The PhD Experience

- Call for Contributions

Inspiration, motivation and the PhD: What are your 3 reasons?

Ellie Ralph |

When starting your PhD, as a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed student, you are full of motivation and passion for your research. However, we have all probably also been at the point when you have little to no motivation for continuing with your PhD and are contemplating if any of it is really ‘worth it’ anymore. The biggest piece of advice I can give in this circumstance is to remember the reason why you started. To help with this personally, I wrote a list of 3 of the top reasons why I am doing my PhD. I recommend to new PhD students to do this task at the start, but you can do this at any point in your PhD and use it as a tool to refer back to during those low points. Below I share my personal list of reasons, but it may help to spark motivation in others too:

- My Grandpa – As a child, I was not a high-achiever in school and always felt like education wasn’t for me. It wasn’t until I started university and really found my passion that I started to enjoy learning again. Growing up, my Grandpa was always the person to express to me the importance of staying in school and achieving good grades. He always pushed for me to do my best, regardless of the result. In 2020, my Grandpa passed away. In the hospital when he was sick, he would tell the nurses and doctors that I was a professor (I wish!), and always talk of how proud he was of me and my achievements. He was always the first person I would call with any academic-related good news. I still find myself wanting to call him now, but I use this as a motivation tool, and like to think that I am making him proud.

- My travel experience – My area of research mostly impacts people within Lebanon. I have been lucky enough to travel to Lebanon numerous times, for both work and personal travel, and have had direct contact with people that my research may one day impact. There is nothing that compares to travelling to the country your research is about, especially experiencing it in a ‘non-work-related way. I have also had some personal experiences with both Lebanese and Syrian nationals alike in the UK, and the experiences have always relit that spark within me to keep going.

- Impact – This is one area in which I think everyone could add it to their list of 3. We have to remember that no matter how small our impact on the world may be, we are still making one. With your PhD, you are making a contribution to the wider sphere of knowledge. My support worker at university changed my perspective on this – that no matter how small your drop in the ocean may be, it is still a drop that wasn’t there before. Further to this, you don’t truly know the impact of your work, and you may be helping change the lives of people you will never meet.

I hope that sharing my experiences helps you to think of the reasons why you started, which may be the same reasons to keep going. It is normal to go through periods of low motivation and the crisis of ‘what am I doing?!’, but it is important to have a place you can refer back to when you’re feeling this way. Please feel free to share your 3 reasons in the comments below.

Photo by Colton Duke on Unsplash

Ellie Ralph is the Vice Chair for Pubs & Publications. She is a second year PhD student at Keele University in Politics and International Relations, exploring Lebanese local NGO management of the Syrian refugee crisis. You can find her on Twitter here.

Share this post:

April 12, 2021

Uncategorized

inspiration , motivation

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Search this blog

Recent posts.

- Seeking Counselling During the PhD

- Teaching Tutorials: How To Mark Efficiently

- Prioritizing Self-care

- The Dream of Better Nights. Or: Troubled Sleep in Modern Times.

- Teaching Tutorials – How To Make Discussion Flow

Recent Comments

- sacbu on Summer Quiz: What kind of annoying PhD candidate are you?

- Susan Hayward on 18 Online Resources and Apps for PhD Students with Dyslexia

- Javier on My PhD and My ADHD

- timgalsworthy on What to expect when you’re expected to be an expert

- National Rodeo on 18 Online Resources and Apps for PhD Students with Dyslexia

- Comment policy

- Content on Pubs & Publications is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.5 Scotland

© 2024 Pubs and Publications — Powered by WordPress

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, reasons, motives and motivations for completing a phd: a typology of doctoral studies as a quest.

Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education

ISSN : 2398-4686

Article publication date: 16 November 2018

Issue publication date: 16 November 2018

This study aims to examine how PhD students with diverse profiles, intentions and expectations manage to navigate their doctoral paths within the same academic context under similar institutional conditions. Drawing on Giddens’ theory of structuration, this study explores how their primary reasons, motives and motivations for engaging in doctoral studies influence what they perceive as facilitating or constraining to progress, their strategies to face the challenges they encounter and their expectations regarding supervision.

Design/methodology/approach

Using a qualitative design, the analysis was conducted on a data subset from an instrumental case study (Stake, 2013) about PhD students’ persistence and progression. The focus is placed on semi-structured interviews carried out with 36 PhD students from six faculties in humanities and social sciences fields at a large Canadian university.

The analysis reveals three distinct scenarios regarding how these PhD students navigate their doctoral paths: the quest for the self; the intellectual quest; and the professional quest. Depending on their quest type, the nature and intensity of PhD students’ concerns and challenges, as well as their strategies and the support they expected, differed.

Originality/value

This study contributes to the discussion about PhD students’ challenges and persistence by offering a unique portrait of how diverse students’ profiles, intentions and expectations can concretely shape a doctoral experience.

- Higher education

- PhD experience

- Doctoral education

- Doctoral student learning

- Doctoral students

- Doctoral candidates

- Doctoral experience

- Doctoral trajectories

- Higher education environment

Skakni, I. (2018), "Reasons, motives and motivations for completing a PhD: a typology of doctoral studies as a quest", Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education , Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 197-212. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-D-18-00004

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

Tress Academic

#35: PhD motivation running low? Here’s the cure!

December 10, 2019 by Tress Academic

Is it getting harder to be excited about your PhD? Perhaps you struggle to find the enthusiasm to start another work day – especially when nothing seems to be going your way. You might be suffering from one of the most common syndromes among PhD students: a lack of motivation. Although it may feel like your work is coming to standstill, DON’T BE FOOLED! There are many ways to get your motivation to come out of hiding, if you know what caused it disappear in the first place! We’ll help you to understand the causes and the cures for the motivational slumps, so you can stay on track and keep smiling until your PhD is in the bag!

Make no mistake, the PhD is a very demanding period of your life. You’re working on many difficult tasks, always aware that things can go wrong, with supervisors who all have high expectations, and dish out heavy criticism whenever they sense a momentary slip-up. Many different tasks demand your attention at any given moment; like working out your research project, experimenting, analysing data, and apart from all of that, you still must attend your graduate courses, present at conferences, and publish your results! That’s a lot to tackle alongside a high workload. So it comes as no surprise if this adds up to you feeling demotivated every now and then. Rest assured, no PhD student is super motivated and happy all the time. The ups and downs are just a part of the entire PhD process.

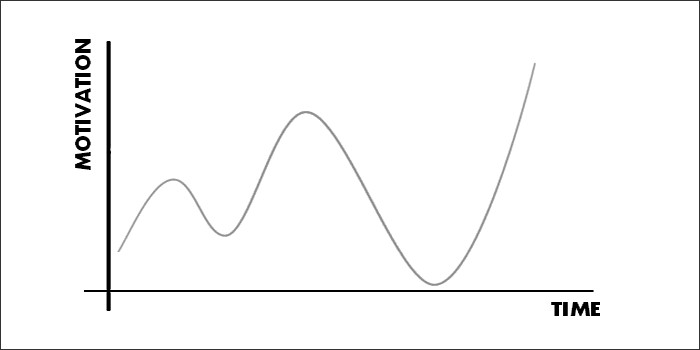

Motivation changes over time

It’s normal that motivational levels of PhD students naturally change over time. We see a lot of PhD students at the very beginning of our course “Completing your PhD successfully on time” that are walking on sunshine in the first weeks of their PhD! When they’re asked to rate their satisfaction with their PhD, they’re close to 100% because they’re just so happy that they got the chance to do a PhD, after receiving a grant or scholarship or successfully beat other competitors for a PhD position, that they feel a bit like they won the lottery!

Was it the same for you in the beginning? Well, then you also know that the feeling does not last. Because after a while, reality kicks in and you realise that not everything is as perfect as it seemed at first. This is often when one’s motivation starts to adjust to a normal level, but is still pretty stable. Later into the PhD, your motivation often continues to shrink. This is when there’s still an awful lot of work to do, with difficulties creeping up all around and no end in sight. But guess what? As the day of your submission approaches (even if it is still in the distant future), motivation often picks up again, once you start to gain confidence with the results of your research, or get your first papers published and a general feeling of – I’ll probably get through this one day – begins to sink in!

Don’t let low motivation drag you down

Apart from this usual fluctuation tendency in a PhD, low motivation is always a warning sign from your psyche telling you ‘uh oh something’s wrong here’ – so don’t ignore it.

It is very important to spot the early signs of low motivation, because at this stage, you can do a lot to get out of it quickly! And the sooner you take the necessary steps to get out of it, the better. In contrast, if you wait too long to act, then you might become really depressed and the situation is much more difficult to tackle.

With this blog post, we want to help you reflect on the reasons you might be feeling de-motivated – as this is often the key for improvement. As we put our heads together, to try and help you understand the problem, we also put together great tips on how to get out of a motivational low – all specific to the underlying reasons! Check out or free worksheet “How to get out of low PhD motivation?” So here’s the message: You don’t have to accept low motivation – it’s all within your power to change!

How to spot low motivation?

These are the typical signs of a PhD student who is at a motivational low:

- You’re not as excited as usual to come to work, or when you think about your PhD.

- It takes you a long time to get started and when you do, you postpone difficult or important tasks related to your project.

- It takes you longer than usual and feels more difficult to finish something. You’re not happy with what you produce and your overall progress slows down.

- You deliberately look for distractions. This might take shape as aimlessly browsing the web or social media platforms (for more on combatting social media addition, see our post #14 “Social media/www distractions at work: 5-step cure!” You might also distract yourself with work-related tasks that are not challenging but still give you the feeling of doing something, e.g. getting involved in the organisation of scientific events at your institute, or busying yourself cleaning up, sorting through emails or reorganising your workspace …

Whatever form it takes, we know that this behaviour always has a root cause. So we’ve broken down for you the five main reasons for low motivation that we see time and time again with PhD students:

Reason 1: Stuck in a boring routine

You may be in a situation where you have to do a tedious or boring task for a considerable amount of time. We know the typical routines: Maybe you are coding and you have nothing to do but coding for whole days, and you know it’ll go on like this for weeks on end. Or you’re spending seemingly endless hours in the lab, running gels, so your day is sliced into 15 or 20 min slots. Or you’re working with antibodies and have 2-3 h incubation times, which is not much better. Or you’re sorting through data to find a few meaningful correlations that will prove your PhD work as worthwhile … It’s no wonder that your motivation plummets and you can hardly pull yourself together to continue the slog.

Probably, you generally like working as a researcher, and most of the tasks come easy to you. But this type of routine would wear anyone down! So your motivation slips with certain repetitive tasks that you don’t like, are boing, or simply overwhelm you.

Reason 2: There’s no end in sight

Your research is in full swing and you thought by now you’d have more clarity and confidence about your project, but instead you are getting more uncertain and confused by the day. You may have some results already, but you are unsure which aspects of it to use for your dissertation, or if you can use them at all. You’ve no clue whether you are making progress with your PhD or not. All you see are loose ends everywhere: ideas that you did not follow up on, half-finished paper-drafts, and incomplete side-projects. It seems like you’ve lost track of it all, you’re going around in circles, with your head spinning, and your motivation is way down.

This type of motivation loss often hits home many months after you started the PhD. Your work gains complexity as you go, and not all results make sense. You may adjust and deviate from your original plan to follow different paths, but not all of them lead to success. Now you are in a phase where you are reading more and understanding better what others in your field did before you. But as you gain knowledge and insights, you also become much more critical of your own work and progress. For you, it feels like there is no clear win or breakthrough in sight that would give you the ‘green light’ so you finally know you’ll be able to manage it all and get your degree in the end.

Reason 3: Unacknowledged work

This has a lot to do with the nature of PhDs and the working culture in scientific institutes: Although you may be part of a team, most of what you do for your PhD in the end is done in isolation. That means you’re probably lacking positive feedback and stimulation. And because you’re still in research training and on a steep learning curve, you get the full brunt of criticism from colleagues. Your supervisors or PIs may be quick to point out any shortcomings or flaws in your work, but less practiced at giving out praise! Have you every heard anyone in your lab saying ‘Wow, you did an absolutely amazing job with this, congrats!’ Nope. This may lead you to think negatively of your own achievements, doubt your abilities, and be quite demotivating!

We have all experienced how this works: If we get positive feedback or a praise, we’re super happy and look forward to continuing with our work or even work harder. But if we are heavily criticised or if critique dominates and nothing positive is mentioned, we are hurt and demotivated. Sometimes this is so extreme that we’d rather stop working on a task and take on something else entirely.

Reason 4: Overworked and sleep deprived

It can happen to anyone: Your recent experiment or field campaign was much more time intensive than expected, there was a deadline for a conference paper that you wanted to submit, and you were also desperate to work on a proposal that would give you more funding for your PhD. As a result, you got into a habit of working very long days, even on weekends, and your last real break was a long time ago …

It’s no surprise that after weeks or months in ‘emergency overdrive’, you feel drained and exhausted. And although you initially thought you’ll just put in some extra hours temporarily, this has in fact become your standard mode of working. You got used to that high-intensity schedule and you had little to no time to recover! Demotivation creeps in, because – after all – you may be a PhD student, but you’re also a human being!

Reason 5: Uncertainty about the future

Do you get a funny feeling in your stomach when you imagine the time after your PhD completed? Do you feel the anxiety creeping up and freezing you to the spot? You’ve probably heard rumours from other PhD students who had difficulty finding a position afterwards and in your worst nightmares you picture yourself unemployed and broke…! So the thought of your ‘life-after-the-PhD’ and all the questions that come along with it are hanging over you, deflating your energy and shrinking your motivation to push ahead with your PhD – because what use is it?

Uncertainty about the future is one of the big recurring worries of PhD students. (Max-Planck survey link). As a PhD student, you have been within a university for such a long time that life beyond the ivory-tower is virtually beyond your imagination. Everything outside academia may seem scary and you have no clue which of your skills will be valued by employers. And even something familiar like continuing with a post-doc seems intangible and remains in the very distant future. Not surprising that your motivation to move on stalled. . .!

How to get out of it?

Help is around. For all these five possible reasons for your motivational low we come up with hands-on advice, tips and suggestions what you can do to overcome the motivational low and get your PhD back on track. Check out our free worksheet “How to get out of low PhD motivation?” for all the help that you need.

Conclusion:

It is normal to lose motivation at critical parts of your PhD. But it is also easy to combat if you recognize the signs early and treat yourself properly. Consider yourself another working part of your project that you may need to adjust as things move forward. You can’t always expect to get your best quality work if you are running on empty. So slow down, take stock, break up your routine now and then with something you love, get input from the people who care about you and rest!

If all our tips sound like we’re speaking a foreign language to you – you need to sit down and plan some changes in your week immediately! This time is always going to be a challenging one, so make it easier for yourself and take a moment of zen to see the past, present and future as part of an amazing journey that you can – no – will successfully finish! Our suggestions in our free worksheet “How to get out of low PhD motivation?” will definitely help you on your way!

Related resources:

- Worksheet “How to get out of low PhD motivation?”

- Smart Academics Blog #14 “Social media/www distractions at work: 5-step cure!”

- Smart Academics Blog #37: 5 ways to boost your energy as a researcher!

- Smart Academics Blog #55: 7 signs you need help with your PhD

- Smart Academics Blog #59: Overwhelmed by PhD work? Here’s the way out!

- Smart Academics Blog #72: 1000 things to do – no clue where to start

- Smart Academics Blog #100: PhD success stories that motivate!

- TRESS ACADEMIC course “Completing your PhD successfully on time”

More information:

Do you want to complete your PhD successfully? If so, please sign up to receive our free guides.

© 2019 Tress Academic

Photograph by Ethan Sykes at unsplash.com

#PhD, #Motivation, #MotivationalLow, #Demotivation, #DoctoralStudy,

How to Write a PhD Motivation Letter

- Applying to a PhD

A PhD motivation letter is a document that describes your personal motivation and competence for a particular research project. It is usually submitted together with your academic CV to provide admissions staff with more information about you as an individual, to help them decide whether or not you are the ideal candidate for a research project.

A motivation letter has many similarities to a cover letter and a personal statement, and institutions will not ask you to submit all of these. However, it is a unique document and you should treat it as such. In the context of supporting a PhD application, the difference is nuanced; all three documents outline your suitability for PhD study. However, compared to a cover letter and personal statement, a motivation letter places more emphasis on your motivation for wanting to pursue the particular PhD position you are applying for.

Academic cover letters are more common in UK universities, while motivation letters are more common abroad.

A motivation letter can play a key part in the application process . It allows the admission committee to review a group of PhD applicants with similar academic backgrounds and select the ideal candidate based on their motivations for applying.

For admission staff, academic qualifications alone are not enough to indicate whether a student will be successful in their doctorate. In this sense, a motivational letter will allow them to judge your passion for the field of study, commitment to research and suitability for the programme, all of which better enables them to evaluate your potential.

How Should I Structure My Motivation Letter?

A strong motivation letter for PhD applications will include:

- A concise introduction stating which programme you are applying for,

- Your academic background and professional work experience,

- Any key skills you possess and what makes you the ideal candidate,

- Your interest and motivation for applying,

- Concluding remarks and thanks.

This is a simplistic breakdown of what can be a very complicated document.

However, writing to the above structure will ensure you keep your letter of motivation concise and relevant to the position you are applying for. Remember, the aim of your letter is to show your enthusiasm and that you’re committed and well suited for the programme.

To help you write a motivation letter for a PhD application, we have outlined what to include in the start, main body, and closing sections.

How to Start a Motivation Letter

Introduction: Start with a brief introduction in which you clearly state your intention to apply for a particular programme. Think of this as describing what the document is to a stranger.

Education: State what you have studied and where. Your higher education will be your most important educational experience, so focus on this. Highlight any relevant modules you undertook as part of your studies that are relevant to the programme you are applying for. You should also mention how your studies have influenced your decision to pursue a PhD project, especially if it is in the same field you are currently applying to.

Work experience: Next summarise your professional work experience. Remember, you will likely be asked to submit your academic CV along with your motivation letter, so keep this section brief to avoid any unnecessary repetition. Include any other relevant experiences, such as teaching roles, non-academic experience, or charity work which demonstrates skills or shows your suitability for the research project and in becoming a PhD student.

Key skills: Outline your key skills. Remember the admissions committee is considering your suitability for the specific programme you are applying for, so mention skills relevant to the PhD course.

Motivation for applying: Show your enthusiasm and passion for the subject, and describe your long-term aspirations. Start with how you first became interested in the field, and how your interest has grown since. You should also mention anything else you have done which helps demonstrate your interest in your proposed research topic, for example:

- Have you attended any workshops or seminars?

- Do you have any research experience?

- Have you taught yourself any aspects of the subject?

- Have you read any literature within the research area?

Finally, describe what has convinced you to dedicate the next 3-4 years (assuming you are to study full time) of your life to research.

How to End a Motivation Letter

Concluding the motivation letter is where most people struggle. Typically, people can easily describe their academic background and why they want to study, but convincing the reader they are the best candidate for the PhD programme is often more challenging.

The concluding remarks of your motivation letter should highlight the impacts of your proposed research, in particular: the new contributions it will make to your field, the benefits it will have on society and how it fits in with your aspirations.

With this, conclude with your career goals. For example, do you want to pursue an academic career or become a researcher for a private organisation? Doing so will show you have put a lot of thought into your decision.

Remember, admissions into a PhD degree is very competitive, and supervisors invest a lot of time into mentoring their students. Therefore, supervisors naturally favour those who show the most dedication. Your conclusion should remind the reader that you are not only passionate about the research project, but that the university will benefit from having you.

Finally, thank the reader for considering your application.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Motivation Letter Format

There are some basic rules to follow when writing a successful motivation letter. These will mimic the standard format for report writing that the supervisor will be familiar with:

- Use a sans serif font (e.g. Arial or Times New Roman),

- Use a standard font size (e.g. 12pt) and black font colour,

- Keep your writing professional throughout and avoid the use of informal language,

- Write in the first person,

- Address your motivation letter to a named person such as the project supervisor, however, this could also be the person in charge of research admissions,

- Structure your letter into paragraphs using the guidance above, such as introduction, academic history, motivation for research, and concluding remarks.

How Long Should a Motivation Letter Be?

A good rule of thumb for PhD motivation letters is to keep it to around one side of A4. A little longer than one page is acceptable, but two pages is generally considered too long. This equates to approximately 400-600 words.

Things to Avoid when Writing Your Motivational Letter

Your motivational letter will only be one of the several documents you’ll be asked to submit as part of your PhD application. You will almost certainly be asked to submit an Academic CV as well. Therefore, be careful not to duplicate any of the information.

It is acceptable to repeat the key points, such as what and where you have studied. However, while your CV should outline your academic background, your motivation letter should bring context to it by explaining why you have studied what you have, and where you hope to go with it. The simplest way to do this is to refer to the information in your CV and explain how it has led you to become interested in research.

Don’t try to include everything. A motivation letter should be short, so focus on the information most relevant to the programme and which best illustrates your passion for it. Remember, the academic committee will need to be critical in order to do their jobs effectively , so they will likely interpret an unnecessarily long letter as in indication that you have poor written skills and cannot communicate effectively.

You must be able to back up all of your statements with evidence, so don’t fabricate experiences or overstate your skills. This isn’t only unethical but is likely to be picked up by your proposed PhD supervisor or the admissions committee.

Whilst it is good to show you have an understanding of the field, don’t try to impress the reader with excessive use of technical terms or abbreviations.

PhD Motivation Letter Samples – A Word of Caution

There are many templates and samples of motivation letters for PhDs available online. A word of caution regarding these – although they can prove to be a great source of inspiration, you should refrain from using them as a template for your own motivation letter.

While there are no rules against them, supervisors will likely have seen a similar letter submitted to them in the past. This will not only prevent your application from standing out, but it will also reflect poorly on you by suggesting that you have put minimal effort into your application.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

How to Stay Motivated During Your PhD Programme

Motivation is a tricky thing. Even if you are committed to your goals, it can be acting as a roller coaster at times due to accumulating stress or losing faith in the result. With PhD thesis writing , such terms as ‘second-year blues’ as well as statistics of academic dropouts and mental health issues strongly suggest that staying on track may be much more difficult than you might think. The best solution here is to understand the existence of motivation problems, accept their inevitability, and plan your journey in a way minimising them. In this article, we will discuss a number of ways to stay motivated during your PhD programme.

1. Start Small

As noted by multiple experts, a PhD programme is a marathon rather than a sprint. If you choose to follow the same mentality used by Undergraduate and Master’s students, this will lead to inevitable burnout down the road. The infamous second-year blues usually occur because practitioners take more obligations than they can possibly meet. Unfortunately, this approach is actively promoted in academia:

- Most supervisors expect you to invest all your spare time and resources into your PhD project.

- Other students discuss the importance of ‘giving it all that you have’ during your first year.

- Everyone is certain that ‘sacrificing something’ is the key to getting good things in life.

Surprisingly, the optimal strategy for staying motivated and productive throughout your PhD programme is the direct opposite of this approach. Do not be mistaken, you will definitely have some ‘crunch’ periods caused by unexpected circumstances while writing your thesis. However, going slow and steady is the best long-term strategy to follow most of the time due to the following reasons:

- Motivation stems from overall satisfaction and good physical and mental health.

- Balancing your work and social life is a good way of achieving this state.

- The duration of your PhD project implies that you will not have time to recuperate.

The last thought is especially important. The length of your PhD project means that you will have to maintain your current productivity levels for several years without any breaks. If you intend to end a marathon successfully, you may choose to not exhaust yourself in the beginning.

2. Be Humble

If you have ever been to a gym, you have probably seen people coming to do some weightlifting exercises for the first time. In many cases, they use too much weight to ‘not look wimpy’. Unfortunately, this decision effectively ruins their technique and future progress. Any personal trainer will tell you to start with the smallest weights possible and add more as you progress. In line with the previous recommendation, this means that your PhD journey should proceed in accordance with the following routine:

- Start with a minimal daily workload and experiment with several daily and weekly schedules.

- Proceed with this arrangement and always maintain a leeway for emergencies.

- Increase your daily/weekly workload if you feel that you can successfully maintain optimal work/life balance with the previous ‘setting’ for several weeks at a time.

While trying to ‘lift as much weight as you can’ may look ‘cool’ at first glance, this is simply not sustainable in a marathon setting. If you feel that you cannot manage your current workload while staying motivated and productive, this is a clear sign that you need to negotiate a more reasonable schedule with your supervisor. No athlete will continue lifting excessive weight after feeling chronic pain in their body. However, many PhD students see this as a viable long-term strategy for avoiding the necessary PhD programme extensions and end up losing more time due to stress accumulation and burnout.

Staying humble can also be compared with speeding up in your car. Most vehicles cannot start running at 100 miles per hour in a single second. You need to start slow and gradually ‘change gears’ while also observing the road situation. In many cases, you simply cannot proceed at the desired speed due to unexpected turns, pedestrians, and other obstacles. Driving slowly is always preferable to crashing your car and making a very long stop in your academic journey as a result.

3. Have a Plan

Progressing in small steps means that you should carefully plan each one of them to maximise your outputs. Motivation stems from measurable and manageable tasks that you complete successfully. Here are some ideas on how you can maintain it:

- Set small and manageable tasks for each day (e.g. reading 5 articles or writing 300 words of your thesis);

- If a task cannot be quantified, set it as ‘working on … for … minutes’;

- Focus on the formal completion of the task rather than specific outputs or deliverables;

- Keep track of your progress over time.

Keeping a diary is a must for staying motivated and productive during your PhD programme. Make sure to record the completion of individual tasks and your overall progress. This allows you to remind yourself about the substantial results you have already achieved in moments of doubt. A lack of such a diary leaves you one-on-one with your fears of underperforming and pushes you into the dreadful ‘sprinter’s mentality’ leading to burnout and academic failures.

Additionally, try to record non-quantifiable tasks as ‘time spent working on it’ instead of results. If you are looking for quality references in a particular field, you have no control over the actual existence of recent peer-reviewed articles in it. Hence, ending an hour of work with no quantitative results should still be recorded as progress and not a failure if you are willing to stay motivated and maintain an internal locus of control.

4. Stay Focused on the Bigger Picture

When you decided to enter a PhD programme, you were motivated by some long-term goals. They could include better employment perspectives, your in-depth interest in a certain field or your willingness to build a career in academia. Losing track of these objectives is one of the main reasons leading to poor productivity and low motivation. While your daily routine is probably filled with smaller tasks as suggested earlier, sticking a printed list of your long-term goals on your fridge may be a good way of reminding yourself why you are doing this in the first place.

In some cases, this ‘bigger picture’ needs to be adjusted over time. The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted many PhD journeys and has substantially decreased the number of positions available in academia. If a certain student saw their long-term goal as a career in this sphere, this inevitably decreases their motivation at the moment. Effectively, their actions and progress are leading them nowhere according to the opinions of multiple experts and practitioners that they read.

If you find yourself involved in a disruptive trend like this one, you may need to make some hard decisions and reconsider your overall direction. The same is true for problems with a certain supervisor or not making progress with your initial topic. Biologically speaking, the loss of motivation is a physiological sign of not achieving your goals and losing interest in them. Reconsidering your objectives can be a better option than ignoring this increasing resistance.

5. Talk with Others

Networking is a powerful instrument for getting relevant information and minimising the amount of wasted effort. Make sure to ask a lot of questions during your meetings with your supervisor. This way, you can clarify their expectations and make sure that all your activities are rewarded with favourable outcomes afterwards. Not getting positive reinforcement for your efforts is a very short road to the loss of motivation.

Similarly, peer communication opens new opportunities for being productive and making better decisions. This can include writing articles with other PhD students, exchanging valuable information about your thesis-writing activities, and sharing your feelings and insights about your academic journeys. In many cases, this knowledge will help you set realistic goals and expectations and avoid a feeling of lagging behind your peers.

A good strategy here is to start up accounts on several popular online PhD forums. As opposed to social media, you can stay more or less anonymous, which protects you from your supervisor or your peers discovering your questions to community members. Such forums usually have hundreds of persons who lived through their PhD programmes and can share their stories or confirm your doubts. This will provide additional ‘reality checks’ for your ambitious plans and help you set realistic goals.

Staying motivated and focused for 3+ years of PhD writing is a challenging task. As stated earlier, some motivation problems in this sphere may stem from incorrect strategic choices made early on. Try to obtain multiple opinions and seek PhD help before you start your PhD programme. This way, you will know that you are working with a promising topic and a high-quality long-term plan for completing your PhD dissertation. If you feel like you are losing your overall direction and your supervisor is not providing sufficient help and support, contacting a reputable PhD writing service may be a good idea to get things under control. They can help ease the workload and help you stay motivated during your PhD programme.

What to do if you lack motivation in your PhD

May 4, 2020

Motivation is elusive. Some days you have it and others you don’t.

What gives?

Well, having fluctuations in your motivation is normal and to be expected. If you took ten PhD students, how many do you think would say that they’re highly motivated all the time? Not many, I imagine.

But it can also seem that motivation becomes harder and harder to find as you go through your PhD. With good reason. Studying for a PhD is an inherently lonely endeavour and the workload is considerable.

On top of that, the day to day routine can soon become boring, and you’re often undervalued, receive little acknowledgement for your expertise and frequently feel overwhelmed. Plus, the further you go on the PhD journey, the more uncertain you become about the quality of your work or where you’ll end up when you finally finish.

If you’re reading this and having trouble finding your own motivation, know that you aren’t alone. It’s okay to not always be highly motivated, and instead recognise that fluctuating motivation is a normal part of the PhD process.

Motivation is something you can control. Given the right tools, you can find motivation when it otherwise is missing. Here, I want to share with you a number of tips you can use to boost your motivation levels.

These tips have been shared by readers of this blog and from my own experience navigating my own PhD and coaching PhD students . Not all may be suitable for you, because everyone works in different ways. Instead, see them as a list you can pick from to suit your current situation.

Know that your lack of motivation is completely solvable. The first step in that process is changing your expectations.

Interested in group workshops, cohort-courses and a free PhD learning & support community?

The team behind The PhD Proofreaders have launched The PhD People, a free learning and community platform for PhD students. Connect, share and learn with other students, and boost your skills with cohort-based workshops and courses.

Stop expecting so much from yourself.

Ask whether you’re expecting too much from yourself. It’s fine to have goals and ambitions, but it’s not fine to expect 100% from yourself all day every day. You’re going to have days when you don’t feel up to the task, or where your heart really isn’t in it. If you expect 100%, these days are a problem. If instead you recognise that you’re human and humans have off days, these days aren’t such a big deal.

Try and lower your expectations for what’s possible within a given day and acknowledge that having a bad day every now and again isn’t the end of the world, it’s just part of the journey.

See the bigger picture

An effective way of managing your expectations is to see the bigger picture. Remind yourself why you started out on your PhD journey in the first place, what motivates you, and what your goal is with the thesis and beyond. Focusing on the bigger picture means you can see each day for what it is: a small component of that bigger objective. Having an off day and periods where you’re not motivated isn’t so important, as it’s just one tiny step in a much longer journey to get you where you want to go.

Focus on what you can control

But what about your daily habits? Have you formed effective daily routines that promote self-care? Do you make sure that your phone is turned off, you’re otherwise free from distraction as much as possible and that your place of work is the kind of place you could actually expect to get some deep concentration going?

Your PhD Thesis. On one page.

Make specific to-do lists.

Take it a step further and control the way you approach your day-to-day tasks. At the start of each day, you need to know clearly what it is you want to accomplish that day.

You need to be specific. Often a lack of motivation stems from not breaking down bigger tasks into smaller, more manageable components. If you wake up, look at your to-do list and all you see is ‘write literature review’, no sane person would be motivated to do that. Instead, if you saw ‘write the literature review introduction’ or ‘write 300 words of the literature review’, you’ve suddenly got something much more manageable on your hands.

On top of that, you’ve got clear, measurable deliverables. If your task is ‘write your literature review’ you aren’t going to finish it in a day so how will you know when you’re done for the day? If you instead write ‘write 300 words of the literature review’, you will know exactly where you stand.

So think to yourself: is this task broken down into small, more manageable components and am I being realistic about how many of those components I can achieve in one day?

Make your work place a place you actually want to work in

Once you’re sure you’ve broken down your tasks into manageable chunks, it’s time to think about how you actually sit down and work.

We’ve talked already about avoiding interruptions by doing things like turning your phone off. Your aim is for big chunks of uninterrupted time in which you can find your flow and focus on the job at hand.

Be realistic about how long you will be able to concentrate. A popular time management technique is the Pomodoro Technique . This simple productivity tool involves you setting a timer for twenty-five minutes, during which there’s no Facebook, no messages, no disruptions of any kind. At the end of that time, you take a five-minute break. You repeat that process four times (for two hours) before taking a longer, thirty-minute break.

Once you finish tasks, don’t just delete them off of your to-do list. Instead, shift them over to a ‘done’ list. That way, you can get a little motivational boost when you see how much you’re accomplishing in any one day. Also, because you’re working to a timer, you may find that you work more quickly because you want to get things wrapped up into neat twenty-five-minute packages.

Work out what’s important and urgent. Then work on that.

Choosing what to focus on in the first place is half the battle when it comes to increasing motivation. You need to bear in mind the distinction between something that is or isn’t important and something that is or isn’t urgent. You can have an urgent task that isn’t important, and an important task that isn’t urgent. Focus on what’s important and urgent first. Don’t waste your time on things that aren’t important and aren’t urgent.

This reflects the fact that 20% of your work is going to produce 80% of your outputs and outcomes in any given day. Spot what that 20% looks like and focus on that, as you’ll get the biggest bang for your buck. Don’t waste your time on the 80% of things that only lead to 20% of the outcomes.

The Eisenhower Matrix can help you understand what it is that is important or urgent and will help you better structure your workflow and to-do list.

Reward successes

Okay, so you’ve cleaned your desk, turned your phone off, set your timer and you’re moving stuff off your to-do lists. Good job. Here’s another important step.

Reward yourself. Life wouldn’t be any fun it is was all work, so be sure to reward yourself when you get things done, particularly if you’re doing things you didn’t particularly want to do in the first place.

There are two ways of doing this. On a day to day level, give yourself credit for getting stuff done. Have a slice of cake, take a long bath, do whatever it is you do to show yourself some love. On the grander scale, celebrate the successes. Each day adds up to the bigger goal you’ve set, so it isn’t enough just to celebrate getting through each day, you need to celebrate when you reach those goals. Get good feedback on a chapter? Celebrate! Got your fieldwork done? Celebrate! You get the idea.

Navigate Shit Valley

Inevitably though you are going to reach a stage where you can’t possibly face doing any more work. Everyone reaches this stage eventually. I call it Shit Valley .

In Shit Valley, everywhere you look is covered in shit and there doesn’t appear to be a way out. This stage normally comes about halfway through a PhD, when you’re about as far from a way out as it’s possible to be. You’re deep into your data, but you’re far away from the end of the tunnel. You still don’t really know what’s going on and you’re riddled with more self-doubt than you’ve ever had. It’s at this stage that motivation becomes a real struggle, as you’re too far invested to give up and too far away from the end to see what comes after.

Because the only way out of Shit Valley is to wade further through it, you need to really step up the techniques you use to foster motivation.

It’s at this stage that investing in your own health becomes particularly important. Resist the urge to eat junk and be lazy. Instead, eat well most of the time, eat junk only occasionally and make sure you’re moving around every day. Find something that suits you. Just move.

It’s also at this stage that having a life outside of your PhD becomes useful. Too many PhD students (myself included) make their PhD their entire life, at the expense of a sensible work-life balance and a healthy distraction away from your thesis. It’s important to cultivate your hobbies (or to find some if you don’t have any) and to maintain a friendship circle that isn’t full of PhD students. Having this external distraction may be the only thing that keeps you sane.

Now is also the time to frequently remind yourself why you are doing what you’re doing. Picture what it’s going to feel like once you’re done, when you’re graduating and when you’re able to move on with your life.

One day you’ll finish, and you’ll look back and be incredibly proud of what you have achieved. That long term perspective is a powerful one, and should make you reflect more kindly on yourself on the days where you’re not so motivated or where you’re not at 100%. Be kind to yourself, particularly when you’re not as motivated as you wish.

But also be proactive. When you’re not motivated, look at your current situation and ask yourself what it is about current arrangements that don’t lend themselves to productivity. What can you change? The advice and tips above are a good start. Explore them, see what works for you and slowly chip away until you start to find the routine and short-cuts that work for you.

Keep doing that and you’ll be calling yourself Doctor in no time.

Hello, Doctor…

Sounds good, doesn’t it? Be able to call yourself Doctor sooner with our five-star rated How to Write A PhD email-course. Learn everything your supervisor should have taught you about planning and completing a PhD.

Now half price. Join hundreds of other students and become a better thesis writer, or your money back.

Share this:

Submit a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Search The PhD Knowledge Base

Most popular articles from the phd knowlege base.

The PhD Knowledge Base Categories

- Your PhD and Covid

- Mastering your theory and literature review chapters

- How to structure and write every chapter of the PhD

- How to stay motivated and productive

- Techniques to improve your writing and fluency

- Advice on maintaining good mental health

- Resources designed for non-native English speakers

- PhD Writing Template

- Explore our back-catalogue of motivational advice

7 Super Simple PhD Student Motivation Hacks

Losing motivation during your PhD is very, after all, you are trying to work towards a single problem for many years. When things are not going your way, or you are just fed up of thinking about the same thing over and over again, you can very quickly lose motivation.

Keeping your motivation up during your PhD means understanding you need to focus on discipline and not necessarily motivation. However, remembering your “why”, eating healthily, and finding an energising hobby can help keep you motivated.

In this article, we will go over all of the things you need to know about keeping up your motivation as a PhD student and all of the things I learned throughout my 15 years in academia.

I was always surprised at how easy it was to get myself back on track if I found myself in a slump.

Check out my YouTube video if you want to know more about how to get your PhD motivation back. I summarised all of the most important and effective tricks:

Here are all of the little tricks you need to know.

It’s about discipline NOT motivation

It’s common to feel demotivated and lose your motivation during your PhD or when writing up your thesis, but there’s a simple fact that every successful person learns.

It’s not about motivation, it’s about discipline.

That’s what successful PhD students and academics understand.

They don’t wait to feel like doing something, they just do it. And they keep doing it, even when they don’t feel like it, because they know it’s important.

Successful PhD students are disciplined. They have the self-control to do what they need to do, even when they don’t want to do it. They know that if they’re not disciplined, they won’t achieve their goals.

Unfortunately, we often wait for too long for motivation to strike. In my experience, a lot of the time, this simply does not happen.

If you want to be successful during your PhD, you need to be disciplined. You need to have the self-control to do what’s necessary, even when you don’t feel like it. You need to keep going, even when you feel like giving up.

Discipline is the key to success in academia.

Sometimes, discipline is not enough on its own. If you are experiencing any of the low motivation symptoms, you can combat them relatively easily.

How to spot low motivation?

There are several ways to spot low motivation.

One way is to ask yourself how much pleasure you get from the activities you’re engaged in. If you’re not enjoying what you’re doing, it’s likely that your motivation is low.

Another way to tell if your motivation is low is to look at how much effort you’re putting into your studies.

If you find yourself procrastinating or not putting forth your best effort, it’s a sign that your motivation may be low.

Finally, take a look at your results. If you’re not seeing the progress you want, or if you’re seeing setbacks, it could be a sign that your motivation is lacking.

There are also some very specific PhD related symptoms that you should look for.

Not wanting to communicate with your supervisor

One of the first warning signs I look for in any of my students is any hesitation in communicating with their supervisors.

Students often avoid speaking with their supervisors if they are not producing results. This can happen when the PhD student feels like there is a massive hurdle in front of them that they cannot overcome.

Your supervisor should be able to help you find a simple experiment or study to do to start the ball rolling.

Never avoid or delay a supervisor meeting. The meetings will keep you accountable and help you on the path to completion.

Procrastination on thesis/writing

Writing is a massive pain in the bum.

I know that I would always procrastinate a lot when it came to writing up my thesis or peer-reviewed papers.

A lot of people find the academic writing process very tedious and painful. Finding the motivation to do just a few hundred words a day can also be very difficult.

Loss of enthusiasm

Burnout During your PhD, it is likely that you will feel overwhelmed and stressed at some point.

Your supervisor may not be able to help either, as they are usually busy with their own research and things.

Research is a notoriously competitive field, which means that there is a lot of pressure to succeed. This can lead to feelings of anxiety and stress, which can eventually lead to burnout.

If you find yourself feeling overwhelmed or burnt out, it is important to take a step back and assess your situation. Talk to your supervisor about your concerns and see if there is anything they can do to help you.

It may also be helpful to talk to other PhD students or academics who have been through the same thing. They will be able to offer advice and support.

In the end, it is up to you to manage your own stress levels and make sure you don’t end up burning out.

If you want to know more about combating burnout during your PhD check out my YouTube video below.

How do PhD students stay motivated?

There is no one answer to this question as different students have different motivators.

However, some ways that PhD students stay motivated include setting goals, breaking up their work into manageable tasks, staying organized, and seeking support from their peers and mentors.

Additionally, many students find it helpful to celebrate their small accomplishments along the way. This will help create a sense of momentum that can breed more motivation.

Here are the basic motivational tips including some simple actionable advice that you can use if you are feeling unmotivated.

Motivational Tips

1. The basics

First, try setting smaller goals that are more achievable. This will help you see progress and feel more successful, which can increase your motivation.

Second, make sure you’re taking care of yourself physically by getting enough sleep and exercise; both things can boost your energy and mood, which can in turn increase your motivation.

Finally, try speaking kindly to yourself and focusing on positive self-talk; this can help increase your confidence and self-belief, making it easier to stay motivated.

2. Remember your WHY

Throughout PhD it can be hard to remember why you actually started one in the first place. There is so much more you end up doing is a PhD student. You can actually forget your true purpose whilst busy with the admin, politics, and busywork that a PhD often presents.

Getting familiar with your motivations to do your PhD will certainly ground you, hopefully, help you remember why you decided to go down this path in the first place.

3. Focus on the bigger picture

Focusing on the bigger picture also helps me a lot.

Quite often we can get bogged down in the details of our research. However, connecting with the bigger picture and zooming out really helps boost motivation.

Remember questions such as:

- who you’re doing this research for

- why you did this in the first place

- what the true benefits of your work are

can really help provide that small amount of inspiration when it is low.

4. Find an energizing hobby

Hobbies have been something that has provided a welcome distraction from my PhD and academic work.

They have allowed me to get away from work and take a break from the daily grind.

However, not all hobbies are made the same.

I would recommend finding a hobby in which you feel energised. Watching TV, reading a book, are great but often leave me feeling tired. Hobbies that include hanging out with other people and being active are often much better for keeping up my motivation and helping me feel energised and ready to tackle the issues by PhD threw up.

5. Eat well

It goes without saying that eating well throughout your PhD will help you feel better in many aspects of your life.

If you’re feeling unmotivated remember to go back to unprocessed and healthy food to kickstart your healthy eating habits again.

Stay away from highly processed foods and junk food – doing so has provided me with a huge boost in energy and therefore motivation.

6. Take time to step away from your work

Step away from your PhD every so often.

Take a moment to reconnect with friends, family and old acquaintances. It is actually okay to take some time for you.

Some PhD students need to step away from their work for much longer. Stepping away from your PhD for six months to a year can also help you regain the motivation you need to finish.

7. Focus on your achievements

In the daily grind of a PhD can be hard to focus on your achievements when all you can see are your failures or challenges.

Nothing motivates me more in my academic career than seeing what I have already achieved and what I can improve on.

Taking a moment to stop and reflect on your achievements will help you fine-tune your next step and will give you the energy to want to reproduce that successful experiment or study.

I like to keep a little list of my achievements nearby so that I can look at them whenever I am feeling flat.

Why Losing Motivation In Grad School Is Normal

Losing motivation in grad school is normal for a number of reasons.

First, the academic pressure can be intense and overwhelming at times.

Second, the process of getting a PhD or postdoc often takes much longer than students expect, which can lead to frustration and disappointment.

Third, many students are juggling multiple responsibilities (e.g., teaching, research, family) and simply don’t have the time or energy to devote to their studies.

Finally, it’s easy to become discouraged when you compare yourself to your peers and feel like you’re not making as much progress as they are.

If you’re feeling unmotivated, it’s important to remember that it’s normal and that you’re not alone.

Talk to your advisor or other trusted faculty member about how you’re feeling and see if they have any advice on how to get back on track.

Take some time for yourself outside of school and do things that make you happy. And finally, remind yourself why you’re doing this in the first place. Grad school is hard work, but it’s also an amazing opportunity to learn and grow as a person.

Wrapping up

This article is covered everything you need to know about keeping up your motivation as a PhD student.

The PhD is long, arduous, and can test even the most motivated of individuals. Focusing on discipline and execution every day will be the number one way you can build up momentum and keep moving forward.

When your willpower is depleted, make sure you are eating well, you take time to reconnect with friends and family and do an energising hobby.

Small steps every single day is what finishes a PhD. Take small steps and the rest of your PhD will follow.

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER COLUMN

- 28 April 2020

Finding motivation while working from home as a PhD student during the coronavirus pandemic

- Melina Papalampropoulou-Tsiridou 0

Melina Papalampropoulou-Tsiridou is a PhD and MBA candidate at Laval University in Quebec City, Canada, and conducts her PhD research in neuroscience at CERVO Brain Research Centre in Quebec City.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

At the moment, staying motivated can be tough. Many scientists have admitted this on social media or in online meetings. I’ve struggled to follow a consistent routine and to be productive, thinking twice about getting dressed in the morning while wondering, “What’s the point?” This is especially true when we’re surrounded by distractions at home — a place usually kept away from work.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01292-x

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged .

Related Articles

- Research management

Brazil’s plummeting graduate enrolments hint at declining interest in academic science careers

Career News 21 MAY 24

How religious scientists balance work and faith

Career Feature 20 MAY 24

How to set up your new lab space

Career Column 20 MAY 24

Guidelines for academics aim to lessen ethical pitfalls in generative-AI use

Nature Index 22 MAY 24

Pay researchers to spot errors in published papers

World View 21 MAY 24

Trials that infected people with common colds can inform today’s COVID-19 challenge trials

Correspondence 21 MAY 24

A global pandemic treaty is in sight: don’t scupper it

Editorial 21 MAY 24

US halts funding to controversial virus-hunting group: what researchers think

News 16 MAY 24

Editor (Structural biology, experimental and/or computational biophysics)

We are looking for an Editor to join Nature Communications, the leading multidisciplinary OA journal, publishing high-quality scientific research.

London or New York - hybrid working model.

Springer Nature Ltd

Wissenschaftliche/r Mitarbeiter/in - Quantencomputing mit gespeicherten Ionen

Wissenschaftliche/r Mitarbeiter/in - Quantencomputing mit gespeicherten Ionen Bereich: Fakultät IV - Naturwissenschaftlich-Technische Fakultät | St...

Siegen, Nordrhein-Westfalen (DE)

Universität Siegen

Wissenschaftliche/r Mitarbeiter/in (PostDoc) - Quantencomputing mit gespeicherten Ionen

Wissenschaftliche/r Mitarbeiter/in (PostDoc) - Quantencomputing mit gespeicherten Ionen Bereich: Fakultät IV - Naturwissenschaftlich-Technische Fak...

Professor Helminthology

Excellent track record on the biology and immunobiology of zoonotic helminths and co-infections, with a strong scientific network.

Antwerp, New York

Institute of Tropical Medicine

Assistant Professor in Plant Biology

The Plant Science Program in the Biological and Environmental Science and Engineering (BESE) Division at King Abdullah University of Science and Te...

Saudi Arabia (SA)

King Abdullah University of Science and Technology

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

The Relationship Between Resilience and Motivation

- First Online: 28 December 2018

Cite this chapter

- Barbara Resnick 4

2797 Accesses

8 Citations

Resilience refers to the capacity to spring back from a physical, emotional, financial, or social challenge and bounce forward. Being resilient indicates that the individual has the human ability to adapt in the face of tragedy, trauma, adversity, hardship, and ongoing significant life stressors. Motivation is different from resilience and is based on an inner urge rather than stimulated in response to adversity or challenge. Motivation refers to the need, drive, or desire to act in a certain way to achieve a certain end. Motivation is, however, related to resilience in that it requires motivation to be resilient. The characteristics of individuals who are motivated and those who are resilient are similar and can be developed over time. This chapter reviews the ways in which these two concepts are similar and different and provides theoretical and empirical support for the evidence that they are both critical to recovery following an acute event and to assure successful aging .

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction—Setting the Scene

Introducing Resilience Outcome Expectations: New Avenues for Resilience Research and Practice

Resilience, Adapting to Change, and Healthy Aging

Albright, C., Pruitt, L., Castro, C., Gonzalez, A., Woo, S., & King, A. (2005). Modifying physical activity in a multiethnic sample of low-income women: One-year results from the IMPACT (Increasing Motivation for Physical ACTivity) project. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 30 (3), 191–200.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

American Psychological Association Help Center. (2004). The road to resilience . Retrieved from http://www.apahelpcenter.org/featuredtopics/feature.php?id6 . Last accessed June, 2013.

Baert, V., Gorus, E., Guldemont, N., De Coster, S., & Bautmans, I. (2015). Physiotherapists’ perceived motivators and barriers for organizing physical activity for older long-term care facility residents. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 16 (5), 371–379.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Google Scholar

Baruth, K., & Carroll, J. J. (2002). A formal assessment of resilience: The Baruth protective factors inventory. Journal of Individual Psychology, 58, 235–244.

Battalio, S. L., Silverman, A. M., Ehde, D. M., Amtmann, D., Edwards, K. A., & Jensen, M. P. (2017). Resilience and function in adults with physical disabilities: An observational study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 98, 1158–1164.

Block, J., & Kremen, A. (1996). IQ an ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70 (2), 349–361.

Boardman, J., Blalock, C., & Button, T. (2008). Sex differences in the heritability of resilience. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 11 (1), 12–27.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bolton, K. W., & Osborne, A. S. (2016). Resilience protective factors in an older adults population: A qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis. Social Work Research, 40 (3), 171–181.

Article Google Scholar

Bonanno, G. A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., & Vlahov, D. (2007). What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. Death Studies, 31 (10), 863–883.

Brown-Yung, K., Walker, R. B., & Luszcz, M. A. (2017). An examination of resilience and coping in the oldest old using life narrative method. The Gerontologist, 57 (2), 282–291.

Brunet, J., & St-Aubin, A. (2016). Fostering positive experiences of group-based exercise classes after breast cancer: What do women have to say? Disability and Rehabilitation, 38 (15), 1500–1508.

Byun, J., & Jung, D. (2016). The influence of daily stress and resilience on successful ageing. International Nursing Review, 63, 482–489.

Canzan, F., Heilemann, M. V., Saiani, L., Mortari, L., & Ambrosi, E. (2014). Visible and invisible caring in nursing from the perspectives of patients and nurses in the gerontological context. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 28 (4), 732–740.

Charney, D. (2004). Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience and vulnerability: Implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 195–216.

Chow, S. M., Hamagani, F., & Nesselroade, J. R. (2007). Age differences in dynamical emotion-cognition linkages. Psychological Aging, 224 (4), 765–780.

Clark, A. P., McDougall, G., Riegel, B., Joiner-Rogers, G., Innerarity, S., Meraviglia, M., et al. (2015). Health status and self-care outcomes after an education-support intervention for people with chronic heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, Supplement, 1, S3–S13.

Connor, K., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scalre. Dpression and Anxiety, 18, 76–82.

Cornish, E. K., McKissic, S. A., Dean, D. A., & Griffith, D. M. (2017). Lessons learned about motivation from a pilot physical activity intervention for African American men. Health Promotion Practice, 18 (1), 102–109.

Cromwell, K. D., Chiang, Y. J., Armer, J., Heppner, P. P., Mungovan, K., Ross, M. I., et al. (2015). Is surviving enough? Coping and impact on activities of daily living among melanoma patients with lymphoedema. European Journal of Cancer Care, 24 (5), 724–733.

Damush, T. M., Perkins, S. M., Mikesky, A. E., Roberts, M., & O’Dea, J. (2005). Motivational factors influencing older adults diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis to join and maintain an exercise program. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 13 (1), 45–60.

de Souto Barreto, P., Morley, J., Chodzko-Zajko, W. K. H., Weening-Djiksterhuis, E., Rodriguez-Mañas, L., Barbagallo, M, … Rolland, Y. (2016). Recommendations on physical activity and exercise for older adults living in long-term care facilities: A taskforce report. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17 (5), 381–392.

Friborg, O., Hjemdal, O., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Martinussen, M. (2003). A new rating scale for adult resilience: What are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 12, 65–76.

Fullen, M. C., & Gorby, S. R. (2016). Reframing resilience: Pilot evaluation of a program to promote resilience in marginalized older adults. Educational Gerontology, 42 (9), 660–671.

Galik, E., Resnick, B., Gruber-Baldini, A., Nahm, E. S., Pearson, K., & Pretzer-Aboff, I. (2008). Pilot testing of the Restorative Care Intervention for the cognitively impaired. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 9 (7), 516–522.

Galik, E., Resnick, B., Hammersla, M., & Brightwater, J. (2014). Optimizing function and physical activity among nursing home residents with dementia: Testing the impact of Function Focused Care. The Gerontologist, 54 (6), 930–943.

Galik, E., Resnick, B., & Pretzer-Aboff, I. (2009). Knowing what makes them tick: Motivating cognitively impaired older adults to participate in restorative care. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 15 (1), 48–55.

Germain, A., Mayland, C. R., & Jack, B. A. (2016). The potential therapeutic value for bereaved relatives participating in research: An exploratory study. Palliative & Supportive Care, 14 (5), 479–487.

Goris. E. D., Ansel, K. N., & Schutte, D. L. (2016). Quantitative systematic review of the effects of non-pharmacological interventions on reducing apathy in persons with dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72 (11), 2612–2628..

Greenwood-Hickman, M. A., Renz, A., & Rosenberg, D. E. (2016). Motivators and barriers to reducing sedentary behavior among overweight and obese older adults. Gerontologist, 56 (4), 660–668.

Grothberg, E. (2003). Resilience for today: Gaining strength from adversity . Wesport, CT: Praeger.

Guest, R., Craig, A., Tran, Y., & Middleton, J. (2015). Factors predicting resilience in people with spinal cord injury during transition from inpatient rehabilitation to the community. Spinal Cord, 53 (9), 682–686.

Hansen, E., Landstad, B. J., Hellzén, O., & Svebak, S. (2011). Motivation for lifestyle changes to improve health in people with impaired glucose tolerance. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 25 (3), 484–490.

Hardy, S., Concato, J., & Gill, T. M. (2004). Resilience of community-dwelling older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52 (2), 257–262.

Harris, P. (2008). Another wrinkle in the debate about successful aging: The undervalued concept of resilience and the lived experience of dementia. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 67 (1), 43–61.

Hashimoto, M., Kato, S., Tanabe, Y., Katakura, M., Mamun, A. A., Ohno, M., … Shido, O. (2017). Beneficial effects of dietary docosahexaenoic acid intervention on cognitive function and mental health of the oldest elderly in Japanese care facilities and nursing homes. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 17 (2), 330–337.

Hjemdala, O., Friborgb, O., Braunc, S., Kempenaersc, C., Linkowskic, P., & Fossiond, P. (2011). The Resilience Scale for adults: Construct validity and measurement in a Belgian sample. International Journal of Testing, 11 (1), 53–70.

Hung, L., Chaudhury, H., & Rust, T. (2016). The effect of dining room physical environmental renovations on person-centered care practice and residents’ dining experiences in long-term care facilities. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 35 (12), 1279–1301.

Ikemata, S., & Momose, Y. (2017). Effects of a progressive muscle relaxation intervention on dementia symptoms, activities of daily living, and immune function in group home residents with dementia in Japan. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 14 (2), 135–145.

Johnson, J., Gooding, P. A., Wood, A. M., & Tarrier, N. (2010). Resilience as positive coping appraisals: Testing the schematic appraisals model of suicide (SAMS). Behavioral Research and Therapy, 48 (3), 179–186.

Karoly, P., & Ruehlman, L. S. (2006). Psychological “resilience” and its correlates in chronic pain: Findings from a national community sample. Pain, 123 (1), 90–97.

Katrancha, E. D., Hoffman, L. A., Zullo, T. G., Tuite, P. K., & Garand, L. (2015). Effects of a video guided T’ai Chi group intervention on center of balance and falls efficacy: A pilot study. Geriatric Nursing, 36 (1), 9–14.

Koskenniemi, J., Leino-Kilpi, H., & Suhonen, R. (2015). Manifestation of respect in the care of older patients in long-term care settings. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 29 (2), 288–296.

Kosteli, M. C., Williams, S. E., & Cumming, J. (2016). Investigating the psychosocial determinants of physical activity in older adults: A qualitative approach. Psychology & Health, 31 (6), 730–749.

LeBrasseur, N. K. (2017). Physical resilience: Opportunities and challenges in translation. Journal of Gerontology A: Biological and Medical Sciences, 72 (7), 978–979.