What is a dissertation abstract and how do I write one for my PhD?

Feb 12, 2019

There are a lot of posts that talk about how to write an abstract. Most say that you should write your abstract to impress your examiner.

We say that you need to flip things upside down: sure, your examiner will read it and want to see that you’ve written it well, but you should actually have your next boss in mind when you write it.

When you apply for your first academic job, the abstract may be the only part of your thesis that your new boss will read. They may not have the time or energy to read the whole thesis, so the abstract plays a crucial role. You should write it as if you academic career depends on it.

In this guide we talk about how to write an outstanding abstract that will (hopefully) land you a job.

If you haven’t already, make sure you download our PhD Writing Template , which you can use in conjunction with this guide to supercharge your PhD.

What is an abstract?

This is fairly straightforward stuff, but let us be clear so we are all on the same page.

An abstract is a short summary at the beginning of the PhD that sums up the research, summarises the separate sections of the thesis and outlines the contribution.

It is typically used by those wishing to get a broad understanding of a piece of research prior to reading the entire thesis.

When you apply for your first academic job, the hiring manager will take a look through applicants’ abstracts (as well as your CV and covering letter) to create a shortlist. If you are lucky enough to do well at an interview, your potential new boss will take another look through it before deciding whether to offer you the job.

Why don’t they read the whole thing? Apart from the fact that they’re way too busy to read 200+ pages, a well written abstract actually contains all they need to know. It is a way of letting them see what your research is about, what contribution it makes, what your understanding of the field is and how or whether you will fit into the department.

So, you need to write it well.

But, don’t underestimate how hard it is to write a PhD thesis abstract. You have to condense hundred of pages and years of work into a few hundred words (exactly how many will depend on your university, so double check with them before you start writing).

How do I write a good PhD abstract?

Some blog posts use keywords to summarise the content (this one does, scroll down to see them). The abstract is similar. It’s an extended set of keywords to summarise a complex piece of research.

Above all, your PhD abstract should answer the question: ‘so what’ ? In other words, what is the contribution of your thesis to the field?

If you’ve been using our PhD writing template you’ll know that, to do this, your abstract should address six questions:

- What is the reason for writing the thesis?

- What are the current approaches and gaps in the literature?

- What are your research question(s) and aims?

- Which methodology have you used?

- What are the main findings?

- What are the main conclusions and implications?

One thing that should be obvious is that you can’t write your abstract until the study itself has been written. It’ll typically be the last thing you write (alongside the acknowledgements).

But how can I write a great one?

The tricky thing about writing a great PhD abstract is that you haven’t got much space to answer the six questions above. There are a few things to consider though that will help to elevate your writing and make your abstract as efficient as possible:

- Give a good first impression by writing in short clear sentences

- Don’t repeat the title in the abstract

- Don’t cite references

- Use keywords from the document

- Respect the word limit

- Don’t be vague – the abstract should be a self contained summary of the research, so don’t introduce ambiguous words or complex terms

- Focus on just four or five essential points, concepts, or findings. Don’t, for example, try to explain your entire theoretical framework

- Edit it carefully. Make sure every word is relevant (you haven’t got room for wasted words) and that each sentence has maximum impact

- Avoid lengthy background information

- Don’t mention anything that isn’t discussed in the thesis

- Avoid overstatements

- Don’t spin your findings, contribution or significance to make your research sound grander or more influential that it actually is

Examples of a good and bad abstract

We can see that the bad abstract fails to answer the six questions posed above. It reads more like a PhD proposal, rather than a summary of a piece of research.

Specifically:

- It doesn’t discuss the reason why the thesis was written

- It doesn’t outline the gaps in the literature

- It doesn’t outline the research questions or aims

- It doesn’t discuss the methods

- It doesn’t discuss the findings

- It doesn’t discuss the conclusions and implications of the research.

It is also too short, lacks adequate keywords and introduces unnecessary detail. The abbreviations and references only serve to confuse the reader and the claim that the thesis will ‘develop a new theory of climate change’ is both vague and over-ambitious. The reader will see through this.

The good abstract though does a much better job at answering the six questions and summarising the research.

- The reason why the thesis was written is stated: ‘We do so to better enable policy makers and academics to understand the nuances of multi-level climate governance’ and….’it informs our theoretical understanding of climate governance by introducing a focus on local government hitherto lacking, and informs our empirical understanding of housing and recycling policy.’

- The gap is clearly defined: ‘The theory has neglected to account for the role of local governments.’

- The research question are laid out: ‘We ask to what extent and in what ways local governments in the UK’…

- The methods are hinted at: ‘Using a case study…’

- The findings are summarised: ‘We show that local governments are both implementers and interpreters of policy. We also show that they make innovative contributions to and influence the direction of national policy.’

- The conclusions and implications are clear: ‘The significance of this study is that it informs our theoretical understanding of climate governance by introducing a focus on local government hitherto lacking, and informs our empirical understanding of housing and recycling policy.’

This abstract is of a much better length, and it fully summarises what the thesis is about. We can see that if someone (i.e. your hiring manager) were to read just this abstract, they’d understand what your thesis is about and the contribution that it makes.

Your PhD thesis. All on one page.

Use our free PhD structure template to quickly visualise every element of your thesis.

I can’t summarise my thesis, what do I do?

We suggest you fill out our PhD Writing Template . We’ve designed it so that you can visualise your PhD on one page and easily see the main components. It’s really easy to use. It asks you a few questions related to each section of your thesis. As you answer them, you develop a synopsis. You can use that synopsis to inform your abstract. If you haven’t downloaded it, you can find it here.

Like everything related to writing, it takes practice before you get great at writing abstracts. Follow our tips and you’ll have a head start over others.

Remember, you’re not writing your abstract for anyone other than your hiring manager. Make sure it showcases the best of your research and shows your skills as both a researcher and a writer.

If you’re struggling, send us your abstract by email and we’ll have give you free advice on how to improve it.

Hello, Doctor…

Sounds good, doesn’t it? Be able to call yourself Doctor sooner with our five-star rated How to Write A PhD email-course. Learn everything your supervisor should have taught you about planning and completing a PhD.

Now half price. Join hundreds of other students and become a better thesis writer, or your money back.

Share this:

Hello! I am a first year PhD student and I am interested in your Thesis writing course. However, I don’t have Paypal, thus I would like to know if there is an alternative way for you to get paid. I hope so, because I have been “following” you and I think the course can be really useful for me 🙂 Hope to hear from you soon. Best wishes, Belén Merelas

Thanks for the comment – I have sent you an email.

Hello! I am a Master’s student and I have applied for a PhD position. The professors have asked me to write a short abstract-like text, based on a brief sentence they will send me, related to the project study. How am I supposed to write a text like that when I don’t have the whole paper, the methods, results etc? Thank you in advance!

Hi Maria. I’m afraid that without knowing more about your topic or subject I am unable to give you advice on this. Sorry I can’t help in the way you may have hoped.

Thank u so much… your tips have really helped me to broaden my scope on the idea of how to write an abstract for my Ph.D. course. This is so thoughtful of you… The article is very informative and helpful…Thanks again!

I’m so pleased. Thanks for your lovely words. They’re music to my ears.

Very insightful Thanks

Glad you think so. Good luck with the writing.

Thank you so much Doc

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Search The PhD Knowledge Base

Most popular articles from the phd knowlege base.

The PhD Knowledge Base Categories

- Your PhD and Covid

- Mastering your theory and literature review chapters

- How to structure and write every chapter of the PhD

- How to stay motivated and productive

- Techniques to improve your writing and fluency

- Advice on maintaining good mental health

- Resources designed for non-native English speakers

- PhD Writing Template

- Explore our back-catalogue of motivational advice

The Dissertation Abstract: 101

How to write a clear & concise abstract (with examples).

By: Madeline Fink (MSc) Reviewed By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | June 2020

So, you’ve (finally) finished your thesis or dissertation or thesis. Now it’s time to write up your abstract (sometimes also called the executive summary). If you’re here, chances are you’re not quite sure what you need to cover in this section, or how to go about writing it. Fear not – we’ll explain it all in plain language , step by step , with clear examples .

Overview: The Dissertation/Thesis Abstract

- What exactly is a dissertation (or thesis) abstract

- What’s the purpose and function of the abstract

- Why is the abstract so important

- How to write a high-quality dissertation abstract

- Example/sample of a quality abstract

- Quick tips to write a high-quality dissertation abstract

What is an abstract?

Simply put, the abstract in a dissertation or thesis is a short (but well structured) summary that outlines the most important points of your research (i.e. the key takeaways). The abstract is usually 1 paragraph or about 300-500 words long (about one page), but but this can vary between universities.

A quick note regarding terminology – strictly speaking, an abstract and an executive summary are two different things when it comes to academic publications. Typically, an abstract only states what the research will be about, but doesn’t explore the findings – whereas an executive summary covers both . However, in the context of a dissertation or thesis, the abstract usually covers both, providing a summary of the full project.

In terms of content, a good dissertation abstract usually covers the following points:

- The purpose of the research (what’s it about and why’s that important)

- The methodology (how you carried out the research)

- The key research findings (what answers you found)

- The implications of these findings (what these answers mean)

We’ll explain each of these in more detail a little later in this post. Buckle up.

What’s the purpose of the abstract?

A dissertation abstract has two main functions:

The first purpose is to inform potential readers of the main idea of your research without them having to read your entire piece of work. Specifically, it needs to communicate what your research is about (what were you trying to find out) and what your findings were . When readers are deciding whether to read your dissertation or thesis, the abstract is the first part they’ll consider.

The second purpose of the abstract is to inform search engines and dissertation databases as they index your dissertation or thesis. The keywords and phrases in your abstract (as well as your keyword list) will often be used by these search engines to categorize your work and make it accessible to users.

Simply put, your abstract is your shopfront display window – it’s what passers-by (both human and digital) will look at before deciding to step inside.

Why’s it so important?

The short answer – because most people don’t have time to read your full dissertation or thesis! Time is money, after all…

If you think back to when you undertook your literature review , you’ll quickly realise just how important abstracts are! Researchers reviewing the literature on any given topic face a mountain of reading, so they need to optimise their approach. A good dissertation abstract gives the reader a “TLDR” version of your work – it helps them decide whether to continue to read it in its entirety. So, your abstract, as your shopfront display window, needs to “sell” your research to time-poor readers.

You might be thinking, “but I don’t plan to publish my dissertation”. Even so, you still need to provide an impactful abstract for your markers. Your ability to concisely summarise your work is one of the things they’re assessing, so it’s vital to invest time and effort into crafting an enticing shop window.

A good abstract also has an added purpose for grad students . As a freshly minted graduate, your dissertation or thesis is often your most significant professional accomplishment and highlights where your unique expertise lies. Potential employers who want to know about this expertise are likely to only read the abstract (as opposed to reading your entire document) – so it needs to be good!

Think about it this way – if your thesis or dissertation were a book, then the abstract would be the blurb on the back cover. For better or worse, readers will absolutely judge your book by its cover .

How to write your abstract

As we touched on earlier, your abstract should cover four important aspects of your research: the purpose , methodology , findings , and implications . Therefore, the structure of your dissertation or thesis abstract needs to reflect these four essentials, in the same order. Let’s take a closer look at each of them, step by step:

Step 1: Describe the purpose and value of your research

Here you need to concisely explain the purpose and value of your research. In other words, you need to explain what your research set out to discover and why that’s important. When stating the purpose of research, you need to clearly discuss the following:

- What were your research aims and research questions ?

- Why were these aims and questions important?

It’s essential to make this section extremely clear, concise and convincing . As the opening section, this is where you’ll “hook” your reader (marker) in and get them interested in your project. If you don’t put in the effort here, you’ll likely lose their interest.

Step 2: Briefly outline your study’s methodology

In this part of your abstract, you need to very briefly explain how you went about answering your research questions . In other words, what research design and methodology you adopted in your research. Some important questions to address here include:

- Did you take a qualitative or quantitative approach ?

- Who/what did your sample consist of?

- How did you collect your data?

- How did you analyse your data?

Simply put, this section needs to address the “ how ” of your research. It doesn’t need to be lengthy (this is just a summary, after all), but it should clearly address the four questions above.

Need a helping hand?

Step 3: Present your key findings

Next, you need to briefly highlight the key findings . Your research likely produced a wealth of data and findings, so there may be a temptation to ramble here. However, this section is just about the key findings – in other words, the answers to the original questions that you set out to address.

Again, brevity and clarity are important here. You need to concisely present the most important findings for your reader.

Step 4: Describe the implications of your research

Have you ever found yourself reading through a large report, struggling to figure out what all the findings mean in terms of the bigger picture? Well, that’s the purpose of the implications section – to highlight the “so what?” of your research.

In this part of your abstract, you should address the following questions:

- What is the impact of your research findings on the industry /field investigated? In other words, what’s the impact on the “real world”.

- What is the impact of your findings on the existing body of knowledge ? For example, do they support the existing research?

- What might your findings mean for future research conducted on your topic?

If you include these four essential ingredients in your dissertation abstract, you’ll be on headed in a good direction.

Example: Dissertation/thesis abstract

Here is an example of an abstract from a master’s thesis, with the purpose , methods , findings , and implications colour coded.

The U.S. citizenship application process is a legal and symbolic journey shaped by many cultural processes. This research project aims to bring to light the experiences of immigrants and citizenship applicants living in Dallas, Texas, to promote a better understanding of Dallas’ increasingly diverse population. Additionally, the purpose of this project is to provide insights to a specific client, the office of Dallas Welcoming Communities and Immigrant Affairs, about Dallas’ lawful permanent residents who are eligible for citizenship and their reasons for pursuing citizenship status . The data for this project was collected through observation at various citizenship workshops and community events, as well as through semi-structured interviews with 14 U.S. citizenship applicants . Reasons for applying for U.S. citizenship discussed in this project include a desire for membership in U.S. society, access to better educational and economic opportunities, improved ease of travel and the desire to vote. Barriers to the citizenship process discussed in this project include the amount of time one must dedicate to the application, lack of clear knowledge about the process and the financial cost of the application. Other themes include the effects of capital on applicant’s experience with the citizenship process, symbolic meanings of citizenship, transnationalism and ideas of deserving and undeserving surrounding the issues of residency and U.S. citizenship. These findings indicate the need for educational resources and mentorship for Dallas-area residents applying for U.S. citizenship, as well as a need for local government programs that foster a sense of community among citizenship applicants and their neighbours.

Practical tips for writing your abstract

When crafting the abstract for your dissertation or thesis, the most powerful technique you can use is to try and put yourself in the shoes of a potential reader. Assume the reader is not an expert in the field, but is interested in the research area. In other words, write for the intelligent layman, not for the seasoned topic expert.

Start by trying to answer the question “why should I read this dissertation?”

Remember the WWHS.

Make sure you include the what , why , how , and so what of your research in your abstract:

- What you studied (who and where are included in this part)

- Why the topic was important

- How you designed your study (i.e. your research methodology)

- So what were the big findings and implications of your research

Keep it simple.

Use terminology appropriate to your field of study, but don’t overload your abstract with big words and jargon that cloud the meaning and make your writing difficult to digest. A good abstract should appeal to all levels of potential readers and should be a (relatively) easy read. Remember, you need to write for the intelligent layman.

Be specific.

When writing your abstract, clearly outline your most important findings and insights and don’t worry about “giving away” too much about your research – there’s no need to withhold information. This is the one way your abstract is not like a blurb on the back of a book – the reader should be able to clearly understand the key takeaways of your thesis or dissertation after reading the abstract. Of course, if they then want more detail, they need to step into the restaurant and try out the menu.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

19 Comments

This was so very useful, thank you Caroline.

Much appreciated.

This information on Abstract for writing a Dissertation was very helpful to me!

This was so useful. Thank you very much.

This was really useful in writing the abstract for my dissertation. Thank you Caroline.

Very clear and helpful information. Thanks so much!

Fabulous information – succinct, simple information which made my life easier after the most stressful and rewarding 21 months of completing this Masters Degree.

Very clear, specific and to the point guidance. Thanks a lot. Keep helping people 🙂

This was very helpful

Thanks for this nice and helping document.

Nicely explained. Very simple to understand. Thank you!

Waw!!, this is a master piece to say the least.

Very helpful and enjoyable

Thank you for sharing the very important and usful information. Best Bahar

Very clear and more understandable way of writing. I am so interested in it. God bless you dearly!!!!

Really, I found the explanation given of great help. The way the information is presented is easy to follow and capture.

Wow! Thank you so much for opening my eyes. This was so helpful to me.

