- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Martin Luther and the 95 Theses

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2019 | Original: October 29, 2009

Born in Eisleben, Germany, in 1483, Martin Luther went on to become one of Western history’s most significant figures. Luther spent his early years in relative anonymity as a monk and scholar. But in 1517 Luther penned a document attacking the Catholic Church’s corrupt practice of selling “indulgences” to absolve sin. His “95 Theses,” which propounded two central beliefs—that the Bible is the central religious authority and that humans may reach salvation only by their faith and not by their deeds—was to spark the Protestant Reformation. Although these ideas had been advanced before, Martin Luther codified them at a moment in history ripe for religious reformation. The Catholic Church was ever after divided, and the Protestantism that soon emerged was shaped by Luther’s ideas. His writings changed the course of religious and cultural history in the West.

Martin Luther (1483–1546) was born in Eisleben, Saxony (now Germany), part of the Holy Roman Empire, to parents Hans and Margaretta. Luther’s father was a prosperous businessman, and when Luther was young, his father moved the family of 10 to Mansfeld. At age five, Luther began his education at a local school where he learned reading, writing and Latin. At 13, Luther began to attend a school run by the Brethren of the Common Life in Magdeburg. The Brethren’s teachings focused on personal piety, and while there Luther developed an early interest in monastic life.

Did you know? Legend says Martin Luther was inspired to launch the Protestant Reformation while seated comfortably on the chamber pot. That cannot be confirmed, but in 2004 archeologists discovered Luther's lavatory, which was remarkably modern for its day, featuring a heated-floor system and a primitive drain.

Martin Luther Enters the Monastery

But Hans Luther had other plans for young Martin—he wanted him to become a lawyer—so he withdrew him from the school in Magdeburg and sent him to new school in Eisenach. Then, in 1501, Luther enrolled at the University of Erfurt, the premiere university in Germany at the time. There, he studied the typical curriculum of the day: arithmetic, astronomy, geometry and philosophy and he attained a Master’s degree from the school in 1505. In July of that year, Luther got caught in a violent thunderstorm, in which a bolt of lightning nearly struck him down. He considered the incident a sign from God and vowed to become a monk if he survived the storm. The storm subsided, Luther emerged unscathed and, true to his promise, Luther turned his back on his study of the law days later on July 17, 1505. Instead, he entered an Augustinian monastery.

Luther began to live the spartan and rigorous life of a monk but did not abandon his studies. Between 1507 and 1510, Luther studied at the University of Erfurt and at a university in Wittenberg. In 1510–1511, he took a break from his education to serve as a representative in Rome for the German Augustinian monasteries. In 1512, Luther received his doctorate and became a professor of biblical studies. Over the next five years Luther’s continuing theological studies would lead him to insights that would have implications for Christian thought for centuries to come.

Martin Luther Questions the Catholic Church

In early 16th-century Europe, some theologians and scholars were beginning to question the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. It was also around this time that translations of original texts—namely, the Bible and the writings of the early church philosopher Augustine—became more widely available.

Augustine (340–430) had emphasized the primacy of the Bible rather than Church officials as the ultimate religious authority. He also believed that humans could not reach salvation by their own acts, but that only God could bestow salvation by his divine grace. In the Middle Ages the Catholic Church taught that salvation was possible through “good works,” or works of righteousness, that pleased God. Luther came to share Augustine’s two central beliefs, which would later form the basis of Protestantism.

Meanwhile, the Catholic Church’s practice of granting “indulgences” to provide absolution to sinners became increasingly corrupt. Indulgence-selling had been banned in Germany, but the practice continued unabated. In 1517, a friar named Johann Tetzel began to sell indulgences in Germany to raise funds to renovate St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

The 95 Theses

Committed to the idea that salvation could be reached through faith and by divine grace only, Luther vigorously objected to the corrupt practice of selling indulgences. Acting on this belief, he wrote the “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences,” also known as “The 95 Theses,” a list of questions and propositions for debate. Popular legend has it that on October 31, 1517 Luther defiantly nailed a copy of his 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle church. The reality was probably not so dramatic; Luther more likely hung the document on the door of the church matter-of-factly to announce the ensuing academic discussion around it that he was organizing.

The 95 Theses, which would later become the foundation of the Protestant Reformation, were written in a remarkably humble and academic tone, questioning rather than accusing. The overall thrust of the document was nonetheless quite provocative. The first two of the theses contained Luther’s central idea, that God intended believers to seek repentance and that faith alone, and not deeds, would lead to salvation. The other 93 theses, a number of them directly criticizing the practice of indulgences, supported these first two.

In addition to his criticisms of indulgences, Luther also reflected popular sentiment about the “St. Peter’s scandal” in the 95 Theses:

Why does not the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with his own money rather than with the money of poor believers?

The 95 Theses were quickly distributed throughout Germany and then made their way to Rome. In 1518, Luther was summoned to Augsburg, a city in southern Germany, to defend his opinions before an imperial diet (assembly). A debate lasting three days between Luther and Cardinal Thomas Cajetan produced no agreement. Cajetan defended the church’s use of indulgences, but Luther refused to recant and returned to Wittenberg.

Luther the Heretic

On November 9, 1518 the pope condemned Luther’s writings as conflicting with the teachings of the Church. One year later a series of commissions were convened to examine Luther’s teachings. The first papal commission found them to be heretical, but the second merely stated that Luther’s writings were “scandalous and offensive to pious ears.” Finally, in July 1520 Pope Leo X issued a papal bull (public decree) that concluded that Luther’s propositions were heretical and gave Luther 120 days to recant in Rome. Luther refused to recant, and on January 3, 1521 Pope Leo excommunicated Martin Luther from the Catholic Church.

On April 17, 1521 Luther appeared before the Diet of Worms in Germany. Refusing again to recant, Luther concluded his testimony with the defiant statement: “Here I stand. God help me. I can do no other.” On May 25, the Holy Roman emperor Charles V signed an edict against Luther, ordering his writings to be burned. Luther hid in the town of Eisenach for the next year, where he began work on one of his major life projects, the translation of the New Testament into German, which took him 10 months to complete.

Martin Luther's Later Years

Luther returned to Wittenberg in 1521, where the reform movement initiated by his writings had grown beyond his influence. It was no longer a purely theological cause; it had become political. Other leaders stepped up to lead the reform, and concurrently, the rebellion known as the Peasants’ War was making its way across Germany.

Luther had previously written against the Church’s adherence to clerical celibacy, and in 1525 he married Katherine of Bora, a former nun. They had five children. At the end of his life, Luther turned strident in his views, and pronounced the pope the Antichrist, advocated for the expulsion of Jews from the empire and condoned polygamy based on the practice of the patriarchs in the Old Testament.

Luther died on February 18, 1546.

Significance of Martin Luther’s Work

Martin Luther is one of the most influential figures in Western history. His writings were responsible for fractionalizing the Catholic Church and sparking the Protestant Reformation. His central teachings, that the Bible is the central source of religious authority and that salvation is reached through faith and not deeds, shaped the core of Protestantism. Although Luther was critical of the Catholic Church, he distanced himself from the radical successors who took up his mantle. Luther is remembered as a controversial figure, not only because his writings led to significant religious reform and division, but also because in later life he took on radical positions on other questions, including his pronouncements against Jews, which some have said may have portended German anti-Semitism; others dismiss them as just one man’s vitriol that did not gain a following. Some of Luther’s most significant contributions to theological history, however, such as his insistence that as the sole source of religious authority the Bible be translated and made available to everyone, were truly revolutionary in his day.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Print Edition

- Medieval History

- Early Modern History

- Modern History

- History at York

- Book Reviews

- Film Reviews

- Museum Reviews

- Article Guidelines

The York Historian

What was the significance of the 95 theses.

