Browser does not support script.

- Collaborations

Ambedkar Research Scholars

The sac encourages research scholars to engage with dr b r ambedkar's history, from his time at the lse and beyound..

Dr B R Ambedkar is one of the most important alumnus of LSE, from where he was awarded his MA and PhD. His doctoral thesis on ‘The Indian Rupee’, written in 1922-23, was later published as The Problem of the Rupee: Its Origin and Its Solution (London: P S King & Son, Ltd, 1923). Ambedkar was a Social Reformer, Economist, Parliamentarian, Jurist, and the Principal Architect of the Constitution of India.

A short biography can be found on the LSE History blog, along with a description of his time at the LSE.

2015 Scholars Visits

As part of the 125th Birth Anniversary Celebrations of Dr B R Ambedkar, the SAC hosted two delegations of research scholars and government officials for week-long visits on 24-31 October 2015 and 21-28 November 2015, in collaboration with the High Commission of India in London and the Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Government of India.

With two tours of 25 students & three officers each, the objectives of these trips were i) to show how HE institutions function in the UK, ii) the academic and educational facilities available that are relevant to theirresearch interests at LSE, iii) the rare archival collections relevant to India in museums and collections in London, iv) the multiculturallie in London and v) to introduce students to issues of social inequality, injustice and empowerment affecting contemporary Britain.

Whilst here, two students were interviewed by Rozelle Laha from the Hindustan Times , culminating in an article published in the Delhi edition (in page 19) on Wednesday, 2 December 2015.

Columbia University Libraries

Dr. ambedkar and columbia university: a legacy to celebrate.

For those of you who may not know, Dr. Ambedkar is a Dalit, an Indian jurist, economist, politician, activist and social reformer, who systematically campaigned against social discrimination towards women, workers, but most notably, towards the Dalits, and forcefully argued against the caste system in Hindu society. Dr. Ambedkar was the main architect of the Constitution of India, and served as the first law and justice minister of the Republic of India, and is considered by many one of the foremost global critical thinkers of the 20 th c., and a founder of the Dalit Buddhist movement. Ambedkar’s fight for social justice for Dalits, as well as women, and workers consumed his life’s activities: in 1950 he resigned from his position as the country’s first minister of law when Nehru’s cabinet refused to pass the Women’s Rights Bill. His feud with Mahatma Gandhi over Dalit political representation and suffrage in the newly independent State of India is by now famous, or I should say notorious, and it is Dr. Ambedkar who comes out on the right side of history.

The bronze bust, sculpted by Vinay Brahmesh Wagh of Bombay, was presented by the Federation of Ambedkarite and Buddhist Organizations, UK to the Southern Asian Institute of Columbia University on October 24, 1991, and then the wooden pedestal on which the statue now rests was donated by the Society of the Ambedkarites of New York and New Jersey, and placed in Lehman Library in 1995. The bust is the only site in the city where Dr. Ambedkar is honored, and is one of the most popular sites in enclosed spaces on campus that I have seen (you have to walk past the library entrance to get to it).

Every year, on April 14 th, Ambedkar’s birthday, Ambedkar Jayanti or Bhim Jayanti, is celebrated in India (as an official holiday since 2015), at the UN (since 2016), and around the world. On this day, many visitors flock to Lehman Library, to pay tribute to Baba Saheb and place garlands on the bust. The sight of the visitors– many of whom come to Columbia just to see the bust and pay homage to the man who changed Indian society, brings home the significance of recognizing our critical thinkers, across cultures, eras, languages, divisions and types of social injustice, in the public fora of libraries. It is a powerful reminder that it is through scholarship and indeed through libraries and learning that human differences and injustices can be better understood, addressed and perhaps overcome.

Years later, Dr. Ambedkar writes: ‘The best friends I have had in life were some of my classmates at Columbia and my great professors, John Dewey , James Shotwell, Edwin Seligman , and James Harvey Robinson.'” (Source: “‘Untouchables’ Represented by Ambedkar, ’15AM, ’28PhD,” Columbia Alumni News, Dec. 19, 1930, page 12.)

Ambedkar majored in Economics, and took many courses in sociology, history, philosophy, as well as anthropology.

In 1915, he submitted an M. A. thesis entitled: The Administration and Finance of the East India Company . (He is believed to have begun an M. A. thesis entitled Ancient Indian Commerce earlier. That thesis is unavailable at the RBML but it is reprinted in volume 12 of Ambedkar’s collected writings). By the time he left Columbia in 1916 Ambedkar had begun research for his doctoral thesis entitled: “National Dividend of India–A Historic and Analytical Study. About this thesis, Ambedkar writes to his mentor Prof. Seligman, with whom he forged a long and friendly correspondence, even after he left Columbia: “My dear Prof. Seligman, Having lost my manuscript of the original thesis when the steamer was torpedoed on my way back to India in 1917 I have written out a new thesis… [ …from the letter of Feb. 16, 1922, Seligman papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University ” cited in Dr. Frances Pritchard’s excellent online website about Ambedkar ]. In 1920, Ambedkar writes: “My dear Prof. Seligman, You will probably be surprised to see me back in London. I am on my way to New York but I am halting in London for about two years to finish a piece or two of research work which I have undertaken. Of course I long to be with you again for it was when I was thrown into academic life by reason of my being a professor at the Sydenham College of Commerce & Economics in Bombay, that I realized the huge debt of gratitude I owe to the Political Science Faculty of the Columbia University in general and to you in particular.” B. R. Ambedkar, London, 3/8/20” , (Source: letter of August 3, 1920, Seligman papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, cited in Pritchard’s website ). Ambedkar would join the London School of Economics for a few years and submit a thesis there, but then, he would eventually come back to Columbia, to submit a Ph.D. thesis in Economics , in 1925 under the mentorship of his dear friend Prof. Seligman, entitled: The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India: A Study in the Provincial Decentralization of Imperial Finance . (It should be noted here that the thesis was first published in 1923 and again in 1925, this time with a Foreword by Edwin Seligman, by the publishers P. S. King and Son).

If it is Seligman he stayed in touch with and corresponded throughout, the person who most influenced his thought and shaped his political, philosophical and ethical outlook, was Dewey. For many thinkers, the links between Dewey and Ambedkar’s ethical and philosophical thinking are obvious. Ambedkar deeply admired Dewey and repeatedly acknowledged his debt to Dewey, calling him “his teacher”. Ambedkar’s thought was deeply etched by John Dewey’s ideas of education as linked to experience, as practical and contextual, and the ideas of freedom and equality as essentially tied with the ideals of justice and of fraternity, a concept he would go on to apply to the Indian context, and to his pointed criticism of the caste system. Echoing many ideas propagated by Dewey, Ambedkar writes in the Annhilation of Caste : “Reason and morality are the two most powerful weapons in the armoury of a reformer. To deprive him of the use of these weapons is to disable him for action. How are you going to break up Caste, if people are not free to consider whether it accords with reason? How are you going to break up Caste, if people are not free to consider whether it accords with morality?”

Having sat in several classes given by Dewey, and as early as 1916, Ambedkar would go on to address, at a Columbia University Seminar taught by the anthropologist Prof. Alexander Goldenweiser (1880-1940), his colleagues and friends with many of the ideas he later developed in his famous book: the Annihilation of Caste. The paper “ Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis, and Development ” contains many similarities to the Annihilation of Caste, and some of the books’ essential tenets., as acknowledged by Ambedkar himself ( Preface to the 3rd edition, Annihilation of Caste ).

The Columbia University Archives and the Columbia University Libraries hold many resources related to Dr. Ambedkar and to the Dalit movement and Dalit literature. For any inquiries regarding relevant resources, please do not hesitate to contact us: Gary Hausman : South and Southeast Asian Librarian , Global Studies; Rare Book and Manuscript Library: RBML Archivists

Happy Baba Saheb Ambedkar Juyanti!

Kaoukab Chebaro , Global Studies, Head

Today, for the first time studying for Civil Services I got to know about this great man. I think that in the galaxy of freedom fighters which India have produced he was the one we can truly say as the ‘Pole Star’. A true leader who walked the talk, he fought not only for country but also for the rights of the minority who were being annihilated for centuries. We should take cue from this man and try to go for equality, and that equality should be of thoughts, feelings and desires. It’s not at all wrong to aspire for greatness in life but to stifle a man’s path with the chains of societal norms is a sin in my sense. I hope to imbibe some of his qualities in my life. Let long live his legacy.

