- Open access

- Published: 14 August 2020

Knowledge, attitude, and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in East Africa: a systematic review

- Jean Prince Claude Dukuzumuremyi 1 ,

- Kwabena Acheampong 2 ,

- Julius Abesig 2 &

- Jiayou Luo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9448-707X 1

International Breastfeeding Journal volume 15 , Article number: 70 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

134k Accesses

54 Citations

Metrics details

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) is recommended for the first six months of age by the World Health Organization. Mothers’ good knowledge and positive attitude play key roles in the process of exclusive breastfeeding practices. In this study, we report on a systematic review of the literature that aimed to examine the status of mothers’ knowledge, attitude, and practices related to exclusive breastfeeding in East Africa, so as to provide clues on what can be done to improve exclusive breastfeeding.

A systematic review of peer-reviewed literature was performed. The search for literature was conducted utilizing six electronic databases, Pub med, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Embase, Science Direct, and Cochrane library, for studies published in English from January 2000 to June 2019 and conducted in East Africa. Studies focused on mothers’ knowledge, attitudes, or practices related to exclusive breastfeeding. All papers were reviewed using a predesigned data extraction form.

Sixteen studies were included in the review. This review indicates that almost 96.2% of mothers had ever heard about EBF, 84.4% were aware of EBF, and 49.2% knew that the duration of EBF was the first six months only. In addition, 42.1% of mothers disagreed and 24.0% strongly disagreed that giving breast milk for a newborn immediately and within an hour is important, and 47.9% disagreed that discarding the colostrum is important. However, 42.0% of mothers preferred to feed their babies for the first six months breast milk alone. In contrast, 55.9% of them had practiced exclusive breastfeeding for at least six months.

Conclusions

Exclusively breastfeeding among our sample is suboptimal, compared to the current WHO recommendations. Thus, it is important to provide antenatal and early postpartum education and periodical breastfeeding counseling, to improve maternal attitudes and knowledge toward breastfeeding practices.

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) is defined as giving breast milk only to the infant, without any additional food or drink, not even water in the first six months of life, with the exception of mineral supplements, vitamins, or medicines [ 1 , 2 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nation Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommend initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth; exclusively breastfeed for the first six months of age and continuation of breastfeeding for up to two years of age or beyond in addition to adequate complementary foods [ 3 , 4 ].

EBF is an important public health strategy for improving children’s and mother’s health by reducing child morbidity and mortality and helping to control healthcare costs in society [ 5 ]. Additionally, EBF is one of the major strategies which help the most widely known and effective intervention for preventing early childhood deaths. Every year, optimal breastfeeding practices can prevent about 1.4 million deaths worldwide among children under five [ 6 ]. Beyond the benefits that breastfeeding confers to the mother-child relationship, breastfeeding lowers the incidence of many childhood illnesses, such as middle infections, pneumonia, sudden infant death syndrome, diabetes mellitus, malocclusion, and diarrhea [ 7 , 8 ]. Also, breastfeeding supports healthy brain development and is associated with higher performance on intelligence tests among children and adolescents [ 3 , 9 ]. In mothers, breastfeeding has been shown to decrease the frequency of hemorrhage, postpartum depression, breast cancer, ovarian and endometrial cancer, as well as facilitating weight loss [ 7 , 10 ]. The lactation amenorrhea method is an important choice for postpartum family planning [ 4 , 10 ].

The World Health Assembly (WHA) has set a global target in order to increase the rate of EBF for infants aged 0–6 months up to at least 50% in 2012–2025 [ 1 ]. Adherence to these guidelines varies globally, only 38% of infants are exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life [ 1 , 11 ]. High-income countries such as the United States (19%), United Kingdom (1%), and Australia (15%) [ 12 ], have shorter breastfeeding duration than do low-income and middle-income countries. However, even in low-income and middle-income countries, only 37% of infants younger than six months are exclusively breastfed [ 13 ]. According to recent papers in the sub-Saharan Africa region, only 53.5% of infants in east African countries were EBF for six months [ 14 ], which is way below the WHO target of 90% [ 15 ].

In addition, a study conducted in Tanzania reported that more than 91% of mothers received healthcare in the antenatal period. However, only 39% of pregnant women and 25% of postpartum mothers reported having received breastfeeding counseling [ 16 ], and many women perceived that the quantity of mothers’ breast milk is low for a child’s growth. The mothers perceived that the child is thirsty and they need to introduce herbal medicine for cultural purposes was among the important factors for early mixed feeding [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. The secondary analysis of WHO Global reported that barriers of breastfeeding in low-income countries include cultural beliefs, education, and access to healthcare [ 19 ].

Mothers’ good knowledge and positive attitude play key roles in the process of breastfeeding [ 20 ]. A previous study reported that mothers with higher knowledge of EBF were 5.9 times more likely to practice EBF than their counterparts (OR 5.9; 95% CI 2.6, 13.3; p < 0.001) [ 21 ] and higher scores of breastfeeding knowledge (OR 1.09; 95% CI 1.04–1.14), attitude (OR 1.04; 95% CI 1.00, 1.09), and practice control (OR 1.11; 95% CI 1.02, 1.20) were associated with a higher prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding [ 22 ].

Although several studies have been conducted on the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of EBF in some African countries, to our knowledge, no systematic review has been conducted to summarize these findings in East African countries. Therefore, the following questions emerged, what is the KAP of mothers in relation to EBF described in the literature and how are these domains being evaluated? KAP investigations lead to an understanding of what a particular mother knows, thinks, and does in relation to exclusive breastfeeding.

The purpose of this review was to examine the status of mothers’ KAP related to EBF in east Africa. In order to promote and support the practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in east Africa and to increase the number of mothers who want to achieve the better development of children, it is also important to inform the policymakers, with an intervention that could improve knowledge, attitude, and behaviors of women regarding exclusive breastfeeding.

Searching strategies

The current systematic review was reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) [ 23 ]. We searched published literature using the PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Embase, Science direct, and Cochrane library databases. The search was conducted using the following keywords: exclusive breastfeeding, knowledge, attitude, practice, and East Africa. The search terms were used separately and in combination using Boolean operators like “AND” and “OR”. Studies published from 1 January 2000 to 25 June 2019 were included in this study. The reference list of included studies was hand searched and screened.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria.

This systematic review was based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) study area: the studies exclusively done in any of the countries of East Africa (EA). EA being made by the following countries, including Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, Mozambique, Madagascar, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Comoros, Mauritius, Seychelles, Reunion, Mayotte, South Sudan, and Sudan were selected [ 24 ], 2) publication condition: articles published in peer-reviewed journals, 3) types of studies: any types of study designs reporting the impact of knowledge, or attitude towards EBF practice, 4) language: only English publications were considered, 5) study participants: mothers of any age, 6) types of outcome interests. The research focused on knowledge, attitude, and practice towards exclusive breastfeeding among mothers.

Exclusion criteria

The studies focused on health professionals and articles focused on mothers with their partners were excluded. Studies reported on breastfeeding alone, not exclusive breastfeeding were also excluded, and books, thesis, dissertation, case report conference, data unavailable studies, and articles were not accessed.

Selection of studies and data extraction

All researchers independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. The full text was then revised to confirm an eligibility criteria match. Using a predesigned data extraction form, all investigators independently extract the following data from each study: (1) study characteristics, including the name of the primary author, publication year, the country where the study was conducted, study design, sample size, aims, methods, and instrument, (2) study assessed mothers’ knowledge, attitude, and practice about EBF.

All investigators independently screened the studies according to the titles and abstracts. If the articles met the eligibility criteria, we would further read the full text to screen the study and any discrepancies between all investigators were resolved by discussion.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle Ottawa scale for cross-sectional studies quality assessment tool was adopted and used to assess the quality of each study [ 25 ]. The tool has three major sections. The first section graded from five stars focuses on the methodological quality of each study, the second section of the tool deals with the comparability of the study, and the last section deals with the outcomes and statistical analysis of each original study. All authors independently evaluated the quality of each original study using the tool, moreover; disagreements between all authors were resolved. Finally, no studies were excluded from the quality assessment and the result of quality assessment scores can found in Table 1 .

