Uncovering a Mystery: Making a Hypothesis

Students will imagine what it might be like to be an art historian or art collector by hypothesizing possible uses of a discovered wooden leg in a descriptive journal entry.

Students will be able to:

- describe activities and challenges of being an art historian or art collector;

- hypothesize possible original use(s) of the wooden Leg ; and

- create a written or illustrated journal entry from an art collector’s perspective that includes realistic, descriptive details.

- Warm-up: Give each student three copies of the handout that shows the shape of a leg. Have students design a background scene for the leg. Encourage them to be creative—they might want to draw the rest of a human being, turn the leg into a lamp, or create something new! Give them 2–3 minutes for each handout.

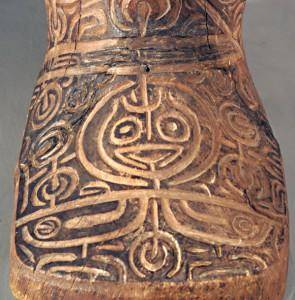

- Display the Polynesian Leg and ask students to look at it closely. Start by having them describe what they see.

- Have them brainstorm as a class what the Leg might have been used for. No idea is stupid! When they think they have exhausted the possibilities, encourage them to come up with three more ideas.

- Explain to students that archaeologists and art historians often have a general idea about what particular art objects were used for, but many times they do not know for certain. Even the Denver Art Museum isn’t sure why each piece of art was created!

- Have students pretend that they are art collectors who discover this wooden Leg in the Marquesas Islands. For older students, have them write a journal entry about the day they discover the Leg . Their entries should provide realistic, descriptive details that address “who, what, when, where, why, and how” questions. The students should also include some possible ideas about what the wooden Leg was originally used for and their reasons for thinking this way. Which possible use for the wooden Leg is the most likely given the relevant evidence?

- For younger students (and if time allows for older students), have them draw pictures in their journals of the Leg , illustrating different ways it might have been used.

- Encourage students to share their final writing pieces or show their drawings in small groups. Have students share one positive comment and one recommendation for improvement for each piece. You may want to make this a special occasion by bringing in snacks and hosting a writer’s breakfast or tea.

- Lined paper and pen/pencil for each student

- Handout with drawing of Leg , three copies for each student

- About the Art section on the Polynesian Leg

- One color copy of the Leg for every four students, or the ability to project the image onto a wall or screen

- Observe and Learn to Comprehend

- Relate and Connect to Transfer

- Oral Expression and Listening

- Research and Reasoning

- Writing and Composition

- Reading for All Purposes

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Information Literacy

- Self-Direction

Height: 22.625 in; Width: 5.38 in; Length of Foot: 7.75 in.

Native arts acquisition funds, 1948.795

Photograph © Denver Art Museum 2009. All Rights Reserved.

This wooden leg was carved by an artist from the Marquesas [mar-KAY-zas] Islands, a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, located in the Pacific Ocean. The Marquesas are the farthest group of islands from any continent. In terms of the arts, they are well-known for their tattoo art, as well as for their carvings in wood, bone, and shell. The process of tattooing in the Marquesas was treated as a ritual and the tattoo artist was a highly skilled artisan. Even today, many Marquesans beautify their bodies, proclaim their identities, and preserve their memories and experiences with tattoos.

We’re not sure why this particular object was created. It’s possible that it served as the leg for a specially constructed raised bed, made only for certain priests to lie on following the performance of important sacrifices. Tattoos were believed to protect a person’s body from harm and this belief applied to objects as well. Tattooing the bed’s leg may have served to protect these priests’ tapu , or sacred, state by preventing contact with the earth. This leg may also have been a model placed outside of a tattoo shop, advertising the services of the artist inside.

In the past, tattooing was a major art form in the Marquesas Islands and it inevitably influenced other art forms. The tattooing style of the Marquesas was the most elaborate in all of Polynesia. Tattoo images were marks of beauty as well as a reflection of knowledge and cultural beliefs. They also signaled a person’s social status—a higher ranking individual would have more tattoos than an individual of a lesser rank. All-over tattooing was a development unique to this area. Both males and females were tattooed, although only men covered their bodies from head to toe. Designs were also different for women and men.

Tattoo Imagery

Tattoo images have been carved all around the circumference of the wooden leg. The carving is particularly detailed on the foot.

The large crack down the front of the leg happened before the leg came into the Denver Art Museum’s possession. It is evidence of curing of the wood as it aged.

The peg, or wooden block at the top of the leg tells us that it may have been attached to something else.

Related Creativity Resources

Communication Through Clothing

In this lesson, students will explore the symbols, patterns, and colors that are important to the Osage people. Students will create a t-shirt design that expresses information about their own culture and personality, and reflect upon messages communicated by their clothing design.

Say It with Flowers

Students will examine the artistic characteristics of Three Young Girls ; explain the meaning and significance of the flowers in the painting and other well-known flowers.

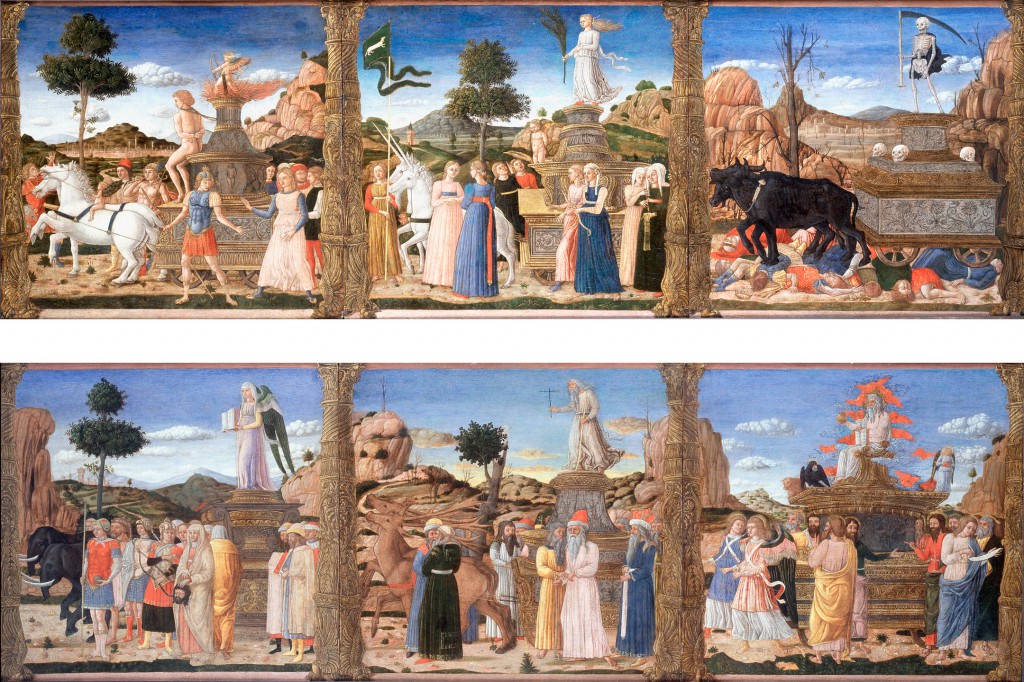

A Triumphant Message

Students will examine the sequencing of events in the paintings and create a six-part story of sequential “triumphs” that ends with an important message.

Poetry with Natural Similes and Metaphors

Students will examine the artistic characteristics of Summer ; make comparisons between physical features of the figure portrayed in Summer with items from the natural world; and create poems using similes and metaphors comparing a person’s physical appearance with items from the natural world.

Making the Commonplace Distinguished and Beautiful

Students will learn how William Merritt Chase aimed to portray commonplace objects in ways that made them appear distinguished and beautiful. They will then create a written description of a commonplace object that makes it appear distinguished and beautiful.

