An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Broken Windows, Informal Social Control, and Crime: Assessing Causality in Empirical Studies

An important criminological controversy concerns the proper causal relationships between disorder, informal social control, and crime. The broken windows thesis posits that neighborhood disorder increases crime directly and indirectly by undermining neighborhood informal social control. Theories of collective efficacy argue that the association between neighborhood disorder and crime is spurious because of the confounding variable informal social control. We review the recent empirical research on this question, which uses disparate methods, including field experiments and different models for observational data. To evaluate the causal claims made in these studies, we use a potential outcomes framework of causality. We conclude that, although there is some evidence for both broken windows and informal control theories, there is little consensus in the present research literature. Furthermore, at present, most studies do not establish causality in a strong way.

INTRODUCTION

A contemporary criminological controversy concerns the interrelationships among neighborhood disorder, informal social control, and crime. This controversy derives from a rich set of theoretical ideas explaining these relationships. According to Wilson & Kelling’s (1982) broken windows thesis, physical and social disorders exert a causal effect on criminal behavior. Disorder does so directly, as it signals to criminals community indifference to crime, and indirectly, as disorder undermines informal social control. By contrast, theories of informal social control argue that the association between disorder and crime is not causal but is instead spurious because of the confounding variable neighborhood informal control ( Sampson & Raudenbush 1999 ). This theoretical divergence has important implications for criminological theory and public policy. Therefore, the conclusions of empirical research on this controversy are of paramount importance. This review discusses the controversy between broken windows and informal social control by reviewing the current state of empirical research. Perhaps the most important question in evaluating the empirical literature is the degree to which studies approximate causal relations. We use a potential outcomes or counterfactual definition of causality, which has gained prominence in statistics and social science ( Morgan & Winship 2015 , Rubin 2006 ), to assess recent research. We try, whenever possible, to give our own assessments of the relative strengths and weaknesses of the studies—our evaluation of the plausibility of the assumptions made in different research designs. This assessment is open to debate and criticism, but we feel that stating our opinion provides a point of departure for subsequent debate. We conclude our discussion with what we think are important avenues for future research.

Rather than exhaustively covering all studies, we focus on those that are well executed both theoretically and methodologically. Because we are principally concerned with how well studies approximate causality, we organize our discussion by methodological design. We acknowledge that causality is not the only important issue for evaluating empirical studies. Extensive literature exists on the important issues of proper measurement of disorder and informal control ( Hipp 2007 , 2010 , 2016 ; Kubrin 2008 ; Sampson & Raudenbush 2004 ; Skogan 2015 ; Taylor 2001 , 2015 ), implications for public policy—particularly order maintenance policing ( Braga et al. 2015 , Fagan & Davies 2000 , Harcourt 1998 , Kelling & Coles 1997 , Weisburd et al. 2015 )—and micro–macro relationships ( Matsueda 2013 , 2017 ; Taylor 2015 ). We set these aside, referring the reader to the extant literature. We also set aside detailed examination of observational studies of individual-level mechanisms of broken windows evaluated recently by O’Brien et al. (2019) , including fear of crime ( Hinkle 2015 ).

THEORIES OF DISORDER, INFORMAL CONTROL, AND CRIME

Social disorganization theory.

From their exhaustive mapping of delinquency across Chicago neighborhoods, Shaw & McKay (1931 , 1969 ) identified a strong statistical association between disorder and delinquency in which delinquency clustered in zones of transition, characterized by rapid population turnover, impoverished immigrant groups, and few homeowners. Also present were signs of physical and social disorder: dilapidated buildings, vacant lots, homeless and unsupervised youth, panhandling, and other incivilities. Delinquency rates followed a gradient—highest in the central city and progressively lower in the periphery—and remained that way over decades despite drastic changes in neighborhood ethnic composition. To explain these patterns, Shaw & McKay (1969) developed their theory of social disorganization and cultural transmission, in which rapid in- and out-migration and lack of homeownership, as well as high rates of poverty, ethnic diversity, and immigrants, undermined local social organization. Social disorganization—weak and unlinked local institutions—led to unsupervised street youth, who forged a delinquent tradition transmitted from older gangs to unsupervised youth. Shaw & McKay treated physical and social disorder as a manifestation—and, consequently, an indicator—of social disorganization. Disorder does not cause crime but instead indexes disorganization, which causes crime via weak informal control, the prevalence of unsupervised youth, and the creation and transmission of a delinquent tradition across age-graded youth groups.

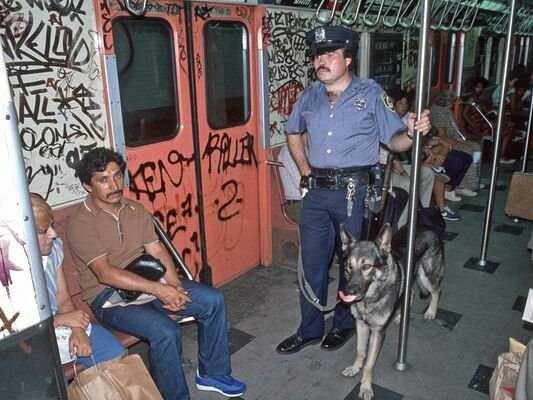

Broken Windows Theory

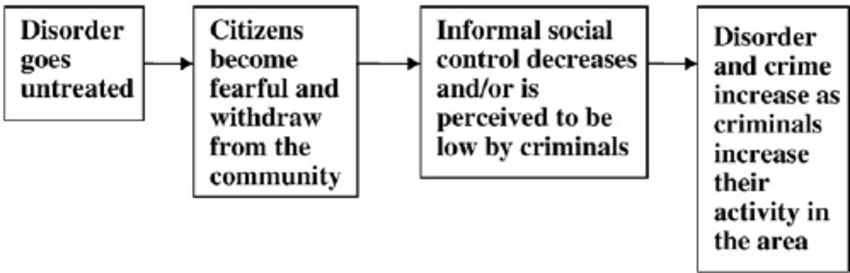

Wilson & Kelling’s (1982) broken windows thesis posits that disorder and crime are causally linked in a developmental sequence in which unchecked disorder spreads and promotes crime. Both physical disorder (e.g., abandoned buildings, graffiti, and litter) and social disorder (e.g., panhandlers, homeless, unsupervised youths) exert causal effects on crime directly and indirectly. Directly, disorder signals to potential criminals that residents are indifferent to crime, emboldening criminals to commit crimes with impunity. This individual-level causal mechanism implies a rational actor: Motivated offenders perceive disorder to mean the absence of capable guardians ( Cohen & Felson 1979 ). Indirectly, disorder induces residents to fear crime, which causes them to avoid unfamiliar people, restrict travel to safe spaces, and withdraw from public life. Disengaged from the neighborhood, fearful residents increasingly feel that combatting disorder and crime is the duty of others. Ironically, signs of local disorder create fear of crime in residents because they assume a causal effect of disorder on crime. Eventually, as disorder and crime increase, residents with sufficient resources begin to leave the neighborhood, taking their capital with them, which undermines both community resources and the capacity for informal social control ( Wilson & Kelling 1982 ). This indirect effect is a neighborhood-level causal mechanism: Rampant disorder causes residents to withdraw, eroding neighborhood control, which fosters crime.

These two pathways form feedback loops, creating a cascading effect of crime and disorder spreading across physical spaces. As Wilson & Kelling (1982) note, one broken window (signaling indifference) is often followed by another and so on, until all windows are broken. This is an informational cascade, as the observation of disorder and crime provides information signaling the absence of social control. Disorder causes residents to withdraw from the community, weakening objective informal social control, and fostering additional crime, disorder, and incivilities, which, in turn, further undermine informal control, leading to more crime. This is a social interactional cascade in which the key causal mechanism is local residents disengaging from community attempts to control disorder and crime. Left unabated, these feedback loops can produce a crime epidemic spreading across time and space.

