The Value of Failure in Grad School

by becca_cassady | Sep 29, 2020 | Beth Allison Barr author , graduate student advice , Uncategorized | 0 comments

My husband suggested once that I have lunch with a friend. She was a graduate student, and struggling in the program. “Did you tell her I almost quit?” I asked. “Oh, yeah,” my husband said. “That is why I thought you should talk with her.”

Graduate school is one of the hardest things I have ever done. Although I am grateful for the excellent program I attended and my superb adviser, I have no desire to return to my graduate years.

I expected the painful work load, the never ending research projects and papers, the complete lack of sleep for days on end, and even the political drama among both faculty and students.

What I didn’t expect was how much I would fail.

Just to name a few of my early failures: I failed a language exam (quite spectacularly, actually). I received what-I-hoped-would-become-the-beginning-of-my-thesis back with the words, “This wasn’t worth my time,” scrawled across the front. I taught the 1381 English peasant revolt completely wrong during a teaching observation. I never managed to understand the questions in Latin one professor insisted on asking me every time we crossed paths (which was way too often for my stress level!). And, although I know my current students may not believe this, I almost never spoke up in seminar my first year. I was terrified of how much I didn’t know. It really seemed that everyone else had not only read Foucault and memorized all of his writings, but even understood Foucault so well that they could integrate him into every conversation we had. Everyone, except for me.

(And if you don’t know who Foucault is, no worries. If you are a STEM student, it doesn’t matter. If you are a Humanities student, it still probably doesn’t matter unless you are in a field related to Philosophy, Religion, Literature, and/or History. If it makes you feel better, you can learn about Foucault here ).

I could go on, but I think you get the point. I failed a lot.

In fact, I became convinced my first year that I couldn’t do it. When I admitted to my husband that I couldn’t finish the PhD, I really felt like a failure. But, during our conversation, another option began to emerge. I should finish my MA (the first two years). If I still felt strongly about quitting, then I could exit the program. This cheered me up. I could do it for one more year. There was an end in sight which included an advanced degree. And so that became my plan. I realized that failing wasn’t the end of the world–life would go one, and I would be okay.

It was at this point that everything changed. By giving myself permission to fail, I learned how to succeed.

I no longer worried about Foucault in seminar. I knew other things, and really enjoyed most of the other readings, so I talked about those. I didn’t talk as much as my cohorts, but I began to talk more and with greater comfort. No longer paralyzed by the fear of failure, I engaged with my peers both inside and outside of seminar. Soon I began to talk about Foucault myself (especially after I actually read him!).

I also became more adventurous in my writing. By trying to write the way I thought an academic text should be, I had become a truly awful writer (which maybe says something about the academic texts I was reading…). But when I returned to the way I liked to write and to the topics I enjoyed (women and religion), I got better.

Indeed, my entire performance improved dramatically. I remember so clearly reading my end-of-year evaluation. It stated, “Beth blossomed this year.”

For the first time I knew I could complete the PhD.

So for those of you in graduate school struggling with the stress of the program, with the fear of failure, and with uncertainty about the future, I have some advice.

- It really is okay to fail. Failure shows us what we need to change. It showed me that I needed to take my Latin exam in medieval Latin, not classical (and the second time around I scored a 98). It showed me that I needed to write about what I found interesting–not what I thought would interest my cohorts and program faculty. It also showed me that failure wasn’t the end of the world. I survived all my failures, and even if I had chosen to drop out of the program, I know I still would have been okay. Failure no longer meant the end; rather it served as a signpost that I needed to do something different.

- It really is okay not to know everything. Talk about the things you do know; the things that interest you (not the things that you think will make you look smart). Instead of worrying about what others would say, I started thinking about what was most useful from the seminar readings for my own research. And then I talked about those points in class. Wow! This dramatically changed my seminar performance.

- It really is okay for people to disagree with you. It really is. This doesn’t mean you are wrong; it doesn’t mean you have to capitulate to their point. It just means that you need to rethink or perhaps rephrase your argument. Now I find it quite helpful when people disagree with me, as it often suggests a new perspective I hadn’t considered.

- It really is okay to feel like a failure. Everyone feels like a failure at some point in graduate school. Female academics often talk about “ imposture syndrome ,” where, even after achieving a PhD, women in academia continue to feel inadequate and even fraudulent. But instead of letting fear paralyze you, talk to your fellow graduate students about how you can help each other (I guarantee they are struggling with you). If you are struggling with coursework readings, form a study group. If you are struggling with writing, form a writing group (see my post about how to do this). If you are struggling to keep up with current research, then form an article group.

- Finally, do something other than graduate school with your time. I recommend church involvement–and I don’t just mean going to church. I mean volunteering your time in church, like serving on worship team, hosting a small group, holding babies in church nursery, or (my favorite!) mentoring teenagers and serving in youth group. By getting out of the graduate school bubble, you will widen your perspective and realize life is much more than about you. This helps so much. It helps put your graduate school failures into proper perspective. Serving others is also fundamental to the Christian life……as Jesus himself said, “For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve others, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” Mark 10:45

You will fail in graduate school. I guarantee it. But this doesn’t have to be a bad thing.Failure teaches us that we have to change. It helps us develop problem-solving skills and familiarizes us with confrontation. It also helps us admit that we need help.

I don’t know about you, but these seem like pretty valuable life lessons to me.

Have a topic you want us to address on the blog? Email Becca Cassady at [email protected] or tell us through our Qualtrics survey .

Share this:

Trackbacks/pingbacks.

- What Do You Do In Grad School? – Almazrestaurant - […] So for those of you in graduate school struggling with the stress of the program, with the fear of…

- Is It Ok To Fail In Grad School - MINDFULNESS IN COLLEGE AND GRAD SCHOOL - […] school is all about failing. In fact, you should fail ever day until you eventually get it right. The…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

Academic Challenges: How to Overcome PhD Problems and Academic Failure

Completing a PhD can be difficult . No matter how much planning you do, there will almost certainly be times when academic challenges mean that things don’t go the way you’d like them to.

Today I want to illustrate some of the academic failures I experienced with my own PhD. I hope that sharing these PhD problems and what I learned may help you. Or if nothing else reassure you that you’re not alone!

This list certainly isn’t complete, but I want to give a flavour of wide-ranging failures, starting from PhD applications through to the completion of my project.

A reader suggested the topic of academic challenges. If you have a suggestion for something you’d like covered please leave a comment or send me a message .

Academic Challenges During My PhD Applications

1) taking three years of applications to get a funded phd position.

Academic failure: I applied for my first PhD position the year after I finished my undergraduate degree. But I didn’t actually start a PhD until three years’ worth of applications later.

I made the mistake of not casting a wide enough net and failed to consider how important funding is. I naively thought that as soon as I got offered a place I was sorted. Little did I realise that funding can be the main hurdle.

Over these three years I applied to only five projects in total:

Key learnings

Although I got offered a place for the first PhD I applied for back in 2013, I didn’t secure any funding. Now I know that getting accepted without funding doesn’t necessarily mean much!

I spent those years whilst I was applying gaining experience working as a research assistant in different universities. This extra experience (and name on papers) helped enormously to secure the funding I eventually took: a university-wide scholarship.

Each department only put forward one applicant (their strongest, supposedly) and from this department-wide pool only one scholarship was awarded. I certainly wouldn’t have been considered an outstanding applicant based off of just my undergraduate experience.

With some persistence it all worked out in the end. In hindsight I’m much happier with the project I ended up doing than if I’d gone for the one as intended at the start! Even so, it is easy to see how someone could have given up after the first failure in securing funding.

Application tips :

- Cast a wide net . Generally, more applications mean a higher chance of getting a funded project. Also, consider looking abroad. One of my regrets is not having applied for a PhD abroad, or at least tried to spend some time abroad as part of my project.

- Persistance pays off with PhD applications. If you like the work of certain researchers get in touch with them and stay in regular contact.

2) Failure in my basic biology knowledge at interview

Academic failure: Of my five PhD applications, I got rejected at interview stage for the Synthetic Biology CDT at Oxford.

It turned out that although the course was intended for non-biologists who were entering the field for the first time, I still didn’t have enough biology experience. One of the questions they asked was what DNA stood for: I didn’t have a clue!

Read about all my PhD interview experiences here .

Firstly, we can’t be good at everything!

Especially if you’re looking to change fields, it can be tricky to quickly get up to speed. This is particularly true when you have no idea what you’ll get asked at interview.

In my experience, once you start a PhD project it is actually a more forgiving environment, allowing you to build up your knowledge. So don’t worry too much that you need to know everything before you start. Even so, I felt like a bit of a failure walking out of that interview not being able to answer a relatively basic question!

Now I have a bit more experience I’d suggest demonstating your knowledge and capabilities with actual experience where you can.

I appreciate that this can be difficult but it could simply be a case of completeting a free online course. Doing so in my own field helped a lot with securing my current post-doc position. Having something tangible to support your application can go a long way. It also helps to slightly take the pressure off any awkward interview questions.

Academic Challenges During My PhD Project

Failing to reproduce published results.

Academic failure: For months I couldn’t acheive similar results to a previous study in the literature. The method was going to enable the main work of my PhD project and I had already spent a good chunk of my project budget trying to get it working. I was sure I was following the method precisely, and even emailed the authors looking for support. I never receied a reply and never did get the method working exactly as described in their paper.

Thankfully, after some more experimentation, we got a technique which worked. It even turned out to be better suited for our application than the method I was trying to reproduce. These developments lead to my first paper .

I got lucky that we found a method which worked before we ran out of money and time on the project. It could have gone very differently if we’d not tried other methods but it’s also worth saying how important it is to look to mitigate risks like this.

It is always worth being aware of how much time/money you have left. At an early stage start thinking “if I don’t have X done in Y weeks, we ought to look at doing something different”. Persistence is important with academic challenges but so is adapability.

- Is there someone in your group or university who already does what you’re trying to do? Be polite and make use of their expertise.

- Read a lot of literature to gain a solid understanding of the range of methods usually utilised. The ones which are used more often may be more reproducable and could be a good starting point.

- Reach out to authors of other studies but don’t expect them to reply.

- Try to iterate quickly to improve your chances of success.

- Make a plan B ! This is so important. Be prepared to pivot to something else if things don’t work out.

- Also, there is a reproducability issue in academia. At the very least when you come to write up your own research make sure to describe your methods in detail to help future researchers.

Failure to access equipment

Academic failure: A large part of my project depended on accessing a good quality micro-CT scanner and I didn’t have easy access to one. I spent months trying to find good reliable access. There were a few around the university but most groups and departments wanted to keep them to themselves.

I ended up using the one at the nearby Natural History Museum, and for the most part this worked out well. The only problem was that we had little control over it. We had to pay everytime we wanted to use it and had to book a slot months in advance. This all meant that I could only run a very limited number of experiments throughout my PhD: putting a lot of pressure on each set of scans and ultimately dissuading me from taking too many [potentially exciting] risks.

It really isn’t ideal to rely on equipment you only have very limited access to and there is high potential for it to cause significant academic challenges.

Mid way through my PhD I thought all my prayers had been answered when my supervisor won a big grant. This included provision to buy our very own posh micro-CT scanner. I still had a few years left of my PhD so it seemed like a sure bet that I’d make good use of it.

Well the procurement process for such an expensive bit of kit was painstakingly slow. The equipment eventually got delivered to a new campus in a building which still wasn’t finished by the end of my project. I failed to ever even see the scanner let alone use it!

There is so much potential for things to go wrong when you don’t have easy access to equipment. In hindsight I would have better utilised the equipment I had easy access to and made that the backbone of my project. Other results would have then been a bonus.

- Don’t rely on using equipment housed anywhere outside of your lab. During my time at Imperial, even communal equipment meant for researchers across all departments was moved off-site which has potential to cause complications.

- Even for equipment in your group, think about what you’d do if the equipment stopped working tomorrow and wasn’t fixed. This type of thinking can actually help you come up with new ideas which could be useful side-projects.

Failures to get research papers published in target journals

Academic failure: Numerous times I’ve failed to get papers published in journals we’ve submitted manuscripts to. For instance one paper which is currently under review was rejected by two other journals previously. Another we got published on our second or third attempt.

I try to see individual rejections of papers by journals as academic challenges as opposed to failures. It is great to be striving to publish your work and especially if you’re aiming for popular journals it is inevitable that you’ll face some rejections. It could be argued that if you never get papers rejected you’re not being ambitious enough!

I’ve written a whole series of posts about publishing and you can find them here: Writing an academic journal paper series .

As much as you can try to perfect a paper in preparation for submission, there is an element of luck. Different reviewers are looking for different things, and their opinion of your work will likely also vary a bit depending on the mood their feeling at the time. Even if you submitted the same paper multiple times to the same journal (note: don’t do this!) you’d likely get a range of decisions.

In my opinion it is only a failure if you don’t try at least try and get any of your work published!

Failure in rig design and testing: the time my rig started leaking salt water inside very pricy equipment!!

Academic failure: As mentioned in a previous section, my PhD project involved using a micro-CT scanner at the Natural History Museum.

I designed and built a new rig to enable me to do in-situ mechanical testing: basically apply force to biological samples during scanning. We had to keep the tissue samples hydrated in liquid at all times, including during scanning, and often used PBS : a salty water solution. I had tested the rig in our lab before taking it to the museum and it seemed to work as expected. I knew that I had to be able to leave the equipment because the experiments were at least eight hours long each (and ran continuously) and it wasn’t feasible to stay near the machine 24/7 even if I’d wanted to.

In my first set of experiments using it at the museum we got it all set up and running. I stayed for about 30 minutes to check there were no problems, then left to get on with some other work for the day. All seemed fine. A few hours later I got a message from the technician running the equipment to tell me that he thinks the liquid level is going down inside my rig!

I race over there, immediately take it out and pray that we haven’t caused any damage to the equipment. Miraculously there was no long term damage, but it was a very near miss. If the technician hadn’t spotted it things could have gone very differently! For reference the scanner cost the best part of £1 million… eek!

Thankfully the problem with my rig was quick to fix but it would have been far better to avoid these issues in the first place.

- Double, triple or quadruple check that equipment is working as expected: especially for rigs and devices you’ve designed!!

- Mitigate risks. In my case, once we thought we’d resolved the issue we did a few more experiments with paper towel taped around the rig to ensure any spills would be soaked up. Yes, really.

Failure to stand my ground

Academic failure: for the most part I was lucky to not have many disagreements and regrets from my PhD. Even so, there are a few instances where in hindsight I wish I had held my ground and put a bit more thought into making sure I was getting the right outcome for myself and/or the research.

To give a tangible example: in the rush as I was finishing up my project I had to decide on a title for my PhD. I worked through some ideas with my main supervisor and someone else chimed in to take the title in a different direction which my supervisor said he thought was a good idea.

We met in the middle with a hybrid title. Soon after finishing up I regretted the choice but by then it was too late to make any changes so I’m stuck with what we chose. The title isn’t awful and it doesn’t need to define my PhD, but even so I do regret not putting in a bit more thought to what I wanted and diplomatically standing my ground.

Pick your battles, but do stand up for yourself. It is your PhD!

Bonus: failing to get elected to lead a student society (twice)

Not related to academic work, but I’ll include it as part of my time at university during my PhD.

The failure: I wanted to get involved with a student society which had disbanded by the time I joined the university. Myself and a few others started it back up again and I was keen to lead it.

I applied for the role of president and got rejected.

I ran for the position again the following year and got rejected for a second time.

Finally, as I was entering my final full PhD year, I got in on the third and final attempt!

Stick with something. Or maybe know when to move on?!

How to Deal with Academic Challenges During Your PhD

Reframing academic failure.

Facing academic challenges is part of the PhD process. If you’re doing something new it is inevitable that things will not go perfectly the first time. In fact, if things appear to have gone perfectly it more than likely means that something is wrong.

Despite the name of this post, try to think of these issues as challenges to overcome rather than failures. An academic challenge only becomes a failure if you’ve not made a reasonable effort to overcome the obstacle. For example, if you ignore something for several months or don’t tell your supervisor about it, then what could have been an easy fix can become a much bigger issue.

You’ll find it much easier to deal with something when it is framed as a research challenge, which can be exciting to overcome, rather than considering every setback as a personal failure.

I’d say that one of the most important parts of a PhD is to learn from your mistakes. This is an integral part of the PhD process and you’ll only be able to do this when you can objectively assess how things are going. Please don’t fall into the depressing valley of thinking about your work as a failure.

How to Mitigate the Risks of Academic Failure During Your PhD

- Communicate regularly with your supervisor. Communicating openly and often with your supervisor will ensure you’re both working together effectively as a team. Your supervisor should be a source of motivation and provide guidance on any academic challenges where necessary. If you meet regularly you can stop potential PhD problems in their tracks before they become big issues. I found meeting weekly to work well. If your supervisor is often too busy to meet that should be a warning sign which should also be addressed.

- Know the literature thoroughly . For most research topics, you’re not the first person to have asked the questions you’re looking to solve. Find out where other people have got to and build up your research from this. We can’t be experts in everything, but you should know how other researchers have conducted similar experiments to you. This should help you both to avoid academic failures and have a solid starting point from which you can begin adding your own twist – saving you months of headaches.

- Work hard but work smart . Certain academic challenges can be overcome simply by putting in the necessary effort. Check that equipment is working ahead of when you need it, do all the necessary calibration as often as necessary and don’t shy away from the effort required to try out different experimental procedures. But on the other hand, don’t work aimlessly otherwise you risk burning out. Work smart which ties in with the next point: planning.

- Make a plan. Know when you need to have achieved certain milestones by in order to stay on track. Mitigate risks by thinking about alternative routes of research in case things go wrong.

- Cut yourself some slack . We all make mistakes, don’t stress yourself out too much about small errors. Try to keep a level head and stay in a mindset where problems with your PhD don’t get you down too much. As long as you are making efforts to develop your skills and seeking to get closer to answering your research questions you’re on the right path.

I really hope that content such as this is useful in normalising academic failure. It is completely normal for problems to occur, but it is how you deal with these academic challenges which will define your PhD. Best of luck.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

How to Master Data Management in Research

25th April 2024 27th April 2024

Thesis Title: Examples and Suggestions from a PhD Grad

23rd February 2024 23rd February 2024

How to Stay Healthy as a Student

25th January 2024 25th January 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

10 steps to PhD failure

Kevin haggerty and aaron doyle offer tips on making postgraduate study even tougher (which students could also use to avoid pitfalls if they prefer).

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

Given the stakes involved, one peculiar aspect of graduate school is the number of students who seem indifferent to its pitfalls. Year after year many run headlong, like lemmings, off the same cliffs as their predecessors. Yet a good share of these people ignore or are even hostile towards the advice that might help them avoid screwing up.

Having repeatedly witnessed this process, we have concluded that a small group of students actually want to screw up. We do not know why. Maybe they are masochists or fear success. Whatever the reason, our heart goes out to them. Indeed, we hope to help them – by setting down a course of action that will ensure that they blunder through graduate school in a spectacularly disastrous fashion.

1. Stay at the same university

It can be tempting to obtain all three of your degrees (undergraduate, master’s and PhD) at the same university: you have already established personal and professional friendships there, you know the routines of the university, you have a solid working relationship with the academics, and you even have lined up a potential PhD supervisor who will incorporate you into an existing research project. However, if you actually want to succeed, doing so is probably a mistake.

Friends and colleagues often tell students to obtain their degrees at different universities, but seldom explain why. One reason is that departments have different strengths. Going to a different university or country exposes you to different perspectives. If you complete both your undergraduate and your master’s at one location, some say that you have probably got everything you can from the kind of scholarship and research practised in that department. (Whether this is true is a different matter.)

Going somewhere else for your PhD shows that you have expanded your intellectual horizons. In contrast, others will view the fact that you did all your degrees at the same place as an indication that you lack scholarly breadth and independence, and that you were not wise or committed enough to follow this standard advice about studying elsewhere.

2. Do an unfunded PhD

If you receive an offer for admission to a PhD programme that does not include funding, you should walk away. If the funding arrangement is vague, you should clarify it as much as possible to make sure that it has substance. While many master’s students are unfunded, the normal practice is for PhD students to be supported through scholarships, teaching, a supervisor’s individual research grants, or a combination of those things. An offer of admission without a financial package can be interpreted in several different ways, but none is encouraging.

Most obviously, it signals that the department is not committed to you. It can also be a sign of problems or even crisis in your department, university or discipline. Beyond what the lack of funding might say about how the admissions committee views you, an unfunded PhD will require you to support yourself through your course, research and writing your thesis. This precarious financial situation is demanding and can severely delay your completion.

3. Choose the coolest supervisor

Several years ago, I pulled aside a graduate student and advised her to find a different PhD supervisor. I delicately, but clearly, pointed out that her current supervisor had a record of relating poorly to others and was seen as a source of extreme irritation by many departmental colleagues.

The student was torn – for her supervisor was also charismatic, had published in prominent outlets, and had research interests that were reasonably close to her own. So she rolled the dice and maintained the relationship.

Three years later, the student sat in my office completely distraught. Her supervisor would not respond to emails and phone calls and was taking forever to comment on drafts of her thesis chapters. In essence, her supervisor failed her as a mentor, her degree was in crisis, and she needed to find a new supervisor quickly.

Screwing up your choice of supervisor is one of the biggest missteps you can make in graduate school. It is also easy to do. If you choose a supervisor because of a single overriding factor – such as a desire for someone who is personable, or is not intimidating, or has a big name – you risk choosing poorly.

