Business model innovation: a review and research agenda

New England Journal of Entrepreneurship

ISSN : 2574-8904

Article publication date: 16 October 2019

Issue publication date: 13 November 2019

The aim of this paper is to review and synthesise the recent advancements in the business model literature and explore how firms approach business model innovation.

Design/methodology/approach

A systematic review of business model innovation literature was carried out by analysing 219 papers published between 2010 and 2016.

Evidence reviewed suggests that rather than taking either an evolutionary process of continuous revision, adaptation and fine-tuning of the existing business model or a revolutionary process of replacing the existing business model, firms can explore alternative business models through experimentation, open and disruptive innovations. It was also found that changing business models encompasses modifying a single element, altering multiple elements simultaneously and/or changing the interactions between elements in four areas of innovation: value proposition, operational value, human capital and financial value.

Research limitations/implications

Although this review highlights the different avenues to business model innovation, the mechanisms by which firms can change their business models and the external factors associated with such change remain unexplored.

Practical implications

The business model innovation framework can be used by practitioners as a “navigation map” to determine where and how to change their existing business models.

Originality/value

Because conflicting approaches exist in the literature on how firms change their business models, the review synthesises these approaches and provides a clear guidance as to the ways through which business model innovation can be undertaken.

- Business model

- Value proposition

- Value creation

- Value capture

Ramdani, B. , Binsaif, A. and Boukrami, E. (2019), "Business model innovation: a review and research agenda", New England Journal of Entrepreneurship , Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 89-108. https://doi.org/10.1108/NEJE-06-2019-0030

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Boumediene Ramdani, Ahmed Binsaif and Elias Boukrami

Published in New England Journal of Entrepreneurship . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Firms pursue business model innovation by exploring new ways to define value proposition, create and capture value for customers, suppliers and partners ( Gambardella and McGahan, 2010 ; Teece, 2010 ; Bock et al. , 2012 ; Casadesus-Masanell and Zhu, 2013 ). An extensive body of the literature asserts that innovation in business models is of vital importance to firm survival, business performance and as a source of competitive advantage ( Demil and Lecocq, 2010 ; Chesbrough, 2010 ; Amit and Zott, 2012 ; Baden-Fuller and Haefliger, 2013 ; Casadesus-Masanell and Zhu, 2013 ). It is starting to attract a growing attention, given the increasing opportunities for new business models enabled by changing customer expectations, technological advances and deregulation ( Casadesus-Masanell and Llanes, 2011 ; Casadesus-Masanell and Zhu, 2013 ). This is evident from the recent scholarly outputs ( Figure 1 ). Thus, it is essential to comprehend this literature and uncover where alternative business models can be explored.

Conflicting approaches exist in the literature on how firms change their business models. One approach suggests that alternative business models can be explored through an evolutionary process of incremental changes to business model elements (e.g. Demil and Lecocq, 2010 ; Dunford et al. , 2010 ; Amit and Zott, 2012 ; Landau et al. , 2016 ; Velu, 2016 ). The other approach, mainly practice-oriented, advocates that innovative business models can be developed through a revolutionary process by replacing existing business models (e.g. Bock et al. , 2012 ; Iansiti and Lakhani, 2014 ). The fragmentation of prior research is due to the variety of disciplinary and theoretical foundations through which business model innovation is examined. Scholars have drawn on perspectives from entrepreneurship (e.g. George and Bock, 2011 ), information systems (e.g. Al-debei and Avison, 2010 ), innovation management (e.g. Dmitriev et al. , 2014 ), marketing (e.g. Sorescu et al. , 2011 ) and strategy (e.g. Demil and Lecocq, 2010 ). Also, this fragmentation is deepened by focusing on different types of business models in different industries. Studies have explored different types of business models such as digital business models (e.g. Weill and Woerner, 2013 ), service business models (e.g. Kastalli et al. , 2013 ), social business models (e.g. Hlady-Rispal and Servantie, 2016 ) and sustainability-driven business models ( Esslinger, 2011 ). Besides, studies have examined different industries such as airline ( Lange et al. , 2015 ), manufacturing ( Landau et al. , 2016 ), newspaper ( Karimi and Walter, 2016 ), retail ( Brea-Solís et al. , 2015 ) and telemedicine ( Peters et al. , 2015 ).

Since the first comprehensive review of business model literature was carried out by Zott et al. (2011) , several reviews were published recently (as highlighted in Table I ). Our review builds on and extends the extant literature in at least three ways. First, unlike previous reviews that mainly focused on the general construct of “Business Model” ( George and Bock, 2011 ; Zott et al. , 2011 ; Wirtz et al. , 2016 ), our review focuses on uncovering how firms change their existing business model(s) by including terms that reflect business model innovation, namely, value proposition, value creation and value capture. Second, previous reviews do not provide a clear answer as to how firms change their business models. Our review aims to provide a clear guidance on how firms carry out business model innovation by synthesising the different perspectives existing in the literature. Third, compared to recent reviews on business model innovation ( Schneider and Spieth, 2013 ; Spieth et al. , 2014 ), which have touched lightly on some innovation aspects such as streams and motivations of business model innovation research, our review will uncover the innovation areas where alternative business models can be explored. Taking Teece’s (2010) suggestion, “A helpful analytic approach for management is likely to involve systematic deconstruction/unpacking of existing business models, and an evaluation of each element with an idea toward refinement or replacement” (p. 188), this paper aims to develop a theoretical framework of business model innovation.

Our review first explains the scope and the process of the literature review. This is followed by a synthesis of the findings of the review into a theoretical framework of business model innovation. Finally, avenues for future research will be discussed in relation to the approaches, degree and mechanisms of business model innovation.

2. Scope and method of the literature review

Given the diverse body of business models literature, a systematic literature review was carried out to minimise research bias ( Transfield et al. , 2003 ). Compared to the previous business model literature, our review criteria are summarised in Table I . The journal papers considered were published between January 2010 and December 2016. As highlighted in Figure 1 , most contributions in this field have been issued within this period since previous developments in the literature were comprehensively reviewed up to the end of 2009 ( Zott et al. , 2011 ). Using four databases (EBSCO Business Complete, ABI/INFORM, JSTOR and ScienceDirect), we searched peer-reviewed papers with terms such as business model(s), innovation value proposition, value creation and value capture appearing in the title, abstract or subject terms. As a result, 8,642 peer-reviewed papers were obtained.

Studies were included in our review if they specifically address business models and were top-rated according to The UK Association of Business Schools list ( ABS, 2010 ). This rating has been used not only because it takes into account the journal “Impact Factor” as a measure for journal quality, but also uses in conjunction other measures making it one of the most comprehensive journal ratings. By applying these criteria, 1,682 entries were retrieved from 122 journals. By excluding duplications, 831 papers were identified. As Harvard Business Review is not listed among the peer-reviewed journals in any of the chosen databases and was included in the ABS list, we used the earlier criteria and found 112 additional entries. The reviewed papers and their subject fields are highlighted in Table II . Since the focus of this paper is on business model innovation, we selected studies that discuss value proposition, value creation and value capture as sub-themes. This is not only because the definition of business model innovation mentioned earlier spans all three sub-themes, but also because all three sub-themes have been included in recent studies (e.g. Landau et al. , 2016 ; Velu and Jacob, 2014 ). To confirm whether the papers addressed business model innovation, we examined the main body of the papers to ensure they were properly coded and classified. At the end of the process, 219 papers were included in this review. Table III lists the source of our sample.

The authors reviewed the 219 papers using a protocol that included areas of innovation (i.e. components, elements, and activities), theoretical perspectives and key findings. In order to identify the main themes of business model innovation research, all papers were coded in relation to our research focus as to where alternative business models can be explored (i.e. value proposition, value creation and value capture). Coding was cross checked among the authors on a random sample suggesting high accuracy between them. Having compared and discussed the results, the authors were able to identify the main themes.