Figure 1 diagrams the causal relationships among disorder, informal social control, and crime specified by broken windows. Due to reciprocal pathways, this is a nonrecursive model that is underidentified for cross-sectional data without additional information such as instrumental variables (IVs) or a panel design with repeated observations.

Conceptual model of broken windows theory: disorder, social control, and crime. Two paths link disorder to crime: a direct path, in which ( a ) disorder signals community indifference, which increases crime; and an indirect path, in which ( b ) disorder elicits actual community indifference, which weakens social control, which in turn ( c ) increases crime. These effects are reinforced as ( d ) weakened social control stimulates more disorder and ( e ) crime weakens social control. Two feedback pathways ( d and e ) mean this is a nonrecursive model.

Collective Efficacy Theory of Informal Social Control

Sampson (2012) and others (e.g., Morenoff et al. 2001 , Sampson et al. 1997 ) extend Shaw & McKay’s theory of social disorganization by refining the causal mechanism of informal control, which translates neighborhood social organization into safe neighborhoods. They argued that social cohesion, including social capital, is a crucial resource for neighborhoods to solve problems collectively. Drawing from Coleman (1990) , they asserted that neighborhoods rich in social capital—intergenerational closure (parents know the parents of their children’s friends), reciprocated exchange (neighbors exchange favors and obligations), and generalized trust—have greater resources to prevent neighborhood disorder, incivilities, and crime. Such resources are translated into action via child-centered control. Borrowing from Bandura (1986) , they called this entire causal sequence collective efficacy ( Sampson et al. 1997 ). Sampson et al. (1999) specified potential spillover effects for collective efficacy, in which collective efficacy in one neighborhood affects contiguous neighborhoods, producing a social interactional cascade.

Sampson & Raudenbush (1999) used collective efficacy theory to specify causal relationships among disorder, informal control, and crime and in the process offered a critique of broken windows theory. They maintained that collective efficacy not only keeps neighborhoods safe but also keeps them clean. Because social disorder, physical disorder, and crime pose similar problems, neighborhoods high in collective efficacy are able to combat all three problems. Sampson & Raudenbush (1999) argue that, in contrast to broken windows, the correlation between disorder and crime is spurious due to the confounding variable, collective efficacy. Figure 2 depicts the collective efficacy model of disorder, informal control, and crime. This model is a restrictive recursive model nested within the broken windows model. If these restrictions are valid—crime and disorder are related solely because of confounding by exogenous collective efficacy—this model is fully recursive and identified.

Conceptual model of collective efficacy theory: disorder, social control, and crime. The direct path between disorder and crime is spurious (A = 0), and collective efficacy is an exogenous cause of both crime and disorder (B,E = 0). This is a recursive model.

POTENTIAL OUTCOMES (COUNTERFACTUAL) APPROACH TO CAUSALITY

Broken windows and collective efficacy specify competing causal relationships among disorder, informal control, and crime. To adjudicate empirically between the two requires research methods that closely approximate causal relations. To evaluate the disparate research designs used in the empirical literature, we need a framework for establishing causality. The potential outcomes framework, or Rubin causal model, is an approach to causal inference based on counterfactual reasoning using the ideal of a controlled experiment. Rather than considering only the factual statement “a given treatment happened and we observed a particular outcome,” one also considers the counterfactual statement “if a given treatment had not happened, we would have observed a particular (potential) outcome.” These two statements correspond to treatment and control groups in an ideal controlled experiment. Treatment here refers to a variable of primary interest believed to have a causal effect on the outcome under examination. In the classic experimental design, values of the treatment are assigned (manipulated) by the investigator (e.g., in randomized controlled trials, treatments are randomly assigned to subjects). For a variable to be a cause, it must have been manipulated—or, short of that, at least be manipulable in principle ( Holland 1986 ). Thus, this framework is sometimes termed an interventionist definition of causality ( Woodward 2003 ). Although potential outcome(s) is not the only causal framework ( Morgan & Winship 2015 ), it has increasingly become the dominant approach to causality in statistics and the social sciences.

If Y i 1 is the potential outcome of individual i in the treatment state, and Y i 0 is the potential outcome of individual i in the control group, the individual treatment effect is

The fundamental problem of causal inference is that for those in the treatment group, we cannot observe their outcome in the control group; conversely, for those in the control group, we cannot observe their outcome in the treatment group ( Holland 1986 ). Therefore, we cannot compute individual causal treatment effects (Δ i ). Under additional assumptions, however, we can estimate (causal) average treatment effects (ATEs). For example, we can assume, in a randomized experiment with a treatment group and a control group, treatment assignment is ignorable:

where T = 0 , 1 denotes treatment assignment, and ⊥ denotes statistical independence. Here, the difference in the sample means for assignments T = 1 and T = 0 estimates E ( Y 0 − Y 1 ), the ATE of T on Y .

In an observational study, Equation 2 is unlikely to hold due to selectivity or confounding, but treatment assignment may be ignorable after conditioning on covariates Z :

Equation 3 includes the additional identification condition that at each level of the covariates, there is a positive probability of receiving either treatment. The set of conditions described in Equation 3 is known as strong ignorability given covariates ( Rosenbaum & Rubin 1983 ). Here, the conditional ATE (CATE) E ( Y 1 − Y 0 | Z = z ) can be used to estimate ATEs using a properly specified regression or propensity score match that includes all relevant covariates Z . The major difficulty of establishing causality in observational (nonexperimental) studies is the problem of controlling for all relevant Z to achieve conditional ignorability.

Observational studies of disorder, informal control, and crime have used different methods to approximate CATEs. Cross-sectional studies of neighborhoods use observed covariates to control for confounding, under the assumption of no reciprocal causation. Cross-lagged panel models relax this assumption and examine lagged endogenous predictors over time, under the assumptions that there is sufficient temporal variation to obtain stable estimates and that observed covariates achieve conditional ignorability. Fixed-effects panel models relax the assumption that all relevant time-stable confounders are included in the model. By estimating within-individual (neighborhood) variation over time, fixed-effects models control for both observed and unobserved time-stable covariates. Fixed-effects models, however, still require that all relevant time-varying confounders are included. In reviewing the empirical literature on disorder and informal control, we will assess the degree to which studies achieve conditional ignorability.

The definition of unit causal effects makes the stable unit treatment value assumption (SUTVA), a term coined by Rubin (1986 , p. 961): “the value of Y for unit u when exposed to treatment t will be the same no matter what mechanism is used to assign treatment t to unit u and no matter what treatments the other units receive.” SUTVA implies two distinct assumptions: consistency and absence of interference. Consistency means that the mechanism used to assign treatment can be ignored because the outcomes of the treated observations will be invariant to different assignment mechanisms. Thus, an individual assigned a treatment in an experimental setting exhibits the same outcome as if they naturally received the treatment in the real world. Consistency is less likely in experimental settings because the treatment assignments are carried out by the researcher instead of assigned through natural processes in the real world. Results of the experiment may not generalize to real-world settings because of differences in the treatment-assignment process. By contrast, consistency is more likely to hold for observational data given that treatments are assigned naturally in the real world and not through an artificial assignment process.

No interference means that the treatment assignment of one subject does not affect the outcomes of other subjects. This form of contamination can bias treatment estimates in both experimental and nonexperimental designs. Interference often arises via social processes such as spillover effects, displacement, and cascades ( Matsueda 2017 , Nagin & Sampson 2019 ). Interference violates the assumption typically made in observational studies of identically and independently distributed observations (conditional on covariates). When the form of dependence is known, it can be addressed by specific models, such as autoregressive spatial models for spillover effects between contiguous observations or social network models of contagion across individuals.

Beginning with experimental studies, we review the quantitative empirical research on disorder, informal control, and crime, with an eye toward adjudicating between competing theories of broken windows and collective efficacy and evaluating causal claims.