So choose carefully, and do not let any one factor sway your decision too much. Enquire about whether others recognise your potential supervisor as a solid choice. Do her students finish their degrees, and in a reasonable time? Does she publish work of high quality in prominent outlets? Does she have a record of getting her students published? Does she equitably co-author articles with her students? Is the supervisor too overwhelmed with other commitments to give you the attention you need? Has she secured research grants? What kinds of jobs did her previous students obtain? Is the supervisor immersed in her academic community?

Also consider the personality of a potential supervisor. Do colleagues find her easy to work with? You should consult widely.

The availability of an appropriate supervisor should definitely affect your decision about which PhD programme to attend. But if the person you have your sights set on is known as a good supervisor, there are likely to be other students seeking to work with her. If you are going to a university mainly to work with that person, make sure that she will actually work with you.

4. Expect people to hold your hand

As a postgraduate, you need to take charge of your own programme. While you should seek guidance from your supervisor and from the graduate chair or her assistant, you are the person who ultimately organises your degree. Nobody – and certainly not your supervisor – will pull you aside to remind you, for example, that you must take a certain course or complete a form by a specific date.

You are also personally responsible for developing your own intellectual path. Do not expect your supervisor, or anyone else, to hold your hand and tell you which books to read, journals to subscribe to, future research projects to pursue, research collaborations to explore, conferences to attend or grants to apply for.

Seek guidance about your degree programme and your scholarly development, but do not wait around expecting others to tell you what to do next.

5. Concentrate only on your thesis

It is easy to assume that at graduate school you will spend most of your time and energy on a thesis. This focus on completing your thesis (in reasonable time) can foster the mistaken belief that nothing else in graduate school matters. Such an attitude, paradoxically, can be a way to screw up.

While doing PhD study, you learn to become a researcher and an academic. Those roles involve considerably more than simply carrying out a large research project. Professors also teach, edit journals, attend conferences, review manuscripts, mentor students, organise workshops and administer different aspects of their department and university, among many other things. Graduate school slowly exposes you to the nuances of these tasks.

While your overriding priorities are to publish, to make progress on your thesis and otherwise to build up your CV, you typically still have enough hours in your day to get involved in other projects. Not doing so means that you are missing opportunities to become a well-rounded academic. And greater exposure to different activities helps you to distinguish yourself in the job market.

6. Expect friends and family to understand

I was over the moon when I won my doctoral scholarship. Eager to share the good news, I phoned my parents. My mum listened closely to the details and said: “That’s not enough money to live off of. Can you get two?” Deflated, I had to tell her no, that was not possible.

Her reaction was not atypical: most people outside your academic colleagues will have a hard time relating to your experiences.

To an outsider, a PhD student’s schedule looks tantalisingly open. It can contain huge slots where you appear to be doing nothing. Those people might encourage you to socialise more or to take on more household tasks to fill the time. Maintaining self-discipline is hard enough at the best of times without outside encouragement to postpone or forgo your scholarly labours. You will likely have to tell friends and family that although you might not have a formal workday, you are “on the clock” and have to use your time to complete a long list of tasks.

But be sure to cultivate a group of sympathetic academic friends and colleagues with whom you can share and discuss your exploits.

7. Cover everything

Students eager to screw up should remember that their thesis is their defining personal and professional achievement. The thesis is everything. Therefore, it should contain everything. Approach your topic from every conceivable angle. Use a diverse set of methodologies. Explore the topic from every theoretical framework conceivable. Aim to produce an analysis that spans the full sweep of human history. This will ensure that in 30 years you will be asking whether you are eligible for pension benefits as a graduate student.

While working on my master’s degree, I bumped into one of my professors and summarised my thesis topic for him. I was doing research on the sex trade, so I detailed how I expected to conduct a feminist analysis of prostitution in Toronto. It would address economic issues and incorporate recent theoretical work on ethnicity and identity. My methodology involved an ambitious plan for a lengthy period of first-hand observation in the field, combined with dozens of interviews with female street prostitutes, police officers, politicians and local activists. When I stopped talking, he smiled wryly and said, “Well, you certainly have your work cut out for you.”

As we parted, I thought to myself: “He’s right. This is insane. I will never be able to do all of this.” The project was massive, unfocused, and had to be radically reduced in scope and ambition or I would never finish. I slept horribly that night, but my fear motivated me to transform my thesis into something more feasible. Master’s and PhD students tend to set overly ambitious parameters for their research, mistakenly thinking that their thesis has to be a monumental contribution to knowledge.

The jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie famously said that it took his whole life to learn what not to play. The same is true for designing and writing academic works. You need to identify what not to cover in your research, and you must remove tangents peripheral to your analysis or argument. You might have to cut major sections or even chapters. This will hurt. I cut many pages of material in the final stages of writing my master’s thesis, including a number of chunks that I loved but which did not quite fit with my final structure and arguments. A thesis, like any written work, is always stronger when you omit unnecessary sections. Simply place those parts in a separate file and work them up later for a submission to a journal.

8. Abuse your audience

“Everywhere I go I’m asked if I think the universities stifle writers. My opinion is that they don’t stifle enough of them.” – Flannery O’Connor

You are a budding academic, so you need to write like an academic. This means that you need to produce long, convoluted sentences written in the passive voice, riddled with discipline-specific jargon and exotic words. Writing like that will certainly demonstrate your academic pedigree, yes? Actually, it will not. It will alienate your audience, turn off editors and annoy your supervisor. When postgraduate students aim to “write like an academic”, it too often translates into producing turgid, tortured prose.

One secret of graduate school is that strong writers can do extremely well even if they are not the brightest people in the room. If you cannot write clearly and persuasively, everything about PhD study becomes harder.

So vow that you will not write like a traditional academic: eliminate jargon, strive for clear and concise assertions, compose in the active voice, and be kind to your readers. Above all, continually strive to improve your writing. Writing is like playing guitar; it can improve only through consistent, concerted effort.

9. Have a thin skin

My student Tom was in a funk. After I asked him several times what was wrong, he confided that he was upset by the reviews that he had received of an article that he had submitted to a journal for publication consideration. The reviews were harsh, the paper was rejected, and Tom doubted whether he was cut out to be an academic.

He then handed me a copy of the response that he had written to the journal’s editor. Thank goodness he had not yet sent it off. Tom’s reply came across as both hurt and angry. He essentially accused the reviewers of being know-nothings who were not up on the recent literature and had missed the point of his paper. He then questioned the editor’s competence for choosing such inept reviewers. After reading his letter, I explained to Tom why he needed to develop a thick skin about his professional work. Then I shredded his response to the editor.

You are likely a high achiever who has accumulated a lifetime’s worth of academic success. You are accustomed to being among the best students and to being praised. The feedback you have received from high school and university teachers may have tended to emphasise the positive, sometimes to the point of sugar-coating. Things are different in the more elevated levels of academia. Standards are higher, and failure is common.

You will be competing with other high-calibre students for scholarships and fellowships, the majority of which you will not win. You will also need to publish. A great deal of work will go into developing articles only to have many of them rejected. Once you enter the job market, you will put together lengthy job applications to apply for positions for which there may be dozens of applicants.

A key part of being an academic involves learning to persevere in the face of uncertainty, failure and rejection. Everyone is in the same boat.

10. Get romantically involved with faculty

Although it is rarely discussed frankly, postgraduates and academics sometimes become romantically involved. Here I am not talking about harassment or sexual assault, but rather about consensual couplings. As these are adults, one might be tempted to see this situation as something the participants should work out for themselves. Be that as it may, these consenting adults should be attuned to the dangers of faculty-graduate student relationships.

