- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Parsing the Endless Nuances of British Stereotypes

And what it means for writing british characters.

English people are hard to write, as an American novelist. I’ve lived in London now for most of the last 20 years, but I still hesitate to put them into fiction, mainly because it’s difficult to avoid slotting them into categories. “It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth,” George Bernard Shaw famously wrote, “without making some other Englishman hate or despise him.” Which also means there are some advantages to being an American in Britain—you can operate vaguely outside class-cultural lines.

Of course, British people are also totally capable of despising Americans. All you have to do is say BernARD, for example, with the stress on that second syllable, or “Mos-cow,” to rhyme with “how,” and wait for the flicker of suppressed amusement. I should add that my exposure to Britishness is really to a fairly specific pocket of north London, and I don’t want to make grand claims. That’s the trouble. It’s very easy to get this stuff wrong.

Part of the puzzle of Brexit, for Americans, is that so many of the main players represent barely distinguishable but traditionally opposed British types. In American terms, both Jeremy Corbyn and Theresa May would probably belong to a generic upper middle class. Both were raised outside London, in comfortable country houses, and have a bit of private schooling in their backgrounds. Corbyn and May also spent time in state grammars, highly selective public schools, which have become a bone of contention between left and right wing views of progressive education policy.

Corbyn represents the borough next door to mine, Islington, which is the poster borough for a certain kind of cosmopolitan elite. Just the phrase “North London” tends to serve as code for various semi-contradictory things. It can mean “Jewish,” but it can also mean the sort of muesli-eating, Guardian -reading, Labour-voting lefties whose reasonable objections to Israeli policy sometimes shade uncomfortably into anti-Semitism. You can see these people in Mike Leigh movies. They keep allotments, ride bicycles, even into their seventies, and carry their groceries in Daunts Books tote bags, except that they would never say “tote,” which is an Americanism.

But the culture divide between Corbyn and May is stark—you have only to listen to their accents. Some of that can be put down to regionalism, even though it’s only two hours in the car between the towns where they went to school.

The pressures of class affect people in complicated ways. I’ve written before of my old Etonian roommate who refused to help me tie a bow-tie for an Oxford ball. His mother lives in a beautiful rambling 15th-century farmhouse in Berkshire, one of those commutable-to-London counties that still looks genuinely rural, if you squint a little. (Kate Middleton’s parents live there, too.) My English wife gets nervous when we visit them, because they’re “posh,” and she worries about doing or saying the wrong thing. This used to baffle me. Both of them went to private schools and Oxford, they have recognizable upper-middle-class accents… they seem equally posh to me. But Ned’s family reads The Telegraph , not The Guardian , cooks on an Aga, has pelmets over the curtains, and a carpeted house where it’s not a bad idea to take your shoes off. It turns out all of this is stressful for London liberals.

Two typically English phrases sum up the difference. Theresa May’s Tory colleague Ken Clarke—the sort of old-fashioned conservative who says what he thinks, independent of party lines—once called her a “bloody difficult woman.” That’s not the phrase I mean, though May has often repeated the remark, proudly, because it gives her a kind of vividness or identity; it places her in a tradition that includes Margaret Thatcher. It also suggests the natural evolution from the vicar’s daughter—dutiful, diligent, hard to distract, conventional in her way, but also single-minded. In other words, she’s the kind of woman who might have been described once as a “girly swot.”

To swot is to study hard for an exam, to sweat for it, to strive. “Girly swot” is a phrase I’ve most often heard women use about themselves. It’s a kind of humble-brag, though maybe it’s really the opposite, a form of boast whose real purpose is to self-deprecate. Because underneath the boast it also means, I only got where I am through extra hard work, I’m not necessarily talented or original, but I put my head down and plough on, especially when there’s a set task. And yet inside that self-deprecation is another level of boast. I do my job, I do my duty, I earn my success—and there’s also a hint of the implication that maybe things like creativity and originality are shallower virtues, not quite to be trusted.

This has been May’s line on the referendum from the beginning: we will honor it, we will finish the homework assignment we’ve been set by the British people, whether we believe in it or not. (May, of course, voted Remain.) We will pass the test.

Corbyn was not a girly swot. He left school with two E-grade A-levels, the lowest possible passing grade, and never finished university—he dropped out after a couple of semesters at North London Polytechnic. (May went to Oxford.) But in its own way, Corbyn’s background is just as conventional. He joined the CND (the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament), wrote for a local newspaper, got involved in union politics. And in his case, the phrase that comes to mind is “right on.”

It usually goes alongside some kind of left-wing cause, and, like “girly swot,” is hard to parse in terms of mockery or admiration. Partly because the people who use it often share to some extent the views they’re describing. To be “right on” shows enthusiasm, it shows energy, it suggests a kind of enviable thoroughness or depth or correctness of belief. Yet there’s a sting in the tail, too, because it also suggests a lack of irony or self-awareness or real self-doubt, and, like “girly swot”, indicates an excess of conventionality at the expense of true thought or feeling. To be “right on” is probably to go “by the book”—to accept received views and embrace them in a way that might be a little embarrassing, even to people who basically agree with you.

Both of these politicians, in other words, come straight from central casting. I can’t even tell if that’s an English phrase or not anymore, I’ve lived in the country too long. You really couldn’t make them up, because you don’t need to; they’re all stock cultural figures. From May to Corbyn, to Jacob Rees Mogg, the leader of the hard Brexiters, whose double-barrelled name belongs in a John Mortimer novel and makes him sound like the kind of privileged man-child, who goes straight from prep school, to boarding school, to Oxford, to the bar or some private bank, and still defers to Nanny at home.

I don’t mean to make fun of any of them, just to show how dense with types the culture is, and how the only reasonable response to that density is to retreat into subtleties or ironies. It makes satire easier, and realism harder for novelists, at least the kind of realism where you want your characters to wear a looser skin, to have a little room for maneuver underneath all the descriptions you throw at them. And I wonder if the fine grain of British class and culture mean something similar for non-writers, too—I mean, for the people who live it, and are going to have to get along with each other again, after Brexit happens or doesn’t happen, in whatever form.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Benjamin Markovits

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Going Deep into the Canadian Subarctic for Research

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

The New York Times

The learning network | in ‘other’ words: writing gently humorous essays about stereotypes.

In ‘Other’ Words: Writing Gently Humorous Essays About Stereotypes

Language Arts

Teaching ideas based on New York Times content.

- See all in Language Arts »

- See all lesson plans »

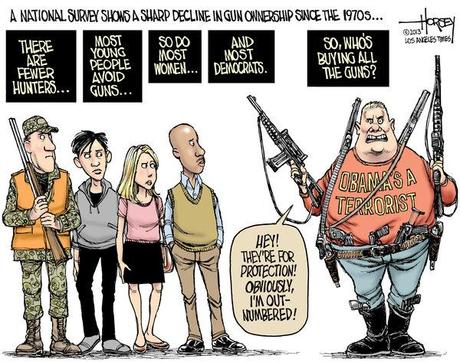

Overview | How do stereotypes inform our ideas about others? How can we go beyond these misconceptions for a truer look at an “other”? In this lesson, students read a gently humorous essay examining British stereotypes about Americans, consider stereotypes and misconceptions of people in various groups and write lighthearted personal essays.

Warm-up | This lesson’s warm-up asks students to generate stereotypes they have about a specific “other.” Given the content of today’s featured piece from The Times, and depending on your curriculum, students might generate stereotypes about one of the following:

- Europeans in general

- The citizens of a specific country where a literary work or historical time period they are studying is set

- A group of figurative “foreigners” – like people in a “rival” town or state, fans of a rival professional or school team, or something along those lines, as long as they are appropriately “foreign” to your students

To begin, ask students to list stereotypes they associate with the group you have decided to focus on. Then, invite students to share their stereotypical characteristics and write them on the board. Make it clear that you are focused on stereotypes as exactly that — oversimplifications, generalizations, usually based on limited or inaccurate information. You may also wish to set some ground rules to ensure that the discussion is honest yet respectful and appropriate.

As the list of stereotypes is generated, call upon other students to complicate the generalizations that begin to crop up. Aim to have one piece of information based on a real encounter with a member of this group for every generalization listed. Invite students to share their own stories of times when their misconceptions of this group were clarified or altered.

Ask: What are the limits of these stereotypes? Why do some of us tend to stereotype this group in this way? Why is it tempting to stereotype the “other”?

Finally, show students the illustration that accompanies The Times piece “Letter From London: My American Friends.” Ask: What stereotypes of Americans does this illustration highlight? From whose point of view does it come, do you suspect? Then ask students to list other stereotypes associated with Americans abroad , and to list these on the board, in the left-hand column of a T-chart (the other side will be filled in after reading the article). Why do you suppose Europeans stereotype Americans in these ways? What is your response to the list?

Related | In his “Letter From London” titled “My American Friends,” Geoff Dyer tells the story of how Americans have resisted and contradicted Europeans’ preconceived notions of them:

The first thing I ever heard about Americans was that they all carried guns. Then, when I came across people who’d had direct contact with this ferocious-sounding tribe, I learned that they were actually rather friendly. At university, friends who had traveled in the United States came back with more detailed stories, not just of the friendliness of Americans but also of their hospitality (which, in our quaint English way, was translated into something close to gullibility). When I finally got to America myself, I found that not only were the natives friendly and hospitable, they were also incredibly polite. No one tells you this about Americans, but once you notice it, it becomes one of their defining characteristics, especially when they’re abroad.

Read the entire personal essay with your class, using the questions below.

Questions | For discussion and reading comprehension:

- What are some of the preconceived notions Dyer identifies about Americans? To what extent are they true?

- What exactly does Dyer mean in the second paragraph when he says “it says something strange about the way that perception routinely conforms to the preconceptions it would appear to contradict”? What is “it”? What is “strange”?

- What do the loud voices of visiting Americans really signify, according to Dyer?

- What is the answer to question Dyer poses mid-essay, “What is the relevance of this anecdotal trivia to a serious debate about the status of America in the world?”?

- What techniques does Dyer use to prevent his essay from becoming barbed or sarcastic? How does he manage to keep it honest, yet lighthearted?

RELATED RESOURCES

From the learning network.

- Lesson: A Rose By Any Other Name?

- Lesson: Ambassadors of Annoyances?

- Lesson: Conflicts of Interest

From NYTimes.com

- Times Topics: Americans Abroad

- Essay: “Still ‘Ugly’ After All These Years”

- Op-Ed: “Yes, Like Obama”

Around the Web

- Discovery Education: Understanding Stereotypes

- Time Magazine: “Behavior: Breaking the American Stereotypes”

- Teaching Tolerance

Activity | As a group, add to the left-hand column of the T-chart on the board any additional stereotypes that Europeans, particularly the British, have about Americans that were mentioned in Dyer’s essay. Then list the traits Dyer finds admirable in Americans in the other column.

Ask: How do the British apparently perceive Americans? What do these stereotypes reveal about Americans? About the British? What generalizations does Dyer paint of his own culture?

Ask students to consider the tone of Dyer’s essay. What purpose do you think he is trying to achieve? How does the use of anecdotes and humor help him achieve these purposes? How does he manage to avoid being offensive or cruel in discussing stereotypes? How does he manage to be humorous without being sarcastic?

Tell students that will now prepare to write essays like Dyer’s, in which they examine and perhaps shatter misconceptions they have held about a group of people, using humor and a personal, playful tone.

Here is a suggested process for essay writing preparation:

Choosing a Subject:

- Stress that personal experience with the “other” being written about is essential.

- To make this lesson more experiential, require students, for homework, to spend some time observing members of the “other” group, by doing something like going “undercover” at the evening’s basketball game to observe and mix with fans of the rival team. You may want to subject students’ plans to approval before they start out.

- Once students have subjects for their essays, ask each of them to come up with a list of misconceptions or preconceived notions they have about that group. Teachers may wish to invite students choosing to write about the same group to brainstorm their misconceptions and preconceived notions together.

Prewriting:

- Students create T-charts to compare the misconceptions with the reality, noting what observations would or would not support the misconceptions they held about their group before this activity.

- Students should also free write about how experiences with the “other” group prompted them to reflect on their own culture, as it were, as Dyer does. Remind them to avoid clichés and generalizations and to be as specific as possible.

- Encourage them to borrow Dyer’s first two lines as a starter:

The first thing I ever heard about _________ was _________. Then, when I came across people who’d had direct contact with [them], I learned that they were actually_________.

- Pair students so that they can “test” some of their material on each other by sharing two telling anecdotes (like those employed by Dyer) that they might include in their essays and at least one humorous tidbit that would contribute to achieving a tone similar to that struck by Dyer. Have partners respond to what they hear and offer advice to one another on whether or not these elements work for them as members of the audience.

When essays are finished, hold a “read around” in which each student shares a crucial section from his or her essay, and invite students to respond to each other. Then hold a final discussion about the process and what they got out of it.

Going further | Students interview several members of the group they chose to write about, so that they are forced to see the group from an “insider’s” perspective. They then revise their essays to include reflections on these interviews.

Alternatively or in addition, students individually do our Culture Shot activity (teacher directions are here ), using a current print edition of The Times, the online Times multimedia and photo index and/or the Lens blog . After they share their choices, lead a discussion about what these images might convey about Americans to people from other countries and cultures. You might also repeat the activity using images of, say, Europeans.

Standards | From McREL , for grades 6-12:

Behavioral Studies 1 – Understands that group and cultural influences contribute to human development, identity and behavior 4 – Understands conflict, cooperation and interdependence among individuals, groups and institutions

Language Arts 1 – Uses the general skills and strategies of the writing process 5- Uses the general skills and strategies of the reading process 7- Uses the general skills and strategies to understand a variety of informational texts 8- Uses listening and speaking strategies for different purposes

Life Skills: Working With Others 1- Contributes to the overall effort of a group 4 – Displays effective interpersonal communication skills

Geography 10 – Understands the nature and complexity of Earth’s cultural mosaics

Comments are no longer being accepted.

Don’t know if you’ve seen this, but even though you are lying next to me right now, you are asleep. This and other stuff is on something the NYT calls the Learning Network.

Great nice writing and tips that you have proved…

Nice sort of information thanks for the post sharing…..

What's Next

British Stereotypes: Fact or Fiction?

Learning about a country’s culture is often the most interesting element of studying a foreign language. It is so much easier to learn when you can understand what makes a country tick - and communicate more easily with its people. Luckily for learners of British English , the culture of the United Kingdom is well known across the world. This is in part thanks to global hit TV shows and films like Downton Abbey and Harry Potter, musicians like The Beatles and Adele and public figures like Queen Elizabeth II or Winston Churchill. All these cultural legends have given way to a certain image, or stereotype, of the British.

Some of these stereotypes are very much true. Others less so! We decided to ask the resident Brits at Tandem about some of the most popular stereotypes about British people, and separate the fact from the fiction!

The Tandem app isn’t just about language exchange, it’s also about cultural exchange and fostering meaningful conversations with people from all over the world. Break down barriers and celebrate diversity by downloading the app now!

Brits love talking about the weather - FACT

“Brits love small talk and our favourite topic has to be the weather outside. Commenting on the rain or sunshine is always a great conversation starter for us. Great Britain is an island, and therefore blessed with an unpredictable maritime climate. This means there is always something to discuss! Snow in particular is a massive deal for us - a few inches can send the whole country into meltdown. Equally, we can’t cope with heat over 30 degrees, which usually only happens for a few days in the summer. Ultimately, much as we like to complain about it, we’re happiest with the mild, wet weather our country is most known for!”

It rains all the time - FICTION

“People are often surprised when they come to London or Edinburgh and it’s sunny! It can sometimes feel like it rains all the time, but actually we receive average rainfall when compared with the rest of Europe."

Brits love to drink tea - FACT

“Ooooh, put the kettle on, will you? Tea is definitely a key part of British culture. Making tea for other people is the ultimate form of British hospitality. People from abroad tend to think we only drink the finest tea leaves from teapots, served in a beautiful cup and saucer. In reality, we buy bog-standard tea-bags by the kilo and make constant mugs of it throughout the day. It may not be posh, but it’s the quickest way to make a brew! And since you asked, we ALWAYS add a dash of milk to our black tea (no lemon, are you mad??)”

Brits are obsessed with The Royal Family - FICTION

“Most British people are proud of their Queen - but it isn’t true that we ALL love the royal family. There are so many royals knocking about and most of them don’t seem to do much! It’s another thing we tend to complain about. That said, Princess Catherine has to be one of the most glamourous Brits alive, so we are secretly very happy about that.”

Brits love queuing - FACT

"Why the rest of the world seems to not be able to queue as well as us remains a great mystery. Seriously. Is it really that hard?????”

Brits have bad teeth - FICTION

“Whoa, these stereotypes are harsh. Where did this one come from? We do actually have very good dentists in the UK. I don’t think our teeth are worse than anyone else's, to be honest!"

Brits have a British accent - FICTION

“I am still a bit confused about what people mean by a British accent. Perhaps the southern English accent is most commonly heard abroad, but most people in the UK simply don’t speak like this! Though we are a small island, there are so many different accents in the UK and we are immensely proud of this. You can usually tell a lot about a person’s background just by listening to their voice. And be warned… complimenting someone from Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland on their “English” accent is NEVER going to go down well!”

Brits are super polite - FACT

“British people don’t like to be overtly rude, that’s true. We say “sorry”, “please” and “thank you” a lot. But saying polite words doesn’t necessarily mean that we mean it! I’m not sure if this counts as a fact if we don’t really mean it. For example, we often say “sorry” if someone does something to us - for example if someone bumps into you, you would might automatically apologise - but of course deep down you know you did nothing wrong and you’re seething with resentment. That’s just our way, I guess!”

British food is terrible - FICTION

“I can see why people might come to the UK for the first time and be unimpressed by our “traditional” cuisine. Pies, pudding and fish & chips might seem stodgy and bland in comparison with other European food. HOWEVER - British cuisine has been greatly influenced by global tastes for hundred of years, and this is something I think we have turned to our advantage. For example, try a curry in the UK and you will not be disappointed! Plus we have some of the best restaurants and markets in the world. London, Manchester and Glasgow in particular have an incredible foodie scene. And you can't beat a British-style Sunday roast!”

All Brits wear hats - FICTION

“Perhaps it’s because the Queen always wears a hat, but this is definitely not true! Brits stopped wearing hats on a daily basis in the 1960s, like everyone else.”

And that's all folks! Toodle-pip! Cheerio!

Connect with native speakers globally and practice speaking any language for free!

How Long Does it Take to Learn a New Language?

Discover how long it takes to learn a new language and the factors that affect the time needed for language learning. From fresh to fluent, learn more here!

International Women’s Day

Learn all about the history of International Women's Day, its significance, and how to celebrate it around the world.

A Guide to Italian Grammar: Essential Basics and Beyond

In this guide to Italian grammar, we'll cover the basic rules to get you started, including parts of speech, verb conjugation, and more.

11 British Stereotypes and the Honest Truth

This post contains affiliate links for which I may make a small commission to help keep the site running. You will not be charged extra for these items had you not clicked the links. Thank you for your help to keep the site running!

Ever wonder which British stereotypes are true and which aren’t?

What do people think of the Brits, and is it really accurate in real life?

When talking about these British stereotypes, let’s keep in mind that all stereotypes are generalizations.

Just because most British people drink tea (this is a true stereotype about the British!), doesn’t mean that every single person does – duh.

But as an American who has lived in the UK for over 10 years, I’ve come to realize which of these stereotypes about British people are true and which aren’t, and that’s what we’re diving into today because the world deserves to know that British food isn’t bad, and that British people really do love talking about the weather!

So whether you’ve moving to the UK or just coming for a visit, bookmark this page!

1. They Drink a Lot of Tea: true

One of the oldest and most common British people stereotypes is that they drink a lot of tea.

And this is so true.

The UK ranks third in the world when it comes to tea consumption, and tea here is enjoyed by all of the social classes.

While it began as an elixir for the upper class, it soon became more available to the middle class and finally trickled down to the working class who enjoyed it as a way to warm up and take a break from a hard day of labor.

Tea in the UK isn’t just something to drink. It’s a culture and a truly comforting aspect of the day for many people.

So, yes, it’s true that Brits love tea, and if you want to learn more about what I’ve learned about British people and tea, check out my video about the differences between American and UK tea!

2. British Food isn’t Good: false

British food has a reputation of not being good, and that turns a lot of people away from trying “British” cuisine, but actually this isn’t true.

Whether it’s a perfectly done sausage roll, a freshly battered fish and chips , a scotch egg or a full English breakfast, there are so many wonderful and filling foods in Britain to true.

So where does this British stereotype come from?

In my opinion, having lived here for 10 years, there are two reasons.

The first, and this is an unfair reason, is that many of the stereotypes about British food are sort of stuck in the post-war era, when the country was on hard times and people were on rations.

It seems that the stereotype hasn’t updated for many people since then.

However, the perhaps more fair reason for this negative stereotype is that I have found it common for Brits to not season their food or use as much flavor as they would in other cuisines.

Definitely there is a little bit of truth to vegetables cooked at home being often boiled, for instance, instead of other more flavorful methods of cooking, but this is down to the individual and doesn’t mean that the entire country lacks culinary skills.

3. British People are Polite: true and false

One of the positive stereotypes about British people are that they are polite.

In my experience, this is both true and untrue.

The truth is that yes, British people are very polite from an outsider’s perspective!

I would say they are far more polite than us Americans in general day to day life, and they are more unassuming and willing to cooperate in social settings.

That being said, there is nothing the British are better at than a really good passive-aggressive “tut” at someone when they do something wrong, like cutting them in line (the queue) or standing on the left-hand side of the tube (never do that).

So while they are seemingly polite and you wouldn’t expect a British person to bash through a crowd or have an insane amount of road rage, they’re definitely judging you inside (and we love them for it!)

4. Brits Have Bad Teeth: false

One of the negative stereotypes about British people is that they have bad teeth, particularly when compared to Americans.

I’m saying this stereotype is false, because what the case really is is not that British people have overwhelming unhealthy teeth, but rather that there is not an emphasis on cosmetic dentistry in the UK like there is in the US.

Americans are all about their smile – dentists make a ton of money each year “fixing” people’s smiles and whitening teeth, but in the UK, dentistry is more back to the basics of making sure that your teeth are healthy and not filled with cavities or gum disease or other ailments, but there isn’t much beyond that for many people.

So of course, when you compare a British person’s natural teeth with the teeth of someone in America who may have a dentist appointment every 6 months or regular whitening or Invasalign or all of the ways Americans

5. Everyone is Classy: false

There’s a stereotype of British people that everyone seems to wear a top hat and be the classiest person you’ve ever met, and while there are definitely some people like that, it’s untrue that the entire nation is somehow more sophisticated than the rest of the world!

British people are…people, too, and there are definitely some British people who make a bad name for themselves when traveling abroad (there is a whole stereotype about British people by Europeans that they can be the nationality you don’t want to come visit your resort because they’ll just be loud and obnoxious – see, it’s not just Americans who get stereotyped like this!).

I’m not saying British people aren’t classy to put anyone down, I’m just saying British people are human and they’re not all how people like David Beckham and Posh Spice portray themselves.

There’s a whole mixture of classes, social backgrounds, and level of “refinement” – just like any other country.

6. British People Speak like the Queen: false

While you may be most familiar with the accents of the Royals or of British actors or musicians, it’s a false stereotype that that is the main British accent.

It’s a specific British accent, known as Received Pronunciation , and it’s definitely an upper class accent.

It’s also relatively easy to understand.

But it’s often said that British accents change as you turn the corner, much less go to a new town or city and a London accent is very different from the Royal’s accent which is very different from a Liverpool accent or a Scottish accent or a Welsh accent – the list goes on.

So, no, they don’t all speak like the Queen – and that’s a good thing for the diversity of accents you’ll get to hear within the UK.

7. They Say Sorry a Lot: true

One stereotype about British people is that they say ‘sorry’ a lot, and this is definitely true.

It’s sort of just a filler word in social situations, mainly, to express that they apologize for any sort of inconvenience or for doing anything that could have gotten in your way.

So they’re not fully, heartily, apologizing, but rather being polite with a lot of “oh sorry, can I squeeze past you?” or saying sorry when someone else has actually bumped into them (figure that one out!).

8. British People Love the Royal Family: true and false

While Americans are obsessed with the royal family and all of their events, celebrations, weddings, births, and more, it’s actually not a true stereotype that British people love the royal family.

Yes, some people in the UK do love the royal family and follow them – they’re the ones you’ll see on the news talking about how they woke up at 3am to stand outside the hospital for the royal family birth or wedding, etc.

But many people are either indifferent about the royal family or at odds with the idea of having a monarchy.

Many younger Brits err towards the side of a monarchy being an outdated concept, and so it’s important to know that a large percentage of the British population do not have the same feelings about the monarchy as foreigners do.

It is a much more complicated and complex issue within the UK than many people understand on the surface.

9. They Like Talking about the Weather: true

One of the most true stereotypes about British people that I’ve ever heard is that they like to talk about the weather.

Well, maybe they don’t “like” it as much as they just do it – constantly!

The British weather changes so often – it is an island nation after all, and it’s a fantastic small talk topic of conversation, whether you’re trying to fill empty space in a conversation in the office, around extended family members, or with acquaintances

When I grew up in Florida, we almost never talked about the weather because it was so predictable. How many times can you say “it’s hot”?

But in the UK, when it could be hailing and cold in the morning and then full sunshine and hot in the afternoon, where one day it could feel like Spring and the immediate next day could feel like the depths of winter, where the rain comes and goes off-and-on at its own will and with no predictability, the weather is on everyone’s minds!

10. Brits are Reserved: true

As a whole, British people are stereotyped as being relatively quiet and reserved, and while this doesn’t hold true for certain cultures within the UK (the Scots tend to be much more talkative in my experience!), overall I would say this one is true when you compare it to Americans.

I’ve experienced that British people take longer to “open up” to others and like to keep themselves to themselves more.

They’re not necessarily the culture to knock on your door to welcome you to the neighborhood when you’ve first moved in – in fact, they would probably feel like they’re intruding.

I am not even that loud of a person, but I definitely get told that within the context of British culture, I come across as very loud at times, which goes to show just how reserved they can be as a society.

It’s that “stiff upper lip” that they’re so famous for.

11. British People Love to Queue: true

Again, maybe this one isn’t true in the sense that Brits don’t LOVE queuing, but man do they do it with great dedication.

Waiting your turn and forming an orderly queue/line is something the Brits are great at – heck, their tennis tournament, Wimbledon, is famous for the queue itself!

This isn’t a culture of pushing people out of the way to go Black Friday shopping.

There is definitely a culture in the UK of following the rules, which means lining up properly, whether that be for the bus, at Wimbledon, in the store, for an event, or anywhere else you might need to keep some order and prevent a rush!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- United Kingdom

- United States

- North America

- Latin America

- APAC (Australia, New Zealand and Asia Pacific)

- EMEA (Europe, Middle East and Africa)

Cultural British Stereotypes and How to Deal With Them

All over the globe people tend to have similar preconceived notions of what a standard British civilian looks, walks, talks and acts like. Some of the British stereotypes, I can confirm, are quite accurate whilst others can be pretty hilarious but also a little unfair.

Every culture has their own stereotypes and of course it’s unfair to judge and categorise everyone from Britain into certain categories, but it’s also quite nice to prepare yourself for how a typical British person behaves so that you know not only what you’re in for, but also how to respectfully behave when you’re surrounded by the British culture.

Here’s a guide to the most common cultural British stereotypes, both fact and fiction.

Stiff upper lip

This term comes from the idea that an emotional or upset person has a quivering upper lip, so a stiff upper lip refers to the concept that the British are quite reserved and keep their emotions and feelings to themselves. Whilst the times are changing and this is becoming less and less true, compared to other cultures around the world, the British are still quite closed off emotionally and it really takes a lot of time, trust and hard work to be able to break down those walls.

Sarcastic humour

Irony and heavy sarcasm are the bedrock of British humour. Being able to tell when your British friends are being sarcastic from when they’re trying to have a serious conversation takes some serious skill and even after years of living in the U.K, it’s likely that you’ll still often get it wrong. At least there are a lot of hilarious and sometimes awkward conversations to be had in the meantime though…

The British are undoubtedly the best queuers in the world. They have it nailed down to a respectable art form and few things offend Brits more than seeing someone jump the queue they’re standing in. It’s all about fairness and waiting your turn, which leads us on to…

Whilst the Brits are not quite as chivalrous as some of their European neighbours, their polite manners are indeed very likeable. You will rarely be kept waiting for an ‘excuse me’, ‘sorry’, ‘please’ or ‘thank you’.

Want to move to the UK? Find out how much it could cost to move your belongings with our guide on international shipping costs .

Hate of confrontation

British folk spend a lot of time and effort avoiding any possible awkward or confronting moments in social situations, most probably due to the previous point on manners and politeness. Because of this, they have mastered the art of small talk, something you’ll probably want to practice yourself.

Talking about the weather

It’s possibly the most spoken of topic in the country. If you ever find yourself in an awkward situation or have absolutely nothing to say, fear no more as you can get at least 10 minutes worth of quality conversation out of the current weather patterns. Keep an eye on the daily forecast for emergency conversations.

Apologising

The British have a need to apologise for absolutely any situation, saying ‘Sorry, I don’t smoke’ when asked for a lighter being a classic example. There are also so many different uses for the word ‘sorry’ in the U.K that apart from the obvious meaning of ‘I apologise’, sorry can also refer to “Hello”, “I didn’t hear you”, “I heard you but I’m annoyed at what you said”, or “You’re in my way”. It’s easy to get caught in the Sorry trap so be sure to keep a strong head and think before you start throwing the word around yourself, or you may slowly drive yourself mad or self-combust in a passive-aggressive fit.

Complaining

The Brits are often, somewhat unfairly, accused of being huge complainers. When you set aside weather and football conversations, complaining is actually down to a minimum and in fact, like every other culture in the world, there are equally as many enthusiastic and positive Brits as there are negative and whiney ones. It completely depends on the person that you talk to.

The drinking culture in the U.K is huge and most social occasions are centred around alcoholic beverages. The Brits are absolutely spoilt for choice when it comes to pubs and with the long winters and wet summers, it’s easy to see why this is such a popular pastime.

Britain is the nation of tea drinkers. In many workplaces it’s considered outrageous to get up and make yourself a cup of tea without offering a round to everyone within earreach. Tea drinking is serious business in Britain and it won’t take long for you to work out how to brew the perfect cuppa with just the right amount of water to milk ratio.

We’ve all seen an article, news story, film or documentary about football hooligans in the U.K before and probably vowed to never attend a football match again. Whilst this is a very popular sport in Britain, these days it’s mostly quite tame, although you do still get the outsiders who are always ready to cause some trouble. If you’re not going to the games, keep on top of your football stats if you want to earn some bonus conversation points down and the pub.

Terrible food and wine

The traditional British dishes of fish and chips or bangers and mash don’t really stand out as some of the best in the way of culinary sophistication. However, the British food scene is picking up spectacularly and London is really leading the charge. In fact, 2 London restaurants made the Top 10 in the world list in 2014, so there is definitely big progress in the foodie world. When it comes to wine, however, you’ll just have to rely on the imports.

The posh British life

When many foreigners picture a British person, they see posh accents, large manor homes, top hats and tails. “Why golly gosh, this is absolute utter incongruous pish posh my dear boy!” That’s only for the very wealthy aristocrats who live in West London and were raised by nannies. Wait, is that just more stereotyping?

So are the stereotypes true?

Stereotype is the perfect word for it. Yes, you’ll come across a lot of these personalities and probably quite often, but there are also so many people who don’t fit into these categories, just like everywhere in the world.

It’s not that these are the majority, but those Brits who fit the stereotypes tend to be the extreme ones and thus they’ll be the ones that you’ll probably notice most.

How do you deal with stereotypes?

If you can’t beat them, join them. If you want to move to the UK , it will take some adjustment no matter where you’re from. Embrace the cultural differences and make the most of them.

You don’t need to be judgmental, that’s the beauty of being a true expat – you are lucky enough to be able to completely immerse yourself in a new culture, learn everything about it and take the best bits and apply them to your own way of living. Plus, it’s always nice to pick up some polite British manners and let’s be honest, we could all learn to queue a little better.

When all else fails, discuss the weather over a hot cup of tea.

Enjoy this post? Take a look at our stereotypes showdown: London vs New York for more harmless banter.

Written by:

Latest blog articles.

- The 9 Countries With the Best Healthcare 2023

- The 7 Best Podcasts for Expats

- Which Countries Have Restrictions on Unvaccinated People?

Latest Research Articles

- Watch Brits Try to Label a Map of Europe

- The Hipster Index

- Where to Move When You're Young and Broke

Written and reviewed by:

Moving made simple.

Tell us where you're moving to and compare prices from up to 6 trusted removal companies to see how much you could save today.

- United Kingdom

- 14 British Stereotypes That We...

British Stereotypes That We Won't Even Try to Deny

It would be unreasonable to assume that every Australian drinks Fosters, all Americans love baseball, and that the Japanese only eat sushi . Yet when it comes to the British, people all over the world have preconceived ideas about us all loving Marmite and living in London . Let’s set the record straight, once and for all.

Did you know you can now travel with Culture Trip? Join one of our UK trips to experience the country with a small group of like-minded travellers, led by our Local Insiders.

We love tea…

The Aussies may have introduced the flat white to us, but it’s no use trying to talk a Brit out of a good ol’ cuppa. We love it. Not the herbal fancy stuff – we want builder’s brew, the colour of he-man . Moreover, nobody is critiqued on how many cups of tea they drink in this nation. One, three, nine; the only thing we will judge is which brand of tea you drink and the order in which you put the milk.

Drinking in a pub…

Not that different from relaxing with a cuppa, really. It’s familiar, and quite often just around the corner. Whether it’s inside among the dark wood panelling and soggy carpets, or outside in the beer garden on a summer’s day, the pub is like a communal living room in your neighbourhood. As such, there’s no appropriate time to assert your attendance at the pub: lunchtime for beer, 4pm for wine or a 9.30 night cap – you don’t need a reason. It all adds up, though…

We drink an awful lot…

…Of alcohol – that is. When we’re not drinking tea, we’re drinking alcohol. Beer, wine, cider, spirits, alcoholic ice lollies – it all goes down a treat. And of course, we don’t need an excuse: brunch is now bottomless, the weekend starts on Wednesday, and there are gin distillers popping up all over the country faster than mushrooms after rainfall. It’s part of our DNA, something we do especially well when travelling abroad. And no, we’re not planning on giving up any time soon.

Nothing to talk about besides the weather…

Well, come on, you’ve seen our weather: cloudy with a chance of grey, 70% chance of showers, top of 17 with some potential late sun. The weather changes its mind more often than Trump, so forgive us for wanting to have a moan about it because, quite frankly, it can get expensive buying a new umbrella every month.

Getting burnt to a crisp on holiday…

And because of the aforementioned lack of glorious sunshine, it’s no wonder so many Brits burn so easily. It’s glaringly obvious when someone’s been on holiday and neglected to believe that factor 50 was invented for a reason. We’ll say you’re glowing when, in fact, we mean ‘You’re as red as the tomato in my caprese’. #spotthebritabroad

We LOVE to queue…

We do it very well. Take, for instance, the Wimbledon queue: people camp out for days on grass for tickets that essentially allow them to sit and watch more grass. One theory for the origin of this ‘civilized behaviour’ stems from the world wars and the rationing of everyday goods; queuing effectively meant everyone could get a share of the limited supplies. It thus formed notions of decency, and now we just queue for anything. The bank, the post office, the bar – heck, we’ll even join a long queue just in the hopes that there’s something good at the front.

We apologise profusely…

If you haven’t heard a Brit say the word ‘sorry’ at least five times in the past two hours, you’d better check your location settings. Some say it’s because we feel responsible for our terrible weather and food, so we feel the need to apologise for everything: being early, being late, sneezing, asking for the bill, making eye contact during sex, having sex, Nigel Farage.

We are too polite…

All this apologising is because we’re polite and don’t like to cause a scene or complain (except about the weather , but we apologise for that). We tend to swallow bad service at a restaurant, eat stale sandwiches, and even take the blame when it’s not our fault (Nigel Farage) . Give us two glasses of wine, however, and you’ll know exactly how we feel.

We secretly judge you behind your back…

Politeness is a culturally defined marvel, and thus what is considered good manners in one culture can actually sometimes come across as quite rude or rather odd in another . To cut a long story short, we’re passive aggressive: ‘I’d love for you to come around for dinner!’ ( I’d rather eat an uncooked pizza in my bathroom than have you over ); ‘I only have a few small comments’ ( Rewrite the entire thing, you idiot ).

We hate confrontation…

We’ve spent all this time being polite to you, apologising profusely, then secretly having a bitch about you behind your back – so please, please don’t confront us about it, okay? This is why we’ve mastered the art of small talk, to avoid awkward social situations. Now sod off and let us eat our curry chips in peace.

Our battered sausages and mushy peas…

We might be a ‘posh’ bunch, but our refined status falls short at the dishes most synonymous with Britain: marmite on toast, chips with curry sauce, Spam and stodgy rice puddings. Not precisely what one would call ‘culinary sophistication’ – however, the reality is, we actually do eat other foods (well, hangover days excluded) and London now has 66 Michelin-starred restaurants . And , wasn’t it us who invented afternoon tea and the sandwich ? Ah-hem.

We all have charming English accents, like the Queen…

This one we will deny. Have you watched Geordie Shore ?

And speaking of Queen Lizzy…

We love her. In an age of over-sharing, she maintains her haughty habit of under-sharing, and we still don’t know what she’s really thinking, 65 years on. She has a sound sense of style, still rides her horses despite her 91 years and, come on, what’s Christmas Day without a right royal broadcast?

We’re slightly confused about our citizenship and nationality

We might yield a strong affection for the monarch, but in Britain there are several types of citizenship and some nationals who are not citizens at all. Confused? So are we. But essentially there are six different types : British citizens, British subjects, British overseas citizens, British overseas territories citizens, British overseas nationals, or British protected persons. Hmmm. We think it’s time for a cup of tea. Did you know you can now travel with Culture Trip? Book now and join one of our premium small-group tours to discover the world like never before.

Culture Trips launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes places and communities so special.

Our immersive trips , led by Local Insiders, are once-in-a-lifetime experiences and an invitation to travel the world with like-minded explorers. Our Travel Experts are on hand to help you make perfect memories. All our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.?>

All our travel guides are curated by the Culture Trip team working in tandem with local experts. From unique experiences to essential tips on how to make the most of your future travels, we’ve got you covered.

Guides & Tips

Sleeper trains worth experiencing on your travels.

The Best Setjetting Trips You Can Take with Culture Trip

See & Do

A quintessential english countryside experience at bovey castle.

Swapping Rush Hour for the Ultimate Slow Commute

Places to Stay

The yorkshire dales, but make it luxury.

Top TRIPS by Culture Trip in the UK

Film & TV

Aaand action explore the uk's top film spots with google street view.

The Best Group Tours in the UK

How to Make the Most of Your Holiday Time if You're in the UK

Creating Gotham in Liverpool and Glasgow for ‘The Batman’

The Best Private Trips You Can Book With Your Family

Why Where I Stay is Becoming a More Important Part of My Travel Experience

Culture trip spring sale, save up to $1,100 on our unique small-group trips limited spots..

- Post ID: 1433619

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

- Skip to navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

- Membership Directory

- Partnership

General Questions:

- Find a Program Explore Programs ISEP Exchange ISEP Direct Summer Programs January Programs Intern Abroad Identity Abroad Programs by Region Top Cities Africa & The Middle East Asia Australia, New Zealand & Oceania Europe Latin America United States & Canada Programs by Field of Study Animal Science & Agriculture Architecture & Design Business and Marketing Communication, Media, and Film Studies Criminal Justice & Criminology Education and Teaching Practicum Engineering and Computer Science Environmental Science, Environmental Studies, and Sustainability French Language, Culture, and Literature Programs History Language Programs Nursing, Health Sciences and Pre-Health Professions Political Science, International Relations and Global Studies Psychology & Sociology Science Spanish Strategic Communications and Journalism Theatre, Music, Dance, & Fine Art Start a Search Connect with ISEP

- How It Works Student Stories We're Here to Help ISEP's Promise Steps to Get Started How to Apply How to Find the Right Program Program Types & Deadlines ISEP Scholarships Become an ISEP Digital Ambassador! Before You Go While You Are Abroad Diversity, Inclusion & Accessibility Abroad Health, Safety, and Risk Management Returning Home Join the ISEP Alumni Association Start a Search Connect with ISEP

- Contact Us Meet Our Team Emergency Contact Send Us a Message Travel Advisories General Questions: Business Hours: M-F 9:00am - 5:00pm EST Phone: +1 (703) 504-9960 Fax: +1 (703) 243-8070 Email: [email protected] Membership Directory Join ISEP Partnership Alumni Faculty Donate About ISEP

American and British Stereotypes: A Cultural Exchange

Contributed by.

Blue is an ISEP Voices blogger from Marshall University, in West Virginia, who studied abroad at University of Chester, in the United Kingdom.

Connect with ISEP

Interested in studying abroad? Sign up to learn more!

ISEP student Blue C. is a part of ISEP Voices Spring 2016. She is an exercise science major from Marshall University, and is currently studying abroad at the University of Chester in the United Kingdom.

Coming into a new country from the United States was quite the culture shock. I came to Great Britain: a country that speaks the same language and just drinks much more tea, right? Wrong. My first week here was just a blur of back and forth questions between myself and my new British friends. I never realized how many difference there are in our cultures until I spent some time here. What was even more shocking was the fact that they thought things about the United States that I would never have expected. I’ve been asked three different times if high school is like High School Musical! I decided to ask around and find out what students from these countries really want to know about one another. I ended up sending five questions out to university students from each country to find out what exactly we think of each other.

Questions from American students to British students:

On average how much tea do you actually drink a week.

- British student 1: I hate tea.

- British student 2: 8-12 cups per week.

- British student 3: I drink zero cups of tea a week.

- British student 4: Maybe three a week when I’m at uni, but maybe three a day at home.

- British student 5: I reckon I drink around five cups of either tea or coffee a day, it just depends on how I feel.

What exactly is a “Full English Breakfast?”

- British student 1: Baked beans, sausages, fried tomatoes and mushrooms, toast, hash browns and bacon

- British student 2: Tea, bacon, egg, sausage, tomato, beans, toast, pudding and hash browns

- British student 3: A breakfast which is full of different foods. It usually begins with cereals or fresh fruits, but the main part of the breakfast is the bacon and eggs. I have sausages and beans with it. Other people have grilled tomatoes and mushrooms as well.

- British student 4: Fried eggs, bacon, sausages, bakes beans, toast, fried mushrooms, black pudding and fried tomatoes.

- British student 5: A “full English” is a “breakfast,” but more seen as a lunch meal. It mainly consists of pork sausage, bacon, fried or scrambled egg, pudding, hash browns (like a small potato cake with onion in it), fried bread or toast, baked beans and a large mug of either coffee or tea.

What three words do you think of when you hear “America?”

- British student 1: Blonde, L.A. and summer

- British student 2: Camp, patriotic and McDonald’s

- British student 3: Patriotic, big and Obama

- British student 4: Guns, Christians and the military

- British student 5: Loud, big and patriotic

From what you know, what is something you like about America that you wish was in Great Britain?

- British student 1: I would love for the U.K. to have the freedom that universities in America have. There’s more opportunities to study different subjects there.

- British student 2: More Reese’s.

- British student 3: How they have structure in education sport. From what I’ve learned and seen in the movies, it seems that young people don’t learn to take part in sport, but love it and have a passion for it.

- British student 4: The environment, like the national parks, mountains and variety of landscapes.

- British student 5: I don’t know how to answer this one. I’d probably say the food, just because I love food.

Without Google, How many states make up the United States and what is the capital of the nation?

- British student 1: 50? Washington, D.C.

- British student 2: 52 States. Washington, D.C.

- British student 3: I think it’s 53 and I’m 100% certain that it’s Washington, D.C.

- British student 4: 50 and it’s Washington, D.C.

- British student 5: Bloody hell, I’ll say 50 states all together. I really don’t know many, only the obvious ones. Lists 21 states. The national capital is Washington, D.C.

Questions from British students to American students:

Why do americans like british accents so much.

- American student 1: Americans like hearing a different accent than their own from someone who speaks the same language. In addition, English accents seem proper and sophisticated.

- American student 2: To us, they are different. They are regal, elegant and just downright pleasing to the ear. We enjoy things that are foreign to us.

- American student 3: It’s different from us, but we can still understand what is being said, whereas other accents are sometimes hard to understand. Different, but familiar.

- American student 4: They just sound so classy.

- American student 5: Americans are into anything foreign really.

Why are Americans so patriotic?

- American student 1: Americans pronounced patriotism comes from the “Cinderella Story” of the United States hard-fought independence that led to America’s climb to becoming a world superpower.

- American student 2: We have the belief that we are the greatest country in the world, and that’s something I think everyone should feel about the nation they are from.

- American student 3: We are a major melting pot country. Rather than history or a common language that unite us, we are united by freedom which is what it means to be “American.”

- American student 4: I don’t know, I’m not that patriotic.

- American student 5: Americans are patriotic because other Americans are patriotic. It’s more of a mob mentality kind of thing.

What three words do you think of when you hear “Great Britain?”

- American student 1: Colonialism, tradition and decline.

- American student 2: Queen, Doctor Who and Buckingham.

- American student 3: England, futbol and Winston Churchill.

- American student 4: British Flag, Shakespeare and rain.

- American student 5: Tea, football and BBC.

From what you know, what is something you like about Great Britain that you wish was in America?

- American student 1: The parliamentary system that elects parties, not candidates.

- American student 2: I enjoy the more-than-two-party political system they have. I do not wish for quite as many parties as they have, but I would enjoy seeing more than two major parties in the US.

- American student 3: I wish soccer was more popular in America like it is in Britain.

- American student 4: Universal health care and the relaxed attitude towards alcohol.

- American student 5: Premier League.

Without Google, what nations make up Great Britain?

- American student 1: England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales

- American student 2: Scotland, Ireland, Wales and England

- American student 3: Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England

- American student 4: England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, but that might be the United Kingdom. I’m not positive.

- American student 5: Ireland, England and Scotland?

A huge thank you to everyone who participated in this. I really enjoyed everyone’s answers and learned some new things myself!

Like this Story? Also like us on Facebook.

- Cultural Differences

- United Kingdom

- United States

Get Blog Updates

Email is required

Related Blog Posts

- blog Marginalized Bodies Abroad Podcast ISEP staff members on the IDEA Task Force discuss the successes and challenges that they faced during their time abroad.

- blog Six Reasons Why You Should Volunteer Virtually in Barcelona Hear from three ISEP alums why you should consider volunteering virtually in Barcelona this summer!

- blog Stages of Culture Shock: How to Beat the Study Abroad Slump Around halfway through the semester, I felt like I had fallen into a routine. I felt uninspired, and easily annoyed by little things. Here are some strategies I used to lift myself of this funk.

- Search for a Program Search for a Program

- How to Find the Right Program How to Find the Right Program

- Scholarships & Finances Scholarships & Finances

- Study Abroad Study Abroad

- Intern Abroad Intern Abroad

- Program Types & Deadlines Program Types & Deadlines

- Planning Your Experience Planning Your Experience

- Before You Go Before You Go

- While You Are Abroad While You Are Abroad

- Health, Safety, and Risk Management Health, Safety, and Risk Management

- Returning Home Returning Home

- Alumni Alumni

- ISEP Staff ISEP Staff

- Member Directory Member Directory

- Join ISEP Join ISEP

- Partner with ISEP Partner with ISEP

- Careers Careers

- Annual Report Annual Report

- About ISEP About ISEP

- For info email [email protected]

- Phone: 1-703-504-9960

- Address: 1655 N. Fort Myer Drive, Suite 400, Arlington, Virginia, U.S. 22209

- © ISEP 2024

- Privacy Policy

GoUni Tips - UK Lifestyle

- UK Lifestyle

✨ A Guide to British Stereotypes ✨

A stereotype is a generalisation of the perceived tendencies or characteristics of certain people. They are often used to make jokes. We want to share some of the most common stereotypes recognised by Brits, so you can understand the jokes they make. 😆

While many stereotypes have some truth in them (eg "Americans love guns" - there are more guns per person in USA than in any other country in the world); others are completely baseless (eg "Women can't drive well" - women actually have significantly fewer road accidents than men).

Regardless, most Brits understand that, while stereotypes can be fun to joke about, they should not be taken seriously. We certainly do not endorse the usage of any of these in any other context than a joke. ☝🏼

National Stereotypes

Americans 🇺🇸 tend to be stereotyped as brash, fat and overoptimistic. Jokes are also made about Americans' love of guns and cars. 🔫🚘😏

Germans 🇩🇪 are stereotyped as very serious and efficient. As Henning Wehn (a German comedian) jokes: "The difference is Germans like to laugh once the work is done!"

The French 🇫🇷 are stereotyped as suave, romantic, and snobbish. Jokes are also made about France surrendering to the Nazis in World War II.

There isn't much of a stereotype for Italians 🇮🇹 in the UK, but they are known everywhere for using this gesture...

Australians 🇦🇺 are stereotyped as easy-going beer-drinkers, always out on the beach, playing sport or having a BBQ. Sometimes jokes are made about Aussies being criminals, as many of the first white settlers in Australia were criminals exiled from Britain.

While Brits 🇬🇧 would accept the stereotype of drinking a lot of tea, most of them wouldn't recognise the stereotype of being posh - which mostly comes from the Queen, Jane Austen novels and rich British actors.

There is also a British stereotype of having a "stiff upper lip", which means you don't show if you are upset or angry. Most Brits would agree with this perception. One more stereotype that is famous in Britain is that Brits love to queue up, and hate people who try to skip the queue. 😡

Londoners are stereotyped as posh and antisocial. It is often joked that no one likes to look at or talk to anyone in London. 😆

Northerners ( Northern English ) 🏴 are stereotyped as chatty, simplistic and nationalist.

Scots 🏴 are stereotyped as being very unhealthy: drinking a lot, eating deep-fried Mars bars and having a low life expectancy. They are also stereotyped as hating the English.

The Irish 🇮🇪 are stereotyped as being heavy drinkers, and friendly.

Wales 🏴 has a lot of sheep, so people joke that the Welsh love sheep. 😂

Many Polish and other Eastern European citizens have migrated to the UK since they joined the EU in 2004. They are often stereotyped as being hard workers, or doing construction and home-improvement works cheaply.

There isn't really a stereotype for Thais 🇹🇭 , but jokes are sometimes made about ladyboys in Thailand.

Leave A Comment

Connect with us.

We'll Keep you updated with alerts, news and help where you need it

Watch GoUni Previews

GoUni EP.25 - รีวิวเรียนที่เมืองแมนยู แสลงอังกฤษแปลกๆ | ft. NCG Manchester

งานแฟร์เรียนต่อ GoUni Language & High School Fair 2024

Gouni valentine's day บอกต่อคอร์สเรียนภาษากับ bell english london, โค้งสุดท้าย เรียนต่อปริญญาโทประเทศอังกฤษ รอบ sep 2023 & jan 2024 พบกันวัน application day, go study abroad fair, 7 ยูท็อป ไม่ต้องสอบ ielts ก็เรียนต่อป.โทที่ uk ได้, 6 เหตุผลที่ใครๆ ก็อยากไปเรียนต่ออเมริกา, บอกต่อวิธีเขียน statement of purpose ยังไงให้ปัง ได้ใจมหาลัย, ทุนเรียนต่อกฎหมายที่อังกฤษ university of east anglia, ✨ ร้านชาไข่มุกในอังกฤษที่ลองแล้วจะหายคิดถึงบ้าน ✨, ✨ uk student discounts for clothing ✨, ✨ 9 tips for starting at university ✨, ✨ uk mobile networks that offer student discounts ✨, รวม 30 คำย่อภาษาอังกฤษที่สายแชททุกคนควรรู้, รู้หรือไม่ มหา’ลัยอังกฤษมีระบบแบ่งบ้านเหมือนแฮร์รี่ พอตเตอร์เลย, ✨ unfolding cultures abroad, so you won’t be shocked ✨, ✨ britain introduces “fake news” to educational ✨.

GOUNI EP19 - รีวิวเรียนภาษาที่เมือง Cambridge คลาสสิคแบบอังกฤษสุด!! | Feat. Bell Cambridge

LET’S GET STARTED

If you are looking to study in the UK there is no better time to start applying than now. And with GoUni we will be there to helpyou every step of the way.

FREE CONSULTATION

© GoUni Limited | Development by Ecce.

UK Edition Change

- UK Politics

- News Videos

- Paris 2024 Olympics

- Rugby Union

- Sport Videos

- John Rentoul

- Mary Dejevsky

- Andrew Grice

- Sean O’Grady

- Photography

- Theatre & Dance

- Culture Videos

- Fitness & Wellbeing

- Food & Drink

- Health & Families

- Royal Family

- Electric Vehicles

- Car Insurance Deals

- Lifestyle Videos

- UK Hotel Reviews

- News & Advice

- Simon Calder

- Australia & New Zealand

- South America

- C. America & Caribbean

- Middle East

- Politics Explained

- News Analysis

- Today’s Edition

- Home & Garden

- Broadband deals

- Fashion & Beauty

- Travel & Outdoors

- Sports & Fitness

- Sustainable Living

- Climate Videos

- Solar Panels

- Behind The Headlines

- On The Ground

- Decomplicated

- You Ask The Questions

- Binge Watch

- Travel Smart

- Watch on your TV

- Crosswords & Puzzles

- Most Commented

- Newsletters

- Ask Me Anything

- Virtual Events

- Betting Sites

- Online Casinos

- Wine Offers

Thank you for registering

Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in

7 stereotypes about British people that everyone believes

Don't believe everything you hear - our average rainfall is lower than european rainy season average. , article bookmarked.

Find your bookmarks in your Independent Premium section, under my profile

Get the free Morning Headlines email for news from our reporters across the world

Sign up to our free morning headlines email, thanks for signing up to the morning headlines email.

Do you love tea, enjoy polite queuing and take an umbrella everywhere you go? Probably, but that's not the point.

Many Brits experience frustration at the number of stereotypes that people enforce on them. And just like most stereotypes they are usually harmless – and often untrue.

- How to spot a psychopath according to a psychopath

- The most disturbing truths about marriage

- 10 skills that are hard to learn but pay off forever

In response to a question posted on Quora , Britons have listed the most common and unfounded examples:

1. They all have a ‘British accent’

“There is no such thing as a British Accent but there are accents and dialects. People from the South sound completely different from people from the North.”

2. They love the Royal Family

“There are quite a few Brits who either outright dislike the concept (if not he family itself), or don't particularly care for it. They bring in a lot of tourist money and occasionally there's a day off for something or the other so tolerance and tempered appreciation wins out.”

The 10 worst areas of Britain for earning the living wage

3. They have terrible food

“England is a fantastic place to eat with a hugely varied cuisine from all around the world.

“I'm not sure how it stacks up compared to other cities when it comes to expensive gourmet meals in five star restaurants and I honestly don't care.

“I do know that for someone on a reasonable budget it's fantastic. It also has the best Indian food on the planet (better than India).”

4. All British people are English

“Great Britain is the name of an Island containing three countries. The inhabitants of these countries are very different.

“Most [‘British’] stereotypes seem to refer to the English.”

5. British people are rude

“Particularly in London. Unless you stand on the left hand side of the escalator on the Tube; then you're in for a lot of rudeness.”

6. They are permanently wet

“While there is no 'dry' season, the average rainfall during our rainy months is in fact lower than the European rainy season average. Greece has as much rain as us in its rainy season.”

7. Everyone has a charming accent like the English folk on the TV

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

New to The Independent?

Or if you would prefer:

Want an ad-free experience?

Hi {{indy.fullName}}

- My Independent Premium

- Account details

- Help centre

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 8 British Stereotypes and Why They Are (Mostly) Inaccurate

As with any other country, we Brits are subject to our fair share of cultural stereotypes.

While, to a greater or lesser degree, there’s an element of truth in some of them, you’ll soon discover that many are comically far from the truth! That’s not to say that we deny responsibility; many of the stereotypes about the British are of our own making, and it gets worse if you get into region-specific stereotypes, like the range of things said about the Scottish and Welsh. Still, it’s certainly the case that visitors can come to Britain with somewhat inaccurate expectations of what they’ll find here . In this article, we’re going to debunk some of the myths and help you get to know us a little better.

1. We’re all best mates with Prince William

Mention to someone from another country that you’re from Britain, and one of the responses you may encounter is “Do you know Prince William?” And in that question, you might just as well substitute the heir to the British throne with any other member of the Royal Family. Judging by the volume of Royal memorabilia sold to tourists each year, it would seem that our Royals are one of the things that non-Brits most love about us. Even those of us who live in Britain are fascinated by them, particularly since William and Kate have come to the fore as the monarchy’s 21st century ambassadors. While it’s very gratifying that our monarchy generates so much interest from overseas, Britain is a country with a population of 63.23 million people. Funnily enough, we’re not all personally acquainted with the Royals, even though many of us will happily dig out our anecdote about “the day we saw the Queen” or about our brief encounter with one of the more minor members of the Royal Family. But, while we may be on first name terms with them, they’re sadly not on first name terms with us.

2. We all live in a gloriously idealised London

In the imaginations of many outside the UK, our capital city is the place in which all British people reside – doubtless in residences with views of the Houses of Parliament or Buckingham Palace. At a push, non-Brits may have heard of other major cities such as Oxford or Edinburgh, and maybe Birmingham, but that’s often as far as non-Brit knowledge extends. This isn’t helped by the fact that so many major films are set in London: Notting Hill , Love Actually , Bridget Jones , to name but a few. And all these films present idealised versions of London that have those who’ve never been imagining that it’s idyllically snowy in the winter and sunny in the summer, that transport is by the iconic red double decker buses and black cabs (the latter at least is partly true), and that all London living is based in the very heart of the city, surrounded by its most famous landmarks. In movies, those who don’t live in London live in picture-perfect villages surrounded by unspoilt countryside, in quaint little cottages with log burners, and roses growing around the door. The reality, of course, sadly doesn’t quite live up to this romantic ideal. Those who live in London live mostly in its sprawling (and often depressing) suburbs, with astronomical house prices making living in central London an impossible dream for everyone but the world’s richest. More often than not, London is grey, polluted and rainy, and getting from A to B is a gargantuan task that involves negotiating the grimy, crowded London Underground, known affectionately as “The Tube”. Don’t get us wrong – London is fantastic. But it’s not how it’s portrayed on the big screen. What’s more, most Brits don’t live in London. They live in cities, towns and villages dotted around the country, just like people do in any other country. Though there is much to admire about the majority of British settlements, and many have long and interesting histories that are still in evidence in their buildings and monuments, they’re probably not how most non-Brits imagine them. These days our high streets look very similar from one town to the next, because they’re all dominated by chains of the same shops and supermarkets, and modern housing estates all look the same because they’re mostly built by the same property developers. Some people do enjoy the idealised, Hollywood version of Britain – but it’s generally the people who have lots of money. That’s not to say, however, that Britain for everyday people lacks charm; far from it.

3. We all talk like a Cockney or an aristocrat