REVIEW OF EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES

Controlled experiments begin with treatment and control groups and manipulate the treatment by intervening in the experimental group. The key to achieving ignorability is ensuring that treatment and control groups are equivalent before the intervention. Randomized experiments ensure groups are probabilistically equivalent by randomly assigning subjects to groups. Because the treatment is manipulated by the researcher, it is strongly exogenous to the outcome, ruling out reciprocal causation. Thus, a well-executed randomized experiment can achieve ignorability and, therefore, strong internal validity. The external validity of experiments is often compromised in three ways. First, observations are rarely obtained through representative sampling, limiting inferences to larger populations of interest. Second, treatment assignments of experiments often differ from the natural way that treatments are assigned in the real world, compromising consistency, and therefore causality, and again limiting generalizability to relevant populations. Third, interference can occur. In individual-level studies, subjects may influence each other on the basis of treatment assignment; in aggregate spatial studies, treatment effects may spill over and affect contiguous aggregate units.

Although a number of studies have attempted to test aspects of broken windows and informal social control using laboratory experiments (e.g., Diekmann et al. 2015 , Engel et al. 2014 ), it is our opinion that no studies we found exhibited sufficient external validity to provide evidence for or against the causal pathways in Figure 1 . Consequently, we examine only field experiments. Compared with laboratory experiments, field experiments trade off some internal validity for gains in external validity. They are conducted in the natural social contexts in which disorder, informal control, and crime are likely to occur and use local subjects who are the typical actors involved. Field experiments use interventions that closely approximate the real-world treatment of interest. This increase in external validity comes at a cost. Because they are conducted in natural settings, field experiments are unable to control the environment of the experiment and, thus, less able to rule out potential confounding factors. Interference, in which subjects of a treatment group affect the outcomes of others, is more likely to occur. Field experiments are typically conducted in a single or small number of geographical locations and rarely use representative sampling of locations or subjects.

A number of field experiments examine the individual-level hypothesis, derived from broken windows, that disorder exerts a direct causal effect on crime (norm violation). The most significant and highly cited broken windows field experiment, Keizer et al.’s (2008) study published in Science , has led to a resurgence of interest in the use of field experiments to study broken windows. Therefore, we discuss this study in some detail. Following Cialdini (2003) , Keizer et al. (2008) conceptualize broken windows as a cross-norm inhibition effect. Descriptive norms reflect common behaviors in a setting, while injunctive norms reflect what is commonly held to be proper in society. Observing a descriptive norm (e.g., seeing litter on the ground) that conflicts with an injunctive norm (e.g., it is wrong to litter) inhibits other injunctive norms as well (e.g., it is wrong to steal). Disorder thus causes crime by reducing inhibitions against criminal behavior. Keizer et al. (2008) conducted six related field experiments in which they manipulated a signal that a contextual norm had been violated (treatment) and then observed whether a target (injunctive) norm was more likely to be violated (outcome).

In the first experiment, the contextual norm was antigraffiti and the target norm was antilittering. Flyers were placed on the handlebars of bicycles parked in an alley of a shopping district. On the wall was a “no graffiti” sign. For the treatment condition, the wall was covered with graffiti; for the control condition, no graffiti was visible. The dependent variable was whether the owner of the bicycle littered the flyer upon returning. Of 77 subjects in each condition, 33% littered in the control condition compared with 69% in the treatment condition, a significant difference. Another experiment placed flyers on bicycles parked in a bicycle shed near a train station, with a treatment condition of the sound of fireworks set off illegally. Again, differences in the incidence of littering the flyers were significant: 26 (52%) littered in the control condition compared to 37 (80%) in the fireworks condition.

A third experiment used a private setting of a supermarket parking garage. The contextual norm was indicated by a “please return your shopping carts” sign and the outcome was littering flyers attached to the windshields of parked cars. In the treatment condition, with unreturned shopping carts strewn about, 35 of 60 (58%) shoppers littered the flyer compared with 13 of 60 (30%) shoppers in the control condition. The fourth experiment used a public setting of a car parking lot, in which the contextual norm was designated by a police ordinance “locking bicycles to the fence is prohibited” sign on a fence outside the lot. The target norm was indicated by a second police ordinance “do not enter” sign at an opening of the fence. In the treatment condition in which four bicycles were locked to the fence, 40 of 49 (82%) subjects violated the “do not enter” sign, whereas only 12 of 44 (27%) violated the norm in the control condition.

The experiment most relevant to broken windows examined theft. Keizer et al. (2008) left a mailing envelope—which was addressed and stamped and had a 5-euro note visible in the envelope’s window—hanging out of a mailbox’s mailing slot. The dependent variable was whether passersby stole the envelope. Two treatment conditions consisted of litter on the ground near the mailbox ( N = 72) and graffiti spray-painted on the mailbox ( N = 60). In the control condition of no graffiti and litter ( N = 71), nine passersby (13%) stole the envelope, compared to 18 (25%) in the litter condition and 16 (27%) in the graffiti condition.

Keizer et al.’s (2008) article is a citation classic, having received nearly 1,000 Google Scholar citations in approximately ten years. It has also spawned a number of studies of broken windows using similar research designs. Nevertheless, the paper has been subject to sharp criticism. Wicherts & Bakker (2014) , in particular, argue that the study is fraught with methodological weaknesses, such as failing to address potential confounding, observer bias, and measurement error; using inflated Type I error rates due to dependencies among subjects; using sequential testing; and failing to control for multiple testing. A major limitation of the study is that each experiment was carried out in a single geographic neighborhood in Groningen, Netherlands, compromising external validity. This criticism has been partially addressed by attempts to replicate Keizer et al.’s (2008) results in different settings. Volker (2017) attempted to replicate Keizer et al.’s (2008) mailbox letter theft experiment in the identical neighborhood as the original study and failed to find significant effects. In their follow-up, Keizer et al. (2011) found the effect of disorder on norm violation stronger in the presence of a sign prohibiting the form of disorder present; however, Wicherts & Bakker (2014) offered similar criticisms to those leveled at the first study. A third study found negative effects of norm violation on prosocial behavior ( Keizer et al. 2013 ).

Keuschnigg & Wolbring (2015) replicated Keizer et al.’s (2008) experiments in two German neighborhoods differing in social capital measured with administrative data. With abandoned and damaged bicycles as a disorder manipulation, they dropped envelopes with five-, ten-, or one-hundred-euro notes and used theft of the envelopes as the outcome. They found treatment heterogeneity: The probability of envelope theft was higher in the disorder condition but only in the low-social-capital neighborhood and for smaller monetary values. This study is significant because it attempts to address the role of informal social control in the disorder–crime relationship. A drawback is that using only two neighborhoods to control for social capital ignores myriad other differences between neighborhoods that may affect theft.

Berger & Hevenstone (2016) conducted field experiments testing the relationship between litter and sanctioning of litterers in Bern and Zurich, Switzerland, and New York. A confederate dropped a bottle near a trash receptacle in view of pedestrians while another recorded whether participants verbally sanctioned the confederate, subtly sanctioned (e.g., an angry glance) the confederate, or picked up the dropped bottle. The researchers manipulated the treatment conditions by introducing bags of garbage and stray litter or conducting the drop farther from the trash can. The manipulation moderately reduced both forms of sanctioning and strongly reduced picking up the bottle. In contrast, dropping the bottle farther from the trash receptacle reduced picking up the bottle but had no effect on sanctioning. Berger & Hevenstone (2016) interpreted their findings as a local effect of litter on both informal social control and cleanup of additional litter, which could produce a cascade effect of littering. They note the presence of interference: In 6.4% of trials, after a participant reacted to the littering, a second individual subsequently joined in sanctioning the confederate. Thus, sanctioning may be a contagious behavior.