3. Prior conceptualisations of business model innovation

Some scholars have articulated the need to build the business model innovation on a more solid theoretical ground ( Sosna et al. , 2010 ; George and Bock, 2011 ). Although many studies are not explicitly theory-based, some studies partially used well-established theories such as the resource-based view (e.g. Al-Debei and Avison, 2010 ) and transaction cost economics (e.g. DaSilva and Trkman, 2014 ) to conceptualise business model innovation. Other theories such as activity systems perspective, dynamic capabilities and practice theory have been used to help answer the question of how firms change their existing business models.

Using the activity systems perspective, Zott and Amit (2010) demonstrated how innovative business models can be developed through the design themes that describe the source of value creation (novelty, lock-in, complementarities and efficiency) and design elements that describe the architecture (content, structure and governance). This work, however, overlooks value capture which limits the explanation of the advocated system’s view (holistic). Moreover, Chatterjee (2013) used this perspective to reveal that firms can design innovative business models that translate value capture logic to core objectives, which can be delivered through the activity system.

Dynamic capability perspective frames business model innovation as an initial experiment followed by continuous revision, adaptation and fine-tuning based on trial-and-error learning ( Sosna et al. , 2010 ). Using this perspective, Demil and Lecocq (2010) showed that “dynamic consistency” is a capability that allows firms to sustain their performance while innovating their business models through voluntary and emergent changes. Also, Mezger (2014) conceptualised business model innovation as a distinct dynamic capability. He argued that this capability is the firm’s capacity to sense opportunities, seize them through the development of valuable and unique business models, and accordingly reconfigure the firms’ competences and resources. Using aspects of practice theory, Mason and Spring (2011) looked at business model innovation in the recorded sound industry and found that it can be achieved through various combinations of managerial practices.

Static and transformational approaches have been used to depict business models ( Demil and Lecocq, 2010 ). The former refers to viewing business models as constituting core elements that influence business performance at a particular point in time. This approach offers a snapshot of the business model elements and how they are assembled, which can help in understanding and communicating a business model (e.g. Eyring et al. , 2011 ; Mason and Spring, 2011 ; Yunus et al. , 2010). The latter, however, focuses on innovation and how to address the changes in business models over time (e.g. Sinfield et al. , 2012 ; Girotra and Netessine, 2014 ; Landau et al. , 2016 ). Some researchers have identified the core elements of business models ex ante (e.g. Demil and Lecocq, 2010 ; Wu et al. , 2010 ; Huarng, 2013 ; Dmitriev et al. , 2014 ), while others argued that considering a priori elements can be restrictive (e.g. Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart, 2010 ). Unsurprisingly, some researchers found a middle ground where elements are loosely defined allowing flexibility in depicting business models (e.g. Zott and Amit, 2010 ; Sinfield et al. , 2012 ; Kiron et al. , 2013 ).

Prior to 2010, conceptual frameworks focused on the business model concept in general (e.g. Chesbrough and Rosenbloom, 2002 ; Osterwalder et al. , 2005 ; Shafer et al. , 2005 ) apart from Johnson et al. ’s (2008 ), which is one of the early contributions to business model innovation. To determine whether a change in existing business model is necessary, Johnson et al. (2008) suggested three steps: “Identify an important unmet job a target customer needs done; blueprint a model that can accomplish that job profitably for a price the customer is willing to pay; and carefully implement and evolve the model by testing essential assumptions and adjusting as you learn” ( Eyring et al. , 2011 , p. 90). Although several frameworks have been developed since then, our understanding of business model innovation is still limited due to the static nature of the majority of these frameworks. Some representations ignore the elements and/or activities where alternative business models can be explored (e.g. Sinfield et al. , 2012 ; Chatterjee, 2013 ; Huarng, 2013 ; Morris et al. , 2013 ; Dmitriev et al. , 2014 ; Girotra and Netessine, 2014 ). Other frameworks ignore value proposition (e.g. Zott and Amit, 2010 ), ignore value creation (e.g. Dmitriev et al. , 2014 ; Michel, 2014 ) and/or ignore value capture (e.g. Mason and Spring, 2011 ; Sorescu et al. , 2011 ; Storbacka, 2011 ). Some conceptualisations do not identify who is responsible for the innovation (e.g. Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart, 2010 ; Sinfield et al. , 2012 ; Chatterjee, 2013 ; Kiron et al. , 2013 ). Synthesising the different contributions into a theoretical framework of business model innovation will enable a better understanding of how firms undertake business model innovation.

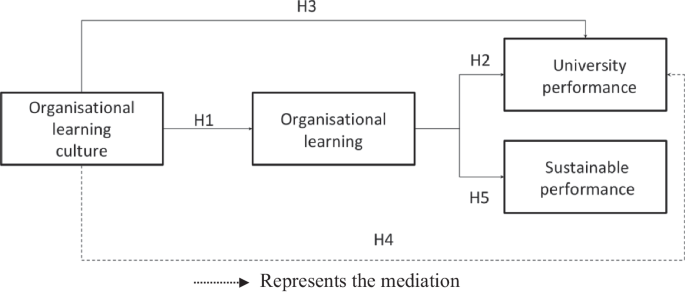

4. Business model innovation framework

Our framework ( Figure 2 ) integrates all the elements where alternative business models can be explored. This framework does not claim that the listed elements are definitive for high-performing business models, but is an attempt to outline the elements associated with business model innovation. This framework builds on the previous work of Johnson et al. (2008) and Zott and Amit (2010) by signifying the elements associated with business model innovation. Unlike previous frameworks that mainly consider the constituting elements of business models, this framework focuses on areas of innovation where alternative business models can be explored. Moreover, this is not a static view of the constituting elements of a business model, but rather a view enabling firms to explore alternative business models by continually refining these elements. Arrows in the framework indicate the continuous interaction of business model elements. This framework consists of 4 areas of innovation and 16 elements (more details are shown in Table IV ). Each will be discussed below.

4.1 Value proposition

The first area of innovation refers to elements associated with answering the “Why” questions. While most of the previously established models in the literature include at least one of the value proposition elements (e.g. Brea-Solís et al. , 2015 ; Christensen et al. , 2016 ), other frameworks included two elements (e.g. Dahan et al. , 2010 ; Cortimiglia et al. , 2016 ) and three elements (e.g. Eyring et al. , 2011 ; Sinfield et al. , 2012 ). These elements include rethinking what a company sells, exploring new customer needs, acquiring target customers and determining whether the benefits offered are perceived by customers. Modern organisations are highly concerned with innovation relating to value proposition in order to attract and retain a large portion of their customer base ( Al-Debei and Avison, 2010 ). Developing new business models usually starts with articulating a new customer value proposition ( Eyring et al. , 2011 ). According to Sinfield et al. (2012) , firms are encouraged to explore various alternatives of core offering in more depth by examining type of offering (product or service), its features (custom or off-the-shelf), offered benefits (tangible or intangible), brand (generic or branded) and lifetime of the offering (consumable or durable).

In order to exploit the “middle market” in emerging economies, Eyring et al. (2011) suggested that companies need to design new business models that aim to meet unsatisfied needs and evolve these models by continually testing assumptions and making adjustments. To uncover unmet needs, Eyring et al. (2011) suggested answering four questions: what are customers doing with the offering? What alternative offerings consumers buy? What jobs consumers are satisfying poorly? and what consumers are trying to accomplish with existing offerings? Furthermore, Baden-Fuller and Haefliger (2013) made a distinction between customers and users in two-sided platforms, where users search for products online, and customers (firms) place ads to attract users. They also made a distinction between “pre-designed (scale) based offerings” and “project based offerings”. While the former focuses on “one-size-fits-all”, the latter focuses on specific client solving specific problem.

Established firms entering emerging markets should identify unmet needs “the job to be done” rather than extending their geographical base for existing offerings ( Eyring et al. , 2011 ). Because customers in these markets cannot afford the cheapest of the high-end offerings, firms with innovative business models that meet these customers’ needs affordably will have opportunities for growth ( Eyring et al. , 2011 ). Moreover, secondary business model innovation has been advocated by Wu et al. (2010) as a way for latecomer firms to create and capture value from disruptive technologies in emerging markets. This can be achieved through tailoring the original business model to fit price-sensitive mass customers by articulating a value proposition that is attractive for local customers.