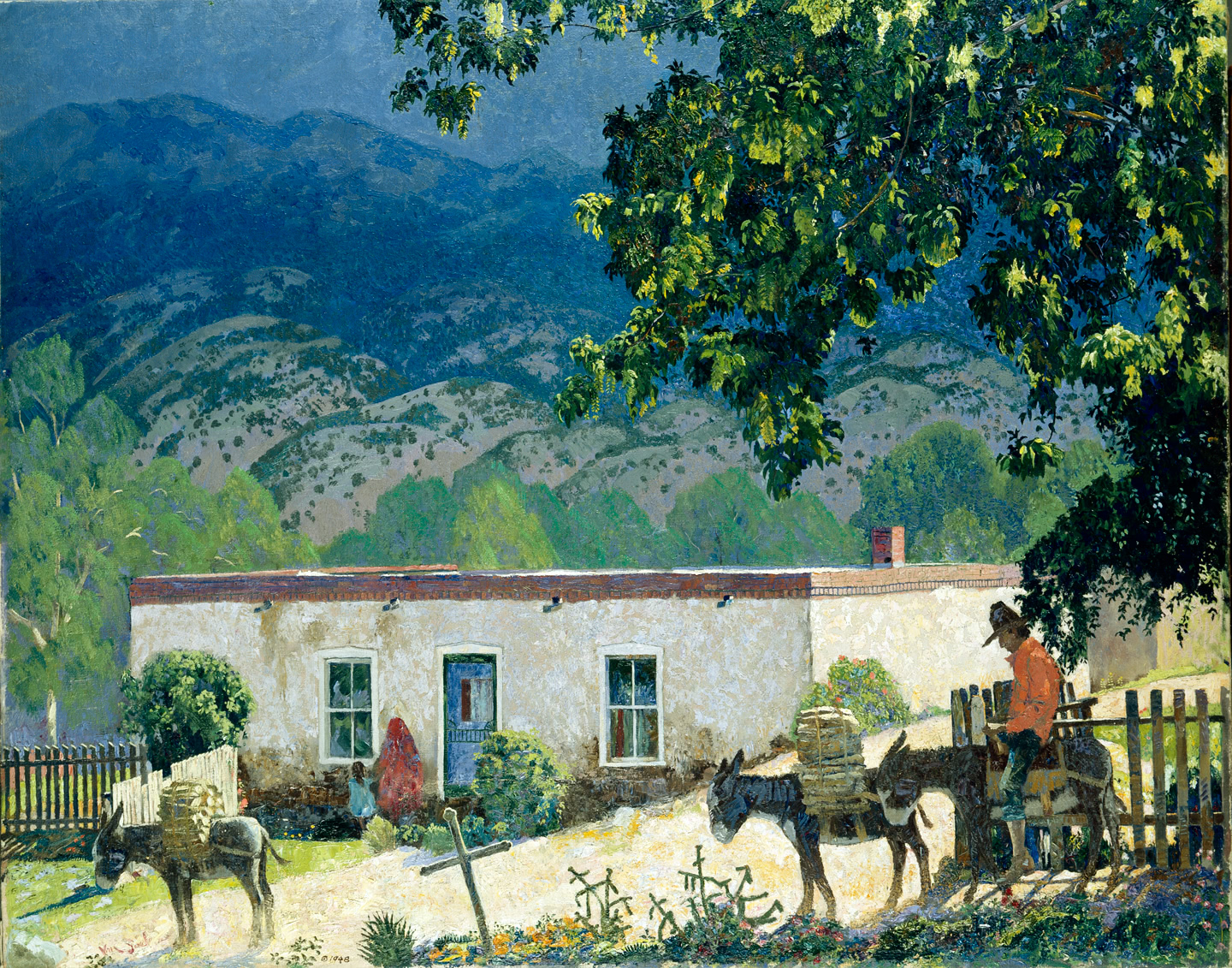

Beyond First Impressions

Students will examine the visual tools used in the painting Road to Santa Fe and how those tools help the painter tell a particular story. They will then use the painting to explore storytelling and use brainstorming strategies to enrich the content and voice of stories they will write. Multiple drafts and peer-editing will help teach students how working and reworking a piece, much like painters do when planning a painting, will strengthen their finished product.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.

Why Did Prehistoric People Draw in the Caves?

Rock art remains one of the last mysteries of humanity, grotte chauvet - unesco world heritage site.

The secret of natural history Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

How were prehistoric humans represented in the 19th century?

We have known about prehistoric humans for a long time and the Cro-Magnon Man was identified as early as 1868 by Louis Lartet in Dordogne. The first discovery of Neanderthals was even earlier in 1829 in Belgium. In 1856, bones were found in a small cave in the Neander Valley in Germany. All these fossils have since been known as "wild men."

Replica of Chabot Cave (2018/2018) by Thierry Allard Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

The discovery of Paleolithic rock art

Paleolithic rock art was identified shortly after these first paleoanthropological discoveries in 1875 in Altamira, Spain and in 1879 in the Chabot Cave in the Ardèche Valley. Since then, several hypotheses explaining the motivations of our ancestors have been discovered.

Return of a bear hunt - Age of polished stone (1884/1884) by F. Cormon Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

Art for art's sake

This hypothesis suggests that prehistoric humans painted, drew, engraved, or carved for strictly aesthetic reasons in order to represent beauty. However, all the parietal figures, during the 30,000 years that this practice lasted in Europe, do not have the same aesthetic quality.

Megaceros Gallery (Chauvet Cave) by J. Clottes Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

On the other hand, most of the parietal representations found are located in caves (those that may have existed outside may have been destroyed). And so why represent beauty if it is not shared and is hidden in the darkness of deep caves?

Rousseau (1755), "Discourse on Inequality" and the invention of the idea of the noble savage (1755/1755) by J.-J. rousseau (1712-1778) Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

This assumption of art for art's sake was inspired by the myth of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's "noble savage." It was also used to convey anticlerical ideas.

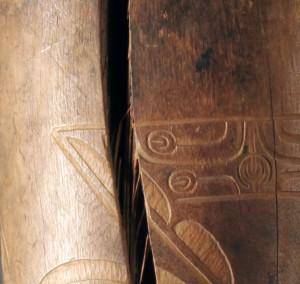

Totems, Original 'Namgis Burial Grounds by R. Parker Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

This hypothesis suggests that each clan or human group is represented by a symbolic animal, its totem, a being possibly worshiped for the protection it brings and the ancestral heritage it embodies.

Red steppe bison in the Altamira cave (Spain) (2003/2003) by J. Clottes Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

If this hypothesis were universally applicable, we would see disparities in Europe. However, European Paleolithic parietal art exhibits a certain symbolic homogeneity with persistence of the same animal species represented. In fact, there are few animal species that were shared and reproduced for thousands of years in very diverse geographical areas. Reindeer, bison, and horses were animals that were very often depicted.

Steppe bison in the Cave of Niaux (France) (1990/1990) by Jean Clottes Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

Finally, animals are represented pierced with arrows, a symbol that cannot be reconciled with the 'worship' that was to be given to them if these effigies were well and truly adored by our ancestors.

Abbé Breuil in front of Lascaux's entrance Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

The magic hunt

Abbé Breuil (1877-1961) and Henri Begouën (1863-1956) repeated the hypothesis of "prescience magic," suggesting that prehistoric humans attempted to influence the result of their hunt by drawing it in caves.

Abbot Breuil in the cave of Lascaux faces the panel of the Unicorn. (1940/1940) Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

For Abbé Breuil it was more acceptable to allude to magical practice rather than spirituality, which could have steered the discussion towards religious issues.

A piece from the panel of the so-called "Chinese horses" (Lascaux) (1990/1990) by Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

However, the correlation between animal species pierced by arrows and archeological excavations is tenuous. The representations of these animals symbolized with arrows piercing them, besides being few in number in all of European parietal art, has little correspondence to the archeological remains found. The hypothesis of sympathetic magic has been abandoned.

André Leroi-Gourhan (1911-1986) in the Rouffignac cave (Dordogne) by unknown Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

Structuralism

André Leroi-Gourhan (1911-1896) proposed a statistical approach to parietal art. He was hoping to identify a structure within a painting cave. He proposed a spatial approach to adorned caves involving central and marginal symbolic figures. According to Leroi-Gourhan, the most important would be the male/female duality, especially embodied by the auroch-bison association on the one hand, and horses on the other.

Ideal layout of a paleolithic sanctuary after André Leroi-Gourhan. (1965/1965) by A. Leroi-Gourhan Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

This statistical approach has never been scientifically demonstrated despite the influence it had on university education.

Jean Clottes (2015/2015) by Roland KADRINI Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

According to Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams, who decided to re-introduce the shamanic hypothesis advanced by the Romanian historian Mircea Eliade (1907-1986), the figures drawn in the caves would be some representations of visions acquired during a trance-like or near-trance state.

Yakout shaman (1983/1983) Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

In particular, this hypothesis is based on ethnological observations made with groups of modern-day hunter-gatherers. It is also based on the perception of entoptic signs (points, lines, grids, etc.) whose source is the eye itself. These optical phenomena can be caused by the inhalation of products or substances contained in the materials used to make parietal figures (charcoal, ocher). These spontaneous entoptic signs can also be the symptoms of migraines (flashing lights and zig-zag patterns, for example).

Diversity of tectiform signs (2013/2013) by Alain Roussot Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

Although not well received, this hypothesis is not intended to be a global and exclusive explanation but proposes an explanatory framework. Numerous testimonies by speleologists attest to the hallucinogenic character of the caves, where cold, humidity, darkness, and the absence of sensory cues facilitate optical and auditory hallucinations. Thus the caves could have a dual role with fundamentally related aspects: facilitating hallucinatory visions and coming into contact with spirits through the wall.