These individual-level experiments approximate ignorability by manipulating treatments of graffiti and litter and using naturally occurring passersby, making treatment and control subjects different by the timing of their appearance. Thus, unless treatment and control conditions differ by some confounding event occurring for one but not the other, equivalence seems assured. Furthermore, because the treatment conditions are one-shot transitory events, subjects are unlikely to interfere with each other. The transitory nature of treatment, however, means that these experiments cannot test the hypothesis that repeated exposure to disorder is necessary for norm violations.

A second set of field experiments intervene at the neighborhood level and examine aggregate neighborhood outcomes (see Kondo et al.’s 2018 review). Branas et al. (2018) conducted a randomized experiment of neighborhood disorder in which the main intervention cleaned up physical disorder in vacant lots, created a park-like atmosphere, and maintained the lots on a regular schedule. A second intervention only cleaned up physical disorder. They found that the main intervention, but not cleanup alone, was significantly negatively associated with survey-recorded perceived crime, vandalism, and staying inside due to safety concerns, and positively associated with socializing outside. The main intervention was also positively associated with people watching out for each other but only in neighborhoods below the poverty line. By contrast, both the main intervention and cleanup alone were negatively associated with an index of crimes.

Branas et al. (2018) estimated intent-to-treat models, which estimate treatment effects regardless of whether experimental subjects complied with treatment. If a policy implementing the treatment would result in similar noncompliance, intent-to-treat estimates will give the policy effect expected in the real world. By contrast, if interest is in the effect of actual neighborhood disorder, noncompliance is a problem, and intent-to-treat estimates may be biased. To overcome this, a model controlling for noncompliance uses the randomized intent-to-treat variable as an IV for compliance, yielding an unbiased estimate of the complier average causal effects (CACE) (see Imbens & Rubin 2015 ). Branas et al. (2018) found that CACE and intent-to-treat estimates were similar, suggesting that noncompliance was not a major problem.

This study suggests that neighborhood disorder may undermine social cohesion as well as increase neighborhood crime. The use of randomization ensures ignorability. The manipulated treatment—cleaning up vacant lots—suggests a treatment amenable to public policy intervention, where noncompliance is likely to occur. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the ecological fallacy because we cannot know for certain if the individuals perceiving high disorder are the same ones withdrawing from the community or committing more crimes. In a related study, Branas et al. (2016) found a stronger reduction in firearm violence near vacant buildings that were boarded up and had their exteriors cleaned. The relevance of these studies to broken windows hinges on an untested assumption of symmetric causality ( Lieberson 1985 ): Removing disorder reduces crime; therefore, introducing disorder increases crime. Researchers clearly cannot introduce disorder at the neighborhood level due to the potential for harm but it is conceivable that natural experiments—sudden exogenous increases in disorder—could be exploited to confirm this symmetry.

A third set of experiments come from the moving to opportunity (MTO) studies, which used a randomized quasi-experimental design ( Harcourt & Ludwig 2006 ). Beginning in 1994 in five major cities, MTO randomly assigned 4,600 low-income families—who were living in public housing or Section 8 project-based housing in high-poverty neighborhoods—to one of three groups. A treatment group was offered housing vouchers for moving to neighborhoods having poverty rates of ten percent or less. A Section 8 group was offered housing vouchers to move to any neighborhood. A control group was not offered housing vouchers. Random assignment rules out the potential biasing effects of self-selection into neighborhoods. Approximately half of the families complied with the treatment by relocating through MTO; therefore, intent-to-treat (ITT) models of the opportunity to move were augmented with ATEs on the treated (ATT) using treatment assignment as an IV. Compared with controls, members of the treatment and Section 8 groups moved to neighborhoods lower in poverty and higher in reported informal social control. Nevertheless, in neither ITT nor ATT models did the treatment groups show lower arrest rates, delinquency, or behavior problems by 2001 ( Kling et al. 2005 ). Harcourt & Ludwig (2006) conclude that broken windows is unsupported: Either declines in community disorder do not reduce criminality or their effects are offset by increases in neighborhood socioeconomic status.

Although MTO studies rule out self-selection, for our purposes, they have three weaknesses. First, the treatment is a compound treatment, consisting of movement to a neighborhood with different poverty, disorder, collective efficacy, and other unmeasured characteristics. The studies cannot distinguish between causal effects of these different treatments. Second, analyses do not consider spillover effects. Sobel (2006) has argued persuasively that the no-interference assumption may have been violated. Families given vouchers may be reluctant to move unless their neighborhood friends also move and may be unable to find suitable housing in a tight housing market when many others are given vouchers. Such interference could bias estimated treatment effects. Third, Sampson (2008) suggested that studies using MTO data must be interpreted carefully: Any treatment effect also includes disruptive effects of moving; voucher users moved to destinations lower in poverty but similar on other indicators of disadvantage and embedded in larger disadvantaged areas; and the treatment resulted in only modest changes in conditions. The sample also constitutes a small, highly disadvantaged group subject to years of cumulative deprivation, limiting external validity.

Our review of field experiments of disorder, social control, and crime suggests mixed results. Keizer et al. (2008) consistently conclude that their experiments support the broken windows thesis (direct effect of disorder on norm violation), but those experiments have been criticized on methodological grounds and have failed to replicate in one instance and were replicated only in a neighborhood poor in social capital in another. Some experimental evidence finds support for the effects of disorder on crime at the neighborhood level, although the mechanism is unclear. Disorder may also impede social control behavior at the individual level.

REVIEW OF OBSERVATIONAL (NONEXPERIMENTAL) STUDIES

Observational studies typically combine survey data on individuals within neighborhoods with administrative data from police and the census. In principle, such nested data allow estimation of combined micro–macro models, but in practice, this research typically models macro relationships among variables aggregated to neighborhoods. A major advantage of observational studies of neighborhoods is they examine natural variation across a representative sample of neighborhoods, making external validity strong. Because the research environment lacks the controls of experiments, however, there are greater threats to internal validity, as ignorability is difficult to approximate. Observational designs differ in how they address the problem of ignorability. Research on disorder and control can be categorized into four nonexperimental designs and models: ( a ) recursive cross-sectional models; ( b ) nonrecursive simultaneous equation models; ( c ) fixed-effects panel models; and ( d ) cross-lagged panel models.

Cross-Sectional Recursive Models

Cross-sectional recursive models are commonly used to examine community theories of crime. The key independent variables, disorder and social control, are not manipulated by the researcher but rather are endogenous. To rule out what econometricians term endogeneity bias, these models rely on two strong assumptions. First, treatment assignment—the process by which neighborhoods attain a level of social control or disorder—is ignorable conditional on exogenous control variables. Thus, all relevant covariates are included in the model. Second, reverse causality—crime affecting either disorder or social control—is absent.

In an important cross-sectional study of neighborhood disorder and crime, Skogan (1990) pooled surveys covering 40 areas in six major US cities to examine a model of disorder and decay. Under the assumption that his path models were well specified, he found a strong effect of perceived disorder on crime, in which disorder mediated the effects of poverty, residential instability, and racial heterogeneity on crime, supporting broken windows. Disorder was measured with an index of social and physical disorder indicators that displayed convergent and discriminant validity. Skogan noted that informal social control is negatively correlated with disorder; however, he did not include it in his structural models. Harcourt (1998) reanalyzed Skogan’s data, excluded a small number of neighborhoods with unusually high disorder and crime, and found results were not robust, although, as Xu et al. (2005) pointed out, Harcourt’s reanalysis lacks statistical power.

