Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to write a dbq essay: key strategies and tips.

Advanced Placement (AP)

The DBQ, or document-based-question, is a somewhat unusually-formatted timed essay on the AP History Exams: AP US History, AP European History, and AP World History. Because of its unfamiliarity, many students are at a loss as to how to even prepare, let alone how to write a successful DBQ essay on test day.

Never fear! I, the DBQ wizard and master, have a wealth of preparation strategies for you, as well as advice on how to cram everything you need to cover into your limited DBQ writing time on exam day. When you're done reading this guide, you'll know exactly how to write a DBQ.

For a general overview of the DBQ—what it is, its purpose, its format, etc.—see my article "What is a DBQ?"

Table of Contents

What Should My Study Timeline Be?

Preparing for the DBQ

Establish a Baseline

Foundational Skills

Rubric Breakdown

Take Another Practice DBQ

How Can I Succeed on Test Day?

Reading the Question and Documents

Planning Your Essay

Writing Your Essay

Key Takeaways

What Should My DBQ Study Timeline Be?

Your AP exam study timeline depends on a few things. First, how much time you have to study per week, and how many hours you want to study in total? If you don't have much time per week, start a little earlier; if you will be able to devote a substantial amount of time per week (10-15 hours) to prep, you can wait until later in the year.

One thing to keep in mind, though, is that the earlier you start studying for your AP test, the less material you will have covered in class. Make sure you continually review older material as the school year goes on to keep things fresh in your mind, but in terms of DBQ prep it probably doesn't make sense to start before February or January at the absolute earliest.

Another factor is how much you need to work on. I recommend you complete a baseline DBQ around early February to see where you need to focus your efforts.

If, for example, you got a six out of seven and missed one point for doing further document analysis, you won't need to spend too much time studying how to write a DBQ. Maybe just do a document analysis exercise every few weeks and check in a couple months later with another timed practice DBQ to make sure you've got it.

However, if you got a two or three out of seven, you'll know you have more work to do, and you'll probably want to devote at least an hour or two every week to honing your skills.

The general flow of your preparation should be: take a practice DBQ, do focused skills practice, take another practice DBQ, do focused skills practice, take another practice DBQ, and so on. How often you take the practice DBQs and how many times you repeat the cycle really depends on how much preparation you need, and how often you want to check your progress. Take practice DBQs often enough that the format stays familiar, but not so much that you've done barely any skills practice in between.

He's ready to start studying!

The general preparation process is to diagnose, practice, test, and repeat. First, you'll figure out what you need to work on by establishing a baseline level for your DBQ skills. Then, you'll practice building skills. Finally, you'll take another DBQ to see how you've improved and what you still need to work on.

In this next section, I'll go over the whole process. First, I'll give guidance on how to establish a baseline. Then I'll go over some basic, foundational essay-writing skills and how to build them. After that I'll break down the DBQ rubric. You'll be acing practice DBQs before you know it!

#1: Establish a Baseline

The first thing you need to do is to establish a baseline— figure out where you are at with respect to your DBQ skills. This will let you know where you need to focus your preparation efforts.

To do this, you will take a timed, practice DBQ and have a trusted teacher or advisor grade it according to the appropriate rubric.

AP US History

For the AP US History DBQ, you'll be given a 15-minute reading period and 45 minutes of writing time.

A selection of practice questions from the exam can be found online at the College Board, including a DBQ. (Go to page 136 in the linked document for the practice prompt.)

If you've already seen this practice question, perhaps in class, you might use the 2015 DBQ question .

Other available College Board DBQs are going to be in the old format (find them in the "Free-Response Questions" documents). This is fine if you need to use them, but be sure to use the new rubric (which is out of seven points, rather than nine) to grade.

I advise you to save all these links , or even download all the Free Response Questions and the Scoring Guides, for reference because you will be using them again and again for practice.

AP European History

The College Board has provided practice questions for the exam , including a DBQ (see page 200 in the linked document).

If you've already seen this question, the only other questions available through the College Board are in the old format, because the 2016 DBQ is in a new, seven-point format identical to the AP US History exam. Just be sure to use the new DBQ rubric if you want to use any of the old prompts provided by the College Board . (DBQs are in the documents titled "Free-Response Questions.")

I advise you to save all these links (or even download all the Free Response Questions and the Scoring Guides) for reference, because you will be using them again and again for practice.

Who knows—maybe this will be one of your documents!

AP World History

For this exam, you'll be given a 15-minute reading period and 45 minutes of writing time . As for the other two history exams, the College Board has provided practice questions . See page 166 for the DBQ.

If you've already seen this question, the only other questions available through the College Board are in the old format, because the 2017 World History DBQ is in a new, seven-point format identical to the AP US History and AP European History exams. So be sure to use the new DBQ rubric if you want to use any of the old prompts provided by the College Board . (DBQs are in the documents titled "Free-Response Questions.")

Finding a Trusted Advisor to Look at Your Papers

A history teacher would be a great resource, but if they are not available to you in this capacity, here are some other ideas:

- An English teacher.

- Ask a librarian at your school or public library! If they can't help you, they may be able to direct you to resources who can.

- You could also ask a school guidance counselor to direct you to in-school resources you could use.

- A tutor. This is especially helpful if they are familiar with the test, although even if they aren't, they can still advise—the DBQ is mostly testing academic writing skills under pressure.

- Your parent(s)! Again, ideally your trusted advisor will be familiar with the AP, but if you have used your parents for writing help in the past they can also assist here.

- You might try an older friend who has already taken the exam and did well...although bear in mind that some people are better at doing than scoring and/or explaining!

Can I Prepare For My Baseline?

If you know nothing about the DBQ and you'd like to do a little basic familiarization before you establish your baseline, that's completely fine. There's no point in taking a practice exam if you are going to panic and muddle your way through it; it won't give a useful picture of your skills.

For a basic orientation, check out my article for a basic introduction to the DBQ including DBQ format.

If you want to look at one or two sample essays, see my article for a list of DBQ example essay resources . Keep in mind that you should use a fresh prompt you haven't seen to establish your baseline, though, so if you do look at samples don't use those prompts to set your baseline.

I would also check out this page about the various "task" words associated with AP essay questions . This page was created primarily for the AP European History Long Essay question, but the definitions are still useful for the DBQ on all the history exams, particularly since these are the definitions provided by the College Board.

Once you feel oriented, take your practice exam!

Don't worry if you don't do well on your first practice! That's what studying is for. The point of establishing a baseline is not to make you feel bad, but to empower you to focus your efforts on the areas you need to work on. Even if you need to work on all the areas, that is completely fine and doable! Every skill you need for the DBQ can be built .

In the following section, we'll go over these skills and how to build them for each exam.

You need a stronger foundation than this sand castle.

#2: Develop Foundational Skills

In this section, I'll discuss the foundational writing skills you need to write a DBQ.

I'll start with some general information on crafting an effective thesis , since this is a skill you will need for any DBQ exam (and for your entire academic life). Then, I'll go over outlining essays, with some sample outline ideas for the DBQ. After I'll touch on time management. Finally, I'll briefly discuss how to non-awkwardly integrate information from your documents into your writing.

It sounds like a lot, but not only are these skills vital to your academic career in general, you probably already have the basic building blocks to master them in your arsenal!

Writing An Effective Thesis

Writing a good thesis is a skill you will need to develop for all your DBQs, and for any essay you write, on the AP or otherwise.

Here are some general rules as to what makes a good thesis:

A good thesis does more than just restate the prompt.

Let's say our class prompt is: "Analyze the primary factors that led to the French Revolution."

Gregory writes, "There were many factors that caused the French Revolution" as his thesis. This is not an effective thesis. All it does is vaguely restate the prompt.

A good thesis makes a plausible claim that you can defend in an essay-length piece of writing.

Maybe Karen writes, "Marie Antoinette caused the French Revolution when she said ‘Let them eat cake' because it made people mad."

This is not an effective thesis, either. For one thing, Marie Antoinette never said that. More importantly, how are you going to write an entire essay on how one offhand comment by Marie Antoinette caused the entire Revolution? This is both implausible and overly simplistic.

A good thesis answers the question .

If LaToya writes, "The Reign of Terror led to the ultimate demise of the French Revolution and ultimately paved the way for Napoleon Bonaparte to seize control of France," she may be making a reasonable, defensible claim, but it doesn't answer the question, which is not about what happened after the Revolution, but what caused it!

A good thesis makes it clear where you are going in your essay.

Let's say Juan writes, "The French Revolution, while caused by a variety of political, social, and economic factors, was primarily incited by the emergence of the highly educated Bourgeois class." This thesis provides a mini-roadmap for the entire essay, laying out that Juan is going to discuss the political, social, and economic factors that led to the Revolution, in that order, and that he will argue that the members of the Bourgeois class were the ultimate inciters of the Revolution.

This is a great thesis! It answers the question, makes an overarching point, and provides a clear idea of what the writer is going to discuss in the essay.

To review: a good thesis makes a claim, responds to the prompt, and lays out what you will discuss in your essay.

If you feel like you have trouble telling the difference between a good thesis and a not-so-good one, here are a few resources you can consult:

This site from SUNY Empire has an exercise in choosing the best thesis from several options. It's meant for research papers, but the general rules as to what makes a good thesis apply.

About.com has another exercise in choosing thesis statements specifically for short essays. Note, however, that most of the correct answers here would be "good" thesis statements as opposed to "super" thesis statements.

- This guide from the University of Iowa provides some really helpful tips on writing a thesis for a history paper.

So how do you practice your thesis statement skills for the DBQ?

While you should definitely practice looking at DBQ questions and documents and writing a thesis in response to those, you may also find it useful to write some practice thesis statements in response to the Free-Response Questions. While you won't be taking any documents into account in your argument for the Free-Response Questions, it's good practice on how to construct an effective thesis in general.

You could even try writing multiple thesis statements in response to the same prompt! It is a great exercise to see how you could approach the prompt from different angles. Time yourself for 5-10 minutes to mimic the time pressure of the AP exam.

If possible, have a trusted advisor or friend look over your practice statements and give you feedback. Barring that, looking over the scoring guidelines for old prompts (accessible from the same page on the College Board where past free-response questions can be found) will provide you with useful tips on what might make a good thesis in response to a given prompt.

Once you can write a thesis, you need to be able to support it—that's where outlining comes in!

This is not a good outline.

Outlining and Formatting Your Essay

You may be the greatest document analyst and thesis-writer in the world, but if you don't know how to put it all together in a DBQ essay outline, you won't be able to write a cohesive, high-scoring essay on test day.

A good outline will clearly lay out your thesis and how you are going to support that thesis in your body paragraphs. It will keep your writing organized and prevent you from forgetting anything you want to mention!

For some general tips on writing outlines, this page from Roane State has some useful information. While the general principles of outlining an essay hold, the DBQ format is going to have its own unique outlining considerations.To that end, I've provided some brief sample outlines that will help you hit all the important points.

Sample DBQ Outline

- Introduction

- Thesis. The most important part of your intro!

- Body 1 - contextual information

- Any outside historical/contextual information

- Body 2 - First point

- Documents & analysis that support the first point

- If three body paragraphs: use about three documents, do deeper analysis on two

- Body 3 - Second point

- Documents & analysis that support the second point

- Use about three documents, do deeper analysis on two

- Be sure to mention your outside example if you have not done so yet!

- Body 4 (optional) - Third point

- Documents and analysis that support third point

- Re-state thesis

- Draw a comparison to another time period or situation (synthesis)

Depending on your number of body paragraphs and your main points, you may include different numbers of documents in each paragraph, or switch around where you place your contextual information, your outside example, or your synthesis.

There's no one right way to outline, just so long as each of your body paragraphs has a clear point that you support with documents, and you remember to do a deeper analysis on four documents, bring in outside historical information, and make a comparison to another historical situation or time (you will see these last points further explained in the rubric breakdown).

Of course, all the organizational skills in the world won't help you if you can't write your entire essay in the time allotted. The next section will cover time management skills.

You can be as organized as this library!

Time Management Skills for Essay Writing

Do you know all of your essay-writing skills, but just can't get a DBQ essay together in a 15-minute planning period and 40 minutes of writing?

There could be a few things at play here:

Do you find yourself spending a lot of time staring at a blank paper?

If you feel like you don't know where to start, spend one-two minutes brainstorming as soon as you read the question and the documents. Write anything here—don't censor yourself. No one will look at those notes but you!

After you've brainstormed for a bit, try to organize those thoughts into a thesis, and then into body paragraphs. It's better to start working and change things around than to waste time agonizing that you don't know the perfect thing to say.

Are you too anxious to start writing, or does anxiety distract you in the middle of your writing time? Do you just feel overwhelmed?

Sounds like test anxiety. Lots of people have this. (Including me! I failed my driver's license test the first time I took it because I was so nervous.)

You might talk to a guidance counselor about your anxiety. They will be able to provide advice and direct you to resources you can use.

There are also some valuable test anxiety resources online: try our guide to mindfulness (it's focused on the SAT, but the same concepts apply on any high-pressure test) and check out tips from Minnesota State University , these strategies from TeensHealth , or this plan for reducing anxiety from West Virginia University.

Are you only two thirds of the way through your essay when 40 minutes have passed?

You are probably spending too long on your outline, biting off more than you can chew, or both.

If you find yourself spending 20+ minutes outlining, you need to practice bringing down your outline time. Remember, an outline is just a guide for your essay—it is fine to switch things around as you are writing. It doesn't need to be perfect. To cut down on your outline time, practice just outlining for shorter and shorter time intervals. When you can write one in 20 minutes, bring it down to 18, then down to 16.

You may also be trying to cover too much in your paper. If you have five body paragraphs, you need to scale things back to three. If you are spending twenty minutes writing two paragraphs of contextual information, you need to trim it down to a few relevant sentences. Be mindful of where you are spending a lot of time, and target those areas.

You don't know the problem —you just can't get it done!

If you can't exactly pinpoint what's taking you so long, I advise you to simply practice writing DBQs in less and less time. Start with 20 minutes for your outline and 50 for your essay, (or longer, if you need). Then when you can do it in 20 and 50, move back to 18 minutes and 45 for writing, then to 15 and 40.

You absolutely can learn to manage your time effectively so that you can write a great DBQ in the time allotted. On to the next skill!

Integrating Citations

The final skill that isn't explicitly covered in the rubric, but will make a big difference in your essay quality, is integrating document citations into your essay. In other words, how do you reference the information in the documents in a clear, non-awkward way?

It is usually better to use the author or title of the document to identify a document instead of writing "Document A." So instead of writing "Document A describes the riot as...," you might say, "In Sven Svenson's description of the riot…"

When you quote a document directly without otherwise identifying it, you may want to include a parenthetical citation. For example, you might write, "The strikers were described as ‘valiant and true' by the working class citizens of the city (Document E)."

Now that we've reviewed the essential, foundational skills of the DBQ, I'll move into the rubric breakdowns. We'll discuss each skill the AP graders will be looking for when they score your exam. All of the history exams share a DBQ rubric, so the guidelines are identical.

Don't worry, you won't need a magnifying glass to examine the rubric.

#3: Learn the DBQ Rubric

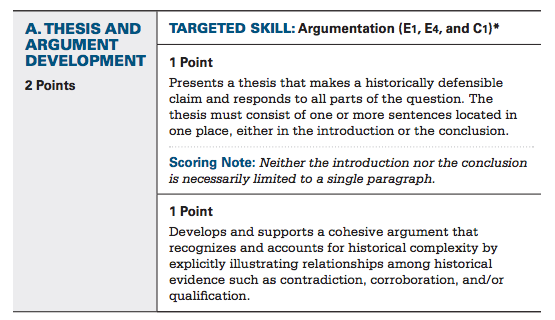

The DBQ rubric has four sections for a total of seven points.

Part A: Thesis - 2 Points

One point is for having a thesis that works and is historically defensible. This just means that your thesis can be reasonably supported by the documents and historical fact. So please don't make the main point of your essay that JFK was a member of the Illuminati or that Pope Urban II was an alien.

Per the College Board, your thesis needs to be located in your introduction or your conclusion. You've probably been taught to place your thesis in your intro, so stick with what you're used to. Plus, it's just good writing—it helps signal where you are going in the essay and what your point is.

