The Ultimate Grant Writing Guide (and How to Find and Apply for Grants)

Securing grants requires strategic planning. Identifying relevant opportunities, building collaborations, and crafting a comprehensive grant proposal are crucial steps. Read our ultimate guide on grant writing, finding grants, and applying for grants to get the funding for your research.

Updated on February 22, 2024

Embarking on a journey of groundbreaking research and innovation always requires more than just passion and dedication, it demands financial support. In the academic and research domains, securing grants is a pivotal factor for transforming these ideas into tangible outcomes.

Grant awards not only offer the backing needed for ambitious projects but also stand as a testament to the importance and potential impact of your work. The process of identifying, pursuing, and securing grants, however, is riddled with nuances that necessitate careful exploration.

Whether you're a seasoned researcher or a budding academic, navigating this complex world of grants can be challenging, but we’re here to help. In this comprehensive guide, we'll walk you through the essential steps of applying for grants, providing expert tips and insights along the way.

Finding grant opportunities

Prior to diving into the application phase, the process of finding grants involves researching and identifying those that are relevant and realistic to your project. While the initial step may seem as simple as entering a few keywords into a search engine, the full search phase takes a more thorough investigation.

By focusing efforts solely on the grants that align with your goals, this pre-application preparation streamlines the process while also increasing the likelihood of meeting all the requirements. In fact, having a well thought out plan and a clear understanding of the grants you seek both simplifies the entire activity and sets you and your team up for success.

Apply these steps when searching for appropriate grant opportunities:

1. Determine your need

Before embarking on the grant-seeking journey, clearly articulate why you need the funds and how they will be utilized. Understanding your financial requirements is crucial for effective grant research.

2. Know when you need the money

Grants operate on specific timelines with set award dates. Align your grant-seeking efforts with these timelines to enhance your chances of success.

3. Search strategically

Build a checklist of your most important, non-negotiable search criteria for quickly weeding out grant options that absolutely do not fit your project. Then, utilize the following resources to identify potential grants:

- Online directories

- Small Business Administration (SBA)

- Foundations

4. Develop a tracking tool

After familiarizing yourself with the criteria of each grant, including paperwork, deadlines, and award amounts, make a spreadsheet or use a project management tool to stay organized. Share this with your team to ensure that everyone can contribute to the grant cycle.

Here are a few popular grant management tools to try:

- Jotform : spreadsheet template

- Airtable : table template

- Instrumentl : software

- Submit : software

Tips for Finding Research Grants

Consider large funding sources : Explore major agencies like NSF and NIH.

Reach out to experts : Consult experienced researchers and your institution's grant office.

Stay informed : Regularly check news in your field for novel funding sources.

Know agency requirements : Research and align your proposal with their requisites.

Ask questions : Use the available resources to get insights into the process.

Demonstrate expertise : Showcase your team's knowledge and background.

Neglect lesser-known sources : Cast a wide net to diversify opportunities.

Name drop reviewers : Prevent potential conflicts of interest.

Miss your chance : Find field-specific grant options.

Forget refinement : Improve proposal language, grammar, and clarity.

Ignore grant support services : Enhance the quality of your proposal.

Overlook co-investigators : Enhance your application by adding experience.

Grant collaboration

Now that you’ve taken the initial step of identifying potential grant opportunities, it’s time to find collaborators. The application process is lengthy and arduous. It requires a diverse set of skills. This phase is crucial for success.

With their valuable expertise and unique perspectives, these collaborators play instrumental roles in navigating the complexities of grant writing. While exploring the judiciousness that goes into building these partnerships, we will underscore why collaboration is both advantageous and indispensable to the pursuit of securing grants.

Why is collaboration important to the grant process?

Some grant funding agencies outline collaboration as an outright requirement for acceptable applications. However, the condition is more implied with others. Funders may simply favor or seek out applications that represent multidisciplinary and multinational projects.

To get an idea of the types of collaboration major funders prefer, try searching “collaborative research grants” to uncover countless possibilities, such as:

- National Endowment for the Humanities

- American Brain Tumor Association

For exploring grants specifically for international collaboration, check out this blog:

- 30+ Research Funding Agencies That Support International Collaboration

Either way, proposing an interdisciplinary research project substantially increases your funding opportunities. Teaming up with multiple collaborators who offer diverse backgrounds and skill sets enhances the robustness of your research project and increases credibility.

This is especially true for early career researchers, who can leverage collaboration with industry, international, or community partners to boost their research profile. The key lies in recognizing the multifaceted advantages of collaboration in the context of obtaining funding and maximizing the impact of your research efforts.

How can I find collaborators?

Before embarking on the search for a collaborative partner, it's essential to crystallize your objectives for the grant proposal and identify the type of support needed. Ask yourself these questions:

1)Which facet of the grant process do I need assistance with:

2) Is my knowledge lacking in a specific:

- Population?

3) Do I have access to the necessary:

Use these questions to compile a detailed list of your needs and prioritize them based on magnitude and ramification. These preliminary step ensure that search for an ideal collaborator is focused and effective.

Once you identify targeted criteria for the most appropriate partners, it’s time to make your approach. While a practical starting point involves reaching out to peers, mentors, and other colleagues with shared interests and research goals, we encourage you to go outside your comfort zone.

Beyond the first line of potential collaborators exists a world of opportunities to expand your network. Uncover partnership possibilities by engaging with speakers and attendees at events, workshops, webinars, and conferences related to grant writing or your field.

Also, consider joining online communities that facilitate connections among grant writers and researchers. These communities offer a space to exchange ideas and information. Sites like Collaboratory , NIH RePorter , and upwork provide channels for canvassing and engaging with feasible collaborators who are good fits for your project.

Like any other partnership, carefully weigh your vetted options before committing to a collaboration. Talk with individuals about their qualifications and experience, availability and work style, and terms for grant writing collaborations.

Transparency on both sides of this partnership is imperative to forging a positive work environment where goals, values, and expectations align for a strong grant proposal.

Putting together a winning grant proposal

It’s time to assemble the bulk of your grant application packet – the proposal itself. Each funder is unique in outlining the details for specific grants, but here are several elements fundamental to every proposal:

- Executive Summary

- Needs assessment

- Project description

- Evaluation plan

- Team introduction

- Sustainability plan

This list of multi-faceted components may seem daunting, but careful research and planning will make it manageable.

Start by reading about the grant funder to learn:

- What their mission and goals are,

- Which types of projects they have funded in the past, and

- How they evaluate and score applications.

Next, view sample applications to get a feel for the length, flow, and tone the evaluators are looking for. Many funders offer samples to peruse, like these from the NIH , while others are curated by online platforms , such as Grantstation.

Also, closely evaluate the grant application’s requirements. they vary between funding organizations and opportunities, and also from one grant cycle to the next. Take notes and make a checklist of these requirements to add to an Excel spreadsheet, Google smartsheet, or management system for organizing and tracking your grant process.

Finally, understand how you will submit the final grant application. Many funders use online portals with character or word limits for each section. Be aware of these limits beforehand. Simplify the editing process by first writing each section in a Word document to be copy and pasted into the corresponding submission fields.

If there is no online application platform, the funder will usually offer a comprehensive Request for Proposal (RFP) to guide the structure of your grant proposal. The RFP:

- Specifies page constraints

- Delineates specific sections

- Outlines additional attachments

- Provides other pertinent details

Components of a grant proposal

Cover letter.

Though not always explicitly requested, including a cover letter is a strategic maneuver that could be the factor determining whether or not grant funders engage with your proposal. It’s an opportunity to give your best first impression by grabbing the reviewer’s attention and compelling them to read further.

Cover letters are not the place for excessive emotion or detail, keep it brief and direct, stating your financial needs and purpose confidently from the outset. Also, try to clearly demonstrate the connection between your project and the funder’s mission to create additional value beyond the formal proposal.