Cross-sectional studies have also supported theories of informal control (e.g., Sampson & Groves 1989 ). Using police data, census data, and survey data on 8,782 residents from 343 Chicago neighborhoods from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN), Sampson et al. (1997) examined collective efficacy, sociodemographic structure, and crime. Collective efficacy was measured by residents’ reports of informal control (e.g., would neighbors intervene if children were committing deviance?) and social cohesion (e.g., neighbors help each other) adjusted for differential composition of informants across neighborhoods. Using three-level hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) models, they found that collective efficacy was strongly negatively related to survey-measured victimization and perceived crime as well as police-reported homicides. Collective efficacy also mediated much of the effects of neighborhood disadvantage, residential instability, and immigration. Although this study was carefully conducted—particularly in addressing measurement issues—the cross-sectional design could not rule out reciprocal effects.

Subsequent cross-sectional studies replicated Sampson et al.’s (1997) results in other settings or under varying specifications (e.g., Mazerolle et al. 2010 , Sampson & Wikström 2008 , but not Bruinsma et al. 2013 ). Matsueda & Drakulich (2016) augmented Sampson et al.’s (1997) models to adjust individual perceptions of collective efficacy for perceived deviance. Using the Seattle Neighborhoods and Crime Survey, they found that respondents who observe deviance in their neighborhood report a lower likelihood of neighbors intervening. Nevertheless, controlling for observed deviance resulted in a stronger association between collective efficacy and crime.

Neighborhoods in closer proximity tend to be more similar than those far apart, resulting in spatial autocorrelated data. This can be due to substantive processes, such as spillover or cascade effects, or methodological artifacts, such as spatial mismatch in which the true unit of analysis in causal processes differs from the unit used in the study (see Sampson et al. 1999 , Taylor 2015 ). In either case, the result can be interference as, for example, social capital in one neighborhood (treatment) spills over into a low-social-capital neighborhood (control), lowering its crime rate. Sampson et al. (1999) reanalyzed PHDCN data using first-order spatial autoregressive lag models and found evidence of spillover in neighborhood collective efficacy.

Morenoff et al. (2001) reanalyzed PHDCN data to explore spillover effects in models of social ties, collective efficacy, and future homicide rates. By controlling for homicide rates for three years preceding the survey, they partially address ignorability as prior homicide partly absorbs unobserved (omitted) stable covariates. They find organizations and social ties important for predicting collective efficacy (but not crime). They also find that collective efficacy predicts lower homicide rates but does not mediate socioeconomic disadvantage as strongly as found in Sampson et al. (1997) . Building on this model, Browning et al. (2004) found that collective efficacy predicts lower homicide rates, but the effect is attenuated in the presence of dense social ties (see also Bellair & Browning 2010 ). This suggests that measures of network density moderate collective efficacy and cannot serve as a proxy for informal control (e.g., Markowitz et al. 2001 ).

In sum, cross-sectional studies find effects of neighborhood disorder on crime and effects of informal control on crime that persist in the face of spatial autoregression. These studies do not manipulate disorder or informal control and thus make strong assumptions about causal order (no reciprocal causation) and ignorability (controls for social disorganization achieve conditional ignorability).

Nonrecursive (Simultaneous Equation) Models

In principle, simultaneous equation models with IVs resolve the problem of reverse causality for nonexperimental studies in which treatments are not manipulated but rather are assigned through an endogenous process (e.g., Greene 2003 ). Figure 3 depicts a nonrecursive model in which social control and crime are simultaneously determined. The problem here is that, in the crime (social control) equation, the endogenous predictor, social control (crime), is correlated with the disturbance ε 1 ( ε 2 ), which violates a key assumption of the general linear model, causing estimates to be biased. To resolve this, at least one IV that strongly predicts social control but has no direct effect on crime—holding social control constant—is needed to identify the effect of social control on crime. Similarly, at least one IV that strongly predicts crime but not social control—holding crime constant—is needed to identify the effect of crime on social control. These exclusionary restrictions, in which γ 1 = γ 2 = 0, are indicated in Figure 3 .

Nonrecursive model of social control and crime with lagged instrumental variables (IVs). Social control and crime are reciprocally related ( β 1 , β 2 ) with correlated errors ( ε 1 , ε 2 ). The assumption that the IVs for social control and crime have no cross-lagged effects—signified by the restrictions γ 1 = γ 2 = 0 ( dotted lines )—permits identification.

Sampson & Raudenbush (1999) used nonrecursive models to estimate causal relationships among collective efficacy, disorder, and crime while controlling for crime’s effect on collective efficacy. They used systematic social observation (SSO), an innovative method of measuring disorder across neighborhoods: Videos of street blocks taken by SUVs driving through streets of Chicago during daylight were coded for signs of social and physical disorder. Following Sampson et al. (1997) , they measured collective efficacy using a multilevel measurement model of PHDCN data; crime is captured by police-reported homicide, robbery, and burglary. To identify the reciprocal effects between collective efficacy and crime, the authors assumed that reciprocated exchange among neighbors and attachment to neighborhood (IVs for collective efficacy) affect crime only indirectly through collective efficacy. They used geocoded victim-based homicides from death records as an IV for police-reported crimes under the assumption that resident-based homicide affects collective efficacy solely through police-reported crimes. Sampson & Raudenbush (1999) found, contrary to broken windows, no direct relationship between disorder and crime net of collective efficacy for homicide or burglary. They did, however, find support for a “feedback loop, whereby disorder entices robbery, which in turn undermines collective efficacy, leading over time to yet more robbery” ( Sampson & Raudenbush 1999 , p. 637). Researchers have critiqued Sampson & Raudenbush for assuming that crime does not feedback on disorder and disorder does not feedback on collective efficacy, and therefore, there could be an indirect pathway of disorder on crime through collective efficacy ( Gault & Silver 2008 , Xu et al. 2005 ). O’Brien & Kauffman (2013) replicated Sampson & Raudenbush’s (1999) main results using a survey of rural youth with respondent prosociality—rather than crime—as an outcome. They found rater-assessed and respondent-perceived disorder were unrelated to prosociality, but collective efficacy predicted both disorder and low adolescent prosociality. Although Sampson & Raudenbush specify collective efficacy as a composite of cohesion and expectations for social control, Taylor (1996) found disorder negatively related to social control and positively related to cohesion—effects that canceled out in reduced forms.

Sampson & Wikström (2008) used data from 3,992 individuals in 200 Stockholm neighborhoods and Chicago’s PHDCN to make a cross-national comparison of relationships among collective efficacy, perceived disorder, and crime, controlling for indicators of social disorganization. They found collective efficacy negatively associated with neighborhood crime and victimization in both cities. Sampson & Wikström (2008) found that, controlling for collective efficacy, disorder had a strong positive association with reported violent crimes in Stockholm but not in Chicago. Although these results provide evidence for cross-national consistency in collective efficacy, they also reveal the disorder–crime relationship in Stockholm survives controlling for confounding collective efficacy, a finding that supports broken windows.

Using data from the British Crime Survey, Markowitz et al. (2001) applied nonrecursive models to relationships among burglary, social cohesion, fear of crime, and perceived disorder. To identify the simultaneous parameters, they used lagged versions of endogenous variables as IVs. Thus, the exclusion restriction is no lagged effects in the presence of contemporaneous effects. The authors used survey measures of disorder (e.g., neighborhood litter, vandalism, and loitering teenagers), social cohesion (organizational participation, helping behavior, and neighborhood satisfaction), and fear of crime (fear walking after dark and worried about burglary or robbery). They summed and aggregated the indicators to create neighborhood-level indices. They controlled for disorganization (ethnic heterogeneity, family disruption, and urbanization) to achieve ignorability. In cross-sectional models, Markowitz et al. (2001) found a nonsignificant effect of disorder on burglary, holding constant cohesion and previous burglary. Both nonrecursive and cross-lagged panel models reveal cohesion and disorder are reciprocally related (each at −0.18 standardized), as are burglary and disorder. Furthermore, they found a feedback loop in which social cohesion reduced burglary and disorder, each of which increased fear of crime, which in turn, fed back to reduce social cohesion. These findings generally support broken windows.

Previous studies using nonrecursive models also found evidence that crime—particularly robbery—is associated with less informal social control. Liska & Warner (1991) modeled the reciprocal effects between crime and constrained social behavior (a combination of fear of crime, going out at night, and limiting activities because of crime). Using the US National Crime Survey, they analyzed crime victimization (robbery and a general index of felony crimes) for 26 cities. To identify their simultaneous equations, they used population density as an instrument for crime (assuming no direct effect on constrained social behavior) and media coverage of homicide for constrained social behavior (assuming no direct effect on crime). These are very strong assumptions. They find a reciprocal relationship between robbery and constrained social behavior: Constrained social behavior reduces robbery and other victimization, but robbery also increases constrained social behavior.

Using data on 100 Seattle neighborhoods, Bellair (2000) estimated nonrecursive models of informal surveillance and crime, comparing burglary with a combined measure of robbery and stranger assault. Following Sampson & Raudenbush (1999) , Bellair used reciprocated exchange among neighbors as an instrument for informal control. He used unsupervised teenage groups as an instrument for crime. Because the presence of unsupervised teens is likely to elicit more surveillance even when crime is held constant, Bellair (2000) tried other instruments for crime, including percentage of bars and clubs in the neighborhood and percentage of 16–19-year-olds in the neighborhood (note that each instrument could also affect surveillance directly). Nevertheless, Bellair found that robbery and stranger assault reduce informal surveillance by increasing perceived risk of victimization, which leads to withdrawal from public spaces. Conversely, burglaries lead to greater surveillance. Furthermore, controlling for perceived risk of attack, surveillance is negatively associated with robbery and assault, but not burglary.

In sum, nonrecursive models appear to find a reciprocal causal relationship between informal control (social cohesion) and disorder. Sampson & Raudenbush (1999) found collective efficacy reduces crime but not vice versa, and the effect of disorder on crime is largely spurious due to the confounder, collective efficacy. Other studies, however, find reciprocal effects between informal control and crime, and one finds support for the broken windows indirect pathway in which social cohesion undermines disorder, disorder fosters fear of crime, and fear of crime feeds back to reduce cohesion ( Markowitz et al. 2001 ).

In principle, simultaneous equation models allow researchers to estimate feedback effects; however, in practice, such models require researchers to make strong assumptions to identify key parameters. Consequently, recent applications of simultaneous equations have searched for naturally occurring strong instruments, such as lotteries that randomize treatments to subjects, as in the military draft (e.g., Angrist & Krueger 2001 ), or naturally occurring exogenous shocks that create strong instruments. For example, Kirk (2015) used Hurricane Katrina as an exogenous intervention that dispersed parolees geographically to estimate the effects of returning parolees to their local neighborhoods on recidivism rates. Unfortunately, such strong instruments have not been available to identify nonrecursive relationships among disorder, control, and crime, leaving results open to question.

Panel Models: Cross-Lagged Effects and Fixed Effects

Panel designs collect data on samples of observations repeatedly over short time spans. Researchers examining disorder, informal control, and crime have typically used one of two panel models. First are cross-lagged panel models, in which the interrelationships among time-varying endogenous variables are modeled as first-order lagged variables. Thus, the models estimate (residualized) change in endogenous variables. In Figure 4 , these lagged effects include stability effects (e.g., social control on itself) and cross-lagged effects (e.g., social control on crime and vice versa). Cross-lagged panel models address causality in several ways. The cross-lagged effects specify a causal order among variables consistent with their temporal order. To obtain ATEs in dynamic panel models, one assumes sequential ignorability (conditional ignorability at each time point) ( Rosenbaum & Rubin 1983 ). Sequential ignorability is addressed by including potential time-invariant confounders (exogenous controls in Figure 4 ) as well as stability effects, which help absorb unobserved heterogeneity. Thus, selection into endogenous variables is assumed to be captured by a combination of observed confounders, stabilities, and cross-lags. To obtain stable estimates, cross-lagged panel models make substantial demands of the data: Endogenous variables must have changed sufficiently to model change, and contemporaneous correlations among endogenous predictor variables must be low enough to provide sufficient statistical power, given modest samples of neighborhoods.

Cross-lagged panel model of social control and crime. T1, T2, and T3 represent time periods. Social control (crime) impacts both social control and crime in the next period. Double-headed arrows between ε indicate correlated errors.

Second are fixed-effects models. These models pool the time-series cross-sectional data, yielding NT observations, where N is the number of neighborhoods and T is the number of time periods (waves). Fixed-effects models control for unobserved heterogeneity (time-stable omitted confounders) by estimating within-neighborhood variation by, for example, including N – 1 dummy variables. Thus, fixed-effects models capitalize on panel data to attain conditional ignorability by controlling for all unobserved stable confounders (see Sobel 2012 for assumptions needed to obtain ATEs in fixed-effects models). All relevant time-varying covariates are assumed to be included in the model. Fixed-effects models can include lagged variables—including crosslags—which make greater demands of the data ( Allison et al. 2017 , Wooldridge 2010 ).

Taylor (2001) used two waves of data spaced 12 years apart in 66 tracts in Baltimore to examine the effect of disorder on crime, fear of crime, avoiding dangerous locations, and intentions to move. Disorder was measured by raters observing neighborhoods and separate respondent-perceived physical and social disorder. Taylor found that each indicator of disorder was linked to a different form of crime. This implies different types and measures of disorder may operate as different treatments and combining them into a single measure may mask their separate effects. Using multilevel models, he found both assessed and perceived disorder were associated with fear of crime at the individual level, although only perceived social disorder was associated with avoiding dangerous places and intentions to move. Taylor argued that rater assessments of disorder failed to capture social disorder most troubling to residents—because it is transient and relatively rare—which draws into question objective measures like SSO in capturing a key form of disorder. Taylor does not examine spatial or reciprocal effects.

Using administrative data and ecometric measurement models of survey responses from the Boston Neighborhood Survey, O’Brien & Sampson (2015) examined disorder and crime with two-period cross-lagged panel models. Applying exploratory factor models to police dispatch data, they obtain four measures of conflict and disorder: public social disorder (e.g., public intoxication), public violence (e.g., assault), private violence (e.g., domestic violence), and gun prevalence (e.g., shootings). Physical disorder is measured with counts of reports for private neglect (e.g., housing issues) or public denigration (e.g., detritus) (see O’Brien et al. 2015 ). All measures were aggregated to census tracts. They also included time-invariant controls: percent Hispanic, percent black, income, and baseline collective efficacy.

O’Brien & Sampson (2015) found that no form of disorder or violence was predicted by (or predictive of) public physical disorder. Public social disorder did, however, moderately predict public violence (standardized β = 0.11), although less strongly than did private conflict (0.17). Public social disorder was strongly predicted by private conflict (0.33) and public violence (0.22). This indicates a reciprocal relationship between public violence and public social disorder (but not physical disorder), which supports broken windows theory. The authors could not examine whether social disorder operated through informal social control—the indirect pathway of broken windows—because collective efficacy was measured only at the baseline. The authors also report a second feedback loop of personal conflict in which private conflicts escalate to gun violence: Private conflict predicts gun violence directly (0.19) and via public violence (0.17), which also predicts gun violence (0.20), and gun violence in turn feeds back on future private conflict (0.33). They interpret this result as supporting a social escalation model, in which private conflicts spill over into public spaces. These analyses are limited to residential neighborhoods only, which may inhibit generalizability, as crime and disorder are often concentrated in nonresidential areas ( Yang 2010 ).