You can receive another point for having a super thesis.

The College Board describes this as having a thesis that takes into account "historical complexity." Historical complexity is really just the idea that historical evidence does not always agree about everything, and that there are reasons for agreement, disagreement, etc.

How will you know whether the historical evidence agrees or disagrees? The documents! Suppose you are responding to a prompt about women's suffrage (suffrage is the right to vote, for those of you who haven't gotten to that unit in class yet):

"Analyze the responses to the women's suffrage movement in the United States."

Included among your documents, you have a letter from a suffragette passionately explaining why she feels women should have the vote, a copy of a suffragette's speech at a women's meeting, a letter from one congressman to another debating the pros and cons of suffrage, and a political cartoon displaying the death of society and the end of the ‘natural' order at the hands of female voters.

A simple but effective thesis might be something like,

"Though ultimately successful, the women's suffrage movement sharply divided the country between those who believed women's suffrage was unnatural and those who believed it was an inherent right of women."

This is good: it answers the question and clearly states the two responses to suffrage that are going to be analyzed in the essay.

A super thesis , however, would take the relationships between the documents (and the people behind the documents!) into account.

It might be something like,

"The dramatic contrast between those who responded in favor of women's suffrage and those who fought against it revealed a fundamental rift in American society centered on the role of women—whether women were ‘naturally' meant to be socially and civilly subordinate to men, or whether they were in fact equals."

This is a "super" thesis because it gets into the specifics of the relationship between historical factors and shows the broader picture —that is, what responses to women's suffrage revealed about the role of women in the United States overall.

It goes beyond just analyzing the specific issues to a "so what"? It doesn't just take a position about history, it tells the reader why they should care . In this case, our super thesis tells us that the reader should care about women's suffrage because the issue reveals a fundamental conflict in America over the position of women in society.

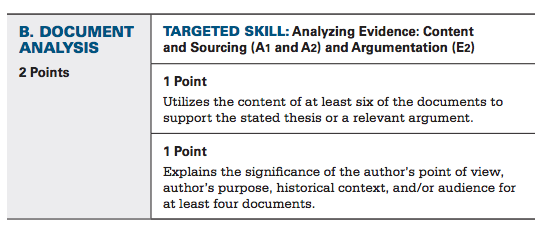

Part B: Document Analysis - 2 Points

One point for using six or seven of the documents in your essay to support your argument. Easy-peasy! However, make sure you aren't just summarizing documents in a list, but are tying them back to the main points of your paragraphs.

It's best to avoid writing things like, "Document A says X, and Document B says Y, and Document C says Z." Instead, you might write something like, "The anonymous author of Document C expresses his support and admiration for the suffragettes but also expresses fear that giving women the right to vote will lead to conflict in the home, highlighting the common fear that women's suffrage would lead to upheaval in women's traditional role in society."

Any summarizing should be connected a point. Essentially, any explanation of what a document says needs to be tied to a "so what?" If it's not clear to you why what you are writing about a document is related to your main point, it's not going to be clear to the AP grader.

You can get an additional point here for doing further analysis on 4 of the documents. This further analysis could be in any of these 4 areas:

Author's point of view - Why does the author think the way that they do? What is their position in society and how does this influence what they are saying?

Author's purpose - Why is the author writing what they are writing? What are they trying to convince their audience of?

Historical context - What broader historical facts are relevant to this document?

Audience - Who is the intended audience for this document? Who is the author addressing or trying to convince?

Be sure to tie any further analysis back to your main argument! And remember, you only have to do this for four documents for full credit, but it's fine to do it for more if you can.

Practicing Document Analysis

So how do you practice document analysis? By analyzing documents!

Luckily for AP test takers everywhere, New York State has an exam called the Regents Exam that has its own DBQ section. Before they write the essay, however, New York students have to answer short answer questions about the documents.

Answering Regents exam DBQ short-answer questions is good practice for basic document analysis. While most of the questions are pretty basic, it's a good warm-up in terms of thinking more deeply about the documents and how to use them. This set of Regent-style DBQs from the Teacher's Project are mostly about US History, but the practice could be good for other tests too.

This prompt from the Morningside center also has some good document comprehensions questions about a US-History based prompt.

Note: While the document short-answer questions are useful for thinking about basic document analysis, I wouldn't advise completing entire Regents exam DBQ essay prompts for practice, because the format and rubric are both somewhat different from the AP.

Your AP history textbook may also have documents with questions that you can use to practice. Flip around in there!

This otter is ready to swim in the waters of the DBQ.

When you want to do a deeper dive on the documents, you can also pull out those old College Board DBQ prompts.

Read the documents carefully. Write down everything that comes to your attention. Do further analysis—author's point of view, purpose, audience, and historical context—on all the documents for practice, even though you will only need to do additional analysis on four on test day. Of course, you might not be able to do all kinds of further analysis on things like maps and graphs, which is fine.

You might also try thinking about how you would arrange those observations in an argument, or even try writing a practice outline! This exercise would combine your thesis and document-analysis skills practice.

When you've analyzed everything you can possibly think of for all the documents, pull up the Scoring Guide for that prompt. It helpfully has an entire list of analysis points for each document.

Consider what they identified that you missed.

Do you seem way off-base in your interpretation? If so, how did it happen?

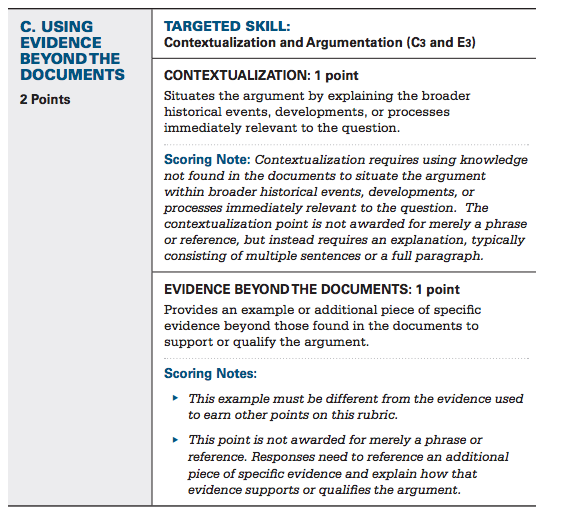

Part C: Using Evidence Beyond the Documents - 2 Points

Don't be freaked out by the fact that this is two points!

One point is just for context—if you can locate the issue within its broader historical situation. You do need to write several sentences to a paragraph about it, but don't stress; all you really need to know to be able to get this point is information about major historical trends over time, and you will need to know this anyways for the multiple choice section. If the question is about the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression, for example, be sure to include some of the general information you know about the Great Depression! Boom. Contextualized.

The other point is for naming a specific, relevant example in your essay that does not appear in the documents.

To practice your outside information skills, pull up your College Board prompts!

Read through the prompt and documents and then write down all of the contextualizing facts and as many specific examples as you can think of.

I advise timing yourself—maybe 5-10 minutes to read the documents and prompt and list your outside knowledge—to imitate the time pressure of the DBQ.

When you've exhausted your knowledge, make sure to fact-check your examples and your contextual information! You don't want to use incorrect information on test day.

If you can't remember any examples or contextual information about that topic, look some up! This will help fill in holes in your knowledge.

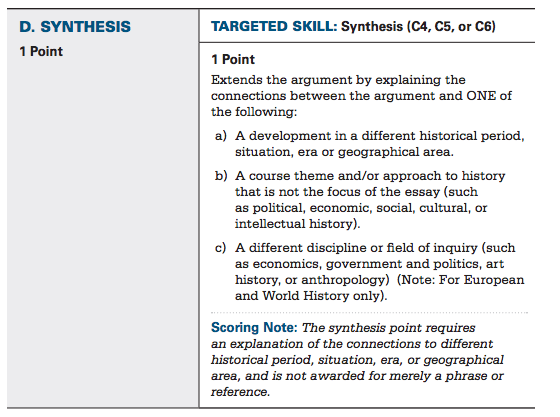

Part D: Synthesis - 1 Point

All you need to do for synthesis is relate your argument about this specific time period to a different time period, geographical area, historical movement, etc. It is probably easiest to do this in the conclusion of the essay. If your essay is about the Great Depression, you might relate it to the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

You do need to do more than just mention your synthesis connection. You need to make it meaningful. How are the two things you are comparing similar? What does one reveal about the other? Is there a key difference that highlights something important?