4.2 Operational value

The second area of innovation focuses on elements associated with answering the “What” questions. Many of the established frameworks included either one element (e.g. Sinfield et al. , 2012 ; Taran et al. , 2015 ), two elements (e.g. Mason and Spring, 2011 ; Dmitriev et al. , 2014 ). However, very few included three or more elements (e.g. Mehrizi and Lashkarbolouki, 2016 ; Cortimiglia et al. , 2016 ). These elements include configuring key assets and sequencing activities to deliver the value proposition, exposing the various means by which a company reaches out to customers, and establishing links with key partners and suppliers. Focusing on value creation, Zott and Amit (2010) argued that business model innovation can be achieved through reorganising activities to reduce transaction costs. However, Al-Debei and Avison (2010) argued that innovation relating to this dimension can be achieved through resource configuration, which demonstrates a firm’s ability to integrate various assets in a way that delivers its value proposition. Cavalcante et al. (2011) proposed four ways to change business models: business model creation, extension, revision and termination by creating or adding new processes, and changing or terminating existing processes.

Western firms have had difficulty competing in emerging markets due to importing their existing business models with unchanged operating model ( Eyring et al. , 2011 ). Alternative business models can be uncovered when firms explore the different roles they might play in the industry value chain ( Sinfield et al. , 2012 ). Al-Debei and Avison (2010) suggested achieving this through answering questions such as: what is the position of our firm in the value system? and what mode of collaboration (open or close) would we choose to reach out in a business network? Dahan et al. (2010) found cross-sector partnerships as a way to co-create new multi-organisational business models. They argued that multinational enterprises (MNEs) can collaborate with nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) to create products/or services that neither can create on their own. Collaboration allows access to resources that firms would otherwise need to solely develop or purchase ( Yunus et al. , 2010 ). According to Wu et al. (2010) , secondary business model innovation can be achieved when latecomer firms fully utilise strategic partners’ complementary assets to overcome their latecomer disadvantages and build a unique value network specific to emerging economies context.

4.3 Human capital

The third area of innovation refers to elements associated with answering the “Who” questions. Most of the established frameworks in this field tend to focus less on human capital and include one element at most (e.g. Wu et al. , 2010 ; Kohler, 2015 ). However, our framework highlights four elements, which include experimenting with new ways of doing business, tapping into the skills and competencies needed for the new business model through motivating and involving individuals in the innovation process. According to Belenzon and Schankerman (2015) , “the ability to tap into a pool of talent is strongly related to the specific business model chosen by managers” (p. 795). They claimed that managers can strategically influence individuals’ contributions and their impact on project performance.

Organisational learning can be maximised though continuous experimentation and making changes when actions result in failure ( Yunus et al. , 2010 ). Challenging and questioning the existing rules and assumptions and imagining new ways of doing business will help develop new business models. Another essential element of business model design is governance, which refers to who performs the activities ( Zott and Amit, 2010 ). According to Sorescu et al. (2011) , innovation in retail business models can occur as a result of changes in the level of participation by actors engaged in performing the activities. An essential element of retailing governance is the incentive structure or the mechanisms that motivate those involved in carrying out their roles to meet customer demands ( Sorescu et al. , 2011 ). For example, discount retailers tend to establish different compensation and incentive policies ( Brea-Solís et al. , 2015 ). Revising the incentive system can have a major impact on new ventures’ performance by aligning organisational goals at each stage of growth ( Roberge, 2015 ). Zott and Amit (2010) argued that alternative business models can be explored through adopting innovative governance or changing one or more parties that perform any activities. Sinfield et al. (2012) suggested that business model innovation only requires time from a small team over a short period of time to move a company beyond incremental improvements and generate new opportunities for growth. This is supported by Michel’s (2014) finding that cross-functional teams were able to quickly achieve business model innovation in workshops through deriving new ways to capture value.

4.4 Financial value

The final area of innovation focuses on elements associated with answering the “How” questions. Previously developed frameworks tend to prioritise this area of innovation by three elements (e.g. Eyring et al. , 2011 ; Huang et al. , 2013 ), and in one instance four elements (e.g. Yunus et al. , 2010 ). These elements include activities linked with how to capture value through revenue streams, changing the price-setting mechanisms, and assessing the financial viability and profitability of a business. According to Demil and Lecocq (2010) , changes in cost and/or revenue structures are the consequences of both continuous and radical changes. They also argued that costs relate to different activities run by organisations to acquire, integrate, combine or develop resources. Michel (2014) suggested that alternative business models can be explored through: changing the price-setting mechanism, changing the payer, and changing the price carrier. Different innovation forms are associated with each of these categories.

Business model innovation can be achieved through exploring new ways to generate cash flows ( Sorescu et al. , 2011 ), where the organisation has to consider (and potentially change) when the money is collected: prior to the sale, at the point of sale, or after the sale ( Baden-Fuller and Haefliger, 2013 ). Furthermore, Demil and Lecocq (2010) suggested that changes in business models affect margins. This is apparent in the retail business models, which generate more profit through business model innovation compared to other types of innovation ( Sorescu et al. , 2011 ).

5. Ways to change business models

From reviewing the recent developments in the business model literature, alternative business models can be explored through modifying a single business model element, altering multiple elements simultaneously and/or changing the interactions between elements of a business model.

Changing one of the business model elements (i.e. content, structure or governance) is enough to achieve business model innovation ( Amit and Zott, 2012 ). This means that firms can have a new activity system by performing only one new activity. However, Amit and Zott (2012) clearly outlined a systemic view of business models which entails a holistic change. This is evident from Demil and Lecocq’s (2010) work suggesting that the study of business model innovation should not focus on isolated activities since changing a core element will not only impact other elements but also the interactions between these elements.

Another way to change business models is through altering multiple business model elements simultaneously. Kiron et al. (2013) found that companies combining target customers with value chain innovations and changing one or two other elements of their business models tend to profit from their sustainability activities. They also found that firms changing three to four elements of their business models tend to profit more from their sustainability activities compared to those changing only one element. Moreover, Dahan et al. (2010) found that a new business model was developed as a result of MNEs and NGOs collaboration by redefining value proposition, target customers, governance of activities and distribution channels. Companies can explore multiple combinations by listing different business model options they could undertake (desirable, discussable and unthinkable) and evaluate new combinations that would not have been considered otherwise ( Sinfield et al. , 2012 ).

Changing business models is argued to be demanding as it requires a systemic and holistic view ( Amit and Zott, 2012 ) by considering the relationships between core business model elements ( Demil and Lecocq, 2010 ). As mentioned earlier, changing one element will not only impact other elements but also the interactions between these elements. A firm’s resources and competencies, value proposition and organisational system are continuously interacting and this will in turn impact business performance either positively or negatively ( Demil and Lecocq, 2010 ). According to Zott and Amit (2010) , innovative business models can be developed through linking activities in a novel way that generates more value. They argued that alternative business models can be explored by configuring business model design elements (e.g. governance) and connecting them to distinct themes (e.g. novelty). Supporting this, Eyring et al. (2011) suggested that core business model elements need to be integrated in order to create and capture value ( Eyring et al. , 2011 ).

6. Discussion and future research directions

From the above synthesis of the recent development in the literature, several gaps remain unfilled. To advance the literature, possible future research directions will be discussed in relation to approaches, degrees and mechanisms of business model innovation.

6.1 Approaches of business model innovation

Experimentation, open innovation and disruption have been advocated as approaches to business model innovation. Experimentation has been emphasised as a way to exploit opportunities and develop alternative business models before committing additional investments ( McGrath, 2010 ). Several approaches have been developed to assist in business model experimentation including mapping approach, discovery-driven planning and trail-and-error learning ( Chesbrough, 2010 ; McGrath, 2010 ; Sosna et al. , 2010 ; Andries and Debackere, 2013 ). Little is known about the effectiveness of these approaches. It will be worth investigating which elements of the business model innovation framework are more susceptible to experimentation and which elements should be held unchanged. Although business model innovation tends to be characterised with failure ( Christensen et al. , 2016 ), not much has been established on failing business models. It is interesting to explore how firms determine a failing business model and what organisational processes exist (if any) to evaluate and discard these failed business models. Empirical studies could examine which elements of business model innovation framework are associated with failing business models.

Another way to develop alternative business models is through open innovation. Although different categories of open business models have been identified by researchers (e.g. Frankenberger et al. , 2014 ; Taran et al. , 2015 ; Kortmann and Piller, 2016 ), their effectiveness is yet to be established. Further research is needed to examine when can a firm open and/or close element(s) of the business model innovation framework. Future studies could also examine the characteristics of open and/or close business models.

In responding to disruptive business models, how companies extend their existing business model, introduce additional business model(s) and/or replace their existing business model altogether remains underexplored. Future research is needed to unravel the strategies deployed by firms to extend their existing business models as a response to disruptive business models. In introducing additional business models, Markides (2013) suggested that a company will be presented with several options to manage the two businesses at the same time: create a completely separate business unit, integrate the two business models from the beginning or integrate the second business model after a certain period of time. Finding the balance between separation and integration is of vital importance. Further research could identify which of these choices are most common among successful firms introducing additional business models, how is the balance between integration and separation achieved, and which choice(s) prove more profitable. Moreover, very little is known on how firms replace their existing business model. Longitudinal studies could provide insights into how a firm adopts an alternative model and discard the old business model over time. It may also be worth examining the factors associated with the adoption of business model innovation as a response to disruptive business models. Moreover, new developments in digital technologies such as blockchain, Internet of Things and artificial intelligence are disrupting existing business models and providing firms with alternative avenues to create new business models. Thus far, very little is known on digital business models, the nature of their disruption, and how firms create digital business models and make them disruptive. Future research is needed to fill these important gaps in our knowledge.

6.2 Degrees of business model innovation

Business models can be developed through varying degrees of innovation from an evolutionary process of continuous fine-tuning to a revolutionary process of replacing existing business models. Recent research shows that survival of firms is dependent on the degree of their business model innovation ( Velu, 2015, 2016 ). This review classifies these degrees of innovation into modifying a single element, altering multiple elements simultaneously and/or changing the interactions between elements of the business model innovation framework.

In changing a single element, further research is needed to examine which business model element(s) is (are) associated with business model innovation. It is not clear whether firms intentionally make changes to a single element when carrying out business model innovation or stumble at it when experimenting with new ways of doing things. It may also be worth investigating the entry (or starting) points in the innovation process. There is no consensus in the literature on which element do companies start with when carrying out their business model innovation. While some studies suggest starting with the value proposition ( Eyring et al. , 2011 ; Landau et al. , 2016 ), others suggest starting the innovation process with identifying risks in the value chain ( Girotra and Netessine, 2011 ). Dmitriev et al. (2014) suggested two entry points, namely, value proposition and target customers. In commercialising innovations, the former refers to technology-push innovation while the latter refers to market-pull innovation. Also, it is not clear whether the entry point is the same as the single element associated with changing the business model. Further research can explore the different paths to business model innovation by identifying the entry point and subsequent changes needed to achieve business model innovation.

There is little guidance in the literature on how firms change multiple business model elements simultaneously. Landau et al. (2016) claimed that firms entering emerging markets tend to focus on adjusting specific business model components. It is unclear which elements need configuring, combining and/or integrating to achieve a company’s value proposition. Furthermore, the question of which elements can be “bought” on the market or internally “implemented” and their interplay remains unanswered ( DaSilva and Trkman, 2014 ). Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010) argued that “[…] there is (as yet) no agreement as to the distinctive features of superior business models” (p. 196). Further research is needed to explore these distinctive elements of high-performing business models.

In changing the interactions between business model elements, further research is needed to explore how these elements are linked and what interactions’ changes are necessary to achieve business model innovation. Moreover, the question of how firms sequence these elements remains poorly understood. Future research can explore the synergies created over time between these elements. According to Dmitriev et al. (2014) , we need to improve our understanding of the connective mechanisms and dynamics involved in business model development. More work is needed to explore the different modalities of interdependencies among these elements and empirically testing such interdependencies and their effect on business performance ( Sorescu et al. , 2011 ).

It is surprising that the link between business model innovation and organisational performance has rarely been examined. Changing business models has been found to negatively influence business performance even if it is temporary ( McNamara et al. , 2013 ; Visnjic et al. , 2016 ). Contrary to this, evidence show that modifying business models is positively associated with organisational performance ( Cucculelli and Bettinelli, 2015 ). Empirical research is needed to operationalise the various degrees of innovation in business models and examine their link to organisational performance. Longitudinal studies can also be used to explore this association since it may be the case that business model innovation has a negative influence on performance in the short run and that may change subsequently. Moreover, it is not clear whether high-performing firms change their business models or innovation in business models is a result from superior performance ( Sorescu et al. , 2011 ). Further studies are needed to determine the direction of causality. Another link that is worth exploring is business model innovation and social value, which has only been explored in a few studies looking at social business models (e.g. Yunus et al. , 2010 ; Wilson and Post, 2013 ). Further research is needed to examine this link and possibly examine both financial and non-financial business performance.

6.3 Mechanisms of business model innovation

Although we know more about how firms define value proposition, create and capture value ( Landau et al. , 2016 ; Velu and Jacob, 2014 ), what remains as a blind spot is the mechanism of business model innovation. This is due to the fact that much of the literature seems to focus on value creation. To better understand the various mechanisms of business model innovation, future studies must integrate value proposition, value creation and value capture elements. Empirical studies could use the business model innovation framework to examine the various mechanisms of business model innovation. Also, the literature lacks the integration of internal and external perspectives of business model innovation. Very few studies look at the external drivers of business model innovation and the associated internal changes. The external drivers are referred to as “emerging changes”, which are usually beyond manager’s control ( Demil and Lecocq, 2010 ). Inconclusive findings exist as to how firms develop innovative business models in response to changes in the external environment. Future studies could examine the external factors associated with the changes in the business model innovation framework. Active and reactive responses need to be explored not only to understand the external influences, but also what business model changes are necessary for such responses. A better understanding of the mechanisms of business model innovation can be achieved by not only exploring the external drivers, but also linking them to specific internal changes. Although earlier contributions linking studies to established theories such as the resource-based view, transaction cost economics, activity systems perspective, dynamic capabilities and practice theory have proven to be vital in advancing the literature, developing a theory that elaborates on the antecedents, consequences and different facets of business model innovation is still needed ( Sorescu et al. , 2011 ). Theory can be advanced by depicting the mechanisms of business model innovation through the integration of both internal and external perspectives. Also, we call for more empirical work to uncover these mechanisms and provide managers with the necessary insights to carry out business model innovation.

7. Conclusions

The aim of this review was to explore how firms approach business model innovation. The current literature suggests that business model innovation approaches can either be evolutionary or revolutionary. However, the evidence reviewed points to a more complex picture beyond the simple binary approach, in that, firms can explore alternative business models through experimentation, open and disruptive innovations. Moreover, the evidence highlights further complexity to these approaches as we find that they are in fact a spectrum of various degrees of innovation ranging from modifying a single element, altering multiple elements simultaneously, to changing the interactions between elements of the business model innovation framework. This framework was developed as a navigation map for managers and researchers interested in how to change existing business models. It highlights the key areas of innovation, namely, value proposition, operational value, human capital and financial value. Researchers interested in this area can explore and examine the different paths firms can undertake to change their business models. Although this review pinpoints the different avenues for firm to undertake business model innovation, the mechanisms by which firms can change their business models and the external factors associated with such change remain underexplored.

The evolution of business model literature (pre-2000 to 2016)

Business model innovation framework

Previous reviews of business model literature

Reviewed papers and their subject fields

Source of our sample

Business model innovation areas and elements

ABS ( 2010 ), Academic Journal Quality Guide , Version 4 , The Association of Business Schools , London .

