- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Research Paper Structure

Whether you are writing a B.S. Degree Research Paper or completing a research report for a Psychology course, it is highly likely that you will need to organize your research paper in accordance with American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines. Here we discuss the structure of research papers according to APA style.

Major Sections of a Research Paper in APA Style

A complete research paper in APA style that is reporting on experimental research will typically contain a Title page, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and References sections. 1 Many will also contain Figures and Tables and some will have an Appendix or Appendices. These sections are detailed as follows (for a more in-depth guide, please refer to " How to Write a Research Paper in APA Style ”, a comprehensive guide developed by Prof. Emma Geller). 2

What is this paper called and who wrote it? – the first page of the paper; this includes the name of the paper, a “running head”, authors, and institutional affiliation of the authors. The institutional affiliation is usually listed in an Author Note that is placed towards the bottom of the title page. In some cases, the Author Note also contains an acknowledgment of any funding support and of any individuals that assisted with the research project.

One-paragraph summary of the entire study – typically no more than 250 words in length (and in many cases it is well shorter than that), the Abstract provides an overview of the study.

Introduction

What is the topic and why is it worth studying? – the first major section of text in the paper, the Introduction commonly describes the topic under investigation, summarizes or discusses relevant prior research (for related details, please see the Writing Literature Reviews section of this website), identifies unresolved issues that the current research will address, and provides an overview of the research that is to be described in greater detail in the sections to follow.

What did you do? – a section which details how the research was performed. It typically features a description of the participants/subjects that were involved, the study design, the materials that were used, and the study procedure. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Methods section. A rule of thumb is that the Methods section should be sufficiently detailed for another researcher to duplicate your research.

What did you find? – a section which describes the data that was collected and the results of any statistical tests that were performed. It may also be prefaced by a description of the analysis procedure that was used. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Results section.

What is the significance of your results? – the final major section of text in the paper. The Discussion commonly features a summary of the results that were obtained in the study, describes how those results address the topic under investigation and/or the issues that the research was designed to address, and may expand upon the implications of those findings. Limitations and directions for future research are also commonly addressed.

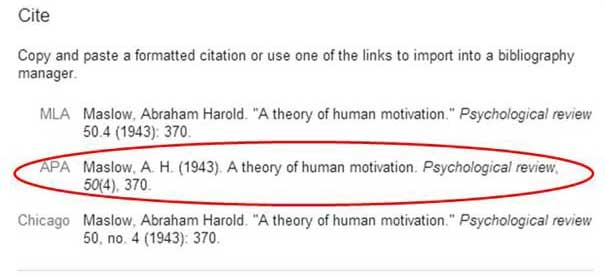

List of articles and any books cited – an alphabetized list of the sources that are cited in the paper (by last name of the first author of each source). Each reference should follow specific APA guidelines regarding author names, dates, article titles, journal titles, journal volume numbers, page numbers, book publishers, publisher locations, websites, and so on (for more information, please see the Citing References in APA Style page of this website).

Tables and Figures

Graphs and data (optional in some cases) – depending on the type of research being performed, there may be Tables and/or Figures (however, in some cases, there may be neither). In APA style, each Table and each Figure is placed on a separate page and all Tables and Figures are included after the References. Tables are included first, followed by Figures. However, for some journals and undergraduate research papers (such as the B.S. Research Paper or Honors Thesis), Tables and Figures may be embedded in the text (depending on the instructor’s or editor’s policies; for more details, see "Deviations from APA Style" below).

Supplementary information (optional) – in some cases, additional information that is not critical to understanding the research paper, such as a list of experiment stimuli, details of a secondary analysis, or programming code, is provided. This is often placed in an Appendix.

Variations of Research Papers in APA Style

Although the major sections described above are common to most research papers written in APA style, there are variations on that pattern. These variations include:

- Literature reviews – when a paper is reviewing prior published research and not presenting new empirical research itself (such as in a review article, and particularly a qualitative review), then the authors may forgo any Methods and Results sections. Instead, there is a different structure such as an Introduction section followed by sections for each of the different aspects of the body of research being reviewed, and then perhaps a Discussion section.

- Multi-experiment papers – when there are multiple experiments, it is common to follow the Introduction with an Experiment 1 section, itself containing Methods, Results, and Discussion subsections. Then there is an Experiment 2 section with a similar structure, an Experiment 3 section with a similar structure, and so on until all experiments are covered. Towards the end of the paper there is a General Discussion section followed by References. Additionally, in multi-experiment papers, it is common for the Results and Discussion subsections for individual experiments to be combined into single “Results and Discussion” sections.

Departures from APA Style

In some cases, official APA style might not be followed (however, be sure to check with your editor, instructor, or other sources before deviating from standards of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association). Such deviations may include:

- Placement of Tables and Figures – in some cases, to make reading through the paper easier, Tables and/or Figures are embedded in the text (for example, having a bar graph placed in the relevant Results section). The embedding of Tables and/or Figures in the text is one of the most common deviations from APA style (and is commonly allowed in B.S. Degree Research Papers and Honors Theses; however you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first).

- Incomplete research – sometimes a B.S. Degree Research Paper in this department is written about research that is currently being planned or is in progress. In those circumstances, sometimes only an Introduction and Methods section, followed by References, is included (that is, in cases where the research itself has not formally begun). In other cases, preliminary results are presented and noted as such in the Results section (such as in cases where the study is underway but not complete), and the Discussion section includes caveats about the in-progress nature of the research. Again, you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first.

- Class assignments – in some classes in this department, an assignment must be written in APA style but is not exactly a traditional research paper (for instance, a student asked to write about an article that they read, and to write that report in APA style). In that case, the structure of the paper might approximate the typical sections of a research paper in APA style, but not entirely. You should check with your instructor for further guidelines.

Workshops and Downloadable Resources

- For in-person discussion of the process of writing research papers, please consider attending this department’s “Writing Research Papers” workshop (for dates and times, please check the undergraduate workshops calendar).

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – empirical research) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

APA Journal Article Reporting Guidelines

- Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R. B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A. M., & Rao, S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 3.

- Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 26.

External Resources

- Formatting APA Style Papers in Microsoft Word

- How to Write an APA Style Research Paper from Hamilton University

- WikiHow Guide to Writing APA Research Papers

- Sample APA Formatted Paper with Comments

- Sample APA Formatted Paper

- Tips for Writing a Paper in APA Style

1 VandenBos, G. R. (Ed). (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.) (pp. 41-60). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

2 geller, e. (2018). how to write an apa-style research report . [instructional materials]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing a Literature Review

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 11: Presenting Your Research

Writing a Research Report in American Psychological Association (APA) Style

Learning Objectives

- Identify the major sections of an APA-style research report and the basic contents of each section.

- Plan and write an effective APA-style research report.

In this section, we look at how to write an APA-style empirical research report , an article that presents the results of one or more new studies. Recall that the standard sections of an empirical research report provide a kind of outline. Here we consider each of these sections in detail, including what information it contains, how that information is formatted and organized, and tips for writing each section. At the end of this section is a sample APA-style research report that illustrates many of these principles.

Sections of a Research Report

Title page and abstract.

