- Open access

- Published: 26 November 2021

Women’s Perceptions and Experiences of Breastfeeding: a scoping review of the literature

- Bridget Beggs 1 ,

- Liza Koshy 1 &

- Elena Neiterman 1

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 2169 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

23 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Despite public health efforts to promote breastfeeding, global rates of breastfeeding continue to trail behind the goals identified by the World Health Organization. While the literature exploring breastfeeding beliefs and practices is growing, it offers various and sometimes conflicting explanations regarding women’s attitudes towards and experiences of breastfeeding. This research explores existing empirical literature regarding women’s perceptions about and experiences with breastfeeding. The overall goal of this research is to identify what barriers mothers face when attempting to breastfeed and what supports they need to guide their breastfeeding choices.

This paper uses a scoping review methodology developed by Arksey and O’Malley. PubMed, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, and PsychInfo databases were searched utilizing a predetermined string of keywords. After removing duplicates, papers published in 2010–2020 in English were screened for eligibility. A literature extraction tool and thematic analysis were used to code and analyze the data.

In total, 59 papers were included in the review. Thematic analysis showed that mothers tend to assume that breastfeeding will be easy and find it difficult to cope with breastfeeding challenges. A lack of partner support and social networks, as well as advice from health care professionals, play critical roles in women’s decision to breastfeed.

While breastfeeding mothers are generally aware of the benefits of breastfeeding, they experience barriers at individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels. It is important to acknowledge that breastfeeding is associated with challenges and provide adequate supports for mothers so that their experiences can be improved, and breastfeeding rates can reach those identified by the World Health Organization.

Peer Review reports

Public health efforts to educate parents about the importance of breastfeeding can be dated back to the early twentieth century [ 1 ]. The World Health Organization is aiming to have at least half of all the mothers worldwide exclusively breastfeeding their infants in the first 6 months of life by the year 2025 [ 2 ], but it is unlikely that this goal will be achieved. Only 38% of the global infant population is exclusively breastfed between 0 and 6 months of life [ 2 ], even though breastfeeding initiation rates have shown steady growth globally [ 3 ]. The literature suggests that while many mothers intend to breastfeed and even make an attempt at initiation, they do not always maintain exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life [ 4 , 5 ]. The literature identifies various barriers, including return to paid employment [ 6 , 7 ], lack of support from health care providers and significant others [ 8 , 9 ], and physical challenges [ 9 ] as potential factors that can explain premature cessation of breastfeeding.

From a public health perspective, the health benefits of breastfeeding are paramount for both mother and infant [ 10 , 11 ]. Globally, new mothers following breastfeeding recommendations could prevent 974,956 cases of childhood obesity, 27,069 cases of mortality from breast cancer, and 13,644 deaths from ovarian cancer per year [ 11 ]. Global economic loss due to cognitive deficiencies resulting from cessation of breastfeeding has been calculated to be approximately USD $285.39 billion dollars annually [ 11 ]. Evidently, increasing exclusive breastfeeding rates is an important task for improving population health outcomes. While public health campaigns targeting pregnant women and new mothers have been successful in promoting breastfeeding, they also have been perceived as too aggressive [ 12 ] and failing to consider various structural and personal barriers that may impact women’s ability to breastfeed [ 1 ]. In some cases, public health messaging itself has been identified as a barrier due to its rigid nature and its lack of flexibility in guidelines [ 13 ]. Hence, while the literature on women’s perceptions regarding breastfeeding and their experiences with breastfeeding has been growing [ 14 , 15 , 16 ], it offers various, and sometimes contradictory, explanations on how and why women initiate and maintain breastfeeding and what role public health messaging plays in women’s decision to breastfeed.

The complex array of the barriers shaping women’s experiences of breastfeeding can be broadly categorized utilizing the socioecological model, which suggests that individuals’ health is a result of the interplay between micro (individual), meso (institutional), and macro (social) factors [ 17 ]. Although previous studies have explored barriers and supports to breastfeeding, the majority of articles focus on specific geographic areas (e.g. United States or United Kingdom), workplaces, or communities. In addition, very few articles focus on the analysis of the interplay between various micro, meso, and macro-level factors in shaping women’s experiences of breastfeeding. Synthesizing the growing literature on the experiences of breastfeeding and the factors shaping these experiences, offers researchers and public health professionals an opportunity to examine how various personal and institutional factors shape mothers’ breastfeeding decision-making. This knowledge is needed to identify what can be done to improve breastfeeding rates and make breastfeeding a more positive and meaningful experience for new mothers.

The aim of this scoping review is to synthesize evidence gathered from empirical literature on women’s perceptions about and experiences of breastfeeding. Specifically, the following questions are examined:

What does empirical literature report on women’s perceptions on breastfeeding?

What barriers do women face when they attempt to initiate or maintain breastfeeding?

What supports do women need in order to initiate and/or maintain breastfeeding?

Focusing on women’s experiences, this paper aims to contribute to our understanding of women’s decision-making and behaviours pertaining to breastfeeding. The overarching aim of this review is to translate these findings into actionable strategies that can streamline public health messaging and improve breastfeeding education and supports offered by health care providers working with new mothers.

This research utilized Arksey & O’Malley’s [ 18 ] framework to guide the scoping review process. The scoping review methodology was chosen to explore a breadth of literature on women’s perceptions about and experiences of breastfeeding. A broad research question, “What does empirical literature tell us about women’s experiences of breastfeeding?” was set to guide the literature search process.

Search methods

The review was undertaken in five steps: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant literature, (3) iterative selection of data, (4) charting data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting results. The inclusion criteria were set to empirical articles published between 2010 and 2020 in peer-reviewed journals with a specific focus on women’s self-reported experiences of breastfeeding, as well as how others see women’s experiences of breastfeeding. The focus on women’s perceptions of breastfeeding was used to capture the papers that specifically addressed their experiences and the barriers that they may encounter while breastfeeding. Only articles written in English were included in the review. The keywords utilized in the search strategy were developed in collaboration with a librarian (Table 1 ). PubMed, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, and PsychInfo databases were searched for the empirical literature, yielding a total of 2885 results.

Search outcome

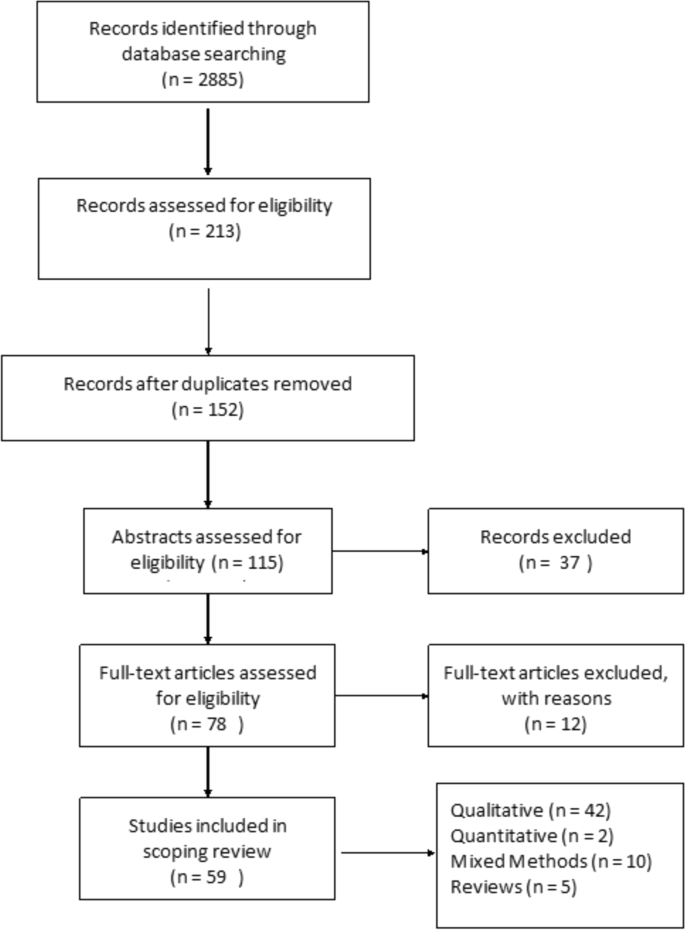

The articles deemed to fit the inclusion criteria ( n = 213) were imported into RefWorks, an online reference manager tool and further screened for eligibility (Fig. 1 ). After the removal of 61 duplicates and title/abstract screening, 152 articles were kept for full-text review. Two independent reviewers assessed the papers to evaluate if they met the inclusion criteria of having an explicit analytic focus on women’s experiences of breastfeeding.