Thanks for this! Very concise and helpful for my ADHD brain.

I am so grateful for the tips. I am very optimistic in coming up with a winning abstract for my dessertation, thanks to you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![abstract of phd “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![abstract of phd “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![abstract of phd “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

Published on 1 March 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022 by Eoghan Ryan.

An abstract is a short summary of a longer work (such as a dissertation or research paper ). The abstract concisely reports the aims and outcomes of your research, so that readers know exactly what your paper is about.

Although the structure may vary slightly depending on your discipline, your abstract should describe the purpose of your work, the methods you’ve used, and the conclusions you’ve drawn.

One common way to structure your abstract is to use the IMRaD structure. This stands for:

- Introduction

Abstracts are usually around 100–300 words, but there’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check the relevant requirements.

In a dissertation or thesis , include the abstract on a separate page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Abstract example, when to write an abstract, step 1: introduction, step 2: methods, step 3: results, step 4: discussion, tips for writing an abstract, frequently asked questions about abstracts.

Hover over the different parts of the abstract to see how it is constructed.

This paper examines the role of silent movies as a mode of shared experience in the UK during the early twentieth century. At this time, high immigration rates resulted in a significant percentage of non-English-speaking citizens. These immigrants faced numerous economic and social obstacles, including exclusion from public entertainment and modes of discourse (newspapers, theater, radio).

Incorporating evidence from reviews, personal correspondence, and diaries, this study demonstrates that silent films were an affordable and inclusive source of entertainment. It argues for the accessible economic and representational nature of early cinema. These concerns are particularly evident in the low price of admission and in the democratic nature of the actors’ exaggerated gestures, which allowed the plots and action to be easily grasped by a diverse audience despite language barriers.

Keywords: silent movies, immigration, public discourse, entertainment, early cinema, language barriers.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

You will almost always have to include an abstract when:

- Completing a thesis or dissertation

- Submitting a research paper to an academic journal

- Writing a book proposal

- Applying for research grants

It’s easiest to write your abstract last, because it’s a summary of the work you’ve already done. Your abstract should:

- Be a self-contained text, not an excerpt from your paper

- Be fully understandable on its own

- Reflect the structure of your larger work

Start by clearly defining the purpose of your research. What practical or theoretical problem does the research respond to, or what research question did you aim to answer?

You can include some brief context on the social or academic relevance of your topic, but don’t go into detailed background information. If your abstract uses specialised terms that would be unfamiliar to the average academic reader or that have various different meanings, give a concise definition.

After identifying the problem, state the objective of your research. Use verbs like “investigate,” “test,” “analyse,” or “evaluate” to describe exactly what you set out to do.

This part of the abstract can be written in the present or past simple tense but should never refer to the future, as the research is already complete.

- This study will investigate the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

- This study investigates the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

Next, indicate the research methods that you used to answer your question. This part should be a straightforward description of what you did in one or two sentences. It is usually written in the past simple tense, as it refers to completed actions.

- Structured interviews will be conducted with 25 participants.

- Structured interviews were conducted with 25 participants.

Don’t evaluate validity or obstacles here — the goal is not to give an account of the methodology’s strengths and weaknesses, but to give the reader a quick insight into the overall approach and procedures you used.

Next, summarise the main research results . This part of the abstract can be in the present or past simple tense.

- Our analysis has shown a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis shows a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis showed a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

Depending on how long and complex your research is, you may not be able to include all results here. Try to highlight only the most important findings that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions.

Finally, you should discuss the main conclusions of your research : what is your answer to the problem or question? The reader should finish with a clear understanding of the central point that your research has proved or argued. Conclusions are usually written in the present simple tense.

- We concluded that coffee consumption increases productivity.

- We conclude that coffee consumption increases productivity.

If there are important limitations to your research (for example, related to your sample size or methods), you should mention them briefly in the abstract. This allows the reader to accurately assess the credibility and generalisability of your research.

If your aim was to solve a practical problem, your discussion might include recommendations for implementation. If relevant, you can briefly make suggestions for further research.

If your paper will be published, you might have to add a list of keywords at the end of the abstract. These keywords should reference the most important elements of the research to help potential readers find your paper during their own literature searches.

Be aware that some publication manuals, such as APA Style , have specific formatting requirements for these keywords.

It can be a real challenge to condense your whole work into just a couple of hundred words, but the abstract will be the first (and sometimes only) part that people read, so it’s important to get it right. These strategies can help you get started.

Read other abstracts

The best way to learn the conventions of writing an abstract in your discipline is to read other people’s. You probably already read lots of journal article abstracts while conducting your literature review —try using them as a framework for structure and style.

You can also find lots of dissertation abstract examples in thesis and dissertation databases .

Reverse outline

Not all abstracts will contain precisely the same elements. For longer works, you can write your abstract through a process of reverse outlining.

For each chapter or section, list keywords and draft one to two sentences that summarise the central point or argument. This will give you a framework of your abstract’s structure. Next, revise the sentences to make connections and show how the argument develops.

Write clearly and concisely

A good abstract is short but impactful, so make sure every word counts. Each sentence should clearly communicate one main point.

To keep your abstract or summary short and clear:

- Avoid passive sentences: Passive constructions are often unnecessarily long. You can easily make them shorter and clearer by using the active voice.

- Avoid long sentences: Substitute longer expressions for concise expressions or single words (e.g., “In order to” for “To”).

- Avoid obscure jargon: The abstract should be understandable to readers who are not familiar with your topic.

- Avoid repetition and filler words: Replace nouns with pronouns when possible and eliminate unnecessary words.

- Avoid detailed descriptions: An abstract is not expected to provide detailed definitions, background information, or discussions of other scholars’ work. Instead, include this information in the body of your thesis or paper.

If you’re struggling to edit down to the required length, you can get help from expert editors with Scribbr’s professional proofreading services .

Check your formatting

If you are writing a thesis or dissertation or submitting to a journal, there are often specific formatting requirements for the abstract—make sure to check the guidelines and format your work correctly. For APA research papers you can follow the APA abstract format .

Checklist: Abstract

The word count is within the required length, or a maximum of one page.

The abstract appears after the title page and acknowledgements and before the table of contents .

I have clearly stated my research problem and objectives.

I have briefly described my methodology .

I have summarized the most important results .

I have stated my main conclusions .

I have mentioned any important limitations and recommendations.

The abstract can be understood by someone without prior knowledge of the topic.

You've written a great abstract! Use the other checklists to continue improving your thesis or dissertation.

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarises the contents of your paper.

An abstract for a thesis or dissertation is usually around 150–300 words. There’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check your university’s requirements.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis or paper.

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

The abstract appears on its own page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/abstract/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction, thesis & dissertation acknowledgements | tips & examples, dissertation title page.

How to Write an Abstract for Your Thesis or Dissertation What is an Abstract? The abstract is an important component of your thesis. Presented at the beginning of the thesis, it is likely the first substantive description of your work read by an external examiner. You should view it as an opportunity to set accurate expectations. The abstract is a summary of the whole thesis. It presents all the major elements of your work in a highly condensed form. An abstract often functions, together with the thesis title, as a stand-alone text. Abstracts appear, absent the full text of the thesis, in bibliographic indexes such as PsycInfo. They may also be presented in announcements of the thesis examination. Most readers who encounter your abstract in a bibliographic database or receive an email announcing your research presentation will never retrieve the full text or attend the presentation. An abstract is not merely an introduction in the sense of a preface, preamble, or advance organizer that prepares the reader for the thesis. In addition to that function, it must be capable of substituting for the whole thesis when there is insufficient time and space for the full text. Size and Structure Currently, the maximum sizes for abstracts submitted to Canada's National Archive are 150 words (Masters thesis) and 350 words (Doctoral dissertation). To preserve visual coherence, you may wish to limit the abstract for your doctoral dissertation to one double-spaced page, about 280 words. The structure of the abstract should mirror the structure of the whole thesis, and should represent all its major elements. For example, if your thesis has five chapters (introduction, literature review, methodology, results, conclusion), there should be one or more sentences assigned to summarize each chapter. Clearly Specify Your Research Questions As in the thesis itself, your research questions are critical in ensuring that the abstract is coherent and logically structured. They form the skeleton to which other elements adhere. They should be presented near the beginning of the abstract. There is only room for one to three questions. If there are more than three major research questions in your thesis, you should consider restructuring them by reducing some to subsidiary status. Don't Forget the Results The most common error in abstracts is failure to present results. The primary function of your thesis (and by extension your abstract) is not to tell readers what you did, it is to tell them what you discovered. Other information, such as the account of your research methods, is needed mainly to back the claims you make about your results. Approximately the last half of the abstract should be dedicated to summarizing and interpreting your results. Updated 2008.09.11 © John C. Nesbit

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing for Publication: Abstracts

An abstract is "a brief, comprehensive summary of the contents of the paper" (American Psychological Association [APA], 2020, p. 38). This summary is intended to share the topic, argument, and conclusions of a research study or course paper, similar to the text on the back cover of a book. When submitting your work for publication, an abstract is often the first piece of your writing a reviewer will encounter. An abstract may not be required for course papers.

Read on for more tips on making a good first impression with a successful abstract.

An abstract is a single paragraph preceded by the heading " Abstract ," centered and in bold font. The abstract does not begin with an indented line. APA (2020) recommends that abstracts should generally be less than 250 words, though many journals have their own word limits; it is always a good idea to check journal-specific requirements before submitting. The Writing Center's APA templates are great resources for visual examples of abstracts.

Abstracts use the present tense to describe currently applicable results (e.g., "Results indicate...") and the past tense to describe research steps (e.g., "The survey measured..."), and they do not typically include citations.

Key terms are sometimes included at the end of the abstract and should be chosen by considering the words or phrases that a reader might use to search for your article.

An abstract should include information such as

- The problem or central argument of your article

- A brief exposition of research design, methods, and procedures.

- A brief summary of your findings

- A brief summary of the implications of the research on practice and theory

It is also appropriate, depending on the type of article you are writing, to include information such as:

- Participant number and type

- Study eligibility criteria

- Limitations of your study

- Implications of your study's conclusions or areas for additional research

Your abstract should avoid unnecessary wordiness and focus on quickly and concisely summarizing the major points of your work. An abstract is not an introduction; you are not trying to capture the reader's attention with timeliness or to orient the reader to the entire background of your study. When readers finish reading your abstract, they should have a strong sense of your article's purpose, approach, and conclusions. The Walden Office of Research and Doctoral Services has additional tutorial material on abstracts .

Clinical or Empirical Study Abstract Exemplar

In the following abstract, the article's problem is stated in red , the approach and design are in blue , and the results are in green .

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients have a high cardiovascular mortality rate. Precise estimates of the prevalence, risk factors and prognosis of different manifestations of cardiac disease are unavailable. In this study a prospective cohort of 433 ESRD patients was followed from the start of ESRD therapy for a mean of 41 months. Baseline clinical assessment and echocardiography were performed on all patients. The major outcome measure was death while on dialysis therapy. Clinical manifestations of cardiovascular disease were highly prevalent at the start of ESRD therapy: 14% had coronary artery disease, 19% angina pectoris, 31% cardiac failure, 7% dysrhythmia and 8% peripheral vascular disease. On echocardiography 15% had systolic dysfunction, 32% left ventricular dilatation and 74% left ventricular hypertrophy. The overall median survival time was 50 months. Age, diabetes mellitus, cardiac failure, peripheral vascular disease and systolic dysfunction independently predicted death in all time frames. Coronary artery disease was associated with a worse prognosis in patients with cardiac failure at baseline. High left ventricular cavity volume and mass index were independently associated with death after two years. The independent associations of the different echocardiographic abnormalities were: systolic dysfunction--older age and coronary artery disease; left ventricular dilatation--male gender, anemia, hypocalcemia and hyperphosphatemia; left ventricular hypertrophy--older age, female gender, wide arterial pulse pressure, low blood urea and hypoalbuminemia. We conclude that clinical and echocardiographic cardiovascular disease are already present in a very high proportion of patients starting ESRD therapy and are independent mortality factors.

Foley, R. N., Parfrey, P. S., Harnett, J. D., Kent, G. M., Martin, C. J., Murray, D. C., & Barre, P. E. (1995). Clinical and echocardiographic disease in patients starting end-stage renal disease therapy. Kidney International , 47 , 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1995.22

Literature Review Abstract Exemplar

In the following abstract, the purpose and scope of the literature review are in red , the specific span of topics is in blue , and the implications for further research are in green .

This paper provides a review of research into the relationships between psychological types, as measured by the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), and managerial attributes, behaviors and effectiveness. The literature review includes an examination of the psychometric properties of the MBTI and the contributions and limitations of research on psychological types. Next, key findings are discussed and used to advance propositions that relate psychological type to diverse topics such as risk tolerance, problem solving, information systems design, conflict management and leadership. We conclude with a research agenda that advocates: (a) the exploration of potential psychometric refinements of the MBTI, (b) more rigorous research designs, and (c) a broadening of the scope of managerial research into type.

Gardner, W. L., & Martinko, M. J. (1996). Using the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator to study managers: A literature review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 22 (1), 45–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639602200103

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Cover Letters

- Next Page: Formatting and Editing

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Manuscript Preparation

Know How to Structure Your PhD Thesis

- 4 minute read

- 34.7K views

Table of Contents

In your academic career, few projects are more important than your PhD thesis. Unfortunately, many university professors and advisors assume that their students know how to structure a PhD. Books have literally been written on the subject, but there’s no need to read a book in order to know about PhD thesis paper format and structure. With that said, however, it’s important to understand that your PhD thesis format requirement may not be the same as another student’s. The bottom line is that how to structure a PhD thesis often depends on your university and department guidelines.

But, let’s take a look at a general PhD thesis format. We’ll look at the main sections, and how to connect them to each other. We’ll also examine different hints and tips for each of the sections. As you read through this toolkit, compare it to published PhD theses in your area of study to see how a real-life example looks.

Main Sections of a PhD Thesis

In almost every PhD thesis or dissertation, there are standard sections. Of course, some of these may differ, depending on your university or department requirements, as well as your topic of study, but this will give you a good idea of the basic components of a PhD thesis format.

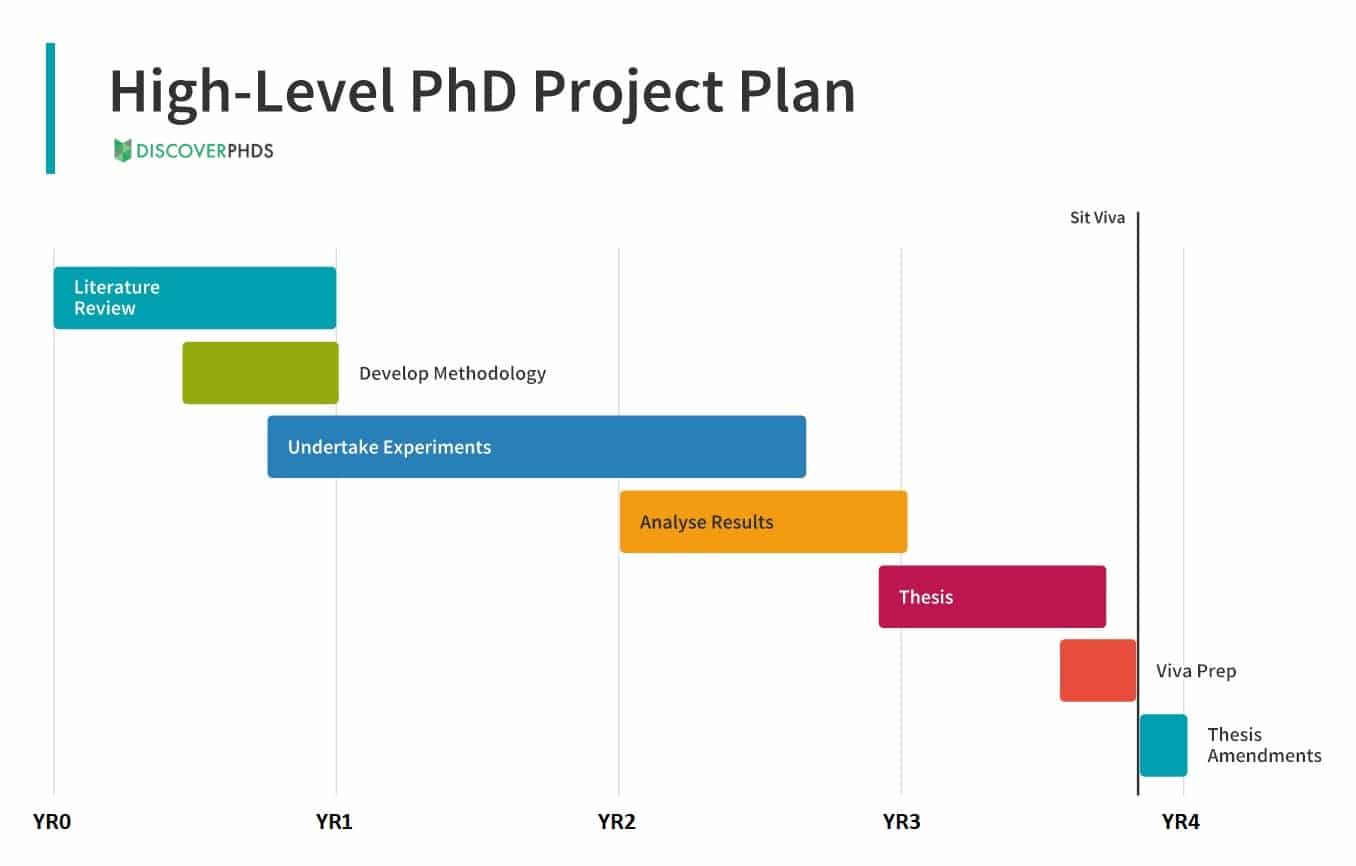

- Abstract : The abstract is a brief summary that quickly outlines your research, touches on each of the main sections of your thesis, and clearly outlines your contribution to the field by way of your PhD thesis. Even though the abstract is very short, similar to what you’ve seen in published research articles, its impact shouldn’t be underestimated. The abstract is there to answer the most important question to the reviewer. “Why is this important?”

- Introduction : In this section, you help the reviewer understand your entire dissertation, including what your paper is about, why it’s important to the field, a brief description of your methodology, and how your research and the thesis are laid out. Think of your introduction as an expansion of your abstract.

- Literature Review : Within the literature review, you are making a case for your new research by telling the story of the work that’s already been done. You’ll cover a bit about the history of the topic at hand, and how your study fits into the present and future.

- Theory Framework : Here, you explain assumptions related to your study. Here you’re explaining to the review what theoretical concepts you might have used in your research, how it relates to existing knowledge and ideas.

- Methods : This section of a PhD thesis is typically the most detailed and descriptive, depending of course on your research design. Here you’ll discuss the specific techniques you used to get the information you were looking for, in addition to how those methods are relevant and appropriate, as well as how you specifically used each method described.

- Results : Here you present your empirical findings. This section is sometimes also called the “empiracles” chapter. This section is usually pretty straightforward and technical, and full of details. Don’t shortcut this chapter.

- Discussion : This can be a tricky chapter, because it’s where you want to show the reviewer that you know what you’re talking about. You need to speak as a PhD versus a student. The discussion chapter is similar to the empirical/results chapter, but you’re building on those results to push the new information that you learned, prior to making your conclusion.

- Conclusion : Here, you take a step back and reflect on what your original goals and intentions for the research were. You’ll outline them in context of your new findings and expertise.

Tips for your PhD Thesis Format

As you put together your PhD thesis, it’s easy to get a little overwhelmed. Here are some tips that might keep you on track.

- Don’t try to write your PhD as a first-draft. Every great masterwork has typically been edited, and edited, and…edited.

- Work with your thesis supervisor to plan the structure and format of your PhD thesis. Be prepared to rewrite each section, as you work out rough drafts. Don’t get discouraged by this process. It’s typical.

- Make your writing interesting. Academic writing has a reputation of being very dry.

- You don’t have to necessarily work on the chapters and sections outlined above in chronological order. Work on each section as things come up, and while your work on that section is relevant to what you’re doing.

- Don’t rush things. Write a first draft, and leave it for a few days, so you can come back to it with a more critical take. Look at it objectively and carefully grammatical errors, clarity, logic and flow.

- Know what style your references need to be in, and utilize tools out there to organize them in the required format.

- It’s easier to accidentally plagiarize than you think. Make sure you’re referencing appropriately, and check your document for inadvertent plagiarism throughout your writing process.

PhD Thesis Editing Plus

Want some support during your PhD writing process? Our PhD Thesis Editing Plus service includes extensive and detailed editing of your thesis to improve the flow and quality of your writing. Unlimited editing support for guaranteed results. Learn more here , and get started today!

- Publication Process

Journal Acceptance Rates: Everything You Need to Know

- Publication Recognition

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Dissertation & Thesis Guides

- Basics of Dissertation & Thesis Writing

- How to Write an Abstract for a Dissertation or Thesis: Guide & Examples

- Speech Topics

- Basics of Essay Writing

- Essay Topics

- Other Essays

- Main Academic Essays

- Research Paper Topics

- Basics of Research Paper Writing

- Miscellaneous

- Chicago/ Turabian

- Data & Statistics

- Methodology

- Admission Writing Tips

- Admission Advice

- Other Guides

- Student Life

- Studying Tips

- Understanding Plagiarism

- Academic Writing Tips

- Essay Guides

- Research Paper Guides

- Formatting Guides

- Basics of Research Process

- Admission Guides

How to Write an Abstract for a Dissertation or Thesis: Guide & Examples

Table of contents

Use our free Readability checker

A dissertation abstract is a brief summary of a dissertation, typically between 150-300 words. It is a standalone piece of writing that gives the reader an overview of the main ideas and findings of the dissertation.

Generally, this section should include:

- Research problem and questions

- Research methodology

- Key findings and results

- Original contribution

- Practical or theoretical implications.

You need to write an excellent abstract for a dissertation or thesis, since it's the first thing a comitteee will review. Continue reading through to learn how to write a dissertation abstract. In this article, we will discuss its purpose, length, structure and writing steps. Moreover, for reference purposes, this article will include abstract examples for a dissertation and thesis and offer extra guidance on top of that.

In case you are in a hurry, feel free to buy dissertation from our professional writers. Our experts are qualified and have solid experience in writing Ph.D. academic works.

What Is a Dissertation Abstract?

Dissertation abstracts, by definition, are summaries of a thesis's content, usually between 200 and 300 words, used to inform readers about the contents of the study in a quick way. A thesis or dissertation abstract briefly overviews the entire thesis. Dissertation abstracts are found at the beginning of every study, providing the research recap, results, and conclusions. It usually goes right after your title page and before your dissertation table of contents . An abstract for a dissertation (alternatively called “précis” further in the article) should clearly state the main topic of your paper, its overall purpose, and any important research questions or findings. It should also contain any necessary keywords that direct readers to relevant information. In addition, it addresses any implications for further research that may stem from its field. Writing strong précis requires you to think carefully, as they are the critical components that attract readers to peruse your paper.

Purpose of a Dissertation or Thesis Abstract

The primary purpose of an abstract in a dissertation or thesis is to give readers a basic understanding of the completed work. Also, it should create an interest in the topic to motivate readers to read further. Writing an abstract for a dissertation is essential for many reasons:

- Offers a summary and gives readers an overview of what they should expect from your study.

- Provides an opportunity to showcase the research done, highlighting its importance and impact.

- Identifies any unexplored research gaps to inform future studies and direct the current state of knowledge on the topic.

In general, an abstract of a thesis or a dissertation is a bridge between the research and potential readers.

What Makes a Good Abstract for a Dissertation?

Making a good dissertation abstract requires excellent organization and clarity of thought. Proper specimens must provide convincing arguments supporting your thesis. Writing an effective dissertation abstract requires students to be concise and write engagingly. Below is a list of things that makes it outstanding:

- Maintains clear and concise summary style

- Includes essential keywords for search engine optimization

- Accurately conveys the scope of the thesis

- Strictly adheres to the word count limit specified in your instructions

- Written from a third-person point of view

- Includes objectives, approach, and findings

- Uses simple language without jargon

- Avoids overgeneralized statements or vague claims.

How Long Should a Dissertation Abstract Be?

Abstracts should be long enough to convey the key points of every thesis, yet brief enough to capture readers' attention. A dissertation abstract length should typically be between 200-300 words, i.e., 1 page. But usually, length is indicated in the requirements. Remember that your primary goal here is to provide an engaging and informative thesis summary. Note that following the instructions and templates set forth by your university will ensure your thesis or dissertation abstract meets the writing criteria and adheres to all relevant standards.

Dissertation Abstract Structure

Dissertation abstracts can be organized in different ways and vary slightly depending on your work requirements. However, each abstract of a dissertation should incorporate elements like keywords, methods, results, and conclusions. The structure of a thesis or a dissertation abstract should account for the components included below:

- Title Accurately reflects the topic of your thesis.

- Introduction Provides an overview of your research, its purpose, and any relevant background information.

- Methods/ Approach Gives an outline of the methods used to conduct your research.

- Results Summarizes your findings.

- Conclusions Provides an overview of your research's accomplishments and implications.

- Keywords Includes keywords that accurately describe your thesis.

Below is an example that shows how a dissertation abstract looks, how to structure it and where each part is located. Use this template to organize your own summary.

Things to Consider Before Writing a Dissertation Abstract

There are several things you should do beforehand in order to write a good abstract for a dissertation or thesis. They include:

- Reviewing set requirements and making sure you clearly understand the expectations

- Reading other research works to get an idea of what to include in yours

- Writing a few drafts before submitting your final version, which will ensure that it's in the best state possible.

Write an Abstract for a Dissertation Last

Remember, it's advisable to write an abstract for a thesis paper or dissertation last. Even though it’s always located in the beginning of the work, nevertheless, it should be written last. This way, your summary will be more accurate because the main argument and conclusions are already known when the work is mostly finished - it is incomparably easier to write a dissertation abstract after completing your thesis. Additionally, you should write it last because the contents and scope of the thesis may have changed during the writing process. So, create your dissertation abstract as a last step to help ensure that it precisely reflects the content of your project.

Carefully Read Requirements

Writing dissertation abstracts requires careful attention to details and adherence to writing requirements. Refer to the rubric or guidelines that you were presented with to identify aspects to keep in mind and important elements, such as correct length and writing style, and then make sure to comprehensively include them. Careful consideration of these requirements ensures that your writing meets every criterion and standard provided by your supervisor to increase the chances that your master's thesis is accepted and approved.

Choose the Right Type of Dissertation Abstracts

Before starting to write a dissertation or thesis abstract you should choose the appropriate type. Several options are available, and it is essential to pick one that best suits your dissertation's subject. Depending on their purpose, there exist 3 types of dissertation abstracts:

- Informative

- Descriptive

Informative one offers readers a concise overview of your research, its purpose, and any relevant background information. Additionally, this type includes brief summaries of all results and dissertation conclusions . A descriptive abstract in a dissertation or thesis provides a quick overview of the research, but it doesn't incorporate any evaluation or analysis because it only offers a snapshot of the study and makes no claims.

Critical abstract gives readers an in-depth overview of the research and include an evaluative component. This means that this type also summarizes and analyzes research data, discusses implications, and makes claims about the achievements of your study. In addition, it examines the research data and recounts its implications.

Choose the correct type of dissertation abstract to ensure that it meets your paper’s demands.

How to Write an Abstract for a Dissertation or Thesis?