Informative Speaking

The topic, purpose, and thesis.

Before any work can be done on crafting the body of your speech or presentation, you must first do some prep work—selecting a topic, formulating a purpose statement, and crafting a thesis statement. In doing so, you lay the foundation for your speech by making important decisions about what you will speak about and for what purpose you will speak. These decisions will influence and guide the entire speechwriting process, so it is wise to think carefully and critically during these beginning stages.

I think reading is important in any form. I think a person who’s trying to learn to like reading should start off reading about a topic they are interested in, or a person they are interested in. – Ice Cube

Questions for Selecting a Topic

- What important events are occurring locally, nationally and internationally?

- What do I care about most?

- Is there someone or something I can advocate for?

- What makes me angry/happy?

- What beliefs/attitudes do I want to share?

- Is there some information the audience needs to know?

Selecting a Topic

“The Reader” by Shakespearesmonkey. CC-BY-NC .

Generally, speakers focus on one or more interrelated topics—relatively broad concepts, ideas, or problems that are relevant for particular audiences. The most common way that speakers discover topics is by simply observing what is happening around them—at their school, in their local government, or around the world. This is because all speeches are brought into existence as a result of circumstances, the multiplicity of activities going on at any one given moment in a particular place. For instance, presidential candidates craft short policy speeches that can be employed during debates, interviews, or town hall meetings during campaign seasons. When one of the candidates realizes he or she will not be successful, the particular circumstances change and the person must craft different kinds of speeches—a concession speech, for example. In other words, their campaign for presidency, and its many related events, necessitates the creation of various speeches. Rhetorical theorist Lloyd Bitzer [1] describes this as the rhetorical situation. Put simply, the rhetorical situation is the combination of factors that make speeches and other discourse meaningful and a useful way to change the way something is. Student government leaders, for example, speak or write to other students when their campus is facing tuition or fee increases, or when students have achieved something spectacular, like lobbying campus administrators for lower student fees and succeeding. In either case, it is the situation that makes their speeches appropriate and useful for their audience of students and university employees. More importantly, they speak when there is an opportunity to change a university policy or to alter the way students think or behave in relation to a particular event on campus.

But you need not run for president or student government in order to give a meaningful speech. On the contrary, opportunities abound for those interested in engaging speech as a tool for change. Perhaps the simplest way to find a topic is to ask yourself a few questions. See the textbox entitled “Questions for Selecting a Topic” for a few questions that will help you choose a topic.

There are other questions you might ask yourself, too, but these should lead you to at least a few topical choices. The most important work that these questions do is to locate topics within your pre-existing sphere of knowledge and interest. David Zarefsky [2] also identifies brainstorming as a way to develop speech topics, a strategy that can be helpful if the questions listed in the textbox did not yield an appropriate or interesting topic.

Starting with a topic you are already interested in will likely make writing and presenting your speech a more enjoyable and meaningful experience. It means that your entire speechwriting process will focus on something you find important and that you can present this information to people who stand to benefit from your speech.

Once you have answered these questions and narrowed your responses, you are still not done selecting your topic. For instance, you might have decided that you really care about conserving habitat for bog turtles. This is a very broad topic and could easily lead to a dozen different speeches. To resolve this problem, speakers must also consider the audience to whom they will speak, the scope of their presentation, and the outcome they wish to achieve. If the bog turtle enthusiast knows that she will be talking to a local zoning board and that she hopes to stop them from allowing businesses to locate on important bog turtle habitat, her topic can easily morph into something more specific. Now, her speech topic is two-pronged: bog turtle habitat and zoning rules.

Formulating the Purpose Statements

“Bog turtle sunning” by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Public domain.

By honing in on a very specific topic, you begin the work of formulating your purpose statement . In short, a purpose statement clearly states what it is you would like to achieve. Purpose statements are especially helpful for guiding you as you prepare your speech. When deciding which main points, facts, and examples to include, you should simply ask yourself whether they are relevant not only to the topic you have selected, but also whether they support the goal you outlined in your purpose statement. The general purpose statement of a speech may be to inform, to persuade, to inspire, to celebrate, to mourn, or to entertain. Thus, it is common to frame a specific purpose statement around one of these goals. According to O’Hair, Stewart, and Rubenstein, a specific purpose statement “expresses both the topic and the general speech purpose in action form and in terms of the specific objectives you hope to achieve.” [3] For instance, the bog turtle habitat activist might write the following specific purpose statement: At the end of my speech, the Clarke County Zoning Commission will understand that locating businesses in bog turtle habitat is a poor choice with a range of negative consequences. In short, the general purpose statement lays out the broader goal of the speech while the specific purpose statement describes precisely what the speech is intended to do.

Success demands singleness of purpose. – Vince Lombardi

Writing the Thesis Statement

The specific purpose statement is a tool that you will use as you write your talk, but it is unlikely that it will appear verbatim in your speech. Instead, you will want to convert the specific purpose statement into a thesis statement that you will share with your audience. A thesis statement encapsulates the main points of a speech in just a sentence or two, and it is designed to give audiences a quick preview of what the entire speech will be about. The thesis statement for a speech, like the thesis of a research- based essay, should be easily identifiable and ought to very succinctly sum up the main points you will present. Moreover, the thesis statement should reflect the general purpose of your speech; if your purpose is to persuade or educate, for instance, the thesis should alert audience members to this goal. The bog turtle enthusiast might prepare the following thesis statement based on her specific purpose statement: Bog turtle habitats are sensitive to a variety of activities, but land development is particularly harmful to unstable habitats. The Clarke County Zoning Commission should protect bog turtle habitats by choosing to prohibit business from locating in these habitats. In this example, the thesis statement outlines the main points and implies that the speaker will be arguing for certain zoning practices.

- Bitzer, L. (1968). The rhetorical situation. Philosophy & Rhetoric , 1 (1), 1 – 14. ↵

- Zarefsky, D. (2010). Public speaking: Strategies for success (6th edition). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. ↵

- O’Hair, D., Stewart, R., Rubenstein, H. (2004). A speaker’s guidebook: Text and reference (2nd edition). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s. ↵

- Chapter 8 The Topic, Purpose, and Thesis. Authored by : Joshua Trey Barnett. Provided by : University of Indiana, Bloomington, IN. Located at : http://publicspeakingproject.org/psvirtualtext.html . Project : The Public Speaking Project. License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- The Reader. Authored by : Shakespearesmonkey. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/shakespearesmonkey/4939289974/ . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Image of a bog turtle . Authored by : R. G. Tucker, Jr.. Provided by : United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Located at : http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bog_turtle_sunning.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Privacy Policy

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.4: The Topic and Thesis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 79285

- Keith Green, Ruth Fairchild, Bev Knudsen, & Darcy Lease-Gubrud

- Ridgewater College via Minnesota State Colleges and Universities

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- explain how creating a speech is a holistic process.

- develop a speech in the proper order .

- create a speech using the appropriate lengths for sections.

- apply topic selection criteria to the selection of a topic for an audience.

- develop a specific speech purpose .

- translate a specific speech purpose into a properly worded thesis statement .

Although there are "steps" to preparing a speech, a more appropriate way of thinking of speech preparation is as a dynamic process. Instead of seeing speech development as a linear process, it is better to see it as a holistic process of creating all components of the speech so they fit together as an effective whole. A puzzle metaphor demonstrates this approach.

As the model illustrates, the core of this dynamic process is the audience analysis, and the speech is built around our understanding of our audience. We then develop the content (selecting the topic, finding the content, and organizing the speech), and prepare the content for presentation (practice the delivery).

Although there is a sense of a linear process, sticking to some sort of artificial step process is not as important as making sure that all the pieces fit together as an effective, unified whole. Although we may have developed one area, as we prepare the whole speech, we may need to revisit earlier parts of the process and alter those to achieve a unified whole.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Figure 1

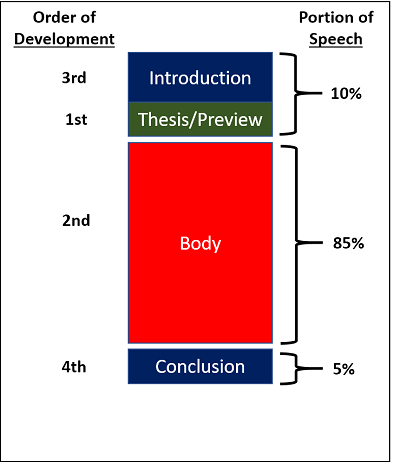

While there are a variety of ways to organize a speech, the most common structure breaks the speech into four parts:

- Introduction

- Thesis/preview

- Body of the speech

Portions of the Speech

The introduction, ending with the thesis/preview, comprises approximately 10% of the speech. The body of the speech is about 85% of the speech, and the remaining 5% is the conclusion. The percentages should be used as guidelines for the speaker, not as absolutes. The majority of the speaker’s efforts should be focused on relating the core information or arguments the speaker needs to share and the audience is there to hear. Since the body of the speech contains this core information, most of the time should be spent in that area.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Figure 2

- Order of development

In developing the speech, novice speakers often make the mistake of starting with the introduction. Since the introduction comes first, it seems logical to start there; however, this is wrong. Creating the thesis is the first step in good speech development. Until we know what the speech is about, we cannot effectively determine an introduction. Just as we cannot introduce a person we do not know, we cannot introduce a topic not yet developed. The most effective order of preparation is:

- Thesis. Since the thesis defines what the speech is about and what it is not about, developing it first helps guide the speaker in developing the body, doing research, and staying properly focused.

- Body. The body of the speech is the key content the audience is there to hear, so the speaker should spend a substantive amount of time researching, organizing, and fine-tuning this core content.

- Introduction. A speech introduction is the most creative part of the process. Since it is intended to pull the audience into the thesis and prepare them for the body, by waiting until after developing the body, the speaker will have a clear sense of what the introduction should do. During research for the body, it is common to come across a quotation, example, or some other idea for the attention getting device of the introduction.

- Conclusion. While it is the shortest part of a speech, it is very important as it is the last thing the audience will hear, leaving the audience with their final impression of the speech. This is developed last as there are ways to conclude a speech that are built on how the speaker begins the speech.

While this order of development is important, always remember the “puzzle” metaphor: we have to work to make all the parts fit together, so there can be a lot of revisiting parts to alter or fine tune them. Speech development is a dynamic process in which changing one part of the speech may have a ripple effect, affecting other parts. In the end, a good speaker makes sure that the speech is consistent, coherent, organized, and flows well for the audience.

One of the most challenging steps classroom students face when given the classic speech assignment is to select and narrow a topic to fit the time limits of the assignment.

Coming up with a topic “out of the blue” is quite difficult. Realistically, finding a topic for a classroom speech is far more difficult than finding one for a speech in a work or community setting.

The vast majority of presentations outside the classroom will be on topics in which the speaker is well versed and comfortable. If asked to speak, it will typically be to share knowledge within their field of expertise. If a business hires a Communication Studies instructor to present at a training session, they are clearly hiring them for expertise in communication. Even then, the speaker still has a responsibility to narrow to a specific topic, to adapt it to their audience and the occasion, and to fit the time limits. So outside of the initial step, determining the overall subject, speakers still have to go through the topic development process.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Figure 3

Topic Selection Criteria

In selecting a topic, one of the most common mistakes novice speakers make to take a sender-based approach. This is assuming the audience has a strong interest in the same things the speaker feels passionate about. Just because a speaker may be deeply into video gaming does not inherently mean the audience shares that interest. To select a good topic, the speaker needs to be receiver-based and objectively consider what is most likely to be successful. While the speaker’s interest can certainly serve as a good starting point to identify a general topic, the specific topic and approach to the topic must be carefully considered.