Executive summary

Like an abstract for your research manuscript, the executive summary is a brief synopsis that encapsulates the overarching topics and key points of your grant proposal. It must set the tone for the main body of the proposal while providing enough information to stand alone if necessary.

Refer to How to Write an Executive Summary for a Grant Proposal for detailed guidance like:

- Give a clear and concise account of your identity, funding needs, and project roadmap.

- Write in an instructive manner aiming for an objective and persuasive tone

- Be convincing and pragmatic about your research team's ability.

- Follow the logical flow of main points in your proposal.

- Use subheadings and bulleted lists for clarity.

- Write the executive summary at the end of the proposal process.

- Reference detailed information explained in the proposal body.

- Address the funder directly.

- Provide excessive details about your project's accomplishments or management plans.

- Write in the first person.

- Disclose confidential information that could be accessed by competitors.

- Focus excessively on problems rather than proposed solutions.

- Deviate from the logical flow of the main proposal.

- Forget to align with evaluation criteria if specified

Project narrative

After the executive summary is the project narrative . This is the main body of your grant proposal and encompasses several distinct elements that work together to tell the story of your project and justify the need for funding.

Include these primary components:

Introduction of the project team

Briefly outline the names, positions, and credentials of the project’s directors, key personnel, contributors, and advisors in a format that clearly defines their roles and responsibilities. Showing your team’s capacity and ability to meet all deliverables builds confidence and trust with the reviewers.

Needs assessment or problem statement

A compelling needs assessment (or problem statement) clearly articulates a problem that must be urgently addressed. It also offers a well-defined project idea as a possible solution. This statement emphasizes the pressing situation and highlights existing gaps and their consequences to illustrate how your project will make a difference.

To begin, ask yourself these questions:

- What urgent need are we focusing on with this project?

- Which unique solution does our project offer to this urgent need?

- How will this project positively impact the world once completed?

Here are some helpful examples and templates.

Goals and objectives

Goals are broad statements that are fairly abstract and intangible. Objectives are more narrow statements that are concrete and measurable. For example :

- Goal : “To explore the impact of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance in college students.”

- Objective : “To compare cognitive test scores of students with less than six hours of sleep and those with 8 or more hours of sleep.”

Focus on outcomes, not processes, when crafting goals and objectives. Use the SMART acronym to align them with the proposal's mission while emphasizing their impact on the target audience.

Methods and strategies

It is vitally important to explain how you intend to use the grant funds to fulfill the project’s objectives. Detail the resources and activities that will be employed. Methods and strategies are the bridge between idea and action. They must prove to reviewers the plausibility of your project and the significance of their possible funding.

Here are some useful guidelines for writing your methods section that are outlined in " Winning Grants: Step by Step ."

- Firmly tie your methods to the proposed project's objectives and needs assessment.

- Clearly link them to the resources you are requesting in the proposal budget.

- Thoroughly explain why you chose these methods by including research, expert opinion, and your experience.

- Precisely list the facilities and capital equipment that you will use in the project.

- Carefully structure activities so that the program moves toward the desired results in a time-bound manner.

A comprehensive evaluation plan underscores the effectiveness and accountability of a project for both the funders and your team. An evaluation is used for tracking progress and success. The evaluation process shows how to determine the success of your project and measure the impact of the grant award by systematically gauging and analyzing each phase of your project as it compares to the set objectives.

Evaluations typically fall into two standard categories:

1. Formative evaluation : extending from project development through implementation, continuously provides feedback for necessary adjustments and improvements.

2. Summative evaluation : conducted post-project completion, critically assesses overall success and impact by compiling information on activities and outcomes.

Creating a conceptual model of your project is helpful when identifying these key evaluation points. Then, you must consider exactly who will do the evaluations, what specific skills and resources they need, how long it will take, and how much it will cost.

Sustainability

Presenting a solid plan that illustrates exactly how your project will continue to thrive after the grant money is gone builds the funder's confidence in the project’s longevity and significance. In this sustainability section, it is vital to demonstrate a diversified funding strategy for securing the long-term viability of your program.

There are three possible long term outcomes for projects with correlated sustainability options:

- Short term projects: Though only implemented once, will have ongoing maintenance costs, such as monitoring, training, and updates.

(E.g., digitizing records, cleaning up after an oil spill)

- Projects that will generate income at some point in the future: must be funded until your product or service can cover operating costs with an alternative plan in place for deficits.

(E.g., medical device, technology, farming method)

- Ongoing projects: will eventually need a continuous stream of funding from a government entity or large organization.

(E.g., space exploration, hurricane tracking)

Along with strategies for funding your program beyond the initial grant, reference your access to institutional infrastructure and resources that will reduce costs.

Also, submit multi-year budgets that reflect how sustainability factors are integrated into the project’s design.

The budget section of your grant proposal, comprising both a spreadsheet and a narrative, is the most influential component. It should be able to stand independently as a suitable representation of the entire endeavor. Providing a detailed plan to outline how grant funds will be utilized is crucial for illustrating cost-effectiveness and careful consideration of project expenses.

A comprehensive grant budget offers numerous benefits to both the grantor , or entity funding the grant, and the grantee , those receiving the funding, such as:

- Grantor : The budget facilitates objective evaluation and comparison between multiple proposals by conveying a project's story through responsible fund management and financial transparency.

- Grantee : The budget serves as a tracking tool for monitoring and adjusting expenses throughout the project and cultivates trust with funders by answering questions before they arise.

Because the grant proposal budget is all-encompassing and integral to your efforts for securing funding, it can seem overwhelming. Start by listing all anticipated expenditures within two broad categories, direct and indirect expenses , where:

- Direct : are essential for successful project implementation, are measurable project-associated costs, such as salaries, equipment, supplies, travel, and external consultants, and are itemized and detailed in various categories within the grant budget.

- Indirect : includes administrative costs not directly or exclusively tied to your project, but necessary for its completion, like rent, utilities, and insurance, think about lab or meeting spaces that are shared by multiple project teams, or Directors who oversee several ongoing projects.

After compiling your list, review sample budgets to understand the typical layout and complexity. Focus closely on the budget narratives , where you have the opportunity to justify each aspect of the spreadsheet to ensure clarity and validity.

While not always needed, the appendices consist of relevant supplementary materials that are clearly referenced within your grant application. These might include:

- Updated resumes that emphasize staff members' current positions and accomplishments.

- Letters of support from people or organizations that have authority in the field of your research, or community members that may benefit from the project.

- Visual aids like charts, graphs, and maps that contribute directly to your project’s story and are referred to previously in the application.

Finalizing your grant application

Now that your grant application is finished, make sure it's not just another document in the stack Aim for a grant proposal that captivates the evaluator. It should stand out not only for presenting an excellent project, but for being engaging and easily comprehended .

Keep the language simple. Avoid jargon. Prioritizing accuracy and conciseness. Opt for reader-friendly formatting with white space, headings, standard fonts, and illustrations to enhance readability.

Always take time for thorough proofreading and editing. You can even set your proposal aside for a few days before revisiting it for additional edits and improvements. At this stage, it is helpful to seek outside feedback from those familiar with the subject matter as well as novices to catch unnoticed mistakes and improve clarity.

If you want to be absolutely sure your grant proposal is polished, consider getting it edited by AJE .

How can AI help the grant process?

When used efficiently, AI is a powerful tool for streamlining and enhancing various aspects of the grant process.

- Use AI algorithms to review related studies and identify knowledge gaps.

- Employ AI for quick analysis of complex datasets to identify patterns and trends.

- Leverage AI algorithms to match your project with relevant grant opportunities.