Using quasi-experimental methods and panel models, Wheeler et al. (2018) examined the effect of vacant property demolitions on crime. Vacant properties are a form of disorder that may increase crime by signaling low social control (broken windows) or providing opportunities to commit crimes out of sight (situational opportunity). Increases in crime may, however, be spurious if crime and vacant lots are each the result of social disorganization. To examine this, Wheeler and colleagues capitalize on 2,000 demolitions occurring in Buffalo, New York, between 2010 and 2015 to model changes in crime at neighborhood and microplace levels. They estimate a difference-indifference model that matches demolished properties to nondemolished controls using propensity scores based on pretreatment crime and local demographic composition. Comparing crimes before and after demolition at exact addresses and varying distances, they found reductions in crime averaged 90% at demolished parcels. Significant reductions were seen out to more than 1,000 feet. To minimize interference between treatment and controls, the authors estimated a neighborhood-level spatial panel model relating counts of demolitions in census tracts to changes in crime. At the tract level, they found mixed results, as demolitions exerted no significant effects on violent crimes or total police calls, and only a significant spatial effect on nonviolent crimes. That is, demolitions in adjacent neighborhoods are associated with crime reductions, but demolitions within the neighborhood are not. Together these results suggest that removal of vacant properties may reduce crime at the microlevel but may not suppress overall crime in a neighborhood.

Using a two-period cross-lagged, spatial autoregressive model, Boggess & Maskaly (2014) examined effects of disorder on robbery, assault, and disorder in Reno, Nevada. They measured disorder using police calls about intoxication, unwanted persons, graffiti, abandoned vehicles, litter, and dumping and used police-reported robbery and assault as outcomes. They found that, controlling for neighborhood sociodemographic composition, disorder predicts robbery and assault. They also found weak spatial relationships and a modest feedback effect of crime on disorder. However, with no measures of informal control or fear of crime, they cannot rule out spuriousness, and cannot estimate indirect paths between disorder and crime. Their use of police reports for both disorder and crime may introduce a response set, as invoking police is a form of social control. Although Boggess & Maskaly did not provide interwave correlations for disorder, the magnitude of the lagged disorder coefficients (greater than 0.96), large standard errors of other predictors, and a sample of only N = 117 suggest low statistical power.

Wheeler (2017) examined the effects of 311 calls (complaints to the city for physical disorder) on crimes at microplaces (street segments and intersections) in Washington, DC. He divided 311 calls into two categories—detritus (e.g., garbage, abandoned vehicles, illegal dumping) and infrastructure (e.g., potholes, damaged sidewalks, graffiti)—and created an index of serious police-reported crime. The models were carefully done, addressing a number of threats to internal validity. To address ignorability, Wheeler used fixed-effects models to eliminate stable unobserved neighborhood effects, with neighborhoods defined as 500-m squares. To address reciprocal causation, he controlled for prior crime in models of future crime. To model cascading effects of broken windows, he used a first-order, spatial autoregressive lagged crime variable. Wheeler (2017) found that both forms of physical disorder were modestly associated with future crime: An increase of 50 disorder calls for service was significantly associated with one fewer crime. This study is limited exclusively to physical disorder, which may be less consequential for crime than social disorder ( St. Jean 2007 , Yang 2010 ). Furthermore, Wheeler acknowledges that 311 calls are likely to be correlated with informal control against crime, and therefore, disorder could be capturing effects of unobserved informal control.

Although most studies of disorder and informal control use data from the United States, a few apply panel models to other nations. Steenbeek & Hipp (2011) used ten-year panel data from 74 neighborhoods in Utrecht, Netherlands, and distinguished potential informal control (social cohesion and shared expectations for control) from behavioral informal control in cross-lagged models of disorder, social cohesion, and informal control. They did not model crime. Their cross-sectional models replicated previous findings in which social control reduces disorder. Their panel models, however, showed no effect of social control or cohesion on future disorder. By contrast, they found disorder to be negatively associated with future control potential (consistent with broken windows) and residential stability; stability, in turn, is positively associated with future disorder. Disorder is positively associated with future control behavior, which has no significant effect on later disorder. Using first-order spatial- (and temporal-) lagged dependent variables, they find substantial spillover effects between neighborhoods. The authors’ intertemporal correlation tables suggest very high correlations for demographic variables, disorder (0.92–0.96), and cohesion (0.95–0.96), suggesting little change to be explained and potentially weak power of the tests ( Steenbeek & Hipp 2011 ).

Several related papers have examined collective efficacy and crime using panel data from the Australian Community Capacity Study (ACCS), which collected survey data on 4,334 residents across 148 neighborhoods in Brisbane. Hipp & Wickes (2017) followed Sampson et al. (1997) in measuring collective efficacy as a composite of willingness to intervene, cohesion, and trust and controlling for differential distributions of informant characteristics across neighborhoods that may bias reports of collective efficacy. They estimated cross-lagged models for collective efficacy, violence, and neighborhood characteristics (e.g., disadvantage, residential stability, age, population density) and included spatially lagged neighborhood characteristics to control for spillover. They found that, contrary to collective efficacy theory, controlling for prior violence, collective efficacy is significantly associated with future violence—but in the wrong direction. This result held in models using five-year lags and two-year lags and in simultaneous equations using lagged dependent variables as instruments. They also found a small negative indirect effect of collective efficacy on violence through concentrated disadvantage. Although the authors did not present intertemporal correlations among variables, they reported stability coefficients of 0.82 for violence, suggesting modest change, which, combined with the sign flip for collective efficacy, may suggest weak power of statistical tests. It is noteworthy that Sampson (2012) reported evidence for a reciprocal relationship between violent crime and collective efficacy in Chicago using hierarchical cross-lagged panel models. This suggests that the divergent findings may be the result of contextual, rather than methodological, differences between the Brisbane and Chicago studies: Chicago is a larger city with more variation in violent crime.

Wickes & Hipp (2018) used similar models on the same ACCS data set but included three measures of collective efficacy—child-centered social control, reciprocated exchange, and exercise of informal control (attend a meeting, sign a petition, solve a problem with neighbors)—which they hypothesize should have independent effects on crime. They found reciprocal relationships between disadvantage, nearby disadvantage, and all three measures of informal control. Moreover, Wickes & Hipp (2018) found that, contrary to collective efficacy theory, no measure of collective efficacy consistently predicted future crime in the expected direction. Social ties were significantly associated with property crime and drug crime in the wrong direction, control expectations were negatively associated with drug crime only, and exercise of social control was negatively associated with violence only. Interestingly, at the bivariate level, child-centered control is significantly correlated (0.3–0.4) with all crime measures in the direction hypothesized by collective efficacy theory, while the other measures of social control are uncorrelated with all crimes (see appendix 2 in Wickes & Hipp 2018 ). This, with fairly high stabilities for violent crime and property crime, raises the issue of the power of tests of informal control as well as whether the models are controlling for different aspects of the same concept (collective efficacy).

Most studies of disorder, social control, and crime use data from large urban areas, which is consistent with the model of urban growth underlying social disorganization theory. Do results generalize to less-urban settings, where the dynamics of neighborhood residential patterns may be different? Hipp (2016) used block-group-level data from rural North Carolina to examine disorder, informal social control, and perceptions of neighborhood crime in three-wave cross-lagged panel models. Using conventional measures of social cohesion and collective efficacy, Hipp controlled for potential bias in neighborhood reports due to compositional differences in residents across neighborhoods. To measure crime, he asked respondents whether they may have seen or heard acts of violence, arrests, and drug dealing around their neighborhoods and then aggregated responses to the block group. The measures of disorder asked respondents their general impressions of the neighborhood (Do respondents believe neighbors take care of homes and respect property? Is there too much drug use in the neighborhood?).