Chuka dance in the tent of a chef (1868/1868) by Lanoye, F. de (Ferdinand), 1810-1870 Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

Jean Clottes clarifies his hypothesis (2004): "Paintings made in the middle of a large chamber will probably have a meaning quite different from those found in the depths of a narrow diverticulum where only one person could slip through. The latter can be related […] to either the search for visions or the desire to go as far as possible to the bottom of the earth. Spectacular paintings in large spaces could, however, have a didactic and educational role, and serve as the foundation of ceremonies and rituals."

Philippe Descola, anthropologist (Collège de France) (2014/2014) by Cl. Truong-Ngoc Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

The absence of words

According to the anthropologist Philippe Descola (Collège de France), the people of the Chauvet Cave would have been more comfortable using images instead of words to express complex thoughts. In advancing this idea, we can indeed imagine that these people were incapable of naming objects they would have drawn. Perhaps we can also imagine the existence of taboos whereby it was essential to depict things in the drawing without naming them.

Prehistoric Art (2013/2013) by SMERGC / MQB Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

This videos explores the discovery of prehistoric art at the beginning of the 20th century, where several theories have emerged to explain why our ancestors painted in caves. Totemism (where each drawing represented the animal protecting the tribe) was favored but archeological findings and the science of ethnology paved the way for the "sympathical magic" theory of Abbé Breuil. According to him, drawing animals is a way to kill them symbolically before the hunt. Starting from the 1950s, structuralism gained traction, which associates drawings with symbols. In 1994, the discovery of Chauvet was a shock, as no prehistorian thought humans 36, 000 years ago could create such art.

Chauvet Cave Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

The testimony of the Chauvet Cave

The rock art of the Chauvet Cave has the same typology of signs as those observed in other adorned European caves: animal, geometric, and anthropomorphic representations (handprints, the lower body, and the female body), with the latter being the fewest in number.

Central Piece of the Feline Fresco (Chauvet Cave, Ardèche) (2018-08-02/2018-08-02) by L. Guichard/Perazio/Smergc Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

The bestiary of the Chauvet Cave is distinguished by the abundance of animals at the top of the food chain: big cats (the most numerous), mammoths, and woolly rhinos, animals not hunted or infrequently hunted by men, except opportunistically.

Cave bear skull on a rock (Chauvet cave) (2006/2006) by L. Guichard Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

For Jean Clottes, the Chauvet Cave is a space that fosters contact between the real world and spirit world. He even suggested that the cave bear played the role of the mediator. Indeed, the Chauvet Cave is a subterranean space heavily frequented by this animal. However, many recesses around the Chauvet Cave are equally large and accessible, and none of them was chosen by the Palaeolithic people. Only the Chauvet Cave, frequently visited by cave bears, was occupied and adorned by people.

Horses panel (Chauvet cave) (2006/2006) by L. Guichard Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

In conclusion, there is still no way of translating rock art. Cave art is a symbolic representation of codes produced by Palaeolithic human thinking. Although this cannot be a definitive conclusion, we can say that parietal art symbolizes the fusion of the Palaeolithic human and animal worlds, whereas today we perceive these two entities as dissociated from each other. In parietal art, man is symbolically represented and present in animal representations.

The Syndicat mixte de l'Espace de restitution de la grotte Chauvet (Public Union to manage the Chauvet Cave/SMERGC) thanks the Ministry of Culture and Communication. This exhibition was created as part of an agreement linking these two partners to promote the Chauvet Cave and its geographical and historical context. SMERGC is the designer, developer and owner of the La Grotte Chauvet 2 site (formerly known as Caverne du Pont d'Arc). It prepared and defended the application package of the Chauvet Cave for inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List. http://lacavernedupontdarc.org/ https://www.facebook.com/lagrottechauvet2/ SMERGC also thanks Google Arts & Culture.

The Bear Hollow Chamber

The skull chamber and the lattices gallery, the end chamber, the candle chamber, chauvet cave: the first known masterpiece of humanity, the brunel room, the hillaire chamber, the red panels gallery, the megaloceros gallery, meet the people of the chauvet cave.

The Art of Realism

What’s real? See for yourself how five artists represent the reality of their – or other – worlds.

Idea One: The Delight of Deception

Has a painting ever played tricks on your eyes?

When art looks really real, it is called _trompe l’oeil_, a French term meaning “fool the eye.” This Christian painting of Mary and baby Jesus contains a great example of _trompe l’oeil_: check out the fly near the foot of Mary’s throne. It looks so real, it’s tempting to brush it off the canvas!

How do you think the artist created this effect using paint?

Nicola di Maestro Antonio carefully selected his colors to create texture. He used perspective, a method of combining lines to create the illusion of depth, and also carefully painted shadows to give the figures a 3-D effect. Artists like di Antonio enjoyed painting beautiful pictures that viewers could experience both visually and emotionally. They believed people could feel more connected to paintings that looked realistic.

Di Antonio painted during the early Renaissance, a period of cultural rebirth in Europe. European artists began to use ancient Greek and Roman art as inspiration for their own artwork. They liked how ancient artists portrayed natural-looking people and objects. Even though figures were often idealized, they were dramatic, emotional, and humanlike.

The still life at the bottom of this painting may look realistic, but it also contains hidden meanings. Renaissance artists often put symbols, or iconography, into their art. The fly stands for evil, while the gourds stand for its antidote. The coral necklace around baby Jesus’s neck was a charm against evil.

This painting is an allegory, containing symbols that have deeper meanings. The pots and pans represent the four elements: fire, water, earth, and air.

This etching was inspired by Magritte’s earlier painting, La Trahison des images, which featured a realistic-looking pipe and a caption that read “This is not a pipe.” Magritte reminds the viewer that, no matter how realistic an image looks, it’s not actually real.

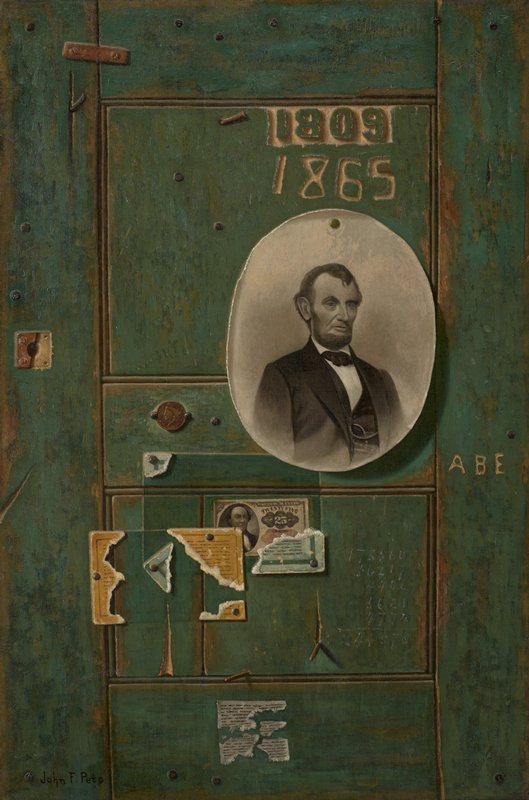

John Frederick Peto was skilled at painting _trompe l’oeil_ illusions. It’s hard to believe this is a painting—not a carved door.

Idea Two: How Real?

Gustave Courbet painted this scene of the French countryside during a period in which people in France expected art to depict a perfect world, much prettier than the one they lived in. But Courbet believed that art should be truthful and depict the actual world, dirt and all. Courbet called himself a “painter of the real,” vowing only to paint what he could see. He believed that art had the power to teach people lessons, or even criticize society.

This painting is of Ornans, the town where Courbet grew up. On the surface the scene is serene. But it also has a revolutionary hidden meaning. The houses on the hill sit atop the ruins of an old castle destroyed by the French government in the 1600s to prevent the provinces from organizing together to take power away from the monarchy. The village built on the ruins represents how the peasants of Courbet’s time were able to thrive over past oppression. Courbet celebrated the everyday lives of the working class in his art; he shows a woman doing laundry in the foreground of this picture.

Courbet’s painting not only depicts the real world, but it also actually includes it. Look closely at the painting. How would you describe the texture?

If it looks gritty and bumpy, it’s because Courbet actually mixed his paint with dirt from the valley. By mixing in dirt, he made the painting that much more real. In fact, his painting style offended the art critics because it was so unrefined. The ruggedness of the painted surface reflects the tough lives of the peasants. The dirt also reminds us of nature’s power in connecting our past, present, and future.