Prisma Flow Diagram

Quality appraisal

Consistent with scoping review methodology [ 18 ], the quality of the papers included in the review was not assessed.

Data abstraction

A literature extraction tool was created in MS Excel 2016. The data extracted from each paper included: (a) authors names, (b) title of the paper, (c) year of publication, (d) study objectives, (e) method used, (f) participant demographics, (g) country where the study was conducted, and (h) key findings from the paper.

Thematic analysis was utilized to identify key topics covered by the literature. Two reviewers independently read five papers to inductively generate key themes. This process was repeated until the two reviewers reached a consensus on the coding scheme, which was subsequently applied to the remainder of the articles. Key themes were added to the literature extraction tool and each paper was assigned a key theme and sub-themes, if relevant. The themes derived from the analysis were reviewed once again by all three authors when all the papers were coded. In the results section below, the synthesized literature is summarized alongside the key themes identified during the analysis.

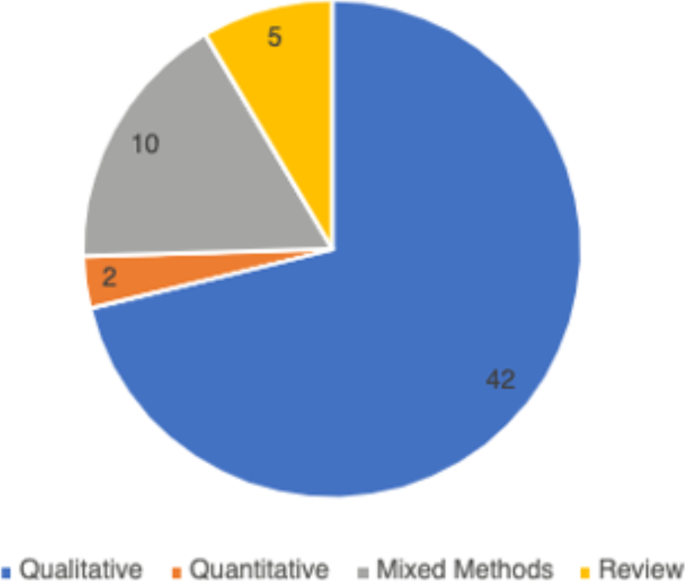

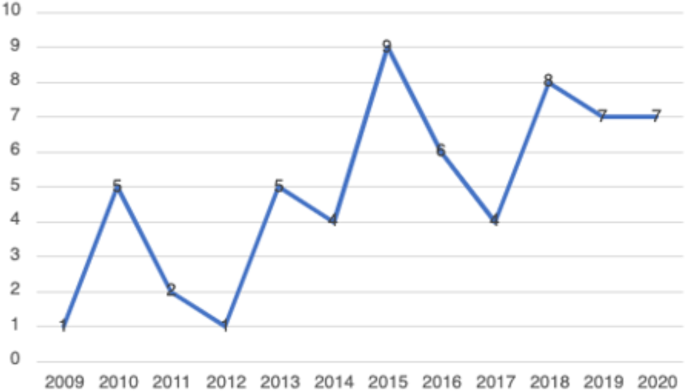

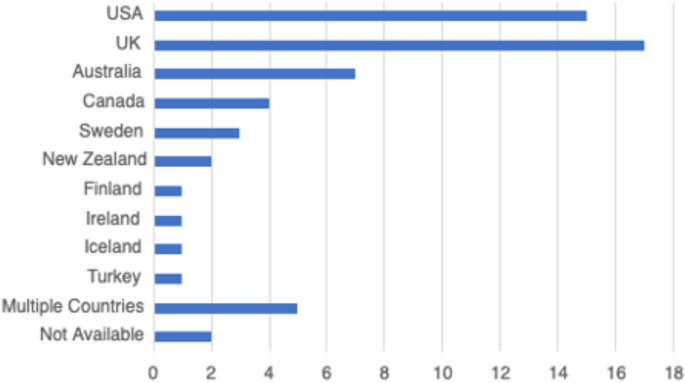

In total, 59 peer-reviewed articles were included in the review. Since the review focused on women’s experiences of breastfeeding, as would be expected based on the search criteria, the majority of articles ( n = 42) included in the sample were qualitative studies, with ten utilizing a mixed method approach (Fig. 2 ). Figure 3 summarizes the distribution of articles by year of publication and Fig. 4 summarizes the geographic location of the study.

Types of Articles

Years of Publication

Countries of Focus Examined in Literature Review

Perceptions about breastfeeding

Women’s perceptions about breastfeeding were covered in 83% ( n = 49) of the papers. Most articles ( n = 31) suggested that women perceived breastfeeding as a positive experience and believed that breastfeeding had many benefits [ 19 , 20 ]. The phrases “breast is best” and “breastmilk is best” were repeatedly used by the participants of studies included in the reviewed literature [ 21 ]. Breastfeeding was seen as improving the emotional bond between the mother and the child [ 20 , 22 , 23 ], strengthening the child’s immune system [ 24 , 25 ], and providing a booster to the mother’s sense of self [ 1 , 26 ]. Convenience of breastfeeding (e.g., its availability and low cost) [ 19 , 27 ] and the role of breastfeeding in weight loss during the postpartum period were mentioned in the literature as other factors that positively shape mothers’ perceptions about breastfeeding [ 28 , 29 ].

The literature suggested that women’s perceptions of breastfeeding and feeding choices were also shaped by the advice of healthcare providers [ 30 , 31 ]. Paradoxically, messages about the importance and relative simplicity of breastfeeding may also contribute to misalignment between women’s expectations and the actual experiences of breastfeeding [ 32 ]. For instance, studies published in Canada and Sweden reported that women expected breastfeeding to occur “naturally”, to be easy and enjoyable [ 23 ]. Consequently, some women felt unprepared for the challenges associated with initiation or maintenance of breastfeeding [ 31 , 33 ]. The literature pointed out that mothers may feel overwhelmed by the frequency of infant feedings [ 26 ] and the amount as well as intensity of physical difficulties associated with breastfeeding initiation [ 33 ]. Researchers suggested that since many women see breastfeeding as a sign of being a “good” mother, their inability to breastfeed may trigger feelings of personal failure [ 22 , 34 ].

Women’s personal experiences with and perceptions about breastfeeding were also influenced by the cultural pressure to breastfeed. Welsh mothers interviewed in the UK, for instance, revealed that they were faced with judgement and disapproval when people around them discovered they opted out of breastfeeding [ 35 ]. Women recalled the experiences of being questioned by others, including strangers, when they were bottle feeding their infants [ 9 , 35 , 36 ].

Barriers to breastfeeding

The vast majority ( n = 50) of the reviewed literature identified various barriers for successful breastfeeding. A sizeable proportion of literature (41%, n = 24) explored women’s experiences with the physical aspects of breastfeeding [ 23 , 33 ]. In particular, problems with latching and the pain associated with breastfeeding were commonly cited as barriers for women to initiate breastfeeding [ 23 , 28 , 37 ]. Inadequate milk supply, both actual and perceived, was mentioned as another barrier for initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding [ 33 , 37 ]. Breastfeeding mothers were sometimes unable to determine how much milk their infants consumed (as opposed to seeing how much milk the infant had when bottle feeding), which caused them to feel anxious and uncertain about scheduling infant feedings [ 28 , 37 ]. Women’s inability to overcome these barriers was linked by some researchers to low self-efficacy among mothers, as well as feeling overwhelmed or suffering from postpartum depression [ 38 , 39 ].

In addition to personal and physical challenges experienced by mothers who were planning to breastfeed, the literature also highlighted the importance of social environment as a potential barrier to breastfeeding. Mothers’ personal networks were identified as a key factor in shaping their breastfeeding behaviours in 43 (73%) articles included in this review. In a study published in the UK, lack of role models – mothers, other female relatives, and friends who breastfeed – was cited as one of the potential barriers for breastfeeding [ 36 ]. Some family members and friends also actively discouraged breastfeeding, while openly questioning the benefits of this practice over bottle feeding [ 1 , 17 , 40 ]. Breastfeeding during family gatherings or in the presence of others was also reported as a challenge for some women from ethnic minority groups in the United Kingdom and for Black women in the United States [ 41 , 42 ].

The literature reported occasional instances where breastfeeding-related decisions created conflict in women’s relationships with significant others [ 26 ]. Some women noted they were pressured by their loved one to cease breastfeeding [ 22 ], especially when women continued to breastfeed 6 months postpartum [ 43 ]. Overall, the literature suggested that partners play a central role in women’s breastfeeding practices [ 8 ], although there was no consistency in the reviewed papers regarding the partners’ expressed level of support for breastfeeding.

Knowledge, especially practical knowledge about breastfeeding, was mentioned as a barrier in 17% ( n = 10) of the papers included in this review. While health care providers were perceived as a primary source of information on breastfeeding, some studies reported that mothers felt the information provided was not useful and occasionally contained conflicting advice [ 1 , 17 ]. This finding was reported across various jurisdictions, including the United States, Sweden, the United Kingdom and Netherlands, where mothers reported they had no support at all from their health care providers which made it challenging to address breastfeeding problems [ 26 , 38 , 44 ].

Breastfeeding in public emerged as a key barrier from the reviewed literature and was cited in 56% ( n = 33) of the papers. Examining the experiences of breastfeeding mothers in the United States, Spencer, Wambach, & Domain [ 45 ] suggested that some participants reported feeling “erased” from conversations while breastfeeding in public, rendering their bodies symbolically invisible. Lack of designated public spaces for breastfeeding forced many women to alter their feeding in public and to retreat to a private or a more secluded space, such as one’s personal car [ 25 ]. The oversexualization of women’s breasts was repeatedly noted as a core reason for the United States women’s negative experiences and feelings of self-consciousness about breastfeeding in front of others [ 45 ]. Studies reported women’s accounts of feeling the disapproval or disgust of others when breastfeeding in public [ 46 , 47 ], and some reported that women opted out of breastfeeding in public because they did not want to make those around them feel uncomfortable [ 25 , 40 , 48 ].

Finally, return to paid employment was noted in the literature as a significant challenge for continuation of breastfeeding [ 48 ]. Lack of supportive workplace environments [ 39 ] or inability to express milk were cited by women as barriers for continuing breastfeeding in the United States and New Zealand [ 39 , 49 ].

Supports needed to maintain breastfeeding

Due to the central role family members played in women’s experiences of breastfeeding, support from partners as well as female relatives was cited in the literature as key factors shaping women’s breastfeeding decisions [ 1 , 9 , 48 ]. In the articles published in Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom, supportive family members allowed women to share the responsibility of feeding and other childcare activities, which reduced the pressures associated with being a new mother [ 19 , 20 ]. Similarly, encouragement, breastfeeding advice, and validation from healthcare professionals were identified as positively impacting women’s experiences with breastfeeding [ 1 , 22 , 28 ].

Community resources, such as peer support groups, helplines, and in-home breastfeeding support provided mothers with the opportunity to access help when they need it, and hence were reported to be facilitators for breastfeeding [ 19 , 22 , 33 , 44 ]. An increase in the usage of social media platforms, such as Facebook, among breastfeeding mothers for peer support were reported in some studies [ 47 ]. Public health breastfeeding clinics, lactation specialists, antenatal and prenatal classes, as well as education groups for mothers were identified as central support structures for the initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding [ 23 , 24 , 28 , 33 , 39 , 50 ]. Based on the analysis of the reviewed literature, however, access to these services varied greatly geographically and by socio-economic status [ 33 , 51 ]. It is also important to note that local and cultural context played a significant role in shaping women’s perceptions of breastfeeding. For example, a study that explored women’s breastfeeding experiences in Iceland highlighted the importance of breastfeeding in Icelandic society [ 52 ]. Women are expected to breastfeed and the decision to forgo breastfeeding is met with disproval [ 52 ]. Cultural beliefs regarding breastfeeding were also deemed important in the study of Szafrankska and Gallagher (2016), who noted that Polish women living in Ireland had a much higher rate of initiating breastfeeding compared to Irish women [ 53 ]. They attributed these differences to familial and societal expectations regarding breastfeeding in Poland [ 53 ].

Overall, the reviewed literature suggested that women faced socio-cultural pressure to breastfeed their infants [ 36 , 40 , 54 ]. Women reported initiating breastfeeding due to recognition of the many benefits it brings to the health of the child, even when they were reluctant to do it for personal reasons [ 8 ]. This hints at the success of public health education campaigns on the benefits of breastfeeding, which situates breastfeeding as a new cultural norm [ 24 ].

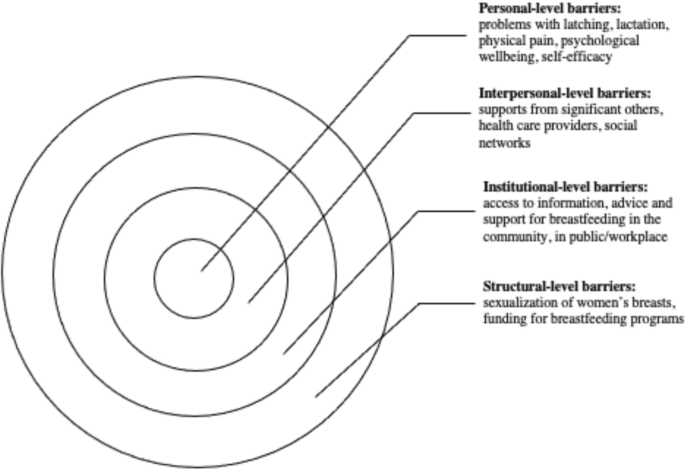

This scoping review examined the existing empirical literature on women’s perceptions about and experiences of breastfeeding to identify how public health messaging can be tailored to improve breastfeeding rates. The literature suggests that, overall, mothers are aware of the positive impacts of breastfeeding and have strong motivation to breastfeed [ 37 ]. However, women who chose to breastfeed also experience many barriers related to their social interactions with significant others and their unique socio-cultural contexts [ 25 ]. These different factors, summarized in Fig. 5 , should be considered in developing public health activities that promote breastfeeding. Breastfeeding experiences for women were very similar across the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, and Australia based on the studies included in this review. Likewise, barriers and supports to breastfeeding identified by women across the countries situated in the global north were quite similar. However, local policy context also impacted women’s experiences of breastfeeding. For example, maintaining breastfeeding while returning to paid employment has been identified as a challenge for mothers in the United States [ 39 , 45 ], a country with relatively short paid parental leave. Still, challenges with balancing breastfeeding while returning to paid employment were also noticed among women in New Zealand, despite a more generous maternity leave [ 49 ]. This suggests that while local and institutional policies might shape women’s experiences of breastfeeding, interpersonal and personal factors can also play a central role in how long they breastfeed their infants. Evidently, the importance of significant others, such as family members or friends, in providing support to breastfeeding mothers was cited as a key facilitator for breastfeeding across multiple geographic locations [ 29 , 34 , 48 ]. In addition, cultural beliefs and practices were also cited as an important component in either promoting breastfeeding or deterring women’s desire to initiate or maintain breastfeeding [ 15 , 29 , 37 ]. Societal support for breastfeeding and cultural practices can therefore partly explain the variation in breastfeeding rates across different countries [ 15 , 21 ]. Figure 5 summarizes the key barriers identified in the literature that inhibit women’s ability to breastfeed.

Barriers to Breastfeeding

At the individual level, women might experience challenges with breastfeeding stemming from various physiological and psychological problems, such as issues with latching, perceived or actual lack of breastmilk, and physical pain associated with breastfeeding. The onset of postpartum depression or other psychological problems may also impact women’s ability to breastfeed [ 54 ]. Given that many women assume that breastfeeding will happen “naturally” [ 15 , 40 ] these challenges can deter women from initiating or continuing breastfeeding. In light of these personal challenges, it is important to consider the potential challenges associated with breastfeeding that are conveyed to new mothers through the simplified message “breast is best” [ 21 ]. While breastfeeding may come easy to some women, most papers included in this review pointed to various challenges associated with initiating or maintaining breastfeeding [ 19 , 33 ]. By modifying public health messaging regarding breastfeeding to acknowledge that breastfeeding may pose a challenge and offering supports to new mothers, it might be possible to alleviate some of the guilt mothers experience when they are unable to breastfeed.

Barriers that can be experienced at the interpersonal level concern women’s communication with others regarding their breastfeeding choices and practices. The reviewed literature shows a strong impact of women’s social networks on their decision to breastfeed [ 24 , 33 ]. In particular, significant others – partners, mothers, siblings and close friends – seem to have a considerable influence over mothers’ decision to breastfeed [ 42 , 53 , 55 ]. Hence, public health messaging should target not only mothers, but also their significant others in developing breastfeeding campaigns. Social media may also be a potential medium for sharing supports and information regarding breastfeeding with new mothers and their significant others.

There is also a strong need for breastfeeding supports at the institutional and community levels. Access to lactation consultants, sound and practical advice from health care providers, and availability of physical spaces in the community and (for women who return to paid employment) in the workplace can provide more opportunities for mothers who want to breastfeed [ 18 , 33 , 44 ]. The findings from this review show, however, that access to these supports and resources vary greatly, and often the women who need them the most lack access to them [ 56 ].

While women make decisions about breastfeeding in light of their own personal circumstances, it is important to note that these circumstances are shaped by larger structural, social, and cultural factors. For instance, mothers may feel reluctant to breastfeed in public, which may stem from their familiarity with dominant cultural perspectives that label breasts as objects for sexualized pleasure [ 48 ]. The reviewed literature also showed that, despite the initial support, mothers who continue to breastfeed past the first year may be judged and scrutinized by others [ 47 ]. Tailoring public health care messaging to local communities with their own unique breastfeeding-related beliefs might help to create a larger social change in sociocultural norms regarding breastfeeding practices.

The literature included in this scoping review identified the importance of support from community services and health care providers in facilitating women’s breastfeeding behaviours [ 22 , 24 ]. Unfortunately, some mothers felt that the support and information they received was inadequate, impractical, or infused with conflicting messaging [ 28 , 44 ]. To make breastfeeding support more accessible to women across different social positions and geographic locations, it is important to acknowledge the need for the development of formal infrastructure that promotes breastfeeding. This includes training health care providers to help women struggling with breastfeeding and allocating sufficient funding for such initiatives.

Overall, this scoping review revealed the need for healthcare professionals to provide practical breastfeeding advice and realistic solutions to women encountering difficulties with breastfeeding. Public health messaging surrounding breastfeeding must re-invent breastfeeding as a “family practice” that requires collaboration between the breastfeeding mother, their partner, as well as extended family to ensure that women are supported as they breastfeed [ 8 ]. The literature also highlighted the issue of healthcare professionals easily giving up on women who encounter problems with breastfeeding and automatically recommending the initiation of formula use without further consideration towards solutions for breastfeeding difficulties [ 19 ]. While some challenges associated with breastfeeding are informed by local culture or health care policies, most of the barriers experienced by breastfeeding women are remarkably universal. Women often struggle with initiation of breastfeeding, lack of support from their significant others, and lack of appropriate places and spaces to breastfeed [ 25 , 26 , 33 , 39 ]. A change in public health messaging to a more flexible messaging that recognizes the challenges of breastfeeding is needed to help women overcome negative feelings associated with failure to breastfeed. Offering more personalized advice and support to breastfeeding mothers can improve women’s experiences and increase the rates of breastfeeding while also boosting mothers’ sense of self-efficacy.

Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations. First, the focus on “women’s experiences” rendered broad search criteria but may have resulted in the over or underrepresentation of specific findings in this review. Also, the exclusion of empirical work published in languages other than English rendered this review reliant on the papers published predominantly in English-speaking countries. Finally, consistent with Arksey and O’Malley’s [ 18 ] scoping review methodology, we did not appraise the quality of the reviewed literature. Notwithstanding these limitations, this review provides important insights into women’s experiences of breastfeeding and offers practical strategies for improving dominant public health messaging on the importance of breastfeeding.

Women who breastfeed encounter many difficulties when they initiate breastfeeding, and most women are unsuccessful in adhering to current public health breastfeeding guidelines. This scoping review highlighted the need for reconfiguring public health messaging to acknowledge the challenges many women experience with breastfeeding and include women’s social networks as a target audience for such messaging. This review also shows that breastfeeding supports and counselling are needed by all women, but there is also a need to tailor public health messaging to local social norms and culture. The role social institutions and cultural discourses have on women’s experiences of breastfeeding must also be acknowledged and leveraged by health care professionals promoting breastfeeding.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Wolf JH. Low breastfeeding rates and public health in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(12):2000–2010. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/ https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.12.2000

World Health Organization, UNICEF. Global nutrition targets 2015: Breastfeeding policy brief 2014.

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). Breastfeeding in the UK. 2019 [cited 2021 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/about/breastfeeding-in-the-uk/

Semenic S, Loiselle C, Gottlieb L. Predictors of the duration of exclusive breastfeeding among first-time mothers. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(5):428–441. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20275

Hauck YL, Bradfield Z, Kuliukas L. Women’s experiences with breastfeeding in public: an integrative review. Women Birth. 2020;34:e217–27.

Hendaus MA, Alhammadi AH, Khan S, Osman S, Hamad A. Breastfeeding rates and barriers: a report from the state of Qatar. Int. J Women's Health. 2018;10:467–75 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6110662/.

Google Scholar

Ogbo FA, Ezeh OK, Khanlari S, Naz S, Senanayake P, Ahmed KY, et al. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding cessation in the early postnatal period among culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) Australian mothers. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1611 [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/7/1611 .

Article Google Scholar

Ayton JE, Tesch L, Hansen E. Women’s experiences of ceasing to breastfeed: Australian qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):26234 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ .

Brown CRL, Dodds L, Legge A, Bryanton J, Semenic S. Factors influencing the reasons why mothers stop breastfeeding. Can J Public Heal. 2014;105(3):e179–e185. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/ https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.105.4244

Sharma AJ, Dee DL, Harden SM. Adherence to breastfeeding guidelines and maternal weight 6 years after delivery. Pediatrics. 2014;134(Supplement 1):S42–S49. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0646H

Walters DD, Phan LTH, Mathisen R. The cost of not breastfeeding: Global results from a new tool. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34(6):407–17 [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://academic.oup.com/heapol/article/34/6/407/5522499 .

Friedman M. For whom is breast best? Thoughts on breastfeeding, feminism and ambivalence. J Mother Initiat Res Community Involv. 2009;11(1):26–35 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://jarm.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/jarm/article/viewFile/22506/20986 .

Blixt I, Johansson M, Hildingsson I, Papoutsi Z, Rubertsson C. Women’s advice to healthcare professionals regarding breastfeeding: “offer sensitive individualized breastfeeding support” - an interview study. Int Breastfeed J 2019;14(1):51. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://internationalbreastfeedingjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13006-019-0247-4

Obeng C, Dickinson S, Golzarri-Arroyo L. Women’s perceptions about breastfeeding: a preliminary study. Children. 2020;7(6):61 [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9067/7/6/61 .

Choudhry K, Wallace LM. ‘Breast is not always best’: South Asian women’s experiences of infant feeding in the UK within an acculturation framework. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(1):72–87. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2010.00253.x

Da Silva TD, Bick D, Chang YS. Breastfeeding experiences and perspectives among women with postnatal depression: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Women Birth. 2020;33(3):231–9.

Kilanowski JF. Breadth of the socio-ecological model. J Agromedicine. 2017;22(4):295–7 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wagr20 .

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract. 2005;8(1):19–32 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tsrm20 .

Brown A, Lee M. An exploration of the attitudes and experiences of mothers in the United Kingdom who chose to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months postpartum. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(4):197–204. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2010.0097

Morns MA, Steel AE, Burns E, McIntyre E. Women who experience feelings of aversion while breastfeeding: a meta-ethnographic review. Women Birth. 2021;34:128–35.

Jackson KT, Mantler T, O’Keefe-McCarthy S. Women’s experiences of breastfeeding-related pain. MCN Am J Matern Nurs. 2019;44(2):66–72 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00005721-201903000-00002 .

Burns E, Schmied V, Sheehan A, Fenwick J. A meta-ethnographic synthesis of women’s experience of breastfeeding. Matern Child Nutr. 2009;6(3):201–219. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00209.x

Claesson IM, Larsson L, Steen L, Alehagen S. “You just need to leave the room when you breastfeed” Breastfeeding experiences among obese women in Sweden - A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):1–10. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://link.springer.com/articles/ https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1656-2

Asiodu IV, Waters CM, Dailey DE, Lyndon • Audrey. Infant feeding decision-making and the influences of social support persons among first-time African American mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:863–72.

Forster DA, McLachlan HL. Women’s views and experiences of breast feeding: positive, negative or just good for the baby? Midwifery. 2010;26(1):116–25.

Demirci J, Caplan E, Murray N, Cohen S. “I just want to do everything right:” Primiparous Women’s accounts of early breastfeeding via an app-based diary. J Pediatr Heal Care. 2018;32(2):163–72.

Furman LM, Banks EC, North AB. Breastfeeding among high-risk Inner-City African-American mothers: a risky choice? Breastfeed Med. 2013;8(1):58–67. [cited 2021 Apr 20]Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2012.0012

Cottrell BH, Detman LA. Breastfeeding concerns and experiences of african american mothers. MCN Am J Matern Nurs. 2013;38(5):297–304 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00005721-201309000-00009 .

Wambach K, Domian EW, Page-Goertz S, Wurtz H, Hoffman K. Exclusive breastfeeding experiences among mexican american women. J Hum Lact. 2016;32(1):103–111. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334415599400

Regan P, Ball E. Breastfeeding mothers’ experiences: The ghost in the machine. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(5):679–688. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732313481641

Hinsliff-Smith K, Spencer R, Walsh D. Realities, difficulties, and outcomes for mothers choosing to breastfeed: Primigravid mothers experiences in the early postpartum period (6-8 weeks). Midwifery. 2014;30(1):e14–9.

Palmér L. Previous breastfeeding difficulties: an existential breastfeeding trauma with two intertwined pathways for future breastfeeding—fear and longing. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2019;14(1) [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=zqhw20 .

Francis J, Mildon A, Stewart S, Underhill B, Tarasuk V, Di Ruggiero E, et al. Vulnerable mothers’ experiences breastfeeding with an enhanced community lactation support program. Matern Child Nutr 2020;16(3):16. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/ https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12957

Palmér L, Carlsson G, Mollberg M, Nyström M. Breastfeeding: An existential challenge - Women’s lived experiences of initiating breastfeeding within the context of early home discharge in Sweden. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2010;5(3). [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=zqhw20https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v5i3.5397

Grant A, Mannay D, Marzella R. ‘People try and police your behaviour’: the impact of surveillance on mothers and grandmothers’ perceptions and experiences of infant feeding. Fam Relationships Soc. 2018;7(3):431–47.

Thomson G, Ebisch-Burton K, Flacking R. Shame if you do - shame if you don’t: women’s experiences of infant feeding. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11(1):33–46. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12148

Dietrich Leurer M, Misskey E. The psychosocial and emotional experience of breastfeeding: reflections of mothers. Glob Qual. Nurs Res. 2015;2:2333393615611654 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28462320 .

Fahlquist JN. Experience of non-breastfeeding mothers: Norms and ethically responsible risk communication. Nurs Ethics. 2016;23(2):231–241. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014561913

Gross TT, Davis M, Anderson AK, Hall J, Hilyard K. Long-term breastfeeding in African American mothers: a positive deviance inquiry of WIC participants. J Hum Lact. 2017;33(1):128–139. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334416680180

Spencer RL, Greatrex-White S, Fraser DM. ‘I thought it would keep them all quiet’. Women’s experiences of breastfeeding as illusions of compliance: an interpretive phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(5):1076–1086. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12592

Twamley K, Puthussery S, Harding S, Baron M, Macfarlane A. UK-born ethnic minority women and their experiences of feeding their newborn infant. Midwifery. 2011;27(5):595–602.

PubMed Google Scholar

Lutenbacher M, Karp SM, Moore ER. Reflections of Black women who choose to breastfeed: influences, challenges, and supports. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(2):231–9.

Dowling S, Brown A. An exploration of the experiences of mothers who breastfeed long-term: what are the issues and why does it matter? Breastfeed Med. 2013;8(1):45–52. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2012.0057

Fox R, McMullen S, Newburn M. UK women’s experiences of breastfeeding and additional breastfeeding support: a qualitative study of baby Café services. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15(1):147. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/ https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0581-5

Spencer B, Wambach K, Domain EW. African American women’s breastfeeding experiences: cultural, personal, and political voices. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(7):974–987. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314554097

McBride-Henry K. The influence of the They: An interpretation of breastfeeding culture in New Zealand. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(6):768–777. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732310364220

Newman KL, Williamson IR. Why aren’t you stopping now?!’ Exploring accounts of white women breastfeeding beyond six months in the east of England. Appetite. 2018 Oct;1(129):228–35.

Dowling S, Pontin D. Using liminality to understand mothers’ experiences of long-term breastfeeding: ‘Betwixt and between’, and ‘matter out of place.’ Heal (United Kingdom). 2017;21(1):57–75. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459315595846

Payne D, Nicholls DA. Managing breastfeeding and work: a Foucauldian secondary analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(8):1810–1818. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05156.x

Keely A, Lawton J, Swanson V, Denison FC. Barriers to breast-feeding in obese women: a qualitative exploration. Midwifery. 2015;31(5):532–9.

Afoakwah G, Smyth R, Lavender DT. Women’s experiences of breastfeeding: A narrative review of qualitative studies. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health. 2013 ;7(2):71–77. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/abs/ https://doi.org/10.12968/ajmw.2013.7.2.71

Símonardóttir S. Getting the green light: experiences of Icelandic mothers struggling with breastfeeding. Sociol Res Online. 2016;21(4):1.

Szafranska M, Gallagher DL. Polish women’s experiences of breastfeeding in Ireland. Pract Midwife. 2016;19(1):30–2 [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/med/26975131 .

Pratt BA, Longo J, Gordon SC, Jones NA. Perceptions of breastfeeding for women with perinatal depression: a descriptive phenomenological study. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2020;41(7):637–644. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/ https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1691690

Durmazoğlu G, Yenal K, Okumuş H. Maternal emotions and experiences of mothers who had breastfeeding problems: a qualitative study. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2020;34(1):3–20. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://connect.springerpub.com/lookup/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1891/1541-6577.34.1.3

Burns E, Triandafilidis Z. Taking the path of least resistance: a qualitative analysis of return to work or study while breastfeeding. Int Breastfeed J. 2019;14(1):1–13.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Jackie Stapleton, the University of Waterloo librarian, for her assistance with developing the search strategy used in this review.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, 200 University Ave West, Waterloo, ON, N2L 3G1, Canada

Bridget Beggs, Liza Koshy & Elena Neiterman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BB was responsible for the formal analysis and organization of the review. LK was responsible for data curation, visualization and writing the original draft. EN was responsible for initial conceptualization and writing the original draft. BB and LK were responsible for reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

BB is completing her Bachelor of Science (BSc) degree at the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo.

LK is completing her Bachelor of Public Health (BPH) degree at the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo.

EN (PhD), is a continuing lecturer at the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo. Her areas of expertise are in women’s reproductive health and sociology of health, illness, and healthcare.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bridget Beggs .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Beggs, B., Koshy, L. & Neiterman, E. Women’s Perceptions and Experiences of Breastfeeding: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Public Health 21 , 2169 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12216-3

Download citation

Received : 23 June 2021

Accepted : 10 November 2021

Published : 26 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12216-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Breastfeeding

- Experiences

- Public health

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 12 May 2020

Helpful and challenging aspects of breastfeeding in public for women living in Australia, Ireland and Sweden: a cross-sectional study

- Yvonne L. Hauck 1 , 2 ,

- Lesley Kuliukas 2 ,

- Louise Gallagher 3 ,

- Vivienne Brady 3 ,

- Charlotta Dykes 4 &

- Christine Rubertsson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7416-6335 5

International Breastfeeding Journal volume 15 , Article number: 38 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

8420 Accesses

15 Citations

36 Altmetric

Metrics details

Breastfeeding in public continues to be contentious with qualitative evidence confirming that women face many challenges. It is therefore important to gain understanding of not only the challenges but also what women perceive is helpful to breastfeed in public.

A cross-sectional study was conducted with women living in Australia, Ireland or Sweden currently breastfeeding or having breastfed within the previous 2 years. Our objective was to explore and compare what women do when faced with having to breastfeed in the presence of someone they are uncomfortable with and what women think is helpful and challenging when considering whether to breastfeed in public. Data were collected in 2018 from an online survey over a 4 week period in each country. Content analysis revealed data similarity and theme names and definitions were negotiated until consensus was reached. How often each theme was cited was counted to report frequencies. Helpful and challenging aspects were also ranked by women to allow international comparison.

Ten themes emerged around women facing someone they were uncomfortable to breastfeed in the presence of with the most frequently cited being: ‘made the effort to be discreet’; ‘moved to a private location’; ‘turned away’ and ‘just got on with breastfeeding’. Nine themes captured challenges to breastfeed in public with the following ranked in the top five across countries: ‘unwanted attention’; ‘no comfortable place to sit’; ‘environment not suitable’; ‘awkward audience’ and ‘not wearing appropriate clothing’. Nine themes revealed what was helpful to breastfeed in public with the top five: ‘supportive network’; ‘quiet private suitable environment’; ‘comfortable seating’; ‘understanding and acceptance of others’ and ‘seeing other mothers’ breastfeed’.

Conclusions

When breastfeeding in public women are challenged by shared concerns around unwanted attention, coping with an awkward audience and unsuitable environments. Women want to feel comfortable when breastfeeding in a public space. How women respond to situations where they are uncomfortable is counterproductive to what they share would be helpful, namely seeing other mothers breastfeed. Themes reveal issues beyond the control of the individual and highlight how the support required by breastfeeding women is a public health responsibility.

The importance of breastfeeding is indisputable and comprehensively supported through recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund [ 1 , 2 ]. A recent UNICEF analysis from 123 countries highlighted that 95% of all babies received some breastmilk. However, rates vary between countries with 4% of babies from low and middle income countries never receiving breastmilk increasing to 21% for babies from high income countries [ 1 ]. Variations exist within high income countries with almost 98% of Swedish babies and 92% of Australian babies receiving breastmilk whereas 55% of Irish babies are breastfed [ 1 ].

Research has revealed challenges around women’s experience of breastfeeding, with one challenge being the management of breastfeeding in public. High income countries such as Sweden, Australia, New Zealand, England, and the United States have provided qualitative evidence on women’s experiences of breastfeeding in public. Although most research explored women’s experiences with breastfeeding in general, a recurring theme around the challenges of breastfeeding in public has consistently emerged.

An interpretative phenomenological study with five Australian mothers’ journey of exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months, revealed shared commonalities related to the difficulties with public breastfeeding with an emphasis on the sexuality of breasts [ 3 ]. To achieve exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months, those who could not overcome their awkwardness with the practice offered expressed breastmilk in a bottle to reach their goal [ 4 ]. Another recent Australian study explored views and beliefs of first time breastfeeding mothers and members of their social network and analysed nine family conversations involving 50 participants [ 5 ]. Participant views were that women were required to be “discreet and covered to not expose the breast, select an appropriate place to avoid discomforting others, guard against judgement and protect herself from unwanted male gaze” [ 5 ]. These common challenges experienced when breastfeeding in public were present and heightened for overweight and obese Swedish [ 6 ], American [ 7 ] and New Zealand women [ 8 ] due to larger breasts and difficulties with latching their babies, which made being discreet problematic and feeling ashamed and self-conscious due to exposure.

Research has identified other groups of breastfeeding women with heightened vulnerability around public breastfeeding which includes African immigrants and refugees. The breastfeeding experiences of 31 African refugee women living in Australia revealed how women perceived the lack of visibility of public breastfeeding contributed to stigma and shame [ 9 ]. Difficulties and being discouraged to breastfeed in public were also noted by 15 African American women who shared issues around sustaining their breastfeeding [ 10 ] and 22 African American mothers who felt stigmatised based upon ‘spectators’ actions’ [ 11 ].

Additional vulnerable groups included young mothers and those living in a country where legal protection to breastfeed in public was limited. An Australian study of 24 young (17 to 25 years of age) mothers focused upon their need for information and support, and found that when breastfeeding in public they felt more exposed as a ‘young mum’ which brought more attention to them: any attention was noted as predominantly negative [ 12 ]. Even British women who are legally protected to breastfeed in public for up to 6 months, but chose to breastfeed longer than 6 months, experienced suspicion and disapproval [ 13 ]. Eight women in this qualitative study shared how they experienced ‘really horrible looks’, ‘stigma from families and community’ and ‘feeling quite exposed’ (p.231).

The influence of perceived cultural norms around breastfeeding in public was also highlighted during interviews with 27 Chinese mothers, who expressed their struggle and embarrassment, given that exposing breasts in their culture was considered unacceptable and ‘uncivilized’ [ 14 ]. Women in Ireland ( n = 7) who shared experiences of being in a public health nurse led support group, valued being in a breastfeeding group that felt like a ‘cocoon of normality’ in a infant formula feeding culture, where breastfeeding was something to be ashamed of [ 15 ].

Research highlighting the experiences of women breastfeeding in public provides insight into this phenomenon whilst exploring breastfeeding experiences in general. Findings have been generated from qualitative research capturing the stories of breastfeeding women across international contexts and have predominately emphasised the negative or challenging aspects of the experience. Although breastfeeding rates to 6 months differ between Sweden (72%), Australia (60%) [ 16 ] and Ireland (26 to 29%) [ 17 , 18 ], similar categories were revealed when women from these countries shared what assisted them to breastfeed [ 19 ]. Informal face to face support and maternal determination ranked within the top five categories across the three countries [ 19 ]. Although regarding breastfeeding as a cultural norm was cited by women living in Australia, Ireland and Sweden, this category was ranked eight out of ten and focused upon the importance of having a strong family history of breastfeeding and having this reinforced with key role models. The issue of managing breastfeeding in public was not acknowledged.

The challenges around breastfeeding in public have been recognised in qualitative studies with small numbers of participants from high income countries. Women’s perceptions of what is helpful when considering whether to breastfeed in public have not been researched and presents a gap in knowledge. Greater insight into what breastfeeding women perceive can help and challenge them can inform initiatives and schemes to counter the challenges and enhance factors to better support their efforts to breastfeed in public. Due to the variation in breastfeeding across high income countries we chose two countries with high initiation rates (Australia and Sweden) and a third with lower rates (Ireland) [ 1 ]. Our international study focused on exploring and comparing what women from three high income countries perceive as helpful or challenging when breastfeeding in public, in addition to revealing what they do when faced with having to breastfeed in the presence of someone they are uncomfortable with.

A cross-sectional study was undertaken using an online survey with women living in Australia, Ireland and Sweden. Ethical approval to conduct the study was granted by Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee in Australia (HRE2018–0037), Research and Ethics Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Trinity College in Ireland (COM_35_17/18) and the Advisory Committee for Research Ethics in Health Education Lund University in Sweden (Reference Number 50–18). Women who were living in Australia, Ireland or Sweden and were currently breastfeeding or had breastfed within the previous 2 years were invited to participate in the online survey through social media.

Three specific research questions were posed: 1) What do women do when they are faced with having to breastfeed in front of someone they are uncomfortable with, 2) What do women think was most helpful when considering whether to breastfeed in public and 3) What do women think was most challenging when considering whether to breastfeed in public? Women were then asked to rank their responses to questions 2) and 3) as first, second or third in importance based upon what they felt were the most helpful and challenging aspects. The online survey was presented on a user-friendly platform suitable for completion on a mobile phone (Qualtrix in Australia, SurveyMonkey in Ireland and Sweden). In addition to the three open ended questions noted above, demographic data on maternal age, education level, number of children / number of children ever breastfed, and whether they were still breastfeeding their youngest child at the time of survey completion was collected.

A poster with a link to the online survey was developed for each country and with university approval circulated through social media. The initial screen was an information letter which included the inclusion criteria. Women had to confirm that they were living in the specified country, met the inclusion criteria and consented to participate prior to accessing the online survey. The original poster was included in a maternity consumer Facebook page in Australia that encouraged women to share with other mothers and within 24 h, over 2600 women had completed the online survey. In Sweden the translated poster was included in several Facebook pages mainly with parental interest such as Home parents network, Public breastfeeding, The breastfeeding help group, Baby slings and Close parenting. In Ireland a link to an online survey was posted on popular Breastfeeding support pages on Facebook. The post provided study details and clicking the link brought women to an information page where they consented to participate before commencing the survey.

Data were collected over a four-week period in 2018 in each country (March in Australia, April in Ireland and December in Sweden). Originally, we anticipated leaving the online survey open for 3 months but due to the overwhelming response from women in all three countries, data collection was ceased after a four-week period.

Responses to the three open ended questions provided rich data that was analysed using content analysis, which is often used with textual data from open-ended survey questions [ 20 ]. Responses to each question were exported from the online platforms into separate Word documents for analysis by investigators in each country. Content analysis involves description at a surface level around individual shared experiences presented in participants’ own words [ 21 ]. A systematic coding and categorising approach was conducted with this textual information to determine common themes [ 22 ]. Content analysis was undertaken by reviewing all responses from women who responded and continued until data saturation became apparent. Initial thematic analysis was conducted separately by two investigators in each country. Tentative themes from data in each country were then shared amongst the international team and it became apparent that themes were more similar than different. Therefore, to facilitate comparison between breastfeeding women living in the three countries, we negotiated final theme names and definitions until a consensus agreement was reached.

Once the final themes were confirmed between countries, we were then able to consider the possibility of counting how often each theme was cited and reported frequencies using descriptive statistics. Due to the numbers of women responding and after themes were confirmed separate SPSS databases were developed and data were then manually entered under each theme. This process facilitated counting how often each theme was cited and ranked as first, second or third in relation to being helpful or challenging when considering breastfeeding in public. At this stage all responses from women in Ireland and Sweden were entered to determine frequencies. As the Australian sample was up to four times larger, a systematic process to collect a representative sample (every second or third entry) was adopted. Statistics were only chosen to describe frequencies of the themes as our intention was not to make inferences or generalizations between women in each country.

Survey respondents included 10,910 women living in Australia, 1835 living in Ireland and 1520 living in Sweden. A summary of characteristics such as age, education level, parity, number of children ever breastfed and whether they were still breastfeeding when completing the survey are presented in Table 1 . The mean age of women living in Ireland was older (34.9 years) compared to women in Australia (32.3 years) or Sweden (32.8 years). The sample reflects women with a high level of education as 89.2% of Irish women had a university or college degree compared to 82.4% from Sweden and 70.6% from Australia. The majority (83.0%) of women living in Australia were born in Australia with 8.4% born in Europe. The majority (81.7%) of women living in Ireland were born in Ireland with 13.7% born in Europe. The majority (93%) of women living in Sweden were born in Sweden with 6% born in Europe.

Faced with having to breastfeed in front of someone they are uncomfortable with

A total of 4742 women living in Australia, 1139 living in Ireland and 1348 living in Sweden responded to this question. Content analysis revealed ten themes commonly cited by women from all three countries. The themes in no particular order were: Made the effort to be discreet; Moved to a private location; Turned away; Just got on with breastfeeding; Never felt uncomfortable; Not my problem; Flagged their intention to breastfeed; Tried to avoid the situation; Used expressed breastmilk (EBM) or infant formula and Had someone supportive with them. A definition of each theme with supporting quotes from women in Australia, Ireland and Sweden is provided in Table 2 .

All responses from women in Ireland ( N = 1139) and Sweden ( N = 1348) were entered into a statistical package to determine frequencies for each response being cited by women from each country. To achieve a number for comparison with Irish and Swedish data, every third response was entered from Australia data ( N = 1600). ‘Made the effort to be discreet’ was cited most frequently across all countries (62.1% in Australia; 44.9% in Ireland; 38.1% in Sweden). The frequencies for each theme are presented in an approximate descending order in Table 3 and were comparable across each country. However, one theme ‘Just got on with breastfeeding’ ranked third for women in Australia (22.8%) and Sweden (20.0%) and fourth at 9.0% for Irish women. Use of expressed breast milk (EBM) or infant formula was ninth for Australian women (1.4%) and Irish women (1.1%) but equal tenth for Swedish women (0.04%).

Challenges to breastfeeding in public

A total of 4596 women living in Australia, 1648 living in Ireland and 1220 living in Sweden provided a response to what was challenging about breastfeeding in public. Content analysis revealed nine themes commonly cited by women across the three countries. The themes were: Unwanted attention; No comfortable place to sit; Environment not suitable; Awkward audience, Not wearing appropriate clothing; Potential for baby to be distracted; Struggling with feeding issues; Managing a distressed baby and Having to manage other children. A definition of each theme with supporting quotes from women in Australia, Ireland and Sweden is provided in Table 4 .

Women were asked to rank their responses to challenges as first, second or third to reflect their importance (Table 5 ). All responses from women in Ireland ( n = 1648) and Sweden ( n = 1220) were entered into a statistical package to determine frequencies and to achieve a number for comparison, every second response was entered from Australia data ( n = 2332). ‘Unwanted attention’ was ranked as first by women in Australia (27.0%) and Sweden (38.2%) with the ‘environment not suitable’ ranked highest by women in Ireland (29.0%) with ‘unwanted attention’ marginally lower at 28.3%. ‘No comfortable place to sit’ was ranked second most frequently (20.1%) by Australian women, third (17.0%) by Irish women and fourth (6.6%) by Swedish women. “Having to manage other children’ was ranked lowest across the countries (1.9, 1.0, 0.2%)”.

One point of difference around perceived challenges noted in the data involved comments around sexism and was expressed by 90 women in Sweden. Examples of comments included: Peoples view on breasts, the sexism of breasts, how men look at you while breastfeeding, to get “undressed” in public and the feeling of being “naked” while breastfeeding. This terminology was not found in comments from women in Ireland or Australia and therefore was not considered a common theme.

Helpful to breastfeeding in public

A total of 4924 women living in Australia, 1744 living in Ireland and 1250 living in Sweden provided a response to what was helpful when considering whether to breastfeed in public. Content analysis revealed nine themes commonly cited by women across the three countries. The themes were: Supportive network; Quiet private suitable environment; Comfortable seating; Understanding and acceptance of others; Seeing other mothers breastfeed; Wearing suitable clothing or having a cover; Preparation and confidence; Breastfeeding is overtly welcomed; and Knowledge of mother’s and children’s rights. A definition of each theme with supporting quotes from women in all three countries is provided in Table 4 .

In a similar process to the challenges, women were asked to rank their responses to what was helpful as first, second or third (Table 5 ). All responses from women in Ireland ( n = 1744) and Sweden ( n = 1250) and every second response from Australia data ( n = 2466) were entered into a statistical package to determine frequencies for each response from women from each country. ‘Supportive network’ was ranked highest by women in Australia (18.6%) and Ireland (28.7%). ‘Understanding and acceptance of others’ ranked highest in Sweden (25.7%), and was second in Ireland (16.4%) and fourth in Australia (15.3%). ‘Seeing other mothers breastfeed’ was comparable across countries (8.2, 11.8, 10.1%) and ‘Knowledge of rights’ ranked lowest in Australia and Ireland (2.7 and 1.4%) whereas ‘Wearing suitable clothing or having a cover’ ranked lowest in Sweden (4.5%).

In summary, although ten themes emerged around strategies women used when facing someone they were uncomfortable to breastfeed in the presence of, the four most frequently cited were: ‘made the effort to be discreet’; ‘moved to a private location’; ‘turned away’ and ‘just got on with breastfeeding’. Nine themes captured challenges to breastfeed in public with ‘unwanted attention’ ranked highest for women in Australia and Sweden whereas ‘environment not suitable’ ranked highest for women in Ireland. Nine themes addressed what was helpful to breastfeed in public and ‘supportive network’ ranked highest for women in Australia and Ireland compared to ‘quiet private suitable environment’ for women in Sweden. ‘Seeing other mothers breastfeed’ ranked in the top five across all three countries.

Challenges to breastfeeding in public identified in this study are supported by previous research. Concepts noted in qualitative studies from seven countries focused on exposure of the body, feeling uncomfortable and vulnerable, embarrassment, perceived lack of acceptability, fear of confrontation or actual negative reactions, positioning challenges, being discreet, and minimising feeding around a particular audience. This synopsis of concepts reflects study findings from Australia [ 23 ], Ireland [ 15 ], Sweden [ 6 ], the United States [ 7 ], China [ 14 ], Canada [ 24 ] and the United Kingdom [ 25 , 26 ]. However, our findings offer further information around additional challenges mothers considered when deciding to breastfeed in public such as the ‘suitability of the environment’, ‘having a comfortable place to sit’, the ‘potential for the baby to be distracted’, ‘managing a distressed baby’, and ‘having to manage other children’. Innovative strategies to address these challenges warrant attention. One example that could be shared and replicated to other local contexts includes the use of technology. A recent study analysed reviews by British mothers on a ‘FeedFinder App’ which involved women sharing information on facilities, service, level of privacy and venue quality to assist decisions around where to breastfeed in public [ 27 ]. This innovation where women assist other women offers an empowering strategy which has implications for business owners as they would be motivated to ensure their facility was positively rated to boost rather than negatively impact their customer base.

Themes that were captured as enablers represent a novel approach with potential modifiable findings to enhance women’s experience of breastfeeding in public. Findings provide insight into areas to target changes and improvements to better support breastfeeding mothers which aligns with the salutogenic model and what contributes to the promotion and maintenance of health. Women’s sense of coherence delineated in the salutogenic model has been applied to infant feeding experiences using constructs such as comprehensibility (belief in understanding challenges), manageability (having sufficient resources) and meaningfulness (desire to respond to challenge) [ 28 ].

Some themes were the reverse of the challenges such as having a ‘supportive network’, the ‘understanding and acceptance of others’, a ‘quiet private suitable environment’, ‘comfortable seating’ and ‘having clothing or a cover’ if the mother chooses to be discreet. Having a supportive network extends beyond face to face contact to locating support through social media. A qualitative study of exclusive breastfeeding with 30 New Zealand mothers found that smartphone apps are a genuine option for promoting breastfeeding. Information is accessed and shared on Facebook amongst breastfeeding mothers who may not have a close relationship but are encouraged by a sense of community [ 29 ]. Even closed Facebook groups such as those hosted by the Australian Breastfeeding Association have been found to provide not only informational but emotional support to breastfeeding women [ 30 ]. Other themes identified in this international study highlight strategies that could be further promoted, such as signage to ‘overtly welcome breastfeeding mothers’, improving opportunities for mothers to ‘see other mothers breastfeeding’, and ensuring women and the general community are aware of ‘mothers’ and ‘children’s’ rights.

Specific themes in our findings address issues that are beyond the control of the individual and require addressing public attitudes to breastfeeding, so women encounter supportive networks that demonstrate understanding and acceptance of breastfeeding in public. Recognition that breastfeeding is a public health responsibility has been supported by evidence suggesting the barriers to breastfeeding extend beyond the individual mother to societal influences [ 31 ]. Increasing awareness of mothers’ and children’s rights around breastfeeding may present a necessary tactic to inform and educate the public of the importance of breastfeeding to our society and our future generations. Signage that overtly welcomes breastfeeding, that provides an environment with comfortable seating, gives a message that endorses a culture where breastfeeding is seen as ‘normal’. Community involvement is essential for any change process as illustrated in a recent inquiry approach to discover how communities can better support breastfeeding. Community conversation workshops were recently undertaken with Australian parents, grandparents, children’s services, local government, health services and retail owners [ 32 ]. Two related themes were revealed acknowledging the importance of PLACE: ‘sometimes a PLACE to breastfeed’ and ‘the parent room: a hidden and unsafe PLACE to breastfeed’. Although characteristics of communities that provided a ‘sanctuary’ were noted, the participants indicated that breastfeeding in public was rarely observed which supports the theme ‘seeing other mothers breastfeed’ as being an important enabling theme.

‘Made the effort to be discreet’ was the most frequently cited strategy that women across Australia, Ireland and Sweden noted when faced with having to breastfeed in front of someone they are uncomfortable with. Other themes included ‘moving to a private location’, ‘turning away’, and ‘tried to avoid the situation’ which are all activities counterproductive to the helpful theme of wanting to ‘see other mothers breastfeed’. A recent discussion paper on the requirement to justify breastfeeding in public suggests that if breastfeeding could be recognised as a “family way of life” and positive interaction this stance would support a “more right to breastfeeding in public without social sanction, whether one is able to breastfeed discreetly or not” [ 33 ].

Facilitating a culture where breastfeeding in public is acceptable and women feel comfortable require initiatives to address societal attitudes given that ‘unwanted attention’ and ‘awkward audience’ also ranked within the top four themes negatively influencing a decision to breastfeed in public. Interventions to change societal attitudes have met some success and highlight strategies that can be shared internationally. For example, a prime-time television clip depicting public breastfeeding decreased the extent to which American students believed breastfeeding should be private while improving attitudes and support for breastfeeding in public [ 34 ]. Use of a music video parody with young Canadian adults found that shorter intervals between seeing the video and shorter intervals between follow-up ratings measured increasing comfort levels thereby reinforcing the importance of being exposed to breastfeeding [ 35 ]. Finally, another study included use of posters to enhance comfort levels with members of the Canadian public surveyed at shopping centers and found that only 51.9% were comfortable with a woman breastfeeding anywhere in public but this increased to 84.5% in a doctor’s office or 81.4% in a park [ 36 ]. There were significant improvements in comfort levels following viewing of promotional posters depicting breastfeeding in a doctor’s office and restaurant.

The influence of seeing a woman breastfeed extends beyond being an enabler to existing breastfeeding women and can influence the decision whether to breastfeed at all. A systematic review focused on factors influencing expectant parents infant feeding choice revealed a bias towards negative factors relating to the breastfeeding decision as parents went through a process of weighing reasons for and against breastfeeding [ 37 ]. Factors influencing choice of infant feeding method included female role models, family and support network and feeding in front of others/public. Expectant parents are already aware and thinking about how they could manage breastfeeding in public [ 37 ]. A longitudinal study with 259 Scottish first time mothers who had never breastfed and agreed with a statement that ‘it was lovely to see her breastfeed’ were six times more likely to intend to breastfeed [ 38 ].

Coordinated action and targeted strategies must consider all factors to address the challenges women experience when breastfeeding in public. To facilitate the promotion and support of breastfeeding, all influencing factors must be acknowledged within an ecological model, such as the mother and infant dyad, the family, the health care system, the community and societal and culture factors [ 39 ]. Breastfeeding represents a complex experience. Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis recommended that multicomponent interventions be implemented across the childbirth continuum to include antenatal and postnatal periods, hospital and community contexts and the involvement of health professionals [ 40 ]. A multifaceted approach where support needs to be layered was recommended in a Health Promotion Strategic Framework in Australia to include mothers, family and community [ 41 ]. Awareness of this approach is apparent in the Australian National Breastfeeding Strategy that endorses the need for a social marketing campaign targeting specific audiences to change attitudes and behaviours regarded as unsupportive of breastfeeding [ 42 ].

More women from Sweden than Australia or Ireland shared comments about sexualization of the female body, the ‘male gaze’, and a feeling of being attributed to a sex object when breastfeeding. Without existing evidence, we cannot speculate the reason for the differences between countries and why Swedish women were more aware and outspoken about sexism. Therefore additional international research is warranted around this issue to further explore how awareness and expression of this concern may differ depending upon a particular context or culture.