- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 June 2021

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: an overview of systematic reviews

- Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento 1 , 2 ,

- Dónal P. O’Mathúna 3 , 4 ,

- Thilo Caspar von Groote 5 ,

- Hebatullah Mohamed Abdulazeem 6 ,

- Ishanka Weerasekara 7 , 8 ,

- Ana Marusic 9 ,

- Livia Puljak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8467-6061 10 ,

- Vinicius Tassoni Civile 11 ,

- Irena Zakarija-Grkovic 9 ,

- Tina Poklepovic Pericic 9 ,

- Alvaro Nagib Atallah 11 ,

- Santino Filoso 12 ,

- Nicola Luigi Bragazzi 13 &

- Milena Soriano Marcolino 1

On behalf of the International Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19)

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 21 , Article number: 525 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

16k Accesses

29 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Navigating the rapidly growing body of scientific literature on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is challenging, and ongoing critical appraisal of this output is essential. We aimed to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in humans that were available at the beginning of the pandemic.

Nine databases (Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Web of Sciences, PDQ-Evidence, WHO’s Global Research, LILACS, and Epistemonikos) were searched from December 1, 2019, to March 24, 2020. Systematic reviews analyzing primary studies of COVID-19 were included. Two authors independently undertook screening, selection, extraction (data on clinical symptoms, prevalence, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, diagnostic test assessment, laboratory, and radiological findings), and quality assessment (AMSTAR 2). A meta-analysis was performed of the prevalence of clinical outcomes.

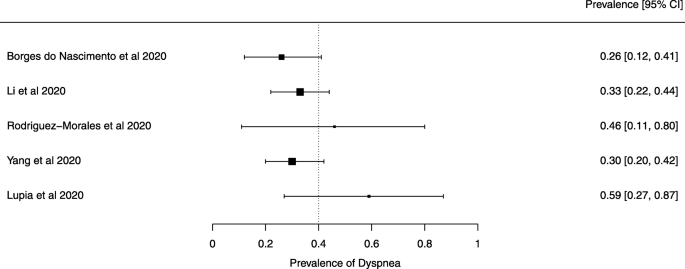

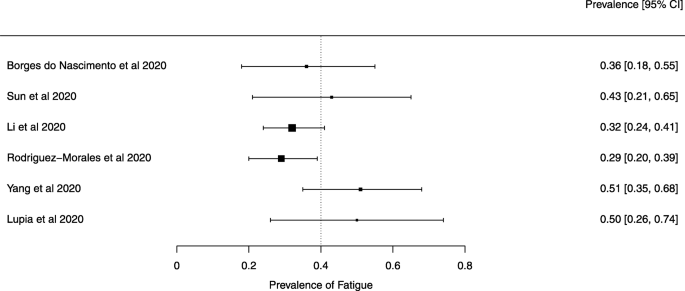

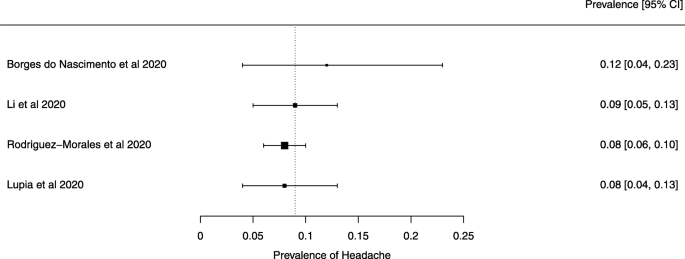

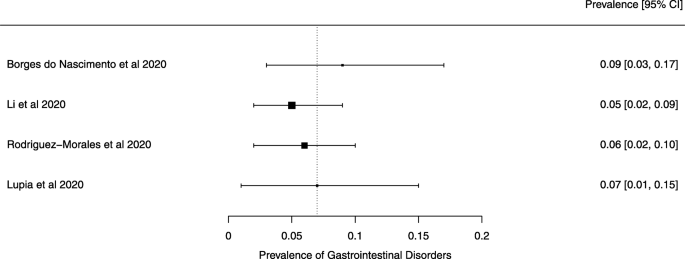

Eighteen systematic reviews were included; one was empty (did not identify any relevant study). Using AMSTAR 2, confidence in the results of all 18 reviews was rated as “critically low”. Identified symptoms of COVID-19 were (range values of point estimates): fever (82–95%), cough with or without sputum (58–72%), dyspnea (26–59%), myalgia or muscle fatigue (29–51%), sore throat (10–13%), headache (8–12%) and gastrointestinal complaints (5–9%). Severe symptoms were more common in men. Elevated C-reactive protein and lactate dehydrogenase, and slightly elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferase, were commonly described. Thrombocytopenia and elevated levels of procalcitonin and cardiac troponin I were associated with severe disease. A frequent finding on chest imaging was uni- or bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacity. A single review investigated the impact of medication (chloroquine) but found no verifiable clinical data. All-cause mortality ranged from 0.3 to 13.9%.

Conclusions

In this overview of systematic reviews, we analyzed evidence from the first 18 systematic reviews that were published after the emergence of COVID-19. However, confidence in the results of all reviews was “critically low”. Thus, systematic reviews that were published early on in the pandemic were of questionable usefulness. Even during public health emergencies, studies and systematic reviews should adhere to established methodological standards.

Peer Review reports

The spread of the “Severe Acute Respiratory Coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2), the causal agent of COVID-19, was characterized as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020 and has triggered an international public health emergency [ 1 ]. The numbers of confirmed cases and deaths due to COVID-19 are rapidly escalating, counting in millions [ 2 ], causing massive economic strain, and escalating healthcare and public health expenses [ 3 , 4 ].

The research community has responded by publishing an impressive number of scientific reports related to COVID-19. The world was alerted to the new disease at the beginning of 2020 [ 1 ], and by mid-March 2020, more than 2000 articles had been published on COVID-19 in scholarly journals, with 25% of them containing original data [ 5 ]. The living map of COVID-19 evidence, curated by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), contained more than 40,000 records by February 2021 [ 6 ]. More than 100,000 records on PubMed were labeled as “SARS-CoV-2 literature, sequence, and clinical content” by February 2021 [ 7 ].

Due to publication speed, the research community has voiced concerns regarding the quality and reproducibility of evidence produced during the COVID-19 pandemic, warning of the potential damaging approach of “publish first, retract later” [ 8 ]. It appears that these concerns are not unfounded, as it has been reported that COVID-19 articles were overrepresented in the pool of retracted articles in 2020 [ 9 ]. These concerns about inadequate evidence are of major importance because they can lead to poor clinical practice and inappropriate policies [ 10 ].

Systematic reviews are a cornerstone of today’s evidence-informed decision-making. By synthesizing all relevant evidence regarding a particular topic, systematic reviews reflect the current scientific knowledge. Systematic reviews are considered to be at the highest level in the hierarchy of evidence and should be used to make informed decisions. However, with high numbers of systematic reviews of different scope and methodological quality being published, overviews of multiple systematic reviews that assess their methodological quality are essential [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. An overview of systematic reviews helps identify and organize the literature and highlights areas of priority in decision-making.

In this overview of systematic reviews, we aimed to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in humans that were available at the beginning of the pandemic.

Methodology

Research question.

This overview’s primary objective was to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews that assessed any type of primary clinical data from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Our research question was purposefully broad because we wanted to analyze as many systematic reviews as possible that were available early following the COVID-19 outbreak.

Study design

We conducted an overview of systematic reviews. The idea for this overview originated in a protocol for a systematic review submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42020170623), which indicated a plan to conduct an overview.

Overviews of systematic reviews use explicit and systematic methods for searching and identifying multiple systematic reviews addressing related research questions in the same field to extract and analyze evidence across important outcomes. Overviews of systematic reviews are in principle similar to systematic reviews of interventions, but the unit of analysis is a systematic review [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

We used the overview methodology instead of other evidence synthesis methods to allow us to collate and appraise multiple systematic reviews on this topic, and to extract and analyze their results across relevant topics [ 17 ]. The overview and meta-analysis of systematic reviews allowed us to investigate the methodological quality of included studies, summarize results, and identify specific areas of available or limited evidence, thereby strengthening the current understanding of this novel disease and guiding future research [ 13 ].

