An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Diabetes Res

- v.2022; 2022

Prevention and Management of Diabetes-Related Foot Ulcers through Informal Caregiver Involvement: A Systematic Review

Joseph ngmenesegre suglo.

1 Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery and Palliative Care, Kings College London, UK

2 Department of Nursing, Presbyterian University College Ghana, Ghana

Kirsty Winkley

Jackie sturt, associated data.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files.

The literature remains unclear whether involving informal caregivers in diabetes self-care could lead to improved diabetic foot outcomes for persons at risk and/or with foot ulcer. In this review, we synthesized evidence of the impact of interventions involving informal caregivers in the prevention and/or management of diabetes-related foot ulcers.

A systematic review based on PRISMA, and Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) guidelines was conducted. MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trial of the Cochrane Library databases were searched from inception to February 2021. The following MESH terms were used: diabetic foot, foot ulcer, foot disease, diabetes mellitus, caregiver, family caregiver ,and family. Experimental studies involving persons with diabetes, with or at risk of foot ulcers and their caregivers were included. Data were extracted from included studies and narrative synthesis of findings undertaken.

Following the search of databases, 9275 articles were screened and 10 met the inclusion criteria. Studies were RCTs ( n = 5), non-RCTs ( n = 1), and prepoststudies ( n = 4). Informal caregivers through the intervention programmes were engaged in diverse roles that resulted in improved foot ulcer prevention and/or management outcomes such as improved foot care behaviors, increased diabetes knowledge, decreased HbA1c (mmol/mol or %), improved wound healing, and decreased limb amputations rates. Engaging both caregivers and the person with diabetes in education and hands-on skills training on wound care and foot checks were distinctive characteristics of interventions that consistently produced improved foot self-care behavior and clinically significant improvement in wound healing.

Informal caregivers play diverse and significant roles that seem to strengthen interventions and resulted in improved diabetes-related foot ulcer prevention and/or management outcomes. However, there are multiple intervention types and delivery strategies, and these may need to be considered by researchers and practitioners when planning programs for diabetes-related foot ulcers.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is among the top four noncommunicable diseases (NCD) targeted for action under the Sustainable Development Goals by the United Nations in 2015. Thus, all member countries are required to reduce premature death due to NCD by a third before 2030 [ 1 ]. Over 460 million people had diabetes in 2019, and this number has been estimated to rise to 578 million and 700 million by 2030 and 2045, respectively [ 2 ]. This high prevalence of diabetes and its complications puts pressure on global health expenditure. For instance, in 2017, the global health expenditure was estimated at over 7 billion USD with around 4 million diabetes related deaths [ 3 ].

One of the commonest and most debilitating complications of diabetes is diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) [ 4 ]. People with diabetes have a lifetime risk of up to 25% of developing DFU, and this greatly increases their chances of lower limb amputations [ 5 ]. This has made DFU the leading cause of nontraumatic amputations [ 5 ], and morbidity and mortality related to DFU are almost 50% over a five-year period [ 6 ].

The burden and debilitating effects of DFU reflect the need for strategic interventions to prevent and/or manage DFUs. Patient education, specialist care, clear referral pathways, use of multidisciplinary/professional teams, and other stringent interventions have significantly reduced foot ulcers and lower limb amputation (LLA) in developed countries over the past two decades [ 7 – 9 ]. For instance, to manage and/or prevent foot complications, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the use of health professional led multidisciplinary foot care service teams. The guideline stipulates that those persons with diabetes should be assessed for their risk of foot problems when diabetes is diagnosed and at least annually thereafter. Appropriate management and/or prevention services are then put in place based on the risk stratification of the patient [ 10 ]. Similarly, the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) in its evidence-based guidelines suggested that all preulcerative signs on the foot of persons with diabetes must be treated. The IWGDF further recommended that recurrent foot ulcers should be prevented through the provision of integrated foot care. This integrated foot care includes professional foot care, adequate footwear, and structured education about foot care [ 11 ].

Apparently, prevention of DFU requires persons with diabetes to engage in appropriate self-care behaviors relating to wearing off-loading footwear, exercise, diet, blood glucose monitoring, medication, and foot care [ 10 – 12 ]. Nevertheless, self-care behavior in the management of chronic conditions like diabetes is a complex phenomenon and impacted by multiple factors including but not limited to issues pertaining to problem solving skills, self-efficacy, and environment [ 13 – 15 ]. Thus, the social environment consisting of family members, friends, and significant others of persons with diabetes stands as one of the factors that can significantly influence individual's ability to manage diabetes-related foot ulcers (DFUs) at home [ 16 – 18 ]. Consequently, it has been suggested that diabetes self-management interventions should demonstrate active patient engagement and involvement of the caregivers of people with diabetes [ 18 – 20 ]. Involving informal caregivers (ICG) in caring for DFU is particularly important to achieving treatment goals especially in settings where family ties are strong [ 21 ], and it is also a cost-effective strategy [ 20 , 22 ]. ICG refers to persons providing unpaid services to the patient and may include parents, children, spouse, friends, other relatives, or nonkin. They are sometimes called ‘family caregivers,, or ‘caregivers' [ 23 ]. Though mostly not formally trained, they feel they have a moral and social obligation to care for the sick at home [ 20 ].

The presence of ICG at home can play the role of negotiating and monitoring how well patients are following self-management plans [ 20 ], detecting any improvement or deterioration in patients' health situation while providing care and calling for medical assistance when needed [ 24 ]. The social support offered by ICGs also creates a feeling of acceptance and high level life satisfaction among persons with diabetes-related foot problems [ 25 ]. However, it has been identified that majority of ICG fear making mistakes and found tasks such as wound dressing to be emotionally challenging and indicated that they needed training to be effective at home [ 26 ]. Despite some of the known evidence of the active role ICGs can play in DFU care, a systematic review indicated that from 1995 to 2013, only 1% of publications in the literature mentioned ICGs as members of the wound care team [ 27 ]. It was identified in another study that 11% of ICGs are actively involved in the management of DFU and that interventions should be planned to include patients and their ICGs [ 19 ]. To effectively engage ICGs in DFU interventions, there is the need to synthesize the evidence to ascertain the impact of ICGs on the prevention and/or management of DFUs. Therefore, this review is aimed at the following:

- Determine how informal caregivers' engagement in interventions can aid in the prevention and management of diabetes-related foot ulcers in adults

- Understand the types of interventions participated in by informal caregivers to prevent and/or manage diabetes-related foot ulcers

2. Materials and Methods

This review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [ 28 ] together with recommendations from the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic review guidelines [ 29 ]. The protocol was duly registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO, with registration number: CRD42021231768.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The review was based on predefined criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies as indicated in Table 1 .

Eligibility criteria for studies.

2.2. Searching and Selection of Studies

The search for studies was conducted in five databases without recourse to publication date, country, or language. Using both subject headings and key words, a search strategy (see supplementary file 1 ) was constructed and optimized for each of the following databases from inception to February 2021: MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trial of the Cochrane Library. Additionally, the reference list of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were screened for studies that might have been missed by the searched strategy. All searched outcomes were imported into Covidence systematic review manager, and duplicates were automatically detected and removed. Titles and abstracts of the studies were then screened and studies not relevant to the aim of this review excluded. The full text of potentially eligible studies was read in full by two authors, and disagreements were discussed to reach consensus.

2.3. Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

The Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias for RCTs [ 30 ] and risk of bias in nonrandomized studies of interventions (ROBINS-I) [ 31 ] tools were used in assessing the studies. Certainty of the evidence was ranked using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) guidelines for no single or no pooled estimate of effect [ 32 ]. Rating was done using the GRADEpro GDT software ( https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/#organizations ).

Data extraction used a modified template in covidence which was first piloted with one study. Also, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist [ 33 ] was used to guide the extraction of the necessary components of various interventions in studies. Key data extracted from studies included study reference, objective, setting, sample for intervention and control groups, participants characteristics, postintervention follow-up time, intervention description, and relevant outcomes.

2.4. Data Synthesis

A narrative synthesis of findings guided by the SWiM guidelines [ 29 ] was undertaken due to high heterogeneity in included studies in their intervention types, duration, data collection time points, and settings which made meta-analysis inappropriate. Therefore, data was synthesized based on direction of effect. Based on the objectives of this review, the first stage of synthesis was done to determine how ICG interventions aided outcomes pertaining to the prevention and management of DFU, and the second stage evaluated the various types of ICG interventions utilized to prevent or manage DFU. Studies were grouped based on the outcomes reported, and these outcomes were subsequently grouped into DFU prevention outcomes and DFU management outcomes. The prevention outcomes included HbA1c, diabetes knowledge, and foot self-care behavior/practices, while the DFU management outcomes measured among persons with current DFU included wound healing and limb amputation. To facilitate description of the ICG interventions, study intervention types were coded as educational, behavioral, psychological, and mixed (psychobehavioral/educational) [ 34 , 35 ]. Educational interventions were programs implemented by the health professional that focused on providing participants with information to enhance their knowledge of foot and diabetes self-management. Behavioral interventions focus on skills training, change in skills and lifestyle, aimed at improving self-management behaviors. Interventions were classed as psychological if their major aim were to address negative mood states, social support, and coping skills. Finally, interventions were described as mixed if they used two or more of the above categories of interventions.

3. Results of Review

3.1. search results.

The primary search of databases identified seven eligible papers and several relevant systematic reviews. The reference list of systematic reviews was checked, and further three eligible papers were identified from three systematic reviews [ 36 – 38 ]. This resulted in ten primary studies being included in this review. The searching and selection of studies and reasons for excluding studies after full-text retrieval are presented in Figure 1 , PRISMA flow diagram.

PRISMA flow diagram for study identification and selection process.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

The review included 10 studies. Three of the studies came from the USA [ 39 – 41 ], two from China [ 42 , 43 ], two from Indonesia [ 44 , 45 ] and one each from Iran [ 46 ], Ireland [ 47 ], and India [ 48 ]. The total number of participants with diabetes was 5532. Only five studies [ 39 , 41 , 43 – 45 ] reported the characteristics and number of caregivers involved which was 359. Majority of caregivers were female (73.6%), and family relationship was mostly spouse or partner (53.6%), son/daughter (28.3%), or other family members (14.7%). Parents and siblings were the least likely to be involved as caregivers, 1.5% and 1.9%, respectively. Table 2 presents the characteristics of studies.

Characteristics of studies.

I: intervention group; C: controlled group; SD: standard deviation; RCT: randomized controlled trial; non-RCT: nonrandomized controlled trial; LLA: lower limb amputation; PEDIS: Perfusion, Extent, Depth, Infection and Sensation; MS: mean square between subjects; %: percentage; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; vs.: versus; DSME: diabetes self-management education; ADA: American Diabetes Association.

3.3. Risk of Bias and GRADE Assessment

The risk of bias assessment of studies indicating authors judgement with supporting reasons are presented as supplementary files 2 and 3 for RCTs and non-randomized studies, respectively. All the RCTs had high risk of bias for nonblinding of participants and personnel since it was not possible to blind these people. Apart from one study [ 47 ], it was unclear if outcome assessors were blinded or not. Non-RCT studies were all rated moderate for bias due to confounding, and they all also had an overall moderate risk of bias. GRADE assessment for each outcome followed the criteria for evidence ranking in the absence of single estimate of effect [ 32 ]. Most outcomes were graded as moderate (see Table 3 ) due to serious risk of bias, serious inconsistency, but not serious indirectness and imprecision.

Diabetes-related foot ulcer prevention outcomes.

Key: DFSCBS: Diabetes Foot Self-care Behaviour Scale; SDSCA: Summary of Diabetes Self-care Activities scale; DFUAS: Diabetes Foot Ulcer Assessment Scale; PEDIS: Perfusion, Extent, Depth, Infection and Sensation; SKILLD: Spoken Knowledge in Low Literacy patients with Diabetes; DKQ: Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire; DFCS: Diabetes Foot Care Scale.

3.4. Outcomes and Measures

The first objective of this review was to determine how ICG interventions aided the prevention and management of DFUs. The outcomes reported by studies consisted of DFU prevention and DFU management outcomes as presented in Tables Tables3 3 and and4, 4 , respectively. Prevention outcomes reported by almost all studies included foot self-care behaviors/practices of participants, diabetes knowledge, and HbA1c [ 39 – 44 , 46 – 48 ]. Wound healing and limb amputations/surgical interventions were the DFU management outcomes indicated by four studies [ 42 , 44 , 45 , 48 ].

Diabetes-related foot ulcer management outcomes.

Key: DFSCBS: Diabetes Foot Sel-care Behaviour Scale; SDSCA: Summary of Diabetes Self-care Activities scale; DFUAS: Diabetes Foot Ulcer Assessment Scale; PEDIS: Perfusion, Extent, Depth, Infection and Sensation; SKILLD: Spoken Knowledge in Low Literacy patients with Diabetes; DKQ: Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire; DFCS: Diabetes Foot Care Scale.

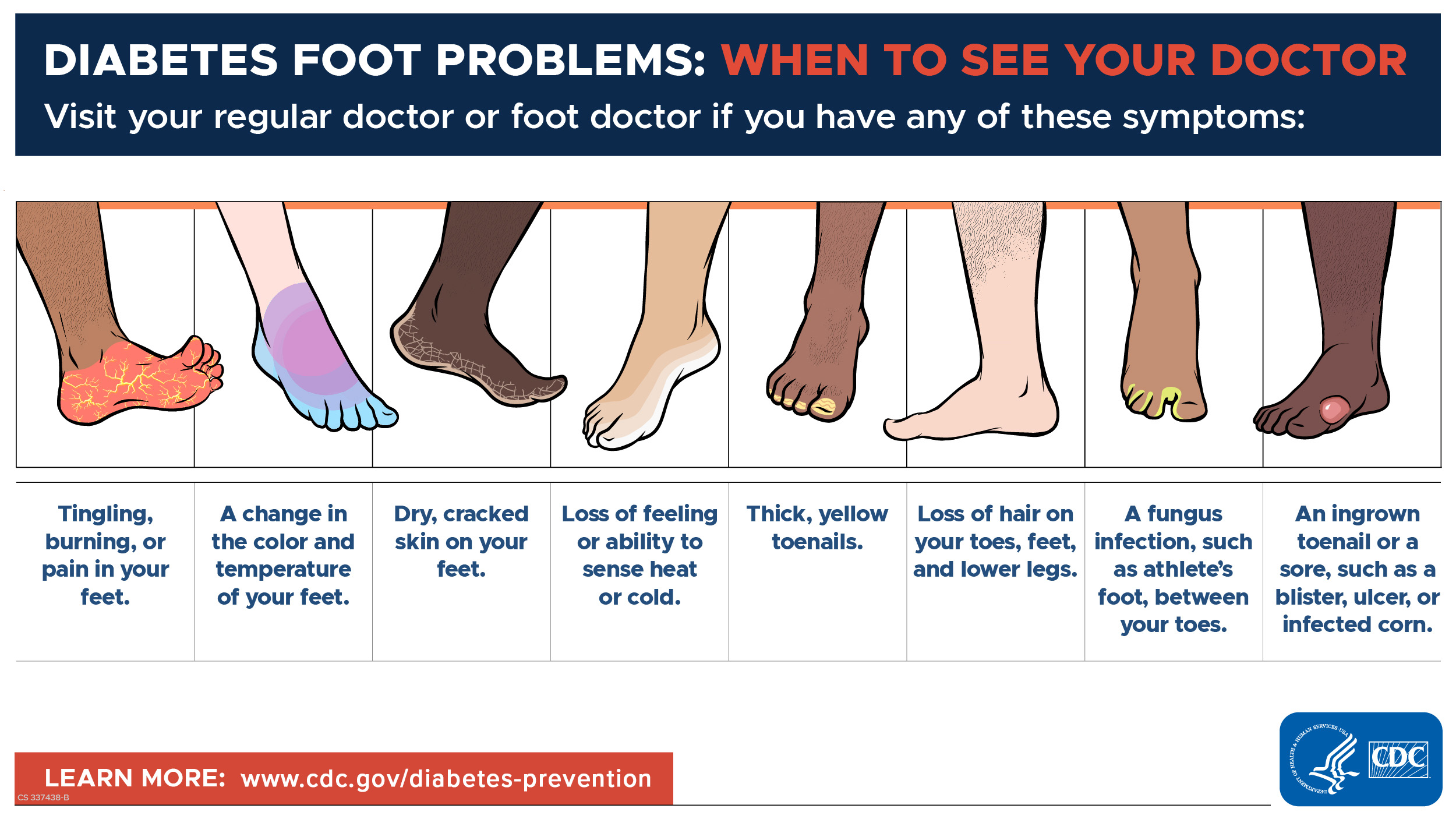

Seven studies assessed the foot self-care behavior and practices of participants, and six of them indicated improvement in foot care behavior of participants at follow-up [ 39 – 43 , 46 ]. Five studies further indicated that the change in foot care practice was significant in the ICG intervention groups [ 40 – 43 , 46 ]. The foot care activities engaged in by ICGs included assisting persons with diabetes in nail trimming, daily foot inspection, footwear inspection, checking of water temperature before patients washed their feet, checking of protective foot sensitivity using monofilaments, and collaborative problem solving. The assessment of participants' foot care behavior differed across studies. In majority of the outcome measure instruments, foot care questions were few, and only a part of a generic tool used in assessing participants' diabetes self-management activities [ 39 – 41 , 46 , 47 ]. However, two studies used diabetes foot self-care behavior scale (DFSCBS) and diabetes foot care scale (DFCS) that were specifically designed for assessing foot care practices [ 42 , 43 ]. Both the generic diabetes self-management tools (summary of diabetes self-care activities scale (SDSCA)) and specifically devised foot care measure (DFCS) both recorded improved foot care practices among participants.

Study participants' knowledge on diabetes was assessed by three studies, and all of them reported significant improvement at postintervention follow-ups [ 40 ]–[ 42 ]. A supportive family member or friend was included in these interventions to encourage shared learning and to enhance the abilities of the ICG to know how to be helpful to the person with diabetes. Diabetes knowledge was assessed using either the Spoken Knowledge in Low Literacy patients with Diabetes (SKILLD) [ 40 , 41 ] or Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire (DKQ) [ 42 ]. Both outcome measure instruments suggested that interventions were effective in improving diabetes knowledge among participants [ 40 – 42 ].

Finally, under DFU prevention outcome, all ten included studies except one [ 43 ] investigated participants HbA1c at various time points' postintervention. Even though all nine studies reported reduction in HbA1c, almost equal number of studies, four and five reported insignificant and significant improvement, respectively, at postintervention follow-up. Measuring HbA1c at 3, 6, 12, or 18 months postintervention could still result in either significant or insignificant improvement in HbA1c results. The ICGs and persons with diabetes in the intervention groups were offered education on physical activity (exercise), blood glucose monitoring, healthy eating habits, and medication regimens. ICGs acted as support persons and helped in dietary planning and setting of diabetes management goals.

DFU management outcomes were assessed among participants who already had DFU problems. Healing of diabetic wounds was objectively assessed in three studies [ 44 , 45 , 48 ], and all of them reported clinically significant improvement in wound size. Limb amputations/surgical interventions prevalence was also recorded by two studies [ 42 , 48 ]. These studies observed that even though the difference was not significant, amputations were lower in the study intervention group compared to study control group [ 42 ]. To actively support the management of DFU, ICGs in the intervention programs together with the person with DFU were trained on wound care. Family caregivers were taught their roles and effective involvement in DFU care, problem solving skills, and diet planning [ 42 , 44 , 45 , 48 ].

3.5. Intervention Types

Various intervention types as operationally defined earlier were implemented to prevent and/or manage DFU. They included six psychobehavioral/educational type intervention [ 39 – 41 , 44 – 46 ], two behavioral [ 42 , 48 ] and one each of psychological [ 47 ] and educational interventions [ 43 ]. These interventions were delivered over several sessions with a mean of 15 (range 3 to 24) over a mean duration of 20 weeks (range 3 to 104) (see supplementary file 4 for coded intervention types and delivery methods).

The study intervention types implemented produced similar results on the outcomes measured. Apart from psychological intervention [ 47 ], all other intervention types reported improved diabetes knowledge and foot care behavior. These interventions were delivered through a mixture of didactic and interactive teaching methods, through face-to-face or phone calls. A mixed format of intervention delivery which involves a combined use of face-to-face, phone calls, videotapes and information booklets was utilized in behavioral or mixed psychobehavioral/educational interventions and resulted in significant improvement in foot self-care practices among participants [ 40 – 42 , 45 , 46 ]. ICGs and persons with diabetes were taught together in all interventions to promote shared learning and agreed self-care goals.

Behavioral interventions in China and India resulted in both improved foot care practices and lower prevalence of amputations [ 42 , 48 ]. In these behavioral interventions, participants with diabetes and their caregivers were provided with skills training on various foot care activities and study participants tasked to report to clinic with any sign of foot disease for treatment. This intervention type even at long-term follow-up still recorded significant results at 12 months and 18 months, respectively, for Liang et al. [ 42 ] and Viswanathan et al. [ 48 ].

Also, behavioral [ 48 ] and mixed behavioral/educational interventions [ 44 , 45 ] produced clinically significant reduction in diabetic wound size and healing time. Persons with diabetes and their ICGs in these interventions were engaged in participatory diabetes education, hands-on workshop on wound care, problem solving skills, and establishment of family roles in DFU care. Thus, an interactive and mixed method of teaching was utilized to achieve wound healing results. In these participatory teaching methods, diabetes self-management activities were discussed, and concerns of both the person with diabetes and their ICG were addressed before setting diabetes management goals [ 39 – 41 , 46 ].

4. Discussion

4.1. main findings.

This review is the first systematic review focusing solely on DFU and ICGs. It identified that trials of ICG interventions resulted in improved DFU prevention and management outcomes, possibly through the diverse roles played by ICGs. Thus, designing of interventions to engage family caregivers strengthened the programs, and this is evidenced in the improved foot self-care practices, improved diabetes knowledge, and better DFU management outcomes in the ICG intervention groups. Caregivers actively participated in the prevention of DFU through their diverse activities ranging from working collaboratively with the person with diabetes in feet inspection, checking of feet sensation, diet/meal planning, and setting of diabetes self-management goals. The management of DFUs was facilitated by ICGs through their engagement in wound care and participatory problem-solving activities. ICG participation in interventions characterized by hands-on skills training on wound and/or foot care, combined used of interactive, face-to-face and phone calls intervention delivery resulted in improved foot self-care behaviors and wound healing.

4.2. Findings Compared to Wider Evidence

The impacts of ICG interventions identified in this review are not dissimilar to other previous systematic reviews indicating that involvement of family caregivers in interventions improved clinical outcomes for persons with cancer, stroke, and other debilitating chronic conditions [ 21 , 49 – 52 ]. For instance, an evidence synthesis involving stroke survivors indicated that family-oriented interventions were effective in reducing poststroke depression and improving the quality of life of both patients and caregivers [ 53 ]. Similar significant improved health outcomes were detected among persons with cancer and their family caregivers [ 51 , 54 ]. Generally, the involvement of ICGs in the management of community-based adult is widely recommended as superior to patient-only interventions [ 55 – 57 ]. This probably is based on the assertion that family health and function influence the health status and functioning of individual family members, and a joint family and patient intervention could produce better health outcome for both. In the context of diabetes, our review findings resonates with previous systematic reviews suggesting that involvement of caregivers and social support significantly improves self-management behaviors and health outcomes of persons with diabetes [ 36 , 58 ]. Our review reiterates the significance of ICG and the patient's social environment in the diabetes self-management continuum, and this could be applied in the prevention and management of diabetes-related foot ulcer. A review of reviews suggested that ICGs were often included in interventions and acted as a surrogate for the health care provider and the health care system. Family members were used as substitutes for professionals to deliver needed care, monitor, or encourage the patient to achieve desired health outcomes. These interventions were planned to strengthen family's ability to work together with the person with the chronic condition in solving challenging situations [ 21 ]. This consolidates our findings suggesting that ICGs were involved in setting diabetes management goals, diet planning, and other activities that strengthened the interventions and resulted in improved clinical outcomes. The skills and competence of these ICGs in our review were probably enhanced through the workshops and interactive sessions of the interventions. The need to train and engage ICGs in wound care process was further suggested in a national survey conducted in the United States. The survey reported that over a third of caregivers were providing wound care at home but indicated they were afraid of making mistakes and needed some skill training [ 59 ]. Therefore, the design of foot care programs could make family caregivers more confident in their support roles by incorporating easy-to-follow training for them. Nevertheless, even though none of the included studies critiqued or assessed how interventions affected ICG themselves, it is important that such programs prevent patient-caregiver conflicts by maintaining patient autonomy and reducing diabetes distress [ 20 ]. This might be necessary in maximizing the impact and sustainability of such ICG interventions.

This narrative synthesis further described the various types of interventions participated in by ICGs. Both persons with diabetes and their ICGs participated in interventions that were focused on providing problem-solving skills, foot care skills, and general diabetes information using diverse intervention delivery strategies. This seems to be consistent with previous study findings that education combined with specific behavioral change strategies produced improved health outcomes for persons with chronic conditions [ 35 , 60 , 61 ]. Our findings suggest that interventions that taught both patient and carer how to examine feet and provide foot-related care and wound care improved outcomes. Nevertheless, this does not corroborate with previous systematic reviews and meta-analysis suggesting that foot care education alone has no significant effect and that there is no advantage of combining different educational approaches in preventing/reducing DFU [ 62 ]. Another Cochrane review indicated that even though foot care knowledge and self-reported patient behavior seem to be positively influenced by education in the short term, there is insufficient robust evidence that patient education alone is effective in achieving clinically relevant reductions in ulcer and amputation incidence [ 9 ]. The differences in findings and the results of these systematic reviews [ 9 , 62 ] must be viewed with caution as they reviewed educational intervention studies that focused primarily on the patient alone. However, this also suggest the need for future reviews to examine whether educational interventions engaging both patient and their ICG resulted in better DFU clinical outcomes compared with interventions targeting patients alone. This will reaffirm how and whether it is more beneficial to engage both persons with diabetes and their ICG when planning DFU programs.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

This review is the first of its kind focusing solely on ICGs and DFU. It uses transparent and rigorous methods, following the PRISMA and SWiM guidelines, and this allows for reproducibility of this study. A limitation of this review is that, despite a comprehensive search strategy, eligible studies were identified from only six countries across the globe. This makes it unclear to what extend findings may be applicable to other dissimilar contexts. This indicates the dearth of literature in the field, and given the potential devastating impact of DFUs, more research is needed in other contexts and the findings integrated into appropriate health system response. Most outcomes on the GRADE evidence rating were ranked moderate due to risk of bias especially with baseline confounders in the quasiexperimental studies. Hence, subsequent studies should adapt a well-designed RCT approach to be able establish the exact impact of ICG interventions.

4.4. Recommendations for Practice, Research, and Policy

Based on the evidence of the roles ICGs play in diabetes-related foot ulcer prevention, health care practitioners ought to recognize carers as active members in DFU prevention and/or management strategies. This implies involving them in planning and determining diabetes management goals, establishing their specific roles and how they can be effectively involved in foot disease prevention and management. As part of diabetes self-management education and support (DSME/S), practitioners should take pragmatic efforts to enhance the knowledge, skills, and confidence of ICGs by organizing easy to do skills training and education for both carers and patients. Also, ICG involvement holds advantages in high and low resource settings and policymakers could optimize their health expenditure by supporting the involvement of this unpaid caring work by upskilling ICGs. There is evidence that involving both ICGs and patients in the management of chronic conditions is cost-effective and interventions produces long-lasting effects [ 20 , 22 ]. Foot specialist services and other foot care resources are mostly either not available or not affordable to persons especially in developing countries. Involving ICGs could be an innovative health care intervention to prevent foot disease. It is therefore imperative that these interventions need evaluating in lower resource settings where the involvement of knowledgeable, skilled and confident ICGs could reap significant benefits to their family and community in the absence of access to high quality healthcare for people with and/or at risk of diabetic foot disease.

Data Availability

This study is part of the first author's PhD thesis at King's College London funded by the Centre for Doctoral Studies under the Africa International Postgraduate Research Scholarship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary 1.

Supplementary file 1: search strategy.

Supplementary 2

Supplementary file 2: risk of bias for RCTs.

Supplementary 3

Supplementary file 3: Risk of bias for non-RCTs.

Supplementary 4

Supplementary file 4: description of interventions.

Supplementary 5

Supplementary file 5: coded intervention elements.

Supplementary 6

PRISMA checklist.

- Open access

- Published: 06 August 2022

A qualitative study of barriers to care-seeking for diabetic foot ulceration across multiple levels of the healthcare system

- Tze-Woei Tan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6658-9482 1 , 2 ,

- Rebecca M. Crocker 3 ,

- Kelly N. B. Palmer 3 ,

- Chris Gomez 4 ,

- David G. Armstrong 1 , 2 &

- David G. Marrero 3

Journal of Foot and Ankle Research volume 15 , Article number: 56 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

6224 Accesses

12 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Introduction

The mechanisms for the observed disparities in diabetes-related amputation are poorly understood and could be related to access for diabetic foot ulceration (DFU) care. This qualitative study aimed to understand patients’ personal experiences navigating the healthcare system and the barriers they faced.

Fifteen semi-structured interviews were conducted over the phone between June 2020 to February 2021. Participants with DFUs were recruited from a tertiary referral center in Southern Arizona. The interviews were audio-recorded and analyzed according to the NIMHD Research Framework, focusing on the health care system domain.

Among the 15 participants included in the study, the mean age was 52.4 years (66.7% male), 66.7% was from minority racial groups, and 73.3% was Medicaid or Indian Health Service beneficiaries. Participants frequently reported barriers at various levels of the healthcare system.

On the individual level, themes that arose included health literacy and inadequate insurance coverage resulting in financial strain. On the interpersonal level, participants complained of fragmented relationships with providers and experienced challenges in making follow-up appointments. On the community level, participants reported struggles with medical equipment.

On the societal level, participants also noted insufficient preventative foot care and education before DFU onset, and many respondents experienced initial misdiagnoses and delays in receiving care.

Conclusions

Patients with DFUs face significant barriers in accessing medical care at many levels in the healthcare system and beyond. These data highlight opportunities to address the effects of diabetic foot complications and the inequitable burden of inadequately managed diabetic foot care.

Peer Review reports

Diabetic foot ulceration (DFU) is a common and often catastrophic complication for people with diabetes. In the United States, people with diabetes have an up to 34% lifetime risk of developing a foot ulcer [ 1 , 2 ], a medical complication that increases their five-year mortality rate by 2.5 times [ 3 , 4 ]. Moreover, foot ulceration is a causal factor for up to 85% of diabetic patients who subsequently undergo lower extremity amputation [ 1 , 5 ]. As compared to the overall United States population, people with diabetes are more likely to undergo lower extremity amputation and repeat amputations [ 1 , 6 ]. The annual medical cost associated with DFU care in the United States is an additional $9–13 billion on top of other costs associated with diabetes [ 7 ].

Moreover, DFUs and subsequent amputations are unevenly patterned along lines of racial and ethnic minority status, low socio-economic status, low insurance coverage rates, and geographic isolation. African American, Hispanic, and Native American adults with diabetes have higher prevalence of DFUs and amputation than their White counterparts [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Across the board, patients in the lowest income quartiles experience higher odds of amputation and death due to peripheral artery disease [ 11 , 12 ]. In addition, those with suboptimal or no medical insurance are at an elevated risk of major amputation [ 13 ]. This illuminates a glaring and yet unabated public health problem, especially among minority and low-income populations [ 8 , 9 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ].

The mechanisms of these observed disparities in DFU incidence and progression are poorly understood [ 9 , 11 , 17 , 18 ]. There is evidence, however, indicating that access to affordable and quality medical care, preventive services, and limb salvage care is an important contributing factor to disparities in amputation rates [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. This qualitative study aimed to understand patients’ personal experiences with DFUs in a safety net health system, including their processes of navigating the healthcare system and the barriers they faced. The themes elicited in the study concerning multiple barriers at varying levels of the healthcare system will help to improve health care delivery in a population experiencing elevated risks of diabetes-related ulceration and amputation.

This qualitative study was designed to better understand the various challenges faced by patients with a history of DFUs and lower extremity amputations as they managed their conditions and sought medical care. Semi-structured interviews were conducted between June 2020 to February 2021 and the results were analyzed according to the “Health Care System” domain of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework [ 22 ]. The University of Arizona Institutional Review Board approved the study in July 2019 (Protocol Number 1906749805).

Participants

Patients were selected from the Southwestern Academic Limb Salvage Alliance (SALSA), a multidisciplinary limb salvage care team located in Tucson, Arizona, to participate in semi-structured interviews. SALSA treats over 5,000 patient visits annually for diabetic foot problems, of which 40% are from racial and ethnic minority groups. It is the primary referral center for limb salvage and care for minorities and patients with low socioeconomic status in suburban and rural Arizona. Participants were identified and approached for participation during scheduled clinic appointments or by follow-up phone calls by our research team. We purposely sampled participants, using criterion sampling, to reflect the diverse range of race/ethnicity, gender, history of DFU, foot infection, minor amputation (below the ankle), and major amputation (ankle or above) treated by SALSA [ 23 ].

Interview guide and data collection

The research team jointly developed a semi-structured interview guide to encourage patient perspectives regarding their living experiences with foot ulceration and how they sought care for DFUs. Interviews were conducted in the patients’ preferred language (English or Spanish). Three research team members experienced in qualitative interviews (R.M.C., K.N.B.P., and D.G.M.) completed 15 interviews over the phone, lasting 40–60 min each. Interviews were recorded with consent using the “Tape A Call” mobile application ( www.tapeacall.com ) or via the University of Arizona Health Sciences Zoom Platform. The interviews were conducted in phases to allow for simultaneous analysis and redirection of subsequent data collection.

The research team used the Dedoose software version 9.0.17 (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Los Angeles, CA) to assist in data storage, coding, and data analysis. Audio files of the interviews were transcribed into the language spoken. After a quality assurance check, the transcriptions were uploaded into the software. The transcripts were independently reviewed and coded by three members of the research team (R.M.C., K.N.B.P., and T-W.T.). Data for this article were analyzed according to the NIMHD Research Framework (2017) that includes a multilevel approach including individual, interpersonal, community, and societal-level factors. While this model includes several domains, for the purposes of this paper we are focusing only on the Health Care System domain. This framework has been used in health disparities research to conceptualize and evaluate a wide array of determinants that promote or worsen health disparities [ 24 ]. Team members met regularly to compare coding results and resolve discrepancies by discussion and consensus.

The study sample included 15 participants (Table 1 ). The mean age was 54.2 years. Eleven participants (73.3%) were Medicaid or Indian Health Program beneficiaries and 80% of participants were either unemployed or had retired. All participants had history of at least one DFU, 12 had a history of foot infection, eight underwent minor amputations, and one had a major amputation. Four patients underwent at least one open surgery or endovascular procedure due to peripheral artery disease. During the interviews, participants frequently reported barriers at various levels of the health care system (Table 2 , Fig. 1 ).

Patient reported barriers at all levels influence of the health care system domain

Individual Level of Influence

Health literacy.

While most participants were aware of the risks of foot infection and amputation, there were significant gaps in their health literacy that compromised their ability to make informed decisions about when and how to seek medical care. Most notably, although all participants had a history of DFUs, many were unfamiliar with the term “ulcer” and expressed confusion when interviewers asked questions using that term. This finding, which reflects poor communication by providers and medical staff, resulted in most participants using alternate terms such as “blister,” “callous,” “cut,” “infection,” and “injury” to describe their foot abnormalities. This confusion in terminology was critical, as many patients described not initially seeking medical care because they interpreted their foot abnormality to be a common, everyday problem rather than one warranting medical attention. As one participant described: “Nobody ever really said what I’m looking for just anything that is not normal, I guess. But like I said, I have never heard of a diabetic foot ulcer.” (57-year-old Hispanic male, history of DFU).

In addition, participants described gaps in their health literacy related to the specifics of foot ulcer progression and the appropriate management strategies to prevent amputation. Most participants did not have a solid understanding of warning signs for when medical care should be secured for foot problems or what type of medical care should be sought. One frustrated participant stated: “If I had gotten better, like a different type of information that they could’ve given me, that might’ve helped me improve this ulcer to be going away. From what I have been given, you know, it’s just hard. I don’t know if it’s my foot itself or if it’s the medication. I don’t know. I don’t know if I am a unique case, I know there are people out there that have one foot. And they are able to get, probably, their ulcer better” (29-year-old Native female, history of DFU and recurrent foot infection).

Insurance coverage

While all participants had medical care coverage under Medicaid, Medicare, Indian Health Services or commercial insurance, the majority described significant medical expenses and financial strain related to their diabetes care in general, and in many cases to DFU care in particular. Most of the participants reported multiple recurring expenses such as medications (particularly insulin), co-payments for specialist visits and procedures, and the need for extensive travel, a financial strain that was frequently exacerbated by temporary or permanent loss of employment and under-employment. One participant said that following his second toe amputation: “I was in the hospital for 15 days, 13 days. They are charging me a copay, but I don’t have money to pay it. I am currently not working. I have social security and they don’t give me very much and it’s not enough to cover the copay.” (67-year-old Hispanic male, commercial insurance). In addition, many described substantial out-of-pocket payments for ancillary supplies, such as diabetic footwear and wound dressings due to inadequate insurance coverage, which often resulted in participants being unable to secure the supplies and care they needed for optimal DFU management. For example, a participant explained: “They want me to get diabetic shoes and the orthotic but at the time I didn’t have Medicaid … and with the deductible, they wanted $1,000 for the pair of shoes and the orthotic and I couldn’t afford it.” (45-year-old White female, Medicaid).

Interpersonal Level of Influence

Patient–clinician relationships.

Participants reported a wide array of levels of satisfaction with their medical providers, from long-standing personal and medically supportive relationships to negative experiences of not being listened to or being bounced from provider to provider. A predominant theme involved fragmented relationships with healthcare providers due to multiple factors including patients’ changes in residence, transitions in insurance status, providers leaving the area or switching practices, providers’ medical and holiday leave, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the complexity of managing their diabetes and related complications, these interruptions to patient-clinician relationships posed considerable barriers to effective disease management.

In addition, participants mentioned challenges in making timely appointments, and in getting time with their primary care physicians after major clinical events such as hospitalizations. One patient explained: “I had a lot of problems getting in contact with that doctor (primary care doctor). And after, I think it was the first four months after the amputation, and I just kept on trying to contact her… and I would try to call her, and she never returned my calls.” (47-year-old Hispanic male, history of multiple DFUs, foot infection, and toe amputation).

Similar challenges existed around establishing trusting relationships with the nurses that conducted home wound care following DFUs and amputations. This was due in large part to turnover in nursing staff or the rotation of nurses who conducted their home visits. A participant explained: “They [the companies] make a big deal about bringing the nurse in and have them trained on me and then two weeks later, I get a new nurse and redo it.” (45-year-old White female, underwent more than 20 procedures for DFUs).

Lastly, participants reported that the COVID-19 pandemic further intensified this lack of provider continuity due to limited in-person visits. For example, one participant described his struggles to connect with a new endocrinologist during the pandemic, stating: “I see him once and a current situation came up, so I haven’t been able to see him since then. [Due to the pandemic] it has been phone interviews, so, I haven’t really developed any significant rapport with my current endocrinologist.” (41-year-old White male, history of recurrent DFUs and toe amputations).

Community Level of Influence

Availability of services.

Participants commonly reported struggles with getting the medical equipment needed to prevent and manage their DFUs in a timely fashion, including offloading braces, dressing supplies, and therapeutic shoes and insoles. A few noted that the wound supplies provided by the hospital, clinic, or home healthcare companies ran out before their wounds had healed. One participant described maintaining medical supplies as his biggest challenge, saying: “The nurses themselves have been wonderful but their companies have been mainly touch-and-go with maintaining the supplies being delivered at an appropriate time” (41-year-old White male, Medicaid). Despite having prescriptions from physicians and insurance coverage, many participants also faced long waits for securing specialized diabetic shoes from medical supply companies, resulting in delayed or interrupted care. One participant described: "The insoles that I went in for, that they prescribed for me, it took me a long time to get them. Probably like three months after … and then when I got them, they, they were very flimsy, they didn’t last. It took me awhile to get another pair, a better design of the ones that they had” (47-year-old Hispanic male, self-employed, commercial health insurance).

Participants living in rural areas outside of Tucson cited additional challenges in managing their DFUs due to the time, expense, and distance involved in securing the elaborate routines of specialist appointments, routines, medications, and wound care necessary to effectively manage their DFUs. One participant described: “It was a difficulty because I am on the reservation and sometimes the medical things that I would need, like I said, insulin, the IV antibiotics, they wouldn't be able to come out here and do it. If I had lived in a city, then the people would come and get it done.” (38-year-old Native male, Medicare, rural Arizona).

Societal Level of Influence

Quality of care.

Many participants noted insufficient preventative foot care and education prior to DFU onset. Some reported that they did not learn about ulcer prevention until they developed DFUs. For example, one participant stated: “I don’t really remember (doctors) saying anything on ways to prevent other ulcers.” (38-year-old Native male, Medicaid and Indian Health Services). Some participants similarly reported that they did not receive routine foot examinations prior to developing their first DFU, even though they had regularly scheduled primary care appointments. One explained: “Well, early on they didn’t look at my feet. Before I got the ulcer, they didn’t look at them. They would just instruct me to check my blood sugar. But then after the ulcer and when they cut off my toe, that’s when they started to check my feet.” (67-year-old Hispanic male, commercial insurance).

Other barriers presented themselves while seeking adequate medical care for their new ulcers. Participants initially sought care from a variety of different venues— primary care doctors, podiatrists, specialists, emergency rooms, and urgent care clinics— as determined by how serious they interpreted their foot problems and insurance status and access issues. Some participants had the experience of being sent to multiple facilities in search of appropriate care, and those living in rural areas faced travel to different cities or towns. For example, a participant recalled that: “I went to the ER down here in XXX (a community hospital) and that was Friday (was discharged home) and then I saw my doctor on Monday and he sent me to XXX (a tertiary hospital) in Tucson.” (41-year-old White male, history of multiple DFUs and two toe amputations).

Many respondents experienced initial misdiagnoses and delays in receiving care. This included a few participants who presented for diabetic foot complications to acute care facilities, such as urgent care clincs and emergency rooms, and were sent home without an appropriate diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. One woman recalled her frustrating journey that led to amputation:

‘I called my doctor…. She told me I want you to see an infectious disease doctor and have them put you on an IV antibiotic …. So, I get to the infectious disease doctor, and he says, ‘I’m not going to put you on antibiotic, it isn’t infected.’ So, that’s how I ended up with an amputation because he did not put me on any antibiotic. So, I went into the hospital, and they assigned me an infectious disease doctor and she came in, I’ll never forget this, and she started talking to me like I was stupid, and she goes, ‘You know you’re diabetic, you should’ve gone to a doctor right away ...’ And I said, ‘… hold on a second here, I am a very intelligent person and yes, I did, I went to my own doctor who made an appointment for me to see an infectious disease doctor.” (71-year-old White female, history of multiple DFUs and toe amputations)

Over the past two decades, substantial advances in diabetes therapy have greatly extended health and reduced morbidity. However, as evidenced in this article, significant obstacles to effective DFU treatment and management remain at multiple levels of the healthcare system. Some of these obstacles can be mitigated with more thoughtful education and alignment of access points to receive adequate health care. In this context we offer observations from our study to help address these deficits, particularly as they relate to decreasing notable health disparities.

An important individual level barrier is deficits in health literacy surrounding appropriate terminology to describe diabetic foot complications and how to make informed medical decisions about when to seek medical intervention [ 25 ]. Our findings suggest that a more aggressive and tailored education approach that guides patients to act quickly in seeking medical care and for rapid wound examination is warranted. Part of this education needs to emphasize that diabetes increases the infection and amputation risks of these seemingly “minor” foot injuries. Burdensome expenses related to DFU care posed a second individual level barrier, suggesting the need for continued advocacy for full coverage of DFU care among safety net insurance providers [ 26 , 27 ].

On the interpersonal level, our data illustrate that disruptions to the patient-clinician relationship damages rapport with patients and hinders optimal DFU care. Study participants frequently reported difficulties in accessing appropriate health care providers and disruptions to the patient-physician relationship due to the turnover of providers, changes to region and insurance status, and other factors. This gap calls for developing solutions to address medical provider shortages and to “fill in” health care assessment in a timely manner. One potential approach is to expand the use of trained community health workers who can help triage persons with differing levels of foot ulcers to available health care providers who work outside of the patient’s known environment [ 28 , 29 ].

On the community level, despite having appropriate prescriptions and insurance coverage, participants described significant challenges receiving medical equipment, which was often perceived to be due to shortcomings at the medical supply companies. Since most persons with diabetes see their pharmacist more frequently than any other member of their health care team, developing collaborations between pharmacies, providers, or healthcare system in which pharmacists take on the role of providing medical equipment such as wound care supplies or diabetic shoes, may be an effective approach. Pharmacist supported diabetes care has been shown to be well received by minority patients and to result in improved diabetes outcomes [ 30 , 31 ].

Finally, on the societal level, there is a need to improve preventive care for DFUs on the primary care physician level, a crucial strategy for limb salvage. The American Diabetes Association recommends that all patients with diabetes have their feet inspected at each doctor visit and have a comprehensive foot evaluation at least annually to identify risk factors for DFUs [ 32 ]. Greater focus needs to be placed on educating medical providers and patients, and on the importance of preventive foot care including self-foot inspection, foot examination by a medical professional, and the use of appropriate footwear. In addition, given that sample participants commonly reported receiving misdiagnoses and delays after seeking medical care for DFUs, a standardized protocol and care pathway for when, where, and how patients should seek initial DFU care and how the DFUs should be treated are imperative. Because delays occur both before and after seeking care, a focus must be made to educate both patients and providers about the standard protocol [ 33 ].

There are limitations to this study which should be considered when interpreting the results. Given the relatively modest sample size, we were not able to analyze the data for gender or age effects or by duration of diabetes. Nonetheless, this hard to reach patient sample representing a diverse population did offer very similar stories about the experiences and health disparities they faced in dealing with DFUs.

Diabetic foot ulceration remains a common and life-altering disease complication and one that disproportionately burdens people of racial and ethnic minority status, low socio-economic status, low insurance coverage, and those residing in rural areas. Our study examined the lived experience of a sample of persons with diabetes that face significant barriers at all levels of the healthcare system. Their stories highlight the importance of selecting multiple points of entry to make significant improvements in peoples’ health literacy, relationships with providers, and access to quality and effective medical care, services, and medical supplies. Moreover, this approach should creatively incorporate multiple possible modes of service delivery, including the integration of community health workers and pharmacists. While there are considerable challenges to achieving this goal, concerted efforts are needed to reduce DFUs’ devastating effects on mortality and morbidity and the inequitable burden of poorly managed diabetes foot care among highly affected populations.

Availability of data and materials

The de-identified qualitative data that support the findings of this study are available from corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(24):2367–75.

Article Google Scholar

Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2005;293(2):217–28.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hoffstad O, Mitra N, Walsh J, Margolis DJ. Diabetes, lower-extremity amputation, and death. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1852–7.

Walsh JW, Hoffstad OJ, Sullivan MO, Margolis DJ. Association of diabetic foot ulcer and death in a population-based cohort from the United Kingdom. Diabet Med. 2016;33(11):1493–8.

Mayfield JA, Reiber GE, Sanders LJ, Janisse D, Pogach LM. Preventive foot care in people with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(12):2161–77.

Ratliff HT, Shibuya N, Jupiter DC. Minor vs. major leg amputation in adults with diabetes: Six-month readmissions, reamputations, and complications. J Diabetes Complications. 2021;35(5):107886.

Rice JB, Desai U, Cummings AK, Birnbaum HG, Skornicki M, Parsons NB. Burden of diabetic foot ulcers for medicare and private insurers. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(3):651–8.

Tan TW, Armstrong DG, Concha-Moore KC, et al. Association between race/ethnicity and the risk of amputation of lower extremities among medicare beneficiaries with diabetic foot ulcers and diabetic foot infections. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8(1):e001328.

Tan TW, Shih CD, Concha-Moore KC, et al. Disparities in outcomes of patients admitted with diabetic foot infections. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0211481.

Margolis DJ, Malay DS, Hoffstad OJ, et al. Incidence of diabetic foot ulcer and lower extremity amputation among Medicare beneficiaries, 2006 to 2008: Data Points #2. In: Data Points Publication Series. Rockville (MD) 2011.

Skrepnek GH, Mills JL, Armstrong DG. A Diabetic Emergency One Million Feet Long: Disparities and Burdens of Illness among Diabetic Foot Ulcer Cases within Emergency Departments in the United States, 2006–2010. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134914.

Arya S, Binney Z, Khakharia A, et al. Race and Socioeconomic Status Independently Affect Risk of Major Amputation in Peripheral Artery Disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(2):e007425.

Eslami MH, Zayaruzny M, Fitzgerald GA. The adverse effects of race, insurance status, and low income on the rate of amputation in patients presenting with lower extremity ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(1):55–9.

Lefebvre KM, Chevan J. The persistence of gender and racial disparities in vascular lower extremity amputation: an examination of HCUP-NIS data (2002–2011). Vasc Med. 2015;20(1):51–9.

Lefebvre KM, Lavery LA. Disparities in amputations in minorities. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1941–50.

Lefebvre KM, Metraux S. Disparities in level of amputation among minorities: implications for improved preventative care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(7):649–55.

PubMed Google Scholar

Skrepnek GH, Mills JL, Lavery LA, Armstrong DG. Health Care Service and Outcomes Among an Estimated 6.7 Million Ambulatory Care Diabetic Foot Cases in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(7):936–42.

Isa D, Pace D. Is ethnicity an appropriate measure of health care marginalization? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the outcomes of diabetic foot ulceration in Aboriginal populations. Can J Surg. 2021;64(5):E476–83.

Carr D, Kappagoda M, Boseman L, Cloud LK, Croom B. Advancing Diabetes-Related Equity Through Diabetes Self-Management Education and Training: Existing Coverage Requirements and Considerations for Increased Participation. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2020;26 Suppl 2, Advancing Legal Epidemiology:S37-S44.

Sutherland BL, Pecanac K, Bartels CM, Brennan MB. Expect delays: poor connections between rural and urban health systems challenge multidisciplinary care for rural Americans with diabetic foot ulcers. J Foot Ankle Res. 2020;13(1):32.

Stevens CD, Schriger DL, Raffetto B, Davis AC, Zingmond D, Roby DH. Geographic clustering of diabetic lower-extremity amputations in low-income regions of California. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(8):1383–90.

NIMHD Research Framework. National Institute on Minority Helath and Health Disparities Web site. https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/research-framework/ . Published 2017. Accessed 22 Jan 2022.

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–44.

Alvidrez J, Castille D, Laude-Sharp M, Rosario A, Tabor D. The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S1):S16–20.

Crocker RT, T-W. Palmer, KNB. Marrero, DG. . The Patient’s Perspective of Diabetic Foot Ulceration: A Phenomenological Exploration of Causes, Detection, and Care-Seeking. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(8):2482–94.

Fayfman M, Schechter MC, Amobi CN, et al. Barriers to diabetic foot care in a disadvantaged population: a qualitative assessment. J Diabetes Complications. 2020;34(12):107688.

Schaper NC, Apelqvist J, Bakker K. Reducing lower leg amputations in diabetes: a challenge for patients, healthcare providers and the healthcare system. Diabetologia. 2012;55(7):1869–72.

Collinsworth AW, Vulimiri M, Schmidt KL, Snead CA. Effectiveness of a community health worker-led diabetes self-management education program and implications for CHW involvement in care coordination strategies. Diabetes Educ. 2013;39(6):792–9.

Rosenthal EL, Wiggins N, Ingram M, Mayfield-Johnson S, De Zapien JG. Community health workers then and now: an overview of national studies aimed at defining the field. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34(3):247–59.

Smith M. Pharmacists’ role in improving diabetes medication management. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3(1):175–9.

Nabulsi NA, Yan CH, Tilton JJ, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Clinical pharmacists in diabetes management: What do minority patients with uncontrolled diabetes have to say? J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(5):708–15.

American Diabetes A. 10 Microvascular Complications and Foot Care: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl 1):S105–18.

Sanders AP, Stoeldraaijers LG, Pero MW, Hermkes PJ, Carolina RC, Elders PJ. Patient and professional delay in the referral trajectory of patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;102(2):105–11.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Our team acknowledge the participants of the study.

The project is supported by a National Institute of Diabetes and Kidney Disease K23 Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (1K23DK122126) and a Society of Vascular Surgery Foundation Mentored Research Career Development Award Program (T-W.T) and a National Institute of Diabetes and Kidney Disease R01 (1R01124789) Award (D.G.A).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Southwestern Academic Limb Salvage Alliance (SALSA), Los Angeles, Tucson, USA

Tze-Woei Tan & David G. Armstrong

Division of Vascular Surgery and Endovascular Therapy, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, 1520 San Pablo Street, Ste 4300, Los Angeles, CA, 90033, USA

Center for Health Disparities Research (CHDR), University of Arizona Health Sciences, Tucson, AZ, USA

Rebecca M. Crocker, Kelly N. B. Palmer & David G. Marrero

University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, AZ, USA

Chris Gomez

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Tze-Woei Tan: Conceptualization, Methology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. Rebecca M. Crocker: Conceptualization, Methology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Kelly N.B. Palmer: Conceptualization, Methology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing. Chris Gomez: Methology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. David G. Armstrong: Conceptualization, Methology, Writing – Review & Editing. David G. Marrero: Conceptualization, Methology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tze-Woei Tan .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The University of Arizona Institutional Review Board approved the study in July 2019 (Protocol Number 1906749805). All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors haves no related conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tan, TW., Crocker, R.M., Palmer, K.N.B. et al. A qualitative study of barriers to care-seeking for diabetic foot ulceration across multiple levels of the healthcare system. J Foot Ankle Res 15 , 56 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-022-00561-4

Download citation

Received : 24 May 2022

Accepted : 22 July 2022

Published : 06 August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-022-00561-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Diabetic foot complications

- Foot ulceration

- Barriers in assessing medical care

- Health care system barriers

- Qualitative

Journal of Foot and Ankle Research

ISSN: 1757-1146

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Frontiers in Endocrinology

- Clinical Diabetes

- Research Topics

Improving Outcomes in Diabetic Foot Care - A Worldwide Perspective

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

Enhanced population longevity, decrease in physical activity and the obesity pandemic have resulted in an increase in incidence of type 2 diabetes in all WHO health care areas. The prevalence of the condition has been further increased by an increase in life expectancy of those living with both type 1 and ...

Keywords : Diabetic Foot, Diabetic Foot Ulcers, Diabetic Foot Infections, Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis, Lower limb amputation, Peripheral arterial disease, Diabetes peripheral neuropathy, Charcot Foot, Diabetic Foot Prevention, Therapeutic Shoes, Wound healing

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

Research advances in hydrogel-based wound dressings for diabetic foot ulcer treatment: a review

- Published: 05 May 2024

- Volume 59 , pages 8059–8084, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Jie Zhao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9006-0004 1 , 2 ,

- Jie Liu 3 ,

- Yuxin Hu 1 , 2 ,

- Wanxuan Hu 4 ,

- Juan Wei 5 ,

- Haisheng Qian 6 &

- Yexiang Sun 4

141 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are one of the most challenging and prevalent refractory wounds associated with diabetes mellitus. It is characterized with long courses, high recurrence and disability rates. Hydrogel-based wound dressings have been demonstrated an effective and promising strategy for treating diabetic wounds. However, the complexity of the pathogenesis and microenvironment in diabetic wounds have restricted both the experts in functional hydrogels and clinicians. The former had no inspiration for clinical demands in the design process, and the latter was confused about clinical use because they knew little about the tremendous potential of the functional hydrogels. Here, important targets for DFUs treatment were listed, and effective products underlying the molecular pathogenesis were suggested for the designer. Then, the application of hydrogels into DFUs were classified in accordance with their functional targets and active ingredients. Hence, it is very convenient for clinicians to make a perfect option for different wounds. Finally, research gaps and future prospects for wound-healing hydrogels were presented. We envision that this review can inspire creativity and innovation in the development of hydrogel-based wound dressings for diabetic foot ulcer treatment.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Injectable carrier hydrogel for diabetic foot ulcer wound repair

Research advances in smart responsive-hydrogel dressings with potential clinical diabetic wound healing properties

Advanced polymer hydrogels that promote diabetic ulcer healing: mechanisms, classifications, and medical applications

Availability of data and materials.

Not applicable.

American Diabetes A (2020) 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 43(Suppl 1):S14–S31. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-S002

Article Google Scholar

Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S et al (2022) IDF diabetes atlas: global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 183:109119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Armstrong DG, Swerdlow MA, Armstrong AA et al (2020) Five year mortality and direct costs of care for people with diabetic foot complications are comparable to cancer. J Foot Ankle Res 13(1):16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-020-00383-2

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA (2017) Diabetic foot ulcers and their recurrence. N Engl J Med 376(24):2367–2375. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1615439

Reardon R, Simring D, Kim B et al (2020) The diabetic foot ulcer. Aust J Gen Pract 49(5):250–255. https://doi.org/10.31128/AJGP-11-19-5161

Huang ZH, Li SQ, Kou Y et al (2019) Risk factors for the recurrence of diabetic foot ulcers among diabetic patients: a meta-analysis. Int Wound J 16(6):1373–1382. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13200

Chamberlain RC, Fleetwood K, Wild SH et al (2022) Foot ulcer and risk of lower limb amputation or death in people with diabetes: a national population-based retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 45(1):83–91. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-1596

Bandyk DF (2018) The diabetic foot: pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment. Semin Vasc Surg 31(2–4):43–48. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2019.02.001

Francia P, Gualdani E, Policardo L et al (2022) Mortality risk associated with diabetic foot complications in people with or without history of diabetic foot hospitalizations. J Clin Med 11(9):2454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11092454

Dogruel H, Aydemir M, Balci MK (2022) Management of diabetic foot ulcers and the challenging points: an endocrine view. World J Diabetes 13(1):27–36. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v13.i1.27

Schaper NC, van Netten JJ, Apelqvist J et al (2020) Practical Guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetic foot disease (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 36(Suppl 1):e3266. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3266

Falanga V (2005) Wound healing and its impairment in the diabetic foot. Lancet 366(9498):1736–1743. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67700-8

Ryall C, Duarah S, Chen S et al (2022) Advancements in skin delivery of natural bioactive products for wound management: a brief review of two decades. Pharmaceutics 14(5):1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14051072

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ongarora BG (2022) Recent technological advances in the management of chronic wounds: a literature review. Health Sci Rep 5(3):e641. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.641

Hunt TK, Hopf HW (1997) Wound healing and wound infection. What surgeons and anesthesiologists can do. Surg Clin North Am 77(3):587–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70570-3

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Stadelmann WK, Digenis AG, Tobin GR (1998) Physiology and healing dynamics of chronic cutaneous wounds. Am J Surg 176(2A Suppl):26S-38S. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00183-4

Undas A, Wiek I, Stepien E et al (2008) Hyperglycemia is associated with enhanced thrombin formation, platelet activation, and fibrin clot resistance to lysis in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Diabetes Care 31(8):1590–1595. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-0282

Al SH (2022) Macrophage phenotypes in normal and diabetic wound healing and therapeutic interventions. Cells 11(15):2430. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11152430

Article CAS Google Scholar

Peng Y, Xiong RP, Zhang ZH et al (2021) Ski promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in fibroblasts under high-glucose conditions via the FoxO1 pathway. Cell Prolif 54(2):e12971. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpr.12971

Hu SC, Lan CE (2016) High-glucose environment disturbs the physiologic functions of keratinocytes: focusing on diabetic wound healing. J Dermatol Sci 84(2):121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.07.008

Wei F, Wang A, Wang Q et al (2020) Plasma endothelial cells-derived extracellular vesicles promote wound healing in diabetes through YAP and the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Aging (Albany NY) 12(12):12002–12018. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.103366

Nie X, Zhang H, Shi X et al (2020) Asiaticoside nitric oxide gel accelerates diabetic cutaneous ulcers healing by activating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 79:106109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106109

Geng K, Ma X, Jiang Z et al (2023) WDR74 facilitates TGF-beta/Smad pathway activation to promote M2 macrophage polarization and diabetic foot ulcer wound healing in mice. Cell Biol Toxicol 39(4):1577–1591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10565-022-09748-8

Yang Y, Zhang B, Yang Y et al (2022) FOXM1 accelerates wound healing in diabetic foot ulcer by inducing M2 macrophage polarization through a mechanism involving SEMA3C/NRP2/Hedgehog signaling. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 184:109121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109121