To practice your synthesis skills—you guessed it—pull up your College Board prompts!

- Read through the prompt and documents and then identify what historical connections you could make for your synthesis point. Be sure to write a few words on why the connection is significant!

- A great way to make sure that your synthesis connection makes sense is to explain it to someone else. If you explain what you think the connection is and they get it, you're probably on the right track.

- You can also look at sample responses and the scoring guide for the old prompts to see what other connections students and AP graders made.

That's a wrap on the rubric! Let's move on to skill-building strategy.

I know you're tired, but you can do it!

#5: Take Another Practice DBQ

So, you established a baseline, identified the skills you need to work on, and practiced writing a thesis statement and analyzing documents for hours. What now?

Take another timed, practice DBQ from a prompt you haven't seen before to check how you've improved. Recruit your same trusted advisor to grade your exam and give feedback. After, work on any skills that still need to be honed.

Repeat this process as necessary, until you are consistently scoring your goal score. Then you just need to make sure you maintain your skills until test day by doing an occasional practice DBQ.

Eventually, test day will come—read on for my DBQ-test-taking tips.

How Can I Succeed On DBQ Test Day?

Once you've prepped your brains out, you still have to take the test! I know, I know. But I've got some advice on how to make sure all of your hard work pays off on test day—both some general tips and some specific advice on how to write a DBQ.

#1: General Test-Taking Tips

Most of these are probably tips you've heard before, but they bear repeating:

Get a good night's sleep for the two nights preceding the exam. This will keep your memory sharp!

Eat a good breakfast (and lunch, if the exam is in the afternoon) before the exam with protein and whole grains. This will keep your blood sugar from crashing and making you tired during the exam.

Don't study the night before the exam if you can help it. Instead, do something relaxing. You've been preparing, and you will have an easier time on exam day if you aren't stressed from trying to cram the night before.

This dude knows he needs to get a good night's rest!

#2: DBQ Plan and Strategies

Below I've laid out how to use your time during the DBQ exam. I'll provide tips on reading the question and docs, planning your essay, and writing!

Be sure to keep an eye on the clock throughout so you can track your general progress.

Reading the Question and the Documents: 5-6 min

First thing's first: r ead the question carefully , two or even three times. You may want to circle the task words ("analyze," "describe," "evaluate," "compare") to make sure they stand out.

You could also quickly jot down some contextual information you already know before moving on to the documents, but if you can't remember any right then, move on to the docs and let them jog your memory.

It's fine to have a general idea of a thesis after you read the question, but if you don't, move on to the docs and let them guide you in the right direction.

Next, move on to the documents. Mark them as you read—circle things that seem important, jot thoughts and notes in the margins.

After you've passed over the documents once, you should choose the four documents you are going to analyze more deeply and read them again. You probably won't be analyzing the author's purpose for sources like maps and charts. Good choices are documents in which the author's social or political position and stake in the issue at hand are clear.

Get ready to go down the document rabbit hole.

Planning Your Essay: 9-11 min

Once you've read the question and you have preliminary notes on the documents, it's time to start working on a thesis. If you still aren't sure what to talk about, spend a minute or so brainstorming. Write down themes and concepts that seem important and create a thesis from those. Remember, your thesis needs to answer the question and make a claim!

When you've got a thesis, it's time to work on an outline . Once you've got some appropriate topics for your body paragraphs, use your notes on the documents to populate your outline. Which documents support which ideas? You don't need to use every little thought you had about the document when you read it, but you should be sure to use every document.

Here's three things to make sure of:

Make sure your outline notes where you are going to include your contextual information (often placed in the first body paragraph, but this is up to you), your specific example (likely in one of the body paragraphs), and your synthesis (the conclusion is a good place for this).

Make sure you've also integrated the four documents you are going to further analyze and how to analyze them.

Make sure you use all the documents! I can't stress this enough. Take a quick pass over your outline and the docs and make sure all of the docs appear in your outline.

If you go over the planning time a couple of minutes, it's not the end of the world. This probably just means you have a really thorough outline! But be ready to write pretty fast.

Writing the Essay - 45 min

If you have a good outline, the hard part is out of the way! You just need to make sure you get all of your great ideas down in the test booklet.

Don't get too bogged down in writing a super-exciting introduction. You won't get points for it, so trying to be fancy will just waste time. Spend maybe one or two sentences introducing the issue, then get right to your thesis.

For your body paragraphs, make sure your topic sentences clearly state the point of the paragraph . Then you can get right into your evidence and your document analysis.

As you write, make sure to keep an eye on the time. You want to be a little more than halfway through at the 20-minute mark of the writing period, so you have a couple minutes to go back and edit your essay at the end.

Keep in mind that it's more important to clearly lay out your argument than to use flowery language. Sentences that are shorter and to the point are completely fine.

If you are short on time, the conclusion is the least important part of your essay . Even just one sentence to wrap things up is fine just so long as you've hit all the points you need to (i.e. don't skip your conclusion if you still need to put in your synthesis example).

When you are done, make one last past through your essay. Make sure you included everything that was in your outline and hit all the rubric skills! Then take a deep breath and pat yourself on the back.

You did it!! Have a cupcake to celebrate.

Key Tips for How to Write a DBQ

I realize I've bombarded you with information, so here are the key points to take away:

Remember the drill for prep: establish a baseline, build skills, take another practice DBQ, repeat skill-building as necessary.

Make sure that you know the rubric inside and out so you will remember to hit all the necessary points on test day! It's easy to lose points just for forgetting something like your synthesis point.

On test day, keep yourself on track time-wise !

This may seem like a lot, but you can learn how to ace your DBQ! With a combination of preparation and good test-taking strategy, you will get the score you're aiming for. The more you practice, the more natural it will seem, until every DBQ is a breeze.

What's Next?

If you want more information about the DBQ, see my introductory guide to the DBQ .

Haven't registered for your AP test yet? See our article for help registering for AP exams .

For more on studying for the AP US History exam, check out the best AP US History notes to study with .

Studying for World History? See these AP World History study tips from one of our experts.

Ellen has extensive education mentorship experience and is deeply committed to helping students succeed in all areas of life. She received a BA from Harvard in Folklore and Mythology and is currently pursuing graduate studies at Columbia University.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

AP® World History

The ultimate list of ap® world history tips.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

Acing the AP® World History exam is undeniably a difficult task. Only 8.6% of students who took the 2019 exam scored a 5, and only 18.8% of students scored a 4. The test’s difficulty ultimately lies in how it forces you to analyze the overall patterns of history in addition to the small details.

By familiarizing yourself with trends in history as opposed to just memorizing facts, you can get a 5 on the AP® World History exam. The test can be cracked by understanding how history operates, how the world changes through cause and effect. Admittedly, it can be difficult to learn how to study for the AP® World History exam.

However, we’re here to help you score a 5 and formulate the perfect AP® World History study plan. Through practice and preparation, scoring a five is possible! By taking AP® World History practice tests, creating a thorough study plan, and maintaining a daily study routine, you will be able to ace this exam.

What We Review

Overall How To Study for AP® World History: 9 Tips for 4s and 5s

1. answer all of the questions.

Make sure your thesis addresses every single part of the question being asked for the AP® World History free-response section . Many times, AP® World History prompts are multifaceted and complex, asking you to engage with multiple aspects of a certain concept or historical era. Missing a single part can cost you significantly in the grading of your essay.

2. Lean one way in your argument

While it is possible to write essays that take two sides of an argument, it is always easier to choose a side and defend it. Trying to appease both sides during a timed essay often leads to an argument that’s not nearly as strong when you take a stance.

Here is an example of a weak thesis:

The recovery of Russia and China after the Mongols had many similarities and differences .

Here is a better one:

While both Russia and China built strong centralized governments after breaking free from the Mongols, Russia imitated the culture and technology of Europe while China became isolated and built upon its own foundations.

3. Lead your reader

Help your reader understand where you are going as you answer the prompt to the essay. Provide them with a map of a few of the key areas you are going to talk about in your essay. This should be done in your opening thesis paragraph. An easy way to achieve this is by outlining what is going to be discussed in your body paragraphs during the introduction paragraph.