There are four criteria to determine the appropriateness of a topic:

- Audience Interest We need to select a topic we think will appeal to the specific audience. This may be a topic we know the audience will have an immediate interest in, or one in which the audience will have an interest once we develop the topic to some degree. Being receiver-based, the speaker must be honest in their assessment of the topic and the audience, careful not to project their own interests on the audience.

- Speaker Interest Although audience interest is certainly key, the speaker must also have an interest in the topic. A lack of speaker interest can be deadly. If the speaker is unmotivated to develop and present the speech, the speech usually sounds as if the speaker is bored and does not care. The speaker loses their own sense of desire to do a good job. A good topic is one that has a healthy balance of audience interest and speaker interest.

- Occasion Appropriateness We need to consider why the audience is gathered and select a topic that fits the occasion. If the audience is gathered at a business conference, learning new ways of interacting with clients, an informative topic on some aspect of communication skill may be appropriate. For a commencement address, talking about the dire state of the economy may not fit the celebratory nature of the event; the topic should invoke growth, opportunity, and an optimistic future. We want our topic to complement the reason the audience is gathered.

- Time Limits The speaker must fit the speech into the given time limits. The speech needs to fill the allotted time, and yet it cannot exceed that given time. It is a core speaker responsibility to treat the audience with respect and to fill those time limits appropriately. Exceeding time limits is simply not an option. If a topic cannot be covered within a given time, the speaker has two options: limit the topic, or get a new topic. As we know from looking at culture, Americans are quite monochronic. We see time as a resource, like money, to be budgeted and spent wisely. When speeches end on time, we have gotten what we have paid for. If they run a little short, we may feel we got a deal, but if they run quite short, we feel we got cheated. The audience is spending their time on the speaker; give them their money’s worth. On the other end, if the speech runs overtime, the speaker is "stealing" time from the audience, taking our time resource without our permission. Time limits are very important in a monochronic culture.

Narrowing a Topic

Since the speaker needs to fit the speech into the allotted time, we need to move from a broader topic to a narrower, much more specific topic. Finding a specific topic is a process of analysis, selection, and narrowing. The goal of the process is to find a specific topic that fits the same criteria as discussed above: audience interest; speaker interest; occasion appropriateness; and time limits.

A good way to narrow the topic is to start with a broader topic and brainstorm a large list of sub-topics. Using the previous four criteria, narrow the topic to the best fit. If the topic is still too large, repeat the process as often as needed to reach a manageable size topic.

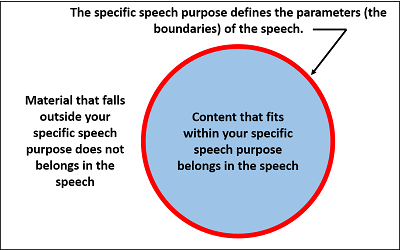

After finding that specific topic, develop the specific speech purpose . The specific speech purpose is the narrow, focused direction the speech will be taking . The function of the specific speech purpose is twofold: to identify what goes in the speech, and to identify what does not go in the speech. The specific speech purpose establishes the parameters of the speech. We use the parameters as guidance as to what to include in the speech and what to keep out of the speech. This is an important consideration. Unless the speaker keeps a tight rein on the development of the speech, the speech can get out of control, suddenly diverting into a different area or expanding beyond the time limit.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Figure 4

For example:

- After listening to my speech, the audience will be informed of how to write an effective resume.

- After listening to my speech, the audience will be informed of alternative forms of financial aid.

- After listening to my speech, the audience will be informed of creative ways of using macaroni and cheese.

For persuasion, the specific speech purposes would be slightly different, reflecting the idea of changing an audience's belief, attitude, or action:

- After listening to my speech, the audience will be persuaded to donate blood.

- After listening to my speech, the audience will be persuaded to vote for the school referendum.

- After listening to my speech, the audience will be persuaded to use a designated driver.

Once the specific speech purpose has been developed, we can easily create the thesis . The thesis is the specific, concise statement of intent for the speech . It is the one, single sentence clearly stating exactly what the speech will be addressing. Converting the specific speech purpose to the thesis is simple:

- "After listening to my speech, the audience will be informed of how to write an effective resume." becomes "Today I'll take you through the steps of writing an effective resume."

- "After listening to my speech, the audience will be informed of alternative forms of financial aid." becomes "There are several alternate forms of financial aid for you to consider."

- "After listening to my speech, the audience will be informed of creative ways of using macaroni and cheese." becomes "I'll show you several creative ways of using macaroni and cheese."

- "After listening to my speech, the audience will be persuaded to donate blood." becomes "Today I'll show you why it is important that you donate blood."

- "After listening to my speech, the audience will be persuaded to vote for the school referendum." becomes "Voting for the upcoming school referendum is important for the success of our schools."

- " After listening to my speech, the audience will be persuaded to use a designated driver." becomes "When you go out partying, you should use a designated driver."

There are several traits of a good speech thesis:

- Concise . The thesis is a simple, straightforward sentence clearly telling the audience what the speech is going to be about.

- Grammatically simple . There is one subject and one predicate; it is not a compound sentence, nor a compound-complex sentence. The thesis is not a question.

- Blatant . A speech thesis is more blunt and obvious than what we might use in writing.

- Identifies the parameters of the speech . It tells the audience what the speaker will be doing; which, by definition, also tells the audience what the speaker is not doing.

- Consistent with the speaker's overall speech purpose . The wording reflects the proper informative or persuasive tone.

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Speech Development

Parts of the Speech

- Portions of the speech

- Audience interest

- Speaker interest

- Occasion appropriateness

- Time limits

Specific Speech Purpose The Thesis

- Grammatically simple

- Identifies parameters

- Consistent with purpose

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.2: What is the Point? Thesis and Main Ideas

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 13716

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Main ideas provide the structure for our efforts at communication. You may also know main ideas under their alias, “topic sentence.”