A reporting guideline for overviews of reviews is currently under development, i.e., Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR) [ 18 ]. As the PRIOR checklist is still not published, this study was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 statement [ 19 ]. The methodology used in this review was adapted from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and also followed established methodological considerations for analyzing existing systematic reviews [ 14 ].

Approval of a research ethics committee was not necessary as the study analyzed only publicly available articles.

Eligibility criteria

Systematic reviews were included if they analyzed primary data from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 as confirmed by RT-PCR or another pre-specified diagnostic technique. Eligible reviews covered all topics related to COVID-19 including, but not limited to, those that reported clinical symptoms, diagnostic methods, therapeutic interventions, laboratory findings, or radiological results. Both full manuscripts and abbreviated versions, such as letters, were eligible.

No restrictions were imposed on the design of the primary studies included within the systematic reviews, the last search date, whether the review included meta-analyses or language. Reviews related to SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses were eligible, but from those reviews, we analyzed only data related to SARS-CoV-2.

No consensus definition exists for a systematic review [ 20 ], and debates continue about the defining characteristics of a systematic review [ 21 ]. Cochrane’s guidance for overviews of reviews recommends setting pre-established criteria for making decisions around inclusion [ 14 ]. That is supported by a recent scoping review about guidance for overviews of systematic reviews [ 22 ].

Thus, for this study, we defined a systematic review as a research report which searched for primary research studies on a specific topic using an explicit search strategy, had a detailed description of the methods with explicit inclusion criteria provided, and provided a summary of the included studies either in narrative or quantitative format (such as a meta-analysis). Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews were considered eligible for inclusion, with or without meta-analysis, and regardless of the study design, language restriction and methodology of the included primary studies. To be eligible for inclusion, reviews had to be clearly analyzing data related to SARS-CoV-2 (associated or not with other viruses). We excluded narrative reviews without those characteristics as these are less likely to be replicable and are more prone to bias.

Scoping reviews and rapid reviews were eligible for inclusion in this overview if they met our pre-defined inclusion criteria noted above. We included reviews that addressed SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses if they reported separate data regarding SARS-CoV-2.

Information sources

Nine databases were searched for eligible records published between December 1, 2019, and March 24, 2020: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews via Cochrane Library, PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Web of Sciences, LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature), PDQ-Evidence, WHO’s Global Research on Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), and Epistemonikos.

The comprehensive search strategy for each database is provided in Additional file 1 and was designed and conducted in collaboration with an information specialist. All retrieved records were primarily processed in EndNote, where duplicates were removed, and records were then imported into the Covidence platform [ 23 ]. In addition to database searches, we screened reference lists of reviews included after screening records retrieved via databases.

Study selection

All searches, screening of titles and abstracts, and record selection, were performed independently by two investigators using the Covidence platform [ 23 ]. Articles deemed potentially eligible were retrieved for full-text screening carried out independently by two investigators. Discrepancies at all stages were resolved by consensus. During the screening, records published in languages other than English were translated by a native/fluent speaker.

Data collection process

We custom designed a data extraction table for this study, which was piloted by two authors independently. Data extraction was performed independently by two authors. Conflicts were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third researcher.

We extracted the following data: article identification data (authors’ name and journal of publication), search period, number of databases searched, population or settings considered, main results and outcomes observed, and number of participants. From Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), we extracted journal rank (quartile) and Journal Impact Factor (JIF).

We categorized the following as primary outcomes: all-cause mortality, need for and length of mechanical ventilation, length of hospitalization (in days), admission to intensive care unit (yes/no), and length of stay in the intensive care unit.

The following outcomes were categorized as exploratory: diagnostic methods used for detection of the virus, male to female ratio, clinical symptoms, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, laboratory findings (full blood count, liver enzymes, C-reactive protein, d-dimer, albumin, lipid profile, serum electrolytes, blood vitamin levels, glucose levels, and any other important biomarkers), and radiological findings (using radiography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasound).

We also collected data on reporting guidelines and requirements for the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses from journal websites where included reviews were published.

Quality assessment in individual reviews

Two researchers independently assessed the reviews’ quality using the “A MeaSurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR 2)”. We acknowledge that the AMSTAR 2 was created as “a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomized or non-randomized studies of healthcare interventions, or both” [ 24 ]. However, since AMSTAR 2 was designed for systematic reviews of intervention trials, and we included additional types of systematic reviews, we adjusted some AMSTAR 2 ratings and reported these in Additional file 2 .

Adherence to each item was rated as follows: yes, partial yes, no, or not applicable (such as when a meta-analysis was not conducted). The overall confidence in the results of the review is rated as “critically low”, “low”, “moderate” or “high”, according to the AMSTAR 2 guidance based on seven critical domains, which are items 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 as defined by AMSTAR 2 authors [ 24 ]. We reported our adherence ratings for transparency of our decision with accompanying explanations, for each item, in each included review.

One of the included systematic reviews was conducted by some members of this author team [ 25 ]. This review was initially assessed independently by two authors who were not co-authors of that review to prevent the risk of bias in assessing this study.

Synthesis of results

For data synthesis, we prepared a table summarizing each systematic review. Graphs illustrating the mortality rate and clinical symptoms were created. We then prepared a narrative summary of the methods, findings, study strengths, and limitations.

For analysis of the prevalence of clinical outcomes, we extracted data on the number of events and the total number of patients to perform proportional meta-analysis using RStudio© software, with the “meta” package (version 4.9–6), using the “metaprop” function for reviews that did not perform a meta-analysis, excluding case studies because of the absence of variance. For reviews that did not perform a meta-analysis, we presented pooled results of proportions with their respective confidence intervals (95%) by the inverse variance method with a random-effects model, using the DerSimonian-Laird estimator for τ 2 . We adjusted data using Freeman-Tukey double arcosen transformation. Confidence intervals were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method for individual studies. We created forest plots using the RStudio© software, with the “metafor” package (version 2.1–0) and “forest” function.

Managing overlapping systematic reviews

Some of the included systematic reviews that address the same or similar research questions may include the same primary studies in overviews. Including such overlapping reviews may introduce bias when outcome data from the same primary study are included in the analyses of an overview multiple times. Thus, in summaries of evidence, multiple-counting of the same outcome data will give data from some primary studies too much influence [ 14 ]. In this overview, we did not exclude overlapping systematic reviews because, according to Cochrane’s guidance, it may be appropriate to include all relevant reviews’ results if the purpose of the overview is to present and describe the current body of evidence on a topic [ 14 ]. To avoid any bias in summary estimates associated with overlapping reviews, we generated forest plots showing data from individual systematic reviews, but the results were not pooled because some primary studies were included in multiple reviews.