4. Organize your essay with 2-3-1 in mind

When outlining the respective topics you will be discussing, start from the topic you know second best, then the topic you know least, before ending with your strongest topic area. In other words, make your roadmap 2-3-1 so that you leave your reader with the feeling that you have a strong understanding of the question being asked. This will help scaffold your argument, and it will make the essay much more readable.

5. Analyze rather than merely summarize

When the AP® exam asks you to analyze, you want to think about the respective parts of what is being asked and look at the way they interact with one another. This means that when you are performing your analysis on the AP® World History test , you want to make it very clear to your reader of what you are breaking down into its component parts.

For example, what evidence do you have to support a point of view? Who are the important historical figures or institutions involved? How are these structures organized? How does this relate back to the overall change or continuity observed in the world?

6. Use SPICER to organize and chunk your history reading

SPICER is a useful acronym that can be used to chunk and break down history into six different categories:

- S – Social

- P – Political

- I – Intellectual

- C – Culture

- E – Economic

- R – Religious

These six categories encompass the major areas of history that you will see in your reading and on your exam. Write an S next to material that deals with social issues, an E near economic, so on and so forth. This will break up your reading into more digestible chunks.

7. Familiarize yourself with the time limits

Part of the reason why we suggest practicing essays early on is so that you get so good at writing them that you understand exactly how much time you have left when you begin writing your second to the last paragraph. You’ll be so accustomed to writing under timed circumstances that you will have no worries in terms of finishing on time.

The multiple-choice section is 55 questions and 55 minutes long, so you have one minute per question. The short answer section is 3 questions and 40 minutes long; the document-based question is 1 question and timed at 1 hour. The long essay is 1 question and timed at 40 minutes.

8. Learn the rubric

If you have never looked at an AP® World History grading rubric before you enter the test, you are going in blind. You must know the rubric like the back of your hand so that you can ensure you tackle all the points the grader is looking for. Here are the 2019 Scoring Guidelines .

While all the rubrics for the DBSs vary a bit, they mostly follow a 0-3 scale where each number represents a certain task you must fulfill within your response. The DBQ section is graded on a four-scale basis:

- A) Thesis/Claim

- B) Contextualization

- C) Evidence

- D) Analysis and Reasoning

The thesis component evaluates the strength of your thesis statement, while the contextualization section evaluates your ability to describe a broader historical context relevant to the prompt. The evidence part of the rubric evaluates your analysis and use of the texts, and the analysis and reasoning section evaluates your argument overall.

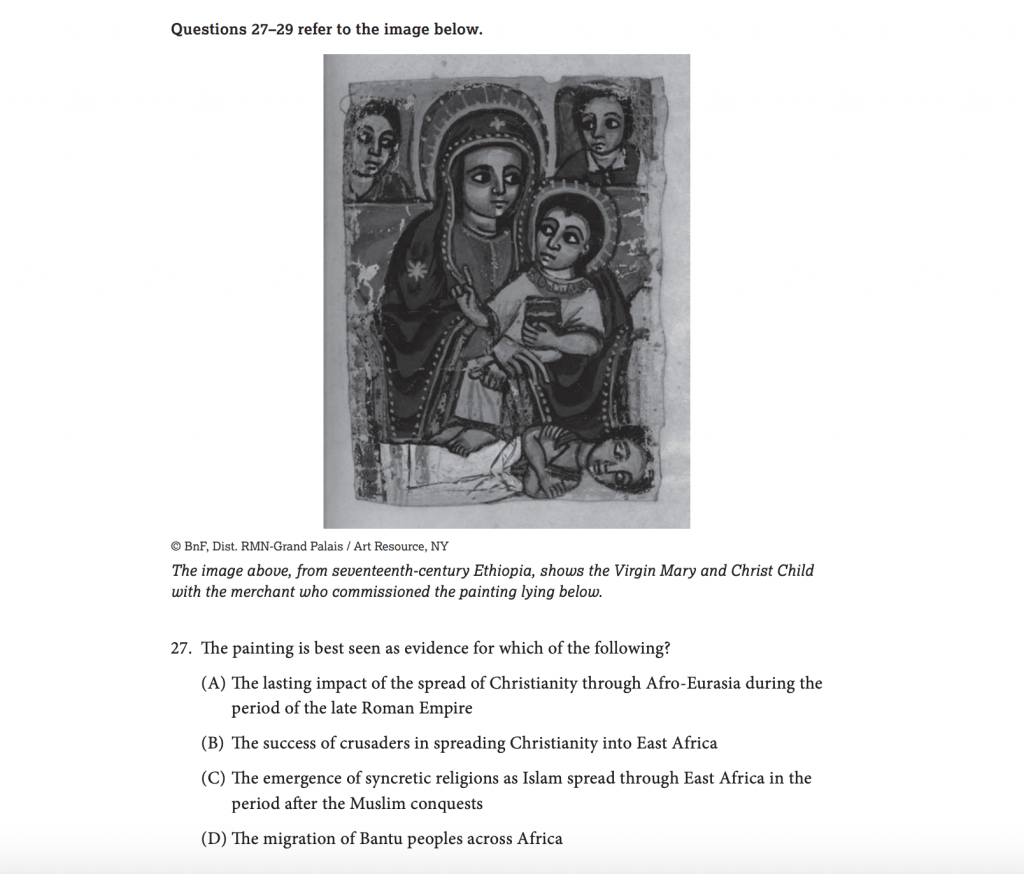

9. Familiarize yourself with analyses of art

This one is optional, but a great way to really get used to analyzing art is to visit an art museum and to listen to the way that art is described. Oftentimes the test will make you either interpret the artist’s intent and perspective or force you to expound on history through interpretation of the painting.

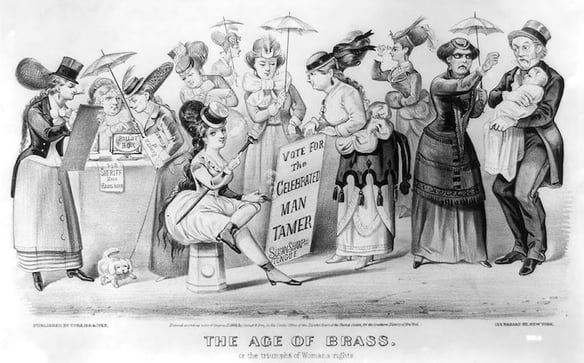

Here’s an example.

Notice how the painting is being used to assess an entire historical era. The painting is being used here as much more than a painting.

Return to the Table of Contents

AP® World History Multiple Choice Review: 11 Tips

1. identify key patterns of history.

You know that saying, history repeats itself? There’s a reason why people say that, and that is because there are fundamental patterns in history that can be understood and identified. This is especially true with AP® World History .

Think about patterns like cause and effect, action and reaction, dissemination and reception, oppressor vs. oppressed, etc. History can be best comprehended when you recognize patterns.

2. Use common sense

The beauty of AP® World History is when you understand the core concept being tested and the patterns in history; you can deduce the answer to the question. Identify what exactly is being asked and then go through the process of elimination to figure out the correct answer.

Now, this does not mean you do not study at all. This means, rather than study 500 random facts about world history, really hone in on understanding the way history interacts with different parts of the world.

Think about how minorities have changed over the course of history, their roles in society, etc. You want to look at things at the big picture so that you can have a strong grasp of each time period tested.

3. Familiarize yourself with AP® World History multiple-choice questions

If AP® World History is the first AP® test you’ve ever taken, or even if it isn’t, you need to get used to the way the College Board introduces and asks you questions. Find a review source to practice AP® World History questions.

Albert has hundreds of AP® World History practice questions and detailed explanations to work through. These questions are designed to encompass tons of years of World History, so you must become acquainted with how that history is presented to you.

4. Make a note of pain points

As you practice, you’ll quickly realize what you know really well, and what you know not so well. Figure out what you do not know so well and re-read that chapter of your textbook. Keep a chart or log of what you do not do quite so well, so when it comes time to review, you can quickly discern which area you need to study. Then, create flashcards of the key concepts of that chapter along with key events from that time period.

