How To Write A Dissertation Or Thesis

8 straightforward steps to craft an a-grade dissertation.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

Writing a dissertation or thesis is not a simple task. It takes time, energy and a lot of will power to get you across the finish line. It’s not easy – but it doesn’t necessarily need to be a painful process. If you understand the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis, your research journey will be a lot smoother.

In this post, I’m going to outline the big-picture process of how to write a high-quality dissertation or thesis, without losing your mind along the way. If you’re just starting your research, this post is perfect for you. Alternatively, if you’ve already submitted your proposal, this article which covers how to structure a dissertation might be more helpful.

How To Write A Dissertation: 8 Steps

- Clearly understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is

- Find a unique and valuable research topic

- Craft a convincing research proposal

- Write up a strong introduction chapter

- Review the existing literature and compile a literature review

- Design a rigorous research strategy and undertake your own research

- Present the findings of your research

- Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Step 1: Understand exactly what a dissertation is

This probably sounds like a no-brainer, but all too often, students come to us for help with their research and the underlying issue is that they don’t fully understand what a dissertation (or thesis) actually is.

So, what is a dissertation?

At its simplest, a dissertation or thesis is a formal piece of research , reflecting the standard research process . But what is the standard research process, you ask? The research process involves 4 key steps:

- Ask a very specific, well-articulated question (s) (your research topic)

- See what other researchers have said about it (if they’ve already answered it)

- If they haven’t answered it adequately, undertake your own data collection and analysis in a scientifically rigorous fashion

- Answer your original question(s), based on your analysis findings

In short, the research process is simply about asking and answering questions in a systematic fashion . This probably sounds pretty obvious, but people often think they’ve done “research”, when in fact what they have done is:

- Started with a vague, poorly articulated question

- Not taken the time to see what research has already been done regarding the question

- Collected data and opinions that support their gut and undertaken a flimsy analysis

- Drawn a shaky conclusion, based on that analysis

If you want to see the perfect example of this in action, look out for the next Facebook post where someone claims they’ve done “research”… All too often, people consider reading a few blog posts to constitute research. Its no surprise then that what they end up with is an opinion piece, not research. Okay, okay – I’ll climb off my soapbox now.

The key takeaway here is that a dissertation (or thesis) is a formal piece of research, reflecting the research process. It’s not an opinion piece , nor a place to push your agenda or try to convince someone of your position. Writing a good dissertation involves asking a question and taking a systematic, rigorous approach to answering it.

If you understand this and are comfortable leaving your opinions or preconceived ideas at the door, you’re already off to a good start!

Step 2: Find a unique, valuable research topic

As we saw, the first step of the research process is to ask a specific, well-articulated question. In other words, you need to find a research topic that asks a specific question or set of questions (these are called research questions ). Sounds easy enough, right? All you’ve got to do is identify a question or two and you’ve got a winning research topic. Well, not quite…

A good dissertation or thesis topic has a few important attributes. Specifically, a solid research topic should be:

Let’s take a closer look at these:

Attribute #1: Clear

Your research topic needs to be crystal clear about what you’re planning to research, what you want to know, and within what context. There shouldn’t be any ambiguity or vagueness about what you’ll research.

Here’s an example of a clearly articulated research topic:

An analysis of consumer-based factors influencing organisational trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms.

As you can see in the example, its crystal clear what will be analysed (factors impacting organisational trust), amongst who (consumers) and in what context (British low-cost equity brokerage firms, based online).

Need a helping hand?

Attribute #2: Unique

Your research should be asking a question(s) that hasn’t been asked before, or that hasn’t been asked in a specific context (for example, in a specific country or industry).

For example, sticking organisational trust topic above, it’s quite likely that organisational trust factors in the UK have been investigated before, but the context (online low-cost equity brokerages) could make this research unique. Therefore, the context makes this research original.

One caveat when using context as the basis for originality – you need to have a good reason to suspect that your findings in this context might be different from the existing research – otherwise, there’s no reason to warrant researching it.

Attribute #3: Important

Simply asking a unique or original question is not enough – the question needs to create value. In other words, successfully answering your research questions should provide some value to the field of research or the industry. You can’t research something just to satisfy your curiosity. It needs to make some form of contribution either to research or industry.

For example, researching the factors influencing consumer trust would create value by enabling businesses to tailor their operations and marketing to leverage factors that promote trust. In other words, it would have a clear benefit to industry.

So, how do you go about finding a unique and valuable research topic? We explain that in detail in this video post – How To Find A Research Topic . Yeah, we’ve got you covered 😊

Step 3: Write a convincing research proposal

Once you’ve pinned down a high-quality research topic, the next step is to convince your university to let you research it. No matter how awesome you think your topic is, it still needs to get the rubber stamp before you can move forward with your research. The research proposal is the tool you’ll use for this job.

So, what’s in a research proposal?

The main “job” of a research proposal is to convince your university, advisor or committee that your research topic is worthy of approval. But convince them of what? Well, this varies from university to university, but generally, they want to see that:

- You have a clearly articulated, unique and important topic (this might sound familiar…)

- You’ve done some initial reading of the existing literature relevant to your topic (i.e. a literature review)

- You have a provisional plan in terms of how you will collect data and analyse it (i.e. a methodology)

At the proposal stage, it’s (generally) not expected that you’ve extensively reviewed the existing literature , but you will need to show that you’ve done enough reading to identify a clear gap for original (unique) research. Similarly, they generally don’t expect that you have a rock-solid research methodology mapped out, but you should have an idea of whether you’ll be undertaking qualitative or quantitative analysis , and how you’ll collect your data (we’ll discuss this in more detail later).

Long story short – don’t stress about having every detail of your research meticulously thought out at the proposal stage – this will develop as you progress through your research. However, you do need to show that you’ve “done your homework” and that your research is worthy of approval .

So, how do you go about crafting a high-quality, convincing proposal? We cover that in detail in this video post – How To Write A Top-Class Research Proposal . We’ve also got a video walkthrough of two proposal examples here .

Step 4: Craft a strong introduction chapter

Once your proposal’s been approved, its time to get writing your actual dissertation or thesis! The good news is that if you put the time into crafting a high-quality proposal, you’ve already got a head start on your first three chapters – introduction, literature review and methodology – as you can use your proposal as the basis for these.

Handy sidenote – our free dissertation & thesis template is a great way to speed up your dissertation writing journey.

What’s the introduction chapter all about?

The purpose of the introduction chapter is to set the scene for your research (dare I say, to introduce it…) so that the reader understands what you’ll be researching and why it’s important. In other words, it covers the same ground as the research proposal in that it justifies your research topic.

What goes into the introduction chapter?

This can vary slightly between universities and degrees, but generally, the introduction chapter will include the following:

- A brief background to the study, explaining the overall area of research

- A problem statement , explaining what the problem is with the current state of research (in other words, where the knowledge gap exists)

- Your research questions – in other words, the specific questions your study will seek to answer (based on the knowledge gap)

- The significance of your study – in other words, why it’s important and how its findings will be useful in the world

As you can see, this all about explaining the “what” and the “why” of your research (as opposed to the “how”). So, your introduction chapter is basically the salesman of your study, “selling” your research to the first-time reader and (hopefully) getting them interested to read more.

How do I write the introduction chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this post .

Step 5: Undertake an in-depth literature review

As I mentioned earlier, you’ll need to do some initial review of the literature in Steps 2 and 3 to find your research gap and craft a convincing research proposal – but that’s just scratching the surface. Once you reach the literature review stage of your dissertation or thesis, you need to dig a lot deeper into the existing research and write up a comprehensive literature review chapter.

What’s the literature review all about?

There are two main stages in the literature review process:

Literature Review Step 1: Reading up

The first stage is for you to deep dive into the existing literature (journal articles, textbook chapters, industry reports, etc) to gain an in-depth understanding of the current state of research regarding your topic. While you don’t need to read every single article, you do need to ensure that you cover all literature that is related to your core research questions, and create a comprehensive catalogue of that literature , which you’ll use in the next step.

Reading and digesting all the relevant literature is a time consuming and intellectually demanding process. Many students underestimate just how much work goes into this step, so make sure that you allocate a good amount of time for this when planning out your research. Thankfully, there are ways to fast track the process – be sure to check out this article covering how to read journal articles quickly .

Literature Review Step 2: Writing up

Once you’ve worked through the literature and digested it all, you’ll need to write up your literature review chapter. Many students make the mistake of thinking that the literature review chapter is simply a summary of what other researchers have said. While this is partly true, a literature review is much more than just a summary. To pull off a good literature review chapter, you’ll need to achieve at least 3 things:

- You need to synthesise the existing research , not just summarise it. In other words, you need to show how different pieces of theory fit together, what’s agreed on by researchers, what’s not.

- You need to highlight a research gap that your research is going to fill. In other words, you’ve got to outline the problem so that your research topic can provide a solution.

- You need to use the existing research to inform your methodology and approach to your own research design. For example, you might use questions or Likert scales from previous studies in your your own survey design .

As you can see, a good literature review is more than just a summary of the published research. It’s the foundation on which your own research is built, so it deserves a lot of love and attention. Take the time to craft a comprehensive literature review with a suitable structure .

But, how do I actually write the literature review chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this video post .

Step 6: Carry out your own research

Once you’ve completed your literature review and have a sound understanding of the existing research, its time to develop your own research (finally!). You’ll design this research specifically so that you can find the answers to your unique research question.

There are two steps here – designing your research strategy and executing on it:

1 – Design your research strategy

The first step is to design your research strategy and craft a methodology chapter . I won’t get into the technicalities of the methodology chapter here, but in simple terms, this chapter is about explaining the “how” of your research. If you recall, the introduction and literature review chapters discussed the “what” and the “why”, so it makes sense that the next point to cover is the “how” –that’s what the methodology chapter is all about.

In this section, you’ll need to make firm decisions about your research design. This includes things like:

- Your research philosophy (e.g. positivism or interpretivism )

- Your overall methodology (e.g. qualitative , quantitative or mixed methods)

- Your data collection strategy (e.g. interviews , focus groups, surveys)

- Your data analysis strategy (e.g. content analysis , correlation analysis, regression)

If these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these in plain language in other posts. It’s not essential that you understand the intricacies of research design (yet!). The key takeaway here is that you’ll need to make decisions about how you’ll design your own research, and you’ll need to describe (and justify) your decisions in your methodology chapter.

2 – Execute: Collect and analyse your data

Once you’ve worked out your research design, you’ll put it into action and start collecting your data. This might mean undertaking interviews, hosting an online survey or any other data collection method. Data collection can take quite a bit of time (especially if you host in-person interviews), so be sure to factor sufficient time into your project plan for this. Oftentimes, things don’t go 100% to plan (for example, you don’t get as many survey responses as you hoped for), so bake a little extra time into your budget here.

Once you’ve collected your data, you’ll need to do some data preparation before you can sink your teeth into the analysis. For example:

- If you carry out interviews or focus groups, you’ll need to transcribe your audio data to text (i.e. a Word document).

- If you collect quantitative survey data, you’ll need to clean up your data and get it into the right format for whichever analysis software you use (for example, SPSS, R or STATA).

Once you’ve completed your data prep, you’ll undertake your analysis, using the techniques that you described in your methodology. Depending on what you find in your analysis, you might also do some additional forms of analysis that you hadn’t planned for. For example, you might see something in the data that raises new questions or that requires clarification with further analysis.

The type(s) of analysis that you’ll use depend entirely on the nature of your research and your research questions. For example:

- If your research if exploratory in nature, you’ll often use qualitative analysis techniques .

- If your research is confirmatory in nature, you’ll often use quantitative analysis techniques

- If your research involves a mix of both, you might use a mixed methods approach

Again, if these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these concepts and techniques in other posts. The key takeaway is simply that there’s no “one size fits all” for research design and methodology – it all depends on your topic, your research questions and your data. So, don’t be surprised if your study colleagues take a completely different approach to yours.

Step 7: Present your findings

Once you’ve completed your analysis, it’s time to present your findings (finally!). In a dissertation or thesis, you’ll typically present your findings in two chapters – the results chapter and the discussion chapter .

What’s the difference between the results chapter and the discussion chapter?

While these two chapters are similar, the results chapter generally just presents the processed data neatly and clearly without interpretation, while the discussion chapter explains the story the data are telling – in other words, it provides your interpretation of the results.

For example, if you were researching the factors that influence consumer trust, you might have used a quantitative approach to identify the relationship between potential factors (e.g. perceived integrity and competence of the organisation) and consumer trust. In this case:

- Your results chapter would just present the results of the statistical tests. For example, correlation results or differences between groups. In other words, the processed numbers.

- Your discussion chapter would explain what the numbers mean in relation to your research question(s). For example, Factor 1 has a weak relationship with consumer trust, while Factor 2 has a strong relationship.

Depending on the university and degree, these two chapters (results and discussion) are sometimes merged into one , so be sure to check with your institution what their preference is. Regardless of the chapter structure, this section is about presenting the findings of your research in a clear, easy to understand fashion.

Importantly, your discussion here needs to link back to your research questions (which you outlined in the introduction or literature review chapter). In other words, it needs to answer the key questions you asked (or at least attempt to answer them).

For example, if we look at the sample research topic:

In this case, the discussion section would clearly outline which factors seem to have a noteworthy influence on organisational trust. By doing so, they are answering the overarching question and fulfilling the purpose of the research .

For more information about the results chapter , check out this post for qualitative studies and this post for quantitative studies .

Step 8: The Final Step Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Last but not least, you’ll need to wrap up your research with the conclusion chapter . In this chapter, you’ll bring your research full circle by highlighting the key findings of your study and explaining what the implications of these findings are.

What exactly are key findings? The key findings are those findings which directly relate to your original research questions and overall research objectives (which you discussed in your introduction chapter). The implications, on the other hand, explain what your findings mean for industry, or for research in your area.

Sticking with the consumer trust topic example, the conclusion might look something like this:

Key findings

This study set out to identify which factors influence consumer-based trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms. The results suggest that the following factors have a large impact on consumer trust:

While the following factors have a very limited impact on consumer trust:

Notably, within the 25-30 age groups, Factors E had a noticeably larger impact, which may be explained by…

Implications

The findings having noteworthy implications for British low-cost online equity brokers. Specifically:

The large impact of Factors X and Y implies that brokers need to consider….

The limited impact of Factor E implies that brokers need to…

As you can see, the conclusion chapter is basically explaining the “what” (what your study found) and the “so what?” (what the findings mean for the industry or research). This brings the study full circle and closes off the document.

Let’s recap – how to write a dissertation or thesis

You’re still with me? Impressive! I know that this post was a long one, but hopefully you’ve learnt a thing or two about how to write a dissertation or thesis, and are now better equipped to start your own research.

To recap, the 8 steps to writing a quality dissertation (or thesis) are as follows:

- Understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is – a research project that follows the research process.

- Find a unique (original) and important research topic

- Craft a convincing dissertation or thesis research proposal

- Write a clear, compelling introduction chapter

- Undertake a thorough review of the existing research and write up a literature review

- Undertake your own research

- Present and interpret your findings

Once you’ve wrapped up the core chapters, all that’s typically left is the abstract , reference list and appendices. As always, be sure to check with your university if they have any additional requirements in terms of structure or content.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

20 Comments

thankfull >>>this is very useful

Thank you, it was really helpful

unquestionably, this amazing simplified way of teaching. Really , I couldn’t find in the literature words that fully explicit my great thanks to you. However, I could only say thanks a-lot.

Great to hear that – thanks for the feedback. Good luck writing your dissertation/thesis.

This is the most comprehensive explanation of how to write a dissertation. Many thanks for sharing it free of charge.

Very rich presentation. Thank you

Thanks Derek Jansen|GRADCOACH, I find it very useful guide to arrange my activities and proceed to research!

Thank you so much for such a marvelous teaching .I am so convinced that am going to write a comprehensive and a distinct masters dissertation

It is an amazing comprehensive explanation

This was straightforward. Thank you!

I can say that your explanations are simple and enlightening – understanding what you have done here is easy for me. Could you write more about the different types of research methods specific to the three methodologies: quan, qual and MM. I look forward to interacting with this website more in the future.

Thanks for the feedback and suggestions 🙂

Hello, your write ups is quite educative. However, l have challenges in going about my research questions which is below; *Building the enablers of organisational growth through effective governance and purposeful leadership.*

Very educating.

Just listening to the name of the dissertation makes the student nervous. As writing a top-quality dissertation is a difficult task as it is a lengthy topic, requires a lot of research and understanding and is usually around 10,000 to 15000 words. Sometimes due to studies, unbalanced workload or lack of research and writing skill students look for dissertation submission from professional writers.

Thank you 💕😊 very much. I was confused but your comprehensive explanation has cleared my doubts of ever presenting a good thesis. Thank you.

thank you so much, that was so useful

Hi. Where is the excel spread sheet ark?

could you please help me look at your thesis paper to enable me to do the portion that has to do with the specification

my topic is “the impact of domestic revenue mobilization.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Study and research support

- Academic skills

Dissertation examples

Listed below are some of the best examples of research projects and dissertations from undergraduate and taught postgraduate students at the University of Leeds We have not been able to gather examples from all schools. The module requirements for research projects may have changed since these examples were written. Refer to your module guidelines to make sure that you address all of the current assessment criteria. Some of the examples below are only available to access on campus.

- Undergraduate examples

- Taught Masters examples

- How it works

Full Dissertation Samples and Examples

Students often face difficulty in starting their dissertations. One way to cater to this problem is to look at samples of full dissertations available online. We understand this problem. Therefore, our professionals have curated expert full dissertation examples for students to get inspired by and start working on their own dissertations.

Full Dissertation Sample

Discipline: Economics

Quality: 1st / 78%

Discipline: Business

Quality: 1st / 74%

Discipline: Big Data

Quality: 2:1 / 68%

Undergraduate

Discipline: Engineering Management

Quality: 2:1 / 69%

Discipline: Business Management

Discipline: Project Management

Quality: 1st / 73%

Discipline: Physiotherapy

Quality: 1st / 79%

Discipline: Marketing

Quality: 1st / 76%

Discipline: HRM

Discipline: Civil Engineering

Theism and Ultimate Explanation of the Existence of God” against ….

Dissertation

Extraversion and Occupational Choice

Feeding and resource buffers in ccpm and the impact of their use …..

Project Management

Impact of the Global Financial Crisis 2008-2009 on the UK ….

Material selection for innovative design of automotive component.

Engineering

Cognitive Process of Entrepreneurs in the Examination ….

Entrepreneurship

The Impact of Gender on Purchase Decision and Buying Behaviour ….

The leadership styles of successful project managers …., why manchester united football club has been one of the most successful sports …., investigating the impact of employee engagement on organisational performance…., should countries implement a constitutional court for fundamental rights breaches, optimising global supply chain operations: a collection of undergraduate dissertation samples.

Supply Chain

Newspaper coverage of refugees from Mainland China between 1937 and 1941 in Hong Kong

Our full dissetation features, customised dissertations.

These examples of a full dissertation are just for reference. We provide work based on your requirements.

Expert Writers

We have professional dissertation writers in each field to complete your dissertations.

Quality Control

These expert full dissertation examples showcase the quality of work that can be expected from us.

Plagiarism Free

We ensure that our content is 100% plagiarism free and checked with paid tools.

Proofreading

The dissertations are proofread by professionals to remove any errors before delivery.

We set our prices according to the affordability of the majority of students so everyone can avail.

Loved by over 100,000 students

Thousands of students have used ResearchProspect academic support services to improve their grades. Why are you waiting?

"I was having the hardest time starting my dissertation. I went online and checked their full dissertation samples. It helped me a lot! "

Law Student

"Trusting someone with your work is hard. I wanted a reliable resource. I saw their full dissertation samples and immediately placed my order. "

Literature Student

What is a Dissertation?

A dissertation is a complex and comprehensive academic project students must complete towards the end of their degree programme. It requires deep independent research on a topic approved by your tutor. A dissertation contains five chapters – introduction, literature review, methodology, discussion, and conclusion. This is the standard structure for a dissertation unless stated otherwise by your tutor or institution.

Writing a Dissertation Proposal

After selecting a topic, the next step is preparing a proposal. A dissertation proposal is a plan or outline of the research you intend to conduct. It gives a background to the topic, lays out your research aims and objectives, and gives details of the research methodology you intend to use.

If your university accepts your proposal, you can start work on the dissertation paper. If it’s not accepted at first, make amendments to the proposal based on your supervisor’s feedback.

Referencing

Referencing is not some little detail at the end of the paper. Without correct referencing, even a brilliant paper can fail miserably. Citing every source accurately is an absolute must.

Don't Neglect Small Details.

Completing a dissertation proves you can carry out something thoroughly. Therefore, you should attend to each part of the dissertation and omit nothing.

Things like creating a table of contents with the page numbers listed, the reference list, and appendices are all parts of a dissertation. They all contribute to your grade. Look at our dissertation samples and writing guides to get a good understanding.

Choosing Your Dissertation Topic

Choosing a dissertation topic is the first step towards writing a dissertation. However, you should make sure the topic is relevant to your degree programme. It should investigate a specific problem and contribute towards the existing literature.

In order to stay motivated throughout the process, the research topic should be in line with your interests. At ResearchProspect, our expert academics can provide you with unique, manageable topics so you can choose one that suits your needs. Whether you’re an undergraduate or postgraduate student, topics from ResearchProspect can go a long way towards helping you achieve your desired grade.

How to Write a Dissertation

Acceptance of your dissertation proposal is the starting signal. Check out our dissertation writing service and look through our thesis samples to grasp the typical writing style.

Structure of a Dissertation

You have a topic and it’s been accepted. Now comes the structure and format. The first chapter will introduce the topic, the second should then explore it deeply and discuss relevant models, frameworks, and concepts.

The third chapter is where you explain your methodology in detail. The fourth and fifth chapters are for discussing the results and concluding the research, respectively.

Our full dissertation samples and writing guides will help you better understand dissertation structure and formatting.

How ResearchProspect Can Help!

Looking for dissertation help? At ResearchProspect, we know how difficult producing a first-class dissertation is. When you have other projects on, it’s particularly demanding.

Head to our order form. You can place your order today. If you’re not ready to commit yet, just message us about your project and what you’re considering. We have experts to write your full dissertation to your requirements.

Explore More Samples

View our professional samples to be certain that we have the portofilio and capabilities to deliver what you need.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

- Study With Us

Dissertation Examples

- Undergraduate Research Opportunities

- Student Voice

- Peer-to-Peer Support

- The Econverse Podcast

- Events and Seminars

- China School Website

- Malaysia School Website

- Email this Page

Students in the School of Economics at the University of Nottingham consistently produce work of a very high standard in the form of coursework essays, dissertations, research work and policy articles.

Below are some examples of the excellent work produced by some of our students. The authors have agreed for their work to be made available as examples of good practice.

Undergraduate dissertations

- The Causal Impact of Education on Crime Rates: A Recent US Analysis . Emily Taylor, BSc Hons Economics, 2022

- Does a joint income taxation system for married couples disincentivise the female labour supply? Jodie Gollop, BA Hons Economics with German, 2022

- Conditional cooperation between the young and old and the influence of work experience, charitable giving, and social identity . Rachel Moffat, BSc Hons Economics, 2021

- An Extended Literature Review on the Contribution of Economic Institutions to the Great Divergence in the 19th Century . Jessica Richens, BSc Hons Economics, 2021

- Does difference help make a difference? Examining whether young trustees and female trustees affect charities’ financial performance. Chris Hyland, BSc Hons Economics, 2021

Postgraduate dissertations

- The impact of Covid-19 on the public and health expenditure gradient in mortality in England . Alexander Waller, MSc Economic Development & Policy Analysis, 2022

- Impact of the Child Support Grant on Nutritional Outcomes in South Africa: Is there a ‘pregnancy support’ effect? . Claire Lynam, MSc Development Economics, 2022

- An Empirical Analysis of the Volatility Spillovers between Commodity Markets, Exchange Rates, and the Sovereign CDS Spreads of Commodity Exporters . Alfie Fox-Heaton, MSc Financial Economics, 2022

- The 2005 Atlantic Hurricane Season and Labour Market Transitions . Edward Allenby, MSc Economics, 2022

- The scope of international agreements . Sophia Vaaßen, MSc International Economics, 2022

Thank you to all those students who have agreed to have their work showcased in this way.

School of Economics

Sir Clive Granger Building University of Nottingham University Park Nottingham, NG7 2RD

Legal information

- Terms and conditions

- Posting rules

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Charity gateway

- Cookie policy

Connect with the University of Nottingham through social media and our blogs .

Department of History

Dissertations.

Since 2009, we have published the best of the annual dissertations produced by our final year undergraduates and award a 'best dissertation of the year' prize to the best of the best.

- Best Dissertations of 2022

- Best Dissertations of 2021

- Best Dissertations of 2020

- Best Dissertations of 2019

- Best Dissertations of 2018

- Best Dissertations of 2017

- Best Dissertations of 2016

- Best Dissertations of 2015

- Best Dissertations of 2014

- Best Dissertations of 2013

- Best Dissertations of 2012

- Best Dissertations of 2011

- Best Dissertations of 2010

- B est Dissertations of 2009

Dissertation

Ai generator.

Dissertations are structured documents that present findings, arguments, and conclusions in a formal manner. They demonstrate a student’s ability to conduct independent research, critically evaluate literature, and communicate complex ideas effectively.

What is a Dissertation?

A dissertation is a comprehensive research project often pursued at the postgraduate level. It involves extensive study, analysis, and original contributions to a specific field. Dissertations showcase a student’s ability to conduct independent research, critically evaluate literature, and communicate complex ideas effectively.

Pronunciation of Dissertation

- American English Pronunciation : In American English, “dissertation” is pronounced as /ˌdɪs.ərˈteɪ.ʃən/.

- British English Pronunciation : In British English, the pronunciation is /ˌdɪs.əˈteɪ.ʃən/.

- Dis- : This syllable is pronounced with a short “i” sound, like in the word “this”.

- -ser- : The middle syllable is pronounced with a short “e” sound, similar to “set”.

- -tay- : This part is pronounced with a long “a” sound, as in “day”.

- -shun : The final syllable has the “shun” sound, like in “mission”.

- The stress is typically on the second syllable in both American and British English.

- It’s important to enunciate each syllable clearly for correct pronunciation.

Types of Dissertations

- Conducts original research using empirical methods.

- Involves data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Common in scientific and social science disciplines.

- Focuses on analyzing and synthesizing existing literature.

- Examines theories, concepts, or debates within a field.

- May involve a systematic review or meta-analysis.

- Integrates theoretical knowledge with practical application.

- Often found in professional fields like education , business , or healthcare.

- Includes a reflective component on real-world experiences.

- Explores and develops new theories or conceptual frameworks.

- Emphasizes conceptual analysis and argumentation.

- Common in philosophy , theoretical physics , and humanities.

- Combines qualitative and quantitative research approaches.

- Offers a comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena.

- Utilizes both data collection methods for triangulation.

- Focuses on in-depth examination of a specific case or phenomenon.

- Provides detailed insights into real-life contexts .

- Often used in psychology , sociology, and business research.

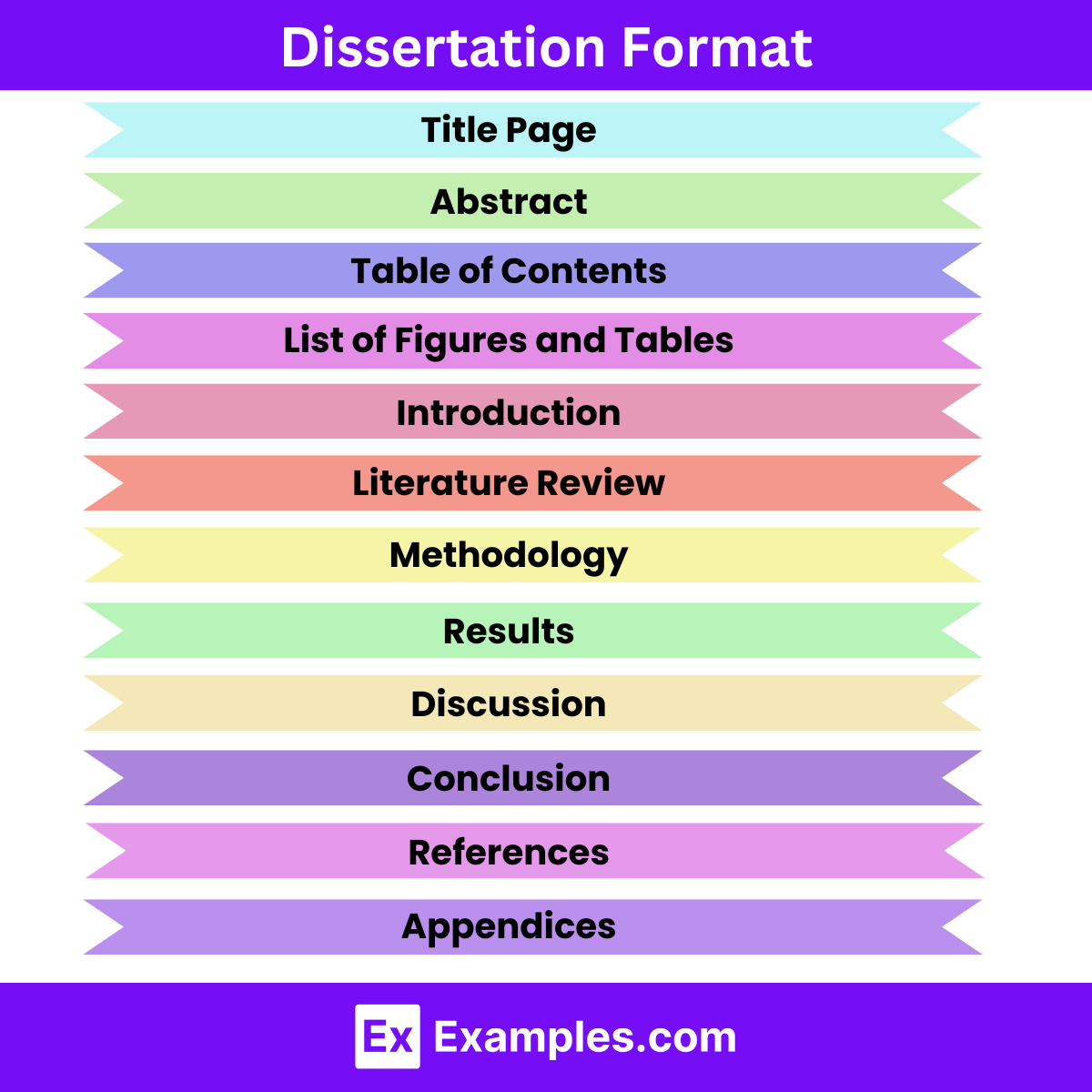

Dissertation Format

Here’s an overview of the typical format for a dissertation:

- Includes the title of the dissertation, author’s name, institution, department, degree program, date, and possibly the supervisor’s name.

- Provides a concise summary of the dissertation’s purpose, methodology, key findings, and conclusions.

- Usually limited to a certain word count or character limit.

- Lists the main sections and subsections of the dissertation with corresponding page numbers.

- Enumerates all figures and tables included in the dissertation, along with their respective page numbers.

- Sets the stage for the research by introducing the topic, context, significance, objectives, and research questions.

- Provides an overview of the structure of the dissertation.

- Surveys relevant literature and theoretical frameworks related to the research topic.

- Analyzes and synthesizes existing research to establish a theoretical foundation for the study.

- Describes the research design, methods, data collection procedures, and analysis techniques used in the study.

- Justifies the chosen methodology and explains how it aligns with the research objectives.

- Presents the findings of the research in a clear and organized manner.

- Includes tables, figures, and descriptive statistics to illustrate the data.

- Interprets the results in relation to the research questions, hypotheses, and theoretical framework.

- Analyzes the implications of the findings and discusses their significance in the broader context of the field.

- Summarizes the main findings and their implications for theory, practice, or policy.

- Reflects on the limitations of the study and suggests directions for future research.

- Lists all the sources cited in the dissertation in a consistent citation style (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago).

- Includes supplementary materials such as questionnaires, interview transcripts, or raw data.

- Provides additional details that support the main text but are not essential for understanding the dissertation.

Dissertation Topics

Here are some broad categories of dissertation topics, along with examples within each category:

- The impact of technology on student learning outcomes.

- Strategies for improving student engagement in online education.

- The effectiveness of inclusive education programs for students with disabilities.

- Assessing the role of parental involvement in children’s academic achievement.

- Investigating the relationship between teacher motivation and student performance.

- The influence of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior.

- Strategies for managing workplace diversity and inclusion.

- Analyzing the factors affecting employee job satisfaction and retention.

- The role of leadership styles in organizational change management.

- Exploring the impact of digital marketing on consumer purchase decisions.

- Assessing the effectiveness of telemedicine in improving patient access to healthcare services.

- Investigating the psychological effects of long-term illness on patients and their families.

- Analyzing the factors influencing healthcare professionals’ adoption of electronic health records.

- Exploring the role of preventive healthcare interventions in reducing the prevalence of chronic diseases.

- Assessing the impact of healthcare policies on healthcare equity and access.

- Understanding the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes among adolescents.

- Investigating the factors influencing public perceptions of climate change and environmental policies.

- Exploring the impact of immigration policies on immigrant integration and social cohesion.

- Analyzing the effects of income inequality on social mobility and economic development.

- Assessing the effectiveness of community-based interventions in reducing crime rates.

- Investigating the adoption and diffusion of renewable energy technologies in developing countries.

- Analyzing the ethical implications of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms.

- Exploring the role of blockchain technology in revolutionizing supply chain management.

- Assessing the impact of smart city initiatives on urban sustainability and quality of life.

- Investigating the factors influencing consumers’ acceptance of autonomous vehicles.

Synonym & Antonyms For Dissertation

How to write a dissertation.

Writing a dissertation is a comprehensive process that requires careful planning and execution. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write a dissertation:

- Select a topic that aligns with your interests, expertise, and the requirements of your academic program.

- Ensure the topic is researchable, relevant, and contributes to the existing body of knowledge in your field.

- Conduct a thorough literature review to familiarize yourself with existing research on your topic.

- Identify gaps, controversies, or unanswered questions that your dissertation can address.

- Develop research questions or hypotheses to guide your study.

- Outline the purpose, scope, objectives, and methodology of your dissertation in a research proposal.

- Seek feedback from your advisor or committee members and revise the proposal accordingly.

- Develop a detailed timeline or schedule for completing each stage of the dissertation writing process.

- Break down tasks into manageable chunks and set deadlines for completing each chapter or section.

- Start with the introduction, which provides background information, states the research objectives, and outlines the structure of the dissertation.

- Proceed to the literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion chapters, following the structure outlined in your proposal.

- Write each chapter systematically, using clear and concise language, and supporting your arguments with evidence from research.

- Review each draft of your dissertation carefully, focusing on clarity, coherence, and logical flow of ideas.

- Edit for grammar, punctuation, spelling, and formatting errors.

- Seek feedback from your advisor, peers, or academic writing support services, and incorporate suggested revisions.

- Compile all chapters, appendices, tables, figures, and references into a cohesive document.

- Ensure consistency in formatting and citation style throughout the dissertation.

- Proofread the final version to ensure accuracy and completeness.

- Submit the finalized dissertation to your advisor or committee for review and approval.

- Prepare for a dissertation defense, where you’ll present your research findings and answer questions from your committee.

- Address any feedback or revisions requested by your committee and finalize the dissertation for submission.

Dissertation vs. Thesis

Examples of dissertation in education.

- Investigating the effectiveness of flipped classroom approaches in enhancing student engagement and academic performance across various subjects.

- Analyzing the correlation between emotional intelligence levels among teachers and their ability to create supportive learning environments and facilitate student success.

- Examining the benefits of parental involvement in early childhood education and identifying effective strategies for promoting collaboration between families and schools.

- Investigating disparities in access to technology resources among students from different socio-economic backgrounds and exploring interventions to bridge the digital divide.

- Assessing the effectiveness of multicultural education programs in fostering cultural competence, diversity awareness, and inclusivity among students in diverse learning environments.

- Evaluating the effectiveness of social-emotional learning (SEL) interventions in promoting mental health, resilience, and well-being among students, teachers, and school staff.

- Identifying barriers to gender equity in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education and exploring strategies to encourage girls’ participation and success in STEM fields.

- Investigating the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of teachers related to assessment and exploring professional development initiatives to improve assessment literacy and enhance student learning outcomes.

- Examining the implementation of inclusive education policies and practices for students with disabilities, including challenges faced, effective strategies, and policy implications for inclusive schooling.

- Analyzing the impact of school leadership practices on teacher professional development, instructional quality, and overall school improvement efforts.

Examples of Dissertation in Psychology

- Investigating the relationship between social media usage patterns and the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues among adolescents.

- Examining the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in treating anxiety disorders and exploring the underlying mechanisms of therapeutic change.

- Assessing the long-term effects of different parenting styles (e.g., authoritarian, authoritative, permissive) on children’s emotional regulation, social skills, and overall development.

- Investigating the neurobiological mechanisms underlying addiction and exploring implications for developing more effective treatment and prevention strategies.

- Examining the factors that contribute to psychological resilience in individuals who have experienced trauma, such as childhood abuse, natural disasters, or combat exposure.

- Investigating the bidirectional relationship between sleep quality and mental health outcomes, including the impact of sleep disturbances on emotional regulation and psychological well-being.

- Comparing cultural differences in the conceptualization and assessment of personality traits, such as individualism-collectivism, and exploring implications for cross-cultural psychology.

- Evaluating the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions (e.g., mindfulness-based stress reduction, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy) in reducing stress, improving well-being, and enhancing psychological resilience.

- Examining the role of sociocultural factors (e.g., media influence, peer pressure) in shaping body image ideals and exploring interventions to prevent and treat eating disorders.

- Investigating the psychological processes underlying procrastination behavior, including motivational factors, self-regulation strategies, and interventions to promote task completion and productivity.

Examples of Dissertation in literature

- Understanding how stories from countries once colonized talk about who they are and where they fit in the world.

- Checking out how women are shown and what roles they have in old stories from the Victorian times.

- Finding out why scary stories from the past are still popular now and what they’re all about.

- Seeing how heroes are the same in stories from different places and why they’re important to us.

- Learning from stories that care about nature and how writers make us think about protecting the environment.

- Finding out why some new stories are tricky and playful with how they’re written, and what makes them special.

- Understanding how people who lived through terrible events tell their stories, and why it’s important.

- Seeing how Black artists in Harlem made cool stuff and changed how people think about Black culture.

- Exploring stories about moving to new places and how they mix different cultures together.

- Checking out how Shakespeare’s stories get turned into movies and other fun things we like today.

Examples of Dissertation in Politics

- Investigating how different types of political systems, such as democracies and autocracies, influence economic development and growth.

- Analyzing government policies and international agreements aimed at addressing climate change and their effectiveness in mitigating environmental degradation.

- Exploring the rise of populist movements and their impact on political polarization, democratic norms, and institutions.

- Examining the ethical and legal considerations surrounding humanitarian intervention and the protection of human rights in conflict zones.

- Investigating the role of nationalism and identity politics in shaping public attitudes towards immigration, multiculturalism, and social integration.

- Analyzing the effects of globalization on state sovereignty, economic policies, and the balance of power between states and multinational corporations.

- Comparing different electoral systems and their impact on political representation, party competition, and the functioning of democratic institutions.

- Examining the tension between national security concerns and civil liberties, particularly in the context of counterterrorism policies and surveillance practices.

- Assessing the barriers to women’s political participation and representation in decision-making roles, and exploring strategies for achieving gender equality in politics.

- Analyzing the role of the United Nations and other international organizations in addressing global challenges, such as conflict resolution, humanitarian crises, and sustainable development.

What exactly is a Dissertation?

A dissertation is a scholarly document that presents original research on a specific topic, typically completed as part of a doctoral program. It demonstrates the candidate’s ability to conduct independent research and contribute to their field of study.

How long is a Dissertation?

The length of a dissertation varies widely depending on the academic discipline, program requirements, and research topic. On average, it ranges from 80 to 200 pages, but some dissertations can be shorter or longer based on the depth and scope of the research.

What Do You Write a Dissertation For?

A dissertation is written as a culmination of doctoral studies to demonstrate a candidate’s ability to conduct independent research, contribute new knowledge to their field, and obtain a doctoral degree. It showcases expertise, critical thinking, and scholarly communication skills.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on 14 February 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 11 November 2022.

A dissertation proposal describes the research you want to do: what it’s about, how you’ll conduct it, and why it’s worthwhile. You will probably have to write a proposal before starting your dissertation as an undergraduate or postgraduate student.

A dissertation proposal should generally include:

- An introduction to your topic and aims

- A literature review of the current state of knowledge

- An outline of your proposed methodology

- A discussion of the possible implications of the research

- A bibliography of relevant sources

Dissertation proposals vary a lot in terms of length and structure, so make sure to follow any guidelines given to you by your institution, and check with your supervisor when you’re unsure.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Step 1: coming up with an idea, step 2: presenting your idea in the introduction, step 3: exploring related research in the literature review, step 4: describing your methodology, step 5: outlining the potential implications of your research, step 6: creating a reference list or bibliography.

Before writing your proposal, it’s important to come up with a strong idea for your dissertation.

Find an area of your field that interests you and do some preliminary reading in that area. What are the key concerns of other researchers? What do they suggest as areas for further research, and what strikes you personally as an interesting gap in the field?

Once you have an idea, consider how to narrow it down and the best way to frame it. Don’t be too ambitious or too vague – a dissertation topic needs to be specific enough to be feasible. Move from a broad field of interest to a specific niche:

- Russian literature 19th century Russian literature The novels of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky

- Social media Mental health effects of social media Influence of social media on young adults suffering from anxiety

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Like most academic texts, a dissertation proposal begins with an introduction . This is where you introduce the topic of your research, provide some background, and most importantly, present your aim , objectives and research question(s) .

Try to dive straight into your chosen topic: What’s at stake in your research? Why is it interesting? Don’t spend too long on generalisations or grand statements:

- Social media is the most important technological trend of the 21st century. It has changed the world and influences our lives every day.

- Psychologists generally agree that the ubiquity of social media in the lives of young adults today has a profound impact on their mental health. However, the exact nature of this impact needs further investigation.

Once your area of research is clear, you can present more background and context. What does the reader need to know to understand your proposed questions? What’s the current state of research on this topic, and what will your dissertation contribute to the field?

If you’re including a literature review, you don’t need to go into too much detail at this point, but give the reader a general sense of the debates that you’re intervening in.

This leads you into the most important part of the introduction: your aim, objectives and research question(s) . These should be clearly identifiable and stand out from the text – for example, you could present them using bullet points or bold font.

Make sure that your research questions are specific and workable – something you can reasonably answer within the scope of your dissertation. Avoid being too broad or having too many different questions. Remember that your goal in a dissertation proposal is to convince the reader that your research is valuable and feasible:

- Does social media harm mental health?

- What is the impact of daily social media use on 18– to 25–year–olds suffering from general anxiety disorder?

Now that your topic is clear, it’s time to explore existing research covering similar ideas. This is important because it shows you what is missing from other research in the field and ensures that you’re not asking a question someone else has already answered.

You’ve probably already done some preliminary reading, but now that your topic is more clearly defined, you need to thoroughly analyse and evaluate the most relevant sources in your literature review .

Here you should summarise the findings of other researchers and comment on gaps and problems in their studies. There may be a lot of research to cover, so make effective use of paraphrasing to write concisely:

- Smith and Prakash state that ‘our results indicate a 25% decrease in the incidence of mechanical failure after the new formula was applied’.

- Smith and Prakash’s formula reduced mechanical failures by 25%.

The point is to identify findings and theories that will influence your own research, but also to highlight gaps and limitations in previous research which your dissertation can address:

- Subsequent research has failed to replicate this result, however, suggesting a flaw in Smith and Prakash’s methods. It is likely that the failure resulted from…

Next, you’ll describe your proposed methodology : the specific things you hope to do, the structure of your research and the methods that you will use to gather and analyse data.

You should get quite specific in this section – you need to convince your supervisor that you’ve thought through your approach to the research and can realistically carry it out. This section will look quite different, and vary in length, depending on your field of study.

You may be engaged in more empirical research, focusing on data collection and discovering new information, or more theoretical research, attempting to develop a new conceptual model or add nuance to an existing one.

Dissertation research often involves both, but the content of your methodology section will vary according to how important each approach is to your dissertation.

Empirical research

Empirical research involves collecting new data and analysing it in order to answer your research questions. It can be quantitative (focused on numbers), qualitative (focused on words and meanings), or a combination of both.

With empirical research, it’s important to describe in detail how you plan to collect your data:

- Will you use surveys ? A lab experiment ? Interviews?

- What variables will you measure?

- How will you select a representative sample ?

- If other people will participate in your research, what measures will you take to ensure they are treated ethically?

- What tools (conceptual and physical) will you use, and why?

It’s appropriate to cite other research here. When you need to justify your choice of a particular research method or tool, for example, you can cite a text describing the advantages and appropriate usage of that method.

Don’t overdo this, though; you don’t need to reiterate the whole theoretical literature, just what’s relevant to the choices you have made.

Moreover, your research will necessarily involve analysing the data after you have collected it. Though you don’t know yet what the data will look like, it’s important to know what you’re looking for and indicate what methods (e.g. statistical tests , thematic analysis ) you will use.

Theoretical research

You can also do theoretical research that doesn’t involve original data collection. In this case, your methodology section will focus more on the theory you plan to work with in your dissertation: relevant conceptual models and the approach you intend to take.

For example, a literary analysis dissertation rarely involves collecting new data, but it’s still necessary to explain the theoretical approach that will be taken to the text(s) under discussion, as well as which parts of the text(s) you will focus on:

- This dissertation will utilise Foucault’s theory of panopticism to explore the theme of surveillance in Orwell’s 1984 and Kafka’s The Trial…

Here, you may refer to the same theorists you have already discussed in the literature review. In this case, the emphasis is placed on how you plan to use their contributions in your own research.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

You’ll usually conclude your dissertation proposal with a section discussing what you expect your research to achieve.

You obviously can’t be too sure: you don’t know yet what your results and conclusions will be. Instead, you should describe the projected implications and contribution to knowledge of your dissertation.

First, consider the potential implications of your research. Will you:

- Develop or test a theory?

- Provide new information to governments or businesses?

- Challenge a commonly held belief?

- Suggest an improvement to a specific process?

Describe the intended result of your research and the theoretical or practical impact it will have:

Finally, it’s sensible to conclude by briefly restating the contribution to knowledge you hope to make: the specific question(s) you hope to answer and the gap the answer(s) will fill in existing knowledge:

Like any academic text, it’s important that your dissertation proposal effectively references all the sources you have used. You need to include a properly formatted reference list or bibliography at the end of your proposal.

Different institutions recommend different styles of referencing – commonly used styles include Harvard , Vancouver , APA , or MHRA . If your department does not have specific requirements, choose a style and apply it consistently.

A reference list includes only the sources that you cited in your proposal. A bibliography is slightly different: it can include every source you consulted in preparing the proposal, even if you didn’t mention it in the text. In the case of a dissertation proposal, a bibliography may also list relevant sources that you haven’t yet read, but that you intend to use during the research itself.

Check with your supervisor what type of bibliography or reference list you should include.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, November 11). How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, what is a dissertation | 5 essential questions to get started, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

4 Common Types of Team Conflict — and How to Resolve Them

- Randall S. Peterson,

- Priti Pradhan Shah,

- Amanda J. Ferguson,

- Stephen L. Jones

Advice backed by three decades of research into thousands of team conflicts around the world.

Managers spend 20% of their time on average managing team conflict. Over the past three decades, the authors have studied thousands of team conflicts around the world and have identified four common patterns of team conflict. The first occurs when conflict revolves around a single member of a team (20-25% of team conflicts). The second is when two members of a team disagree (the most common team conflict at 35%). The third is when two subgroups in a team are at odds (20-25%). The fourth is when all members of a team are disagreeing in a whole-team conflict (less than 15%). The authors suggest strategies to tailor a conflict resolution approach for each type, so that managers can address conflict as close to its origin as possible.

If you have ever managed a team or worked on one, you know that conflict within a team is as inevitable as it is distracting. Many managers avoid dealing with conflict in their team where possible, hoping reasonable people can work it out. Despite this, research shows that managers spend upwards of 20% of their time on average managing conflict.

- Randall S. Peterson is the academic director of the Leadership Institute and a professor of organizational behavior at London Business School. He teaches leadership on the School’s Senior Executive and Accelerated Development Program.

- PS Priti Pradhan Shah is a professor in the Department of Work and Organization at the Carlson School of Management at the University of Minnesota. She teaches negotiation in the School’s Executive Education and MBA Programs.

- AF Amanda J. Ferguson is an associate professor of Management at Northern Illinois University. She teaches Organizational Behavior and Leading Teams in the School’s MBA programs.

- SJ Stephen L. Jones is an associate professor of Management at the University of Washington Bothell. He teaches Organizational and Strategic Management at the MBA level.

Partner Center

NASA's Mars sample return mission is in trouble. Could a single SLS megarocket be the answer?

NASA could get Mars samples back to Earth with a single launch of the Space Launch System rocket, Boeing says.

Boeing has put forward its own idea to help NASA get its Mars Sample Return project back on track and on budget.

NASA issued a solicitation for new ideas to get scientifically invaluable Martian material to Earth after being told the current plan is too expensive (about $11 billion), while also being too complex and facing scheduling issues.

Former NASA Chief Scientist Jim Green presented Boeing's vision for a rejiggered Mars sample return mission concept at the annual Humans to Mars Summit last week.

Related: NASA's Mars Sample Return in jeopardy after US Senate questions budget

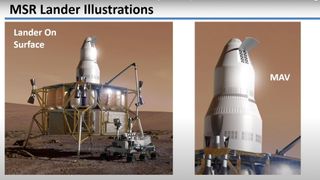

The concept centers on using NASA's Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, for which Boeing is a lead contractor. The giant rocket, which performed well during its first, and so far only, flight — the Artemis 1 moon mission in late 2022 — could carry all the hardware needed to pull off an ambitious, multi-spacecraft Mars sample return mission, according to Green.

"So, to reduce mission complexity — one of the top things NASA wants to do — this new concept is doing one launch," he said in his presentation.

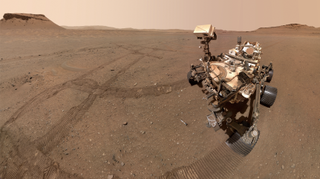

NASA's previous plan envisioned multiple launches to place a Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV) on the Martian surface, grab samples collected by the agency's Perseverance rover and return them to Earth. Boeing's single-shot concept would put a lander on Mars, with the help of an entry and descent aeroshell and a descent module with retro rockets, that could do all the work needed to get the precious samples home.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Boeing's proposed plan includes a fetch rover to retrieve Perseverance's samples. A two-stage MAV with a sample canister and an encapsulation system would be able to reach Mars orbit and then fire its engines to head home, instead of performing a Mars orbit rendezvous and docking with a transfer vehicle as in the original concept.

Ars Technica noted that, while attempting to cut costs, the use of the giant SLS would itself be expensive; a single launch would likely cost $2 billion at least. Contrary to Boeing's larger-MAV approach, NASA's initial re-thinking seemed to lean toward a smaller and cheaper MAV, and perhaps collecting fewer than the initially planned 43 sealed titanium tubes containing samples collected by Perseverance.

— Perseverance Mars rover stashes final sample, completing Red Planet depot

— Perseverance rover collects Mars samples rich in 'organic matter' for future return to Earth

— NASA's troubled Mars sample-return mission has scientists seeing red

NASA is accepting proposals through May 17 and will begin charting a new path forward on MSR later in the year.

The MSR project remains a high priority for NASA, agency administrator Bill Nelson said last month when announcing the project revamp.

Green noted that returning samples before potential human missions is crucial for understanding the Martian environment, including soil toxicity and resource availability.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Andrew is a freelance space journalist with a focus on reporting on China's rapidly growing space sector. He began writing for Space.com in 2019 and writes for SpaceNews, IEEE Spectrum, National Geographic, Sky & Telescope, New Scientist and others. Andrew first caught the space bug when, as a youngster, he saw Voyager images of other worlds in our solar system for the first time. Away from space, Andrew enjoys trail running in the forests of Finland. You can follow him on Twitter @AJ_FI .

India's ambitious 2nd Mars mission to include a rover, helicopter, sky crane and a supersonic parachute

Massive sunspot that brought widespread auroras to Earth now targets Mars

How to watch Blue Origin's NS-25 private space tourist mission online May 19

- Galacsi Nobody talks anymore of danger to the Earth biosphere from theses martian samples. So I ask a question : There has not been any danger from the start because there is no life on Mars, only equations to be solved, or the danger has disappeared ? Can you explain please. Reply

- Wolfshadw Dangers still exist. We just don't know. To my understanding, anything collected and returned to Earth (either from the Moon, Mars or an asteroid) is immediately classified as highly dangerous and placed into our highest level HAZMAT quarantine facility until deemed safe for our biosphere. Whether that is safe enough for humanity, again, we don't know. Ideally, sample returns would actually be captured by the crew of the ISS or some other orbiting platform and be thoroughly tested as a Bio-hazard before being returned to Earth. -Wolf sends Reply

Galacsi said: Nobody talks anymore of danger to the Earth biosphere from theses martian samples. So I ask a question : There has not been any danger from the start because there is no life on Mars, only equations to be solved, or the danger has disappeared ? Can you explain please.

- Torbjorn Larsson Outstanding questions: Which SLS version can deliver 25 mt to TMI? Current SLS block 1 can deliver 20 mt to TMI. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20205007434/downloads/SLS-PlanetaryDecadal-FINAL-LRP1 091420.pdfIs a 25 mt Mars EDL possible? Current massive lander was 1/10th that or a 2.4 mt EDL stage. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mars_Science_LaboratoryBoeing seems silent on their plan illustration including a Mars fetch rover mission.So far, relying on Perseverance for sample transport to MAV and a landed Starship craning down the current - or cheaper - MAV seems the ideal cheap mission for NASA. It would help SpaceX plans too. ESA can pay for the orbiter return stage. Reply

Mergatroid said: When the moon samples were returned to Earth, they were vetted, and the astronauts were quarantined for a while as well. All this has been thought of before hand.

- View All 5 Comments

Most Popular

- 2 James Webb Space Telescope sees Orion Nebula in a stunning new light (images)

- 3 NASA astronauts practice 'moonwalking' in the Arizona desert (photos)

- 4 Who is the 'Doctor Who' villain Maestro? And what's their relationship with the Toymaker?

- 5 Boeing's 1st Starliner astronaut launch delayed again, to May 25

The biggest bombshells from Michael Cohen's testimony were all in Trump's own words

- Michael Cohen gave his long-awaited testimony Monday in Trump's hush-money trial.

- Much of his most damning testimony came when he quoted what he described as Trump's own words.

- He testified that Trump knew exactly what was going on when Cohen paid hush money to Stormy Daniels.

When Michael Cohen was arranging hush-money payments for Stormy Daniels , he tried very hard to keep Donald Trump's name out of it.

But in his under-oath testimony for Trump's criminal trial on Monday, Cohen placed Trump firmly in the room where it happened.

Trump's attorney-turned-nemesis quoted his former boss extensively, telling jurors about key moments when the billionaire-turned-candidate participated fully in the plot to keep Daniels quiet ahead of the 2016 election.

The Manhattan district attorney's office has accused Trump of falsifying 34 different documents — including checks bearing Trump's signature — to hide an election-influencing, $130,000 hush-money payment that silenced the porn star 11 days before the vote.

Trump's legal team has cast all the blame on Cohen, suggesting he went rogue and came up with the hush-money scheme without the former president's approval.

On the witness stand, Cohen spoke cautiously, walking jurors through his long history as Trump's sometimes-bullying "fixer." Trump, having heard much of the story before, appeared almost bored at the defense table. For minutes at a time, he closed his eyes and leaned back in his chair without moving.

Here are nine key moments in Cohen's testimony when he did the greatest damage to his former boss simply by quoting what he said were Trump's own words.

1. "Just be prepared — there's going to be a lot of women coming forward."

Cohen, who began working for Trump in 2007, talked to Trump for years about running for president. Cohen testified that the real-estate mogul had considered a campaign in 2011 but ultimately decided against it, resolving to run in the "next election cycle."

In 2015, Trump told Cohen he would run for president.

"You know when this comes out," Cohen said, quoting Trump talking about the announcement, "just be prepared — there's going to be a lot of women coming forward."

It was in that context, Cohen said, that he met with the American Media Inc. publisher David Pecker in Trump Tower to discuss pushing positive stories about Trump in publications such as the National Enquirer and to get a heads-up about stories that could damage the campaign.

"What he said was that he could keep an eye out for anything negative about Mr. Trump and that he would be able to help us know in advance what was coming out and to try to stop it from coming out," Cohen testified.

2. "That's fantastic. That's unbelievable ."

The meeting with Pecker was a success.

The National Enquirer ran a series of positive articles about Trump and sensationalistic articles attacking his opponents. It claimed that Hillary Clinton wore "very thick glasses" to bolster a conspiracy theory of a brain injury, that Ted Cruz's father was photographed hanging out with Lee Harvey Oswald, and that Marco Rubio participated in a "drug binge" with a group of men in a swimming pool.

Trump was over the moon, Cohen testified.

"That's fantastic. That's unbelievable," Cohen quoted Trump as saying.

Pecker was happy , too, Cohen said. Trump's celebrity overlapped with the National Enquirer's target audience of people who bought magazines at grocery-store checkouts.

Trump's knowledge of how Cohen was working with the National Enquirer bolsters the prosecutors' theory that all these machinations were about supporting Trump's campaign. Personal issues — such as keeping news of an alleged affair away from Melania Trump — were secondary.

3. "Make sure it doesn't get released. "

In June of 2016, Cohen got a call from AMI telling him a former Playboy playmate, Karen McDougal , was shopping around a story about having sex with Trump.

When Cohen told Trump about it, his response was, "She's really beautiful," Cohen said.

"Okay. But there is a story that's right now being shopped," Cohen said he replied.

Trump supposedly said to Cohen, "Make sure it doesn't get released," instructing him to work with Pecker and the National Enquirer editor to purchase the rights to McDougal's story — and then make sure it never got to see the light of day.

Pecker came back to Cohen and said it'd cost $150,000 to "control the story," Cohen testified.

"No problem. I will take care of it," Cohen quoted Trump as saying.

4. "Do it. Take care of it."