Winslow Homer was an American painter who depicted the world as he saw it. While Realism was a controversial movement in France, it was a traditional style for American artists. Paintings like this one allowed Americans to see worlds about which they may never have known.

The Ife (ee-fay) culture of Nigeria had a rich tradition of realist sculpture dating back to 1050 CE. Portrait heads like this one show careful attention to the details of facial features, including the pattern of scarification.

This closeup shows just how gritty the texture of this painting really is.

Gustave Courbet, French, 1819–77. _Chateau d’Ornans_ (detail), 1855. Oil on canvas. The John R. Van Derlip Fund and the William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

Idea Three: Artistic Role Playing

What seems to be going on in this picture?

This Japanese woodblock print is called a mitate. Mitate are visual puns or similes. They depict scenes from famous stories, plays, or parables, but with a twist: the artist often placed famous people, iconic settings, or beautiful women into the scene, creating a fantasy print that still contained elements of reality. Because mitate often referenced theater, literature, or religious stories, they were a sort of intellectual game. Viewers enjoyed identifying the people and stories in the prints.

One of the most popular types of mitate depicted beautiful women playing the roles of men from famous plays or stories. This image, created by Suzuki Harunobu, an artist who specialized in mitate, shows a scene from a well-known play from the no theatre called Hachi-no-ki (Potted Tree). The play is about an impoverished samurai who offered to burn his last three bonsai trees to keep a traveling monk warm on a cold winter night. The monk, who was really a government official in disguise, was so pleased with the samurai’s sacrifice that he rewarded the samurai with three tracts of land. Each piece of land was named for the sacrificed trees: pine, plum, and cherry. In this print, Harunobu replaces the poor samurai with a well-dressed, charming woman. She is about to daintily chop into the first tree.

Even though this print is a fantasy, Harunobu made it look believable. Describe the visual elements and details he included to make the scene look so real to his audience. For example, think about the props, sense of space, and the setting.

This is a photographic reenactment of Spanish painter Francisco de Goya’s etching, _The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters_. Yinka Shonibare substituted a real person wearing colorful Dutch wax cotton for Goya’s original figure. Yinka Shonibare, English, born 1962. _The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Australia)_, 2008. Chromogenic print mounted on aluminum. The C. Curtis Dunnavan Fund for Contemporary Art. © Yinka Shonibare, courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York.

Yasumasa Morimura recreates famous portraits using his own face and body as the subject. Here, he stands in for the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. He wears fabric designed by Louis Vuitton and a Japanese-style hair ornament.

Idea Four: Re-presenting Art: Copies and Reproductions

This portrait of George Washington is actually a copy of Gilbert Stuart’s iconic _Landsdowne Portrait_, originally completed in 1796. Stuart’s portrait of Washington proved so popular, many banks, civic buildings, and museums requested copies of the painting. With Stuart’s permission, Thomas Sully began painting replicas because Stuart could not fill the orders by himself.

Both Stuart’s and Sully’s portraits depict Washington as a hero. Washington, the nation’s first president, helped unify and lead the new country, even in the face of political disagreements and foreign threats. Both paintings show Washington’s strong nature through his physical stance, in addition to subtle icons; his sword, for instance, represents his military background, while his simple black suit shows him to be one of “the people,” instead of a privileged and out-of-touch monarch.

The two portraits are very similar, but not exact. While Stuart’s portrait shows Washington holding out his hand, Sully placed Washington’s hand on the Constitution, symbolizing his connection to this important document.

Compare Sully’s portrait to the original painting at the National Gallery to see what other differences you can find.

Do you think Sully’s copy of Stuart’s painting has its own artistic value? Why or why not?

Is this copy worthy of being in a museum? What makes you say that?

Do you think this painting is important because it re-presents an iconic painting, or does it have merit on its own as a well-produced artwork?

This is essentially a miniature museum of selected works by artist Marcel Duchamp. Beginning in 1936, Duchamp began making miniature reproductions of his own artwork. He made 350 of these miniature museums. Marcel Duchamp, American (born France), 1887–1968. _Boite-en-Valise_ (Box in a suitcase), conceived 1936–1941; assembled 1961. Linen-covered box containing mixed media assemblage/collage of miniature replicas, photographs, and color reproductions of works by Duchamp. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Estate of Marcel Duchamp.

Idea Five: Realism out of this World

In China, during the Eastern Han dynasty (25 BCE–220 CE), it was customary for people to furnish the tombs of loved ones with ceramic figures, called ming-ch’i, that depicted everyday people, places, and things from the living world. The idea was to recreate the comfort and familiarity of this world in the afterlife. They believed that the contents of the tomb should reflect the deceased’s life so he or she could continue living comfortably in the afterlife.

Ming-ch’i grew even more popular during the T’ang dynasty (7th–8th century CE) when funerals became extravagant festivals. In 742 CE, the government issued an edict that established how many ming-ch’i people could place in tombs. The number and quality corresponded to a person’s social rank and wealth. While notable people were allowed up to 70 pieces, commoners were only allowed about 15.

The person who crafted this model included realistic details of an actual Chinese style pigsty, including piglets, feeding containers—even toilets (located under the roof)!

Look closely at the scene. Describe the everyday details that you see. What can you learn about ancient Chinese culture from this artistic interpretation? What kind of person do you think this set was created for? What makes you say that?

This boat was placed in an Egyptian noble’s tomb to help transport his or her soul to the next life. It is a miniature replica of the boats Egyptians used for fishing and transportation in their daily lives. Egypt, Model Boat and Figures, Middle Kingdom (22nd–18th century BCE). Polychromed wood. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

Ceramic figurines, called haniwa, accompanied deceased Japanese aristocrats in their tombs. They may have been thought to provide protection, comfort, and service in the afterlife. Notice the realistic details of her necklace, hairdo, and medicine bag. Japan (Kofun), Haniwa Figure, 6th century. Earthenware. The Christina N. and Swan J. Turnblad Memorial Fund.

Moche, Peru, Andean Region. Vessel, ceramic, pigment, 1st–2nd century. William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

An ancient Peruvian civilization called Moche created pottery that faithfully reflected everyday life, such as this prominent couple feasting on seafood. Vessels like this would have accompanied elite people to their tombs, carrying on their status and serving in the afterlife.

Related Activities

Hidden messages.

An allegory is a creative way of expressing a hidden meaning, like a code. Allegories are often communicated through realistic and familiar images. For instance, sometimes movies use rain to symbolize sadness. Create your own allegory. Be creative—you can write, draw, or even build an allegory out of found objects. Ask your friends and family if they can figure out the meaning of your allegory.

It’s your (casting) call

Who would you like to see playing a character from your favorite story, movie, or even artwork? Create a drawing, poster, or woodblock-style print in which you substitute a friend, family member, pet, or cartoon character for this character. Use your imagination! Sponge Bob could become Cinderella, or your best friend could become Spider Man!

Discussion: Grounding Fantasy in Reality

What is it that makes a fantasy more believable? Think about movies like _Harry Potter_ and _The Avengers_. What do movies need to include in order to be considered believable? Why do you think they need to include these elements? Do you think cartoons can be believable? Why or why not?

Tombs and Time Capsules

Ancient tombs are like time capsules; they preserve some of the most important objects—including artwork—from the past. Such objects teach us a lot about the everyday lives and beliefs of ancient people. Design your own time capsule by drawing or crafting your objects from clay. What objects would you include to represent the important things in your life? Why did you include these objects? What might they say to future people about who you are and how you lived?

Fact vs. fiction

Pretend you’re an archaeologist. Use the search function on Mia’s website or visit the museum in person to create a “collection” of 3-5 objects from the same culture. Try to learn as much as you can about the works, then write a history about them. Talk about who created them, who may have used them, how they were used, when they were made, and what they are. But here’s the twist: Invent fake stories for 1-2 of the objects. Then present to your class, and see if your classmates can tell fact from fiction. Discuss as a class: Can you always believe what you hear? How do you separate fact from fiction? Why is this an important skill to have?

Realism for sale!

Advertisers often use realistic-looking, yet idealized, images to convince people to buy their products. Pick three advertisements in different media (television, magazines, websites, billboards, etc.) that use realistic images. Write a description for each ad. Then write a response to the following statements: 1.This advertising image is realistic because. . . 2.This advertising image is unrealistic because . . . 3.Write whether you believe the ad will be successful at selling the product. Be sure to explain why or why not. Then discuss your essay with your classmates.

- Researching

- 7. Hypothesis

How to write a hypothesis

Once you have created your three topic sentences , you are ready to create your hypothesis.

What is a 'hypothesis'?

A hypothesis is a single sentence answer to the Key Inquiry Question that clearly states what your entire essay is going to argue.

It contains both the argument and the main reasons in support of your argument. Each hypothesis should clearly state the ‘answer’ to the question, followed by a ‘why’.

For Example:

The Indigenous people of Australia were treated as second-class citizens until the 1960’s (answer) by the denial of basic political rights by State and Federal governments (why) .

How do you create a hypothesis?

Back in Step 3 of the research process, you split your Key Inquiry Question into three sub-questions .

Then at Step 6 you used the quotes from your Source Research to create answers to each of the sub-questions. These answers became your three Topic Sentences .

To create your hypothesis, you need to combine the three Topic Sentences into a single sentence answer.

By combining your three answers to the sub-questions , you are ultimately providing a complete answer to the original Key Inquiry Question .

For example:

What's next?

Need a digital Research Journal?

Additional resources

What do you need help with, download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

The ceiling of the Altamira caves in Cantabria, Spain. Photo by Stephen Alvarez/Alvarez Photography

Why make art in the dark?

New research transports us back to the shadowy firelight of ancient caves, imagining the minds and feelings of the artists.

by Izzy Wisher + BIO

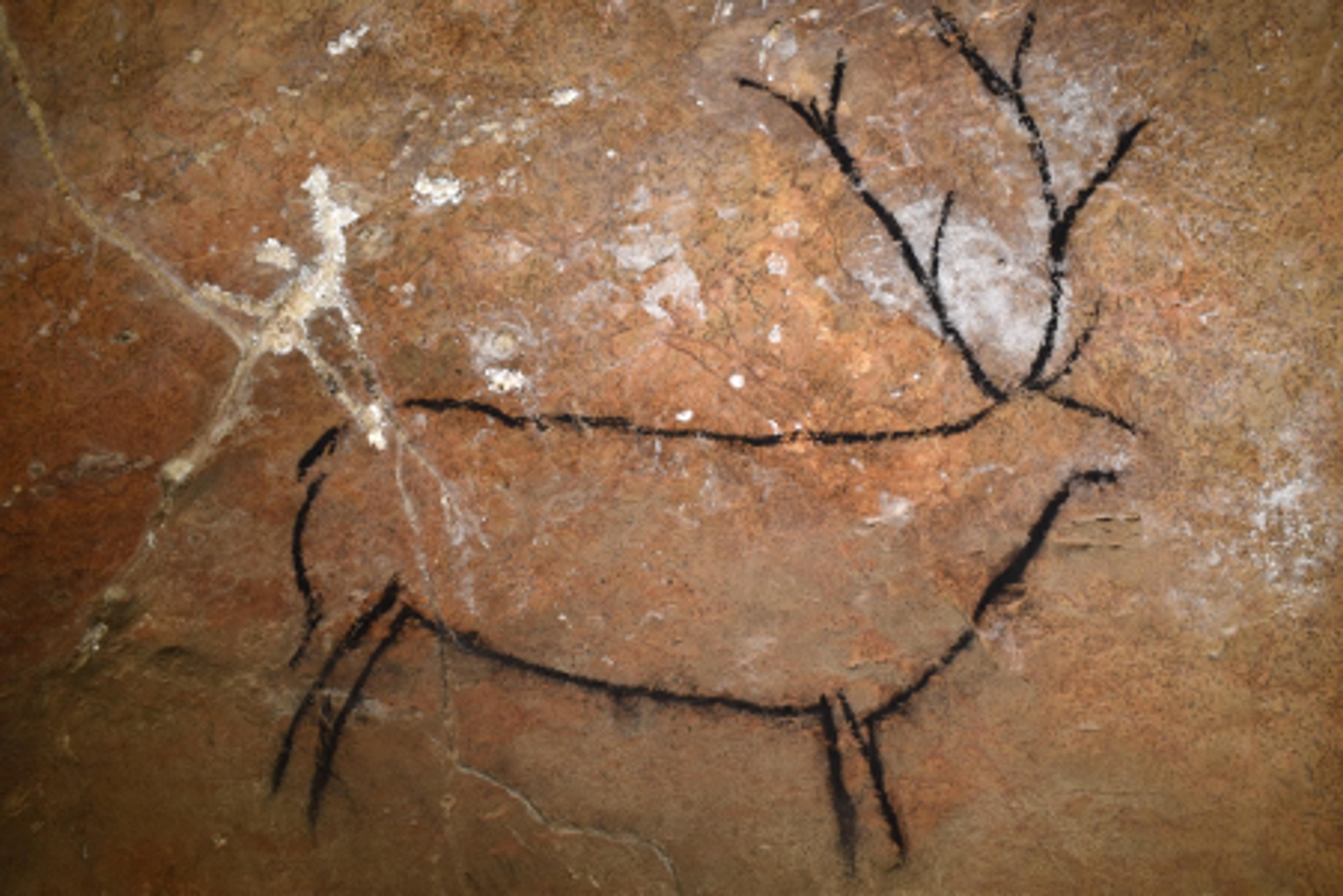

Charcoal drawings of stags, elegantly rendered in fluid lines, emerge under my torchlight as we squeeze through a tiny hidden entrance to a small chamber deep within Las Chimeneas cave in northern Spain. The chamber has space for just a couple of people, and certainly not standing, so we crouch on the cave floor and stare in awe at the depictions. Despite their remarkable freshness, they were drawn nearly 18,000 years ago. We sit in silence for a moment, soaking in the deep history of the space and realising that our ancient ancestors must have sat in the same cramped position as us. ‘Why do you think they drew these stags here?’ Eduardo Palacio-Pérez, the conservator of the cave, asks me. ‘I really don’t think we’ll ever know for sure,’ I reply.

What we do know is that during the Upper Palaeolithic ( c 45,000-15,000 years ago), our distant ancestors ventured deep underground to make these images. In these unfamiliar environments, they produced a rich display – from unusual abstract forms to highly detailed renderings of animals – under the dim glow of firelight cast by their lamps. Naturalistic animal outlines, rows of finger-dotted marks and splatter marks preserving the shadows of ancient hands remain frozen in time within the caves, representing tens of thousands of years of people returning to the darkness to engage in art-making.

This curious, yet deeply creative, behaviour captures the imagination. Yet as Jean Clottes – a prominent Palaeolithic art researcher – succinctly put it, the key unanswered question for us all is: ‘Why did they draw in those caves?’

C ertainly, since the earliest discovery of cave art in 1868 at Altamira in Spain, thousands of academic researchers have used an arsenal of different approaches – from high-resolution 3D scanning to analogies with contemporary hunter-gatherer societies – to try to unlock the intentions of Ice Age artists. There has been no shortage of hypotheses, some more plausible than others. Since the fragmentary archaeological record cannot provide answers alone, these theories draw on ethnographic and psychological research, and suggestions have varied from the mythical and magical, the symbolic and linguistic, to the mundane.

One suggestion is that Ice Age artists were high-status shamans who performed mysterious rites in the dark. These spiritual individuals are thought to have induced trance-like states deep in the caves, either through rhythmic drumming or mind-altering drugs. Altered states of consciousness may have facilitated communicating with ancestors, experiencing otherworldly psychedelic imagery, or coaxing animals out from a spirit world beyond the rocky surfaces of deep cave environments. The shaman hypothesis draws on ethnographic accounts and has come under significant criticism both for inappropriately drawing parallels between peoples today and those who lived in the deep past, and for subsuming a huge breadth of cultural behaviours under one label: ‘shamanism’.

Flickering firelight, echoing acoustics and tactile interactions form visceral experiences for each artist

A different hypothesis is that abstract marks and ‘signs’ on cave walls were a proto-writing system or part of a widespread means of communication. These communication systems are posited to have had a plethora of different contexts of use, from marking the changing seasons to denoting group identities. On this view, caves were rich resources for understanding the surrounding environment, for recording which animals were where, when they would reproduce, and for developing awareness of the presence of other local populations of people in the area. As supporting evidence, some researchers have singled out the ethologically accurate details: the colouring of the horses depicted reflects the genetic diversity of Ice Age horses; the shaggy winter coats of animals are shown accurately; and even specific animal behaviour can be identified. Yet, somewhat paradoxically, these interpretations assume a kind of stasis to the cave art. Temporal dimensions of the art are collapsed into one system that is assumed to have persisted across thousands of years of changing climates and shifting population dynamics.

These kinds of evocative interpretations of cave art , situating it within rich cultural milieus, contrast with the view that Palaeolithic art was merely ‘art for art’s sake’. Here, the enigmatic images on cave walls are assumed to have been produced by bored hunters who spent time honing their artistic abilities to create aesthetically pleasing depictions. Abstract signs are explained neurologically as pleasing patterns: intersecting lines, for example, resonate within the visual system to stimulate aesthetic pleasure. This view casts Ice Age art-making as a practice that emerged from our ancestors’ neurology – the tendency for some shapes and patterns to be ‘pleasing’ – and held no deeper meaning to the societies that created the depictions.

More nuanced approaches to Ice Age art that, unlike the above hypotheses discussed so far, do not seek one explanation for the artist’s motivations have revealed the multisensory experiences that would have been the context in which Ice Age art was created. Flickering firelight, echoing acoustics, multigenerational engagements with artistic behaviours and tactile interactions with the rough limestone walls and smooth stalagmites coalesce to form unique, visceral experiences for each artist at a specific time in a specific place. While the actual motivations of our ancestors are locked in time, these more nuanced perspectives situate us in the deeply human experiences of the past. We can begin to understand why our ancestors may have been attracted to particular cave spaces and to the sorts of sensory experiences stimulated in these environments, particularly visual experiences.

C lose your eyes. Take a deep breath. You’re standing in a cave, tens of thousands of years ago. The damp, earthen smell mixes with the warm smoke from your firelit torch and saturates your nostrils. The muted silence is broken only by the subtle crackles of the fire and distant drips of water that echo around the space. You’re alone, but feel the presence of those who have stood in this place before you.

Open your eyes. The darkness is encompassing, and the warm glow of firelight desperately tries to illuminate the vast space around you. It is almost impossible to distinguish anything. As you gingerly move forward, feeling your way through the dark, the flickering light cast from your torch partially illuminates a peculiar formation on the cave wall.

Our vision can rarely be trusted. Far from faithfully reproducing an accurate image of the world around us, our visual system selectively focuses on important information in our environment. As you read the words in this article, your eyes are rapidly flicking between different letters, as your visual system is making educated guesses about what each of the words says. This means that lteters can appaer out of oredr, but you can still read them with relative ease. Your surroundings are not the focus of your attention right now, and your visual system is making a fundamental assumption that these surroundings will remain mostly static. In your peripheral vision, a significant amount of visual information can change without your knowledge; colours can shift, and objects themselves can completely change their form. Only movement appears to be readily detected by peripheral vision, presumably so as not to render us completely inert when danger approaches and our attention is focused elsewhere. Visual illusions play on exactly these processes, demonstrating how unfaithful our vision truly is in relaying an unbiased representation of our surroundings.

All of us have perceived twisting tree trunks in dim light as unusual creatures emerging from the darkness

The reason behind this selectivity in our visual attention is not some flaw in human evolution, but the opposite. By focusing attention and making educated guesses about missing information, we can rapidly process visual information and sharpen our gaze on only the most salient pieces of information in our visual sphere. This is intrinsically informed by our lived experience of the world. As elegantly framed by the neuropsychologist Chris Frith in his book Making Up the Mind (2007), what we perceive is ‘not the crude and ambiguous cues that impinge from the outside world onto [our] eyes and [our] ears and [our] fingers. [We] perceive something much richer – a picture that combines all these crude signals with a wealth of past experience.’

Our visual system is thus trained to become expert in certain kinds of visual information that are understood to be important to us. This visual expertise is defined as the ability to holistically process certain kinds of information, so that we identify the individual as rapidly as the group classification; for example, we can identify the identity of an individual person (‘Joolz’) as quickly as we identify that it is ‘a person’ standing in front of us. While it is often culturally determined what kinds of visual information we develop expertise in, we can also consciously develop this ability. Expert birdwatchers, for example, rapidly identify the specific species of bird as quickly as they identify that it is, indeed, a bird that they are looking at. This kind of expertise shapes how the visual system both focuses its attention and fills in the blanks when information is missing.

Pareidolia – a visual phenomenon of seeing meaningful forms in random patterns – seems to be a product of this way in which our visual system selectively focuses on certain visual information and makes assumptions when ‘completing’ the image. Pareidolia is a universal experience; all of us have looked at clouds and recognised faces and animals, or perceived gnarled, twisting tree trunks in dim light as unusual creatures emerging from the darkness. While we might think of these visual images as a mistake – we know there isn’t a large face looming down at us from the clouds – it seems to have emerged as an evolutionary advantage. By assuming that a fragmentary outline is, in fact, a predator hiding in foliage, we can react quickly and avoid a grisly death, even if said predator turns out to be an illusion caused by merely branches and leaves.

This evolutionary advantage is stimulated even further in compromised visual conditions, such as low light. Our visual system kicks into overdrive and uses what we know about the world, formed by our daily lived experience, to fill in missing information. For those of us living in highly populated, socially orientated societies, this means our experience of pareidolia often manifests as faces. We have been culturally trained to focus our visual attention primarily on facial intricacies, rapidly processing the similarities and differences in appearances, or even subtle cues that may indicate an emotional state. This lived experience of an oversaturation of facial information shapes our response to ambiguous visual information: we see faces everywhere.

If we imagine, however, that we lived in small groups within a sparsely populated landscape where our survival depended on the ability to identify, track and hunt animals, we might reasonably expect that our visual system would become attuned to certain animal forms instead. We would be visually trained to identify the partial outlines of animals hiding behind foliage or the distant, vague outlines of creatures far away in the landscape. We would even have an intimate knowledge of their behaviours, how they move through the landscape, the subtle cues of twitching ears or raised heads that indicate they might be alerted to our presence. Our Ice Age ancestors may have therefore experienced animal pareidolia to the same degree that we experience face pareidolia. Where we anthropomorphise and perceive faces, they would have zoomorphised and perceived animals.

‘I s that…?’ You begin to doubt your own eyes. A shadow flickers, drawing your attention to the movement. Cracks, fissures and undulating shapes of the cave wall start to blur in the darkness to form something familiar to your eyes. Under the firelight, it is difficult to distinguish it immediately. As it flickers in and out of view, you start to see horns formed by cracks, the subtle curvature of the wall as muscular features. A bison takes shape and emerges from the darkness.

How do these visual, sensory experiences relate to Ice Age cave art-making? This was the question that burned in my mind during my research. For some time, it has been known that the artists who created animal imagery in caves often utilised natural features, integrating cracks to represent the backs of animals or the varied topography to add a sense of three-dimensionality to their images. The first known cave-art discovery – the bison at Altamira – represents the use of undulating convexities and concavities to give dimension and form to the depictions of bison, which silently lay with their legs curled underneath their bodies on the low cave ceiling. So-called ‘masks’ from this cave and others in the region are further examples of using the natural forms of caves to produce depictions; these often take a formation that appears to be a zoomorphic head and add subtle details of the eyes and nostrils to complete the form. Similarly, subtle animal depictions emerge from natural shapes embedded in cave walls that are enhanced with a few details added by ochre-covered fingers. Thus, far from perceiving the cave wall as a blank canvas, it seems these innovative artists actively used cave features to shape and enrich their depictions.

These striking examples clearly indicate the role of pareidolia in the production of at least some cave-art depictions. The most robust theoretical discussions of the potential role of pareidolia in Ice Age art have been presented by Derek Hodgson. He suggests that the dark conditions of caves would have heightened visual responses, triggering pareidolia or more visceral visual responses such as hyper-images (think of that split second when you perceive a person standing in your room at night, before you realise it’s just your coat hanging on the back of the door). Although compelling, the inherent challenge with these interpretations is that they do not provide empirical evidence – beyond informal observations of the archaeological record – to scientifically test whether pareidolia was indeed informing the making of Ice Age art.

Some even saw the same animal in the same cracks and undulations of the cave wall as depicted by Ice Age people

I wanted to see if there was a way to empirically test whether cave environments do trigger certain visual psychological phenomena. How can we create immersive cave environments that stimulate ecologically valid responses, yet allow us to experimentally control conditions? Since bringing flaming torches into precious Ice Age cave-art sites was absolutely out of the question, virtual reality (VR) seemed to be the natural answer. By recreating the conditions in which Ice Age artists would have viewed cave walls, we could do something that has not been possible previously: see whether people today are visually drawn to the same areas of the cave walls used by ancient artists.

In a recent study published in Nature: Scientific Reports , we did exactly this. We built VR cave environments that integrated 3D models of the real cave walls from sites in northern Spain, and modified the 3D models to remove any traces of the Palaeolithic art. We modified the lighting conditions to replicate the darkness of caves, and gave participants a virtual torch that had the same properties as lighting technologies available to Ice Age artists, to illuminate their surroundings. We asked participants to view the cave walls, and gradually gave more focused questions about whether they would draw anything on the wall, where their drawings would be, and why. Using eye-tracking technology, we were also able to see where the participants were unconsciously focusing their visual attention during the experiment. We hypothesised that both the participants’ experiential responses and their unconscious eye movements would correspond to the same areas of the cave wall that Palaeolithic artists used.

