- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 8. The Discussion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

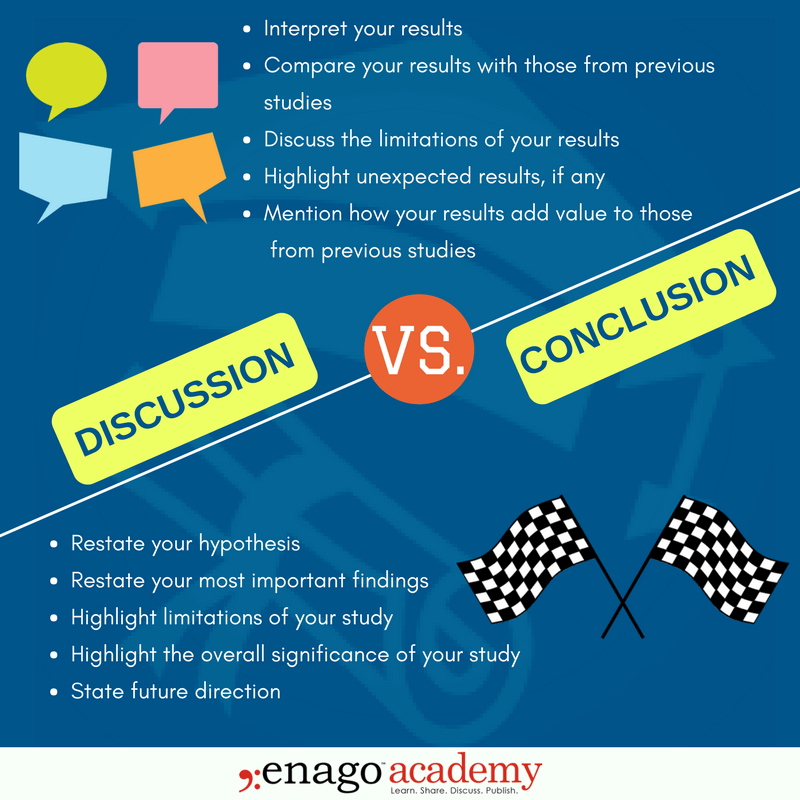

The purpose of the discussion section is to interpret and describe the significance of your findings in relation to what was already known about the research problem being investigated and to explain any new understanding or insights that emerged as a result of your research. The discussion will always connect to the introduction by way of the research questions or hypotheses you posed and the literature you reviewed, but the discussion does not simply repeat or rearrange the first parts of your paper; the discussion clearly explains how your study advanced the reader's understanding of the research problem from where you left them at the end of your review of prior research.

Annesley, Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Peacock, Matthew. “Communicative Moves in the Discussion Section of Research Articles.” System 30 (December 2002): 479-497.

Importance of a Good Discussion

The discussion section is often considered the most important part of your research paper because it:

- Most effectively demonstrates your ability as a researcher to think critically about an issue, to develop creative solutions to problems based upon a logical synthesis of the findings, and to formulate a deeper, more profound understanding of the research problem under investigation;

- Presents the underlying meaning of your research, notes possible implications in other areas of study, and explores possible improvements that can be made in order to further develop the concerns of your research;

- Highlights the importance of your study and how it can contribute to understanding the research problem within the field of study;

- Presents how the findings from your study revealed and helped fill gaps in the literature that had not been previously exposed or adequately described; and,

- Engages the reader in thinking critically about issues based on an evidence-based interpretation of findings; it is not governed strictly by objective reporting of information.

Annesley Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Bitchener, John and Helen Basturkmen. “Perceptions of the Difficulties of Postgraduate L2 Thesis Students Writing the Discussion Section.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5 (January 2006): 4-18; Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

These are the general rules you should adopt when composing your discussion of the results :

- Do not be verbose or repetitive; be concise and make your points clearly

- Avoid the use of jargon or undefined technical language

- Follow a logical stream of thought; in general, interpret and discuss the significance of your findings in the same sequence you described them in your results section [a notable exception is to begin by highlighting an unexpected result or a finding that can grab the reader's attention]

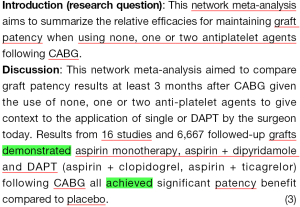

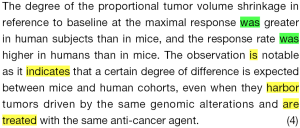

- Use the present verb tense, especially for established facts; however, refer to specific works or prior studies in the past tense

- If needed, use subheadings to help organize your discussion or to categorize your interpretations into themes

II. The Content

The content of the discussion section of your paper most often includes :

- Explanation of results : Comment on whether or not the results were expected for each set of findings; go into greater depth to explain findings that were unexpected or especially profound. If appropriate, note any unusual or unanticipated patterns or trends that emerged from your results and explain their meaning in relation to the research problem.

- References to previous research : Either compare your results with the findings from other studies or use the studies to support a claim. This can include re-visiting key sources already cited in your literature review section, or, save them to cite later in the discussion section if they are more important to compare with your results instead of being a part of the general literature review of prior research used to provide context and background information. Note that you can make this decision to highlight specific studies after you have begun writing the discussion section.

- Deduction : A claim for how the results can be applied more generally. For example, describing lessons learned, proposing recommendations that can help improve a situation, or highlighting best practices.

- Hypothesis : A more general claim or possible conclusion arising from the results [which may be proved or disproved in subsequent research]. This can be framed as new research questions that emerged as a consequence of your analysis.

III. Organization and Structure

Keep the following sequential points in mind as you organize and write the discussion section of your paper:

- Think of your discussion as an inverted pyramid. Organize the discussion from the general to the specific, linking your findings to the literature, then to theory, then to practice [if appropriate].

- Use the same key terms, narrative style, and verb tense [present] that you used when describing the research problem in your introduction.

- Begin by briefly re-stating the research problem you were investigating and answer all of the research questions underpinning the problem that you posed in the introduction.

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships shown by each major findings and place them in proper perspective. The sequence of this information is important; first state the answer, then the relevant results, then cite the work of others. If appropriate, refer the reader to a figure or table to help enhance the interpretation of the data [either within the text or as an appendix].

- Regardless of where it's mentioned, a good discussion section includes analysis of any unexpected findings. This part of the discussion should begin with a description of the unanticipated finding, followed by a brief interpretation as to why you believe it appeared and, if necessary, its possible significance in relation to the overall study. If more than one unexpected finding emerged during the study, describe each of them in the order they appeared as you gathered or analyzed the data. As noted, the exception to discussing findings in the same order you described them in the results section would be to begin by highlighting the implications of a particularly unexpected or significant finding that emerged from the study, followed by a discussion of the remaining findings.

- Before concluding the discussion, identify potential limitations and weaknesses if you do not plan to do so in the conclusion of the paper. Comment on their relative importance in relation to your overall interpretation of the results and, if necessary, note how they may affect the validity of your findings. Avoid using an apologetic tone; however, be honest and self-critical [e.g., in retrospect, had you included a particular question in a survey instrument, additional data could have been revealed].

- The discussion section should end with a concise summary of the principal implications of the findings regardless of their significance. Give a brief explanation about why you believe the findings and conclusions of your study are important and how they support broader knowledge or understanding of the research problem. This can be followed by any recommendations for further research. However, do not offer recommendations which could have been easily addressed within the study. This would demonstrate to the reader that you have inadequately examined and interpreted the data.

IV. Overall Objectives

The objectives of your discussion section should include the following: I. Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings

Briefly reiterate the research problem or problems you are investigating and the methods you used to investigate them, then move quickly to describe the major findings of the study. You should write a direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results, usually in one paragraph.

II. Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important

No one has thought as long and hard about your study as you have. Systematically explain the underlying meaning of your findings and state why you believe they are significant. After reading the discussion section, you want the reader to think critically about the results and why they are important. You don’t want to force the reader to go through the paper multiple times to figure out what it all means. If applicable, begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most significant or unanticipated finding first, then systematically review each finding. Otherwise, follow the general order you reported the findings presented in the results section.

III. Relate the Findings to Similar Studies

No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for your research. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps to support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your study differs from other research about the topic. Note that any significant or unanticipated finding is often because there was no prior research to indicate the finding could occur. If there is prior research to indicate this, you need to explain why it was significant or unanticipated. IV. Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings

It is important to remember that the purpose of research in the social sciences is to discover and not to prove . When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. This is especially important when describing the discovery of significant or unanticipated findings.

V. Acknowledge the Study’s Limitations

It is far better for you to identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor! Note any unanswered questions or issues your study could not address and describe the generalizability of your results to other situations. If a limitation is applicable to the method chosen to gather information, then describe in detail the problems you encountered and why. VI. Make Suggestions for Further Research

You may choose to conclude the discussion section by making suggestions for further research [as opposed to offering suggestions in the conclusion of your paper]. Although your study can offer important insights about the research problem, this is where you can address other questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or highlight hidden issues that were revealed as a result of conducting your research. You should frame your suggestions by linking the need for further research to the limitations of your study [e.g., in future studies, the survey instrument should include more questions that ask..."] or linking to critical issues revealed from the data that were not considered initially in your research.

NOTE: Besides the literature review section, the preponderance of references to sources is usually found in the discussion section . A few historical references may be helpful for perspective, but most of the references should be relatively recent and included to aid in the interpretation of your results, to support the significance of a finding, and/or to place a finding within a particular context. If a study that you cited does not support your findings, don't ignore it--clearly explain why your research findings differ from theirs.

V. Problems to Avoid

- Do not waste time restating your results . Should you need to remind the reader of a finding to be discussed, use "bridge sentences" that relate the result to the interpretation. An example would be: “In the case of determining available housing to single women with children in rural areas of Texas, the findings suggest that access to good schools is important...," then move on to further explaining this finding and its implications.

- As noted, recommendations for further research can be included in either the discussion or conclusion of your paper, but do not repeat your recommendations in the both sections. Think about the overall narrative flow of your paper to determine where best to locate this information. However, if your findings raise a lot of new questions or issues, consider including suggestions for further research in the discussion section.

- Do not introduce new results in the discussion section. Be wary of mistaking the reiteration of a specific finding for an interpretation because it may confuse the reader. The description of findings [results section] and the interpretation of their significance [discussion section] should be distinct parts of your paper. If you choose to combine the results section and the discussion section into a single narrative, you must be clear in how you report the information discovered and your own interpretation of each finding. This approach is not recommended if you lack experience writing college-level research papers.

- Use of the first person pronoun is generally acceptable. Using first person singular pronouns can help emphasize a point or illustrate a contrasting finding. However, keep in mind that too much use of the first person can actually distract the reader from the main points [i.e., I know you're telling me this--just tell me!].

Analyzing vs. Summarizing. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Discussion. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Hess, Dean R. "How to Write an Effective Discussion." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004); Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sauaia, A. et al. "The Anatomy of an Article: The Discussion Section: "How Does the Article I Read Today Change What I Will Recommend to my Patients Tomorrow?” The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 74 (June 2013): 1599-1602; Research Limitations & Future Research . Lund Research Ltd., 2012; Summary: Using it Wisely. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Discussion. Writing in Psychology course syllabus. University of Florida; Yellin, Linda L. A Sociology Writer's Guide . Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2009.

Writing Tip

Don’t Over-Interpret the Results!

Interpretation is a subjective exercise. As such, you should always approach the selection and interpretation of your findings introspectively and to think critically about the possibility of judgmental biases unintentionally entering into discussions about the significance of your work. With this in mind, be careful that you do not read more into the findings than can be supported by the evidence you have gathered. Remember that the data are the data: nothing more, nothing less.

MacCoun, Robert J. "Biases in the Interpretation and Use of Research Results." Annual Review of Psychology 49 (February 1998): 259-287; Ward, Paulet al, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Expertise . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Write Two Results Sections!

One of the most common mistakes that you can make when discussing the results of your study is to present a superficial interpretation of the findings that more or less re-states the results section of your paper. Obviously, you must refer to your results when discussing them, but focus on the interpretation of those results and their significance in relation to the research problem, not the data itself.

Azar, Beth. "Discussing Your Findings." American Psychological Association gradPSYCH Magazine (January 2006).

Yet Another Writing Tip

Avoid Unwarranted Speculation!

The discussion section should remain focused on the findings of your study. For example, if the purpose of your research was to measure the impact of foreign aid on increasing access to education among disadvantaged children in Bangladesh, it would not be appropriate to speculate about how your findings might apply to populations in other countries without drawing from existing studies to support your claim or if analysis of other countries was not a part of your original research design. If you feel compelled to speculate, do so in the form of describing possible implications or explaining possible impacts. Be certain that you clearly identify your comments as speculation or as a suggestion for where further research is needed. Sometimes your professor will encourage you to expand your discussion of the results in this way, while others don’t care what your opinion is beyond your effort to interpret the data in relation to the research problem.

- << Previous: Using Non-Textual Elements

- Next: Limitations of the Study >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 11:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

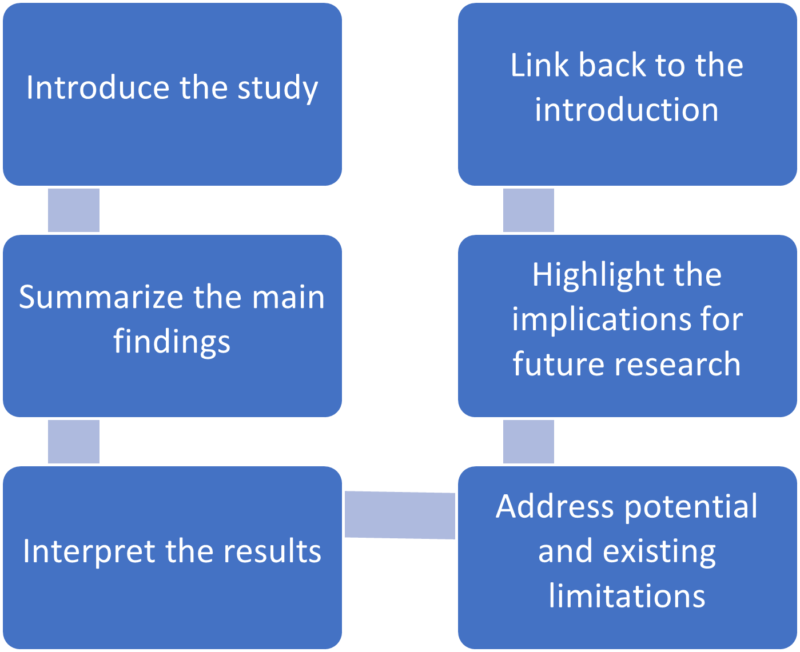

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- Manuscript Preparation

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

- 4 minute read

Table of Contents

The discussion section in scientific manuscripts might be the last few paragraphs, but its role goes far beyond wrapping up. It’s the part of an article where scientists talk about what they found and what it means, where raw data turns into meaningful insights. Therefore, discussion is a vital component of the article.

An excellent discussion is well-organized. We bring to you authors a classic 6-step method for writing discussion sections, with examples to illustrate the functions and specific writing logic of each step. Take a look at how you can impress journal reviewers with a concise and focused discussion section!

Discussion frame structure

Conventionally, a discussion section has three parts: an introductory paragraph, a few intermediate paragraphs, and a conclusion¹. Please follow the steps below:

1.Introduction—mention gaps in previous research¹⁻ ²

Here, you orient the reader to your study. In the first paragraph, it is advisable to mention the research gap your paper addresses.

Example: This study investigated the cognitive effects of a meat-only diet on adults. While earlier studies have explored the impact of a carnivorous diet on physical attributes and agility, they have not explicitly addressed its influence on cognitively intense tasks involving memory and reasoning.

2. Summarizing key findings—let your data speak ¹⁻ ²

After you have laid out the context for your study, recapitulate some of its key findings. Also, highlight key data and evidence supporting these findings.

Example: We found that risk-taking behavior among teenagers correlates with their tendency to invest in cryptocurrencies. Risk takers in this study, as measured by the Cambridge Gambling Task, tended to have an inordinately higher proportion of their savings invested as crypto coins.

3. Interpreting results—compare with other papers¹⁻²

Here, you must analyze and interpret any results concerning the research question or hypothesis. How do the key findings of your study help verify or disprove the hypothesis? What practical relevance does your discovery have?

Example: Our study suggests that higher daily caffeine intake is not associated with poor performance in major sporting events. Athletes may benefit from the cardiovascular benefits of daily caffeine intake without adversely impacting performance.

Remember, unlike the results section, the discussion ideally focuses on locating your findings in the larger body of existing research. Hence, compare your results with those of other peer-reviewed papers.

Example: Although Miller et al. (2020) found evidence of such political bias in a multicultural population, our findings suggest that the bias is weak or virtually non-existent among politically active citizens.

4. Addressing limitations—their potential impact on the results¹⁻²

Discuss the potential impact of limitations on the results. Most studies have limitations, and it is crucial to acknowledge them in the intermediary paragraphs of the discussion section. Limitations may include low sample size, suspected interference or noise in data, low effect size, etc.

Example: This study explored a comprehensive list of adverse effects associated with the novel drug ‘X’. However, long-term studies may be needed to confirm its safety, especially regarding major cardiac events.

5. Implications for future research—how to explore further¹⁻²

Locate areas of your research where more investigation is needed. Concluding paragraphs of the discussion can explain what research will likely confirm your results or identify knowledge gaps your study left unaddressed.

Example: Our study demonstrates that roads paved with the plastic-infused compound ‘Y’ are more resilient than asphalt. Future studies may explore economically feasible ways of producing compound Y in bulk.

6. Conclusion—summarize content¹⁻²

A good way to wind up the discussion section is by revisiting the research question mentioned in your introduction. Sign off by expressing the main findings of your study.

Example: Recent observations suggest that the fish ‘Z’ is moving upriver in many parts of the Amazon basin. Our findings provide conclusive evidence that this phenomenon is associated with rising sea levels and climate change, not due to elevated numbers of invasive predators.

A rigorous and concise discussion section is one of the keys to achieving an excellent paper. It serves as a critical platform for researchers to interpret and connect their findings with the broader scientific context. By detailing the results, carefully comparing them with existing research, and explaining the limitations of this study, you can effectively help reviewers and readers understand the entire research article more comprehensively and deeply¹⁻² , thereby helping your manuscript to be successfully published and gain wider dissemination.

In addition to keeping this writing guide, you can also use Elsevier Language Services to improve the quality of your paper more deeply and comprehensively. We have a professional editing team covering multiple disciplines. With our profound disciplinary background and rich polishing experience, we can significantly optimize all paper modules including the discussion, effectively improve the fluency and rigor of your articles, and make your scientific research results consistent, with its value reflected more clearly. We are always committed to ensuring the quality of papers according to the standards of top journals, improving the publishing efficiency of scientific researchers, and helping you on the road to academic success. Check us out here !

Type in wordcount for Standard Total: USD EUR JPY Follow this link if your manuscript is longer than 12,000 words. Upload

References:

- Masic, I. (2018). How to write an efficient discussion? Medical Archives , 72(3), 306. https://doi.org/10.5455/medarh.2018.72.306-307

- Şanlı, Ö., Erdem, S., & Tefik, T. (2014). How to write a discussion section? Urology Research & Practice , 39(1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.5152/tud.2013.049

- Manuscript Review

Navigating “Chinglish” Errors in Academic English Writing

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Path to An Impactful Paper: Common Manuscript Writing Patterns and Structure

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

How to Write the Discussion Section of a Research Paper

The discussion section of a research paper analyzes and interprets the findings, provides context, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future research directions.

Updated on September 15, 2023

Structure your discussion section right, and you’ll be cited more often while doing a greater service to the scientific community. So, what actually goes into the discussion section? And how do you write it?

The discussion section of your research paper is where you let the reader know how your study is positioned in the literature, what to take away from your paper, and how your work helps them. It can also include your conclusions and suggestions for future studies.

First, we’ll define all the parts of your discussion paper, and then look into how to write a strong, effective discussion section for your paper or manuscript.

Discussion section: what is it, what it does

The discussion section comes later in your paper, following the introduction, methods, and results. The discussion sets up your study’s conclusions. Its main goals are to present, interpret, and provide a context for your results.

What is it?

The discussion section provides an analysis and interpretation of the findings, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future directions for research.

This section combines information from the preceding parts of your paper into a coherent story. By this point, the reader already knows why you did your study (introduction), how you did it (methods), and what happened (results). In the discussion, you’ll help the reader connect the ideas from these sections.

Why is it necessary?

The discussion provides context and interpretations for the results. It also answers the questions posed in the introduction. While the results section describes your findings, the discussion explains what they say. This is also where you can describe the impact or implications of your research.

Adds context for your results

Most research studies aim to answer a question, replicate a finding, or address limitations in the literature. These goals are first described in the introduction. However, in the discussion section, the author can refer back to them to explain how the study's objective was achieved.

Shows what your results actually mean and real-world implications

The discussion can also describe the effect of your findings on research or practice. How are your results significant for readers, other researchers, or policymakers?

What to include in your discussion (in the correct order)

A complete and effective discussion section should at least touch on the points described below.

Summary of key findings

The discussion should begin with a brief factual summary of the results. Concisely overview the main results you obtained.

Begin with key findings with supporting evidence

Your results section described a list of findings, but what message do they send when you look at them all together?

Your findings were detailed in the results section, so there’s no need to repeat them here, but do provide at least a few highlights. This will help refresh the reader’s memory and help them focus on the big picture.

Read the first paragraph of the discussion section in this article (PDF) for an example of how to start this part of your paper. Notice how the authors break down their results and follow each description sentence with an explanation of why each finding is relevant.

State clearly and concisely

Following a clear and direct writing style is especially important in the discussion section. After all, this is where you will make some of the most impactful points in your paper. While the results section often contains technical vocabulary, such as statistical terms, the discussion section lets you describe your findings more clearly.

Interpretation of results

Once you’ve given your reader an overview of your results, you need to interpret those results. In other words, what do your results mean? Discuss the findings’ implications and significance in relation to your research question or hypothesis.

Analyze and interpret your findings

Look into your findings and explore what’s behind them or what may have caused them. If your introduction cited theories or studies that could explain your findings, use these sources as a basis to discuss your results.

For example, look at the second paragraph in the discussion section of this article on waggling honey bees. Here, the authors explore their results based on information from the literature.

Unexpected or contradictory results

Sometimes, your findings are not what you expect. Here’s where you describe this and try to find a reason for it. Could it be because of the method you used? Does it have something to do with the variables analyzed? Comparing your methods with those of other similar studies can help with this task.

Context and comparison with previous work

Refer to related studies to place your research in a larger context and the literature. Compare and contrast your findings with existing literature, highlighting similarities, differences, and/or contradictions.

How your work compares or contrasts with previous work

Studies with similar findings to yours can be cited to show the strength of your findings. Information from these studies can also be used to help explain your results. Differences between your findings and others in the literature can also be discussed here.

How to divide this section into subsections

If you have more than one objective in your study or many key findings, you can dedicate a separate section to each of these. Here’s an example of this approach. You can see that the discussion section is divided into topics and even has a separate heading for each of them.

Limitations

Many journals require you to include the limitations of your study in the discussion. Even if they don’t, there are good reasons to mention these in your paper.

Why limitations don’t have a negative connotation

A study’s limitations are points to be improved upon in future research. While some of these may be flaws in your method, many may be due to factors you couldn’t predict.

Examples include time constraints or small sample sizes. Pointing this out will help future researchers avoid or address these issues. This part of the discussion can also include any attempts you have made to reduce the impact of these limitations, as in this study .

How limitations add to a researcher's credibility

Pointing out the limitations of your study demonstrates transparency. It also shows that you know your methods well and can conduct a critical assessment of them.

Implications and significance

The final paragraph of the discussion section should contain the take-home messages for your study. It can also cite the “strong points” of your study, to contrast with the limitations section.

Restate your hypothesis

Remind the reader what your hypothesis was before you conducted the study.

How was it proven or disproven?

Identify your main findings and describe how they relate to your hypothesis.

How your results contribute to the literature

Were you able to answer your research question? Or address a gap in the literature?

Future implications of your research

Describe the impact that your results may have on the topic of study. Your results may show, for instance, that there are still limitations in the literature for future studies to address. There may be a need for studies that extend your findings in a specific way. You also may need additional research to corroborate your findings.

Sample discussion section

This fictitious example covers all the aspects discussed above. Your actual discussion section will probably be much longer, but you can read this to get an idea of everything your discussion should cover.

Our results showed that the presence of cats in a household is associated with higher levels of perceived happiness by its human occupants. These findings support our hypothesis and demonstrate the association between pet ownership and well-being.

The present findings align with those of Bao and Schreer (2016) and Hardie et al. (2023), who observed greater life satisfaction in pet owners relative to non-owners. Although the present study did not directly evaluate life satisfaction, this factor may explain the association between happiness and cat ownership observed in our sample.

Our findings must be interpreted in light of some limitations, such as the focus on cat ownership only rather than pets as a whole. This may limit the generalizability of our results.

Nevertheless, this study had several strengths. These include its strict exclusion criteria and use of a standardized assessment instrument to investigate the relationships between pets and owners. These attributes bolster the accuracy of our results and reduce the influence of confounding factors, increasing the strength of our conclusions. Future studies may examine the factors that mediate the association between pet ownership and happiness to better comprehend this phenomenon.

This brief discussion begins with a quick summary of the results and hypothesis. The next paragraph cites previous research and compares its findings to those of this study. Information from previous studies is also used to help interpret the findings. After discussing the results of the study, some limitations are pointed out. The paper also explains why these limitations may influence the interpretation of results. Then, final conclusions are drawn based on the study, and directions for future research are suggested.

How to make your discussion flow naturally

If you find writing in scientific English challenging, the discussion and conclusions are often the hardest parts of the paper to write. That’s because you’re not just listing up studies, methods, and outcomes. You’re actually expressing your thoughts and interpretations in words.

- How formal should it be?

- What words should you use, or not use?

- How do you meet strict word limits, or make it longer and more informative?

Always give it your best, but sometimes a helping hand can, well, help. Getting a professional edit can help clarify your work’s importance while improving the English used to explain it. When readers know the value of your work, they’ll cite it. We’ll assign your study to an expert editor knowledgeable in your area of research. Their work will clarify your discussion, helping it to tell your story. Find out more about AJE Editing.

Adam Goulston, PsyD, MS, MBA, MISD, ELS

Science Marketing Consultant

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

Organizing Academic Research Papers: 8. The Discussion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

The purpose of the discussion is to interpret and describe the significance of your findings in light of what was already known about the research problem being investigated, and to explain any new understanding or fresh insights about the problem after you've taken the findings into consideration. The discussion will always connect to the introduction by way of the research questions or hypotheses you posed and the literature you reviewed, but it does not simply repeat or rearrange the introduction; the discussion should always explain how your study has moved the reader's understanding of the research problem forward from where you left them at the end of the introduction.

Importance of a Good Discussion

This section is often considered the most important part of a research paper because it most effectively demonstrates your ability as a researcher to think critically about an issue, to develop creative solutions to problems based on the findings, and to formulate a deeper, more profound understanding of the research problem you are studying.

The discussion section is where you explore the underlying meaning of your research , its possible implications in other areas of study, and the possible improvements that can be made in order to further develop the concerns of your research.

This is the section where you need to present the importance of your study and how it may be able to contribute to and/or fill existing gaps in the field. If appropriate, the discussion section is also where you state how the findings from your study revealed new gaps in the literature that had not been previously exposed or adequately described.

This part of the paper is not strictly governed by objective reporting of information but, rather, it is where you can engage in creative thinking about issues through evidence-based interpretation of findings. This is where you infuse your results with meaning.

Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section . San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

These are the general rules you should adopt when composing your discussion of the results :

- Do not be verbose or repetitive.

- Be concise and make your points clearly.

- Avoid using jargon.

- Follow a logical stream of thought.

- Use the present verb tense, especially for established facts; however, refer to specific works and references in the past tense.

- If needed, use subheadings to help organize your presentation or to group your interpretations into themes.

II. The Content

The content of the discussion section of your paper most often includes :

- Explanation of results : comment on whether or not the results were expected and present explanations for the results; go into greater depth when explaining findings that were unexpected or especially profound. If appropriate, note any unusual or unanticipated patterns or trends that emerged from your results and explain their meaning.

- References to previous research : compare your results with the findings from other studies, or use the studies to support a claim. This can include re-visiting key sources already cited in your literature review section, or, save them to cite later in the discussion section if they are more important to compare with your results than being part of the general research you cited to provide context and background information.

- Deduction : a claim for how the results can be applied more generally. For example, describing lessons learned, proposing recommendations that can help improve a situation, or recommending best practices.

- Hypothesis : a more general claim or possible conclusion arising from the results [which may be proved or disproved in subsequent research].

III. Organization and Structure

Keep the following sequential points in mind as you organize and write the discussion section of your paper:

- Think of your discussion as an inverted pyramid. Organize the discussion from the general to the specific, linking your findings to the literature, then to theory, then to practice [if appropriate].

- Use the same key terms, mode of narration, and verb tense [present] that you used when when describing the research problem in the introduction.

- Begin by briefly re-stating the research problem you were investigating and answer all of the research questions underpinning the problem that you posed in the introduction.

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships shown by each major findings and place them in proper perspective. The sequencing of providing this information is important; first state the answer, then the relevant results, then cite the work of others. If appropriate, refer the reader to a figure or table to help enhance the interpretation of the data. The order of interpreting each major finding should be in the same order as they were described in your results section.

- A good discussion section includes analysis of any unexpected findings. This paragraph should begin with a description of the unexpected finding, followed by a brief interpretation as to why you believe it appeared and, if necessary, its possible significance in relation to the overall study. If more than one unexpected finding emerged during the study, describe each them in the order they appeared as you gathered the data.

- Before concluding the discussion, identify potential limitations and weaknesses. Comment on their relative importance in relation to your overall interpretation of the results and, if necessary, note how they may affect the validity of the findings. Avoid using an apologetic tone; however, be honest and self-critical.

- The discussion section should end with a concise summary of the principal implications of the findings regardless of statistical significance. Give a brief explanation about why you believe the findings and conclusions of your study are important and how they support broader knowledge or understanding of the research problem. This can be followed by any recommendations for further research. However, do not offer recommendations which could have been easily addressed within the study. This demonstrates to the reader you have inadequately examined and interpreted the data.

IV. Overall Objectives

The objectives of your discussion section should include the following: I. Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings

Briefly reiterate for your readers the research problem or problems you are investigating and the methods you used to investigate them, then move quickly to describe the major findings of the study. You should write a direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results.

II. Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important

No one has thought as long and hard about your study as you have. Systematically explain the meaning of the findings and why you believe they are important. After reading the discussion section, you want the reader to think about the results [“why hadn’t I thought of that?”]. You don’t want to force the reader to go through the paper multiple times to figure out what it all means. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important finding first.

III. Relate the Findings to Similar Studies

No study is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to other previously published research. The discussion section should relate your study findings to those of other studies, particularly if questions raised by previous studies served as the motivation for your study, the findings of other studies support your findings [which strengthens the importance of your study results], and/or they point out how your study differs from other similar studies. IV. Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings

It is important to remember that the purpose of research is to discover and not to prove . When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the study results, rather than just those that fit your prior assumptions or biases.

V. Acknowledge the Study’s Limitations

It is far better for you to identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor! Describe the generalizability of your results to other situations, if applicable to the method chosen, then describe in detail problems you encountered in the method(s) you used to gather information. Note any unanswered questions or issues your study did not address, and.... VI. Make Suggestions for Further Research

Although your study may offer important insights about the research problem, other questions related to the problem likely remain unanswered. Moreover, some unanswered questions may have become more focused because of your study. You should make suggestions for further research in the discussion section.

NOTE: Besides the literature review section, the preponderance of references to sources in your research paper are usually found in the discussion section . A few historical references may be helpful for perspective but most of the references should be relatively recent and included to aid in the interpretation of your results and/or linked to similar studies. If a study that you cited disagrees with your findings, don't ignore it--clearly explain why the study's findings differ from yours.

V. Problems to Avoid

- Do not waste entire sentences restating your results . Should you need to remind the reader of the finding to be discussed, use "bridge sentences" that relate the result to the interpretation. An example would be: “The lack of available housing to single women with children in rural areas of Texas suggests that...[then move to the interpretation of this finding].”

- Recommendations for further research can be included in either the discussion or conclusion of your paper but do not repeat your recommendations in the both sections.

- Do not introduce new results in the discussion. Be wary of mistaking the reiteration of a specific finding for an interpretation.

- Use of the first person is acceptable, but too much use of the first person may actually distract the reader from the main points.

Analyzing vs. Summarizing. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Discussion . The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Hess, Dean R. How to Write an Effective Discussion. Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004); Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section . San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; The Lab Report . University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Summary: Using it Wisely . The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Discussion . Writing in Psychology course syllabus. University of Florida; Yellin, Linda L. A Sociology Writer's Guide. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2009.

Writing Tip

Don’t Overinterpret the Results!

Interpretation is a subjective exercise. Therefore, be careful that you do not read more into the findings than can be supported by the evidence you've gathered. Remember that the data are the data: nothing more, nothing less.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Write Two Results Sections!

One of the most common mistakes that you can make when discussing the results of your study is to present a superficial interpretation of the findings that more or less re-states the results section of your paper. Obviously, you must refer to your results when discussing them, but focus on the interpretion of those results, not just the data itself.

Azar, Beth. Discussing Your Findings. American Psychological Association gradPSYCH Magazine (January 2006)

Yet Another Writing Tip

Avoid Unwarranted Speculation!

The discussion section should remain focused on the findings of your study. For example, if you studied the impact of foreign aid on increasing levels of education among the poor in Bangladesh, it's generally not appropriate to speculate about how your findings might apply to populations in other countries without drawing from existing studies to support your claim. If you feel compelled to speculate, be certain that you clearly identify your comments as speculation or as a suggestion for where further research is needed. Sometimes your professor will encourage you to expand the discussion in this way, while others don’t care what your opinion is beyond your efforts to interpret the data.

- << Previous: Using Non-Textual Elements

- Next: Limitations of the Study >>

- Last Updated: Jul 18, 2023 11:58 AM

- URL: https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803

- QuickSearch

- Library Catalog

- Databases A-Z

- Publication Finder

- Course Reserves

- Citation Linker

- Digital Commons

- Our Website

Research Support

- Ask a Librarian

- Appointments

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Research Guides

- Databases by Subject

- Citation Help

Using the Library

- Reserve a Group Study Room

- Renew Books

- Honors Study Rooms

- Off-Campus Access

- Library Policies

- Library Technology

User Information

- Grad Students

- Online Students

- COVID-19 Updates

- Staff Directory

- News & Announcements

- Library Newsletter

My Accounts

- Interlibrary Loan

- Staff Site Login

FIND US ON

Page Contents

- 1.1 Research Answer

- 1.2 Key Findings

- 1.3 Interpretations

- 1.4 Comparison to Other Studies

- 1.5 Acknowledgement of Limitations

- 1.6 Recommendations for Future Research

- 2 Six Key Components of the Discussion Section – An Example

- 3 Questions to Help You Interpret Your Results

- 4 Reflective Exercise – Interpreting Your Results

- 5 Common Structure of the Discussion Section

- 6.1 Tip 1 – Include Specific Limitations

- 6.2 Tip 2 – Conclude with Your Contributions

- 6.3 Tip 3 – Use Signal Phrases

- 6.4 Tip 4 – Choose Verbs Carefully

- 8 Conclusion

Writing the Discussion

The Discussion section is widely recognized as the most challenging part of the research article to write. But it’s also the most rewarding section in many ways because it’s where you get to say what your findings mean and why they matter. It’s where you get to talk about your own contributions to the research. Before you start writing your discussion, think critically about your data so that you can share your research story with your reader.

The Discussion section of a research article answers,

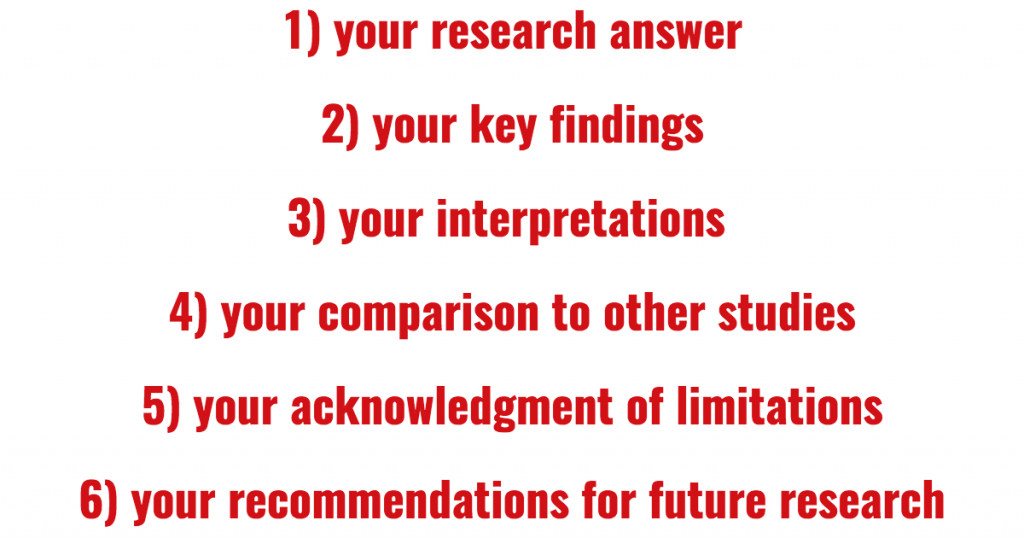

The six main components of the discussion section that will help you answer these questions for your reader are

The following list provides a brief overview of each of these components. The Common Structure of the Discussion section provides more details about how these components are integrated and developed within the paragraphs of the Discussion.

Research Answer

Start your Discussion by explicitly answering your research question. If you had a hypothesis, indicate whether or not it was supported. In some cases, you may wish to remind your reader of the research question before providing your research answer.

Key Findings

Provide an overview of your major findings before offering your specific interpretations and comparisons to other studies.

Interpretations

Explain what your results mean and make any claims based on your results. Ensure that you ground all your claims in evidence

Comparison to Other Studies

Compare your findings to those of other studies. Within the Discussion, interpretations and comparisons to other studies are often integrated. As you interpret your findings, you’ll indicate how they compare to existing research, and what the similarities or differences suggest. You’ll repeat this pattern as you move through your findings.

Acknowledgement of Limitations

Highlight the specific limitations of your study to demonstrate your awareness of potential gaps, acknowledge methodological drawbacks, and anticipate potential questions or criticism.

Recommendations for Future Research

Indicate what future researchers can do to build upon your research findings and take the research further.

Six Key Components of the Discussion Section – An Example

This video illustrates the six key components of the discussion section in a scientific research article by examining excerpts from a fictional research article about varroa mites in honeybee colonies.

NOTE: For educational purposes, we’ve created fictional excerpts that resemble passages from scientific research articles. The fictional examples are intended to illustrate writing techniques and are not designed to teach scientific content. Please note that the scientific content and data in this video is fictional.

[Background sounds of bees buzzing and birds chirping]

To illustrate the six key components of the discussion section, we’ll examine excerpts from a fictional scientific research article about varroa mites in honeybee colonies.

The writer starts their discussion with an ANSWER to their RESEARCH QUESTION by noting which two natural chemical treatments are effective. [A laptop displays the following voiceover text on screen.] They state, “Our findings indicate that formic acid strips and oxalic acid trickling are effective natural chemical treatments for reducing the presence of varroa mites in honeybee colonies.”

Next, the writer provides a summary of their KEY FINDINGS by focusing on which of the two treatments are most effective: [A laptop displays the following voiceover text on screen.] “Formic acid treatment was the most effective treatment for reducing the presence of varroa mites in honeybee colonies. This finding suggests that this treatment is an effective option for Ontario beekeepers.”

After providing the key findings, the writer begins to INTERPRET their INDIVIDUAL FINDINGS. The writer provides explanations for the similarities and differences that they observe. [A laptop displays the following voiceover text on screen.] For example, they note that, “Although oxalic acid is stronger than formic acid, formic acid strips were 14% more effective than oxalic acid trickling in reducing varroa mite populations. One reason for this observed difference may be that formic acid can penetrate the wax of the brood chamber whereas oxalic acid cannot.”

The writer also COMPARES their findings to OTHER STUDIES. They state, “Our findings with respect to natural chemical treatments are similar to those of Buzz et al. (2021). Buzz et al. (2021) compared the efficacy of sucrocide spray treatment to formic acid treatment and found that formic acid treatment was more effective for reducing mite populations. These similarities suggest that formic acid treatments are an effective option that beekeepers can use to protect their colonies.”

Note here that the writer moves beyond stating that their research is similar to that of others. [Laptop screen showing the text “These similarities suggest that formic acid treatments are an effective option that beekeepers can use to protect their colonies.”] They also indicate what these similarities suggest about the results.

In addition to highlighting what they found, the writer also ACKNOWLEDGES their LIMITATIONS. [A laptop displays the following voiceover text on screen.] They note, “As our study took place during a single season, we did not have the opportunity to determine how temperature impacts treatment efficacy.”

[Text on screen “SUGGEST FUTURE RESEARCH.] The writer concludes by indicating how this research can be addressed by future researchers, noting, “Further research is needed to determine how seasonal temperature impacts the efficacy of treatment types.”

Questions to Help You Interpret Your Results

Every claim that you make in your Discussion section must be grounded in evidence. Ensure that you understand your results thoroughly and present them effectively. These are some questions that you can ask yourself to determine what your findings mean and what you plan to write about them:

Examine the results from your study and consider how they relate to your research question or your hypotheses if you’re doing hypothesis-driven research. Which results did you expect? Which results did you not expect?

Think about how your results compare to the literature that you explored for your introduction, research proposal, or literature reviews. How do your results compare to existing studies? What are the similarities? What are the differences?

Although indicating how your research is similar to or different from existing research is important, you need to move beyond these statements to provide your own interpretations as well. Consider what these similarities and differences suggest. What do similarities between your results and those of other researchers mean? What might be some reasons for any differences that you’ve observed? Are there any interesting implications to note?

These questions will help you approach your data with a critical eye and map out the possible interpretations. Consider the following advice from Joshua Schimel’s Writing Science: How to Write Papers That Get Cited and Proposals That Get Funded (2012).

“What might that shoulder on the spectrum mean? If that nonsignificant treatment effect were real, what would that say about your system? Is that outlier a flag for something you hadn’t thought about but may be important? Overinterpret your data wildly, and consider what they might mean at those farthest fringes. Explore the possibilities and develop the story expansively. Then, take Occam’s razor and slash away to find the simple core” (Schimel 2012, p. 12).

As Schimel emphasizes in this passage, interpreting your data critically is key to telling the story of your research findings. A starting place is to consider all the possibilities for what your research could mean to ensure that you don’t miss possible interpretations. Once you’ve completed this exercise, consider the principle of Occam’s razor – the idea that the simplest explanation is usually the best one – to ensure that you’re not over interpreting your data. Once you start writing, focus your Discussion on the interpretations that you can provide specific evidence to support.

Reflective Exercise – Interpreting Your Results

The following “Interpreting Your Results – Worksheet” is a tool designed to guide your critical reflection and writing process. Use the table on this worksheet to help you interpret your results and discuss your research findings.

NOTE: You can view this worksheet online, but you can also download it below as an accessible screen reader document.

Download PDF (Interpreting Your Results – Worksheet)

This table is divided into four columns:

- Column One: Describe a result from your study.

- Column Two: Explain what your result indicates in a direct way. In other words, what would experts who look at this result logically conclude from it?

- Column Three: Consider what claims you could make about the result. In other words, what are your specific thoughts and interpretations about what the data could mean?

- Column Four: Note any questions that you still have about your result. These could be questions that you could answer by revisiting the literature in your field, or they could be questions that future researchers should consider.

Common Structure of the Discussion Section

In the Discussion section, writers typically move from a specific statement of research findings to the broad implications of the work. This movement is the opposite trajectory of what you typically see in an Introduction section, where the image of a funnel often represents how the writer will move from the broad area of research to the narrow, specific research question. The opposite image – that of a pyramid – is useful for the Discussion section. However, a Discussion section is not simply a backwards Introduction. In the Discussion, writers start with the answer to their specific research question and then move outward to discuss the broad implications of their work.

The following structure is a common one that you will find in the Discussion section of many research articles in the sciences.

Opening Paragraph: Provide your research answer and state your key findings.

Body Paragraphs: Offer your interpretations and comparisons to other studies. Carefully consider the order in which you present your body paragraphs. Often, writers will start with the findings that are most central to the research question and then move into findings that are less critical.

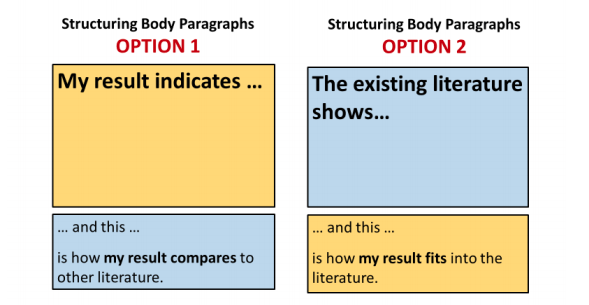

There are two main ways to organize body paragraphs in the Discussion section.

Image description: Two images showing different structures for body paragraphs. The first image [Option 1] has a large box with the text “My result indicates…” and a smaller box beneath with text “… and this … is how my result compares to other literature.” The second image [Option 2] has a large box with the text “The existing literature shows…” and a smaller box beneath with text “… and this … is how my result fits into the literature.”

Option 1 is to discuss the meaning of a result and then compare it to the existing literature. Option 2 is to write about the relevant literature and then discuss how your results fit in. Both options are valid, and you’ll see both in published research articles.

However, option 1, where you start the paragraph with your own findings, more effectively highlights your research contributions. The Discussion section is the part of your article where you get to highlight what your results mean and why your findings are important. Option 2 makes other researchers’ work the primary focus of your Discussion, and then you risk burying your own contributions, and your Discussion section could read like a literature review. It is critical to foreground your own research contributions so that readers know why your research is important.

Concluding Paragraph: Provide your acknowledgment of limitations and recommendations for future research . Note the broader implications of your study by returning to the major topic that you introduced in your opening paragraph of the research article.

Note: Sometimes the concluding paragraph of the Discussion will appear under a separate “Conclusion” heading. A conclusion notes the contribution of the study to the field and indicates what researchers should explore next. When you’re reading articles in your target journal, take note of whether these journals include a separate Conclusion section.

Writing Tips

Below are four writing tips for writing your Discussion section:

Tip 1 – Include Specific Limitations

When you’re writing your Discussion section, you may feel hesitant to include limitations. You may worry that by mentioning a limitation, you’ve brought it to the reader’s attention when the reader wouldn’t have thought of it otherwise. You may worry that by drawing attention to a limitation, you’re making your research look weak.

While some readers may not notice your limitations until you point them out, overall, academics are trained to read critically. Academics are often thinking about potential limitations as part of their critical reading practice.

While you want to indicate how your research contributes to the field, you want to be cautious about overestimating or overstating your research findings. Because readers are trained to read critically, you’ll want to be thinking about potential objections or potential questions about your work.

Write these potential objections or questions down, consider which ones are most relevant, and acknowledge them as part of writing your limitations. Acknowledging limitations qualifies your contribution in a meaningful way and strengthens your writing.

Tip 2 – Conclude with Your Contributions

In the final paragraph of your Discussion section, reiterate your major contributions to the field of research that you introduced in your introduction section. Ending with a statement of your contributions is stronger than ending with a description of your limitations. Although stating limitations is important, you also want to ensure that your reader knows why your research matters and how it contributes to the field. Information that you place at the end of a section creates emphasis. This is the information that the reader is left with, so end on a strong note.

Tip 3 – Use Signal Phrases

Throughout your Discussion, use signal phrases to highlight your key components.

Here are a couple of examples of signal phrases that you can use. “Our findings indicate that” is a simple phrase that you can use to provide your answer to the research question. “One limitation of this study is” is a direct way that you can acknowledge your limitations. These phrases are easy for your reader to spot and also easy for reviewers and editors to see.

When you’re reading other research articles, take a look at where and how writers are signalling their key components so that you can get a sense what techniques work well for you as a reader.

Tip 4 – Choose Verbs Carefully

In the Discussion section, choose verbs that accurately reflect your level of certainty about your findings. In research writing, you’ll often see verbs like “suggests,” “indicates,” and “shows.” You’ll rarely see the verb “proves” because of the extreme level of certainty associated with this word.

Within the sciences, you’re working within a tradition where you’re incrementally building upon the findings of others, and within this tradition, it can be perceived as arrogant at best or actively dangerous at worst to overstate your research findings, particularly if you’re making claims that your data don’t support.

Modal verbs like “can” and “may” qualify our level of certainty. Outside of academia, modal verbs can sometimes be viewed negatively because they can be seen to undermine the force of our statements or make our claims seem uncertain or weak. However, within research writing, modal verbs are more acceptable because we’re being cautious.

It’s important to be cautious because people may make major policy decisions or undertake particular treatment plans because of your research, so choose verbs that accurately reflect your certainty and consider that using modal verbs to qualify your level of certainty can help you advance ideas carefully while acknowledging a continued need for research. However, keep in mind that modal verbs can also be overused, so think carefully before you use one. If your findings are novel, don’t let a modal verb detract from that.

In the Discussion section, choose your verbs carefully and revise if necessary. Word choice matters.

In some disciplines within the sciences, Results and Discussion sections are combined into a single section. For example, combined Results and Discussion sections are common in research articles in engineering journals. Combined sections are also common in shorter pieces of writing and more visual mediums, such as scientific posters.

Scientists who carry out modeling and simulations will often combine their Results and Discussion sections. This approach allows them to tell a more cohesive story as they can discuss the significance of each model or simulation right after presenting the results.

If you’re opting to combine your Results and Discussion section, consider using subheadings throughout the section to make it more navigable for your reader. A combined section will often still move from presenting results at the beginning to interpreting results at the end.

When you’re investigating your target journal, explore whether writers typically combine their Results and Discussion section. If you see instances of both separate and combined sections, consider which approach will allow you to tell a cohesive story about your research while also clearly differentiating between the results of the research and your interpretations of those results.

There are many ways to approach writing the Discussion section for a mixed-methods study. Analyzing examples of mixed methods research articles from your field is a good starting place for approaching this writing task.

If you’ve conducted a mixed-methods study and have both quantitative and qualitative data, the Discussion can be a good place to provide an integrated interpretation of any relationships between both data sets. For example, you could use the following approach in a paragraph:

1) Provide a topic sentence that introduces the subject of the paragraph.

2) Discuss a quantitative result and consider comparing it to any relevant literature.

3) Discuss a qualitative result and consider comparing it to any relevant literature.

4) Explain what the quantitative and qualitative results mean when we consider them together.