The most fundamental problem inherent in all such relationships is that academics have more formal and informal power than students. Even in seemingly consensual situations, questions arise about how free the student was to decline the relationship. This differential power is acute if it involves a supervisor sleeping with a student.

What might look like a caring relationship could, in fact, be part of a pattern in which a faculty member cycles through impressionable students.

If a romantic relationship continues, the student’s relationships with all sorts of department members may change. Her accomplishments might become tainted or be dismissed. People may suggest that she published an important article or secured a lucrative grant because her relationship gave her an unfair advantage. If the relationship ends badly, she can become a target of gossip and informal recriminations, sometimes for years to come.

Without condoning such situations, I should point out that I know of several instances where a fling between a student and an academic ended amicably, and in some cases evolved into a long-term relationship. But more often, students end up feeling betrayed, exploited and abandoned. These are risky situations, and unfortunately the graduate student bears almost all the risk. So find your emotional connections outside the faculty ranks.

Graduate school can be an enjoyable experience that sets you on the path for a rewarding career. These 10 tips will be invaluable if you are determined to screw up that prospect. Hopefully, our advice will also help those students eager to avoid missteps.

The authors have chosen to write in the first person singular to protect the privacy of the individuals whose experiences are discussed.

Kevin D. Haggerty is a Killam research laureate and professor of sociology and criminology at the University of Alberta . Aaron Doyle is associate professor in the department of sociology and anthropology at Carleton University .

This article is based on extracts from 57 Ways to Screw up in Grad School: Perverse Professional Lessons for Graduate Students (University of Chicago Press), a book that sets out further ways to screw up, moving from the earliest stages of planning to go to graduate school all the way through to the finish line. 57 Ways is published this week in the US and on 14 September 2015 in the UK.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login

Related articles

Essential PhD tips: 10 articles all doctoral students should read

PhD advice: from choosing the right topic to getting through your thesis

Reader's comments (12)

You might also like.

NIH raises postdoctoral salaries, but below target

Top US funding agency manages record increase in key programme for younger scientists, and sees gains in overall equity, while absorbing net cut in its annual budget

How to win the citation game without becoming a cynic

Boosting your publication metrics need not come at the expense of your integrity if you bear in mind these 10 tips, says Adrian Furnham

Black vice-chancellor eyes new generation of minority researchers

David Mba creates fully funded PhD studentships after taking reins at Birmingham City University

Featured jobs

10 easy ways to fail a Ph.D.

The attrition rate in Ph.D. school is high.

Anywhere from a third to half will fail.

In fact, there's a disturbing consistency to grad school failure.

I'm supervising a lot of new grad students this semester, so for their sake, I'm cataloging the common reasons for failure.

Read on for the top ten reasons students fail out of Ph.D. school.

Focus on grades or coursework

No one cares about grades in grad school.

There's a simple formula for the optimal GPA in grad school:

Anything higher implies time that could have been spent on research was wasted on classes. Advisors might even raise an eyebrow at a 4.0

During the first two years, students need to find an advisor, pick a research area, read a lot of papers and try small, exploratory research projects. Spending too much time on coursework distracts from these objectives.

Learn too much

Some students go to Ph.D. school because they want to learn.

Let there be no mistake: Ph.D. school involves a lot of learning.

But, it requires focused learning directed toward an eventual thesis.

Taking (or sitting in on) non-required classes outside one's focus is almost always a waste of time, and it's always unnecessary.

By the end of the third year, a typical Ph.D. student needs to have read about 50 to 150 papers to defend the novelty of a proposed thesis.

Of course, some students go too far with the related work search, reading so much about their intended area of research that they never start that research.

Advisors will lose patience with "eternal" students that aren't focused on the goal--making a small but significant contribution to human knowledge.

In the interest of personal disclosure, I suffered from the "want to learn everything" bug when I got to Ph.D. school.

I took classes all over campus for my first two years: Arabic, linguistics, economics, physics, math and even philosophy. In computer science, I took lots of classes in areas that had nothing to do with my research.

The price of all this "enlightenment" was an extra year on my Ph.D.

I only got away with this detour because while I was doing all that, I was a TA, which meant I wasn't wasting my advisor's grant funding.

Expect perfection

Perfectionism is a tragic affliction in academia, since it tends to hit the brightest the hardest.

Perfection cannot be attained. It is approached in the limit.

Students that polish a research paper well past the point of diminishing returns, expecting to hit perfection, will never stop polishing.

Students that can't begin to write until they have the perfect structure of the paper mapped out will never get started.

For students with problems starting on a paper or dissertation, my advice is that writing a paper should be an iterative process: start with an outline and some rough notes; take a pass over the paper and improve it a little; rinse; repeat. When the paper changes little with each pass, it's at diminishing returns. One or two more passes over the paper are all it needs at that point.

"Good enough" is better than "perfect."

Procrastinate

Chronic perfectionists also tend to be procrastinators.

So do eternal students with a drive to learn instead of research.

Ph.D. school seems to be a magnet for every kind of procrastinator.

Unfortunately, it is also a sieve that weeds out the unproductive.

Procrastinators should check out my tips for boosting productivity .

Go rogue too soon/too late

The advisor-advisee dynamic needs to shift over the course of a degree.

Early on, the advisor should be hands on, doling out specific topics and helping to craft early papers.

Toward the end, the student should know more than the advisor about her topic. Once the inversion happens, she needs to "go rogue" and start choosing the topics to investigate and initiating the paper write-ups. She needs to do so even if her advisor is insisting she do something else.

The trick is getting the timing right.

Going rogue before the student knows how to choose good topics and write well will end in wasted paper submissions and a grumpy advisor.

On the other hand, continuing to act only when ordered to act past a certain point will strain an advisor that expects to start seeing a "return" on an investment of time and hard-won grant money.

Advisors expect near-terminal Ph.D. students to be proto-professors with intimate knowledge of the challenges in their field. They should be capable of selecting and attacking research problems of appropriate size and scope.

Treat Ph.D. school like school or work

Ph.D. school is neither school nor work.

Ph.D. school is a monastic experience. And, a jealous hobby.

Solving problems and writing up papers well enough to pass peer review demands contemplative labor on days, nights and weekends.

Reading through all of the related work takes biblical levels of devotion.

Ph.D. school even comes with built-in vows of poverty and obedience.

The end brings an ecclesiastical robe and a clerical hood.

Students that treat Ph.D. school like a 9-5 endeavor are the ones that take 7+ years to finish, or end up ABD.

Ignore the committee

Some Ph.D. students forget that a committee has to sign off on their Ph.D.

It's important for students to maintain contact with committee members in the latter years of a Ph.D. They need to know what a student is doing.

It's also easy to forget advice from a committee member since they're not an everyday presence like an advisor.

Committee members, however, rarely forget the advice they give.

It doesn't usually happen, but I've seen a shouting match between a committee member and a defender where they disagreed over the metrics used for evaluation of an experiment. This committee member warned the student at his proposal about his choice of metrics.

He ignored that warning.

He was lucky: it added only one more semester to his Ph.D.

Another student I knew in grad school was told not to defend, based on the draft of his dissertation. He overruled his committee's advice, and failed his defense. He was told to scrap his entire dissertaton and start over. It took him over ten years to finish his Ph.D.