‘What do you see?’ a distant voice echoes out. ‘This crack and the undulating shape of the wall… it looks like a bison, the shape of the cave wall almost completes the head and back of it,’ you reply, and stretch out your hand in the virtual space to trace the shape. Later you find out that this corresponded to the same area a Palaeolithic artist also depicted a bison, using the same natural features that drew your own visual attention.

Our results supported our hypothesis: it seems pareidolia may have played a role in the making of some of the cave-art images. Participants not only experienced pareidolia in response to the cave walls they viewed, but also had this experience in response to the same features that Ice Age artists utilised for their drawings. Some participants had potent responses, where they literally perceived certain animals as already existing on the cave wall in front of them. Others even saw the same animal in the same cracks and undulations of the cave wall as was depicted by Ice Age people – ie, they perceived a bison in the same place as a bison was drawn. Not all of the art had such a convincing relationship with pareidolia, however. In some cases, it seems that pareidolia may not have motivated the making of the art. This is supported by another study we conducted, where we suggest the degree to which pareidolia-informed cave art varied: it was part of a ‘conversation’ that occurred between the artist and the cave wall.

The deep meaning of seeing these animal forms in cave walls and ‘releasing’ them would have undoubtedly varied cross-culturally and temporally. In one instance, it may have been part of powerful rites in the dark, where elusive figures integrated this act within other cultural or cosmological rituals, witnessed by ancestral spirits and the community alike. In another, it may have been a more intimate, discreet engagement between just one individual and the cave wall; the soft whispers of fingers brushing pigment on stone to depict an animal of deep importance to them. The perspective of time may prevent us from ever distinguishing between the two, but the foundations of these actions may have been the phenomenon of pareidolia.

This has significant implications for understanding art-making – its emergence and experience – and not just within the Ice Age. The ability to draw something that exists in four dimensions (with time, expressed as the movement of an animal, representing the fourth dimension) is non-trivial; it requires the complex processing and abstraction of visual information. Pareidolia may have been the mechanism through which figurative representation emerged, scaffolding the ability to draw things two-dimensionally. By seeing hidden forms in cave walls, we learnt how forms can be represented. It may have started as adding subtle details to elucidate the form; a small smear of ochre here or there, and suddenly the animal emerges. As time passed, the potential of using pigment to produce animal representations developed, and gradually more detailed forms were produced on a greater variety of material substrates. It became engrained more and more within every culture and society on Earth, until one day a cave artist drew an animal on a smooth rock surface.

Ageing and death

Peregrinations of grief

A friend and a falcon went missing. In pain, I turned to ‘Slaughterhouse-Five’ – and found a new vision of sorrow and time

Nations and empires

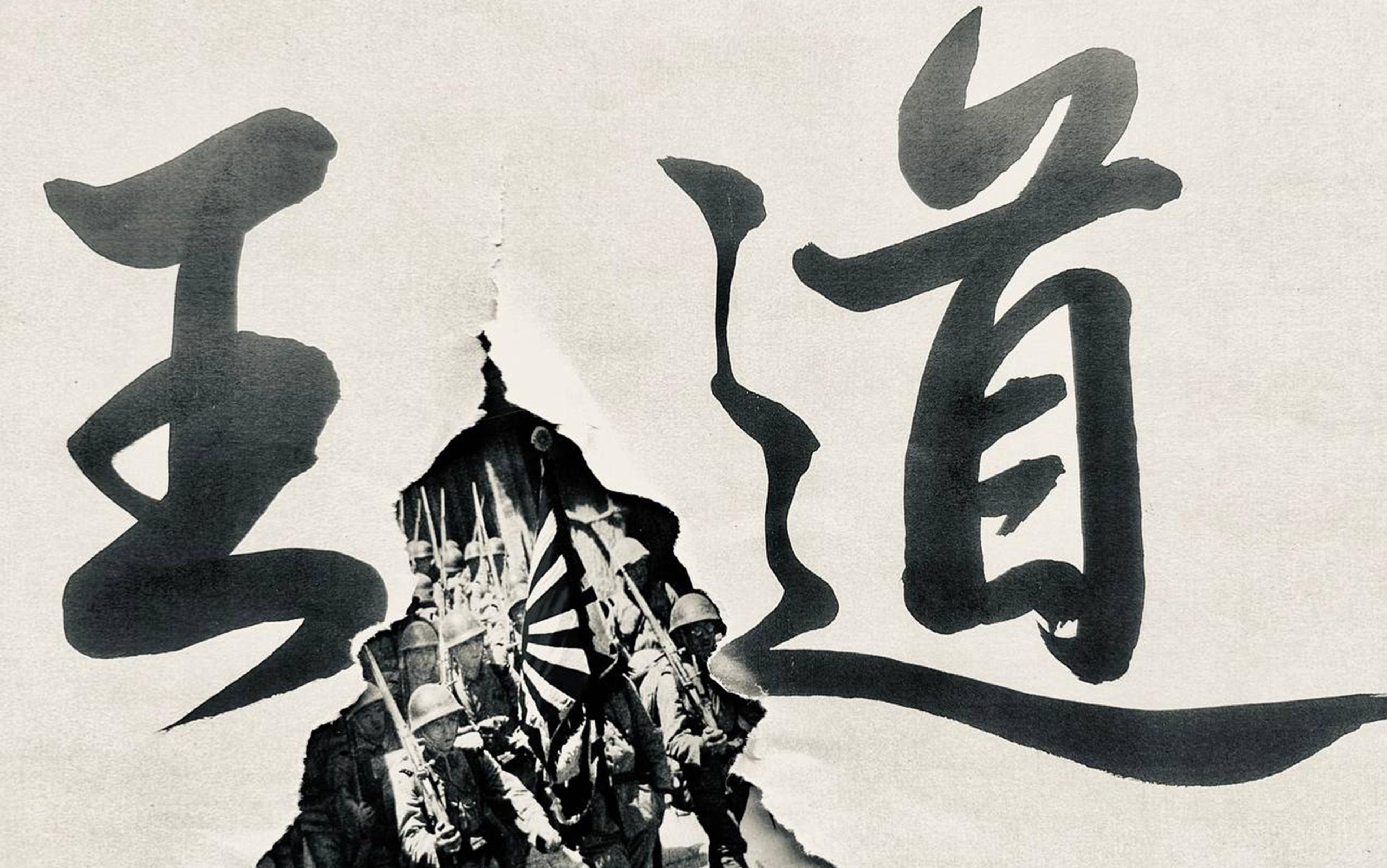

Chastising little brother

Why did Japanese Confucians enthusiastically support Imperial Japan’s murderous conquest of China, the homeland of Confucius?

Shaun O’Dwyer

Stories and literature

Her blazing world

Margaret Cavendish’s boldness and bravery set 17th-century society alight, but is she a feminist poster-girl for our times?

Francesca Peacock

Ecology and environmental sciences

To take care of the Earth, humans must recognise that we are both a part of the animal kingdom and its dominant power

Hugh Desmond

Mental health

The last great stigma

Workers with mental illness experience discrimination that would be unthinkable for other health issues. Can this change?

Pernille Yilmam

Folk music was never green

Don’t be swayed by the sound of environmental protest: these songs were first sung in the voice of the cutter, not the tree

Richard Smyth

More From Forbes

Science and history connect in art analysis.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

From studying a newly discovered art piece to preventing mold and fungus in old paintings, chemistry and art history often meet and even inspired a new high school curriculum.

By analysing paint with X-ray fluorescence, chemists can learn more about art history

A few weeks ago, scientists in France published a research paper that describes how they analysed a painting that likely originated from the workshop of Botticelli. That means that even though it probably wasn’t painted by Botticelli himself, it was created in his studio by one or more of his assistants.

According to the research paper, this painting was discovered in 2011, in a church in Champigny-en-Beauce, France. To learn more about this new discovery, the researchers turned to science. They used many different techniques, including macro-x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (MA-XRF) to scan the whole painting and learn more about the chemical composition of the paint. They also used a different type of XRF analysis to get even more detail. The benefit of using X-ray fluorescence is that it’s very non-invasive: It’s not necessary to damage the painting to analyze the paint.

The measurements confirmed that the artwork was made with paints that were used in the 15th or 16th centuries in Italy. The way that the paints were layered also matched the styles used in Botticelli’s workshop, which further supported the theory that this painting was made there.

Methods like MA-XRF are increasingly popular with museums and art researchers to study art history through the chemistry of the materials that were used. But science and art meet in other ways as well.

NSA Warns iPhone And Android Users To Turn It Off And On Again

Donald trump 300 million poorer after guilty verdict as truth social stock sinks, trump still faces 54 more felony charges after hush money verdict.

