Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Information Literacy

11 A Beginner’s Guide to Information Literacy

By emily metcalf.

Introduction

Welcome to “A Beginner’s Guide to Information Literacy,” a step-by-step guide to understanding information literacy concepts and practices.

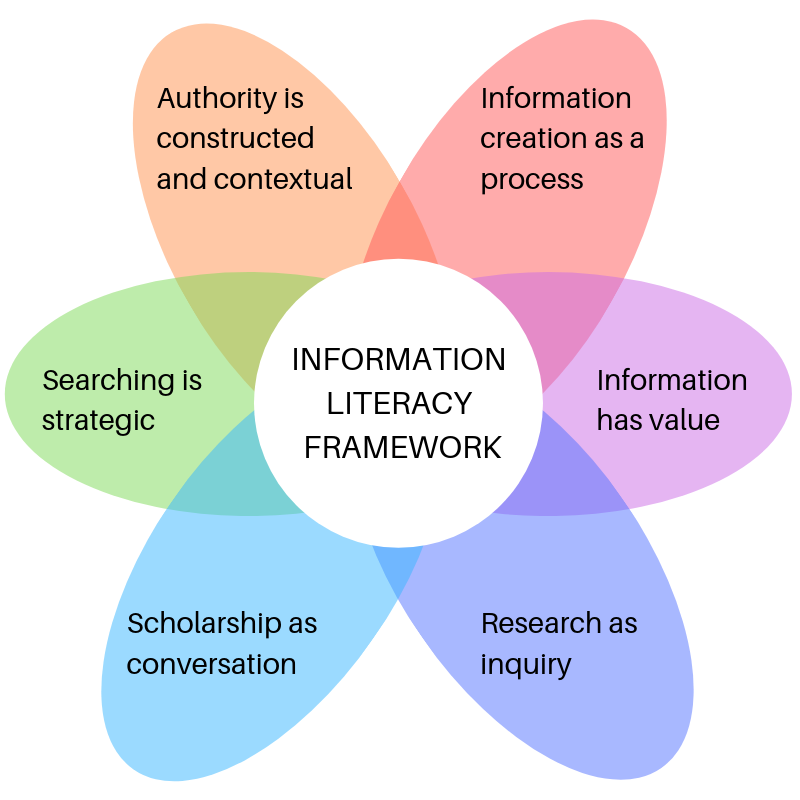

This guide will cover each frame of the “ Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education ,” a document created by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) to help educators and librarians think about, teach, and practice information literacy (see Figure 11.1). The goal of this guide is to break down the basic concepts in the Framework and put them in accessible, digestible language so that we can think critically about the information we’re exposed to in our daily lives.

To start, let’s look at the ACRL definition of “information literacy,” so we have some context going forward:

Information Literacy is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.

Boil that down and what you have are the essentials of information literacy: asking questions, finding information, evaluating information, creating information, and doing all of that responsibly and ethically.

We’ll be looking at each of the frames alphabetically, since that’s how they are presented in the framework. None of these frames is more important than another, and all need to be used in conjunction with the others, but we have to start somewhere, so alphabetical it is!

In order, the frames are

- Authority is constructed and contextual

- Information creation as a process

- Information has value

- Research as inquiry

- Scholarship as conversation

- Searching as strategic exploration

Just because we’re laying this out alphabetically does not mean you have to go through it in order. Some of the sections reference frames previously mentioned, but for the most part you can jump to wherever you like and use this guide however you see fit. You can also open up the framework using the link above or in the attached resources to read the framework in its original form and follow along with each section.

The following sections originally appeared as blog posts for the Texas A&M Corpus Christi’s library blog. Edits have been made to remove institutional context, but you can see the original posts in the Mary and Jeff Bell Library blog archives .

Authority is Constructed and Contextual

The first frame is “ Authority is Constructed and Contextual .” There’s a lot to unpack in that language, so let’s get started.

Start with the word “authority.”

At the root of “authority” is the word “author.” So start there: who wrote the piece of information you’re reading? Why are they writing? What stake do they have in the information they’re presenting? What are their credentials (You can straight up google their name to learn more about them)? Who are they affiliated with? A public organization? A university? A company trying to make a profit? Check it out.

Now let’s talk about how authority is “constructed.”

Have you ever heard the phrase “social construct”? Some people say gender is a social construct or language, written and spoken, is a construct. “Constructed” basically means humans made it up at some point to instill order in their communities. It’s not an observable, scientifically inevitable fact. When we say “authority” is constructed, we’re basically saying that we as individuals and as a society choose who we give authority to, and sometimes we might not be choosing based on facts.

A common way of assessing authority is by looking at an author’s education. We’re inclined to trust someone with a PhD over someone with a high school diploma because we think the person with a PhD is smarter. That’s a construct. We’re conditioned to think that someone with more education is smarter than people with less education, but we don’t know it for a fact.

There are a lot of reasons someone might not seek out higher education. They might have to work full time or take care of a family or maybe they just never wanted to go to college. None of these factors impact someone’s intelligence or ability to think critically.

If aliens land on South Padre Island, TX, there will be many voices contributing to the information collected about the event. Someone with a PhD in astrophysics might write an article about the mechanical workings of the aliens’ spaceship. Cool; they are an authority on that kind of stuff, so I trust them.

But the teenager who was on the island and watched the aliens land has first-hand experience of the event, so I trust them too. They have authority on the event even though they don’t have a PhD in astrophysics.

So, we cannot think someone with more education is inherently more trustworthy or smarter or has more authority than anyone else. Some people who are authorities on a subject are highly educated, some are not.

Likewise, let’s say I film the aliens landing and stream it live on Facebook. At the same time, a police officer gives an interview on the news that says something contradicting my video evidence. All of a sudden, I have more authority than the police officer. Many of us are raised to trust certain people automatically based on their jobs, but that’s also a construct. The great thing about critical thinking is that we can identify what is fact and fiction, and we can decide for ourselves who to trust.

The final word is “contextual.”

This one is a little simpler. If I go to the hospital and a medical doctor takes out my appendix, I’ll probably be pretty happy with the outcome. If I go to the hospital and Dr. Jill Biden, a professor of English, takes out my appendix, I’m probably going to be less happy with the results.