Aim too low

Some students look at the weakest student to get a Ph.D. in their department and aim for that.

This attitude guarantees that no professorship will be waiting for them.

And, it all but promises failure.

The weakest Ph.D. to escape was probably repeatedly unlucky with research topics, and had to settle for a contingency plan.

Aiming low leaves no room for uncertainty.

And, research is always uncertain.

Aim too high

A Ph.D. seems like a major undertaking from the perspective of the student.

But, it is not the final undertaking. It's the start of a scientific career.

A Ph.D. does not have to cure cancer or enable cold fusion.

At best a handful of chemists remember what Einstein's Ph.D. was in.

Einstein's Ph.D. dissertation was a principled calculation meant to estimate Avogadro's number. He got it wrong. By a factor of 3.

He still got a Ph.D.

A Ph.D. is a small but significant contribution to human knowledge.

Impact is something students should aim for over a lifetime of research.

Making a big impact with a Ph.D. is about as likely as hitting a bullseye the very first time you've fired a gun.

Once you know how to shoot, you can keep shooting until you hit it.

Plus, with a Ph.D., you get a lifetime supply of ammo.

Some advisors can give you a list of potential research topics. If they can, pick the topic that's easiest to do but which still retains your interest.

It does not matter at all what you get your Ph.D. in.

All that matters is that you get one.

It's the training that counts--not the topic.

Miss the real milestones

Most schools require coursework, qualifiers, thesis proposal, thesis defense and dissertation. These are the requirements on paper.

In practice, the real milestones are three good publications connected by a (perhaps loosely) unified theme.

Coursework and qualifiers are meant to undo admissions mistakes. A student that has published by the time she takes her qualifiers is not a mistake.

Once a student has two good publications, if she convinces her committee that she can extrapolate a third, she has a thesis proposal.

Once a student has three publications, she has defended, with reasonable confidence, that she can repeatedly conduct research of sufficient quality to meet the standards of peer review. If she draws a unifying theme, she has a thesis, and if she staples her publications together, she has a dissertation.

I fantasize about buying an industrial-grade stapler capable of punching through three journal papers and calling it The Dissertator .

Of course, three publications is nowhere near enough to get a professorship--even at a crappy school. But, it's about enough to get a Ph.D.

Related posts

- Recommended reading for grad students .

- The illustrated guide to a Ph.D.

- How to get into grad school .

- Advice for thesis proposals .

- Productivity tips for academics .

- Academic job hunt advice .

- Successful Ph.D. students: Perseverance, tenacity and cogency .

- The CRAPL: An open source license for academics .

- PhD Failure Rate – A Study of 26,076 PhD Candidates

- Doing a PhD

The PhD failure rate in the UK is 19.5%, with 16.2% of students leaving their PhD programme early, and 3.3% of students failing their viva. 80.5% of all students who enrol onto a PhD programme successfully complete it and are awarded a doctorate.

Introduction

One of the biggest concerns for doctoral students is the ongoing fear of failing their PhD.

After all those years of research, the long days in the lab and the endless nights in the library, it’s no surprise to find many agonising over the possibility of it all being for nothing. While this fear will always exist, it would help you to know how likely failure is, and what you can do to increase your chances of success.

Read on to learn how PhDs can be failed, what the true failure rates are based on an analysis of 26,067 PhD candidates from 14 UK universities, and what your options are if you’re unsuccessful in obtaining your PhD.

Ways You Can Fail A PhD

There are essentially two ways in which you can fail a PhD; non-completion or failing your viva (also known as your thesis defence ).

Non-completion

Non-completion is when a student leaves their PhD programme before having sat their viva examination. Since vivas take place at the end of the PhD journey, typically between the 3rd and 4th year for most full-time programmes, most failed PhDs fall within the ‘non-completion’ category because of the long duration it covers.

There are many reasons why a student may decide to leave a programme early, though these can usually be grouped into two categories:

- Motives – The individual may no longer believe undertaking a PhD is for them. This might be because it isn’t what they had imagined, or they’ve decided on an alternative path.

- Extenuating circumstances – The student may face unforeseen problems beyond their control, such as poor health, bereavement or family difficulties, preventing them from completing their research.

In both cases, a good supervisor will always try their best to help the student continue with their studies. In the former case, this may mean considering alternative research questions or, in the latter case, encouraging you to seek academic support from the university through one of their student care policies.

Besides the student deciding to end their programme early, the university can also make this decision. On these occasions, the student’s supervisor may not believe they’ve made enough progress for the time they’ve been on the project. If the problem can’t be corrected, the supervisor may ask the university to remove the student from the programme.

Failing The Viva

Assuming you make it to the end of your programme, there are still two ways you can be unsuccessful.

The first is an unsatisfactory thesis. For whatever reason, your thesis may be deemed not good enough, lacking originality, reliable data, conclusive findings, or be of poor overall quality. In such cases, your examiners may request an extensive rework of your thesis before agreeing to perform your viva examination. Although this will rarely be the case, it is possible that you may exceed the permissible length of programme registration and if you don’t have valid grounds for an extension, you may not have enough time to be able to sit your viva.

The more common scenario, while still being uncommon itself, is that you sit and fail your viva examination. The examiners may decide that your research project is severely flawed, to the point where it can’t possibly be remedied even with major revisions. This could happen for reasons such as basing your study on an incorrect fundamental assumption; this should not happen however if there is a proper supervisory support system in place.

PhD Failure Rate – UK & EU Statistics

According to 2010-11 data published by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (now replaced by UK Research and Innovation ), 72.9% of students enrolled in a PhD programme in the UK or EU complete their degree within seven years. Following this, 80.5% of PhD students complete their degree within 25 years.

This means that four out of every five students who register onto a PhD programme successfully complete their doctorate.

While a failure rate of one in five students may seem a little high, most of these are those who exit their programme early as opposed to those who fail at the viva stage.

Failing Doesn’t Happen Often

Although a PhD is an independent project, you will be appointed a supervisor to support you. Each university will have its own system for how your supervisor is to support you , but regardless of this, they will all require regular communication between the two of you. This could be in the form of annual reviews, quarterly interim reviews or regular meetings. The majority of students also have a secondary academic supervisor (and in some cases a thesis committee of supervisors); the role of these can vary from having a hands-on role in regular supervision, to being another useful person to bounce ideas off of.

These frequent check-ins are designed to help you stay on track with your project. For example, if any issues are identified, you and your supervisor can discuss how to rectify them in order to refocus your research. This reduces the likelihood of a problem going undetected for several years, only for it to be unearthed after it’s too late to address.

In addition, the thesis you submit to your examiners will likely be your third or fourth iteration, with your supervisor having critiqued each earlier version. As a result, your thesis will typically only be submitted to the examiners after your supervisor approves it; many UK universities require a formal, signed document to be submitted by the primary academic supervisor at the same time as the student submits the thesis, confirming that he or she has approved the submission.

Failed Viva – Outcomes of 26,076 Students

Despite what you may have heard, the failing PhD rate amongst students who sit their viva is low.

This, combined with ongoing guidance from your supervisor, is because vivas don’t have a strict pass/fail outcome. You can find a detailed breakdown of all viva outcomes in our viva guide, but to summarise – the most common outcome will be for you to revise your thesis in accordance with the comments from your examiners and resubmit it.