- Apply Natural Language Processing for analyzing grant guidelines and tailoring proposals accordingly.

- Utilize AI-powered tools for efficient project planning and execution.

- Employ AI for tracking project progress and generating reports.

- Take advantage of AI tools for improving the clarity, coherence, and quality of your proposal.

- Rely solely on manual efforts that are less comprehensive and more time consuming.

- Overlook the fact that AI is designed to find patterns and trends within large datasets.

- Minimize AI’s ability to use set parameters for sifting through vast amounts of data quickly.

- Forget that the strength of AI lies in its capacity to follow your prompts without divergence.

- Neglect tools that assist with scheduling, resource allocation, and milestone tracking.

- Settle for software that is not intuitive with automated reminders and updates.

- Hesitate to use AI tools for improving grammar, spelling, and composition throughout the writing process.

Remember that AI provides a diverse array of tools; there is no universal solution. Identify the most suitable tool for your specific task. Also, like a screwdriver or a hammer, AI needs informed human direction and control to work effectively.

Looking for tips when writing your grant application?

Check out these resources:

- 4 Tips for Writing a Persuasive Grant Proposal

- Writing Effective Grant Applications

- 7 Tips for Writing an Effective Grant Proposal

- The best-kept secrets to winning grants

- The Best Grant Writing Books for Beginner Grant Writers

- Research Grant Proposal Funding: How I got $1 Million

Final thoughts

The bottom line – applying for grants is challenging. It requires passion, dedication, and a set of diverse skills rarely found within one human being.

Therefore, collaboration is key to a successful grant process . It encourages everyone’s strengths to shine. Be honest and ask yourself, “Which elements of this grant application do I really need help with?” Seek out experts in those areas.

Keep this guide on hand to reference as you work your way through this funding journey. Use the resources contained within. Seek out answers to all the questions that will inevitably arise throughout the process.

The grants are out there just waiting for the right project to present itself – one that shares the funder’s mission and is a benefit to our communities. Find grants that align with your project goals, tell your story through a compelling proposal, and get ready to make the world a better place with your research.

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a grant proposal: a step-by-step guide

What is a grant proposal?

Why should you write a grant proposal, format of a grant proposal, how to write a grant proposal, step 1: decide what funding opportunity to apply for, and research the grant application process, step 2: plan and research your project, preliminary research for your grant proposal, questions to ask yourself as you plan your grant proposal, developing your grant proposal, step 3: write the first draft of your grant proposal, step 4: get feedback, and revise your grant proposal accordingly, step 5: prepare to submit your grant proposal, what happens after submitting the grant proposal, final thoughts, other useful sources for writing grant proposals, frequently asked questions about writing grant proposals, related articles.

You have a vision for a future research project, and want to share that idea with the world.

To achieve your vision, you need funding from a sponsoring organization, and consequently, you need to write a grant proposal.

Although visualizing your future research through grant writing is exciting, it can also feel daunting. How do you start writing a grant proposal? How do you increase your chances of success in winning a grant?

But, writing a proposal is not as hard as you think. That’s because the grant-writing process can be broken down into actionable steps.

This guide provides a step-by-step approach to grant-writing that includes researching the application process, planning your research project, and writing the proposal. It is written from extensive research into grant-writing, and our experiences of writing proposals as graduate students, postdocs, and faculty in the sciences.

A grant proposal is a document or collection of documents that outlines the strategy for a future research project and is submitted to a sponsoring organization with the specific goal of getting funding to support the research. For example, grants for large projects with multiple researchers may be used to purchase lab equipment, provide stipends for graduate and undergraduate researchers, fund conference travel, and support the salaries of research personnel.

As a graduate student, you might apply for a PhD scholarship, or postdoctoral fellowship, and may need to write a proposal as part of your application. As a faculty member of a university, you may need to provide evidence of having submitted grant applications to obtain a permanent position or promotion.

Reasons for writing a grant proposal include:

- To obtain financial support for graduate or postdoctoral studies;

- To travel to a field site, or to travel to meet with collaborators;

- To conduct preliminary research for a larger project;

- To obtain a visiting position at another institution;

- To support undergraduate student research as a faculty member;

- To obtain funding for a large collaborative project, which may be needed to retain employment at a university.

The experience of writing a proposal can be helpful, even if you fail to obtain funding. Benefits include:

- Improvement of your research and writing skills

- Enhancement of academic employment prospects, as fellowships and grants awarded and applied for can be listed on your academic CV

- Raising your profile as an independent academic researcher because writing proposals can help you become known to leaders in your field.

All sponsoring agencies have specific requirements for the format of a grant proposal. For example, for a PhD scholarship or postdoctoral fellowship, you may be required to include a description of your project, an academic CV, and letters of support from mentors or collaborators.

For a large research project with many collaborators, the collection of documents that need to be submitted may be extensive. Examples of documents that might be required include a cover letter, a project summary, a detailed description of the proposed research, a budget, a document justifying the budget, and the CVs of all research personnel.

Before writing your proposal, be sure to note the list of required documents.

Writing a grant proposal can be broken down into three major activities: researching the project (reading background materials, note-taking, preliminary work, etc.), writing the proposal (creating an outline, writing the first draft, revisions, formatting), and administrative tasks for the project (emails, phone calls, meetings, writing CVs and other supporting documents, etc.).

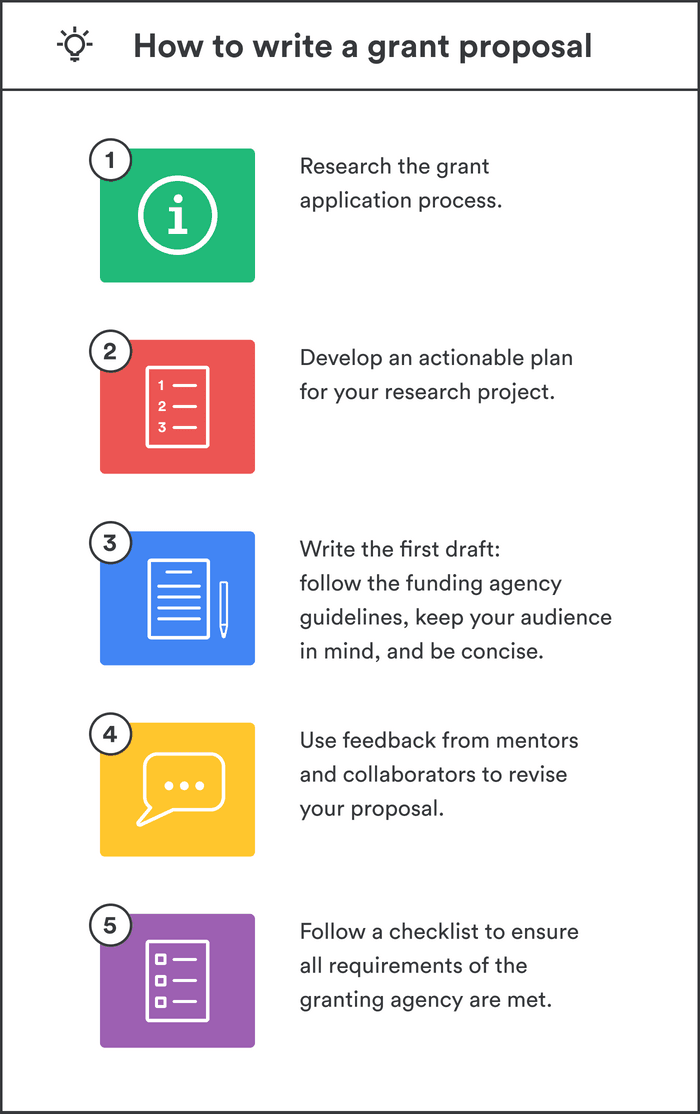

Below, we provide a step-by-step guide to writing a grant proposal:

- Decide what funding opportunity to apply for, and research the grant application process

- Plan and research your project

- Write the first draft of your grant proposal

- Get feedback, and revise your grant proposal accordingly

- Prepare to submit your grant proposal

- Start early. Begin by searching for funding opportunities and determining requirements. Some sponsoring organizations prioritize fundamental research, whereas others support applied research. Be sure your project fits the mission statement of the granting organization. Look at recently funded proposals and/or sample proposals on the agency website, if available. The Research or Grants Office at your institution may be able to help with finding grant opportunities.

- Make a spreadsheet of grant opportunities, with a link to the call for proposals page, the mission and aims of the agency, and the deadline for submission. Use the information that you have compiled in your spreadsheet to decide what to apply for.

- Once you have made your decision, carefully read the instructions in the call for proposals. Make a list of all the documents you need to apply, and note the formatting requirements and page limits. Know exactly what the funding agency requires of submitted proposals.

- Reach out to support staff at your university (for example, at your Research or Grants Office), potential mentors, or collaborators. For example, internal deadlines for submitting external grants are often earlier than the submission date. Make sure to learn about your institution’s internal processes, and obtain contact information for the relevant support staff.

- Applying for a grant or fellowship involves administrative work. Start preparing your CV and begin collecting supporting documents from collaborators, such as letters of support. If the application to the sponsoring agency is electronic, schedule time to set up an account, log into the system, download necessary forms and paperwork, etc. Don’t leave all of the administrative tasks until the end.

- Map out the important deadlines on your calendar. These might include video calls with collaborators, a date for the first draft to be complete, internal submission deadlines, and the funding agency deadline.

- Schedule time on your calendar for research, writing, and administrative tasks associated with the project. It’s wise to group similar tasks and block out time for them (a process known as ” time batching ”). Break down bigger tasks into smaller ones.

Now that you know what you are applying for, you can think about matching your proposed research to the aims of the agency. The work you propose needs to be innovative, specific, realizable, timely, and worthy of the sponsoring organization’s attention.

- Develop an awareness of the important problems and open questions in your field. Attend conferences and seminar talks and follow all of your field’s major journals.

- Read widely and deeply. Journal review articles are a helpful place to start. Reading papers from related but different subfields can generate ideas. Taking detailed notes as you read will help you recall the important findings and connect disparate concepts.

- Writing a grant proposal is a creative and imaginative endeavor. Write down all of your ideas. Freewriting is a practice where you write down all that comes to mind without filtering your ideas for feasibility or stopping to edit mistakes. By continuously writing your thoughts without judgment, the practice can help overcome procrastination and writer’s block. It can also unleash your creativity, and generate new ideas and associations. Mind mapping is another technique for brainstorming and generating connections between ideas.

- Establish a regular writing practice. Schedule time just for writing, and turn off all distractions during your focused work time. You can use your writing process to refine your thoughts and ideas.

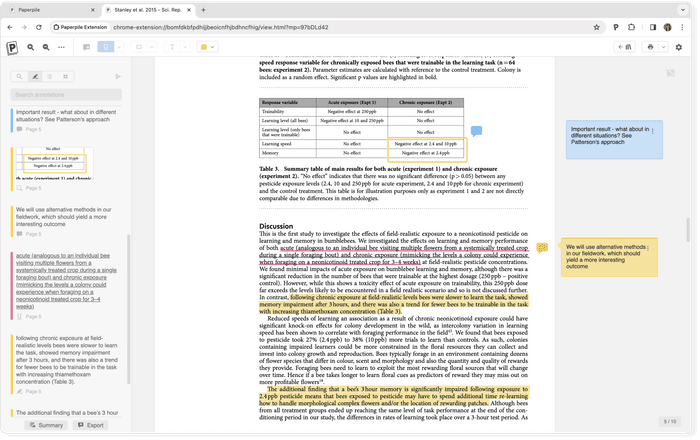

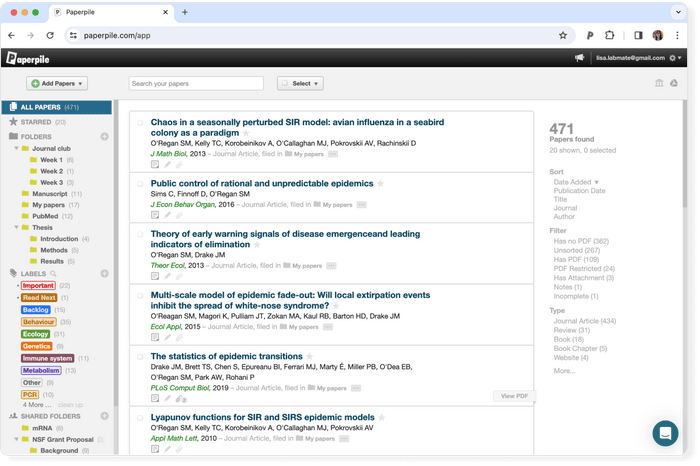

- Use a reference manager to build a library of sources for your project. You can use a reference management tool to collect papers , store and organize references , and highlight and annotate PDFs . Establish a system for organizing your ideas by tagging papers with labels and using folders to store similar references.

To facilitate intelligent thinking and shape the overall direction of your project, try answering the following questions:

- What are the questions that the project will address? Am I excited and curious about their answers?

- Why are these questions important?

- What are the goals of the project? Are they SMART (Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Relevant, and Timely)?

- What is novel about my project? What is the gap in current knowledge?

- What methods will I use, and how feasible is my approach?

- Can the work be done over the proposed period, and with the budget I am requesting?

- Do I have relevant experience? For example, have I completed similar work funded by previous grants or written papers on my proposed topic?

- What pilot research or prior work can I use, or do I need to complete preliminary research before writing the proposal?

- Will the outcomes of my work be consequential? Will the granting agency be interested in the results?

- What solutions to open problems in my field will this project offer? Are there broader implications of my work?

- Who will the project involve? Do I need mentors, collaborators, or students to contribute to the proposed work? If so, what roles will they have?

- Who will read the proposal? For example, experts in the field will require details of methods, statistical analyses, etc., whereas non-experts may be more concerned with the big picture.

- What do I want the reviewers to feel, and take away from reading my proposal?

- What weaknesses does my proposed research have? What objections might reviewers raise, and how can I address them?

- Can I visualize a timeline for my project?

Create an actionable plan for your research project using the answers to these questions.

- Now is the time to collect preliminary data, conduct experiments, or do a preliminary study to motivate your research, and demonstrate that your proposed project is realistic.

- Use your plan to write a detailed outline of the proposal. An outline helps you to write a proposal that has a logical format and ensures your thought process is rational. It also provides a structure to support your writing.

- Follow the granting agency’s guidelines for titles, sections, and subsections to inform your outline.

At this stage, you should have identified the aims of your project, what questions your work will answer, and how they are relevant to the sponsoring agency’s call for proposals. Be able to explain the originality, importance, and achievability of your proposed work.

Now that you have done your research, you are ready to begin writing your proposal and start filling in the details of your outline. Build on the writing routine you have already started. Here are some tips:

- Follow the guidelines of the funding organization.

- Keep the proposal reviewers in mind as you write. Your audience may be a combination of specialists in your field and non-specialists. Make sure to address the novelty of your work, its significance, and its feasibility.

- Write clearly, concisely, and avoid repetition. Use topic sentences for each paragraph to emphasize key ideas. Concluding sentences of each paragraph should develop, clarify, or summarize the support for the declaration in the topic sentence. To make your writing engaging, vary sentence length.

- Avoid jargon, where possible. Follow sentences that have complex technical information with a summary in plain language.

- Don’t review all information on the topic, but include enough background information to convince reviewers that you are knowledgeable about it. Include preliminary data to convince reviewers you can do the work. Cite all relevant work.

- Make sure not to be overly ambitious. Don’t propose to do so much that reviewers doubt your ability to complete the project. Rather, a project with clear, narrowly-defined goals may prove favorable to reviewers.

- Accurately represent the scope of your project; don’t exaggerate its impacts. Avoid bias. Be forthright about the limitations of your research.

- Ensure to address potential objections and concerns that reviewers may have with the proposed work. Show that you have carefully thought about the project by explaining your rationale.

- Use diagrams and figures effectively. Make sure they are not too small or contain too much information or details.

After writing your first draft, read it carefully to gain an overview of the logic of your argument. Answer the following questions:

- Is your proposal concise, explicit, and specific?

- Have you included all necessary assumptions, data points, and evidence in your proposal?

- Do you need to make structural changes like moving or deleting paragraphs or including additional tables or figures to strengthen your rationale?

- Have you answered most of the questions posed in Step 2 above in your proposal?

- Follow the length requirements in the proposal guidelines. Don't feel compelled to include everything you know!

- Use formatting techniques to make your proposal easy on the eye. Follow rules for font, layout, margins, citation styles , etc. Avoid walls of text. Use bolding and italicizing to emphasize points.

- Comply with all style, organization, and reference list guidelines to make it easy to reviewers to quickly understand your argument. If you don’t, it’s at best a chore for the reviewers to read because it doesn’t make the most convincing case for you and your work. At worst, your proposal may be rejected by the sponsoring agency without review.

- Using a reference management tool like Paperpile will make citation creation and formatting in your grant proposal quick, easy and accurate.

Now take time away from your proposal, for at least a week or more. Ask trusted mentors or collaborators to read it, and give them adequate time to give critical feedback.

- At this stage, you can return to any remaining administrative work while you wait for feedback on the proposal, such as finalizing your budget or updating your CV.

- Revise the proposal based on the feedback you receive.

- Don’t be discouraged by critiques of your proposal or take them personally. Receiving and incorporating feedback with humility is essential to grow as a grant writer.

Now you are almost ready to submit. This is exciting! At this stage, you need to block out time to complete all final checks.

- Allow time for proofreading and final editing. Spelling and grammar mistakes can raise questions regarding the rigor of your research and leave a poor impression of your proposal on reviewers. Ensure that a unified narrative is threaded throughout all documents in the application.

- Finalize your documents by following a checklist. Make sure all documents are in place in the application, and all formatting and organizational requirements are met.

- Follow all internal and external procedures. Have login information for granting agency and institution portals to hand. Double-check any internal procedures required by your institution (applications for large grants often have a deadline for sign-off by your institution’s Research or Grants Office that is earlier than the funding agency deadline).

- To avoid technical issues with electronic portals, submit your proposal as early as you can.

- Breathe a sigh of relief when all the work is done, and take time to celebrate submitting the proposal! This is already a big achievement.

Now you wait! If the news is positive, congratulations!

But if your proposal is rejected, take heart in the fact that the process of writing it has been useful for your professional growth, and for developing your ideas.

Bear in mind that because grants are often highly competitive, acceptance rates for proposals are usually low. It is very typical to not be successful on the first try and to have to apply for the same grant multiple times.

Here are some tips to increase your chances of success on your next attempt:

- Remember that grant writing is often not a linear process. It is typical to have to use the reviews to revise and resubmit your proposal.

- Carefully read the reviews and incorporate the feedback into the next iteration of your proposal. Use the feedback to improve and refine your ideas.

- Don’t ignore the comments received from reviewers—be sure to address their objections in your next proposal. You may decide to include a section with a response to the reviewers, to show the sponsoring agency that you have carefully considered their comments.

- If you did not receive reviewer feedback, you can usually request it.

You learn about your field and grow intellectually from writing a proposal. The process of researching, writing, and revising a proposal refines your ideas and may create new directions for future projects. Professional opportunities exist for researchers who are willing to persevere with submitting grant applications.

➡️ Secrets to writing a winning grant

➡️ How to gain a competitive edge in grant writing

➡️ Ten simple rules for writing a postdoctoral fellowship

A grant proposal should include all the documents listed as required by the sponsoring organization. Check what documents the granting agency needs before you start writing the proposal.

Granting agencies have strict formatting requirements, with strict page limits and/or word counts. Check the maximum length required by the granting agency. It is okay for the proposal to be shorter than the maximum length.

Expect to spend many hours, even weeks, researching and writing a grant proposal. Consequently, it is important to start early! Block time in your calendar for research, writing, and administration tasks. Allow extra time at the end of the grant-writing process to edit, proofread, and meet presentation guidelines.

The most important part of a grant proposal is the description of the project. Make sure that the research you propose in your project narrative is new, important, and viable, and that it meets the goals of the sponsoring organization.

A grant proposal typically consists of a set of documents. Funding agencies have specific requirements for the formatting and organization of each document. Make sure to follow their guidelines exactly.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Overview on Grant Writing for Graduate Student Research

Diane smith.

Biomolecular Research Center, 1910 University Drive, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho, 83725

Abu Sayeed Chowdhury

Biomolecular Sciences Graduate Programs, 1910 University Drive, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho, 83725

Julia Thom Oxford

Grant writing is an important skill to develop during graduate school. This article provides an overview of grant writing for graduate students. Specific topics covered include understanding your funding needs, identifying appropriate grant opportunities, analyzing the guidelines for the proposal, planning and time management, understanding the priorities of the funding agency or organization, proposal organization and writing strategies, additional forms and letters of support that may be required, the editing and revising process, and submission of your grant proposal. Courses and workshops are an efficient and effective way to be guided through the grant proposal writing process with a greater potential for positive outcomes.

INTRODUCTION:

Effective communication is one of the most important skills for students pursuing a career in research to develop. Grant proposal writing is a skill that is essential to career success, and a skill that can be learned while in graduate school. While this skill is recognized as essential, the necessary training is not always available to students in graduate programs and students may struggle with crafting successful grant applications to support their research. To address this limitation, we provide an overview of grant writing for student research projects. Honing these skills while a student can set the stage for a successful postdoctoral fellowship and early career success as a young faculty member.

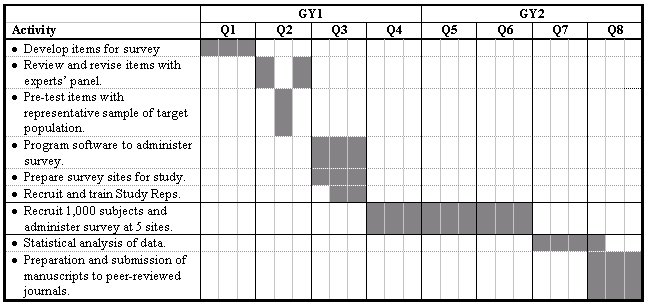

An overview of specific elements of successful grant proposal preparation include having a good understanding of the funding needs for the research that will be performed. Additionally, it is essential to identify the appropriate funding opportunity for the specific project and for the investigator at the specific career stage. Taking the necessary time to carefully read and analyze the guidelines for the specific proposal is critical for success. Planning for the proposal preparation and time management skills are among the most important aspects of a successful proposal. Graduate school is an ideal time to develop good writing habits, that include writing each day. To be successful, it is important to understand the priorities of the funding agency or organization so that the proposed research matches the funding priorities and what the agency wants to fund. Knowing this can help align the mission and goals of the investigator with those of the funding agency. While each funding agency will require unique and different sections to the proposal, there are some commonly requested elements that may include a brief abstract, specific aims or objectives, introduction, brief background information, a research plan or research strategy, a statement of significance, a statement describing the innovative qualities of the proposed research, broader impacts of the research, intellectual impact, a statement of the expected results or alternatively, potential pitfalls to the proposed approach and alternative strategies in the event that your plans do not work. Additionally, a timeline of the experiments with specific benchmarks can be included to clearly outline how the work will be accomplished during the funding period. In some cases, a brief summary or conclusion with future directions can be included to indicate where the work is headed in the long-term and to provide broader context for the specific work that is proposed. With every grant proposal, letters of support and other documents such as biosketches, budget, budget justification, may be required for submission, and it is important to allow enough time to prepare these accurately and carefully. Making time to share your proposal with peers or mentors before submission provides an opportunity to receive critical feedback. Pre-review will allow editing and revision of the proposal so that it can be understood by the target audience, the reviewers.