Thus my goodDr.BR. Ambedkar

Indeed Great emancipator of millions marginalised people, architect of Indian constitution, philosopher, economist, social reformer, jurist, astute politician no lastly father of modern India !! Jaibhim !!

What a great man. Wonderful article.

If it wasn’t for Dr.Ambedkar I wouldn’t be here in this country and have a life that I do now. I will forever be indebted to this Great Man’s courage in the face of adversity. Words cannot describe the gratitude I have for this man Thank you

Excellent effort to make this blog more wonderful and attractive.

Dr. Ambedkar was a great man.

Wonderful Article and an excellent blog. Greetings. Llorenç

Baba Saheb Dr. B R Ambedkar is alive in his works for humanity. Study Social Science or Law, or Education, or about farmers, or Dams and irrigation, or planning commission and budget or journalism, or human rights ……. on most of the subjects and disciplines, his live seen in his works and writtings. By reading him; his life, and his works, he inspires others by his works for the betterment of the society and a world, as a whole.

- Pingback: Ambedkar and the Study of Religion at Columbia University

Every breathe I take today is because of your struggle to give us an equal and fair society. It could not be possible to imagine even a single day without understanding your life and struggles. Each and every aspect of my existence is because of you Babasaheb. However, the current state of Dalit society pains me.

Such a great personality, tried hard to improvise the system in the country but had to face too much opposition and hatred. Salute to his strength and beliefs that he continued his fight for social justice despite such circumstances.

He was a great man, I considered India’s progress because of his work for the emancipation of millions of marginalized people in India

Is Columbia University conducting a Post Graduate course or PHD on Dr. Ambedkar thought?

Baba sahab Was great human Baba sahab is great human Baba sahab will great human .

Baba sahab god gifted and human for students, politicians, poor humans and all leaders ❤❤

I am thankful to Babasaheb Ambedkar for the beautiful living given to me by his at most efforts to eradicate the caste system through out India and to uplift the standard of living of the downtrodden of this country. He was a great man who fought for the rights and upliftment of the downtrodden and the dignity of women of this nation. A true Indian and a great patriot of the nation. I salute him for his work and knowledge.

A Bengali Chandal, who, according to Manu Code, later redesignated as Namasudra, I am grateful, over head and ears, to the teachings and thoughts of Dr. Babasaheb B. R. Ambedkar who inspired with dreams and shaped my life and achievement. Lost my parents by two and half years, I was brought up by my two elder elder brothers, both illiterate under care of my father’s childless sister, who took full charge of me. A family of poor agriculturist, my eldest brother was just literate but the second elder brother was totally illiterate. They were, nonetheless, all supportive of my education. Not only my family was illiterate but the whole village as well as the locality comprising hundreds and thousands of people, men and women, were illiterate. I had none to help me in my village for studies. My village boasted of a primary school, established 10 years before my joining the same . ****The village school was upgraded class by class till 10th standard by 1962. But before that I had to migrate elsewhere for Matriculation Examinations which I cleared with FIRST DIVISION—none did this before me around. I went for studies up to B. A. (Hons. in Economics). Then I sat for IAS Exams and was declared I qualified against a reserved candidate by the UPSC. One of my assignments IN 33 YEARS career was as Vice-Chancellor, Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar Bihar University, Muzaffarpur, Bihar. The original name of the University was Bihar University, which, as a homage to the great son in the year of his centenary was rechristened as Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar Bihar University. It was my pleasant duty to change the name of the university in accordance with the mandate of the law as passed by Bihar State Legislature. Maharashtra fought for 20 years to implement the legislative mandate. There was widespread violence and mayhem in Marathwada over the change of name of Marathwada University. I changed the name the day I joined the university as Vice-Chancellor without anybody even knowing how did I do it. No force was used or no violence occurred. This is my most adorable, nay proud, moment in my career. **** I am an author and have published innumerable articles carried by many leading English journals and dailies over last three decades. ****I prosecuted studies as a private candidate and passed MA. I also did my dissertation for Ph. D. All these I did when government assigned light duty to me. ****In three decades, one highly reputed Delhi English Weekly alone carried about four hundred thousand (400,000) words having great bearing social significance. I am a researcher. Babasaheb is my ideal and my beacon light. I am grateful to him.**** I prosecuted my studies with Welfare Scholarships of Government of India without which I could not have done what I have did. *****I have suffered hatred, discrimination, bias and injustice in various spheres. By the way, I have also been topper in my class irrespective of students belonging to different castes. English is my forte. I write in Bengali too.

Because of Dr. BR Ambedkar i am alive today, he is my past, present and my future, my heart, my soul. Thank you for saving my life and many generations.

Amazing Article. No words to explain how I felt touched being a follower of Dr. Ambedkar

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

CUL Blogs Home CUL Blogs Dashboard

- India Today

- Business Today

- Reader’s Digest

- Harper's Bazaar

- Brides Today

- Cosmopolitan

- Aaj Tak Campus

- India Today Hindi

Get 72% off on an annual Print +Digital subscription of India Today Magazine

Why publication of b.r. ambedkar’s thesis a century later will be significant, a contemporary relevance of the thesis, written as part of ambedkar’s msc degree at the london school of economics, is that it argues for massive expenditure on heads like defence to be diverted to the social sector.

Listen to Story

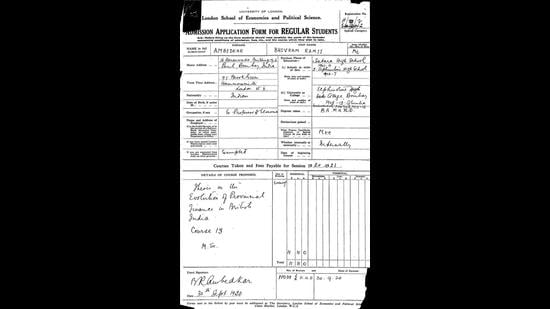

Now, over a century after it was written, Ambedkar’s hitherto unpublished thesis on the provincial decentralisation of imperial finance in colonial times will finally see the light of the day. The Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee of the Maharashtra government plans to publish the thesis that was written by Ambedkar as part of his MSc degree from the London School of Economics (LSE). The thesis, ‘Provincial Decentralisation of Imperial Finance in British India’, will be part of the 23rd volume of Ambedkar’s works to be published by the committee and will give a glimpse into the works of Ambedkar, the economist. Notably, the dissertation argues for expenditure on heads like defence to be diverted for social goods like education and public health.

The source material committee, which was set up in 1978, has published 22 volumes on Ambedkar’s writings since April 1979. “This volume will have two parts. One will contain the MSc thesis and the other will have communication and documents related to his MA, MSc, PhD and bar-at-law degrees,” confirmed Pradeep Aglave, member secretary of the committee. He added that the MSc thesis had been submitted to the LSE in 1921. Veteran Ambedkarite and founder of the Dalit Panthers, J.V. Pawar, who is a member of the committee, said it was significant that the thesis was being published over a century after it was written. Pawar played a pivotal role in ensuring that the committee was set up.

“This work deals with taxation and expenditure. The contemporary relevance of this thesis is that it seeks a progressive taxation based on income levels. Ambedkar argued that expenditure on heads like defence was huge and this needed to be diverted to social needs like education, public health, and water supply,” said Sukhadeo Thorat, economist and former chairman of the University Grants Commission (UGC). Thorat was among those instrumental in the source material committee getting a copy of the thesis from London.

“The sixth volume (1989), published by the source material committee, contains Ambedkar’s writings on economics. This includes his works like ‘Administration and Finance of the East India Company’ (1915) and the ‘Problem of the Rupee: Its Origin and Its Solution’ (1923). However, this MSc thesis on provincial finance could not be included in it because it was not available then,” said Thorat.

J. Krishnamurty, a Geneva-based labour economist located the MSc thesis in the Senate House Library in London and approached Thorat who, in turn, communicated with Gautam Chakravarti of the Ambedkar International Mission in London. Santosh Das, another Ambedkarite from London, paid the fees for permission to reproduce the work in copyright. The soft copy of the thesis was sent to the source material committee on November 18, 2021.