Learning Objectives

- In reading we analyze main ideas to better understand what an author or speaker is trying to communicate.

- In writing we use main ideas to organize paragraphs so that our audience can better understand what we are trying to communicate.

Stated Main Idea

Stated main ideas are exactly what they sound like – main ideas that are directly stated in a passage. You can literally underline or highlight a stated main idea in a text, and you should do this when you are reading a textbook for a class.

Implied Main Idea: What are you trying to say?

The word implied means “suggested but not directly expressed.” Use this definition to help you define “implied main idea.”

What is an “implied main idea?”

How is an implied main idea different from a stated main idea?

How to find the Elusive Main idea

How can you identify the main idea in a text or spoken communication? Whether you are looking at a stated main idea or an implied main idea, the following strategies can help.

Strategy 1:

Ask yourself:

- What is the point of the piece?

- What is the one thing the author/speaker wants me to know about this?

Strategy 2 :

- If you are still struggling to locate the main idea, back up and identify the topic. The topic is a word or phrase that the paragraph is about.

- Then ask yourself “what about” the topic? This is likely the main idea.

- It never hurts to discuss the piece with another person. Sometimes this helps you to clarify your understanding.

Strategy 3 – for implied main ideas:

- Read the passage for which you are seeking a main idea. Look for words or ideas that are repeated frequently.

- Then use Strategy 2 to derive your own version of a main idea statement.

Main Ideas and Details are in a Relationship

Main ideas and supporting details have a pretty simple relationship. The main idea is the center of attention, and the supporting details function to support the main idea. If these were two people, this would be a pretty unfair relationship, but in writing or speaking, it is entirely acceptable. After all, only one idea can be the ‘focus.’

Whether you are reading, treasure-hunting to find main ideas and supporting details in your textbook, or you are writing an essay, a graphic organizer can be a helpful tool. There are all kinds of graphic organizers and metaphors for working with main ideas and supporting details, but sometimes it’s more efficient to use a simple diagram. Review the diagrams and graphic organizers for main ideas by doing a Google search.

Check your syllabus. What assignments are coming up to which you will apply your understanding of main ideas and supporting details? When will this be due?

Speech Communication

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- B.A. Degree Plan: 4 Year Graduation Guarantee

- B.S. Degree Plan: 4 year Graduation Guarantee

- Graduate Studies

- Speech Communication Minor

- Academic Advising

- Lambda Pi Eta Honor Society

- Forensics Team

- Scholarships

- COMM Internship Requirements (COMM 410)

- Alumni and Friends

- Mind Work/Brainstorming

Constructing a Thesis

- Writing an Introduction

- Supporting a Thesis

- Developing Arguments

- Writing a Conclusion

- Punctuation

- Style and Organization

- What's the purpose of a style manual? How do I choose a style manual for my paper?

- How do I get started planning a research paper? How do I select a topic?

- How does research fit into my writing plan?

- When I write a research paper, what resources should I have on hand?

- Bibliographic Information

- Citation Information

- Title Pages, Headings, Margins, Pagination, and Fonts

- Internet Links/Resources

- OSU Writing Center

- Communication Journals

- Tips on In-Class Writing

- Sample of a Professor's Remarks on a Student Paper

You are here

You have thought about your paper for days, perhaps weeks. You have read research, talked to friends about topics, discussed your assignment in class, and made various notes to yourself about what you want to write. The time has come to put pen to paper.

The first step is to construct a strong, compelling, succinct thesis. Constructing your thesis can be frustrating and time-consuming, but it is one of the most important tasks you will undertake while writing your paper. Reconstruct, rewrite, and rework your thesis until it clearly states your topic and direction or claim. Ultimately you want your thesis to be correct (including a topic and direction or claim), but you also want it to contain insightful, provocative ideas with regard to the topic; in other words, work to construct a thesis that expresses a more intriguing insight than the predictable application of theory or concept to routine communication behaviors or texts. You will benefit by efforts you make toward writing an excellent thesis. A well-constructed thesis guides your paper; it makes the writing of the paper easier and more effective.

If you find that writing the paper is confusing or difficult, you may be experiencing a common problem: a lack of direction or claim. Students often write theses that state the topic of the paper but not the direction or claim. Look at the thesis you have constructed. Check again to be sure the direction or claim of the thesis is clear. For example, these two theses provide clear topics without clear directions or claims:

- Leslie Baxter claims that all relationships operate on a set of dialectic tensions.

- People who argue about abortion use both absolute and relative terms.

The topic of the first thesis (1) is Leslie Baxter's claims. The topic of the second thesis (2) is the use of absolute and relative terms in abortion arguments. To complete each of these thesis statements, the writers must assert a direction or claim:

- A.) Although Leslie Baxter claims that all relationships operate on a set of dialectic tensions, she overlooks two important tensions of developmental and individual pacing. B.) Leslie Baxter's claim that all relationships operate on a set of dialectic tensions defines and clarifies the nature of communication problems couples may experience during the revision stages of their relationships.

- A.) Because arguments about abortion are expressed either in relative or absolute terms, arguers can find no mutual agreement or middle ground. B.) People who make absolute arguments about abortion are attempting to impose their principles on others; people who use relative terms have difficulty defining a code of ethics for themselves.

Your topic names the subject you will write about; your direction or claim is critical to tell the reader where you intend to go with that topic. Once your thesis contains both topic and direction or claim, you can begin the next step of writing your paper, supporting your thesis.

writingguide-highlight.jpg

Writing Guide Home

- Beginning the Writing

- Editing for Common Errors

- Questions about the Nature of Academic Writing

- Formatting the Paper

- Other Writing Sources

Contact Info

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

School of Communication

E-Mail: School of Communication Contact Form Phone: 541-737-6592 Hours of Operation: 8 a.m. - 5 p.m. Monday - Friday

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process.