5. Supplement practice with video lectures

A fast way to learn is to do practice problems, identify where you are struggling, learn that concept more intently, and then practice again. Crash Course has created an incredibly insightful series of World History videos you can watch on YouTube here . And Useful Charts offers tons of great timeline-oriented videos on plenty of subjects including world history.

Afterward, go back and practice again. Practice makes perfect, especially when it comes to AP® World History. And a lot of these videos are actually pretty interesting.

6. Strikeout wrong answer choices

The second you can eliminate an answer choice, strike out the letter of that answer choice and circle the word or phrase behind why that answer choice is incorrect. This way, when you review your answers at the very end, you can quickly check through all of your answers.

One of the hardest things is managing time when you’re doing your second run-through to check your answers—this method alleviates that problem by reducing the amount of time it takes for you to remember why you thought a certain answer choice was wrong.

7. Answer every question

If you’re crunched on time and still have several AP® World History multiple-choice questions to answer, the best thing to do is to make sure that you answer each and every one of them. There is no guessing penalty for doing so, so take full advantage of this!

8. Skip questions holding you up and return to them later

If you find yourself spending more than a minute or so on a question, don’t let yourself get stuck. Instead, circle the number of the question, skip it, and return to it later if you have time. Since this is a timed component of the exam (55 minutes), the pacing is essential to scoring high. If you find yourself getting stuck, don’t fixate. Circle then move on and return.

9. Don’t be afraid to make educated guesses

This one dovetails nicely with the preceding tip. If you find yourself totally at a loss choosing an answer on the AP® World History multiple-choice section, make an educated guess. You are not penalized for answers you miss; your scores are counted by how many you get right. So it’s in your benefit to answer every question and leave none blank. So, when confronted with impossibly difficult questions, try and narrow the choices down a bit and then just make an educated guess.

10. Keep your eyes peeled for corresponding questions that provide answers

Sometimes, in multiple-choice exams, questions can actually sort of answer each other. For example, say question 12 depicts a painting of the 1789 Storming of the Bastille, and question 30 asks you to describe the mood of the late-eighteenth century France, you can use question 12 to help you answer question 30. Since many of the events in AP® World History correspond, you will likely see instances of this. Use it to your advantage.

11. Form a study group

Developing a strong memory of historical dates, events, figures, and all the stuff essential to AP® World History is crucial to acing the multiple-choice component of the exam. One way to build your memory is to form a study group with your classmates and meet weekly or bi-weekly. Before you meet, plan out which parts of world history you want to cover, and stick to it. Choose your group wisely because sometimes, study groups can quickly turn into hang-out sessions.

AP® World History FRQ: 17 Tips

1. Group the documents by intent

One skill tested on the AP® exam is your ability to relate documents to one another–this is called grouping. The idea of grouping is to essentially create a nice mixture of supporting materials to bolster a thesis that addresses the DBQ question being asked. In order to group effectively, create at least three different groupings with two subgroups each.

When you group, group to respond to the prompt. Do not group just to bundle certain documents together. The best analogy would be you have a few different colored buckets, and you want to put a label over each bucket. Then you have a variety of different colored balls in which each color represents a document, and you want to put these balls into buckets. You can have documents that fall into more than one group, but the big picture tip to remember is to group in response to the prompt.

This is an absolute must. 33% of your DBQ grade comes from assessing your ability to group.

2. Assess POV with SOAPSTONE

SOAPSTONE helps you answer the question of why the person in the document made the piece of information at that time. Remember that SOAPSTONE is an acronym:

- S – Speaker

- O – Occasion

- A – Audience

- P – Purpose

- Tone – Tone

It answers the question of the motive behind the document and can help you engage with the documents more effectively.

3. S represents Speaker or Source

You want to begin by asking yourself who is the source of the document. Think about the background of this source. Where do they come from? What do they do? Are they male or female? What are their respective views on religion or philosophy? How old are they? Are they wealthy? Poor? Etc. Understanding the source of the text will help unlock its nature, and it will allow you to approach the reading with a specific angle in mind.

4. O stands for occasion

You want to ask yourself when the document was said, where was it said, and why it may have been created. You can also think of O as representative of origin. Analyzing the occasion or origin of a historical text will provide you with much-needed context, which is essential to decoding history. When you confront a text, immediately ask yourself what the occasion of the text is.

5. A represents audience

Think about who this person wanted to share this document with. What medium was the document originally delivered in? Is it delivered through an official document, or is it an artistic piece like a painting? The intention behind a piece is crucial to understanding its meaning. If you can figure out who the text was intended for, then you can begin to unpack what it is all about. The audience is crucial.

6. P stands for the purpose

After you’ve asked who the audience of the text is, begin asking, “why?” Think, “why did this person create this document?” or “why did they say this or that?” What is the main motive behind the document? Obviously, unpacking the purpose of a text is essential to understanding it as a whole, and, again, it serves as an essential step in the process of breaking down the text.

7. S is for the subject of the document.

Next is the subject. Every text addresses a broader or larger subject either implicitly or directly, and understanding this will help chunk your reading and make your writing more sophisticated. For instance, the Silk Road is a trading route, sure, but it is also more broadly about the rise of globalism and international relationships. WWI is, of course, a catastrophic war, but it’s also about the rise of technology, international discord, humanitarianism, and even masculinity. When you read a historical text, think, “what is this really about?”

8. TONE poses the question of what the tone of the document is.

This relates closely to the speaker. The tone is a general character or attitude of a place, piece of writing, or a situation. Writers create tone through a variety of ways but pay special attention to strong vocabulary words, key phrases, literary or rhetorical devices, mood words, and more elements of writing that generate the tone. Highlight or underline them. Think about how the creator of the document says certain things. Think about the connotations of certain words.

9. Explicitly state your analysis of POV

Your reader is not psychic. He or she cannot simply read your mind and understand exactly why you are rewriting a quotation by a person from a document. Be sure to explicitly state something along the lines of, “In document X, author states, “[quotation]”; the author may use this [x] tone because he wants to signify [y].” Another example would be, “The speaker’s belief that [speaker’s opinion] is made clear from his usage of particularly negative words such as [xyz].”

10. Be conscious of how you use data from charts and tables

Sometimes you’ll come across charts of statistics. If you do, ask yourself questions like where the data is coming from, how the data was collected, who released the data, etc. You essentially want to take a similar approach to SOAPSTONE with charts and tables. Data should be analyzed rather than merely summarized.

Notice how the prompt asks you to either “identify” or “explain.” If you choose to answer one of the questions with “identify,” you must go much further than simply identifying. You must move into the realm of “explain” and “analyze.”

11. Assess maps with a strategy in mind

When you come across maps, look at the corners and center of the map. Think about why the map may be oriented in a certain way. Think about if the title of the map or the legend reveals anything about the culture the map originates from. Think about how the map was created–where did the information for the map come from. Think about who the map was intended for.

12. Assess cultural pieces with SOAPSTONE in mind

If you come across more artistic documents such as literature, songs, editorials, or advertisements, you want to really think about the motive of why the piece of art or creative writing was made and who the document was intended for. What does that specific piece tell you about the time in which it was created?

13. Be careful using blanket statements

Just because a certain point of view is expressed in a document does not mean that POV applies to everyone from that historical area. One common problem students make is expressing one sentiment for a large group of people, events, or historical eras. Be aware that history can rarely be reduced to X = Y. A grey area persists. One easy way to avoid this pitfall is to be as specific as possible. Take a look at these examples from the 2019 exam:

Blanket statement: “During 1450 to 1750 the creation of the Mongol Empire changed the role of nomads in cultural exchange. Before the Mongols, nomads acted as traders who spread trade and culture along routes, but this changed during the Mongol Empire, nomads became the protectors who patrolled the trade routes to keep them safe.”

Notice how the writer paints nomadic tribes with too wide of a wide brush and does not discuss their trade with enough specificity.

Now here’s a more specific example:

“One development that changed the role that Central Asian Nomads played in cross-regional exchanges from the period 1450– 1750 C.E., as described in the passage, was the development of maritime technology because new modes of transportation across the ocean using boats and knowledge of monsoon winds allowed countries to trade and exchange ideas and goods across regions with less overland use, which diminished the importance of central Asian nomads in exchanging goods and ideas and cultures overland. An example of this includes European maritime empires such as Britain and Portugal, who navigated to Asia on sea in order to trade at trading posts. This sufficiently decreased central Asian nomads’ need to exchange goods along the Silk Road from Europe to Asia.”

Source: Chief Reader Report

Notice how specific the writer is when discussing the nomads’ trading.

14. Understand that bias will always exist

Even if you’re given data in the form of a table, there is bias in the data. Do not fall into the trap of thinking just because there are numbers it means the numbers are foolproof. Bias can and should be withdrawn from any and all sources.

Here’s an example of a bias historical statement: The Russian Revolution was initiated by an angry lower-class looking for revenge against a greedy ruling class.

While this may be somewhat true, notice how the words “angry” and “greedy” indicate particular moods toward these subjects from the author.

Instead, the statement should be written as “The Russian Revolution was initiated by Russia’s lower class against the ruling monarchy.

15. Be creative with introducing bias

Many students understand that they need to show their understanding that documents can be biased, but they go about it the wrong way. Rather than outright stating, “The document is biased because [x],” try, “In document A, the author is clearly influenced by [y] as he states, “[quotation].” See the difference? It’s subtle but makes a clear difference in how you demonstrate your understanding of bias.

16. Don’t forget to B.S. in your DBQ

No, no. It’s not what you’re thinking. By B.S., we mean to be specific. When you are discussing a certain revolutionary leader, an economic policy, a governmental act, or some other different aspect of AP® World History, be sure to specifically name your topics. Do not just generalize, but B.S.!

Here’s an example of a general statement: “ While both sides fought the Civil War over the issue of slavery, the North fought for moral reasons while the South fought to preserve its own institutions.”

And here’s one that’s more specific: “While both Northerners and Southerners believed they fought against tyranny and oppression, Northerners focused on the oppression of slaves while Southerners defended their own right to self-government.”

17. Leave yourself out of it

Do not refer to yourself when writing your DBQ essays! “I” has no place in these AP® essays. Academic essays need to remain professional and focused, and the introduction of “I” detracts from that tone. And the reader already knows that your essay is written from your perspective, so an “I” is just redundant.

Tips Submitted by AP® World History Teachers

Overall ap® world history tips, 1. use high polymer erasers.

When answering the multiple-choice scantron portion of the AP® World History test, use a high polymer eraser. It is the only eraser that will fully erase on a scantron. Amazon carries plenty for cheap. Thanks for the tip from Ms. J. at Boulder High School.

2. Stay ahead of your reading and when in doubt, read again

You are responsible for a huge amount of information when it comes to tackling AP® World History, so make sure you are responsible for some of it. Create a daily reading habit where you spend at least an hour per day digesting your AP® World History material. There is simply too much for you to try and cram. And you can’t leave all the work up to your instructor. It’s a team effort. Thanks for the tip from Mr. E at Tri-Central High.

3. Integrate video learning

A great way to really solidify your understanding of a concept is to watch supplementary videos on the topic. Crash Course offers a lot of great video content on World History, and Heimler’s History does as well. Then, after watching a video, read the topic again to truly master it. Thanks for the tip from Mr. D at Royal High School.

4. Practice with transparencies or a whiteboard

Use transparencies or a whiteboard to create overlay maps for each of the six periods of AP® World History at the start of each period so that you can see a visual of the regions of the world being focused on. History is perfect for big whiteboards because they allow you to draw out large maps, event chains, and more. Thanks for the tip from Ms. W at Riverbend High.

AP® World History Multiple-Choice Tips

1. read every word.

Oftentimes in AP® World History , many questions can be answered without specific historical knowledge. Many questions require critical thinking and attention to detail; the difference between a correct answer and an incorrect answer lies in just one or two words in the question or the answer. Be aware of answer choices like “none of the above” or “all of the above,” as either none or all of the questions must be correct or incorrect. Keep that totality in mind. Thanks for the tip from Mr. R. at Mandarin High.

2. Look at every answer option

Don’t go for the first “correct” answer; find the most “bulletproof” answer. The one you’d best be able to defend in a debate. Think of the “bulletproof” answer as an answer which can be tested and tested and tested but still holds up. Run this through your head while choosing an answer, and constantly reevaluate.

3. Annotate the text

Textbook reading is essential for success in AP® World History, but learn to annotate smarter, not harder. Be efficient in your reading and note-taking. Read, reduce, and reflect. To read – use sticky notes. Using post-its is a lifesaver – use different color stickies for different tasks (pink – summary, blue – questions, green – reflection, etc.) Reduce – go back and look at your sticky notes and see what you can reduce – decide what is truly essential material to know or question. Then reflect – why are the remaining sticky notes important? How will they help you not just understand the content, but also understand contextualization or causality or change over time? What does this information show you? Thanks for the tip from Ms. J at Legacy High.

AP® World History FRQ Tips

1. master writing a good thesis.

In order to write a good thesis, you want to make sure it properly addresses the whole question or prompt, effectively takes a position on the main topic, includes relevant historical context, and organize key standpoints. Heimler’s History has a good how-to guide on AP® World History thesis statements that’s certainly worth checking out. Thanks for the tip from Mr. G at Loganville High.

2. Tackle DBQs with SAD and BAD

With the DBQ, think about the S ummary, A uthor, and D ate & Context. Also, consider the B ias and A dditional D ocuments to verify the bias. Thanks for the tip from Mr. G at WHS.

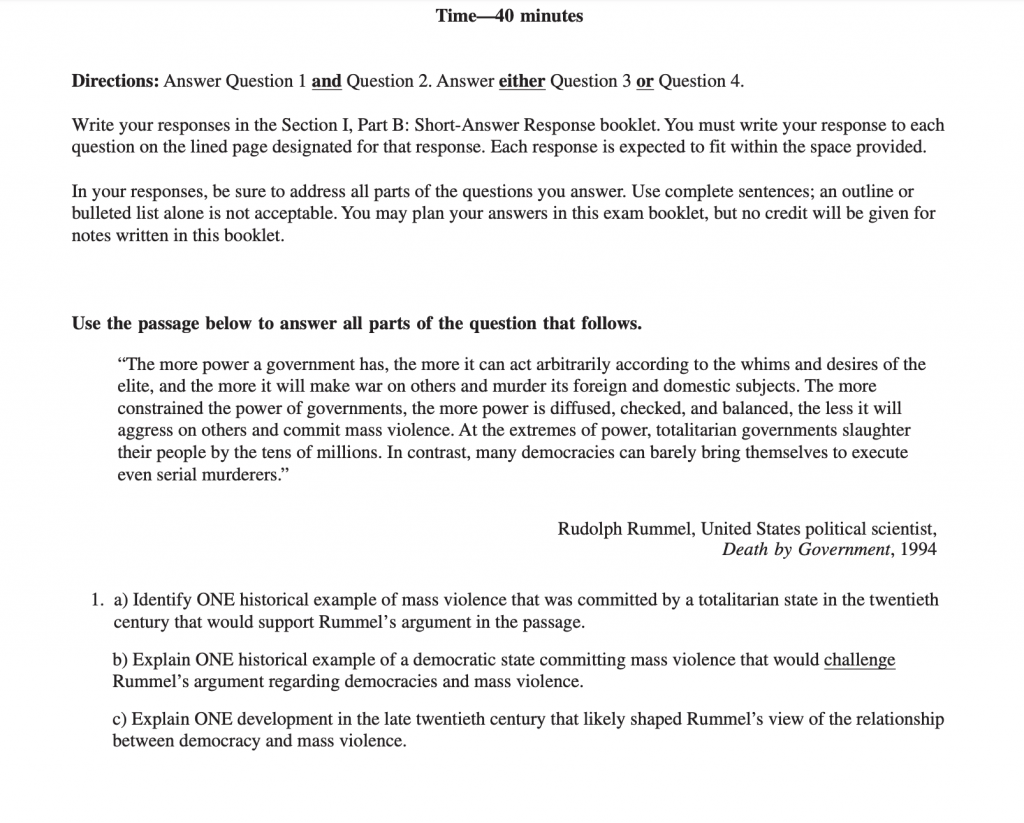

Go through this prompt from the 2019 exam and notice how SAD and BAD work well. It is about totalitarian governments by Rudolph Rummel, a US political scientist, from 1994. Does it present any bias? Additional documents? SAD and BAD can.