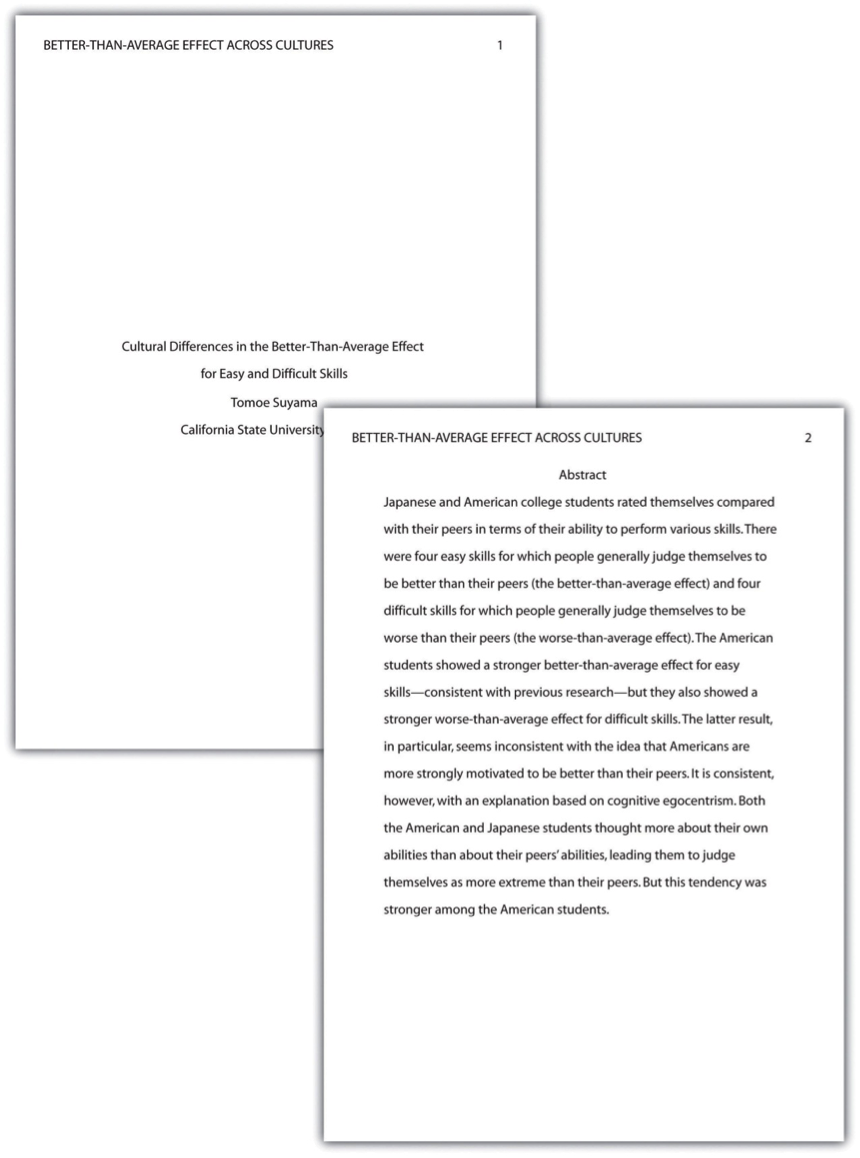

An APA-style research report begins with a title page . The title is centred in the upper half of the page, with each important word capitalized. The title should clearly and concisely (in about 12 words or fewer) communicate the primary variables and research questions. This sometimes requires a main title followed by a subtitle that elaborates on the main title, in which case the main title and subtitle are separated by a colon. Here are some titles from recent issues of professional journals published by the American Psychological Association.

- Sex Differences in Coping Styles and Implications for Depressed Mood

- Effects of Aging and Divided Attention on Memory for Items and Their Contexts

- Computer-Assisted Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Child Anxiety: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial

- Virtual Driving and Risk Taking: Do Racing Games Increase Risk-Taking Cognitions, Affect, and Behaviour?

Below the title are the authors’ names and, on the next line, their institutional affiliation—the university or other institution where the authors worked when they conducted the research. As we have already seen, the authors are listed in an order that reflects their contribution to the research. When multiple authors have made equal contributions to the research, they often list their names alphabetically or in a randomly determined order.

In some areas of psychology, the titles of many empirical research reports are informal in a way that is perhaps best described as “cute.” They usually take the form of a play on words or a well-known expression that relates to the topic under study. Here are some examples from recent issues of the Journal Psychological Science .

- “Smells Like Clean Spirit: Nonconscious Effects of Scent on Cognition and Behavior”

- “Time Crawls: The Temporal Resolution of Infants’ Visual Attention”

- “Scent of a Woman: Men’s Testosterone Responses to Olfactory Ovulation Cues”

- “Apocalypse Soon?: Dire Messages Reduce Belief in Global Warming by Contradicting Just-World Beliefs”

- “Serial vs. Parallel Processing: Sometimes They Look Like Tweedledum and Tweedledee but They Can (and Should) Be Distinguished”

- “How Do I Love Thee? Let Me Count the Words: The Social Effects of Expressive Writing”

Individual researchers differ quite a bit in their preference for such titles. Some use them regularly, while others never use them. What might be some of the pros and cons of using cute article titles?

For articles that are being submitted for publication, the title page also includes an author note that lists the authors’ full institutional affiliations, any acknowledgments the authors wish to make to agencies that funded the research or to colleagues who commented on it, and contact information for the authors. For student papers that are not being submitted for publication—including theses—author notes are generally not necessary.

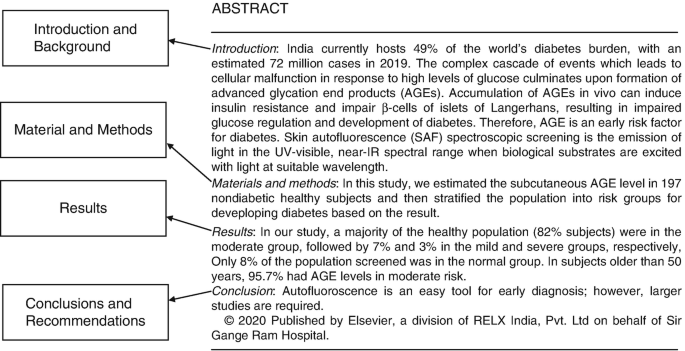

The abstract is a summary of the study. It is the second page of the manuscript and is headed with the word Abstract . The first line is not indented. The abstract presents the research question, a summary of the method, the basic results, and the most important conclusions. Because the abstract is usually limited to about 200 words, it can be a challenge to write a good one.

Introduction

The introduction begins on the third page of the manuscript. The heading at the top of this page is the full title of the manuscript, with each important word capitalized as on the title page. The introduction includes three distinct subsections, although these are typically not identified by separate headings. The opening introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting, the literature review discusses relevant previous research, and the closing restates the research question and comments on the method used to answer it.

The Opening

The opening , which is usually a paragraph or two in length, introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting. To capture the reader’s attention, researcher Daryl Bem recommends starting with general observations about the topic under study, expressed in ordinary language (not technical jargon)—observations that are about people and their behaviour (not about researchers or their research; Bem, 2003 [1] ). Concrete examples are often very useful here. According to Bem, this would be a poor way to begin a research report:

Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance received a great deal of attention during the latter part of the 20th century (p. 191)

The following would be much better:

The individual who holds two beliefs that are inconsistent with one another may feel uncomfortable. For example, the person who knows that he or she enjoys smoking but believes it to be unhealthy may experience discomfort arising from the inconsistency or disharmony between these two thoughts or cognitions. This feeling of discomfort was called cognitive dissonance by social psychologist Leon Festinger (1957), who suggested that individuals will be motivated to remove this dissonance in whatever way they can (p. 191).

After capturing the reader’s attention, the opening should go on to introduce the research question and explain why it is interesting. Will the answer fill a gap in the literature? Will it provide a test of an important theory? Does it have practical implications? Giving readers a clear sense of what the research is about and why they should care about it will motivate them to continue reading the literature review—and will help them make sense of it.

Breaking the Rules

Researcher Larry Jacoby reported several studies showing that a word that people see or hear repeatedly can seem more familiar even when they do not recall the repetitions—and that this tendency is especially pronounced among older adults. He opened his article with the following humourous anecdote:

A friend whose mother is suffering symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) tells the story of taking her mother to visit a nursing home, preliminary to her mother’s moving there. During an orientation meeting at the nursing home, the rules and regulations were explained, one of which regarded the dining room. The dining room was described as similar to a fine restaurant except that tipping was not required. The absence of tipping was a central theme in the orientation lecture, mentioned frequently to emphasize the quality of care along with the advantages of having paid in advance. At the end of the meeting, the friend’s mother was asked whether she had any questions. She replied that she only had one question: “Should I tip?” (Jacoby, 1999, p. 3)

Although both humour and personal anecdotes are generally discouraged in APA-style writing, this example is a highly effective way to start because it both engages the reader and provides an excellent real-world example of the topic under study.

The Literature Review

Immediately after the opening comes the literature review , which describes relevant previous research on the topic and can be anywhere from several paragraphs to several pages in length. However, the literature review is not simply a list of past studies. Instead, it constitutes a kind of argument for why the research question is worth addressing. By the end of the literature review, readers should be convinced that the research question makes sense and that the present study is a logical next step in the ongoing research process.

Like any effective argument, the literature review must have some kind of structure. For example, it might begin by describing a phenomenon in a general way along with several studies that demonstrate it, then describing two or more competing theories of the phenomenon, and finally presenting a hypothesis to test one or more of the theories. Or it might describe one phenomenon, then describe another phenomenon that seems inconsistent with the first one, then propose a theory that resolves the inconsistency, and finally present a hypothesis to test that theory. In applied research, it might describe a phenomenon or theory, then describe how that phenomenon or theory applies to some important real-world situation, and finally suggest a way to test whether it does, in fact, apply to that situation.

Looking at the literature review in this way emphasizes a few things. First, it is extremely important to start with an outline of the main points that you want to make, organized in the order that you want to make them. The basic structure of your argument, then, should be apparent from the outline itself. Second, it is important to emphasize the structure of your argument in your writing. One way to do this is to begin the literature review by summarizing your argument even before you begin to make it. “In this article, I will describe two apparently contradictory phenomena, present a new theory that has the potential to resolve the apparent contradiction, and finally present a novel hypothesis to test the theory.” Another way is to open each paragraph with a sentence that summarizes the main point of the paragraph and links it to the preceding points. These opening sentences provide the “transitions” that many beginning researchers have difficulty with. Instead of beginning a paragraph by launching into a description of a previous study, such as “Williams (2004) found that…,” it is better to start by indicating something about why you are describing this particular study. Here are some simple examples:

Another example of this phenomenon comes from the work of Williams (2004).

Williams (2004) offers one explanation of this phenomenon.

An alternative perspective has been provided by Williams (2004).

We used a method based on the one used by Williams (2004).

Finally, remember that your goal is to construct an argument for why your research question is interesting and worth addressing—not necessarily why your favourite answer to it is correct. In other words, your literature review must be balanced. If you want to emphasize the generality of a phenomenon, then of course you should discuss various studies that have demonstrated it. However, if there are other studies that have failed to demonstrate it, you should discuss them too. Or if you are proposing a new theory, then of course you should discuss findings that are consistent with that theory. However, if there are other findings that are inconsistent with it, again, you should discuss them too. It is acceptable to argue that the balance of the research supports the existence of a phenomenon or is consistent with a theory (and that is usually the best that researchers in psychology can hope for), but it is not acceptable to ignore contradictory evidence. Besides, a large part of what makes a research question interesting is uncertainty about its answer.

The Closing

The closing of the introduction—typically the final paragraph or two—usually includes two important elements. The first is a clear statement of the main research question or hypothesis. This statement tends to be more formal and precise than in the opening and is often expressed in terms of operational definitions of the key variables. The second is a brief overview of the method and some comment on its appropriateness. Here, for example, is how Darley and Latané (1968) [2] concluded the introduction to their classic article on the bystander effect:

These considerations lead to the hypothesis that the more bystanders to an emergency, the less likely, or the more slowly, any one bystander will intervene to provide aid. To test this proposition it would be necessary to create a situation in which a realistic “emergency” could plausibly occur. Each subject should also be blocked from communicating with others to prevent his getting information about their behaviour during the emergency. Finally, the experimental situation should allow for the assessment of the speed and frequency of the subjects’ reaction to the emergency. The experiment reported below attempted to fulfill these conditions. (p. 378)

Thus the introduction leads smoothly into the next major section of the article—the method section.

The method section is where you describe how you conducted your study. An important principle for writing a method section is that it should be clear and detailed enough that other researchers could replicate the study by following your “recipe.” This means that it must describe all the important elements of the study—basic demographic characteristics of the participants, how they were recruited, whether they were randomly assigned, how the variables were manipulated or measured, how counterbalancing was accomplished, and so on. At the same time, it should avoid irrelevant details such as the fact that the study was conducted in Classroom 37B of the Industrial Technology Building or that the questionnaire was double-sided and completed using pencils.

The method section begins immediately after the introduction ends with the heading “Method” (not “Methods”) centred on the page. Immediately after this is the subheading “Participants,” left justified and in italics. The participants subsection indicates how many participants there were, the number of women and men, some indication of their age, other demographics that may be relevant to the study, and how they were recruited, including any incentives given for participation.

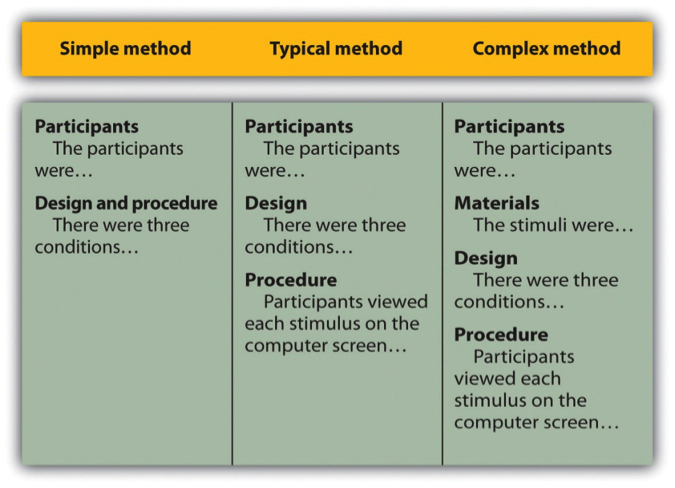

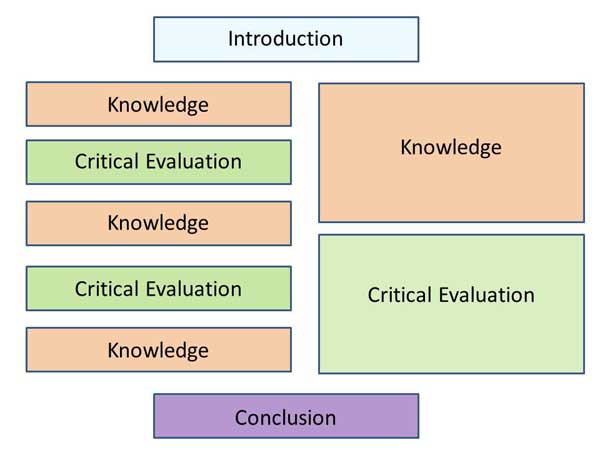

After the participants section, the structure can vary a bit. Figure 11.1 shows three common approaches. In the first, the participants section is followed by a design and procedure subsection, which describes the rest of the method. This works well for methods that are relatively simple and can be described adequately in a few paragraphs. In the second approach, the participants section is followed by separate design and procedure subsections. This works well when both the design and the procedure are relatively complicated and each requires multiple paragraphs.