Grant proposal writing can be a daunting task for anyone, including students. Time-management can be especially challenging if one is trying to balance the demands of taking academic courses, working as a teaching assistant, tutoring, and other demands on a graduate student’s schedule with the expectations and deadlines of the new and unfamiliar experience of writing a grant proposal at the same time. One way for colleges to address this challenge and support their graduate students is to provide a course-based mentored cohort or a proposal writing course. A class conducted within a college term or semester with a syllabus and a schedule to outline deadlines for assignments that are individual components of the final proposal. Students are able to manage their time, make forward progress, stay on track, and complete the proposal in a timely manner.

Topics included in this overview are: understanding your funding needs, identifying appropriate grant opportunities, analyzing the guidelines for the proposal, planning and time management, understanding the priorities of the funding agency or organization, proposal organization and writing strategies, additional forms and letters of support that may be required, the editing and revising process, and submission of your grant proposal.

MAJOR TOPIC: (Guidelines for student grant writers)

The guidelines presented here are divided into nine key topics that serve as best practices for successful grant writing for student research projects.

Subtopic: (Understanding funding needs)

Financial support for graduate student research may address unique needs based on the stage of the graduate student career. Grants can provide funding to support research expenses and supplies or services that are needed to complete the dissertation research, such as those that might be provided by a core facility. A grant may also provide funds for travel to a conference where research results will be disseminated, and the graduate student can network with experts in the field. Grant funding can also provide stipend and funds for tuition and fees, thus allowing fulltime dedication to the research. Some grants are designed to support late-stage graduate students as they are writing up their research results for publication and finalizing their dissertation.

Subtopic: (Identifying appropriate grant opportunities)

Identifying appropriate grant opportunities can be challenging, especially if this is a new endeavor for a student. It is essential to check the eligibility requirements before starting so as not to waste time and energy. To find the best opportunities, talking to individuals with experience is a good practice. Faculty advisors and other students who have been successful with grant proposals can provide valuable advice. University Offices of Research or Graduate Colleges often have resources available for graduate students and can provide information on which internal and external funding opportunities may be best suited for a graduate student in a specific field of study. Eligibility may also be dependent upon national citizenship or underrepresented minority status. Information on extensive databases that include national and international funding opportunities are available through Offices of Research or Sponsored Programs at universities. Grants.gov , National Science Foundation (NSF), and National Institutes of Health (NIH) are a few of the places one can find information about available federal research funding. Table 1 provides examples of graduate student grant opportunities including the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) Individual Predoctoral Fellowship (F31) from NIH, which is to enable promising predoctoral students to obtain mentored research training while conducting dissertation research in a health-related field relevant to the missions of the NIH, the Graduate Research Fellowship Program (GRFP) from NSF, which supports outstanding graduate students in NSF-supported STEM disciplines who are pursuing research-based master’s and doctoral degrees at accredited U.S. institutions, and the Grant-In-Aid-of-Research (GIAR) from Sigma Xi, a scientific research honor society, which supports undergraduate and graduate students to carryout mentored research in most areas of science and engineering. The NIH NRSA F31 is available to U.S. citizens or permanent residents who are enrolled in a research doctoral degree program. The NSF GRFP is available to U.S. citizens, U.S. national, or permanent residents who are at an early stage in their graduate career and have completed no more than one academic year of full-time graduate study.

Examples of Graduate Student Grant Opportunities

Subtopic: (Analyzing the guidelines for the proposal)

Gathering all information about specific grant funding opportunities and organizing into a spreadsheet is a good practice. Including essential information such as name of grant or fellowship program, the web address, the eligibility requirements, deadlines, requirements for letters of support, requirements of the written application, relevant forms, award amount, name and address of point of contact at the funding agency. Review and analyze the guidelines for the proposal thoroughly and carefully. Outline the proposal exactly as the guidelines indicate. Do not omit any requirements and do not rearrange sections. Analyze the instructions and organize the proposal accordingly. Be aware of page limits, margin and font size requirements, and line spacing restrictions.

Subtopic: (Understanding the priorities of the funding agency)

Most funding agencies and organizations provide publicly available information about their mission and funding priorities. It is important to understand the mission and goals of the funding agency, and how to address the mission and goals in the written proposal. Grant writers should be informed about who the proposal is written to. Know the audience and focus the writing on the needs of the funding agency. Write the proposal to demonstrate that the proposed work will solve the problem or serve a need.

Subtopic: (Time management and planning)

Time management is critical for a successful grant. You will need to plan for the following activities in your schedule;

- Read the existing literature to research the topic thoroughly

- Carry out a comprehensive, critical review of the current literature

- Dedicate three months to development and submission of proposal (this will help with balancing other obligations)

- Create a timeline and set weekly goals for the proposal writing process (set realistic writing and review schedules)

- Protect time on the calendar (1–2 hours per day) to allow a focused approach to writing each day

- Request letters of support one month before the deadline, provide a draft of the support letter so essential details are included

- Ask for colleagues to read prior to submission

- Allow for time to revise

Stick to your schedule and don’t get behind. This will reduce stress on both you and anyone you recruit to support you. This is also where the structure of a proposal writing class is very beneficial for both the student and for the faculty researcher.

Subtopic: (Proposal organization and writing strategies)

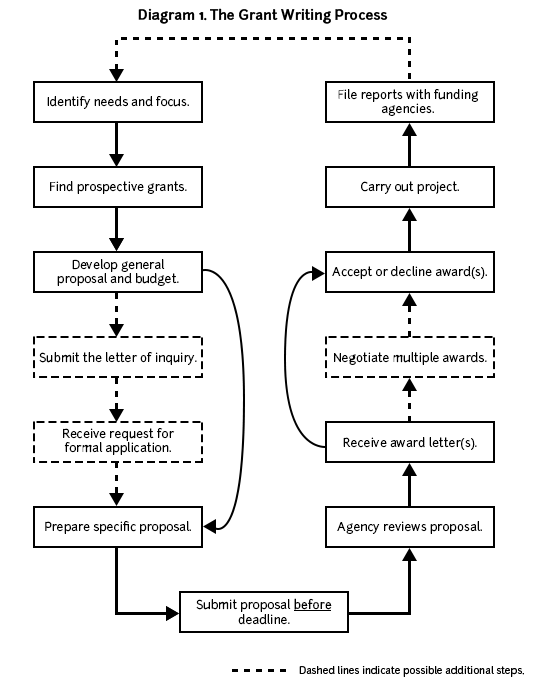

Writing strategies should incorporate a logical flow of information that is logical and easy to follow. It is important to understand what sections or components need to be included in the grant proposal as well as what purpose each section serves in the proposal. A general example of the order in which elements should be presented in a research narrative is shown in Figure 1 . However, each type of grant proposal and funding agency has unique and slightly different requirements. For example, the NIH F31 NRSA requires specific sections in a specific order that serve specific purposes in the proposal. The sections are as follows: Project summary, Project Narrative, Bibliography and references cited, Facilities and other resources, Equipment, Applicant’s background and goals, Research training plan, Specific aims, and Research strategy. Additional documents that are required for the NIH F31 include descriptions of the Respective contributions, Selection of sponsor and institution, Training in the responsible conduct of research, Sponsor and co-sponsor statements, Letters of support, Description of institutional environment and commitment to training, Budget section, and Vertebrate animals and Human subjects, if applicable. The NIH F31 begins with a Project summary, which is limited to 30 lines of text and includes a description of the key focus of the proposed research, the long-term goals, the relevance of the work to NIH’s mission, a brief description of the research design and methodology. The Project summary should be written in 3 rd person and should not describe past accomplishments. The Project narrative is approximately three sentences in length that should describe the relevance of the work to public health. The Project narrative should answer the question, ‘What will your research contribute to the field?” The Bibliography should include all references that are included in the Research strategy section. The Facilities and other resources section should describe how the research site will contribute to the probability for the successful completion of the proposed work. This section may include a description of institutional support provided for the project, a description of the physical resources available, and the intellectual environment and rapport with other investigators. The Equipment list should include major instruments that are available for the project, where they are and what the instruments can do for the project.

Order of information presented in the research narrative, also referred to as the Research strategy, Research Approach, or Proposed investigation, depending upon specific funding agency.

The Applicant’s background and goals section, should be organized to include the following subheadings: A. Doctoral dissertation and research experience, B. Training goals and objectives, C. Activities planned under this award, D. Research training plan. The Research Training plan should relate the research to your career goals, it should explain the relationship between the applicant’s research and the mentor’s ongoing research. Additionally, the plan should be tailored to the applicant’s experiences and career skills and goals. The Specific Aims page (a 1-page maximum) should identify the need or gap for the research, it should state the long-term goals, the hypothesis, and the specific aims that will be used to test the hypothesis or research question. The specific aims page should also include a statement of the expected outcomes and the impact of the results of the proposed work. The Research strategy section (6 pages maximum) is a narrative of the research that will be carried out. It should describe the significance of the work and the experimental approach that will be taken to accomplish the goals. Potential pitfalls or potential limitations should be acknowledged within the Research strategy, and alternative approaches may be included in the event that the original experimental plans are not feasible. A time line with benchmarks may be provided to demonstrate feasibility of the overall plan within the timeframe of the award.

The NSF GRFP is a shorter proposal and is comprised of the following sections: Personal information, Education, work and other experience, Transcripts, Proposed field of study, The Proposed graduate study and graduate school, the names and emails of at least three reference letter writers, the Personal, relevant background and future goals statement, which is limited to 3 pages in length, and the Graduate research plan statement, which is limited to 2 pages in length. The overall goal of the program is to support fellows who will become knowledge experts who will contribute significantly to research, teaching, and innovations in science and engineering. Both the Personal, relevant background and future goals statement and the Graduate research plan statement must address NSF’s review criteria of Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts. Each must be addressed individually under separate headings in both the Personal and Research Plan statements. The purpose of this requirement is to provide the reviewers with the information that is necessary to evaluate the applications. Reviewers will evaluate the applications based on what the applicant wants to do, why they want to do it, how they plan to do it, how they will know if they succeed, and what benefits may be realized if the research is successful. The Intellectual Merit statements should encompass the potential to advance knowledge and understanding within the field or across different fields, and the Broader Impacts statement should address the potential to benefit society and contribute to the achievement of specific desired societal outcomes. The Intellectual Merit statements and the Broader Impacts statement should clearly explain to what extent the proposed activities suggest and explore creative, original, and transformative concepts. Reviewers of NSF GRFP applications will evaluate how well-reasoned and how well organized the plan for carrying out the proposed research is, and the extent to which it is based on sound rationale. Additionally, reviewers will evaluate the qualifications of the applicant and the resources that are available to the applicant to carry out the proposed research, so it is critical that grant writers communicate clearly and address all required elements using a comprehensive approach, giving a balanced consideration to all components of the application including educational and research record, leadership, outreach, service, future plans, and individual competencies.

The Sigma Xi GIAR is an even shorter proposal, limited to 500 words in length. GIAR may be used to support scientific research in any field. Within the 500-word limit, applicants must include the following sections: Background information, Goals, Hypothesis/research question, Specific objectives, Methods, and Significance of the research. Additional documents include a Budget and Budget justification. The Background information must be brief and be written in a concise manner. The statement of goals must also be concise, and limited to one or two sentences. The hypothesis or research question should be one sentence followed immediately by the Specific objectives/aims, which can be listed as a bulleted list. Methods should be briefly described under each of the specific aims. The statement of significance of the research should describe how the study contributes to the big picture of research in this field of study. If the proposed work is part of an ongoing project, clearly state how the project is integrated into the ongoing project yet represents a unique contribution to the field. The Budget is limited to items that are not routinely found in standard research laboratories and to reagents that are clearly project-specific. In the case of items for which applicants wish to provide justification, the Budget justification must demonstrate how the item relates to the methodology described in the Proposed investigation section. Applicants should include justification for expenses that may not normally receive funding. Three key elements are evaluated including the proposed investigations, the budget, and the recommendations from the research advisor.

While each type of grant proposal and funding agency has unique and slightly different requirements, there are common features and strategies that are generally applicable for most grant proposals. It is best to link one component to another in order to create a linear progression of logic, using a conceptual framework that allows readers to link details to the framework as they read. Summarize the current state of knowledge in the field. Identify a specific gap in knowledge or previously published work and explain why there is a critical need to address the problem and the necessity or rationale to solve the problem. State a central hypothesis. Clearly and concisely explain how the proposed research will fill the gap and solve the problem. Provide specific information about methods, materials, and any preliminary data that addresses the problem or gap. Try to come up with overall objectives/goals that are specific for the proposal. Then, work on the specific aims, which are those that are needed to pursue in order to attain the overall objectives/goals. The objectives/goals can be categorized as short-term (can be accomplished in one to three years) or long term (expected to be completed by the end of the grant). Provide a brief statement of the short-term impacts, benefits, or results that are anticipated from the proposed work. Add future research directions upon achieving the short-term goals/objectives. Provide a statement of broader impacts and benefits that are anticipated upon successful completion of the proposed work. Last but not least, explain how the work will result in a benefit to the larger research community or state who will most likely benefit from the new knowledge generated as a result of the proposed research.

Include a sentence of each following item’s in your proposal;

- A statement of critical need that your proposal will address early in the introductory paragraph

- A statement of long-term goal that describes the goals for the next ten years in the field as a whole

- Create a statement of overall objectives that are specific for the proposal; objectives that can be accomplished in one to three years and that you expect to complete by the end of the grant

- State the central hypothesis and the rationale for the project

Be sure your proposal answers the following questions;

- To attain the overall objectives, what specific aims will be pursued?

- At the completion of the proposed research what is the expected outcome?

- What positive impact do you expect to have?

- What is the significance of the proposed work?

- Finally, what is innovative about the proposal and the approach taken, and how will this contribute to the field of study?

Create a bulleted outline of your proposal that includes each of the components of the proposal. Refine as necessary. Seek constructive criticism of the bulleted outline from peers and mentors. Continue to work on the bulleted outline until each component meets its purpose, each is linked to the others and the progression of logic is linear. Format your proposal according to the guidelines. Expand the bulleted sections into complete sentences in such a way that reviewers will know why the information has been included. Edit and refine until it reads well and fits into the page or word limit.

Integrate your review of relevant literature into your proposal in the introduction or background section. Cite primary literature, not reviews. Use the most current references. If you include figures in the introduction section or as preliminary data, make sure that they are large enough to read (no smaller than 9 point) and that they will be understood if the document is converted to black and white. Use a succinct writing style and include only essential, meaningful detail. List the results that you expect from each proposed experiment. Identify potential problems and alternative strategies if problems were to arise. Create a timeline and benchmarks. Conclude with a future directions statement.

