Articles and Features

The Fear Of Art: Contemporary Art Censorship

By Adam Hencz

Tampered photographs, removed paintings, destroyed sculptures, detained artists, and silenced opinions. Censorship is the most common violation of artistic freedom. Contemporary art and artists are unduly censored due to their creative content, which is opposed by governments, political and religious groups, social media platforms, museums, or by private individuals. Artists and advocates of artistic freedom are often silenced for questioning social and religious norms or expressing political views that oppose dominant narratives. Even so, regardless of the censors’ rationale behind removing or oppressing art, their actions potentially justify its meaning even more.

Reality has always been, from the beginnings of artistic expression, an essential vehicle for creation. The depiction of what the eyes see, and what humans feel and think, is one of the main themes for art. Nevertheless, artistic production never solely replicated reality —even during Realism it had its purpose of showing the brutality or beauty of everyday life to viewers— and neither has art ever been just a personal reflection of an artist, unengaged from the world. Its interpretation is confounded within a web of contextual meanings, exposing it to vulnerability when forced into an artificial context.

Recent acts of art censorship in museums, against works or exhibitions from renowned artists, have been interpreted by many as proof of dangerous political correctness and total disregard of the value of the pieces. Works of artists from the 19th and 20th centuries were recently deemed offensive either by museums or the public and consequently removed from display. Among others, the Manchester Art Gallery took down John William Waterhouse’s painting Hylas and the Nymphs (1896) ; Egon Schiele’s centennial exhibition advertisements suffered censorship in London and Germany; and, on the occasion of the show Balthus: Cats and Girls – Paintings and Provocations , a petition was signed by many to convince New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art to control the way people look at Balhus’ Thérèse Dreaming (1938).

Museums were established to protect artistic freedom and defend the right of art to shock and unsettle and defend the right of the viewer to be unsettled. However, institutions also tend to censor works of art on political grounds and stimulate debates. The recent case of postponing Philip Guston ’s retrospect which was scheduled to be opened in 2020 shows clear implications for the involved museums. The reasons for the postponement had little to do with Guston’s work itself and much more to do with the institutions’ lack of faith in their curators and lack of belief in the intellect of the general public’s ability to navigate the subtleties of Guston’s oeuvre. The cancellation caused a backlash from the artistic community and locked the museum world in a heated debate over race, self-censorship, social justice, appropriation and ‘cancel culture’.

Governments

Dominant forms of political narratives polarise us around the world and leave no mercy to theaters, novelists, museums and musicians who find themselves under attack for being critical of the government and governing ideologies. Forms of nationalism – or religious nationalism – have been used in Poland and Hungary, but also in India, where governments institutionalised religious bodies play a growing role in determining what is deemed appropriate in the public space. This tendency adds to the growing global trend of underfunding culture to make it vulnerable. The appointment of unprepared and unprofessional persons in key cultural positions has thus become a systemic issue.

As the largest independent international organisation defending freedom of artistic expression Freemuse reports, the Turkish, Russian, and Chinese governments abuse counterterror laws against artists, who therefore face censorship, harassment, threats, or imprisonment, accused of being close to terrorist groups or because their artwork was interpreted as a threat to the nation. The case of Turkish artist and journalist Zehra Doğan sparked media attention from human rights advocacy groups and arts communities in 2017 when she was sentenced to two years and 10 months. She was jailed, together with her work as a journalist, for a painting depicting a town in the majority-Kurdish south-east of the country that was destroyed in a Turkish military operation in 2015.

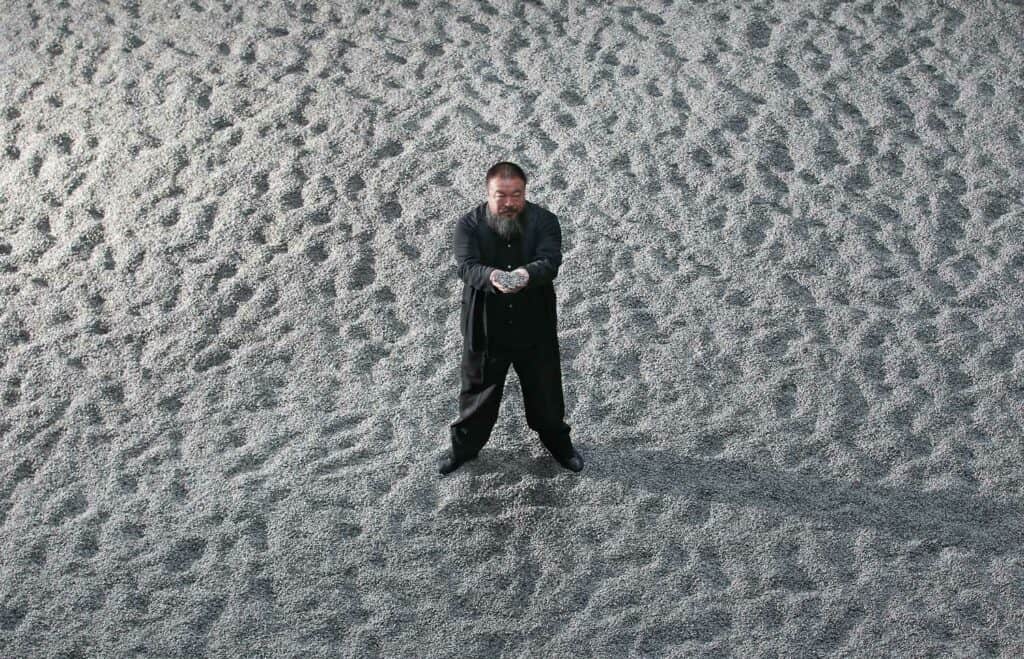

Ai Weiwei is an artist who today is known not only for his art and activism, but also his crusade against the Chinese government. Ai Weiwei uses his creative work as a vehicle to speak out against censorship, the gentrification of the art market, and to criticise China’s ruling government. In 2011 he was detained after police had searched his studio, confiscated computers, and questioned assistants. Shortly after his 81-day detention, followed by four years of de-facto house arrest, his studio in Shanghai was demolished. However, the demolition appeared to be a byproduct of Beijing’s latest urban development plans, even though it is still widely believed to be in retaliation for the artist’s criticism of the government. In 2014, days before the government-operated Power Station of Art in Shanghai was to stage an exhibition devoted to the winners of the Chinese Contemporary Art Award, officials in the city dropped his name from the artist list —removing his renowned work Sunflower Seeds from display— due to his outspoken criticism of systematic censorship.

“In the end, those who seek to censor and destroy art testify to its power, whether the work is seen as a symbol of something hated or disliked, or simply as a vessel of form.” David Freedberg

Every act of censorship is related to a larger pattern of pressure being brought against education, the press, film, and the freedom of speech. These efforts cast a shadow of fear on the public that leads to voluntary curtailment of expression by those who seek to avoid controversy and eventually fail to provide clues to the social use and function of images. However, it is key to keep David Freedberg’s words in mind during the clashes between artistic freedom and forms of silencing, that “in the end, those who seek to censor and destroy art, testify to its power —whether the work is seen as a symbol of something hated or disliked, or simply as a vessel of form”.

Relevant sources to learn more

Find more cases in Freemuse ‘s The state of artistic freedom reports Censorpedia : An Interactive Database of Art Censorship Incidents 10 Controversial Art Pieces That Shook the Art World

- Art Movements

Censorship in the Art World and Its Impact on Creativity

Related Posts

George Roux: Master Illustrator of ‘The Spirit’ and Beyond

The Art of Royalty: Analyzing the New Portrait of King Charles III & WHY IT’S ACTUALLY GOOD

Beyond instagram: discovering new platforms for creatives in the digital age.

Unveiling the Symbolism of Picasso’s Guernica: A Masterpiece of Protest

The freedom of expression, societal norm-challenging, and thought-provoking qualities of art have long been lauded. The complex problem of censorship, however, has caused the art world to struggle throughout history. The limits of artistic expression have frequently been met with limitations due to repressive regimes and cultural sensitivities. This blog post explores the hotly contested subject of censorship in the art world, looking at its historical background, effects on artists and society, and the ongoing discussion surrounding artistic freedom.

Censorship Through the Ages: A Historical Perspective

Throughout history, various civilizations and governing entities have tried to censor and restrict artistic expression, frequently using art to spread their ideologies and quell dissent. The act of censorship in the art world has evolved over time and has been motivated by a variety of factors in societies from antiquity to the present.

Old Civilizations:

In ancient civilizations like Egypt, Greece, and Rome, art was essential to religious rituals, mythological stories, and the celebration of kings and victories. But even in these primitive societies, censorship was present. For instance, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt frequently commanded the destruction or alteration of artworks that featured the likenesses of their forebears, erasing any memory of rivals or presumed adversaries.