Using a cross-sectional model, Hipp (2016) replicates Sampson & Raudenbush’s (1999) finding of collective efficacy negatively associated with crime and of both collective efficacy and cohesion negatively associated with disorder. In cross-lagged panel models, he found perceived disorder and crime negatively associated with future collective efficacy, which he interprets as evidence of updating: Respondents’ perceptions of crime and disorder signal weak social control, causing them to update their perceptions of collective efficacy downward (see also Matsueda & Drakulich 2016 ). Furthermore, in a main-effects model, Hipp found that, contrary to collective efficacy theory, neither collective efficacy, social cohesion, nor a composite of the two significantly predicted future perceived crime or disorder. He does, however, find evidence of an interaction effect between social cohesion and collective efficacy. By contrast, consistent with broken windows, disorder predicts future crime. This study provides perhaps the most direct support for broken windows over collective efficacy and contrasts with Sampson & Raudenbush’s (1999) findings. This divergence of findings may be due to differences in measures of crime and disorder (Hipp’s are notably weaker), in simultaneous equation models versus panel models, and in urban versus rural settings.

In sum, panel models find mixed results. In models of disorder and crime, research finds a modest effect of disorder on violence and robbery, even controlling for collective efficacy. Demolitions were modestly associated with future crime at addresses and microplaces but not at the tract level. Cross-lagged panel models find collective efficacy either unrelated to crime, positively related to crime in Brisbane, or moderated by cohesion in rural North Carolina.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Our review of recent causal claims about disorder, informal control, and crime finds a lack of consensus across studies. Turning first to causal links in models of informal social control ( Figure 2 ), some evidence suggests that crime undermines informal control, but this may be limited to robbery. With the exception of one panel study, most research using different designs finds that informal social control is negatively associated with future disorder. Research on the key proposition of collective efficacy and informal social control is mixed. Cross-sectional studies find strong inverse effects of informal control on criminal behavior in different cities in the United States and several other countries. Such studies are unable to address potential reciprocal relationships between informal control and crime, which could result in upward bias. Nonrecursive models address this issue, but those that identify collective efficacy with reciprocated exchange as an instrument find informal control generally affects crime, whereas those that use lagged informal control do not. Cross-lagged panel models, however, show little effect of collective efficacy on future crime in Brisbane or on disorder in Utrecht, and only an interaction effect with cohesion in rural North Carolina, drawing into question theories of informal control. Given that panel models explain change in crime, it could be that collective efficacy can explain variation in crime across neighborhoods but not over time. Alternatively, the panel data sets used may lack sufficient statistical power to detect effects of informal control on temporal variation in crime. Thus, to date, an important counterfactual remains unanswered: In a data set with sufficient change in key endogenous variables and sufficient statistical power of tests, would we find effects of informal social control on changes in crime and disorder?

Evidence on the causal links implied by broken windows theory ( Figure 1 ) is also mixed. The experimental studies of Keizer et al. (2008 , 2011 ) find disorder associated with minor norm violations in Groningen, but another study failed to replicate this result in Groningen while another found treatment heterogeneity by social capital in Germany. With one exception, cross-sectional studies find modest effects of combined social and physical disorder on neighborhood crime. Of the four studies testing the broken windows hypothesis that disorder fosters crime when controlling for informal control, one nonrecursive cross-sectional model found little effect in Chicago, whereas three cross-lagged panel models found modest but significant effects in Boston, rural North Carolina, and Brisbane. Experiments in Bern, Zurich, and New York, the panel study in North Carolina, and one nonrecursive model in Britain found disorder undermines future social control, whereas a second nonrecursive model failed to find a significant effect in Chicago. The positive results would suggest support for disorder affecting crime indirectly through informal control, except that, unlike cross-sectional studies, cross-lagged panel models find little effect of collective efficacy on crime.

In evaluating this research literature, we have come to five tentative conclusions about the relative merits of different research designs as implemented to date. First, individual-level field experiments of disorder on norm violations are promising for testing the specific behavioral principles underlying broken windows. Such experiments can approximate ignorability when conducted with care. The results of recent experiments, however, are questionable because of methodological weaknesses ( Wicherts & Bakker 2014 ). Furthermore, when applied to broken windows and informal control theories, these experiments lack consistency and external validity, and, therefore, to be relevant to criminological debates they must be augmented with studies of naturally occurring crime. Second, we have greater enthusiasm for field experiments that intervene in neighborhoods by manipulating urban blight ( Kondo et al. 2018 ). These experiments manipulate, in a policy-relevant way, the key concept of disorder and examine serious crime. Unfortunately, we could not find parallel interventions seeking to manipulate informal social control. Third, MTO studies, which found few effects of individual moves on crime while eliminating selectivity, are less useful for our task because they cannot disentangle disorder, informal control, and other neighborhood characteristics.

Fourth, we began assuming that well-specified nonrecursive models are stronger than cross-sectional recursive models but weaker than panel models. In this applied literature, however, nonrecursive models are only as valid as the identifying restrictions on IVs. Panel models, while superior in principle, require sufficient change in dependent variables and sufficient statistical power of tests, which may be lacking in applications. Statistical power may also be an issue in simultaneous equation models, given that the power of simultaneous parameters is dependent on, among other things, the strength of IVs ( Bielby & Matsueda 1991 ). Rather than treating such models as panaceas for the possibility of feedback effects, each study needs to be carefully examined for whether the data are up to the assumptions of the models. The model could be correct, but the data are insufficient to estimate the model’s parameters. Fifth, interference is often present in neighborhood models as revealed by spatial analyses; such studies, however, typically do not discuss the degree of bias resulting when interference is ignored.

Although we find mixed results on most key hypotheses, we can make a tentative assessment of where the preponderance of the evidence currently lies. First, informal social control appears to be negatively associated with crime and disorder in urban areas. The negative evidence from panel studies may be the result of inadequate power of tests. Second, disorder—particularly social disorder—appears to be positively associated with future crime and disorder. The causal mechanism could be the broken windows hypothesis that disorder signals weak neighborhood control, or that such disorder generates crime opportunities or conflict, as suggested by Branas et al. (2018) , O’Brien & Sampson (2015) , St. Jean (2007) , and Wheeler et al. (2018) . This association drops substantially when holding constant informal social control but appears not to drop to zero. Third, disorder appears to be negatively associated with future informal social control, implying the possibility of a small indirect effect of disorder on crime operating through informal social control, as suggested by broken windows.

These conclusions are tentative because they will likely change as more research is accumulated. We have deliberately stated these conclusions as empirical associations rather than causal effects because, taken as a whole, these studies of disorder, informal control, and crime remain far from approximating causality as defined by a potential outcomes approach. Consistency is a problem in most experiments, interference is an issue in MTO studies, and ignorability is questionable in most observational studies.

Because these research designs have distinct strengths and weaknesses, more studies within each design are called for, with the hope that consistent results emerge across disparate designs. Future research is needed to address shortcomings in the literature. Individual-level field experiments need to conduct power analyses to ensure sufficient power of tests and conduct experiments in multiple neighborhoods to increase external validity and examine treatment heterogeneity by neighborhood. Given the issues of insufficient change and weak statistical power of tests in neighborhood panel studies, researchers may want to consider modifying research designs. Larger samples, perhaps on smaller neighborhood units, are needed. If the focus is on relatively short-term change, as in most panel studies, studies might examine multiple cities undergoing dynamic change rather than studying older stable metropolitan areas. Within cities, neighborhoods exhibiting change in local organization, disorder, and crime might be oversampled and followed for longer periods, maximizing the likelihood of change. Incorporating neighborhood interventions into panel studies would further leverage change.

Innovative interventions at the neighborhood level, such as randomly assigned demolitions, cleanup campaigns, and greening programs, are needed to examine whether exogenous changes in neighborhood disorder affect crime and informal control. More pressing is the need for studies of informal social control that use experimental interventions to manipulate social capital and collective efficacy across neighborhoods. Finally, while we have focused on causality as the key issue in evaluating the empirical literature on disorder, informal control, and crime, we hope our evaluation will stimulate not only future empirical research but also the further development of theories of disorder, crime, and informal control.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS