Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, the complete guide to the ap comparative government and politics exam.

Advanced Placement (AP)

The AP Comparative Government and Politics exam tests your knowledge of how the political systems in different countries are similar and different. The exam requires endurance, strong critical thinking, and top-notch writing skills…which means you’ll need to be extra prepared!

If you’re looking for an AP Comparative Government study guide to carry you through all of your AP prep, look no further than this article! We’ll walk you through:

- The structure and format of the AP Government — Comparative exam

- The core themes and skills the exam tests you on

- The types of questions that show up on the exam and how to answer them (with sample responses from real AP students!)

- How the AP Comparative Government exam is scored, including official scoring rubrics

- Four essential tips for preparing for the AP Comparative Government exam

Are you ready? Let’s dive in!

Understanding how major world governments work will be key to doing well on this exam!

Exam Overview: How Is the AP Government — Comparative Exam Structured?

First things first: you may see this exam referred to as both the AP Government — Comparative exam or t he AP Comparative Government exam. Don't worry, though...both of these names refer to the same test!

Now that we've cleared that up, let's look at the structure of the test itself. The AP Comparative Government and Politics exam tests your knowledge of basic political concepts and your ability to compare political systems and processes in different countries.

This AP exam is on the shorter side, lasting for a total of two hours and 30 minutes . You’ll be required to answer 55 multiple-choice questions and four free-response questions during the exam.

The AP Comparative Government exam is broken down into two sections . Section I of the exam consists of 55 multiple-choice questions and lasts for one hour. The first section of the exam accounts for 50% of your overall exam score.

Section II of the AP Comparative Government exam consists of four free-response questions . On this part of the exam, you’ll be asked to provide open-ended, written responses to all four free-response questions. Section II lasts for one hour and 30 minutes and counts for 50% of your overall exam score .

To give you a clearer picture of how the AP Comparative Government exam is structured, we’ve broken the core exam elements down in the table below:

Source: The College Board

The AP Comparative Government and Politics exam tests you on a wide range of topics and skills that you need to really drive home before exam day. To help you prepare, we’ll go over the AP Comparative Government course themes, skills, and units next!

What’s on the AP Government — Comparative Exam? Course Themes, Skills, and Units

The AP Government — Comparative course teaches you the skills used by political scientists . To develop these skills during the course, you’ll explore content that falls into five big ideas that guide the course.

The five big ideas for AP Comparative Government are:

- Big Idea 1: Power and Authority

- Big Idea 2: Legitimacy and Stability

- Big Idea 3: Democratization

- Big Idea 4: Internal/External Forces

- Big Idea 5: Methods of Political Analysis

On the AP Comparative Government exam, you’ll show your mastery of the skills associated with these big ideas by answering questions that ask you to apply concepts, analyze data, compare countries, and write political science arguments.

The content and skills you’ll study throughout the AP Comparative Government course are divided out into five units of study . You’ll be tested on content from all five course units during the AP Comparative Government exam. Getting familiar with what each unit covers and how those topics are weighted in your overall exam score will help you get prepared for exam day!

You can view each course unit, the topics they cover, and how they’re weighted in your exam score below:

Now that you know what’s on the AP Comparative Government exam, let’s break down the two sections of the exam even further. We’ll look at Section I and Section II of the AP Comparative Government exam next!

AP Comparative Government Exam: Section I

The first section of the exam tests your ability to describe, explain, compare, and analyze political concepts and processes, various forms of data, and text passages. You’ll be asked to demonstrate these skills by answering both individual and sets of multiple-choice questions.

Section I consists of 55 multiple-choice questions, lasts for one hour, and counts for 50% of your exam score.

Here’s a breakdown of how each skill is assessed on the multiple-choice section of the exam:

- Approximately 40–55% of multiple-choice questions assess students’ ability to apply political concepts and processes in hypothetical and authentic contexts.

- Approximately 25–32% of multiple-choice questions will assess students’ ability to compare the political concepts and processes of China, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, Russia, and the United Kingdom.

- Approximately 10–16% of multiple-choice questions will assess students’ ability to analyze and interpret quantitative data represented in tables, charts, graphs, maps, and infographics

- Approximately 9–11% of multiple-choice questions will assess students’ ability to read, analyze, and interpret text-based sources.

To help you get a better idea of what the multiple-choice questions are like on this part of the AP Comparative Government exam, let’s look at a sample question and how it’s scored next .

Sample Question: Multiple-Choice

Looking at sample multiple-choice questions can help you grasp the connection between what you learn in the AP Comparative Government course and what you’ll be tested on during the exam.

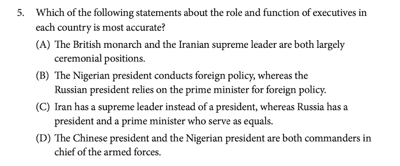

The individual multiple-choice question below comes from the College Board’s official guide to AP Comparative Government and Politics .

The multiple-choice question above asks you to compare two or more countries based on their political systems and behaviors. It draws on your knowledge of Big Idea #1: Power and Authority because it asks about the role of government executives in different countries . You’ll focus on these concepts during Unit 2 of your AP Comparative Government course, which explores political institutions in different countries.

The correct answer to this multiple-choice question is D : “The Chinese president and the Nigerian president are both commanders in chief of the armed forces.”

AP Comparative Government Exam: Section II

Like Section I, the second section of the exam tests your ability to describe, explain, compare, and analyze political concepts and processes, various forms of data, and text passages. In this section, you’ll be asked to demonstrate these skills by providing written responses .

Section II consists of four free-response questions, lasts for one hour and 30 minutes, and counts for 50% of your exam score.