3. Create a refined thesis in your conclusion

Do not simply blow off your conclusion paragraph. Think of the conclusion as the decorative bow that nicely holds the box together. By the time you finish your essay, you have a much more clear idea of how to answer the question. Take a minute and revisit the prompt and try to provide a much more explicit and comprehensive thesis than the one you provided in the beginning as your conclusion. This thesis statement is much more likely to give you the point for the thesis than the rushed thesis in the beginning. Thanks for the tip from Mr. R at Mission Hills High.

4. Relate back to the themes

Understanding 10,000 years of world history is hard. Knowing all the facts is darn near impossible. If you can use your facts/material and explain it within the context of one of the APWH themes, it makes it easier to process, understand, and apply. The themes are your friends. Thanks for the tip from Ms. J at Legacy High.

5. Look for the missing voice in DBQs

First, look for the missing voice. Who haven’t you heard from in the DBQ? Who’s voice would really help you answer the question more completely? Next, if there isn’t really a missing voice, what evidence do you have access to, that you would like to clarify? For example, if you have a document that says excessive taxation led to the fall of the Roman Empire, what other pieces of information would you like to have access to that would help you prove or disprove this statement? Maybe a chart that shows tax amounts from prior to the 3rd Century Crisis to the mid of the 3rd-century crisis? Thanks for the tip from Ms. J at Legacy High.

Wrapping Things Up: The Ultimate List of AP® World History Tips

Doing well in AP® World History comes down to recognizing patterns and trends in history, and familiarizing yourself with the nature of the test. Students often think the key to AP® history tests is memorizing every single fact of history, and the truth is you may be able to do that and get a 5, but the smart way of doing well on the test comes from understanding the reason why we study history in the first place.

By learning the underlying patterns that are tested on the exam, for example, how opinions towards women may have influenced the social or political landscape of the world during a certain time period, you can create more compelling theses and demonstrate to AP® readers a clear understanding of the bigger picture.

The bottom line is this: in order to ace this exam, you have to prepare. We offer tons of AP® World History practice questions , practice exams , AP® World History DBQs , and more. We recommend that you take a look at our extensive catalog, and develop a daily study routine. With this proper preparation, you will ace the exam!

Interested in a school license?

12 thoughts on “the ultimate list of ap® world history tips”.

When writing the DBQ, do not waste time quoting the documents; paraphrase and show the grader you understand what it’s saying.

Excellent tip, Rebecca!

Good tips for AP® World History.

Glad you enjoyed!

Thanks to AP® World History Teachers for these great tips.. keep it up.

Yes, they’re great!

An additional tip is to bring your own watch to the exam so that you can easily keep track of time.

Thanks for the addition!

My teacher submitted the first tip from teachers on high polymer erasers, and she is right. I only ever use these eraser for erasing anything in school and they work much better and last much longer than the stubby pink things on the end of pencils that people like to call “erasers.”

Thanks for sharing!

An extra tip is to convey your own particular watch to the exam so you can without much of a stretch monitor time.

Comments are closed.

Popular Posts

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

Find what you need to study

AP World Long Essay Question (LEQ) Overview

15 min read • may 10, 2022

Zaina Siddiqi

Exam simulation mode

Prep for the AP exam with questions that mimic the test!

Overview of the Long Essay Question (LEQ)

Section II of the AP Exam includes three Long Essay Question (LEQ) prompts. You will choose to write about just one of these.

The formatting of prompts varies somewhat between the AP Histories, though the rubric does not. In AP World History, the prompt includes a sentence that orients the writer to the time, place, and theme of the prompt topic, while prompts in AP US History and AP European History typically do not. However, the rubrics and scoring guidelines are the same for all Histories.

Your answer should include the following:

A valid thesis

A discussion of relevant historical context

Use of evidence supports your thesis

Use of a reasoning skill to organize and structure the argument

Complex understanding of the topic of the prompt

We will break down each of these aspects in the next section. For now, the gist is that you need to write an essay that answers the prompt, using evidence. You will need to structure and develop your essay using one of the course reasoning skills.

Many of the skills you need to write a successful LEQ essay are the same skills you will use on the DBQ. In fact, some of the rubric points are identical, so you can use a lot of the same strategies on both writing tasks!

You will have three choices of prompts for your LEQ. All three prompts will focus on the same reasoning skills, but the time periods will differ in each prompt. Prompt topics may span across time periods specified in the course outline, and the time period breakdowns for each prompt are as follows:

Writing time on the AP Exam includes both the Document Based Question (DBQ) and the (LEQ), but it is suggested that you spend 40 minutes completing the LEQ. You will need to plan and write your essay in that time.

A good breakdown would be 5 min. (planning) + 35 min. (writing) = 40 min.

The LEQ is scored on a rubric out of six points, and is weighted at 15% of your overall exam score. We’ll break down the rubric next.

How to Rock the LEQ: The Rubric

The LEQ is scored on a six point rubric, and each point can be earned independently. That means you can miss a point on something and still earn other points with the great parts of your essay.

Note: all of the examples in this section will be for this prompt from AP World History: Modern. You could use similar language, structure, or skills to write samples for prompts in AP US History or AP European History.

Let’s break down each rubric component...

What is it?

The thesis is a brief statement that introduces your argument or claim, and can be supported with evidence and analysis. This is where you answer the prompt.

Where do I write it?

This is the only element in the essay that has a required location. The thesis needs to be in your introduction or conclusion of your essay. It can be more than one sentence, but all of the sentences that make up your thesis must be consecutive in order to count.

How do I know if mine is good?

The most important part of your thesis is the claim , which is your answer to the prompt. The description the College-Board gives is that it should be “historically defensible,” which really means that your evidence must be plausible. On the LEQ, your thesis needs to be related topic of the prompt.

Your thesis should also establish your line of reasoning. Translation: address why or how something happened - think of this as the “because” to the implied “how/why” of the prompt. This sets up the framework for the body of your essay, since you can use the reasoning from your thesis to structure your body paragraph topics later.

The claim and reasoning are the required elements of the thesis. And if that’s all you can do, you’re in good shape to earn the point.

Going above-and-beyond to create a more complex thesis can help you in the long run, so it’s worth your time to try. One way to build in complexity to your thesis is to think about a counter-claim or alternate viewpoint that is relevant to your response. If you are using one of the course reasoning process to structure your essay (and you should!) think about using that framework for your thesis too.

In a causation essay, a complex argument addresses causes and effects.

In a comparison essay, a complex argument addresses similarities and differences.

In a continuity and change over time essay, a complex argument addresses change and continuity .

This counter-claim or alternate viewpoint can look like an “although” or “however” phrase in your thesis.

Powers in both land-based and maritime empires had to adapt their rule to accommodate diverse populations. However, in this era land-based empires were more focused on direct political control, while the maritime empires were more based on trade and economic development.

This thesis works because it clearly addresses the prompt (comparing land and maritime empires). It starts by addressing a similarity, and then specifies a clear difference with a line of reasoning to clarify the actions of the land vs. maritime empires.

Contextualization

Contextualization is a brief statement that lays out the broader historical background relevant to the prompt.

There are a lot of good metaphors out there for contextualization, including the “previously on…” at the beginning of some TV shows, or the famous text crawl at the beginning of the Star Wars movies.

Both of these examples serve the same function: they give important information about what has happened off-screen that the audience needs to know to understand what is about to happen on-screen.

In your essay, contextualization is the same. You give your reader information about what else has happened, or is happening, in history that will help them understand the specific topic and argument you are about to make.

There is no specific requirement for where contextualization must appear in your essay. The easiest place to include it, however, is in your introduction . Use context to get your reader acquainted with the time, place, and theme of your essay, then transition into your thesis.

Good contextualization doesn’t have to be long, and it doesn’t have to go into a ton of detail, but it does need to do a few very specific things.

Your contextualization needs to refer to events, developments and/or processes outside the time and place of the prompt. It could address something that occurred in an earlier era in the same region as the topic of the prompt, or it could address something happening at the same time as the prompt, but in a different place. Briefly describe this outside information.