What is a thesis? What distinguishes a thesis from a purpose? When composing, how can I best identify and express my thesis?

What is a thesis?

A thesis is

- an academic body of work

- a writer’s, speaker’s, or knowledge worker’s . . . main reason for communicating ; their purpose .

Related Concepts: Organizational Schema; Professional Writing Prose Style

Note: Some people consider thesis and purpose to be synonymous terms. Others view purpose to be a broader classification of discourse and thesis to be a more specific message or argument.

A writer’s thesis is the writer’s north star.

Writer’s, speaker’s, or knowledge worker’s . . . need to know their purpose , their reason for writing, in order to know how they need to compose their texts or submit those texts to their intended audiences .

A thesis may be expressed as

- an argumentative theses (Dietrich)

- an organizational theses

- a research question

While writers need to know what their purpose is for communicating in order to communicate clearly , concisely , and in a unified manner, they do not necessarily need to explicitly state their theses . In fact, there are some rhetorical circumstances when the tone and voice might be better served by leaving the context and purpose unsaid, implied, tacit.

Thesis Statements are commonplace in Workplace contexts. It is commonplace–especially in workplace writing–for writers, speakers, knowledge workers . . . to explicitly state their thesis in the first or second sentence of their texts. This sort of approach is sometimes called a Direct Style as opposed to an Indirect Style , or a Deductive Approach as opposed to an Inductive Approach .

Examples of genres of discourse that emploay a direct style include business correspondence, executive abstracts, abstracts, executive summaries, and introductions to workplace writing.

However, there are occasions when it’s rhetorically most strategic for a writer, speaker, knowledge worker . . . to view the context to be so routine that it goes without saying between the writer and the reader, the speaker and the audience.

What are the functions of a thesis?

The thesis functions in several important ways:

- It informs the reader of the paper’s direction

The thesis announces the direction of the paper’s conversation. Readers may find the paper’s position or argument more convincing if they know what to expect as they read.

- It places boundaries on the paper’s content

The body of the paper provides support for the thesis. Only evidence and details that relate directly to the paper’s main ideas should fall within the boundary established by the thesis.

- It determines how the content will be organized

The thesis summarizes the message or conclusion the reader is meant to understand and accept. A logical progression of these ideas and their supporting evidence helps shape the paper’s organization.

Recommended Reading

- The Thesis by Megan McIntyre

- Formulating a Thesis by Andrea Scott

- The Guiding Idea and Argumentative Thesis Statement by Rhonda Dietrich

Related Articles:

When is a thesis considered weak, suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

What is a weak thesis? How can a weak thesis be revised to make it stronger and more insightful? How should a thesis be developed?

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

What is Communication?

Cite this chapter.

- D. Brian Lewis M.Sc., Ph.D. 2 &

- D. Michael Gower M.Sc. 2

Part of the book series: Tertiary Level Biology ((TLB))

77 Accesses

1 Citations

In order to delimit the area under consideration, it is important at the outset to agree on a definition of the word communication . Many authors have found the phenomenon of communication very difficult to define, and most of the definitions are unsatisfactory because they have been either too restrictive or have allowed the inclusion of interactions which are not accepted as “proper” communication. For example, Wilson (1975) defines communication in terms of the altering, by one organism, of the probability pattern of behaviour in another organism, in a fashion adaptive to either one, or both, of the participants. His approach is essentially quantitative, and originates from the application of information theory to behavioural interactions. As a result, it allows us to investigate the communication process from an objective basis. Unfortunately, however, the definition also allows the inclusion of a diverse array of interactions (predator-prey, for example) that on other grounds are considered non-communicative. Certainly the predator receives information about the presence of the prey, but the prey can in no way be considered to communicate its existence and availability to the predator.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

City of London Polytechnic, UK

D. Brian Lewis M.Sc., Ph.D. ( Principal Lecturer in Neurobiology ) & D. Michael Gower M.Sc. ( Senior Lecturer in Animal Behaviour )

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1980 D. B. Lewis and D. M. Gower

About this chapter

Lewis, D.B., Gower, D.M. (1980). What is Communication?. In: Biology of Communication. Tertiary Level Biology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-3933-5_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-3933-5_1

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-0-216-90995-3

Online ISBN : 978-1-4613-3933-5

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- USF Research

- USF Libraries

Digital Commons @ USF > College of Arts and Sciences > Department of Communication > Theses and Dissertations

Communication Theses and Dissertations

Theses/dissertations from 2023 2023.

Consumer Purchase Intent in Opinion Leader Live Streaming , Jihong Huo

Organizing and Communicating Health: A Culture-centered and Necrocapitalist Inquiry of Groundwater Contamination in Rural West Bengal , Parameswari Mukherjee

HIV Stalks Bodies Like Mine: An Autoethnography of Self-Disclosure, Stigmatized Identity, and (In)Visibility in Queer Lived Experience , Steven Ryder

Theses/Dissertations from 2022 2022

Reviving the Christian Left: A Thematic Analysis of Progressive Christian Identity in American Politics , Adam Blake Arledge

Organizing Economies: Narrative Sensemaking and Communciative Resilience During Economic Disruption , Timothy Betts

The Tesla Brake Failure Protestor Scandal: A Case Study of Situational Crisis Communication Theory on Chinese Media , Jiajun Liu

Inflammatory Bowel Disease & Social (In)Visibility: An Interpretive Study of Food Choice, Self-Blame and Coping in Women Living with IBD , Jessica N. Lolli

Florida Punks: Punk, Performance, and Community at Gainesville’s Fest , Michael Anthony Mcdowell Ii

Re-centering and De-centering ‘Race’: an Analysis of Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing Organizational Websites , Beatriz Nieto-Fernandez

The Labors of Professional Wrestling: The Dream, the Drive, and Debility , Brooks Oglesby

Outside the Boundaries of Biomedicine: A Culture-Centered Approach to Female Patients Living Undiagnosed and Chronically Ill , Bianca Siegenthaler