There are four different types of free-response questions on the exam, and each one tests your reading and writing skills in different ways. Here’s a breakdown of what you’ll be asked to do on each free-response question on the exam:

- 1 conceptual analysis question: You’ll define or describe a political concept and/or compare political systems, principles, institutions, processes, policies, or behaviors.

- 1 quantitative analysis question: You’ll analyze data to find patterns and trends and reach a conclusion.

- 1 comparative analysis question: You’ll compare political concepts, systems, institutions, processes, or policies in two of the course countries.

- 1 argument essay: You’ll write an evidence-based essay supporting a claim or thesis.

To help you get a better sense of what the free-response questions are like on this part of the AP Comparative Government exam, let’s look at an example of each type of question and how it’s scored next .

Sample Question: Conceptual Analysis Free-Response

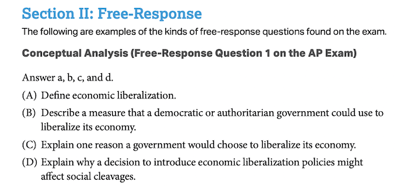

The free-response question below is taken from the College Board’s official guide to AP Comparative Government and Politics . This sample question is an example of a conceptual analysis question. This is the first type of question that you’ll encounter on the exam.

On the real exam, you’ll have 10 minutes to answer the conceptual analysis question . Check out the question below:

To understand how to answer this question correctly, we’ll need to look at how conceptual analysis questions are scored on the exam. The scoring rubric below shows how your response to this question would be evaluated after the exam:

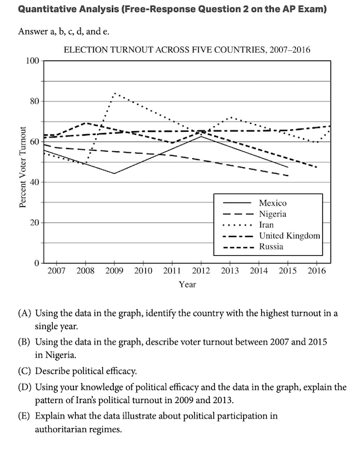

Sample Question: Quantitative Analysis Free-Response

The Quantitative Analysis free-response question gives you quantitative data in the form of a graph, table, map, or infographic. You’ll be asked to describe, draw a conclusion, or explain that data and its connections to key course concepts.

The quantitative analysis question is the second question you’ll encounter on the exam. It’s worth five raw points of your score on this section of the exam, and you should spend about 20 minutes answering this question.

The quantitative analysis question below comes from the College Board’s official guide to AP Comparative Government and Politics :

To get a better idea of how to answer this question, let’s look at the scoring rubric that’s used to evaluate this quantitative analysis question on the exam:

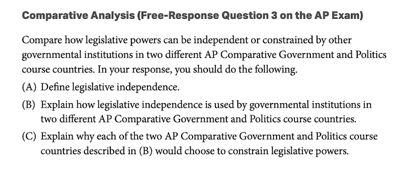

Sample Question: Comparative Analysis Free-Response

The Comparative Analysis free-response question assesses your ability to define, describe, compare, or explain political concepts, systems, institutions, or policies in different countries. This question is the third free-response question that you’ll answer on the exam.

The Comparative Analysis question is worth five raw points of your score on this section of the exam, and you should spend about 20 minutes answering this question.

The comparative analysis question below comes from the College Board’s official guide to AP Comparative Government and Politics :

We can take a look at the scoring rubric that’s used to evaluate this type of free-response question to get a better idea of what types of responses will earn you full points:

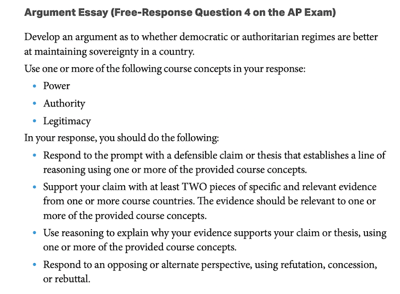

Sample Question: Argument Essay Free-Response

The fourth and final free-response question you’ll encounter on the exam is the Argument Essay question. This free-response question assesses your ability to make a claim that responds to the question, defend and support your claim with reasonable evidence, and respond to an opposing view on the topic at hand.

The Argument Essay question is worth five raw points, and it’s recommended that you spend about 40 minutes answering this question.

The argument essay question below comes from the College Board’s official guide to AP Comparative Government and Politics :

To understand what an effective response to this question looks like, we’ll need to think about how argument essay questions are scored on the exam.

The scoring rubric for this free-response question is quite long; you’ll find four separate categories for evaluation in the rubric below , as well as examples of responses that will earn you full points in each category.

The scoring rubric below shows how your response to this question will be evaluated:

How Is the AP Comparative Government Exam Scored?

Before you take the AP Comparative Government exam, you need to know how your responses will be scored. Here, we’ll explain how each section of the AP Comparative Government exam is scored, scaled, and combined to produce your final score on the AP 1-5 scale .

As a quick reminder, here’s how the score percentages breakdown on the exam:

- Section I: Multiple-choice: 55 questions, 50% of overall score

- Section II: Free-response: four questions, 50% of overall score

- Question 1: Conceptual Analysis: 11%

- Question 2: Quantitative Analysis: 12.5%

- Question 3: Comparative Analysis: 12.5%

- Question 4: Argument Essay: 14%

On the multiple-choice section, you’ll earn one raw point for each question you answer correctly. The maximum number of raw points you can earn on the multiple-choice section is 55 points. You won’t lose any points for incorrect answers!

The free-response questions are scored differently. The Conceptual Analysis question is worth four raw points, and the Quantitative Analysis, Comparative Analysis, and Argument Essay questions are each worth five raw points. Collectively, there are a total of 19 raw points you can earn on the free-response section .

Remember: you’ll only lose points on free-response questions for big errors , like providing an incorrect definition or failing to justify your reasoning. While you should use proper grammar and punctuation, you won’t be docked points for minor errors as long as your responses are clear and easy to understand.

You can earn 74 raw points on the AP Comparative Government exam. Here’s how those points are parsed out by section:

- 55 points for multiple-choice

- 19 points for free-response

After your raw scores have been tallied, the College Board will convert your raw score into a scaled score of 1-5 . When you receive your score report, that 1-5 scaled score is the one you’ll see.

The 5 rate for the AP Comparative Government exam is fairly middle-of-the-road in comparison to other AP exams . Take a look at the table below to see what percentage of test takers earned each possible scaled score on the 2021 AP Comparative Government exam:

4 Top Tips for Prepping for the AP Comparative Government and Politics Exam

If the AP Comparative Government exam is right around the corner for you, you’re probably thinking about how to prepare! We’re here to help you with that. C heck out our four best tips for studying for the AP Comparative Government exam !

Tip 1: Start With a Practice Exam

One of the best ways to set yourself up for successful AP exam prep is to take a practice exam. Taking a practice AP Comparative Government exam before you really start studying can help you design a study routine that best suits your needs.

When you take a practice exam before diving into your study regimen, you get the chance to identify your strengths and weaknesses. Identifying your weaknesses early on in your exam prep will help you tailor your study time to eliminating your weaknesses (which translates to earning more points on the exam!).

We recommend taking a full practice exam in the time frame you’ll be allotted on the real exam. This will help you get a real sense of what the timing will feel like on exam day! After you take the practice exam, sit down and evaluate your results. Make note of the questions you missed, the skills those questions assess, and the course content they reference. You can then design a study routine that targets those tougher areas–and give yourself a better chance of earning full exam points in the process!

Tip 2: Create Your Own Cram Sheet

Everyone needs quality study materials in order to prepare well for AP exams. But did you know that creating your own study materials is a great way to help you remember tough material? Creating your own AP Comparative Government cram sheet is a great way to review course concepts and themes and organize your understanding of the material you’ll be tested over later.

You can look up AP Comparative Government cram sheets online and design yours in a similar way…or you can take some time to consider your needs as a learner and test-taker, then design a cram sheet that’s tailor-made for you.

On your cram sheet, you’ll likely want to include course concepts, issues, and questions that pop up on homework, quizzes, and tests that you take in your AP Comparative Government class. From there, you can supplement your cram sheet with info you learn from practice exams, sample free-response questions, and official scoring rubrics. You can work on memorizing that material, or simply use it to organize your study routine!

Tip 3: Practice Free-Response Questions

Free-response questions on AP exams are notoriously difficult, and the AP Government Comparative free-response questions are no different. Writing-based questions can be intimidating for any test-taker, so it’s important to practice free-response questions before the exam.

The College Board provides an archive of past official free-response questions on their website . You can use these to practice and study! Any free-response questions your teacher gives you in class are fair game as well. When you practice free-response questions, remember to stick to the timing you’ll be given on the real exam, and use official scoring rubrics to evaluate your responses. Doing these things will help you get used to what free-response questions will feel like on the real exam!

Tip 4: Take Another Practice Exam

As you wrap up your exam prep and exam day nears, consider taking another practice exam. You can compare your results on your second practice exam to your results on the practice exam that you took before you started studying. You’ll get to see how much you’ve improved over time!

Taking a final practice exam a few weeks before exam day can also help you revamp your exam prep. You can use your exam results to focus your final study time on any remaining struggle areas you’re encountering. Also, your score on your final practice exam can help you get an idea of what you’re likely to score on the real exam. Having this knowledge going into test day can calm your nerves and give you confidence, which are both essential to success on the AP Comparative Government exam!

What's Next?

If you're taking AP Comparative Government, you're probably thinking about taking more AP classes during high school. Here's a list of the hardest AP classes and tests for you.

Wondering how your AP Comparative Government score stacks up to the competition? Here's a list of the average AP scores for every exam to help you figure out.

If you want to get a 5 on your AP exams, you'll need a study plan. Our five-step AP study plan will help you study smarter and boost your scores.

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Comparative Politics

One of the central themes of comparative politics is the study of political institutions, including constitutions, electoral systems, legislatures, judiciaries, and bureaucracies. Comparative analysis of political institutions can reveal the strengths and weaknesses of different governance systems, as well as the conditions that promote or hinder effective decision-making and democratic participation. For example, the comparison of electoral systems across different countries can provide insights into the ways in which electoral rules affect voter behavior, party competition, and representation.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, comparative politics research paper topics.