Earlier this year, a study from Spain reviewed different methods that could prevent mold or fungus damage on easel paintings. By easel paintings they mean paintings done on canvases (or sometimes other surfaces) rather than murals, for example. That’s an important distinction to make when talking about this type of damage, because obviously a wall painting would have very different risks of mold than a framed canvas. But even canvases aren’t safe from damage, and that’s why researchers have been trying to find the best ways to remove fungus or molds and to prevent further damage.

This new review by researchers from the University of Valencia summarized several of these fungal removal methods, and found that some of the more eco-friendly solutions such as essential oils or light radiation were probably about as good as biocidal chemicals in protecting art from damage.

Studies like these are just some of the many situations where chemistry overlaps with art. Inspired by this overlap, chemists at Virginia Commonwealth University developed a curriculum for US high schools that combines chemistry and world history lessons. For example, one of the lessons describes how historic frescoes were created. In a recent study , the researchers describe how they developed this method and how it was received by the test students. Before and after completing the combined chemistry and history curriculum, students completed a test with exam questions in both subjects. After the curriculum, they performed 4% better in chemistry and 13.4% better in world history. The students and teachers also enjoyed these lessons that showed both a real-world application of chemistry and a creative and practical side to history.

Considering that there is so much overlap between chemistry and (art) history, it would be interesting to see a curriculum like this on a broader scale.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Join The Conversation

One Community. Many Voices. Create a free account to share your thoughts.

Forbes Community Guidelines

Our community is about connecting people through open and thoughtful conversations. We want our readers to share their views and exchange ideas and facts in a safe space.

In order to do so, please follow the posting rules in our site's Terms of Service. We've summarized some of those key rules below. Simply put, keep it civil.

Your post will be rejected if we notice that it seems to contain:

- False or intentionally out-of-context or misleading information

- Insults, profanity, incoherent, obscene or inflammatory language or threats of any kind

- Attacks on the identity of other commenters or the article's author

- Content that otherwise violates our site's terms.

User accounts will be blocked if we notice or believe that users are engaged in:

- Continuous attempts to re-post comments that have been previously moderated/rejected

- Racist, sexist, homophobic or other discriminatory comments

- Attempts or tactics that put the site security at risk

- Actions that otherwise violate our site's terms.

So, how can you be a power user?

- Stay on topic and share your insights

- Feel free to be clear and thoughtful to get your point across

- ‘Like’ or ‘Dislike’ to show your point of view.

- Protect your community.

- Use the report tool to alert us when someone breaks the rules.

Thanks for reading our community guidelines. Please read the full list of posting rules found in our site's Terms of Service.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This wooden leg was carved by an artist from the Marquesas [mar-KAY-zas] Islands, a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, located in the Pacific Ocean. The Marquesas are the farthest group of islands from any continent. In terms of the arts, they are well-known for their tattoo art, as well as for their carvings in wood, bone, and shell.

An expert who studies and creates maps of Earth's natural and human-made features. An object made or used by people in the past. Before written history. Relating to a ceremony, such as a religious ceremony. Concerns the distant past, from the earliest humans through the first great civilizations.

on evidence - what you see or know about already. What do you think this work of art is about? If you are looking at a painting, what do you think it is a painting of? Write your hypothesis below, and next to it write what you see in the work of art that makes you think this guess might be true. You may have more than one. HYPOTHESIS EVIDENCE

The magic hunt. Abbé Breuil (1877-1961) and Henri Begouën (1863-1956) repeated the hypothesis of "prescience magic," suggesting that prehistoric humans attempted to influence the result of their hunt by drawing it in caves. Abbot Breuil in the cave of Lascaux faces the panel of the Unicorn. (1940/1940) Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site.

this painting. 2. Write a hypothesis stating why you think the artist created this painting. 3. Read Section 4. Label any additional important items in the image. 4. Why do social scientists think this paint-ing was created? 1. Label two details in the image that may offer clues about why the artist created this painting. 2. Write a hypothesis ...

Courbet called himself a "painter of the real," vowing only to paint what he could see. He believed that art had the power to teach people lessons, or even criticize society. This painting is of Ornans, the town where Courbet grew up. On the surface the scene is serene. But it also has a revolutionary hidden meaning.

A hypothesis is a single sentence answer to the Key Inquiry Question that clearly states what your entire essay is going to argue. It contains both the argument and the main reasons in support of your argument. Each hypothesis should clearly state the 'answer' to the question, followed by a 'why'. For Example:

One of the most basic types of contextual analysis is the interpretation of subject matter. Much art is representational (i.e., it creates a likeness of something), and naturally we want to understand what is shown and why. Art historians call the subject matter of images iconography. Iconographic analysis is the interpretation of its meaning.

Transcript. Giovanni Bellini's "Madonna of the Meadow" is a Renaissance painting analyzed using visual tools like scale, composition, pictorial space, form, line, color, light, tone, texture, and pattern. The painting's moderate size, pyramid-like composition, and use of perspective create a sense of depth and intimacy.

Carefully examine each photograph from the cave. Match it to one of these images. Complete that section of the Reading Notes. Transparency 1: Cave Painting of a Human. Find evidence: Label three details in the image that may offer clues about why the artist created this painting. Our hypothesis: We think the artist created this because...

Learn for free about math, art, computer programming, economics, physics, chemistry, biology, medicine, finance, history, and more. Khan Academy is a nonprofit with the mission of providing a free, world-class education for anyone, anywhere.

How to Write a Good Hypothesis. Writing a good hypothesis is definitely a good skill to have in scientific research. But it is also one that you can definitely learn with some practice if you don't already have it. Just keep in mind that the hypothesis is what sets the stage for the entire investigation. It guides the methods and analysis.

Naturalistic animal outlines, rows of finger-dotted marks and splatter marks preserving the shadows of ancient hands remain frozen in time within the caves, representing tens of thousands of years of people returning to the darkness to engage in art-making. This curious, yet deeply creative, behaviour captures the imagination.

Leonardo da Vinci began painting the Mona Lisa in 1503, and it was in his studio when he died in 1519. He likely worked on it intermittently over several years, adding multiple layers of thin oil glazes at different times. Small cracks in the paint, called craquelure, appear throughout the whole piece, but they are finer on the hands, where the thinner glazes correspond to Leonardo's late ...

Ask them why they think that Jack Lembeck created this painting. As you get feedback, continue to question them about the creative ... students are writing about the same work of art, you may put students into ... Write your main idea in a topic sentence or thesis statement. 6. Write an outline of supporting material to back up your topic ...

Hypothesis: The artist Leonardo da Vinci created the Mona Lisa painting to explore the nature of beauty and the human condition.. What is the hypothesis . Evidence: The Mona Lisa is a portrait of a woman with a mysterious smile.Da Vinci used a variety of techniques to create a realistic and lifelike image of the sitter. He also used a technique called sfumato, which creates a soft, hazy effect.

Label three details in the image that may offer clues about why the artist created this painting. 2. Write a hypothesis stating why you think the artist created this painting. 3. Read Section 6. Label any additional important items in the image. 4. Why do social scientists think this paint- ing was created?

Developing a hypothesis (with example) Step 1. Ask a question. Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project. Example: Research question.

2. Write a hypothesis stating why you think the artist created this painting. 3. Read Section 3. Label any additional important items in the image. 4. Why do social scientists think this painting was created? 1. Before reading, label two details in the image that may offer clues about why the artist created this painting. 2. Write a hypothesis ...

From studying a newly discovered art piece to preventing mold and fungus in old paintings, chemistry and art history often meet and even inspired a new high school curriculum. By analysing paint ...

For artists working in the West in the period before the modern era (before about 1800 or so), the process of selling art was different than it is now. In the Middle Ages and in the Renaissance works of art were commissioned, that is, they were ordered by a patron (the person paying for the work of art), and then made to order. A patron usually entered into a contract with an artist that ...

this painting. 2. Write a hypothesis stating why you think the artist created this painting. 3. Read Section 4. Label any additional important items in the image. 4. Why do social scientists think this paint-ing was created? 1. Label two details in the image that may offer clues about why the artist created this painting. 2. Write a hypothesis ...

Artificial intelligence (AI) is beginning to be applied in the field of art, which had hitherto been an area exclusively reserved for human creativity. Using online AI tools, lay people can easily create artworks that imitate the style of famous artists. Consequently, human judgment on the authenticity of artworks has become critical.

You are existing in a more aware, alert, present space. SPEAKER 3: Sometimes people think that the only way of looking at art is going to museums and places like that. But maybe sometimes art is everywhere, in the street, if you look at architectural places, or everything. So you really don't need to go to a museum to see art.