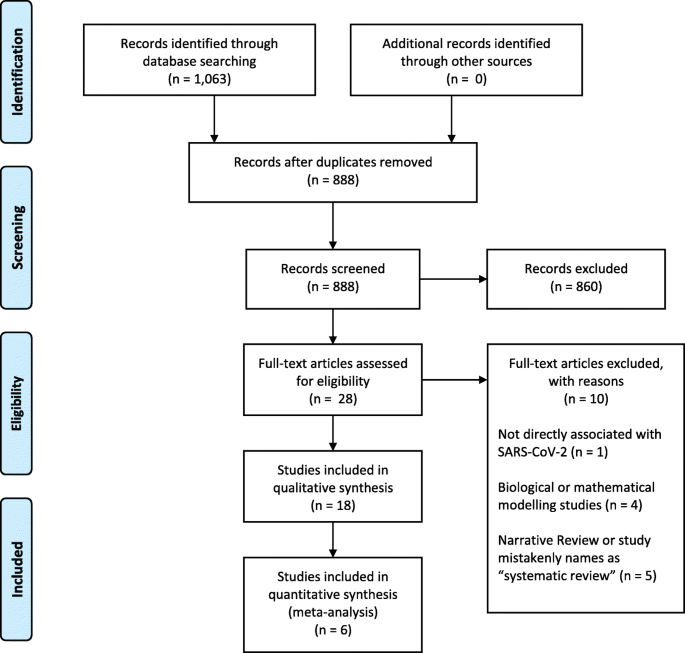

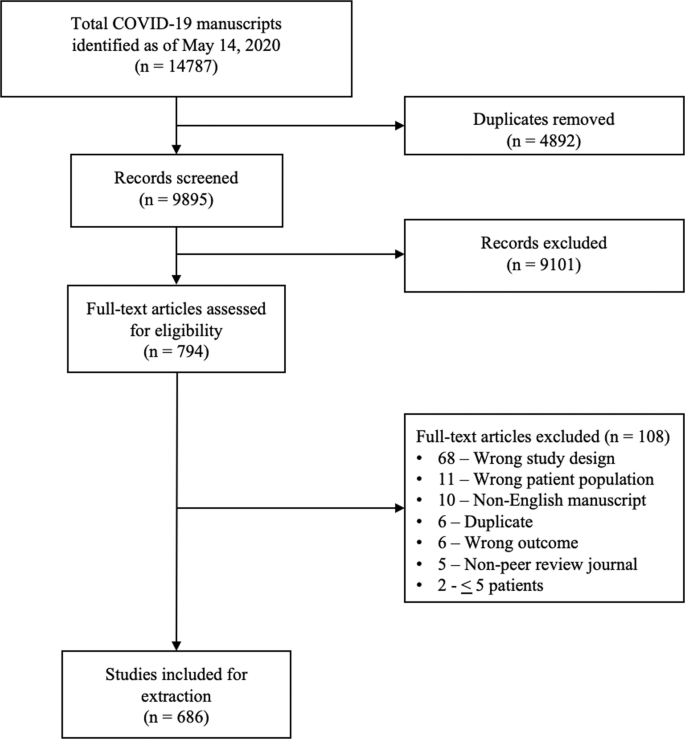

Our search retrieved 1063 publications, of which 175 were duplicates. Most publications were excluded after the title and abstract analysis ( n = 860). Among the 28 studies selected for full-text screening, 10 were excluded for the reasons described in Additional file 3 , and 18 were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1 ) [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Reference list screening did not retrieve any additional systematic reviews.

PRISMA flow diagram

Characteristics of included reviews

Summary features of 18 systematic reviews are presented in Table 1 . They were published in 14 different journals. Only four of these journals had specific requirements for systematic reviews (with or without meta-analysis): European Journal of Internal Medicine, Journal of Clinical Medicine, Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Clinical Research in Cardiology . Two journals reported that they published only invited reviews ( Journal of Medical Virology and Clinica Chimica Acta ). Three systematic reviews in our study were published as letters; one was labeled as a scoping review and another as a rapid review (Table 2 ).

All reviews were published in English, in first quartile (Q1) journals, with JIF ranging from 1.692 to 6.062. One review was empty, meaning that its search did not identify any relevant studies; i.e., no primary studies were included [ 36 ]. The remaining 17 reviews included 269 unique studies; the majority ( N = 211; 78%) were included in only a single review included in our study (range: 1 to 12). Primary studies included in the reviews were published between December 2019 and March 18, 2020, and comprised case reports, case series, cohorts, and other observational studies. We found only one review that included randomized clinical trials [ 38 ]. In the included reviews, systematic literature searches were performed from 2019 (entire year) up to March 9, 2020. Ten systematic reviews included meta-analyses. The list of primary studies found in the included systematic reviews is shown in Additional file 4 , as well as the number of reviews in which each primary study was included.

Population and study designs

Most of the reviews analyzed data from patients with COVID-19 who developed pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), or any other correlated complication. One review aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of using surgical masks on preventing transmission of the virus [ 36 ], one review was focused on pediatric patients [ 34 ], and one review investigated COVID-19 in pregnant women [ 37 ]. Most reviews assessed clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, or radiological results.

Systematic review findings

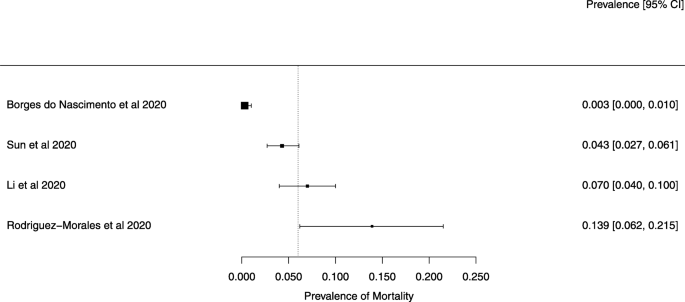

The summary of findings from individual reviews is shown in Table 2 . Overall, all-cause mortality ranged from 0.3 to 13.9% (Fig. 2 ).

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of mortality

Clinical symptoms

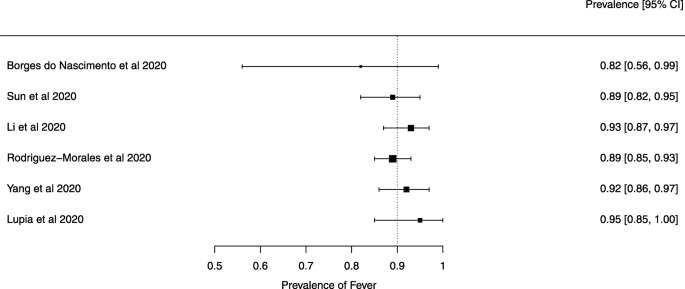

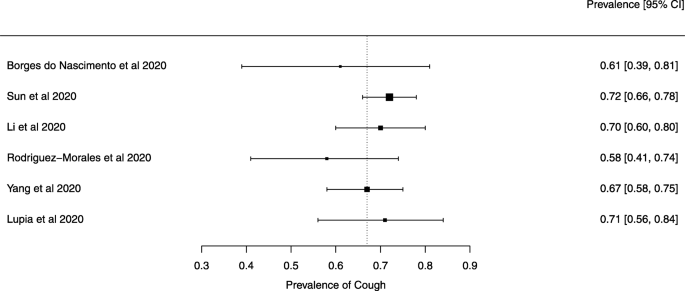

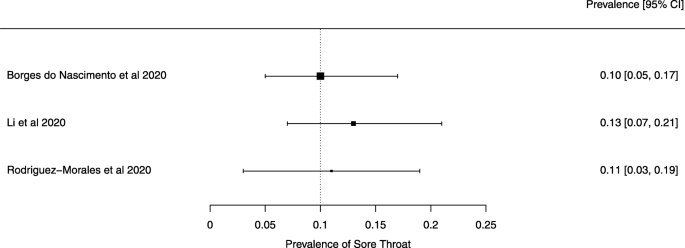

Seven reviews described the main clinical manifestations of COVID-19 [ 26 , 28 , 29 , 34 , 35 , 39 , 41 ]. Three of them provided only a narrative discussion of symptoms [ 26 , 34 , 35 ]. In the reviews that performed a statistical analysis of the incidence of different clinical symptoms, symptoms in patients with COVID-19 were (range values of point estimates): fever (82–95%), cough with or without sputum (58–72%), dyspnea (26–59%), myalgia or muscle fatigue (29–51%), sore throat (10–13%), headache (8–12%), gastrointestinal disorders, such as diarrhea, nausea or vomiting (5.0–9.0%), and others (including, in one study only: dizziness 12.1%) (Figs. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 and 9 ). Three reviews assessed cough with and without sputum together; only one review assessed sputum production itself (28.5%).

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of fever

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of cough

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of dyspnea

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of fatigue or myalgia

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of headache

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of gastrointestinal disorders

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of sore throat

Diagnostic aspects

Three reviews described methodologies, protocols, and tools used for establishing the diagnosis of COVID-19 [ 26 , 34 , 38 ]. The use of respiratory swabs (nasal or pharyngeal) or blood specimens to assess the presence of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid using RT-PCR assays was the most commonly used diagnostic method mentioned in the included studies. These diagnostic tests have been widely used, but their precise sensitivity and specificity remain unknown. One review included a Chinese study with clinical diagnosis with no confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection (patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 if they presented with at least two symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, together with laboratory and chest radiography abnormalities) [ 34 ].

Therapeutic possibilities

Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions (supportive therapies) used in treating patients with COVID-19 were reported in five reviews [ 25 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 38 ]. Antivirals used empirically for COVID-19 treatment were reported in seven reviews [ 25 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 41 ]; most commonly used were protease inhibitors (lopinavir, ritonavir, darunavir), nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (tenofovir), nucleotide analogs (remdesivir, galidesivir, ganciclovir), and neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir). Umifenovir, a membrane fusion inhibitor, was investigated in two studies [ 25 , 35 ]. Possible supportive interventions analyzed were different types of oxygen supplementation and breathing support (invasive or non-invasive ventilation) [ 25 ]. The use of antibiotics, both empirically and to treat secondary pneumonia, was reported in six studies [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 38 ]. One review specifically assessed evidence on the efficacy and safety of the anti-malaria drug chloroquine [ 27 ]. It identified 23 ongoing trials investigating the potential of chloroquine as a therapeutic option for COVID-19, but no verifiable clinical outcomes data. The use of mesenchymal stem cells, antifungals, and glucocorticoids were described in four reviews [ 25 , 34 , 35 , 38 ].