The Effect of Racial and Ethnic Identity Salience on Online Political Expression and Political Participation in the United States , Jonathon Smith

Grey’s Anatomy and End of Life Ethics , Sean Micheal Swenson

Informal Communication, Sensemaking, and Relational Precarity: Constituting Resilience in Remote Work During COVID , Tanya R.M. Vomacka

Making a Way: An Auto/ethnographic Exploration of Narratives of Citizenship, Identity, (Un)Belonging and Home for Black Trinidadian[-]American Women , Anjuliet G. Woodruffe

Theses/Dissertations from 2021 2021

When I Rhyme It’s Sincerely Yours: Burkean Identification and Jay-Z’s Black Sincerity Rhetoric in the Post Soul Era , Antoine Francis Hardy

Explicating the Process of Communicative Disenfranchisement for Women with Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions (COPCs) , Elizabeth A. Hintz

Mitigating Negativity Bias in Media Selection , Gabrielle R. Jarmoszko

Blue Rage: A Critical Cultural Analysis of Policing, Whiteness, and Racial Surveillance , Wesley T. Johnson

Narratives of Success: How Honors College Newcomers Frame the Entrance to College , Cayla Lanier

Peminist Performance in/as Filipina Feminist Praxis: Collaging Stand-Up Comedy and the Narrative Points in Between , Christina-Marie A. Magalona

¿De dónde eres?: Negotiating identity as third culture kids , Sophia Margulies

The Rise of the "Gatecrashers": The Growing Impact of Athletes Breaking News on Mainstream Media through Social Media , Michael Nabors

Learning From The Seed: Illuminating Black Girlhood in Sustainable Living Paradigms , Toni Powell Powell Young

A Comparative Thematic Analysis of Newspaper Articles in France after the Bataclan and in the United States of America after Pulse , Simon Rousset

This is it: Latina/x Representation on One Day at a Time , Camille Ruiz Mangual

STOP- motion as theory, method, and praxis: ARRESTING moments of racialized gender in the academy , Sasha J. Sanders

Advice as Metadiscourse: On the gendering of women's leadership in advice-giving practices , Amaly Santiago

The Communicative Constitution of Environment: Land, Weather, Climate , Leanna K. Smithberger

Women Entrepreneurs in China: Dialectical Discourses, Situated Activities, and the (Re)production of Gender and Entrepreneurship , Zhenyu Tian

Theses/Dissertations from 2020 2020

Constructing a Neoliberal Youth Culture in Postcolonial Bangladeshi Advertising , Md Khorshed Alam

Communication, Learning and Social Support at the Speaking Center: A Communities of Practice Perspective , Ann Marie Foley Coats

A Visit to Cuba: Performance Ethnography of Place , Adolfo Lagomasino

Elemental Climate Disaster Texts and Queer Ecological Temporality , Laura Mattson

When the Beat Drops: Exploring Hip Hop, Home and Black Masculinity , Marquese Lamont McFerguson

Communication Skills in Medical Education: A Discourse Analysis of Simulated Patient Practices , Grace Ellen Peters

Hiding Under the Sun: Health, Access, and Discourses of Representation in Undocumented Communities , Jaime Shamado Robb

Theses/Dissertations from 2019 2019

Walking Each Other Home: Sensemaking of Illness Identity in an Online Metastatic Cancer Community , Ariane B. Anderson

Widow Narratives on Film and in Memoirs: Exploring Formula Stories of Grief and Loss of Older Women After the Death of a Spouse , Jennifer R. Bender

Life as a Reluctant Immigrant: An Autoethnographic Inquiry , Dionel Cotanda

“It’s A Broken System That’s Designed to Destroy”: A Critical Narrative Analysis of Healthcare Providers’ Stories About Race, Reproductive Health, and Policy , Brianna Rae Cusanno

Representations of Indian Christians in Bollywood Movies , Ryan A. D'souza

(re)Making Worlds Together: Rooster Teeth, Community, and Sites of Engagement , Andrea M. M. Fortin

In Another's Voice: Making Sense of Reproductive Health as Women of Color , Nivethitha Ketheeswaran

Communication as Constitutive of Organization: Practicing Collaboration in and English Language Program , Ariadne Miranda

Interrogating Homonationalism in Love, Simon , Jessica S. Rauchberg

Making Sense at the Margins: Describing Narratives on Food Insecurity Through Hip-hop , Lemuel Scott

Theses/Dissertations from 2018 2018

Telling a Rape Joke: Performing Humor in a Victim Help Center , Angela Mary Candela

Becoming a Woman of ISIS , Zoe D. Fine

The Uses of Community in Modern American Rhetoric , Cody Ryan Hawley

Opening Wounds and Possibilities: A Critical Examination of Violence and Monstrosity in Horror TV , Amanda K. Leblanc

As Good as it Gets: Redefining Survival through Post-Race and Post-Feminism in Apocalyptic Film and Television , Mark R. McCarthy

Managing a food health crisis: Perceptions and reactions to different response strategies , Yifei Ren

Everything is Fine: Self-Portrait of a Caregiver with Chronic Depression and Other Preexisting Conditions , Erin L. Scheffels

Lives on the (story)Line: Group Facilitation with Men in Recovery at The Salvation Army , Lisa Pia Zonni Spinazola

Theses/Dissertations from 2017 2017

Breach: Understanding the Mandatory Reporting of Title IX Violations as Pedagogy and Performance , Jacob G. Abraham

Documenting an Imperfect Past: Examining Tampa's Racial Integration through Community, Film, and Remembrance of Central Avenue , Travis R. Bell

Chemotherapy-Induced Alopecia and Quality-of-Life: Ovarian and Uterine Cancer Patients and the Aesthetics of Disease , Meredith L. Clements

Full-Time Teleworkers Sensemaking Process for Informal Communication , Sheila A. Gobes-Ryan