In addition to the MSc thesis, the communication and letters related to his academics, such as the MA, PhD, MSc and DSc and bar-at-law including LLD (an honorary degree that was awarded to Ambedkar by the Columbia University in 1952after he finished drafting the Constitution of India, which remains one of his most significant contributions to modern India), were also arranged and compiled by Krishnamurty, Thorat and Aglave. This also includes the courses done by Ambedkar for his MA and pre-PHD at the Columbia University. These details are being published for the first time.

Ambedkar’s biographer Changdev Bhavanrao Khairmode, writes how Ambedkar worked untiringly in London for his MSc. Ambedkar secured admission for his MSc in the LSE on September 30, 1920 by paying a fee of 11 pounds and 11 shillings. He was given a student pass with the number 11038.

Ambedkar had prepared for his MSc in Mumbai, yet he began studying books and reports from four libraries in London, namely the London University’s general library, Goldsmiths' Library of Economic Literature and the libraries in the British Museum and India Office. In London, Ambedkar would wake up at 6 am, have the breakfast served by his landlady and rush to the library for his studies. Around 1 pm, he would take a short break for a meagre lunch or have just a cup of tea and then return to the library to study till it closed for the day.

“He would sleep for a few hours. He would stand at the doors of the library before it opened and before others came there,” says Khairmode in the first volume of his magisterial work on Ambedkar (Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, Volume I) that was first published in 1952. The library staff in the British Museum would tell Ambedkar that they had not seen a student like him who was immersed in his books and they also doubted if they would get to see one like him in the future!

The volume also contains a letter written by Ambedkar in German on February 25, 1921 to the University of Bonn seeking admission. Ambedkar wanted to study Sanskrit language and German philosophy in the varsity’s department of Indology. In school, Ambedkar was discriminated against on grounds of caste and not allowed to learn Sanskrit. He had to learn Persian instead. Ambedkar secured admission to Bonn University but had to return to London three months later to revise and complete his DSc thesis.

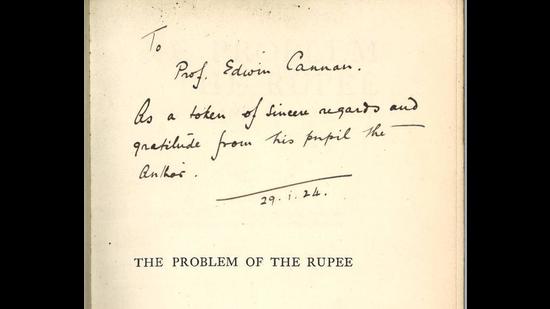

Ambedkar completed his DSc in 1923 under the guidance of Professor Edwin Cannan of the LSE on the problem of the rupee, which is described as a “remarkable piece of research on Indian currency, and probably the first detailed empirical account of the currency and monetary policy during the period”.

Ambedkar was among the first from India to pursue doctoral studies in economics abroad. He specialised in finance and currency. His ‘The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India: A Study in the Provincial Decentralisation of Imperial Finance (1925)’, carried a foreword by Edwin R.A. Seligman, Professor of Economics, Columbia University, New York. Ambedkar also played a pivotal role in the conceptualisation and establishment of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in 1935.

Subscribe to India Today Magazine

India Votes 2024

Bow and arrow or torch? In Maharashtra, confusion over new election symbols may help BJP, allies

BJP worker’s son claims in video he cast eight votes in Uttar Pradesh’s Farrukhabad

International Booker Prize 2024: Quick reviews of the six shortlisted novels

Why a health crisis is brewing among the labourers of Assam’s tea gardens

Listening to 41 Modi interviews: Few tough questions, no rebuttals, no fact checks

BJP worker’s son arrested after video shows him casting eight votes in Uttar Pradesh’s Farrukhabad

Varanasi poll: As 33 nominations are rejected, eight applicants allege that the process was rigged

First person: Why I came home from the UK to vote this year

What a regal South Indian ornament in a famous Rossetti painting tells us about the British Raj

Is Anirban Bhattacharya Bengali cinema’s white knight?

BR Ambedkar in London: A thesis completed, a treaty concluded, a ‘bible’ of India promised

An excerpt from ‘indians in london: from the birth of the east indian company to independent india’, by arup k chatterjee..

About two decades ago, when [Subhash Chandra] Bose was still at Cambridge, a letter dated September 23, 1920 arrived at Professor Herbert Foxwell’s office at the London School of Economics. It was written by Edwin R Seligman, an economist from Columbia University, introducing an exceedingly talented scholar – Mr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar. Two months later, Foxwell wrote to the secretary of the School that there was no more intellect that the Columbia graduate could conquer in London.

The first Dalit to study at Bombay’s Elphinstone College, Ambedkar, was awarded a Baroda State Scholarship that took him to Columbia University in 1913. Three years later, he found his way to London, desirous of becoming a barrister as well as finishing a doctoral dissertation on the history of the rupee. Ambedkar enrolled at Gray’s Inn, and attended courses on geography, political ideas, social evolution and social theory at London School of Economics, at a course fee of £10.10s.

In 1917, Ambedkar was invited to join as Military Secretary in Baroda, earning at the same time a leave of absence of up to four years from the London School of Economics. Back in India, he taught for a while as a professor in Sydenham College in Bombay, while also being one of the key intelligencers on the condition of “untouchables” in India for the government, during the drafting of the Government of India Act of 1919.

In late 1920, Ambedkar was to return to London, determined more than ever before, not to spare a farthing beyond his breathing means on the city’s allurements. Each day, the aspiring barrister woke up at the stroke of six. After a morning’s morsel, he moseyed into the crowd of London to find his way into the British Museum.

At dusk, he would leave his seat reluctantly – after being made to scurry out by the librarian and the guards – his pockets sagging under the notes that would finally become his thesis, The Problem of the Rupee , some of whose guineas would eventually find their home in the Constitution of India that he was going to author about three decades later. Back at his lodging at King Henry’s Road in Primrose Hill, mostly on foot, Ambedkar would live on sparsely whitened tea and poppadum late into the night.

It was here that the daughter of Ambedkar’s landlady, Fanny Fitzgerald, a war widow, found her affections strangely swayed by the Indian scholar. Fitzgerald was a typist at the House of Commons. She lent him money in difficult circumstances and volunteered to introduce him to people in governance, with whom he could discuss the Dalit question that was raging in India.

An apocryphal story goes that Miss Fitzgerald once gave Ambedkar a copy of the Bible. On receiving it, the future Father of the Indian Constitution promised to dedicate a bible to her of his own authoring. True to his commitment, he would fondly dedicate his book What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables (1945) to “F”. The incident, when that promise was exchanged, occurred after Ambedkar was called to the Bar in 1923.

In March that year, his doctoral thesis ran into trouble possibly because of its radical approach to the history of Indian economy under the British administration. He might have taken the subtle hint that passages in his work needed tempering – a notion that a man of his vision was likely to have quietly pocketed more as a compliment than an insult.

Ambedkar would have been happy to chisel the nose from his David for the show, like Michelangelo had four centuries ago in order to appease the connoisseur-like pretense of Piero Soderini, who had quipped, “Isn’t the nose a little too thick?” That done, Ambedkar resubmitted his thesis in August. It was approved two months later and published almost immediately thereafter. He expressed gratitude to his professor, Edwin Cannan, who, in turn, wrote the preface to his thesis, before Ambedkar travelled to Bonn for further studies.

Babasaheb, as he was now beginning to be called, was to return to London for each of the three Round Table Conferences held between 1930 and 1932. Two months before the Third Round Table Conference – in which both Labour and the Congress were absentees – Ambedkar and Gandhi reached a historic settlement in the Poona Pact. In September 1932, from the Yerwada prison near Bombay, Gandhi began a fast unto death protesting against the Ramsay MacDonald administration that was determined to divide India into provincial electorates on the basis of caste and social stratification.

In the pact signed with Madan Mohan Malviya, Ambedkar settled for 147 seats for the depressed classes. But the pact to which he was forsworn – tacitly made in London with Fanny Fitzgerald – that of writing the bible of modern India, was brewing like a storm that would take the form of an open battle between him and Gandhi, in the years of the Second World War.

Despite the strong network of Indians at the London School of Economics, Ambedkar chose not to hobnob with India League members. What might have been a sort of marriage-made-in-heaven between him and [VK Krishna] Menon was forestalled. If Menon was Nehru’s alter ego, he would also be instrumental in shaping the early career of the man to become an alter ego – principal secretary –to Indira Gandhi.

In the winter of 1935, a twenty-something Parmeshwar Narain Haksar arrived in London, enrolled as a student at the University College. The following year, he made an unsuccessful attempt for the civil services. In 1937, Haksar became a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute, a distinction conferred on him with support from noted anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski.

Although Haksar also studied at the London School of Economics, it probably never became public knowledge if he had acquired formal degrees from either university. Whether or not he did, as a scholar he commanded great attention from British intellectuals, especially in his arguments on the crisis of education in India, which he reckoned had been tailored to perpetuate British imperial interests and low levels of literacy in the colony.

Haksar was to be called to Bar at the Lincoln’s Inn, but, at the beckoning of Nehru, he would join the Indian Foreign Service in 1948. His red days in London were to yield him lifelong companions. In the 1930s, the Comintern came up with the policy of hatching popular fronts all across Europe with which to counter the growing threat of Nazism and Fascism. It was a phase in European ideologies that strongly affected British politics, and popular movements led by Labour leaders and student communists in London – a cosmopolitan and unswervingly left-leaning outlook that shaped much of the administration and policies of independent India until the years of the Emergency.

A socialist himself, Haksar held an influential position in the Federation of Indian Societies in UK and Ireland besides becoming the editor of its magazine, The Indian Student . His links with the Communist Party of Great Britain, Rajani Palme Dutt and the Soviet undercover agent at Cambridge, James Klugman – indeed with almost anyone of some consequence who supported the cause of Indian liberation – was more than enough for Scotland Yard to keep him closely watched in London.

In September 1941, when the India League organised a commemoration at the Conway Hall in Red Lion Square for the late Rabindranath Tagore a few months after his demise, Scotland Yard obliged by adding a leaf to their surveillance files. Inaugurated by M Maisky, a Russian ambassador, it was just one in a sea of events concerning India that the Yard and other intelligencers of His Majesty’s Government would tolerate during the interwar years. Almost all such gatherings featured subversive pamphlets and books published by the League and similar organisations that were openly lauded by Soviets and Soviet sympathisers.

It was just as well that Nehru also had to tolerate that under the shield of Haksar’s own watch a new romantic plot thickened around Primrose Hill, that of his daughter Indira and future son-in-law, Feroze. Feroze had his flat at Abbey Road and Haksar lived half a mile away, at Abercorn Place. Haksar was befriended by the Gandhis – Indira and Feroze – who introduced him to Sasadhar Sinha of the Bibliophile Bookshop. That, besides the India League and Allahabad connection, not to mention Haksar’s enviable culinary skills, ensured that he was soldered to the future of the Gandhis.

The future of the man who had leant the family his coveted surname would also take a blow on the burning issue of caste. Gandhi was not to be remembered as the sole nemesis of the British Empire. In an interview given to the BBC in 1955, Babasaheb indicated that one of the biggest reasons behind Clement Attlee handing over the reins of the Indian administration so suddenly was the persistent fear of a massive armed uprising in the colony.

He implied that the road to independence had already been paved by the Azad Hind Fauj brigadiered by Netaji. Bose had departed from London during Ambedkar’s days in the London School of Economics. But, he would return in Haksar’s time.

- Swapan Kumar Bhattacharyya 3

46 Accesses

B. R. Ambedkar, a polymath and an untiring social activist, had several important ideas about the Indian socio-cultural reality. But he has so far been denied a rightful place in the annals of development of Indian sociology. Perusal of Ambedkar’s ideas and course of action to realize them immediately unravel the problems of: (a) analysing the nature of interface of tradition and modernity in India, a country endowed or burdened with a millennia-old tradition and challenged by modernity; (b) assessing the nature of ‘social exclusion’ (a concept innovated by Ambedkar before anybody else in India or abroad) practised by the savarna , following Brahminical injunctions, against the numerous (ex-)untouchables of India; (c) adequately realizing the nature of ‘lived experience’ of the socially ostracized by those who lack in the taste of the lived experience. Associated with it is the problem besetting attempts at theorization of ‘distinctive’ predicament of the dalits. The dilemma, hitherto neglected by scholars, confronting Ambedkar and other dalits in facing the ‘two leeches’ then tormenting the Indian/Hindu society, viz., the British and the Brahminical rule, merits attention. The paper seeks to also explain the apparent contradiction between Ambedkar’s sharing of Ranade’s grief over the defeat of the Marathas by the British at the Battle of Khadki (Kirkee) and his celebration of the event at Bheema Koregaon.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Ambedkar, B. R. (1941). Thoughts on Pakistan . Thacker & Co., Ltd.

Google Scholar

Ambedkar, B. R. (1946). Pakistan or the partition of India . Thacker & Co., Ltd.

Ambedkar, B. R. (n.d.) [1916]. Castes in India: Their mechanism, genesis and development. In BAWS (Vol. 1). Bheem Patrika Publications.

Ambedkar, B. R. (1919). Evidence before the Southborough committee on franchise. In BAWS (Vol. 1, No. 4). Dr. Ambedkar Foundation.

Ambedkar, B. R. (1943). Ranade, Gandhi and Jinnah. In BAWS (Vol. 1, No. 4). Dr. Ambedkar Foundation.

Ambedkar, B. R. (1945). What congress and Gandhi have done to the untouchable. In BAWS (Vol. 9). Dr. Ambedkar Foundation.

Ambedkar, B. R. (1990a) [1948]. The untouchables: Who were they? and why they became untouchables. In BAWS (Vol. 7, No. 2). Maharashtra Government, Education Department.

Ambedkar, B. R. (1990b). Waiting for a visa. In BAWS (Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 661–669). People’s Education Society.

Ambedkar, B. R. (2004). Conversion as emancipation. In BAWS (Vol. 17, No. 7). Critical Quest.

Ambedkar, B. R. (2006) [1943]. Mr. Gandhi and the emancipation of the untouchables . Critical Quest.

Ambedkar, B. R. (2007a). Buddha or Karl Marx . Critical Quest.

Ambedkar, B. R. (2007b) [1936]. Annihilation of caste . Appendix I ‘Gandhi’s response to Annihilation of caste . Dr. Ambedkar’s indictment. Critical Quest.

Ambedkar, B. R. (2014). Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and speeches . In BAWS (Vol. 1). Dr. Ambedkar Foundation, Government of India. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment.

Ambedkar, B. R. (2019a). Mooknayaki , (Sheoraj Singh Bechain, Comp. and Trans. from Marathi into Hindi). Gautam Book Centre.

Ambedkar, B. R. (2019b). Mooknayak (Vinoy Kumar Vasnik, Trans.). Samyak Prakashan.

Bahadur, R. (2017). A glance at Dr. Ambedkar writings . Forward Press, 10 February 2017.

Bandyopadhay, S. (2004). Caste, culture and hegemony . Oxford University Press.

Bandyopadhay, S. (2011). Caste, protest and identity in colonial India: The Namasudras of Bengal 1872–1947 . Oxford University Press.

Béteille, A. (Ed.). (1984). Social inequality . Penguin Books Ltd.

Béteille, A. (1991). Society and politics in India: Essays in a comparative perspective . The Athlone Press.

Bhattacharyya, S. K. (1990). Indian sociology: The role of Benoy Kumar Sarkar . The University of Burdwan.

Bose, N. K. (1976). The structure of Hindu society. (Andre Beteille’s English translation of Hindu Samajer Gadan [1949]). Sangam Books.

Bose, P. K. (2018). Conceptualising man and society: Perspectives in early Indian sociology . Orient Blackswan.

Bottomore, T. B. (2012/1975). Sociology as social criticism . Routledge.

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology . University of Chicago Press.

Chandramohan, P. (1987). Popular culture and socio-economic reform: Narayana Guru and the Ezhavas of Travancore. Studies in History , 3 (1), 57–74.

Article Google Scholar

Chaudhury, K. (2019). Jater Vinash: Ambedkar O Tnar Agrajader Abadan (Annihilation of caste: Contribution of Ambedkar and his predecessors). Bhabna and Dafodwam.

Dangle, A. (Ed.) (1992). Poisoned bread: Translations from modern Marathi Dalit literature . Orient Longmans.

Dewey, J. (2004) [1915]. Democracy and education . Aakar Books.

Gajbhiye, P. (trans.) (2017). Bahishkrit Bharat mein prakashit Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar ke sampadakiya (Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s editorials in Bahishkrit Bharat–Hindi translation of pieces in Marathi). Samyak Prakashan. Eng. Trans. Amrish Herdenia for Forward Press.

Ghurye, G. S. (1933). Untouchable classes and their assimilation in Hindu society . Included in Ghurye, 1973a, 316–323. [Though Ambedkar is not named,it seems a nice paraphrase of Ambedkar’s views].

Ghurye, G. S. (1969). Caste and race in India . Popular Prakashan.

Ghurye, G. S. (1973). I and other explorations . Popular Pakashan.

Giddens, A. (1991). Identity, self and society in the late modern age . Polity Press.

Gore, M. S. (1993). The social context of ideology: Ambedkar’s political and social thought . Sage Publications.

Gouldner, A. (1970). The coming crisis of western sociology . Basic Books.

Grusky, D. B., & Szélenyi, S. (Eds.). (2012). [Indian Reprint]. The inequality reader: Contemporary and foundational readings in race, class and gender . Rawat Publications.

Grusky, D. B. (2012). The stories about inequality that we love to tell. In Grusky & Szélenyi (Eds.), The inequality reader (pp. 2–14). Routledge.

Guha, R. (Ed. & intr.). (2010). Makers of modern India . Viking–Penguin Random House India.

Guru, G. (2015). Experience and ethics of theory. In G. Guru & S. Sarukkai (Eds.), The cracked mirror: An Indian debate on experience and theory (pp. 107–127). Oxford University Press.

Guru, G., & Sarukkai, S. (Eds.). (2015). The cracked mirror: An Indian debate on experience and theory . Oxford University Press.

Guru, G. (2017). Ethics in Ambedkar’s critique of Gandhi. Economic and Political Weekly , 52 (15), 95–101.

Jaffrelot, C. (2015). Dr. Ambedkar and untouchability: Analysing and fighting caste . Permanent Black.

Kumar, A. (2020). Reading Ambedkar in the time of Covid-19. Economic and Political Weekly , 55 (16), 34–37.

Kumbhojkar, S. (2012). Contesting power, contesting memories. Economic and Political Weekly , 47 (42), 103–107.

Lenoir, R. (1989). Les exclus: Un Français sur dix . Editions du Seuil.

Mauthner, N. S., & Doucet, A. (2003). Reflexive accounts and accounts of reflexivity in qualitative data analysis. Sociology , 37 (3), 413–431.

Mills, C. W. (1959). The sociological imagination . Oxford University Press.

Moon, V. (2018). Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar . National Book Trust.

Mukherjee, R. (1979). Sociology of Indian sociology . Allied Publishers.

Nagla, B. K. (2008). Indian sociological thought . Rawat Publications.

O’ Hanlon, R. (Ed. & tr.). (1994). A comparison between women and men: Tarabai Shinde and the critique of gender relations in colonial India . Oxford University Press.

Omvedt, G. (2005). Dr. Ambedkar prabuddha Bharat ki aur . Penguin Books.

Omvedt, G. (2007). Jotirao Phule and the Ideology of Social Revolution in India . Critical Quest.

Oommen, T. K., & Mukherjee, P. N. (Eds.) (1986). Indian sociology: Reflections and interpretations . Popular Prakashan.

Parkin, F. (2007). Max Weber . Routledge.

Patel, S. (Ed.). (2011). Doing sociology in India . Oxford University Press.

Ramanujam, S. (2020). Dalitness and the idea of Brahmin. Economic and Political Weekly , 55 (2), 12–15.

Rattu, N. C. (1995). Reminiscences and remembrances of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar . Falcon Books.

Sarkar, B. K. (1937). Creative India: From Mohenjo Daro to the age of Ramakrishna-Vivekananda . Motilal Banarsi Dass.

Sarkar, B. K. (1940a). Digvijayer Dharma O Samaj [The Religion and Social Order Propelling the Conquest of Quarters]. In Sarkar (Ed.), pp. 105–137.

Sarkar, B. K. (Ed.). (1940b). Samaj–Vignan . Chakravartty, Chatterjee and Company Ltd.

Sarukkai, S. (2015). Experience and theory: From Habermas to Gopal Guru. In G. Guru & S. Sarukkai (Eds.), The cracked mirror: An Indian debate on experience and theory (pp. 29–45). Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (2007). Social exclusion: Concept, application and scrutiny . Critical Quest.

Sharma, S. (1985). Sociology in India: A perspective from sociology of knowledge . Rawat Publications.

Siddharath (2020). Bahiskrit Bharat: Brahmanbad–Manubad ko Ambedkar ki nirnayak chunauti . Forward Press (January 30, 2020).

Singh, Y. (1986). Indian sociology: Social conditioning and emerging concerns . Vistaar Publications.

Uberoi, P., Sundar, N., & Deshpande, S. (intr. & Eds.) (2007). Anthropology in the East: Founders of Indian sociology and anthropology . Permanent Black.

Wakefield, D. (2000). Introduction. In C. Wright Mills (Eds.), Letters and autobiographical writings (pp. 1–18). University of California Press.

Yengde, S. (2019, digital update). Caste matters . Viking-Penguin Random House India.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Calcutta, Kolkata, India

Swapan Kumar Bhattacharyya

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Swapan Kumar Bhattacharyya .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Formerly Department of Sociology, M. D. University, Rohtak, India

B. K. Nagla

Formerly Department of Sociology, Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University, Lucknow, India

Kameshwar Choudhary

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Bhattacharyya, S.K. (2023). Exploring B. R. Ambedkar’s Sociology: A Biographical Approach. In: Nagla, B.K., Choudhary, K. (eds) Indian Sociology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-5138-3_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-5138-3_7

Published : 01 November 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-99-5137-6

Online ISBN : 978-981-99-5138-3

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

All About Ambedkar

Issn 2582-9785, a journal on theory and praxis, on economics, banking and trades: a critical overview of ambedkar's “the problem of the rupee”.

Janardan Das

The Problem of Rupee is 257-page long paper written by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar that he presented as his Doctoral thesis at the London School of Economics (LSE) in March 1923. In it, Ambedkar tried to explain the troubles that were associated with the national currency of India - the Rupee. He argued against the British ploy to keep the exchange rate too high to facilitate the trade of their factory products.

In this article, I have tried to summarize the aforesaid book by Dr. Ambedkar. I have also tried to focus on how he advances his speech depicting the ups and downs of the Indian economy and currency. He introduces us to the characteristics of trade and business in our country even from the time when it was divided into several monarchical regions. He proclaims that in our country, the trade of any product had been conducted through the exchanges of money and those particular products. So evidently our merchant society is typically crowned as a pecuniary society that only runs on money.

Quoting W. C. Mitchell, Ambedkar reiterates that economists say money is pivotal to every individual in a society. And without the use of money, the distribution of anything can be a matter of disagreement and disturbance. In the next few lines of his speech, in the first chapter, he describes how the standards and currency were in the time of the Mughal empire and he certainly mentioned that the economic condition of the country was far better than that of today's, because it had a world-wide boundary of trade and free use of gold mohur and the silver rupee . Actually, before the administrative and financial invasion of British, Gold and silver were the inevitable parts of the medium of exchange without any fixed ratio. Hindu emperors and the Muslim emperors had some similarity in their trading features- both of them had a permissible use of metal coin in their empire but in the Mughal empire silver coins were at the center of currency, and later gold coins took that place in the Hindi empires. Mohur and rupee were similar in size, weight and composition. But the silver currency was unknown or more precisely unpopular to the southern part of the great Indian sub-continent because of the failure of Mughal administration. Instead of such coins, they normalised pagoda , the ancient gold coin traditioned from the time of Hindu kings. Mughals made allowances to recuperate the problems regarding faulty technology of the mints. Dr. Ambedkar observes that Mughals had initiated a system of provincial mints that had been maintained or ruled by a single unit or division. That made it easy to examine the issues related to monetary funds or mints. But later, these issues continued to be grow larger and made the poor and ignorant people suffer. He also tried to conjugate the great re-coinage of 1996 (?) . In the last half of the chapter, Ambedkar compared the coins as well as the rupee in every possible way.

Our country was divided into three presidencies during the British rule. So the British government set their target to change the parallel standard popular in Mughal times into a double standard by establishing an authorised ratio of exchange between pagoda , rupee , and mohur . But somewhere their effort partially went in vain. He gave a pictorial glimpse of how Bengal took this effort and tried to fix that ratio. Mainly, these types of attempts were taken and recommended by the Court of directors. But these steps were left to carry out by many of the provincial governments of India. In the first chapter of the problem of the rupee, Dr. Ambedkar explained how silver standards had been established through the vanishing of gold currency and how it had been supplemented by the paper currency. He also retorted how the Act XXIII of 1870 actually introduced nothing new - neither the number of the coins authorised by the mints nor its tender-powers. Rather, it helped just to make some improvements in monetary laws. Since the invention of coinage people always thought that the actual value of the coin can be exact with the price of the coin legalised by the mint. So according to him, the exact value of the coin can’t however always be the same as the certified value. That’s why in foreign countries, coins will not be legal tender if they vary from their legal standards beyond a certain limit. So, making coins legal tender without defining a certain limit to its toleration certainly makes way to cheat. Convincingly, the Act set a certain legal limit to the coins of its tolerance. The act also made an improvement that was to recognise the principle of free coinage. But we can not say that this principle of free coinage was perfect in every possible way as Ambedkar himself once said in this chapter that the principle had not been paid that much attention it deserved. Though it was the very basis of well-established currency in that it has an important bearing on the cardinal question of the amount of currency inevitable for the transactions of the people. According to Ambedkar, to solve this problem, two ways can be very useful to regulate such a huge quantity of transactions. One possible way is to close the mints and to leave it to the judgment of the government to handle the currency to suit our needs. The other way is to keep the mint as it is and to leave it to the self-interest of individuals to determine the amount of currency they need. Ambedkar aptly indicated both of the similarities and contradictions of the above-mentioned Act with the other ones where surely, he finds its incapability to regulate such a large quantity of currency.

In the introduction to the third chapter, Ambedkar was concerned about the economic results of the disturbance of the ‘par’ of exchange and he narrates it as the most “far-reaching character”. Our economic world can be sectioned into two neatly defined groups of people. These two categorised community had learned to use gold and silver and their standard money or purchasing standards. By giving a reference to 1873, he said that when a large amount of gold becomes equal to a large amount of silver, it barely matters for international transactions. It doesn’t make so much difference in which of the two currencies its obligations were stipulated and realized. But due to the dislocation of the fixed ratio or par, it becomes hard to indicate particularly how much silver is equal to how much of gold from one year to another, even from month to month. This exactitude of value which is the pivotal potential of monetary exchange, makes space for ambiguities of gambling. So, flatly all countries weren’t drawn to this center of perplexities in the same degree and the same extent; but yet it’s impossible for a nation which is a part of the international commercial world to escape from being dragged into it. This was true of our country as it was of no other country. India was a silver-standard country bound to a gold-standard country, so that her economic and financial picture was at “the mercy of blind forces operating upon the relative values of gold and silver which governed the rupee-sterling exchange.” Later in the discussion, Ambedkar pointed out the burdens of Indian economy and introduced us to an index [Table-XI] chart regarding the rupee cost of gold payments which showed data from year to year. If we give pay attention to the points figured out by Ambedkar, we can see that these burdens never stop, rather it’s been increasing day by day. Gradually, it caused various policies of high taxations and rigidity in Indian finance. Dr. Ambedkar brilliantly analysed Indian budgets between 1872-1882 and he proved that hardly a year passed without making an addition to the everlasting impositions on the country. He also analysed the information found in Malwa Opium Trade and was able to find errors in the economic policies of the Indian government. The taxes that the government standardized in these trades probably help the Indian economy to feel secure around the end of 1882. The government started exercising the virtue of economy along with the increment of resources. They found cheap agency of native Indians instead of employing imported Englishmen. And it was easy to use native intellect because the Educational Reforms of 1853 clearly says about the access of natives in Indian Civil Service. Thus, he finds the British try to set up a strong economy in India under the British Raj.

In the fourth chapter of the book, Ambedkar focuses on how the establishment of a stable economic system was dependent upon the re-establishment of a common standard of value. As it was the purpose just to normalise a common standard of value, its fulfillment was by no means an easy matter. The government found mostly two ways to make an experiment or practice. First thing was to declare any of the common metal as the standard currency and the second was to let gold and silver standard countries keep to these metal currencies and to establish a fixed ratio of exchange as to turn these to metal into a common standard of value. The first idea of normalising metal currency other than gold and silver was to make other countries leave their standards in favour of gold. If we look back at the history of movements for the reform of the Indian currency, we will mainly find two movements. The movement that led to introduce a gold standard first occupies this field. Dragging a reference to a ‘Report of the Indian Currency Committee’ of 1898, Dr. Ambedkar said that the notification of 1868 had bluntly failed and this failure doesn’t affect the history because the movement had already started earlier in the sixties and the movement had still life in it. Clearly, it is shown by the fact that it was revived four years later by Sir R. Temple, when he became the Finance Minister of India, in a memorandum dated May 15, 1872.

In the next few lines, Dr. Ambedkar talks about the second movement for the introduction of the gold standard that was conducted by Colonel J. T. Smith, the able Mint Master of India. Frankly, Dr. Ambedkar mentioned that his plan was a redress for the falling exchange. In this topic, he quoted the actual speech of Smith that was published in 1876 in London. Depicting the whole principle behind the presentation of J. T. Smith, Baba Saheb found it was considerably supported by the fall of silver in British India.

Now in the fifth chapter, we come to know that once somewhere Indian economic system felt that the problem of an erosive rupee was favourably dissolved. The long-lasting concerns and niceties that lingered over a long period even for a quarter of the century could not but have been successfully compensated by the adoption of a redress like the one mentioned in the fourth chapter. But unfortunately, the system originally planned, failed to be designed into reality. In its place, a system of currency in India grew up which was the very reverse or contradictory of it. A few years later when the legislative sanction had been shown the recommendations and suggestions of the Fowler committee, the Chamberlain Commission on Indian Finance and Currency said that the government contemplated to adopt the recommendations made by the committee of 1898, but the contemporary system utterly differs from the plan and had some common feature with the theory and suggestions made by Mr. A. M. Lindsay.

According to Mr. Lindsay’s scheme, he emphasised on how to turn the entire Indian currency to a rupee currency; the government was to give rupees in almost every case in return for gold, whereas gold for rupees only in foreign dispatch of money. The project was to be implicated through the assistance in between of two offices, one was in London and the other located in here, India. The first was to sell drafts on the latter when rupees were wanted and the latter was to sell drafts on the former when gold was wanted. Unbelievably, the same or similar system prevailed in our country. It was rejected in 1898. Then gradually paper currency came up to the Indian economic realm and two reserves one of gold and other of currencies left other than gold. Ambedkar had lengthened his discussion over Indian currencies after these events.

In the sixth chapter of the book, Dr. Ambedkar said about a memorable thing that was to remind the time when all the Indian Mints were shut down to the free coinage of silver. and the economic world in India was surely divided into two parties, one in favour of the step and the other stood in opposition to the closure of the mints. Being placed in an embarrassing and contradictory position by the fall of the rupee, the British Government of the time felt anxiety to close the Mints and increase its value with a conception to sigh in relief from the burden of its gold payments. Whereas it was requested, to produce an increment of interest of the country, that such accretion in the exchange value of the rupee would cause a disaster to the entire Indian trade and industry. One of the reasons, it was argued, why the Indian industry had advanced by such leaps and bounds as it did from 1873 to 1893 was to be found in the bounty given to the Indian export trade by the falling exchange. If the fall of the rupee was discovered by the Mint closure, everyone feared that such an event was certainly bound to cut Indian trade both ways. It would give the silver-using countries a bounty as over against India and would deprive India of the bounty which is obtained from the falling exchange as over against gold-using countries.

However, in the seventh as well as the last chapter of the book, Ambedkar examined the system of the economy that was advancing towards the changes of the exchange standard in the light of the claim made on behalf of it. Though it is very much a matter of uncertainty and hard to explain the history of Indian banking, but sure if being followed, it will be easy to interpret the market, values of products. Unmistakably, the works of Ambedkar led the nation towards the development and advancement of its economics and international banking and trades.

Works Cited

Ambedkar, B. R. History of Indian Currency and Banking. Butler & Tanner Ltd.

______________. The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India. P. S. King & Son Ltd., 1925.

______________. The Problem of the Rupee. P. S. King & Son Ltd., 1923.

Author Information

Janardan Das studies English literature at Presidency University, Kolkata.

Centenary of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar's enrolment as an advocate

- Certificate

- Application

- Mahad Satyagraha

- Publications

- Photo Gallery

Photo Credit : High Court of Bombay

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891-1956) was born on 14 April 1891 in Mhow Cantonment, Madhya Pradesh. He completed his primary schooling in Satara, Maharashtra and completed his secondary education from Elphinstone High School in Bombay. His education was achieved in the face of significant discrimination, for he belonged to the Scheduled Caste (then considered as ‘untouchables’). In his autobiographical note ‘Waiting for a Visa’, he recalled how he was not allowed to drink water from the common water tap at his school, writing, "no peon, no water".

Dr Ambedkar graduated from Bombay University in 1912 with a B.A. in Economics and Political Science. On account of his excellent performance at college, in 1913 he was awarded a scholarship by Sayajirao Gaikwad, then Maharaja (King) of Baroda state to pursue his M.A. and Ph.D. at Columbia University in New York, USA. His Master's thesis in 1916 was titled “The Administration and Finance of the East India Company”. He submitted his Ph.D. thesis on “The Evolution of Provincial Finance in India: A Study in the Provincial Decentralization of Imperial Finance”.

After Columbia, Dr. Ambedkar moved to London, where he registered at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) to study economics, and enrolled in Grey’s Inn to study law. However, due to lack of funds, he had to return to India in 1917. In 1918, he became a Professor of Political Economy at Sydenham College, Mumbai (erstwhile Bombay). During this time, he submitted a statement to the Southborough Committee demanding universal adult franchise.

In 1920, with the financial assistance from Chatrapati Shahuji Maharaj of Kolhapur, a personal loan from a friend and his savings from his time in India, Dr. Ambedkar returned to London to complete his education. In 1922, he was called to the bar and became a barrister-at-law. He also completed his M.S.c. and D.S.c. from the LSE. His doctoral thesis was later published as “The Problem of the Rupee”.

After his return to India, Dr Ambedkar founded Bahishkrit Hitkarini Sabha (Society for Welfare of the Ostracized) and led social movements such as Mahad Satyagraha in 1927 to demand justice and equal access to public resources for the historically oppressed castes of the Indian society. In the same year, he entered the Bombay Legislative Council as a nominated member.

Subsequently, Dr. Ambedkar made his submissions before the Indian Statutory Commission also known as the ‘Simon Commission’ on constitutional reforms in 1928. The reports of the Simon Commission resulted in the three roundtable conferences between 1930-32, where Dr. Ambedkar was invited to make his submissions.

In 1935, Dr. Ambedkar was appointed as the Principal of Government Law College, Mumbai, where he was teaching as a Professor since 1928. Thereafter, he was appointed as the Labour Member (1942-46) in the Viceroy’s Executive Council.

In 1946, he was elected to the Constituent Assembly of India. On 15 August 1947, he took oath as the first Law Minister of independent India. Subsequently, he was elected Chairperson of the Drafting Committee of the Constituent Assembly, and steered the process of drafting of India’s Constitution. Mahavir Tyagi, a member of the Constituent Assembly, described Dr. Ambedkar as “the main artist” who “laid aside his brush and unveiled the picture for the public to see and comment upon”. Dr. Rajendra Prasad, who presided over the Constituent Assembly and later became the first President of the Indian Republic, said: “Sitting in the Chair and watching the proceedings from day to day, I have realised as nobody else could have, with what zeal and devotion the members of the Drafting Committee and especially its Chairman, Dr. Ambedkar in spite of his indifferent health, have worked. We could never make a decision which was or could be ever so right as when we put him on the Drafting Committee and made him its Chairman. He has not only justified his selection but has added luster to the work which he has done.”

After the first General Election in 1952, he became a member of the Rajya Sabha. He was also awarded an honorary doctorate degree from Columbia University in the same year. In 1953, he was also awarded another honorary doctorate from Osmania University, Hyderabad.

Dr. Ambedkar's health worsened in 1955 due to prolonged illness. He passed away in his sleep on 6 December 1956 in Delhi.

References:

- Vasant Moon (eds.), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings And Speeches, (Dr. Ambedkar Foundation, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India, 2019) (Re-print)

- Dhananjay Keer, Dr. Ambedkar Life and Mission, (Popular Prakashan, 2019 Re-print)

- Ashok Gopal, A Part Apart: Life and Thought of B.R. Ambedkar, (Navayana Publishing Pvt. Ltd., 2023)

- Narendra Jadhav, Ambedkar: Awakening India's Social Conscience, (Konark Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2014).

- William Gould, Santosh Dass and Christophe Jaffrelot (eds.), Ambedkar In London, (C. Hurst and Co. Publishers Ltd., 2022).

- Sukhadeo Thorat and Narender Kumar, B.R. Ambedkar: Perspectives on Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policies (Oxford University Press, 2009).

- Constituent Assembly Debates

Subscribe Now! Get features like

- Latest News

- Entertainment

- Real Estate

- Lok Sabha Election 2024

- My First Vote

- IPL Match Today

- IPL Points Table

- IPL Purple Cap

- IPL Orange Cap

- The Interview

- Web Stories

- Virat Kohli

- Mumbai News

- Bengaluru News

- Daily Digest

- Election Schedule 2024

Chronicling BR Ambedkar’s life in London

The time he spent in london earning his law and second doctorate degrees was among the most important part of the polymath’s life. the interrupted stint shaped his worldview and philosophy, introduced him to new and exacting teachers, and sharpened his legal skills.

When BR Ambedkar stepped off the boat in London in the summer of 1916, he was already an accomplished man. The 25-year-old had a PhD degree in economics from Columbia University and his dissertation Castes in India: Their mechanism, genesis and development was making waves for its theoretical underpinnings of endogamy.

But he was worried. He was dependent on an endowment from the Gaekwads of Baroda and was likely to be called back soon; World War I had thrown the western world into uncertainty — a ship carrying Ambedkar’s luggage was sunk by Axis torpedoes in the Mediterranean a few months on; his finances were dwindling and friends were back in New York.

Despite the challenges, the time he spent in London earning his law and second doctorate degrees was among the most important part of the polymath’s life. The interrupted stint – he was in London between 1916 and 1917, and again between 1920 and 1923 – shaped his worldview and philosophy, introduced him to new and exacting teachers, and sharpened his legal skills.

Most pivotally, it threw in sharp relief the young Ambedkar’s caste-blighted life in India with his student years abroad. “My five years of staying in Europe and America had completely wiped out of my mind any consciousness that I was an untouchable, and that an untouchable wherever he went in India was a problem to himself and to others,” he later wrote in Waiting for a Visa, narrating how no one would rent him a hotel room when he returned because he was considered untouchable.

A new online exhibition at the London School of Economics (LSE) aims to explore these formative years for Ambedkar through physical papers and records available at the institution.

“Our archives consist of the personal papers of individuals or of organisations. We don’t have the archives of Ambedkar …However, we do have a collection of student files, which record the interactions students have with the LSE during their period of study here. And there is a student file of Ambedkar, which is composed of thing such as his application forms and letters to the secretary. This is what the exhibition is based on,” said Daniel Payne, Curator for Politics and International Relations at the LSE library.

The bulk of the exhibition is an annotated history of Ambedkar’s life and works, with additions on prominent LSE teachers at the time and Indian alumni. The exhibition doesn’t have much on his time at LSE except somewhat charming pieces of university bureaucracy – a misfiled form, handfilled applications for degrees and a partially filled attendance sheet. All of these can be downloaded by the user and hold importance, given that Ambedkar filled most of them himself.

“The principal motivation behind curating this online exhibition is that the several radical (in his time and ours) thoughts and ideas Dr B R Ambedkar — who is by any measure the most famous Indian alumnus of LSE — have remained remarkably unknown to the international academic community,” said Nilanjan Sarkar, deputy director of the LSE South Asia Centre. “Through our limited archival collection in LSE Library, we have tried to highlight this potential for the international community — in short, to globalise the energy and force of Dr Ambedkar’s thought, and to underline its continuing relevance for our times.”

Ambedkar, the economist

Ambedkar’s evolution as an economist occupies a central place in the exhibition.

During his time at LSE, Ambedkar submitted two thesis – one called The evolution of provincial finance in British India : A study in the provincial decentralization of imperial finance for his master’s degree in 1921 and the other, more famous, The Problem of the Rupee, that later influenced the setting up of the Reserve Bank of India, in 1922.

LSE records say that his thesis was not accepted at first, and later notes add that the colonial examiners found his work too “revolutionary”. Ambedkar later revised the work, and successfully obtained a doctorate.

Another important piece of work by him was the 1918 paper Small Holdings In India And Their Remedies where he explored India’s fragmented holdings and called for industrialisation of agriculture to absorb the surplus labour.

Niranjan Rajadhyaksha noted in a 2015 Mint column that Ambedkar’s thesis came at a time when there was a clash between the colonial administration and Indian business interests on the value of the rupee. In his work, Ambedkar argued in favour of a gold standard as opposed to the suggestion by John Maynard Keynes that India should embrace a gold exchange standard.

From the late 1920s, Ambedkar largely moved away from economics as he devoted his energies to social and legal reform, but his later stint as the labour minister in the Viceroy’s executive council between 1942-46 was deeply impactful.

“He worked on a diverse set of topics - water policy, electric power planning, labor laws, maternity rights for female factory workers…Babasaheb set up the first employees’ state insurance, a social security and health insurance scheme for workers, in South Asia,” said Aditi Priya, a research associate at Krea University and founder of Bahujan Economics.

In a 1998 publication, Ambedkar’s Role In Economic Planning, Water And Power Policy, Sukhadeo Thorat traces the impact of Ambedkar’s ideas around state planning on post-independence concepts like the adoption of river valley authorities and hydropower development.

“The importance of maternity entitlements has been discussed in both econ and policy circles in improving the welfare of pregnant and lactating women and improving the labor force participation. Babasaheb was the first advocate of the maternity bill. He passed a range of laws protecting female workers including the Women and Child Labour Protection Act, the Maternity Benefits Act, the Mines Maternity Benefits Act, and created the Women Labour Welfare Fund, which was used to safeguard health and safety of working women,” Priya added.

Ambedkar scholars agree that his primary thrust in later life was on social welfare and benefits to marginalised groups – without being an outright socialist.

“For him the idea was that the welfare of the people should primarily be the job of the government. He was a strong advocate of the role of the state in inclusive economic growth and development and at the same time he was also in the favor of industrialization and urbanization. But he was also aware of the ills of capitalism,” said Priya.

Ambedkar, the student

There are two things the exhibition does very well.

One is underlining Ambedkar’s relations with his teachers and the impression he had on them. Plenty has been written on the influence of Edwin Seligman at Columbia University and the writings of John Stuart Mill.

The LSE exhibition shows Ambedkar enrolled in Geography with Halford Mackinder, Political Ideas with G Lowes Dickinson, and Social Evolution and Social Theory with LT Hobhouse. At the time, the fees were £10 10s which increased to £11 11s when he returned in 1920. His attendance records indicate he was not too interested in the political ideas class, which he skipped on all but two occasions during a term.

The exhibition also spotlights Ambedkar’s relationship with Edwin Cannan, the liberal economist whose lectures are said to have laid the foundation of the LSE Economics course and Herbert Foxwell, who taught at LSE since it started in 1895, and famously said about Ambedkar in London, “There are no more worlds for him to conquer.”

Cannaan guided Ambedkar through the tense submission and re-submission of his doctoral thesis and the young scholar dedicated the work to his professor. The papers have little on their interaction but it appears that the two kept in touch, especially when Ambedkar came back to London for the Round Table Conferences in the early 1930s.

Ambedkar’s student file also contains a letter from Cannan to William Beveridge (then director of the LSE) to encourage him to entertain Ambedkar. “I always said he was by far the ablest Indian we ever had in my time,” Cannan says of Ambedkar.

The letter also references the bitter tussle between Ambedkar and Gandhi over the issue of separate electorates – Gandhi wanted to keep Dalits within the Hindu fold and refused to allow them separate franchise, while Ambedkar believed that caste Hindus would thwart Dalit representatives in a joint electorate.

“When I read in the papers that the Brahmins were hoping to persuade, or that Gandhi was…Dr Ambedkar to modify his demands, I chuckled, remembering the obstinacy with which he used to hold out even when quite wrong,” Cannan noted.

Ambedkar, the political thinker

The second is highlighting the evolution of political thought in Ambedkar – from his days at LSE to when he returned to London for the Round Table Conferences.

To my mind, the most important documents in the entire exhibition are two sets of papers that have nothing to do with LSE.

One is a missive by Ambedkar to George Lansbury, the then leader of the Labour Party, in 1935. At the time, a British joint parliamentary select committee, chaired by Lord Linlithgow, had tabled its recommendations – which would eventually lead to the Government of India Act, 1935.

Ambedkar expressed dissatisfaction in his letter to Lansbury, especially objecting to the proposal for setting up upper houses in provincial assemblies over fears that upper-castes will dominate these chambers and wield influence in governance.

The second is the submission by Ambedkar and Tamil politician Rettamalai Srinivasan – the two depressed class delegates – to the First Round Table Conference, laying out a political and electoral roadmap for Dalit representation in power-sharing.

A Scheme of Political Safeguards for the Protection of the Depressed Classes in the Future Constitution of a self-governing India puts forth a series of conditions for Dalits to agree to majority rule in India – each of which acts as a precursor for rights and provisions that eventually found their way into the Constitution.

Ambedkar and Srinivasan said Dalits needed equal citizenship, fundamental rights, free enjoyment of equal rights, protection from social boycott and other discrimination, adequate representation in services, departments and the Cabinet. The kernel of the landmark abolition of untouchability, affirmative action and fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution are evident in this short 13-page submission. Also evident is the tension between historical inequality and the democratic project – key to understanding the country celebrating 75 years of freedom.

In the words of Ambedkar, “The depressed classes cannot consent to subject themselves to majority rule in their present state of hereditary bondsmen. Before majority rule is established, their emancipation from the system of untouchability must be an accomplished fact. It must not be left to the will of the majority.”

And what we don’t know

Yet, there is so much that’s missing from the exhibition on Ambedkar’s life at London or LSE. We don’t know what sort of a student he was, how his time at London was spent or how a young Dalit scholar enjoyed the first years of freedom from the sub-continental shackles of caste.

Other than the passing references in Ambedkar’s biography by Dhananjay Keer, we don’t know anything about his roommate Asnodkar, his friend Naval who’d send him money or his stern landlady who’d make him subsist on toast.

We don’t know how he navigated the metropolis, who his British friends were and the stories of the Indian acquaintances who supplied him with papad to eat at night.

Did Asnodkar and Ambedkar talk during the latter’s frequent all-nighters? Did Ambedkar make any friends during his hours-long visits to the British Library? Who took care of him when he fell ill in 1922? We don’t know.

Coming in the 75th year of India’s independence, this is both unfortunate and predictable.

The domination of upper-castes in history, historical research and archiving meant that even otherwise commonplace tasks like publishing Ambedkar’s complete works happened decades after his death, after struggle by anti-caste groups. Dalit writers and intellectuals continue to be marginalised and typecast.

Even in the UK, Ambedkarites have worked for years to establish Ambedkar as a leading figure. “When we started working in 1985, not many knew of Ambedkar; during his birth centenary celebrations (in 1991), we organised events across Europe to highlight his contribution to democracy and human rights,” said Arun Kumar, general secretary of the Federation of Ambedkarite & Buddhist Organisations. Busts donated by the body stand today at LSE and Columbia University.

The exhibition’s organisers are aware of the challenges.

“Even though there is quite a bit in the student file, not much is revealed about Ambedkar’s experiences at LSE,” said Payne.

Sarkar said that the principal motivation behind the exhibition was that the several radical thoughts and ideas of Ambedkar remained remarkably unknown to the international academic community.

“Even though Dr. Ambedkar is one of the most significant alumnus of LSE, and Dr Ambedkar’s scholarship and campaigns are of paramount importance to understand India and beyond, despite the presence of large number of Indian students as well as some faculty research on India, it is almost invisible in this institution,” said Jayaraj Sunderasan, one of the organisers of the event.

Following Babasaheb’s footsteps