Laboratory and radiological findings

Of the 18 reviews included in this overview, eight analyzed laboratory parameters in patients with COVID-19 [ 25 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 39 ]; elevated C-reactive protein levels, associated with lymphocytopenia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, as well as slightly elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferase (AST, ALT) were commonly described in those eight reviews. Lippi et al. assessed cardiac troponin I (cTnI) [ 25 ], procalcitonin [ 32 ], and platelet count [ 33 ] in COVID-19 patients. Elevated levels of procalcitonin [ 32 ] and cTnI [ 30 ] were more likely to be associated with a severe disease course (requiring intensive care unit admission and intubation). Furthermore, thrombocytopenia was frequently observed in patients with complicated COVID-19 infections [ 33 ].

Chest imaging (chest radiography and/or computed tomography) features were assessed in six reviews, all of which described a frequent pattern of local or bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacity [ 25 , 34 , 35 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. Those six reviews showed that septal thickening, bronchiectasis, pleural and cardiac effusions, halo signs, and pneumothorax were observed in patients suffering from COVID-19.

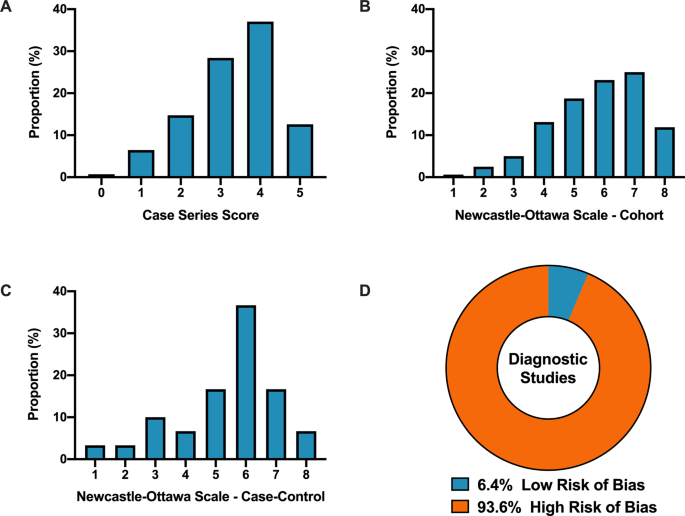

Quality of evidence in individual systematic reviews

Table 3 shows the detailed results of the quality assessment of 18 systematic reviews, including the assessment of individual items and summary assessment. A detailed explanation for each decision in each review is available in Additional file 5 .

Using AMSTAR 2 criteria, confidence in the results of all 18 reviews was rated as “critically low” (Table 3 ). Common methodological drawbacks were: omission of prospective protocol submission or publication; use of inappropriate search strategy: lack of independent and dual literature screening and data-extraction (or methodology unclear); absence of an explanation for heterogeneity among the studies included; lack of reasons for study exclusion (or rationale unclear).

Risk of bias assessment, based on a reported methodological tool, and quality of evidence appraisal, in line with the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) method, were reported only in one review [ 25 ]. Five reviews presented a table summarizing bias, using various risk of bias tools [ 25 , 29 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. One review analyzed “study quality” [ 37 ]. One review mentioned the risk of bias assessment in the methodology but did not provide any related analysis [ 28 ].

This overview of systematic reviews analyzed the first 18 systematic reviews published after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, up to March 24, 2020, with primary studies involving more than 60,000 patients. Using AMSTAR-2, we judged that our confidence in all those reviews was “critically low”. Ten reviews included meta-analyses. The reviews presented data on clinical manifestations, laboratory and radiological findings, and interventions. We found no systematic reviews on the utility of diagnostic tests.

Symptoms were reported in seven reviews; most of the patients had a fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia or muscle fatigue, and gastrointestinal disorders such as diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting. Olfactory dysfunction (anosmia or dysosmia) has been described in patients infected with COVID-19 [ 43 ]; however, this was not reported in any of the reviews included in this overview. During the SARS outbreak in 2002, there were reports of impairment of the sense of smell associated with the disease [ 44 , 45 ].

The reported mortality rates ranged from 0.3 to 14% in the included reviews. Mortality estimates are influenced by the transmissibility rate (basic reproduction number), availability of diagnostic tools, notification policies, asymptomatic presentations of the disease, resources for disease prevention and control, and treatment facilities; variability in the mortality rate fits the pattern of emerging infectious diseases [ 46 ]. Furthermore, the reported cases did not consider asymptomatic cases, mild cases where individuals have not sought medical treatment, and the fact that many countries had limited access to diagnostic tests or have implemented testing policies later than the others. Considering the lack of reviews assessing diagnostic testing (sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of RT-PCT or immunoglobulin tests), and the preponderance of studies that assessed only symptomatic individuals, considerable imprecision around the calculated mortality rates existed in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Few reviews included treatment data. Those reviews described studies considered to be at a very low level of evidence: usually small, retrospective studies with very heterogeneous populations. Seven reviews analyzed laboratory parameters; those reviews could have been useful for clinicians who attend patients suspected of COVID-19 in emergency services worldwide, such as assessing which patients need to be reassessed more frequently.

All systematic reviews scored poorly on the AMSTAR 2 critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews. Most of the original studies included in the reviews were case series and case reports, impacting the quality of evidence. Such evidence has major implications for clinical practice and the use of these reviews in evidence-based practice and policy. Clinicians, patients, and policymakers can only have the highest confidence in systematic review findings if high-quality systematic review methodologies are employed. The urgent need for information during a pandemic does not justify poor quality reporting.

We acknowledge that there are numerous challenges associated with analyzing COVID-19 data during a pandemic [ 47 ]. High-quality evidence syntheses are needed for decision-making, but each type of evidence syntheses is associated with its inherent challenges.

The creation of classic systematic reviews requires considerable time and effort; with massive research output, they quickly become outdated, and preparing updated versions also requires considerable time. A recent study showed that updates of non-Cochrane systematic reviews are published a median of 5 years after the publication of the previous version [ 48 ].

Authors may register a review and then abandon it [ 49 ], but the existence of a public record that is not updated may lead other authors to believe that the review is still ongoing. A quarter of Cochrane review protocols remains unpublished as completed systematic reviews 8 years after protocol publication [ 50 ].

Rapid reviews can be used to summarize the evidence, but they involve methodological sacrifices and simplifications to produce information promptly, with inconsistent methodological approaches [ 51 ]. However, rapid reviews are justified in times of public health emergencies, and even Cochrane has resorted to publishing rapid reviews in response to the COVID-19 crisis [ 52 ]. Rapid reviews were eligible for inclusion in this overview, but only one of the 18 reviews included in this study was labeled as a rapid review.

Ideally, COVID-19 evidence would be continually summarized in a series of high-quality living systematic reviews, types of evidence synthesis defined as “ a systematic review which is continually updated, incorporating relevant new evidence as it becomes available ” [ 53 ]. However, conducting living systematic reviews requires considerable resources, calling into question the sustainability of such evidence synthesis over long periods [ 54 ].

Research reports about COVID-19 will contribute to research waste if they are poorly designed, poorly reported, or simply not necessary. In principle, systematic reviews should help reduce research waste as they usually provide recommendations for further research that is needed or may advise that sufficient evidence exists on a particular topic [ 55 ]. However, systematic reviews can also contribute to growing research waste when they are not needed, or poorly conducted and reported. Our present study clearly shows that most of the systematic reviews that were published early on in the COVID-19 pandemic could be categorized as research waste, as our confidence in their results is critically low.