What were the 95 Theses?

According to historic legend, Martin Luther posted a document on the door of the Wittenberg Church on the 31 st October 1517; a document later referred to as the 95 Theses. This document was questioning rather than accusatory, seeking to inform the Archbishop of Mainz that the selling of indulgences had become corrupt, with the sellers seeking solely to line their own pockets. It questioned the idea that the indulgences trade perpetuated – that buying a trinket could shave time off the stay of one’s loved ones in purgatory, sending them to a glorious Heaven.

It is important, however, to recognise that this was not the action of a man wanting to break away from the Catholic Church. When writing the 95 Theses, Luther simply intended to bring reform to the centre of the agenda for the Church Council once again; it cannot be stressed enough that he wanted to reform, rather than abandon, the Church.

Nonetheless, the 95 Theses were undoubtedly provocative, leading to debates across the German Lands about what it meant to be a true Christian, with some historians considering the document to be the start of the lengthy process of the Reformation. But why did Luther write them?

Why did Luther write the 95 Theses?

In particular, Luther was horrified by the fact that a large portion of the profits from this trade were being used to renovate St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. His outrage at this is evident from the 86 th thesis: ‘Why does the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St Peter with the money of the poor rather than with his own money?’ Perhaps this is indicative of Luther’s opinion as opposing the financial extortion indulgences pressed upon the poor, rather than the theology which lay behind the process of freeing one’s loved ones from purgatory.

It is interesting to note that Luther also sent a copy of his 95 Theses directly to Archbishop Albrecht von Brandenburg. It appears that he legitimately believed that the Archbishop was not aware of the corruption inherent in the indulgence trade led by Tetzel. This is something which can be considered important later on, for it indicates that Luther did not consider the Church hierarchy redundant at this point.

Why were the 95 Theses significant?

Though the document itself has a debateable significance, the events which occurred because of its publication were paramount in Luther’s ideological and religious development. Almost immediately there was outrage at the ‘heresy’ which the Church viewed as implicit within the document. Despite the pressure upon Luther to immediately recant his position, he did not. This in part led to the Leipzig debate in summer 1519 with Johann Eck.

This debate forced Luther to clarify some of his theories and doctrinal stances against the representative of the Catholic Church. The debate focused largely on doctrine; in fact, the debate regarding indulgences was only briefly mentioned in the discussions between the two men. This seems surprising; Luther’s primary purpose in writing the 95 Theses was to protest the selling of indulgences. Why was this therefore not the primary purpose of the debate?

Ultimately the debate served to further Luther’s development of doctrine which opposed the traditional view of the Catholic Church. In the debate he was forced to conclude that Church Councils had the potential to be erroneous in their judgements. This therefore threw into dispute the papal hierarchy’s authority, and set him on his path towards evangelicalism and the formulation of the doctrine of justification by faith alone. Yet it is important to bear in mind that, had the pope offered a reconciliation, Luther would have returned to the doctrine of the established Church.

An interesting point to consider about the aftermath of the 95 Theses is the attitude of the Catholic Church. It immediately sought to identify Luther as someone who had strayed from the true way and was therefore a heretic; it refused to recognise that Luther had valid complaints which were shared by many across Western Christendom. The 95 Theses could have been taken at face value and used as an avenue to reform, as Luther intended. Instead, the papal hierarchy sought to discredit Luther, and keep to the status quo.

What made the 95 Theses significant?

A document written in Latin and posted on a door like most other academic debates, it does not seem obvious when considering the 95 Theses alone to see just how they became as significant as they did.

The translation of the Latin text into German also helped make the document significant. Translated in early 1518 by reformist friends of Luther, this widened the debate’s appeal simply because it made the subject matter accessible to a greater number of people. ‘Common’ folk who could read would have been able to read in German, rather than Latin. This therefore meant that they would be able to read the article for themselves and realise just how many of the arguments they identified with (or did not identify with, for that matter). The translation also meant that these literate folk could read the Theses aloud to a large audience; Bob Scribner argued that we should not forget the oral nature of the Reformation, beginning with one of the most divisive documents in history.

Finally, the 95 Theses can be considered significant because they were expressing sentiments that many ordinary folk felt themselves at the time. There had been a disillusionment with the Church and corruption within it for a great deal of time; the Reformatio Sigismundi of 1439 is a prime early example of a series of lists detailing the concerns of the people about the state of the Church. By the time of the Imperial Diet of Worms in 1521, there were 102 grievances with the Church, something overshadowed due to Martin Luther’s presence at this Diet. Many of the issues Luther highlighted were shared among the populace; it was due to the contextual factors of the printing press and the use of the German language that made this expression so significant.

It would not be surprising if, when posting his 95 Theses on the door of the chapel on the 31 st October 1517, Luther did not expect a great deal to change. At the time, he did not know what such an act would lead to. The events which occurred due to the Theses led to Luther clarifying his doctrinal position in a manner which led to his eventual repudiation of the decadence and corruption within the Catholic Church and his excommunication.

Yet we must remember that whilst the 95 Theses can be considered to constitute an extraordinary shift in the mentality of a disillusioned Christian, they are very unlikely to have achieved the same significance without the printing press. If the 95 Theses had been posted on the 31 st October 1417 , would the result have been the same?

Written by Victoria Bettney

Bibliography

Dixon, Scott C. The Reformation in Germany . Oxford : Blackwell, 2002.

Dixon, Scott C ed. The German Reformation: The Essential Readings . Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.

Lau, Franz and Bizer, Ernst. A History of the Reformation in Germany To 1555 . Translated by Brian Hardy. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1969.

Lindberg, Carter. The European Reformations . Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

McGrath, Alister. Christian Theology: An Introduction . Oxford: Blackwell, 2007.

McGrath, Alister. Reformation Thought: An Introduction. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1998.

Scribner, Robert. ‘Oral Culture and the Diffusion of Reformation Ideas,’ History of European Ideas 5, no. 3 (1984): 237-256.

“The 95 Theses,” http://www.luther.de/en/95thesen.html , accessed 29.10.15

Share this:

Post navigation, 3 thoughts on “ what was the significance of the 95 theses ”.

Interesting article! You rightly argue that the Theses were not the finished product but just a step in Luther’s theological development. That makes you think; should we really be celebrating 31 October 2017 as the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, or should we be remembering a different date?

Like Liked by 1 person

hit the griddy

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Search for:

YAYAS’ York Historian

Subscribe to the york historian.

Enter your email address to follow The York Historian and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

- View TheYorkHistorian’s profile on Facebook

- View TYorkHistorian’s profile on Twitter

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.com

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Our Ministry

- The Gap We See

- Partner with Us

- Newsletters

- Partner With Us

- Help & Info

- New Believers

- Young Adult

- CT Current Issues

- CT Marriage & Family

- CT Spiritual Formation

- CT Theology

- Single Session

- Old Testament

- New Testament

- Bible Study Basics

- LifeGuide Studies

- Great Teachers of the Bible

- Apocalyptic

- General Letters

- Paul's Letters

- Law & Narrative

- Bible Characters

- Spiritual Formation

- Church Life

- Christian History

- Overcoming Sins

- Health & Life

- Sex & Marriage

- Mental Health

- Movie Discussion Guides

- Christians in Culture

- Advent & Christmas

- Lent & Easter

- Thanksgiving

- Fourth of July

What did Luther actually say in the 95 Theses that sparked the Protestant Reformation?

Martin Luther's 95 Theses are often considered a charter, a bold declaration of independence for the Protestant church.

But when he wrote nearly 100 points of debate in Latin, Luther was simply inviting fellow academics to a "Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences," the theses' official title. (The debate never was held, because the theses were translated into German and distributed widely, creating an uproar.)

What were indulgences? In the sacrament of penance, Christians confessed sins and found absolution for them. The process of penance involved satisfaction —paying the temporal penalty for those sins. Under certain circumstances, someone who was truly contrite and had confessed his sins could receive partial (or, rarely, complete) remission of temporal punishment by purchasing a letter of indulgence.

In the 95 Theses , Luther did not attack the idea of indulgences, for in Thesis 73 he wrote, " … the pope justly thunders against those who by any means whatsoever contrive harm to the sale of indulgences."

But Luther strongly objected to the abuse of indulgences—most recently under the salesmanship of Johann Tetzel. And in the process, Luther, though probably not fully aware of it, knocked down the pillars supporting many practices in medieval Christianity.

Key Statements

Here are 13 samples of Luther's theses:

1. When our Lord and Master, Jesus Christ, says "Repent ye," etc., he means that the entire life of the faithful should be a repentance.

2. This statement cannot be understood of the sacrament of penance, i.e., of confession and satisfaction, which is administered by the priesthood.

27. They preach human folly who pretend that as soon as money in the coffer rings a soul from purgatory springs.

32. Those who suppose that on account of their letters of indulgence they are sure of salvation will be eternally damned along with their teachers.

36. Every Christian who truly repents has plenary [full] forgiveness both of punishment and guilt bestowed on him, even without letters of indulgence.

37. Every true Christian, whether living or dead, has a share in all the benefits of Christ and the Church, for God has granted him these, even without letters of indulgence.

45. Christians should be taught that whoever sees a person in need and, instead of helping him, uses his money for an indulgence, obtains not an indulgence of the pope but the displeasure of God.

51. Christians should be taught that the pope ought and would give his own substance to the poor, from whom certain preachers of indulgences extract money, even if he had to sell St. Peter's Cathedral to do it.

81. This shameless preaching of pardons makes it hard even for learned men to defend the pope's honor against calumny or to answer the indubitably shrewd questions of the laity.

82. For example: "Why does not the pope empty purgatory for the sake of holy love … for after all, he does release countless souls for the sake of sordid money contributed for the building of a cathedral? …"

90. To suppress these very telling arguments of the laity by force instead of answering them with adequate reasons would be to expose the church and the pope to the ridicule of their enemies and to render Christians unhappy.

94. We should admonish Christians to follow Christ, their Head, through punishment, death, and hell.

95. And so let them set their trust on entering heaven through many tribulations rather than some false security and peace.

Within two months, Johann Tetzel fired back with his own theses, including: "Christians should be taught that the Pope, by authority of his jurisdiction, is superior to the entire Catholic Church and its councils, and that they should humbly obey his statutes."

Reprinted from "Protestants' Most-Famous Document," the Editors of ChristianHistory.net . Click here to read the original article and for reprint information.

- Reformation

Free Newsletters

More Newsletters

The 95 Theses , a document written by Martin Luther in 1517, challenged the teachings of the Catholic Church on the nature of penance, the authority of the pope and the usefulness of indulgences. It sparked a theological debate that fueled the Reformation and subsequently resulted in the birth of Protestantism and the Lutheran , Reformed , and Anabaptist traditions within Christianity.

Luther's action was in great part a response to the selling of indulgences by Johann Tetzel, a Dominican priest, commissioned by the Archbishop of Mainz and Pope Leo X. The purpose of this fundraising campaign was to finance the building of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Even though Luther's prince, Frederick the Wise, and the prince of the neighboring territory, George, Duke of Saxony, forbade the sale in their lands, Luther's parishioners traveled to purchase them. When these people came to confession, they presented the plenary indulgence, claiming they no longer had to repent of their sins, since the document promised to forgive all their sins.

Luther is said to have posted the 95 Theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, on October 31, 1517. Church doors functioned very much as bulletin boards function on a twenty-first century college campus. The 95 Theses were quickly translated into German, widely copied and printed. Within two weeks they had spread throughout Germany, and within two months throughout Europe. This was one of the first events in history that was profoundly affected by the printing press, which made the distribution of documents and ideas easier and more wide-spread.

Text of the 95 Theses

**Disputation of Doctor Martin Luther\ on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences

by Dr. Martin Luther, 1517** Out of love for the truth and the desire to bring it to light, the following propositions will be discussed at Wittenberg, under the presidency of the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and of Sacred Theology, and Lecturer in Ordinary on the same at that place. Wherefore he requests that those who are unable to be present and debate orally with us, may do so by letter.

In the Name our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

- Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, when He said Poenitentiam agite, willed that the whole life of believers should be repentance.

- This word cannot be understood to mean sacramental penance, i.e., confession and satisfaction, which is administered by the priests.

- Yet it means not inward repentance only; nay, there is no inward repentance which does not outwardly work divers mortifications of the flesh.

- The penalty [of sin], therefore, continues so long as hatred of self continues; for this is the true inward repentance, and continues until our entrance into the kingdom of heaven.

- The pope does not intend to remit, and cannot remit any penalties other than those which he has imposed either by his own authority or by that of the Canons.

- The pope cannot remit any guilt, except by declaring that it has been remitted by God and by assenting to God's remission; though, to be sure, he may grant remission in cases reserved to his judgment. If his right to grant remission in such cases were despised, the guilt would remain entirely unforgiven.

- God remits guilt to no one whom He does not, at the same time, humble in all things and bring into subjection to His vicar, the priest.

- The penitential canons are imposed only on the living, and, according to them, nothing should be imposed on the dying.

- Therefore the Holy Spirit in the pope is kind to us, because in his decrees he always makes exception of the article of death and of necessity.

- Ignorant and wicked are the doings of those priests who, in the case of the dying, reserve canonical penances for purgatory.

- This changing of the canonical penalty to the penalty of purgatory is quite evidently one of the tares that were sown while the bishops slept.

- In former times the canonical penalties were imposed not after, but before absolution, as tests of true contrition.

- The dying are freed by death from all penalties; they are already dead to canonical rules, and have a right to be released from them.

- The imperfect health [of soul], that is to say, the imperfect love, of the dying brings with it, of necessity, great fear; and the smaller the love, the greater is the fear.

- This fear and horror is sufficient of itself alone (to say nothing of other things) to constitute the penalty of purgatory, since it is very near to the horror of despair.

- Hell, purgatory, and heaven seem to differ as do despair, almost-despair, and the assurance of safety.

- With souls in purgatory it seems necessary that horror should grow less and love increase.

- It seems unproved, either by reason or Scripture, that they are outside the state of merit, that is to say, of increasing love.

- Again, it seems unproved that they, or at least that all of them, are certain or assured of their own blessedness, though we may be quite certain of it.

- Therefore by "full remission of all penalties" the pope means not actually "of all," but only of those imposed by himself.