Volunteer Tourism: Fulfilling the Needs for God and Medicine in Latin America , Erin Howell

Practical Theology in an Interpretive Community: An Ethnography of Talk, Texts and Video in a Mediated Women's Bible Study , Nancie Hudson

Performing Narrative Medicine: Understanding Familial Chronic Illness through Performance , Alyse Keller

Second-Generation Bruja : Transforming Ancestral Shadows into Spiritual Activism , Lorraine E. Monteagut

The Rhetoric of Scientific Authority: A Rhetorical Examination of _An Inconvenient Truth_ , Alexander W. Morales

Daniel Bryan & The Negotiation of Kayfabe in Professional Wrestling , Brooks Oglesby

Improvising Close Relationships: A Relational Perspective on Vulnerability , Nicholas Riggs

Theses/Dissertations from 2016 2016

When Maps Ignore the Territory: An Examination of Gendered Language in Cancer Patient Literature , Joanna Bartell

From Portraits to Selfies: Family Photo-making Rituals , Krystal M. Bresnahan

Spiritual Frameworks in Pediatric Palliative Care: Understanding Parental Decision-making , Lindy Grief Davidson

Blue-Collar Scholars: Bridging Academic and Working-Class Worlds , Nathan Lee Hodges

The Communication Constitution of Law Enforcement in North Carolina’s Efforts Against Human Trafficking , Elizabeth Hampton Jeter

“Black Americans and HIV/AIDS in Popular Media” Conforming to The Politics of Respectability , Alisha Lynn Menzies

Selling the American Body: The Construction of American Identity Through the Slave Trade , Max W. Plumpton

In Search of Solidarity: Identification Participation in Virtual Fan Communities , Jaime Shamado Robb

Theses/Dissertations from 2015 2015

Straight Benevolence: Preserving Heterosexual Authority and White Privilege , Robb James Bruce

A Semiotic Phenomenology of Homelessness and the Precarious Community: A Matter of Boundary , Heather Renee Curry

Heart of the Beholder: The Pathos, Truths and Narratives of Thermopylae in _300_ , James Christopher Holcom

Was It Something They Said? Stand-up Comedy and Progressive Social Change , David M. Jenkins

The Meaning of Stories Without Meaning: A Post-Holocaust Experiment , Tori Chambers Lockler

Half Empty/Half Full: Absence, Ethnicity, and the Question of Identity in the United States , Ashley Josephine Martinez

Feeling at Home with Grief: An Ethnography of Continuing Bonds and Re-membering the Deceased , Blake Paxton

"In Heaven": Christian Couples' Experiences of Pregnancy Loss , Grace Ellen Peters

“You Better Redneckognize”: White Working-Class People and Reality Television , Tasha Rose Rennels

Designing Together with the World Café: Inviting Community Ideas for an Idea Zone in a Science Center , William Travis Thompson

Theses/Dissertations from 2014 2014

Crisis Communication: Sensemaking and Decision-making by the CDC Under Conditions of Uncertainty and Ambiguity During the 2009-2010 H1N1 Pandemic , Barbara Bennington

Communication as Yoga , Kristen Caroline Blinne

Love and (M)other (Im)possibilities , Summer Renee Cunningham

The Rhetoric of Corporate Identity: Corporate Social Responsibility, Creating Shared Value, and Globalization , Carolyn Day

"Is That What You Dream About? Being a Monster?": Bella Swan and the Construction of the Monstrous-Feminine in The Twilight Saga , Amanda Jayne Firestone

Organizing Disability: Producing Knowledge in a University Accommodations Office , Shelby Forbes

Emergency Medicine Triage as the Intersection of Storytelling, Decision-Making, and Dramaturgy , Colin Ainsworth Forde

Changing Landscapes: End-of-Life Care & Communication at a Zen Hospice , Ellen W. Klein

"We're Taking Slut Back": Analyzing Racialized Gender Politics in Chicago's 2012 Slutwalk March , Aphrodite Kocieda

Informing, Entertaining and Persuading: Health Communication at The Amazing You , David Haldane Lee

(Dis)Abled Gaming: An Autoethnographic Analysis of Decreasing Accessibility For Disabled Gamers , Kyle David Romano

Theses/Dissertations from 2013 2013

African Americans and Hospice: A Culture-Centered Exploration of Disparities in End-of-Life Care , Patrick Dillon

Polysemy, Plurality, & Paradigms: The Quixotic Quest for Commensurability of Ethics and Professionalism in the Practices of Law , Eric Paul Engel

Examining the Ontoepistemological Underpinnings of Diversity Education Found in Interpersonal Communication Textbooks , Tammy L. Jeffries

The 2008 Candlelight Protest in South Korea: Articulating the Paradox of Resistance in Neoliberal Globalization , Huikyong Pang

Compassionate Storytelling with Holocaust Survivors: Cultivating Dialogue at the End of an Era , Chris J. Patti

Advanced Search

- Email Notifications and RSS

- All Collections

- USF Faculty Publications

- Open Access Journals

- Conferences and Events

- Theses and Dissertations

- Textbooks Collection

Useful Links

- Department of Communication

- Rights Information

- SelectedWorks

- Submit Research

Home | About | Help | My Account | Accessibility Statement | Language and Diversity Statements

Privacy Copyright

Scholars' Bank

Dance as communication: how humans communicate through dance and perceive dance as communication, description:.

Show full item record

Files in this item

This item appears in the following Collection(s)

- Clark Honors College Theses [1306]

Related items

Showing items related by title, author, creator and subject.

- Consuming Justice: Exploring Tensions Between Environmental Justice and Technology Consumption Through Media Coverage of Electronic Waste, 2002-2013 Wolf-Monteiro, Brenna ( University of Oregon , 2017-09-06 ) The social and environmental impacts of consumer electronics and information communications technologies (CE/ICTs) reflect dynamics of a globalized and interdependent world. During the early 21st century the global consumption ...

- Moving from cantaleta to encanto or challenging the modernization posture in communication for development and social change: A Colombian case study of the everyday work of development communicators Porras, Estella ( University of Oregon , 2008-09 ) The field of international development communication has given scant attention to the role of communication practitioners who are critical players in facilitating participation and community engagement in development. ...

- Saving Polar Bears in the Heartland? Using Framing Theory to Create Regional Environmental Communications Lewman, Hannah Hope ( University of Oregon , 2018-06 ) Despite the overwhelming evidence for anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change, a significant portion of the American public remains unconvinced. This disconnect between scientific certainty and public skepticism calls ...

Search Scholars' Bank

All of scholars' bank.

- By Issue Date

This Collection

- Most Popular Items

- Statistics by Country

- Most Popular Authors

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Topic, Purpose, and Thesis. Before any work can be done on crafting the body of your speech or presentation, you must first do some prep work—selecting a topic, formulating a purpose statement, and crafting a thesis statement. In doing so, you lay the foundation for your speech by making important decisions about what you will speak about ...

The thesis is not a question. Blatant. A speech thesis is more blunt and obvious than what we might use in writing. Identifies the parameters of the speech. It tells the audience what the speaker will be doing; which, by definition, also tells the audience what the speaker is not doing. Consistent with the speaker's overall speech purpose. The ...

Main ideas and supporting details have a pretty simple relationship. The main idea is the center of attention, and the supporting details function to support the main idea. If these were two people, this would be a pretty unfair relationship, but in writing or speaking, it is entirely acceptable. After all, only one idea can be the 'focus.'.

Ultimately you want your thesis to be correct (including a topic and direction or claim), but you also want it to contain insightful, provocative ideas with regard to the topic; in other words, work to construct a thesis that expresses a more intriguing insight than the predictable application of theory or concept to routine communication ...

A thesis is an in-depth research study that identifies a particular topic of inquiry and presents a clear argument or perspective about that topic using evidence and logic. Writing a thesis showcases your ability of critical thinking, gathering evidence, and making a compelling argument. Integral to these competencies is thorough research ...

Revised on April 16, 2024. A thesis is a type of research paper based on your original research. It is usually submitted as the final step of a master's program or a capstone to a bachelor's degree. Writing a thesis can be a daunting experience. Other than a dissertation, it is one of the longest pieces of writing students typically complete.

A thesis statement: tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion. is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper. directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself.

A thesis is. an academic body of work. a writer's, speaker's, or knowledge worker's . . . main reason for communicating; their purpose. Related Concepts: Organizational Schema; Professional Writing Prose Style. Note: Some people consider thesis and purpose to be synonymous terms.

Writing a good thesis statement on effective communication involves communicating your motive in a statement of original and significant thought. The purpose you indicate in your thesis statement is the paper's main point -- insight, argument or point of view -- backed up by compelling research evidence. An ...

Step 2: Write your initial answer. After some initial research, you can formulate a tentative answer to this question. At this stage it can be simple, and it should guide the research process and writing process. The internet has had more of a positive than a negative effect on education.

achieve a definition, at once comprehensive and specific, of a term so widely used (and misused). Yet some formal working definition is necessary for the development of the thesis of this book. Accordingly, we define communication as the transmission of a signal or signals between two

This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Mastering the Art of Interpersonal Communication: A Qualitative Study on How Individuals Become Masters of Interpersonal Communication. by. Jessica Renney B.A., University of Lethbridge, 2007. Supervisory Committee.

Effective management communication. includes the process of observation, analysis, strategy, development, organization, and the. implementation and evaluation of communication processes (Reyes, 2012). A manager's communication style is part of an organizational learning process that can.

as the activity or process of expressing ideas and feelings or of giving people information. One can safely say that communication is the act of transferring information and messages. from one ...

Because communication is an integral part of the field and the purpose of communication is essential to the concept of strategic communication, we should consider communication as the pillar on which the field rests. However, what is fundamentally meant by "communication" remains rather unclear, as do the metatheories or lenses through ...

Political Communication. Post-truth (PT) is a periodizing concept (Green, 1995; Besserman, 1998) that refers to a historically particular public anxiety about public truth claims and authority to be a legitimate public truth-teller. However, the term is potentially misleading for at least two major reasons.

Studies: Business Communication Master Thesis Communication Styles at Work Influencing Factors on Self- and Other-Concerned Communication Style Deposed by Nicole Schlegel, B.A Date of birth: June 10, 1990 Student number: 12-208-021 Mail address: [email protected] In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (M.A.)

Communication is the process of transmitting information and common understanding from one person to another. Communication in the workplace is critical to establishing and maintaining quality ...

Abstract. The term "political communication" refers to both a set of professional practices and a multidisciplinary field of study focusing on the interaction between the political, media, and ...

Theses/Dissertations from 2020. PDF. Constructing a Neoliberal Youth Culture in Postcolonial Bangladeshi Advertising, Md Khorshed Alam. PDF. Communication, Learning and Social Support at the Speaking Center: A Communities of Practice Perspective, Ann Marie Foley Coats. PDF.

Communication channels are the methods and techniques used to send messages, like the telephone, letters, reports, meetings, or the Internet. People choose between communication channels for numerous reasons, such as heuristics, ease of use, experience, or simple preference, and the communication channel may contribute to the

definition for dance that works well for this thesis which embraces the focus of how dance serves as a means of communication. Since dance involves gesture, defining "gesture" becomes the first step in developing a working definition of dance. Susanne K. Langer in What ls Dance? refers to "gesture" as "vital movement" and suggests that

This thesis will acknowledge the concept of dance as a means of communication in order to prove that dance is pervasive and vital in its presence in human societies throughout the world. As a means of communication, dance is used to lure and keep mates; define and perpetuate gender roles; form and cultivate social and cultural bonds; and even ...