- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Broken Windows Theory

How Environment Impacts Behavior

Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/RachaelGreenProfilePicture1-a3b8368ef3bb47ccbac92c5cc088e24d.jpg)

Akeem Marsh, MD, is a board-certified child, adolescent, and adult psychiatrist who has dedicated his career to working with medically underserved communities.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/akeemmarsh_1000-d247c981705a46aba45acff9939ff8b0.jpg)

Verywell / Dennis Madamba

Origins and Explanation

- Application

- Impact on Behavior

- Positive Environments

The broken windows theory was proposed by James Q. Wilson and George Kelling in 1982, arguing that there was a connection between a person’s physical environment and their likelihood of committing a crime.

The theory has been a major influence on modern policing strategies and guided later research in urban sociology and behavioral psychology . But it’s also come under increasing scrutiny and some critics have argued that its application in policing and other contexts has done more harm than good.

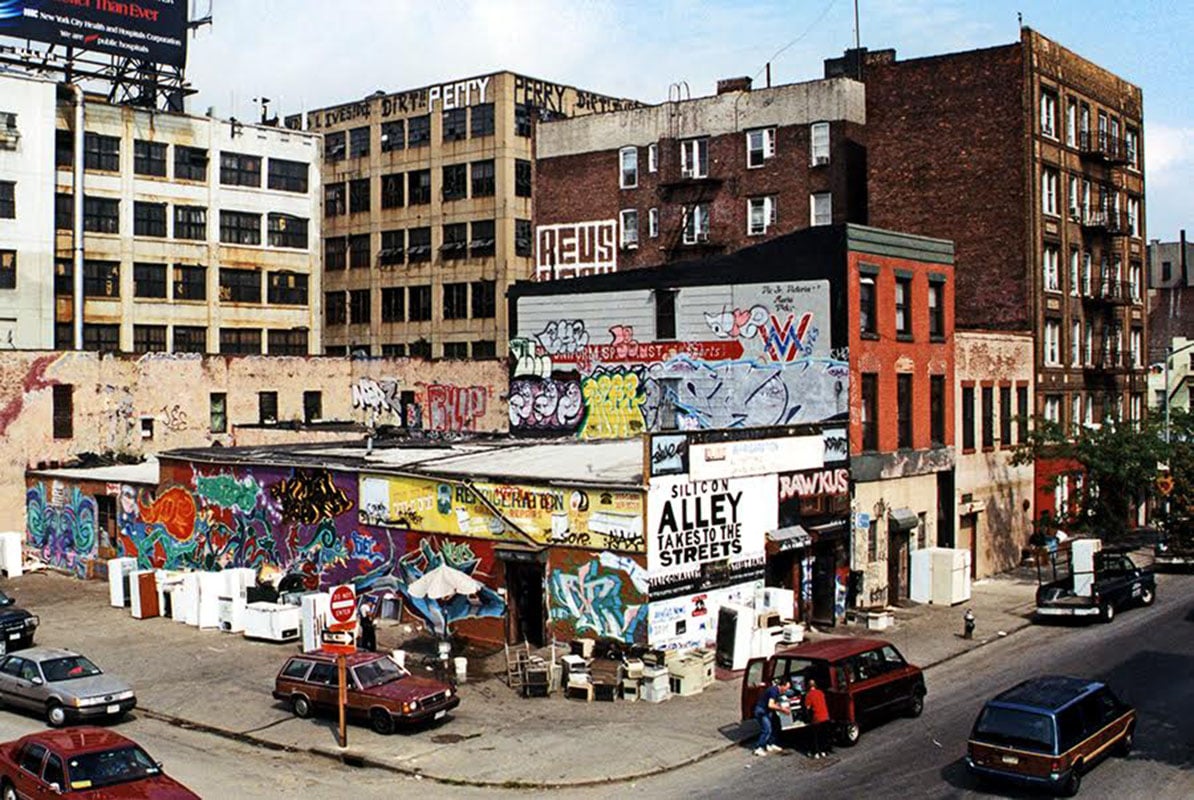

The theory is named after an analogy used to explain it. If a window in a building is broken and remains unrepaired for too long, the rest of the windows in that building will eventually be broken, too. According to Wilson and Kelling, that’s because the unrepaired window acts as a signal to people in that neighborhood that they can break windows without fear of consequence because nobody cares enough to stop it or fix it. Eventually, Wilson and Kelling argued, more serious crimes like robbery and violence will flourish.

The idea is that physical signs of neglect and deterioration encourage criminal behavior because they act as a signal that this is a place where disorder is allowed to persist. If no one cares enough to pick up the litter on the sidewalk or repair and reuse abandoned buildings, maybe they won’t care enough to call the police when they see a drug deal or a burglary either.

How Is the Broken Windows Theory Applied?

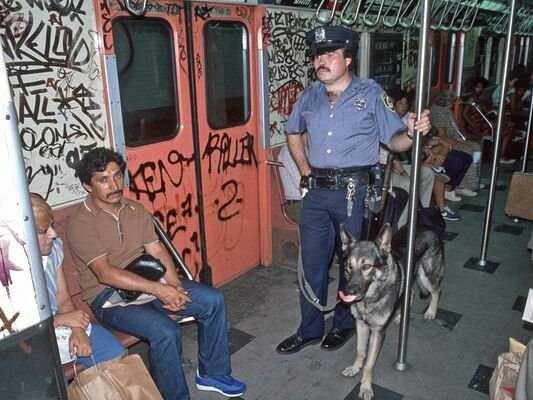

The theory sparked a wave of “broken windows” or “zero tolerance” policing where law enforcement began cracking down on nonviolent behaviors like loitering, graffiti, or panhandling. By ramping up arrests and citations for perceived disorderly behavior and removing physical signs of disorder from the neighborhood, police hope to create a more orderly environment that discourages more serious crime.

The broken windows theory has been used outside of policing, as well, including in the workplace and in schools. Using a similar zero tolerance approach that disciplines students or employees for minor violations is thought to create more orderly environments that foster learning and productivity .

“By discouraging small acts of misconduct, such as tardiness, minor rule violations, or unprofessional conduct, employers seek to promote a culture of accountability, professionalism, and high performance,” said David Tzall Psy.D., a licensed forensic psychologist and Deputy Director for the Health and Wellness Unit of the NYPD.

Criticism of the Broken Window Theory

While the idea that one broken window leads to many sounds plausible, later research on the topic failed to find a connection. “The theory oversimplifies the causes of crime by focusing primarily on visible signs of disorder,” Tzall said. “It neglects underlying social and economic factors, such as poverty, unemployment, and lack of education, which are known to be important contributors to criminal behavior.”

When researchers account for those underlying factors, the connection between disordered environments and crime rates disappears.

In a report published in 2016, the NYPD itself found that its “quality-of-life” policing—another term for broken windows policing—had no impact on the city’s crime rate. Between 2010 and 2015, the number of “quality-of-life” summons issued by the NYPD for things like open containers, public urination, and riding bicycles on the sidewalk dropped by about 33%.

While the broken windows theory would theorize that serious crimes would spike when the police stopped cracking down on those minor offenses, violent crimes and property crimes actually decreased during that same time period.

“Policing based on broken windows theory has never been shown to work,” said Kimberly Vered Shashoua, LCSW , a therapist who works with marginalized teens and young adults. “Criminalizing unhoused people, low socioeconomic status households, and others who create this type of ‘crime’ doesn't get to the root of the problem,”

Not only have policing efforts that focus on things like graffiti or panhandling failed to have any impact on violent crime, they have often been used to target marginalized communities. “The theory's implementation can lead to biased policing practices as law enforcement officers can concentrate their efforts on low-income neighborhoods or communities predominantly populated by minority groups,” Tzall said.

That biased policing happens, in part, because there’s no objective measure of disordered environments so there’s a lot of room for implicit bias and discrimination to influence decision-making about which neighborhoods to target in crackdowns.

Studies show that neighborhoods where residents are predominantly Black or Latino are perceived as more disorderly and prone to crime than neighborhoods where residents are mostly white, even when police-recorded crime rates and physical signs of physical deterioration in the environment were the same.

Moreover, many of the behaviors that are used by police and researchers as signs of disorder are influenced by racial and class bias . Drinking and hanging out are both legal activities that are viewed as orderly when they happen in private spaces like a home or bar, for example. But those who socialize and drink in parks or on stoops outside their building are viewed as disorderly and charged with loitering and public drunkenness.

The Impact of Physical Environment on Behavior

While the broken windows theory and its application are flawed, the underlying idea that our physical environment can influence our behavior does hold some water. On one hand, “the physical environment conveys social norms that influence our behavior,” Tzall explained. “When we observe others adhering to certain norms in a particular space, we tend to adjust our own behavior to align with them.”

If a person sees litter on the street, they might be more likely to litter themselves, for example. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll make the leap from littering to robbery or violent assault. Moreover, litter can often be a sign that there aren’t enough public trashcans available on the streets for people to throw away food wrappers and other waste while they’re out. In that scenario, installing more trashcans would do far more to reduce litter than increasing the number of citations for littering.

“The design and layout of spaces can also signal specific expectations and guide our actions,” Tzall explained. In the litter example, then, the addition of more trashcans could also act as an environmental cue to encourage throwing trash away rather than littering.

How to Create Positive Environments to Foster Safety, Health, and Well-Being

Ultimately, reducing crime requires addressing the root causes of poverty and social inequality that lead to crime. But taking care of public spaces and neighborhoods to keep them clean and enjoyable can still have a positive impact on the communities who live in and use them.

“Positive environments provide opportunities for meaningful interactions and collaboration among community members,” Tzall said. “Access to green spaces, recreational facilities, mental health resources, and community services contribute to physical, mental, and emotional health,” said Tzall.

By creating more positive environments, we can encourage healthier lifestyle choices—like adding protected bike lanes to encourage people to ride bikes—and prosocial behavior —like adding basketball courts in parks to encourage people to meet and play a game with their neighbors.

At the individual level, Tzall suggests people “can initiate or participate in community projects, volunteer for local organizations, support inclusive initiatives, engage in dialogue with neighbors, and collaborate with local authorities or community leaders.” Create positive environments by taking the initiative to pick up litter when you see it, participate in tree planting initiatives, collaborate with your neighbors to establish a community garden, or volunteer with a local organization to advocate for better public spaces and resources.

Wilson JQ and Kelling GL. Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety . The Atlantic Monthly. 1982.

Harcourt B, Ludwig J. Broken windows: new evidence from new york city and a five-city social experiment . University of Chicago Law Review. 2006;73(1).

Peters M, Eure P. An Analysis of Quality-of-Life Summonses, Quality-of-Life Misdemeanor Arrests, and Felony Crime in New York City, 2010-2015 . New York City Department of Investigation Office of the Inspector General for the NYPD; 2016.

Sampson RJ. Disparity and diversity in the contemporary city: social (Dis)order revisited . The British Journal of Sociology. 2009;60(1):1-31. Doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01211.x

By Rachael Green Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

- Privacy Policy

Broken Windows Theory in Workplace Management & Business Strategy

Applying the Broken Windows theory in workplace management and operations management can benefit businesses, especially in minimizing costs associated with undesirable employee behaviors. This business application is extendable to other aspects of operations, such as stakeholder management and various administrative activities. The Broken Windows theory is a criminological framework for understanding human behavioral effects of the physical environment, especially with regard to policing communities for disorderly conduct, delinquency, and crime. Even though this theory is criminological, it has diverse possible applications in the business world. The emphasis on human behavior makes the theory applicable in settings that require managing or influencing people’s behaviors. Business managers can use the Broken Windows theory to strategically enhance workforce performance through the reduction of undesirable employee behavior, and to encourage positive customer behavior toward the business organization and its products. Policing the enterprise in this way can reduce barriers to operational effectiveness and business success.

There are various practical applications of the Broken Windows policing theory in non-business situations. Nonetheless, companies stand to benefit from the cost-efficiencies linked to the theory’s application in strategies for social control. Business leaders must aim to eliminate “broken windows” to create an image of management effectiveness, systematization, efficiency, quality, care, and round-the-clock surveillance.

Overview of the Broken Windows Theory

Although originally introduced in 1982, the Broken Windows theory is popularly known for its application in New York City’s police operations under the leadership of Mayor Giuliani. The main idea is that a neglected and disorderly environment encourages further neglect and disorder, which makes policing and public administration more difficult. The resulting condition leads to higher probabilities of criminal activity. The “broken windows” symbolize the manifestations of neglect and disorder, such as broken windowpanes, graffiti, and unattended trash piles. The theory asserts that restoring order in the visual physical environment reduces misdemeanor and crime. Overt monitoring of the physical environment, such as through surveillance cameras, also contributes to the reduction of disorder and crime.

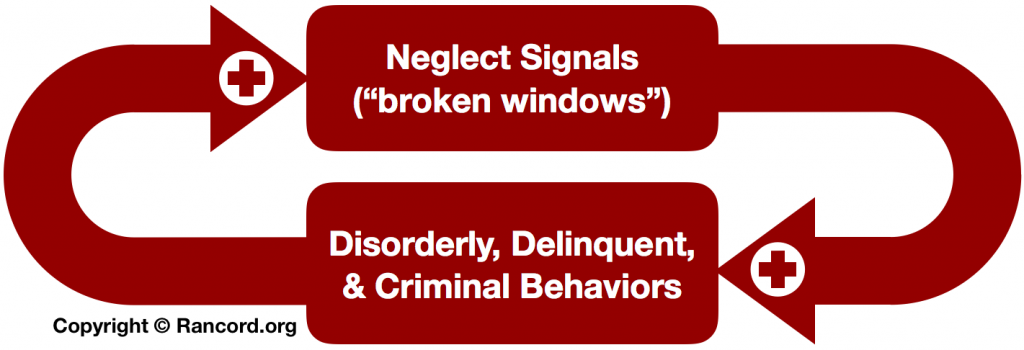

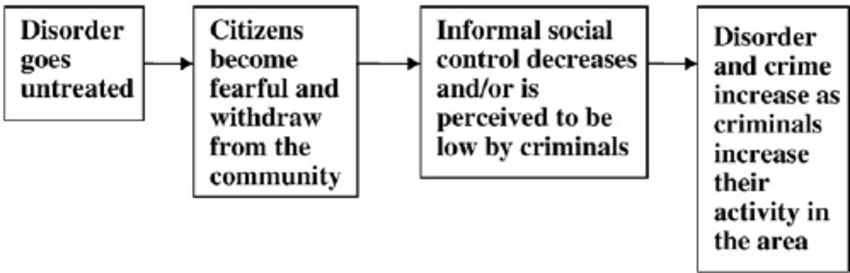

The relationship between the physical environment and human behavior is depicted in the following positive feedback loop diagram that represents the theoretical principles and concept of broken windows policing:

This diagram is a simple representation of the flow of positive reinforcement between the neglect indicators or signals and people’s behaviors in the environment in question. Administrative and public neglect signals, such as broken windowpanes, could increase the likelihood of people’s disorderly, delinquent, and criminal behaviors. In turn, these behaviors lead to further neglect signals, such as through vandalism. Thus, the scenario is that of a positive feedback loop. Theoretical explanations for this cycle of reinforcement include visual cues, such as broken windows, which may indicate the neglect of and lack of consequences on disorder and crime. Social conformism is another factor: People have the tendency to conform to what they think others are doing, such as neglecting disorder or vandalizing seemingly neglected buildings.

Broken Windows Policing in Workplace Administration in Enterprises

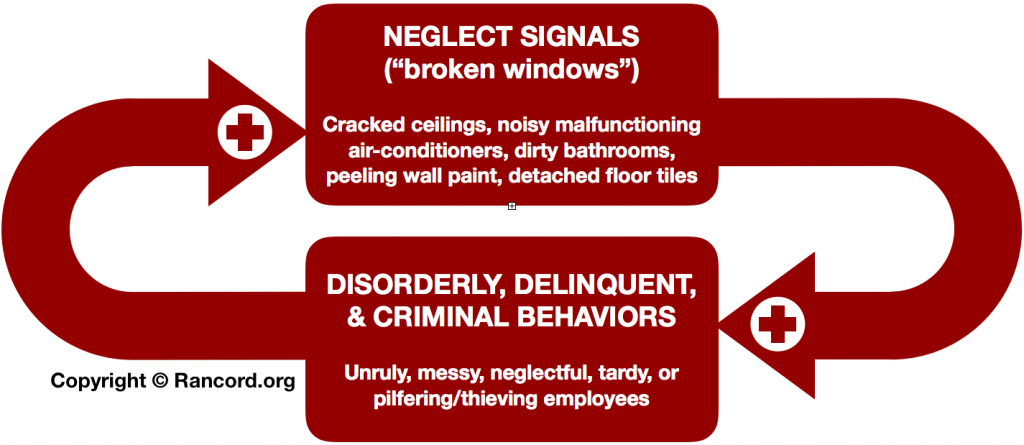

Workplaces involve employees, whose behaviors determine organizational effectiveness. This aspect of business organizations typically requires human resource management programs to optimize workers’ performance by influencing their behaviors. The effects of the physical characteristics of the workplace are a basic consideration in administering that involves a form of broken windows policing. This is where the Broken Windows theory relates to business organizations, especially in managing the workplace environment. In the context of enterprises and their administrative efforts, the following diagram expands the simple feedback loop illustrated in the previous diagram of the Broken Windows theory:

In enterprises, the physical environment involves the space where employees perform their jobs. According to the Broken Windows theory, the characteristics of this space influence workers’ individual and group behaviors. Signs of neglect and disorder can lead to further neglect and disorder among workers. In relation to the diagram, examples of “broken windows” or neglect signals in the business management and strategy context include disorderly office files and folders, disorganized desks, rusty doors, moldy ceilings, and peeling paint.

A direct application of the Broken Windows theory in business management is through the removal or reduction of neglect signals. For example, company managers can use workplace maintenance programs to immediately repair damage or to replace furniture and fixtures when needed. Damaged and malfunctioning spaces, furniture, and equipment are the workplace’s “broken windows” or neglect signals, based on the Broken Windows policing theory. Implementing a suitable form of broken windows policing, companies and their managers can expect lower likelihood of employees engaging in disorderly, deviant, or criminal behaviors in the workplace. The presence of even one “broken window” can have a significant effect on employees’ engagement in workplace violence, delinquency, or criminal activity, and could potentially lead to a “broken business.”

Extending the social control application of the Broken Windows theory, business managers can encourage desirable behaviors among employees by enhancing the physical characteristics of the workplace, especially those characteristics that the employees readily observe. These characteristics are the visual cues that influence workers’ perceptions and corresponding behaviors toward the company. For example, to achieve higher rates of exchange of innovative ideas among employees, business administrators can minimize “broken windows” or neglect signals, such as visual obstructions and other physical barriers to communication between offices, desks, or cubicles. These barriers lead to the perception that the company neglects employees’ psychosocial needs.

Integrating the Broken Windows theory into business policies can strengthen companies’ financial performance. For example, including the theory in human resource management policies and strategies can enhance the outcomes of employee training programs and leadership development. This “broken windows policing” of the enterprise environment should consider the design of training venues and the characteristics of materials and equipment used. Orderliness, cleanliness, and an overall streamlined layout and design of workplaces influence employees to adopt behaviors that comply with business rules. Business managers can expect compliant employee behavior through the use of clean and properly functioning materials and equipment. This business strategy of using the Broken Windows theory for higher business performance via human resource management requires the reduction or elimination of “broken windows,” which include improperly constructed venues, inefficient layouts, disorganized materials, rusty and malfunctioning equipment, and dusty floors and seats.

Broken Windows Theory in Managing Customer Behaviors

Customer behavior management is another business area where the Broken Windows theory is applicable. This area involves strategies and administrative activities that encourage customers to maintain behaviors that are desirable to company. For example, retailers aim to reduce customers’ misdemeanor and increase their purchase rates. Managers may apply the Broken Windows theory through strategies and tactics that increase customers’ likelihood of maintaining orderly behavior while in the company’s premises. These strategies and tactics include maintaining a neat and spotless store, which creates the perception that the business does not neglect its premises and that the company provides high-quality products. As a form of social control, this “broken windows policing” of customers makes them have a favorable perception about the company, and deter them from littering or vandalizing the place. They are motivated to keep orderly behavior. As a case example, businesses such as McDonald’s restaurants (intentionally or unintentionally) apply the Broken Windows theory in keeping high standards of sanitation and orderliness. A neat and clean restaurant creates an image of crew effectiveness.

Other Business Applications of the Broken Windows Theory

Aside from HR management and customer behavior management, the Broken Windows theory is applicable in other administrative areas of businesses. For example, Business managers could implement the theory in spaces where they transact or interact with suppliers and third-party service providers. In retailers like Walmart , the condition of warehouses or delivery bays influences supplier personnel’s interactions with the retailer’s employees. An orderly warehouse helps establish an image of systematic processes, which motivate suppliers’ representatives to be systematic, as well. Similarly, companies may apply the Broken Windows theory in physical environments where they interact with business partners. These environments include meeting rooms, where the presence or absence of “broken windows” influence negotiators’ perceptions and the outcomes of business negotiations and agreements. Applying the Broken Windows theory in business strategic management affects branding and corporate image. For example, “broken windows policing” of marketing venues, such as in trade shows, can optimize marketing effectiveness and, consequently, business performance.

- Bratton, W. J. (2016). Broken Windows is Not Broken: The NYPD Response to the Inspector General’s Report on Quality-of-Life Enforcement . City of New York.

- Jenkins, M. J. (2016). Police support for community problem-solving and broken windows policing. American Journal of Criminal Justice , 41 (2), 220-235.

- Kelling, G. L., & Coles, C. M. (1997). Fixing broken windows: Restoring order and reducing crime in our communities . Simon and Schuster.

- Kotabe, H. P., Kardan, O., & Berman, M. G. (2016). The order of disorder: Deconstructing visual disorder and its effect on rule-breaking . Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145 (12), 1713-1727.

- Mahoney, T. A., & Deckop, J. R. (1986). Evolution of concept and practice in personnel administration/human resource management (PA/HRM). Journal of Management , 12 (2), 223-241.

- Martinko, M. J., Douglas, S. C., & Harvey, P. (2006). Understanding and Managing Workplace Aggression. Organizational Dynamics, 35 (2), 117-130.

- Morris, J. A., & Feldman, D. C. (1997). Managing emotions in the workplace. Journal of Managerial Issues , 9 (3), 257.

- Muniz, A. (2012). Disorderly community partners and broken windows policing. Ethnography , 13 (3), 330-351.

- Priluck Grossman, R. (1998). Developing and managing effective consumer relationships. Journal of Product & Brand Management , 7 (1), 27-40.

- Ren, L., Zhao, J. S., & He, N. P. (2017). Broken Windows Theory and Citizen Engagement in Crime Prevention. Justice Quarterly , 1-30.

- Reynolds, K. L., & Harris, L. C. (2006). Deviant customer behavior: An exploration of frontline employee tactics. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice , 14 (2), 95-111.

- Salin, D. (2015). Risk factors of workplace bullying for men and women: The role of the psychosocial and physical work environment. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology , 56 (1), 69-77.

- Sandelands, L., Glynn, M. A., & Larson Jr., J. R. (1991). Control theory and social behavior in the workplace. Human Relations , 44 (10), 1107-1130.

- Suliman, A. M., & Abdulla, M. H. (2005). Towards a high-performance workplace: managing corporate climate and conflict. Management Decision , 43 (5), 720-733.

- Timm, S., Gray, W. A., Curtis, T., & Chung, S. S. E. (2018). Designing for health: How the physical environment plays a role in workplace wellness. American Journal of Health Promotion, 32 (6), 1468-1473.

- Trice, H. M. (1989). Social control in the workplace. Psyccritiques , 34 (1), 56-58.

- Vischer, J. C., & Wifi, M. (2017). The effect of workplace design on quality of life at work. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research (pp. 387-400). Springer, Cham.

- Weisburd, D., Hinkle, J. C., Braga, A. A., & Wooditch, A. (2015). Understanding the mechanisms underlying broken windows policing: The need for evaluation evidence. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency , 52 (4), 589-608.

- Welsh, B. C., Braga, A. A., & Bruinsma, G. J. (2015). Reimagining broken windows: From theory to policy. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency , 52 (4), 447-463.

- Zhou, X., Liao, J. Q., Liu, Y., & Liao, S. (2017). Leader impression management and employee voice behavior: Trust and suspicion as mediators. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal , 45 (11), 1843-1854.

Our web site does not collect personally identifiable information. See Our Privacy Policy .

Broken Windows Theory

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

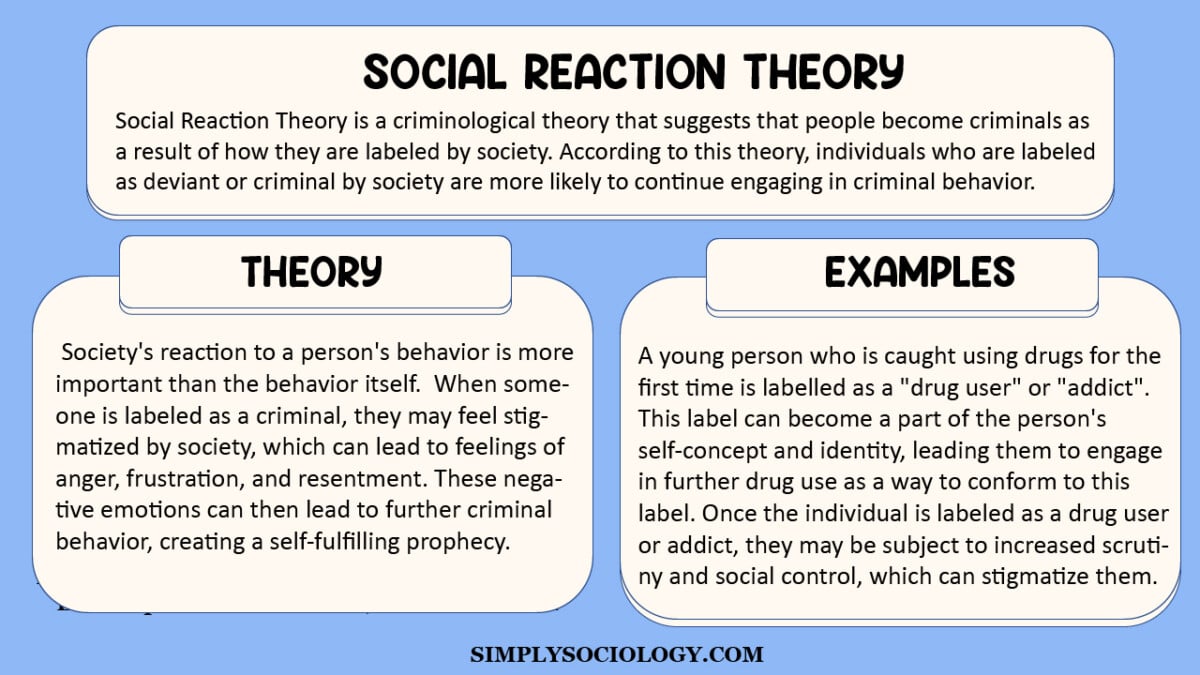

The broken windows theory states that visible signs of disorder and misbehavior in an environment encourage further disorder and misbehavior, leading to serious crimes. The principle was developed to explain the decay of neighborhoods, but it is often applied to work and educational environments.

- What Is the Broken Windows Theory?

- Do Broken Windows Policies Work?

The broken windows theory, defined in 1982 by social scientists James Wilson and George Kelling, drawing on earlier research by Stanford University psychologist Philip Zimbardo, argues that no matter how rich or poor a neighborhood, one broken window would soon lead to many more windows being broken: “One unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing.” Disorder increases levels of fear among citizens, which leads them to withdraw from the community and decrease participation in informal social control.

The broken windows are a metaphor for any visible sign of disorder in an environment that goes untended. This may include small crimes, acts of vandalism, drunken or disorderly conduct, etc. Being forced to confront minor problems can heavily influence how people feel about their environment, particularly their sense of safety.

With the help of small civic organizations, lower-income Chicago residents have created over 800 community gardens and urban farms out of burnt buildings and vacant lots. Now, instead of having trouble finding fresh produce, these neighborhoods have become go-to food destinations. This example of the broken windows theory benefits the people by lowering temperatures in overheated cities, increasing socialization, reducing stress , and teaching children about nature.

George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson popularized the broken windows theory in an article published in the March 1982 issue of The Atlantic . They asserted that vandalism and smaller crimes would normalize larger crimes (although this hypothesis has not been fully supported by subsequent research). They also remarked on how signs of disorder (e.g., a broken window) stirred up feelings of fear in residents and harmed the safety of the neighborhood as a whole.

The broken windows theory was put forth at a time when crime rates were soaring, and it often spurred politicians to advocate policies for increasing policing of petty crimes—fare evasion, public drinking, or graffiti—as a way to prevent, and decrease, major crimes including violence. The theory was notably implemented and popularized by New York City mayor Rudolf Giuliani and his police commissioner, William Bratton. In research reported in 2000, Kelling claimed that broken-windows policing had prevented over 60,000 violent crimes between 1989 and 1998 in New York City, though critics of the theory disagreed.

Although the “Broken Windows” article is one of the most cited in the history of criminology , Kelling contends that it has often been misapplied. The implementation soon escalated to “zero tolerance” policing policies, especially in minority communities. It also led to controversial practices such as “stop and frisk” and an increase in police misconduct complaints.

Most important, research indicates that criminal activity was declining on its own, for a number of demographic and socio-economic reasons, and so credit for the shift could not be firmly attributed to broken-windows policing policies. Experts point out that there is “no support for a simple first-order disorder-crime relationship,” contends Columbia law professor Bernard E. Harcourt. The causes of misbehavior are varied and complex.

The effectiveness of this approach depends on how it is implemented. In 2016, Dr. Charles Branas led an initiative to repair abandoned properties and transform vacant lots into community parks in high-crime neighborhoods in Philadelphia, which subsequently saw a 39% reduction in gun violence. By building “palaces for the people” with these safe and sustainable solutions, neighborhoods can be lifted up, and crime can be reduced.

When a neighborhood, even a poor one, is well-tended and welcoming, its residents have a greater sense of safety. Building and maintaining social infrastructure—such as public libraries, parks and other green spaces, and active retail corridors—can be a more sustainable option and improve the daily lives of the people who live there.

According to the broken windows theory, disorder (symbolized by a broken window) leads to fear and the potential for increased and more severe crime. Unfortunately, this concept has been misapplied, leading to aggressive and zero-tolerance policing. These policing strategies tend to focus on an increased police presence in troubled communities (especially those with minorities and lower-income residents) and stricter punishments for minor infractions (e.g., marijuana use).

Zero-tolerance policing metes out predetermined consequences regardless of the severity or context of a crime. Zero-tolerance policies can be harmful in an academic setting, as vulnerable youth (particularly those from minority ethnic/racial backgrounds) find themselves trapped in the School-to-Prison Pipeline for committing minor infractions.

Aggressive policing practices can sour relationships between police and the community. However, problem-oriented policing—which identifies the specific problems or “broken windows” in a neighborhood and then comes up with proactive responses—can help reduce crime. This evidence-based policing strategy has been shown to be effective.

We question the contribution made by criminology to the practicalities of policing and suggest that police officers would be better off acquainting themselves with psychology.

In reports of police use of force, officers and minority citizens are often portrayed as natural enemies. Here is what we know and some suggestions for a helpful approach.

Once we've mastered self-rationalization, our "inner weasels" can silence our consciences.

Part 2: A high murder rate. A cry for help. And I was walking down the street…

Pace yourself. It all comes down to this month, and it doesn't. It's ongoing, uphill work.

Lying is always bad except when it's good. Recursion suggests how to find exceptions to moral rules.

Defund the police is the rallying cry you hear as people feel more resources need to help residents deal with mental health issues. In one city, therapists respond with the police.

We live in a time of political chaos, terrorism, civil unrest, and economic unpredictability. We must build resilient communities if we are to survive and thrive. Here's how.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Fixing Broken Windows: Cultivating a Strong Organizational Culture

- September 18, 2023

Ms. Fahima AlHamaty

Healthcare business & operations manager.

In the field of criminology, the Broken Window Theory posits that visible signs of crime, disruptive behavior, and societal disorder can trigger an environment in urban settings that breeds further delinquency and chaos, including more serious criminal activities.

In simpler terms, the Broken Window Theory suggests that if a window in a building remains broken and goes unrepaired for an extended period, it’s likely that other windows in the same building will follow suit. This leads to a prevailing perception that crime is rampant in the neighborhood, largely because building owners seem to accept this state of affairs.

However, it’s worth noting that the “broken windows” concept extends beyond urban areas. Torbin Rick, in his 2016 article “Broken Organizational Culture,” points out that the same syndrome can afflict companies as well. Some organizations tend to overlook seemingly minor workplace issues because managers and business owners believe that addressing them is a futile endeavor. Michael Levine, in his book “Broken Windows, Broken Business,” presents compelling evidence that both significant and seemingly trivial hitches in business often stem from the neglect of small details.

As Torbin Rick aptly puts it, ”

Examples of these “broken windows” within companies encompass absenteeism, information silos, covert terminations, employee resignations without notice, ineffective human resources management, employee burnout, an unjust or disconnected organizational culture, and a lack of employee engagement. Michael Levine adds that sometimes, the most detrimental “broken windows” are the underperforming or incompetent employees within a business.

When customers experience mistreatment from poorly-trained employees or when employees have to work alongside someone who is not up to the task, they often conclude that the organization doesn’t value or respect them. As Leigh Buchanan emphasizes in her HBR article “Sweat the Small Stuff,” this perceived lack of respect from either customers or employees arises from the organization’s failure to “repair” or “replace” these broken employees, which can sometimes include middle management and executives.

To mend these broken windows and cultivate a thriving organizational culture, it’s crucial for leaders, managers, and employees to recognize the pivotal role they play in shaping the everyday culture of the organization. As Torbin Rick aptly states, “Organizational culture is fragile—it requires constant care and attention.” In today’s competitive business landscape, surviving without addressing internal “vandalism” becomes increasingly challenging.

Organizations that choose to disregard the early signs of problematic behavior within the workplace are likely to face severe consequences in the long run. They may struggle to stay ahead of their competitors, and unchecked, seemingly minor issues can drive employees away in search of environments with zero-to-little tolerance for poor behavior and subpar performance.

Fahima AlHamaty, a dedicated wife and mother of two boys, boasts over two decades of extensive executive healthcare management experience, spanning diverse domains like business, strategy, change management, and more. Holding an MBA in International Healthcare Management, she’s now pursuing a DBA at Universidad Catolica San Antonio de Murcia (UCAM) with a research focus on Strategic Human Resources. Additionally, she’s engaging in an Executive Education Online Programme in Innovation at INSEAD, all while nurturing her passions for reading, traveling, cooking, and volunteering.

Your Westford Uni Online Journey Begins Here…

Ready to get started talk to us today.

Our team of expert advisors will support you with each of your queries and guide you, every step of the way. Study anytime, anywhere and graduate with an accredited degree.

Our Courses

- News & Blogs

- Privacy Policy

- Why Westford Uni Online

- Online Blended Learning

- Westford Uni Online Partners

- Westford Toastmasters Club

© 2024 Westford Uni Online. All Rights Reserved

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 December 2020

An empirical application of “broken windows” and related theories in healthcare: examining disorder, patient safety, staff outcomes, and collective efficacy in hospitals

- Louise A. Ellis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6902-4578 1 ,

- Kate Churruca 1 ,

- Yvonne Tran 1 ,

- Janet C. Long 1 ,

- Chiara Pomare 1 &

- Jeffrey Braithwaite 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 20 , Article number: 1123 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

9702 Accesses

6 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

Broken windows theory (BWT) proposes that visible signs of crime, disorder and anti-social behaviour – however minor – lead to further levels of crime, disorder and anti-social behaviour. While we acknowledge divisive and controversial policy developments that were based on BWT, theories of neighbourhood disorder have recently been proposed to have utility in healthcare, emphasising the potential negative effects of disorder on staff and patients, as well as the potential role of collective efficacy in mediating its effects. The aim of this study was to empirically examine the relationship between disorder, collective efficacy and outcome measures in hospital settings. We additionally sought to develop and validate a survey instrument for assessing BWT in hospital settings.

Cross-sectional survey of clinical and non-clinical staff from four major hospitals in Australia. The survey included the Disorder and Collective Efficacy Survey (DaCEs) (developed for the present study) and outcome measures: job satisfaction, burnout, and patient safety. Construct validity was evaluated by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and reliability was assessed by internal consistency. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to test a hypothesised model between disorder and patient safety and staff outcomes.

The present study found that both social and physical disorder were positively related to burnout, and negatively related to job satisfaction and patient safety. Further, we found support for the hypothesis that the relationship from social disorder to outcomes (burnout, job satisfaction, patient safety) was mediated by collective efficacy (social cohesion, willingness to intervene).

Conclusions

As one of the first studies to empirically test theories of neighbourhood disorder in healthcare, we found that a positive, orderly, productive culture is likely to lead to wellbeing for staff and the delivery of safer care for patients.

Peer Review reports

A long tradition exists in criminology and social-psychology research on the concept of neighbourhood disorder and in what ways disorder relates to anti-social behaviour and poor outcomes [ 1 ] . Interest in neighbourhood disorder is readily apparent in Broken Window Theory (BWT) [ 2 ], as well as in alternative perspectives of disorder involving shared expectation and cohesion—more broadly known as collective efficacy [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]—that are consistent with social disorganisation theory. The current study draws from these various theories and insights into neighbourhood disorder and applies them to hospital settings. At this point, we must make clear our intentions in applying neighbourhood disorder theories to healthcare. It is perilous to expect theories of neighbourhood disorder can be perfectly replicable in an organisational setting, nor do we consider that all elements of the theories are applicable to hospital settings (such as the concept of fear) [ 6 ] . We particularly reject the flawed ramifications of these theories that saw victimisation and blame attributed to individual neighbourhood members. However, here, we consider that concepts from neighbourhood studies may have considerable promise to shed new light on the relationships between the physical and social environments of hospitals on the one hand, and the health, wellbeing and behaviour of staff and patients, on the other [ 7 ] . We begin by reviewing the history and evolution of these theories before considering their application to healthcare.

Broken windows: a theory of disorder in neighbourhoods

Broken windows theory (BWT), as a social-psychological theory of urban decline, was originally developed almost 40 years ago by Wilson and Kelling [ 2 ]. Proponents of this theory argue that both physical disorder (e.g., broken windows, graffiti, litter) and social disorder (e.g., vandalism, antisocial activities) provide important environmental cues to the kinds of negative actions that are normalised and tolerated in an area, fuelling further incivility and more serious crime. For example, signs of disorder can signal potential safety issues to residents of a neighbourhood, leading to their withdrawal from public spaces, and thereby a reduction in informal social control, further perpetuating the effects of disorder [ 2 ].

Defining disorder

Although debates have occurred in the literature as to what counts as disorder, it has usually been defined as representing “minor violations of social norms” ([ 8 ] p4923). Some researchers have made a distinction between physical and social disorder, with physical disorder relating to the overall appearance of an area and social disorder directly involving people [ 9 ]. Thinking about disorder in this way, neighbourhoods with high levels of physical disorder were defined as: noisy, dirty, and run-down; buildings are in disrepair or abandoned; and vandalism and graffiti are common [ 10 ]. On the other hand, signs of social disorder in neighbourhoods may include the presence of people hanging out on the streets, drinking, or taking drugs [ 10 ]. Researchers highlight the importance of measuring perceptions of physical and social disorder as separate factors [ 9 , 11 ] with recent studies finding differential impacts of the two types of disorder [ 12 ].

Rethinking disorder: the role of collective efficacy

The BWT originally proposed by Wilson and Kelling [ 2 ] suggested a causal relationship with disorder leading to crime, which had a significant bearing upon subsequent controversial policy developments, such as ‘zero-tolerance policing’ [ 13 ] and ‘stop-and-frisk’ programs [ 14 ]. Under this approach, police pay attention to every facet of the law, including minor offences, such as public drinking and vandalism, with the aim of preventing more serious crimes from occurring [ 13 ]. The level of support these policing strategies have received has been surprising, given that BWT has not received a commensurate amount of study to date, and the research on crime that does exist is equivocal [ 12 ]. In particular, there has been an ongoing debate in the academic literature over whether BWT posits a direct or indirect relationship between disorder and crime. Most prominently, Sampson and Raudenbush [ 4 ] reconsidered the claims of BWT and argued instead that physical and social disorder were not generally causal antecedents to more serious crimes. Consistent with social disorganisation theory [ 3 ], Sampson and Raudenbush [ 4 ] suggested that collective efficacy has a significant influence on criminality in neighbourhoods. They defined collective efficacy as “social cohesion among neighbours combined with their willingness to intervene on behalf of the common good” ([ 5 ] p918). Empirical results supported their conceptual ideas in that the positive relationship between disorder and crime was mediated by collective efficacy [ 4 ].

Other lines of research have found a direct association between disorder and crime even when controlling for collective efficacy (e.g., [ 15 ]). For example, Plank et al. [ 16 ] studied disorder and collective efficacy in a school setting. They found a robust association between both disorder and violence (i.e., crime) while controlling for collective efficacy. They concluded that “fixing broken windows and attending to the physical appearance of the school cannot alone guarantee productive teaching and learning, but ignoring them greatly increases the chances of a troubling downward spiral” ([ 16 ] p244). In summary, the results are mixed as to the extent that there is direct effect of disorder on crime or other poor outcomes, but the evidence clearly suggests that there is at least an indirect effect. The key problem is what people do with this information. There is no justification for blaming individuals or demonising groups or neighbourhoods for their behaviour. We do not in any way condone seriously erroneous and consequential victimisation of people or groups as a result of the application of BWT. But we do think this is an area worthy of study.

Applying broken windows theory to healthcare

Following recent interest in applying BWT to smaller, more circumscribed environments, such as workplaces [ 17 , 18 ], researchers have started to consider the application of BWT to healthcare settings [ 7 , 19 , 20 ]. There are several well-studied trends in health services research that support this application. Theories and studies of increasing popularity include: the normalisation of deviance [ 21 ], behavioural modelling in hand hygiene [ 22 ], hospital workplace violence [ 23 ], and the association between staff’s safe work practices and their perceiving their work area as cluttered and disorderly [ 24 ].

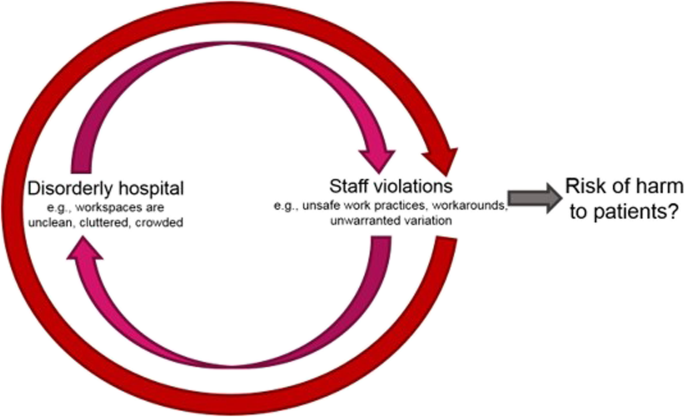

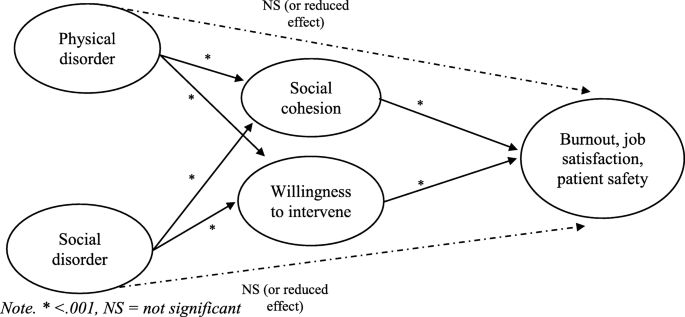

Disorder in hospitals may include negative deviations, trade-offs or workarounds that manifest continuously in complex, dynamic and time-pressured environments, which can contribute to poor staff outcomes [ 25 , 26 , 27 ]. While trade-offs and workarounds occur in every setting, and they may have many benefits including signalling productive flexibility and staff capacity for manoeuvring, they can also represent risk in healthcare. For example, some researchers have shown that small deviations such as violating recommended processes for use of local anaesthesia can be detrimental, potentially even leading to death [ 28 ]. In line with BWT logic, there is evidence to suggest that the physical hospital environment influences the health and wellbeing of staff and patients [ 29 ]. Similarly, evidence shows that social disorder (e.g., bullying, violence) can influence staff in healthcare organisations [ 23 , 30 ]. All of these examples highlight the potential negative perpetuating effects of disorder in healthcare organisations and how disorder may detrimentally affect patients, such as through poor patient safety outcomes (see Fig. 1 [ 7 ]). Despite the elevated interest in BWT, we could find no empirical study of disorder in hospitals, nor any examination of the role of collective efficacy on staff outcomes or patient safety.

Proposed model of disorder in hospitals Source: Churruca, Ellis et al., 2018 [ 7 ]

Aims of the present study

The primary purpose of the present study is to empirically examine the relationship between hospital disorder and three key outcomes: staff burnout, staff job satisfaction, and patient safety. We also sought to address the contention in the literature regarding the role of collective efficacy (defined here as social cohesion among hospital staff and their willingness to intervene to address problems) between hospital disorder and outcomes. The first aim was to develop a short but valid and reliable survey instrument for measuring physical disorder, social disorder, social cohesion and willingness to intervene in hospital settings. Based on previous research, physical and social disorder were kept as separate constructs. We then sought to test the following three research questions:

Is there a significant association between hospital disorder (physical disorder, social disorder) and staff outcomes (burnout, job satisfaction)?

Is there a significant association between hospital disorder (physical disorder, social disorder) and patient safety?

What is the function of “collective efficacy” (social cohesion, willingness to intervene) in hospitals? Specifically, does staff collective efficacy mediate the relationship between disorder and outcomes? Figure 2 demonstrates the simplified hypothesised mediation model.

Hypothesised mediation model

Participants and setting

The study employed a cross-sectional survey of staff from four major hospitals in Australia. All hospital sites were public hospitals in metropolitan areas with over 200 beds. The sites were selected based on the similarity in the types of services offered (e.g., emergency department, intensive care, surgical, medical, geriatric care) and that they were located within areas of varying relative socio-economic disadvantage [ 31 ]. All hospital staff were invited to participate in the study through an invitation sent to their work email address. The email included a link to an online version of the survey via Qualtrics [ 32 ].

Survey development

The Disorder and Collective Efficacy survey (DaCEs) for hospital staff was developed for the present study based on an extensive review of the BWT literature. An initial pool of items was formed to assess the hypothesised constructs of the DaCEs: Physical disorder (19 items), social disorder (13 items), and collective efficacy, represented by social cohesion (12 items) and willingness to intervene (10 items). Some of the items were adapted from existing scales [ 16 , 24 , 33 , 34 , 35 ], and others were purpose-developed by the research team (see Supplementary File 1 ). Items were modified to make them relevant to a hospital context. All items were answered on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). A panel of experts in healthcare ( n = 10; hospital staff and researchers) reviewed and provided feedback on the wording of items mapping onto each of the hypothesised constructs and checked for possible misinterpretations of questions, instructions and response format. Minor adjustments were made to the initial item pool (see Supplementary File 1 ). The aim was then to refine the item pool to produce a survey that would be short enough to be completed by busy hospital workers, but which has satisfactory psychometric properties.

Staff outcomes

The survey included existing validated scales to measure staff burnout and job satisfaction. Burnout was measured through a 10-item version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [ 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Two subscales of burnout—emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation—were used for the current survey as the third subscale, personal accomplishment, was deemed less relevant to nonclinical staff. Burnout items were answered on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). The job satisfaction section of the Job Diagnostic Survey (5 items) was selected to capture individual’s feelings about their job [ 39 ]. Job satisfaction items were answered on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Patient safety

An item taken from the Hospital Survey of Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC) was used as an indicator of patient safety [ 40 ]. This item is an outcome measure for patient safety that asks staff to provide an overall patient safety grade for their hospital (1 = excellent to 5 = failing).

Data analysis

Participants missing more than 10% of survey data were excluded. Remaining missing values were imputed using the Expectation Maximisation (EM) Algorithm within SPSS, version 25 [ 41 ]. Some items were then reversed coded so that higher item-response scores indicated a greater extent of job satisfaction, burnout, disorder, willingness to intervene, and patient safety (See Supplementary File 1 for individual recoded items). Frequency distributions were calculated to test whether items violated the assumption of univariate normality (i.e., skewness index ≥3, kurtosis index ≥10). As a number of the items were skewed (i.e., skewness index ≥3), the chi-square significance value was corrected for bias using the Bollen-Stine bootstrapping method [ 42 ] based on 1000 bootstrapped samples.

Items were evaluated psychometrically via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), using a two-stage process. First, to refine the initial item pool, four one-factor congeneric models (of physical disorder, social disorder, social cohesion and willingness to intervene items) were run using AMOS, version 25 [ 43 ]. Here, our analytic plan involved removing one item at a time from each model using the following strategy: (i) removing items with the lowest factor loadings while maintaining the theoretical content and meaning of the proposed construct; (ii) removing items as long as each construct contained at least four observed variables; and (iii) items were removed as long as the resulting model demonstrated an improved model fit [ 44 , 45 ]. Differences in model fit were assessed using the chi-square difference test [ 46 ]. Second, two two-factor models were used to assess the factor structure of items related to disorder (i.e., physical disorder, social disorder) and collective efficacy (i.e., social cohesion, willingness to intervene) using the reduced item sets. Each item was loaded on the one factor it purported to represent. Further item refinement was undertaken as required through inspection of factor loadings, standardised residuals and modification indices to reduce each scale to three or four items. Goodness-of-fit was assessed using the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEAs), and chi-square, with significance value supplemented by the Bollen-Stine bootstrap test. The TLI and CFI yield values ranging from zero to 1.00, with values greater than .90 and .95 being indicative of acceptable and excellent fit to the data [ 47 ]. For RMSEAs, values less than .05 indicate good fit, and values as high as .08 represent reasonable errors of approximation in the population [ 48 ]. For the Bollen-Stine test, non-significant values indicate that the proposed model is correct. Reliability of each of the subscales was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha (using SPSS, version 25) and composite reliability (using AMOS, version 25).

The hypothesised mediation model (Fig. 2 ) was assessed using structural equation modelling (SEM) in AMOS, version 25 [ 43 ]. First, we tested the direct effects from disorder (physical and social) to each outcome (burnout, job satisfaction, patient safety), followed by the indirect effect from disorder to outcomes, through collective efficacy (social cohesion, willingness to intervene). A parametric bootstrapping approach was used to test mediation. Under the bootstrapping approach, indirect effects are of interest and based on bootstrapped standard errors (with 1000 draws) [ 49 , 50 ]. Model fit was evaluated using CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and chi-square.

Descriptive statistics, distribution, reliability and confirmatory factor analysis

Participants were 415 staff from four hospitals in Australia. Once participants with more than 10% of survey data missing were excluded, the remaining sample was reduced to 340. Of the 340 participants, most were female (77.5%), worked as a nurse (34.2%), and had been working in the same hospital for three or more years (76.1%). The characteristics of the survey respondents are presented in Table 1 .

Descriptive statistics and data pertaining to assumptions of normality for all items are presented in Supplementary File 1 . The vast majority of the social disorder, social cohesion and willingness to intervene items demonstrated a skewness index greater than three, while only three items demonstrated a kurtosis index greater than 10 (SD7, SD10, SC6). As a result, Bollen-Stine bootstrapping was conducted in order to improve accuracy when assessing parameter estimates and fit indices.

To refine the initial item pool, first four one-factor congeneric models were run for items designed to measure physical disorder, social disorder, social cohesion and willingness to intervene. Based on an examination of modification indices and standardised factor loadings, items were removed one at a time, until the four strongest items remained. As shown in Table 2 , the reduced four-item constructs demonstrated much improved model fit statistics relative to the full models with all items. Chi-squared difference tests for all four constructs were significant, indicating that the reduced item constructs were significantly better models. The results of the chi-squared difference tests were: Physical disorder, (χ 2 difference = 139, df = 18, p < .001), social disorder (χ 2 difference = 680, df = 63, p < .001), social cohesion (χ 2 difference = 302, df = 52, p < .001), and willingness to intervene (χ 2 difference = 243, df = 33, p < .001).

Two two-factor models of disorder (physical disorder, social disorder) and collective efficacy (social cohesion, willingness to intervene) were then tested through CFA each using eight of their respective items. Each item was loaded on the one factor it purported to represent. Where required, further item refinement was undertaken through inspection of factor loadings, standardised residuals and modification indices. The two-factor model of disorder, including four physical disorder items and four social disorder items produced an adequate fit to the data, χ 2 (19) = 54.06, TLI = .96, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .08, though the Bollen-Stine bootstrap was significant ( p = .005). Inspection of the standardised factor loadings for items PD3 and SD3 suggested that their removal may improve model fit. The removal of these two items resulted in an improved model fit, χ2 (8) = 18.28, TLI = .979, CFI = .989, RMSEA = .062, and the Bollen-Stine bootstrap ( p = .057). The standardised factor loadings for the six items remaining ranged from .71 to .90. The correlation between physical disorder and social disorder was low, but significant ( r = .17, p = .007). Next, a two-factor model of collective efficacy consisting of four social cohesion items and four willingness to intervene items were tested. This model produced an excellent fit to the data, χ2 (19) = 25.36, TLI = .99, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .06, and the Bollen-Stine bootstrap was not significant ( p = .458). The standardised factor loadings for the six items ranged from .68 to .90, and the correlation between social cohesion and willingness to intervene was strong, r = .69, p < .001. The retained items from the two-factor models are presented in Table 3 , along with their factor loadings. Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability for the final items is also shown in Table 3 , demonstrating that all four scales demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability.

Research question 1: is there a significant association between hospital disorder and staff outcomes?

In order to examine the relationship between hospital disorder and staff outcomes, four separate models were run (i.e., models were run separately for physical disorder and social disorder, each with burnout and job satisfaction as dependent variables). Findings are presented in Supplementary File 2 . The results showed that physical disorder was significantly associated with higher burnout (β = .26, p < .001) and lower job satisfaction (β = −.40, p < .001). Similarly, social disorder was significantly associated with higher burnout (β = .23, p < .001) and lower job satisfaction (β = −.54, p < .001).

Research question 2: is there a significant association between hospital disorder and patient safety?

Two separate models were run for physical disorder and social disorder (Supplementary File 2 ). Physical disorder was significantly associated with lower patient safety scores (β = −.15, p = .008). Likewise, a greater extent of social disorder was significantly associated with lower levels of patient safety (β = −.26, p < .001).

Research question 3: does staff collective efficacy mediate the relationship between disorder and outcomes?

We then tested three separate mediation models for each outcome measure where the relationship between disorder and outcomes was mediated by collective efficacy via bootstrapping. For burnout, the model fit the data well, χ2 (81) = 142.75, TLI = .97, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .05. The findings presented in Fig. 3 show that there were significant negative paths from: social disorder to social cohesion (β = −.45, p = .003); social disorder to willingness to intervene (β = −.49, p = .002); social cohesion to burnout (β = −.23, p = .022); and willingness to intervene to burnout (β = −.33, p = .004). However, the paths from physical disorder to social cohesion (β = −.11, p = .077) and from physical disorder to willingness to intervene (β = −.04, p = .466) were not significant. Alongside these parameters, there was a significant direct effect from physical disorder to burnout (β = .18, p = .001), but not from social disorder to burnout (β = −.07, p = .351). Importantly, bootstrapped analyses for indirect effects indicated a significant indirect path from social disorder to burnout via social cohesion and willingness to intervene (β = .26, p = .001). However, the indirect path from physical disorder to burnout was not significant (β = .04, p = .205).

Model of disorder and burnout, mediated by collective efficacy

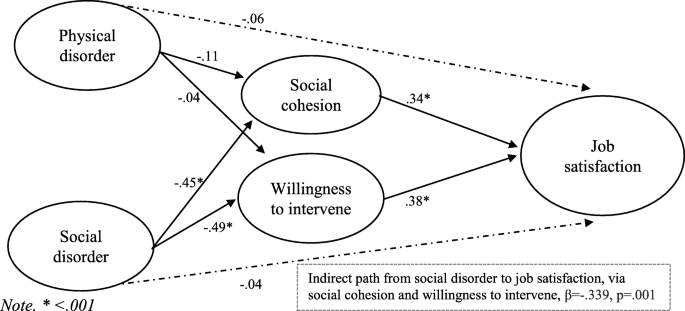

For job satisfaction, the model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2 (125) = 274.69, TLI = .95, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .06 (Fig. 4 ). The findings show that there was a significant path from social cohesion to job satisfaction (β = .34, p = .002) and from willingness to intervene to job satisfaction (β = .38, p = .001). The direct effects from physical disorder to job satisfaction (β = −.06, p = .233) and from social disorder to job satisfaction (β = −.04, p = .575) were not significant. Bootstrapped analyses for indirect effects indicated a significant indirect path from social disorder to job satisfaction via social cohesion and willingness to intervene (β = −.34, p = .001). However, the indirect path from physical disorder to burnout was not significant (β = −.05, p = .171).

Model of disorder and job satisfaction, mediated by collective efficacy

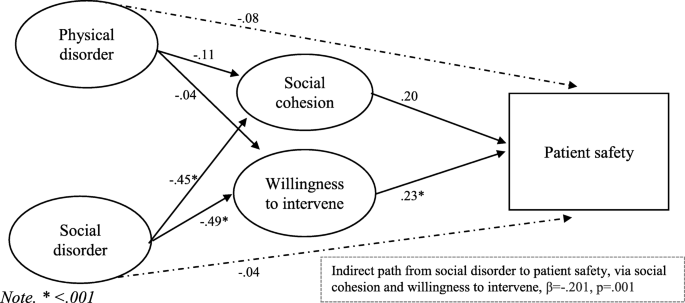

For patient safety, the model fit provided a satisfactory fit to the data, χ2 (81) = 171.26, TLI = .96, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .06. The findings are presented in Fig. 5 and show that there was a significant path from willingness to intervene to patient safety (β = .23, p = .041). The path from social cohesion to patient safety just failed to reach significance (β = .20, p = .057). The direct effects from physical disorder to patient safety (β = −.08, p = .155) and from social disorder to patient safety (β = −.04, p = .612) were not significant. The indirect effects indicated a significant indirect path from social disorder to patient safety via social cohesion and willingness to intervene (β = −.20, p = .001). However, the indirect path from physical disorder to burnout was not significant (β = −.03, p = .174).

Model of disorder and patient safety, mediated by collective efficacy

BWT and related theories of neighbourhood disorder were used here as a novel way of studying the influence of hospital environment on staff outcomes and patient safety. In this study, we developed and validated a survey instrument of disorder and collective efficacy for hospital staff—the DaCEs. In response to our research questions, we found that both social and physical disorder were positively related to burnout and negatively related to job satisfaction and patient safety. This indicated that the greater the perceived disorder in hospitals the higher the burnout and lower job satisfaction in hospital staff, and lower ratings of patient safety. Although neighbourhood disorder theories are not perfectly applicable to a hospital setting, our findings are broadly analogous with previous neighbourhood research and suggest that while attending to the physical appearance of the hospital cannot alone guarantee better staff and patient outcomes, ignoring them can significantly increase the chances of poorer outcomes. The present study also found support for the contention that collective efficacy mediated the relationship between social disorder and outcomes (burnout, job satisfaction, patient safety), but not for physical disorder.

This study is one of the first to empirically evaluate neighbourhood disorder theories in healthcare. Consistent with the original BWT, we found that perceptions of social and physical disorder were associated with potential safety issues [ 2 ], in this case, low patient safety ratings in hospitals. Past research on neighbourhood disorder supports the association between perceived neighbourhood disorder and poor mental health [ 51 ], corresponding with the present study’s findings that hospital disorder was associated with low job satisfaction and high burnout. These findings shed light on the potential relationship between culture and disorder in hospitals. We recognise that BWT has received considerable criticism over the years [ 1 ], particularly in response to controversial policy developments that were based on the BWT perspective. At this point, we must make clear that we do not advocate such policies, and find them abhorrent. However, we do contend that it seems likely that disorder is a marker for a poorer workplace culture compared to a workplace that is perceived as more orderly by hospital staff. This represents further converging evidence that having a productive, functional, more orderly culture is good for both staff and patients and not having a collective, efficacious, productive, collaborative culture is not [ 52 ].

Consistent with previous research, our study findings demonstrate the differential effects of physical and social disorder on outcome measures [ 11 , 53 ]. While both types of disorder were found to be directly related to all outcomes, once collective efficacy was added to the model, the relationship between social disorder and each of the outcomes became non-significant. In summary, consistent with the assertions of Sampson and Raudenbush [ 4 ] and in concordance with social disorganisation theory, we found that the relationship between social disorder and all outcome measures was significantly mediated by collective efficacy; however, this was not the case for physical disorder. As for the potential reasons for these findings, from a research standpoint, social disorder and physical disorder are qualitatively different: neighbourhood social disorder has been described as “episodic behaviour” involving individuals “which only lasts for a limited amount of time”, whereas neighbourhood physical disorder instead refers to “the deterioration of urban landscapes” and “does not necessarily involve actors” ([ 53 ] p5). Similarly, in a hospital setting, physical disorder may be perceived by staff as a more stable and constant presence in the hospital environment. In other words, hospital staff may be “inoculated” ([ 12 ] p411) to the presence of physical disorder in the hospital environment, with collective efficacy being less likely to alter or affect the relationship between physical disorder and outcomes.

A further explanation as to why the relationship between social disorder and all three outcome measures were mediated by collective efficacy, but not for physical disorder, is because when social disorder manifests in hospitals (e.g., non-compliance, wasting time), healthcare staff must work together to ‘pick up the slack’ to avoid serious threats to the safety and quality of care delivered. For example, if certain staff are absent or late in a particular hospital ward, the rest of the staff in that ward must work together to negate the likelihood of patient safety issues. Working as a team to make up for the social disorder may prevent any one individual staff member experiencing burnout and low job satisfaction. Indeed, this is consistent with past research showing that collaboration in hospitals has a positive effect on staff and patient outcomes, including patient safety, burnout, and job satisfaction [ 54 ]. This differs to physical disorder (e.g., run-down hospital, vandalism) where it is not necessarily seen as the responsibility of hospital staff to work collaboratively and address this form of disorder. That is, while staff must work together to address issues of social disorder such as someone being absent or late, physical disorder is more likely to be seen to be needing to be dealt with on the organisational level. For example, a hospital being in need of repair needs intervention from the government, NHS Trust, Board of Governors or local health district which can provide the necessary resources to redevelop the infrastructure.

This study thereby contributes to the broader BWT and related neighbourhood disorder field as it highlights the importance of keeping social and physical disorder as separate constructs when assessing disorder. Further, this study highlights the importance of encouraging collective efficacy among hospital staff as it can act as a barrier between social disorder and poor staff outcomes and patient safety issues.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was the development of an initial psychometric profile for the measure of disorder and collective efficacy for hospitals, with its psychometric properties being assessed across four hospital sites in Australia. As to limitations, the study was based on self-reports of staff and, as with all research of this kind, is reflective of the perceptions of the agents involved. We did not include patients’ self-reports or observational research. The data was collected at one time point and therefore cannot identify any causal influence of physical and social disorder on outcomes which would require longitudinal studies involving repeated sampling on the same set of study participants. The findings concerning patient safety would need to be replicated in view of the fact that only one item was used to assess patient safety and therefore the measure has unestablished reliability. The DaCEs also warrants further cross-validation of its factor structure, as the final items were selected on the basis of results from our four included hospitals, and may not be generalisable to all hospital systems. Optimally, CFA should be randomly divided into subgroups (calibration and validation samples) to validate and verify the factor structure of the tool [ 55 ]. However, the current study was limited by the relatively modest sample size, and further work would be needed to verify the validity of the tool.

As one of the first studies to empirically test theories of neighbourhood disorder in healthcare, we found that a positive, orderly, productive culture is likely to lead to wellbeing for staff and better safety for patients, and vice versa. This is a modified study of BWT and related theories in hospitals, and one of the few studies to assess associations between different forms of disorder, collective efficacy, and staff and patient outcomes. Our hypothesised mediation model was supported, showing that the relationship between social disorder and outcomes (job satisfaction, burnout, patient safety) was mediated by collective efficacy. Having established and tested the robustness of the model, we offer it for new applications and future studies on this topic and highlight the importance of studying physical and social disorder as separate constructs. This study demonstrates the potential benefits of encouraging collective efficacy among hospital staff as it can act as a barrier to poor staff wellbeing and patient safety issues when there is social disorder.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Broken windows theory

Disorder and Collective Efficacy Survey

Confirmatory factor analysis

Structural equation modelling

Maslach Burnout Inventory

Hospital Survey of Patient Safety Culture

Expectation Maximisation

Tucker Lewis Index

Comparative Fit Index

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

Kubrin CE. Making order of disorder: a call for conceptual clarity. Criminol Pub Pol’y. 2008;7:203.

Article Google Scholar

Wilson JQ, Kelling GL. Broken windows: the police and neighborhood safety. Atl Mon. 1982;211:29–38.

Google Scholar

Sampson RJ, Groves WB. Community structure and crime: testing social-disorganization theory. Am J Sociol. 1989;94:774–802.

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Systematic social observation of public spaces: a new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. Am J Sociol. 1999;105:603–51.

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–24.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ranasinghe P. Jane Jacobs’ framing of public disorder and its relation to the ‘broken windows’ theory. Theor Criminol. 2012;16:63–84.

Churruca K, Ellis LA, Braithwaite J. ‘Broken hospital windows’: debating the theory of spreading disorder and its application to healthcare organizations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:201.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Yang S-M. Social disorder and physical disorder at places. Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice; 2014. p. 4922–32.

Book Google Scholar

Skogan WG. Disorder and decline: crime and the spiral of decay in American neighborhoods. Berkeley: UC Press; 1992.

Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disorder, subjective alienation, and distress. J Health Soc Sci. 2009;50:49–64.

Yang S-M. Assessing the spatial–temporal relationship between disorder and violence. J Quant Criminol. 2010;26:139–63.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hinkle JC. The relationship between disorder, perceived risk, and collective efficacy: a look into the indirect pathways of the broken windows thesis. Crim Justice Stud. 2013;26:408–32.

Doran BJ, Burgess MB. Putting fear of crime on the map: investigating perceptions of crime using geographic information systems. London: Springer; 2011.

Fagan J, Davies G. Street stops and broken windows: Terry, race, and disorder in New York City. Fordham Urb LJ. 2000;28:457.

Xu Y, Fiedler ML, Flaming KH. Discovering the impact of community policing: the broken windows thesis, collective efficacy, and citizens’ judgment. JRCD. 2005;42:147–86.

Plank Stephen B, Bradshaw Catherine P, Young H. An application of “broken-windows” and related theories to the study of disorder, fear, and collective efficacy in schools. Am J Educ. 2009;115:227–47.

Ramos J, Torgler B. Are academics messy? Testing the broken windows theory with a field experiment in the work environment. RLE. 2012;8:563–77.

Lim MSC, Hellard ME, Aitken CK. The case of the disappearing teaspoons: longitudinal cohort study of the displacement of teaspoons in an Australian research institute. BMJ. 2005;331:1498–500.

Kayral İH. Can the theory of broken windows be used for patients safety in city hospitals management model? Hacettepe Sağlık İdaresi Dergisi. 2019;22:677–94.

Demirel ET, Emul E. Evaluation of the Broken Windows Theory in Terms of Patient Safety. Multidimensional Perspectives and Global Analysis of Universal Health Coverage. United States: IGI Global; 2020. p. 266–84.

McNamara SA. The normalization of deviance: what are the perioperative risks? AORN J. 2011;93:796–801.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Erasmus V, Brouwer W, van Beeck EF, Oenema A, Daha TJ, Richardus JH, et al. A qualitative exploration of reasons for poor hand hygiene among hospital workers: lack of positive role models and of convincing evidence that hand hygiene prevents cross-infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:415–9.

Zhou C, Mou H, Xu W, Li Z, Liu X, Shi L, et al. Study on factors inducing workplace violence in Chinese hospitals based on the broken window theory: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016290.

Gershon RRM, Karkashian CD, Grosch JW, Murphy LR, Escamilla-Cejudo A, Flanagan PA, et al. Hospital safety climate and its relationship with safe work practices and workplace exposure incidents. Am J Infect Control. 2000;28:211–21.

Debono DS, Greenfield D, Travaglia JF, Long JC, Black D, Johnson J, et al. Nurses’ workarounds in acute healthcare settings: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:175.

Ekstedt M, Cook R. In: Wears RL, Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J, editors. The Stockholm Blizzard of 2012. Surrey, England, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 2015.

Wears RL, Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J. Resilient health care: the resilience of everyday clinical work. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.; 2015.

Amalberti R, Vincent C, Auroy Y, de Saint Maurice G. Violations and migrations in health care: a framework for understanding and management. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:i66–71.

Eijkelenboom A, Bluyssen PM. Comfort and health of patients and staff, related to the physical environment of different departments in hospitals: a literature review. Intell Build Int. 2019;0:1–19.

Laschinger HKS, Wong CA, Grau AL. The influence of authentic leadership on newly graduated nurses’ experiences of workplace bullying, burnout and retention outcomes: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:1266–76.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. IRSD INTERACTIVE MAP. 2033055001 - Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. Canberra: ABS; 2016.

Qualtrics. Qualtrics 2014 [Available from: http://www.qualtrics.com/ .

Coyne I, Bartram D. Personnel managers’ perceptions of dishonesty in the workplace. Hum Resour Manag J. 2000;10:38.

NSW Health. 2015 YourSay workplace Cultue survey: overall. Sydney, NSW, AUS: ORC International; 2015.

Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB, Rowan K, Vella K, Boyden J, et al. The safety attitudes questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:44.

Schaufeli W, Enzmann D, Girault N. Measurement of burnout: a review. In: Schaufeli WB, Maslach C, Marek T, editors. Professional burnout: recent developments in theory and research. Washington: Taylor & Francis; 1993. p. 199–215.

Maslach C, Jackson S. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav. 1981;2:99–113.

Maslach C, Schaufeli W, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422.

Bowling N, Hammond G. A meta-analytic examination of the construct validity of the Michigan organizational assessment questionnaire job satisfaction subscale. J Vocat Behav. 2008;73:63–77.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Surveys on patient safety culture. Rockville, MD, US: United States Department of Health & Human Services; 2017.

Corp IBM. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 25.0. IBM Corp: Armonk, NY; 2017.