Censorship of Religion:

The Catholic Church had strict rules regarding religious representation and exerted significant control over art throughout the Middle Ages. Some artistic representations were destroyed or kept secret by the Church because they were thought to be heretical or sacrilegious. For example, “The Last Judgement” by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel drew criticism for its naughtiness and suggestive imagery.

Governmental and Royal Censorship

To keep their hold on power during the Renaissance and Baroque eras, strong political leaders imposed censorship. Examples include the Spanish Inquisition, which forbade any artwork it deemed to be blasphemous or toeing non-Catholic lines of thought. Similar to this, in France, the Court of Louis XIV strictly regulated the creation of art, favouring opulent depictions of the monarchy while stifling dissenting opinions.

Totalitarian governments

Censorship was used by totalitarian governments to stifle opposition and manage public opinion in the 20th century. Avant-garde and modernist art was deemed “degenerate art” by the Nazi regime in Germany, and it was banned from museums in favour of state-approved works that praised Aryan ideals and extolled Nazi ideology. Similar to how socialist realism took over as the accepted art form in Soviet Russia, communist propaganda-aligned art was demanded and artistic innovation was suppressed.

Censorship in the modern era:

Censorship is still practised today in a number of ways. Some nations continue to firmly censor artistic expression, placing limitations on its political or religious content or its criticism of the authorities. Others, on the other hand, struggle with questions of cultural sensitivity and representation, which spark discussions about artistic intention and cultural appropriation.

The Struggle for Creative Liberty:

Despite the difficulties brought on by censorship, organisations, activists, and artists have been at the forefront of the fight for the freedom to express oneself creatively and without fear of retribution. The values of free expression in the arts have been supported by movements like the American Free Speech Movement and organisations like PEN International.

The historical background of censorship in the art world demonstrates the complex interplay between political ideology, power, and the right to free expression. Artists have consistently pushed the envelope, challenging repressive regimes and social norms, even as censorship has been used as a tool to control narratives and uphold authority. Understanding the historical struggles for artistic freedom motivates us to value and protect the freedom of expression of artists, fostering a vibrant and diverse artistic landscape that reflects the complexity and richness of the human experience. Fighting for artistic freedom is still a crucial tenet of a democratic and culturally enriched world as societies continue to change.

Institutional and Curatorial Functions

The narrative surrounding art is significantly shaped by art institutions, museums, and galleries. They must carefully navigate potential controversies while organising exhibitions that represent a range of viewpoints. We go over how choices about which artworks to display or keep hidden can be a reflection of societal norms, values, and even political pressures.

Cultural Awareness and Identity

Art must deal with a variety of cultural sensitivities and identity-related issues in a globalised world. Unintentionally offensive artwork may be produced by artists, which could result in calls for its removal or censorship. We investigate the tension between cultural sensitivity and the right to free speech, which sparks discussions about artistic intent and cultural appropriation.

The remarkable power of art to break down barriers, foster human connection, and honour the diversity of cultures is unmatched. But as art travels through various cultural contexts, it might run into sensitivity issues and identity-related problems that call for cautious navigating. Fostering inclusivity, empathy, and understanding within the art world requires striking a balance between the values of artistic freedom and respect for cultural context.

Acknowledging Cultural Diversity

The world of art has evolved into a melting pot of cultures, traditions, and identities in today’s globalised society. By embracing this diversity, we can challenge the homogeneity of artistic narratives and enrich artistic expressions. Art institutions can promote intercultural understanding and celebrate the beauty of human creativity in its many forms by showcasing a wide variety of artists from various cultural backgrounds.

Honouring Cultural Traditions

The histories, ideologies, and symbols that are deeply ingrained in a particular cultural tradition are carried by the artwork. It is crucial to respect the cultural sensitivities and values these artworks represent when presenting them and to contextualise them appropriately. This necessitates careful curation choices and interpretive resources that provide information on the historical and cultural significance of the art.

Awareness of Cultural Appropriation:

When cultural components are adopted or used outside of their original context, frequently without adequate understanding or respect for their cultural significance, this is known as cultural appropriation. Artists need to be aware of this problem and handle subjects with decency and humility. It shows a commitment to ethical artistic practises to acknowledge sources of inspiration, participate in cultural exchange, and ask for permission when required.

Making Underrepresented Voices Heard:

For underrepresented communities, art can provide a potent platform for identity expression and stereotype-busting. When it comes to amplifying these voices, giving marginalised artists a platform, and making sure their stories are heard and recognised, art institutions are crucial. A more diverse and equitable art world benefits from exhibitions and collections that feature these artists.

The Power of Art to Promote Empathy

The unique capacity of art to arouse feelings and promote empathy. A deeper understanding of various cultures and identities can be gained by audiences by showcasing art that depicts diverse experiences, struggles, and triumphs. Through its ability to bring people together, art can foster intercultural communication and respect.

Collaboration and Dialogue:

Encouragement of intercultural communication and cooperation promotes a fruitful exchange of thoughts and viewpoints. In order to explore shared themes, exchange artistic methods, and collaborate on original projects, artists from various cultural backgrounds can come together. These interactions foster learning from one another, enrich artistic expression, and dispel stereotypes.

Community involvement and art education

Future generations’ perspectives on cultural sensitivity and identity are greatly influenced by art education. It fosters an appreciation for cultural diversity and promotes respectful engagement with art when teachers expose students to a variety of art forms, cultural histories, and artists from around the world.

The art world faces both opportunities and challenges as a result of cultural sensitivity and identity-related issues. A culture that celebrates cultural diversity and acknowledges the unifying power of art can be fostered by artists and art institutions by placing a high priority on inclusivity, respect, and empathy. A dedication to openness, knowledge, and ongoing conversation is necessary to navigate cultural sensitivities thoughtfully. The art world can unite society by celebrating the common humanity of people from all backgrounds by embracing diverse voices and experiences. A world that values and learns from its rich cultural tapestry can be created by fostering a culture of inclusivity and empathy, which ultimately enables art to realise its potential as a transformative force.

Dissent and Political Censorship

The ability of art to critique society and promote change has long made it a potent tool for political dissent. Nevertheless, oppressive regimes frequently stifle such expressions out of concern that art might incite the populace against them. We examine the effects of political censorship on creative expression and the fortitude of artists who opt to oppose oppressive systems.

Internal Conflict: Self-Censorship

Artists might self-censor their work in order to conform to social norms out of fear of criticism or persecution. We look at the internal conflict that artists experience as they attempt to strike a balance between their artistic visions and the need to keep their careers intact or avoid controversies.

Digital censorship on the Internet

With the development of the internet, new difficulties with censorship have arisen. Online platforms must make difficult choices about how to moderate content, frequently straddling the line between allowing for freedom of expression and removing offensive or harmful material. We investigate how digital censorship affects the spread of online artistic communities and the accessibility of art.

Fighting for Creative Freedom

The right to artistic freedom gives people the freedom to express their thoughts, feelings, and worldviews without worrying about censorship or retaliation. Artists and activists have passionately fought for artistic freedom throughout history, upholding the notion that it is essential for society to advance, to foster critical thinking, and to challenge the status quo. The struggle for artistic freedom has many facets, all of which support the protection of originality and the appreciation of various artistic viewpoints.

In support of freedom of expression:

Promoting freedom of expression has long been a priority for artists. Works of art have been effective vehicles for social criticism, political dissent, and challenging accepted norms. In repressive regimes, artists took a life-or-death stand against oppressive authorities and spoke out for the needs of marginalised groups. Their unwavering commitment to exercising their right to free expression has sparked reform movements and motivated others to take up the cause of artistic freedom.

In opposition to Censorship and Oppression:

Artists have resolutely carried on with their work despite censorship, pushing the envelope and ignoring limitations. Periods of artistic repression gave rise to many iconic works of art, highlighting the tenacity and bravery of creators in their struggle against censorship. Picasso’s “Guernica,” produced in response to the atrocities of war and oppression, is proof of the ability of art to fight injustice.

assisting at-risk artists

International organisations and other artists frequently lend support to artists who are subjected to oppressive regimes or who are threatened with harm. In addition to offering legal assistance, facilitating safe havens, and bringing attention to these artists’ plight, advocacy organisations like PEN America and Freemuse tirelessly work to defend artists who are in danger. The right of artists to create without fear is a cause for which the entire international art community is united in vigour.

Internet activism

The digital era has created more opportunities for artistic activism. By distributing their works online and through social media, artists are able to reach a global audience while avoiding censorship. Digital art also gives creators the freedom to disagree and participate in public discourse without being constrained by traditional media.

Boosting Legal Protections

Different nations have different laws defending artistic freedom, with some providing strong protections and others having repressive laws restricting free expression. By promoting legislation that defends artistic freedom and opposes restrictive regulations, artists and activists fight to strengthen legal protections. With these initiatives, we hope to foster an atmosphere that encourages artistic expression without fear of retribution.

Making Spaces for Expression Safe:

In order to foster artistic freedom, art institutions and organisations are essential. These organisations establish secure environments for creativity to flourish by organising exhibitions with a variety of viewpoints and themes, encouraging artists from underrepresented groups, and promoting discussions about censorship and artistic expression.

Fighting Self-Censorship

In addition to dangers from the outside world, artists may also experience internal pressures that cause self-censorship. Creative expression can be stifled by social pressure to fit in or by fear of backlash. In an effort to dispel these anxieties, artists and the art world support one another in urging creators to embrace their authenticity and freely express their distinctive viewpoints.

An ongoing struggle that cuts across national borders and cultural contexts is the fight for artistic freedom. A group of people dedicated to fostering dialogue, preserving creativity, and combating censorship includes artists, activists, and institutions of the arts. By valuing artistic freedom, we respect the ability of art to inspire, arouse thought, and spark constructive change. The struggle for artistic freedom is a declaration of the idea that the free expression of creativity is a fundamental human right and essential to the development of a thriving democracy. By maintaining this fight, we make sure that artists keep reshaping the world with their distinctive ideas, inspiring future generations and serving as a constant reminder of the unstoppable spirit of artistic expression.

In the world of art, censorship continues to be a contentious issue that pushes the limits of artistic freedom and forces societies to face uncomfortable truths. The battle for freedom of expression rages on even as political factors and cultural sensitivities influence the artistic landscape. Fostering open discourse, defending artistic freedom, and upholding the notion that art, in all its varied forms, is a potent catalyst for social progress and human understanding are essential as we negotiate the difficult terrain of censorship. We cannot fully comprehend the transformative power of art in reshaping the world we live in unless we embrace a wide variety of artistic voices and perspectives.

Oh hi there 👋 It’s nice to meet you.

Sign up to receive awesome content in your inbox from us.

We don’t spam!

Check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription.

How to Become Cultured in Art

All about untitled by eva hesse, creative flair.

Official Creative Flair Account

George Roux, a renowned French illustrator, left an indelible mark on the art world...

The unveiling of a new portrait of King Charles III has captured the attention...

For creatives who have relied on Instagram as their major platform for a long...

Pablo Picasso's "Guernica" is not just a painting; it is a profound political statement...

Most Popular

All Hidden Symbols & Meanings In Picasso’s Guernica

Rare Teenage Photos Surface of Banksy Before His Rise to Fame

Van Gogh’s “Starry Night”: Symbols, Techniques, and Impact

10 Optical Illusions In Famous Works Of Art

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Sign Up for our Newsletter

Drawing Exercises for Beginners

The Effects of Art and Culture on Todays Modern Society

Frieze New York 2024: A Fusion of Iconic and Emerging Art

Livestream Portal Reopens in Dublin and New York Following Lewd Behavior

Artist Joseph Awuah-Darko Accuses Kehinde Wiley of Sexual Assault

Billionaire Calls for Removal of ‘Unflattering’ Portrait from National Gallery of Australia

© 2024 Creative Flair Blog

Navigate Site

- Main Website

Welcome Back!

Login to your account below

Remember Me

Create New Account!

Fill the forms below to register

Retrieve your password

Please enter your username or email address to reset your password.

Are you sure want to unlock this post?

Are you sure want to cancel subscription.

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Censorship — Censorship of Art and Freedom of Expression

Censorship of Art and Freedom of Expression

- Categories: Art History Censorship

About this sample

Words: 1037 |

Published: May 19, 2020

Words: 1037 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Table of contents

A divide in the art world, the next wave, resonating loudly, works cited.

- Black, H. (2017). Letter to the curators of the Whitney Biennial. Retrieved from https://www.documentjournal.com/2017/03/hannah-black-letter-to-the-curators-of-the-whitney-biennial/

- Smith, R. (2017). Should art that infuriates be removed? Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/28/arts/design/should-art-that-infuriates-be-removed.html

- Viso, O. (2020). Decolonizing the art museum: The next wave. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/23/arts/design/museums-race-protests.html

- Walker, K. (2017). Instagram post. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/BSNZX1YAXiI/

- Banks, M. (Ed.). (2007). Controversies in Art: Artistic Freedom, Censorship, and Public Funding. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Bredekamp, H., & Diers, M. (Eds.). (2012). Art and Controversy: The Role of Art in Politics and Society. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter.

- Canaday, J. (2019). The Politics of Display: Museums, Science, Culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

- De Bolla, P. (2012). Art Matters: A Critical Commentary on Heidegger’s “The Origin of the Work of Art.” In P. de Bolla (Ed.), Art Matters: A Critical Commentary on Heidegger’s “The Origin of the Work of Art” (pp. 1-10). London, UK: University of Chicago Press.

- Meskimmon, M. (2013). Contemporary Art and the Cosmopolitan Imagination. London, UK: Routledge.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Arts & Culture Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 570 words

1 pages / 408 words

3 pages / 1296 words

3 pages / 1531 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Censorship

Censorship is a practice that has been used across many governmental systems throughout history. In the novel Fahrenheit 451, author Ray Bradbury explores the latent damages that arise when censorship is placed upon a society. [...]

Ray Bradbury paints a haunting picture of a society consumed by mindless entertainment, where books are banned and intellectual curiosity is stifled. Through his vivid portrayal of this futuristic world, Bradbury raises [...]

In conclusion, Fahrenheit 451 is a thought-provoking novel that explores the themes of censorship, the dangers of technology, and the importance of intellectual freedom. Through its cautionary tale, Ray Bradbury invites us to [...]

However, there has been a long-standing debate about whether certain books should be banned from public spaces, schools, and libraries due to their content. While it is important to acknowledge that some material may be [...]

“Everything faded into mist. The past was erased, the erasure was forgotten, the lie became truth.” This line, delivered in George Orwell’s sinister book, 1984, exemplifies a totalitarian government censoring information, [...]

While some argue that censorship can protect society from harmful ideas, Fahrenheit 451 presents a counterargument that censorship can create a society that is intellectually stagnant and vulnerable to manipulation. By [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

September 6, 2023

John William Waterhouse, Hylas and the Nymphs, 1896. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

By Esther Neville

Censorship in the art world has sparked enormous debate, as it navigates the delicate balance between freedom of expression and cultural sensitivities. Internationally, art has long served as a reflection of human expression and cultural evolution; however, the clash between creative freedom and societal norms often ends in contentious debates and prison challenges. This article analyzes recent cases of art censorship in various forms.

Many have viewed recent museum censorship actions against well-known artists’ works or shows as evidence of political correctness and with complete disregard for the merit of the artworks. [1] [1] Recently, works by 19 th and 20th-century painters were judged by institutions and were taken down from exhibitions.

For instance, the Manchester Art Gallery removed John William Waterhouse´s Hylas and the Nymphs (1896) due to its nudity and portrayal of an erotic Victorian fantasy. However, the Gallery´s purpose for this was to “prompt conversation;” they asked the audience about their opinion on how this artwork should be interpreted. [2] Visitors then read this commentary on notes, which were attached to the place formerly reserved for Waterhouse’s painting. [3]

Michelangelo´s David

Additionally, one of the most recent cases of censorship occurred last March 2023. Hope Carrasquilla, a former principal at Tallahassee Classical School in Florida, was fired for presenting Michelangelo’s David in her art class. [4] Several parents complained about the nudity of the sculpture and did not agree with presenting such artwork to their children. As a result, the former Tallahassee principal was forced to resign. Other examples of “controversial” artworks containing nude bodies shown in the Renaissance art class include The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo and Botticelli´s Birth of Venus . [5] According to the case, a letter should have been sent out to the parents detailing what was going to be shown in the classroom. Carrasquilla stated that she assumed the letter went out and didn’t follow up. Even though many parents defined the sculpture as “pornographic” and thus inappropriate, there were others who did not think so. Similarly, Florida´s Department of Education declared that the David sculpture has artistic and historical value. [6]

After the news of this Florida censorship case came out, many were outraged and shocked. In particular, Italian politicians complained about the incident. The country´s deputy premier Matteo Salvini stated in a tweet that “obscuring and erasing history, art, and culture for girls and boys is absolutely crazy and there is nothing correct about it.” [7] The Florence mayor Dario Nardella also took it a step further and invited Carrasquilla to Florence to give her recognition. The Director of the Galleria dell´Accademia Cecilie Hollberg gave the teacher a tour around the gallery, as well, so she could admire and see the sculpture in real life. Hollberg later stated, “To think that David could be pornographic means truly not understanding the contents of the Bible, not understanding Western culture, and not understanding Renaissance art.” [8]

This dismissal raised the question of the depiction of nudity in artwork and whether it has instructional relevance and also demonstrated the implications of censorship in art schooling. [9] This makes us wonder what the limits on censorship are. Most of the classical sculptures that portray topics like history and myths have some sort of nudity. Will this part of history be erased and forgotten?