Our study has some limitations. One is that for AMSTAR 2 assessment we relied on information available in publications; we did not attempt to contact study authors for clarifications or additional data. In three reviews, the methodological quality appraisal was challenging because they were published as letters, or labeled as rapid communications. As a result, various details about their review process were not included, leading to AMSTAR 2 questions being answered as “not reported”, resulting in low confidence scores. Full manuscripts might have provided additional information that could have led to higher confidence in the results. In other words, low scores could reflect incomplete reporting, not necessarily low-quality review methods. To make their review available more rapidly and more concisely, the authors may have omitted methodological details. A general issue during a crisis is that speed and completeness must be balanced. However, maintaining high standards requires proper resourcing and commitment to ensure that the users of systematic reviews can have high confidence in the results.

Furthermore, we used adjusted AMSTAR 2 scoring, as the tool was designed for critical appraisal of reviews of interventions. Some reviews may have received lower scores than actually warranted in spite of these adjustments.

Another limitation of our study may be the inclusion of multiple overlapping reviews, as some included reviews included the same primary studies. According to the Cochrane Handbook, including overlapping reviews may be appropriate when the review’s aim is “ to present and describe the current body of systematic review evidence on a topic ” [ 12 ], which was our aim. To avoid bias with summarizing evidence from overlapping reviews, we presented the forest plots without summary estimates. The forest plots serve to inform readers about the effect sizes for outcomes that were reported in each review.

Several authors from this study have contributed to one of the reviews identified [ 25 ]. To reduce the risk of any bias, two authors who did not co-author the review in question initially assessed its quality and limitations.

Finally, we note that the systematic reviews included in our overview may have had issues that our analysis did not identify because we did not analyze their primary studies to verify the accuracy of the data and information they presented. We give two examples to substantiate this possibility. Lovato et al. wrote a commentary on the review of Sun et al. [ 41 ], in which they criticized the authors’ conclusion that sore throat is rare in COVID-19 patients [ 56 ]. Lovato et al. highlighted that multiple studies included in Sun et al. did not accurately describe participants’ clinical presentations, warning that only three studies clearly reported data on sore throat [ 56 ].

In another example, Leung [ 57 ] warned about the review of Li, L.Q. et al. [ 29 ]: “ it is possible that this statistic was computed using overlapped samples, therefore some patients were double counted ”. Li et al. responded to Leung that it is uncertain whether the data overlapped, as they used data from published articles and did not have access to the original data; they also reported that they requested original data and that they plan to re-do their analyses once they receive them; they also urged readers to treat the data with caution [ 58 ]. This points to the evolving nature of evidence during a crisis.

Our study’s strength is that this overview adds to the current knowledge by providing a comprehensive summary of all the evidence synthesis about COVID-19 available early after the onset of the pandemic. This overview followed strict methodological criteria, including a comprehensive and sensitive search strategy and a standard tool for methodological appraisal of systematic reviews.

In conclusion, in this overview of systematic reviews, we analyzed evidence from the first 18 systematic reviews that were published after the emergence of COVID-19. However, confidence in the results of all the reviews was “critically low”. Thus, systematic reviews that were published early on in the pandemic could be categorized as research waste. Even during public health emergencies, studies and systematic reviews should adhere to established methodological standards to provide patients, clinicians, and decision-makers trustworthy evidence.

Availability of data and materials

All data collected and analyzed within this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

World Health Organization. Timeline - COVID-19: Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline . Accessed 1 June 2021.

COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Anzai A, Kobayashi T, Linton NM, Kinoshita R, Hayashi K, Suzuki A, et al. Assessing the Impact of Reduced Travel on Exportation Dynamics of Novel Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19). J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):601.

Chinazzi M, Davis JT, Ajelli M, Gioannini C, Litvinova M, Merler S, et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020;368(6489):395–400. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9757 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fidahic M, Nujic D, Runjic R, Civljak M, Markotic F, Lovric Makaric Z, et al. Research methodology and characteristics of journal articles with original data, preprint articles and registered clinical trial protocols about COVID-19. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-01047-2 .

EPPI Centre . COVID-19: a living systematic map of the evidence. Available at: http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Projects/DepartmentofHealthandSocialCare/Publishedreviews/COVID-19Livingsystematicmapoftheevidence/tabid/3765/Default.aspx . Accessed 1 June 2021.

NCBI SARS-CoV-2 Resources. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sars-cov-2/ . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Gustot T. Quality and reproducibility during the COVID-19 pandemic. JHEP Rep. 2020;2(4):100141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100141 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kodvanj, I., et al., Publishing of COVID-19 Preprints in Peer-reviewed Journals, Preprinting Trends, Public Discussion and Quality Issues. Preprint article. bioRxiv 2020.11.23.394577; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.23.394577 .

Dobler CC. Poor quality research and clinical practice during COVID-19. Breathe (Sheff). 2020;16(2):200112. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0112-2020 .

Article Google Scholar

Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 2010;7(9):e1000326. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326 .

Lunny C, Brennan SE, McDonald S, McKenzie JE. Toward a comprehensive evidence map of overview of systematic review methods: paper 1-purpose, eligibility, search and data extraction. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):231. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0617-1 .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane. 2020. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane. 2020; Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Newton AS, Scott SD, Hartling L. The impact of different inclusion decisions on the comprehensiveness and complexity of overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0914-3 .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Newton AS, Scott SD, Hartling L. A decision tool to help researchers make decisions about including systematic reviews in overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0768-8 .

Hunt H, Pollock A, Campbell P, Estcourt L, Brunton G. An introduction to overviews of reviews: planning a relevant research question and objective for an overview. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0695-8 .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Pieper D, Tricco AC, Gates M, Gates A, et al. Preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews (PRIOR): a protocol for development of a reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):335. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1252-9 .

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123–30.

Krnic Martinic M, Pieper D, Glatt A, Puljak L. Definition of a systematic review used in overviews of systematic reviews, meta-epidemiological studies and textbooks. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):203. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0855-0 .

Puljak L. If there is only one author or only one database was searched, a study should not be called a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:4–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.08.002 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gates M, Gates A, Guitard S, Pollock M, Hartling L. Guidance for overviews of reviews continues to accumulate, but important challenges remain: a scoping review. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):254. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01509-0 .

Covidence - systematic review software. Available at: https://www.covidence.org/ . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Borges do Nascimento IJ, et al. Novel Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19) in Humans: A Scoping Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):941.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJ, Mao YP, Ye RX, Wang QZ, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x .

Cortegiani A, Ingoglia G, Ippolito M, Giarratano A, Einav S. A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. J Crit Care. 2020;57:279–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.005 .

Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, Zhi L, Wang X, Liu L, et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109(5):531–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Li LQ, Huang T, Wang YQ, Wang ZP, Liang Y, Huang TB, et al. COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):577–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25757 .

Lippi G, Lavie CJ, Sanchis-Gomar F. Cardiac troponin I in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): evidence from a meta-analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63(3):390–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2020.03.001 .

Lippi G, Henry BM. Active smoking is not associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Eur J Intern Med. 2020;75:107–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2020.03.014 .

Lippi G, Plebani M. Procalcitonin in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;505:190–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.004 .

Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;506:145–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022 .

Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(6):1088–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15270 .

Lupia T, Scabini S, Mornese Pinna S, di Perri G, de Rosa FG, Corcione S. 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak: a new challenge. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;21:22–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2020.02.021 .

Marasinghe, K.M., A systematic review investigating the effectiveness of face mask use in limiting the spread of COVID-19 among medically not diagnosed individuals: shedding light on current recommendations provided to individuals not medically diagnosed with COVID-19. Research Square. Preprint article. doi : https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-16701/v1 . 2020 .

Mullins E, Evans D, Viner RM, O’Brien P, Morris E. Coronavirus in pregnancy and delivery: rapid review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55(5):586–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.22014 .

Pang J, Wang MX, Ang IYH, Tan SHX, Lewis RF, Chen JIP, et al. Potential Rapid Diagnostics, Vaccine and Therapeutics for 2019 Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):623.

Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, Villamizar-Peña R, Holguin-Rivera Y, Escalera-Antezana JP, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;34:101623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623 .

Salehi S, Abedi A, Balakrishnan S, Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review of imaging findings in 919 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;215(1):87–93. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.20.23034 .

Sun P, Qie S, Liu Z, Ren J, Li K, Xi J. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a single arm meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):612–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25735 .

Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z, Guo Q, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017 .

Bassetti M, Vena A, Giacobbe DR. The novel Chinese coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections: challenges for fighting the storm. Eur J Clin Investig. 2020;50(3):e13209. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13209 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hwang CS. Olfactory neuropathy in severe acute respiratory syndrome: report of a case. Acta Neurol Taiwanica. 2006;15(1):26–8.

Google Scholar

Suzuki M, Saito K, Min WP, Vladau C, Toida K, Itoh H, et al. Identification of viruses in patients with postviral olfactory dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(2):272–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000249922.37381.1e .

Rajgor DD, Lee MH, Archuleta S, Bagdasarian N, Quek SC. The many estimates of the COVID-19 case fatality rate. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):776–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30244-9 .

Wolkewitz M, Puljak L. Methodological challenges of analysing COVID-19 data during the pandemic. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-00972-6 .

Rombey T, Lochner V, Puljak L, Könsgen N, Mathes T, Pieper D. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of non-Cochrane updates of systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study. Res Synth Methods. 2020;11(3):471–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1409 .

Runjic E, Rombey T, Pieper D, Puljak L. Half of systematic reviews about pain registered in PROSPERO were not published and the majority had inaccurate status. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;116:114–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.08.010 .

Runjic E, Behmen D, Pieper D, Mathes T, Tricco AC, Moher D, et al. Following Cochrane review protocols to completion 10 years later: a retrospective cohort study and author survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:41–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.006 .

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):224. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6 .

COVID-19 Rapid Reviews: Cochrane’s response so far. Available at: https://training.cochrane.org/resource/covid-19-rapid-reviews-cochrane-response-so-far . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Cochrane. Living systematic reviews. Available at: https://community.cochrane.org/review-production/production-resources/living-systematic-reviews . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Millard T, Synnot A, Elliott J, Green S, McDonald S, Turner T. Feasibility and acceptability of living systematic reviews: results from a mixed-methods evaluation. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):325. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1248-5 .

Babic A, Poklepovic Pericic T, Pieper D, Puljak L. How to decide whether a systematic review is stable and not in need of updating: analysis of Cochrane reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2020;11(6):884–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1451 .

Lovato A, Rossettini G, de Filippis C. Sore throat in COVID-19: comment on “clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a single arm meta-analysis”. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):714–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25815 .

Leung C. Comment on Li et al: COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(9):1431–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25912 .

Li LQ, Huang T, Wang YQ, Wang ZP, Liang Y, Huang TB, et al. Response to Char’s comment: comment on Li et al: COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(9):1433. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25924 .

Download references

Acknowledgments

We thank Catherine Henderson DPhil from Swanscoe Communications for pro bono medical writing and editing support. We acknowledge support from the Covidence Team, specifically Anneliese Arno. We thank the whole International Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19) for their commitment and involvement. Members of the InterNetCOVID-19 are listed in Additional file 6 . We thank Pavel Cerny and Roger Crosthwaite for guiding the team supervisor (IJBN) on human resources management.

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University Hospital and School of Medicine, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento & Milena Soriano Marcolino

Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA

Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento

Helene Fuld Health Trust National Institute for Evidence-based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare, College of Nursing, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

Dónal P. O’Mathúna

School of Nursing, Psychotherapy and Community Health, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care and Pain Medicine, University of Münster, Münster, Germany

Thilo Caspar von Groote

Department of Sport and Health Science, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany

Hebatullah Mohamed Abdulazeem

School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Health and Medicine, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, Australia

Ishanka Weerasekara

Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka

Cochrane Croatia, University of Split, School of Medicine, Split, Croatia

Ana Marusic, Irena Zakarija-Grkovic & Tina Poklepovic Pericic

Center for Evidence-Based Medicine and Health Care, Catholic University of Croatia, Ilica 242, 10000, Zagreb, Croatia

Livia Puljak

Cochrane Brazil, Evidence-Based Health Program, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Vinicius Tassoni Civile & Alvaro Nagib Atallah

Yorkville University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada

Santino Filoso

Laboratory for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (LIAM), Department of Mathematics and Statistics, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Nicola Luigi Bragazzi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

IJBN conceived the research idea and worked as a project coordinator. DPOM, TCVG, HMA, IW, AM, LP, VTC, IZG, TPP, ANA, SF, NLB and MSM were involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and initial draft writing. All authors revised the manuscript critically for the content. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Livia Puljak .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not required as data was based on published studies.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: appendix 1..

Search strategies used in the study.

Additional file 2: Appendix 2.

Adjusted scoring of AMSTAR 2 used in this study for systematic reviews of studies that did not analyze interventions.

Additional file 3: Appendix 3.

List of excluded studies, with reasons.

Additional file 4: Appendix 4.

Table of overlapping studies, containing the list of primary studies included, their visual overlap in individual systematic reviews, and the number in how many reviews each primary study was included.

Additional file 5: Appendix 5.

A detailed explanation of AMSTAR scoring for each item in each review.

Additional file 6: Appendix 6.

List of members and affiliates of International Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Borges do Nascimento, I.J., O’Mathúna, D.P., von Groote, T.C. et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Infect Dis 21 , 525 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06214-4

Download citation

Received : 12 April 2020

Accepted : 19 May 2021

Published : 04 June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06214-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Coronavirus

- Evidence-based medicine

- Infectious diseases

BMC Infectious Diseases

ISSN: 1471-2334

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

REVIEW article

Coronavirus disease (covid-19): comprehensive review of clinical presentation.

- 1 Department of Medicine, King Edward Medical University/ Mayo Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan

- 2 Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, Post-Graduate Medical Institute/LGH, Lahore, Pakistan

- 3 Rajarshee Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj Government Medical College, Kolhapur, India

- 4 Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tlemcen, Tlemcen, Algeria

- 5 School of Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki, Japan

- 6 Institute of Research and Development, Duy Tan University, Da Nang, Vietnam

COVID-19 is a rapidly growing pandemic with its first case identified during December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. Due to the rampant rise in the number of cases in China and globally, WHO declared COVID-19 as a pandemic on 11th March 2020. The disease is transmitted via respiratory droplets of infected patients during coughing or sneezing and affects primarily the lung parenchyma. The spectrum of clinical manifestations can be seen in COVID-19 patients ranging from asymptomatic infections to severe disease resulting in mortality. Although respiratory involvement is most common in COVID-19 patients, the virus can affect other organ systems as well. The systemic inflammation induced by the disease along with multisystem expression of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2), a receptor which allows viral entry into cells, explains the manifestation of extra-pulmonary symptoms affecting the gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, hematological, renal, musculoskeletal, and endocrine system. Here, we have reviewed the extensive literature available on COVID-19 about various clinical presentations based on the organ system involved as well as clinical presentation in specific population including children, pregnant women, and immunocompromised patients. We have also briefly discussed about the Multisystemic Inflammatory Syndrome occurring in children and adults with COVID-19. Understanding the various clinical presentations can help clinicians diagnose COVID-19 in an early stage and ensure appropriate measures to be undertaken in order to prevent further spread of the disease.

Introduction

COVID-19 is a growing pandemic with initial cases identified in Wuhan, Hubei province, China toward the end of December 2019. Labeled as Novel Coronavirus 2019 (2019-nCoV) initially by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) which was subsequently renamed as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) due to its homology with SARS-CoV by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) ( 1 , 2 ). The World Health Organization (WHO) later renamed the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 as Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) ( 3 ). COVID-19 is primarily a disease of the respiratory system affecting lung parenchyma with fever, cough, and shortness of breath as the predominant symptoms. Recent studies have shown that it can affect multiple organ systems and cause development of extra-pulmonary symptoms. Presence of extra-pulmonary symptoms can often lead to late diagnosis and sometimes even mis-diagnosis of COVID-19 which can be detrimental to patients. As researchers globally continue to understand COVID-19 and its implications on the human body, knowledge about the various clinical presentations of COVID-19 is paramount in early diagnosing and treatment in order to decrease the morbidity and mortality caused by the disease.

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

While studying the early transmission dynamics of COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, many cases were found to be linked to the Huanan wholesale seafood market. Further investigation revealed <10% of the total cases could be linked to the market which led to the conclusion of human-to-human transmission of the virus occurring through respiratory droplets and contact transmission contributing to the rise in the number of affected individuals ( 4 ). The exponential rise in the number of cases in China and reporting of cases outside China in multiple countries led WHO to declare COVID-19 as a pandemic on 11th March 2020 ( 5 ).