Medical doctors have authority in the context of medicine. Dr. Jill Biden has authority in the context of education. And Doctor Who has authority in the context of inter-galactic heroics and nice scarves.

This applies when we talk about experiential authority, too. If an eighth-grade teacher tells me what it’s like to be a fourth-grade teacher, I will not trust their authority. I will, however, trust a fourth-grade teacher to tell me about teaching fourth grade.

The Takeaway

Basically, when we think about authority, we need to ask ourselves, “Do I trust them? Why?” If they do not have experience with the subject (like witnessing an event or holding a job in the field) or subject expertise (like education or research), then maybe they aren’t an authority after all.

P.S. I’m sorry for the uncalled-for dig, Dr. Biden. I’m sure you’d do your best with an appendectomy.

Ask Yourself

- In what context are you an authority?

- If you needed to figure out how to do a kickflip on a skateboard, who would you ask? Who’s an authority in that situation?

Information Creation as a Process

The second frame is “ Information Creation as a Process .”

Information Creation

So first of all, let’s get this out of the way: everyone is a creator of information. When you write an essay, you’re creating information. When you log the temperature of the lizard tank, you’re creating information. Every Word Doc, Google Doc, survey, spreadsheet, Tweet, and PowerPoint that you’ve ever had a hand in? All information products. That YOU created. In some way or another, you created that information and put it out into the world.

One process you’re probably familiar with if you’re a student is the typical research paper. You know your professor wants about five to eight pages consisting of an introduction that ends in a thesis statement, a few paragraphs that each touch on a piece of evidence that supports your thesis, and then you end in a conclusion paragraph which starts with a rephrasing of your thesis statement. You save it to your hard drive or Google Drive and then you submit it to your professor.

This is one process for creating information. It’s a boring one, but it’s a process.

Outside of the classroom, the information-creation process looks different, and we have lots of choices to make.

One of the choices you’ll need to make is the mode or format in which you present information. The information I’m creating right now comes to you in the mode of an Open Educational Resource . Originally, I created these sections as blog posts. Those five-page essays I mentioned earlier are in the mode of essays.

When you create information (outside of a course assignment), it’s up to you how to package that information. It might feel like a simple or obvious choice, but some information is better suited to some forms of communication. And some forms of communication are received in a certain way, regardless of the information in them.

For example, if I tweet “Jon Snow knows nothing,” it won’t carry with it the authority of my peer-reviewed scholarly article that meticulously outlines every instance in which Jon Snow displays a lack of knowledge. Both pieces of information are accurate, but the processes I went through to create and disseminate the information have an effect on how the information is received by my audience.

And that is perhaps the biggest thing to consider when creating information: your audience.

The Audience Matters

If I just want my twitter followers to know Jon Snow knows nothing, then a tweet is the right way to reach them. If I want my tenured colleagues and other various scholars to know Jon Snow knows nothing, then I’m going to create a piece of information that will reach them, like a peer-reviewed journal article.

Often, we aren’t the ones creating information; we’re the audience members ourselves. When we’re scrolling on Twitter, reading a book, falling asleep during a PowerPoint presentation—we’re the audience observing the information being shared. When this is the case, we have to think carefully about the ways information was created.

Advertisements are a good example. Some are designed to reach a 20-year old woman in Corpus Christi through Facebook, while others are designed to reach a 60-year old man in Hoboken, NJ over the radio. They might both be selling the same car, and they’re going to put the same information (size, terrain, miles per gallon, etc.) in those ads, but their audiences are different, so their information-creation process is different, and we end up with two different ads for different audiences.

Be a Critical Audience Member

When we are the audience member, we might automatically trust something because it’s presented a certain way. I know that, personally, I’m more likely to trust something that is formatted as a scholarly article than I am something that is formatted as a blog. And I know that that’s biased thinking and it’s a mistake to make that assumption.

It’s risky to think like that for a couple of reasons:

- Looks can be deceiving. Just because someone is wearing a suit and tie doesn’t mean they’re not an axe murderer and just because something looks like a well-researched article, doesn’t mean it is one.

- Automatic trust unnecessarily limits the information we expose ourselves to. If I only ever allow myself to read peer-reviewed scholarly articles, think of all the encyclopedias and blogs and news articles I’m missing out on!

If I have a certain topic I’m really excited about, I’m going to try to expose myself to information regardless of the format and I’ll decide for myself (#criticalthinking) which pieces of information are authoritative and which pieces of information suit my needs.

Likewise, as I am conducting research and considering how best to share my new knowledge, I’m going to consider my options for distributing this newfound information and decide how best to reach my audience. Maybe it’s a tweet, maybe it’s a Buzzfeed quiz, or maybe it’s a presentation at a conference. But whatever mode I choose will also convey implications about me, my information creation process, and my audience.

You create information all of the time. The way you package and share it will have an effect on how others perceive it.

- Is there a form of information you’re likely to trust at first glance? Either a publication like a newspaper or a format like a scholarly article?

- Can you think of some voices that aren’t present in that source of information?

- Where might you look to find some other perspectives?

- If you read an article written by medical researchers that says chocolate is good for your health, would you trust the article?

- Would you still trust their authority if you found out that their research was funded by a company that sells chocolate bars? Funding and stakeholders have an impact on the creation process, and it’s worth thinking about how this can compromise someone’s authority.

Information Has Value

Onwards and upwards! We’re onto frame 3: “ Information Has Value .”

What Counts as Value?

There are a lot of different ways we value things. Some things, like money, are valuable to us because we can exchange them for goods and services. On the other hand, some things, like a skill, are valuable to us because we can exchange them for money (which we exchange for more goods and services). Some things are valuable to us for sentimental reasons, like a photograph or a letter. Some things, like our time, are valuable because they are finite.

The Value of Information

Information has all kinds of value.

One kind is monetary. If I write a book and it gets published, I’m probably going to make some money off of that (though not as much money as the publishing company will make). So that’s valuable to me.

But I’m also getting my name out into the world, and that’s valuable to me too. It means that when I apply for a job or apply for a grant, someone can google me and think, “Oh look! She wrote a book! That means she has follow-through and will probably work hard for us!” That kind of recognition is a sort of social value. That social value, by the way, can also become monetary value. If I’ve produced information, a university might give me a job, or an organization might fund my research. If I’ve invented a machine that will floss my teeth for me, the patent for my invention could be worth a lot of money (plus it’d be awesome. Cool factor can count as value.).

In a more altruistic slant, information is also valuable on a societal level. When we have more information about political candidates, for example, it influences how we vote, who we elect, and how our country is governed. That’s some really valuable information right there. That information has an effect on the whole world (plus outer space, if we elect someone who’s super into space exploration). If someone is trying to keep information hidden or secret, or if they’re spreading misinformation to confuse people, it’s probably a sign that the information they’re hiding is important, which is to say, valuable.

On a much smaller scale, think about the information on food packages. If you’re presented with calorie counts, you might make a different decision about the food you buy. If you’re presented with an item’s allergens, you might avoid that product and not end up in an Emergency Room with anaphylactic shock. You know what’s super valuable to me? NOT being in an Emergency Room!

But if you do end up in the Emergency Room, the information that doctors and nurses will use to treat your allergic reaction is extremely valuable. That value of that information is equal to the lives it’s saved.

Acting Like Information is Valuable

When we create our own information by writing papers and blog posts and giving presentations, it’s really important that we give credit to the information we’ve used to create our new information product for a couple of reasons.

First, someone worked really hard to create something, let’s say an article. And that article’s information is valuable enough to you to use in your own paper or presentation. By citing the author properly, you’re giving the author credit for their work, which is valuable to them. The more their article is cited, the more valuable it becomes because they’re more likely to get scholarly recognition and jobs and promotions.

Second, by showing where you’re getting your information, you’re boosting the value of your new information product. On the most basic level, you’ll get a higher grade on your paper, which is valuable to you. But you’re also telling your audience, whether it’s your professor or your boss or your YouTube subscribers, that you aren’t just making stuff up—you did the work of researching and citing, and that makes your audience trust you more. It makes the audience value your information more.

Remember early on when I said the frames all connect? “Information Has Value” ties into the other information literacy frames we’ve talked about, “Information Creation as a Process” and “Authority as Constructed and Contextual.” When I see you’ve cited your sources of information, then I, as the audience, think you’re more authoritative than someone who doesn’t cite their sources. I also can look at your information product and evaluate the effort you’ve put into it. If you wrote a tweet, which takes little time and effort, I’ll generally value it less than if you wrote a book, which took a lot of time and effort to create. I know that time is valuable, so seeing that you were willing to dedicate your time to create this information product makes me feel like it’s more valuable.

Information is valuable because of what goes into its creation (time and effort) and what comes from it (an informed society). If we didn’t value information, we wouldn’t be moving forward as a society, we’d probably have died out thousands of years ago as creatures who never figured out how to use tools or start a fire.

So continue to value information because it improves your life, your audiences’ lives, and the lives of other information creators. More importantly, if we stop valuing information a smarter species will eventually take over and it’ll be a whole Planet of the Apes thing and I just don’t have the energy for that right now.

- Can you think of some ways in which a YouTube video on dog training has value? Who values it? Who profits from it?

- Think of some information that would be valuable to someone applying to college. What does that person need to know?

Research as Inquiry

Easing on down the road, we’ve come to frame number 4: “ Research as Inquiry .”

“Inquiry” is another word for “curiosity” or “questioning.” I like to think of this frame as “Research as Curiosity,” because I think it more accurately captures the way our adorable human brains work.

Inquiring Minds Want to Know

When you think to yourself, “How old is Madonna?” and you google it to find out she’s 62 (as of the creation of this resource), that’s research! You had a question (“how old is Madonna?”), you applied a search strategy (googling “Madonna age”) and you found an answer (62). That’s it! That’s all research has to be!

But it’s not all research can be. This example, like most research, is comprised of the same components we use in more complex situations. Those components are a question and an answer, inquiry and research, “how old is Madonna?” and “62.” But when we’re curious, we go back to the inquiry step again and ask more questions and seek more answers. We’re never really done, even when we’ve answered the initial question and written the paper and given the presentation and received accolades and awards for all our hard work. If it’s something we’re really curious about, we’ll keep asking and answering and asking again.

If you’re really curious about Madonna, you don’t just think, “How old is Madonna?” You think “How old is Madonna? Wait, really ? Her skin looks amazing! What’s her skincare routine? Seriously, what year was she born? Oh my god, she wrote children’s books! Does my library have any?” Your questions lead you to answers which, when you’re really interested in a topic, lead you to more and more questions. Humans are naturally curious ; we have this sort of instinct to be like, “huh, I wonder why that is?” and it’s propelled us to learn things and try things and fail and try again! It’s all research as inquiry.

And to satisfy your curiosity, yes, the library I currently work at does own one of Madonna’s children’s books. It’s called The Adventures of Abdi , and you can find it in our Juvenile Collection on the second floor at PZ8 M26 Adv 2004. And you can find a description of her skincare routine in this article from W Magazine: https://www.wmagazine.com/story/madonna-skin-care-routine-tips-mdna . You’re welcome.

Identifying an Information Need

One of the tricky parts of research as inquiry is determining a situation’s information need. It sounds simple to ask yourself, “What information do I need?” and sometimes we do it unconsciously. But it’s not always easy. Here are a few examples of information needs:

- You need to know what your niece’s favorite Paw Patrol character is so you can buy her a birthday present. Your research is texting your sister. She says, “Everest.” And now you’re done. You buy the present, you’re a rock star at the birthday party. Your information need was a short answer based on a three-year old’s opinion.

- You’re trying to convince someone on Twitter that Nazis are bad. You compile a list of opinion pieces from credible news publications like the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times , gather first-hand narratives of Holocaust survivors and victims of hate crimes, find articles that debunk eugenics, etc. Your information need isn’t scholarly publications, it’s accessible news and testimonials. It’s articles a person might actually read in their free time, articles that aren’t too long and don’t require access to scholarly materials that are sometimes behind paywalls.

- You need to write a literature review for an assignment, but you don’t know what a literature review is. So first you google “literature review example.” You find out what it is, how one is created, and maybe skim a few examples. Next, you move to your library’s website and search tool and try “oceanography literature review,” and find some closer examples. Finally, you start conducting research for your own literature review. Your information need here is both broader and deeper. You need to learn what a literature review is, how one is compiled, and how one searches for relevant scholarly articles in the resources available to you.

Sometimes it helps to break down big information needs into smaller ones. Take the last example, for instance: you need to write a literature review. What are the smaller parts?

- Information Need 1: Find out what a literature review is

- Information Need 2: Find out how people go about writing literature reviews

- Information Need 3: Find relevant articles on your topic for your own literature review

It feels better to break it into smaller bits and accomplish those one at a time. And it highlights an important part of this frame that’s surprisingly difficult to learn: ask questions. You can’t write a literature review if you don’t know what it is, so ask. You can’t write a literature review if you don’t know how to find articles, so ask. The quickest way to learn is to ask questions. Once you stop caring if you look stupid, and once you realized no one thinks poorly of people who ask questions, life gets a lot easier.

So, let’s add this to our components of research: ask a question, determine what you need in order to thoroughly answer the question, and seek out your answers. Not too painful, and when you’re in love with whatever you’re researching, it might even be fun.

- When you have a question, ask it.

- When you’re genuinely interested in something, keep asking questions and finding answers.

- When you have a task at hand, take a second to think realistically about the information you’ll need to accomplish that task. You don’t need a peer-reviewed article to find out if praying mantises eat their mates, but you might if you want to find out why.

- What’s the last thing you looked up on Wikipedia? Did you stop when you found an answer, or did you click on another link and another link until you learned about something completely different?

- If you can’t remember, try it now! Search for something (like a favorite book or tv show) and click on linked words and phrases within Wikipedia until you learn something new!

- What was the last thing you researched that you were really excited about? Do you struggle when teachers and professors tell you to “research something that interests you”? Instead, try asking yourself, “What makes me really angry?” You might find you have more interests than you realized!

Scholarship as Conversation

We’ve made it friends! My favorite frame: “ Scholarship as Conversation .” Is it weird to have a favorite frame of information literacy? Probably. Am I going to talk about it anyway? You betcha!

What does “Scholarship as Conversation” mean?

Scholarship as conversation refers to the way scholars reference each other and build off of one another’s work, just like in a conversation. Have you ever had a conversation that started when you asked someone what they did last weekend and ended with you telling a story about how someone (definitely not you) ruined the cake at your mom’s dog’s birthday party? And then someone says, “but like I was saying earlier…” and they take the conversation back to a point in the conversation where they were reminded of a different point or story? Conversations aren’t linear, they aren’t a clear line to a clear destination, and neither is research. When we respond to the ideas and thoughts of scholars, we’re responding to the scholars themselves and engaging them in conversation.

Why do I Love this Frame so Much?

Let me count the ways.

I really enjoy the imagery of scholarship as a conversation among peers. Just a bunch of well-informed curious people coming together to talk about something they all love and find interesting. I imagine people literally sitting around a big round table talking about things they’re all excited about and want to share with each other. It’s a really lovely image in my head. Eventually the image kind of reshapes and devolves into that painting of dogs playing poker, but I love that image too!

It harkens back to pre-internet scholarship, which sounds excruciating and exhausting, but it was all done for the love of a subject. Scholars used to literally mail each other manuscripts seeking feedback. Then, when they got an article published in a journal, scholars interested in the subject would seek out and read the article in the physical journal it was published in. Then they’d write reviews of the article, praising or criticizing the author’s research or theories or style. As the field grew, more and more people would write and contribute more articles to criticize and praise and build off of one another.

So, for example, if I wrote an article that was about Big Foot and then Joe wrote an article saying, “Emily’s article on Big Foot is garbage; here’s what I think about Big Foot,” Sam and I are now having a conversation. It’s not always a fun one, but we’re writing in response to one another about something we’re both passionate about. Later, Jaiden comes along and disagrees with Joe and agrees with me (because I’m right) and they cite both me and Joe. Now we’re all three in a conversation. And it just grows and grows and more people show up at the table to talk and contribute, or maybe just to listen.

Reason Three

You can roll up to the table and just listen if you want to. Sometimes we’re just listening to the conversation. We’re at the table, but we’re not there to talk. We’re just hoping to get some questions answered and learn from some people. When we’re reading books and articles or listening to podcasts or watching movies, we’re listening to the conversation. You don’t have to do groundbreaking research to be part of a conversation. You can just be there and appreciate what everyone’s talking about. You’re still there in the conversation.

Reason Four

You can contribute to the conversation at any time. The imagery of a conversation is nice because it’s approachable: just pull up a chair and start talking. With any new subject, you should probably listen a little at first, ask some questions, and then start giving your own opinion or theories, but you can contribute at any time. Since we do live in the age of internet research, we can contribute in ways people 50 years ago never dreamed of. Besides writing essays in class (which totally counts because you’re examining the conversation and pulling in the bits you like and citing them to give credit to other scholars), you can talk to your professors and friends about a topic, you can blog about it, you can write articles about it, you can even tweet about it (have you ever seen Humanities folk on Twitter? They go nuts on there having actual, literal scholarly conversations). Your ways for engaging are kind of endless!

Reason Five

Yep, I’m listing reasons.

Conversations are cyclical. Like I said above, they’re not always a straight path and that’s true of research too. You don’t have to engage with who spoke most recently; you can engage with someone who spoke ten years ago, someone who spoke 100 years ago, you can even respond to the person who started the conversation! Jump in wherever you want. And wherever you do jump in, you might just change the course of the conversation. Because sometimes we think we have an answer, but then something new is discovered or a person who hadn’t been at the table or who had been overlooked says something that drastically impacts what we knew, so now we have to reexamine it all over again and continue the conversation in a trajectory we hadn’t realized was available before.

Lastly, this frame is about sharing and responding and valuing one another’s work. If Joe, my Big Foot nemesis, responds to my article, they’re going to cite me. If Jaiden then publishes a rebuttal, they’re going to cite both Joe and me, because fair is fair. This is for a few reasons: 1) even if Jaiden disagrees with Joe’s work, they respect that Joe put effort into it and it’s valuable to them. 2) When Jaiden cites Joe, it means anyone who jumps into the conversation at the point of Jaiden’s article will be able to backtrack and catch up using Jaiden’s citations. A newcomer can trace it back to Joe’s article and trace that back to mine. They can basically see a transcript of the whole conversation so they can read Jaiden’s article with all of the context, and they can write their own well-informed piece on Big Foot.

There’s a lot to take away from this frame, but here’s what I think is most important:

- Be respectful of other scholars’ work and their part in the conversation by citing them.

- Start talking whenever you feel ready, in whatever platform you feel comfortable.

- Make sure everyone who wants to be at the table is at the table. This means making sure information is available to those who want to listen and making sure we lift up the voices that are at risk of being drowned out.

- What scholarly conversations have you participated in recently? Is there a Reddit forum you look in on periodically to learn what’s new in the world of cats wearing hats? Or a Facebook group on roller skating? Do you contribute or just listen?

- Think of a scholarly conversation surrounding a topic—sharks, ballet, Game of Thrones. Who’s not at the table? Whose voice is missing from the conversation? Why do you think that is?

Searching as Strategic Exploration

You’ve made it! We’ve reached the last frame: Searching as Strategic Exploration .

“Searching as Strategic Exploration” addresses the part of information literacy that we think of as “Research.” It deals with the actual task of searching for information, and the word “Exploration” is a really good word choice, because it’s evocative of the kind of struggle we sometimes feel when we approach research. I imagine people exploring a jungle, facing obstacles and navigating an uncertain path towards an ultimate goal (Note: the goal is love and it was inside of us all along). I also kind of imagine all the different Northwest Passage explorations, which were cool in theory, but didn’t super-duper work out as expected.

But research is like that! Sometimes we don’t get where we thought we were headed. But the good news is this: You probably won’t die from exposure or resort to cannibalism in your research. Fun, right?

Step 1: Identify a Goal

The first part of any good exploration is identifying a goal. Maybe it’s a direct passage to Asia or the diamond the old lady threw into the ocean at the end of Titanic. More likely, the goal is to satisfy an information need. Remember when we talked about “Research as Inquiry?” All that stuff about paw patrol and Madonna’s skin care regimen? Those were examples of information needs. We’re just trying to find an answer or learn something new.

So great! Our goal is to learn something new. Now we make a strategy.

Step 2: Make a Strategy

For many of your information needs you might just need to Google a question. There’s your strategy: throw your question into Google and comb through the results. You might limit your search to just websites ending in .org, .gov, or .edu. You might also take it a step further and, rather than type in an entire question fully formed, you just type in keywords. So “Who is the guy who invented mayonnaise?” becomes “mayonnaise inventor.” Identifying keywords is part of your strategy and so is using a search engine and limiting the results you’re interested in.

Step 3: Start Exploring

Googling “mayonnaise inventor” probably brings you to Wikipedia where we often learn that our goals don’t have a single, clearly defined answer. For example, we learn that mayonnaise might have gotten its name after the French won a battle in Port Mahon, but that doesn’t tell us who actually made the mayonnaise, just when it was named. Prior to being named, the sauce was called “aioli bo” and was apparently in a Menorcan recipe book from 1745 by Juan de Altimiras. That’s great for Altimiras, but the most likely answer is that mayonnaise was invented way before him and he just had the foresight to write down the recipe. Not having a single definite answer is an unforeseen obstacle tossed into our path that now affects our strategy. We know we have a trickier question than when we first set sail.

But we have a lot to work with! We now have more keywords like “Port Mahon,” “the French,” and Wikipedia taught us that the earliest known mention of “mayonnaise” was in 1804, so we have “1804” as a keyword too.

Let’s see if we can find that original mention. Let’s take our keywords out of Wikipedia where we found them and voyage to a library’s website! At my library we have a tool that searches through all of our resources. We call it the “Quick Search.” You might have a library available to you, either at school, on a university’s campus, or a local public library. You can do research in any of these places!

So into the Quick Search tool (or whatever you have available to you) go our keywords: “1804,” “mayonnaise,” and “France.” The first result I see is an e-book by a guy who traveled to Paris in 1804, so that might be what we’re looking for. I search through the text and I do, in fact, find a reference to mayonnaise on page 99! The author (August von Kotzebue) is talking about how it’s hard to understand menus at French restaurants, for “What foreigner, for instance, would at first know what is meant by a mayonnaise de poulet, a galatine de volaille, a cotelette a la minute, or even an epigramme d’agneau?” He then goes on to recommend just ordering the fish, since you’ll know what you’ll get (Kotzebue 99).

So that doesn’t tell us who invented mayonnaise, but I think it’s pretty funny! So I’d call that detour a win.

Step 4: Reevaluate

When we hit ends that we don’t think are successful, we can always retrace our steps and reevaluate our question. Dead ends are a part of exploration! We’ve learned a lot, but we’ve also learned that maybe “who invented mayonnaise?” isn’t the right question. Maybe we should ask questions about the evolution of French cuisine or about ownership of culinary experimentation.

I’m going to stick with the history of mayonnaise, for just a little while longer, but my “1804 mayonnaise France” search wasn’t as helpful as I’d hoped, so I’ll try something new. Let’s try looking at encyclopedias.

I searched in a database called Credo Reference (which is a database filled with encyclopedia entries) and just searching “mayonnaise.” I can see that the first entry, “Minorca or Menorca” from The Companion to British History , doesn’t initially look helpful, but we’re exploring, so let’s click on it. It tells us that mayonnaise was invented in 1756 by a French commander’s cook and its name comes from Port Mahon where the French fended off the British during a siege ( Arnold-Baker, 2001 ). That’s awesome! It’s what Wikipedia told us! But let’s corroborate that fact. I click on The Hutchinson Chronology of World History entry for 1756, which says mayonnaise was invented in France in 1756 by the duc de Richelieu ( Helicon, 2018 ). I’m not sure I buy it. I could see a duke’s cook inventing mayonnaise, but I have a hard time imagining a duke and military commander taking the time to create a condiment.