- Therefore those preachers of indulgences are in error, who say that by the pope's indulgences a man is freed from every penalty, and saved;

- Whereas he remits to souls in purgatory no penalty which, according to the canons, they would have had to pay in this life.

- If it is at all possible to grant to any one the remission of all penalties whatsoever, it is certain that this remission can be granted only to the most perfect, that is, to the very fewest.

- It must needs be, therefore, that the greater part of the people are deceived by that indiscriminate and highsounding promise of release from penalty.

- The power which the pope has, in a general way, over purgatory, is just like the power which any bishop or curate has, in a special way, within his own diocese or parish.

- The pope does well when he grants remission to souls [in purgatory], not by the power of the keys (which he does not possess), but by way of intercession.

- They preach man who say that so soon as the penny jingles into the money-box, the soul flies out [of purgatory].

- It is certain that when the penny jingles into the money-box, gain and avarice can be increased, but the result of the intercession of the Church is in the power of God alone.

- Who knows whether all the souls in purgatory wish to be bought out of it, as in the legend of Sts. Severinus and Paschal.

- No one is sure that his own contrition is sincere; much less that he has attained full remission.

- Rare as is the man that is truly penitent, so rare is also the man who truly buys indulgences, i.e., such men are most rare.

- They will be condemned eternally, together with their teachers, who believe themselves sure of their salvation because they have letters of pardon.

- Men must be on their guard against those who say that the pope's pardons are that inestimable gift of God by which man is reconciled to Him;

- For these "graces of pardon" concern only the penalties of sacramental satisfaction, and these are appointed by man.

- They preach no Christian doctrine who teach that contrition is not necessary in those who intend to buy souls out of purgatory or to buy confessionalia.

- Every truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without letters of pardon.

- Every true Christian, whether living or dead, has part in all the blessings of Christ and the Church; and this is granted him by God, even without letters of pardon.

- Nevertheless, the remission and participation [in the blessings of the Church] which are granted by the pope are in no way to be despised, for they are, as I have said, the declaration of divine remission.

- It is most difficult, even for the very keenest theologians, at one and the same time to commend to the people the abundance of pardons and [the need of] true contrition.

- True contrition seeks and loves penalties, but liberal pardons only relax penalties and cause them to be hated, or at least, furnish an occasion [for hating them].

- Apostolic pardons are to be preached with caution, lest the people may falsely think them preferable to other good works of love.

- Christians are to be taught that the pope does not intend the buying of pardons to be compared in any way to works of mercy.

- Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better work than buying pardons;

- Because love grows by works of love, and man becomes better; but by pardons man does not grow better, only more free from penalty.

- Christians are to be taught that he who sees a man in need, and passes him by, and gives [his money] for pardons, purchases not the indulgences of the pope, but the indignation of God.

- Christians are to be taught that unless they have more than they need, they are bound to keep back what is necessary for their own families, and by no means to squander it on pardons.

- Christians are to be taught that the buying of pardons is a matter of free will, and not of commandment.

- Christians are to be taught that the pope, in granting pardons, needs, and therefore desires, their devout prayer for him more than the money they bring.

- Christians are to be taught that the pope's pardons are useful, if they do not put their trust in them; but altogether harmful, if through them they lose their fear of God.

- Christians are to be taught that if the pope knew the exactions of the pardon-preachers, he would rather that St. Peter's church should go to ashes, than that it should be built up with the skin, flesh and bones of his sheep.

- Christians are to be taught that it would be the pope's wish, as it is his duty, to give of his own money to very many of those from whom certain hawkers of pardons cajole money, even though the church of St. Peter might have to be sold.

- The assurance of salvation by letters of pardon is vain, even though the commissary, nay, even though the pope himself, were to stake his soul upon it.

- They are enemies of Christ and of the pope, who bid the Word of God be altogether silent in some Churches, in order that pardons may be preached in others.

- Injury is done the Word of God when, in the same sermon, an equal or a longer time is spent on pardons than on this Word.

- It must be the intention of the pope that if pardons, which are a very small thing, are celebrated with one bell, with single processions and ceremonies, then the Gospel, which is the very greatest thing, should be preached with a hundred bells, a hundred processions, a hundred ceremonies.

- The "treasures of the Church," out of which the pope grants indulgences, are not sufficiently named or known among the people of Christ.

- That they are not temporal treasures is certainly evident, for many of the vendors do not pour out such treasures so easily, but only gather them.

- Nor are they the merits of Christ and the Saints, for even without the pope, these always work grace for the inner man, and the cross, death, and hell for the outward man.

- St. Lawrence said that the treasures of the Church were the Church's poor, but he spoke according to the usage of the word in his own time.

- Without rashness we say that the keys of the Church, given by Christ's merit, are that treasure;

- For it is clear that for the remission of penalties and of reserved cases, the power of the pope is of itself sufficient.

- The true treasure of the Church is the Most Holy Gospel of the glory and the grace of God.

- But this treasure is naturally most odious, for it makes the first to be last.

- On the other hand, the treasure of indulgences is naturally most acceptable, for it makes the last to be first.

- Therefore the treasures of the Gospel are nets with which they formerly were wont to fish for men of riches.

- The treasures of the indulgences are nets with which they now fish for the riches of men.

- The indulgences which the preachers cry as the "greatest graces" are known to be truly such, in so far as they promote gain.

- Yet they are in truth the very smallest graces compared with the grace of God and the piety of the Cross.

- Bishops and curates are bound to admit the commissaries of apostolic pardons, with all reverence.

- But still more are they bound to strain all their eyes and attend with all their ears, lest these men preach their own dreams instead of the commission of the pope.

- He who speaks against the truth of apostolic pardons, let him be anathema and accursed!

- But he who guards against the lust and license of the pardon-preachers, let him be blessed!

- The pope justly thunders against those who, by any art, contrive the injury of the traffic in pardons.

- But much more does he intend to thunder against those who use the pretext of pardons to contrive the injury of holy love and truth.

- To think the papal pardons so great that they could absolve a man even if he had committed an impossible sin and violated the Mother of God -- this is madness.

- We say, on the contrary, that the papal pardons are not able to remove the very least of venial sins, so far as its guilt is concerned.

- It is said that even St. Peter, if he were now Pope, could not bestow greater graces; this is blasphemy against St. Peter and against the pope.

- We say, on the contrary, that even the present pope, and any pope at all, has greater graces at his disposal; to wit, the Gospel, powers, gifts of healing, etc., as it is written in I. Corinthians xii.

- To say that the cross, emblazoned with the papal arms, which is set up [by the preachers of indulgences], is of equal worth with the Cross of Christ, is blasphemy.

- The bishops, curates and theologians who allow such talk to be spread among the people, will have an account to render.

- This unbridled preaching of pardons makes it no easy matter, even for learned men, to rescue the reverence due to the pope from slander, or even from the shrewd questionings of the laity.

- To wit: -- "Why does not the pope empty purgatory, for the sake of holy love and of the dire need of the souls that are there, if he redeems an infinite number of souls for the sake of miserable money with which to build a Church? The former reasons would be most just; the latter is most trivial."

- Again: -- "Why are mortuary and anniversary masses for the dead continued, and why does he not return or permit the withdrawal of the endowments founded on their behalf, since it is wrong to pray for the redeemed?"

- Again: -- "What is this new piety of God and the pope, that for money they allow a man who is impious and their enemy to buy out of purgatory the pious soul of a friend of God, and do not rather, because of that pious and beloved soul's own need, free it for pure love's sake?"