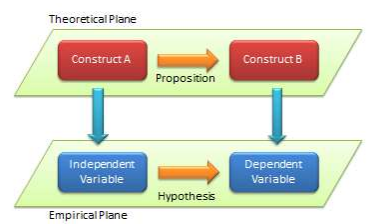

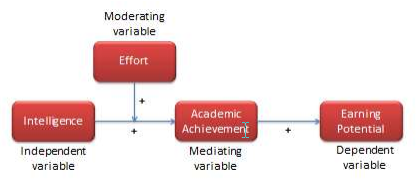

What is the difference between design and procedure? The design of a study is its overall structure. What were the independent and dependent variables? Was the independent variable manipulated, and if so, was it manipulated between or within subjects? How were the variables operationally defined? The procedure is how the study was carried out. It often works well to describe the procedure in terms of what the participants did rather than what the researchers did. For example, the participants gave their informed consent, read a set of instructions, completed a block of four practice trials, completed a block of 20 test trials, completed two questionnaires, and were debriefed and excused.

In the third basic way to organize a method section, the participants subsection is followed by a materials subsection before the design and procedure subsections. This works well when there are complicated materials to describe. This might mean multiple questionnaires, written vignettes that participants read and respond to, perceptual stimuli, and so on. The heading of this subsection can be modified to reflect its content. Instead of “Materials,” it can be “Questionnaires,” “Stimuli,” and so on.

The results section is where you present the main results of the study, including the results of the statistical analyses. Although it does not include the raw data—individual participants’ responses or scores—researchers should save their raw data and make them available to other researchers who request them. Several journals now encourage the open sharing of raw data online.

Although there are no standard subsections, it is still important for the results section to be logically organized. Typically it begins with certain preliminary issues. One is whether any participants or responses were excluded from the analyses and why. The rationale for excluding data should be described clearly so that other researchers can decide whether it is appropriate. A second preliminary issue is how multiple responses were combined to produce the primary variables in the analyses. For example, if participants rated the attractiveness of 20 stimulus people, you might have to explain that you began by computing the mean attractiveness rating for each participant. Or if they recalled as many items as they could from study list of 20 words, did you count the number correctly recalled, compute the percentage correctly recalled, or perhaps compute the number correct minus the number incorrect? A third preliminary issue is the reliability of the measures. This is where you would present test-retest correlations, Cronbach’s α, or other statistics to show that the measures are consistent across time and across items. A final preliminary issue is whether the manipulation was successful. This is where you would report the results of any manipulation checks.

The results section should then tackle the primary research questions, one at a time. Again, there should be a clear organization. One approach would be to answer the most general questions and then proceed to answer more specific ones. Another would be to answer the main question first and then to answer secondary ones. Regardless, Bem (2003) [3] suggests the following basic structure for discussing each new result:

- Remind the reader of the research question.

- Give the answer to the research question in words.

- Present the relevant statistics.

- Qualify the answer if necessary.

- Summarize the result.

Notice that only Step 3 necessarily involves numbers. The rest of the steps involve presenting the research question and the answer to it in words. In fact, the basic results should be clear even to a reader who skips over the numbers.

The discussion is the last major section of the research report. Discussions usually consist of some combination of the following elements:

- Summary of the research

- Theoretical implications

- Practical implications

- Limitations

- Suggestions for future research

The discussion typically begins with a summary of the study that provides a clear answer to the research question. In a short report with a single study, this might require no more than a sentence. In a longer report with multiple studies, it might require a paragraph or even two. The summary is often followed by a discussion of the theoretical implications of the research. Do the results provide support for any existing theories? If not, how can they be explained? Although you do not have to provide a definitive explanation or detailed theory for your results, you at least need to outline one or more possible explanations. In applied research—and often in basic research—there is also some discussion of the practical implications of the research. How can the results be used, and by whom, to accomplish some real-world goal?

The theoretical and practical implications are often followed by a discussion of the study’s limitations. Perhaps there are problems with its internal or external validity. Perhaps the manipulation was not very effective or the measures not very reliable. Perhaps there is some evidence that participants did not fully understand their task or that they were suspicious of the intent of the researchers. Now is the time to discuss these issues and how they might have affected the results. But do not overdo it. All studies have limitations, and most readers will understand that a different sample or different measures might have produced different results. Unless there is good reason to think they would have, however, there is no reason to mention these routine issues. Instead, pick two or three limitations that seem like they could have influenced the results, explain how they could have influenced the results, and suggest ways to deal with them.

Most discussions end with some suggestions for future research. If the study did not satisfactorily answer the original research question, what will it take to do so? What new research questions has the study raised? This part of the discussion, however, is not just a list of new questions. It is a discussion of two or three of the most important unresolved issues. This means identifying and clarifying each question, suggesting some alternative answers, and even suggesting ways they could be studied.

Finally, some researchers are quite good at ending their articles with a sweeping or thought-provoking conclusion. Darley and Latané (1968) [4] , for example, ended their article on the bystander effect by discussing the idea that whether people help others may depend more on the situation than on their personalities. Their final sentence is, “If people understand the situational forces that can make them hesitate to intervene, they may better overcome them” (p. 383). However, this kind of ending can be difficult to pull off. It can sound overreaching or just banal and end up detracting from the overall impact of the article. It is often better simply to end when you have made your final point (although you should avoid ending on a limitation).

The references section begins on a new page with the heading “References” centred at the top of the page. All references cited in the text are then listed in the format presented earlier. They are listed alphabetically by the last name of the first author. If two sources have the same first author, they are listed alphabetically by the last name of the second author. If all the authors are the same, then they are listed chronologically by the year of publication. Everything in the reference list is double-spaced both within and between references.

Appendices, Tables, and Figures

Appendices, tables, and figures come after the references. An appendix is appropriate for supplemental material that would interrupt the flow of the research report if it were presented within any of the major sections. An appendix could be used to present lists of stimulus words, questionnaire items, detailed descriptions of special equipment or unusual statistical analyses, or references to the studies that are included in a meta-analysis. Each appendix begins on a new page. If there is only one, the heading is “Appendix,” centred at the top of the page. If there is more than one, the headings are “Appendix A,” “Appendix B,” and so on, and they appear in the order they were first mentioned in the text of the report.

After any appendices come tables and then figures. Tables and figures are both used to present results. Figures can also be used to illustrate theories (e.g., in the form of a flowchart), display stimuli, outline procedures, and present many other kinds of information. Each table and figure appears on its own page. Tables are numbered in the order that they are first mentioned in the text (“Table 1,” “Table 2,” and so on). Figures are numbered the same way (“Figure 1,” “Figure 2,” and so on). A brief explanatory title, with the important words capitalized, appears above each table. Each figure is given a brief explanatory caption, where (aside from proper nouns or names) only the first word of each sentence is capitalized. More details on preparing APA-style tables and figures are presented later in the book.

Sample APA-Style Research Report

Figures 11.2, 11.3, 11.4, and 11.5 show some sample pages from an APA-style empirical research report originally written by undergraduate student Tomoe Suyama at California State University, Fresno. The main purpose of these figures is to illustrate the basic organization and formatting of an APA-style empirical research report, although many high-level and low-level style conventions can be seen here too.

Key Takeaways

- An APA-style empirical research report consists of several standard sections. The main ones are the abstract, introduction, method, results, discussion, and references.

- The introduction consists of an opening that presents the research question, a literature review that describes previous research on the topic, and a closing that restates the research question and comments on the method. The literature review constitutes an argument for why the current study is worth doing.

- The method section describes the method in enough detail that another researcher could replicate the study. At a minimum, it consists of a participants subsection and a design and procedure subsection.

- The results section describes the results in an organized fashion. Each primary result is presented in terms of statistical results but also explained in words.

- The discussion typically summarizes the study, discusses theoretical and practical implications and limitations of the study, and offers suggestions for further research.

- Practice: Look through an issue of a general interest professional journal (e.g., Psychological Science ). Read the opening of the first five articles and rate the effectiveness of each one from 1 ( very ineffective ) to 5 ( very effective ). Write a sentence or two explaining each rating.

- Practice: Find a recent article in a professional journal and identify where the opening, literature review, and closing of the introduction begin and end.

- Practice: Find a recent article in a professional journal and highlight in a different colour each of the following elements in the discussion: summary, theoretical implications, practical implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Long Descriptions

Figure 11.1 long description: Table showing three ways of organizing an APA-style method section.

In the simple method, there are two subheadings: “Participants” (which might begin “The participants were…”) and “Design and procedure” (which might begin “There were three conditions…”).

In the typical method, there are three subheadings: “Participants” (“The participants were…”), “Design” (“There were three conditions…”), and “Procedure” (“Participants viewed each stimulus on the computer screen…”).

In the complex method, there are four subheadings: “Participants” (“The participants were…”), “Materials” (“The stimuli were…”), “Design” (“There were three conditions…”), and “Procedure” (“Participants viewed each stimulus on the computer screen…”). [Return to Figure 11.1]

- Bem, D. J. (2003). Writing the empirical journal article. In J. M. Darley, M. P. Zanna, & H. R. Roediger III (Eds.), The compleat academic: A practical guide for the beginning social scientist (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ↵

- Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4 , 377–383. ↵

A type of research article which describes one or more new empirical studies conducted by the authors.

The page at the beginning of an APA-style research report containing the title of the article, the authors’ names, and their institutional affiliation.

A summary of a research study.

The third page of a manuscript containing the research question, the literature review, and comments about how to answer the research question.

An introduction to the research question and explanation for why this question is interesting.

A description of relevant previous research on the topic being discusses and an argument for why the research is worth addressing.

The end of the introduction, where the research question is reiterated and the method is commented upon.

The section of a research report where the method used to conduct the study is described.

The main results of the study, including the results from statistical analyses, are presented in a research article.

Section of a research report that summarizes the study's results and interprets them by referring back to the study's theoretical background.

Part of a research report which contains supplemental material.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Lab Report Format: Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

In psychology, a lab report outlines a study’s objectives, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions, ensuring clarity and adherence to APA (or relevant) formatting guidelines.

A typical lab report would include the following sections: title, abstract, introduction, method, results, and discussion.

The title page, abstract, references, and appendices are started on separate pages (subsections from the main body of the report are not). Use double-line spacing of text, font size 12, and include page numbers.

The report should have a thread of arguments linking the prediction in the introduction to the content of the discussion.

This must indicate what the study is about. It must include the variables under investigation. It should not be written as a question.

Title pages should be formatted in APA style .

The abstract provides a concise and comprehensive summary of a research report. Your style should be brief but not use note form. Look at examples in journal articles . It should aim to explain very briefly (about 150 words) the following:

- Start with a one/two sentence summary, providing the aim and rationale for the study.

- Describe participants and setting: who, when, where, how many, and what groups?

- Describe the method: what design, what experimental treatment, what questionnaires, surveys, or tests were used.

- Describe the major findings, including a mention of the statistics used and the significance levels, or simply one sentence summing up the outcome.

- The final sentence(s) outline the study’s “contribution to knowledge” within the literature. What does it all mean? Mention the implications of your findings if appropriate.

The abstract comes at the beginning of your report but is written at the end (as it summarises information from all the other sections of the report).

Introduction

The purpose of the introduction is to explain where your hypothesis comes from (i.e., it should provide a rationale for your research study).

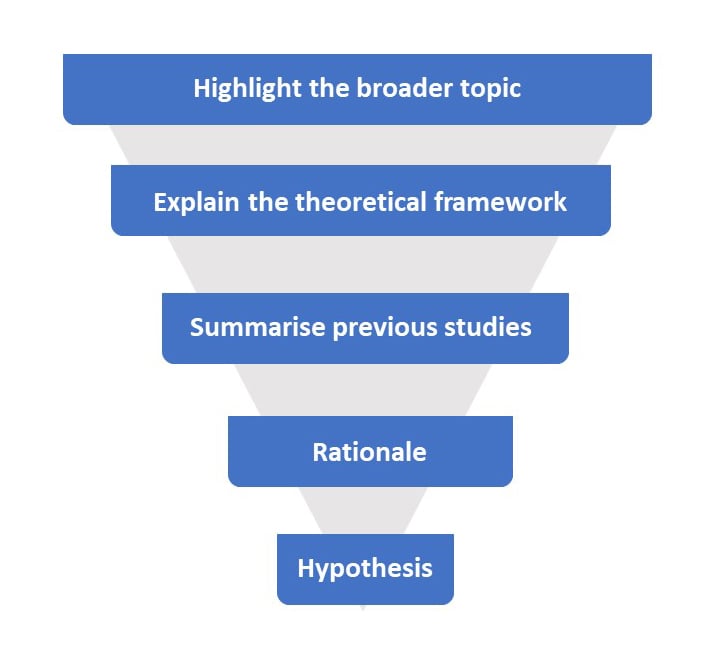

Ideally, the introduction should have a funnel structure: Start broad and then become more specific. The aims should not appear out of thin air; the preceding review of psychological literature should lead logically into the aims and hypotheses.

- Start with general theory, briefly introducing the topic. Define the important key terms.

- Explain the theoretical framework.

- Summarise and synthesize previous studies – What was the purpose? Who were the participants? What did they do? What did they find? What do these results mean? How do the results relate to the theoretical framework?

- Rationale: How does the current study address a gap in the literature? Perhaps it overcomes a limitation of previous research.

- Aims and hypothesis. Write a paragraph explaining what you plan to investigate and make a clear and concise prediction regarding the results you expect to find.

There should be a logical progression of ideas that aids the flow of the report. This means the studies outlined should lead logically to your aims and hypotheses.

Do be concise and selective, and avoid the temptation to include anything in case it is relevant (i.e., don’t write a shopping list of studies).

USE THE FOLLOWING SUBHEADINGS:

Participants

- How many participants were recruited?

- Say how you obtained your sample (e.g., opportunity sample).

- Give relevant demographic details (e.g., gender, ethnicity, age range, mean age, and standard deviation).

- State the experimental design .

- What were the independent and dependent variables ? Make sure the independent variable is labeled and name the different conditions/levels.

- For example, if gender is the independent variable label, then male and female are the levels/conditions/groups.

- How were the IV and DV operationalized?

- Identify any controls used, e.g., counterbalancing and control of extraneous variables.

- List all the materials and measures (e.g., what was the title of the questionnaire? Was it adapted from a study?).

- You do not need to include wholesale replication of materials – instead, include a ‘sensible’ (illustrate) level of detail. For example, give examples of questionnaire items.

- Include the reliability (e.g., alpha values) for the measure(s).

- Describe the precise procedure you followed when conducting your research, i.e., exactly what you did.

- Describe in sufficient detail to allow for replication of findings.

- Be concise in your description and omit extraneous/trivial details, e.g., you don’t need to include details regarding instructions, debrief, record sheets, etc.

- Assume the reader has no knowledge of what you did and ensure that he/she can replicate (i.e., copy) your study exactly by what you write in this section.

- Write in the past tense.

- Don’t justify or explain in the Method (e.g., why you chose a particular sampling method); just report what you did.

- Only give enough detail for someone to replicate the experiment – be concise in your writing.

- The results section of a paper usually presents descriptive statistics followed by inferential statistics.

- Report the means, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each IV level. If you have four to 20 numbers to present, a well-presented table is best, APA style.

- Name the statistical test being used.

- Report appropriate statistics (e.g., t-scores, p values ).

- Report the magnitude (e.g., are the results significant or not?) as well as the direction of the results (e.g., which group performed better?).

- It is optional to report the effect size (this does not appear on the SPSS output).

- Avoid interpreting the results (save this for the discussion).

- Make sure the results are presented clearly and concisely. A table can be used to display descriptive statistics if this makes the data easier to understand.

- DO NOT include any raw data.

- Follow APA style.

Use APA Style

- Numbers reported to 2 d.p. (incl. 0 before the decimal if 1.00, e.g., “0.51”). The exceptions to this rule: Numbers which can never exceed 1.0 (e.g., p -values, r-values): report to 3 d.p. and do not include 0 before the decimal place, e.g., “.001”.

- Percentages and degrees of freedom: report as whole numbers.

- Statistical symbols that are not Greek letters should be italicized (e.g., M , SD , t , X 2 , F , p , d ).

- Include spaces on either side of the equals sign.

- When reporting 95%, CIs (confidence intervals), upper and lower limits are given inside square brackets, e.g., “95% CI [73.37, 102.23]”

- Outline your findings in plain English (avoid statistical jargon) and relate your results to your hypothesis, e.g., is it supported or rejected?

- Compare your results to background materials from the introduction section. Are your results similar or different? Discuss why/why not.

- How confident can we be in the results? Acknowledge limitations, but only if they can explain the result obtained. If the study has found a reliable effect, be very careful suggesting limitations as you are doubting your results. Unless you can think of any c onfounding variable that can explain the results instead of the IV, it would be advisable to leave the section out.

- Suggest constructive ways to improve your study if appropriate.

- What are the implications of your findings? Say what your findings mean for how people behave in the real world.

- Suggest an idea for further research triggered by your study, something in the same area but not simply an improved version of yours. Perhaps you could base this on a limitation of your study.

- Concluding paragraph – Finish with a statement of your findings and the key points of the discussion (e.g., interpretation and implications) in no more than 3 or 4 sentences.

Reference Page

The reference section lists all the sources cited in the essay (alphabetically). It is not a bibliography (a list of the books you used).

In simple terms, every time you refer to a psychologist’s name (and date), you need to reference the original source of information.

If you have been using textbooks this is easy as the references are usually at the back of the book and you can just copy them down. If you have been using websites then you may have a problem as they might not provide a reference section for you to copy.

References need to be set out APA style :

Author, A. A. (year). Title of work . Location: Publisher.

Journal Articles

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Article title. Journal Title, volume number (issue number), page numbers

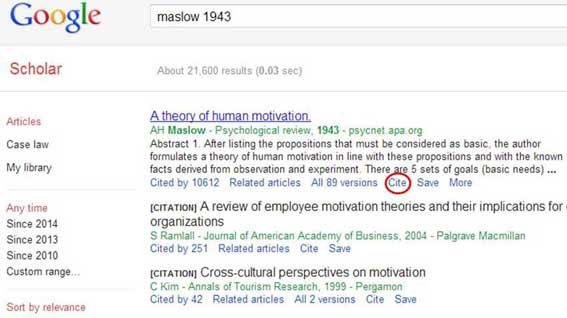

A simple way to write your reference section is to use Google scholar . Just type the name and date of the psychologist in the search box and click on the “cite” link.

Next, copy and paste the APA reference into the reference section of your essay.

Once again, remember that references need to be in alphabetical order according to surname.

Psychology Lab Report Example

Quantitative paper template.

Quantitative professional paper template: Adapted from “Fake News, Fast and Slow: Deliberation Reduces Belief in False (but Not True) News Headlines,” by B. Bago, D. G. Rand, and G. Pennycook, 2020, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General , 149 (8), pp. 1608–1613 ( https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000729 ). Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Qualitative paper template

Qualitative professional paper template: Adapted from “‘My Smartphone Is an Extension of Myself’: A Holistic Qualitative Exploration of the Impact of Using a Smartphone,” by L. J. Harkin and D. Kuss, 2020, Psychology of Popular Media , 10 (1), pp. 28–38 ( https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000278 ). Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Related Articles

Student Resources

How To Cite A YouTube Video In APA Style – With Examples

How to Write an Abstract APA Format

APA References Page Formatting and Example

APA Title Page (Cover Page) Format, Example, & Templates

How do I Cite a Source with Multiple Authors in APA Style?

How to Write a Psychology Essay

Live revision! Join us for our free exam revision livestreams Watch now →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Psychology news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Psychology Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

The abstract is the first section in a psychological report or journal. It includes a summary of the aims, hypothesis, method, results and conclusions, and thus provides an overview of the entire report.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

Example Answers for Research Methods: A Level Psychology, Paper 2, June 2019 (AQA)

Exam Support

Research Methods: MCQ Revision Test 1 for AQA A Level Psychology

Topic Videos

Example Answers for Research Methods: A Level Psychology, Paper 2, June 2018 (AQA)

A level psychology topic quiz - research methods.

Quizzes & Activities

Our subjects

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

How to Write an Abstract?

- Open Access

- First Online: 24 October 2021

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Samiran Nundy 4 ,

- Atul Kakar 5 &

- Zulfiqar A. Bhutta 6

58k Accesses

5 Altmetric

An abstract is a crisp, short, powerful, and self-contained summary of a research manuscript used to help the reader swiftly determine the paper’s purpose. Although the abstract is the first paragraph of the manuscript it should be written last when all the other sections have been addressed.

Research is formalized curiosity. It is poking and prying with a purpose. — Zora Neale Hurston, American Author, Anthropologist and Filmmaker (1891–1960)

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Writing the Abstract

Abstract and Keywords

Additional Commentaries

1 what is an abstract.

An abstract is usually a standalone document that informs the reader about the details of the manuscript to follow. It is like a trailer to a movie, if the trailer is good, it stimulates the audience to watch the movie. The abstract should be written from scratch and not ‘cut –and-pasted’ [ 1 ].

2 What is the History of the Abstract?

An abstract, in the form of a single paragraph, was first published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in 1960 with the idea that the readers may not have enough time to go through the whole paper, and the first abstract with a defined structure was published in 1991 [ 2 ]. The idea sold and now most original articles and reviews are required to have a structured abstract. The abstract attracts the reader to read the full manuscript [ 3 ].

3 What are the Qualities of a Good Abstract?

The quality of information in an abstract can be summarized by four ‘C’s. It should be:

C: Condensed

C: Critical

4 What are the Types of Abstract?

Before writing the abstract, you need to check with the journal website about which type of abstract it requires, with its length and style in the ‘Instructions to Authors’ section.

The abstract types can be divided into:

Descriptive: Usually written for psychology, social science, and humanities papers. It is about 50–100 words long. No conclusions can be drawn from this abstract as it describes the major points in the paper.

Informative: The majority of abstracts for science-related manuscripts are informative and are surrogates for the research done. They are single paragraphs that provide the reader an overview of the research paper and are about 100–150 words in length. Conclusions can be drawn from the abstracts and in the recommendations written in the last line.

Critical: This type of abstract is lengthy and about 400–500 words. In this, the authors’ own research is discussed for reliability, judgement, and validation. A comparison is also made with similar studies done earlier.

Highlighting: This is rarely used in scientific writing. The style of the abstract is to attract more readers. It is not a balanced or complete overview of the article with which it is published.

Structured: A structured abstract contains information under subheadings like background, aims, material and methods, results, conclusion, and recommendations (Fig. 15.1 ). Most leading journals now carry these.

Example of a structured abstract (with permission editor CMRP)

5 What is the Purpose of an Abstract?

An abstract is written to educate the reader about the study that follows and provide an overview of the science behind it. If written well it also attracts more readers to the article. It also helps the article getting indexed. The fate of a paper both before and after publication often depends upon its abstract. Most readers decide if a paper is worth reading on the basis of the abstract. Additionally, the selection of papers in systematic reviews is often dependent upon the abstract.

6 What are the Steps of Writing an Abstract?

An abstract should be written last after all the other sections of an article have been addressed. A poor abstract may turn off the reader and they may cause indexing errors as well. The abstract should state the purpose of the study, the methodology used, and summarize the results and important conclusions. It is usually written in the IMRAD format and is called a structured abstract [ 4 , 5 ].

I: The introduction in the opening line should state the problem you are addressing.

M: Methodology—what method was chosen to finish the experiment?

R: Results—state the important findings of your study.

D: Discussion—discuss why your study is important.

Mention the following information:

Important results with the statistical information ( p values, confidence intervals, standard/mean deviation).

Arrange all information in a chronological order.

Do not repeat any information.

The last line should state the recommendations from your study.

The abstract should be written in the past tense.

7 What are the Things to Be Avoided While Writing an Abstract?

Cut and paste information from the main text

Hold back important information

Use abbreviations

Tables or Figures

Generalized statements

Arguments about the study

8 What are Key Words?

These are important words that are repeated throughout the manuscript and which help in the indexing of a paper. Depending upon the journal 3–10 key words may be required which are indexed with the help of MESH (Medical Subject Heading).

9 How is an Abstract Written for a Conference Different from a Journal Paper?

The basic concept for writing abstracts is the same. However, in a conference abstract occasionally a table or figure is allowed. A word limit is important in both of them. Many of the abstracts which are presented in conferences are never published in fact one study found that only 27% of the abstracts presented in conferences were published in the next five years [ 6 ].

Table 15.1 gives a template for writing an abstract.

10 What are the Important Recommendations of the International Committees of Medical Journal of Editors?

The recommendations are [ 7 ]:

An abstract is required for original articles, metanalysis, and systematic reviews.

A structured abstract is preferred.

The abstract should mention the purpose of the scientific study, how the procedure was carried out, the analysis used, and principal conclusion.

Clinical trials should be reported according to the CONSORT guidelines.

The trials should also mention the funding and the trial number.

The abstract should be accurate as many readers have access only to the abstract.

11 Conclusions

An Abstract should be written last after all the other sections of the manuscript have been completed and with due care and attention to the details.

It should be structured and written in the IMRAD format.

For many readers, the abstract attracts them to go through the complete content of the article.

The abstract is usually followed by key words that help to index the paper.

Andrade C. How to write a good abstract for a scientific paper or conference presentation? Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:172–5.

Article Google Scholar

Squires BP. Structured abstracts of original research and review articles. CMAJ. 1990;143:619–22.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pierson DJ. How to write an abstract that will be accepted for presentation at a national meeting. Respir Care. 2004 Oct;49:1206–12.

PubMed Google Scholar

Tenenbein M. The abstract and the academic clinician. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1995;11:40–2.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Kashfi K, Ghasemi A. The principles of biomedical scientific writing: abstract and keywords. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2020;18:e100159.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Grover S, Dalton N. Abstract to publication rate: do all the papers presented in conferences see the light of being a full publication? Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:73–9.

Preparing a manuscript for submission to a medical journal. Available on http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/manuscript-preparation/preparing-for-submission.html . Accessed 10 May 2020.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Surgical Gastroenterology and Liver Transplantation, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India

Samiran Nundy

Department of Internal Medicine, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India

Institute for Global Health and Development, The Aga Khan University, South Central Asia, East Africa and United Kingdom, Karachi, Pakistan

Zulfiqar A. Bhutta

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Nundy, S., Kakar, A., Bhutta, Z.A. (2022). How to Write an Abstract?. In: How to Practice Academic Medicine and Publish from Developing Countries?. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5248-6_15

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5248-6_15

Published : 24 October 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-5247-9

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-5248-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How We Use Abstract Thinking

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

MoMo Productions / Getty Images

- How It Develops

Abstract thinking, also known as abstract reasoning, involves the ability to understand and think about complex concepts that, while real, are not tied to concrete experiences, objects, people, or situations.

Abstract thinking is considered a type of higher-order thinking, usually about ideas and principles that are often symbolic or hypothetical. This type of thinking is more complex than the type of thinking that is centered on memorizing and recalling information and facts.

Examples of Abstract Thinking

Examples of abstract concepts include ideas such as:

- Imagination

While these things are real, they aren't concrete, physical things that people can experience directly via their traditional senses.

You likely encounter examples of abstract thinking every day. Stand-up comedians use abstract thinking when they observe absurd or illogical behavior in our world and come up with theories as to why people act the way they do.

You use abstract thinking when you're in a philosophy class or when you're contemplating what would be the most ethical way to conduct your business. If you write a poem or an essay, you're also using abstract thinking.

With all of these examples, concepts that are theoretical and intangible are being translated into a joke, a decision, or a piece of art. (You'll notice that creativity and abstract thinking go hand in hand.)

Abstract Thinking vs. Concrete Thinking

One way of understanding abstract thinking is to compare it with concrete thinking. Concrete thinking, also called concrete reasoning, is tied to specific experiences or objects that can be observed directly.

Research suggests that concrete thinkers tend to focus more on the procedures involved in how a task should be performed, while abstract thinkers are more focused on the reasons why a task should be performed.

It is important to remember that you need both concrete and abstract thinking skills to solve problems in day-to-day life. In many cases, you utilize aspects of both types of thinking to come up with solutions.

Other Types of Thinking

Depending on the type of problem we face, we draw from a number of different styles of thinking, such as:

- Creative thinking : This involves coming up with new ideas, or using existing ideas or objects to come up with a solution or create something new.

- Convergent thinking : Often called linear thinking, this is when a person follows a logical set of steps to select the best solution from already-formulated ideas.

- Critical thinking : This is a type of thinking in which a person tests solutions and analyzes any potential drawbacks.

- Divergent thinking : Often called lateral thinking, this style involves using new thoughts or ideas that are outside of the norm in order to solve problems.

How Abstract Thinking Develops

While abstract thinking is an essential skill, it isn’t something that people are born with. Instead, this cognitive ability develops throughout the course of childhood as children gain new abilities, knowledge, and experiences.

The psychologist Jean Piaget described a theory of cognitive development that outlined this process from birth through adolescence and early adulthood. According to his theory, children go through four distinct stages of intellectual development:

- Sensorimotor stage : During this early period, children's knowledge is derived primarily from their senses.

- Preoperational stage : At this point, children develop the ability to think symbolically.

- Concrete operational stage : At this stage, kids become more logical but their understanding of the world tends to be very concrete.

- Formal operational stage : The ability to reason about concrete information continues to grow during this period, but abstract thinking skills also emerge.

This period of cognitive development when abstract thinking becomes more apparent typically begins around age 12. It is at this age that children become more skilled at thinking about things from the perspective of another person. They are also better able to mentally manipulate abstract ideas as well as notice patterns and relationships between these concepts.

Uses of Abstract Thinking

Abstract thinking is a skill that is essential for the ability to think critically and solve problems. This type of thinking is also related to what is known as fluid intelligence , or the ability to reason and solve problems in unique ways.

Fluid intelligence involves thinking abstractly about problems without relying solely on existing knowledge.

Abstract thinking is used in a number of ways in different aspects of your daily life. Some examples of times you might use this type of thinking:

- When you describe something with a metaphor

- When you talk about something figuratively

- When you come up with creative solutions to a problem

- When you analyze a situation

- When you notice relationships or patterns

- When you form a theory about why something happens

- When you think about a problem from another point of view

Research also suggests that abstract thinking plays a role in the actions people take. Abstract thinkers have been found to be more likely to engage in risky behaviors, where concrete thinkers are more likely to avoid risks.

Impact of Abstract Thinking

People who have strong abstract thinking skills tend to score well on intelligence tests. Because this type of thinking is associated with creativity, abstract thinkers also tend to excel in areas that require creativity such as art, writing, and other areas that benefit from divergent thinking abilities.

Abstract thinking can have both positive and negative effects. It can be used as a tool to promote innovative problem-solving, but it can also lead to problems in some cases:

- Bias : Research also suggests that it can sometimes promote different types of bias . As people seek to understand events, abstract thinking can sometimes cause people to seek out patterns, themes, and relationships that may not exist.

- Catastrophic thinking : Sometimes these inferences, imagined scenarios, and predictions about the future can lead to feelings of fear and anxiety. Instead of making realistic predictions, people may catastrophize and imagine the worst possible potential outcomes.

- Anxiety and depression : Research has also found that abstract thinking styles are sometimes associated with worry and rumination . This thinking style is also associated with a range of conditions including depression , anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) .

Conditions That Impact Abstract Thinking

The presence of learning disabilities and mental health conditions can affect abstract thinking abilities. Conditions that are linked to impaired abstract thinking skills include:

- Learning disabilities

- Schizophrenia

- Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

The natural aging process can also have an impact on abstract thinking skills. Research suggests that the thinking skills associated with fluid intelligence peak around the ages of 30 or 40 and begin to decline with age.

Tips for Reasoning Abstractly

While some psychologists believe that abstract thinking skills are a natural product of normal development, others suggest that these abilities are influenced by genetics, culture, and experiences. Some people may come by these skills naturally, but you can also strengthen these abilities with practice.

Some strategies that you might use to help improve your abstract thinking skills:

- Think about why and not just how : Abstract thinkers tend to focus on the meaning of events or on hypothetical outcomes. Instead of concentrating only on the steps needed to achieve a goal, consider some of the reasons why that goal might be valuable or what might happen if you reach that goal.

- Reframe your thinking : When you are approaching a problem, it can be helpful to purposefully try to think about the problem in a different way. How might someone else approach it? Is there an easier way to accomplish the same thing? Are there any elements you haven't considered?

- Consider the big picture : Rather than focusing on the specifics of a situation, try taking a step back in order to view the big picture. Where concrete thinkers are more likely to concentrate on the details, abstract thinkers focus on how something relates to other things or how it fits into the grand scheme of things.

Abstract thinking allows people to think about complex relationships, recognize patterns, solve problems, and utilize creativity. While some people tend to be naturally better at this type of reasoning, it is a skill that you can learn to utilize and strengthen with practice.

It is important to remember that both concrete and abstract thinking are skills that you need to solve problems and function successfully.

Gilead M, Liberman N, Maril A. From mind to matter: neural correlates of abstract and concrete mindsets . Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci . 2014;9(5):638-45. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst031

American Psychological Association. Creative thinking .

American Psychological Association. Convergent thinking .

American Psychological Association. Critical thinking .

American Psychological Association. Divergent thinking .

Lermer E, Streicher B, Sachs R, Raue M, Frey D. The effect of abstract and concrete thinking on risk-taking behavior in women and men . SAGE Open . 2016;6(3):215824401666612. doi:10.1177/2158244016666127

Namkoong J-E, Henderson MD. Responding to causal uncertainty through abstract thinking . Curr Dir Psychol Sci . 2019;28(6):547-551. doi:10.1177/0963721419859346

White R, Wild J. "Why" or "How": the effect of concrete versus abstract processing on intrusive memories following analogue trauma . Behav Ther . 2016;47(3):404-415. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2016.02.004

Williams DL, Mazefsky CA, Walker JD, Minshew NJ, Goldstein G. Associations between conceptual reasoning, problem solving, and adaptive ability in high-functioning autism . J Autism Dev Disord . 2014 Nov;44(11):2908-20. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2190-y

Oh J, Chun JW, Joon Jo H, Kim E, Park HJ, Lee B, Kim JJ. The neural basis of a deficit in abstract thinking in patients with schizophrenia . Psychiatry Res . 2015;234(1):66-73. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.08.007

Hartshorne JK, Germine LT. When does cognitive functioning peak? The asynchronous rise and fall of different cognitive abilities across the life span . Psychol Sci. 2015;26(4):433-43. doi:10.1177/0956797614567339

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.6(1); 2023

- PMC10573588

Consensus Paper: Current Perspectives on Abstract Concepts and Future Research Directions

Briony banks.

1 Department of Psychology, Lancaster University, UK

Anna M. Borghi

2 Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, and Health Studies, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

3 Institute of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies, Italian National Research Council, Rome, Italy

Raphaël Fargier

4 Department of Special Needs Education, University of Oslo, Norway

Chiara Fini

Domicele jonauskaite.

5 Faculty of Psychology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

6 Institute of Psychology, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

Claudia Mazzuca

Martina montalti.

7 Department of Clinical and Experimental Sciences, University of Brescia, Italy

8 Department of Medicine and Surgery – Unit of Neuroscience, University of Parma, Italy

Caterina Villani

9 Department of Modern Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, University of Bologna, Italy

Greg Woodin

10 Department of English Language and Linguistics, University of Birmingham, UK

Abstract concepts are relevant to a wide range of disciplines, including cognitive science, linguistics, psychology, cognitive, social, and affective neuroscience, and philosophy. This consensus paper synthesizes the work and views of researchers in the field, discussing current perspectives on theoretical and methodological issues, and recommendations for future research. In this paper, we urge researchers to go beyond the traditional abstract-concrete dichotomy and consider the multiple dimensions that characterize concepts (e.g., sensorimotor experience, social interaction, conceptual metaphor), as well as the mediating influence of linguistic and cultural context on conceptual representations. We also promote the use of interactive methods to investigate both the comprehension and production of abstract concepts, while also focusing on individual differences in conceptual representations. Overall, we argue that abstract concepts should be studied in a more nuanced way that takes into account their complexity and diversity, which should permit us a fuller, more holistic understanding of abstract cognition.

Abstract concepts are currently a topic of great interest in a variety of disciplines, including cognitive science, linguistics, psychology, cognitive, social, and affective neuroscience, and philosophy. Theories are now converging on a broader framework for the study of their nature, representation, and use, with novel methods beginning to appear alongside more traditional ones. This paper brings together the views and latest work of several researchers in the field, providing a consensus on new theoretical and methodological advancements, and recommendations for future research.