ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Exploring the relationship between corporate social responsibility, trust, corporate reputation, and brand equity.

- 1 School of Management, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China

- 2 Department of Business Administration, Institute of Social Sciences, Istanbul Okan University, Istanbul, Turkey

- 3 Department of Economics and Statistics, Dr. Hasan Murad School of Management, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan

- 4 School of Management, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China

The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR), corporate reputation (CR), and brand equity (BE). Building on the resource-based theory of the firm, this study proposes a theoretical framework. In this framework, CSR is theorized to strengthen CR and brand equity, directly and indirectly, through consumer trust. We used a questionnaire survey approach. In the questionnaire, 17 items were used with a 5-point Likert-Scale (1 stands for “strongly disagree,” and 5 stands for “strongly agree”). Data were collected from the consumers of the banking sector in the vicinity of Lahore, Pakistan. To estimate the proposed relationships in the conceptual model, we use structural equation modeling (SEM) through Smart PLS 3.2. The outcomes of this study confirm that CSR significantly impacts CR and brand equity. It is also demonstrated that trust mediates positively and significantly in the relationship between CSR, CR, and BE. Results of the present study have several implications for the senior management, marketing expert, administrators, and policymakers. This study expresses how CSR boosts BE and CR. Moreover, this study also indicates that trust is an important factor that enhances BE and CR.

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is attracting a lot of interest and attention in the competitive world market ( Abbas et al., 2019 ). The importance of CSR may also be revealed in the fact that firms are spending millions on CSR ( Luo and Bhattacharya, 2006 ). However, CSR is an active contributor to building a good reputation and brand equity (BE) in the Pakistani banking sector, particularly in public sector banks (PSBs). Abbas et al. (2019) , argue that CSR is a form of international private business self-regulation which aims to contribute to societal goals of a philanthropic, activist, or charitable nature by engaging in or supporting volunteering or ethically oriented practices. According to Smith (2003) , the success of an organization depends on the strategies that organizations develop to increase their sales through CSR ( Zhou et al., 2021 ). Therefore, organizations build moral capital or assets in intangible forms such as BE and corporate reputation (CR) by investing more in CSR activities. The moral capital of the company acts as an insurance policy, protecting it from negative stakeholder assessments. Companies can also increase their BE by participating in CSR ( Fatma et al., 2015 ).

According to Lai et al. (2010) , BE and CR are considered critical intangible assets to the success of a company in the financial services sector. It is also suggested that a key variable in the consumer-organization association is trust. It has been understood that trust is a factor while considering the prospects of a buyer about behavior regarding CSR perspective ( Vlachos et al., 2009 ). When customers believe an organization is trustworthy and behaves in a socially responsible manner, the evaluation and assessment of a company may be positively affected ( Edinger-Schons et al., 2019 ). In the Pakistani context, the banking sector has been growing and strengthened at a sustained pace with growth in its deposits, advances, and overall profitability. As per the quarterly performance review of the SBP banking sector report from January to June 2018, asset growth in the banking sector is 4.7%, and it stood at Rs. 19,197.1 billion, whereas deposits stood at $13,755 billion ( Zia et al., 2021 ).

The lack of attention paid with respect to contributing to society and the well-being of the community in which they operate has been noted. Furthermore, PSBs generally serve the federal government as well as various provincial governments. As a result, the government becomes its main customer, and they amuse and attract a regular customer base in order to compete in a competitive market ( Arshed et al., 2021 ). As a result, PSBs have strong roots and are well-entrenched in society, and they are seen as a key participant in achieving financial inclusion, financial literacy, and offering commercial services to the general people. However, they are also unaware of their role as CSR participants and the benefits of becoming a good corporate citizen by participating in CSR.

One possible reason is that PSBs are not cognizant that investing in CSR can greatly help build their reputation and brand equity, further attracting customers and their loyalty, thereby increasing their overall profitability. The PSB management and board of directors seem unaware and ignorant about their critical role as CSR participants and good corporate citizens, which can substantially help build a reputation and BE for their organization. Unfortunately, no such study on CSR activities for PSBs in Pakistan has been found that endorses the concept and theory of CSR initiatives that can contribute toward building reputation and brand equity. The results of such a study can significantly help to attract the attention of management and the board of directors of PSB in deciding their future course of action to CSR activities. Based on the above literature insights about CRS, trust, BE, and CR, this study proposes the following questions:

RQ1. Does CSR influence BE and CR?

RQ2. How does trust intervene between BE, CR, and CSR?

This study is organized as follows: section “Hypotheses Framing and Conceptual Framework” describes the hypotheses framing and conceptual model. Section “Research Methods” presents the research methods. Section “Results” is about the data analysis and results, whereas section “Discussions” highlights the discussion of this study. Finally, section “Conclusion” is about the conclusion, limitation, and future research directions.

Literature Review

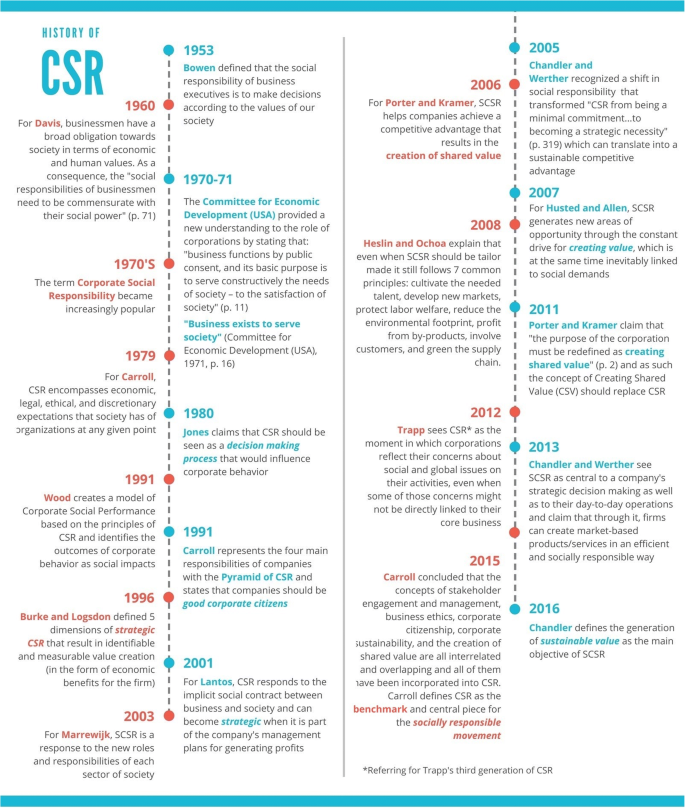

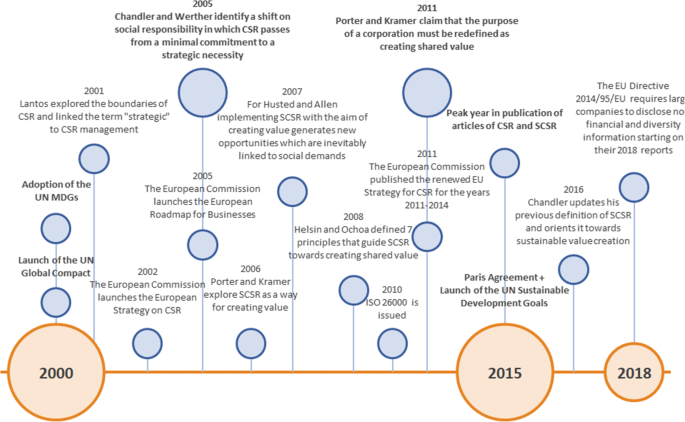

Corporate social responsibility.

Integration of the interests and business activities of societies needs to be aligned for all organizations operating in society to be beneficial for both organizations and society. According to Crane et al. (2008) , “corporate social responsibility should be considering as a strategic investment form that viewed in establishing or maintaining the corporate reputation,” and this suggests that direct and indirect execution of CSR are viewed via resource-based view (RBV) of a company when these types of leads executions and exercises impact the advantages of the firms. The manageable upper hand can be collected from these immaterial resources on the off chance that they are uncommon, important, and supreme ( Shin and Thai, 2015 ). To comprehend why firms participate in socially mindful exercises, RBV fills in as a valuable apparatus ( Branco and Rodrigues, 2006 ). Customers separate an item from two points of view, for example, vertical separation and even separation. Vertical separation implies the inclinations of a customer for buying items from socially dependable firms, in contrast with others. Vertical separation fortifies CR, enhances BE, and enables the organization to charge additional prices ( Castelo Branco and Lima Rodrigues, 2006 ). Even separation implies that the inclination of shoppers to buy certain items depends on their taste. This study does not enable the organization to charge a premium cost as it has not increased the value of CR also ( Ghaderi et al., 2019 ).

Corporate Reputation

Newburry et al. (2019) define CR as a collective perception of the past activities and beliefs of the firm regarding its future activities. Moreover, Gotsi and Wilson (2001) demonstrate that CR is the future marketing plan that will affect the internal and external stockholders of the organization. Jeffrey et al. (2019) express that CR is a reputation that brings trust and loyalty between consumers and vendors. Furthermore, a good business reputation brings a novel employee recruitment process, employee development, and employee retention. CR refers to the degree and level of a firm being considered and placed in great regard for the perceptions of its partners ( Newburry et al., 2019 ). It can also be considered to summarize all perceptions of the stakeholders toward a firm regarding how it will fulfill or exceed the anticipations ( Rettab and Mellahi, 2019 ; Hameed et al., 2021 ). Also, the reputation of a firm is governed by the indicators of the marketplace regarding its behavior, as understood by stakeholders ( Jeffrey et al., 2019 ).

Brand Equity

Brand equity is a slogan that is used in the marketing industry. The BE shows the value of a well-known brand label. So, based on this idea, organizations develop well-known brand names that increase the revenue of the organizations. Therefore, consumers believe that a well-known product is better than those products that do not have well-known names in the market. Ahmad I. et al. (2019) demonstrate that BE can be referred to as “the additional benefit or maximum worth that increased a product due to its brand name.” Moreover, Hoang et al. (2019) note that a financial approach has been utilized to examine BE. The financial approach indicators include share value fluctuations and accounting base value, where consumer-centric indicators include perpetual ( Chang, 2017 ; Raji et al., 2019 ).

Hypotheses Framing and Conceptual Framework

Corporate reputation and corporate social responsibility.

Corporate social responsibility is a self-regulatory business model that enables a firm to be socially accountable to the organization, stakeholders, and the general public ( Farid et al., 2019 ). CSR allows a company to be aware of its impact on all elements of society, including economic, social, and environmental issues, and being a socially responsible firm can help the image and brand of a company. As a result, CSR allows employees to use the resources of a company to accomplish well ( Kim et al., 2017 ). CR is considered an impalpable, value resource by any firm. It serves as a crucial factor in determining the competitive benefit, particularly in a product where diversity is negligible in the consumer ( Arikan et al., 2016 ; Baudot et al., 2019 ).

According to Benitez et al. (2017) , consumers assess and appraise new services or products launched based on their existing image in the market. Moreover, an excellent CR provides a shield against adverse customer perspectives because CR results from its business activities. In contrast, CSR initiatives are considered the best profitable method to construct a good reputation and perception in consumers and stakeholders ( Lee et al., 2017 ; Lee, 2019 ). Thus, engaging in publicly accountable activities and contributing to the well-being of a society enhances the image and reputation of a company ( Gulzar et al., 2018 ). As per Melero-Polo and López-Pérez (2017) , the consumer perspective of CSR initiatives impacts affirmatively in building CR. Forcadell and Aracil (2017) endorse that suitable social activity of firms leads to increased CR. Previous studies also indicate that CSR positively correlates with a CR ( Brammer and Pavelin, 2016 ; Gardberg et al., 2019 ; Khan et al., 2020a ). Based on the above discussion, we proposed our first hypothesis:

H1. CSR positively influences CR

Corporate Social Responsibility and Brand Equity

The concept of BE has been argued in both accounting and marketing literature, and it has underlined the necessity of a long-term perspective in brand management ( Khan et al., 2020b ). Although businesses have made substantial efforts to manage brands strategically, there is still a lack of consistent terminology and philosophy inside and between disciplines, which can obstruct communication. Accountants and marketers have varied definitions of brand equity, with the idea being described both in terms of the customer-brand connection and as something that accrues to the brand owner. Organizations build BE for their products by making them distinctive, easily recognizable, and high-quality and reliable ( Yang and Basile, 2019 ; Yang et al., 2020 ).

Prior studies highlighted that BE has a positive relationship with CSR ( Abdolvand and Charsetad, 2013 ; Lin and Chung, 2019 ; Yang and Basile, 2019 ). BE was originated from the strong interaction between brands and consumers ( Martínez and Nishiyama, 2019 ). The more consumer expectations are met or exceeded, the more the BE ( Liu and Lu, 2019 ). Similarly, the ethical behavior of a firm will lead to its reputation and a crucial indicator of brand appraisal ( Beckmann, 2007 ). Thus, the study assumes that the customer perspective of CSR initiatives may positively impact brand equity. So, we proposed our second hypothesis:

H2. CSR positively influences BE

Corporate Social Responsibility and Trust

Business ties are held together by a social glue called trust. Business partners that trust each other spend less time and energy defending themselves from being exploited, and both sides achieve greater financial results in negotiations ( Farid et al., 2020 ). When your employees know that you trust them and that they can express themselves clearly, trust becomes vital in business. They will almost certainly be more driven to be productive and work to their best potential ( Park et al., 2014 ).

Looking into previous literature, we have provided concepts to understand the relationship between CSR and trust ( Pivato et al., 2008 ; Vlachos et al., 2009 ; Park et al., 2014 ). So, the results of these studies confirm that CSR has a positive and significant relationship with trust. Moreover, the image of an organization and its norms help establish trust in the company that can be derived from its socially responsible initiatives ( Azmat and Ha, 2013 ). Organizations that are perceived as publicly answerable by consumers are inclined to have high trust levels in the eyes of the consumers ( Cheung and Pok, 2019 ; Kim, 2019 ). Hence, our third hypothesis is presented below:

H3. CSR positively influences trust.

The Mediating Effects of the Trust

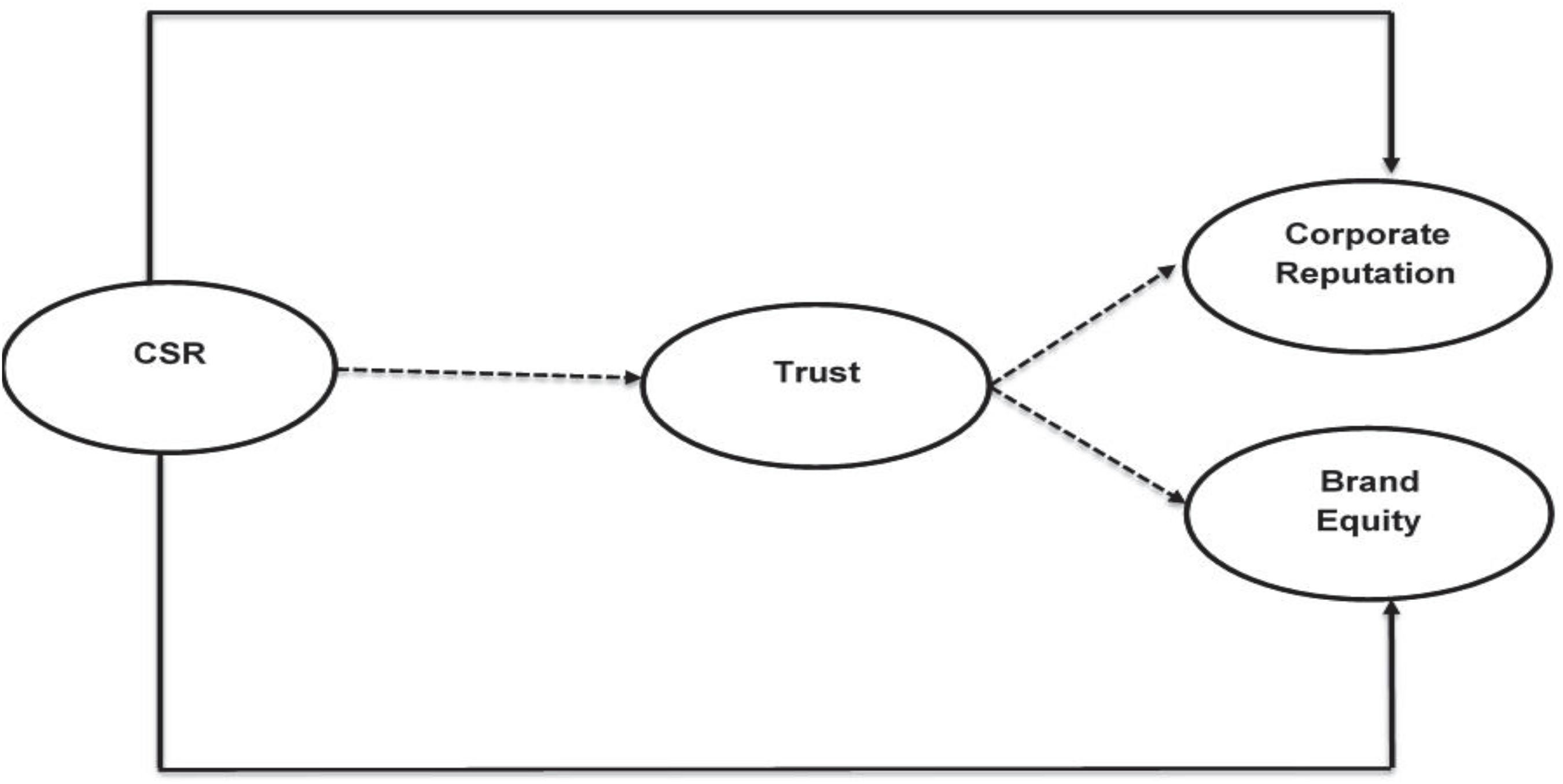

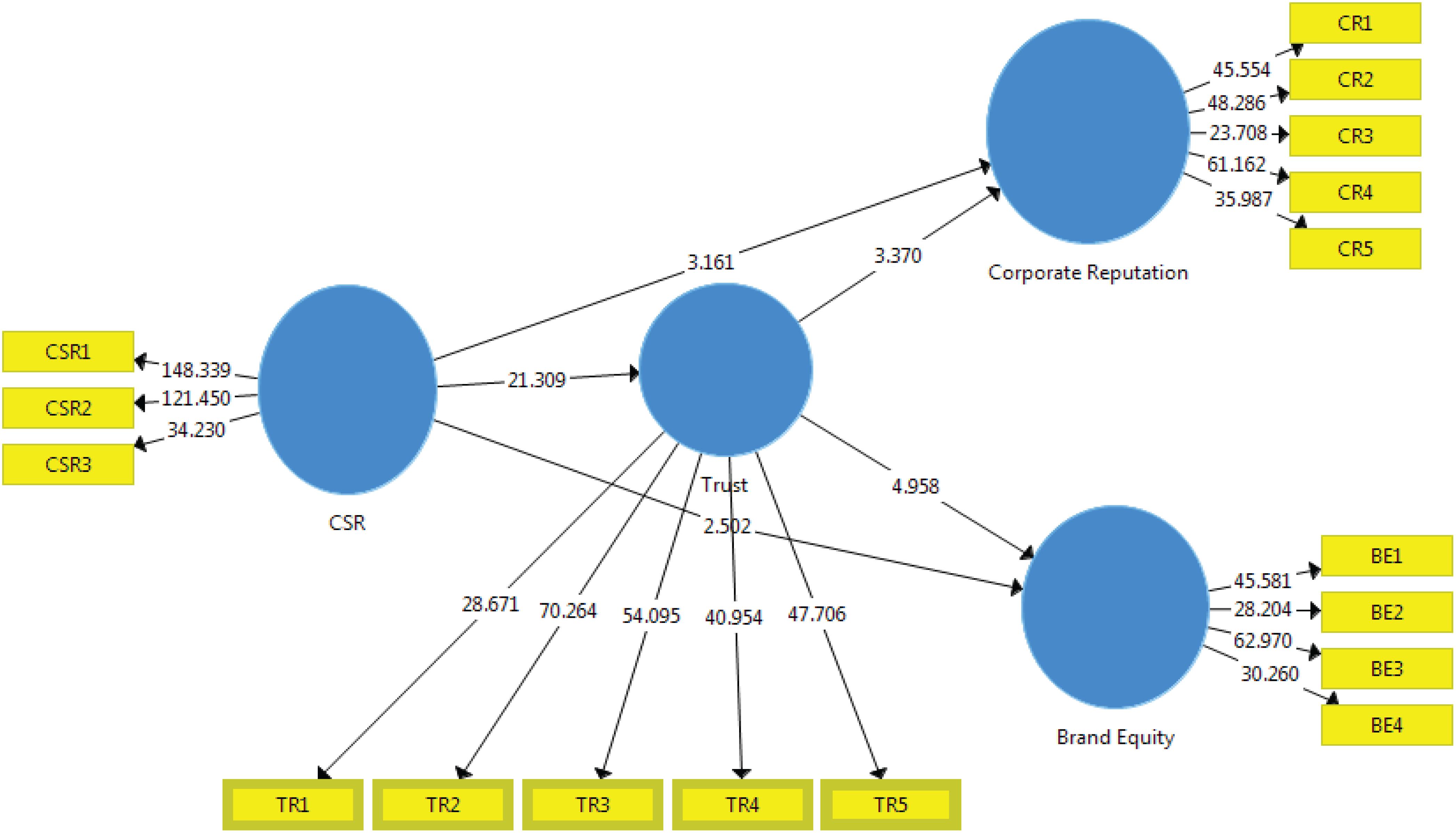

According to the study of Iglesias et al. (2018) , the benevolence base trust includes customer perception as either a firm honestly serious or concerned about the well-being and welfare of society. Similarly, another famous author, Arikan et al. (2016) indicated by the social trade hypothesis that a client trust in the direction of the firm image improves the social integration of the client association to build client responsibility toward the brand ( Nguyen and Pham, 2018 ; Kim, 2019 ; Zhao et al., 2019 ). The consumer does an overall assessment and evaluation of the image of the firm, which is drawn on their perception and information about the firm ( Joo et al., 2017 ), and trust is the forerunner to CR. Many previous studies also confirm in their results that trust is the mediator between CRS and CR and brand equity. Therefore, the literature suggests that trust is positively and significantly mediates between the CRS, CR, and brand equity. Figure 1 is presenting the conceptual model of this study. Thus, this research makes the following hypotheses:

Figure 1. Conceptual model. Solid lines show the direct relationship, and dashed lines show the indirect relationship.

H4. Trust mediates CSR and BE

H5. Trust mediates between CSR and CR

Research Methods

Research approach.

In this study, we used a questionnaire survey analysis approach. We used this approach because it is common and has a broad sample of the given population that can be contacted at a relatively low cost ( Roby et al., 2003 ; Heeringa et al., 2017 ; Wang et al., 2021 ). Hennessy and Patterson (2011) suggested that for the survey analysis, first, we should develop the research questionnaire ( Rasool et al., 2019a , b ). So, in this study, first, we designed the questionnaire to collect data.

Questionnaire Designing

This study aims to explore the influence of CSR, directly and indirectly, on CR and brand equity, using trust as a mediating variable. In this questionnaire, 17 items were used with a 5-point Likert-Scale (1 stands for “strongly disagree,” and five stands for “strongly agree”). The questionnaire is consists of five sections. The first section includes the demographic information of the respondents. The second section took insight of the customers about CSR activities. The third part of the questionnaire measured the respondent’s level of trust in the banking sector. The fourth part of the questionnaire explained the CR -related information, and the last and fifth sections encompassed acclaimed variables that measure BE dimensions. Before data collection, the authors also conducted a pilot study to check the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. The pilot study respondents suggested some modifications to the questionnaire. Therefore, the questionnaire was revised as per the recommended feedback from the pilot study respondents. So the revised questionnaire was distributed for data collection.

Variables Measurements

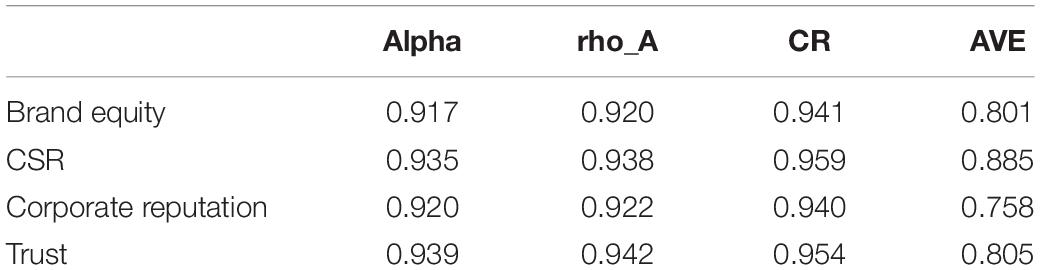

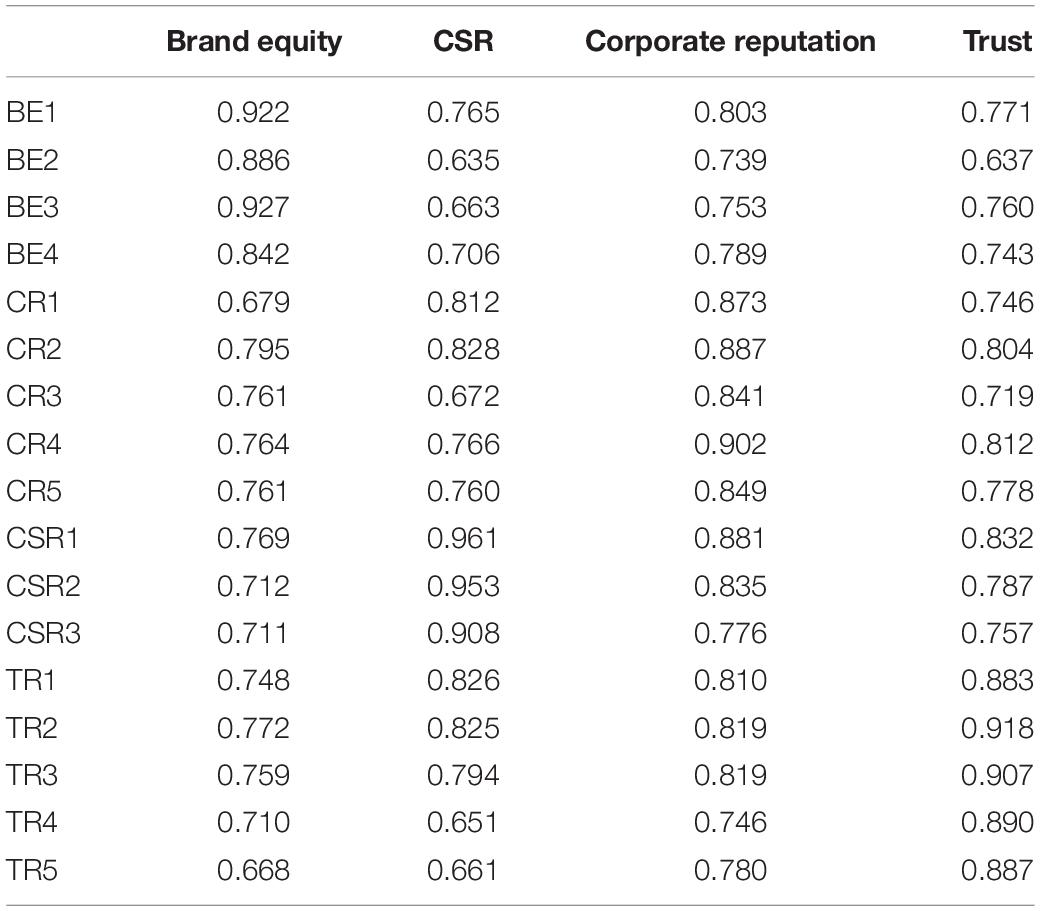

The items of CSR are adopted from López-González et al. (2019) . All items of CSR were measured with 5-points Likert-Scale (1 “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree”). The alpha of CSR was 0.920. The results indicate that the factor loading of each item is more than the standard value (0.70). So in this study, measures were considered adequate. The factor loading of each item is mentioned in Table 1 .

Table 1. Construct reliability and validity.

The items of CR were adopted by Suki and Suki (2019) . All items related to CR were measured with a 5-point Likert-Scale (1 “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree”). The alpha of CR was 0.920. The results indicate that the factor loading of each item is more than the standard value (0.70). So in this study, measures were considered adequate. The factor loading of each item is mentioned in Table 1 .

The items of BE are adopted from previous studies Çifci et al. (2016) . For the measurement of brand equity, we apply the 5-point Likert-Scale (1“strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree”). The alpha of BE was 0.917, which is appropriate. The results indicating that the factor loading of each item is more than the standard value (0.70). So, the alpha values met the threshold criteria. The factor loading of each item is mentioned in Table 1 .

We use to trust the items developed by Tzempelikos and Gounaris (2017) . All items were measured on a 5-points Likert-Scale (1“strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree”). The alpha of trust was 0.939, which is acceptable. The results indicate that the factor loading of each item is more than the standard value (0.70). So, the alpha values met the threshold criteria. The factor loading of each item is mentioned in Table 1 .

Data Collection

The data was collected using self-administered questionnaires from the consumers of banking sectors living in Lahore city, the capital of Punjab province of Pakistan. The banking sector consumers for this research refer to those people who are aged above 18 years and have an account in any bank during the survey. Data were collected between 2018 and 2019. This survey was conducted during the working hours of the banks. A non-probabilistic sampling technique with a combination of convenience sampling techniques was used for this research to measure demographic variables like respondent gender, qualification, age, and income. Above all, variables ensure that the sample signifies the sociodemographic features of the present population. At present, for this study, initially, a total of 550 survey instruments were circulated, and from these, 342 questionnaires were received and 23 castoffs due to incomplete information that leaves us with 319 responses. Also, 10 unusable ware responses were identified, leaving 309 responses for the final analysis of this research. The majority of respondents in this research were men, around 57.09%, and women 46.91% aged between 20 and 60 years. Most of the audience holds a bachelor’s degree 950 (16%) and belongs to middle-income families earning $200–690 monthly (43.89%). For more detailed analysis, all variables were inspected for data entry errors, missing values, and the fit between distributions using the software SmartPLS.

The relationships drawn in the conceptual model were examined using the SEM method. The rationale for choosing SEM over the covariance-based SEM approach is that it is less vulnerable to sample size.

The degree to which all of the multiple elements of the model are used to test its convergent validity ( Kura, 2017 ), shown in Table 2 . For this, the threshold value should be >0.6 ( Hair et al., 2016 ). Since all of our values met the threshold requirement, each data collection indicator is valid.

Table 2. Factor loading.

The degrees that display actuality or affirm convergent validity are referred to as average variance extracted (AVE) ( Ahmad S. et al., 2019 ). The AVE value should be larger than 0.5, according to Fornell and Larcker (1981) . The reliability of structures has been demonstrated using composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha value. The stability of structures has been measured using composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha value. According to Hair Jr. and Sarstedt, it should have a value larger than 0.7; many of the variables in our sample have values that are greater than or equal to the threshold value.

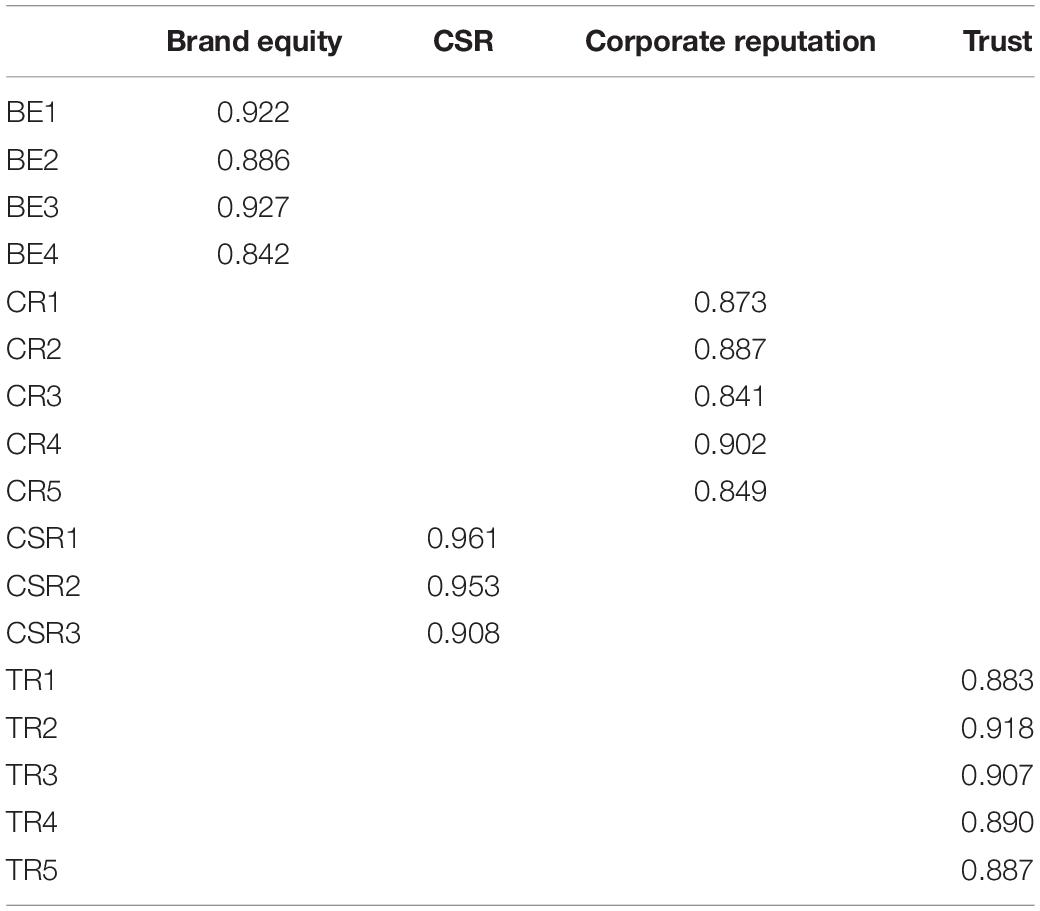

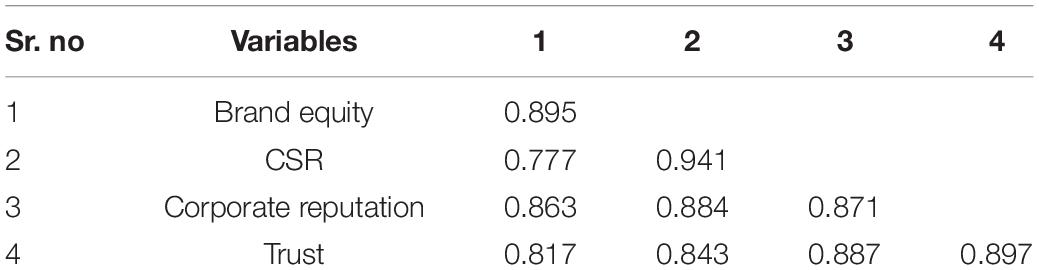

Discriminant validity demonstrates that objects and their constructs have distinct meanings ( Hair et al., 2016 ). Its value is higher than 0.6 in Table 3 , which represents valid results, while negative results indicate the reverse.

Table 3. Discriminant validity of constructs.

Cross loading is a technique for demonstrating that the loading value of the indicator is highest with one construct and lowest with another ( Hair et al., 2017 ). Table 4 reveals that the values of indicators are adequate for their construct but not for others.

Table 4. Cross loading.

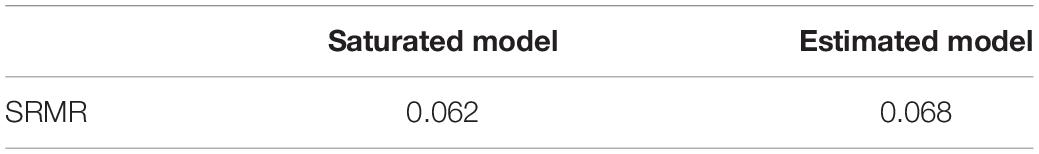

The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), which is based on converting both the sample covariance matrix and the predicted covariance matrix into correlation matrices, is a measure of the mean absolute value of the covariance residuals. The difference between the observed correlation and the model indicated correlation matrix is defined as the SRMR. As a result, it is possible to use the average size of the differences between observed and anticipated correlations as an absolute measure of (model) fit. A good fit is defined as a value <0.10 or 0.08 ( Hu and Bentler, 1998 ). The SRMR is a goodness of fit metric for PLS-SEM introduced by Henseler et al. (2014) that may be used to avoid model misspecification. The model is shown by values in Table 5 (0.068), which is less than the predefined threshold. So, the model is fitted.

Table 5. Model fit (standardized root means square residual).

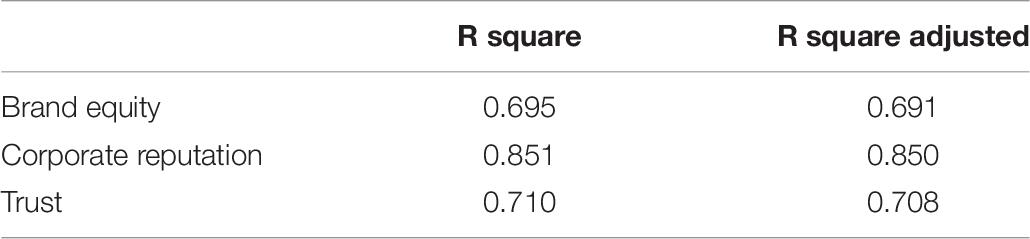

R Square’s partial least square regression model shows us how much variation is explained by independent variables on the dependent variable and model strength. The goodness of fit of the model is shown in this analysis. It should have a value >0.3. The coefficient of determination (R square) values are >0.3, which is greater than the threshold value, indicating the goodness of the model in Table 6 .

Table 6. R square—R 2 .

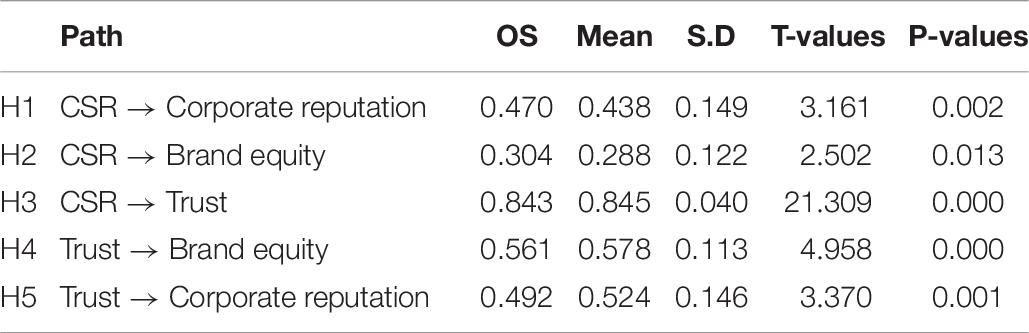

Table 7 presents the value of CSR on CR as 3.161, which means acceptance of the H1 hypothesis because it forecasts that the CRS activities positively affect CR as this path that leads toward the CRS is significant statistically at 0.05 level. Thus, H1 confirms that socially responsible activities lead toward positive CR from the perspective of the consumer This finding also supports the previous studies on the subject where Nguyen and Nguyen (2017) stated that CSR positively correlates with CR. H2 suggested that CSR also has an affirmative effect on BE. The value of the direct impact of CSR on CR is 3.161, which is positive and supports H2. The findings are also aligned with the work of Marín et al. (2016) . H3 suggested that CSR activities and initiatives directly affect the trust of consumers in brand image. Its value that ultimately CSR has an effect on trust also shows the positive relationship with CRS, which supports H3. The hypothesis is found to be significant at the 0.05 level. H4 claims that trust plays a mediating role between CSR and CR, while H5 claims that trust plays a partial mediating role between CSR and BE. Both have a positive effect and significant values, which means acceptance of H4 and H5, respectively.

Table 7. Path model results (direct and indirect).

Figure 2 depicts the relationship between all variables and mediation results. The inner model shows the relationship between the variables, whereas the outer model shows the factor loading values for each indicator. The connection between CSR and CR is 3.161, which means that the one-unit increase of CSR will positively impact CR by 3.161 points. By a 100% increase in CSR activities, it will increase CR by 316.1%. Similarly, CSR and BE connection values are 2.502, which also shows strong and positive relationships and that a one-unit increase in CSR initiatives will increase the BE of the company by 2.502 points. The mediating effect of trust shows that the mediating effect of Trust on CSR and CR as a consumer has a positive impact. Similarly, Figure 2 demonstrates the mediating impact of trust on the positive and robust relationship between CSR and BE.

Figure 2. Theoretical constructs with R2 values.

The aim of this study was to investigate how CSR, directly and indirectly, influences CR and BE, using trust as a mediating variable. Previously, such studies were conducted in developed countries, such as the United States, United Kingdom, and other western countries. However, a limited amount of findings are argued and their findings are presented on emerging countries like Pakistan. So, the limited studies on the emerging countries have still shown the scarcity of findings from the banking sector perspective. Authors believe that financial institutions ought to identify their significant roles in the socio-economic development of any country. To the best of the knowledge of the author, this research is among the earliest research paradigms to investigate the impact of CSR on CR and BE in the Pakistani organizational context, especially by considering trust as a mediating variable. So, the exploration of this study is the role of trust as a mediating instrument. CSR activities help in the cumulative status of a corporate organization amongst its customers, employees, and stakeholders.

First, we focused on the direct relationship between CSR and CR and BE. The results show that CSR has a positive and significant impact on CR and BE, supporting our hypotheses H1 and H2. Prior studies have shown that CSR has a positive relationship with CR and BE ( Hsu, 2012 ; Fatma et al., 2015 ; Lin and Chung, 2019 ; Lu et al., 2019 ). The finding of Hur et al. (2018) also support our results. They express in their study that CSR is known to be a standout amongst the best methods for promotion. There is just restricted research contemplating the impacts of CSR on advertising results. Therefore, this research indicates that CSR enhances CR and BE in the banking sector of Pakistan. Similarly, the RBV supports our study in the relationship between CRS, CR, and BE. Moreover, Rea et al. (2014) also suggest in their research that RBV supports the direct relationship among CSR, CR, and BE.

Second, this study depicts the positive and direct effects of CRS on trust, which supports Hypothesis 3. The finding of this study supports the research conducted by Choi and La (2013) , which concludes that CSR significantly influences customer trust. Similarly, Park et al. (2014) examine the relationship between CSR and customer trust in Korean organizations, and the outcomes of their study confirmed that CSR is directly connected with customer trust. Thus, CRS has positively influenced customer trust in the banking sector of Pakistan. So, in case Pakistani banks want to create a positive image in the minds of their customers, they should focus on the CSR of the society that will affect the trust of the customer on their products.

Third, in this study, we test the mediated effect of trust between CSR, CR, and BE. It also translates significant results, which is a novel and original contribution in emerging countries like Pakistan, which supports H4 and H5. The mediated results support the findings of previous studies ( Pivato et al., 2008 ; Fatma et al., 2015 ; Jalilvand et al., 2017 ). Forcadell and Aracil (2017) and Vlachos et al. (2009) inspected the mediating role of consumer satisfaction and trust among CSR and CR; however, they confirm in their study that trust is positively and significantly mediated between the CSR and CR. Further, Chang and Yeh (2017) proposed in their study that CSR has a positive relationship with BE using trust as a mediating variable. The outcomes of their study confirm that trust is intervening between CSR and brand equity. So, the outcomes of this research also indicated that customer trust as a critical variable positively affects CRS, CR, and BE. These results have significant inferences for PSBs in particular and private banks in Pakistan and advise that CSR activities may help in Constructing CR and BE.

The results of this study confirmed the linkages among CSR, CR, and BE in the banking sector of Pakistan. Moreover, the finding of this research indicates that in the direct relationship, CSR positively influences CR and brand equity. The outcome of this study also confirms that trust positively and significantly mediates between CSR, CR, and brand equity. Furthermore, the outcomes confirmed that CSR has a positive and significant relationship with CR and brand equity.

This study highlight that the PSBs spend their resources on CSR activities to lead to significant advantages for partners and society. While participating in CSR exercises, PSBs will gain a progressively positive discernment and a reasonable frame of mind of their partners and stakeholders. Along with the fruitful insights, it is more important for banking and other industries to invest in the CSR interventions that can contribute to gain sustainable competitive advantage. Similarly, the investment in CSR is also fruitful for both stakeholders and the community. The exact outcomes of the examination show that CSR has an immediate positive and circuitous impact on CR and BE because findings here reveal that CSR indirectly influences CR as mediated by trust. Furthermore, discoveries uncover that the backhanded effects of CSR exercise on CR while mediated by trust. The multifaceted CSR demonstrated as a CR and BE are more viable explanations behind CSR exercises. Then again, buyer trust might be seen as a result of firms captivating CSR exercises. The solid connection between CSR activities and CR proves that an organization occupied with socially dependable exercises can anticipate different helpful results.

Implications, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

Managerial implication.

This research was conducted in the banking sector of Pakistan. The findings indicate some practical implications for the banking sector of Pakistan that could increase the organizational CR and BE through CSR. First, the managers need to create an environment of CSR activities. Those planning to do while establishing and maintaining strong relationships with firms and consumers through these CSR activities are more likely to create positive outcomes such as BE and CR ( Javeed and Lefen, 2019 ). Second, managers, specifically in banking organizations should pay more attention to CSR activities and spend more of their resources on these activities. In this way, customers perceive the firm as more socially responsible and trustworthy than any other firm while considering it more favorably. This study shows that the results in a well-known or good reputation will increase brand equity. Third, the banking organizations and other investment-related companies also pay more close attention to their reputation in the minds of the consumers because it plays a critical role in evaluating the performance of the firm. Therefore, the banking organizations and investment-related firms should expect to enhance their brand while considering various socially responsible initiatives that positively impact society. The finding provides the most important insights to firm managers about their critical position in developing CSR as a customer brand partnership from their marketing viewpoints. They can take more effort to maintain deep trust between customers because it has been found that most consumers view a firm as more trustworthy when it is associated with some social problem.

Limitation and Future Research Direction

This research has some limitations that may affect the generalization of its findings. First, due to time constraints and scared resources, the nature of our study was cross-sectional instead of a longitudinal design. Therefore, we recommend future researchers conduct a longitudinal mode study using CSR predictors on industrial BE and CR for more generalized results. Second, the data is collected from the second biggest city of Pakistan, an expensive city in Pakistan, affecting the buyers buying power. Such research will conduct in four to five different cities of the country, which will have generalized the study results. Third, the data was collected from the banking sector, which might cause common method bias. As the job nature of the target population is different from each other, future studies should focus on individuals who have similar jobs. In the future, such kind of study will explore the relationship between CSR and CR using the well-being of the customer as a mediating variable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

MS and MA conceived the idea of the study. SR worked on the research methodology and helped in drafting the manuscript. MM worked on the results and analysis, and interpretation of model results. TO supervised the project and intensively edited the language of the manuscript. YZ approved and read the final manuscript and participated in the critical appraisal of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71673179).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbas, J., Mahmood, S., Ali, H., Ali Raza, M., Ali, G., Aman, J., et al. (2019). The effects of corporate social responsibility practices and environmental factors through a moderating role of social media marketing on sustainable performance of business firms. Sustainability 11:3434. doi: 10.3390/su11123434

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Abdolvand, M., and Charsetad, P. (2013). Corporate social responsibility and brand equity in industrial marketing. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 3:273. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i9/208

Ahmad, I., Shahzad, K., and Gul, A. (2019). Mediating role of customer satisfaction between corporate social responsibility and customer-based brand equity. Bus. Econ. Rev. 11, 123–144. doi: 10.22547/BER/11.1.6

Ahmad, S., Hussain, A., and Batool, A. (2019). Path analysis of genuine leadership and job life of teachers. J. Educ. Sci. 6, 1–14.

Google Scholar

Arikan, E., Kantur, D., Maden, C., and Telci, E. E. (2016). Investigating the mediating role of corporate reputation on the relationship between corporate social responsibility and multiple stakeholder outcomes. Qual. Quant. 50, 129–149. doi: 10.1007/s11135-014-0141-5

Arshed, N., Ahmad, W., Munir, M., and Farooqi, A. (2021). Estimation of national stress index using socioeconomic antecedents–a case of MIMIC model. Psychol. Health Med. Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1903051

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Azmat, F., and Ha, H. (2013). Corporate social responsibility, customer trust, and loyalty—perspectives from a developing country. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 55, 253–270. doi: 10.1002/tie.21542

Baudot, L., Johnson, J. A., Roberts, A., and Roberts, R. W. (2019). Is corporate tax aggressiveness a reputation threat? corporate accountability, corporate social responsibility, and corporate tax behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 163, 197–215. doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04227-3

Beckmann, S. C. (2007). Consumers and corporate social responsibility: matching the unmatchable? Australas. Mark. J. 15, 27–36. doi: 10.1016/S1441-3582(07)70026-5

Benitez, J., Ruiz, L., Llorens, J., and Castillo, A. (2017). “Corporate social responsibility, employer reputation, and social media capability: an empirical investigation,” in Proceedings of the 25th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS) (Guimarães).

Brammer, S. J., and Pavelin, S. (2016). “Corporate reputation and corporate social responsibility,” in A Handbook of Corporate Governance and Social Responsibility , eds P. G. Aras and P. D. Crowther (Famham: Gower Publishing).

Branco, M. C., and Rodrigues, L. L. (2006). Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 69, 111–132. doi: 10.1007/s10551-006-9071-z

Castelo Branco, M., and Lima Rodrigues, L. (2006). Communication of corporate social responsibility by Portuguese banks: a legitimacy theory perspective. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 11, 232–248. doi: 10.1108/13563280610680821

Chang, H.-H. (2017). Consumer socially sustainable consumption: the perspective toward corporate social responsibility, perceived value, and brand loyalty. J. Econ. Manag. 13, 167–191.

Chang, Y.-H., and Yeh, C.-H. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and customer loyalty in intercity bus services. Transport Policy 59, 38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.07.001

Cheung, A. W., and Pok, W. C. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and provision of trade credit. J. Contemporary Account. Econ. 2019:100159. doi: 10.1016/j.jcae.2019.100159

Choi, B., and La, S. (2013). The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and customer trust on the restoration of loyalty after service failure and recovery. J. Serv. Mark. 27, 223–233. doi: 10.1108/08876041311330717

Çifci, S., Ekinci, Y., Whyatt, G., Japutra, A., Molinillo, S., and Siala, H. (2016). A cross validation of consumer-based brand equity models: driving customer equity in retail brands. J. Bus. Res. 69, 3740–3747. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.066

Crane, A., McWilliams, A., Matten, D., Moon, J., and Siegel, D. S. (2008). “The corporate social responsibility agenda,” in The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility , eds A. McWilliams, D. E. Rupp, and D. S. Seigel (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211593.003.0001

Edinger-Schons, L. M., Lengler-Graiff, L., Scheidler, S., and Wieseke, J. (2019). Frontline employees as corporate social responsibility (CSR) ambassadors: a quasi-field experiment. J. Bus. Ethics 157, 359–373. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-3790-9

Farid, T., Iqbal, S., Khan, A., Ma, J., Khattak, A., Naseer, et al. (2020). The impact of authentic leadership on organizational citizenship behaviors: the mediating role of affective-and cognitive-based trust. Front. Psychol. 11:1975. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01975

Farid, T., Iqbal, S., Ma, J., Castro-González, S., Khattak, A., and Khan, M. K. (2019). Employees’ perceptions of CSR, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior: the mediating effects of organizational justice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:1731. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16101731

Fatma, M., Rahman, Z., and Khan, I. (2015). Building company reputation and brand equity through CSR: the mediating role of trust. Int. J. Bank Mark. 33, 840–856. doi: 10.1108/IJBM-11-2014-0166

Forcadell, F. J., and Aracil, E. (2017). European banks’ reputation for corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 24, 1–14. doi: 10.1002/csr.1402

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Gardberg, N. A., Zyglidopoulos, S. C., Symeou, P. C., and Schepers, D. H. (2019). The impact of corporate philanthropy on reputation for corporate social performance. Bus. Soc. 58, 1177–1208. doi: 10.1177/0007650317694856

Ghaderi, Z., Mirzapour, M., Henderson, J. C., and Richardson, S. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and hotel performance: a view from Tehran, Iran. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 29, 41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.10.007

Gotsi, M., and Wilson, A. M. (2001). Corporate reputation: seeking a definition. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 6, 24–30. doi: 10.1108/13563280110381189

Gulzar, M., Cherian, J., Sial, M., Badulescu, A., Thu, P., Badulescu, D., et al. (2018). Does corporate social responsibility influence corporate tax avoidance of chinese listed companies? Sustainability 10:4549. doi: 10.3390/su10124549

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., and Sarstedt, M. (2016). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., and Gudergan, S. P. (2017). Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-05542-8_15-1

Hameed, K., Arshed, N., Yazdani, N., and Munir, M. (2021). Motivating business towards innovation: a panel data study using dynamic capability framework. Technol. Soc. 65:101581. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101581

Heeringa, S. G., West, B. T., and Berglund, P. A. (2017). Applied Survey Data Analysis. London: Chapman and Hall.

Hennessy, J. L., and Patterson, D. A. (2011). Computer Architecture: a Quantitative Approach. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T. K., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D. W., et al. (2014). Common beliefs and reality about PLS: comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 17, 182–209. doi: 10.1177/1094428114526928

Hoang, H. T., Wang, F., Van Ngo, Q., and Chen, M. (2019). Brand equity in social media-based brand community. Mark. Intelligence Plann. 38, 325–339. doi: 10.1108/MIP-01-2019-0051

Hsu, K.-T. (2012). The advertising effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and brand equity: evidence from the life insurance industry in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 109, 189–201. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-1118-0

Hu, L.-T., and Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 3, 424–453. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

Hur, W. M., Kim, H., and Kim, H. K. (2018). Does customer engagement in corporate social responsibility initiatives lead to customer citizenship behaviour? the mediating roles of customer-company identification and affective commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib Environ. Manag. 25, 1258–1269. doi: 10.1002/csr.1636

Iglesias, O., Markovic, S., Bagherzadeh, M., and Singh, J. J. (2018). Co-creation: a key link between corporate social responsibility, customer trust, and customer loyalty. J. Bus. Ethics 163, 151–166. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-4015-y

Jalilvand, M. R., Nasrolahi Vosta, L., Kazemi Mahyari, H., and Khazaei Pool, J. (2017). Social responsibility influence on customer trust in hotels: mediating effects of reputation and word-of-mouth. Tour. Rev. 72, 1–14. doi: 10.1108/TR-09-2016-0037

Javeed, S., and Lefen, L. (2019). An analysis of corporate social responsibility and firm performance with moderating effects of CEO power and ownership structure: a case study of the manufacturing sector of Pakistan. Sustainability 11:248. doi: 10.3390/su11010248

Jeffrey, S., Rosenberg, S., and McCabe, B. (2019). Corporate social responsibility behaviors and corporate reputation. Soc. Responsib. J. 15, 395–408. doi: 10.1108/SRJ-11-2017-0255

Joo, J., Eom, M., and Shin, M. (2017). Finding the missing link between corporate social responsibility and firm competitiveness through social capital: a business ecosystem perspective. Sustainability 9:707. doi: 10.3390/su9050707

Khan, T. M., Bai, G., Fareed, Z., Quresh, S., Khalid, Z., and Khan, W. A. (2020a). CEO tenure, CEO compensation, corporate social & environmental performance in China. The moderating role of coastal and non-coastal areas. Front. Psychol. 11:3815.

Khan, T. M., Gang, B., Fareed, Z., and Yasmeen, R. (2020b). The impact of CEO tenure on corporate social and environmental performance: an emerging country’s analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27.

Kim, H. L., Rhou, Y., Uysal, M., and Kwon, N. (2017). An examination of the links between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its internal consequences. Int. J. Hospital. Manag. 61, 26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.10.011

Kim, S. (2019). The process model of corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication: CSR communication and its relationship with consumers’ CSR knowledge, trust, and corporate reputation perception. J. Bus. Ethics 154, 1143–1159. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3433-6

Kura, K. M. (2017). Theorizing a boundary condition of the relationship between human resource management practices and turnover intention: a proposed model. J. Innov. Sustainab. 8, 3–11. doi: 10.24212/2179-3565.2017v8i1p3-11

Lai, C.-S., Chiu, C.-J., Yang, C.-F., and Pai, D.-C. (2010). The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: the mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 95, 457–469. doi: 10.1007/s10551-010-0433-1

Lee, C.-Y. (2019). Does corporate social responsibility influence customer loyalty in the Taiwan insurance sector? the role of corporate image and customer satisfaction. J. Promotion Manag. 25, 43–64. doi: 10.1080/10496491.2018.1427651

Lee, J., Kim, S.-J., and Kwon, I. (2017). Corporate social responsibility as a strategic means to attract foreign investment: evidence from Korea. Sustainability 9:2121. doi: 10.3390/su9112121

Lin, M. S., and Chung, Y. K. (2019). Understanding the impacts of corporate social responsibility and brand attributes on brand equity in the restaurant industry. Tour. Econ. 25, 639–658. doi: 10.1177/1354816618813619

Liu, M., and Lu, W. (2019). Corporate social responsibility, firm performance, and firm risk: the role of firm reputation. Asia Pacific J. Account. Econ. 27, 2991–3005. doi: 10.1080/16081625.2019.1601022

López-González, E., Martínez-Ferrero, J., and García-Meca, E. (2019). Corporate social responsibility in family firms: a contingency approach. J. Clean. Prod. 211, 1044–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.251

Lu, J., Ren, L., He, Y., Lin, W., and Streimikis, J. (2019). Linking corporate social responsibility with reputation and brand of the firm. Amfiteatru Econ. 21, 442–460.

Luo, X., and Bhattacharya, C. B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Market. 70, 1–18. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.70.4.1

Marín, L., Cuestas, P. J., and Román, S. (2016). Determinants of consumer attributions of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 138, 247–260. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2578-4

Martínez, P., and Nishiyama, N. (2019). Enhancing customer-based brand equity through CSR in the hospitality sector. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Administration 20, 329–353. doi: 10.1080/15256480.2017.1397581

Melero-Polo, I., and López-Pérez, M. E. (2017). Identifying links between corporate social responsibility and reputation: some considerations for family firms. J. Evol. Stud. Bus. 2, 191–230.

Newburry, W., Deephouse, D. L., and Gardberg, N. A. (2019). “Global aspects of reputation and strategic management,” in Global Aspects of Reputation and Strategic Management , eds D. Deephouse, N. Gardberg, and W. Newburry (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited). doi: 10.1108/S1064-4857201918

Nguyen, H. N., and Pham, L. X. (2018). The relationship between country-of-origin image, corporate reputation, corporate social responsibility, trust and customers’ purchase intention: evidence from vietnam. J. Appl. Econ. Sci. 13, 498–509.

Nguyen, T. D., and Nguyen, V. T. (2017). “Promoting organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviors in vietnamese enterprises: the influence of corporate reputation,” in Paper Presented at the The 4th International Conference on Finance and Economics (Vietnam).

Park, J., Lee, H., and Kim, C. (2014). Corporate social responsibilities, consumer trust and corporate reputation: South Korean consumers’ perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 67, 295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.05.016

Pivato, S., Misani, N., and Tencati, A. (2008). The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust: the case of organic food. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 17, 3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8608.2008.00515.x

Raji, R. A., Mohd Rashid, S., and Mohd Ishak, S. (2019). Consumer-based brand equity (CBBE) and the role of social media communications: qualitative findings from the Malaysian automotive industry. J. Mark. Commun. 25, 511–534. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2018.1455066

Rasool, S. F., Maqbool, R., Samma, M., Zhao, Y., and Anjum, A. (2019a). Positioning depression as a critical factor in creating a toxic workplace environment for diminishing worker productivity. Sustainability 11:2589. doi: 10.3390/su11092589

Rasool, S. F., Samma, M., Wang, M., Zhao, Y., and Zhang, Y. (2019b). How human resource management practices translate into sustainable organizational performance: the mediating role of product, process and knowledge innovation. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 12, 1009–1025. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S204662

Rea, B. J., Wang, Y., and Stoner, J. (2014). When a brand caught fire: the role of brand equity in product-harm crisis. J. Product Brand Manag. 23, 532–542. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-01-2014-0477

Rettab, B., and Mellahi, K. (2019). “CSR and corporate performance with special reference to the middle east,” in Practising CSR in the Middle East , eds B. Rettab and K. Mellahi (Berlin: Springer), 101–118. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-02044-6_6

Roby, D. D., Lyons, D. E., Craig, D. P., Collis, K., and Visser, G. H. (2003). Quantifying the effect of predators on endangered species using a bioenergetics approach: caspian terns and juvenile salmonids in the Columbia River estuary. Can. J. Zool. 81, 250–265. doi: 10.1139/z02-242

Shin, Y., and Thai, V. V. (2015). The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer satisfaction, relationship maintenance and loyalty in the shipping industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 22, 381–392. doi: 10.1002/csr.1352

Smith, N. C. (2003). Corporate social responsibility: not whether, but how. California Manag. Rev. 45, 52–76. doi: 10.2307/41166188

Suki, N. M., and Suki, N. M. (2019). “Correlations between awareness of green marketing, corporate social responsibility, product image, corporate reputation, and consumer purchase intention,” in Corporate Social Responsibility: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications , eds Management Association and Information Resources (Pennsylvania: IGI Global), 143–154. doi: 10.4018/978-1-5225-6192-7.ch008

Tzempelikos, N., and Gounaris, S. (2017). “A conceptual and empirical examination of key account management orientation and its implications–the role of trust,” in The Customer is NOT Always Right? Marketing Orientationsin a Dynamic Business World , ed C. L. Campbell Berlin: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-50008-9_185

Vlachos, P. A., Tsamakos, A., Vrechopoulos, A. P., and Avramidis, P. K. (2009). Corporate social responsibility: attributions, loyalty, and the mediating role of trust. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 37, 170–180. doi: 10.1007/s11747-008-0117-x

Wang, B., Rasool, S. F., Zhao, Y., Samma, M., and Iqbal, J. (2021). Investigating the nexus between critical success factors, despotic leadership, and success of renewable energy projects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-16441-6

Yang, J., and Basile, K. (2019). The impact of corporate social responsibility on brand equity. Mark. Intelligence Planning 37, 2–17. doi: 10.1108/MIP-02-2018-0051

Yang, J., Basile, K., and Letourneau, O. (2020). The impact of social media platform selection on effectively communicating about corporate social responsibility. J. Market. Comm. 26, 65–87.

Zhao, Z., Meng, F., He, Y., and Gu, Z. (2019). the influence of corporate social responsibility on competitive advantage with multiple mediations from social capital and dynamic capabilities. Sustainability 11:218. doi: 10.3390/su11010218

Zhou, X., Rasool, S. F., Yang, J., and Asghar, M. Z. (2021). Exploring the relationship between despotic leadership and job satisfaction: the role of self efficacy and leader–member exchange. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:5307. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105307

Zia, M. A., Abbas, R. Z., and Arshed, N. (2021). Money laundering and terror financing: issues and challenges in Pakistan. J. Money Laundering Control Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1108/JMLC-11-2020-0126

Keywords : corporate social responsibility (C.S.R.), trust, corporate reputation behavior, brand equity, social perception

Citation: Zhao Y, Abbas M, Samma M, Ozkut T, Munir M and Rasool SF (2021) Exploring the Relationship Between Corporate Social Responsibility, Trust, Corporate Reputation, and Brand Equity. Front. Psychol. 12:766422. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.766422

Received: 29 August 2021; Accepted: 01 October 2021; Published: 10 November 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Zhao, Abbas, Samma, Ozkut, Munir and Rasool. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Madeeha Samma, [email protected] ; Samma Faiz Rasool, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

CSR Reputation and Firm Performance: A Dynamic Approach

- Original Paper

- Published: 08 November 2018

- Volume 163 , pages 619–636, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Stewart R. Miller 1 ,

- Lorraine Eden 2 &

9257 Accesses

105 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Many countries have regulations that require firms to engage in minimum levels of corporate social (CS) activities in areas such as the environment and social welfare. In this paper, we argue that changes in a firm’s compliance with CS regulations are reflected in its reputation for corporate social responsibility (CSR), which affects the firm’s performance. The performance impacts depend on whether the firm’s CSR reputation in the current and prior periods is positive (i.e., the firm exceeds CS regulations), neutral (the firm meets CS regulations), or negative (the firm fails to comply with CS regulations). Our theoretical framework draws on the reputation literature and on the concepts of recency bias, which weights the present more heavily than the past, and negativity bias, which weights negative assessments more heavily than neutral or positive assessments. We test our hypotheses on a sample of 7317 banks over 1992–2007 where we compare a bank’s return on assets (ROA) with its current and prior compliance ratings under the U.S. Community Reinvestment Act. We find that changes in CSR reputation have predictable, asymmetric, and sizeable impacts on firm performance. For example, for an average bank with $1 billion in assets, gaining a positive CSR reputation translates into a rise in profits of 4.04%; gaining a negative CSR reputation results in a drop in profits of − 7.8%.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of four types of corporate social performance on reputation and financial performance.

The Impact of Corporate Reputation Ratings on CEO Compensation Under Diverse Economic Conditions

Does CSR reputation mitigate the impact of corporate social irresponsibility?

http://www.macleans.ca/work/bestcompanies/top-50-socially-responsible-corporations-2014/ .

http://www.frontstream.com/the-most-socially-responsible-companies-of-2015-part-one/ .

http://www.forbes.com/pictures/efkk45fdekj/the-10-companies-with-the-best-csr-reputations-2/#2dfda10377ae .

We acknowledge that the actions that result in gaining a positive CSR reputation may be driven by altruism or other motives. At no point do we attempting to distinguish the actual motives of corporate leaders, which are difficult to observe, if not virtually impossible to distinguish. Rather, we focus on a firm’s observable investment in corporate social activities and institutional actors’ perceptions of the focal firm’s actions.

We acknowledge prior studies of autobiographical memory reveal evidence of a fading effect bias, in which people more quickly forget negative experiences than positive ones (Ritchie et al. 2006 ), this effect is unlikely in a professional setting with high task complexity.

Note we do not compare movements toward a neutral CSR reputation (that is, compliance with CS regulations) because we hypothesize in both cases (H1a and H2b) that the impact should be nonsignificant.

We therefore do not consider the case where a firm spends so far in excess of CS regulations that evaluators and stakeholders view its behavior as unsafe and unsound. In such a case, the firm would be socially responsive but its excessive behavior would have a negative reputation effect.

There are two noncompliant categories, “Needs to improve” and “Substantial noncompliance.” The second was issued so rarely that we combined them into the “Noncompliant” category.

https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/resources/director/presentations/cra.pdf .

Setting α (the probability of Type I error) and β (the probability of Type II error) equal to .05 means that the probability of our not finding a significant effect when it is actually present is equal to the probability of incorrectly rejecting the null.

Goldman-Carter ( 1992 ) discussed diluted regulations with respect to a different CSR domain – environmental protection.

Amel, D., & Rhoades, S. (1988). Strategic groups in banking. Review of Economics and Statistics, 70 , 685–689.

Article Google Scholar

Arlow, P., & Gannon, M. (1982). Social responsiveness, corporate structure, and economic performance. Academy of Management Review, 7 (2), 235–241.

Arnold, V., Collier, P., Leech, S., & Sutton, S. (2000). The effect of experience and complexity on order and recency bias in decision making by professional accountants. Accounting and Finance, 40 , 109–134.

Balmer, J. M. T. (2010). The BP Deepwater Horizon debacle and corporate brand exuberance. Journal of Brand Management, 18 , 97–104.

Barnett, M., & Salomon, R. (2006). Beyond dichotomy: The curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 27 , 1101–1122.

Barnett, W., Greve, H., & Park, D. (1994). An evolutionary model of organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal, 15 , 11–28.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17 , 99–120.

Barsade, S., Koput, K., & Staw, B. (1997). Escalation at the credit window: A longitudinal study of bank executives’ recognition and write-off of problem loans. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82 , 130–142.

Berle, A. (1932). For whom corporate managers are trustees: A note. Harvard Law Review, 45 , 1365–1372.

Bitektine, A. (2011). Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: The case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. Academy of Management Review, 53 , 151–178.

Bitektine, A., & Haack, P. (2015). The “macro” and the “micro” of legitimacy: Toward a multilevel theory of the legitimacy process. Academy of Management Review, 40 , 49–75.

Bonin, J., Hasan, I., & Wachtel, P. (2005). Bank performance, efficiency and ownership in transition countries. Journal of Banking and Finance, 29 , 31–53.

Bosse, D., Phillips, R., & Harrison, J. (2009). Stakeholders, reciprocity, and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 30 , 447–456.

Bradford, C. S. (2004). Does size matter? An economic analysis of small business exemptions from regulation . Nebraska:University of Nebraska, College of Law, Faculty Publications.

Google Scholar

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2008). Does it pay to be different? An analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 29 , 1325–1343.

Brammer, S., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Corporate reputation and social performance: The importance of fit. Journal of Management Studies, 43 , 435–455.

Campbell, J., Eden, L., & Miller, S. R. (2012). Multinationals and corporate social responsibility in host countries: Does distance matter? Journal of International Business Studies, 43 , 84–106.

Catino, M., & Patriotta, G. (2013). Learning from errors: Cognition, emotions and safety culture in the Italian Air Force. Organization Studies, 34 , 437–467.

Certo, S. T., & Semadeni, M. (2006). Strategy research and panel data: Evidence and implications. Journal of Management, 32 , 449–471.

Chen, Z., & Lurie, N. (2013). Temporal contiguity and negativity bias in the impact of online word of mouth. Journal of Marketing Research, 50 , 463–476.

Cohen, J. (1990). Things I have learned (so far). American Psychologist, 45 , 1304–1312.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112 , 155–159.

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences . Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ.

Day, D. (2001). Assessment of leadership outcomes. In S. Zaccaro & R. Klimoski (Eds.), The nature of organizational leadership (pp. 384–410). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Deephouse, D., Bundy, J., Tost, L. P., & Suchman, M. (2017). Organizational legitimacy: Six key questions. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. Lawrence & R. Meyer (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (2nd edn., pp. 27–54). Oxford: Sage.

Chapter Google Scholar

Deephouse, D., & Carter, S. (2005). An examination of differences between organizational legitimacy and organizational reputation. Journal of Management Studies, 42 , 329–360.

Dietz, J., Pugh, S., & Wiley, J. (2004). Service climate effects on customer attitudes: An examination of boundary conditions. Academy of Management Journal, 47 , 81–92.

Dodd, E. (1932). For whom corporate managers are trustees? Harvard Law Review, 45 , 1145–1163.

Doh, J., & Guay, T. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 43 , 47–73.

Doh, J., Howton, S., Howton, S., & Siegel, D. (2010). Does the market respond to an endorsement of social responsibility? The role of institutions, information and legitimacy. Journal of Management, 23 , 1461–1485.

Eden, L., & Miller, S. R. (2004). Distance Matters: Liability of foreignness, institutional distance and ownership strategy. In M. Hitt & J. Cheng (Eds.), The evolving theory of the multinational firm. Advances in International Management . Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Elayan, F., Li, H., Liu, Z., Meyer, T., & Felton, A. (2016). Changes in the covalence ethical code, financial performance and financial reporting quality. Journal of Business Ethics, 134 , 369–395.

Federal Reserve Board. (2008). Community reinvestment act. http://www.federalreserve.gov/dcca /cra/ .

Fombrun, C. (1996). Reputation: Realizing value from the corporate image . Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33 , 233–258.

Gates, C., & Villanueva, M. (2014). Community Reinvestment Act: Developing a strategy for success. Consumer Compliance Outlook, third quarter.

Goldman-Carter, J. (1992). Wetlands classification: A tool for protection or abandonment? Duke University Environmental Law & Policy Forum , 94–105.

Hambrick, D., & Mason, P. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9 , 193–206.

Hastie, R., & Dawes, R. (2001). Rational choice in an uncertain world: The psychology of judgment and decision making . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relationships . New York: Wiley.

Book Google Scholar

Hogarth, R., & Einhorn, H. (1992). Order effects in belief updating: The belief-adjustment model. Cognitive Psychology, 24 , 1–55.

Jeong, K.-H., Jeong, S.-W., Kee, W.-J., & Bae, S.-H. (2018). Permanency of CSR activities and firm value. Journal of Business Ethics, 152 , 207–223.

Jo, H., & Kim, Y. (2008). Ethics and disclosure: A study of the financial performance of firms in the seasoned equity offerings market. Journal of Business Ethics, 80 , 855–878.

Johnson, S., & Sarkar, S. (1996). The valuation effects of the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act and its enforcement. Journal of Banking & Finance, 20 , 783–803.

Kelley, H. (1973). The processes of causal attribution. American Psychologist, 28 , 107–128.

Kennedy, J. (1993). Debiasing audit judgment with accountability: A framework and experimental results. Journal of Accounting Research, 31 , 231–245.

Kim, J.-Y., & Miner, A. (2007). Vicarious learning from the failures and near-failures of others: Evidence from the U.S. commercial banking industry. Academy of Management Journal, 50 , 687–714.

King, B., & Whetten, D. (2008). Rethinking the relationship between reputation and legitimacy: A social actor conceptualization. Corporate Reputation Review, 11 , 192–207.

Lange, D., & Lee, P. (2011). Organizational reputation: A review. Journal of Management, 37 , 153–184.

Lee, D. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and management forecast accuracy. Journal of Business Ethics, 140 , 353–367.

Love, E., & Kraatz, M. (2009). Character, conformity, or the bottom line? How and why downsizing affected corporate reputation. Academy of Management Journal, 52 , 314–335.

Lupfer, M., Weeks, M., & Dupuis, S. (2000). How pervasive is the negativity bias in judgments based on character appraisal? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26 , 1353–1366.

Madsen, P., & Desai, V. (2010). Failing to learn? The effects of failure and success on organizational learning in the global orbital launch vehicle industry. Academy of Management Journal, 53 , 451–476.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2000). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strategic Management Journal, 21 , 603–609.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26 , 117–127.

McWilliams, A., Siegel, D., & Wright, P. (2006). Corporate social responsibility. Journal of Management Studies 43 , 1–18.

Mehra, A. (1996). Resource and market-based determinants of performance in the U.S. banking industry. Strategic Management Journal, 17 , 307–322.

Messier, W., & Tubbs, R. (1994). Recency effects in belief revision: The impact of audit experience and the review process. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 13 , 57–72.

Miller, S. R., & Eden, L. (2006). Local density and foreign subsidiary performance. Academy of Management Journal, 49 , 341–355.

Miller, S. R., & Parkhe, A. (2002). Is there a liability of foreignness in global banking? An empirical test of banks’ x-efficiency. Strategic Management Journal, 23 , 55–75.

Neter, J., Wasserman, W., & Kutner, M. (1990). Applied linear statistical models Chicago: Irwin.

Nofsinger, J., & Varma, A. (2013). Availability, recency, and sophistication in the repurchasing behavior of retail investors. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37 , 2572–2585.

O’Daniel, A. (2014). Bank of America hit with downgraded Community Reinvestment Act rating. Charlotte Business Journal , November 14.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F., & Rynes, S. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies, 24 , 403–441.

Pfarrer, M., Pollock, T., & Rindova, V. (2010). A tale of two assets: The effects of firm reputation and celebrity on earnings surprises and investors’ reaction. Academy of Management Journal, 53 , 1131–1152.

Rao, H. (1994). The social construction of reputation: Certification contests, legitimization and the survival of organizations in the American automobile industry. Strategic Management Journal, 15 , 29–44.

Reason, J. (1990). Human error . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rhee, M., & Haunschild, P. R. (2006). The liability of good reputation: A study of product recalls in the US automotive industry. Organization Science, 17.1 , 101–107.

Rhee, M., & Valdez, M. (2009). Contextual factors surrounding reputation damage with potential implications for reputation repair. Academy of Management Review, 34 , 146–168.

Rindova, V., Williamson, I., Petkova, A., & Sever, J. (2005). Being good or being known: An empirical examination of the dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of organizational reputation. Academy of Management Journal, 48 , 1033–1049.

Ritchie, T., Skowronski, J., Wood, S., Walker, W., Vogl, R., & Gibbons, J. (2006). Event self-importance, event rehearsal, and the fading effect bias in autobiographical memory. Self and Identity, 5 , 172–195.

Roberts, P., & Dowling, G. (2002). Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 23 , 1077–1093.

Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance and contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5 , 296–320.

Simpson, W. G., & Kohers, T. (2002). The link between corporate social and financial performance: Evidence from the banking industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 35 , 97–102.

Strategic implications. Journal of Management Studies , 43, 1–18.

Taylor, J., & Silver, J. (2009). The Community Reinvestment Act: 30 years of wealth building and what we must do to finish the job. In P. Chakrabarti, D. Erickson, R. Essene, I. Galloway & J. Olson (Eds.), Revisiting the CRA: Perspectives on the future of the Community Reinvestment Act . Boston: Federal Reserve Banks of Boston and San Francisco).

Terlaak, A. (2007). Order without law? The role of certified management standards in shaping socially desired firm behaviors. Academy of Management Review, 32 , 968–985.

Vitaliano, D., & Stella, G. (2006). The cost of corporate social responsibility: The case of the Community Reinvestment Act. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 26 , 235–244.

Wang, H., Choi, J., & Li, J. (2008). Too little or too much? Untangling the relationship between corporate philanthropy and firm financial performance. Organization Science, 19 , 143–159.

Wei, Z., Shen, H., Zhou, K., & Li, J. (2017). How does environmental corporate social responsibility matter in a dysfunctional institutional environment? Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 140 , 209–223.

Weigelt, K., & Camerer, C. (1988). Reputation and corporate strategy: A review of recent theory and applications. Strategic Management Journal, 9 , 443–454.

Wu, Z., & Salomon, R. (2016). Does imitation reduce the liability of foreignness? Linking distance, isomorphism, and performance.’. Strategic Management Journal, 37 , 2441–2462.

Zaheer, S. (1995). Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal, 38 , 341–363.

Zavyalova, A., Pfarrer, M., Reger, R., & Hubbard, T. (2016). Reputation as a benefit and a burden? How stakeholders’ organizational identification affects the role of reputation following a negative event. Academy of Management Journal, 59 , 253–276.

Download references

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meetings of the Academy of Management. We thank Joanna Tochman Campbell for her research assistance, and the editors and anonymous reviewers at the Journal of Business Ethics for their helpful comments, while retaining the responsibility for any errors or omissions.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Business, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, 78249, USA

Stewart R. Miller

Mays Business School, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, 77843-4221, USA

Lorraine Eden

Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, 47405, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lorraine Eden .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

Stewart R. Miller, Lorraine Edenand Dan Li declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (DOCX 13 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Miller, S.R., Eden, L. & Li, D. CSR Reputation and Firm Performance: A Dynamic Approach. J Bus Ethics 163 , 619–636 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4057-1

Download citation

Received : 03 March 2017

Accepted : 28 October 2018

Published : 08 November 2018

Issue Date : May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4057-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Corporate social responsibility

- Banking sector

- Firm performance

- Recency bias

- Negativity bias

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Corporate social responsibility and financial performance – the role of corporate reputation, advertising and competition

PSU Research Review

ISSN : 2399-1747

Article publication date: 26 April 2022

The research on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and firm performance (FP) has seen a surge over the years. However, the role of corporate reputation (CR), advertising strategy and market competition is still unclear. The purpose of this study is to consider this gap and test an integrative model of CSR-FP, in the context of India.

Design/methodology/approach

The data for CSR expenditure were collected from the annual reports of the selected companies. CR was captured using the ranks of Fortune India 500, Business Standard 1,000 and Economic Times 500. The financial data were collected from CMIE (Prowess) database.

Results of structural equation modeling (SEM) revealed a significant relationship between CSR expenditure of the firm and its reputation; but no relationship between CR and performance. When CR increases, the performance of a firm may not improve. Competitive intensity (CI) had no statistically significant role in the CR-FP relationship for performance. Results suggest that reputed firms perform well despite high competition within an industry. High reputation is effective in improving performance irrespective of competition. CI has a positive impact in the reputation–performance linkage. Advertising intensity (AI) played a significant moderating role in the CSR intensity and CR relationship.

Originality/value

This research represents an added value for the literature on CSR by highlighting the importance of CR, advertising strategy and market competition in the relationship between CSR and FP. The findings have several implications for theory and practice, which have been discussed in the study.

- Corporate social responsibility

- Corporate reputation

- Advertising

- Competition

- Financial performance

Bashir, M. (2022), "Corporate social responsibility and financial performance – the role of corporate reputation, advertising and competition", PSU Research Review , Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/PRR-10-2021-0059

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Makhmoor Bashir