SARS-CoV-2 tends to infect all age groups and is transmitted via direct contact or respiratory droplets generated during coughing or sneezing by the infected patient during both symptomatic or pre-symptomatic phase of infection. Other routes of transmission include fecal-oral route and fomites along with small risk of vertical transmission from mother to child if infection occurs during third trimester of pregnancy ( 6 , 7 ). There has also been evidence of asymptomatic transmission of COVID-19 ( 8 ). The concept of super spreaders in relation to COVID-19 is emerging where a single individual either symptomatic or asymptomatic can infect a disproportionately large number of individuals in an appropriate super spreading conditions such as mass gathering due to production of large number of infectious agent for prolonged duration of time ( 9 ). As per the literature, the incubation period of COVID-19 ranges from 2 to 14 days with a mean incubation period of 3 days ( 10 ). The basic Reproduction number (Ro) of SARS-CoV-2 is 2–2.5. Each individual infected with COVID-19 can infect 2–2.5 other individuals in a naïve population which also explains the exponential growth in the number of cases ( 10 ). The disease tends to be of mild to moderate severity in roughly 80% of patients, and severe disease is associated with infants, elderly patients above 65 years, and patients with other comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and other chronic conditions ( 1 , 2 ). COVID-19 has also been found to be more severe in males than in females with a case fatality rate of 2.8% in males and 1.7% in females ( 11 ). The major organ system affected by the virus is the respiratory system, but it can affect other organ systems either directly or by the effect of host immune response. SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, after entering the human host initially replicates in the epithelial mucosa of the upper respiratory tract (nose and pharynx) followed by migration to the lungs where further replication of virus occurs causing transient viraemia. The virus uses Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor as a primary entry to cells. ACE2 is found abundantly in the mucosal lining of the respiratory tract, vascular endothelial cells, heart, intestine, and kidney. Thus, the virus has potential for replication in all these organs. After entry into cells, the virus undergoes further rapid replication within the target cells and induces extensive epithelial and endothelial dysfunction leading to exponential inflammatory response with the production of a large amount of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Activation of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines leads to neutrophil activation and migrations and results in the characteristic cytokine storm. The immunological downregulation of ACE2 by the virus contributes to acute lung injury in COVID-19. ACE2 also regulates the renin angiotensin system (RAS); thus, downregulation of ACE2 also causes dysfunction of RAS which contributes to enhanced inflammation ( 2 , 11 – 15 ). These entire factors contribute to symptoms of COVID-19 with sepsis, multi-organ dysfunction, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and prothrombotic state leading to an exacerbation of organ dysfunction.

Clinical Manifestation

We review here the system based clinical features of COVID-19.

Respiratory

According to report from WHO-China-Joint Mission on COVID-19, 55,924 laboratories confirmed cases of COVID-19 had fever (87.9%), dry cough (67.7%), fatigue (38.1%), sputum production (33.4%), difficulty breathing (18.6%), sore throat (13.9%), chills (11.4%), nasal congestion (4.8%), and hemoptysis (0.9%) ( 1 ).

Some patients may rapidly progress to acute lung injury and ARDS with septic shock. The median interval between the onset of initial symptoms to development of dyspnea, hospital admission, and ARDS was 5, 7, and 8 days respectively ( 10 ). Some patients with COVID-19 may have reduced oxygen saturation in blood (≤ 93%) with oxygen saturation down to 50 or 60% but remained stable without significant distress, and as such, were termed as salient hypoxia or happy hypoxia ( 16 , 17 ). Trial of oxygen therapy, prone positioning, high flow continuous positive airway pressure, non-re-breathable mask alongside trial of anticoagulation are often used to manage these patients ( 16 , 17 ). However, further study is required to define the role of these strategies in management.

The most frequent radiological abnormality among 975 patients with COVID-19 in computed tomography (CT) scan of chest was ground glass opacity (56.4%) and bilateral patchy shadowing (51.8%) ( 18 ). A scientific review of 2,814 patients have shown that the most common chest CT finding in COVID-19 patients was ground glass opacity followed by consolidation. However, the findings can vary in different patients and at various stages of diseases. Other CT findings include interlobular septal thickening, reticular pattern, crazy paving, etc. Atypical findings like air bronchogram, bronchial wall thickening, nodule, pleural effusion, and lymphadenopathy have also been noted in some studies ( 19 ). A study showed that among 877 patients with non-severe diseases and 173 patients with severe diseases, 17.9 and 2.9% of the patients did not have any detectable radiological abnormalities, respectively ( 18 ).

ENT (Ear, Nose, and Throat)

ENT manifestations are one of the most frequent symptoms encountered by physicians in COVID-19. A peculiar clinical presentation in some COVID-19 patients includes the deterioration of sense, taste (dysgeusia), and loss of smell (anosmia). A systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 studies with 1,627 participants surveyed for olfactory deterioration and 9 studies with 1,390 participants examined for gustatory symptoms demonstrated prevalence of 52.73 and 43.93% of these symptoms among COVID-19 patients, respectively. These clinical features may often present at earlier stages of the disease ( 20 ). Additionally, sore throat, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, tonsil edema, and enlarged cervical lymph nodes are commonly seen among otolaryngological dysfunctions in patients ( 21 ). A large observational study of 1,099 COVID-19 patients reported tonsils swelling in 23 patients (2.1%), throat congestion in 19 patients (1.7%) and enlarged lymph nodes in 2 patients (0.2%) ( 18 ). This can be explained by the fact that there is a high expression of ACE2 receptors on the epithelial cells of the oral and nasal mucosa including the tongue. It has been known that the novel coronavirus has a strong binding affinity to ACE2 receptors through which it invades host cells ( 22 ). This theory may explain the exhibition of extra-respiratory symptoms including ENT manifestations as part of COVID-19 symptoms.

Cardiovascular

Cardiac manifestation in patient with COVID-19 can occur due to cardiac strain secondary to hypoxia and respiratory failure, direct effect of SARS-CoV-2 on heart or secondary to inflammation and cytokine storm, metabolic derangements, rupture of plaque and coronary occlusion by thrombus, and consequences of drugs used for treatment ( 23 – 25 ). The need for intensive care admission, non-invasive ventilation (46.3 vs. 3.9%), and invasive mechanical ventilation (22 vs. 4.2%) were higher among patients with cardiac ailments as compared to those without cardiac involvement as well as higher hospital mortality than those without myocardial involvement (51.2 vs. 4.5%) ( 26 ). These patients tend to have electrocardiographic (ECG) changes as well as elevations in high sensitivity cardiac troponin (hsCTn) and N- terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT proBNP) which corresponded to raised inflammatory markers. Hypertension, acute and fulminant myocarditis, ventricular arrhythmias, atrial fibrillation, stress cardiomyopathy, hypotension and heart failure, acute coronary syndrome (ACS) with ST elevation or depression MI with normal coronaries have been reported ( 23 , 27 ). In a Chinese cohort of 138 patients, 16.7% had arrhythmias with risk higher among those needing ICU care with no mention of the type of arrhythmia that was present ( 28 ). Less frequently, cardiac symptoms like chest pain or tightness and palpitation can be the initial presenting features without fever producing a diagnostic dilemma. Some of these patients eventually go on to develop respiratory symptoms as diseases progress ( 29 ). Patients who have recovered from acute illness may develop arrhythmias as a result of myocardial scar and need future monitoring ( 27 ). One important point to note is use of Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System (RAAS) modulators in patients with COVID-19. Guidelines from ACC/AHA/HFSA recommends continuing them in high risk patient based on goal directed therapy approach supported by a recent systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Hasan et. Al. which demonstrated use of ACEI/ARB in COVID-19 patients is associated with lower odds/ hazards of mortality and development of severe/critical diseases as compared to no use of ACEI/ARB ( 30 , 31 ).

Gastrointestinal

In the initial cohort of patients from China, nausea or vomiting and diarrhea were present in 5 and 3.7% of patients ( 1 ). Review of data from 2,023 patients showed anorexia to be the most frequently occurring gastrointestinal symptom in adults. Diarrhea was the most common presenting gastrointestinal symptom in both adults and children while vomiting was found to be more common in children ( 32 ). Other rare symptoms included nausea, abdominal pain, and gastrointestinal bleeding. There have been few instances where COVID-19 patients presented with only gastrointestinal symptoms without the development of fever or respiratory symptoms at the onset and during disease progression ( 33 ). In a smaller cohort of 204 patients, 50.5% had some form of intestinal symptoms and of those, 5.8% had only intestinal symptoms while the remaining patients developed respiratory symptoms subsequently. The most common symptoms reported among them was anorexia (78.64%), non-dehydrating diarrhea (34%), vomiting (3.9%), and abdominal pain (1.94%) ( 34 ). In addition, those with GI symptoms tend to have a longer interval between symptom onset and hospital admission (9 vs. 7.3 days) possibly due to lack of clinical suspicion and delay in diagnosis. Patients with gastrointestinal symptoms tend to have higher elevation in AST and ALT indicating coexistent liver injury ( 34 ). The mechanism behind GI illness is not clearly known but could be due to direct invasion of virus via ACE2 receptor in the intestinal mucosa. This can be supported by the fact that viral RNA can be detected in stool samples of COVID-19 patients which may also hint toward possible fecal-oral transmission ( 35 ). Liver dysfunction is likely secondary to the use of hepatotoxic drugs, hypoxia induced liver injury, systemic inflammation, and multi organ failure ( 36 ).

Renal manifestation in patients with COVID-19 can occur due to direct invasion of podocytes and proximal tubular cells by SARS-CoV-2 virus, secondary endothelial dysfunction causing effacement of foot process with vacuolation and detachment of podocytes, and acute proximal tubular dysfunction ( 37 ). Furthermore, hypoxia, cytokine storm, rhabdomyolysis, nephrotoxic drugs, and overlying infections can all exacerbate renal injury ( 38 ). Based on initial reports, prevalence of Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) among COVID-19 hospitalized patients range from 0.5 to 29%. In a cohort of 701 patients, proteinuria (43.9%), hematuria (26.7%), elevated creatinine (14.4%), elevated blood urea nitrogen (13.1%), and low glomerular filtration rate (≤ 60 ml/min/1.73 m 2 ) (13.1%) were present at the time of hospital admission with 5.1% developing AKI during the illness. AKI was more prevalent among those with baseline renal impairment ( 39 ). In another large cohort of 5,449 patients, 36.6% had AKI with prevalence higher among mechanically ventilated patients compared to non-ventilated patients (89.7 vs. 21.7%) ( 40 ). Patients developing renal impairment are prone to have higher mortality within the hospital. Another point to highlight is the presentation of COVID-19 in renal transplant recipients. Due to immunosuppression, these patients are likely to have low fever at presentation with swift clinical decline and requirement for mechanical ventilation with high mortality as compared to the general population ( 41 ).

Neurological

Most patients with COVID-19 develop neurological symptoms along with respiratory symptoms during the course of illness; however, several case reports in review of literature document patient presentation of neurological dysfunction without typical symptoms of fever, cough, and difficulty breathing ( 42 ). There is a 2.5-fold enhanced risk of severe illness and increased death in patients with a history of previous stroke with similar findings among those with Parkinson's diseases. The prevalence of neurological features ranges from 6 to 36% along with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy up to 20% in some series of patients ( 43 ). Neurological symptoms tend to occur early in the course of illness (median 1–2 days) with most common neurological features being headache, confusion, delirium, anosmia or hyposmia, dysgeusia or ageusia, altered mental status, ataxia, and seizures ( 44 ). Among patients admitted with COVID-19, the prevalence of ischemic stroke ranges from 2.5 to 5% despite receiving prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism. Patients prone to have established cardiovascular risk factors are likely to have a more severe diseases ( 43 ). Other presentations include viral encephalitis, acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE), infectious toxic encephalopathy, meningitis, Guillain Barre Syndrome (GBS), Miller Fisher syndrome, and polyneuritis cranialis with GBS being the first feature of COVID-19 in few cases ( 42 , 43 , 45 ). In COVID-19 patients, CNS features are possibly due to direct invasion of neurons and glial cells by SARS-CoV-2 as well as by endothelial dysfunction of blood brain barrier (BBB). Virus can gain access to CNS via hematogenous spread or retrograde movement across the olfactory bulb. The virus can be detected in CSF by RT-PCR and on brain parenchyma during autopsy. The fact that most patients develop anosmia or hyposmia during illness support this theory ( 45 ). After entry, the virus can cause reactive gliosis with activation of the inflammatory cascade. The combination of systemic inflammation, cytokine storm, and coagulation dysfunction can impair BBB function and alter brain equilibrium causing neuronal death ( 42 ).

Ocular manifestations can vary from conjunctival injection to frank conjunctivitis. In a Chinese cohort of 38 patients, 31.6% had ocular symptoms consisting primarily of conjunctivitis while conjunctival hyperemia, foreign body sensation in eye, chemosis, tearing or epiphora were more common among severe COVID-19 patients. Among them SARS-CoV-2 can be demonstrated in conjunctival as well as nasopharyngeal swab in 5.2% of patients, indicating a potential route for viral transmission ( 46 ). Conjunctivitis or tearing can be the initial presenting symptoms of COVID-19. Despite this fact, there is no documented case of severe ocular features relating to COVID-19.

Similar to other viral infections, SARS-CoV-2 can also produce varied dermatological features. A study of 88 patients from Italy showed that about 20.4% had some form of skin manifestations with 44.4% developing features at onset and duration of the disease progression ( 47 ). Maculopapular exanthem (36.1%) was identified as most common dermatological features followed by papulovesicular rash (34.7%), painful acral red purple papules (15.3%), urticaria (9.7%), livedo reticularis (2.8%), and petechiae (1.4%) ( 48 ). A study of 375 COVID-19 cases in Spain identified five different patterns of cutaneous manifestations in patients: acral areas of erythema with vesicles or pustules (pseudo-chilblain) (19%), other vesicular eruptions (9%), urticarial lesions (19%), maculopapular eruptions (47%), and livedo or necrosis (6%) ( 49 ). Majority of patients had lesions on the trunk with some experiencing lesions on hands and feet. There are case reports of COVID-19 associated with erythema multiforme and Kawasaki Disease in children ( 50 , 51 ). Pathogenesis behind skin involvement remains unclear with some features explained by small vessel vasculitis, thrombotic events like DIC, hyaline thrombus formation, acral ischemia, or the direct effect of the virus like other viral illnesses ( 52 ).

Musculoskeletal

The initial report from China revealed 14.8% of patients had myalgia or arthralgia among 55,924 COVID-19 patients. A review article reports that of 12,046 patients, fatigue was identified in 25.6% and myalgia and/or arthralgia in 15.5% with most patients reporting symptoms from the start of illness ( 53 ). There are reports suggesting myositis and rhabdomyolysis with markedly elevated creatinine kinase can occur during COVID-19 illness especially in patients with severe diseases and multi organ failure. Additionally, in some patients, rhabdomyolysis has been documented as the initial presentation of COVID-19 illness without typical respiratory symptoms ( 54 , 55 ). A case series of four patients developing acute arthritis during hospital admission for COVID-19 has been reported with exacerbation of crystal arthropathy (gout and calcium pyrophosphate diseases) but negative for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR in synovial fluid ( 56 ). Treatment with steroids and colchicine was used in all four cases. An important consideration to note was that all four patients developed arthritis despite previous treatment with immunomodulatory therapy (hydroxychloroquine, tocilizumab, and pulse methylprednisolone).

Hematological

As stated, COVID-19 is a systemic disease inducing systemic inflammation and occasionally cytokine storm. This can significantly impact the process of hematopoiesis and hemostasis. During early disease, normal or decreased leukocyte and lymphocyte counts were documented with marked lymphopenia as the diseases progressed, especially in those with cytokine storms and severe disease. In a study of 1,099 patients, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia were present in 83.2, 36.2, and 33.7%, respectively, with findings more marked in those with severe diseases ( 18 ). Leukocytosis in COVID-19 patients might suggest a bacterial infection or a superinfection with leukocytosis found more commonly in severe cases (11.4%) as compared to mild and moderate cases (4.8%) ( 18 ). Similarly, thrombocytopenia has been found to be more common (57.7%) in severe cases in contrast to mild and moderate cases (31.6%) ( 18 ). Lymphopenia was also linked with an increased necessity for ICU admission and the risk of ARDS. Thrombocytosis with elevated platelet to lymphocyte ratio may indicate a more marked cytokine storm ( 57 ).