Al-Debei , M.M. and Avison , D. ( 2010 ), “ Developing a unified framework of the business model concept ”, European Journal of Information Systems , Vol. 19 No. 3 , pp. 359 - 376 .

Amit , R. and Zott , C. ( 2012 ), “ Creating value through business model innovation ”, MIT Sloan Management Review , Vol. 53 No. 3 , pp. 41 - 49 .

Andries , P. and Debackere , K. ( 2013 ), “ Business model innovation: Propositions on the appropriateness of different learning approaches ”, Creativity and Innovation Management , Vol. 22 No. 4 , pp. 337 - 358 .

Baden-Fuller , C. and Haefliger , S. ( 2013 ), “ Business models and technological innovation ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 46 No. 6 , pp. 419 - 426 .

Belenzon , S. and Schankerman , M. ( 2015 ), “ Motivation and sorting of human capital in open innovation ”, Strategic Management Journal , Vol. 36 No. 6 , pp. 795 - 820 .

Bock , A.J. , Opsahl , T. , George , G. and Gann , D.M. ( 2012 ), “ The effects of culture and structure on strategic flexibility during business model innovation ”, Journal of Management Studies , Vol. 49 No. 2 , pp. 279 - 305 .

Brea-Solís , H. , Casadesus-Masanell , R. and Grifell-Tatjé , E. ( 2015 ), “ Business model evaluation: quantifying Walmart’s sources of advantage ”, Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal , Vol. 9 No. 1 , pp. 12 - 33 .

Casadesus-Masanell , R. and Llanes , G. ( 2011 ), “ Mixed source ”, Management Science , Vol. 57 No. 7 , pp. 1212 - 1230 .

Casadesus-Masanell , R. and Ricart , J.E. ( 2010 ), “ From strategy to business models and onto tactics ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 43 Nos 2-3 , pp. 195 - 215 .

Casadesus-Masanell , R. and Zhu , F. ( 2013 ), “ Business model innovation and competitive imitation: the case of sponsor-based business models ”, Strategic Management Journal , Vol. 34 No. 4 , pp. 464 - 482 .

Chatterjee , S. ( 2013 ), “ Simple rules for designing business models ”, California Management Review , Vol. 55 No. 2 , pp. 97 - 124 .

Cavalcante , S. , Kesting , P. and Ulhøi , J. ( 2011 ), “ Business model dynamics and innovation: (re)establishing the missing linkages ”, Management Decision , Vol. 49 No. 8 , pp. 1327 - 1342 .

Chesbrough , H. ( 2010 ), “ Business model innovation: opportunities and barriers ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 43 Nos. 2-3 , pp. 354 - 363 .

Chesbrough , H. and Rosenbloom , R.S. ( 2002 ), “ The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox corporation’s technology spin off companies ”, Industrial & Corporate Change , Vol. 11 No. 3 , pp. 529 - 555 .

Christensen , C.M. , Bartman , T. and Van Bever , D. ( 2016 ), “ The hard truth about business model innovation ”, MIT Sloan Management Review , Vol. 58 No. 1 , pp. 31 - 40 .

Cortimiglia , M.N. , Ghezzi , A. and Frank , A.G. ( 2016 ), “ Business model innovation and strategy making nexus: evidence from a cross‐industry mixed‐methods study ”, R&D Management , Vol. 46 No. 3 , pp. 414 - 432 .

Cucculelli , M. and Bettinelli , C. ( 2015 ), “ Business models, intangibles and firm performance: evidence on corporate entrepreneurship from Italian manufacturing SMEs ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 45 No. 2 , pp. 329 - 350 .

Dahan , N.M. , Doh , J.P. , Oetzel , J. and Yaziji , M. ( 2010 ), “ Corporate-NGO collaboration: Co-creating new business models for developing markets ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 43 Nos 2-3 , pp. 326 - 342 .

DaSilva , C.M. and Trkman , P. ( 2014 ), “ Business model: what it is and what it is not ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 47 No. 6 , pp. 379 - 389 .

Demil , B. and Lecocq , X. ( 2010 ), “ Business model evolution: in search of dynamic consistency ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 43 Nos 2-3 , pp. 227 - 246 .

Dmitriev , V. , Simmons , G. , Truong , Y. , Palmer , M. and Schneckenberg , D. ( 2014 ), “ An exploration of business model development in the commercialization of technology innovations ”, R&D Management , Vol. 44 No. 3 , pp. 306 - 321 .

Dunford , R. , Palmer , I. and Benveniste , J. ( 2010 ), “ Business model replication for early and rapid internationalisation: the ING direct experience ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 43 Nos 5-6 , pp. 655 - 674 .

Esslinger , H. ( 2011 ), “ Sustainable design: beyond the innovation-driven business model ”, The Journal of Product Innovation Management , Vol. 28 No. 3 , pp. 401 - 404 .

Eyring , M.J. , Johnson , M.W. and Nair , H. ( 2011 ), “ New business models in emerging markets ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 89 No. 1 , pp. 89 - 95 .

Frankenberger , K. , Weiblen , T. and Gassmann , O. ( 2014 ), “ The antecedents of open business models: an exploratory study of incumbent firms ”, R&D Management , Vol. 44 No. 2 , pp. 173 - 188 .

Gambardella , A. and McGahan , A.M. ( 2010 ), “ Business-model innovation: general purpose technologies and their implications for industry structure ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 43 Nos 2-3 , pp. 262 - 271 .

George , G. and Bock , A.J. ( 2011 ), “ The business model in practice and its implications for entrepreneurship research ”, Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice , Vol. 35 No. 1 , pp. 83 - 111 .

Girotra , K. and Netessine , S. ( 2011 ), “ How to build risk into your business model ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 89 No. 5 , pp. 100 - 105 .

Girotra , K. and Netessine , S. ( 2014 ), “ Four paths to business model innovation ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 92 No. 7 , pp. 96 - 103 .

Hartmann , P.M. , Hartmann , P.M. , Zaki , M. , Zaki , M. , Feldmann , N. and Neely , A. ( 2016 ), “ Capturing value from Big Data – a taxonomy of data-driven business models used by start-up firms ”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management , Vol. 36 No. 10 , pp. 1382 - 1406 .

Hlady-Rispal , M. and Servantie , V. ( 2016 ), “ Business models impacting social change in violent and poverty-stricken neighbourhoods: a case study in Colombia ”, International Small Business Journal , Vol. 35 No. 4 , pp. 1 - 22 .

Huang , H.C. , Lai , M.C. , Lin , L.H. and Chen , C.T. ( 2013 ), “ Overcoming organizational inertia to strengthen business model innovation: an open innovation perspective ”, Journal of Organizational Change Management , Vol. 26 No. 6 , pp. 977 - 1002 .

Huarng , K.-H. ( 2013 ), “ A two-tier business model and its realization for entrepreneurship ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 66 No. 10 , pp. 2102 - 2105 .

Iansiti , M. and Lakhani , K.R. ( 2014 ), “ Digital ubiquity: how connections, sensors, and data are revolutionizing business ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 92 No. 11 , pp. 91 - 99 .

Johnson , M.W. , Christensen , C.M. and Kagermann , H. ( 2008 ), “ Reinventing your business model ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 86 No. 12 , pp. 57 - 68 .

Karimi , J. and Walter , Z. ( 2016 ), “ Corporate entrepreneurship, disruptive business model innovation adoption, and its performance: the case of the newspaper industry ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 49 No. 3 , pp. 342 - 360 .

Kastalli , I. , Van Looy , B. and Neely , A. ( 2013 ), “ Steering manufacturing firms towards service business model innovation ”, California Management Review , Vol. 56 No. 1 , pp. 100 - 123 .

Kohler , T. ( 2015 ), “ Crowdsourcing-based business models ”, California Management Review , Vol. 57 No. 4 , pp. 63 - 84 .

Kiron , D. , Kruschwitz , N. , Haanaes , K. , Reeves , M. and Goh , E. ( 2013 ), “ The innovation bottom line ”, MIT Sloan Management Review , Vol. 54 No. 2 , pp. 1 - 20 .

