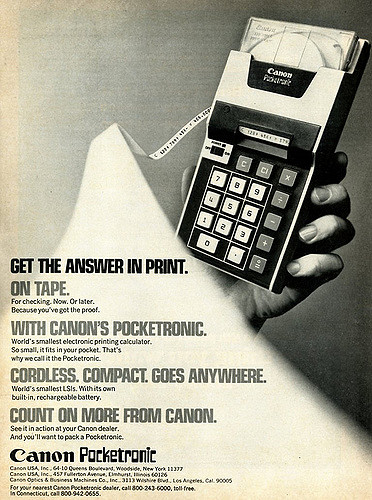

40. Canon Pocketronic Calculator

All business? Hardly. If you trace the path of technology far enough, iconic adding machines like this 1970 classic blazed the trail for the smartphones we’re packing today. Selling for $345 at its launch (a cool $2,165 today), this calculator was built around three circuits that let it add, subtract, multiply, and divide. Thirteen rechargeable battery cells were crammed into the casing to power the calculations, with results spat out onto thermal paper. After the Pocketronic’s launch, circuitry quickly miniaturized and prices shrank to match. Within five years, comparable devices cost just $20, and the first shots were fired in tech’s pricing wars.

39. Philips N1500 VCR

Though it took a long, winding road to mass market success, the videocassette recorder, or VCR, got its start in 1972 with Philips’ release of the N1500. Predating the BetaMax versus VHS format war, the N1500 recorded television onto square cassettes, unlike the VCRs that would achieve mass market success in the 1980s. But featuring a tuner and timer, Philips device was the first to let television junkies record and save their favorite programs for later. But that kind of convenience didn’t come cheap. Originally selling in the U.K. for around £440, it would cost more than $6,500 today. That’s the equivalent of 185 Google Chromecasts.

38. Atari 2600

Its blocky 8-bit graphics looked nothing like the lavish, rousing illustrations on its game jackets, but the black-and-faux-wood Atari 2600 game console was the first gaming box to stir the imaginations of millions. It brought the arcade experience home for $199 (about $800 adjusted for inflation), including a pair of iconic digital joysticks and games with computer-controlled opponents–a home console first. It sold poorly in the months after its launch in September 1977, but when games like Space Invaders and Pac-Man arrived a few years later, sales shot into the millions, positioning Atari at the vanguard of the incipient video gaming revolution.

37. US Robotics Sportster 56K Modem

Beep boop bop beep. Eeeeeeerrrrrrroooooooahhhh ba dong ba dong ba dong psssssssssssh. In the days before broadband, that was the sound the Internet made. Dial-up modems, like the US Robotics Sportster, were many families’ first gateway to the Web. Their use peaked around 2001, as faster alternatives that carried data over cable lines arrived. But millions of households still have an active dial-up connection. Why? They’re cheaper and accessible to the millions of Americans who still lack broadband access.

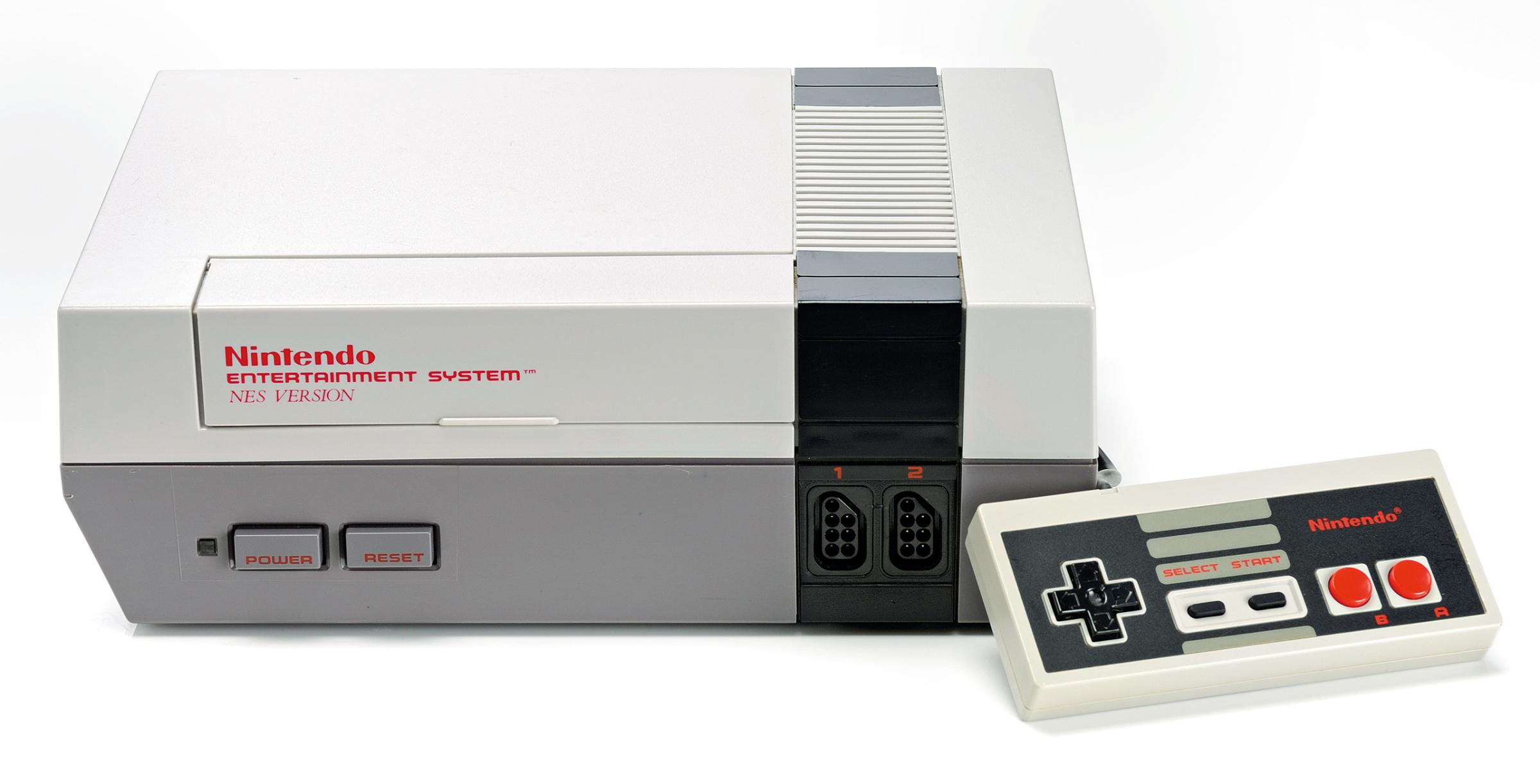

36. Nintendo Entertainment System

Nintendo’s debut front-loading, rain-gray console showed up just in time to save the games industry from its excesses, arriving a few years after a crash that capsized many of the field’s biggest players. The NES was to video gaming what The Beatles were to rock and roll, singlehandedly resuscitating the market after it launched in 1983. The NES heralded Japan’s dominance of the industry, establishing indelible interface and game design ideas so archetypal you can find their DNA in every home console hence.

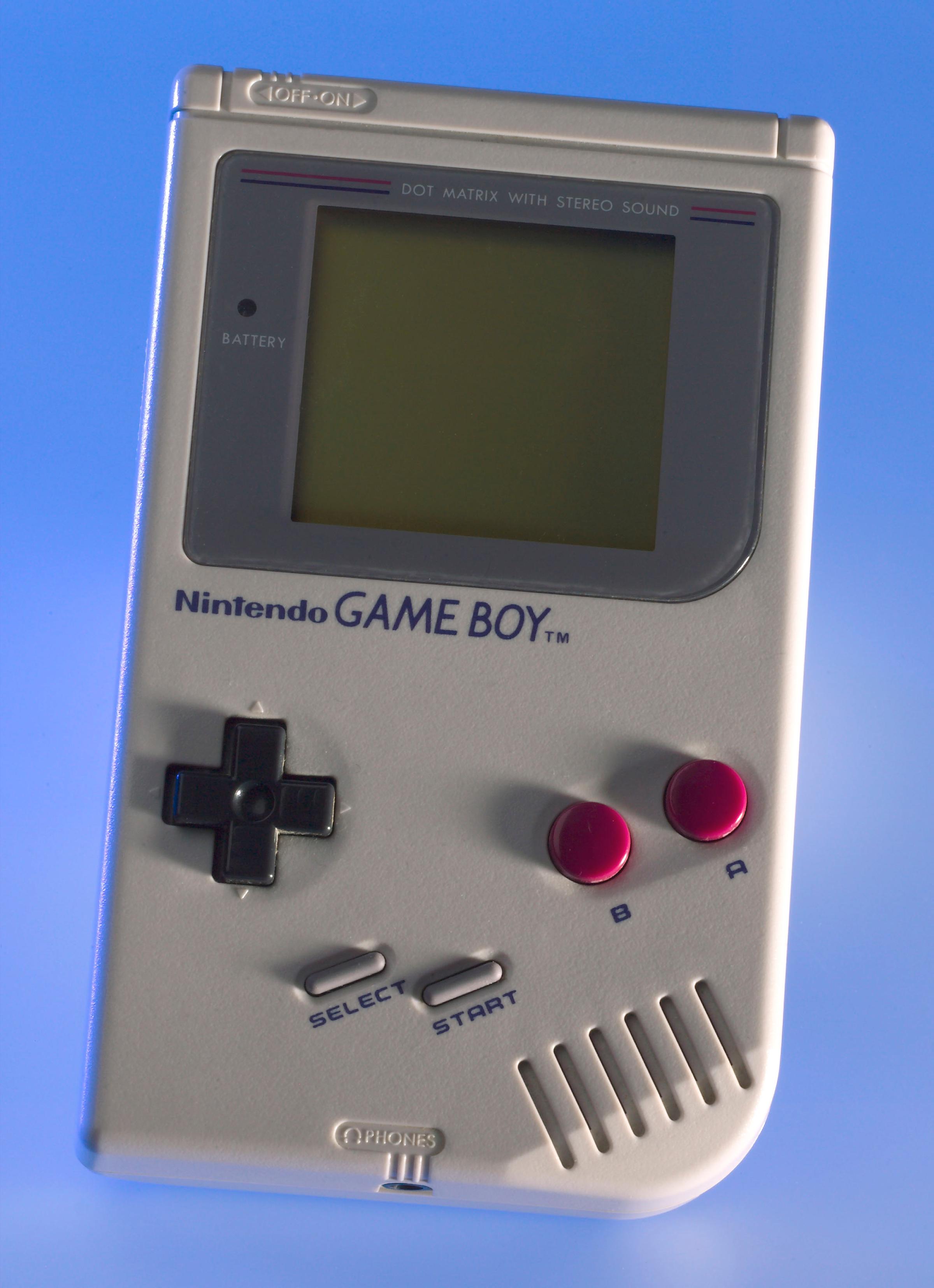

35. Nintendo Game Boy

It’s a wonder we didn’t destroy our eyes gaming on the Game Boy’s tiny 2.6-inch olive green screen, considering how many Nintendo sold (over 200 million when you include the souped-up subsequent Game Boy Advance.) A chunky, somewhat dismal looking off-white object with garish cerise-colored buttons, Nintendo’s 1989 handheld invented the modern mobile game. Its modest power and anemic screen forced developers to distill the essence of genres carried over from consoles. The result: A paradigm shift in mobile game design that’s influenced everything from competing devoted handhelds to Apple’s iPhone.

34. IBM Selectric Typewriter

Turning the plodding, jam-prone mechanical typewriter into a rapid-fire bolt of workplace ingenuity, this Mad Men -era machine worked at the “speed of thought” and marked the beginning of the computer age. The 1961 Selectric model began by introducing changeable typefaces through the typewriter’s iconic, interchangeable, golf-ball-shaped print head. Then in 1964, a magnetic tape model gave the typewriter the ability to store data, arguably making it the world’s first word processor. So in 1965, when the IBM System/360 mainframe rolled out, it only made sense that the Selectric’s keyboard served as the computer’s primary input device.

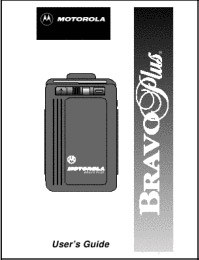

33. Motorola Bravo Pager

Long before cellphones became commonplace, beepers were the way to stay in touch on the go. Early pagers allowed users to send codes to one another, like 411 for “what’s going on” or 911 to indicate an emergency (for obvious reasons). Message recipients would respond by calling the sender via telephone. The Bravo Flex, introduced in 1986, became the best-selling pager in the world, according to Motorola , giving many people their first taste of mobile communication. It could store up to five messages that were 24 characters in length. By the early 1990s, having a pager became a status symbol, paving the way for more advanced communication devices like the two-way pager, the cellphone, and eventually the smartphone.

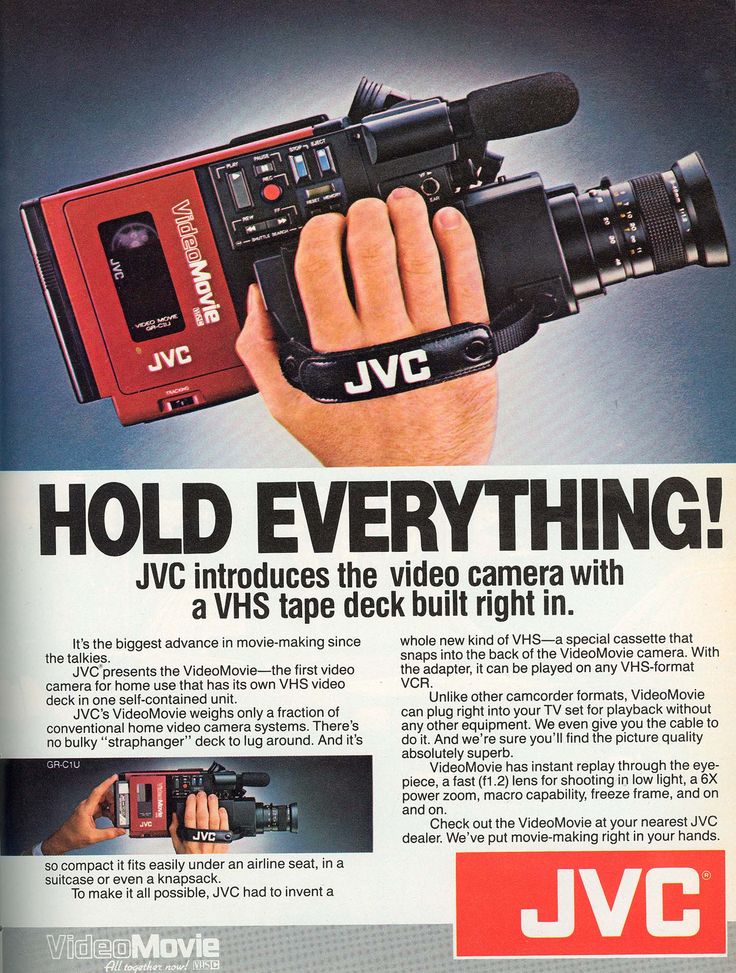

32. JVC VideoMovie Camcorder

From Rodney King and citizen journalism to America’s Funniest Home Videos and unscripted television, the camcorder did as much to change the world from 1983 to 2006 as it did to record it. And though the 1984 JVC VideoMovie wasn’t the first model on the market, it became iconic when Marty McFly lugged it around in 1985’s Back to the Future . The ruby red model was the first to integrate the tapedeck into the camera. (Previously, home videographers had to wear a purse-like peripheral that housed the cassette.) Eventually, camcorders were displaced by flash memory-packing Flip Video cameras and, later, smartphones. But their impact will live forever, like the movies they captured.

31. Motorola Droid

Other Android-powered smartphones existed before the Droid launched in 2009, but this was the first one popular enough to push Android into the spotlight. It cemented Google’s Android platform as the iPhone’s biggest competition. (And sowed a rift between Apple and Google, which had previously been close allies.) Verizon is said to have poured $100 million into marketing the device. It seemingly paid off—although neither companies disclosed sales figures, analysts estimated that between 700,000 and 800,000 Droids were sold in roughly one month following its launch.

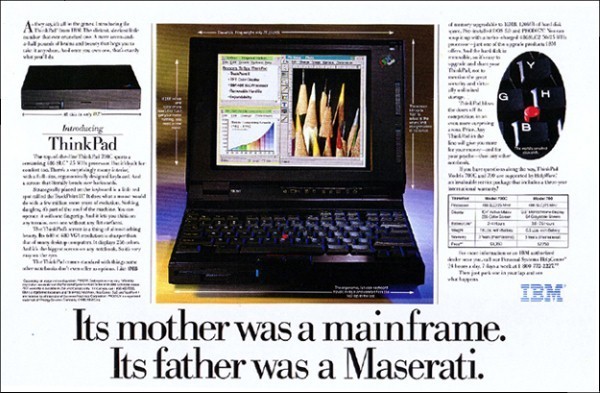

30. IBM Thinkpad 700C

Few products are so iconic that their design remains largely unchanged after more than 20 years. Such is the case with the ThinkPad line of laptops, which challenged the dominance of Apple and Compaq in the personal computing industry during the early 1990s by introducing features that were considered to be innovative at the time . (It’s also part of the permanent collection at New York City’s MoMA.) One of the earliest in the line, the ThinkPad 700C, came with a 10.4-inch color touch screen, larger than displays offered by other competing products. Its TrackPoint navigation device and powerful microprocessors were also considered to be groundbreaking in the early 1990s.

29. TomTom GPS

Like the early Internet, GPS started life as a government-funded innovation. It wasn’t until President Bill Clinton decided in 2000 to fully open the network that it became a massive commerical success. (He was filling a promise made by Ronald Reagan.) Shortly afterwards, companies from TomTom to Garmin introduced personal GPS devices for automotive navigation (like the Start 45) and other uses. Later, combining GPS technology with smartphones’ mobile broadband connections gave rise to multibillion dollar location-based services like Uber.

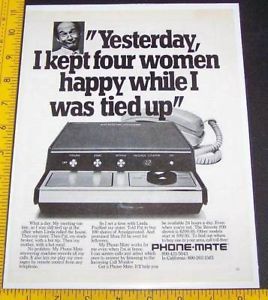

28. Phonemate 400 Answering Machine

The idea of an answering machine weighing more than a few ounces may sound ludicrous by today’s standards. But in 1971, PhoneMate’s 10-pound Model 400 was viewed as a glimpse of the future. The Model 400 was considered the first answering machine designed for the home during a time when the technology was only commonly found in workplaces. It held roughly 20 messages and enabled owners to listen to voicemails privately through an earphone.

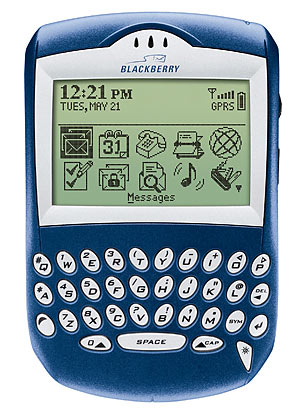

27. BlackBerry 6210

BlackBerry made pocket-sized gadgets for accessing email on-the-go before the 6210, but this was the first to combine the Web-browsing and email experience with the functionality of a phone. The 6210 let users check email, make phone calls, send text messages, manage their calendar, and more all from a single device. (Its predecessor, the 5810, required users to attach a headset in order to make calls.) All told, the 6210 was a pivotal step forward for mobile devices.

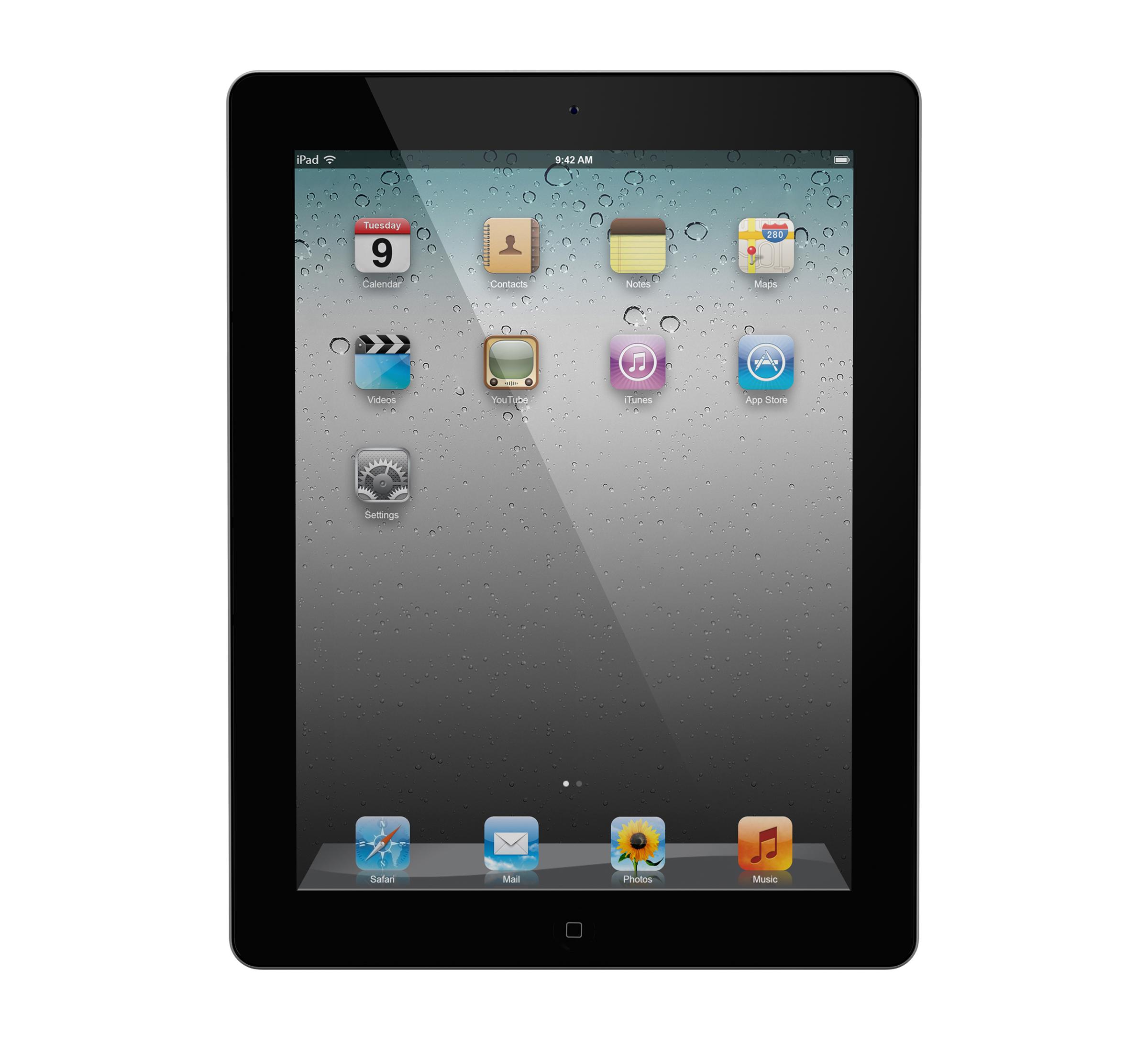

26. Apple iPad

The iPad’s 2010 launch spurred a slew of headlines questioning whether or not the tablet would replace the laptop as the most important personal computer. Apple’s iPad wasn’t the first tablet, but it was radically different from what came before. Earlier devices, like the GriDPad and Palm Pilot, had smaller touchscreens users had to operate with a stylus. Microsoft unveiled a tablet that ran Windows XP in 2002. The problem, however, was that these devices didn’t have interfaces that were well-suited for touch, and they were often clunkier and larger than the iPad. Apple sold 300,000 iPads on its first day in stores, roughly matching the iPhone’s day-one numbers, and has gone on to dominate the market.

25. Commodore 64

Commodore’s 8-bit brown and taupe lo-fi 1982 masterpiece ranks with record-keeper Guinness as the best-selling single computer in history. No surprise, as the chunky, relatively affordable keyboard-housed system—users plugged the whole thing into a TV with an RF box—did more to popularize the idea of the personal home computer than any device since. And it promised to make you more popular, too: “My friends are knockin’ down my door, to get into my Commodore 64,” sang a Ronnie James Dio clone in a power-metal ad spot.

24. Polaroid Camera

Millennials get plenty of flak over their penchant for instant gratification. But that’s a desire that crosses generations. Need proof? When the first affordable, easy-to-use instant shooter, the Polaroid OneStep Land camera, hit the market in 1977, it quickly became the country’s best-selling camera, 40 years before “Millennials” were a thing. That Polaroid photographs so dominated 80s-era family albums and pop culture gives the square-framed, often off-color snaps a retro appeal that today is celebrated by enthusiasts and aped by billion-dollar apps like Instagram.

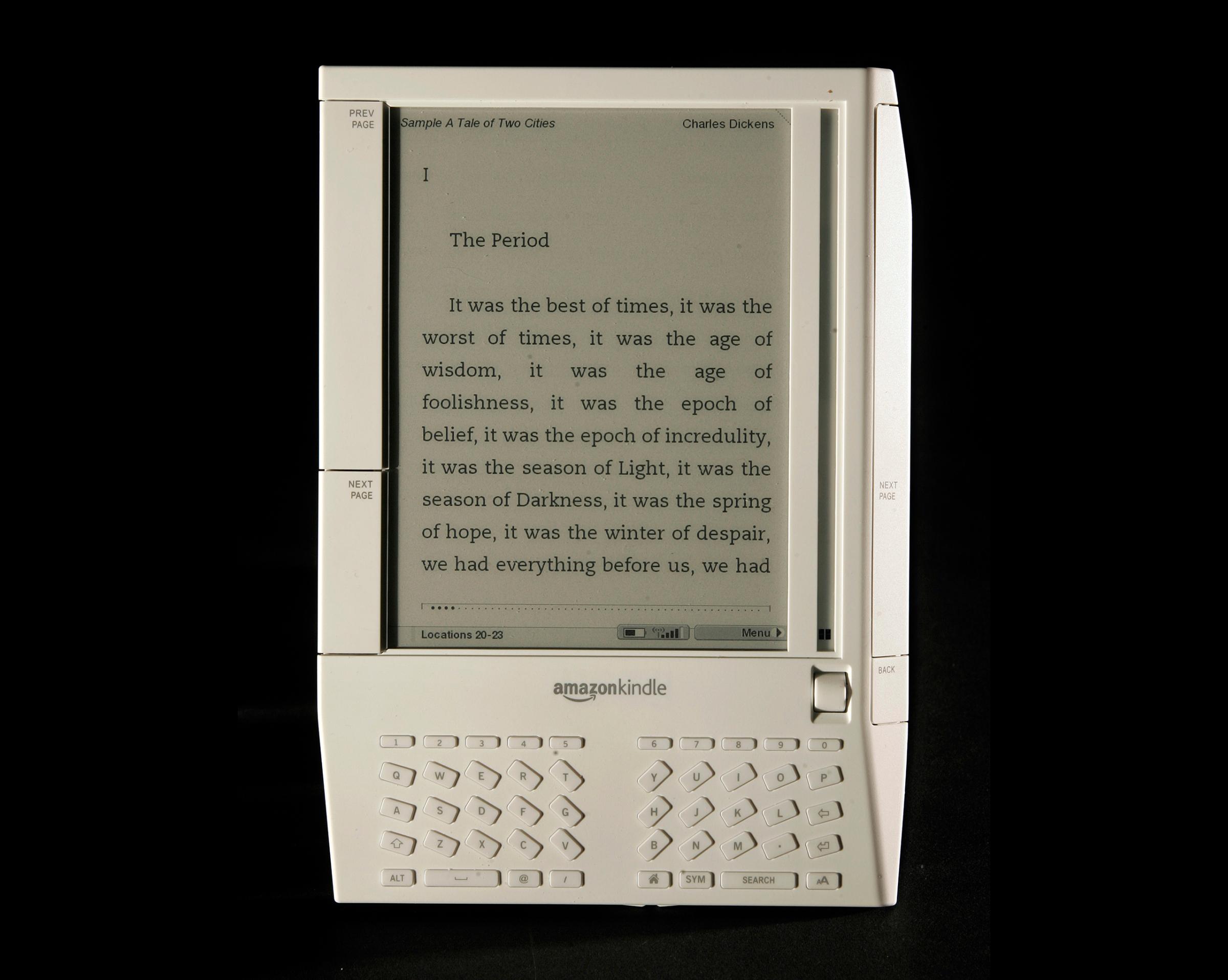

23. Amazon Kindle

Amazon began as an online bookstore, so it’s no surprise that its most influential piece of hardware changed the way we read. The Kindle quickly took over the e-reader market, becoming the best-selling product in the history of Amazon.com in 2010. Follow-up hardware ventures, such as the Kindle Fire Tablet and Echo home assistant, have also found success. The Kindle also marks the beginning of Amazon’s evolution as a digital media company. Today the company has digital stores for music, movies and video games in addition to books.

“How much would you pay never to see another talking frog or battery-powered bunny again?” this magazine asked when the first TiVo was announced in 1999. The box, called a “Personal Video Recorder” at the time, is the forerunner to today’s DVRs. TiVo owners could record shows picked from a digital menu (no more confusing VCR settings) and pause or rewind live television. Much to TV execs’ consternation, the TiVo let viewers of recorded programming breeze past commercials. That the TiVo made it easier than ever to record a TV show gave rise to “time-shifting,” or the phenomenon of viewers watching content when it fits their schedule.

21. Toshiba DVD Player

Electronics manufacturers were already fiddling with standalone optical storage in the early 1990s, but the first to market was Toshiba’s SD-3000 DVD player in November 1996. Obsoleting noisy, tangle-prone magnetic tape (as well as the binary of “original” versus “copy”) the DVD player made it possible to watch crisp digital movies off a tiny platter just 12 centimeters in diameter—still the de facto size for mainstream optical media (like Blu-ray) today.

20. Sony PlayStation

You’d be hard pressed to name a single PlayStation feature that by itself transformed the games industry. It’s been Sony’s obsession with compacting high-end tech into sleek, affordable boxes, then making all that power readily accessible to developers, that’s made the PlayStation family an enduring icon of the living room. Part of Sony’s triumph was simply reading the demographic tea leaves: The company marketed the PlayStation as a game system for grownups to the kids who’d literally grown up playing Atari and Nintendo games. And that helped drive the original system, released in 1994, to meteoric sales, including the PlayStation 2’s Guinness record for bestselling console of all time—a record even Nintendo’s Wii hasn’t come close to breaking.

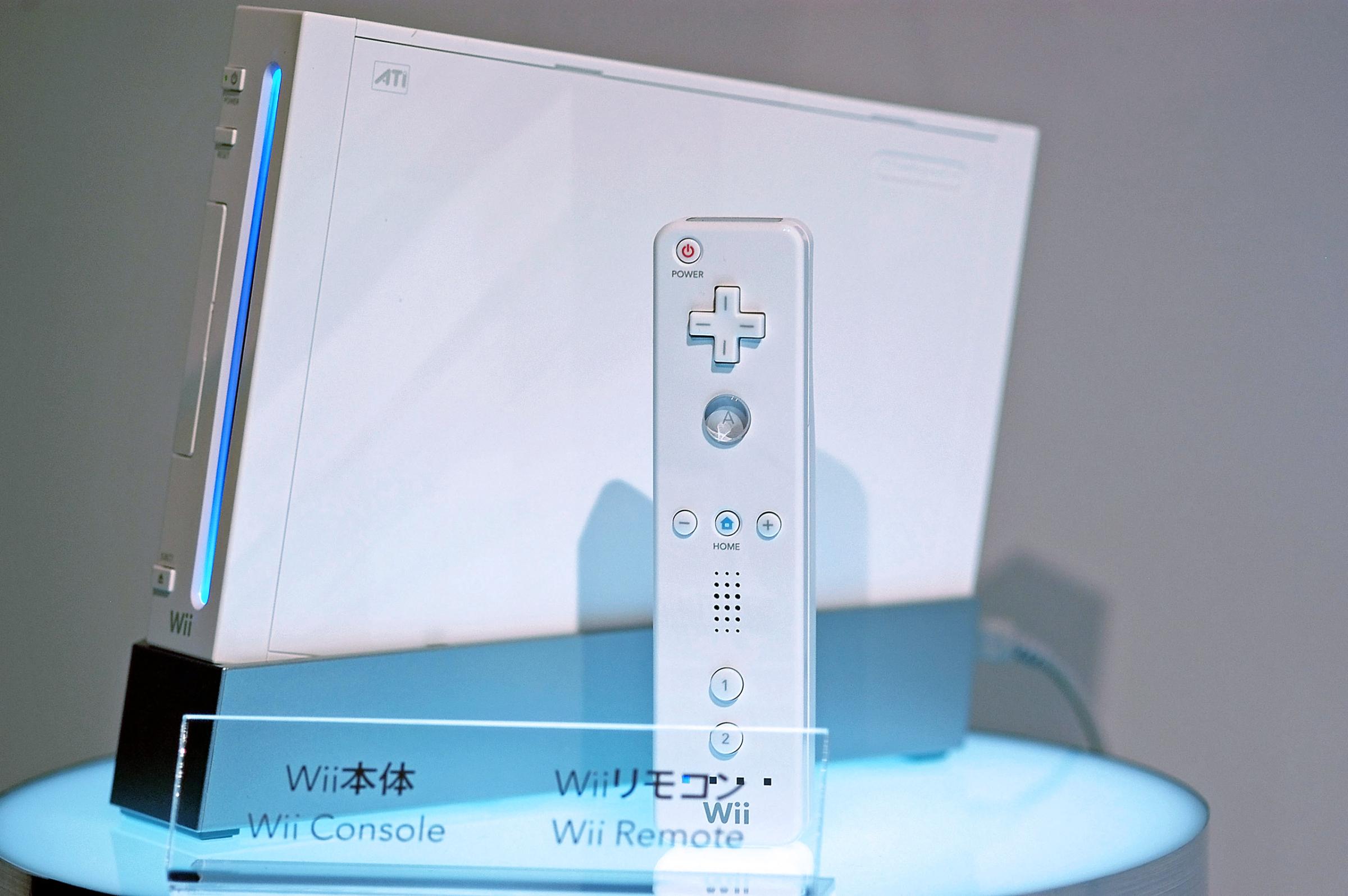

“Thanks to Nintendo’s Satoru Iwata, we’re all gamers now,” went the headline of Wired’s obituary for Nintendo’s beloved president, who died last July. Nothing speaks to Iwata’s legacy more than the company’s game-changing Wii (pun intended). Nintendo’s tiny pearl-white box, released in 2006, and which users engaged with motion control wands, had moms and dads and grandpas and grandmas out of their seats and swinging virtual golf clubs or dancing. No game system has done more to illustrate the omni-generational appeal of interactive entertainment.

18. Jerrold Cable Box

True story: Cable TV was already a thing in the 1950s. Sure, it took Ted Turner in the 1970s and channels like MTV in the 1980s for what we think of as cable TV’s halcyon days to emerge. But decades earlier, the first commercial cable box that would inspire so many others was an unassuming wood-paneled console manufactured by Pennsylvanian company Jerrold Electronics, sporting three-way sliders for dozens of different channels.

17. Nokia 3210

For many, Nokia’s colorful candy bar-shaped 3210 defined the cell phone after it was released in 1999. With more than 160 million sold , it became a bestseller for the Finnish company. The 3210 did more than just introduce the cellphone to new audiences. It also established a few important precedents. The 3210 is regarded to be the first phone with an internal antenna and the first to come with games like Snake preloaded. Gadget reviewers even praised the phone more than 10 years after its launch for its long battery life and clear reception.

16. HP DeskJet

Obsoleting noisy, lousy dot matrix technology, devices like 1988’s HP DeskJet gave computer owners the ability to quietly output graphics and text at a rate of two pages per minute. The DeskJet wasn’t the first inkjet on the market, but with a $995 price tag, it was the first one many home PC users bought. Over the 20 years following the product’s launch, HP sold more than 240 million printers in the DeskJet product line, outputting Christmas letters, household budgets, and book reports by the millions. Even in an increasingly paper-less world, the inkjet’s technology lives on in 3-D printers, which are fundamentally the same devices, only extruding molten plastic instead of dye.

15. Palm Pilot

The original Palm Pilot 1000 solidified handheld computing when it launched in 1996, paving the way for BlackBerry and, eventually, today’s smartphone. The “palm top” computer (get it?) came with a monochrome touchscreen that supported handwriting and was capable of syncing data like contacts and calendar entries to users’ computers. It spawned a device category known as the “personal digital assistant,” or PDA. It wasn’t the first such device—the Apple Newton preceded it—but it was the first one people wanted and bought in droves.

14. Motorola Dynatac 8000x

Motorola’s Dynatac 8000x was the first truly portable cellphone when it launched in 1984. Marty Cooper, an engineer with Motorola at the time, first demonstrated the technology by making what’s regarded as the first public cellular phone call from a New York City sidewalk in 1973. (It was both a PR stunt and an epic humblebrag: Cooper called his biggest rival at AT&T.) The Dynatac 8000x weighed nearly two pounds and cost almost $4,000.

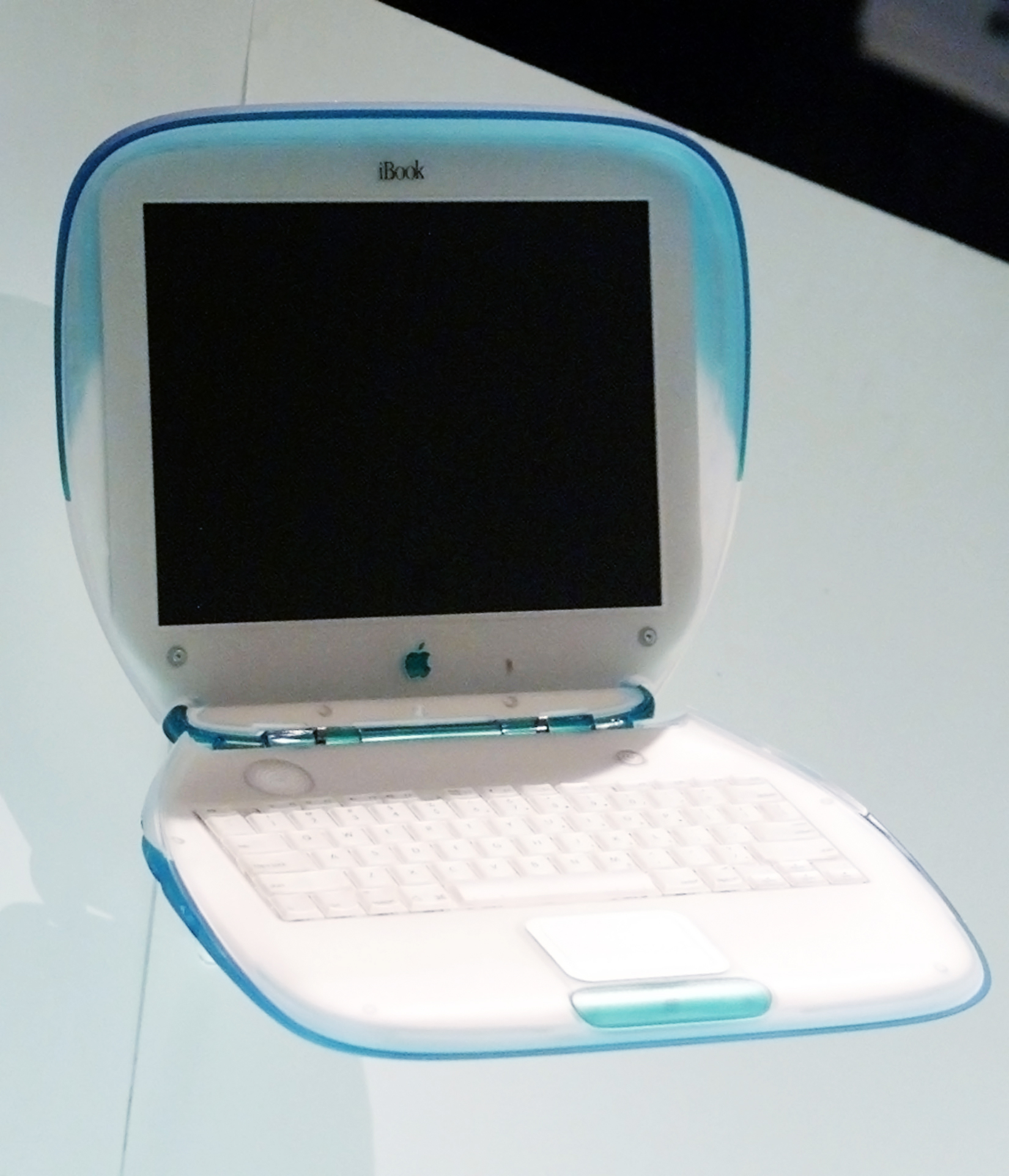

13. Apple iBook

The iBook’s brightly-colored, plastic trim may look dated now, but it was the first laptop to offer wireless networking. Apple’s consumer-oriented portable—for its cool-factor as well as its technology—grew into a serious business. The product’s reveal was a classic example of Steve Jobs’ showmanship at its best. While loading a webpage and showing off the computer’s display at 1999’s MacWorld conference, the Apple co-founder lifted the computer off its table and walked across the stage. The crowd roared in approval. In a gesture, he showed that Wi-Fi was here to stay.

12. Oculus Rift

2016’s Oculus Rift virtual reality headset could wind up a total flop and we’d still grant Oculus a special place in computing history. And not just because Facebook paid $2 billion for the device’s parent company foreseeing a future of social interaction and virtual vacationing provided by VR. Whatever happens next, the Rift, along with ebullient creator Palmer Luckey, will be remembered for reinvigorating the notion of strapping awkward-looking things to our faces in trade for the privilege of visiting persuasively real imaginary places.

11. Sony Discman D-50

Following up on the success of the Walkman, Sony unveiled this portable CD player in 1984, just a year after the music industry adopted the format. The device and later portable CD players helped the compact disc usurp cassettes as the dominant music format in the United States in less than a decade.

10. Roku Netflix Player

An inexpensive upstart running Linux, Roku’s hockey-puck sized Netflix-and-more video streaming box emerged out of nowhere in 2010 to rally waves of cord-cutters who cancelled their cable. What its chunky remote lacked in features, the box more than made up for in software. While at first Apple struggled to rationalize its comparably barren Apple TV-verse, Roku was offering thousands of channels and the most partnerships with the biggest players.

Pedometers have been around for centuries (seriously, look it up), but it was Fitbit that helped bring them into the digital age and to the masses. The company’s first device, released in 2009, tracked users’ steps, calories burned and sleep patterns. Most importantly, it allowed users to easily upload all that data to the company’s website for ongoing analysis, encouragement or guilt. Priced at $99, the Fitbit showed that wearables could be affordable. The company sold more than 20 million of the devices in 2015.

8. Osborne 1

When you think of a portable computer, the Osborne 1 is probably not what comes to mind. But this unwieldy 25-pound machine was heralded by technology critics at the time of its 1981 release— BYTE magazine celebrated that it “fit under an airline seat.” The Osborne’s limitations, like a screen about the size of a modern iPhone’s, kept sales low. The machine’s true influence wasn’t on future gadgets, so much as how they are marketed. The company’s executives had an unfortunate knack for prematurely announcing new products, leading would-be customers to hold off for the better version and thus depressing sales. Marketing students now learn to avoid this deleterious “the Osborne effect.”

7. Nest Thermostat

Developed by the “godfather of the iPod,” Tony Fadell, the Nest Learning Thermostat was the first smart home device to capture mass market interest following its launch in 2011. Pairing the iconic round shape of classic thermostats with a full-color display and Apple-like software, the Nest features considerable processing power. (For instance, its ability to use machine learning to detect and predict usage patterns for heating and cooling a home.) As interesting as the device itself is, the Nest thermostat really turned heads in 2014 when the company behind it was bought by Google for $3.2 billion. The search engine giant turned the device into the center of its smart home strategy with hopes of ushering in an age of interconnected devices that will make everyday living more efficient.

6. Raspberry Pi

The Raspberry Pi is a single-board computer with a price tag to match its tiny size: about $35, without a monitor, mouse or keyboard. Not meant to replace everyday computers, the Pi is being used in classrooms worldwide to help students learn programming skills. With eight million Pi’s sold as of last year, the odds are decent that the next Mark Zuckerberg will have gotten his or her start tinkering with one.

5. DJI Phantom

Small drones may soon be delivering our packages, recording our family get-togethers and helping first responders find people trapped in a disaster. For now, they’re largely playthings for hobbyists and videographers. Chinese firm DJI makes the world’s most popular, the Phantom lineup. Its latest iteration, the Phantom 4 , uses so-called computer vision to see and avoid obstacles without human intervention. That makes it easier for rookie pilots to fly one, making drones more accessible than ever.

4. Yamaha Clavinova Digital Piano

You could argue the Minimoog did far more for music tech, or that the Fairlight was cooler, but visit average U.S. households from the 1980s forward and you’re most likely to encounter the Clavinova . Yamaha’s popular digital piano married the look and compactness of a spinet (a smaller, shorter upright piano) with the modern qualities of a modest synthesizer. With a plausibly pianistic weighted action and space-saving footprint, it’s become a staple for parents looking to bring maintenance-free musicality—you never have to tune it—into households, all without sacrificing huge swathes of living space.

Why is the Segway personal scooter such a potent cultural symbol? Maybe it has something to do with providing a metaphor for increasingly out-of-shape Americans. Perhaps it was seeing a U.S. president fall off one. Weird Al’s “White and Nerdy” video helped, too. The Segway—as hyped and as mocked as it has been—is a defining example of “last mile” transportation, an electric scooter designed to make walking obsolete. (Recently, the idea has been somewhat revived by the emergence of so-called hover boards, which are now also entering a kind of post-fad twilight.) The Segway’s symbolic impact greatly exceeded its commercial success. Unit sales never exceeded the six-figure mark before the firm was purchased by a Chinese interest in 2015 for an undisclosed sum.

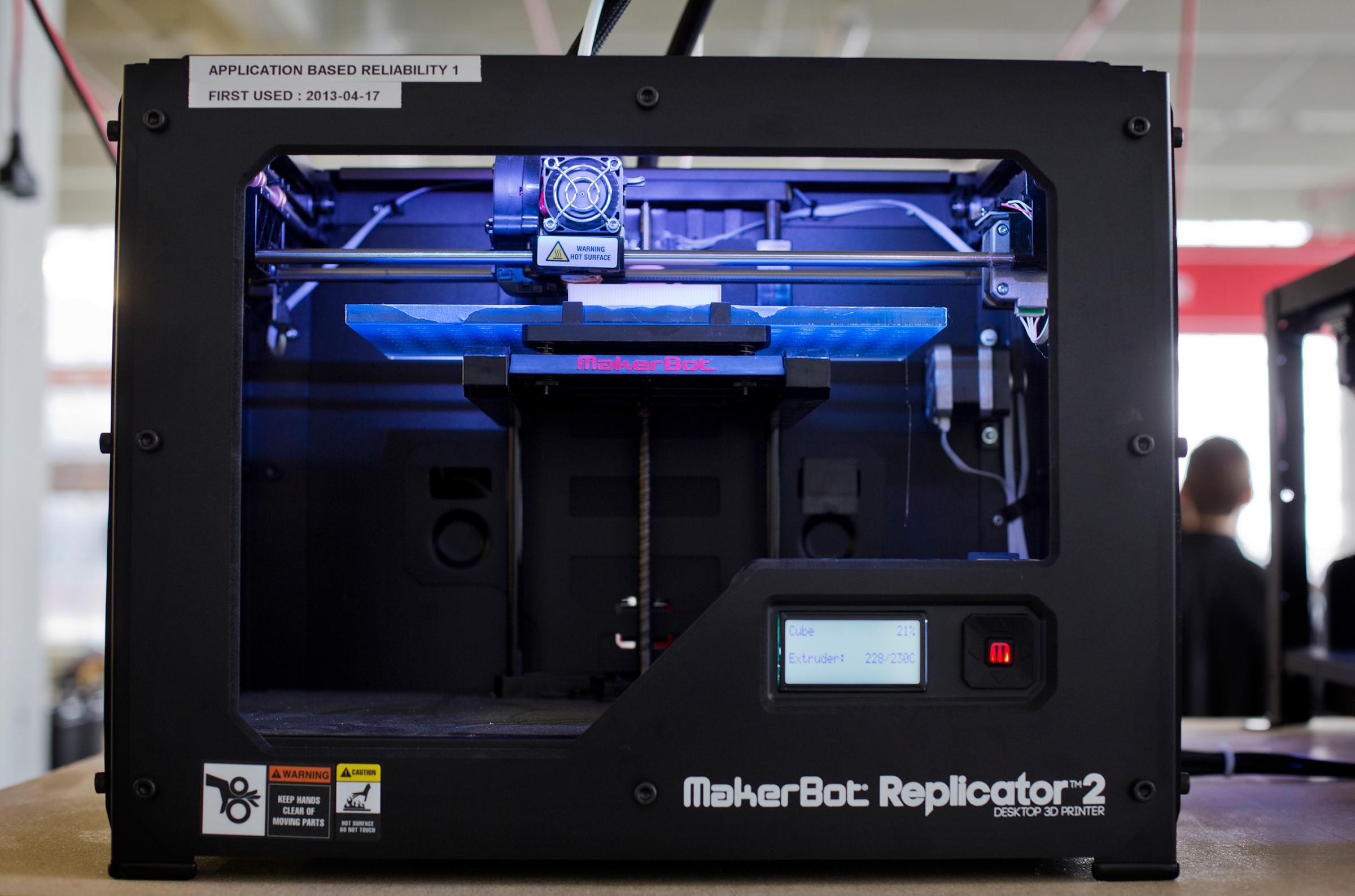

2. Makerbot Replicator

The Makerbot Replicator was neither the first nor the best consumer-level 3-D printer. But it was the model that made the technology widely accessible for the first time, thanks to its sub-$2,000 price tag. The Replicator used inkjet printer-like technology to extrude hot plastic that took three-dimensional form as artwork, mechanical parts and more. As a company, Makerbot’s future is uncertain. But the firm’s equipment helped bring 3-D printing into the mainstream and is a fixture of many American classrooms.

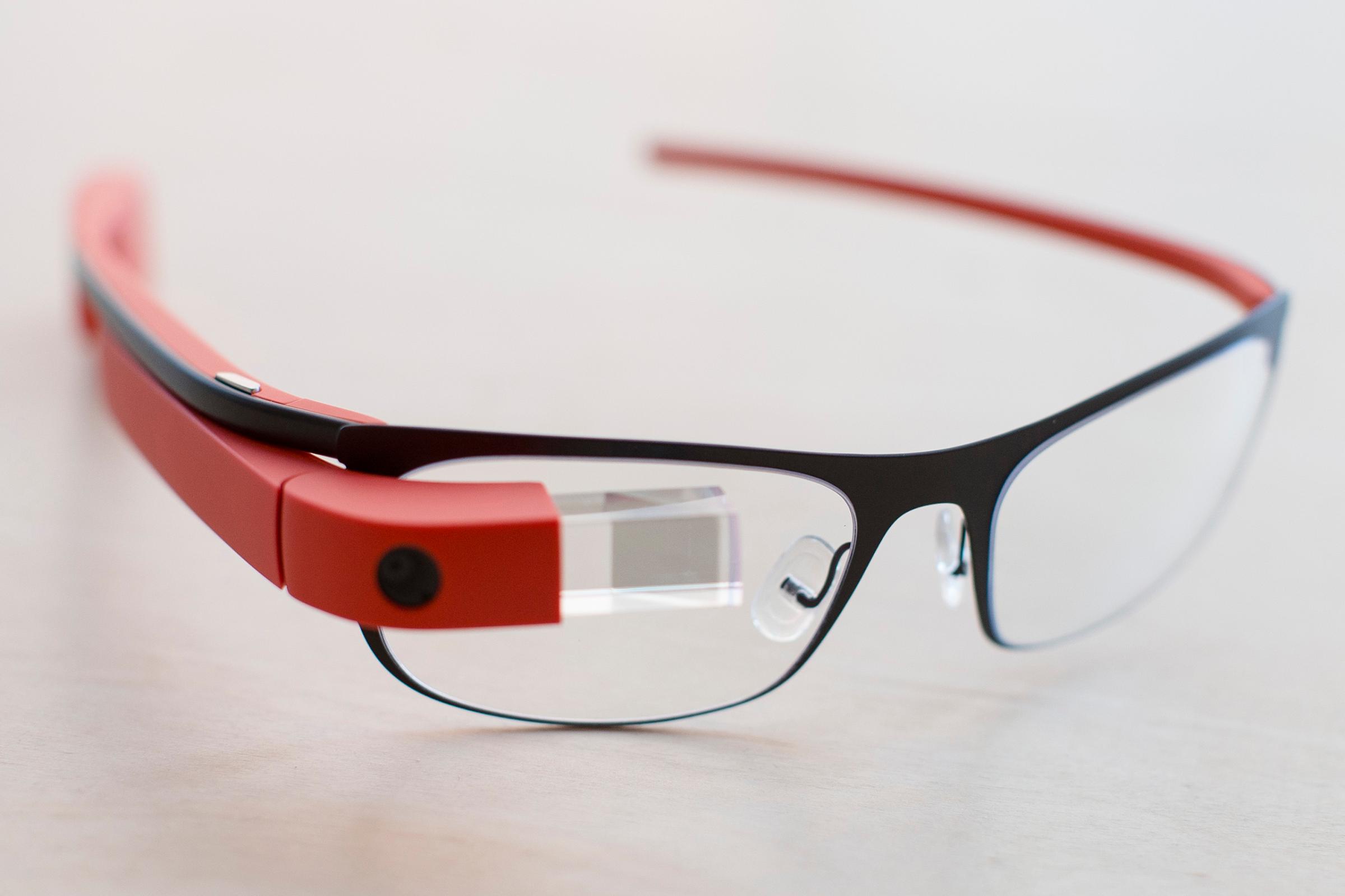

1. Google Glass

Google Glass, which cost $1,500 for those invited to a sort of public beta test, never took off. The relatively powerful head-mounted computer provided important signals for the future of wearable technology. Glass showed that designers working on computing devices that are worn face a different set of assumptions and challenges. Glass, for example, made it easy for users to surreptitiously record video, which led some restaurants, bars and movie theaters to ban the device. Glass also showed the potential pitfalls of easily identifiable wearables, perhaps best proven by the coining of the term “Glassholes” for its early adopters. While Glass was officially shelved in 2015, augmented reality—displaying computer-generated images over the real world—is a concept many companies are still trying to perfect. Google included.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- The New Face of Doctor Who

- Putin’s Enemies Are Struggling to Unite

- Women Say They Were Pressured Into Long-Term Birth Control

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- Boredom Makes Us Human

- John Mulaney Has What Late Night Needs

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Matt Peckham at [email protected]

101 Gadgets That Changed The World

The alarm clock. The personal computer. The smartphone. The radio. You know the greatest gadgets of all time (and youve probably owned most of them), but which has changed the world more than any other?

The alarm clock. The personal computer. The smartphone. The radio. You know the greatest gadgets of all time (and you've probably owned most of them), but which has changed the world more than any other?

101. Duct Tape

NASA astronauts have used it to make repairs on the moon and in space. The MythBusters built a boat and held a car together with the stuff. Brookhaven National Laboratory fixed their particle accelerator with it. And enthusiasts have used it to make prom dresses and wallets. You might say it's a material, not a gadget, but trust us: Duct tape is the ultimate multitool.

100. Fiberglass Fishing Rod

When hostilities in Asia curtailed bamboo imports, rod producers like Shakespeare, Phillipson, and Montague needed a new material to keep anglers equipped with low-cost, quality tackle in the '50s and '60s. Fiberglass fit the bill.

99. Stapler

No office supply has enjoyed a star turn quite like that of the stapler, which had its breakthrough role in the comedy Office Space. Much of the movie's plot revolved around Milton Waddams's beloved red Swingline, but it was only in 2002, three years after the film's release--and in response to demand from fans--that Swingline went to market with a red stapler.

Before it unveiled the Roomba Floorvac for the home market in 2002, iRobot built land-mine-clearing robots, which used the so-called crop circle algorithm. This very same technology was adapted to make the Roomba circle and sweep autonomously. Within a year of its launch, iRobot's Roomba Floorvac was the top gift request on American wedding registries, and sales of the revolutionary vacuum cleaner surpassed the combined total number of all mobile robots previously sold.

97. Aerosol Spray Can

In 1941, the USDA's Lyle Goodhue and William Sullivan used the newly discovered refrigerant, Freon, to enable the deployment of a lethal (to critters, anyway) mist by American troops fighting on insect-infested fronts. The "bug bomb" cocktail, held in a 16-ounce steel canister, consisted of Freon-12, sesame oil and pyrethrum (the last is a natural insecticide derived from chrysanthemum blooms).

96. Quick-Release Ski Binding

Prior to the introduction of this gadget, the ski hill could be an unforgiving place. Strapped to two planks, the skier was always one tough tumble away from catastrophic injury. It was one such break--a severe spinal fracture--that motivated Norweigan-American skiing champion Hjalmar Hvam to conceive the first safety binding in 1937. "When I came out of the ether I called the nurse for a pencil and paper," he once wrote. "I had awakened with the complete principle of a release toe iron." Subsequent developments in safety bindings changed the perception of skiing from a high-risk endeavor to a leisurely pursuit, and the sport boomed.

95. Super Soaker

Originally dubbed the Power Drencher when it debuted in 1989, the Super Soaker was the brainchild of NASA engineer Lonnie Johnson. The idea for the world's greatest squirt gun grew out of Johnson's lab work on a heat pump. He told the AP in 1992, "I was watching the stream of water come out of the nozzle and stream across the bathroom and strike a towel. The curtains were swirling around the bathroom. It was pretty impressive. I thought, 'That would make a pretty neat water gun.'" Since, no fewer than two dozen Super Soaker models have contributed to backyard mayhem--and none is more coveted than the CPS 2000 Mk1. The most powerful water gun ever manufactured, it shoots nearly 1 liter of water per second up to 50 feet. The Mk1 was discontinued soon after its release, but it's available on eBay for a cool $350.

94. Blender

Stephen Poplawski invented the blender in 1922, but his name is not the one most often associated with the gadget. That honor belongs to Fred Waring--an orchestra leader in Pennsylvania who, in 1936, offered financial backing to a tinkerer named Frederick Osius who was developing a similar invention. One reason for Waring's interest: He could use Osius's widget to puree raw vegetables for the ulcer diet his doctors prescribed. The Waring Blender debuted in 1937 and cost $29.75; by 1954 one million of the devices had been sold.

As a publishing luminary of the expatriate bohemian scene in late-'20s Paris, Caresse Crosby helped launch the careers of D.H. Lawrence, Ernest Hemingway and James Joyce. Years earlier, as a 19-year-old Manhattan socialite, she laid the groundwork for a fashion revolution when she and the family maid used two silk handkerchiefs, pink ribbon, and a cord to produce a forerunner to the modern bra. She patented her "backless brassiere" in 1914 and then sold the patent to the Warner Bros. Corset Co. the following year for $1500. Writing later in life, she said: "I can't say the brassiere will ever take as great a place in history as the steamboat, but I did invent it."

92. Picinic Cooler

As the American populace went forth after World War II into the woods to camp, onto the lakes to fish, and into the parking lots to tailgate, it required a gadget capable of keeping beer cool and food from spoiling. The portable cooler, patented in 1953 by Richard Laramy and popularized by the Coleman Company, was that obvious, but essential device.

91. Digital Video Recorder

When ownership of this gadget crept past 1 million in 2002, TV and advertising execs worried aloud that DVRs, by enabling viewers to skip commercials, were surefire TV killers. "There's no Santa Claus," one CEO said. "If you don't watch the commercials, someone's going to have to pay for television and it's going to be you." Fast forward to today: 40 percent of households have a DVR; whether out of habit or laziness almost 50 percent of DVR users still watch ads; and the networks have, on average, seen ratings jump 10 percent, thanks to playback.

The Zippo, that stalwart status symbol of the smoky second half of the 20th century, was born in 1932 in the most inauspicious of settings: a rented room over the Rickerson and Pryde auto shop in tiny Bradford, Penn. Equipped with a kitchen hotplate for soldering, a used welding kit, and a punch press, founder George Blaisdell and two employees went to work. In the first month of production, January 1933, they produced 82 lighters. In February, output jumped to 367. By 2006, the total number of Zippo lighters surpassed 425 million lighters. And now, there's a Zippo app for the iPhone and the Droid phone that allows users to recreate the Zippo moment--when a concert audience raises its lighters in the air. The digital Zippo operates just like the real thing, opening with a flick of the wrist, lighting with a swipe of the flint wheel and mimicking real flame movement as the user waves his phone in the air.

89. Teflon Pan

In 1938 Roy Plunkett discovered PTFE, or polytetrafluoroethylene, at the DuPont research laboratories while working with gases related to Freon refrigerants. He accidentally froze and compressed a sample of tetrafluoroethylene gas into a white, waxy solid, creating a polymer so slick that virtually nothing sticks to it or is absorbed by it. Today, manufacturers apply it to cookware by roughening a pan's surface through sandblasting. A nonstick coating--often referred to as DuPont's proprietary Teflon--is embedded in a primer that's applied to the roughened surface.

88. Flash Drive

Toshiba engineer Fujio Masuoka developed the concept of flash memory--so-called because the erasure process reminded a colleague of a camera flash--in the early 1980s. But the good ship flash drive needed a way to dock. Intel's Ajay Bhatt and his Universal Serial Bus (USB), which was introduced in 1996, provided part of the solution. But data still didn't travel well until 2000, when the first USB flash-drive stick, with 8 megabytes of storage, arrived.

87. Ginsu Knife

Originally known as the "Eversharp" brand of blades from the Scott Fetzer Co. of Freemont, Ohio, Ginsu knives could cut through nails, tin cans, radiator hoses--and still slice a tomato paper thin. But wait--there's more! The company's multibillion-dollar success was as much about the marketing as the product. The late-night ads begun by Ed Valenti and Barry Becher in 1978 ushered in the era of the infomercial, and made Ginsu the most memorable brand ever hocked on American TV.

86. Hearing Aid

According to the National Institutes of Health, only one out of five people who could benefit from a hearing aid actually wear one.

85. Sunglasses

Ten years after founding the Foster Grant plastic company in 1919 to make hair accessories for women, Sam Foster switched his focus to a new consumer product--sun-blocking eyewear. Targeting the throngs of beachgoers in Atlantic City, Foster started selling his wares--America's first mass-produced plastic lens sunglasses--at the Woolworth's on the oceanfront boardwalk. Foster's business boomed, prompting him to adopt the manufacturing technique known "injection molding" in 1934, which revolutionized American plastic production.

84. Drip Coffeemaker

In 1972, the Mr. Coffee machine simplified a brewing process that had been long dominated by traditional percolators. The machine's success, however, was also an early example of celebrity spokesmanship: When Joe DiMaggio became the face of the brand, Mr. Coffee machines became the runaway best-selling model in the United States. (Its success was even spoofed in the 1985 film Back to the Future: The DeLorean time machine is powered by a "Mr. Fusion Home Energy Reactor.") Today, approximately 14 million drip coffee makers are sold each year in the U.S.

83. Toaster

82. flashlight.

Although a flashlight is a relatively simple device--a small electric bulb with a power switch--it wasn't invented until 1896 simply because it required a portable power source: the dry cell battery. Early carbon filament bulbs were inefficient and the batteries weak, mustering just enough current to keep the light on for a few seconds at a time--hence, flashlight.

.css-cuqpxl:before{padding-right:0.3125rem;content:'//';display:inline;} The Best of Innovation .css-xtujxj:before{padding-left:0.3125rem;content:'//';display:inline;}

10 Smart Accessories for Your Car

Here's How to Get Dessert Delivered By Drone

The Skyscraper of the Future Is Made of Wood

This Brand Is Bringing NASA-Style Innovation Into the World of Men's Fashion

New Paperlike Battery Can Withstand Extreme Cold

GE Opened a Whole Factory Just For 3D Printing Metal

Self-Cleaning Material Washes Away Stains With Sunlight

Best New Gadgets

The Best Doorbell Cameras for Surveillance

The 4 Best Smart Bird Feeders for Your Backyard

The Best Wireless Security Cameras for Your Home

The 8 Best Smart Locks for Your Home, Tested

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Rob Beschizza

History's Greatest Gadgets

It's not all about circuits, silicon and stock options: mankind's been making technology since the dawn of time. Here's ten of the most wonderful gadgets from centuries—and millenia—past. No "ThyPhone" jokes, if you please!

It took scientists a century—and the help of a $500,000 x-ray tomography system—to finally unravel the Antikythera Mechanism's mysteries . Discovered in 1900 amid the remains of an ancient shipwreck, the device survived only as a heavily corroded mechanism and countless scattered lumps of metal. At first, it played second fiddle to the classical statues found alongside it. With the discovery that it contained a differential gear—thought to be an 18th-century invention—its mystery deepened.

Confirmed to be the remains of a fully-functional mechanical computer in 2006, the mechanism is perhaps a achievement of the engineers of ancient Rhodes—and a way to sail from Alexandria to Athens without getting lost.

__ The Baghdad Battery __ * c. 250 AD *

No-one knows exactly what these alleged ancient batteries were used for. Discovered near Baghdad in the 1930s, they appear to be galvanic cells: terracotta urns with a copper and iron assembly poking out the stoppered top. Filled with an acidic agent, a chemical reaction between the two metals produces electricity.

Though providing only a feeble current, it could have been used to electroplate dull metals with gold, or to electrify religious objects with an inspirational tingle-to-the-touch. On the other hand, they might just have been fancy scroll-storage devices designed to hold papyrus neatly in place. Either way, they're gadgets.

The components are hard to date, but the pottery style suggests second or third century construction.

__The Seamless Globe __ * c. 1630*

Armilliary spheres represent a model of the universe, comprising the equator, the ecliptic and the meridians. Early models place the Earth in the center—more modern ones replace it with the Sun.

The earliest known model was invented by Eratosthenes in 255BC, with Zhang Heng creating a water-powered example in the second century.

Complex and exceedingly detailed, these elaborate devices are held to be among mankind's earliest examples of precision engineering. Perhaps the greatest are the seamless but static perfect globes created for the Mughal Emperors, between the 16th-19th centuries.

__The Turk and El Ajedrecista __ 1770 and 1912

The Turk was a chess player concealed in a table packed with cogs and gears, contrived to give the appearance of a mighty chess-playing machine. Atop the table, an articulated automaton would be seen to make the moves determined by the master within.

One of the 18th and 19th century's many illustrious hoaxes, the Turk is perhaps the greatest gadget that wasn't. That said, it was a complex machine featuring a variety of technical marvels.

For example, the player had to operate the mechanical turk blindly, so that it could be seen to make the moves itself: a system of magnetic chess pieces, levers and pulleys made this possible. A primitive voice box allowed it to inform its victims that their King was in check. Skeptic Philip Thicknesse wrote the definitive early exposé, in which he describes The Turk as " a complicated piece of clockwork. " Knockoffs of the original became more common thereafter, with exotic names such as Ajeeb and Mephisto.

Reece Rogers

Louryn Strampe

Scott Gilbertson

Brenda Stolyar

El Ajedrecista was the first chess machine that could actually make its own moves. Unlike The Turk, it was a genuine automaton able to play endgames featuring a King vs. a King and a Rook. Created in 1912 by Leonardo Torres y Quevedo, it was a sensation: it could even detect illegal moves.

Governed by a simple algorithm, it would deliver mate every time regardless of the lone King's movements or the setup of the board.

__ Pot Still __ * c. 9th Century *

Now here's a technology we can drink to.

Formerly used by alchemists until it was more properly deployed in the distillation of whiskies and brandies, the alembic was invented around the eighth century and led directly to its modern derivative, the pot still.

An alembic assembly comprises two receptacles, or retorts, and a connecting tube to condense the boiling contents of one and shunt the result to the other. As the simplest way to to get that particular chemical process done, it's perfect for brewing moonshine.

__ Classical GPS: The Equitorium, Torquetum, Astrolabe, Sextant and Orrery __

The astrolabe was in use from before the age of Christ until the modern era. An analog computer able to predict and pinpoint the location of heavenly bodies, it was put to many uses: Astrologers and astronomers alike enjoyed its precision, and its reflection of the skies above made it useful for finding exactly where you were beneath them.

Medieval and renaissance life was packed with crazy astronomical gadgets. The sextant, a device that allows navigators to quickly measure the angle of the sun, was another essential gadget on the high seas. Simpler than the astrolabe, but less useful, was the equitorium. Able to pinpoint the relative positions of the Moon, Sun and planets without any calculation, mechanical or otherwise, it was first invented by Arzachel in the eleventh Century.

The Torquetum (above) is a more complex device, thought to have been invented about 800 years ago, but of which only relatively modern examples remain due to the design's fragility. Another device was the pantacosm, which calculates aspects, or the angles between heavenly bodies. The tellurion demonstrates how daylight and the seasons on Earth are caused by its bearing relative to the sun.

Of all such universal calculators, Orreries are among the most beautiful. Illustrating in miniature a three dimensional model of the solar system, they also model the movements of its constituent bodies. First constructed in about 1704 by clockmaker George Graham, it gave the public of a largely pre-scientific era a working insight into a universe they could barely comprehend.

The earliest capacitor, the Leyden Jar was invented in the 1740s by the University of Leiden's Pieter van Musschenbroe. In its simplest form, it is a metal conductor passing through an insulated stopper into a bottle of water lined inside and out with foil. Ground the outside and apply a charge to the inside, and the film gains an opposing charge held in place by the dielectric (i.e. the glass). Close the circuit between the two coatings, and ... *zap! *

__Ark of the Covenant __

Described in the Bible as a sacred box containing the stone-inscribed ten commandments and other relics, the Ark's odd characteristics have long intrigued scholars.

Often depicted as an ornate metal-lined chest with two cherubim facing one another atop it, the ark had four rings, containing two long wooden carrying poles. Some believe this odd composition suggests it was a primitive battery.

Perhaps the ark was a Leyden Jar of sorts, able to hold a charge and zap sticky-fingered thieves.

Finally lost when the Babylonians plundered Jerusalem,it was likely stolen and ultimately destroyed by the invaders. The faithful hope it found its way in hiding: the British Isles and Ethiopia are among popularly-proposed resting places.

__ The Mariner's Compass __ c. 1100

Until the second millenium, it was impossible for mariners on the open sea to accurately track latitude. The compass was invented in China in the 11th century and in common use worldwide by the end of the 13th century.

Containing a magnetized sliver of metal or rock, held so that it may point freely toward magnetic poles, a compass reveals the cardinal points with sufficient accuracy to aid travelers get from place to place without other indicators of bearing.

The result was an explosion in European maritime trade and the growth of merchant capitalism.

The Pocketwatch

Early timepieces used a variety of mechanisms to measure time: the shadow of a sundail, the tempo of a water clock's drip, the slow melt of a candle. Such devices can be extraordinarily complex, but it's the mechanical clock, with its intricate gearing and accuracy, that became one of mankind's greatest technical triumphs.

Descriptions in European literature from the late 13th century suggest that a new technology was proliferating: timepieces powered not by water, but instead by the movements of mechanically-connected weights.

It's with the pocketwatch, apparently invented in the 15th century, that we get the world's first modern-era personal tech toy. In November 1462, clockmaker Bartholomew Manfredi pitched a client on the idea of a "pocket clock" better than any seen before ; they were being manufactured within 50 years.

__ Special Guest Gadgets: Sampo and Liahona __

Mythical in character, the Sampo of Finnish mythology has a curiously technological vibe to it. Said to be a mysterious artefact whose possession brought the owner whatever they please, it's often depicted as a tiny gadget of historical character — a compass, for example, or a grinder. As the medieval era's fairies are to sci-fi's little gray aliens, Sampo is to Star Trek's replicators. I blame MST3K .

In the Book of Mormon, Liahona is a "curious" brass ball found one morning outside of the prophet Lehi's tent, indicating the way forward with a spindle and occasionally revealing further instructions from God. Destined to become the brand name for a range of GPS devices any time now, it's an article of faith for Latter-Day Saints.

So much got cut from this list: fans of Leonardo da Vinci and Charles Babbage will doubtless be particularly affronted. What other historical wonders could show an iPhone a thing or two about human ingenuity?

Benj Edwards, Ars Technica

Pete Cottell

Adrienne So

Eric Ravenscraft

Christopher Null

Lauren Goode

WIRED COUPONS

Extra 20% Off Select Dyson Technology With Owner Rewards

GoPro Promo Code: 15% Off Cameras & Accessories

Get Up To Extra 45% Off - May Secret Sale

5% Off Everything With Dell Coupon Code

Design tote bags starting under $2/piece

Newegg Coupon - 10% Off

The Rise of the Gadget and Hyperludic Me-Dia

William Merrin is an associate professor in media studies at Swansea University, in Wales, with research interests in media theory, digital media, and culture and media history. He is the author of Baudrillard and the Media (2005), coeditor of Jean Baudrillard: Fatal Theories (2008), and author of Media Studies 2.0 (forthcoming).

- Standard View

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

William Merrin; The Rise of the Gadget and Hyperludic Me-Dia. Cultural Politics 1 March 2014; 10 (1): 1–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/17432197-2397209

Download citation file:

- Reference Manager

Though digital “gadgets” have become one of the most important sectors of consumer electronics, the concept itself has been largely overlooked. This article traces the history of the gadget from its nineteenth-century origins as a placeholding name to its use for a class of technical objects, through to its incorporation of electronics and its contemporary success. Building upon Jean Baudrillard’s analysis, the article explores how digital technology has changed the gadget’s nature and capacities. It argues that the digital gadget’s success lies in its hyperfunctionality, hyperludic experience, and relationship with me-dia. It analyzes the digital gadget’s role in the reorientation of the broadcast ecology around personalized media worlds and experiences, arguing that its mode of play represents an integration of the life, activities, bodies, and attention of the individual that extends beyond that achieved by broadcast media

The machine was the emblem of industrial society. The gadget is the emblem of post-industrial society. —Jean Baudrillard, The Consumer Society

From the beginning the gadget has been surrounded by an air of uncertainty, a slipperiness in our understanding that has benefited it in its slow rise to prominence. Appropriately for an object whose boundaries and definition are vague and whose forms and functions are varied, even the origins of the word are unclear. The story that it was derived from Gaget, Gauthier and Cie’s name stamp on tourist copies of the Statue of Liberty, is now discredited, and sources suggest instead an etymological origin in the French gâchette , the “catch-piece of a mechanism” (a term applied, for example, to parts of a firing mechanism), or gagée , meaning a small tool or instrument. The Oxford English Dictionary claims anecdotal evidence for the term’s use by the 1850s as a word for an object whose name one cannot remember, a use consistent with its first print appearance in Robert Brown’s 1886 book Spunyarn and Spindrift, a Sailor Boy’s Log of a Voyage Out and Home in a China Tea-Clipper , which reports: “Then the names of all the other things on board a ship! I don’t know half of them yet; even the sailors forget at times, and if the exact name of anything they want happens to slip from their memory, they call it a chicken-fixing, or a gadjet, or a gill-guy, or a timmey-noggy, or a wim-wom—just pro-tem ., you know” (quoted in Quinion 2007 ).

Unlike “chicken-fixing,” “timmey-noggy,” or “wim-wom,” however, the “gadjet” was destined for greater things. By the early twentieth century it had changed from the frustrated expression of aphasia at an object’s recalcitrance to a category of objects in itself, and by the postwar period it had become a profitable element of technical and consumer culture, albeit one often overlooked and rarely taken seriously. Again, perhaps, this suited the gadget; associated with the domestic sphere and sold in novelty shops, department stores, and catalogs, gadgets quietly succeeded in colonizing everyday life, taking up residence in our kitchen cupboards and drawers and our sheds and garages. Their incorporation of electronics brought greater popularity, and toy boxes soon filled with beeping gizmos while plastic objects with blinking LEDs spilled out of drawers.

For all its success, this proliferation of the gadget proved to be only the preliminary phase of the gadget’s rise. Embracing its electronic potential it established a foothold in personal entertainment and communication, where with the convergence of mass media and computer processing at the end of the twentieth century it completed its passage from a functionally specialized, handy gimmick to become one of the most important categories of technical object and a major force in global consumer electronics. Breaking out of the drawers and toy boxes, this new, networked digital gadget—our tablets, netbooks, phones, music players, media players, e-readers, cameras, and portable gaming devices—became personal, mobile, and ubiquitous. Today the gadget has become the center of attention.

Despite its long history and contemporary success, few attempts have been made to trace its rise or theorize its form and effects. Indeed, something about the category itself eludes conceptualization and critique; ignored or dismissed for most of its life, at the moment of its greatest occupation of our lives it still avoids analysis and censure. One of the few discussions of the gadget appears in the work of Jean Baudrillard, who provides a prescient vision of its cybernetic future. In this article I want to extend this vision to explore the contemporary digital gadget. In particular, I want to argue that its success is related to its role in the development of what I call “me-dia” and to its personalized, hyperfunctional, and hyperludic nature that repeatedly calls us back and that constitutes a mode of physiological alienation and integration that is far greater than any achieved by the broadcast media. To understand this hyperludic gadget, however, we first need to understand something of the peculiar and unwritten history of these timmey-noggies, wimwoms, and thingamajigs.

- The “Anonymous History” of the Gadget, or How Humans Came to Dream of Magnetic Sleep

Although expressions of frustration at items whose name has momentarily escaped the user must always have occurred, there is nevertheless something significant about the origin of the word gadjet . Its anecdotal use by the 1850s, its etymological origins, and Brown’s exhausted declaration about the number of things aboard a modern ship suggest that the key issue was the increasing quantity and complexity of objects: problems intimately connected to the industrial society. Already in 1829, Thomas Carlyle could be found lamenting “the mechanical age,” that “age of machinery” in which “nothing is now done directly, or by hand; all is by rule and calculated contrivance. For the simplest operation, some helps and accompaniments, some cunning abbreviating process is in readiness. Our old modes of exertion are all discredited and thrown aside.” His examples are near hysteric; even the brood hen is replaced by chickens hatched by steam, he claims, while mechanical devices mince our cabbages and cast us “into magnetic sleep” ( Carlyle 2004 [1829] ).

The Industrial Revolution saw a significant and cumulative development in technical objects ( Headrick 2009 ). From the mid-eighteenth century on there was an increase in invention and its technical application, an increase in the quantity of technologies in use, a growing complexity of technologies, and an increasing penetration by them in the lives of ordinary people as technologies moved from marginal curiosities to the partner or director of people’s labor. Most accounts of the period emphasize the scale of the technologies. Although the textile mules, mills, and gins, the systems of powered wheels, belts, and shafts, and the steam engines all depended on a complex system of parts (that, by the late eighteenth century, had to be precision-made in machine shops), it was the whole assemblage— the machine —that became recognized as the key social and productive force of the industrial age. When engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel discussed the Great Eastern , the iron steamship that was the largest in the world on its launch in 1858, he referred to it repeatedly as “a machine”—as a single entity and whole ( Harvie, Martin, and Scharf 1970 : 48–51). Though early inventions had an air of novelty, it was large-scale “machinery” that came to dominate life, attention, and criticism.

By the early 1850s, machinery’s dominance was beginning to change. The effect of an advancing industrial and nascent consumer culture was a proliferation of technical objects—of commodities, things, tools, entertainments, and scientific and philosophical instruments—and it’s no coincidence that the word gadjet emerges at this time. At exactly the moment when social critics were attacking the subsumption of the human body beneath the weight of industrial technology as “an appendage of the machine” and one of its parts ( Marx and Engels 1987 [1848] : 87), nautical slang similarly arose to express the overwhelming of the human mind and its expressive faculty by the sheer multiplication of technical forms and functions. If industrial technology transformed the overwhelming of the body into an alienation of the mind, the proliferation of technical objects reversed the process, transforming the alienation of the mind—of the mental image of the thing—into an alienation of the body, of the capacity even to frame one’s own speech.

Perhaps the best evidence of this proliferation is found in that epochal celebration of the industrial object, “the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations.” Held in London in 1851, it contained over one hundred thousand objects from fourteen thousand exhibitors, forcing its organizing committee into a remarkable feat of classification. With the human census only a few decades old in the United Kingdom and with the 1841 census being the first to actually record the names of everyone in the household, the committee produced the first census of the industrial population—of those objects inhabiting the workshops, factories, studios, and shops of the nation—classifying the products of industry into a thirty-part taxonomy divided into four overall categories. It would take four large volumes of the official catalog to list them all, and contemporary visitors were bewildered by the number of things to see. One James Ward, for example, described his “state of mental helplessness” upon entering the exhibition (quoted in Auerbach 1999 : 95); there was too much for the mind to cope with.