But now I can go on to research the duc de Richelieu and his military campaigns and his culinary successes. Just typing “Duke de Richelieu” into the library’s Quick Search shows me a TON of books (16,742 as of writing this) on his life and he influence on France. So maybe now we’re actually exploring Richelieu or the intertwined history of French cuisine and the lives of nobility.

What Did We Just Do?

Our strategy for exploring this topic has had a lot of steps, but they weren’t random. It was a wild ride, but it was a strategic one. Let’s break the steps down real quick:

- We asked a question or identified a goal

- We identified keywords and googled them

- We learned some background information and got new keywords from Wikipedia and had to reevaluate our question

- We followed a lead to a book but hit a dead end when it wasn’t as useful as we’d hoped

- We identified an encyclopedia database and found several entries that support the theory we learned in Wikipedia, which forced us to reevaluate our question again

- We identified a key player in our topic and searched for him in the library’s Quick Search tool and the resources we found made us reevaluate our question yet again

Other strategies could include looking through an article’s reference list, working through a mind map , outlining your questions, or recording your steps in a research log so you don’t get lost—whatever works for you!

Exploration is tricky. Sometimes you circle back and ask different questions as new obstacles arise. Sometimes you have a clear path and you reach your goal instantly. But you can always retrace your steps, try new routes, discover new information, and maybe you’ll get to your destination in the end. Even if you don’t, you’ve learned something.

For instance, today we learned that if you can’t understand a menu in French, you should just order the fish.

- Where do you start a search for information? Do you start in different places when you have different information needs?

- If your research question was “What is the impact of fast fashion on carbon emissions?” What keywords would you use to start searching?

The Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education is one heck of a document. It’s complicated, its frames intertwine, it’s written in a way that can be tricky to understand. But essentially, it’s just trying to get us to understand that the ways we interact with information are complicated and we need to think about our interactions to make sure we’re behaving in an ethical and responsible way.

Why do your professors make you cite things? Because those citations are valuable to the original author, and they prove your engagement with the scholarly conversation. Why do we need to hold space in the conversation for voices that we haven’t heard from before? Because maybe no one recognized the authority in those voices before. The old process for creating information shut out lots of voices while prioritizing others. It’s important for us to recognize these nuances when we see what information is available to us and important for us to ask, “Whose voice isn’t here? Why? Am I looking hard enough for those voices? Can I help amplify them?” And it’s important for us to ask, “Why is the loudest voice being so loud? What motivates them? Why should I trust them over others?”

When we think critically about the information we access and the information we create and share, we’re engaging as citizens in one big global conversation. Making sure voices are heard, including your own voice, is what moves us all towards a more intelligent and understanding society.

Of course, part of thinking critically about information means thinking critically about both this guide and the framework. Lots of people have criticized the framework for including too much library jargon. Other folks think the framework needs to be rewritten to explicitly address how information seeking systems and publishing platforms have arisen from racist, sexist institutions. We won’t get into the criticisms here, but they’re important to think about. You can learn more about the criticism of the framework in a blog post by Ian Beilin , or you can do your own search for criticism on the framework to see what else is out there and form your own opinions.

The Final Takeaway

Ask questions, find information, and ask questions about that information.

Attributions

“A Beginner’s Guide to Introduction to Information Literacy” by Emily Metcalf is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA

Writing Arguments in STEM Copyright © by Jason Peters; Jennifer Bates; Erin Martin-Elston; Sadie Johann; Rebekah Maples; Anne Regan; and Morgan White is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

Information Literacy and Library Instruction: How Do I Write A Thesis Statement?

- IL Program - Documents, Procedures, and Policies

- Lessons and Exercises

- Professional Development

- Where Do I Start?

- How Do I Choose a Topic?

- Where Do I Find Information?

- How Do I Evaluate Sources?

- What Counts As Evidence?

- How Do I Write A Thesis Statement?

- How Do I Organize My Argument?

- How Do I Avoid Plagiarism and Find My Own Voice?

- What Do I Look For When I Revise?

- ResearchPath

Use Information - Part 6: How Do I Write A Thesis Statement?

Learning Objectives

- Researchers will know how to create a main claim, or thesis, that is debatable and provable.

- Researchers will understand how to narrow their thesis statement so that it's hard to refute.

- Researchers will understand how to use their thesis statement to forecast their arguments o rganization.

Thesis Statements as Debatable Claims

- Defines what a thesis statement is; must be debatable, not statement of fact

- Best for beginning level classes

- A good thesis statement must be provable

- Do not commit to a claim before research

- Best for beginning research instruction

Difficult to Refute

- A good thesis statement is difficult to prove wrong

- Explains how to narrow the scope of the topic

- Best for beginning to intermediate research instruction

Addresses Competing Claims

- Explains how to address alternative explanations of the thesis

Educates Readers

- Thesis should tell reader what to expect from paper

The Mechanics of Writing a Good Thesis Statement

- How to construct clear, concise thesis; one or two sentences

- Importance of thesis as outline of paper for reader

- Okay to tweak thesis throughout process

- Beginning level

Relevance Test

- Thesis helps determine what is relevant information

- Best for beginning and intermediate research instruction

- Gather and review a wide range of sources on your topic

- Look fir the key arguments in these sources

- Settle on a main claim that is provable with evidence you've found

- Make sure your main claim resists easy refutation by narrowing your scope and addressing competing claims

- Formulate your main claim in a one-to-two sentence thesis statement

- Revise your thesis statement to make sure it accurately reflects the organization of your argument

- Debatable Claims

- Thesis Statement

- << Previous: What Counts As Evidence?

- Next: How Do I Organize My Argument? >>

- Last Updated: Sep 14, 2023 5:34 PM

- URL: https://libguides.wmich.edu/info_lit

Information Literacy Resources

- Introduction

- Co-Curricular Activities

- Getting Started with Research

- Choosing a Topic

- Finding Information

- Evaluating Information

- Gathering Evidence

- Writing a Thesis Statement

- Organizing Your Argument

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Making Revisions

- Faculty Resources

Learning Objectives:

- Researchers will know how to create a main claim, or thesis, that is debatable and provable.

- Researchers will understand how to narrow their thesis statement so that it’s hard to refute

- Researchers will know how to acknowledge and address counterarguments in their thesis statement

- Researchers will understand how to use their thesis statement to forecast their argument’s organization

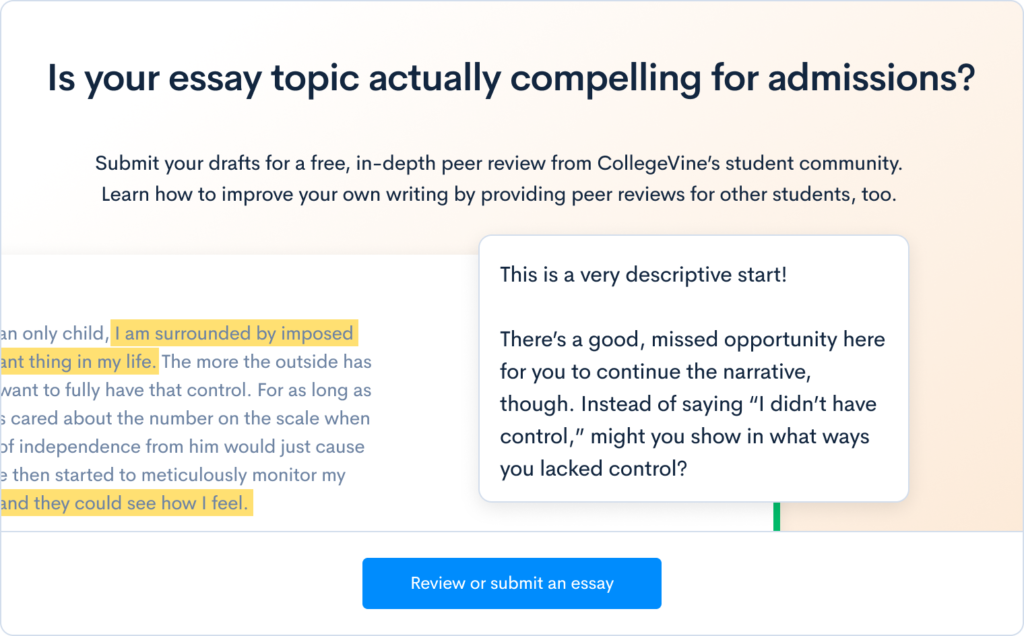

- Learning Module - Writing a thesis statement

Video Playlist Includes:

- Thesis statements as debatable claims (2:01)

- Provable (1:51)

- Difficult to refute (2:00)

- Addresses competing claims (1:50)

- Educates readers (0:52)

- The mechanics of writing a good thesis statement (1:44)

- Relevance test (1:00)

- << Previous: Gathering Evidence

- Next: Organizing Your Argument >>

- Last Updated: Mar 4, 2024 4:48 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.rpi.edu/InfoLit

- Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

- 110 Eighth Street | Troy, NY USA 12180

- (518) 276-6000

- Web Privacy

- Student Consumer Information

- Acessibility

Copyright © 2023 Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI)

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Information Literacy Basics

Introduction, ebooks + books, suggested websites.

- What is information literacy?

Information literacy is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.

Information literacy forms the basis for lifelong learning. It is common to all disciplines, to all learning environments, and to all levels of education. It enables learners to master content and extend their investigations, become more self-directed, and assume greater control over their own learning.

Association of College & Research Libraries

Image Credit: Pixabay

- Why Information Literacy is Important

- Choosing a Topic

- Pre-Research & Research

- Gathering Information About Your Topic

- The Thesis Statement

- Using Information Ethically

- Evaluating Sources

The skills of an information literate person extend beyond school and application to academic problems--such as writing a research paper--and reaches right into the workplace. Information literacy is also important to an effective and enlightened citizenry, and has implications that can impact the lives of many people around the globe.

The ability to use information technologies effectively to find and manage information, and the ability to critically evaluate and ethically apply that information to solve a problem are some of the hallmarks of an information literate individual. Other characteristics of an information literate individual include the spirit of inquiry and perseverance to find out what is necessary to get the job done.

We live in the Information Age, and "information" is increasing at a rapid pace. We have the Internet, television, radio, and other information resources available to us 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. However, just because so much information is so easily and quickly available does not mean that all of it is worthwhile or even true.

Because of resources like the Internet, finding high-quality information is now harder than ever, not easier! Finding the good stuff is not always quick. And the good stuff does not always come cheaply, either.

Today's employers are looking for people who understand and can adapt to the characteristics of the Information Age. If a student has "learned how to learn," upon graduation, they are a much more attractive job candidate. An information literate individual--with their strong analytical, critical thinking and problem-solving skills--can be expected to be an adaptable, capable and valuable employee, with much to contribute.

Philadelphia University

1. "Brainstorm" possible topics. This is often a successful way for you to get ideas down on paper. Jot down several ideas you may have - anything that comes to mind - any topic you want to explore. When you are done, see if anything stands out. This is a place to start. It is important to keep in mind that the initial topic you come up with may not be the topic you end up writing about. As you do research, you may change your mind and that's OK. It is part of the process.

2. An instructor may give you a list of acceptable topics to choose from. Pick one that interests you and decide what angle to take.

3. Go over lecture notes or textbook chapters for ideas.

4. Read current news stories in newspapers and magazines.

5. Check out the library's Research Guides (LibGuides).

Choose a topic that you are interested in. The research process is more relevant if you care about your topic!

Narrow your topic to something manageable. If your topic is too broad, you will find too much information and not be able to focus. Background reading can help you choose and limit the scope of your topic.

University of Michigan-Flint

Pre-Research

The beginning stages of research are often referred to as "pre-research." While you might be tempted to begin searching before completing these steps, the pre-research process will save you valuable time and effort. The first step in the pre-research process is to choose an interesting topic and create a research question. Next, using your research question, you can perform some background research to learn more about your topic. The background research will enable you to refine your topic and write a strong, focused thesis statement. Your thesis statement is what you will ultimately use to choose keywords and create search statements.

All of these steps are in preparation for using search tools, creating targeted searches, and retrieving the best information to use in your paper, project, or speech.

Research, in simplest terms, is information seeking. However, research is not just finding a piece of information. Instead, we can see research as a thorough examination of a topic. This process includes locating information, but also reflecting on what you've learned, adapting your ideas, organizing thoughts into a logical order, and then using those sources and ideas to produce a project or come to a decision.

Research in college is required for many papers, projects, and speeches. This does not mean you will be responsible for primary, or original, research. Primary research refers to collecting original data through surveys, experiments, interviews, or observations. Instead, the research you will conduct includes using search tools, like the library catalog, library databases, and the Web, to find existing credible research on a topic.

Seminole State College LIbrary

Finding background information on your topic is important if you are unfamiliar with the subject area. A background search can provide:

- A broad overview of the subject

- Definitions of the topic

- Introduction to key issues

- Names of people who are authorities in the subject field

- Major dates and events

- Keywords and subject-specific vocabulary terms that can be used for database searches

- Bibliographies that lead to additional resources

Encyclopedias are important sources to consider when initially researching a topic. General encyclopedias provide basic information on a wide range of subjects in an easily readable and understandable format.

If you are certain about what subject area you want to choose your topic from, you might want to use a specialized or subject encyclopedia instead. Subject encyclopedias limit their scope to one particular field of study, offering more detailed information about the subject.

Periodicals (also known as serials) are publications printed "periodically", either daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, or on an annual basis. Journals, magazines, and newspapers are different types of periodicals. Examples of periodicals include the following: newspapers, popular magazines, scholarly, peer-reviewed journals, trade publications.

Using search interfaces like Google can lead you to an ocean of good and bad information. Being critical of everything you see on the Internet is crucial when getting background information for an academic writing assignment. Instructors often prohibit students from citing Internet sites on a research paper so be careful that you understand what is acceptable and unacceptable to quote.

University of Buffalo LIbraries

Now that you've learned about your topic through background research and developed your topic into a research question, you can formulate a solid thesis statement. The thesis statement can be looked at as the answer to your research question. It guides the focus of your research and the direction of your arguments, and also prevents any unnecessary tangents within your project. A strong thesis statement will always make it easier to maintain a clear direction while conducting your information search.

Thesis statements are one sentence long and are focused, clear, declarative, and written in third person voice.

A good thesis statement should be:

Focus on a single position or point of view in your thesis statement. You cannot effectively address multiple perspectives within a single paper, as you want to make coherent points to support your position.

Present your argument or position clearly and precisely. A clear thesis statement will avoid generalizations and make your position known.

3. DECLARATIVE

Present your position or point of view as a statement or declarative sentence. Your research question helped guide your initial searching so you could learn more about your topic. Now that you have completed that step, you can extract a thesis statement based on the research you have discovered.

4. THIRD PERSON

Write your thesis statement in third person voice. Rather than addressing "I," "we," "you," "my," or "our" in your thesis, look at the larger issues that affect a greater number of participants. Think in terms like "citizens," "students," "artists," "teachers," "researchers," etc.

OWL Purdue Online Writing Lab

In a research project, you will use information and ideas from your research sources to support the statements you make. Whether those sources are books, articles, government documents, web pages, email, images, or any other types of sources, you must use them fairly and credit them appropriately.

You document, or cite, the information and ideas you use from your sources to give credit to the author or creator and to allow your readers to follow your research path.

Keep a record of all the information you will need from each source for your bibliography--author, title, journal title, date of publication, publisher and place of publication of a book, volume and issue number of a journal, page numbers. If your source is from the internet, such as a web page or email, record the address and date you accessed the document. You may want to save the document or print it out so you will have it as it existed on the date you accessed it.

Claremont Colleges Library

Need More Help?

When you need help with your research project, talk to your Instructor, stop by the library and ask for assistance from the librarian or make an appointment to get help from someone in the Writing Center on your campus.

How do you know if you have found “good” information? The CRAAP Test is a list of questions that you can use to evaluate the information that you find. These can be applied to websites, articles, and other information sources to help you determine if the information is reliable.

Evaluation Criteria

Currency: The timeliness of the information.

When was the information published or posted?

Has the information been revised or updated?

Does your topic require current information, or will older sources work as well?

Are the links functional?

Relevance: The importance of the information for your needs.

Does the information relate to your topic or answer your question?

Who is the intended audience?

Is the information at an appropriate level (i.e. not too elementary or advanced for your needs)?

Have you looked at a variety of sources before determining this is one you will use?

Would you be comfortable citing this source in your research paper?

Authority: The source of the information.

Who is the author/publisher/source/sponsor?

What are the author's credentials or organizational affiliations?

Is the author qualified to write on the topic?

Is there contact information, such as a publisher or email address?

Does the URL reveal anything about the author or source?

examples: .com .edu .gov .org .net

Accuracy: The reliability, truthfulness and correctness of the content.

Where does the information come from?

Is the information supported by evidence?

Has the information been reviewed or refereed?

Can you verify any of the information in another source or from personal knowledge?

Does the language or tone seem unbiased and free of emotion?

Are there spelling, grammar or typographical errors?

Purpose: The reason the information exists.

What is the purpose of the information? Is it to inform, teach, sell, entertain or persuade?

Do the authors/sponsors make their intentions or purpose clear?

Is the information fact, opinion or propaganda?

Does the point of view appear objective and impartial?

Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional or personal biases?

Adelphi University

Explore library databases .

Discover eBook collections or find print books/materials through the catalog for each campus:

Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education

A professional development resource that can be used and adapted by both individuals and groups in order to foster understanding and use of the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.

Project Information Literacy

A nonprofit research institute that conducts ongoing, national studies on what it is like being a student in the digital age.

- Introduction to Media Literacy

- Digital Literacy

First thing’s first: what is media literacy? Jay breaks this question down and explains how we’re going to use it to explore our media saturated world.

Learn how to find the information you need online in this episode of our Digital Literacy course – part of our 'Go The Distance' course, giving you the skills and knowledge you need to be a top-class distance learner!

- Last Updated: Apr 6, 2023 8:10 AM

- URL: https://libguides.cccneb.edu/infolit

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.