Data analysis

The pooled total percentage of each variable of interest was generated from included studies. The numerator percentage was retrieved from each question and calculated using the numbers of mothers who were the respondents divided by the total sample size of the studies from those questions were reported. The total percentage was only generated for variables conducted in more than two studies.

Study selection

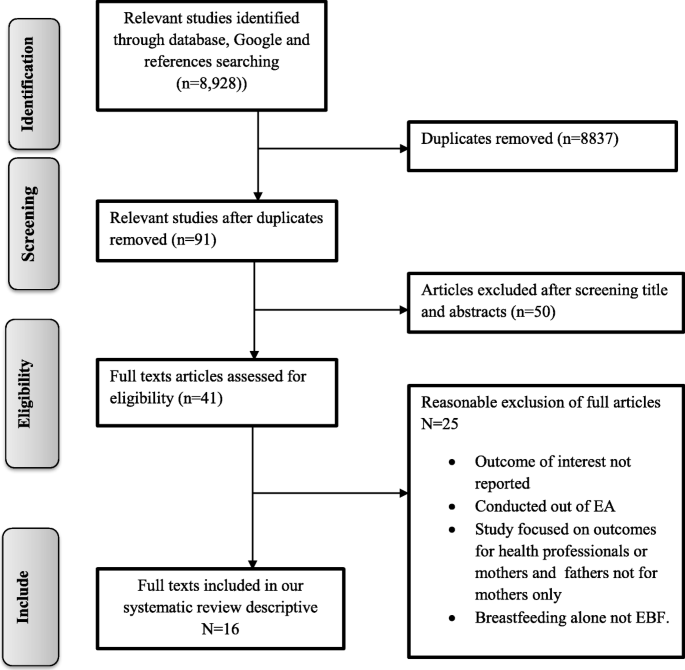

In the first step of our search strategy and terms, 8928 studies were retrieved, from which 91 were duplicates leaving 8837 papers (Fig. 1 ). The titles and abstracts were screened for relevance and a further 50 papers were eliminated. The full text of the remaining 41 relevant papers was assessed to make further exclusions; 25 were excluded because the participants were not mothers, the intervention examined in studies focused on outcomes of health professionals and also not related to mothers, or knowledge, or attitude about EBF were not reported.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection

Description of the included studies

Summary of the studies included in this review of East Africa countries published between 2001 and 2018 were shown in Table 1 . Of the studies conducted; seven were from Ethiopia [ 26 , 30 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ], three from Kenya [ 28 , 29 , 35 ], two from Uganda [ 31 , 32 ], one from Rwanda [ 27 ], two from Tanzania [ 34 , 41 ], and one from South Sudan [ 40 ]. The sample sizes ranged from 90 to 640 participants. Seven studies reported knowledge, attitude, and practice [ 26 , 27 , 29 , 33 , 37 , 38 , 39 ], seven studies reported knowledge and practice [ 31 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 40 , 41 ], and two studies reported knowledge and attitude [ 28 , 30 ]. However, there were no studies reported from the other east Africa countries due to lack of data. The majority of the studies assessed the knowledge of EBF through questionnaires [ 27 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 40 ] and/or interviews [ 26 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 41 ], and one study was focusing on group discussions [ 28 ]. The lowest and highest prevalence (26.4, 82.2%) of EBF was observed in the study conducted in Ethiopia [ 36 , 39 ]. Concerning the quality of the score, the lowest score of three was found in the study conducted in Uganda [ 32 ] while the highest was eight was a study conducted in Kenya [ 29 ].

Mothers’ knowledge about EBF

The mothers’ knowledge in aspects of EBF is presented in Table 2 ; there are 20 questions about knowledge of EBF, which mainly focused on the importance of EBF and breast milk, duration of feeding, early initiation, breastfed on-demand, colostrum, the right time to start the complimentary foods, definition, benefits to mothers and babies, the danger of bottle feeding, and general knowledge about exclusive breastfeeding. The percentage of knowledge ranges from 41.4 to 97.5% with a higher percentage indicating more knowledge.

There are two questions that showed the importance of EBF, including “the importance of breastfeeding”, and “breast milk alone is important for the baby in the first six months”, and the right answer percentage is 97.5 and 83.8% respectively. For the duration questions; “early initiation, breastfed on-demand, colostrum fed immediately, know about EBF and the right time to start complimentary food”, the right answer percentage is 49.2, 75.8, 41.4, 67.9 84.4, and 81.0%, respectively. In addition, “ever heard about EBF, EBF protects babies from illness, EBF protects mothers from pregnancy, breast milk alone is enough for an infant less than six months of life, and the danger of bottle-feeding”, the right answer percentage is 96.2, 55.1, 41.7, 60.5, 61.8% respectively. Furthermore, there are another seven questions on the range percentages from 52.2 to 96.2% (Table 2 ).

Mothers’ attitudes about EBF

As shown in Table 3 , there are 22 questions used to assess women’s attitude to breastfeeding, covering respondents’ attitude about early initiation, discarding the colostrum, starting complementary foods before six months are important, EBF is enough for a child for up to six months, prefer what to feed your baby for the first six months, formula feeding is more convenient than breastfeeding, EBF is beneficial to the child, breastfeeding increases mother infant-bonding, breastfed babies are healthier than fed babies, EBF is better than artificial feeding, etc.

There are three questions that showed the importance of EBF, which focused on “importance of early initiation, discarding the colostrum, and starting complementary foods before six months”, the right answer percentage 28.9, 47.9, and 72.1%, respectively. In addition, for “EBF is enough for a child up to six months, prefer to feed your baby for the first six months, breastfeeding increases mother infant-bonding, EBF is beneficial to the child, breastfed babies are healthier than fed babies, formula feeding is more convenient than breastfeeding, and EBF is better than artificial feeding”, the right answers percentage 47.6, 42.0, 48.6, 91.61, 74.1, 45.8, and 73.0%, respectively. In addition, 12 questions are the range percentages from 42 to 97.5%.

Mothers’ practices about EBF

As shown in Table 4 , there are five questions about practices EBF which focused on initiation, breast on-demand, exclusive breastfeeding only, colostrum, and prelacteal food. Most of the mothers (72.9%) had initiated breastfeeding within one hour after delivery. However, only 15.8% of mothers were breastfeeding on demand. Besides that, only 55.9% had exclusively breastfed their children for the first six months and the majority of mothers, 79.5%, had given colostrum. Furthermore, only 31.6% had given prelacteal food for their newborn babies.

Source of information about EBF

Table 5 shows the source of information about exclusive breastfeeding. The mothers indicated that they mainly acquired their breastfeeding knowledge from health institutions 67.8%, mass media13.1%, husband 2.6%, and friends 1.4%.

This study has synthesized from the findings of 15 studies that examined the mothers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices about exclusive breastfeeding in East Africa. Most of the best answers on knowledge range from 40.1 to 97.6% in mothers regarding exclusive breastfeeding. The mothers’ knowledge of EBF was generally fair, even though some notable gaps were recognized. According to the Food Agricultural and Organization (FAO) guidelines thresholds suggestive of nutrition intervention, a knowledge score of ≤70% is considered urgent for nutrition intervention. All mothers who scored > 70% in the knowledge test were considered to have a high level of knowledge and those scoring ≤70% were considered as having a low level of knowledge [ 42 ].

The results of this study indicate that mothers with a high level of knowledge about the importance of exclusive breastfeeding know that only breast milk is nutritionally important for the baby in the first six months, the right time to give breast milk to the child within one hour after birth. This result was similar to the previous studies conducted in Ghana [ 21 ] and Brazil [ 43 ]. In addition to gaps in mothers’ knowledge of EBF, the results of this study indicate that most mothers also had inadequate knowledge of duration of feeding, colostrum, breastfed on-demand, benefits to mothers and babies, the danger of bottle-feeding, compared to the studies conducted in Italy [ 44 ], China [ 20 ], and India [ 45 ]. Therefore, these gaps in maternal knowledge should be taken into consideration for future interventions designed by health workers, policymakers, and health educators who should make a conscious effort to explain the benefits of breast milk, breastfeed on-demand, and colostrum initiation immediately after birth. Furthermore, the danger of bottle-feeding should emphasise that it is unsafe for the child since it can cause childhood infections like vomiting, diarrhea diseases.

Our study also examined mothers’ attitudes about EBF in East Africa. Basically, positive maternal attitudes toward breastfeeding are associated with continuing to breastfeed longer and having a greater chance of successful breastfeeding. Besides, mothers with a positive attitude toward breastfeeding were likely to exclusively breastfeed their infants . According to the FAO guidelines thresholds suggestive of nutrition intervention, an attitude score of ≤70% is considered urgent for nutrition intervention. All mothers who scored > 70% in the attitude test were considered to have a positive attitude and those scoring ≤70% were considered to be less positive [ 42 ]. The results of this study indicate that few mothers had a positive attitude towards exclusive breastfeeding such as starting complementary foods after six months and belief that EBF is beneficial to the child and better than artificial feeding .

However, most mothers disagreed with the fact that giving breast milk for newborn colostrum immediately and within an hour is important , EBF is enough for a child up to six months, to feed their baby for the first six months, breastfeeding increases mother infant-bonding, breastfed babies are healthier than fed babies, formula feeding is more inconvenient than breastfeeding. The results of this study indicate that mothers had the lowest level of attitude about exclusive breastfeeding, and the findings were similar to the studies conducted in Vietnam [ 46 ], India [ 47 ], Mexico [ 48 ], China [ 20 ], Saudi Arabia [ 49 ]. The previous studies conducted in East Africa by Maonga et al. [ 16 ] and Arts, M et al. [ 50 ] reported that other cultural beliefs mentioned “baby boy” need solid foods immediately because they make them strong and healthy, and if a child is breastfed on breast milk alone for six months, the bones get weak. This barrier was probably the consequence of inadequate knowledge and awareness of ensuring that mothers should exclusively breastfeed during first six months of their babies’ lives, and indicates that future breastfeeding promotion programs should focus on improving this knowledge and attitude, and providing more support for mothers. Thus the fact that East Africa and non-government organizations have joined and established platforms to address the gaps and collectively finding the solutions for improving the exclusive breastfeeding and sustain its positive health impacts in particular at both, health facilities and community level and to work closely with the media as the main channel to mobilize the awareness. It is so important to change their attitude from negative to positive.

The findings of this study show the practices of mothers about exclusive breastfeeding. Accordingly, the studies conducted in East Africa reported factors affecting actualization of the WHO breastfeeding recommendations “poverty, livelihood and living conditions; early and single motherhood; poor social and professional support; commercial sex work, poor knowledge, myths and misconceptions; HIV and unintended pregnancies, the perception that mothers’ breast milk is insufficient for child’s growth, child being thirsty and the need to introduce herbal medicine for cultural reasons” [ 16 , 18 , 50 , 51 ].

The results of this survey indicated that most of the mothers have breastfed their children, but only 55.9% of mothers had exclusively breastfed their child for the first six months, even though most mothers have heard of EBF and consider it important for the health of the women and the baby. This study findings were higher compared with studies conducted in the developed countries like Brazil 19% [ 52 ], in China 6.2% [ 53 ], in Italy 33.3% [ 44 ]. The WHA global target is 50% [ 1 ] but it was lower compared to the EBF of 90% as recommended by the WHO [ 15 ]. The majority of mothers 79.5.0% had given colostrum, this finding was similar to a study conducted in Nepal where 83.3% of children received colostrum [ 54 ]. Most of the mothers, 72.9%, had initiated breastfeeding within one hour after delivery, this result was not matching the recommendations of WHO and this result was highest with secondary analysis of the WHO Global Survey, 57.6% of mothers initiating breastfeeding within one hour after birth [ 19 ]. Our study was lower than the prevalence of other studies conducted in China 93.6% [ 53 ] and in India 95% [ 55 ]. This value indicates that healthcare providers who care for mothers should increase their efforts to promote EBF and that there is a need for public policies which that ensure the living and working conditions of women are compatible with exclusive breastfeeding.

Good feeding practice is important for the health and nutritional status of children, which in turn has dire consequences for their mental and physical development and it is important for mothers as well. Early suckling motivates the release of prolactin, which supports the production of milk, and oxytocin, which is accountable for the ejection of milk. It also stimulates contraction of the uterus after childbirth and reduces postpartum hemorrhage [ 56 ].

According to the source of information about EBF, 67.8% of mothers reported that the main source of information about EBF was the health institutions and mass media (13.1%). This result was higher than the study conducted in India 42.5% of health workers [ 55 ], however, our result is not great so there is the need to motivate health professionals to do more education on exclusive breastfeeding. Previous studies demonstrated that motivation by healthcare workers was a stronger predictor to increase knowledge, or change attitudes, and practices favorable to breastfeeding and that for successful initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding; mothers need encouragement and support, not only from their relatives and communities but also from the health system [ 20 , 57 ].

Limitations of the study

This systematic review has several limitations, the first limitation of this study was only English articles were considered and there may be other studies published in other languages. Relevantly, almost all studies included in this review were cross-sectional in nature. As a result, the confounding variables might be affected by other confounding variables; moreover, the majority of the studies included in this study had a small sample size, therefore these factors could generalize reports. However, most of the studies were conducted in Ethiopia, in this country socio-economic is highest compared to others, meaning the generalizability of measures to other countries cannot be assumed. In addition to that, the numerator and denominator used in the included studies were only based on the sample size of the studies which is absolutely not representatives of the population from which those studies were conducted. Furthermore; this review represented only studies reported from six countries and therefore we could not generalize our findings across EA. The country may be underrepresented due to the limited number of studies included. Another limitation was that reliability and validity to assess the outcome of mothers’ EBF knowledge and attitude were not presented in all studies.

Exclusive breastfeeding among our sample is suboptimal, compared to the current WHO recommendations. In addition, there are relatively unfavorable levels of knowledge and a less positive attitude of EBF as compared to the FAO guidelines, in fact, the observed EBF practices across all included studies were statistically found to be 55.9%, which is absolutely below the FAO and WHO recommendations. The results of this study are critically important, that as they are addressing the gap in the EBF segment and sensitively show evidence for areas where urgent interventions are needed. Moreover, these results also inform policymakers of different countries in East Africa where they can respond and integrate EBF programs within their community health system. It also identifies the need for the workforce to encourage mothers to attend antenatal and postnatal care to improve EBF practice. It also shows that educational strategies are important to improve and correct mothers’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and sociocultural norms about EBF. We suggest that all levels of healthcare workers should be involved with EBF education. To promote well-baby visits, antenatal and early postpartum education, and also during home visits by community health workers, should improve maternal knowledge and attitudes toward breastfeeding practice.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

Exclusive Breastfeeding

World Health Organization

United Nation Children’s Fund

World Health Assembly

Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and meta-analysis

- East Africa

Food and Agriculture Organization

Knowledge Attitude

Knowledge Practice

WHO.WHA Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Breastfeeding Policy Brief 2014. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/globaltargets_breastfeeding_policybrief.pdf .

Hossain M, Islam A, Kamarul T, Hossain G. Exclusive breastfeeding practice during first six months of an infant's life in Bangladesh: a country based cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18:93.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

UNICEF. Breastfeeding: A Mother’s Gift, for Every Child .2018.UNICEF: United Nations Children’s Fund. https://www.unicef.org/publications/index_102824.html . Accessed 23 Jun 1019.

Idris SM, Tafang AGO, Elgorashi A. Factors influencing exclusive breastfeeding among mother with infant age 0-6 months. International Journal of Science and Research. 2015;4(8):28–33.

Google Scholar

Al-Binali AM. Breastfeeding knowledge, attitude, and practice among school teachers in Abha female educational district, southwestern Saudi Arabia. Int Breastfeed J. 2012;7:10.

Sinshaw Y, Ketema K, Tesfa M. Exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors among mothers in Debre Markos town and Gozamen district, east Gojjam zone, north West Ethiopia. Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences. 2015;3(5):174–9.

CAS Google Scholar

Holtzman O, Usherwood T. Australian general practitioners' knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards breastfeeding. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0191854.

Ogbo FA, Nguyen H, Naz S, Agho KE, Page A. The association between infant and young child feeding practices and diarrhoea in Tanzanian children. Trop Med Health. 2018;46:2.

Victora CG, Horta BL, Mola CL, Quevedo L, Pinheiro RT, Gigante DP, et al. Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e199–205.

Saadehl R, Benbouzid D. Breastfeeding and child-spacing: importance of information collection for public health policy. WHO. 1990;68(5):625–63.

Hawley NL, Rosen RK, Strait AE, Raffucci G, Holmdahl I, Freeman JR, et al. Mothers' attitudes and beliefs about infant feeding highlight barriers to exclusive breastfeeding in American Samoa. Women Birth. 2015;28:e80–6.

PubMed Google Scholar

Skouteris H, Nagle C, Fowler M, Kent B, Sahota P, Morris H. Interventions designed to promote exclusive breastfeeding in high-income countries: a systematic review. Breastfeed Med. 2014;9(3):113–27.

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, França GVA, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387:475–90.

Issaka AI, Agho KE, Renzaho AMN. Prevalence of key breastfeeding indicators in 29 sub-Saharan African countries: a meta-analysis of demographic and health surveys (2010-2015). BMJ Open 2017, 7:e014145.

Jahanpour O, Msuya SE, Todd J, Stray-Pedersen B, Mgongo M. Increasing trend of exclusive breastfeeding over 12 years period (2002-2014) among women in Moshi. Tanzania BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:471.

Maonga AR, Mahande MJ, Damian JD, Msuya SE. Factors affecting exclusive breastfeeding among women in Muheza district Tanga northeastern Tanzania: a mixed method community based study. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:77–87.

Setegn T, Belachew T, Gerbaba M, Deribe K, Deribew A, Biadgilign S. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practice among mothers in Goba. South East Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study Int Breastfeed J. 2012;7:17.

Mututho LN, Kiboi WK, Mucheru PK. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in Kenya: a systematic review. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health. 2017;4(12):4358–62.

Takahashi K, Ganchimeg T, Ota E, Vogel JP, Souza JP, Laopaiboon M, et al. Prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding and determinants of delayed initiation of breastfeeding: secondary analysis of the WHO global survey. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44868.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hamze L, Mao J, Reifsnider E. Knowledge and attitudes towards breastfeeding practices: a cross-sectional survey of postnatal mothers in China. Midwifery. 2019;74:68–75.

Mogre V, Dery M, Gaa PK. Knowledge, attitudes, and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practice among Ghanaian rural lactating mothers. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:12.

Zhang Z, Zhu Y, Zhang L, Wan H. What factors influence exclusive breastfeeding based on the theory of planned behaviour. Midwifery. 2018;62:177–82.

Yang SF, Salamonson Y, Burns E, Schmied V. Breastfeeding knowledge and attitudes of health professional students: a systematic review. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13:8.

East African Countries 2020 - World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/Countries/East-african-countries . Accessed 10 Apr 2020.

Newcastle Ottawa scale for cross-sectional studies. 2019. https://wellcomeopenresearch.s3.amazonaws.com › supplementary. Accessed 24 Jul 2019.

Wolde T, Diriba G, Wakjira A, Misganu G, Negesse G, Debela H, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among lactating mothers in Bedelle town, southwestern Ethiopia: descriptive cross-sectional study. ResearchGate. 2014;6(11):91–7.

Jino GB, Munyanshongore C, Birungi F. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of exclusive breastfeeding of infants aged 0-6 months by urban refugee women in Kigal. Rwanda Med J. 2013;70:7–10.

Girard AW, Cherobon A, MbuguaS MEK, Amin A, Sellen DW. Food insecurity is associated with attitudes towards exclusive breastfeeding among women in urban Kenya. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8:199–214.

Mohamed MJ, Ochola S, Owino VO. Comparison of knowledge, attitudes, and practices on exclusive breastfeeding between primiparous and multiparous mothers attending Wajir District hospital, Wajir County. Kenya: a cross-sectional analytical study Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13:11.

Alamirew MW, Bayu NH, Tebeje NB, Kassa SF. Knowledge and attitude towards exclusive breastfeeding among mothers attending antenatal and immunization clinic at Dabat health center, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional institution based study. Nurs Res Pract. 2017;9.

Adrawa AP, Opi D, Candia E, Vukoni E, Kimera I, Sule I, et al. Assessment of knowledge and practices of breastfeeding amongst the breastfeeding mothers in Adjumani. West Nile East African Medical Journal. 2016;93(11):576–81.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Petit AI. Perception and knowledge on exclusive breastfeeding among women attending antenatal and postnatal clinics: a study from Mbarara hospital, Uganda, august 2008. Tanzania Medical Students’ Association. 2010;16:1.

Asfaw MM, Argaw MD, Kefene ZK. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices in Debre Berhan district, Central Ethiopia: a cross-sectional community-based study. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10:23.

Nkala TE, Msuya SE. Prevalence and predictors of exclusive breastfeeding among women in Kigoma region. Western Tanzania: a community based cross-sectional study Int Breastfeed J. 2011;6:17.

Gewa CA, Chepkemboi J. Maternal knowledge, outcome expectancies, and normative beliefs as determinants of cessation of exclusive breastfeeding: a cross-sectional study in rural Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:243.

Bayissa ZB, Gelaw BK, Geletaw A, Abdella A. Chinasho B, Alemayehu a, et al. knowledge and practice of mothers towards exclusive breastfeeding and its associated factors in ambo Woreda west Shoa zone Oromia region, Ethiopia. European Journal of Pharmaceutical and Medical Research. 2015;2(2):1–13.

Wana AD. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice on exclusive breastfeeding of child bearing mothers in Boditi town, Southern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare 2017, 7:1.

Ballo TH, Wodajo MZ, Malar JS. Knowledge, attitude, and practices of exclusive breastfeeding: a facility-based study in Addis Ababa. International Journal of Therapeutic Applications. 2016;33:72–82.

Tadele N, Habta F, Akmel D, Deges E. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards exclusive breastfeeding among lactating mothers in Mizan Aman town. Southwestern Ethiopia: Descriptive cross-sectional study Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:3.

Warillea EB, Onyango FE, Osano B. Knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among women with children aged between 9 and 12 months in Al-Sabah children hospital, juba. South Sudan South Sudan Medical Journal. 2017;10:1.

Shirima R, Gebre-Medhin M, Greiner T. Information and socioeconomic factors associated with early breastfeeding practices in rural and urban Morogoro, Tanzania. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90:936–42.

Macías YF, Glasauer P. Guidelines for assessing nutrition related knowledge, attitudes, and practices: food and agricultural organisation of the United Nations; Rome; 2014.

Vieira TO, Vieira GO, Giugliani ERJ, Mendes CMC, Martins CC, Silva LR. Determinants of breastfeeding initiation within the first hour of life in a Brazilian population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:760.

Cascone D, Tomassoni D, Napolitano F, Giuseppe GD. Evaluation of knowledge, attitudes, and practices about exclusive breastfeeding among women in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2118.

PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bashir A, Mansoor S, Naikoo MY. Knowledge, attitude, and practices of postnatal mothers regarding breastfeeding: a cross-sectional study. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health. 2018;7(9):725.

Kim TD, Chapman RS. knowledge attitude and practice about exclusive breastfeeding among women in chililab in Chilinh town Haiduong province Vietnam. Journal of Health Research 2013, 27:1.

Singh J, BhardwarV, Kumra A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards exclusive breastfeeding among lactating mothers: Descriptive cross-sectional study . International Journal of Medical and Dental Sciences 2018, 7(1):1586.

Swigart TM. BonvecchioA, Theodore FL, ZamudioHaas S, Villanueva-Borbolla MA, thrasher JF. Breastfeeding practices, beliefs, and social norms in low-resource communities in Mexico: insights for how to improve future promotion strategies. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180185.

Ayed AAN. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding exclusive breastfeeding among mothers attending primary health care centers in Abha city. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health. 2014;3(11):1355–63.

Arts M, Geelhoed D, Schacht C, Prosser W, Alons C, Pedro A. Knowledge, beliefs, and practices regarding exclusive breastfeeding of infants younger than 6 months in Mozambique: a qualitative study. J Hum Lact. 2011;27(1):25–32.

Kimani-Murage EW, Wekesah F, Wanjohi M, Kyobutungi C, Ezeh AC, Musoke RN, et al. Factors affecting actualisation of the WHO breastfeeding recommendations in urban poor settings in Kenya. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11:314–32.

Monteiro JCS, Dias FA, Stefanello J, Reis MCG, Nakano AMS, Gomes-Sponholz FA. Breastfeeding among Brazilian adolescents: practice and needs. Midwifery. 2014;30:359–63.

Ouyang YQ, Su M, Redding SR. A survey on difficulties and desires of breastfeeding women in Wuhan, China. Midwifery. 2016;37:19–24.

Yadav DK, Gupta N, Shrestha N. Infant and young child feeding practices among mothers in rural areas of Mahottari district of Nepal. J-GMC-N. 2013;6(2):29–31.

Col Jain S, Col Thapar RK, Brig Gupta R.K. Complete coverage and covering completely: breastfeeding and complementary feeding: knowledge, attitude, and practices of mothers. Med J Armed Forces India 2018, 74:28–32.

HailemariamTW, Adeba E, Sufa A. Predictors of early breastfeeding initiation among mothers of children under 24 months of age in rural part of West Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2015, 15:1076.

Hanafi MI, Shalaby SAH, Falatah N, El-Ammari H. Impact of health education on knowledge of, attitude to and practice of breastfeeding among women attending primary health care centres in Almadinah Almunawwarah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: controlled pre-post study. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2014;9(3):187–93.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the authors who conducted and published the original studies.

Author details

DCJP 1 is a master student in the Department of Maternal and Child Health, Xiangya School of Public health, Central South University, Changsha, China.

KA 2 is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Epidemiology and health statistics, Xiangya School of Public health, Central South University, Changsha, China, and a graduate from the School of Postgraduate Studies, Adventist University of Africa, Nairobi, Kenya.

JA 2 is a master student in the Department of Epidemiology and health statistics, Xiangya School of Public health, Central South University, Changsha, China.

JL * is a Professor and Dean of the Maternal and Child Health Department at the Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University, Changsha, China.

National Natural Foundation of China (grant #: 81172680).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Maternal and Child Health, Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University, Changsha, 410078, China

Jean Prince Claude Dukuzumuremyi & Jiayou Luo

Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University, Changsha, 410078, China

Kwabena Acheampong & Julius Abesig

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

DCJP: Searched, analyzed, interpreted the data used in the manuscript, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. KA and JA: Searched, critically analyzed the manuscript for scientific logic and reasoning. JL: Reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jiayou Luo .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Dukuzumuremyi, J.P.C., Acheampong, K., Abesig, J. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in East Africa: a systematic review. Int Breastfeed J 15 , 70 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00313-9

Download citation

Received : 01 November 2019

Accepted : 29 July 2020

Published : 14 August 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00313-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Exclusive breastfeeding

International Breastfeeding Journal

ISSN: 1746-4358

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Bibliography

- More Referencing guides Blog Automated transliteration Relevant bibliographies by topics

- Automated transliteration

- Relevant bibliographies by topics

- Referencing guides

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Predicting breastfeeding duration using the LATCH breastfeeding assessment tool

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing, Wichita State University, Box 41, Wichita, Kansas 67260-0041, USA.

- PMID: 11847847

- DOI: 10.1177/089033440101700105

The authors tested the validity of the LATCH breastfeeding assessment tool, controlling for intervening variables in 133 dyads. LATCH scores, mother's evaluation of an index feed, and intended duration of breastfeeding were assessed postpartum and followed 6 weeks. Women breastfeeding at 6 weeks postpartum had higher LATCH scores (mean +/- SD = 9.3 +/- 0.9) than those who weaned (mean +/- SD = 8.7 +/- 1.0), due to only one measure, breast/nipple comfort. Women who weaned before 6 weeks reported lower breast/nipple comfort (1.5 +/- 0.5) than those who were still breastfeeding at 6 weeks (1.7 +/- 0.5, P < .05). Total LATCH scores accounted for 7.3% of variance in breastfeeding duration. Total LATCH scores positively correlated with duration of breastfeeding (n = 128; r = .26, P = .003) and to mothers' scores (n = 132; r = .58, P = .001). Correlations among LATCH measures ranged from .02 to .51. The LATCH tool is a useful identifies the need for follow-up with breastfeeding mothers at risk for early weaning because of sore nipples.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Caring for new mothers: diagnosis, management and treatment of nipple dermatitis in breastfeeding mothers. Heller MM, Fullerton-Stone H, Murase JE. Heller MM, et al. Int J Dermatol. 2012 Oct;51(10):1149-61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05445.x. Int J Dermatol. 2012. PMID: 22994661 Review.

- Latching-on and suckling of the healthy term neonate: breastfeeding assessment. Cadwell K. Cadwell K. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007 Nov-Dec;52(6):638-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.08.004. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007. PMID: 17984002 Review.

- Ankyloglossia in breastfeeding infants: the effect of frenotomy on maternal nipple pain and latch. Srinivasan A, Dobrich C, Mitnick H, Feldman P. Srinivasan A, et al. Breastfeed Med. 2006 Winter;1(4):216-24. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2006.1.216. Breastfeed Med. 2006. PMID: 17661602

- The LATCH scoring system and prediction of breastfeeding duration. Kumar SP, Mooney R, Wieser LJ, Havstad S. Kumar SP, et al. J Hum Lact. 2006 Nov;22(4):391-7. doi: 10.1177/0890334406293161. J Hum Lact. 2006. PMID: 17062784

- The relationship between positioning, the breastfeeding dynamic, the latching process and pain in breastfeeding mothers with sore nipples. Blair A, Cadwell K, Turner-Maffei C, Brimdyr K. Blair A, et al. Breastfeed Rev. 2003 Jul;11(2):5-10. Breastfeed Rev. 2003. PMID: 14768311

- Potential role of β-carotene-modulated autophagy in puerperal breast inflammation (Review). Tinia Hasianna S, Gunadi JW, Rohmawaty E, Lesmana R. Tinia Hasianna S, et al. Biomed Rep. 2022 Jul 22;17(3):75. doi: 10.3892/br.2022.1558. eCollection 2022 Sep. Biomed Rep. 2022. PMID: 35950095 Free PMC article. Review.

- Effect of nipple shield use on milk removal: a mechanistic study. Coentro VS, Perrella SL, Lai CT, Rea A, Murray K, Geddes DT. Coentro VS, et al. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Sep 7;20(1):516. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03191-5. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020. PMID: 32894074 Free PMC article.

- The effect of maternity practices on exclusive breastfeeding rates in U.S. hospitals. Patterson JA, Keuler NS, Olson BH. Patterson JA, et al. Matern Child Nutr. 2019 Jan;15(1):e12670. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12670. Epub 2018 Sep 4. Matern Child Nutr. 2019. PMID: 30182474 Free PMC article.

- Effect of frenotomy on breastfeeding variables in infants with ankyloglossia (tongue-tie): a prospective before and after cohort study. Muldoon K, Gallagher L, McGuinness D, Smith V. Muldoon K, et al. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017 Nov 13;17(1):373. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1561-8. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017. PMID: 29132414 Free PMC article.

- Maternal, Infant Characteristics, Breastfeeding Techniques, and Initiation: Structural Equation Modeling Approaches. Lau Y, Htun TP, Lim PI, Ho-Lim S, Klainin-Yobas P. Lau Y, et al. PLoS One. 2015 Nov 13;10(11):e0142861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142861. eCollection 2015. PLoS One. 2015. PMID: 26566028 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- MedlinePlus Consumer Health Information

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Women Exposed to ‘Forever Chemicals’ May Risk Shorter Breastfeeding Duration – The Guardian

Read article - Megan Romano, an associate professor of epidemiology, is featured in an article about her study into the risks to breastfeeding duration associated with exposure to PFAS. "For all women who are exposed, there's a little bit of a decrease in the amount of time they breastfeed beyond delivery," Romano said.

Share this:

Search news, upcoming events.

- PhD Thesis Presentation - Rachel Berg-Murante July 9, 2024

- Thesis Defense (Asmaa Mohamed) July 17, 2024

- Graduate Seminar (Chrystal M. Paulos) July 17, 2024

- Thesis Defense (Shawn Musial) July 18, 2024

- Graduate Seminar (Justin Milner) July 18, 2024

- Psychiatry Grand Rounds July 19, 2024

- Psychiatry Grand Rounds August 19, 2024

- Psychiatry Grand Rounds September 19, 2024

Geisel in the News

A user’s guide to midlife – the new york times, fda advisors voted against mdm therapy—researchers are still fighting for it – bbc, mental health crisis there’s an app for that – plugged in, county cases may be link to als, algal blooms – observer today, check us out on instagram - @geiselmed_dartmouth.

This page may link to PDF files. Use this link to download Adobe Reader if needed.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Arch Public Health

- PMC10102688

Prevalence and predictors of delayed initiation of breastfeeding among postnatal women at a tertiary hospital in Eastern Uganda: a cross-sectional study

Loyce kusasira.

1 Department of Nursing, Busitema University Faculty of Health Sciences, P.O. BOX 236, Mbale, Tororo, Uganda

David Mukunya

2 Department of Community and Public Health, Busitema University Faculty of Health Sciences, P.O. BOX 236, Mbale, Tororo, Uganda

4 Sanyu Africa Research Institute, P.O BOX 2190, Mbale, Uganda

Samuel Obakiro

3 Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Busitema University Faculty of Health Sciences, P.O. BOX 236, Mbale, Tororo, Uganda

Kiyimba Kenedy

Nekaka rebecca, lydia ssenyonga, mbwali immaculate, agnes napyo.

5 Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, Uganda Martyrs University, P.O. Box 5498, Kampala, Uganda

Associated Data

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The rates for the delayed initiation of breastfeeding in Uganda remain unacceptably high between 30% and 80%. The reasons for this are not well understood. We aimed to determine the prevalence and predictors for the delayed initiation of breastfeeding in Eastern Uganda.

This study employed a cross-sectional study design. A total of 404 mother-infant pairs were enrolled onto the study between July and November, 2020 at Mbale regional referral hospital (MRRH). They were interviewed on socio-demographic related, infant-related, labour and delivery characteristics using a structured questionnaire. We estimated adjusted odds ratios using multivariable logistic regression models. All variables with p < 0.25 at the bivariate level were included in the initial model at the multivariate analysis. All variables with p < 0.1 and those of biological or epidemiologic plausibility (from previous studies) were included in the second model. The variables with odds ratios greater than 1 were considered as risk factors; otherwise they were protective against the delayed initiation of breastfeeding.

The rate of delayed initiation of breastfeeding was 70% (n = 283/404, 95% CI: 65.3 – 74.4%). The factors that were associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding were maternal charateristics including: being single (AOR = 0.37; 95%CI: 0.19–0.74), receiving antenatal care for less than 3 times (AOR = 1.85, 95%CI: 1.07–3.19) undergoing a caesarean section (AOR = 2.07; 95%CI: 1.3–3.19) and having a difficult labour (AOR = 2.05; 95%CI: 1.25–3.35). Infant characteristics included: having a health issue at birth (AOR = 9.8; 95%CI: 2.94–32.98).

Conclusions

The proportion of infants that do not achieve early initiation of breastfeeding in this setting remains high. Women at high risk of delaying the initiation of breastfeeding include those who: deliver by caesarean section, do not receive antenatal care and have labour difficulties. Infants at risk of not achieving early initiation of breastfeeding include those that have a health issue at birth. We recommend increased support for women who undergo caesarean section in the early initiation of breastfeeding. Breastfeeding support can be initiated in the recovery room after caesarean delivery or in the operating theatre. The importance of antenatal care attendance should be emphasized during health education classes. Infants with any form of health issue at birth should particularly be given attention to ensure breastfeeding is initiated early.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13690-023-01079-2.

The Uganda national policy guidelines on infant and young feeding recommend early initiation of breastfeeding (EIBF) within 1 h of birth, exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and there after continued breastfeeding for 2 years and beyond while introducing nutritionally adequate and age appropriate complementary foods [ 1 ]. Colostrum, the yellowish sticky breast milk produced at the end of pregnancy and first days after birth is the perfect food for the new born and this can be tapped through EIBF [ 2 ]. Colostrum is a rich source of nutrients, contains protective factors with anti-infective action, immunoglobulin, cytokines, complement-system components, leukocytes, oligosaccharides, nucleotides, lipids, and hormones that interact with each other and with the mucous membranes of the digestive and upper respiratory tracts of infants, providing passive immunity as well as stimulation for the development and maturation of the infant’s immune system [ 3 ]. The antimicrobial factors present in colostrum and milk have some common characteristics, such as resistance to degradation by digestive enzymes, protection of the mucosal surfaces and elimination of bacteria without initiating inflammatory reactions [ 3 ]. Therefore infants who miss out on EIBF, will miss out on the colostrum and this puts them at risk of opportunistic infections like diarrhea as well as hospitalization [ 4 , 5 ].

In some African and Asian settings, delayed initiation of breastfeeding has been associated with maternal-related characteristics which include: maternal education, mother being overweight, antenatal care attendance, maternal HIV infection, having a caesarean delivery and delivering out of a hospital setting. [ 6 – 11 ]. Available evidence has demonstrated that infants who start breastfeeding within 1 h of birth will most likely exclusively breastfeed [ 5 , 12 ].

The Ugandan government through the ministry of health has put up initiatives to promote EIBF like provision of free antenatal care at public health facilities and health education on infant feeding during antenatal visits [ 1 ]. Frequent antenatal care promotes frequent interface with the healthcare system coupled with continuous health education which inevitably equips the mother with the required knowledge on the importance of EIBF and this definitely translates into practice. Despite these initiatives, the practice of EIBF in Uganda is divergent from the ideal practice that is recommended in the policy guidelines on infant and young child feeding [ 1 , 12 ]. The rates of EIBF vary across and within countries [ 7 , 8 , 12 – 14 ] and Uganda is no exception [ 12 , 14 – 16 ]. The reasons behind this discrepancy are not fully explored or understood and vary from context to context. There is also paucity of published evidence on this subject in Mbale city in Eastern Uganda. Given this background, it was vital for us to conduct this study to determine the prevalence and predictors for delayed initiation of breastfeeding in Eastern Uganda. The findings from this study will help in identifying groups of women and infants that are at risk of delaying the initiation to breastfeeding for their infants. These groups can then be a target for interventions of appropriate infant feeding counselling and support.

Study design and setting

This study employed a cross-sectional study design. Mother-infant pairs were enrolled onto the study between July and November, 2020 at Mbale Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH), found in Mbale city, Eastern Uganda. MRRH is a general and teaching hospital for several medical and nursing institutions. It has a 400-bed capacity and serves over ten neighbouring districts in Mbale sub-region as a referral hospital. These include Kibuku, Kween, Bududa, Busia, Kapchorwa, Budaka, Butaleja, Pallisa, Manafwa, Namisindwa, Butebo, Sironko, Bukwo, Bulambuli and Tororo. However, the hospital also receives some patients from as far as Teso and Karamoja sub-regions. MRRH offers a wide range of health care services and these include: surgery, psychiatry, paediatric care, ear-nose and throat, outpatient, eye care, laboratory and dental care. This clinic also hosts special clinics such as gynaecology and obstetrics which include antenatal, maternity, postnatal and infant / young child care services. All these services are at no cost to the patients. In the Ugandan health care setting, pregnant women are free to seek antenatal care, labour and delivery services at any public health facility of their choice. However, during routine antenatal care classes at public health facilities, these women are advised to seek these services at health facilities that are nearest to where they reside. When the woman goes into labour, she reports to a public health facility and is admitted at the maternity ward. After delivery in the labour suite, women and their infants are then transferred to the postnatal ward where they both are monitored continuously for any complications that could arise. While admitted in the postnatal ward, women have to move to the young child clinic to take their infants for immunization. It is also possible that women-infant pairs registered and delivered from other health facilities other than MRRH are referred to the postnatal clinic for observation and to the young child clinic for immunization or child care. This study was conducted at the postnatal and young child clinics to obtain information about the women and their infants.

Participants and procedures

We consecutively enrolled onto the study, mother-infant pairs who were receiving postnatal care and those attending the young child clinic at MRRH. We recruited women with infants who were aged 0–6 days. We excluded women with infants aged 7 days or more for the purpose of mitigating recall bias. After consenting, women were interviewed on socio-demographic-related, infant-related characteristics as well as issues surrounding their pregnancy, labour and delivery. The information was collected using questionnaires through face-to-face interviews by trained research assistants who were fluent in the local language. The questionnaires used during the interview process were translated from English to the local language. The data collection tool was pretested to remove any irrelevant questions and avoid misinterpretation. The research assistants were qualified midwives who had experience in conducting research and providing postnatal care as well as immunization. These research assistants were not employees of MRRH to overcome social desirability. While collecting data, research assistants had to implement COVID-19 preventive measures like use of face masks, wearing of plastic aprons, hand washing with soap and water. A total of 404 mother-infant pairs were included in the final analysis, Fig. 1 .

Study flow chart

The sample size used in this study was determined using the Cochran formula stated as N= [Z 2 PQ]/d 2 [ 17 ]. Where: N is the sample size, the Z- score at a 95% confidence level is 1.96. P, which is the prevalence of EIBF in Uganda, stands at 65% [ 16 ]. Q is (1-p). d is the acceptable margin of error which is 5% or 0.05. We assumed a non-response rate of 10%. The minimum sample size required for this study was 389, we however included 404 postnatal women and their infants.

The outcome variable in our study was delayed initiation of breastfeeding defined as putting the infant on the breast to suckle beyond one hour after birth [ 1 ]. The exposures included in this study were maternal socio-demographic characteristics, pregnancy-, labour- and delivery- related as well as infant-related characteristics. Socio-demographic characteristics included maternal age which was recorded as the completed number of years for each individual; marital status was categorised and labelled as “married” if the women reported to be cohabiting or married. If she was divorced, separated or living alone, she was categorised as “single”. Religion was categorised as either “Christian” or “Moslem”. All those women that were formally or self-employed were categorised and labelled as “employed” and the rest as “unemployed”. Any residence that was estimated to be more than 10 km from Mbale municipality was categorised and labelled as “rural” or else “urban”. Women who had attended 3 or more antenatal visits were categorised and labelled as ‘≥ 3’ or otherwise they were labelled as ‘<3’. Women whose labour started between 06.00 and 18.59 h were categorised as “day-time onset of labour” and else “night-time onset of labour”. Women who delivered in any type of health care setting were all categorised as “hospital delivery” and otherwise as “non-hospital delivery”. Women who had reported to have had a lot of bleeding after delivery, prolonged labour, an episiotomy, high blood pressure, retained placenta, perineal tears, cervix not opening, breech presentation and draining liquor were all categorised and labelled as “had labour difficulty” or else “none”. Women who delivered their infants between 06.00 and 18.59 h were categorised and labelled as having delivered in the “day-time” and else “night-time”. An infant was categorised to have “had a health issue at birth” if the mother reported the infant to have weighed > 2.5 Kg, had difficulty in breathing, fever or diarrhoea. We, however, did not measure the body temperature of the infants due to the restrictive measures undertaken in MRRH for the prevention of SARS-CoV2. The age of the infants was recorded as completed number of days the infant had lived after birth.

Data analysis and management

Data were entered into excel software by two independent entrants. The two databases were then merged to check for any inconsistencies data entry. The data was then exported for analysis into Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, U.S.A.). Continuous data, if normally distributed, was summarised into means and standard deviations and if skewed, was summarised into medians with their corresponding interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were summarised into frequencies and percentages. The proportion of women who delayed to initiate breastfeeding was estimated and its confidence limits calculated using the exact method. We used multivariable generalized linear model regression analysis with a logit link to estimate the adjusted odds ratios of the independent variables on delayed initiation of breastfeeding while controlling for confounding. All variables with p < 0.25 at the bivariate level were included in the initial model at the multivariate analysis. All variables with p < 0.1 and those of biological or epidemiologic plausibility like age were included in the second model. We relied on the likelihood-ratio test to check the significant difference between the initial and the second model. There was no difference between the two models so then we adapted the second model. We checked for confounding by calculating the percentage change in each effect measure by removing or introducing one variable at a time into the second model. If a variable caused more than 10% change in any effect measure, then it was considered a confounder. We used the visual inspection factor to check for collinearity among all the variables that were included in the initial model. There was no collinearity. The pseudo R2 was 0.1146.

Sociodemographic-related characteristics

The median age of women attending the postnatal clinic at MRRH was 24 years (IQR 20, 30). The majority of these women were married (87.1%, n = 221/404), Christian (66.8%), unemployed (75.5%) and lived in a rural residence (71.5%). Only 10% of the women had received a tertiary education. Most of the women (70%) had 3 or more antenatal visits while they were pregnant. About forty per cent (n = 156/404) had a difficult labour. More than half of the women delivered by caesarean Sect. (57.2%) and in a hospital setting (98.3%). Many of the infants born to these women had no health issue at birth (84.9%). Approximately fifty per cent of the infants born to these women were male (n = 206/404) and their mean weight was at birth 3.21 Kg (SD 0.62). The median age of these infants was 1 day (IQR 1,2). (Table 1 ).

Characteristics of mothers and their infants

| Initiation of breastfeeding | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Delayed N = 283 (70) N(%) | Early N = 121 (30) N(%) | Total (N) N = 404 | P-value |

| 15–20 | 55(19.4) | 26(21.5) | 81 (20.0) | 0.766 |

| 20–29 | 154(54.4) | 67(54.4) | 221 (54.7) | |

| 30–47 | 74(26.2) | 28(23.1) | 102(25.3) | 0.599 |

| Married | 253(89.4) | 99(81.8) | 352(87.1) | |

| Single | 30 (10.6) | 22(18.2) | 52(12.9) | 0.039* |

| Christian | 195(68.9) | 75(62.0) | 270(66.8) | |

| Moslem | 88(31.1) | 46(38.0 | 134(33.2) | 0.177* |

| Primary | 134(47.3) | 48(39.7) | 182(45.0) | |

| Secondary | 121(42.8) | 61(50.4) | 182(45.0) | 0.138* |

| Tertiary | 28(9.9) | 12(9.9) | 40(10.0) | 0.64 |

| Not employed | 219(77.4) | 86(71.1) | 305(75.5) | |

| Employed | 64(22.6) | 35(28.9) | 99(24.5) | 0.178* |

| Urban | 72(25.4) | 43(35.5) | 115(28.5) | |

| Rural | 211(74.6) | 78(64.5) | 289(71.5) | 0.04* |

| ≥3 | 191(67.5) | 94(77.7) | 285(70.5) | |

| <3 | 92(32.5) | 27(22.3) | 119(29.5) | 0.041* |

| Day-time | 126(44.5) | 59(48.8) | 185(45.8) | |

| Night-time | 130(45.9) | 51(42.2) | 181(44.8) | 0.439 |

| No pains | 27(9.6) | 11(9.0) | 38(9.4) | 0.722 |

| Husband | 58(20.5) | 23(19.0) | 81(20.1) | |

| Other | 225(79.5) | 98(81.0) | 323(79.9) | 0.733 |

| None | 161(56.9) | 87(71.9) | 248(61.4) | |

| Had labour difficulty | 122(43.1) | 34(28.1) | 156(38.6) | 0.005* |

| Normal delivery | 105(37.1) | 68(56.2) | 173(42.8) | |

| Caesarean section | 178(62.9) | 53(43.8) | 231(57.2) | 0.000* |

| Day time | 162(57.2) | 62(51.2) | 224(55.5) | |

| Night time | 121(42.8) | 59(48.8) | 180(44.5) | 0.267 |

| Hospital | 277(97.9) | 120(99.2) | 397(98.3) | |

| Non-hospital | 6(2.1) | 1(0.8) | 7(1.7) | 0.379 |

| Male | 146(51.6) | 60(49.6) | 206(51.0) | |

| Female | 137(48.4) | 61(50.4) | 198(49.0) | 0.712 |

| Less than 2.5 kg | 29(10.3) | 5(4.1) | 34(8.4) | 0.049* |

| 2.5 to 4.5 kg | 248(87.6) | 114(94.2) | 362(89.6) | |

| Greater than 4.5 kg | 6(2.1) | 2(1.7) | 8(2.0) | 0.697 |

| Less than 3 days | 205(72.4) | 104(85.9) | 309(76.5) | |

| Greater or equal to three days | 78(27.6) | 17(14.1) | 95(23.5) | 0.04* |

| 1 | 102(36.0) | 46(36.0) | 148(36.6) | |

| 2 | 59(20.9) | 24(19.8) | 83(20.5) | 0.731 |

| 3 | 122(43.1) | 51(42.2) | 173(42.9) | 0.755 |

| No | 225(79.5) | 118(97.5) | 343(84.9) | |

| Yes | 58(20.5) | 3(2.5) | 61(15.1) | < 0.001* |

*Variables that were included in the initial multivariable model during multivariable analysis.

Prevalence of delayed initiation of breastfeeding

In our study, 70% (n = 283/404, 95% CI: 65.3 – 74.4%) of the postnatal women did not breastfeed their infants within one hour after birth (Table 1 ). We had a response rate of 100%. We achieved this by checking all questionnaires for completeness immediately after each interview prior to the participant leaving.

Predictors for delayed initiation of breastfeeding

Women who were single were less likely to delay the initiation of breastfeeding (AOR = 0.37; 95%CI: 0.19–0.74) compared to those who are married. Women who had received antenatal care less than 3 times were more likely to delay the initiation of breastfeeding (AOR = 1.85, 95%CI: 1.07–3.19) compared to those that had received antenatal care 3 or more times. Women who underwent a caesarean delivery were more likely to delay the initiation of breastfeeding (AOR = 2.07; 95%CI: 1.30–3.19) compared to women who had a spontaneous vaginal delivery. Women who had a difficult labour were more likely to delay the initiation of breastfeeding (AOR = 2.05; 95%CI: 1.25–3.35) compared to those that did not have any difficulty during labour. Infants that had a health issue at birth were less likely to start breastfeeding within 1 h after birth (AOR = 9.80; 95%CI: 2.94–32.98) when compared with those that did not have a health problem (Table 2 ).

Factors influencing early initiation of breastfeeding

| Variable | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–20 | 0.92 (0.53–1.59) | 0.84 (0.45–1.57) | ||

| 20–29 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 30–47 | 1.15 (0.68–1.94) | 1.07 (0.61–1.87) | ||

| Married | 1 | 1 | ||

| Single | 0.53 (0.29–0.97) | 0.37 (0.19–0.74)* | ||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 10.14 (3.11–33.05) | 9.80 (2.94–32.98)* | ||

| ≥3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| <3 | 1.68 (1.02–2.75) | 1.85 (1.07–3.19)* | ||

| Normal delivery | 1 | 1 | ||

| Caesarean section | 2.18 (1.41–3.35) | 2.07 (1.30–3.29)* | ||

| None | 1 | 1 | ||

| Had labour difficulty | 1.94 (1.22–3.07) | 2.05 (1.25–3.35)* | ||

*significant predictors for the delayed initiation of breastfeeding

In this study we found that an unacceptably high proportion of women delayed the initiation of breastfeeding after birth. Studies done between 2013 and 2021 in African countries including Uganda, Nigeria, Ghana, Zimbabwe, South Sudan, Ethiopia and Tanzania demonstrates that the rates of EIBF vary between and within countries ranging from 30 to 83% [ 7 – 10 , 12 – 15 , 18 – 20 ]. Reasons for these findings also vary across contexts. Several studies explain that caesarean delivery is associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding [ 7 – 10 , 13 , 14 , 18 – 23 ]. In our cohort, more than half of the women underwent caesarean section delivery and this could possibly explain the high rate of delayed initiation of breastfeeding. A considerable number of these women in this study also had some form of labour difficulty which was most likely an indication for the caesarean section. A number of infants born to these women also had a health issue after birth probably due to a difficult labour. These infants are likely to have difficulty in sucking. The combination of a caesarean delivery and the baby having a health issue at birth may further contribute to the risk of late breastfeeding initiation. Therefore, mothers who had undergone caesarean section may be less likely to introduce their new born infants to breastfeeding within the recommended one hour after birth.

Consistent with studies done elsewhere [ 7 – 10 , 13 , 14 , 18 – 23 ], our study found that delivery by caesarean section increased the odds of delayed initiation of breastfeeding. Along with caesarean delivery, comes exhaustion arising from the procedure itself and the effects of anaesthesia which may impede the early initiation of breastfeeding. A caesarean section birth takes a lot of time involving the repair of surgical incisions and recovery which may contribute to late breastfeeding initiation.

We found that infants that had a health issue at birth were more likely to delay to start breastfeeding after birth. This finding is consistent with evidence found in other studies [ 24 , 25 ]. These health issues included difficulty in breathing, fever, diarrhoea and the infant being too weak. Infants with health issues at birth may cause the infant to have difficulty in suckling due to weak breastfeeding reflexes, poor coordination and lack of ability to swallow. Further explanations to this effect have already been tucked in the earlier paragraphs.

Women who had received antenatal care less than 3 times while they were pregnant were less likely to initiate breastfeeding within 1 h after birth. This association has been demonstrated in other studies [ 8 , 12 , 22 , 24 , 26 ]. During antenatal care, the benefits of EIBF are always emphasized in health education talks in MRRH. The more the antenatal care visits the women have, the more the interface they make with these health education talks. In this way, these women become more conversant with these counselling messages and are therefore more likely to support their infants in initiating breastfeeding within 1 h after birth.

Women who had a difficult labour were more likely to delay the initiation of breastfeeding. This finding is consistent with evidence found elsewhere [ 8 , 23 , 27 ]. Difficult labour in our study included prolonged labour, body weakness, experiencing a lot of pain, prolonged bleeding and having received an episiotomy. Most of the women that had a difficult labour actually ended up giving birth by caesarean section. This mode of delivery could have contributed to the delay in EIBF as explained in earlier paragraphs. In addition, maternal and foetal indications for caesarean delivery and postoperative care disrupt bonding and mother-infant interaction and delay initiation of breastfeeding.

In our study, women who were single were more likely to practice EIBF. Other studies [ 13 , 24 ] have found contrary evidence to ours. We recommend that a qualitative study can be conducted on this subject matter to best understand the occurrence of this association in our context.

Strengths and limitations

This study was done in a regional referral hospital. Women who deliver at this hospital are probably referred from other lower cadre health facilities due to complications in pregnancy and may most probably require more specialized clinical care. We therefore could have overestimated the prevalence of EIBF. Our study findings may only be generalizable to this nature of population or those similar to it. We never asked any questions on cultural practices that may influence EIBF or why the infants were initiated late. We neither investigated any health system-related factors nor maternal knowledge on EIBF and how these could influence our outcome of interest. We relied on self-reporting of the mother to report on the time of delivery (for both those who delivered normally and by caesarean section) and time of initiation of breastfeeding from which we computed the time interval. This study had some strength, too. We conducted this study among infants that did not exceed 6 days of age. This recall period could have helped to counteract the possibility of recall bias.

Conclusions and recommendations

The proportion of infants that do not achieve EIBF in this setting remains unacceptably high at 70%. Women at high risk of delaying the initiation of breastfeeding include those who: deliver by caesarean section, do not receive antenatal care and have labour difficulties. Infants at risk of not achieving EIBF include those that have a health issue at birth. We recommend increased support in the early initiation of breastfeeding for women who undergo caesarean section by introducing baby-friendly initiatives in hospitals like initiating breastfeeding support in the recovery room after caesarean delivery or in the operating theatre. The importance of antenatal care attendance should be emphasized during health education classes and any other community / public forums like media. Infants with any form of health issue at birth should particularly be given attention to ensure breastfeeding is initiated early. We also recommend a qualitative investigation into the reasons as to why women in this setting delay to initiate breastfeeding for their newly born infants.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mbale Regional Referral Hospital, the study participants and the research assistants for their contribution to this survey.

Abbreviations

| ANC | Antenatal care |

| AOR | Adjusted odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease of 2019 |

| EIBF | Early initiation of breastfeeding |

| MRRH | Mbale regional referral hospital |

| SARS-CoV2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization by LK, AN; Data curation by LK, AN; Formal analysis by LK, AN; Funding acquisition by NR; Methodology by LK, AN; Project administration by NR, LS; Resources by NR, LS; Supervision by AN; Writing of original draft by LK, AN, DM, OS, KK, MI; Review and editing by LK, AN, DM, OS, KK, MI.