- Home »

find your perfect postgrad program Search our Database of 30,000 Courses

How to write a masters dissertation or thesis: top tips.

It is completely normal to find the idea of writing a masters thesis or dissertation slightly daunting, even for students who have written one before at undergraduate level. Though, don’t feel put off by the idea. You’ll have plenty of time to complete it, and plenty of support from your supervisor and peers.

One of the main challenges that students face is putting their ideas and findings into words. Writing is a skill in itself, but with the right advice, you’ll find it much easier to get into the flow of writing your masters thesis or dissertation.

We’ve put together a step-by-step guide on how to write a dissertation or thesis for your masters degree, with top tips to consider at each stage in the process.

1. Understand your dissertation or thesis topic

There are slight differences between theses and dissertations , although both require a high standard of writing skill and knowledge in your topic. They are also formatted very similarly.

At first, writing a masters thesis can feel like running a 100m race – the course feels very quick and like there is not as much time for thinking! However, you’ll usually have a summer semester dedicated to completing your dissertation – giving plenty of time and space to write a strong academic piece.

By comparison, writing a PhD thesis can feel like running a marathon, working on the same topic for 3-4 years can be laborious. But in many ways, the approach to both of these tasks is quite similar.

Before writing your masters dissertation, get to know your research topic inside out. Not only will understanding your topic help you conduct better research, it will also help you write better dissertation content.

Also consider the main purpose of your dissertation. You are writing to put forward a theory or unique research angle – so make your purpose clear in your writing.

Top writing tip: when researching your topic, look out for specific terms and writing patterns used by other academics. It is likely that there will be a lot of jargon and important themes across research papers in your chosen dissertation topic.

2. Structure your dissertation or thesis

Writing a thesis is a unique experience and there is no general consensus on what the best way to structure it is.

As a postgraduate student , you’ll probably decide what kind of structure suits your research project best after consultation with your supervisor. You’ll also have a chance to look at previous masters students’ theses in your university library.

To some extent, all postgraduate dissertations are unique. Though they almost always consist of chapters. The number of chapters you cover will vary depending on the research.

A masters dissertation or thesis organised into chapters would typically look like this:

Write down your structure and use these as headings that you’ll write for later on.

Top writing tip : ease each chapter together with a paragraph that links the end of a chapter to the start of a new chapter. For example, you could say something along the lines of “in the next section, these findings are evaluated in more detail”. This makes it easier for the reader to understand each chapter and helps your writing flow better.

3. Write up your literature review

One of the best places to start when writing your masters dissertation is with the literature review. This involves researching and evaluating existing academic literature in order to identify any gaps for your own research.

Many students prefer to write the literature review chapter first, as this is where several of the underpinning theories and concepts exist. This section helps set the stage for the rest of your dissertation, and will help inform the writing of your other dissertation chapters.

What to include in your literature review

The literature review chapter is more than just a summary of existing research, it is an evaluation of how this research has informed your own unique research.

Demonstrate how the different pieces of research fit together. Are there overlapping theories? Are there disagreements between researchers?

Highlight the gap in the research. This is key, as a dissertation is mostly about developing your own unique research. Is there an unexplored avenue of research? Has existing research failed to disprove a particular theory?

Back up your methodology. Demonstrate why your methodology is appropriate by discussing where it has been used successfully in other research.

4. Write up your research

For instance, a more theoretical-based research topic might encompass more writing from a philosophical perspective. Qualitative data might require a lot more evaluation and discussion than quantitative research.

Methodology chapter

The methodology chapter is all about how you carried out your research and which specific techniques you used to gather data. You should write about broader methodological approaches (e.g. qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods), and then go into more detail about your chosen data collection strategy.

Data collection strategies include things like interviews, questionnaires, surveys, content analyses, discourse analyses and many more.

Data analysis and findings chapters

The data analysis or findings chapter should cover what you actually discovered during your research project. It should be detailed, specific and objective (don’t worry, you’ll have time for evaluation later on in your dissertation)

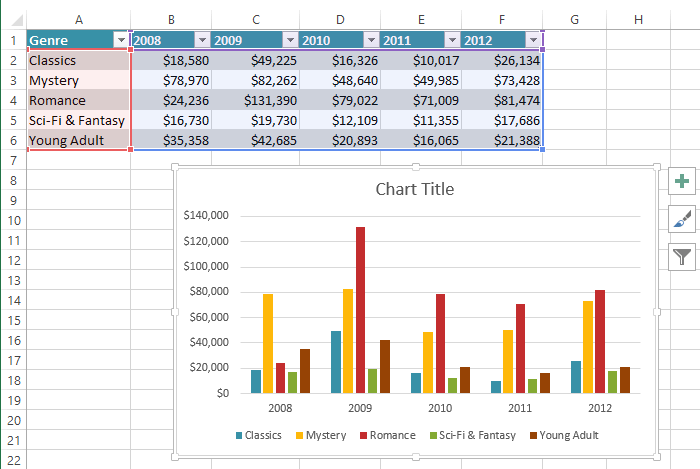

Write up your findings in a way that is easy to understand. For example, if you have a lot of numerical data, this could be easier to digest in tables.

This will make it easier for you to dive into some deeper analysis in later chapters. Remember, the reader will refer back to your data analysis section to cross-reference your later evaluations against your actual findings – so presenting your data in a simple manner is beneficial.

Think about how you can segment your data into categories. For instance, it can be useful to segment interview transcripts by interviewee.

Top writing tip : write up notes on how you might phrase a certain part of the research. This will help bring the best out of your writing. There is nothing worse than when you think of the perfect way to phrase something and then you completely forget it.

5. Discuss and evaluate

Once you’ve presented your findings, it’s time to evaluate and discuss them.

It might feel difficult to differentiate between your findings and discussion sections, because you are essentially talking about the same data. The easiest way to remember the difference is that your findings simply present the data, whereas your discussion tells the story of this data.

Your evaluation breaks the story down, explaining the key findings, what went well and what didn’t go so well.

In your discussion chapter, you’ll have chance to expand on the results from your findings section. For example, explain what certain numbers mean and draw relationships between different pieces of data.

Top writing tip: don’t be afraid to point out the shortcomings of your research. You will receive higher marks for writing objectively. For example, if you didn’t receive as many interview responses as expected, evaluate how this has impacted your research and findings. Don’t let your ego get in the way!

6. Write your introduction

Your introduction sets the scene for the rest of your masters dissertation. You might be wondering why writing an introduction isn't at the start of our step-by-step list, and that’s because many students write this chapter last.

Here’s what your introduction chapter should cover:

Problem statement

Research question

Significance of your research

This tells the reader what you’ll be researching as well as its importance. You’ll have a good idea of what to include here from your original dissertation proposal , though it’s fairly common for research to change once it gets started.

Writing or at least revisiting this section last can be really helpful, since you’ll have a more well-rounded view of what your research actually covers once it has been completed and written up.

Masters dissertation writing tips

When to start writing your thesis or dissertation.

When you should start writing your masters thesis or dissertation depends on the scope of the research project and the duration of your course. In some cases, your research project may be relatively short and you may not be able to write much of your thesis before completing the project.

But regardless of the nature of your research project and of the scope of your course, you should start writing your thesis or at least some of its sections as early as possible, and there are a number of good reasons for this:

Academic writing is about practice, not talent. The first steps of writing your dissertation will help you get into the swing of your project. Write early to help you prepare in good time.

Write things as you do them. This is a good way to keep your dissertation full of fresh ideas and ensure that you don’t forget valuable information.

The first draft is never perfect. Give yourself time to edit and improve your dissertation. It’s likely that you’ll need to make at least one or two more drafts before your final submission.

Writing early on will help you stay motivated when writing all subsequent drafts.

Thinking and writing are very connected. As you write, new ideas and concepts will come to mind. So writing early on is a great way to generate new ideas.

How to improve your writing skills

The best way of improving your dissertation or thesis writing skills is to:

Finish the first draft of your masters thesis as early as possible and send it to your supervisor for revision. Your supervisor will correct your draft and point out any writing errors. This process will be repeated a few times which will help you recognise and correct writing mistakes yourself as time progresses.

If you are not a native English speaker, it may be useful to ask your English friends to read a part of your thesis and warn you about any recurring writing mistakes. Read our section on English language support for more advice.

Most universities have writing centres that offer writing courses and other kinds of support for postgraduate students. Attending these courses may help you improve your writing and meet other postgraduate students with whom you will be able to discuss what constitutes a well-written thesis.

Read academic articles and search for writing resources on the internet. This will help you adopt an academic writing style, which will eventually become effortless with practice.

Keep track of your bibliography

The easiest way to keep the track of all the articles you have read for your research is to create a database where you can summarise each article/chapter into a few most important bullet points to help you remember their content.

Another useful tool for doing this effectively is to learn how to use specific reference management software (RMS) such as EndNote. RMS is relatively simple to use and saves a lot of time when it comes to organising your bibliography. This may come in very handy, especially if your reference section is suspiciously missing two hours before you need to submit your dissertation!

Avoid accidental plagiarism

Plagiarism may cost you your postgraduate degree and it is important that you consciously avoid it when writing your thesis or dissertation.

Occasionally, postgraduate students commit plagiarism unintentionally. This can happen when sections are copy and pasted from journal articles they are citing instead of simply rephrasing them. Whenever you are presenting information from another academic source, make sure you reference the source and avoid writing the statement exactly as it is written in the original paper.

What kind of format should your thesis have?

Read your university’s guidelines before you actually start writing your thesis so you don’t have to waste time changing the format further down the line. However in general, most universities will require you to use 1.5-2 line spacing, font size 12 for text, and to print your thesis on A4 paper. These formatting guidelines may not necessarily result in the most aesthetically appealing thesis, however beauty is not always practical, and a nice looking thesis can be a more tiring reading experience for your postgrad examiner .

When should I submit my thesis?

The length of time it takes to complete your MSc or MA thesis will vary from student to student. This is because people work at different speeds, projects vary in difficulty, and some projects encounter more problems than others.

Obviously, you should submit your MSc thesis or MA thesis when it is finished! Every university will say in its regulations that it is the student who must decide when it is ready to submit.

However, your supervisor will advise you whether your work is ready and you should take their advice on this. If your supervisor says that your work is not ready, then it is probably unwise to submit it. Usually your supervisor will read your final thesis or dissertation draft and will let you know what’s required before submitting your final draft.

Set yourself a target for completion. This will help you stay on track and avoid falling behind. You may also only have funding for the year, so it is important to ensure you submit your dissertation before the deadline – and also ensure you don’t miss out on your graduation ceremony !

To set your target date, work backwards from the final completion and submission date, and aim to have your final draft completed at least three months before that final date.

Don’t leave your submission until the last minute – submit your work in good time before the final deadline. Consider what else you’ll have going on around that time. Are you moving back home? Do you have a holiday? Do you have other plans?

If you need to have finished by the end of June to be able to go to a graduation ceremony in July, then you should leave a suitable amount of time for this. You can build this into your dissertation project planning at the start of your research.

It is important to remember that handing in your thesis or dissertation is not the end of your masters program . There will be a period of time of one to three months between the time you submit and your final day. Some courses may even require a viva to discuss your research project, though this is more common at PhD level .

If you have passed, you will need to make arrangements for the thesis to be properly bound and resubmitted, which will take a week or two. You may also have minor corrections to make to the work, which could take up to a month or so. This means that you need to allow a period of at least three months between submitting your thesis and the time when your program will be completely finished. Of course, it is also possible you may be asked after the viva to do more work on your thesis and resubmit it before the examiners will agree to award the degree – so there may be an even longer time period before you have finished.

How do I submit the MA or MSc dissertation?

Most universities will have a clear procedure for submitting a masters dissertation. Some universities require your ‘intention to submit’. This notifies them that you are ready to submit and allows the university to appoint an external examiner.

This normally has to be completed at least three months before the date on which you think you will be ready to submit.

When your MA or MSc dissertation is ready, you will have to print several copies and have them bound. The number of copies varies between universities, but the university usually requires three – one for each of the examiners and one for your supervisor.

However, you will need one more copy – for yourself! These copies must be softbound, not hardbound. The theses you see on the library shelves will be bound in an impressive hardback cover, but you can only get your work bound like this once you have passed.

You should submit your dissertation or thesis for examination in soft paper or card covers, and your university will give you detailed guidance on how it should be bound. They will also recommend places where you can get the work done.

The next stage is to hand in your work, in the way and to the place that is indicated in your university’s regulations. All you can do then is sit and wait for the examination – but submitting your thesis is often a time of great relief and celebration!

Some universities only require a digital submission, where you upload your dissertation as a file through their online submission system.

Related articles

What Is The Difference Between A Dissertation & A Thesis

How To Get The Most Out Of Your Writing At Postgraduate Level

Dos & Don'ts Of Academic Writing

Dispelling Dissertation Drama

Writing A Dissertation Proposal

Postgrad Solutions Study Bursaries

Exclusive bursaries Open day alerts Funding advice Application tips Latest PG news

Sign up now!

Take 2 minutes to sign up to PGS student services and reap the benefits…

- The chance to apply for one of our 5 PGS Bursaries worth £2,000 each

- Fantastic scholarship updates

- Latest PG news sent directly to you.

- LEARNING SKILLS

- Writing a Dissertation or Thesis

- Results and Discussion

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Learning Skills:

- A - Z List of Learning Skills

- What is Learning?

- Learning Approaches

- Learning Styles

- 8 Types of Learning Styles

- Understanding Your Preferences to Aid Learning

- Lifelong Learning

- Decisions to Make Before Applying to University

- Top Tips for Surviving Student Life

- Living Online: Education and Learning

- 8 Ways to Embrace Technology-Based Learning Approaches

- Critical Thinking Skills

- Critical Thinking and Fake News

- Understanding and Addressing Conspiracy Theories

- Critical Analysis

- Study Skills

- Exam Skills

- How to Write a Research Proposal

- Ethical Issues in Research

- Dissertation: The Introduction

- Researching and Writing a Literature Review

- Writing your Methodology

- Dissertation: Results and Discussion

- Dissertation: Conclusions and Extras

Writing Your Dissertation or Thesis eBook

Part of the Skills You Need Guide for Students .

- Research Methods

- Teaching, Coaching, Mentoring and Counselling

- Employability Skills for Graduates

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Writing your Dissertation: Results and Discussion

When writing a dissertation or thesis, the results and discussion sections can be both the most interesting as well as the most challenging sections to write.

You may choose to write these sections separately, or combine them into a single chapter, depending on your university’s guidelines and your own preferences.

There are advantages to both approaches.

Writing the results and discussion as separate sections allows you to focus first on what results you obtained and set out clearly what happened in your experiments and/or investigations without worrying about their implications.This can focus your mind on what the results actually show and help you to sort them in your head.

However, many people find it easier to combine the results with their implications as the two are closely connected.

Check your university’s requirements carefully before combining the results and discussions sections as some specify that they must be kept separate.

Results Section

The Results section should set out your key experimental results, including any statistical analysis and whether or not the results of these are significant.

You should cover any literature supporting your interpretation of significance. It does not have to include everything you did, particularly for a doctorate dissertation. However, for an undergraduate or master's thesis, you will probably find that you need to include most of your work.

You should write your results section in the past tense: you are describing what you have done in the past.

Every result included MUST have a method set out in the methods section. Check back to make sure that you have included all the relevant methods.

Conversely, every method should also have some results given so, if you choose to exclude certain experiments from the results, make sure that you remove mention of the method as well.

If you are unsure whether to include certain results, go back to your research questions and decide whether the results are relevant to them. It doesn’t matter whether they are supportive or not, it’s about relevance. If they are relevant, you should include them.

Having decided what to include, next decide what order to use. You could choose chronological, which should follow the methods, or in order from most to least important in the answering of your research questions, or by research question and/or hypothesis.

You also need to consider how best to present your results: tables, figures, graphs, or text. Try to use a variety of different methods of presentation, and consider your reader: 20 pages of dense tables are hard to understand, as are five pages of graphs, but a single table and well-chosen graph that illustrate your overall findings will make things much clearer.

Make sure that each table and figure has a number and a title. Number tables and figures in separate lists, but consecutively by the order in which you mention them in the text. If you have more than about two or three, it’s often helpful to provide lists of tables and figures alongside the table of contents at the start of your dissertation.

Summarise your results in the text, drawing on the figures and tables to illustrate your points.

The text and figures should be complementary, not repeat the same information. You should refer to every table or figure in the text. Any that you don’t feel the need to refer to can safely be moved to an appendix, or even removed.

Make sure that you including information about the size and direction of any changes, including percentage change if appropriate. Statistical tests should include details of p values or confidence intervals and limits.

While you don’t need to include all your primary evidence in this section, you should as a matter of good practice make it available in an appendix, to which you should refer at the relevant point.

For example:

Details of all the interview participants can be found in Appendix A, with transcripts of each interview in Appendix B.

You will, almost inevitably, find that you need to include some slight discussion of your results during this section. This discussion should evaluate the quality of the results and their reliability, but not stray too far into discussion of how far your results support your hypothesis and/or answer your research questions, as that is for the discussion section.

See our pages: Analysing Qualitative Data and Simple Statistical Analysis for more information on analysing your results.

Discussion Section

This section has four purposes, it should:

- Interpret and explain your results

- Answer your research question

- Justify your approach

- Critically evaluate your study

The discussion section therefore needs to review your findings in the context of the literature and the existing knowledge about the subject.

You also need to demonstrate that you understand the limitations of your research and the implications of your findings for policy and practice. This section should be written in the present tense.

The Discussion section needs to follow from your results and relate back to your literature review . Make sure that everything you discuss is covered in the results section.

Some universities require a separate section on recommendations for policy and practice and/or for future research, while others allow you to include this in your discussion, so check the guidelines carefully.

Starting the Task

Most people are likely to write this section best by preparing an outline, setting out the broad thrust of the argument, and how your results support it.

You may find techniques like mind mapping are helpful in making a first outline; check out our page: Creative Thinking for some ideas about how to think through your ideas. You should start by referring back to your research questions, discuss your results, then set them into the context of the literature, and then into broader theory.

This is likely to be one of the longest sections of your dissertation, and it’s a good idea to break it down into chunks with sub-headings to help your reader to navigate through the detail.

Fleshing Out the Detail

Once you have your outline in front of you, you can start to map out how your results fit into the outline.

This will help you to see whether your results are over-focused in one area, which is why writing up your research as you go along can be a helpful process. For each theme or area, you should discuss how the results help to answer your research question, and whether the results are consistent with your expectations and the literature.

The Importance of Understanding Differences

If your results are controversial and/or unexpected, you should set them fully in context and explain why you think that you obtained them.

Your explanations may include issues such as a non-representative sample for convenience purposes, a response rate skewed towards those with a particular experience, or your own involvement as a participant for sociological research.

You do not need to be apologetic about these, because you made a choice about them, which you should have justified in the methodology section. However, you do need to evaluate your own results against others’ findings, especially if they are different. A full understanding of the limitations of your research is part of a good discussion section.

At this stage, you may want to revisit your literature review, unless you submitted it as a separate submission earlier, and revise it to draw out those studies which have proven more relevant.

Conclude by summarising the implications of your findings in brief, and explain why they are important for researchers and in practice, and provide some suggestions for further work.

You may also wish to make some recommendations for practice. As before, this may be a separate section, or included in your discussion.

The results and discussion, including conclusion and recommendations, are probably the most substantial sections of your dissertation. Once completed, you can begin to relax slightly: you are on to the last stages of writing!

Continue to: Dissertation: Conclusion and Extras Writing your Methodology

See also: Writing a Literature Review Writing a Research Proposal Academic Referencing What Is the Importance of Using a Plagiarism Checker to Check Your Thesis?

- Dissertation & Thesis Guides

- Basics of Dissertation & Thesis Writing

- How to Write a Results Section for a Dissertation or Research Paper: Guide & Examples

- Speech Topics

- Basics of Essay Writing

- Essay Topics

- Other Essays

- Main Academic Essays

- Research Paper Topics

- Basics of Research Paper Writing

- Miscellaneous

- Chicago/ Turabian

- Data & Statistics

- Methodology

- Admission Writing Tips

- Admission Advice

- Other Guides

- Student Life

- Studying Tips

- Understanding Plagiarism

- Academic Writing Tips

- Essay Guides

- Research Paper Guides

- Formatting Guides

- Basics of Research Process

- Admission Guides

How to Write a Results Section for a Dissertation or Research Paper: Guide & Examples

Table of contents

Use our free Readability checker

A results section is a crucial part of a research paper or dissertation, where you analyze your major findings. This section goes beyond simply presenting study outcomes. You should also include a comprehensive statistical analysis and interpret the collected data in detail.

Without dissertation research results, it is impossible to imagine a scientific work. Your task here is to present your study findings. What are qualitative or quantitative indicators? How to use tables and diagrams? How to describe data? Our article answers all these questions and many more. So, read further to discover how to analyze and describe your research indexes or contact or professionals for dissertation help from StudyCrumb.

What Is a Results Section of Dissertation?

The results section of a dissertation is a data statement from your research. Here you should present the main findings of your study to your readers. This section aims to show information objectively, systematically, concisely. It is allowed using text supplemented with illustrations. In general, this section's length is not limited but should include all necessary data. Interpretations or conclusions should not be included in this section. Therefore, in theory, this is one of your shortest sections. But it can also be one of the most challenging sections. The introduction presents a research topic and answers the question "why?". The Methods section explains the data collection process and answers "how?". Meanwhile, the result section shows actual data gained from experiments and tells "what?" Thus, this part plays a critical role in highlighting study's relevance. This chapter gives reader study relevance with novelty. So, you should figure out how to write it correctly. Here are main tasks that you should keep in mind while writing:

- Results answer the question "What was found in your research?"

- Results contain only your study's outcome. They do not include comments or interpretations.

- Results must always be presented accurately & objectively.

- Tables & figures are used to draw readers' attention. But the same data should never be presented in the form of a table and a figure. Don't repeat anything from a table also in text.

Dissertation: Results vs Discussion vs Conclusion

Results and discussion sections of a dissertation are often confused among researchers. Sometimes both these parts are mixed up with a conclusion for thesis . Figured out what is covered in each of these important chapters. Your readers should see that you notice how different they are. A clear understanding of differences will help you write your dissertation more effectively. 5 differences between Results VS Discussion VS Conclusion:

Wanna figure out the actual difference between discussion vs conclusion? Check out our helpful articles about Dissertation Discussion or Dissertation Conclusion.

Present Your Findings When Writing Results Section of Dissertation

Now it's time to understand how to arrange the results section of the dissertation. First, present most general findings, then narrow it down to a more specific one. Describe both qualitative & quantitative results. For example, imagine you are comparing the behavior of hamsters and mice. First, say a few words about the behavioral type of mammals that you studied. Then, mention rodents in general. At end, describe specific species of animals you carried out an experiment on.

Qualitative Results Section in Dissertation

In your dissertation results section, qualitative data may not be directly related to specific sub-questions or hypotheses. You can structure this chapter around main issues that arise when analyzing data. For each question, make a general observation of what data show. For example, you may recall recurring agreements or differences, patterns, trends. Personal answers are the basis of your research. Clarify and support these views with direct quotes. Add more information to the thesis appendix if it's needed.

Quantitative Results Section in a Dissertation

The easiest way to write a quantitative dissertation results section is to build it around a sub-question or hypothesis of your research. For each subquery, provide relevant results and include statistical analysis . Then briefly evaluate importance & reliability. Notice how each result relates to the problem or whether it supports the hypothesis. Focus on key trends, differences, and relationships between data. But don't speculate about their meaning or consequences. This should be put in the discussion vs conclusion section. Suppose your results are not directly related to answering your questions. Maybe there is additional information that helps readers understand how you collect data. In that case, you can include them in the appendix. It is often helpful to include visual elements such as graphs, charts, and tables. But only if they accurately support your results and add value.

Tables and Figures in Results Section in Dissertation

We recommend you use tables or figures in the dissertation results section correctly. Such interpretation can effectively present complex data concisely and visually. It allows readers to quickly gain a statistical overview. On the contrary, poorly designed graphs can confuse readers. That will reduce the effectiveness of your article. Here are our recommendations that help you understand how to use tables and figures:

- Make sure tables and figures are self-explanatory. Sometimes, your readers may look at tables and figures before reading the entire text. So they should make sense as separate elements.

- Do not repeat the content of tables and figures in text. Text can be used to highlight key points from tables and figures. But do not repeat every element.

- Make sure that values or information in tables and text are consistent. Make sure that abbreviations, group names, interpretations are the same as in text.

- Use clear, informative titles for tables and figures. Do not leave any table or figure without a title or legend. Otherwise, readers will not be able to understand data's meaning. Also, make sure column names, labels, figures are understandable.

- Check accuracy of data presented in tables and figures. Always double-check tables and figures to make sure numbers converge.

- Tables should not contain redundant information. Make sure tables in the article are not too crowded. If you need to provide extensive data, use Appendixes.

- Make sure images are clear. Make sure images and all parts of drawings are precise. Lettering should be in a standard font and legible against the background of the picture.

- Ask for permission to use illustrations. If you use illustrations, be sure to ask copyright holders and indicate them.

Tips on How to Write a Results Section

We have prepared several tips on how to write the results section of the dissertation! Present data collected during study objectively, logically, and concisely. Highlight most important results and organize them into specific sections. It is an excellent way to show that you have covered all the descriptive information you need. Correct usage of visual elements effectively helps your readers with understanding. So, follow main 3 rules for writing this part:

- State only actual results. Leave explanations and comments for Discussion.

- Use text, tables, and pictures to orderly highlight key results.

- Make sure that contents of tables and figures are not repeated in text.

In case you have questions about a conceptual framework in research , you will find a blog dedicated to this issue in our database.

What to Avoid When Writing the Results Section of a Dissertation

Here we will discuss how NOT to write the results section of a dissertation. Or simply, what points to avoid:

- Do not make your research too complicated. Your paper, tables, and graphs should be clearly marked and follow order. So that they can exist independently without further explanation.

- Do not include raw data. Remember, you are summarizing relevant results, not reporting them in detail. This chapter should briefly summarize your findings. Avoid complete introduction to each number and calculation.

- Do not contradict errors or false results. Explain these errors and contradictions in conclusions. This often happens when different research methods have been used.

- Do not write a conclusion or discussion. Instead, this part should contain summaries of findings.

- Do not tend to include explanations and inferences from results. Such an approach can make this chapter subjective, unclear, and confusing to the reader.

- Do not forget about novelty. Its lack is one of the main reasons for the paper's rejection.

Dissertation Results Section Example

Let's take a look at some good results section of dissertation examples. Remember that this part shows fundamental research you've done in detail. So, it has to be clear and concise, as you can see in the sample.

Final Thoughts on Writing Results Section of Dissertation

When writing a results section of a dissertation, highlight your achievements by data. The main chapter's task is to convince the reader of conclusions' validity of your research. You should not overload text with too detailed information. Never use words whose meanings you do not understand. Also, oversimplification may seem unconvincing for readers. But on the other hand, writing this part can even be fun. You can directly see your study results, which you'll interpret later. So keep going, and we wish you courage!

Writing any academic paper is long and thorough work. But StudyCrumb got you back! Our professional writers will deliver any type of work quickly and excellently!

Joe Eckel is an expert on Dissertations writing. He makes sure that each student gets precious insights on composing A-grade academic writing.

Writing the Dissertation - Guides for Success: The Results and Discussion

- Writing the Dissertation Homepage

- Overview and Planning

- The Literature Review

- The Methodology

- The Results and Discussion

- The Conclusion

- The Abstract

- The Difference

- What to Avoid

Overview of writing the results and discussion

The results and discussion follow on from the methods or methodology chapter of the dissertation. This creates a natural transition from how you designed your study, to what your study reveals, highlighting your own contribution to the research area.

Disciplinary differences

Please note: this guide is not specific to any one discipline. The results and discussion can vary depending on the nature of the research and the expectations of the school or department, so please adapt the following advice to meet the demands of your project and department. Consult your supervisor for further guidance; you can also peruse our Writing Across Subjects guide .

Guide contents

As part of the Writing the Dissertation series, this guide covers the most common conventions of the results and discussion chapters, giving you the necessary knowledge, tips and guidance needed to impress your markers! The sections are organised as follows:

- The Difference - Breaks down the distinctions between the results and discussion chapters.

- Results - Provides a walk-through of common characteristics of the results chapter.

- Discussion - Provides a walk-through of how to approach writing your discussion chapter, including structure.

- What to Avoid - Covers a few frequent mistakes you'll want to...avoid!

- FAQs - Guidance on first- vs. third-person, limitations and more.

- Checklist - Includes a summary of key points and a self-evaluation checklist.

Training and tools

- The Academic Skills team has recorded a Writing the Dissertation workshop series to help you with each section of a standard dissertation, including a video on writing the results and discussion (embedded below).

- The dissertation planner tool can help you think through the timeline for planning, research, drafting and editing.

- iSolutions offers training and a Word template to help you digitally format and structure your dissertation.

Introduction

The results of your study are often followed by a separate chapter of discussion. This is certainly the case with scientific writing. Some dissertations, however, might incorporate both the results and discussion in one chapter. This depends on the nature of your dissertation and the conventions within your school or department. Always follow the guidelines given to you and ask your supervisor for further guidance.

As part of the Writing the Dissertation series, this guide covers the essentials of writing your results and discussion, giving you the necesary knowledge, tips and guidance needed to leave a positive impression on your markers! This guide covers the results and discussion as separate – although interrelated – chapters, as you'll see in the next two tabs. However, you can easily adapt the guidance to suit one single chapter – keep an eye out for some hints on how to do this throughout the guide.

Results or discussion - what's the difference?

To understand what the results and discussion sections are about, we need to clearly define the difference between the two.

The results should provide a clear account of the findings . This is written in a dry and direct manner, simply highlighting the findings as they appear once processed. It’s expected to have tables and graphics, where relevant, to contextualise and illustrate the data.

Rather than simply stating the findings of the study, the discussion interprets the findings to offer a more nuanced understanding of the research. The discussion is similar to the second half of the conclusion because it’s where you consider and formulate a response to the question, ‘what do we now know that we didn’t before?’ (see our Writing the Conclusion guide for more). The discussion achieves this by answering the research questions and responding to any hypotheses proposed. With this in mind, the discussion should be the most insightful chapter or section of your dissertation because it provides the most original insight.

Across the next two tabs of this guide, we will look at the results and discussion chapters separately in more detail.

Writing the results

The results chapter should provide a direct and factual account of the data collected without any interpretation or interrogation of the findings. As this might suggest, the results chapter can be slightly monotonous, particularly for quantitative data. Nevertheless, it’s crucial that you present your results in a clear and direct manner as it provides the necessary detail for your subsequent discussion.

Note: If you’re writing your results and discussion as one chapter, then you can either:

1) write them as distinctly separate sections in the same chapter, with the discussion following on from the results, or...

2) integrate the two throughout by presenting a subset of the results and then discussing that subset in further detail.

Next, we'll explore some of the most important factors to consider when writing your results chapter.

How you structure your results chapter depends on the design and purpose of your study. Here are some possible options for structuring your results chapter (adapted from Glatthorn and Joyner, 2005):

- Chronological – depending on the nature of the study, it might be important to present your results in order of how you collected the data, such as a pretest-posttest design.

- Research method – if you’ve used a mixed-methods approach, you could isolate each research method and instrument employed in the study.

- Research question and/or hypotheses – you could structure your results around your research questions and/or hypotheses, providing you have more than one. However, keep in mind that the results on their own don’t necessarily answer the questions or respond to the hypotheses in a definitive manner. You need to interpret the findings in the discussion chapter to gain a more rounded understanding.

- Variable – you could isolate each variable in your study (where relevant) and specify how and whether the results changed.

Tables and figures

For your results, you are expected to convert your data into tables and figures, particularly when dealing with quantitative data. Making use of tables and figures is a way of contextualising your results within the study. It also helps to visually reinforce your written account of the data. However, make sure you’re only using tables and figures to supplement , rather than replace, your written account of the results (see the 'What to avoid' tab for more on this).

Figures and tables need to be numbered in order of when they appear in the dissertation, and they should be capitalised. You also need to make direct reference to them in the text, which you can do (with some variation) in one of the following ways:

Figure 1 shows…

The results of the test (see Figure 1) demonstrate…

The actual figures and tables themselves also need to be accompanied by a caption that briefly outlines what is displayed. For example:

Table 1. Variables of the regression model

Table captions normally appear above the table, whilst figures or other such graphical forms appear below, although it’s worth confirming this with your supervisor as the formatting can change depending on the school or discipline. The style guide used for writing in your subject area (e.g., Harvard, MLA, APA, OSCOLA) often dictates correct formatting of tables, graphs and figures, so have a look at your style guide for additional support.

Using quotations

If your qualitative data comes from interviews and focus groups, your data will largely consist of quotations from participants. When presenting this data, you should identify and group the most common and interesting responses and then quote two or three relevant examples to illustrate this point. Here’s a brief example from a qualitative study on the habits of online food shoppers:

Regardless of whether or not participants regularly engage in online food shopping, all but two respondents commented, in some form, on the convenience of online food shopping:

"It’s about convenience for me. I’m at work all week and the weekend doesn’t allow much time for food shopping, so knowing it can be ordered and then delivered in 24 hours is great for me” (Participant A).

"It fits around my schedule, which is important for me and my family” (Participant D).

"In the past, I’ve always gone food shopping after work, which has always been a hassle. Online food shopping, however, frees up some of my time” (Participant E).

As shown in this example, each quotation is attributed to a particular participant, although their anonymity is protected. The details used to identify participants can depend on the relevance of certain factors to the research. For instance, age or gender could be included.

Writing the discussion

The discussion chapter is where “you critically examine your own results in the light of the previous state of the subject as outlined in the background, and make judgments as to what has been learnt in your work” (Evans et al., 2014: 12). Whilst the results chapter is strictly factual, reporting on the data on a surface level, the discussion is rooted in analysis and interpretation , allowing you and your reader to delve beneath the surface.

Next, we will review some of the most important factors to consider when writing your discussion chapter.

Like the results, there is no single way to structure your discussion chapter. As always, it depends on the nature of your dissertation and whether you’re dealing with qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods research. It’s good to be consistent with the results chapter, so you could structure your discussion chapter, where possible, in the same way as your results.

When it comes to structure, it’s particularly important that you guide your reader through the various points, subtopics or themes of your discussion. You should do this by structuring sections of your discussion, which might incorporate three or four paragraphs around the same theme or issue, in a three-part way that mirrors the typical three-part essay structure of introduction, main body and conclusion.

Figure 1: The three-part cycle that embodies a typical essay structure and reflects how you structure themes or subtopics in your discussion.

This is your topic sentence where you clearly state the focus of this paragraph/section. It’s often a fairly short, declarative statement in order to grab the reader’s attention, and it should be clearly related to your research purpose, such as responding to a research question.

This constitutes your analysis where you explore the theme or focus, outlined in the topic sentence, in further detail by interrogating why this particular theme or finding emerged and the significance of this data. This is also where you bring in the relevant secondary literature.

This is the evaluative stage of the cycle where you explicitly return back to the topic sentence and tell the reader what this means in terms of answering the relevant research question and establishing new knowledge. It could be a single sentence, or a short paragraph, and it doesn’t strictly need to appear at the end of every section or theme. Instead, some prefer to bring the main themes together towards the end of the discussion in a single paragraph or two. Either way, it’s imperative that you evaluate the significance of your discussion and tell the reader what this means.

A note on the three-part structure

This is often how you’re taught to construct a paragraph, but the themes and ideas you engage with at dissertation level are going to extend beyond the confines of a short paragraph. Therefore, this is a structure to guide how you write about particular themes or patterns in your discussion. Think of this structure like a cycle that you can engage in its smallest form to shape a paragraph; in a slightly larger form to shape a subsection of a chapter; and in its largest form to shape the entire chapter. You can 'level up' the same basic structure to accommodate a deeper breadth of thinking and critical engagement.

Using secondary literature

Your discussion chapter should return to the relevant literature (previously identified in your literature review ) in order to contextualise and deepen your reader’s understanding of the findings. This might help to strengthen your findings, or you might find contradictory evidence that serves to counter your results. In the case of the latter, it’s important that you consider why this might be and the implications for this. It’s through your incorporation of secondary literature that you can consider the question, ‘What do we now know that we didn’t before?’

Limitations

You may have included a limitations section in your methodology chapter (see our Writing the Methodology guide ), but it’s also common to have one in your discussion chapter. The difference here is that your limitations are directly associated with your results and the capacity to interpret and analyse those results.

Think of it this way: the limitations in your methodology refer to the issues identified before conducting the research, whilst the limitations in your discussion refer to the issues that emerged after conducting the research. For example, you might only be able to identify a limitation about the external validity or generalisability of your research once you have processed and analysed the data. Try not to overstress the limitations of your work – doing so can undermine the work you’ve done – and try to contextualise them, perhaps by relating them to certain limitations of other studies.

Recommendations

It’s often good to follow your limitations with some recommendations for future research. This creates a neat linearity from what didn’t work, or what could be improved, to how other researchers could address these issues in the future. This helps to reposition your limitations in a positive way by offering an action-oriented response. Try to limit the amount of recommendations you discuss – too many can bring the end of your discussion to a rather negative end as you’re ultimately focusing on what should be done, rather than what you have done. You also don’t need to repeat the recommendations in your conclusion if you’ve included them here.

What to avoid

This portion of the guide will cover some common missteps you should try to avoid in writing your results and discussion.

Over-reliance on tables and figures

It’s very common to produce visual representations of data, such as graphs and tables, and to use these representations in your results chapter. However, the use of these figures should not entirely replace your written account of the data. You don’t need to specify every detail in the data set, but you should provide some written account of what the data shows, drawing your reader’s attention to the most important elements of the data. The figures should support your account and help to contextualise your results. Simply stating, ‘look at Table 1’, without any further detail is not sufficient. Writers often try to do this as a way of saving words, but your markers will know!

Ignoring unexpected or contradictory data

Research can be a complex process with ups and downs, surprises and anomalies. Don’t be tempted to ignore any data that doesn’t meet your expectations, or that perhaps you’re struggling to explain. Failing to report on data for these, and other such reasons, is a problem because it undermines your credibility as a researcher, which inevitably undermines your research in the process. You have to do your best to provide some reason to such data. For instance, there might be some methodological reason behind a particular trend in the data.

Including raw data

You don’t need to include any raw data in your results chapter – raw data meaning unprocessed data that hasn’t undergone any calculations or other such refinement. This can overwhelm your reader and obscure the clarity of the research. You can include raw data in an appendix, providing you feel it’s necessary.

Presenting new results in the discussion

You shouldn’t be stating original findings for the first time in the discussion chapter. The findings of your study should first appear in your results before elaborating on them in the discussion.

Overstressing the significance of your research

It’s important that you clarify what your research demonstrates so you can highlight your own contribution to the research field. However, don’t overstress or inflate the significance of your results. It’s always difficult to provide definitive answers in academic research, especially with qualitative data. You should be confident and authoritative where possible, but don’t claim to reach the absolute truth when perhaps other conclusions could be reached. Where necessary, you should use hedging (see definition) to slightly soften the tone and register of your language.

Definition: Hedging refers to 'the act of expressing your attitude or ideas in tentative or cautious ways' (Singh and Lukkarila, 2017: 101). It’s mostly achieved through a number of verbs or adverbs, such as ‘suggest’ or ‘seemingly.’

Q: What’s the difference between the results and discussion?

A: The results chapter is a factual account of the data collected, whilst the discussion considers the implications of these findings by relating them to relevant literature and answering your research question(s). See the tab 'The Differences' in this guide for more detail.

Q: Should the discussion include recommendations for future research?

A: Your dissertation should include some recommendations for future research, but it can vary where it appears. Recommendations are often featured towards the end of the discussion chapter, but they also regularly appear in the conclusion chapter (see our Writing the Conclusion guide for more). It simply depends on your dissertation and the conventions of your school or department. It’s worth consulting any specific guidance that you’ve been given, or asking your supervisor directly.

Q: Should the discussion include the limitations of the study?

A: Like the answer above, you should engage with the limitations of your study, but it might appear in the discussion of some dissertations, or the conclusion of others. Consider the narrative flow and whether it makes sense to include the limitations in your discussion chapter, or your conclusion. You should also consult any discipline-specific guidance you’ve been given, or ask your supervisor for more. Be mindful that this is slightly different to the limitations outlined in the methodology or methods chapter (see our Writing the Methodology guide vs. the 'Discussion' tab of this guide).

Q: Should the results and discussion be in the first-person or third?

A: It’s important to be consistent , so you should use whatever you’ve been using throughout your dissertation. Third-person is more commonly accepted, but certain disciplines are happy with the use of first-person. Just remember that the first-person pronoun can be a distracting, but powerful device, so use it sparingly. Consult your lecturer for discipline-specific guidance.

Q: Is there a difference between the discussion and the conclusion of a dissertation?

A: Yes, there is a difference. The discussion chapter is a detailed consideration of how your findings answer your research questions. This includes the use of secondary literature to help contextualise your discussion. Rather than considering the findings in detail, the conclusion briefly summarises and synthesises the main findings of your study before bringing the dissertation to a close. Both are similar, particularly in the way they ‘broaden out’ to consider the wider implications of the research. They are, however, their own distinct chapters, unless otherwise stated by your supervisor.

The results and discussion chapters (or chapter) constitute a large part of your dissertation as it’s here where your original contribution is foregrounded and discussed in detail. Remember, the results chapter simply reports on the data collected, whilst the discussion is where you consider your research questions and/or hypothesis in more detail by interpreting and interrogating the data. You can integrate both into a single chapter and weave the interpretation of your findings throughout the chapter, although it’s common for both the results and discussion to appear as separate chapters. Consult your supervisor for further guidance.

Here’s a final checklist for writing your results and discussion. Remember that not all of these points will be relevant for you, so make sure you cover whatever’s appropriate for your dissertation. The asterisk (*) indicates any content that might not be relevant for your dissertation. To download a copy of the checklist to save and edit, please use the Word document, below.

- Results and discussion self-evaluation checklist

- << Previous: The Methodology

- Next: The Conclusion >>

- Last Updated: Apr 19, 2024 12:38 PM

- URL: https://library.soton.ac.uk/writing_the_dissertation

Frequently asked questions

What goes in the results section of a dissertation.

The results chapter of a thesis or dissertation presents your research results concisely and objectively.

In quantitative research , for each question or hypothesis , state:

- The type of analysis used

- Relevant results in the form of descriptive and inferential statistics

- Whether or not the alternative hypothesis was supported

In qualitative research , for each question or theme, describe:

- Recurring patterns

- Significant or representative individual responses

- Relevant quotations from the data

Don’t interpret or speculate in the results chapter.

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Chat with us

- Email [email protected]

- Call +44 (0)20 3917 4242

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Our support team is here to help you daily via chat, WhatsApp, email, or phone between 9:00 a.m. to 11:00 p.m. CET.

Our APA experts default to APA 7 for editing and formatting. For the Citation Editing Service you are able to choose between APA 6 and 7.

Yes, if your document is longer than 20,000 words, you will get a sample of approximately 2,000 words. This sample edit gives you a first impression of the editor’s editing style and a chance to ask questions and give feedback.

How does the sample edit work?

You will receive the sample edit within 24 hours after placing your order. You then have 24 hours to let us know if you’re happy with the sample or if there’s something you would like the editor to do differently.

Read more about how the sample edit works

Yes, you can upload your document in sections.

We try our best to ensure that the same editor checks all the different sections of your document. When you upload a new file, our system recognizes you as a returning customer, and we immediately contact the editor who helped you before.

However, we cannot guarantee that the same editor will be available. Your chances are higher if

- You send us your text as soon as possible and

- You can be flexible about the deadline.

Please note that the shorter your deadline is, the lower the chance that your previous editor is not available.

If your previous editor isn’t available, then we will inform you immediately and look for another qualified editor. Fear not! Every Scribbr editor follows the Scribbr Improvement Model and will deliver high-quality work.

Yes, our editors also work during the weekends and holidays.

Because we have many editors available, we can check your document 24 hours per day and 7 days per week, all year round.

If you choose a 72 hour deadline and upload your document on a Thursday evening, you’ll have your thesis back by Sunday evening!

Yes! Our editors are all native speakers, and they have lots of experience editing texts written by ESL students. They will make sure your grammar is perfect and point out any sentences that are difficult to understand. They’ll also notice your most common mistakes, and give you personal feedback to improve your writing in English.

Every Scribbr order comes with our award-winning Proofreading & Editing service , which combines two important stages of the revision process.

For a more comprehensive edit, you can add a Structure Check or Clarity Check to your order. With these building blocks, you can customize the kind of feedback you receive.

You might be familiar with a different set of editing terms. To help you understand what you can expect at Scribbr, we created this table:

View an example

When you place an order, you can specify your field of study and we’ll match you with an editor who has familiarity with this area.

However, our editors are language specialists, not academic experts in your field. Your editor’s job is not to comment on the content of your dissertation, but to improve your language and help you express your ideas as clearly and fluently as possible.

This means that your editor will understand your text well enough to give feedback on its clarity, logic and structure, but not on the accuracy or originality of its content.

Good academic writing should be understandable to a non-expert reader, and we believe that academic editing is a discipline in itself. The research, ideas and arguments are all yours – we’re here to make sure they shine!

After your document has been edited, you will receive an email with a link to download the document.

The editor has made changes to your document using ‘Track Changes’ in Word. This means that you only have to accept or ignore the changes that are made in the text one by one.

It is also possible to accept all changes at once. However, we strongly advise you not to do so for the following reasons:

- You can learn a lot by looking at the mistakes you made.

- The editors don’t only change the text – they also place comments when sentences or sometimes even entire paragraphs are unclear. You should read through these comments and take into account your editor’s tips and suggestions.

- With a final read-through, you can make sure you’re 100% happy with your text before you submit!

You choose the turnaround time when ordering. We can return your dissertation within 24 hours , 3 days or 1 week . These timescales include weekends and holidays. As soon as you’ve paid, the deadline is set, and we guarantee to meet it! We’ll notify you by text and email when your editor has completed the job.

Very large orders might not be possible to complete in 24 hours. On average, our editors can complete around 13,000 words in a day while maintaining our high quality standards. If your order is longer than this and urgent, contact us to discuss possibilities.

Always leave yourself enough time to check through the document and accept the changes before your submission deadline.

Scribbr is specialised in editing study related documents. We check:

- Graduation projects

- Dissertations

- Admissions essays

- College essays

- Application essays

- Personal statements

- Process reports

- Reflections

- Internship reports

- Academic papers

- Research proposals

- Prospectuses

Calculate the costs

The fastest turnaround time is 24 hours.

You can upload your document at any time and choose between four deadlines:

At Scribbr, we promise to make every customer 100% happy with the service we offer. Our philosophy: Your complaint is always justified – no denial, no doubts.

Our customer support team is here to find the solution that helps you the most, whether that’s a free new edit or a refund for the service.

Yes, in the order process you can indicate your preference for American, British, or Australian English .

If you don’t choose one, your editor will follow the style of English you currently use. If your editor has any questions about this, we will contact you.

- How it works

How to Write a Dissertation Discussion Chapter – A Quick Guide with Examples

Published by Alvin Nicolas at August 12th, 2021 , Revised On September 20, 2023

Dissertation discussion is the chapter where you explore the relevance, significance, and meanings of your findings – allowing you to showcase your talents in describing and analyzing the results of your study.

Here, you will be expected to demonstrate how your research findings answer the research questions established or test the hypothesis .

The arguments you assert in the dissertation analysis and discussions chapter lay the foundations of your conclusion . It is critically important to discuss the results in a precise manner.

To help you understand how to write a dissertation discussion chapter, here is the list of the main elements of this section so you stay on the right track when writing:

- Summary: Start by providing a summary of your key research findings

- Interpretations: What is the significance of your findings?

- Implications: Why are your findings important to academic and scientific communities, and what purpose would they serve?

- Limitations: When and where will your results have no implications?

- Future Recommendations : Advice for other researchers and scientists who explore the topic further in future.

The dissertation discussion chapter should be carefully drafted to ensure that the results mentioned in your research align with your research question, aims, and objectives.

Considering the importance of this chapter for all students working on their dissertations, we have comprehensive guidelines on how to write a dissertation discussion chapter.

The discussion and conclusion chapters often overlap. Depending on your university, you may be asked to group these two sections in one chapter – Discussion and Conclusion.

In some cases, the results and discussion are put together under the Results and Discussion chapter. Here are some dissertation examples of working out the best structure for your dissertation.

Alternatively, you can look for the required dissertation structure in your handbook or consult your supervisor.

Steps of How to Write Dissertation Discussion Chapter

1. provide a summary of your findings.

Start your discussion by summarising the key findings of your research questions. Avoid repeating the information you have already stated in the previous chapters.

You will be expected to clearly express your interpretation of results to answer the research questions established initially in one or two paragraphs.

Here are some examples of how to present the summary of your findings ;

- “The data suggests that”,

- “The results confirm that”,

- “The analysis indicates that”,

- “The research shows a relationship between”, etc.

2. Interpretations of Results

Your audience will expect you to provide meanings of the results, although they might seem obvious to you. The results and their interpretations should be linked to the research questions so the reader can understand the value your research has added to the literature.

There are many ways of interpreting the data, but your chosen approach to interpreting the data will depend on the type of research involved . Some of the most common strategies employed include;

- Describing how and why you ended up with unexpected findings and explaining their importance in detail

- Relating your findings with previous studies conducted

- Explaining your position with logical arguments when/if any alternative explanations are suggested

- An in-depth discussion around whether or not the findings answered your research questions and successfully tested the hypothesis

Examples of how you can start your interpretation in the Discussion chapter are –

- “Findings of this study contradict those of Allen et al. (2014) that”,

- “Contrary to the hypothesized association,” “Confirming the hypothesis…”,

- “The findings confirm that A is….. even though Allen et al. (2014) and Michael (2012) suggested B was …..”

3. Implications of your Study

What practical and theoretical implications will your study have for other researchers and the scientific community as a whole?

It is vital to relate your results to the knowledge in the existing literature so the readers can establish how your research will contribute to the existing data.

When thinking of the possible consequences of your findings, you should ask yourself these;

- Are your findings in line with previous studies? What contribution did your research make to them?

- Why are your results entirely different from other studies on the same topic?

- Did your findings approve or contradict existing knowledge?

- What are the practical implications of your study?

Remember that as the researcher, you should aim to let your readers know why your study will contribute to the existing literature. Possible ways of starting this particular section are;

- “The findings show that A….. whereas Lee (2017) and John (2013) suggested that B”, “The results of this study completely contradict the claims made in theories”,

- “These results are not in line with the theoretical perspectives”,

- “The statistical analysis provides a new understanding of the relationship between A and B”,

- “Future studies should take into consideration the findings of this study because”

“Improve your work’s language, structure, style, and overall quality. Get help from our experienced dissertation editors to improve the quality of your paper to First Class Standard. Click here to learn more about our Dissertation, Editing, and Improvement Services .

Looking for dissertation help?

Researchprospect to the rescue, then.

We have expert writers on our team who are skilled at helping students with dissertations across various disciplines. Guaranteeing 100% satisfaction!

4. Recognise the Limitations of your Research

Almost every academic research has some limitations. Acknowledging them will only add to your credibility as a scientific researcher.

In addition to the possible human errors, it’s important to take into account other factors that might have influenced the results of your study, including but not limited to unexpected research obstacles, specific methodological choices , and the overall research design.

Avoid mentioning any limitations that may not be relevant to your research aim, but clearly state the limitations that may have affected your results.

For example, if you used a sample size that included a tiny population, you may not generalise your results.

Similarly, obstacles faced in collecting data from the participants can influence the findings of your study. Make a note of all such research limitations , but explain to the reader why your results are still authentic.

- The small sample size limited the generalisability of the results.

- The authenticity of the findings may have been influenced by….

- The obstacles in collecting data resulted in…

- It is beyond the framework of this research…

5. Provide Recommendations for Future Research

The limitations of your research work directly result in future recommendations. However, it should be noted that your recommendations for future research work should include the areas that your own work could not report so other researchers can build on them.

Sometimes the recommendations are a part of the conclusion chapter . Some examples;

- More research is needed to be performed….

The Purpose of Dissertation Discussion Chapter

Remember that the discussion section of a dissertation is the heart of your research because a) it will indicate your stance on the topic of research, and b) it answers the research questions initially established in the Introduction chapter .

Every piece of information you present here will add value to the existing literature within your field of study. How you structured your findings in the preceding chapter will help you determine the best structure for your dissertation discussion section.

For example, it might be logical to structure your analysis/discussions by theme if you chose the pattern in your findings section.

But generally, discussion based on research questions is the more widely used structure in academia because this pattern clearly indicates how you have addressed the aim of your research.

Most UK universities require the supervisor or committee members to comment on the extent to which each research question has been answered. You will be doing them a great favour if you structure your discussion so that each research question is laid out separately.

Irrespective of whether you are writing an essay, dissertation, or chapter of a dissertation , all pieces of writing should start with an introduction .

Once your readers have read through your study results, you might want to highlight the contents of the subsequent discussion as an introduction paragraph (summary of your results – as explained above).

Likewise, the discussion chapter is expected to end with a concluding paragraph – allowing you the opportunity to summarise your interpretations.

The dissertation analysis & discussion chapter is usually very long, so it will make sense to emphasise the critical points in a concluding paragraph so the reader can grasp the essential information. This will also help to make sure the reader understands your analysis.

Also Read: Research Discussion Of Findings

Useful Tips

Presentation of graphs, tables, and figures.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, students spent days creating graphs and charts for their statistical analysis work . Thanks to technology, you can produce even more accurate graphs and figures today in a shorter period.

Using Microsoft Word, STATA, SPSS, Microsoft Excel and other statistical analysis software, we can now draw beautiful-looking figures, tables , and graphs with just a few clicks and make them appear in our document at the desired place. But there are downsides to being too dependent on technology.

Many students make the common mistake of using colours to represent variables when really they have to print their dissertation paper final copy in black and white.

Any colours on graphs and figures will eventually be viewed in the grayscale presentation. Recognizing different shades of grey on the same chart or graph can sometimes be a little confusing.

For example, green and purple appear as pretty much the same shade of grey on a line chat, meaning your chart will become unreadable to the marker.

Another trap you may fall into is the unintentional stuffing of the dissertation chapter with graphs and figures. Even though it is essential to show numbers and statistics, you don’t want to overwhelm your readers with too many.

It may not be necessary to have a graph/table under each sub-heading. Only you can best judge whether or not you need to have a graph/table under a particular sub-heading as the writer.

Relating to Previous Chapters

As a student, it can be challenging to develop your own analysis and discussion of results. One of the excellent discussion chapter requirements is to showcase your ability to relate previous research to your research results.

Avoid repeating the same information over and over. Many students fall into this trap which negatively affects the mark of their overall dissertation paper .