The Prophet Muhammad

Nudity in art is not the only theme facing censorship. Another case of censorship of artworks in the educational system occurred at Hamline University, a private liberal arts college in St. Paul. In 2022, a professor was terminated for showing several artworks depicting the Prophet Muhammad in an art history class. [10] The controversial dismissal stemmed from non-secular sensitivities, with opponents arguing that such depictions were blasphemous and offensive. The First Amendment of the American Constitution protects freedom of expression, however, it also recognizes that positive speech might also incite harm or disrupt societal concord. [11]

This case has raised important questions about censorship within the art world and the principle of academic freedom. While using such an image can have pedagogical value in certain courses, displaying an image of Muhammad can be deeply offensive to many individuals for religious reasons. [12] By firing the professor, Hamline University disregarded the mandate from the Higher Learning Commission, which requires accredited institutions to uphold academic freedom. [13] The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) expressed concerns about this incident, they called for the professor’s reinstatement and have filed a formal complaint with Hamline’s accrediting body, citing the college’s failure to support faculty in their pursuit of educational freedom. [14] Many of the supporters of the professor argue that labelling the depiction as Islamophobic is inaccurate and diverts attention from genuine instances of hatred. They contend that the university’s response to the incident, which appears to prioritize appeasing a minority organization over defending academic freedom, has led to significant grievances within the community. This situation underscores the ongoing debate over how to balance academic freedom with sensitivity to religious beliefs and cultural sensitivities, posing a challenge for institutions of higher learning.

This incident prompts us to contemplate a series of important questions within the context of a liberal arts community. Specifically, it raises inquiries regarding the appropriateness of engaging in a comprehensive examination of certain subjects and whether a professor of art history should feel comfortable sharing substantial artworks with students without concerns about potential consequences, such as termination, stemming from objections raised by other students or external parties. Furthermore, it is crucial to mention that many of the artworks that were shown in this situation were created by Muslim artists with the explicit intention of resonating with a Muslim audience. These artistic expressions were born out of a deep sense of admiration and reverence for figures such as Muhammad and the Quran; they were not intended to be provocative or offensive in any way. However, what is notable is the stark contrast between this artistic intent and the characterization of these depictions by certain Hamline administrators; as they have labelled these Islamic portrayals of Muhammad as exhibiting traits of hate, intolerance, and Islamophobia, raising the question of whether this interpretation aligns with the intended message of the artists and the principles of academic freedom that liberal arts institutions hold dear. This juxtaposition of artistic intent and administrative perspective underscores the complexity of navigating sensitive cultural and religious subjects in an educational setting. [15]

All of these cases show us how critical their historical context is when comparing the legality of such censorship. Many artistic endeavours throughout history, especially from the Renaissance period, consist of nudity. Censoring those portions risks erasing an integral part of artwork records. Courts may not forget whether the paintings’ nudity serves a valid creative or instructional reason, and whether or not it qualifies as obscenity beneath the regulation. Additionally, institutions can be pressured to balance cultural sensitivities and the necessity of offering art in its ancient and inventive context.

Censorship inside the art world presents complicated demanding situations, intersecting with First Amendment rights, educational freedom, cultural sensitivity, and historical renovation. In both instances examined, courts ought to examine the quantity to which creative expression aligns with societal norms and values. It is vital to shield the academic cost of artwork, even if it every now and then conflicts with installed norms.

These cases underscore the necessity of open communication between instructional establishments, college students, artists, and groups. The regulation needs to provide a framework that encourages discussion and debate while respecting diverse perspectives. By doing so, we are able to ensure that art, as a reflection of human creativity and cultural evolution, enhances our society without compromising the essential concepts of freedom and respect.

Disclaimer: This and all articles are intended as general information, not legal advice, and offer no substitution for seeking representation.

About the author

Esther Neville (Summer 2023 legal intern at the Center for Art Law) is finishing her European Law Bachelor at Maastricht University, with a minor in Art, Law and Policy Making. She wishes to combine her academics with her passion for the arts. She works on the Anti-Money Laundering Study Project at the Center.

Further Reading

- Gareth Harris, “Trigger Warning: a new column on censorship in art today, from must-read books to which algorithms are policing creative content,” The Art Newspaper (Sept. 5, 2022), available at https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/09/05/an-experts-guide-to-censorship-four-must-read-books

- “Is art censorship on the rise? How freedom of expression is being curbed across the globe” The Art Newspaper (Sept. 9, 2022), https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/09/09/is-art-censorship-on-the-rise-how-freedom-of-expression-is-being-curbed-across-the-globe

- Kelly Grovier, “Michelangelo’s David and 10 artworks that caused a scandal,” BBC (Mar. 27, 2023), https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20171018-the-works-too-scandalous-for-display

Bibliography

- Hencz, The Fear of Art: Contemporary Art Censorship, Artland Magazine (2023), https://magazine.artland.com/the-fear-of-art-contemporary-art-censorship/ ↑

- Brown, Gallery removes naked nymphs painting to “prompt conversation”, The Guardian (2018) https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/jan/31/manchester-art-gallery-removes-waterhouse-naked-nymphs-painting-prompt-conversation ↑

- Millership, This Artwork Changed My Life: John William Waterhouse´s “Hylas and the Nymphs” , Artsy (2020), https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-artwork-changed-life-john-william-waterhouses-hylas-nymphs ↑

- Whiddington, The Florida Principal Fired for Allowing a Lesson on Michelangelo’s ‘David’ Went to Italy to See the Sculpture Herself—and Was Rather Impressed, Artnet News (2023), https://news.artnet.com/art-world/fired-florida-principal-visited-michelangelo-david-2292636 ↑

- Cascone, Florida’s Department of Education Declares ‘David’ a Work of ‘Artistic Value’ After a Principal Was Fired Over a Lesson Showing the Nude, Artnet News (2023)https://news.artnet.com/art-world/florida-department-of-education-declares-david-art-not-porn-2280637 ↑

- Wanted in Rome, Florida school principal fired for showing students Michelangelo´s David, (2023)https://www.wantedinrome.com/news/florida-school-principal-fired-michelangelo-david.html ↑

- Mueller, Italian mayor defends Florida principal forced out over ‘David’ statue, The Hill (2023)https://thehill.com/homenews/3919221-italian-mayor-defends-florida-principal-forced-out-over-david-statue/ ↑

- Kim, A Florida principal who was fired after showing students ‘David’ is welcomed in Italy, NPR (2023) https://www.npr.org/2023/05/01/1173017248/florida-principal-david-michelangelo-visit-italy ↑

- Lawson- Tancred, Muslim Group Urges the Reinstatement of Fired U.S. Professor, Saying the Prophet Muhammad Painting She Showed to Students Was Not Islamophobic, ArtNet News (2023)https://news.artnet.com/art-world/fired-professor-hamline-not-islamophobic-2241214 ↑

- NY Times, A Lecturer Showed a Painting of the Prophet Muhammad. She Lost Her Job, (2023) https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/08/us/hamline-university-islam-prophet-muhammad.html ↑

- Cascone, A Minnesota University Is Under Fire for Dismissing an Art History Professor Who Showed Medieval Paintings of the Prophet Muhammad, ArtNet News, (2023) https://news.artnet.com/art-world/professor-terminated-art-history-paintings-muhammad-2238922#:~:text=In%20a%20controversial%20move%2C%20an,founder%20of%20the%20Islamic%20religion . ↑

- Higher Learning Commission, HLC Policy, Policy Title: Criteria for Accreditation, Number: CRRT.B.10.010,(1992) ↑

- Fire, FIRE files accreditor complaint over Minnesota art history professor fired for showing Muhammad painting, (2023)https://www.thefire.org/news/fire-files-accreditor-complaint-over-minnesota-art-history-professor-fired-showing-muhammad ↑

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not meant to provide legal advice. Readers should not construe or rely on any comment or statement in this article as legal advice. For legal advice, readers should seek an attorney.

Related Posts

Deciphering the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act and its Effects on Reclaiming Looted Art

Color Blocking: How to Protect A Color

Secrecy in Museums Administration

Become a member.

Since 2009, the Center for Art Law has organized hundreds of events and published over 1,200 relevant, accessible, and editorially independent articles. As a nonprofit working with artists and students, the Center for Art Law relies on your support to fund our work. Become a premium subscriber and gain access to discounts on events and archives of articles and/or hundreds of case summaries, intended for a worldwide audience of legal professionals, artists, researchers, and students

Thaler v. Perlmutter, Civil Action No. 22-1564 (BAH) (D.C. Aug. 18, 2023).

Case Law Corner

Read case law summaries and enjoy unlimited access to our legendary Case Law Corner, now in a new and improved Database with over 500 entries.

Annual Subscription

- Access to all articles and past-event recordings

- Access to Case Law Database

- Free and discounted access to events

- Discounts to third-party events

Artist & Student Membership

- Access to our Case Law Database

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Trigger Warning: a new column on censorship in art today, from must-read books to which algorithms are policing creative content

Our chief contributing editor gareth harris will examine attacks on freedom of artistic expression and issues like ‘cancel culture’, providing valuable insights and context.

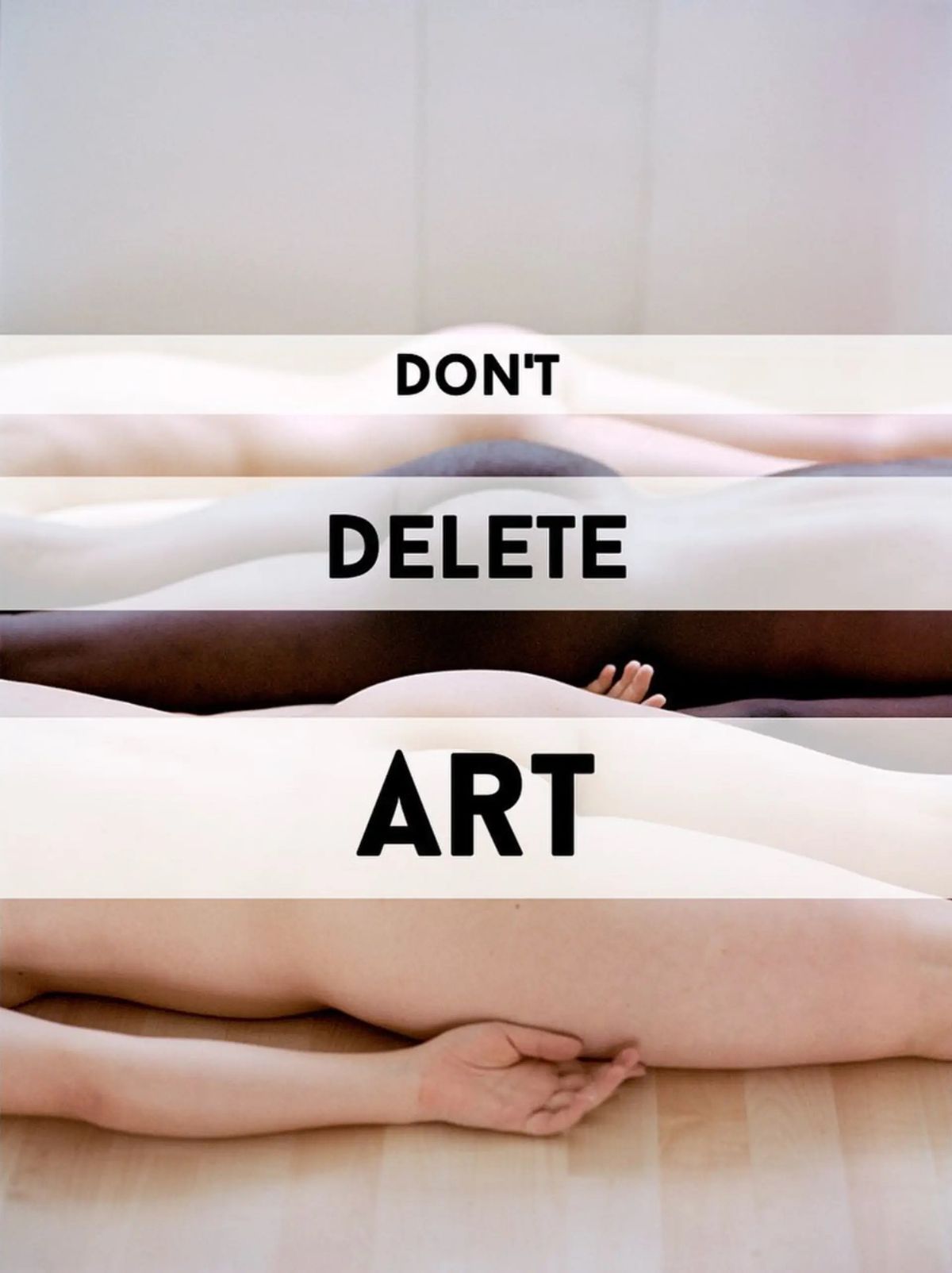

Image from the Don't Delete Art campaign instagram account @dontdelete.art

Original photograph by AdeY, altered for the Don't Delete Art campaign

In this bi-monthly blog, our chief contributing editor Gareth Harris examines cases of censorship worldwide, focusing on who the censors are and why they are clamping down on forms of artistic expression.

I write in my book, Censored Art Today: “We are in a new age of suppression with censorship on the rise in many different forms." Censored Art Today focuses on “the new age of censorship”. Art censorship is a centuries-old issue. But how and why freedom of expression is under threat has taken on extra resonance in the 21st century.

“Artists, museums and historic statues are, to use the contemporary term, being ‘cancelled’ in an ongoing critical debate around their status and value. The perfect storm of a pandemic, the advancement of anti-intellectual populist governments worldwide and uprisings against discrimination and inequality such as Black Lives Matter have brought about a reset of perspectives and principles,” I write in the publication.

Along with the book I am launching the bi-monthly blog Trigger Warning, which will examine censorship cases worldwide, focusing on who the censors are and why they are clamping down on forms of artistic expression. The aim is to drill down on censorship episodes, analysing the implications for artists and the art world, and how such cases inform the debate around issues that dominate contemporary discourse.

The divide between "woke" and "anti-woke" factions is, for instance, not lessening but intensifying; this ideological chasm is complex and shifting but the fallout of censorship is often ignored (not anymore). In the course of my blog journey, I want to look at the different contexts in which artists, museums and curators face restrictions today, focusing on hot topics such as the algorithms policing art online and the narratives around problematic monuments. Unpicking the new “culture wars” is challenging but necessary.