- Again: -- "Why are the penitential canons long since in actual fact and through disuse abrogated and dead, now satisfied by the granting of indulgences, as though they were still alive and in force?"

- Again: -- "Why does not the pope, whose wealth is to-day greater than the riches of the richest, build just this one church of St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money of poor believers?"

- Again: -- "What is it that the pope remits, and what participation does he grant to those who, by perfect contrition, have a right to full remission and participation?"

- Again: -- "What greater blessing could come to the Church than if the pope were to do a hundred times a day what he now does once, and bestow on every believer these remissions and participations?"

- "Since the pope, by his pardons, seeks the salvation of souls rather than money, why does he suspend the indulgences and pardons granted heretofore, since these have equal efficacy?"

- To repress these arguments and scruples of the laity by force alone, and not to resolve them by giving reasons, is to expose the Church and the pope to the ridicule of their enemies, and to make Christians unhappy.

- If, therefore, pardons were preached according to the spirit and mind of the pope, all these doubts would be readily resolved; nay, they would not exist.

- Away, then, with all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, "Peace, peace," and there is no peace!

- Blessed be all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, "Cross, cross," and there is no cross!

- Christians are to be exhorted that they be diligent in following Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, and hell;

- And thus be confident of entering into heaven rather through many tribulations, than through the assurance of peace.

- Martin Luther

- Reformation

External links

- The 95 Theses in the original Latin

- The 95 Theses in English

- Church Activities

- Church History

- Church Practices

- Church Structure

- Church and Society

- Church Today

- About Greg & Darlene

Exploring Martin Luther and the 95 Theses: A Deep Dive

- by Greg Gaines

- December 3, 2023 December 3, 2023

Martin Luther and the 95 Theses are synonymous with the 16th-century Protestant Reformation . This period was marked by a theological controversy within the Catholic Church and the influential Ninety-Five Theses put forth by religious reformer Martin Luther . The teachings of Luther, particularly his critique of indulgences and the authority of the Papal office, sparked a wave of religious reform that had lasting effects . It all began in the town of Wittenberg , where Luther nailed his theses to the door of the local church, igniting a firestorm of debate and reshaping the landscape of Christianity.

Key Takeaways:

- The 95 Theses were a pivotal moment in the 16th-century Protestant Reformation .

- Martin Luther challenged the Catholic Church’s teachings on indulgences and Papal authority .

- The theses sparked a wave of religious reform and reshaped Christianity.

- The town of Wittenberg played a significant role in Luther’s actions and the spread of his ideas.

- Salvation and the focus on faith in Christ were central themes in Luther’s teachings.

Nailing stuff to church doors wasn’t revolutionary in and of itself

The act of nailing grievances or academic papers to church doors was not uncommon during Martin Luther’s time. On October 31, 1517, Luther, an obscure monk teaching at the New University in Wittenberg , engaged in a customary debate by nailing his 95 Theses to the local church door. This act was done in accordance with scholarly practice and carried out in Latin , the accepted language of academia at the time. Contrary to popular belief, this act was not initially intended to spark a full-blown movement but rather to provoke an academic debate on indulgences .

“I believe that Luther simply wanted to open a dialogue and engage in a scholarly discussion on the topic of indulgences,” says Professor John Smith, a prominent Luther scholar. “The act of nailing the theses to the church door was a common and accepted method of inviting academic discourse during that period. It was a way for Luther to express his concerns to his colleagues and initiate a debate on the subject.”

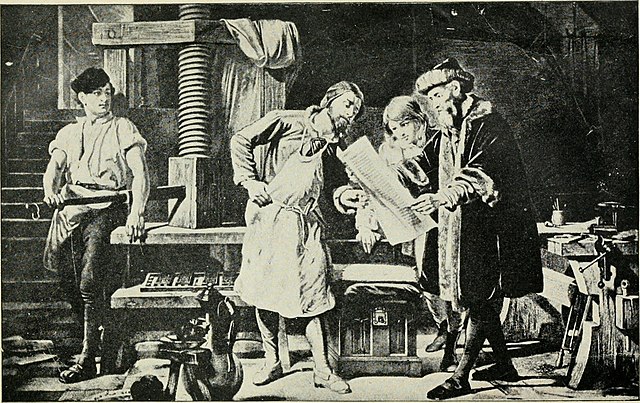

Luther’s action of nailing the 95 Theses to the church door was significant for its time, but its revolutionary impact was only realized in retrospect. The subsequent spread of his ideas and the reactions they elicited led to a profound transformation of the Church and European society. It was the combination of Luther’s ideas, the contextual timing, and the power of the printing press that turned this academic debate into a catalyst for religious reform and cultural change.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Academic Theses Nailings

The act of nailing documents to church doors as a means of initiating academic debate was a practice that extended beyond Luther’s time. It serves as a reminder that seemingly small actions in history can have far-reaching consequences, shaping the course of society and influencing future generations.

This wasn’t the first time indulgences were criticized

Before Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the church door in Wittenberg, there were already criticisms surrounding the practice of indulgences within the Catholic Church . Church leaders and scholars had expressed concerns about the corruption surrounding indulgences, which were often seen as a means for the Church to raise funds. Indulgences were a source of theological controversy , as some believed they undermined the necessity of true repentance and faith in salvation .

Luther himself had voiced his concerns regarding indulgences prior to the publication of his 95 Theses. However, it is important to note that Luther did not outright call for the abolition of indulgences, but rather advocated for their reform. His main concern was the emphasis on indulgences as a means to obtain salvation , rather than placing faith and trust in Christ. The publication of the 95 Theses ignited a wider discussion on indulgences and led to further calls for reform within the Church.

Table: Examples of Criticisms Surrounding Indulgences

“The sale of indulgences has become a major concern within the Church. It undermines the true message of salvation and places undue emphasis on financial transactions. Reform is necessary to restore the integrity of the Church.”

Overall, while Martin Luther’s 95 Theses were significant in sparking the Reformation , they were not the first criticisms of indulgences. Luther’s bold act of challenging the Church’s practices added fuel to an ongoing debate and ultimately contributed to a wider movement for religious reform.

Luther’s Theses Translated and Published

After Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the church door, the impact of his ideas reached a wider audience through translation and publication . One of the key developments was the translation of his theses into German , a language that the common people could understand and relate to. This translation played a significant role in disseminating Luther’s ideas beyond the academic and ecclesiastical circles.

The publication of Luther’s translated theses without his permission was a game-changer. It allowed his ideas to swiftly spread among the masses, igniting fervor and curiosity. The translated version of the 95 Theses became accessible to a wider audience, enabling them to engage with Luther’s criticisms of the church and the practice of indulgences.

The translation and publication of Luther’s theses in German showcased the power of the printing press in disseminating ideas and shaping public opinion. It contributed to the rapid spread of Luther’s teachings and ignited a fervor for religious reform across Europe. The translation and publication of Luther’s theses without his consent became a pivotal factor in the success of the Protestant Reformation , as it brought his ideas to the attention of the masses and set the stage for the transformative changes that would follow.

The Power of Translation and Publication

Translation and publication played a vital role in the spread of Martin Luther’s ideas beyond scholarly circles, reaching a wider audience and paving the way for significant religious and social transformations.

The theses weren’t as hard on the pope as you might think

While Luther’s 95 Theses certainly challenged the authority of the Catholic Church , they were not as harsh on the papacy as one might expect. Luther acknowledged the limitations of the pope’s power, with some theses asserting that the pope cannot remit sin or have jurisdiction over certain matters. However, Luther also affirmed the pope’s authority in certain areas, such as the distribution of indulgences. Ultimately, Luther’s focus was on redirecting the congregation’s confidence from the papacy to Christ as the source of salvation.

“…for it is clear that the power of the Pope is of itself sufficient for the remission of penalties and cases reserved by himself. The papal indulgences must be preached with caution, lest people erroneously think that they are preferable to other good works of love. Christians are to be taught that the pope does not intend that the buying of indulgences should in any way be compared with works of mercy. Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better deed than he who buys indulgences.”

Luther’s critique of the papacy focused on the misuse and misunderstanding of indulgences, rather than seeking to completely dismantle the authority of the pope. He emphasized the importance of faith in Christ and the need for sincere repentance and good works rather than relying solely on the purchasing of indulgences. The goal was not to undermine the papacy but to redirect the faith and confidence of believers towards a more genuine and personal relationship with God.

By expressing his critique in a measured and nuanced manner, Luther aimed to initiate a thoughtful dialogue and bring about reform within the Catholic Church. However, his ideas and the subsequent response from the Church led to a larger movement that eventually led to the Protestant Reformation .

…but that’s not to say Luther took a weak stance

Despite not being overly harsh on the pope, Luther did not hold back in his criticisms of church practices. He accused preachers of indulgences of misleading the people and denying the necessity of contrition for redemption. Luther emphasized the importance of caring for the poor over purchasing indulgences. His stance challenged the notion that forgiveness could be bought and highlighted the need for genuine contrition and faith in God’s grace.

“The temporal ruler is bound to punish those who think that indulgences are the gift of God. The pope is bound to do the like, for those commissaries of his, who dispense pardons at the same time, need money, badly. This desperate assurance of remission of sins would do the Church no harm if there were order in other parts [of the Church’s work], but now it does great harm.”

Through his critique of indulgences and his focus on the importance of true contrition and salvation, Luther aimed to redirect the congregation’s attention from external practices to a heartfelt relationship with God. His teachings marked a significant departure from the prevailing beliefs of the time and laid the foundation for the Protestant Reformation .

Furthermore, Luther’s criticisms of the church challenged the status quo and paved the way for further reforms within Christianity. His emphasis on personal responsibility and the care for the poor served as a reminder of the core principles of the Christian faith and resonated with many who were disillusioned with the corruption and materialism within the Catholic Church.

It might not have been the theses that sparked the Reformation after all

While Martin Luther’s 95 Theses undoubtedly played a significant role in the Protestant Reformation , it is important to note that it was not necessarily the publication of these theses alone that sparked the movement. In fact, there were other key events and factors that contributed to the widespread dissemination of Luther’s ideas and ultimately ignited the religious revolution that reshaped Europe.

One of these events was Luther’s visit to Heidelberg , where he delivered a series of sermons on indulgences. These sermons were subsequently translated into German, a language accessible to the masses, and published. This translation and publication of Luther’s sermons brought his ideas to a wider audience, sparking a broader discussion within Christendom and challenging the authority of both national and church leaders .

“The translation and publication of Luther’s sermons on indulgences in German played a crucial role in igniting the Protestant Reformation and reshaping the religious and social landscape of Europe.”

Furthermore, it was not only the theses themselves that drove the Reformation forward but also the wider discussion and debate they generated. Luther’s bold stance against indulgences and his emphasis on salvation through faith in Christ sparked a theological revolution that resonated with many individuals who had long questioned the practices and authority of the Catholic Church.

Overall, while Luther’s 95 Theses were instrumental in challenging the status quo and initiating the Protestant Reformation, it was the combination of events such as Luther’s visit to Heidelberg , the translation and publication of his sermons, and the subsequent wider discussion and debate that truly galvanized the movement, ultimately reshaping the religious and social fabric of Europe.

Effects of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses: Shaking up the World!

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses had a profound impact on the world. They initiated a religious earthquake by challenging the authority of the Catholic Church and encouraging theological debates. The theses also set off social ripples with their widespread dissemination through the printing press , empowering individuals to question both the Church and secular authorities. However, the theses also had unintended consequences , including religious conflicts and a renewed emphasis on education and literacy.

One of the major effects of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses was the rise of the Protestant Reformation. By challenging the doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church, Luther sparked a theological revolution that led to the formation of new religious groups and the splintering of Christianity. This religious diversity had far-reaching consequences, shaping the religious landscape of Europe and beyond.

Furthermore, the publication and spread of Luther’s ideas had significant social implications. The easy availability of printed copies of the 95 Theses allowed people from all walks of life to engage with and discuss theological matters. This resulted in a questioning of traditional authority structures, as individuals began to challenge not only the Church but also secular powers. The printing press became a catalyst for social change, fueling the flames of intellectual curiosity, democratic ideals, and the pursuit of personal freedom.

While Martin Luther’s 95 Theses were intended to reform the Catholic Church, they had unintended consequences as well. The religious conflicts that erupted in the wake of the Reformation resulted in violence and upheaval, further deepening divisions within Christendom. Additionally, the emphasis on individual interpretation of scripture and the rejection of traditional hierarchy led to a renewed focus on education and literacy. The Protestant movement placed a strong emphasis on the ability of individuals to read and interpret the Bible for themselves, leading to the establishment of schools and universities.

Table: Impact of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses

Faq: what were the effects of the 95 theses.

The publication of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses had a profound impact on the Protestant Reformation and brought about significant religious diversity and social changes .

Effects on Religious Diversity

The 95 Theses challenged the authority of the Catholic Church, leading to the emergence of new Protestant denominations. This resulted in religious diversity , as individuals sought alternative interpretations of Christianity that aligned with their own beliefs. The Reformation sparked theological debates and the formation of different religious communities, contributing to a more pluralistic religious landscape.

Effects on Social Changes

The 95 Theses also had far-reaching social implications. The Reformation motivated individuals to question not only religious authority but also secular authority. The emphasis on personal faith and individual interpretation of scripture led to the rise of democratic ideals and the separation of church and state. Additionally, the Reformation sparked discussions about social justice and equality, with reformers advocating for a more compassionate approach towards the less fortunate.

Effects on Religious Warfare and Education

While the 95 Theses brought about positive changes, they also sparked religious warfare and intolerance. The Reformation led to conflicts between Protestants and Catholics, resulting in violence and persecution. However, the Reformation also led to a renewed focus on education and literacy. The establishment of schools and universities became a priority for both Protestants and Catholics, as they sought to educate the masses on their respective religious doctrines.

“The 95 Theses challenged the authority of the Catholic Church and paved the way for religious diversity and social change.”

What Was the Pope’s Response to the 95 Theses

“I am convinced that this Martin is a heretic … He calls into doubt the authority of the pope and our sacred traditions. His ideas are dangerous and must be silenced,” declared Pope Leo X in response to Luther’s 95 Theses.

The Pope’s condemnation of Luther’s teachings further fueled the religious controversy surrounding indulgences and set the stage for the ongoing theological dispute between Luther and the Catholic Church. It highlighted the entrenched opposition to questioning the authority of the Pope and the established practices of the Church.

The Pope’s response to the 95 Theses marked a pivotal moment in the Protestant Reformation, intensifying the divide between Luther and the Catholic Church and solidifying Luther’s role as a prominent figure in the religious upheaval of the 16th century.

Causes of the Reformation

The Reformation was a significant historical event that reshaped religious, social, and political landscapes. It was driven by several key causes , each contributing to the discontent and desire for change in 16th-century Europe.

The Corruption and Financial Excesses of the Catholic Church

One of the main causes of the Reformation was the corruption and financial excesses of the Catholic Church. The Church faced widespread criticism for its indulgence practices, in which forgiveness of sins could be bought through monetary contributions. This led to a sense of dissatisfaction among the faithful, who believed that such practices were exploitative and undermined the core principles of faith and salvation.

The Influence of the Renaissance and Humanist Ideas

The Renaissance , characterized by a renewed interest in humanism and a focus on individualism, also played a significant role in the Reformation. Humanist ideas emphasized the importance of reason, independent thinking, and the potential for human progress. These ideas challenged the authority of the Catholic Church and its rigid hierarchy, paving the way for dissent and intellectual freedom.

The Printing Press and the Spread of Ideas

The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg revolutionized the dissemination of information and played a crucial role in the Reformation. This groundbreaking technology allowed for the mass production of books and pamphlets, making ideas more accessible to a wider audience. The ability to print and distribute religious texts, including Martin Luther’s writings, enabled the rapid spread of reformist ideas and facilitated a broader discussion on religious reform.

The causes of the Reformation were multifaceted, with corruption in the Church, the influence of the Renaissance , and the advent of the printing press all playing significant roles. These factors created an environment ripe for reformist ideas to take hold and sparked a revolution that reshaped religious, social, and political structures in Europe.

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses marked a pivotal moment in history, leading to the Protestant Reformation and bringing about significant religious, social, and political changes . Through his act of defiance, Luther shook the authority of the Catholic Church and set in motion a theological revolution. His ideas sparked widespread debate and challenged the traditional understanding of faith, salvation, and Papal authority .

The consequences of Luther’s theses were far-reaching, with lasting impacts on religious practices and beliefs. The Reformation led to the emergence of new Protestant denominations and a diversification of religious expression. It also brought about a shift in power dynamics, as individuals gained the autonomy to question both religious and secular authorities.

Furthermore, the Protestant Reformation had profound social and political implications. It fostered the rise of democratic ideals and the separation of church and state, paving the way for the development of modern societies. However, it also led to religious conflicts and intolerance, highlighting the complexity and multifaceted nature of this transformative period in history.

In conclusion , Martin Luther’s 95 Theses propelled the Protestant Reformation, initiating a wave of religious, social, and political changes that continue to shape our world today. Luther’s courageous act challenged the status quo and opened the door to a new era of religious thought, redefining the relationship between church and state, and leaving an indelible mark on the course of history.

Was nailing documents to church doors a common practice during Martin Luther’s time?

Yes, nailing grievances or academic papers to church doors was not uncommon during Martin Luther’s time.

What language were Martin Luther’s 95 Theses written in?

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses were written in Latin, the accepted language of academia at the time.

Did Martin Luther’s 95 Theses call for the abolition of indulgences?

No, Martin Luther’s 95 Theses did not call for the abolition of indulgences but rather advocated for their reform.

How did the translation of Luther’s 95 Theses into German impact the spread of his ideas?

The translation of Luther’s 95 Theses into German played a crucial role in spreading his ideas beyond academic and ecclesiastical circles.

Did Martin Luther harshly criticize the Pope in his 95 Theses?

No, Martin Luther’s 95 Theses were not overly harsh on the Pope, although they did acknowledge the limitations of the Pope’s power.

What were some of the criticisms Martin Luther had regarding church practices?

Martin Luther criticized preachers of indulgences for misleading the people and emphasized the importance of caring for the poor over purchasing indulgences.

Did the publication of the 95 Theses alone spark the Protestant Reformation?

No, it was not solely the publication of the 95 Theses that sparked the Protestant Reformation, but rather Luther’s wider discussions and teachings.

What were the effects of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses?

The effects of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses were significant, leading to religious diversity, social changes , religious warfare, and a renewed focus on education.

How did the Pope respond to Martin Luther’s 95 Theses?

The Pope responded to Martin Luther’s 95 Theses with condemnation, viewing them as a direct threat to his authority and the practice of selling indulgences.

What were the causes of the Reformation?

The causes of the Reformation included corruption and financial excesses within the Catholic Church, the influence of the Renaissance and humanist ideas , and the invention of the printing press.

What were the overall impacts of Martin Luther’s actions and ideas?

Martin Luther’s actions and ideas had profound religious, social, and political impacts, leading to significant changes in religious thought and redefining the relationship between church and state.

Source Links

- https://www.logos.com/grow/6-facts-might-not-know-martin-luthers-95-theses/

- https://oatuu.org/martin-luthers-95-theses-the-impact-and-unsettling-consequences/

- https://www.pinterest.com/pin/435090013999977320/

Father / Grandfather / Minister / Missionary / Deacon / Elder / Author / Digital Missionary / Foster Parents / Welcome to our Family

View all posts

Related Posts:

- Comment and analysis

- Videos and audio

- revolutionary reflections

- Education, healthcare, housing, transport

- Borders, migration and race

- Anti-fascism and the far right

- Imperialism and international politics

- Climate and environment

- Feminism and LGBTQ liberation

- Work, unions and strikes

- Labour and Corbynism

- Revolutionary strategy

- Subscribe to our mailing list

- Write for us

- Motions and policies

- Strike solidarity

- Trade union motions

- Leaflets, posters and guides

- Workers Can Win! A Guide to Organising At Work

Half a millennium away: Martin Luther’s 95 theses 500 years on

On the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, Andrew Stone looks at the context in which Protestantism arose and the global impact it had.

Within three years Martin Luther, the monk in question, was throwing a Papal Bull (a sacred command from the Pope) into a bonfire of books about the legal power of the Church. Protestantism was born. It would have a profound effect on European history – playing a significant role in, among much else, the German Peasants Revolt, the French Wars of Religion, the Dutch Revolt, the English Revolution. But its impact would touch all continents in the ideological support it often provided for colonisation, slavery and even the genocide of indigenous peoples, as well as articulating resistance to these crimes.

Luther was not the first to challenge the universal claims of the Catholic Church – the Eastern Orthodox church had broken away in 1054 – nor the first to encourage a popular religious movement – John Wycliffe’s Lollardy of the late 14 th century was one of several to do likewise. But the ‘magnificent anarchy’ of theological questioning that followed combined elements of both reform from above and radicalism from below that contributed to the formations of a new schism within the dominant institutions of the early modern world.

Luther’s heresy only had time to take root because of a favourable conjunction of circumstances. While the Pope claimed spiritual hegemony over all western Christendom, his powers of enforcement varied according to the temporal power of each kingdom. Five hundred years ago German statelets were part of the vast Holy Roman Empire, but it exerted relatively weak central authority. Luther’s position was strengthened because one of the seven men responsible for electing the Emperor, Frederick the Wise, was also Luther’s sympathetic patron. Frederick also had a personal stake in discrediting Tetzel, whose indulgence scheme was undercutting the value of his own vast holy relic collection.

This came at a time of heightened millennial expectations. Though the half millennium of 1500 had passed relatively peacefully, 1524 marked the Great Conjunction of the Stars to coincide with the conjunction of all the Planets in Pisces. Whereas astrologers nowadays would probably say that this suggested Luther would have an unexpected opportunity with someone from his past, at the time it was said to herald the second coming of Christ.

Such prophecies seemed less farfetched when, in 1524, a massive revolt of German peasants over enclosures and the re-imposition of serfdom led to what some Marxists, such as Karl Kautsky , have seen as a form of proto-Communism. At the heart of this movement were the Anabaptists, whose central belief that adults should enter the church as a matter of personal commitment rather than through induction as infants was an affront to the universalist pretensions of both Catholicism and the emergent Lutheranism. The notion that there should be competing claims on a subject’s loyalty, and thus that there should be toleration outside of the state church, was one which neither Catholic nor Protestant monarch would happily accept. The ideas of some, that wealth should be redistributed, and communal living practiced, was complete anathema.

Leading this ‘radical reformation’ was preacher Thomas Muntzer, and the centre of what Kautsky considers the ‘Anabaptist revolution’ was the city of Munster, which was seized by the insurgents and attempted to hold out against a siege by a combination of Catholic and Protestant forces. It was eventually drowned in blood, as was the entire peasant uprising. Much to the disgust of many of those his resistance to Rome had inspired, this repression was egged on by Martin Luther. While he preached for a ‘priesthood of believers’, this signified spiritual but not social equality. When the rebels raised this prospect he wrote a pamphlet called Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants in which he urged that everyone who could should “smite, slay and stab [the rebels], secretly or openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful or devilish than a rebel.”

Luther thus unequivocally sided with the ‘magisterial reformation’, the elite-led process that encouraged some rulers to break from Rome to enhance their prestige, wealth and power. Henry VIII is an obvious example of the calculating aspect of this. Having previously been lauded by the Pope for a treatise against Luther, he ultimately broke with Rome after it resisted his prerogative to ensure the succession. His seizure of dynastic land was a brief boon to his imperial ambitions, before the wealth was squandered on continental warfare.

Why Protestantism emerged at this time, and to such dramatic effect, has been an issue of lively debate. Marxism has often been attributed with a rather crude characterisation that capitalism created Protestantism as a form of ideological legitimation. Neil Davidson argues in How Revolutionary were the Bourgeois Revolutions? that Marx never made this claim. Instead Davidson categorises three main types of ruling class Protestantism: 1) the initial Lutheran rule in the German principalities and Scandinavia 2) the Anglo-Catholicism of Henry VIII and Elizabeth’s High Anglicanism and 3) the so-called ‘Calvinist International’, based on the ‘justification by faith alone’ sermons of John Calvin, for example in the Dutch Republic.

Davidson insists that:

The relationship between Calvinism and the bourgeois revolutions is therefore a complex one. All bourgeois revolutionary movements down to and including the English Revolution involved Calvinism, but very few Calvinist movements down to and including the English Revolution led to bourgeois revolutions. Calvinism was a doctrine that gave support to those who wished to overthrow a state, but there were many different social forces seeking to overthrow states in mid-sixteenth-century Europe, very few of them remotely bourgeois in composition.

A purely religious explanation for the conflicts of the Early Modern period is inadequate. To give just two examples:

1) The Dutch grandees of the 1560s who attempted to broker a degree of religious toleration for the minority Calvinists against the Spanish Inquisition were, perhaps unexpectedly, overwhelmingly Catholic. To explain why they did so requires a much deeper appreciation of the fragmented political structure in the Netherlands, but also the pressures and opportunities created by a uniquely urbanised and developed market economy.

2) Oliver Cromwell was Puritan by conviction. He justified atrocities in Ireland on this basis, and at other times was plagued by religious introspection (for example when offered the crown). But even he was prepared to form an alliance with Catholic Spain while waging war with the Calvinist Netherlands, as the latter were by this time England’s key trade rival.

So social and economic analysis remains important to a holistic understanding of how Protestantism emerged, but we must remember the interplay with religion as the language in which people understood their worlds and their aspirations (in this life and the next), and how they went about securing these. Perhaps the key way this is illustrated is how the development of the productive forces of society and therefore the possibilities for rapid religious communication and conversion coalesced through the creation of the printing press. So in 1517 Luther’s 95 Theses was quickly translated from Latin into German, and within weeks was being published in its thousands. Another key text of the period was William Tyndale’s Book of Common Prayer , who saw his translation of sacred texts as “empowering through the vernacular, through the English language, every member of society down to the lowliest ploughboy”.

Conservative historian Niall Ferguson has dubbed this ‘the first age of networking’, drawing a comparison with modern social networks. The analogy has some traction, but only when combined with an awareness of the class resources and relationships that enabled rulers and ruled to propagate their ideas – and to back them up with the force of states or collective resistance to them.

No short article could adequately summarise how the Protestant Reformation affected the subsequent 500 years of history. But suffice to say, like all religion Protestantism is multifaceted – it is both the justification for the democratisation of the Levellers, and the butchery of Cromwell and William of Orange in Ireland. It justifies both the anti-choice bigotry of the Democratic Unionist Party and the civil rights leadership of Martin Luther King. Religion under capitalism can seem to provide comfort and amelioration in a world that requires much of both. It is not the enemy of those fighting for change, any more than football is, despite the existence of groups such as the Football Lads Alliance. Sometimes it is the voice of the voiceless and sometimes it tells us that there is ‘nothing more devilish than a rebel’. But the devil is in the detail.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

How should socialists think about political tradition?

Remembering the Portuguese Revolution

1974 – an end and a beginning

Video | Abolition Revolution

Militarism and anti-militarism

Here We Go! Forty years on from the outbreak of the Great Strike

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Get involved

Join our mailing list

Events calendar

Local groups

Latest articles

Why cutting welfare hurts non-claimants

Debate – a response on settler colonialism

Dover’s dodgy defector

Report from the Newcastle University encampment

Kick out the Tories, prepare to fight Starmer

Long hot summer?

Cass Review: dangerous and transphobic

The Courtaulds strike of 1965 – Black workers fighting back

rs21 – the first ten years

Palestine 101: A century of Palestinian resistance

Into the abyss: On the Argentinian elections.

What’s going on in Unite? | Part 1

Key Terms for All Subjects

50k vocabulary words to help you ace your ap, sat & act exams, new subjects.

Included in your Cram Mode subscription at no additional cost.

Anatomy & Physiology

Intro to Business

Intro to Political Science

Intro to Sociology

Organic Chemistry

AP Art & Design

AP Art History

AP Music Theory

AP Capstone

AP Research

AP English Language

AP English Literature

AP European History

AP US History

AP World History: Modern

AP Chemistry

AP Environmental Science

AP Physics 1

AP Physics 2

AP Physics C: E&M

AP Physics C: Mechanics

AP Math & Computer Science

AP Calculus AB/BC

AP Computer Science A

AP Computer Science Principles

AP Pre-Calculus

AP Statistics

AP Social Science

AP Comparative Government

AP Human Geography

AP Macroeconomics

AP Microeconomics

AP Psychology

AP US Government

AP World Languages & Cultures

AP Japanese

AP Spanish Language

AP Spanish Literature

Stay Connected

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

AP® and SAT® are trademarks registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with EHR?

- About The English Historical Review

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Books for Review

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses and the Origins of the Reformation Narrative

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

C Scott Dixon, Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses and the Origins of the Reformation Narrative, The English Historical Review , Volume 132, Issue 556, June 2017, Pages 533–569, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cex224

- Permissions Icon Permissions