Klang , D. , Wallnöfer , M. and Hacklin , F. ( 2014 ), “ The business model paradox: a systematic review and exploration of antecedents ”, International Journal of Management Reviews , Vol. 16 No. 4 , pp. 454 - 478 .

Kortmann , S. and Piller , F. ( 2016 ), “ Open business models and closed-loop value chains ”, California Management Review , Vol. 58 No. 3 , pp. 88 - 108 .

Landau , C. , Karna , A. and Sailer , M. ( 2016 ), “ Business model adaptation for emerging markets: a case study of a German automobile manufacturer in India ”, R&D Management , Vol. 46 No. 3 , pp. 480 - 503 .

Lange , K. , Geppert , M. , Saka-Helmhout , A. and Becker-Ritterspach , F. ( 2015 ), “ Changing business models and employee representation in the airline industry: a comparison of British Airways and Deutsche Lufthansa ”, British Journal of Management , Vol. 26 No. 3 , pp. 388 - 407 .

McGrath , R.G. ( 2010 ), “ Business models: a discovery driven approach ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 43 Nos. 2-3 , pp. 247 - 261 .

McNamara , P. , Peck , S.I. and Sasson , A. ( 2013 ), “ Competing business models, value creation and appropriation in English football ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 46 No. 6 , pp. 475 - 487 .

Markides , C.C. ( 2013 ), “ Business model innovation: what can the ambidexterity literature teach us? ”, Academy of Management Perspectives , Vol. 27 No. 3 , pp. 313 - 323 .

Mason , K. and Spring , M. ( 2011 ), “ The sites and practices of business models ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 40 No. 6 , pp. 1032 - 1041 .

Mehrizi , M.H.R. and Lashkarbolouki , M. ( 2016 ), “ Unlearning troubled business models: from realization to marginalization ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 49 No. 3 , pp. 298 - 323 .

Mezger , F. ( 2014 ), “ Toward a capability-based conceptualization of business model innovation: insights from an explorative study ”, R&D Management , Vol. 44 No. 5 , pp. 429 - 449 .

Michel , S. ( 2014 ), “ Capture more value ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 92 No. 4 , pp. 78 - 85 .

Morris , M.H. , Shirokova , G. and Shatalov , A. ( 2013 ), “ The business model and firm performance: the case of Russian food service ventures ”, Journal of Small Business Management , Vol. 51 No. 1 , pp. 46 - 65 .

Osterwalder , A. , Pigneur , Y. and Tucci , C.L. ( 2005 ), “ Clarifying business models: origins, present, and future of the concept ”, Communications of the Association for Information Systems , Vol. 16 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 25 .

Peters , C. , Blohm , I. and Leimeister , J.M. ( 2015 ), “ Anatomy of successful business models for complex services: insights from the telemedicine field ”, Journal of Management Information Systems , Vol. 32 No. 3 , pp. 75 - 104 .

Rajala , R. , Westerlund , M. and Möller , K. ( 2012 ), “ Strategic flexibility in open innovation – designing business models for open source software ”, European Journal of Marketing , Vol. 46 No. 10 , pp. 1368 - 1388 .

Roberge , M. ( 2015 ), “ The right way to use compensation: to shift strategy, change how you pay your team ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 93 No. 4 , pp. 70 - 75 .

Schneider , S. and Spieth , P. ( 2013 ), “ Business model innovation: towards an integrated future research agenda ”, International Journal of Innovation Management , Vol. 17 No. 1 , pp. 134 - 156 .

Shafer , S.M. , Smith , H.J. and Linder , J.C. ( 2005 ), “ The power of business models ”, Business Horizons , Vol. 48 No. 3 , pp. 199 - 207 .

Sinfield , J.V. , Calder , E. , McConnell , B. and Colson , S. ( 2012 ), “ How to identify new business models ”, MIT Sloan Management Review , Vol. 53 No. 2 , pp. 85 - 90 .

Sinkovics , N. , Sinkovics , R.R. and Yamin , M. ( 2014 ), “ The role of social value creation in business model formulation at the bottom of the pyramid – implications for MNEs? ”, International Business Review , Vol. 23 No. 4 , pp. 692 - 707 .

Spieth , P. , Schneckenberg , D. and Ricart , J.E. ( 2014 ), “ Business model innovation – state of the art and future challenges for the field ”, R&D Management , Vol. 44 No. 3 , pp. 237 - 247 .

Sorescu , A. , Frambach , R.T. , Singh , J. , Rangaswamy , A. and Bridges , C. ( 2011 ), “ Innovations in retail business models ”, Journal of Retailing , Vol. 87 No. 1 , pp. S3 - S16 .

Sosna , M. , Trevinyo-Rodríguez , R.N. and Velamuri , S.R. ( 2010 ), “ Business model innovation through trial-and-error learning: the naturhouse case ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 43 Nos. 2-3 , pp. 383 - 407 .

Storbacka , K. ( 2011 ), “ A solution business model: capabilities and management practices for integrated solutions ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 40 No. 5 , pp. 699 - 711 .

Taran , Y. , Boer , H. and Lindgren , P. ( 2015 ), “ A business model innovation typology ”, Decision Sciences , Vol. 46 No. 2 , pp. 301 - 331 .

Transfield , D. , Denyer , D. and Smart , P. ( 2003 ), “ Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review ”, British Journal of Management , Vol. 14 No. 3 , pp. 207 - 222 .

Teece , D.J. ( 2010 ), “ Business models, business strategy and innovation ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 43 Nos 2-3 , pp. 172 - 194 .

Velu , C. ( 2015 ), “ Business model innovation and third-party alliance on the survival of new firms ”, Technovation , Vol. 35 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 11 .

Velu , C. ( 2016 ), “ Evolutionary or revolutionary business model innovation through coopetition? The role of dominance in network markets ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 53 No. 1 , pp. 124 - 135 .

Velu , C. and Jacob , A. ( 2014 ), “ Business model innovation and owner–managers: the moderating role of competition ”, R&D Management , Vol. 46 No. 3 , pp. 451 - 463 .

Visnjic , I. , Wiengarten , F. and Neely , A. ( 2016 ), “ Only the brave: product innovation, service business model innovation, and their impact on performance ”, Journal of Product Innovation Management , Vol. 33 No. 1 , pp. 36 - 52 .

Weill , P. and Woerner , S.L. ( 2013 ), “ Optimizing your digital business model ”, MIT Sloan Management Review , Vol. 54 No. 3 , pp. 71 - 78 .

Wilson , F. and Post , J.E. ( 2013 ), “ Business models for people, planet (& profits): exploring the phenomena of social business, a market-based approach to social value creation ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 40 No. 3 , pp. 715 - 737 .

Wirtz , B.W. , Pistoia , A. , Ullrich , S. and Göttel , V. ( 2016 ), “ Business models: origin, development and future research perspectives ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 49 No. 1 , pp. 36 - 54 .

Wu , X. , Ma , R. and Shi , Y. ( 2010 ), “ How do latecomer firms capture value from disruptive technologies? A secondary business-model innovation perspective ”, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management , Vol. 57 No. 1 , pp. 51 - 62 .

Yunus , M. , Moingeon , B. and Lehmann-Ortega , L. ( 2010 ), “ Building social business models: lessons from the grameen experience ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 43 Nos 2-3 , pp. 308 - 325 .

Zott , C. and Amit , R. ( 2010 ), “ Business model design: an activity system perspective ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 43 Nos 2-3 , pp. 216 - 226 .

Zott , C. , Amit , R. and Massa , L. ( 2011 ), “ The business model: recent developments and future research ”, Journal of Management , Vol. 37 No. 4 , pp. 1019 - 1042 .

Further reading

Weill , P. , Malone , T.W. and Apel , T.G. ( 2011 ), “ The business models investors prefer ”, MIT Sloan Management Review , Vol. 52 No. 4 , pp. 17 - 19 .

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.9(6); 2023 Jun

- PMC10220359

Business model innovation and firm performance: Evidence from manufacturing SMEs

Natnael salfore.

a University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

Matiwos Ensermu

b Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Zerihun Kinde

Associated data.

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

In the current volatile business environment, companies are obliged to search for new ways of doing business to remain competitive. Accordingly, firms innovate their business model as it became a promising strategy to achieve sustainable outcomes. However, there is still a need for empirical studies that examine the relationship between business model innovation (BMI) and the performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In this study, we aimed to investigate this relationship by collecting data from 264 manufacturing SMEs through structured questionnaires. We employed partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to analyze the collected data and test the hypotheses. The results indicated that changes in any component of the business model, namely value creation, value proposition, or value capture, had a positive and significant relationship with the performance of manufacturing SMEs. Therefore, by innovating their business models, firms can create more value for their customers while capturing value for themselves. In conclusion, increasing use value or decreasing exchange value with customers will help firms create more value and surpass competitors in the marketplace, while also allowing them to capture more value for themselves.

1. Introduction

In the current volatile environment, companies are obliged to rethink and search for unique strategies and innovative ways of doing business to improve their performance [ 1 ] and remain competitive [ 2 ]. For this purpose, firms often make significant efforts to innovate their products and processes to increase their revenue and maintain and/or improve their profit level [ 3 ].

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines innovation broadly as “the introduction of a new or significantly improved product (good or service) or process, new marketing method or a new organizational method in business practice, workplace organization, or external relations” [ 4 ]. However, innovations in products and processes are insufficient to compete in the current market where technology development, globalization, ease of access to information, and development in the world economy are high [ 5 , 6 ]. In addition, innovations to improve products and processes are often costly and time-consuming, require high investment in research and development, and require new equipment and even entirely new business units whose future pay-back is uncertain [ 3 , 5 ]. For these purposes, most firms are now turning to Business Model Innovation (BMI) as an alternative or even complement to product or process innovation, as BMI goes beyond just innovating products, services, or technology that can be easily replicated [ 3 , 7 ].

The business model, which describes how a firm creates, delivers, and captures value [ 8 ], should be either slightly modified or completely changed in response to the changing conditions and strengthened over time as the competitive environment evolves [ 9 ]. Thus, BMI is defined as “the conscious change of an existing business model or the creation of a new business model that better satisfies the needs of the customer than the existing business model” [ 10 , 11 ]. Currently, interest in BMI, and business models in general, is increasing in both practice and research [ 12 , 13 ]. In a global study conducted by the Economic Intelligence Unit (EIU), the majority of senior managers stated they prefer to innovate business models over product and process innovations [ 3 ]. As such, BMI has recently received great attention from scholars and academicians in various fields of study [ 13 , 14 ].

However, empirical research linking BMI to other factors in firms is still scarce and dispersed across different disciplines [ 12 , 15 ]. Most previous studies have primarily focused on defining and explaining the concept and differentiating it from other management concepts [ 11 , 16 ]. Furthermore, empirical studies in this area have yielded conflicting results. While some studies have found a positive relationship between BMI and firm performance [ 12 , 17 ], others have found a negative [ 18 , 19 ], or non-significant relationship between the two [ 20 ]. Despite limited research indicating the relationship between BMI and firm performance, the question of whether changing the business model results in a change in firm performance remains unanswered [ 12 , 13 ]. Moreover, answering this question is very important for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) engaged in manufacturing, as they have fewer resources and capabilities than large firms [ 17 ]. Therefore, given the importance of SMEs in the global economy, empirical research is needed to ascertain whether BMI activity in manufacturing SMEs is associated with improved performance [ 12 , 17 ]. This could be achieved through large-scale empirical investigations of the relationship between BMI and firm performance, utilizing statistical methodologies that ensure greater generalizability of results, as recommended by scholars [ 11 , 21 ].

Therefore, the objective of the current study is to empirically investigate the relationship between BMI and the performance of manufacturing SMEs. By doing so, first, the study broadens the scope of business model research, which has previously focused on defining and differentiating the concept from other concepts and identifying its drivers and antecedents [ 8 , 12 , 16 ]. Second, previous studies in the area have relied on qualitative data and are characterized by an explorative approach to gain a first-hand understanding of the concept [ 11 ]. Furthermore, some empirical studies have made use of secondary data collected for other purposes [ 12 , 22 ]. In contrast, the current study utilizes statistical methods and quantitative data analysis, thereby providing methodological contributions to the existing literature.

The subsequent sections of this paper are organized as follows. Section 2 provides a review of the empirical literature and hypothesis development. Section 3 outlines the methods and materials used in this study. Section 4 presents the results, while Section 5 discusses the implications of the findings with concluding remarks. Finally, Section 6 discusses the implications, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Empirical review and hypothesis development

2.1. business model and business model innovation.

The concept of business model has gained widespread acceptance in corporate practice and high visibility in strategic and entrepreneurship research [ 16 , 23 ]. There is no single widely accepted definition of a business model because the literature develops in silos based on the interests of respective researchers [ 5 , 16 ]. Amit and Zott [ 24 ] define the business model as “the content, structure, and governance of transactions designed so as to create value through the exploitation of business opportunities.” Chesbrough and Rosenbloom [ 25 ] describe the same as “the heuristic logic that connects technical potential with the realization of economic value.” While the concept and definition of a business model differ, various scholars have conceptualized it based on its basic dimensions and agree that its main purpose is to create and deliver value to customers and enterprises themselves [ 6 , 8 ]. In this study, we adopt Teece’s [ 8 ] definition of a business model, which portrays it as “the design or architecture of the value creation, delivery, and capture mechanisms of an organization.”

The first basic element of the business model, value creation, refers to the tasks a firm performs to provide an offer to customers by using its resources and capabilities [ 14 ]. It also indicates the firm’s ability to acquire resources, such as land, capital, and labor, and transform them into products and services [ 6 ]. Value can be created by either increasing the customers' willingness to pay or decreasing the suppliers' and partners' opportunity costs [ 26 ]. On the other hand, the value proposition dimension indicates the company’s bundle of products and services that are of value to customers and the way in which they are offered [ 6 , 14 ]. It also explains how a particular firm differentiates itself from its competitors and the reason why customers buy from that firm rather than others [ 6 ]. Finally, the value capture dimension defines how value offerings are converted into revenue streams and then captured as profits by firms [ 14 ]. According to Chesbrough [ 5 ], the value capture dimension is equally critical to a firm’s success because a company that cannot profit from some of its activities cannot sustain those activities over time.

The business model requires constant vigilance because it cannot be static and last forever by efficiently unlocking, capturing, and redistributing the value added by organizations [ 8 , 15 ]. As a result, it must be either slightly modified or completely changed in response to the changing environmental conditions and strengthened over time [ 9 ]. Thus, BMI is defined as “the discovery of new or conscious change of enterprise’s existing value creation, delivery, and/or capture mechanism that better satisfies customer needs than the existing business model” [ 8 , 10 ].

The concept of a business model is fundamentally linked to technological innovation. For this purpose, different scholars have put forth various perspectives on the interaction between business models and technology. While some argue that developments in technology facilitate new business models [ 5 , 13 , 27 ], others argue that the emergence of business models pushed for the development of new technologies [ 9 ]. However, they all stated unequivocally that innovation in the business model is distinct from innovation in technology. According to Baden-Fuller and Haefliger [ 27 ], the business model is essentially separable from technological innovation, even though there exists a fundamental linkage between the two. In addition, Chesbrough [ 5 ] clearly indicated that innovation in the business model is not the same as innovation in technology. In his words, “better business model often will beat a better technology.” In a later study, Chesbrough [ 28 ] pointed out that companies commercialize their technologies through business models. Otherwise, the economic value of technology remains latent until firms introduce it through a business model. Therefore, firms should innovate their business models in order to reap the outcomes of technological innovations.

2.2. Firm performance

Currently, firm performance has become a relevant concept and ultimate outcome variable in any management research [ 29 ]. Despite its prevalence in the academic literature, there is less consensus about its definition and measurement among researchers [ 30 ]. After the seminal work of Venkatraman and Ramanujam [ 31 ], scholars have started to recognize and measure firm performance as a multidimensional construct [ 29 , 32 ]. Nevertheless, while acknowledging its multidimensionality, several other researchers measure firm performance as unidimensional [ 32 ].