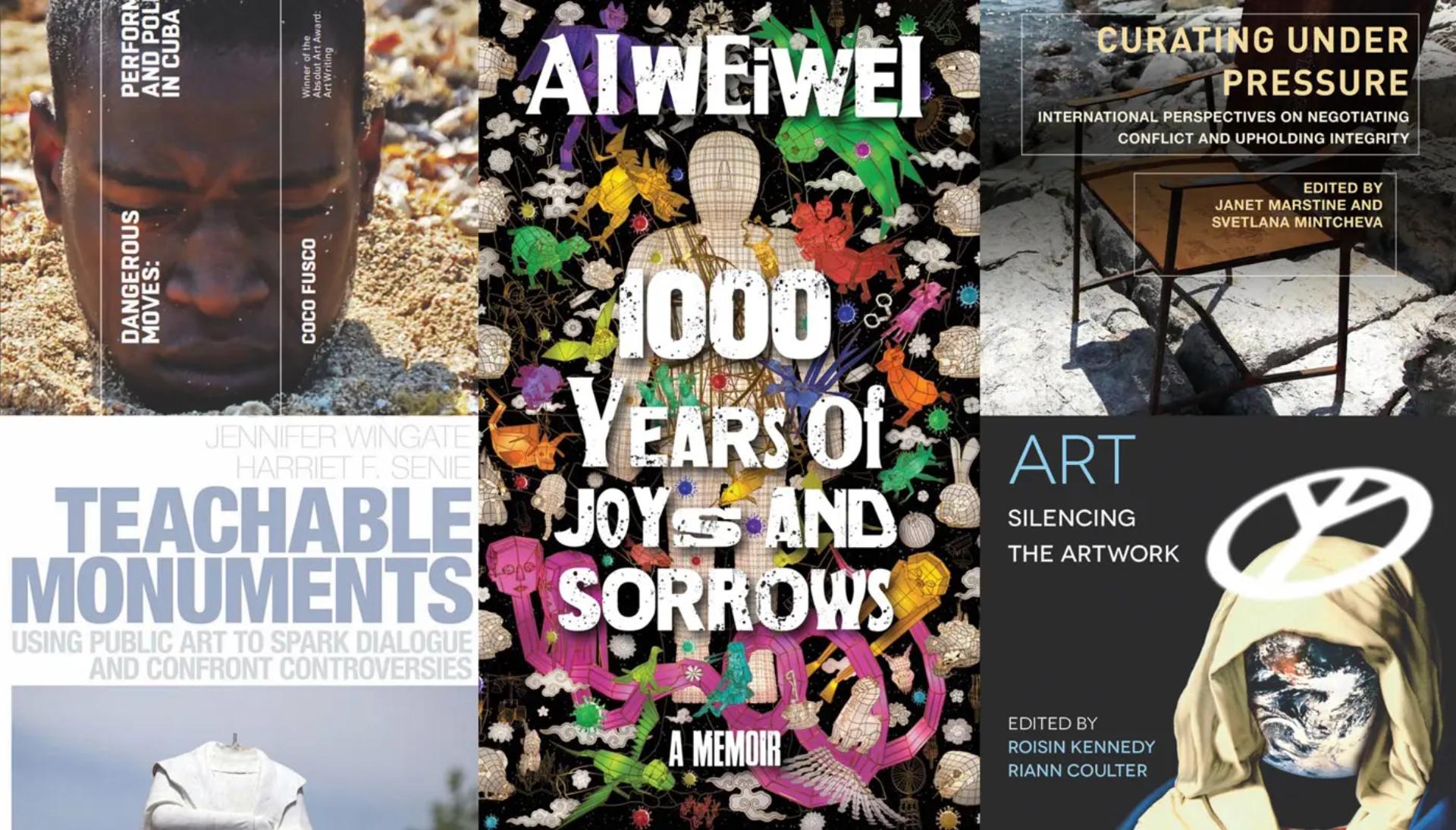

As a preamble, please see below five must-read books on art and censorship that helped with my research and crucially are shaping the conversation on who is censoring who today.

Curating Under Pressure: International Perspectives on Negotiating Conflict and Upholding Integrity (2020), edited by Janet Marstine and Svetlana Mintcheva

“This insightful volume looks at the pressures on curators worldwide to self censor and how arts professionals are finding ways to operate under oppressive regimes. Janet Marstine highlights, for instance, how ‘practitioners in China and Hong Kong have developed a diverse toolkit of strategies and tactics to resist censorship and self-censorship’, including using coded language—such as ingenious euphemisms, memes and homophones—to evade detection.”

Teachable Monuments: Using Public Art to Spark Dialogue and Confront Controversy (2021, pictured above), edited by Harriet Senie, Sierra Rooney and Jennifer Wingate

“This guide for teachers and arts administrators presents a wealth of information about ‘problematic’ public statuary, acting as a springboard for discussions around Confederate monuments and landmarks in the US. Plain-speaking essays and case studies demonstrate how monuments can be used to deepen civic and historical engagement and social dialogue. Wingate told the Public Art Dialogue journal that ‘more and more, the removals or the conversations around removals are the teachable moments. It’s important to keep the conversations going, because taking monuments down doesn’t solve the problems they embody’.”

The censorship books featured in the ultimate reading list

Dangerous Moves: Performance and Politics in Cuba (2015, pictured above) by Coco Fusco

“Coco Fusco, an expert on post-revolutionary Cuba, considers how artists such as Angel Delgado and Sandra Ceballos, and collectives such as Omni Zona Franca, have developed their politically engaged practices in the authoritarian state. Her study highlights two key periods of upheaval in Cuba: the late 1980s, when performance art was gaining in popularity, and the early 2000s, when the genre re-emerged as an unofficial subculture.”

Ai Weiwei: 1,000 Years of Joys and Sorrows, A Memoir (2021) by Ai Weiwei

“The Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei brings extra resonance to any discussion on art censorship; in 2011, he was detained by the Chinese government for 81 days without any formal charges, an experience that shaped his artistic vision. ‘For me, inspiration comes from resistance—without that, my efforts would be fruitless,’ he writes. Speaking to me for my book, he warned that ‘the mainstream media and entertainment industry in the West are under the influence of corporations and large enterprises. Corporatocracy is very often stronger than authoritarianism of any state because it is multinational.’”

Censoring Art: Silencing the Artwork (2018), edited by Riann Coulter and Roísín Kennedy

“The scale of Riann Coulter and Roísín Kennedy’s study is impressive, focusing on the mechanisms of art censorship across distinct geopolitical and cultural contexts, from Iran, Japan, and Uzbekistan to Ireland, Canada, Macedonia, and Soviet Russia. Essays from a variety of scholars cover topics such as art and censorship in Stalin’s Russia and contemporary art created in Macedonia in the shadow of Alexander the Great. The editors write that ‘exposing its mechanism [censorship] enables us to have a greater understanding of the conflicting frameworks in which the artwork functions.’”

• Censored Art Today: Hot Topics in the Art World , Gareth Harris, Lund Humphries and Sotheby's Institute of Art, 104pp, £19.99 (hb)

Gareth Harris is the author of Censored Art Today (Lund Humphries/Sotheby’s Institute of Art, 2022, available in the UK and US). He is chief contributing editor at The Art Newspaper where he has covered censorship stories and issues for more than two decades. His next publication focuses on art-world ethics.

Metacritic Journal

For comparative studies and theory, arguing for art, debating censorship, liviu malița.

Recommended Citation: Malița, Liviu. “Arguing for Art, Debating Censorship.” Metacritic Journal for Comparative Studies and Theory 5.1 (2019): https://doi.org/10.24193/mjcst.2019.7.01

While the debate about the legitimacy of censorship or about its social and moral usefulness is rather old, decisive conclusions are yet to be reached. Art is a sensitive area of inquiry since there is a belief that only art should be exempted from censorship. It is necessary to distinguish between freedom of expression per se (which is a guaranteed fundamental right) and artistic freedom. Regarding the former, limitations are necessary to protect the dignity of the person and his fundamental rights, 1 as well as to combat attitudes that are perceived as forms of “hate speech” (Frederick 86), but they may also be essential for ensuring fair competition rights. However, these limitations (which have their justification in the field of existence) “cannot be extrapolated along with the same prohibitions and the same penalties to works of art” (Huberman, qtd. in Burnet 44).

The very fictional character of art cancels out this transfer, by way of transfiguration. In an interview given during the “One World Romania” International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival (2012), Alexei Plutser-Sarno (a member of the Russian Voina group, an “anarchist punk-rock artistic movement”) stated that “between art and challenge, between art and crime, there are neither borders, nor any other types of interaction. They are situated in different planes, in worlds that never intersect.” 2 The idea that censorship cannot be applied to art belongs to a tradition that goes back to Aristotle (Sapiro 108). The work of art has a different ontological classification than the real fact; therefore, a different legal classification is required. Art is fictional, so it is “beyond good and evil.” Artworks must be removed from the jurisdiction of law courts because they are legally unclassifiable. Even among those who concede that art must be subjected to some form of control there are many who assert that literary works, for example, should not be treated with the same severity as political, moral or scientific writings.

Art and Justice

Several arguments converge to show that justice is not qualified to judge artistic offences.

1.1. The Conservatism of Justice

The myopia of justice is explained by the conservative principle of law, in comparison with the innovative dimension of art. It is difficult, if not impossible (given the inertia of the system and the slow pace of the legal apparatus) for the dynamics of artistic transformations to be promptly reflected in the legislation. The legal act therefore tends to be lagging behind artistic phenomena. Incriminated works are often judged according to definitions belonging to an earlier stage of art. 3 Such definitions are ineffective for assessing contemporary productions, which are always the subject of dispute. Often, in the case of inaugural works, what irritates and may cause rejection is the violation of artistic conventions rather than the transgression of moral norms. The risk to which a judge may be exposed is to make the unfortunate mistake of confusing morally offensive productions with artistic works that are deemed to be outrageous on account of their transgression against the frameworks of perception and the rules of artistic representation (Sapiro 295). The lack of synchronization (between the body of laws and the legal doctrine, on the one hand, and the social and artistic mutations of the present, on the other) threatens to delegitimize punishment, taking into account the fact that, in time, the boundaries of permissiveness have kept being pushed. The facts reveal the conservative character of censorship as opposed to the experimental character of contemporary art. The purpose of censorship is to strengthen cultural taboos (Willis 58, qtd. in Jacobsen 2) and to preserve traditional artistic values by discrediting modernist trends. Ultimately, under the utopian pretext of preserving morality intact, censorship leads, in fact, to the asphyxiation of the cultural space. Judging works of art and condemning the artists may paradoxically entail a situation where moral caveats become aesthetic shackles that block creation.

2. The judge’s artistic incompetence

A judge lacks the necessary authority to evaluate art. He does not condemn, as it is claimed, professions of immoral faith, but opts between various opposing morals (e.g. surrealist morality vs. bourgeois morality); because of his insufficient artistic training, the judge risks levelling artworks down when assessing them (Brochier 67). Legal conservatism often goes hand in hand with artistic mediocrity.

The “symbolically unlimited” nature of the work of art (to use a phrase belonging to Tudor Vianu) complicates matters. Thus, if we take the case of literature, the accusations that have been levelled against it have sparked a public debate on the interpretation of texts. Traditionally, justice has chosen (when deemed necessary) to condemn literary works for content-related issues. Gradually, the instability of meaning and the fundamental ambiguity of literary texts led, however, to querying not only the content, but also the form of discourse, the literary genre, the style and those components considered to epitomize the artistic personality of writers and their authorial intentions. 4 At the same time, the judges’ literary incompetence became obvious (compromising the authority of their decisions), and their opinions came to be seen as the opinions of non-experts on aesthetic matters.

Surely, a judge can appeal to the institution of expert witnesses (artists, art critics). However, this procedure poses a twofold inconvenience. The first (perfectible) consists in the manner of making the selection. The second (fundamental) refers to the fact that proper expertise is difficult to obtain. It is usually the case that artistically innovative works end up in court, works that are contested in their own field of origin, since it takes time for their innovative contribution to be comprehended and for such works to forge a pathway in their own (artistic) domain. As a result, expert witnesses can contradict one another, depending on the artistic ideology they uphold. 5

There are, of course, exceptions which may prove the aesthetic acuity of judges. A possible example is provided by the way in which a complaint against the poster of the film Amen by Costa-Gavras (2002) was settled in court. The poster is “a parodic composition, depicting a red cross that is highlighted against a dark background, extending along three sides in the shape of a hooked cross.” “Thanks to a skilful graphic game,” the poster denounced the Vatican’s role in the Second World War, “uniting the Christian cross and the hooked cross into one symbol.” Catholic bishops protested against the “unacceptable assimilation” and intolerable identification of the symbol of Christian faith with Nazi barbarity. The judge, however, did not settle the case in the bishops’ favour, considering that the author (Oliviero Toscani) could not be penalized. The president of the court rejected this “close reading” and deciphered in the incriminated image “the will to break down the Nazi cross, a symbol of totalitarianism, and to replant in the ground, as if to rehumanize it, the cross that every community continues to bear.” In the reasoning, the judge argued that “the swastika is incomplete, one arm being slanted downwards...” (Saint-Martin 66-69). Even multiplied, however, such examples do not constitute sufficient legal justification. On the contrary, they attest to the fact that it is always likely that the decision to ban a work of art may reflect the judge’s subjective preferences and aversions and not the intersubjective views of public opinion. The exceptions actually shed light on the kind of social role that the judge performs as a defender of the status quo , which is constantly contested by artists.

It has therefore been concluded that it would be ridiculous for the aesthetic value of an artwork to be discussed in court. 6 Artists themselves have been concerned to delegitimize such an approach. As for the justice system, it has compromised itself by reaching questionable decisions and by condemning several great artists throughout history.

3. The burden of proof concerning the harmfulness of art

It is, in fact, really difficult to produce the legal evidence that will prove (alleged) artistic offences, which are converted, by association, into non-artistic offences, as a rule. André Glucksmann believes that, as far as art is concerned, justice has failed to develop a “code of social threats” (Glucksmann 80). If it can be said to even exist, the harmful content of art is difficult to prove, so the driving force of censorship is not a certainty, but an anxiety, whose cultural perception is the “fear of representations” (Goady, qtd. in Glucksmann 76). The procedure, therefore, is exactly the opposite: first it resorts to exclusion (in order to protect) and only then is the “dangerous” nature of the censored content invoked, a content that is not so much the cause of the interdiction as its consequence. The very exclusion operated by censorship grants a work of art this “dangerous” character (sometimes abusively). The most common accusations against art are, therefore, those of immorality (pornography, obscenity), of “attacks against good morals” or of inciting violence, hatred, and racism. All three categories present controversial aspects.

(i) Art and pornography

The encounter between art and pornography is epistemically explosive (as it takes place between two “open” concepts, each likely to generate controversy) and is considered to be, according to legal norms, morally culpable. The question is whether it is rigorously possible to avoid this encounter. By systematizing the huge bibliography on this subject, Hans Maes inventories the main opinions expressed on this topic. The most prominent, first voiced by Peter Webb (1975) and frequently resumed afterwards, states that the dividing line between art and pornography is clear to the point of incompatibility. 7 There are also some classic ways to mark that difference. 8 However, the problem is that there are some generic differences which are difficult to prove in practice, where the situation is ambivalent. In any case, Maes contends, these dichotomies operated between some prototypical examples “will not serve to justify the claim that art and pornography are mutually exclusive.” A second sample, opposed to the first one, consists of theories which, taking note of the frequent violations of territory from both sides, argue either that pornography should be dissociated from obscenity, suggesting that only obscenity is incompatible with art (Huer; Mey; Graham), 9 or that pornography has an aesthetic dimension. 10 In any case, the differences are often minimal (quasi-imperceptible), generating errors. In the fine arts or in theatre and film, regrettable confusion has often been made between artistic nudity and pornography, for example. The works of writers like Flaubert, Byron or Baudelaire were condemned, in their own time, because of a blindness defined as ridiculous by posterity. Finally, to eliminate conceptual obscurity, it is recommended that one should consistently use the term “erotic” to denote the presence of sexual/sensual elements that are artistically transfigured in works of art.

Avoiding to let myself enmeshed in ever more refined conceptual distinctions, I will resume the conclusion reached by Maes, according to whom the best argument that the notion of “pornographic art” is not oxymoronic, but designates a legitimate artistic category is the very existence of pornographic artworks. His examples include Pauline Réage’s novel Histoire d’O , Nagisa Ôshima ‘s film In the Realm of the Senses , Kitagawa Utamaro’s woodblock print Woman with man with black cloth and food service , or Mapplethorpe’s photograph Jim and Tom, Sausalito . 11 If we continue to trace the line of demarcation between art and pornography with the firmness demanded by some theorists, many of the works of unquestionable artistic merit, Maes concludes, are on the “wrong” side (Maes, Drawing 4). Despite this argument, however, the suspicion remains that a work can be genuine both as art and as pornography, 12 thus rendering the whole process as a circular one.

The sheer scale of theoretical debates on this issue reveals the difficulties of deciding in court on the pornographic/obscene character of a work and of providing a credible reasoning for the penalties applied. Achieving a hypothetical consensus does not close the file. There are radical interrogations of the socially dangerous and morally degrading nature of pornography 13 and of the legitimacy of the government to ban its citizens from publishing and/or watching it. 14 The dispute is waged between the right to freedom of expression and, respectively, the right to dignity and identity (self-image). The former is a fundamental right and includes (in the context) the freedom of autonomous beings to pursue their own conception of development and to expand/diversify, through experimentation, their means of sexual gratification. 15 However, to the extent that pornography is considered harmful in emotional and relational terms, offensive and corrupting from a moral point of view, inducing libertinism, proposing role models that might deteriorate the self-image of people as social beings and partaking of “hate speech,” the right to free expression must be, in its case, (severely) restricted.

Even though, in life, pornography can be condemned (at least on account that it tends to corrode the organizational structures of society, attacking the core of the family and, by default, that of social cohesion), in art its harmful effect is, for many, unlikely. Symbolic transfiguration cancels it out.

In the case of literature, the situation is further complicated. Writings with explicit pornographic content (such as Sade’s novels) have a distinct philosophical character, which should protect them against censorship. They “not so much excite readers, as they fascinate intellectuals; hence, their weak erotic character” (Baudrillard 45). In addition, the accumulating effect of (perverse) sex sequences leads to a voidance of desire. The internal analysis of a literary work is not, however, necessarily conclusive. Often insufficient, it must be corroborated with contextualization. 16 In fact, contextualism is inherent to late modern aesthetics, according to which artistic status is not intrinsic, but relational and extrinsic to the work (see ready-made artefacts).

Regardless of the credibility of such arguments, the solution is not, one might think, that of banning these works. Such a measure can only limit access to those books, which will continue to circulate in clandestine forms, producing, sometimes, not only a more powerful impact (through the secondary effect of reverse advertisement), but also proposing a distorted reading of those texts, in the sense of strengthening their “pornographic” character. The hypothetical argument is that reading selectively (in the case of adolescents, for example) certain “debauched” fragments increases, by decontextualization, the degree of perversity of those scenes, if they are read exclusively through that lens. No matter how raw and, apparently, not transfigured artistically, such blameable fragments present in literary works have an altogether different significance by the very fact that they are not confined to themselves, but belong to a parabolic whole, which transcends them. Only within the context as a whole do they acquire aesthetic value and do they reveal their problematizing, ironic, visionary, etc. dimensions. The part is resignified because it belongs to a whole that is so radically different from it. Thus, by being embedded in a broader and infinitely more complex narrative structure, these fragments are absolved of their degrading status, no matter how crude the language might be. They benefit from a “system effect”. In other words, a great writer can afford the coarseness of a pornographer without becoming one himself.

(ii) The offence and the encroachment on morality

Indecency is an obscure offence 17 (the law does not define it precisely), undermined by a theoretical insufficiency. 18 It remains, however, the most common wrongdoing in the name of which artists and journalists have been prosecuted, despite the fact that the fictional status of art should absolve one from such liability. True art cannot corrupt: it has a rectifying rather than a corrupting role. Naturally, disputes also persist on this topic. 19

(iii) Incitement to violence

The relationship between art and violence is so old that it seems inextricable. The film industry has enhanced it exponentially. The aestheticization of violence becomes an actionable matter when there is a suspicion that the work of art incites to hatred and could lead to acts of violence. In this case, however, it cannot be demonstrated (as the law claims) that there is a direct causation between reading a book or watching a violent film and committing criminal acts. 20 The work of art is an inextricable mixture of reality and illusion, which we cannot translate tale quale into reality. The transition to action negates the artistic status of the work: art, Kenneth Clark claims, loses its true character when it incites to action (Clark, qtd. in Maes). It remains a subject of controversy whether art really augments violence (fuelling or expanding it) or whether it amounts (in Aristotelian terms) to a form of purgation, to an imaginary escape valve, which allows the release of the aggressive potential through a phantasmatic experience.

Like indecency, incitement to violence is an imprecise offence. This imprecision paves the way for abuse (Sapiro 97). Each of these is, Gisèle Sapiro notes, a vague and flexible formula used in the court of justice when one cannot be prosecuted for more precisely defined crimes (Sapiro 102). There are no arguments to uphold the accusation of an “attack on good morals” or “public morals,” only “the cry of an outraged conscience”: this article of the law is nothing more than a “weapon of society, used to defend itself from what it deems can hurt it” (Sapiro 101-102). Keeping them in the Criminal Code requires stricter rephrasing. To this point, however, the way to reach consensus on legal action against art remains insufficiently clarified. Nor is it clear where we draw the limit between the freedom of the judiciary and the non-democratic restriction of the freedom of expression of the person undergoing trial. Where exactly does the disagreement between them start?

4. The misdemeanour of opinion

Such crimes (pornography, incitement to violence, indecency) contain a blatant contradiction, which can discredit the very fight against them. At the same time, the distinction between a wrongdoing and a misdemeanour of opinion is among the tests that can tell the difference between liberal societies and totalitarian regimes. The post factum legitimation of prohibitions is built around the argument that they punish culpable acts, which represent an abuse of the right to free speech. Conversely, the severity of preventive censorship (the only one that, some people maintain, deserves this name!) derives from the fact that it penalizes a misdemeanour of opinion, considered culpable because it does not comply with the official viewpoint. 21 The legal issue of the misdemeanour of opinion continues to fuel the dilemma. 22

Literature is a limit-case, in which the two perspectives cannot overlap. In this area, the very definition of the notion of “act” is problematic. In order to review the polemics, it suffices if we refer to the theory of commitment (in a moral and ontological sense) proposed by Sartre, a theory used to justify the indictment and conviction of French writers who collaborated with the Nazi regime, under Nazi occupation). Sartre argues that “to publish” is an act. The democratic argument (actually, a fallacy) is that what is censored is the act of publication (a deed that is objectively attributable to the publisher and the author, the only deed relevant to criminal law) and not the discourse itself, no matter how important the ideas would be as a basis for action. 23 Let us note, first, that publishing is tantamount to inciting , in order to admit, in step two, that ideas are actually being censored. 24 Literature relativizes the distinction between mere words and deeds, because, in a sense, the written word (writing) is the writer’s defining activity par excellence. Even without being disseminated, the very substance of creation is tainted. Thus, in the particular case of literature, to prohibit means simultaneously (Korolitski) a professional punishment. What can freedom of expression refer to in the case of a writer who has no right to publish? Guaranteeing this freedom seems to involve the prerequisite that the writer should be allowed to publish his texts, in other words, to disseminate, through publishing, his ideas, visions and conceptions, expressed in writing. If the work is not published and disseminated, the writer is not left with any relevant artistic space of self-expression. It turns out that prohibition has (in the case of the writer) a much more precarious legislative basis, by comparison. Whether what is punishable is the publication of an idea, or the idea itself, taken separately, each of them is insufficient to explain the prohibition. In fact, banning a book means withdrawing tolerance before (culpable) acts are committed; in other words, it means punishing a misdemeanour of opinion.

5. The perverse effects of censorship

Censorship has never been able to ban something permanently. However, unlike the work of art, which has no direct consequences on behaviours, censorship is harmful and produces paradoxical perverse effects. Among them, the following can be listed:

The presence of talent intensifies the act of censorship

The dangers of literature, for example, are commensurate with the author’s talent. Works that later entered the universal cultural heritage may have fallen victim to censorship on this account, while numerous other immoral writings remain unsanctioned legally, even though they are found to be morally reprehensible. Justice is not interested in them, because such writings do not enjoy sufficient notoriety.

Let us admit that this hinges on a limit of censorship, which is aware that it cannot eradicate or even control the (undesirable) phenomenon of pornography, so it tries to limit its public influence. That would explain the interest of censorship in artistic works authored by renowned writers. When such writings contain fragments that are “obscene” or “pornographic,” the influence they may exert on the public, given their prestige, is exponentially higher compared to the creations of specialized pornographers, which remain confined, as a rule, to their own niche of consumers. Such reasoning, invoked with good faith, reveals a logical stalemate: justice condemns (when it decides to do so) the works of great writers precisely because there is a presumption that they exceed the domain of literariness and touch on that of obscenity and pornography. The option to censor mainly these works and not the effervescent and reprehensible pornographic literature per se amounts, however, to an implicit recognition, in reverse, that their authors are genuine artists and not mere pornographers and that their works are, in fact, artistic, in spite of the accusation of pornography. Through the very act of accusing (only) genuine writers, judges seem to recognize the talent of those whom they condemn.

Censorship – an advertising machine

The counter-productive nature of censorship is illustrated by the fact that it often promotes the work it bans, by giving its fame (an “aura”) and increasing its audience. 25 It is not rare for censored works to benefit from a more efficient dissemination than through the official circuitry. The taste for transgression arouses interest in a product that would undoubtedly be less noticeable in the absence of censorship’s sterilizing intervention. A paradox rears its head: censorship accidentally grants (commercial) value to the prohibited work, in the sense that it manages to achieve exactly the opposite of what it intends: instead of delegitimizing, denouncing and limiting access to a banned artwork, censorship, on the contrary, enshrines and creates popularity, a halo, an additional attractiveness. 26 It has a promotional role, like that of a marketing campaign. To the extent that censorship has turned into a kind of involuntary advertising machine, one might say that it contains its own principle of self-destruction: by targeting an artwork, it augments its popularity. This amounts to a defeat for the official system, but for art it is a gain, a victory.

The confrontation between art and justice implies a constant, close and tense negotiation between the right to free expression, on the one hand, and the right to dignity (and identity), on the other. Both can be overstepped and there are situations in which they inconvenience/challenge each other. Therefore, the question whether art must be withdrawn from the social contract field is frequently reiterated. There is a persisting indecision regarding the question whether the freedom of art must be absolute or, on the contrary, if there should be limits to social permissiveness in relation to it. The current debate seems to indicate that relativism cannot be overcome. There are credible arguments on both sides. While we have an intuition that absolute immunity cannot be granted to art and literature, it is hard to argue convincingly in favour of judicial intervention to regulate this sensitive area of society. That is also because no good examples can be invoked, while errors and abuses abound.

The terms of this dilemma also constitute possible criteria according to which the complex and nuanced attitudes that have gained shape can be classified (simplifying, of course, the picture) into two opposed sets: one in favour of the unconditional, non-censurable, absolute freedom of art, and the other in favour of social control. The former brings together voices that say that the act of censorship is of a severity that is incompatible with the specificities of fiction, while the latter groups together opinions that art benefits from a laxity that verges on impunity. As Joel Gilles notes, each of the options is undermined by internal contradictions. If the answer to the need for control is no , it is equivalent to the notion of the insignificance of art and/or risks infantilizing the artist; art is done a disservice, being divested of the challenges that stimulate it (Gilles 21-22). In addition, making an exception for art means establishing an unacceptable conceptual hierarchy among the creations of the human spirit. 27 If, on the contrary, the answer is yes , by this we credit art with meanings that have implications beyond its limits. If you are censored, it means that your work has a social impact and that it is taken seriously. However, we concede that it must be subject to common rules, without claiming that it has the right to escape social prohibition. What complicates the picture even more is the fact that the plans overlap and the same arguments are used with a different purpose in the two camps.

2. The theory of necessary control