Subtopic: (Additional forms and letters of support)

Additional documents may be required as components of the proposal. These may include budget, budget justification, college transcript, description of research facilities available for the project, and letters of support. Start on these other components early. Request letters of support one month before the deadline, letting letter writers know of the deadline and provide a draft of the support letter so that the essential details are included. Share a draft of your proposal with them. Develop a title for your proposal and share it with your letter writers. The title should emphasize the payoff from the proposed research. Use your overall objective and the significance to inform your title. Make several candidates for your title. Ask colleagues to select the most informative, interesting title.

Budget development will follow the specific guidelines for the grant proposal and specific funding agency. It is important to know what the allowable costs are and what costs are not allowable on the grant. For most grant proposals, it is important to include a budget justification, which serves as a narrative that explains each component of the budget in terms of the proposed research. When writing a budget justification, the focus should be on how each component of the budget is required to meet the goals of the project and how each projected cost was calculated. For NIH F31 and NSF GFRP applications, where funds are made available for specific purposes only such as predoctoral stipend, institutional allowance, and tuition and fees, a detailed justification may not be required. Sigma Xi GIAR in contrast, allows the applicant to request funding for purchases of specific equipment necessary to undertake the proposed research project, travel to and from a research site, supplies that are specific to the project and that are not generally available in a research laboratory, and reimbursements for human subjects research in the case of psychological research. For Sigma Xi, a budget justification would be included to justify how the items in the budget are related to the methodology described in the proposed investigation section. For other grant proposals in which the funding agency guidelines list categories or criteria for allowable expenses in the budget, the budget justification may include the following main categories: Personnel (senior personnel, other personnel, other significant contributors), Consultants, Fringe benefits, Travel, Participant/trainee support, Other direct costs, and Facilities and administration costs.

In cases in which a budget justification is required, organize the budget justification to follow the same order as the budget. Include details to explain the costs included in the budget. Only include items that are allowable, reasonable, and allocable. Use subheadings to organize your budget justification to make it easy for reviewers to read. The writing style for the budget justification should be concise but complete, and all numbers presented in the budget justification should match those presented in the budget.

Subtopic: (Editing and revising)

Draft the proposal. Let it sit for a few days before returning to work on it. Read again and revise for clarity and conciseness. Edit any superfluous language that does not add to the proposal. Plan for a pre-submission review. Ask others to read the proposal, including faculty advisors, committee members, and graduate students who have had previous success with the specific funding agency. Plan to revise multiple times until all ambiguities are clarified, and logic is flawless. Make sure that the grant makes sense to others.

Subtopic: (Submission of your grant proposal)

Students should be aware of policies and procedures for submitting grant proposals through their university. It is important to know if the application will be submitted by the university or alternatively, directly by the student. It is important to know this well ahead of the deadline, as Offices of Sponsored Programs may have requirements for proposals to be submitted to them prior to the actual agency or organization deadline. Become familiar with the online submission system. Submitting early is always a good practice, as it provides the opportunity to catch potential errors that will be identified upon submission and correct them before the deadline.

CONCLUSION:

Key guidelines for proposal development can be summarized by the following points:

- Understand the mission and goals of the funding agency, and how the mission and goals will influence the focus of your proposal.

- Become familiar with the online submission system. Read all instructions for your application. Understand the formatting requirements for your proposal (font size, type line density, margin widths, lengths, etc.).

- Carry out a comprehensive, critical review of the current literature.

- Develop a one -three sentence statement describing your proposal idea. Share your ideas and seek constructive criticism of the idea with your colleagues. Refine your idea based on their input.

- Use a writing style that makes people want to read your proposal. Understand how to link one component to another in order to create a linear progression of logic. Use a succinct writing style and include only essential, meaningful detail.

- Protect your time on your calendar to write your grant proposal. Maximize the amount of quality time that you have for writing – balance your other obligations with your writing efforts. Identify the time of day when you have one to two hours of quality time working on your proposal every day. Protect that time in your calendar. Set realistic writing and review schedules. Stick to your schedule. Don’t allow yourself to get behind.

- Start your proposal with a section to provide a conceptual framework that allows readers to hang details on the framework as they read.

- Understand the structure and purpose of each section. Create a statement of critical need that your proposal will address. Create a statement of long-term goal. Create a statement of overall objectives of the proposal. State the central hypothesis. State the rationale for the project. To attain the overall objectives, what specific aims will be pursued? At the completion of the proposed research what is the expected outcome. What positive impact do you expect to have? What is the significance of the proposed work?

- Create a bulleted outline of your proposal that includes each of the components of the proposal. Refine as necessary. Seek constructive criticism of the bulleted outline. Continue to work on the bulleted outline until each component meets its purpose, each is linked to the others and the progression of logic is linear.

- Format your proposal according to guidelines. Expand the bulleted sections into complete sentences in such a way that reviewers will know why the information has been included.

- Edit and refine until it reads well and fits into the page or word limit.

- Know how to integrate your review of relevant literature into your proposal. Cite primary literature, not reviews. Use the most current references.

- If you include figures, make sure that they are large enough to read (no smaller than 9 point) and that they will be understood if the document is converted to black and white.

- List the results that you expect from each experiment, integrate them into a narrative.

- Identify potential problems and alternative strategies if problems were to arise.

- Create a timeline and benchmarks.

- Conclude with a future directions statement.

- Notify your letter writers of your deadline – share a draft with them.

- Budget development—know allowable costs and what costs are not allowable on the grant. Include a budget justification.

- Develop a title for your proposal that emphasizes the payoff from the proposed research. Use your overall objective and the significance to inform your title. Make several candidates for your title. Ask colleagues to select the most informative, interesting title.

- Plan for a pre-submission review.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

We acknowledge support from the Institutional Development Awards (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Grant P20GM109095. We also acknowledge support from The Biomolecular Research Center at Boise State, BSU-Biomolecular Research Center, RRID:SCR_019174.

Contributor Information

Diane Smith, Biomolecular Research Center, 1910 University Drive, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho, 83725.

Abu Sayeed Chowdhury, Biomolecular Sciences Graduate Programs, 1910 University Drive, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho, 83725.

Julia Thom Oxford, Biomolecular Research Center, 1910 University Drive, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho, 83725.

LITERATURE CITED:

- Find. apply. succeed . (2022, June 10). GRANTS.GOV . https://www.grants.gov/

- Grants in aid of research. (2022, June 10). Sigma Xi . https://www.sigmaxi.org/programs/grants-in-aid-of-research

- National Science Foundation - Where Discoveries Begin . (2022, June 10). NSF. https://www.nsf.gov/ [ Google Scholar ]

- NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program (GRFP). Beta site for NSF - National Science Foundation . (2022, June 10). Beta site for NSF - National Science Foundation. https://beta.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/nsf-graduate-research-fellowship-program-grfp [ Google Scholar ]

- Sigma xi news. (2022, June 10). Home . https://www.sigmaxi.org/home

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022, Jun 10). National Institutes of Health . https://www.nih.gov/

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022, Jun 10). Jointly sponsored Ruth L. Kirschstein national research service award individual national research service award (F31) . National Institutes of Health. https://researchtraining.nih.gov/programs/fellowships/F31 [ Google Scholar ]

Grant Proposals (or Give me the money!)

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you write and revise grant proposals for research funding in all academic disciplines (sciences, social sciences, humanities, and the arts). It’s targeted primarily to graduate students and faculty, although it will also be helpful to undergraduate students who are seeking funding for research (e.g. for a senior thesis).

The grant writing process