One can measure firm performance objectively (through accounting and financial measures) or subjectively (via survey-based self-reports) [ 30 ]. While objective measures are preferable over subjective measures, objective indicators on the performance of SMEs are difficult to collect [ 30 , 32 ] and, in some cases, impossible to collect [ 31 ]. Singh et al. [ 30 ] also indicated that obtaining consistent and comparable data in the objective measures of performance for the entire sample under investigation is extremely difficult. Furthermore, most owners are not willing to disclose information regarding objective performance measures [ 33 ]. For these purposes, several studies adopt subjective perception-based measures of firm performance [ 30 , 32 , 33 ]. However, whether objective or subjective measures of performance are used is up to the researcher [ 30 ].

2.3. The relationship between BMI and firm performance

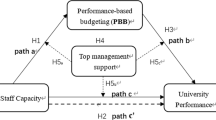

There is increasing consensus among scholars regarding the relationship between BMI and firm performance [ 16 ]. According to Pohle and Chapman [ 34 ], BMI is responsible for a significantly larger improvement in the firm’s performance than innovation in product and process. In addition, the authors stressed that BMI is often positively related to reduced costs and, thus, enhanced profits for manufacturers. Teece [ 8 ] also indicated that a well-designed business model that includes all aspects (components), along with the implementation and refinement of commercially feasible revenue and cost architectures, is critical to enterprise success. Furthermore, Cucculelli and Bettinelli [ 22 ] pointed out that modifying a firm’s business model in an innovative way is positively associated with venture performance. In the same way, scholars who conceptualized business models based on their components reported a positive relationship with firm performance. For instance, Clauss et al. [ 35 ] found that innovation in value creation increases firm performance by delivering greater economic results. Similarly, a study by Chen et al. [ 17 ] in manufacturing SMEs indicated that value creation innovation is positively and significantly related to SMEs' performance. Therefore,

Value creation innovation is positively related to the performance of manufacturing SMEs.

Innovation in the value proposition helps firms to extend their product and service portfolios and address new market needs, which in turn is highly associated with their performance [ 35 ]. According to Clauss et al. [ 35 ], a change in value proposition will result in a change in customer offerings, which includes product/service, target markets, and delivery channels. Clauss et al. [ 36 ] also indicated that value proposition innovation has a positive relationship with firm performance. Furthermore, Chen et al. [ 17 ] found that value proposition innovation is positively and significantly associated with manufacturing SMEs' performance. Therefore,

Value proposition innovation is positively associated with the performance of manufacturing SMEs.

Renewing the value capture mechanism can help firms replace less profitable revenue sources and improve their potential profits [ 26 ]. Casadesus-Masanell and Zhu [ 10 ] also indicated that innovations in value capture help firms to realize new revenue streams in addition to existing ones, or to substitute less profitable ones compared to other revenue capture mechanisms, which improves the prospects for future revenue. The authors also emphasized that value capture innovation can reduce inefficiencies and, as a result, improve firms' performance. Therefore,

Value capture innovation is positively related to the performance of manufacturing SMEs.

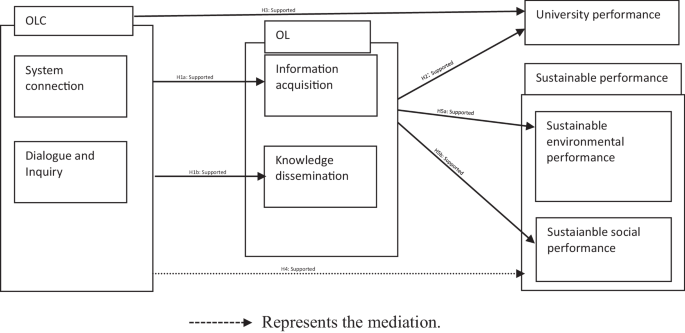

The overall structure of the relationship between the study variables and firm performance is indicated in Fig. 1 .

Conceptual framework.

3. Methods and materials

3.1. sample and data.

The aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between BMI and manufacturing SMEs' performance. To achieve this, we used primary data collected from SMEs located in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. At the time of survey (between May and October 2022), there were 1201 small and 602 medium-sized manufacturing enterprises. We proportionally and randomly selected 318 manufacturing SMEs to include in the study sample to ensure that each sector received fair representation. We excluded startups from the study as they don’t have a fully developed business model and lack adequate capital to move on to the next phase [ 33 ]. We collected 276 questionnaires, with eight having limited data. Therefore, we analyzed 264 correct responses. Out of correct responses, 173 were small and 91 were medium-sized enterprises. In Ethiopia, small enterprises have a total capital ranging from Birr 100,001 † to Birr 1,500,000 and employ 6 to 30 workers, including the owner, family members, and other employees. Medium enterprises have a total capital (excluding building) ranging from Birr 1,500,001 to Birr 20,000,000 and employ 31 to 100 workers, including the owner, family members, and other employees (Federal Urban Job Creation and Food Security Agency [FUJCFSA], 2019). The data also showed that 96 enterprises were engaged in wood and steel work, 91 in textile and leather manufacturing, 48 in agro-processing, and the remaining 29 were engaged in the manufacturing of chemicals and industrial inputs. The classification of manufacturing SMEs into sub-sectors in this study was based on the Ethiopian government’s classification system.

We collected data from owners/managers of SMEs using structured questionnaires. Before collecting data, we obtained informed consent from all participants involved in our research. The consent form outlined the purpose of the study and the fact that all data collected would be kept confidential and used solely for academic purposes. We administered the questionnaire on-site to owners/managers of each enterprise. The questionnaire had four sections: background information, BMI, environmental dynamism, and firm performance. The background information section included gender, the respondents' role in the enterprise, educational level, enterprise age, manufacturing sub-sector, and the number of employees. We collected BMI data using an instrument developed by Clauss [ 14 ]. The instrument has 30 Likert-scaled items in which 10 items measure value creation innovation, 12 measure value proposition innovation, and the remaining 8 measure value capture innovation (see Appendix 1 ). Each item ranges from a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The first-order constructs in the measurement scale consist of new capabilities, which can be developed through training and knowledge integration; new technology, which is related to equipment used to carry out BMI; new processes, which are concerned with how activities are connected; new partnerships, which represent external resources available to the firm; new offerings, which justify the firm’s product offerings; new markets, which identify the customer group in which the product is offered; new channels, which are concerned with the delivery of value to customers; new relationships, which indicate the firm’s ability to build or establish a relationship with customers; new revenue models, which are concerned with transforming revenue models to encourage customers to pay for the value proposition; and new cost structures, which are related to the direct and indirect costs of running the business [ 14 ]. We collected data on performance of SMEs by using financial and marketing indicators such as sales growth, profit growth, market share, speed to market, net income, and return on investment, as recommended by Venkatraman and Ramanujam [ 31 ], and we measured them using a Likert-type scale, with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

3.2. Measurement of variables

The study primarily includes two variables: BMI and firm performance, which are predictor and outcome variables, respectively. BMI is concerned with changes in one or more components of the business model, such as value creation, value proposition, and value capture [ 14 ]. Firm performance encompasses both financial and non-financial measures [ 31 ].

Previous studies have used different measurement scales to measure BMI. For instance, Velu [ 37 ] used diversification/product launch and external funding as two indicators of BMI while Anwar [ 38 ] utilized six items developed by Karimi and Walter that focused on different aspects of a firm’s innovativeness, such as product and service, delivery, process, and structure. On the other hand, Clauss [ 14 ] developed and validated a BMI measurement scale, which Bouwman et al. [ 12 ] identified as a valuable contribution to measuring BMI. As a result, we measured BMI by assessing the changes introduced in the three dimensions of the business model: value creation, value proposition, and value capture. To capture the multi-dimensional nature of BMI, we used a reflective-formative measurement model and estimated hierarchical latent variables: value creation innovation, value proposition innovation, and value capture innovation using a two-stage approach in PLS-SEM, which has advantages over other methods [ 39 ].