This means that as long as the review of your thesis and your viva examination uncovers no significant issues, you’re almost certain to be awarded a provisional pass on the basis you make the necessary corrections to your thesis.

To give you an indication of the viva failure rate, we’ve analysed the outcomes of 26,076 PhD candidates from 14 UK universities who sat a viva between 2006 and 2017.

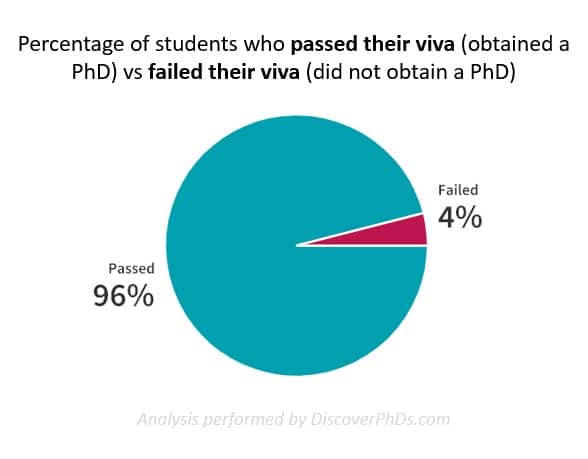

The analysis shows that of the 26,076 students who sat their viva, 25,063 succeeded; this is just over 96% of the total students as shown in the chart below.

Students Who Passed

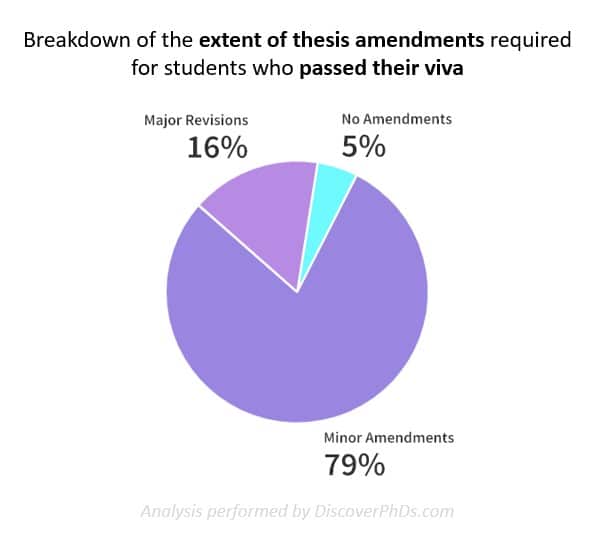

The analysis shows that of the 96% of students who passed, approximately 5% required no amendments, 79% required minor amendments and the remaining 16% required major revisions. This supports our earlier discussion on how the most common outcome of a viva is a ‘pass with minor amendments’.

Students Who Failed

Of the 4% of unsuccessful students, approximately 97% were awarded an MPhil (Master of Philosophy), and 3% weren’t awarded a degree.

Note : It should be noted that while the data provides the student’s overall outcome, i.e. whether they passed or failed, they didn’t all provide the students specific outcome, i.e. whether they had to make amendments, or with a failure, whether they were awarded an MPhil. Therefore, while the breakdowns represent the current known data, the exact breakdown may differ.

Summary of Findings

By using our data in combination with the earlier statistic provided by HEFCE, we can gain an overall picture of the PhD journey as summarised in the image below.

To summarise, based on the analysis of 26,076 PhD candidates at 14 universities between 2006 and 2017, the PhD pass rate in the UK is 80.5%. Of the 19.5% of students who fail, 3.3% is attributed to students failing their viva and the remaining 16.2% is attributed to students leaving their programme early.

The above statistics indicate that while 1 in every 5 students fail their PhD, the failure rate for the viva process itself is low. Specifically, only 4% of all students who sit their viva fail; in other words, 96% of the students pass it.

What Are Your Options After an Unsuccessful PhD?

Appeal your outcome.

If you believe you had a valid case, you can try to appeal against your outcome . The appeal process will be different for each university, so ensure you consult the guidelines published by your university before taking any action.

While making an appeal may be an option, it should only be considered if you genuinely believe you have a legitimate case. Most examiners have a lot of experience in assessing PhD candidates and follow strict guidelines when making their decisions. Therefore, your claim for appeal will need to be strong if it is to stand up in front of committee members in the adjudication process.

Downgrade to MPhil

If you are unsuccessful in being awarded a PhD, an MPhil may be awarded instead. For this to happen, your work would need to be considered worthy of an MPhil, as although it is a Master’s degree, it is still an advanced postgraduate research degree.

Unfortunately, there’s a lot of stigma around MPhil degrees, with many worrying that it will be seen as a sign of a failed PhD. While not as advanced as a PhD, an MPhil is still an advanced research degree, and being awarded one shows that you’ve successfully carried out an independent research project which is an undertaking to be admired.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Additional Resources

Hopefully now knowing the overall picture your mind will feel slightly more at ease. Regardless, there are several good practices you can adopt to ensure you’re always in the best possible position. The key of these includes developing a good working relationship with your supervisor, working to a project schedule, having your thesis checked by several other academics aside from your supervisor, and thoroughly preparing for your viva examination.

We’ve developed a number of resources which should help you in the above:

- What to Expect from Your Supervisor – Find out what to look for in a Supervisor, how they will typically support you, and how often you should meet with them.

- How to Write a Research Proposal – Find an outline of how you can go about putting a project plan together.

- What is a PhD Viva? – Learn exactly what a viva is, their purpose and what you can expect on the day. We’ve also provided a full breakdown of all the possible outcomes of a viva and tips to help you prepare for your own.

Data for Statistics

- Cardiff University – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- Imperial College London – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- London School of Economics (LSE) – 2006/07 to 2015/16

- Queen Mary University of London – 2009/10 to 2015/16

- University College London (UCL) – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Aberdeen – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Birmingham – 2006/07 to 2015/16

- University of Bristol – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Edinburgh – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Nottingham – 2006/07 to 2015/16

- University of Oxford – 2007/08 to 2016/17

- University of York – 2009/10 to 2016/17

- University of Manchester – 2008/09 to 2017/18

- University of Sheffield – 2006/07 to 2016/17

Note : The data used for this analysis was obtained from the above universities under the Freedom of Information Act. As per the Act, the information was provided in such a way that no specific individual can be identified from the data.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

Will Failing a Class Impact My Application?

What’s covered:, will a failing grade impact my application, factors that impact how colleges perceive your failing grade, how much will failing a class impact you.

- How to Compensate for Failing a Class

It’s many students’ worst nightmare: failing a class. Whether due to external stressors, challenging course material, or any number of other factors, failing a class is never a good thing. After all, when it comes time to apply to colleges, admissions committees place a good deal of importance on your transcript and academic abilities. Especially when you are competing against students with near perfect academic records, seeing that failing grade on your transcript may feel like the end of the world. But is it?

The short answer is yes, a failing grade will have a negative impact on your application. After all, colleges are academic institutions that want to admit students who will succeed in a rigorous and demanding intellectual environment. If you have performed poorly in a high school class, admissions officers may be skeptical of your ability to thrive at their school.

That being said, a failing grade doesn’t have to be the end of the world. There are a lot of factors that can influence how colleges look at your failed class, and some ways to shed a more positive light on it. While it’s less than ideal, it doesn’t define your entire application, and if you frame it right, it shouldn’t have to ruin your chances at your dream school.

The Class You Failed

One consideration that affects the impact a failed class has on your application is the course you failed, and how important it is to your academic history. Failing a math course as an aspiring engineer has far graver implications than failing a journalism course as a potential doctor. If the class you failed is in a subject that is not directly related to your intended major or career path, it probably will have less of an impact.

On the flip side, failing a class that is extremely important to what you plan on studying has far more of an impact on your overall application. This would seriously call into question your ability to thrive in your future course of study, and cast doubt on your specific strengths as a student and applicant.

Additionally, failing a core class (English/language arts, math, science, history/social studies, and foreign language) is far more significant than failing an elective, or other less central course. In all likelihood, many of the universities that you will be applying to have some type of general education requirements that significantly draw from the material of the four core academic fields.

Not only is doing well in these courses imperative to demonstrating your all around academic prowess, but it is also imperative to demonstrating your ability to succeed in the future. What’s more, even non-gen ed courses significantly rely upon the skills and expertise you cultivate in these core subjects. For instance, even if you fail mathematics and intend to concentrate in an entirely unrelated field, like Comparative Literature, it’s possible that your struggles in math may be interpreted by admissions officers as underdeveloped problem solving and/or analytical abilities—skills that are central to many different academic fields.

However, elective courses tend to be less indicative of deeper academic concerns, and thus the grades you make in these courses are less important when evaluating your overall application. While not ideal, a poor performance in a visual arts or physical education course is far less likely to exclude a future lawyer’s or data scientist’s application from serious consideration.

To summarize: the less related a class is to both your core academic abilities and future intellectual and employment goals, the less of an impact it will have on your application.

When You Failed the Class

Another consideration admissions officers will keep in mind when weighing a failing grade the year or semester that you failed this class. Overall, freshman and sophomore year grades are weighed less heavily than grades in junior and senior year. There are various reasons for this. For one thing, colleges know that there is an adjustment period when it comes to high school. For many students, the transition from middle to high school can be a challenging and difficult time. The increase in course rigor can be debilitating for some, and colleges are cognizant of this. Thus, they allow for a certain degree leniency when it comes to evaluating early grades.

Additionally, academic abilities, motivations, and goals are steadily developing and evolving as one progresses through high school. Just because a student was undermotivated freshman year does not mean that they do not have a great mind, and it certainly does not mean that they cannot turn that lack of motivation around.

So, if your failed grade is from the beginning of high school, it won’t be counted against you as harshly. However, if you fail a class later on in high school it will not only receive more scrutiny, but it will also raise more questions.

Overall Grade Trends

If you are the kind of applicant who really turned things around during their high school career, colleges want to be able to see that—and see it clearly. If you started off with a less than ideal transcript, it is important to show significant growth and improvement during the course of your high school career.

Upward grade trends can be extremely compelling. A student who started off with mediocre grades, or even a failing grade, during their freshman year but then applied themselves and started earning consistent A’s in upper level courses during their later years shows great dedication and a commitment to improvement. Both of these qualities are attractive to admissions officers, and make the student a more competitive applicant for their school.

On the other hand, a downward grade trajectory can be concerning. If you started off with fantastic grades early on, but consistently dropped off towards the end of your high school career, admissions officers are unlikely to be as forgiving. For one thing, a downward trend may communicate loss of motivation and a decrease in your dedication to academics.

Additionally, the grades you earn later on in high school are far more reflective of the grades you will earn in college. Thus, admissions officers may interpret bad academic performances in your junior and senior year as indicative of future bad academic performance once you start at your university, which school’s won’t want to take a chance on.

Overall Context Within Your Application

Of course, like many other factors, a failing or poor grade will be taken within the context of your overall application. If you are, on the whole, a great, high performing student who had one single slip up in a very difficult class, colleges are much more likely to be understanding, so long as the rest of your high school transcript reflects academic excellence. Colleges recognize that applicants are human and perfection isn’t possible. Keep in mind, however, that the more competitive a school is the less room you have for these kinds of mistakes.

On the other side of things, sometimes the overall context of your application may increase the significance of a failing grade. If you fail a class multiple times, fail a class later on in your high school career, or, as we previously discussed, have a downward grade trend, this signals a lack of motivation and application on your part, which will give admissions officers significant cause for concern.

If colleges have any reason to believe that your poor academic performance is not an outlier but rather a consistent trend, you can assume that this will significantly hurt your application.

Extenuating Circumstances

Finally, your personal circumstances can also impact how a failing grade is interpreted. If you have extenuating circumstances that have significantly impacted your ability to perform in the classroom, it’s important to let colleges know. Sometimes, through no fault of their own, students face challenges that impact their transcript, and that is okay. However, it is imperative to ensure that colleges are able to evaluate that transcript with full knowledge of the circumstances that have impacted it.

Ensure you are open and honest about the circumstances surrounding a less than ideal academic performance, so that colleges are aware of the scope and magnitude of these circumstances. Whether you address this via a counselor recommendation, a personal essay, or in the ‘Additional Information’ section of your application, it is important that you communicate what exactly led to a grade that you feel isn’t reflective of your intellectual capacity and/or your ability to succeed in college.

No two applicants are exactly the same, and you may be wondering how much failing a class is going to impact you personally. A lot of variables go into answering this question, from when you failed the class, to what the class was, and of course, what the rest of your application looks like. CollegeVine’s free chancing engine can help answer that question for you, as it factors in not only your grades, but also extracurriculars, test scores if you have them, and other elements of your profile to determine your chances of admission at over 1500 schools.

How To Compensate For Having Failed a Class

The best way to compensate for having failed a class is by putting your failing grade in context, and by making the rest of your application as strong as possible. So, what is the best way to do that?

First, if there’s any important context that might help explain why you failed, it’s important to include that in your application—that’s exactly what the Additional Information section is for. Remember not to make excuses, or invent a reason that isn’t true or didn’t contribute significantly to your failing grade. Be straightforward and honest if you have important extenuating circumstances, and focus on improving your application in other ways if you don’t.

You can compensate for a slightly weaker transcript with strong test scores. Even if the schools you are considering are test optional, focus on getting the best standardized test scores possible, to offset the negative impact of failing a class. This can be particularly effective if the class you failed is directly or indirectly part of a standardized test, as this can show that you have mastered the material since failing.

Emphasizing your other strengths in your application also helps colleges view your application holistically and see you as a strong candidate, even if your academic history isn’t perfect. A rich, detailed extracurricular profile and well-written essays can go a long way to minimizing the impact of a failed class. If you’re looking to make sure your essays are as strong as possible, you can check out our free Peer Essay Review tool , where you can get a free review of your essay from another student. College admissions experts at CollegeVine can also help you present yourself in the best possible light. Find the right advisor for you to improve your chances of getting into your dream school!

Finally, a good letter of recommendation that speaks to positive aspects of your character and your perseverance after failing can help. Talk to your recommenders about the qualities you hope they will be able to emphasize in your letters, and if you can, provide them with examples that they may have forgotten or a resume of your accomplishments outside of their class. Depending on your relationship with the teacher whose class you failed, you could consider asking them to write one of your letters to touch upon your growth since that experience.

Failing a class can be a scary experience and it might have you feeling like your hopes of college admissions are over, but rest assured, you can make up for early setbacks and still situate yourself to be a competitive candidate at your dream schools.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts