Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Developing a Research Question

18 Hypotheses

When researchers do not have predictions about what they will find, they conduct research to answer a question or questions, with an open-minded desire to know about a topic, or to help develop hypotheses for later testing. In other situations, the purpose of research is to test a specific hypothesis or hypotheses. A hypothesis is a statement, sometimes but not always causal, describing a researcher’s expectations regarding anticipated finding. Often hypotheses are written to describe the expected relationship between two variables (though this is not a requirement). To develop a hypothesis, one needs to understand the differences between independent and dependent variables and between units of observation and units of analysis. Hypotheses are typically drawn from theories and usually describe how an independent variable is expected to affect some dependent variable or variables. Researchers following a deductive approach to their research will hypothesize about what they expect to find based on the theory or theories that frame their study. If the theory accurately reflects the phenomenon it is designed to explain, then the researcher’s hypotheses about what would be observed in the real world should bear out.

Sometimes researchers will hypothesize that a relationship will take a specific direction. As a result, an increase or decrease in one area might be said to cause an increase or decrease in another. For example, you might choose to study the relationship between age and legalization of marijuana. Perhaps you have done some reading in your spare time, or in another course you have taken. Based on the theories you have read, you hypothesize that “age is negatively related to support for marijuana legalization.” What have you just hypothesized? You have hypothesized that as people get older, the likelihood of their support for marijuana legalization decreases. Thus, as age moves in one direction (up), support for marijuana legalization moves in another direction (down). If writing hypotheses feels tricky, it is sometimes helpful to draw them out. and depict each of the two hypotheses we have just discussed.

Note that you will almost never hear researchers say that they have proven their hypotheses. A statement that bold implies that a relationship has been shown to exist with absolute certainty and that there is no chance that there are conditions under which the hypothesis would not bear out. Instead, researchers tend to say that their hypotheses have been supported (or not) . This more cautious way of discussing findings allows for the possibility that new evidence or new ways of examining a relationship will be discovered. Researchers may also discuss a null hypothesis, one that predicts no relationship between the variables being studied. If a researcher rejects the null hypothesis, he or she is saying that the variables in question are somehow related to one another.

Quantitative and qualitative researchers tend to take different approaches when it comes to hypotheses. In quantitative research, the goal often is to empirically test hypotheses generated from theory. With a qualitative approach, on the other hand, a researcher may begin with some vague expectations about what he or she will find, but the aim is not to test one’s expectations against some empirical observations. Instead, theory development or construction is the goal. Qualitative researchers may develop theories from which hypotheses can be drawn and quantitative researchers may then test those hypotheses. Both types of research are crucial to understanding our social world, and both play an important role in the matter of hypothesis development and testing. In the following section, we will look at qualitative and quantitative approaches to research, as well as mixed methods.

Text Attributions

- This chapter has been adapted from Chapter 5.2 in Principles of Sociological Inquiry , which was adapted by the Saylor Academy without attribution to the original authors or publisher, as requested by the licensor. © Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License .

An Introduction to Research Methods in Sociology Copyright © 2019 by Valerie A. Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 2. Sociological Research

2.1. Approaches to Sociological Research

When sociologists apply the sociological perspective and begin to ask questions, no topic is off limits. Every aspect of human behaviour is a source of possible investigation. Sociologists question the world that humans have created and live in. They notice patterns of behaviour as people move through the world. Using sociological methods and systematic research within the framework of the scientific method, sociologists have discovered workplace patterns that have transformed industries, family patterns that have enlightened parents, and education patterns that have aided structural changes in classrooms.

Depending on the focus and the type of research conducted, sociological findings could be useful in addressing any of the three basic interests or purposes of sociological knowledge discussed in the last chapter: the positivist interest in quantitative evidence to determine effective social policy decisions, the interpretive interest in understanding the meanings of human behaviour to foster mutual understanding and consensus, and the critical interest in knowledge useful for dismantling power relations and building alternatives to conditions of servitude. It might seem strange to use scientific practices to study social phenomena — a bit like the contents of a petri dish examining themselves — but, as argued above, if the goal of sociology is to improve the operation of society, it is extremely helpful to rely on systematic approaches that research methods provide.

Sociologists often begin the research process by asking a question about how or why things happen. It might be a unique question about a new trend or an old question about a common aspect of life. Once a question is formed, a sociologist proceeds through an in-depth process to answer it. Depending on the nature of the topic and the goals of the research, sociologists have a variety of methodologies to choose from. In deciding how to design that process, the researcher may adopt a positivist methodology or an interpretive methodology . Both types of methodology can be useful for critical research strategies . The following sections describe these approaches to acquiring knowledge.

Science vs. Non-Science

Contemporary society is going through an interesting time in which the certitudes and authority of science are frequently challenged. In the context of the natural sciences, people doubt scientific claims about climate change and the safety of vaccines. In the context of the social sciences, people doubt scientific claims about the declining rate of violent crime or the effectiveness of needle exchange programs. Sometimes there is a good reason to be skeptical about science, when scientific technologies prove to have adverse effects on the environment, for example. Sometimes skepticism has dangerous outcomes, when people act on conspiracy theories and misinformation or epidemics of diseases like measles suddenly break-out in schools due to low vaccination rates. In fact, skepticism is central to both natural and social sciences; but from a scientific point of view, the skeptical attitude needs to be combined with systematic research in order for knowledge to move forward.

In sociology, science provides the basis for being able to distinguish between everyday opinions or beliefs and propositions that can be sustained by evidence. In his paper, The Normative Structure of Science (1942/1973), the sociologist Robert Merton argued that science is a type of empirical knowledge organized around four key principles, often referred to by the acronym CUDOS :

- Communalism: The results of science must be made available to the public; science is freely available, shared knowledge, open to public discussion and debate.

- Universalism: The results of science must be evaluated based on universal criteria, not parochial criteria specific to the researchers themselves.

- Disinterestedness: Science must not be pursued for private interests or personal reward.

- Organized Skepticism: The scientist must abandon all prior intellectual commitments, critically evaluate claims, and postpone conclusions until sufficient evidence has been presented; scientific knowledge is provisional.

For Merton, therefore, non-scientific knowledge is knowledge that fails in various respects to meet these criteria. Types of esoteric or mystical knowledge, for example, might be valid for someone on a spiritual path, but because this knowledge is passed from teacher to student through direct transmission and it is not available to the public for open debate, or because the validity of this knowledge might be specific to the individual’s unique spiritual configuration, esoteric or mystical knowledge is not scientific per se . Claims that are presented to persuade (rhetoric), to achieve political goals (propaganda, of various sorts), or to make profits (advertising) are not scientific because these claims are structured to satisfy private interests. Propositions which fail to stand up to rigorous and systematic standards of evaluation are not scientific because they can not withstand the criteria of organized skepticism and scientific method.

The basic distinction between scientific and common, non-scientific claims about the world is that in science “seeing is believing” whereas in everyday life “believing is seeing” (Brym, Roberts, Lie, & Rytina, 2013). Science is, in crucial respects, based on systematic observation following the principles of CUDOS. Only on the basis of observation (or “seeing”) can a scientist believe that a proposition about the nature of the world is correct. Research methodologies are designed to reduce the chance that conclusions will be based on error. In everyday life, the order is typically reversed. People “see” what they already expect to see or what they already believe to be true. They do not systematically test what they believe to be true. Prior intellectual commitments or biases predetermine what people observe and the conclusions they draw.

Many people know things about the social world without having a background in sociology. Sometimes their knowledge is valid; sometimes it is not. It is important, therefore, to think about how people know what they know, and compare it to the scientific way of knowing. Four types of non-scientific reasoning are common in everyday life: knowledge based on casual observation, knowledge based on selective evidence, knowledge based on overgeneralization, and knowledge based on authority or tradition.

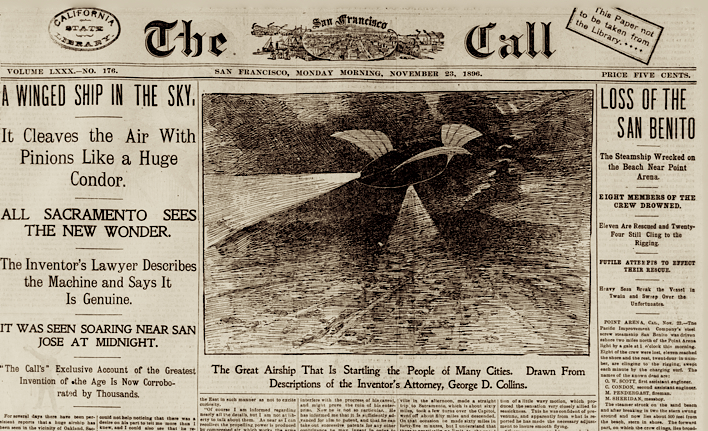

Many people know things simply because they have experienced them directly. Someone who has grown up in Manitoba has probably observed what plenty of kids learn each winter, that it really is true that one’s tongue will stick to metal when it is very cold outside. Direct experience may provide accurate information, but only if the observer is lucky. Unlike the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, in general, people are not very careful observers. In this example of the “winged ship” in Figure 2.4, the observation process is not deliberate or systematic. Instead, the observers come to know what they believe to be true through casual observation . The problem with casual observation is that sometimes it is right, and sometimes it is wrong. Without any systematic process for observing or assessing the accuracy of observations, a person can never really be sure if their informal observations are accurate.

Many people know things because they overlook disconfirming evidence. Suppose a friend declared that all men are liars shortly after she had learned that her boyfriend had deceived her. The fact that one man happened to lie to her in one instance came to represent a quality inherent in all men. But do all men really lie all the time? Probably not. If the friend is prompted to think more broadly about her experiences with men, she would probably acknowledge that she knew many men who, to her knowledge, had never lied to her and that maybe even her boyfriend did not generally make a habit of lying. This friend committed what social scientists refer to as selective observation by noticing only the pattern that she wanted to find at the time. She ignored disconfirming evidence. If, on the other hand, the friend’s experience with her boyfriend had been her only experience with a man, then she would have been committing what social scientists refer to as overgeneralization , assuming that broad patterns exist based on very limited observations.

Another way that people claim to know what they know is by looking to what they have always known to be true. There is an urban legend about a woman who for years used to cut both ends off of a ham before putting it in the oven (Mikkelson, 2005). She baked ham that way because that is the way her mother did it, so clearly that was the way it was supposed to be done. Her knowledge was based on a family tradition or traditional knowledge . After years of tossing cuts of perfectly good ham into the trash, however, she finally asked her mother why she did it and learned that the only reason her mother cut the ends off ham before cooking it was that she did not have a pan large enough to accommodate the ham without trimming it.

Without questioning what one thinks one knows is true, one may wind up believing things that are actually false. This is most likely to occur when an authority tells us that something is true, a case of authoritative knowledge . Mothers are not the only possible authorities people might rely on as sources of knowledge. Other common authorities people might rely on are political figures, churches and ministers, media influencers and social media networks. Although it is understandable that someone might believe something to be true if they look up to, or respect the person who has said it is so, this way of knowing differs from the sociological way of knowing. Whether quantitative, qualitative, or critical in orientation, sociological research is based on the scientific method.

The Scientific Method

Sociologists make use of tried-and-true methods of research, such as experiments, surveys, field research, and textual analysis. But humans and their social interactions are so diverse that they can seem impossible to chart or explain. It might seem that science is about discoveries and chemical reactions, or about proving hypotheses about elementary particles right or wrong, rather than about exploring the nuances of human behaviour. However, this is exactly why scientific models work for studying human behaviour. A scientific process of research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results. This is the case for both positivist quantitative methodologies, which seek to translate observable phenomena into unambiguous numerical data, and interpretive qualitative methodologies, which seek to translate observable phenomena into definable units of meaning. The social scientific method in both cases involves developing and testing theories about the world based on empirical (i.e., observable) evidence. The social scientific method is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the social world, and it strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical. It involves a series of established steps known as the research cycle .

No matter what research approach is used, researchers want to maximize the study’s reliability and validity . Reliability refers to how likely research results are to be replicated if the study is reproduced. Reliability increases the likelihood that what is true of one person will be true of all people in a group. Validity refers to how well the study measures what it was designed to measure. If the researcher wishes to examine people’s depth of religiosity — i.e., how strong is someone’s religious belief? How central is religious belief to their life? — does a measure like “frequency of church attendance” accurately measure that? Maybe not. People attend church for a variety of reasons and some religions are not organized on the basis of churches and congregations.

A subtopic in the field of political violence would be to examine the sources of homegrown radicalization: What are the conditions under which individuals in Canada move from a state of indifference or moderate concern with political issues to a state in which they are prepared to use violence to pursue political goals? The reliability of a study of radicalization reflects how well the social factors unearthed by the research apply to similar individuals who were not directly part of the research. Would another sociologist come up with the same results if they replicated the study? How well can the researcher extrapolate from the research subjects studied to individuals in the broader society? Does research on violent jihadi radicalization apply to violent neo-Nazi radicalization?

Validity ensures that the study’s design accurately examined what it was designed to study. Do the concepts and measures of radicalization accurately represent the actual experience of political radicals? An exploration of an individual’s propensity to plan or engage in violent acts or to go abroad to join a terrorist organization should address those specific issues and not confuse them with other topics such as why an individual adopts a particular faith or espouses radical political views. There is a key difference between religiosity, radicalization, and violent radicalization. As research from the UK and United States on jihadism has in fact shown, while jihadi terrorists typically identify with an Islamic world view, a well-developed Islamic identity counteracts jihadism . Similarly, research has shown that while it intuitively makes sense that people with radical views would adopt radical means like violence to achieve them, there is in fact no consistent homegrown terrorist profile, meaning that it is not possible to predict whether someone who espouses radical views will move on to committing violent acts without taking into account the specific stages in the process (Patel, 2011).

To ensure validity, research on political violence should focus on individuals who engage in political violence and be able to distinguish between simply holding radical political beliefs and acting violently on radical political beliefs. Dalgaard-Nielsen (2010) distinguishes between radical, radicalization, and violent radicalization as follows:

a radical is understood as a person harboring a deep-felt desire for fundamental sociopolitical changes and radicalization is understood as a growing readiness to pursue and support far reaching changes in society that conflict with, or pose a direct threat to, the existing order. [V]iolent radicalization [is]a process in which radical ideas are accompanied by the development of a willingness to directly support or engage in violent acts.

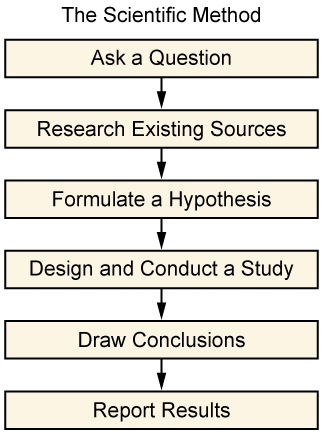

The scientific method provides a systematic, organized series of steps that help ensure objectivity and consistency in exploring a social problem. These steps provide the means for accuracy, reliability, and validity. Typically, the scientific method starts with these steps, which are described below: 1) ask a question; 2) research existing sources; and 3) formulate a hypothesis.

Ask a Question

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, describe a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a specific geographical location and time frame. “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?” would be too vague. The question should also be broad enough to have universal merit. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” would be too narrow. That said, happiness and hygiene are worthy topics to study.

Sociologists do not rule out any topic, but would strive to frame these questions in better research terms. That is why sociologists are careful to define their terms. Karl Popper (1902–1994) described the formulation of scientific propositions in terms of the concept of falsifiability (1963). He argued that the key demarcation between scientific and non-scientific propositions was not ultimately their factual truth, nor their verification, but simply whether or not they were stated in such a way as to be falsifiable; that is, whether a possible empirical observation could prove them wrong. If one claimed that evil spirits were the source of criminal behaviour, this would not be a scientific proposition because there is no possible way to definitively disprove it. Evil spirits cannot be observed. However, if one claimed that higher unemployment rates are the source of higher crime rates, this would be a scientific proposition because it is theoretically possible to find an instance where unemployment rates were not correlated to higher crime rates. As Popper said, “statements or systems of statements, in order to be ranked as scientific, must be capable of conflicting with possible, or conceivable, observations” (Popper, 1963).

Once a proposition is formulated in a way that would permit it to be falsified, the variables to be observed need to be operationalized. In a hygiene study, for instance, hygiene could be defined as “personal habits to maintain physical appearance (as opposed to health),” and a researcher might ask, “How do differing personal hygiene habits reflect the cultural value placed on appearance?” When forming these basic research questions, sociologists develop an operational definition ; that is, they define the concept in terms of the physical or concrete steps it takes to objectively measure it. The concept is translated into an observable variable , a measure that has different values. The operational definition identifies an observable condition of the concept.

By operationalizing a variable of the concept, all researchers can collect data in a systematic or replicable manner. The operational definition must be valid in the sense that it is an appropriate and meaningful measure of the concept being studied. It must also be reliable , meaning that results will be close to uniform when tested on more than one person. For example, good drivers might be defined in many ways: Those who use their turn signals; those who do not speed; or those who courteously allow others to merge. But these driving behaviours could be interpreted differently by different researchers, so they could be difficult to measure. Alternatively, “a driver who has never received a traffic violation” is a specific description that will lead researchers to obtain the same information, so it is an effective operational definition. Asking the question, “how many traffic violations has a driver received?” turns the concepts of “good drivers” and “bad drivers” into variables which might be measured by the number of traffic violations a driver has received. Of course the sociologist has to be wary of the way the variables are operationalized. In this example we know that black drivers are subject to much higher levels of police scrutiny than white drivers, so the number of traffic violations a driver has received might reflect less on their driving ability and more on the crime of “driving while black.”

Research Existing Sources

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review , which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to a university library and a thorough online search will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted on the topic at hand and enables them to position their own research to build on prior knowledge. It allows them to sharpen the focus of their research question and avoid duplicating previous research. Researchers — including student researchers — are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or sources that inform their work. While it is fine to build on previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly and never plagiarized. To study hygiene and its value in a particular society, a researcher might sort through existing research and unearth studies about childrearing, vanity, obsessive-compulsive behaviours, and cultural attitudes toward beauty. At the literature review stage it is important to sift through this information and determine what is relevant. Using existing sources educates a researcher by showing what others have found relevant about a topic, and helps refine and improve a study’s design.

Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an assumption about how two or more variables are related; it makes a conjectural statement about the relationship between those variables. It is an educated guess because it is not random but based on theory, observations, patterns of experience, or the existing literature. The hypothesis formulates this guess in the form of a testable or falsifiable proposition. However, how the hypothesis is handled differs between the positivist and interpretive approaches in sociology.

Hypothesis Formation in Positivist Research

Positivist methodologies are often referred to as hypothetico-deductive methodologies . A hypothesis is derived from a theoretical proposition. On the basis of the hypothesis, a prediction or generalization is logically deduced. If the prediction is confirmed by observation, the theoretical proposition is regarded as valid (at least provisionally). In positivist sociology, the hypothesis predicts how one form of human behaviour influences another. How does being a black driver affect the number of times the police will pull the driver over?

Successful prediction will determine the adequacy of the hypothesis and thereby test the theoretical proposition. Typically positivist approaches operationalize variables as quantitative data ; that is, by translating a social phenomenon like health into a quantifiable or numerically measurable variable like “number of visits to the hospital.” This permits sociologists to formulate their predictions using mathematical language, like regression formulas, to present research findings in graphs and tables, and to perform mathematical or statistical techniques to demonstrate the validity of relationships.

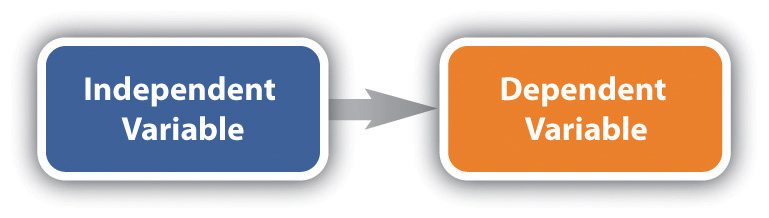

Variables are examined to see if there is a correlation between them. When a change in one variable coincides with a change in another variable there is a correlation. This does not necessarily indicate that changes in one variable causes a change in another variable, however — just that they are associated. A key distinction here is between independent and dependent variables. In research, independent variables are the cause of the change. The dependent variable is the effect, or thing that is changed. For example, in a basic study, the researcher would establish one form of human behaviour as the independent variable and observe the influence it has on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by level of education (the independent variable)?

For it to become possible to speak about causation , three criteria must be satisfied:

- There must be a relationship or correlation between the independent and dependent variables.

- The independent variable must be prior to the dependent variable.

- There must be no other intervening variable responsible for the causal relationship.

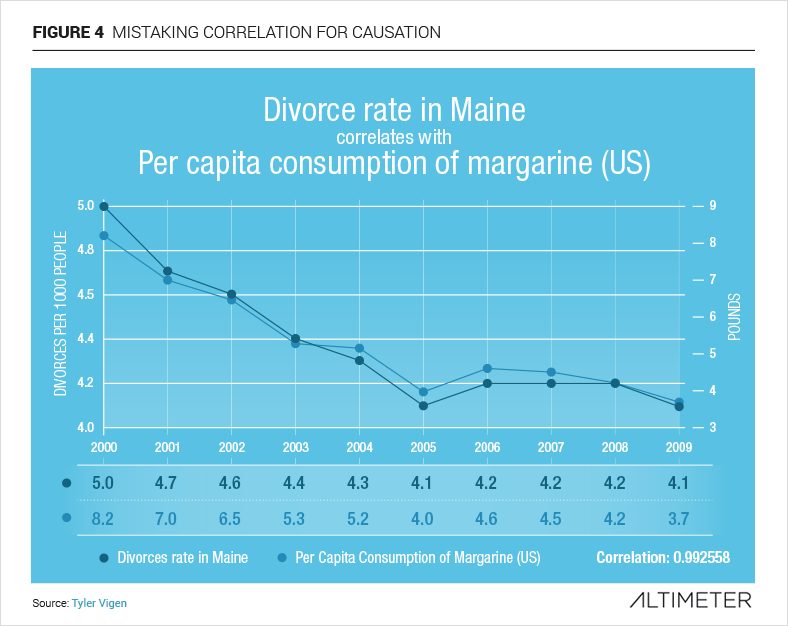

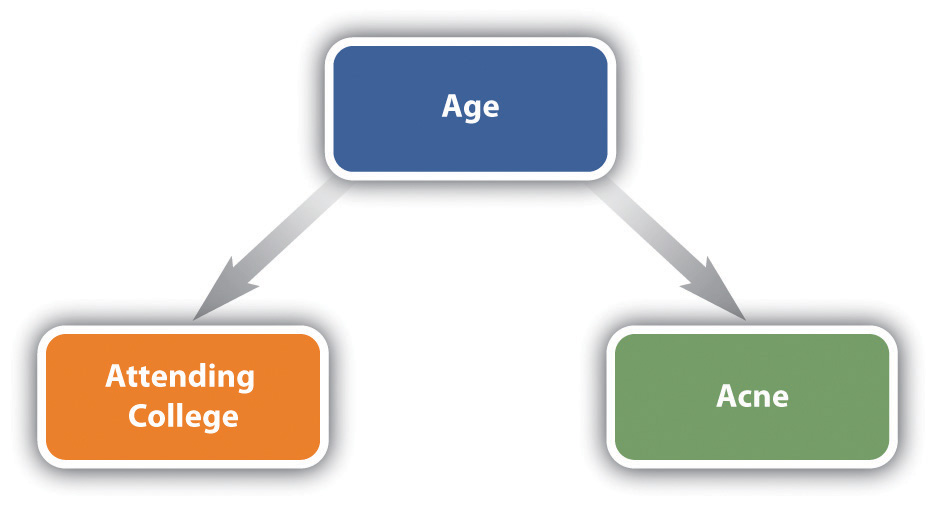

It is important to note that while there has to be a correlation between variables for there to be a causal relationship, correlation does not necessarily imply causation. The relationship between variables can be the product of a third intervening variable that is independently related to both. For example, there might be a positive relationship between wearing bikinis and eating ice cream, but wearing bikinis does not cause eating ice cream. It is more likely that the heat of summertime causes both an increase in bikini wearing and an increase in the consumption of ice cream.

The distinction between causation and correlation can have significant consequences. For example, Indigenous Canadians are overrepresented in prisons and arrest statistics. As noted in Chapter 1. An Introduction to Sociology , in 2020 Indigenous people accounted for about 5% of the Canadian population, but they made up 30% of the federal penitentiary population (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2020). There is a positive correlation between being an Indigenous person in Canada and being in jail. Is this because Indigenous people are racially or biologically predisposed to crime? No. In fact there are at least four intervening variables that explain the higher incarceration of Indigenous people (Hartnagel, 2004): Indigenous people are disproportionately poor and poverty is associated with higher arrest and incarceration rates; Indigenous lawbreakers tend to commit more detectable “street” crimes than the less detectable and actionable “white collar” crimes of other segments of the population; the criminal justice system disproportionately profiles and discriminates against Indigenous people; and the legacy of colonization has disrupted and weakened traditional sources of social control in Indigenous communities.

At this point, a researcher’s operational definitions help measure the variables. In a study asking how tutoring improves grades, for instance, one researcher might define “good” grades as a C or better, while another uses a B+ as a starting point for good. Another operational definition might describe “tutoring” as “one-on-one assistance by an expert in the field, hired by an educational institution.” Those definitions set limits and establish cut-off points, ensuring consistency and replicability in a study. As the chart shows, an independent variable is the one that causes a dependent variable to change. For example, a researcher might hypothesize that teaching children proper hygiene (the independent variable) will boost their sense of self-esteem (the dependent variable). Or rephrased, a child’s sense of self-esteem depends, in part, on the quality and availability of hygienic resources.

Of course, this hypothesis can also work the other way around. Perhaps a sociologist believes that increasing a child’s sense of self-esteem (the independent variable) will automatically increase or improve habits of hygiene (now the dependent variable). Identifying the independent and dependent variables is very important. As the hygiene example shows, simply identifying two topics, or variables, is not enough: Their prospective relationship must be part of the hypothesis. Just because a sociologist forms an educated prediction of a study’s outcome does not mean data contradicting the hypothesis are not welcome. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study, but they are equally interested in exceptions to patterns.

In a study of education, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding a rewarding career. While it has become at least a cultural assumption that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis knowing that results will vary.

Hypothesis Formation in Qualitative Research

While many sociologists rely on the positivist hypothetico-deductive method in their research, others operate from an interpretive approach . While still systematic, this approach typically does not follow the hypothesis-testing model that seeks to make generalizable predictions from quantitative variables. Instead, an interpretive framework seeks to understand social worlds from the point of view of participants, leading to in-depth knowledge. It focuses on qualitative data, or the meanings that guide people’s behaviour. Rather than relying on quantitative instruments, like fixed questionnaires or experiments, which can be artificial, the interpretive approach attempts to find ways to get closer to the informants’ lived experience and perceptions.

Interpretive research is generally more descriptive or narrative in its findings than positivist research. It can begin from a deductive approach by deriving a hypothesis from theory and then seeking to confirm it through methodologies like in-depth interviews. However, it is ideally suited to an inductive approach in which the hypothesis emerges only after a substantial period of direct observation or interaction with subjects. This type of approach is exploratory in that the researcher also learns as they proceed, sometimes adjusting the research methods or processes midway to respond to new insights and findings as they evolve.

For example, Glaser and Strauss’ (1967) classic elaboration of grounded theory proposed that qualitative researchers working with rich sources of qualitative data from interviews or ethnographic observations need to go through several stages of coding the data before a strong theory of the social phenomenon under investigation can emerge. In the initial stage, the researcher is simply trying to listen carefully and to tentatively categorize and sort the data. The researchers do not predetermine what the relevant categories of the social experience are, but analyze carefully what their subjects actually say. For example, what are the working definitions of health and illness that hospital patients use to describe their situation? In the first stage, the researcher tries to distinguish and succinctly code or label the numerous themes emerging from the data: different ways of describing the experience of health and illness. In the second stage, the researcher takes a more analytical approach by organizing the initial interview data into a few key reoccurring themes: Perhaps these are key assumptions that lay people make about the physiological mechanisms of the body, or the metaphors they use to describe their relationship to illness (e.g., a random occurrence, a battle, a punishment, a message, etc.). In the third stage, the researcher returns to the interview subjects with a new set of questions that would seek to either affirm, modify, or discard the analytical themes derived from the initial categorization of the interview material. This process can then be repeated back and forth until a thoroughly grounded theory is ready to be proposed. At every stage of the research, the researchers are obliged to follow the emerging data by revising their conceptions as new material is gathered, contradictions accounted for, commonalities categorized, and themes re-examined with further interviews.

Once the preliminary work is done and the hypothesis defined, it is time for the next research steps: choosing a research methodology, conducting a study, and drawing conclusions. These research steps are discussed below.

Making Connections: Classic Sociologists

Harriet martineau: the first woman sociologist.

As was noted in Chapter 1. An Introduction to Sociology , Harriet Martineau (1802–1876) was one of the first women sociologists in the 19th century. She was a British sociologist known at the time especially for her translation of August Comte’s sociological works. Particularly innovative was her early work on sociological methodology, How to Observe Manners and Morals (1838) . In this volume she developed the ground work for a systematic social-scientific approach to studying human behaviour. She recognized that the issues of the researcher-subject relationship would have to be addressed differently in a social science as opposed to a natural science.

The observer, or “traveler,” as she put it, needed to respect three criteria to obtain valid research: impartiality, critique, and sympathy. The impartial observer could not allow herself to be “perplexed or disgusted” by foreign practices that she could not personally reconcile herself with. Yet at the same time she saw the goal of sociology to be the fair but critical assessment of the moral status of a culture. In particular, the goal of sociology was to challenge forms of racial, sexual, or class domination in the name of autonomy: the right of every person to be a “self-directing moral being.” Finally, what distinguished the science of social observation from the natural sciences was that the researcher had to have unqualified sympathy for the subjects being studied (Lengermann & Niebrugge, 2007). This later became a central principle of Max Weber’s interpretive sociology, although it is not clear whether Weber read Martineau’s work.

A large part of her research in the United States analyzed the situations of contradiction between stated public morality and actual moral practices. For example, she was fascinated with the way that the formal democratic right to free speech enabled slavery abolitionists to hold public meetings, but when the meetings were violently attacked by mobs, the abolitionists and not the mobs were accused of inciting the violence (Zeitlin, 1997). This emphasis on studying contradictions followed from the distinction she drew between morals — society’s collective ideas of permitted and forbidden behaviour — and manners — the actual patterns of social action and association in society. As she realized the difficulty in getting an accurate representation of an entire society based on a limited number of interviews, she developed the idea that one could identify key “Things” experienced by all people — age, gender, illness, death, etc. — and examine how they were experienced differently by a sample of people from different walks of life (Lengermann & Niebrugge, 2007). Martineau’s pioneering sociology, therefore, focused on surveying different attitudes toward “Things,” and studying the anomalies that emerged when manners toward them contradicted a society’s formal morals.

Critical Research Strategies

As Karl Marx (1977 /1845) said: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.” Critical research strategies build on positivist and interpretive methodologies but bring the focus of research to the problems of social transformation and emancipation. Critical sociologists emphasize that the social world is not simply given or natural. It is the ongoing product of human actions and is therefore transformable. Domination and injustice are not inevitable. In this context, critical sociologists note that in a world characterized by extreme inequities and injustices, knowledge and ways of knowing can be caught up and implicated in power relations. “In a socially unjust world, knowledge of the social that does not challenge injustice is likely to play a role in reproducing it” (Carroll, 2004). Critical research strategies are therefore approaches that utilize positivist, interpretive, and critical methods to produce knowledge that maximizes the human potential for freedom and equality.

Paulo Freire’s (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed is a key reference point for critical research. Working with the illiterate poor in North-Eastern Brazil in the 1940s and 1950s, Freire recognized that effective education and knowledge were not simply about things, but were emancipatory practices themselves. Through the development of critical consciousness, people could understand the circumstances in which they were living and act effectively to change the conditions of oppression they experienced. This was the basis of critical pedagogy , an approach to teaching and learning based on fostering the agency of marginalized communities, and empowering learners to emancipate themselves from oppressive social structures.

Carroll (2004) describes three types of critical research strategy: Oppositional or activist strategies investigate and oppose visible structures and practices of domination by taking up the standpoint of the oppressed; Radical strategies focus on analyzing deeper systematic bases of domination at the roots of societal structures; Subversive strategies subvert or deconstruct received notions of reality/identity and everyday, common sense binary oppositions (man/woman, culture/nature, self/other, reason/emotion, Black/white, etc.), which opens the door to alternatives and new political spaces of contestation.

One contemporary application of critical research strategies is in the critique of colonial structures. Decolonization , or the process of dismantling colonial power structures, also involves a process of decolonizing knowledge and research methods. Eurocentric patterns of thinking are often embedded in the concepts and methods used in sociology and other disciplines. In the 19th century, for example, social hierarchies and evolutionary schemes were central to the understanding of Indigenous people in Canada as alternately “savage” and “childlike,” in need of suppressing, civilizing and assimilating. Decolonizing research “means centering concerns and world views of non-Western individuals, and respectfully knowing and understanding theory and research from previously ‘Other(ed)’ perspectives” (Thambinathan & Kinsella, 2021). Thambinathan & Kinsella (2021) outline four practices of decolonization:

- Exercising Critical Reflexivity: Critical reflexivity in research is about the researcher’s awareness of their own methodological assumptions — what they consider valid knowledge and proper ways of knowing — as well as of their social position (often as privileged outsiders) with respect to the research and the research subjects.

- Reciprocity and Respect for Self-Determination: Research should be practiced as an ongoing collaboration with research subjects to establish collective ownership over the entire research process, and to make accountable the researchers to the research subjects.

- Embracing Other(ed) Ways of Knowing: Research methods should be expanded to integrate traditional knowledge, theories and frameworks used by the research subjects.

Embodying a Transformative Praxis: Along the lines of Freire’s critical pedagogy, the goal of the research is to enable research subjects to transform the colonial conditions of their existence, to bring to light historically silenced voices, and to build capacities and agency in colonized peoples.

Image Descriptions

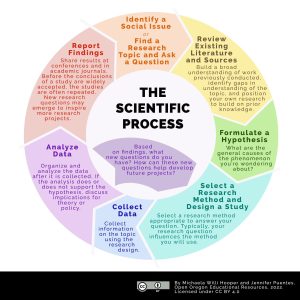

Figure 2.5 Long Description: The Scientific Method has a series of steps which can form a repeating cycle.

- Ask a question.

- Research existing sources

- Formulate a hypothesis.

- Design and conduct a study

- Draw conclusions.

- Report results. [Return to Figure 2.5]

Media Attributions

- Figure 2.3 Cover of The Strand Magazine featuring the publication of the last Sherlock Holmes story written by Arthur Conan Doyle from The Strand Magazine , vol. 73, April 1927, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4 “Mystery Airship” – Headline by The San Francisco Call, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain .

- Figure 2.5 The Scientific Method , by Heather Griffiths and Nathan Keirns, via OpenStax, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.6 Karl Popper in the 1980’s by LSE Library, via Wikimedia Commons, has no known copyright restrictions .

- Figure 2.7 Mistaking Correlation for Causation by Altimeter, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence .

- Figure 2.8 Harriet Martineau by Richard Evans, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain .

- Figure 2.9 Photo of Paulo Freire (1977) by Slobodan Dimitrov, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence.

Introduction to Sociology – 3rd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2023 by William Little is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Define and describe the scientific method.

- Explain how the scientific method is used in sociological research.

- Describe the function and importance of an interpretive framework.

- Describe the differences in accuracy, reliability, and validity in a research study.

When sociologists apply sociological thinking and begin to ask questions, no topic is off-limits. Every aspect of human behavior is a source of possible investigation. Sociologists question the world that humans have created and live in. They notice patterns of behavior as people move through that world. Using sociological methods within the framework of the scientific method and an interpretive perspective, sociologists have discovered social patterns in the workplace that have transformed industries, in families that have enlightened family members, and in education that have aided structural changes in classrooms.

Sociologists often begin the research process by asking a question about how or why things happen in this world. It might be a unique question about a new trend or an old question about a common aspect of life. Once the question is formed, the sociologist proceeds through an in-depth process to answer it. In deciding how to design that process, the researcher may adopt a scientific approach or an interpretive framework. The following sections describe these approaches to knowledge.

The Scientific Method

Sociologists make use of tried and true methods of research, such as experiments, surveys, and field research. But humans and their social interactions are so diverse that these interactions can seem impossible to chart or explain. It might seem that science is about discoveries and chemical reactions or about proving ideas right or wrong rather than about exploring the nuances of human behavior.

However, this is exactly why scientific models work for studying human behavior. A scientific process of research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results.

The scientific method involves developing and testing theories about the social world based on empirical evidence (i.e., “data”). It is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the empirical world and strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical. It involves a series of six prescribed steps that have been established over centuries of scientific scholarship.

Figure 2.2 The Scientific Method. 6 steps of the scientific method are an essential tool in research.

Sociological research does not reduce knowledge to right or wrong facts. Results of studies tend to provide people with insights they did not have before—explanations of human behaviors and social practices, access to knowledge and understandings of other cultural practices, rituals and beliefs, or trends and attitudes.

In general, sociologists tackle questions about the role of social characteristics in outcomes or results. For example, how do different communities fare in terms of psychological well-being, community cohesiveness, range of vocation, wealth, crime rates, and so on? Are communities functioning smoothly? Sociologists often look between the cracks to discover obstacles to meeting basic human needs. They might also study environmental influences and patterns of behavior that lead to crime, substance abuse, divorce, impoverishment, unplanned pregnancies, or illness. And, because sociological studies are not all focused on negative behaviors or challenging situations, social researchers might also study vacation trends, healthy eating habits, neighborhood organizations, higher education patterns, games, parks, dating practices, and exercise habits.

Sociologists use the scientific method to formulate and organize their research from start to finish–to decide how to collect and also how to interpret and analyze data. They deliberately apply scientific logic and objectivity . They are interested in—but not attached to—the results. They work outside of their own political or social agendas and biases. This does not mean researchers do not have their own personalities, complete with preferences and opinions, but sociologists deliberately use the scientific method to maintain as much objectivity, focus, and consistency as possible in collecting and analyzing data in their research.

With its systematic approach, the scientific method has proven useful in shaping sociological research. The scientific method provides a systematic, organized series of steps that help ensure objectivity and consistency in exploring a social problem. It provides the means for accuracy, reliability, and validity. In the end, the scientific method provides a shared basis for discussion and analysis (Merton 1963). Typically, the scientific method has 6 steps which are described below.

Step 1: Ask a Question or Find a Research Topic

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, select a problem, and identify a specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geographic location and time frame. For example, “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?”, would be too vague. With a little narrowing down though, “Are citizens in the United States happier today than they were in previous decades?” is something a sociologist could study. The question should also be broad enough to have universal merit. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” would be too narrow. Sociologists strive to frame questions that examine well-defined patterns and relationships.

In a hygiene study, for instance, hygiene could be defined as “personal habits to maintain physical appearance (as opposed to health),” and a researcher might ask, “How do differing personal hygiene habits reflect the cultural values placed on appearance in the United States?”

Step 2: Review the Literature/Research Existing Sources

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review , which is a review of any existing similar or related studies, typically in the social sciences. A visit to the library, a thorough online search, and a survey of academic journals uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted, identify gaps in understanding of the topic, and position their own research to add to prior knowledge that already exists on the topic. Researchers—including student researchers—are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or that inform their work. While it is fine to borrow previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly and never plagiarized.

To study crime, a researcher might also sort through existing data from the court system, police databases, prison information, or existing interviews with criminals, guards, wardens, etc. It’s important to examine this information in addition to existing research studies to determine how these resources might be used to fill holes in existing knowledge. Reviewing existing sources educates researchers and helps refine and improve the design of a research study.

Step 3: Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an explanation for a phenomenon based on a conjecture about the relationship between the phenomenon and one or more causal factors. In sociology, the hypothesis will often predict how one form of human behavior influences another. For example, a hypothesis might be in the form of an “if, then statement.” Let’s relate this to our topic of crime: If unemployment increases, crime rates will increase.

In scientific research, we formulate hypotheses to include independent variables (IV), which are the causes of the change, and a dependent variable (DV), which is the effect , or thing that is changed. In the example above, unemployment is the independent variable and the crime rate is the dependent variable.

In a sociological study, the researcher would establish one form of human behavior as the independent variable and observe the influence it has on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect the rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by educational attainment (the independent variable)?

Table 2.1 Examples of Dependent and Independent Variables Typically, the independent variable causes the dependent variable to change in some way.

Taking our example on hygiene above, a researcher might hypothesize that teaching children proper hygiene (the independent variable) will boost their sense of self-esteem (the dependent variable). Note, however, that this hypothesis can also work the other way around. A sociologist might predict that increasing a child’s sense of self-esteem (the independent variable) will increase or improve habits of hygiene (now the dependent variable). Identifying the independent and dependent variables is very important. As the hygiene example shows, simply identifying related two topics or variables is not enough. Their prospective relationship must be part of the hypothesis.

Step 4: Design and Conduct a Study

Sociologists design research studies to maximize reliability , which refers to how likely research results are to be replicated if the study is reproduced. Reliability increases the likelihood that what happens to one person will happen to all people in a group. Or, what will happen in one situation will happen in another. Cooking is a science. When you follow a recipe and measure ingredients with a cooking tool, such as a measuring cup, the same results are obtained as long as the cook follows the same recipe and uses the same type of tools. The measuring cup introduces accuracy into the process. If a person uses a less accurate tool, such as their hand, to measure ingredients rather than a measuring cup, the same results might not be replicated. Accurate tools and methods increase reliability.

Researchers also strive for validity , which refers to how well the study measures what it was designed to measure. To produce reliable and valid results, sociologists develop an operational definition, that is, they define each concept, or variable, in terms of the physical or concrete steps it takes to objectively measure it. The operational definition identifies an observable condition of the concept . By operationalizing the concept, all researchers can collect data in a systematic or replicable manner. Moreover, researchers can determine whether the experiment or method validly represents the phenomenon they intended to study.

A study asking how tutoring improves grades, for instance, might define “tutoring” as “one-on-one assistance by an expert in the field, hired by an educational institution.” However, one researcher might define a “good” grade as a C or better, while another uses a B+ as a starting point for “good.” For the results to be replicated and gain acceptance within the broader scientific community, researchers would have to use a standard operational definition. These definitions set limits and establish cut-off points that ensure consistency and replicability in a study.

We will explore research methods (i.e., how sociologists collect data) in greater detail in the next section of this chapter.

Step 5: Draw Conclusions

After constructing the research design, sociologists collect, tabulate, categorize, and analyze data to formulate conclusions. If the analysis supports the hypothesis, researchers can discuss the implications of the results for the theory or policy solution that they are addressing. If the analysis does not support the hypothesis, researchers may consider repeating the experiment or think of ways to improve the design of their research study.

However, even when results contradict a sociologist’s prediction of a study’s outcome, these results still contribute to sociological understanding. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study, but they are equally interested in exceptions to patterns. In a study of education, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding rewarding careers. While many assume that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis knowing that results may substantiate or contradict it.

Sociologists carefully keep in mind how operational definitions and research designs impact the results as they draw conclusions based on their studies. Consider the concept of, “increase in crime,” which might be defined as the percent increase in crime from last week to this week. Yet the data used to evaluate the “increase in crime” might be limited by many factors: who commits the crimes, where are the crimes committed, or what types of crimes are committed. If the data is gathered for “crimes committed in Houston, Texas in zip code 77021,” then it may not be generalizable to crimes committed in rural areas outside of major US cities like Houston. If data is collected about vandalism, it may not be generalizable to assault.

Step 6: Report Results

Researchers report their results at conferences and in academic journals. These results are then subjected to the scrutiny of other sociologists in the field. Before the conclusions of a study become widely accepted, the studies are often repeated in the same or different environments. In this way, sociological theories and knowledge develops as the relationships between social phenomenon are established in broader contexts and different circumstances.

Interpretive Framework

While many sociologists rely on empirical data and the scientific method as a research approach, others operate from an interpretive framework. While systematic, this approach doesn’t follow the hypothesis-testing model that seeks to find generalizable results. Instead, an interpretive framework, sometimes referred to as an interpretive perspective , seeks to understand social worlds from the point of view of participants, which leads to in-depth knowledge or understanding of the human experience.

Interpretive research is generally more descriptive or narrative in its findings. Rather than formulating a hypothesis and method for testing it, an interpretive researcher will develop approaches to explore the topic at hand that may involve a significant amount of direct observation or interaction with subjects including storytelling. This type of researcher learns through the process and sometimes adjusts the research methods or processes midway to optimize findings as they evolve.

Critical Sociology

Critical sociology focuses on the deconstruction of existing sociological research and theory. Informed by the work of Karl Marx, scholars known collectively as the Frankfurt School proposed that social science, as much as any academic pursuit, is embedded in the system of power constituted by the set of class, caste, race, gender, and other relationships that exist in the society. Consequently, it cannot be treated as purely objective. Critical sociologists view theories, methods, and conclusions as serving one of two purposes: they can either legitimate and rationalize systems of social power and oppression or liberate humans from inequality and restriction on human freedom. Deconstruction can involve data collection, but the analysis of this data is not empirical or positivist.

Introduction to Sociology Copyright © by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

3.2 Approaches to Sociological Research

When sociologists apply the sociological perspective and begin to ask questions, no topic is off limits. Every aspect of human behavior is a source of possible investigation. Sociologists question the world that humans have created and live in. They notice patterns of behavior as people move through that world. Using sociological methods and systematic research, sociologists have discovered social patterns in the workplace that have transformed industries and in education that have aided structural changes in classrooms.

Sociologists often begin the research process by asking a question about how or why things happen in this world. It might be a question about a new trend or a common aspect of life. Once the question is formed, the sociologist proceeds through an in-depth process to answer it. In deciding how to design that process, the researcher may adopt a scientific approach or an interpretive framework. The following sections describe these approaches to knowledge.

3.2.1 Developing a Research Question and the Steps of the Scientific Method

As sociology made its way into American universities, scholars developed it into a science that relies on research to build a body of knowledge. Sociologists began collecting data (observations and documentation) and applying the scientific method or an interpretative framework to increase understanding of societies and social interactions.

Our observations about social situations often incorporate biases based on our own views and limited data. To avoid subjectivity, sociologists conduct systematic research to collect and analyze empirical evidence from direct experience. Peers review the conclusions from this research. Examples of peer-reviewed research are found in scholarly journals.

Sociologists use a variety of methods for research, such as surveys, ethnographies (field research), and interviews. Humans and their social interactions are so diverse that these interactions can seem impossible to chart or explain. However, scientific models and the scientific process of research can be applied to the study of human behavior. A scientific approach to research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results.

The scientific method involves developing and testing theories about the social world based on empirical evidence. It is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the empirical world and strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical. The scientific method follows deductive reasoning, rather than the inductive approach we see with grounded theory. It involves a series of seven steps as shown in figure 3.2. Not every research project follows the steps in order, but this approach provides a plan for conducting research systematically.

Figure 3.2 outlines key stages in the research process. Please note that these stages or steps can be experienced as an ongoing process. Researchers and students undertaking projects may need to repeat steps as they go through the research process.

In general, sociologists tackle questions about the role of social characteristics in outcomes or results. For example, how do different communities fare in terms of community cohesiveness, employment, wealth, crime rates, and so on? Sociologists often look between the cracks to discover obstacles to meeting basic human needs. They might also study environmental influences and patterns of behavior that lead to crime, substance abuse, divorce, poverty, unplanned pregnancies, or illness. And, because sociological studies are not all focused on negative behaviors or challenging situations, social researchers might study vacation trends, neighborhood organizations, and higher education patterns.

Good research questions address sociological issues, connect to prior sociological research studies, are narrow enough that one study could help answer it, and can be examined through data (readily available or able to be collected given your time and resources) (Smith-Lovin and Moskovitz 2017:57). The process of designing research questions involves an emphasis on first reviewing the previous literature to identify connections the researcher should explore in their study (Loske 2017). This is something you will want to keep in mind; it is not uncommon for research questions to change overtime as you continue to incorporate new literature.

Sociologists can use the scientific method not only to collect but also to interpret and analyze data. They deliberately apply scientific logic and objectivity. They are interested in—but not attached to—the results. With its systematic approach, the scientific method has proven useful in shaping sociological studies. The scientific method provides a systematic, organized series of steps that help ensure consistency in exploring a social phenomena.

Step 1: Identify a Social Issue/Find a Research Topic and Ask a Question

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, select a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geographic location and time frame. “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?” would be too vague. The question should also be broad enough to be of significance. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” would be too narrow. Sociologists strive to frame questions that examine well-defined patterns and relationships.

Step 2: Review the Literature/Research Existing Sources

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review , which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to the library, a thorough online search, and a survey of academic journals will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted, identify gaps in understanding of the topic, and position their own research to build on prior knowledge. Researchers—including student researchers—are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or that inform their work. While it is fine to borrow previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly and never plagiarized. Reviewing existing sources educates researchers and helps refine and improve a research study design.

Step 3: Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an explanation for a phenomenon based on a conjecture about the relationship between the phenomenon and one or more causal factors. In sociology, the hypothesis will often predict how one form of human behavior influences another. For example, a hypothesis might be in the form of an “if, then statement.” Let’s relate this to our topic of crime: If unemployment increases, then the crime rate will increase.

In scientific research, we formulate hypotheses to include an independent variable (IV), which is the cause of the change, and a dependent variable (DV), which is the effect , or thing that is changed. In the example above, unemployment is the independent variable and the crime rate is the dependent variable.

With a sociological study, the researcher would establish one form of human behavior as the independent variable and observe the influence it has on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect the rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by level of education (the independent variable)? The table in Figure 3.3 demonstrates the relationship between a hypothesis, independent variable, and dependent variable.

Figure 3.3. Examples of Dependent and Independent Variables. Typically, the independent variable causes the dependent variable to change in some way.

Taking an example from figure 3.3, a researcher might hypothesize that teaching children proper hygiene (the independent variable) will boost their sense of self-esteem (the dependent variable). Note, however, this hypothesis can also work the other way around. A sociologist might predict that increasing a child’s sense of self-esteem (the independent variable) will increase or improve habits of hygiene (now the dependent variable). Identifying the independent and dependent variables is very important. As the hygiene example shows, simply identifying two related topics or variables is not enough. Their prospective relationship must be part of the hypothesis.

Step 4: Select a Research Method and Design a Study

Researchers select a research method that is appropriate to answer their research question in this step. Surveys, experiments, interviews, ethnography, and content analysis are just a few examples that researchers may use. You will learn more about these and other research methods later in this chapter in the section “Social Science Research Methods.” Typically your research question influences the type of methods that will be used.

Step 5: Collect Data

Next the researcher collects data. Depending on the research design (step 4), the researcher will begin the process of collecting information on their research topic. After all the data is gathered, the researcher will be able to systematically organize and analyze the data.

Step 6: Analyze the Data

After constructing the research design, sociologists collect, categorize, and analyze data to formulate conclusions. If the analysis supports the hypothesis, researchers can discuss what this might mean. For example, there could be implications for public policy or existing theories. If the analysis does not support the hypothesis, that can be an important finding to report. Some researchers may consider repeating the study or think of ways to improve their procedure (this step is more commonly seen with experiments).

Even when results contradict a sociologist’s prediction of a study’s outcome, the results still contribute to sociological understanding. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study, but they are equally interested in exceptions to patterns. In a study of education, for example, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding rewarding careers. While many assume that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis knowing that results may substantiate or contradict it.

Step 7: Report Findings

Researchers report their results at conferences and in academic journals. These results are then subjected to the scrutiny of other sociologists in the field. Before the conclusions of a study become widely accepted, the studies are often repeated in the same or different environments. In this way, sociological theories and knowledge develop as the relationships between social phenomena are established in broader contexts and different circumstances.

3.2.2 Interpretive Framework

While many sociologists rely on empirical data and the scientific method as a research approach, others operate from an interpretive framework. Interpretive framework is an approach that involves detailed understanding of a particular subject through observation, not through hypothesis testing. Interpretive frameworks allow researchers to have reflexivity so they can describe how their own social position influences what they research. By reflexivity, we refer to the ability of the researcher to examine how their own social position influences how and what they research. Reflexivity requires the researcher to evaluate how their own feelings, reactions and motives influence how they think and behave in a situation.

While systematic, this approach doesn’t follow the hypothesis-testing model that seeks to find generalizable results. Instead, an interpretive framework, sometimes referred to as an interpretive perspective or approach, seeks to understand social worlds from the point of view of participants, which leads to in-depth knowledge or understanding about the human experience. Ethnography is one research method that uses an interpretive framework. You will learn more about this method in the next section.

Interpretive research is generally more descriptive or narrative in its findings. Rather than formulating a hypothesis and method for testing it, an interpretive researcher will develop approaches to explore the topic at hand that may involve a significant amount of direct observation or interaction with subjects including storytelling. This type of researcher learns through the process and sometimes adjusts the research methods or processes midway to optimize findings as they evolve.

3.2.3 Grounded Theory

Grounded theory uses an interpretive framework to make sense of the social world. Grounded theory is an approach developed by sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss (1967) at a time when researchers were questioning positivism. As you learned in Chapter 2 , positivism refers to Auguste Comte’s theory that science produces universal laws, science controls what is true, and that objective methods allow you to pursue that truth. A counter perspective, anti-positivism , offers a different theoretical perspective that suggests social life cannot be studied with the same methods used in natural sciences. Instead there is a push to use a different approach.

Grounded theory offers a different approach to analysis that is sometimes used in qualitative research and aims to help with the development of theory (Charmaz 2003). This systematic theory is “grounded in” or based on observations. It uses induction or inductive reasoning, which means you use specific observations or evidence to arrive at broad conclusions. With grounded theory the research starts by gathering observations before creating categories to organize the data in. After initially organizing the data into categories, they begin to look for patterns and relationships among categories (Glaser and Strauss 1967). A few methods that may commonly utilize a grounded theory approach are participant observation, interviewing, and secondary data collection of artifacts and texts.

3.2.4 Critical Sociology

Critical sociology focuses on deconstruction of existing sociological research and theory. This approach to methods is nformed by the work of Karl Marx, and feminist, postmodern, postcolonial, and critical race scholars. These critical sociologists propose that social science is embedded in systems of power. Power is constituted by the set of class, caste, race, gender, and other relationships that exist in the society. We will take a closer look at these power relations in later chapters. Consequently, power cannot be treated as purely objective. Critical sociologists view theories, methods, and the conclusions as serving one of two purposes: they can either legitimize and rationalize systems of social power and oppression or liberate humans from inequality and restriction on human freedom. We’ll explore examples of this approach in the section, “Pedagogical Element: A Closer Look at Indigenous Knowledge and Decolonizing Research Methods” section later in this chapter.

3.2.5 Licenses and Attributions for Approaches to Sociological Research

“Approaches to Sociological Research” from “2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at

https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-1-approaches-to-sociological-research

“Developing a Research Question & the Steps of the Scientific Method” – First two paragraphs from “Introduction” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-introduction

Paragraphs 3 and 4 edited for consistency and brevity, Figure 3.3 and Step sections edited and modified from “2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-1-approaches-to-sociological-research

Figure 3.2. “Interpretive Framework” modified from “2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at

Interpretive framework definition modified from the Open Education Sociology Dictionary is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 .

Reflexivity definition modified from the Cambridge Dictionary is licensed under X

“Grounded Theory” is original content by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Anti – positivism definition is adapted from the Open Education Sociology Dictionary and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and from Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 .

“Critical Theory” remixed from “2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Edited for clarity. Access for free at

All other content in this section is original content by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .