WATCH TV LIVE

Watch Billy Graham Statue Unveiling Live on Newsmax

Pros and cons of 'broken window' crime prevention strategy.

By Breana Noble | Tuesday, 16 June 2015 04:41 PM EDT

- 5 Stories of Dogs Rescued by Police

- 6 Astonishingly Heroic Acts of Police Officers

© 2024 Newsmax. All rights reserved.

Sign up for Newsmax’s Daily Newsletter

Receive breaking news and original analysis - sent right to your inbox.

PLEASE NOTE: All information presented on Newsmax.com is for informational purposes only. It is not specific medical advice for any individual. All answers to reader questions are provided for informational purposes only. All information presented on our websites should not be construed as medical consultation or instruction. You should take no action solely on the basis of this publication’s contents. Readers are advised to consult a health professional about any issue regarding their health and well-being. While the information found on our websites is believed to be sensible and accurate based on the author’s best judgment, readers who fail to seek counsel from appropriate health professionals assume risk of any potential ill effects. The opinions expressed in Newsmaxhealth.com and Newsmax.com do not necessarily reflect those of Newsmax Media. Please note that this advice is generic and not specific to any individual. You should consult with your doctor before undertaking any medical or nutritional course of action.

- Sci & Tech

Interest-Based Advertising | Do not sell or share my personal information

Newsmax, Moneynews, Newsmax Health, and Independent. American. are registered trademarks of Newsmax Media, Inc. Newsmax TV, and Newsmax World are trademarks of Newsmax Media, Inc.

Download the NewsmaxTV App

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Broken Windows Theory

How Environment Impacts Behavior

Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/RachaelGreenProfilePicture1-a3b8368ef3bb47ccbac92c5cc088e24d.jpg)

Akeem Marsh, MD, is a board-certified child, adolescent, and adult psychiatrist who has dedicated his career to working with medically underserved communities.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/akeemmarsh_1000-d247c981705a46aba45acff9939ff8b0.jpg)

Verywell / Dennis Madamba

Origins and Explanation

- Application

- Impact on Behavior

- Positive Environments

The broken windows theory was proposed by James Q. Wilson and George Kelling in 1982, arguing that there was a connection between a person’s physical environment and their likelihood of committing a crime.

The theory has been a major influence on modern policing strategies and guided later research in urban sociology and behavioral psychology . But it’s also come under increasing scrutiny and some critics have argued that its application in policing and other contexts has done more harm than good.

The theory is named after an analogy used to explain it. If a window in a building is broken and remains unrepaired for too long, the rest of the windows in that building will eventually be broken, too. According to Wilson and Kelling, that’s because the unrepaired window acts as a signal to people in that neighborhood that they can break windows without fear of consequence because nobody cares enough to stop it or fix it. Eventually, Wilson and Kelling argued, more serious crimes like robbery and violence will flourish.

The idea is that physical signs of neglect and deterioration encourage criminal behavior because they act as a signal that this is a place where disorder is allowed to persist. If no one cares enough to pick up the litter on the sidewalk or repair and reuse abandoned buildings, maybe they won’t care enough to call the police when they see a drug deal or a burglary either.

How Is the Broken Windows Theory Applied?

The theory sparked a wave of “broken windows” or “zero tolerance” policing where law enforcement began cracking down on nonviolent behaviors like loitering, graffiti, or panhandling. By ramping up arrests and citations for perceived disorderly behavior and removing physical signs of disorder from the neighborhood, police hope to create a more orderly environment that discourages more serious crime.

The broken windows theory has been used outside of policing, as well, including in the workplace and in schools. Using a similar zero tolerance approach that disciplines students or employees for minor violations is thought to create more orderly environments that foster learning and productivity .

“By discouraging small acts of misconduct, such as tardiness, minor rule violations, or unprofessional conduct, employers seek to promote a culture of accountability, professionalism, and high performance,” said David Tzall Psy.D., a licensed forensic psychologist and Deputy Director for the Health and Wellness Unit of the NYPD.

Criticism of the Broken Window Theory

While the idea that one broken window leads to many sounds plausible, later research on the topic failed to find a connection. “The theory oversimplifies the causes of crime by focusing primarily on visible signs of disorder,” Tzall said. “It neglects underlying social and economic factors, such as poverty, unemployment, and lack of education, which are known to be important contributors to criminal behavior.”

When researchers account for those underlying factors, the connection between disordered environments and crime rates disappears.

In a report published in 2016, the NYPD itself found that its “quality-of-life” policing—another term for broken windows policing—had no impact on the city’s crime rate. Between 2010 and 2015, the number of “quality-of-life” summons issued by the NYPD for things like open containers, public urination, and riding bicycles on the sidewalk dropped by about 33%.

While the broken windows theory would theorize that serious crimes would spike when the police stopped cracking down on those minor offenses, violent crimes and property crimes actually decreased during that same time period.

“Policing based on broken windows theory has never been shown to work,” said Kimberly Vered Shashoua, LCSW , a therapist who works with marginalized teens and young adults. “Criminalizing unhoused people, low socioeconomic status households, and others who create this type of ‘crime’ doesn't get to the root of the problem,”

Not only have policing efforts that focus on things like graffiti or panhandling failed to have any impact on violent crime, they have often been used to target marginalized communities. “The theory's implementation can lead to biased policing practices as law enforcement officers can concentrate their efforts on low-income neighborhoods or communities predominantly populated by minority groups,” Tzall said.

That biased policing happens, in part, because there’s no objective measure of disordered environments so there’s a lot of room for implicit bias and discrimination to influence decision-making about which neighborhoods to target in crackdowns.

Studies show that neighborhoods where residents are predominantly Black or Latino are perceived as more disorderly and prone to crime than neighborhoods where residents are mostly white, even when police-recorded crime rates and physical signs of physical deterioration in the environment were the same.

Moreover, many of the behaviors that are used by police and researchers as signs of disorder are influenced by racial and class bias . Drinking and hanging out are both legal activities that are viewed as orderly when they happen in private spaces like a home or bar, for example. But those who socialize and drink in parks or on stoops outside their building are viewed as disorderly and charged with loitering and public drunkenness.

The Impact of Physical Environment on Behavior

While the broken windows theory and its application are flawed, the underlying idea that our physical environment can influence our behavior does hold some water. On one hand, “the physical environment conveys social norms that influence our behavior,” Tzall explained. “When we observe others adhering to certain norms in a particular space, we tend to adjust our own behavior to align with them.”

If a person sees litter on the street, they might be more likely to litter themselves, for example. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll make the leap from littering to robbery or violent assault. Moreover, litter can often be a sign that there aren’t enough public trashcans available on the streets for people to throw away food wrappers and other waste while they’re out. In that scenario, installing more trashcans would do far more to reduce litter than increasing the number of citations for littering.

“The design and layout of spaces can also signal specific expectations and guide our actions,” Tzall explained. In the litter example, then, the addition of more trashcans could also act as an environmental cue to encourage throwing trash away rather than littering.

How to Create Positive Environments to Foster Safety, Health, and Well-Being

Ultimately, reducing crime requires addressing the root causes of poverty and social inequality that lead to crime. But taking care of public spaces and neighborhoods to keep them clean and enjoyable can still have a positive impact on the communities who live in and use them.

“Positive environments provide opportunities for meaningful interactions and collaboration among community members,” Tzall said. “Access to green spaces, recreational facilities, mental health resources, and community services contribute to physical, mental, and emotional health,” said Tzall.

By creating more positive environments, we can encourage healthier lifestyle choices—like adding protected bike lanes to encourage people to ride bikes—and prosocial behavior —like adding basketball courts in parks to encourage people to meet and play a game with their neighbors.

At the individual level, Tzall suggests people “can initiate or participate in community projects, volunteer for local organizations, support inclusive initiatives, engage in dialogue with neighbors, and collaborate with local authorities or community leaders.” Create positive environments by taking the initiative to pick up litter when you see it, participate in tree planting initiatives, collaborate with your neighbors to establish a community garden, or volunteer with a local organization to advocate for better public spaces and resources.

Wilson JQ and Kelling GL. Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety . The Atlantic Monthly. 1982.

Harcourt B, Ludwig J. Broken windows: new evidence from new york city and a five-city social experiment . University of Chicago Law Review. 2006;73(1).

Peters M, Eure P. An Analysis of Quality-of-Life Summonses, Quality-of-Life Misdemeanor Arrests, and Felony Crime in New York City, 2010-2015 . New York City Department of Investigation Office of the Inspector General for the NYPD; 2016.

Sampson RJ. Disparity and diversity in the contemporary city: social (Dis)order revisited . The British Journal of Sociology. 2009;60(1):1-31. Doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01211.x

By Rachael Green Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

Pros and Cons of Broken Windows Policing

Jordon Layne

Founder of Luxwisp – Protector of the wallet. (Don’t tell anyone it is in my pocket) – Bachelor’s degree in Biological Sciences

The debate surrounding Broken Windows Policing hinges on a critical evaluation of its effectiveness versus its ethical implications. Proponents argue that it significantly reduces crime rates by addressing minor offenses, thereby preventing more serious crimes.

Critics, however, raise valid concerns regarding civil liberties and the potential for racial profiling, suggesting that the strategy may do more harm than good in vulnerable communities.

As we explore this contentious topic, it becomes imperative to consider both sides of the argument. This balanced approach will offer insights into whether the benefits of Broken Windows Policing justify the potential costs to society.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- Broken windows policing effectively reduces minor crime rates, enhancing community safety perception.

- It risks civil liberties violations and disproportionately impacts marginalized communities.

- Alternatives like community policing and restorative justice focus on collaboration and addressing root causes of crime.

- The approach's impact on crime rates and community relations remains contested, prompting calls for reform and more inclusive strategies.

Understanding Broken Windows Theory

Introduced by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling in 1982, the Broken Windows Theory posits a significant correlation between physical disorder and increased crime rates, suggesting that addressing minor offenses can prevent more serious crimes. This theory has fundamentally shaped law enforcement strategies over the decades, leading to the adoption of broken windows or zero tolerance policing in various cities. By focusing on minor offenses such as loitering, graffiti, and public urination, the theory advocates for a proactive approach to crime prevention, aiming to maintain order and deter criminal activities.

However, the theory has not been without its critics, who argue that it oversimplifies the complex causes of crime by neglecting the underlying social and economic factors. Despite these criticisms, the Broken Windows Theory has underscored the significant impact that the physical environment can have on behavior. It highlights how neglect and deterioration within a community can create an atmosphere that encourages criminal behavior. The theory suggests that by maintaining orderly and well-kept environments, communities can reduce crime rates and improve overall safety.

Pros of Broken Windows Policing

Broken Windows Policing is a strategy that has shown promise in reducing minor crime rates, which is a foundational step towards fostering safer communities.

By addressing smaller infractions, it not only enhances the perception of safety among residents but also encourages a culture of lawful behavior.

This approach, when implemented effectively, can be a pivotal factor in maintaining public order and reinforcing community standards.

Reduces Minor Crime Rates

One of the notable advantages of Broken Windows Policing is its efficacy in diminishing rates of minor crimes across various urban settings. This approach emphasizes the importance of maintaining order by enforcing laws related to quality-of-life offenses. The strategy is grounded in the theory that addressing minor infractions can prevent the escalation of criminal behavior, thereby contributing to a safer urban environment.

The effectiveness of Broken Windows Policing in reducing low-level criminal activities is supported by several key factors:

- Implementation targets small offenses to prevent serious crimes.

- Creates a deterrent effect on potential offenders.

- Tackling disorderly behavior early decreases overall crime rates.

- Correlation between enforcing quality-of-life offenses and decline in criminal activity.

Enhances Community Safety Perception

By addressing minor offenses promptly, broken windows policing significantly boosts the community's perception of safety. This strategy involves law enforcement focusing on minor crimes and disorder, which, in turn, makes residents feel more secure in their surroundings.

The visible absence of vandalism, public intoxication, and other forms of public disorder conveys a sense of order and discipline that reassures the community. Furthermore, this proactive policing approach can prevent more severe crimes from occurring by maintaining a high standard of public order.

As a result, the improved perception of safety among residents fosters a stronger trust in law enforcement agencies. Overall, the emphasis on addressing small-scale infractions plays a critical role in enhancing the public's feeling of security and well-being within their neighborhoods.

Encourages Lawful Behavior

Adopting Broken Windows Policing strategies plays a pivotal role in fostering a culture of lawfulness. It emphasizes the importance of addressing minor offenses swiftly to deter more significant criminal activities. This approach is rooted in the philosophy that maintaining order in public spaces can effectively reduce crime by sending a clear message that violations of the law, no matter how small, will not be tolerated.

- Encourages lawful behavior by focusing on minor offenses promptly.

- Reinforces social norms and values within communities, deterring more serious crimes.

- Aims to create a sense of order and accountability, leading to a safer environment.

- Prevents the escalation of criminal activities by addressing small violations, promoting a culture of compliance with the law.

Cons of Broken Windows Policing

While Broken Windows Policing aims to maintain order, it raises significant concerns regarding civil liberties and racial profiling. The strategy's focus on minor offenses can lead to potential infringements on individuals' rights, as law enforcement may overstep boundaries in pursuit of maintaining public order. This approach often results in disproportionate targeting of minorities, exacerbating concerns about racial profiling and inequality within the justice system. Such practices not only undermine the principles of fairness and equality but also contribute to a growing distrust between communities and police forces.

Moreover, prioritizing minor crimes can divert essential resources and attention from more severe offenses, potentially compromising public safety by neglecting more significant threats. This misallocation of resources underscores a critical flaw in the Broken Windows theory, questioning its efficacy in crime prevention and community safety.

Additionally, the approach risks criminalizing poverty, as disadvantaged individuals are more likely to be penalized for minor infractions. This exacerbates social inequalities, as those with fewer resources are disproportionately affected, further entrenching cycles of poverty and criminalization. These factors collectively highlight the fundamental issues with Broken Windows Policing, questioning its overall benefit to society.

Impact on Community Relations

The implementation of broken windows policing has significant implications for community relations, particularly concerning trust and perceptions of safety.

As the strategy prioritizes minor offenses, it can inadvertently strain the relationship between law enforcement and the communities they serve, leading to a decrease in trust and cooperation.

This shift in safety perceptions and trust erosion can fundamentally alter the dynamic between police forces and community members, making collaborative efforts to address crime more challenging.

Trust Erosion

Implementing broken windows policing has often resulted in the erosion of trust between law enforcement and the communities they serve, primarily due to heightened enforcement of minor offenses. This strategy, while aimed at reducing crime, can inadvertently impact community relations negatively.

Communities may feel targeted and over-policed, leading to resentment and decreased cooperation with law enforcement.

Minorities and marginalized groups often bear the brunt of negative interactions, further damaging trust.

Public perception of law enforcement can suffer, impacting the willingness to report crimes and engage with police in solving community issues.

Lack of transparency and accountability in policing strategies can exacerbate tensions and hinder efforts to build positive relationships with the community.

Safety Perceptions Shift

Amid concerns over trust erosion, broken windows policing also has the potential to reshape community safety perceptions by proactively addressing minor offenses. This approach can significantly alter how residents view their safety and security in neighborhoods.

By swiftly tackling quality-of-life issues, communities often feel a heightened sense of safety. Such improvements in safety perceptions are pivotal, as they can enhance relations between the community and law enforcement, thereby fostering an environment of trust.

Addressing minor violations contributes to creating an atmosphere of order, which can deter more serious crimes and elevate overall community well-being. Moreover, positive interactions between residents and police officers in upholding community standards can fortify neighborhood bonds, leading to a more cohesive and secure community environment.

Alternatives to Broken Windows Policing

How can law enforcement effectively maintain public safety while fostering community trust, given the criticism of broken windows policing? In seeking alternatives, various strategies have been identified that prioritize collaboration, healing, and proactive engagement over punitive measures. These approaches focus not only on immediate safety but also on the long-term wellbeing and empowerment of communities. They aim to address the root causes of crime and build a foundation of trust and mutual respect between law enforcement and the communities they serve.

Key alternatives include:

- Community Policing: This strategy emphasizes a partnership between police and community members. It involves law enforcement engaging positively with residents, understanding their concerns, and working together to solve problems, thereby promoting mutual trust and respect.

- Restorative Justice: Focusing on the harm caused by crime, restorative justice seeks to bring offenders and victims together, encouraging accountability, understanding, and healing. This approach aims at reducing recidivism by addressing the underlying issues that lead to crime.

- Involving Residents in Safety Initiatives: Empowering community members to identify and address safety concerns collaboratively enhances public safety outcomes and strengthens neighborhood bonds.

- Addressing Root Causes of Crime: By focusing on underlying problems such as poverty, lack of education, and limited employment opportunities, these alternative approaches aim to prevent crime before it happens, leading to safer and more resilient communities.

These strategies represent a shift towards more inclusive, empathetic, and effective methods of maintaining public safety and fostering lasting community relationships.

Broken Windows and Crime Rates

While exploring alternatives to Broken Windows policing emphasizes community engagement and addressing root causes of crime, it's essential to examine the impact of Broken Windows theory on crime rates, particularly its application in New York City and the resulting changes in both minor and serious offenses.

Broken Windows policing, which focuses on addressing minor offenses to prevent more serious crimes, has been credited with a notable decrease in both petty and serious crime rates in New York City. The theory posits that neglecting minor disorderly behaviors can escalate into more significant criminal activities, such as burglaries. By targeting small acts of disorder, Broken Windows policing aims to prevent larger corruptions within the community.

This approach also encourages informal social control, fostering a sense of communal responsibility and order. Supporters of Broken Windows argue that this strategy not only reduces crime rates but also enhances the overall quality of life in neighborhoods. The effectiveness of Broken Windows policing in New York City showcases how prioritizing minor offenses can have a profound impact on reducing broader criminal activities, affirming the theory's foundational premise.

Future Directions in Policing

In the wake of shifting perspectives on law enforcement strategies, policing experts are advocating for a broader embrace of community policing to forge stronger bonds between officers and the communities they serve. This approach marks a significant shift from the traditional focus on crime fighting to a more holistic, relationship-based strategy. The aim is to rebuild trust, enhance public safety, and address the underlying issues that contribute to crime. This shift is evident in various cities across the United States, reflecting a growing consensus on the need for reform and the adoption of more inclusive policing practices.

To add depth and complexity to this discussion, consider the following points:

- New York City's legislative efforts to provide written guidance on quality-of-life offenses aim to ensure fairness and consistency in law enforcement.

- The introduction of foot patrols in cities like Milwaukee, Philadelphia, and New Haven has been shown to improve community engagement and safety.

- Portland and Seattle are focusing on renewing community policing strategies to foster trust and collaborative relationships with residents.

- These initiatives are part of broader efforts to reform policing practices, enhance community-police relations, and address the criticisms of broken windows policing.

In conclusion, Broken Windows Policing represents a multifaceted approach to crime prevention, with both merits and drawbacks that warrant careful consideration. While it can potentially deter crime and enhance neighborhood well-being, concerns regarding civil liberties, racial profiling, and resource allocation cannot be overlooked.

Moreover, the impact on community-police relations emphasizes the need for balanced strategies. Exploring alternatives and assessing the theory's effectiveness in reducing crime rates remain crucial for future directions in policing.

Related Posts:

Broken Windows Theory of Criminology

Charlotte Ruhl

Research Assistant & Psychology Graduate

BA (Hons) Psychology, Harvard University

Charlotte Ruhl, a psychology graduate from Harvard College, boasts over six years of research experience in clinical and social psychology. During her tenure at Harvard, she contributed to the Decision Science Lab, administering numerous studies in behavioral economics and social psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

The Broken Windows Theory of Criminology suggests that visible signs of disorder and neglect, such as broken windows or graffiti, can encourage further crime and anti-social behavior in an area, as they signal a lack of order and law enforcement.

Key Takeaways

- The Broken Windows theory, first studied by Philip Zimbardo and introduced by George Kelling and James Wilson, holds that visible indicators of disorder, such as vandalism, loitering, and broken windows, invite criminal activity and should be prosecuted.

- This form of policing has been tested in several real-world settings. It was heavily enforced in the mid-1990s under New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani, and Albuquerque, New Mexico, Lowell, Massachusetts, and the Netherlands later experimented with this theory.

- Although initial research proved to be promising, this theory has been met with several criticisms. Specifically, many scholars point to the fact that there is no clear causal relationship between lack of order and crime. Rather, crime going down when order goes up is merely a coincidental correlation.

- Additionally, this theory has opened the doors for racial and class bias, especially in the form of stop and frisk.

The United States has the largest prison population in the world and the highest per-capita incarceration rate. In 2016, 2.3 million people were incarcerated, despite a massive decline in both violent and property crimes (Morgan & Kena, 2019).

These statistics provide some insight into why crime regulation and mass incarceration are such hot topics today, and many scholars, lawyers, and politicians have devised theories and strategies to try to promote safety within society.

One such model is broken windows policing, which was first brought to light by American psychologist Philip Zimbardo (famous for his Stanford Prison Experiment) and further publicized by James Wilson and George Kelling. Since its inception, this theory has been both widely used and widely criticized.

What Is the Broken Windows Theory?

The broken windows theory states that any visible signs of crime and civil disorder, such as broken windows (hence, the name of the theory), vandalism, loitering, public drinking, jaywalking, and transportation fare evasion, create an urban environment that promotes even more crime and disorder (Wilson & Kelling, 1982).

As such, policing these misdemeanors will help create an ordered and lawful society in which all citizens feel safe and crime rates, including violent crime rates, are low.

Broken windows policing tries to regulate low-level crime to prevent widespread disorder from occurring. If these small crimes are greatly reduced, then neighborhoods will appear to be more cared for.

The hope is that if these visible displays of disorder and neglect are reduced, violent crimes might go down too, leading to an overall reduction in crime and an increase in public safety.

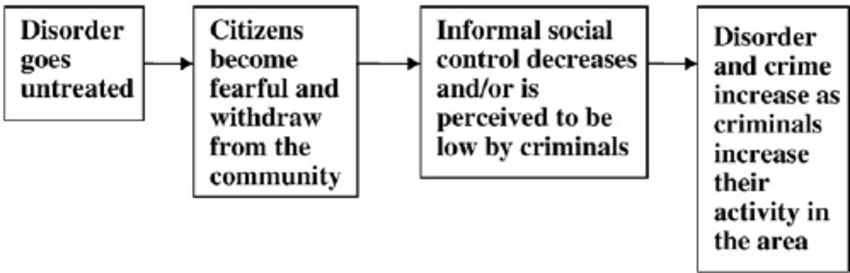

Source: Hinkle, J. C., & Weisburd, D. (2008). The irony of broken windows policing: A micro-place study of the relationship between disorder, focused police crackdowns and fear of crime. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36(6), 503-512.

Academics justify broken windows policing from a theoretical standpoint because of three specific factors that help explain why the state of the urban environment might affect crime levels:

- social norms and conformity;

- the presence or lack of routine monitoring;

- social signaling and signal crime.

In a typical urban environment, social norms and monitoring are not clearly known. As a result, individuals will look for certain signs and signals that provide both insight into the social norms of the area as well as the risk of getting caught violating those norms.

Those who support the broken windows theory argue that one of those signals is the area’s general appearance. In other words, an ordered environment, one that is safe and has very little lawlessness, sends the message that this neighborhood is routinely monitored and criminal acts are not tolerated.

On the other hand, a disordered environment, one that is not as safe and contains visible acts of lawlessness (such as broken windows, graffiti, and litter), sends the message that this neighborhood is not routinely monitored and individuals would be much more likely to get away with committing a crime.

With a decreased likelihood of detection, individuals would be much more inclined to engage in criminal behavior, both violent and nonviolent, in this type of area.

As you might be able to tell, a major assumption that this theory makes is that an environment’s landscape communicates to its residents in some way.

For example, proponents of this theory would argue that a broken window signals to potential criminals that a community is unable to defend itself against an uptick in criminal activity. It is not the literal broken window that is a direct cause for concern, but more so the figurative meaning that is ascribed to this situation.

It symbolizes a vulnerable and disjointed community that cannot handle crime – opening the doors to all kinds of unwanted activity to occur.

In neighborhoods that do have a strong sense of social cohesion among their residents, these broken windows are fixed (both literally and figuratively), giving these areas a sense of control over their communities.

By fixing these windows, undesired individuals and behaviors are removed, allowing civilians to feel safer (Herbert & Brown, 2006).

However, in environments in which these broken windows are left unfixed, residents no longer see their communities as tight-knit, safe spaces and will avoid spending time in communal spaces (in parks, at local stores, on the street blocks) so as to avoid violent attacks from strangers.

Additionally, when these broken windows are not fixed, it also symbolizes a lack of informal social control. Informal social control refers to the actions that regulate behavior, such as conforming to social norms and intervening as a bystander when a crime is committed, that are independent of the law.

Informal social control is important to help reduce unruly behavior. Scholars argue that, under certain circumstances, informal social control is more effective than laws.

And some will even go so far as to say that nonresidential spaces, such as corner stores and businesses, have a responsibility to actually maintain this informal social control by way of constant surveillance and supervision.

One such scholar is Jane Jacobs, a Canadian-American author and journalist who believed sidewalks were a crucial vehicle for promoting public safety.

Jacobs can be considered one of the original pioneers of the broken windows theory. One of her most famous books, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, describes how local businesses and stores provide a necessary sense of having “eyes on the street,” which promotes safety and helps to regulate crime (Jacobs, 1961).

Although the idea that community involvement, from both residents and non-residents, can make a big difference in how safe a neighborhood is perceived to be, Wilson and Keeling argue that the police are the key to maintaining order.

As major proponents of broken windows policing, they hold that formal social control, in addition to informal social control, is crucial for actually regulating crime.

Although different people have different approaches to the implementation of broken windows (i.e., cleaning up the environment and informal social control vs. an increase in policing misdemeanor crimes), the end goal is the same: crime reduction.

This idea, which largely serves as the backbone of the broken windows theory, was first introduced by Philip Zimbardo.

Examples of Broken Windows Policing

1969: philip zimbardo’s introduction of broken windows in nyc and la.

In 1969, Stanford psychologist Philip Zimbardo ran a social experiment in which he abandoned two cars that had no license plates and the hoods up in very different locations.

The first was a predominantly poor, high-crime neighborhood in the Bronx, and the second was a fairly affluent area of Palo Alto, California. He then observed two very different outcomes.

After just ten minutes, the car in the Bronx was attacked and vandalized. A family first approached the vehicle and removed the radiator and battery. Within the first twenty-four hours after Zimbardo left the car, everything valuable had been stripped and removed from the car.

Afterward, random acts of destruction began – the windows were smashed, seats were ripped up, and the car began to serve as a playground for children in the community.

On the contrary, the car that was left in Palo Alto remained untouched for more than a week before Zimbardo eventually went up to it and smashed the vehicle with a sledgehammer.

Only after he had done this did other people join the destruction of the car (Zimbardo, 1969). Zimbardo concluded that something that is clearly abandoned and neglected can become a target for vandalism.

But Kelling and Wilson extended this finding when they introduced the concept of broken windows policing in the early 1980s.

This initial study cascaded into a body of research and policy that demonstrated how in areas such as the Bronx, where theft, destruction, and abandonment are more common, vandalism would occur much faster because there are no opposing forces to this type of behavior.

As a result, such forces, primarily the police, are needed to intervene and reduce these types of behavior and remove such indicators of disorder.

1982: Kelling and Wilson’s Follow-Up Article

Thirteen years after Zimbardo’s study was published, criminologists George Kelling and James Wilson published an article in The Atlantic that applied Zimbardo’s findings to entire communities.

Kelling argues that Zimbardo’s findings were not unique to the Bronx and Palo Alto areas. Rather, he claims that, regardless of the neighborhood, a ripple effect can occur once disorder begins as things get extremely out of hand and control becomes increasingly hard to maintain.

The article introduces the broader idea that now lies at the heart of the broken windows theory: a broken window, or other signs of disorder, such as loitering, graffiti, litter, or drug use, can send the message that a neighborhood is uncared for, sending an open invitation for crime to continue to occur, even violent crimes.

The solution, according to Kelling and Wilson and many other proponents of this theory, is to target these very low-level crimes, restore order to the neighborhood, and prevent more violent crimes from happening.

A strengthened and ordered community is equipped to fight and deter crime (because a sense of order creates the perception that crimes go easily detected). As such, it is necessary for police departments to focus on cleaning up the streets as opposed to putting all of their energy into fighting high-level crimes.

In addition to Zimbardo’s 1969 study, Kelling and Wilson’s article was also largely inspired by New Jersey’s “Safe and Clean Neighborhoods Program” that was implemented in the mid-1970s.

As part of the program, police officers were taken out of their patrol cars and were asked to patrol on foot. The aim of this approach was to make citizens feel more secure in their neighborhoods.

Although crime was not reduced as a result, residents took fewer steps to protect themselves from crime (such as locking their doors). Reducing fear is a huge goal of broken-windows policing.

As Kelling and Wilson state in their article, the fear of being bothered by disorderly people (such as drunks, rowdy teens, or loiterers) is enough to motivate them to withdraw from the community.

But if we can find a way to make people feel less fear (namely by reducing low-level crimes), then they will be more involved in their communities, creating a higher degree of informal social control and deterring all forms of criminal activity.

Although Kelling and Wilson’s article was largely theoretical, the practice of broken windows policing was implemented in the early 1990s under New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani. And Kelling himself was there to play a crucial role.

Early 1990s: Bratton and Giuliani’s implementation in NYC

In 1985, the New York City Transit Authority hired George Kelling as a consultant, and he was also later hired by both the Boston and Los Angeles police departments to provide advice on the most effective method for policing (Fagan & Davies, 2000).

Five years later, in 1990, William J. Bratton became the head of the New York City Transit Police. In his role, Bratton cracked down on fare evasion and implemented faster methods to process those who were arrested.

He attributed a lot of his decisions as head of the transit police to Kelling’s work. Bratton was just the first to begin to implement such measures, but once Rudy Giuliani was elected as mayor in 1993, tactics to reduce crime began to really take off (Vedantam et al., 2016).

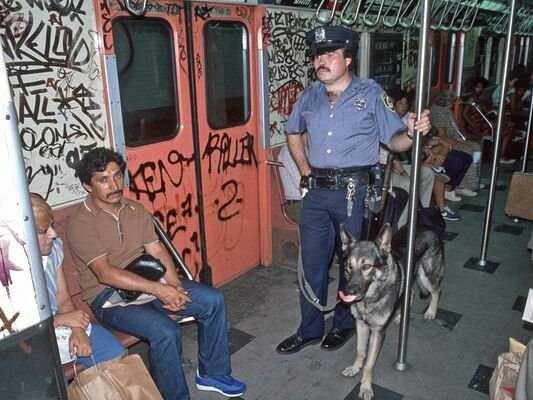

Together, Giuliani and Bratton first focused on cleaning up the subway system, where Bratton’s area of expertise lay. They sent hundreds of police officers into subway stations throughout the city to catch anyone who was jumping the turnstiles and evading the fair.

And this was just the beginning.

All throughout the 90s, Giuliani increased misdemeanor arrests in all pockets of the city. They arrested numerous people for smoking marijuana in public, spraying graffiti on walls, selling cigarettes, and they shut down many of the city’s night spots for illegal dancing.

Conveniently, during this time, crime was also falling in the city and the murder rate was rapidly decreasing, earning Giuliani re-election in 1997 (Vedantam et al., 2016).

To further support the outpouring success of this new approach to regulating crime, George Kelling ran a follow-up study on the efficacy of broken windows policing and found that in neighborhoods where there was a stark increase in misdemeanor arrests (evidence of broken windows policing), there was also a sharp decline in crime (Kelling & Sousa, 2001).

Because this seemed like an incredibly successful mode, cities around the world began to adopt this approach.

Late 1990s: Albuquerque’s Safe Streets Program

In Albuquerque, New Mexico, a Safe Streets Program was implemented to deter and reduce unsafe driving and crime rates by increasing surveillance in these areas.

Specifically, the traffic enforcement program influenced saturation patrols (that operated over a large geographic area), sobriety checkpoints, follow-up patrols, and freeway speed enforcement.

The effectiveness of this program was analyzed in a study done by the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (Stuser, 2001).

Results demonstrated that both Part I crimes, including homicide, forcible rape, robbery, and theft, and Part II crimes, such as sex offenses, kidnapping, stolen property, and fraud, experienced a total decline of 5% during the 1996-1997 calendar year in which this program was implemented.

Additionally, this program resulted in a 9% decline in both robbery and burglary, a 10% decline in assault, a 17% decline in kidnapping, a 29% decline in homicide, and a 36% decline in arson.

With these promising statistics came a 14% increase in arrests. Thus, the researchers concluded that traffic enforcement programs can deter criminal activity. This approach was initially inspired by both Zimbardo’s and Kelling and Wilson’s work on broken windows and provides evidence that when policing and surveillance increase, crime rates go down.

2005: Lowell, Massachusetts

Back on the east coast, Harvard University and Suffolk University researchers worked with local police officers to pinpoint 34 different crime hotspots in Lowell, Massachusetts. In half of these areas, local police officers and authorities cleaned up trash from the streets, fixed streetlights, expanded aid for the homeless, and made more misdemeanor arrests.

There was no change made in the other half of the areas (Johnson, 2009).

The researchers found that in areas in which police service was changed, there was a 20% reduction in calls to the police. And because the researchers implemented different ways of changing the city’s landscape, from cleaning the physical environment to increasing arrests, they were able to compare the effectiveness of these various approaches.

Although many proponents of the broken windows theory argue that increasing policing and arrests is the solution to reducing crime, as the previous study in Albuquerque illustrates. Others insist that more arrests do not solve the problem but rather changing the physical landscape should be the desired means to an end.

And this is exactly what Brenda Bond of Suffolk University and Anthony Braga of Harvard Kennedy’s School of Government found. Cleaning up the physical environment was revealed to be very effective, misdemeanor arrests were less so, and increasing social services had no impact.

This study provided strong evidence for the effectiveness of the broken windows theory in reducing crime by decreasing disorder, specifically in the context of cleaning up the physical and visible neighborhood (Braga & Bond, 2008).

2007: Netherlands

The United States is not the only country that sought to implement the broken windows ideology. Beginning in 2007, researchers from the University of Groningen ran several studies that looked at whether existing visible disorder increased crimes such as theft and littering.

Similar to the Lowell experiment, where half of the areas were ordered and the other half disorders, Keizer and colleagues arranged several urban areas in two different ways at two different times. In one condition, the area was ordered, with an absence of graffiti and littering, but in the other condition, there was visible evidence for disorder.

The team found that in disorderly environments, people were much more likely to litter, take shortcuts through a fenced-off area, and take an envelope out of an open mailbox that was clearly labeled to contain five Euros (Keizer et al., 2008).

This study provides additional support for the effect perceived order can have on the likelihood of criminal activity. But this broken windows theory is not restricted to the criminal legal setting.

2008: Tokyo, Japan

The local government of Adachi Ward, Tokyo, which once had Tokyo’s highest crime rates, introduced the “Beautiful Windows Movement” in 2008 (Hino & Chronopoulos, 2021).

The intervention was twofold. The program, on one hand, drawing on the broken windows theory, promoted policing to prevent minor crimes and disorder. On the other hand, in partnership with citizen volunteers, the authorities launched a project to make Adachi Ward literally beautiful.

Following 11 years of implementation, the reduction in crime was undeniable. Felony had dropped from 122 in 2008 to 35 in 2019, burglary from 104 to 24, and bicycle theft from 93 to 45.

This Japanese case study seemed to further highlight the advantages associated with translating the broken widow theory into both aggressive policing and landscape altering.

Other Domains Relevant to Broken Windows

There are several other fields in which the broken windows theory is implicated. The first is real estate. Broken windows (and other similar signs of disorder) can indicate low real estate value, thus deterring investors (Hunt, 2015).

As such, some recommend that the real estate industry adopt the broken windows theory to increase value in an apartment, house, or even an entire neighborhood. They might increase in value by fixing windows and cleaning up the area (Harcourt & Ludwig, 2006).

Consequently, this might lead to gentrification – the process by which poorer urban landscapes are changed as wealthier individuals move in.

Although many would argue that this might help the economy and provide a safe area for people to live, this often displaces low-income families and prevents them from moving into areas they previously could not afford.

This is a very salient topic in the United States as many areas are becoming gentrified, and regardless of whether you support this process, it is important to understand how the real estate industry is directly connected to the broken windows theory.

Another area that broken windows are related to is education. Here, the broken windows theory is used to promote order in the classroom. In this setting, the students replace those who engage in criminal activity.

The idea is that students are signaled by disorder or others breaking classroom rules and take this as an open invitation to further contribute to the disorder.

As such, many schools rely on strict regulations such as punishing curse words and speaking out of turn, forcing strict dress and behavioral codes, and enforcing specific classroom etiquette.

Similar to the previous studies, from 2004 to 2006, Stephen Plank and colleagues conducted a study that measured the relationship between the physical appearance of mid-Atlantic schools and student behavior.

They determined that variables such as fear, social order, and informal social control were statistically significantly associated with the physical conditions of the school setting.

Thus, the researchers urged educators to tend to the school’s physical appearance to help promote a productive classroom environment in which students are less likely to propagate disordered behavior (Plank et al., 2009).

Despite there being a large body of research that seems to support the broken windows theory, this theory does not come without its stark criticisms, especially in the past few years.

Major Criticisms

At the turn of the 21st century, the rhetoric surrounding broken windows drastically shifted from praise to criticism. Scholars scrutinized conclusions that were drawn, questioned empirical methodologies, and feared that this theory was morphing into a vehicle for discrimination.

Misinterpreting the Relationship Between Disorder and Crime

A major criticism of this theory argues that it misinterprets the relationship between disorder and crime by drawing a causal chain between the two.

Instead, some researchers argue that a third factor, collective efficacy, or the cohesion among residents combined with shared expectations for the social control of public space, is the causal agent explaining crime rates (Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999).

A 2019 meta-analysis that looked at 300 studies revealed that disorder in a neighborhood does not directly cause its residents to commit more crimes (O’Brien et al., 2019).

The researchers examined studies that tested to what extent disorder led people to commit crimes, made them feel more fearful of crime in their neighborhoods, and affected their perceptions of their neighborhoods.

In addition to drawing out several methodological flaws in the hundreds of studies that were included in the analysis, O’Brien and colleagues found no evidence that the disorder and crime are causally linked.

Similarly, in 2003, David Thatcher published a paper in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology arguing that broken windows policing was not as effective as it appeared to be on the surface.

Crime rates dropping in areas such as New York City were not a direct result of this new law enforcement tactic. Those who believed this were simply conflating correlation and causality.

Rather, Thatcher claims, lower crime rates were the result of various other factors, none of which fell into the category of ramping up misdemeanor arrests (Thatcher, 2003).

In terms of the specific factors that were actually playing a role in the decrease in crime, some scholars point to the waning of the cocaine epidemic and strict enforcement of the Rockefeller drug laws that contributed to lower crime rates (Metcalf, 2006).

Other explanations include trends such as New York City’s economic boom in the late 1990s that helped directly contribute to the decrease of crime much more so than enacting the broken windows policy (Sridhar, 2006).

Additionally, cities that did not implement broken windows also saw a decrease in crime (Harcourt, 2009), and similarly, crime rates weren’t decreasing in other cities that adopted the broken windows policy (Sridhar, 2006).

Specifically, Bernard Harcourt and Jens Ludwig examined the Department of Housing and Urban Development program that placed inner-city project residents into housing in more orderly neighborhoods.

Contrary to the broken windows theory, which would predict that these tenants would now commit fewer crimes once relocated into more ordered neighborhoods, they found that these individuals continued to commit crimes at the same rate.

This study provides clear evidence why broken windows may not be the causal agent in crime reduction (Harcourt & Ludwig, 2006).

Falsely Assuming Why Crimes Are Committed

The broken windows theory also assumes that in more orderly neighborhoods, there is more informal social control. As a result, people understand that there is a greater likelihood of being caught committing a crime, so they shy away from engaging in such activity.

However, people don’t only commit crimes because of the perceived likelihood of detection. Rather, many individuals who commit crimes do so because of factors unrelated to or without considering the repercussions.

Poverty, social pressure, mental illness, and more are often driving factors that help explain why a person might commit a crime, especially a misdemeanor such as theft or loitering.

Resulting in Racial and Class Bias

One of the leading criticisms of the broken windows theory is that it leads to both racial and class bias. By giving the police broad discretion to define disorder and determine who engages in disorderly acts allows them to freely criminalize communities of color and groups that are socioeconomically disadvantaged (Roberts, 1998).

For example, Sampson and Raudenbush found that in two neighborhoods with equal amounts of graffiti and litter, people saw more disorder in neighborhoods with more African Americans.

The researchers found that individuals associate African Americans and other minority groups with concepts of crime and disorder more so than their white counterparts (Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004).

This can lead to unfair policing in areas that are predominantly people of color. In addition, those who suffer from financial instability and may be of minority status are more likely to commit crimes in the first place.

Thus, they are simply being punished for being poor as opposed to being given resources to assist them. Further, many acts that are actually legal but are deemed disorderly by police officers are targeted in public settings but aren’t targeted when the same acts are conducted in private settings.

As a result, those who don’t have access to private spaces, such as homeless people, are unnecessarily criminalized.

It follows then that by policing these small misdemeanors, or oftentimes actions that aren’t even crimes at all, police departments are fighting poverty crimes as opposed to fighting to provide individuals with the resources that will make crime no longer a necessity.

Morphing into Stop and Frisk

Stop and frisk, a brief non-intrusive police stop of a suspect is an extremely controversial approach to policing. But critics of the broken windows theory argue that it has morphed into this program.

With broken-windows policing, officers have too much discretion when determining who is engaging in criminal activity and will search people for drugs and weapons without probable cause.

However, this method is highly unsuccessful. In 2008, the police made nearly 250,000 stops in New York, but only one-fifteenth of one percent of those stops resulted in finding a gun (Vedantam et al., 2016).

And three years later, in 2011, more than 685,000 people were stopped in New York. Of those, nine out of ten were found to be completely innocent (Dunn & Shames, 2020).

Thus, not only does this give officers free reins to stop and frisk minority populations at disproportionately high levels, but it also is not effective in drawing out crime.

Although broken windows policing might seem effective from a theoretical perspective, major valid criticisms put the practical application of this theory into question.

Given its controversial nature, broken windows policing is not explicitly used today to regulate crime in most major cities. However, there are still traces of this theory that remain.

Cities such as Ferguson, Missouri, are heavily policed and the city issues thousands of warrants a year on broken window types of crimes – from parking infractions to traffic violations.

And the racial and class biases that result from such an approach to law enforcement have definitely not disappeared.

Crime regulation is not easy, but the broken windows theory provides an approach to reducing offenses and maintaining order in society.

What is the broken glass principle?

The broken glass principle, also known as the Broken Windows Theory, posits that visible signs of disorder, like broken glass, can foster further crime and anti-social behavior by signaling a lack of regulation and community care in an area.

How does social context affect crime according to the broken windows theory?

The Broken Windows Theory proposes that the social context, specifically visible signs of disorder like vandalism or littering, can encourage further crime.

It suggests that these signs indicate a lack of community control and care, which can foster a climate of disregard for laws and social norms, leading to more severe crimes over time.

How did broken windows theory change policing?

The Broken Windows Theory influenced policing by promoting proactive attention to minor crimes and maintaining urban environments.

It led to strategies like “zero-tolerance” or “quality-of-life” policing, focusing on reducing visible signs of disorder to prevent more serious crime.

Braga, A. A., & Bond, B. J. (2008). Policing crime and disorder hot spots: A randomized controlled trial. Criminology, 46(3), 577-607.

Dunn, C., & Shames, M. (2020). Stop-and-Frisk data . Retrieved from https://www.nyclu.org/en/stop-and-frisk-data

Fagan, J., & Davies, G. (2000). Street stops and broken windows: Terry, race, and disorder in New York City. Fordham Urb. LJ , 28, 457.

Harcourt, B. E. (2009). Illusion of order: The false promise of broken windows policing . Harvard University Press.

Harcourt, B. E., & Ludwig, J. (2006). Broken windows: New evidence from New York City and a five-city social experiment. U. Chi. L. Rev., 73 , 271.

Herbert, S., & Brown, E. (2006). Conceptions of space and crime in the punitive neoliberal city. Antipode, 38 (4), 755-777.

Hunt, B. (2015). “Broken Windows” theory can be applied to real estate regulation- Realty Times. Retrieved from https://realtytimes.com/agentnews/agentadvice/item/40700-20151208-broken-windws-theory-can-be-applied-to-real-estate-regulation

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities . Vintage.

Johnson, C. Y. (2009). Breakthrough on “broken windows.” Boston Globe.

Keizer, K., Lindenberg, S., & Steg, L. (2008). The spreading of disorder. Science, 322 (5908), 1681-1685.

Kelling, G. L., & Sousa, W. H. (2001). Do police matter?: An analysis of the impact of new york city’s police reforms . CCI Center for Civic Innovation at the Manhattan Institute.

Metcalf, S. (2006). Rudy Giuliani, American president? Retrieved from https://slate.com/culture/2006/05/rudy-giuliani-american-president.html

Morgan, R. E., & Kena, G. (2019). Criminal victimization, 2018. Bureau of Justice Statistics , 253043.

O”Brien, D. T., Farrell, C., & Welsh, B. C. (2019). Looking through broken windows: The impact of neighborhood disorder on aggression and fear of crime is an artifact of research design. Annual Review of Criminology, 2 , 53-71.

Plank, S. B., Bradshaw, C. P., & Young, H. (2009). An application of “broken-windows” and related theories to the study of disorder, fear, and collective efficacy in schools. American Journal of Education, 115 (2), 227-247.

Roberts, D. E. (1998). Race, vagueness, and the social meaning of order-maintenance policing. J. Crim. L. & Criminology, 89 , 775.

Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1999). Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology, 105 (3), 603-651.

Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2004). Seeing disorder: Neighborhood stigma and the social construction of “broken windows”. Social psychology quarterly, 67 (4), 319-342.

Sridhar, C. R. (2006). Broken windows and zero tolerance: Policing urban crimes. Economic and Political Weekly , 1841-1843.

Stuster, J. (2001). Albuquerque police department’s Safe Streets program (No. DOT-HS-809-278). Anacapa Sciences, inc.

Thacher, D. (2003). Order maintenance reconsidered: Moving beyond strong causal reasoning. J. Crim. L. & Criminology, 94 , 381.

Vedantam, S., Benderev, C., Boyle, T., Klahr, R., Penman, M., & Schmidt, J. (2016). How a theory of crime and policing was born, and went terribly wrong . Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2016/11/01/500104506/broken-windows-policing-and-the-origins-of-stop-and-frisk-and-how-it-went-wrong

Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). Broken windows. Atlantic monthly, 249 (3), 29-38.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1969). The human choice: Individuation, reason, and order versus deindividuation, impulse, and chaos. In Nebraska symposium on motivation. University of Nebraska press.

Further Information

- Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). Broken windows. Atlantic monthly, 249(3), 29-38.

- Fagan, J., & Davies, G. (2000). Street stops and broken windows: Terry, race, and disorder in New York City. Fordham Urb. LJ, 28, 457.

- Fagan, J. A., Geller, A., Davies, G., & West, V. (2010). Street stops and broken windows revisited. In Race, ethnicity, and policing (pp. 309-348). New York University Press.

Related Articles

Criminology

What Do Criminal Psychologists Do?

Self-Control Theory Of Crime

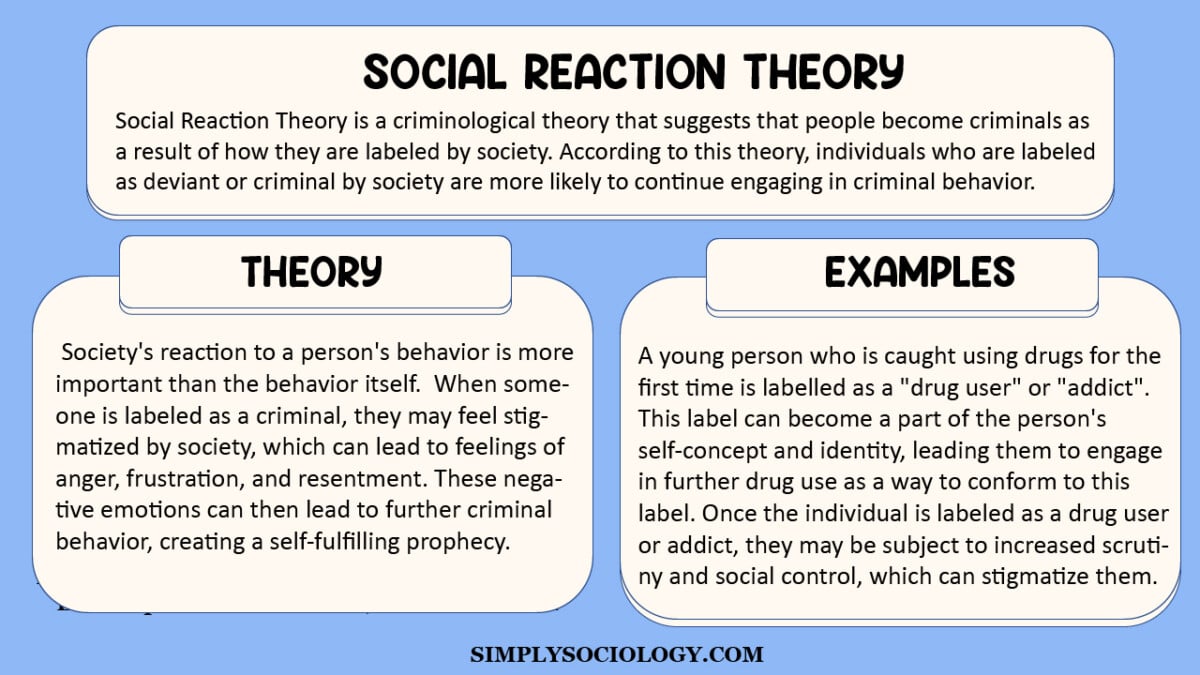

Social Reaction Theory (Criminology)

What Is Social Control In Sociology?

Subcultural Theories of Deviance

Tertiary Deviance: Definition & Examples

The Problem with “Broken Windows” Policing

A child walks past graffiti in New York City in 2014. New Police Commissioner Bill Bratton has made combating graffiti one of his top priorities, as part of the Broken Windows theory of policing. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

For years, police in Newark, N.J. regularly handed out citations to residents for minor offenses.

Known as “blue summonses,” the citations were intended to curb crime in a city rife with violence. Officers who racked up high tallies were rewarded with better assignments and overtime, according to police and federal officials.

Ultimately, police and residents said, the practice damaged the Newark PD’s relationship with the minority community and did little to reduce crime. It also helped lead to federal intervention in the police department last year.

Newark’s blue summonses were rooted in the 1980s-era theory known as “Broken Windows,” which argues that maintaining order by policing low-level offenses can prevent more serious crimes.

But in cities where Broken Windows has taken root, there’s little evidence that it’s worked as intended. The theory has instead resulted in what critics say is aggressive over-policing of minority communities, which often creates more problems than it solves. Such practices can strain criminal justice systems, burden impoverished people with fines for minor offenses, and fracture the relationship between police and minorities. It can also lead to tragedy: In New York in 2014, Eric Garner died from a police chokehold after officers approached him for selling loose cigarettes on a street corner.

Today, Newark and other cities have been compelled to re-think their approach to policing. But there are few easy solutions, and no quick way to repair years of distrust between police and the communities they serve.

How Broken Windows Began

Although it was first practiced in New York City, the idea of Broken Windows originated across the river in Newark, during a study by criminologist George Kelling. He found that introducing foot patrols in the city improved the relationship between police and black residents, and reduced their fear of crime. Together with colleague James Wilson, he wrote an influential 1982 article in The Atlantic , where the pair used the analogy that a broken window, left unattended, would signal that no one cared and ultimately lead to more disorder and even crime.

Kelling has since said that the theory has often been misapplied. He said that he envisioned Broken Windows as a tactic in a broader effort in community policing. Officers should use their discretion to enforce public order laws much as police do during traffic stops, he said. So an officer might issue a warning to someone drinking in public, or talk to kids skateboarding in a park about finding another place to play. Summons and arrests are only one tool, he said.

Kelling told FRONTLINE that over the years, as he began to hear about chiefs around the country adopting Broken Windows as a broad policy, he thought two words: “Oh s–t.”

“You’re just asking for a whole lot of trouble,” Kelling said. “You don’t just say one day, ‘Go out and restore order.’ You train officers, you develop guidelines. Any officer who really wants to do order maintenance has to be able to answer satisfactorily the question, ‘Why do you decide to arrest one person who’s urinating in public and not arrest [another]?’ … And if you can’t answer that question, if you just say ‘Well, it’s common sense,’ you get very, very worried.”

“So yeah,” he said. “There’s been a lot of things done in the name of Broken Windows that I regret.”

The Crime Debate

In practice, Broken Windows has come to be synonymous with misdemeanor arrests and summonses. In New York, the largest city to implement the practice, between 2010 and 2015, police issued 1.8 million quality of life summonses for offenses like disorderly conduct, public urination, and drinking or possessing small amounts of marijuana. Felony crime rates, meanwhile, declined.

But a report released last week by the New York Police Department’s inspector general’s office found “no evidence” that the drop in felony crime during those six years was linked to the quality of life summonses or misdemeanor arrests, which also declined during that time.

“That’s basically what we’ve been finding for years — a lack of any evidence of an effect,” said Bernard Harcourt, a Columbia Law School professor who has conducted two major studies on the impact of Broken Windows in New York and other cities.

The NYPD, led by Police Commissioner William Bratton, an early supporter of Broken Windows, said in a statement that the inspector general’s study was “deeply flawed” because it only examined arrests and summonses, not the agency’s broader quality-of-life efforts. Kelling, who has used misdemeanor arrests to evaluate the theory, wouldn’t comment on the study, saying he’s still a consultant to the department.

Defining Disorder

Some policing experts say that Broken Windows is a flawed theory, in part because of the focus on disorder. Kelling argues that in order to determine how to police a community, residents should identify their top concerns, and police should — assuming those issues are legitimate — patrol accordingly.

But disorder doesn’t look the same to everyone, Harcourt said. “Definitions about what is orderly or disorderly or needs to be ticketed, etc., are often loaded — racially loaded, culturally loaded, politically loaded,” he said. He cited New York’s recent decision to crack down on subway performers , who are often young black men, as an example.

Giving police discretion to enforce public order laws, he added, “becomes extraordinarily problematic because of racial, ethnic and class-based biases, and including implicit biases” that can come into play.

Linking disorder and crime can also change the way officers perceive residents, by creating the assumption that those committing minor offenses may do something worse if they’re not sanctioned, said David Thacher, a criminologist and professor at the University of Michigan.

“Broken Windows frames trivial misbehavior as the beginning of something much more serious,” Thacher said. “And I worry that that encourages the police to see a broader and broader swath of the people they’re policing as bad guys.”

It can also lead police to use minor offenses inappropriately as a pretext to search for more serious contraband, like guns or drugs, he said.

Newark’s Blue Summonses

In Newark, police saw the effect of blue summonses on their community first-hand. James Stewart, president of Newark’s Fraternal Order of Police, the largest police union, told FRONTLINE that the frequent stops and citations made people mistrust the police, and much less likely to cooperate when officers were investigating serious crimes.

But, he added, because officers who racked up summonses were chosen for plum assignments, many felt they didn’t have much of a choice.

To boost their summonses numbers, residents said, officers often chose “convenient targets,” including the elderly, or those with mental illnesses or disabilities, according to a civil rights investigation by the Justice Department. Those cited also appeared to be disproportionately black or Latino.

“[I]f you were to look at the blue summonses… the vast majority of them are issued to people in their 50s or 60s or maybe even older,” Stewart said. “Are they really the group of people that are committing the violent crimes here in Newark? You know, I would think not. But in order to get more numbers, the cops go after these people.”

Ryan Haygood, an attorney and longtime Newark resident, argued that officers shouldn’t have to overstep the law to maintain order.

“I don’t see an inconsistency with respecting people’s constitutional rights and protecting public safety,” he told FRONTLINE. “In our area we do have neighbors who have been victimized in violent ways by crime. But it doesn’t mean that police officers can, in three out of four of the stops, violate people’s constitutional rights.”

Meanwhile, he added, the department’s efforts have done little to make the community safer. In its investigation, the Justice Department also questioned the practice’s impact on crime reduction.

What Comes Next

Is there a way to conduct order-focused policing in black and Latino communities — asking officers to deal with the kid skateboarding recklessly in the park, the guys loitering on the corner — without criminalizing the people who live there?

Activists with the Black Lives Matter movement say no. They’ve called for an end to enforcing — or at least criminalizing — minor offenses.

Policing experts don’t go that far. But most today, as well as the Justice Department and President Barack Obama’s task force on policing , recommend that police embrace a broader notion of community policing, which requires officers to get to know the people they serve and respond more directly to their needs. While it didn’t specifically address Broken Windows policing, the task force noted that police should adopt policies that emphasize community engagement and trust.

That’s already happening in a few places.

In New York this month, the city council passed a bill requiring police to establish written guidance on how officers should use their discretion to enforce certain quality-of-life offenses, such as littering and unreasonable noise. It also allows officers to issue civil summonses to avoid routing people through the criminal justice system for minor offenses.

Cities like Milwaukee, Philadelphia and New Haven, Conn. have introduced foot patrols, which can allow officers to engage more closely with residents.

Portland , Ore. and Seattle — both cities under a reform agreement with the Justice Department — have placed a renewed emphasis on community policing, including encouraging officers to conduct foot patrols. In Seattle, overall approval ratings for the police have risen, although they remain stagnant with African-Americans. Last year, an independent assessment in Portland found that overall, 70 percent of residents said they would be treated fairly by police, but that African-Americans in particular remained concerned about discrimination and excessive force.

In Newark, Mayor Ras Baraka told FRONTLINE that the police department will return to what he called “neighborhood policing.” As part of the mandated reform process, officers are being re-trained, and given more accountability.

The goal is to have officers “who know people’s grandmothers, who know the institutions of the community, who look at people as human beings, right?” Baraka said. “And so that’s the beginning of it. If you don’t look at the people you are policing as human, then you begin to treat them inhumanely.”

Additional reporting by Anya Bourg and James Jacoby of FRONTLINE’s Enterprise Journalism Group.

Funding for the Enterprise Journalism Group is provided by the Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided by the Douglas Drane Family Fund.

Sarah Childress , Former Series Senior Editor , FRONTLINE

More stories.

‘A Dangerous Assignment’ Director and Reporter Discuss the Risks in Investigating the Powerful in Maduro’s Venezuela

‘It Would Have Been Easier To Look Away’: A Journalist’s Investigation Into Corruption in Maduro’s Venezuela

FRONTLINE's Reporting on Journalism Under Threat

Risks of Handcuffing Someone Facedown Long Known; People Die When Police Training Fails To Keep Up

Documenting police use of force, get our newsletter, follow frontline, frontline newsletter, we answer to no one but you.

You'll receive access to exclusive information and early alerts about our documentaries and investigations.

I'm already subscribed

The FRONTLINE Dispatch

Don't miss an episode. sign-up for the frontline dispatch newsletter., sign-up for the unresolved newsletter..

Fix broken windows, both the concept and on the subway

We must stop conflating broken windows policing with stop-and-frisk and zero tolerance.

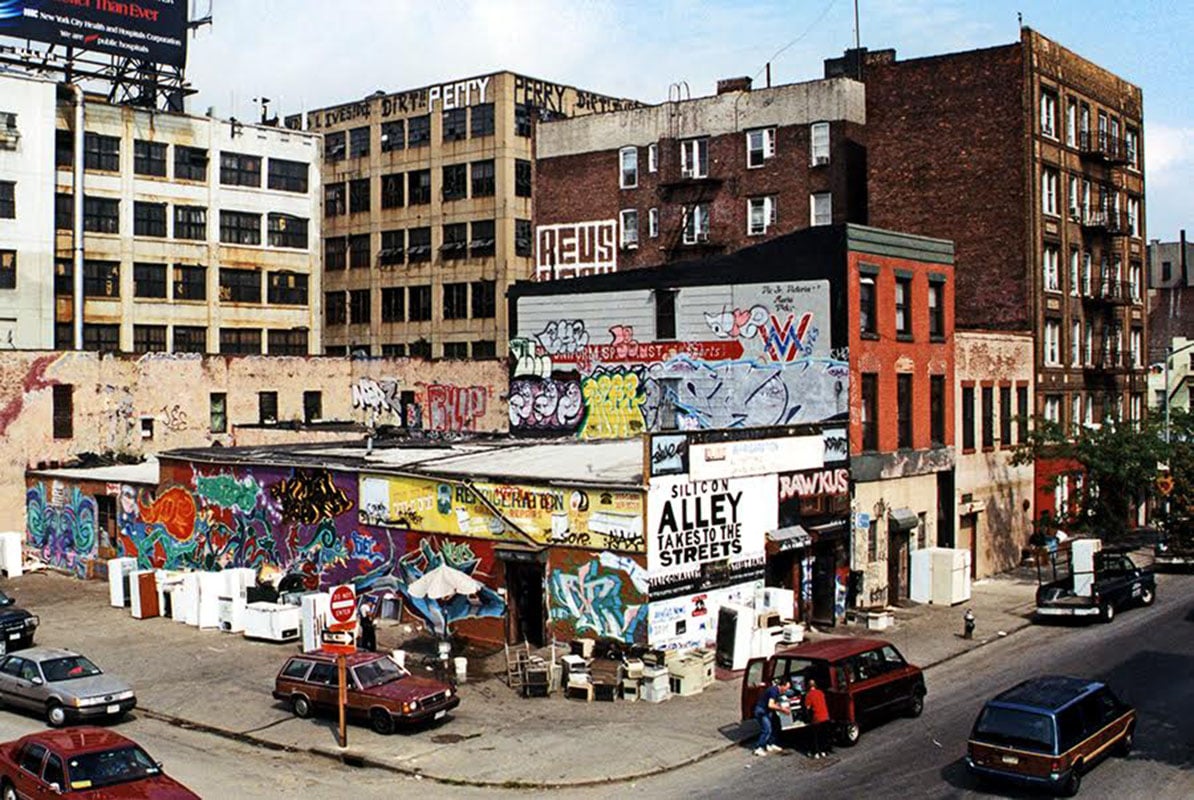

It’s no secret that in the 1970s through the 1990s, the New York City subway was seen as the poster child for urban decay.

This essay is reprinted with permission from the Violence Reduction Project

In September 2017, the Manhattan District Attorney’s office began to decline prosecution of fare evasion. The other New York City district attorneys followed suit. They also stopped prosecuting other rule violations and petty crimes in the subway. Having policed some of the largest transportation hubs in the nation and having spent five years of my career policing the subways, I knew that once disorder crept into a transportation system, the system will become less safe, causing riders to flee for other alternatives.

Unfortunately, I was right.

In 2018, crime in the subway increased . Whether from fear or a desire to avoid beggars, the homeless and the mentally ill, more riders shifted to other transportation modes, and ridesharing apps made this choice rather simple. Between 2017 and 2018, subway ridership decreased by about 3% . Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, when ridership is down 30%, crime is still up , and this despite the system being shut down for the first time in history, from 1 am to 5 am every night.

In addition to declining ridership, fare evasion costs the Transit Authority more than $200 million a year. This puts maintenance and capital projects on hold. This perfect storm of decline started with the decision to tolerate disorder and not prosecute low-level offenses.

The theory of broken windows, introduced by James Wilson and George Kelling in a 1982 Atlantic Monthly article, was never popular among a certain kind of reformer because, at its core, Wilson and Kelling believed in the positive possibility of policing, that good police could actually maintain order and prevent more serious crime. This conflicted with the “root causes” model, still accepted as faith in most of academia, that refuses to believe that crime reduction can come from anything except reductions in poverty, racism, unemployment and other social ills.

The power of Broken Windows theory

The fact that broken windows policing did reduce crime in New York City and elsewhere in the 1990s did little to mollify critics. And the cause of broken windows wasn’t helped when it morphed into stat-based Zero Tolerance policing in the 2000s in New York City.

Used correctly, broken windows is a powerful tool in a beat cop’s tool belt. And Kelling and Wilson envisioned it being used alongside another tool in that belt, police officer discretion. In 2016 I sat on a panel at Princeton University with George Kelling. During the question and answer session, Kelling asked the audience members who were critical of his theory if they had actually read the Atlantic Monthly article. Very few hands were raised.

Somewhere along the line, the theory of broken windows policing – the idea that enforcing low-level crimes such as fare evasion, graffiti and public drinking can prevent more serious crimes – was written off as harmful to low-income communities despite the fact that these communities most benefited from more public order and vastly less crime.

It’s no secret that in the 1970s through the 1990s, the New York City subway was seen as the poster child for urban decay. One just needs to watch Coming to America or The Warriors to see what Hollywood thought of the New York City subway. Crime was rampant, cars were covered with graffiti and filled with filth, and people literally put their lives on the line using it. In 1979, the system was averaging 250 felony crimes a week (about 13,000 that year) when Curtis Sliwa started the Guardian Angels to combat widespread violence on the system.

In 1984, Bernhard Goetz, who after being robbed three years earlier took to carrying a gun for protection to ride the subway, shot four Black teens who attempted to rob him. The majority of the public and New Yorkers initially supported Goetz .