- The impact of different electoral systems on party systems

- The role of civil society in promoting democratic norms and practices

- Comparative analysis of the welfare state in advanced industrial democracies

- The effect of gender quotas on political representation

- Comparative study of judicial activism and judicial restraint in different legal systems

- The relationship between economic development and political liberalization

- The role of political culture in shaping democratic consolidation

- The impact of decentralization on political power and accountability

- The politics of immigration and border control in different countries

- Comparative analysis of public opinion and political behavior in different societies

- The role of the media in shaping political opinion and decision-making

- The impact of globalization on state sovereignty and power

- Comparative study of civil-military relations in different societies

- The relationship between natural resources and political stability

- The impact of international organizations on domestic politics

- Comparative analysis of federalism and unitary states

- The role of interest groups in shaping policy outcomes

- The impact of constitutional design on political stability and democratic consolidation

- Comparative study of party systems in new democracies

- The relationship between corruption and economic development

- Comparative analysis of populist movements and parties

- The role of religion in shaping political behavior and attitudes

- The impact of demographic change on politics and policy

- Comparative study of authoritarian regimes and their stability

- The impact of regime change on economic development and political stability

- Comparative analysis of social movements and political change

- The role of identity politics in shaping political outcomes

- The impact of colonial legacies on contemporary politics

- Comparative study of labor relations in different societies

- The impact of environmental policy on political outcomes

- Comparative analysis of the role of the state in economic development

- The impact of trade agreements on domestic politics and policy

- Comparative study of regional integration and its effects on politics and policy

- The role of civil conflict in shaping political outcomes

- The impact of digital technologies on political communication and decision-making

- Comparative analysis of the relationship between democracy and development

- The impact of immigration on political attitudes and behavior

- Comparative study of the politics of welfare reform in different societies

- The role of international norms and values in shaping domestic politics and policy

- Comparative analysis of the politics of energy policy

- The impact of social media on political mobilization and participation

- Comparative study of political parties and their strategies for gaining and maintaining power

- The impact of globalization on income inequality and political conflict

- Comparative analysis of the politics of trade and protectionism

- The role of ethnic and linguistic diversity in shaping political outcomes

- Comparative study of the role of women in politics and policy-making

- The impact of digital surveillance on civil liberties and political participation

- Comparative analysis of the politics of climate change

- The role of education in shaping political attitudes and behavior

- Comparative study of the politics of healthcare reform in different societies.

Another key theme of comparative politics is the study of political culture and ideology. Political culture refers to the attitudes, values, and beliefs that shape political behavior and institutions, while ideology is a set of beliefs and principles that guide political action. Comparative analysis of political culture and ideology can reveal the sources of political conflict, the roots of political stability, and the factors that influence political change. For example, the comparison of the political cultures of liberal democracies and authoritarian regimes can help us understand the role of civic values and civil society in promoting democratic norms and practices.

A third important theme of comparative politics is the study of political economy, which explores the relationship between politics and economics. Comparative analysis of political economy can reveal the ways in which economic structures and processes influence political decision-making and outcomes, as well as the ways in which political institutions and actors shape economic development and growth. For example, the comparison of economic policies across different countries can provide insights into the conditions that promote or hinder economic growth, and the role of state intervention in economic affairs.

Finally, comparative politics also explores the dynamics of power and conflict within and between political systems. This theme encompasses the study of political parties, interest groups, social movements, and other political actors, as well as the causes and consequences of political violence and conflict. Comparative analysis of power and conflict can reveal the sources of political legitimacy, the strategies used by political actors to gain and maintain power, and the factors that contribute to political instability and violence. For example, the comparison of ethnic and religious conflict across different countries can help us understand the role of identity politics in shaping political outcomes.

In conclusion, comparative politics is a vital subfield of political science that helps us understand and explain the similarities and differences between political systems and their structures, processes, and actors. By examining political institutions, culture and ideology, political economy, and power and conflict, comparative politics sheds light on the conditions that promote or hinder effective governance, democratic participation, and economic growth, as well as the factors that contribute to political instability and conflict. As the world becomes increasingly interconnected and complex, the study of comparative politics is more important than ever in helping us navigate the challenges and opportunities of the global political landscape.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Comparative Politics Made Simple

Making comparisons.

Most people are subliminal comparativists; others make comparisons their vocation. If you made a decision this morning concerning what to eat, what to wear, and how you should get to work or school, chances are you did so by considering alternatives and choosing the one, for whatever reason, that “made sense” (cereal and milk or eggs and toast? Jeans and t-shirt or suit? Scenic country road or freeway?). You engage in this listing of and picking among alternatives every day, sometimes consciously but often less so. Some decisions you make quickly; for others you insist on taking your time, usually to think through the consequences of each option, before choosing the one that is “best” (that is, the one that is likely to meet your goal with the least possible adverse consequences or costs). To decide is to compare, and most of us decide (and therefore compare) all the time.

Comparative politics is about classifying, comparing, and sometimes even choosing, except that the “things” that are of interest to comparative politics specialists are the really big ones: states, societies, ideologies, political systems, countries, regions, time periods, worlds, and so on. At its most basic, then, comparative politics is a method of study (by comparison) and a field of study (of macrosocial and political phenomena). Comparativists are interested in these phenomena not for their own sake (that’s the job of area studies specialists) but rather for the purpose of drawing attention to similarities and differences — especially the latter, of understanding why things are the way they are in one locale but not another — and of comparing and evaluating realities (for example, public policies).

Looking at Specific Country Examples

A comparativist might observe that the United States’ health-care system is funded mainly by private sources, while the United Kingdom’s system is funded by government (through the National Health Service, or NHS). She further notices that in the U.K. health care is guaranteed to all. But she also notes that those Americans with health insurance have an easier time receiving certain medical procedures (kidney dialysis and transplants, triple-bypass heart surgeries) than their counterparts across the Atlantic. All of the aforementioned differences between the U.S. and U.K. health-care systems are, in and of themselves, interesting, but you probably want to know more, such as why the two countries’ health-care systems are different, and which one is “better.”

Our comparativist is like you, so she investigates. She is not likely to confine herself to health care in the U.S. and the U.K. (her dependent variable): she will focus on other issues that she thinks might have caused health-care systems between the two countries to be so different. These factors (independent variables) would likely include U.S. and U.K. history, geography, demography, economy, political institutions, interest groups, and citizen attitude toward government and the private sector.

She spends hours reading about many possible factors: the insular history of the U.S. and the empire-making history of the U.K. (which favored the formation of a healthy army and civil servants who could be dispatched around the world); the virtual absence of socialist ideology in the mainstream of American politics and the existence of Fabian socialist ideology in the U.K.; the division of policy making between separate, if not to say competing, branches of government in the United States and the fusion of executive and parliamentary powers in the U.K. (which makes for less contention in policy making and implementation); and, above all, her own survey, which indicates that Britons trust government more than Americans do. Our comparativist may now feel that she knows why the health-care systems are different, and may conclude that, although these differences have many causes, one seems to be stronger than all the others: Britons trust government more than Americans. (In some studies comparativists are able to measure, together and separately, the effects of each independent variable, or cause, on the dependent variable, the effect. Even when they cannot do this, they can make plausible arguments about causes and effects.)

What has our comparativist done thus far, and how? First, she observes a “problem” or “case.” Second, she investigates its cause(s). In the process, she reads extensively about not only the health-care systems in the two countries but also their history, political systems, and so forth. The knowledge gained is supplied by secondary sources (for example, the internet, books, or journal articles). To find out about public attitudes toward government and the private sector, the comparativist decides to do a survey. Information supplied by this survey may be said to have come from primary sources . The comparativist therefore uses two types of sources to gather facts, which she analyzes meticulously to make a case as to why health-care systems in the U.S. and the U.K. are different. But she may go even further than that, based on what she has learned from her study. She may conclude that, given the evidence, one country has a “better” health-care system than the other. Here, however, she would be expressing a preference: her research would thus have a normative (or value-based) dimension, not just a positive (value-neutral or empirical) one. Furthermore, she may develop a theory , which is a general statement intended to explain or account for a given phenomenon, about health-care systems: citizen trust in government is the reason why countries have government-funded health-care systems.

National and Global Contexts

The terms in bold are at the heart of comparative politics. The U.S. and the U.K. are countries, or, in comparative politics language, nation-states . A nation-state is a large group of people who share (a) the characteristics of history, language, religion, ethnicity, race, political and economic values, and so forth; (b) occupy the same (usually contiguous) territory; and (c) have a government that they recognize as “theirs,” which makes laws and regulations and is expected to defend them in case of an attack by another government. Few countries neatly fit this definition. The U.S., for example, has many ethnic groups and religions. Perhaps a better concept than nation-state is a national state, in which a large group of people living under one authority (or state) have come together to forge a common or national identity, regardless of other things that may separate them. Nation-states are usually the units of analysis in comparative research, but comparativists can focus on almost anything. A unit of analysis is the main object or actor in an argument, hypothesis, or theoretical framework. It is different from the levels of analysis , which are the primary analytical focus of the researcher, which in our example would be American and British health-care systems or policies.

Nevertheless, comparativists almost never ignore certain macrosocial factors, even when they are not their primary focus of study. These would include the economy , which is whatever arrangement people make to produce and trade the goods and services that they think they need to survive, or otherwise make money; the state , which is the centralized authority that rules over a territory thanks to its monopolistic ownership of force (armies, police, militias, etc.); and political institutions , or the means by which state power is organized. Macrosocial factors also include ideology , or the worldview by which people make sense of reality and, at the same time, serves as a guide for them to do what is “right”; culture , which is the purported collective experience, characteristics, and orientation of a large group of people (closely related to ideology, but not the same: ideology is a cognitive road map usually produced by elites [intellectuals no less], and culture is how people actually live); civil society , which refers to nonstate organizations that people voluntarily join, usually to defend their interests against the state or express themselves peacefully and nonpolitically (political parties, labor unions, Girl Scouts, etc.); and, finally, the international environment , which refers to actors external to the typical units of analysis (nation-states) of comparativists.

The international environment is composed of other nation-states or countries, multinational, government-sanctioned institutions , which are institutions created by many nation-states to address matters of common concern (for example, the United Nations); multinational, privately owned corporations , which are profit-seeking business organizations that operate in more than one country (for example Wal-Mart); and international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs), which are non-profit-seeking organizations that operate on a charity basis and deliver services to the poor and needy across countries (such as Doctors Without Borders). INGOS also serve as advocates when they do not provide services (for example, Amnesty International).

You can pick almost any book on comparative politics and you will find at least a mention of the concepts defined above. Sometimes one is the focus of comparison in a two-country study, as when comparativists study political parties in the U.S. and Italy. Sometimes they are bundled with others in a multicountry study, as when comparativists study democracy and economic development all over the world. The relative weight of specific concepts as explanatory variables in the analysis of comparativists largely determines the “school” to which they may be said to belong.

Schools of Analysis

Three of the most prominent schools in comparative politics in the past 50 years have been political economy , modernization theory , and dependency theory . They are chosen here only to give you an idea of the sharply different perspectives that exist in comparative politics. The political economy approach emphasizes, as its name suggests, the nexus between economy and politics. A classic case is Robert Bates’s States and Markets in Tropical Africa: The Political Basis of Agricultural Policy (University of California Press, 1981), in which the author examines how state economic policy in Africa, especially in agriculture, undermines development, and why policy continues in light of failure. Political economy, in turn, is composed of subschools, among them rational choice theory, which attempts to use (neoclassical) economic reasoning to explain collective decisions.

Like political economy, modernization theory focuses on domestic forces, but its concern is more about how certain cultural aspects that retard development may be overcome. Modernization theory generally divides society between a “modern” sector and a “backward” sector. The challenge of development is how to overcome the latter. In addition, modernization theory tends to emphasize culture rather than the political economy, which it sees as a dependent variable to be acted upon. Still, the units of analysis in both schools are nation-states, and their levels of analysis, although different, are internal to the units. 1

The same cannot be said of dependency theory, for which the global system, not nation-states, is the focus of analysis. In dependency theory, poverty is due to neither so-called backward culture nor deleterious state actions in the political economy but rather the global system itself: a relatively small number of “core” countries specialize in high-value-added manufactured goods, while a large number of “peripheral” countries specialize in primary commodity production. Thus poverty in dependency theory stems from the position countries occupy in the international division of labor or system.

To conclude, comparative politics is about serious issues: war and peace, democracy and authoritarianism, market-based and state-based economies, prosperity and poverty, health-care coverage, and so on. However, its raison d’être is quite simple: the world is diverse, not monolithic. Furthermore, the world is getting smaller, literally and figuratively. Given the tremendous diversity that exists on our planet, and the fact that no one country is “better” than all the others on every count, there is always room for learning. Furthermore, knowledge is a precondition for success in an interdependent – less isolated, more interconnected, and therefore “smaller” – world. How can we relate to another country if we know nothing about its institutions, culture, or history? The job of the comparativist researcher is to make comparisons less subliminal and random, and more deliberate and systematic, especially in the things that are critical to human life.

1. I am simplifying somewhat here. Allowance should be made for international political economy, which emphasizes the role of external forces in the politics of countries. Also, modernization theory stresses the demonstration effect that “modern” countries have on their nonmodern cousins.

Authored by

Jean-Germain Gros University of Missouri-St. Louis St. Louis, Missouri,

AP Comparative Government and Politics

Learn all about the course and exam. Already enrolled? Join your class in My AP.

Not a Student?

Go to AP Central for resources for teachers, administrators, and coordinators.

About the Exam

The AP Comparative Government and Politics Exam will test your understanding of the political concepts covered in the course units, including your ability to compare political institutions and processes in different countries.

Wed, May 8, 2024

12 PM Local

AP Comparative Government and Politics Exam

This is the regularly scheduled date for the AP Comparative Government and Politics Exam.

Exam Components

Section 1: multiple choice.

55 questions 1hr 50% of Score

The multiple-choice section includes individual, single questions as well as sets of questions. Questions focus on the core countries of the course: China, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, Russia, and the United Kingdom. You’ll be asked to:

- Describe, explain, and compare political concepts and processes

- Compare political concepts and processes of the course countries

- Analyze data in graphs, charts, table, maps, or infographics

- Read and analyze text passages

Section 2: Free Response

4 questions 1hr 30mins 50% of Score

In the free-response section, you’ll respond to four questions with written answers. The section includes:

- 1 conceptual analysis question: You’ll define or describe a political concept and/or compare political systems, principles, institutions, processes, policies, or behaviors.

- 1 quantitative analysis question: You’ll analyze data to find patterns and trends and reach a conclusion.

- 1 comparative analysis question: You’ll compare political concepts, systems, institutions, processes, or policies in two of the course countries.

- 1 argument essay: You’ll write an evidence-based essay supporting a claim or thesis.

Exam Essentials

Exam preparation, ap classroom resources.

Once you join your AP class section online, you’ll be able to access AP Daily videos, any assignments from your teacher, and your assignment results in AP Classroom. Sign in to access them.

- Go to AP Classroom

AP Comparative Government and Politics Course and Exam Description

This is the core document for the course. It clearly lays out the course content and describes the exam and the AP Program in general.

Free-Response Questions and Scoring Information

Go to the Exam Questions and Scoring Information section of the AP Comparative Government and Politics exam page on AP Central to review the latest released free-response questions and scoring information.

Past Exam Free-Response Questions and Scoring Information

Go to AP Central to review AP Comparative Government and Politics free-response questions and scoring information from past years.

Services for Students with Disabilities

Students with documented disabilities may be eligible for accommodations for the through-course assessment and the end-of-course exam. If you’re using assistive technology and need help accessing the PDFs in this section in another format, contact Services for Students with Disabilities at 212-713-8333 or by email at [email protected] . For information about taking AP Exams, or other College Board assessments, with accommodations, visit the Services for Students with Disabilities website.

Credit and Placement

Search AP Credit Policies

Find colleges that grant credit and/or placement for AP Exam scores in this and other AP courses.

Additional Information

POLS 330: Topics in Comparative Politics (HC)

Women and peace keeping, introduction.

- Background Information

- Journal Articles

- Relevant Books

- Reports, Research Groups & Data

- Accessing Resources

- Starting the Senior Thesis in Political Science

- Haverford Political Science Theses

- Search Tips

A UNAMID peacekeeper speaks with a woman in a refugee camp in Dafur, Sept. 2018 (Source: flickr - Setyo Budi (UNAMID)

This guide focuses on the topics in your course and outlines research strategies and resources for the work you are doing. Use the searches and linked examples as jumping off points for exploration.

Use the Background page to help in developing research questions and understanding the broader context for your specific topics. Journal Articles and Books will give you material for analysis and comparison. Further, more specific types of resources are outlined in the pages for Reports, Research Groups & Data and News .

- Next: Background Information >>

- Last Updated: Jan 19, 2024 4:42 PM

- URL: https://guides.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/comppol

- Comprehensive Exams

- American Politics

- Political Theory

- International Relations

- Research Methods and Formal Theory

Comparative Politics

The Comparative Politics Qualifying Exam will be offered on two consecutive days in June, according to the department’s schedule for exams. Students will be asked to answer a total of two questions: each answer should be between 15 and 25 pages in length including footnotes but not bibliography, diagrams, or tables.

Students will need mastery of the Comparative Politics Core List and one topic of their choice. Current choices are: Comparative Political Economy, Ideology and Culture, Institutions, Nations and Nationalism, Order and Violence, or Political Regimes and Transitions. The exam will take place over two days. At the start of each day, the student will be given the questions for that day’s segments (via email); students will answer one question from two or more options. Completed answers should be returned to the exam administrator eight hours later. (Answers should be returned as .doc or .pdf file.) Essays should be type-written, double-spaced, in 12point font. While students are free to consult any written source, the text of the exam should be original. Although some copying or cutting and pasting of material that has been previously prepared will be permitted, standard rules of plagiarism apply.

On each day of the exam, students are asked to write an essay in response to one of three questions. Day 1 covers the Core CP list, and Day 2 the specialized list you have chosen. To the best of your ability, choose your questions and craft your answers so that, between the two essays, you display a broad and deep understanding of the literature. Avoid using content in the second essay that you have already covered in your first essay.

Each answer will be read by the two faculty members in comparative politics. Students may receive “pass,” “not pass,” or (rarely) “high pass” on the exam. In accordance with departmental policy, students who do not pass the exam in their first attempt may retake the exam at a subsequent date. If a student fails to pass the entire exam in two attempts, their retention in the PhD program will be under review.

Students who wish to take the Comparative qualifying exam should consult with relevant faculty advisors about choosing among the topical lists. Students will be responsible for the Core List and one topical list.

Books and Book Chapters

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism . New York: Verso.

Cox, Gary W. 1997. Making Votes Count: Strategic Coordination in the World's Electoral Systems . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dahl, Robert. 1972 . Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition . New Haven: Yale University Press.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1968. Political Order in Changing Societies . New Haven: Yale University Press. Chapters 1, 4, 5, 6.

Kalyvas, Stathis. 2006. The Logic of Violence in Civil War . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lijphart, Arend. 2012. Patterns of Democracy . New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lipson, Seymour Martin, and Stein Rokkan. 1967. “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignment” in Party systems and voter alignments: cross-national perspectives . New York: Free Press .

Mill, John S. 2011 . A System of Logic: Ratiocinative and Inductive . New York: Harper & Brothers. Chapter 8, Volume I.

Moore, Barrington. 1966. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World . Boston: Beacon Press. Chapters 1, 2, 4, 5, 7-9.

Olson, Mancur. 1965. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups . Boston: Harvard University Press.

Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. London: Cambridge University Press.

Przeworski, Adam, et al. 2000. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World 1950-1990. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Putnam, Robert. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Scott, James C. 1985 . Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance . Bethany, Connecticut: Brevis Press.

Weber, Max. 1930 . The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism . New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Weber, Max. 2013. From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology . Hoboken: Routledge. Read pp. 77-83 (excerpt from “Politics as a Vocation”).

Weber, Max. 1968. “The Nature of Charismatic Authority and Its Routinization” and “The Pure Types of Legitimate Authority.” Both from The Theory of Social and Economic Organization .” In Max Weber on Charisma and Institution Building , pp. 46-65.

Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson. “A Theory of Political Transitions” American Economic Review 91, no. 4 (2001): 938-963

Fearon, James D., and David D. Laitin. “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War.” American Political Science Review 97, no. 1 (2003): 75-90.

Geertz, Clifford. “Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture.” Readings in the philosophy of social science , (1994): 213-231.

Peter Gourevitch. “The Second Image Reversed: The International Sources of Domestic Politics.” International Organization 32, no. 4 (1978): 881-912.

Lipset, Seymour Martin. "Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy." American Political Science Review 53, no. 1 (1959): 69-105.

North, Douglass C. and Barry R. Weingast. “Constitutions and Commitment: The Evolution of Institutions Governing Public Choice in Seventeenth-Century England.” The Journal of Economic History Vol. 49, No. 4 (1989): 803-832.

Schmitter, Philippe C. “Still the Century of Corporatism?” Review of Politics 36, no. 1 (1974): 85-131.

1. Thorstein Veblen- Absentee Ownership and Business Enterprise in Recent Times: The Case of America . Transaction Publishers; Revised ed. edition (January 1, 1997)

a. Thorstein Veblen, Theory of Business Enterprise

2. John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936)

3. Joseph A Schumpeter , Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (NY: Harper Torchbooks)

4. Karl Polanyi- The Great Transformation (Beacon Press)

5. Friedrich von Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (Chicago, 1944)

6. George Stigler, (ed) Chicago Studies in Political Economy ( University of Chicago Press)

a. Ludwig Von Mises, Liberalism, The Classical Tradition , (Liberty Press)

b. Ronald Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost,” Journal of Law and Economics 3 (October 1960)

7. Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom

8. Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics (Picador)

9. Andrew Shonfield, 1965, Modern Capitalism: The Changing Balance Between Public and Private Power (Oxford)

10. Michal Kalecki, “Political Aspects of Full Employment”

11. Hyman Minsky, 1986, Stabilizing and Unstable Economy (MS Sharpe)

12. Michel Aglietta, 1979, A Theory of Capitalist Regulation (Verso)

a. Michel Aglietta, (1998). “Capitalism at the turn of the century: regulation theory and the challenge of social change”. New Left Review . Pp 41-90

13. Raghuram G. Rajan and Luigi Zingales, 2004, Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists: Unleashing the Power of Financial Markets to Create Wealth and Spread Opportunity , (Princeton N.J.: Princeton University Press)

14. Peter Hall & David Soskice, eds., 2001, Varieties of Capitalism , (Oxford)

15. Greta Krippner, 2012, Capitalizing on Crisis: The Political Origins of the Rise of Finance (Harvard University Press)

a. Natascha van der Zwaan, 2014: “Making Sense of Financialization”. In: Socio-Economic Review 12(1), 99–129.

16. Mark Blyth. (2002). Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

a. Mark Blyth, 2015, Austerity. History of a Dangerous Idea (Oxford)

17. Gøsta Esping-Andersen, 1990, The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (Princeton)

18. Evelyn Huber and John Stephens, Development and Crisis of the Welfare State: Parties and Policies in Global Markets . University of Chicago Press, 2001

19. T.H. Marshall, 1992, Citizenship and Social Class (London: Pluto Press)

20. Maurizio Ferrera, The Boundaries of Welfare: European Integration and the New Spatial Politics of Social Solidarity (Oxford University Press 2006)

21. Anton Hemerijck, 2014, Changing Welfare States (Oxford University Press, 2013)

22. Monica Prasad, 2012, The Land of Too Much: American Abundance and the Paradox of Poverty (Harvard University Press)

23. Kathleen Thelen, 2014, Varieties of Liberalization: The New Politics of Social Solidarity. (New York: Cambridge University Press)

a. Peer Hull Kristensen; Kari Lilja; Eli Moen; Glenn Morgan, 2016/ Nordic Countries as Laboratories for Transnational Learning In: Nordic Cooperation: A European Region in Transition, ed. /Johan Strang. Abingdon: Routledge p. 183-204 (Global Order Studies, Vol. 8)

24. Streeck, W. (2014) Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism , (New York, Verso)

25. Klaus Dörre, /Lessenich, Stephan/Rosa, Hartmut (2015): Sociology, Capitalism, Critique . London/New York: Verso.

26. Lucio Baccaro, & Chris Howell (2017): Trajectories of Neoliberal Transformation: European Industrial Relations since the 1970s. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

a. Lucio Baccaro & Jonas Pontusson, 2016, “Rethinking Comparative Political Economy: The Comparative Growth Model Perspective”, Politics & Society 2016, Vol. 44(2) 175–207

Louis Althusser, On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses , translated by G. M. Goshgarian (New York: Verso, 2014).

Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste , translated by Routledge Kegan & Paul (Oxon: Routledge, 2010).

Pierre Bourdieu, The Logic of Practice , translated by Richard Nice (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1992).

Judith Butler, “Consciousness Thus Makes Subjects of Us All” in The Psychic Life of Power. Theories in Subjection (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1994), 106-131.

James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988).

James Clifford and George E. Marcus (eds.), Writing Culture The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (Los Angeles, Berkeley: The University of California Press, 1986).

Jean Comaroff and John L. Comaroff, Of Revelation and Revolution, Vol. 1: Christianity, Colonialism, and Consciousness in South Africa (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

Terry Eagleton, Ideology: An Introduction (New York: Verso, 2007).

Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978-1979 , trans. by Graham Burchell (New York: Picador, 2008).

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction (New York: Vintage Books, 1990).

Michel Foucault, “Afterword: The Subject of Power,” in Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics , ed. Hubert L. Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), 208-228.

Michel Foucault, “Governmentality,” in The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality, edited by Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon, and Peter Miller (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1991), 87-104.

Clifford Geertz, Interpretations of Culture (New York: Basic Books, 1973).

Antonio Gramsci, The Prison Notebooks (New York: International Publishers Co., 1971).

Stuart Hall, “The Toad in the Garden: Thatcherism Amongst the Theorists,” in Nelson and L Grossberg (eds.), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 35-74.

Fredric Jameson, The Political Unconscious. Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982).

Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1992).

David Laitin, Hegemony and Culture: Politics and Change among the Yoruba (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986).

Karl Marx with Friedrich Engels, The German Ideology (New York: Prometheus Books, 1998).

Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (New York: International Publishers Co., 1994).

Karl Marx, Capital , Vol. 1, Selections, in The Marx and Engels Reader , ed. by Robert Tucker (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1978).

Elizabeth Povinelli, The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002).

William Sewell, Logics of History: Social Theory and Social Transformation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (New York: Vintage, 1966).

Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trans. by Talcott Parsons (New York: Routledge, 2010).

Lisa Wedeen, Ambiguities of Domination: Politics, Rhetoric, and Symbols in Contemporary Syria (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

Lisa Wedeen, Peripheral Visions Publics, Power, and Performance in Yemen (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2008).

Lisa Wedeen, “Conceptualizing Culture,” American Political Science Review 96 (2002): 713-728.

Lisa Wedeen, Authoritarian Apprehensions: Ideology, Judgment, and Mourning in Syria (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978).

Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985).

Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology (New York: Verso, 2009).

- Huber, John D., and Charles R. Shipan. Deliberate discretion?: The institutional foundations of bureaucratic autonomy . Cambridge University Press, 2002. (Ch. 1-4; 6)

- Powell, G. Bingham. Elections as instruments of democracy: Majoritarian and proportional visions . Yale University Press, 2000.

- Cox, Gary W. Making votes count: strategic coordination in the world's electoral systems . Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- North, Douglass C. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance . Cambridge university press, 1990.

- Stokes, Susan C., et al. Brokers, voters, and clientelism: The puzzle of distributive politics . Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Cox, Gary W. The efficient secret: The cabinet and the development of political parties in Victorian England . Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm. Policy, office, or votes?: how political parties in Western Europe make hard decisions . Cambridge University Press, 1999. (Pick chapters)

- Svolik, Milan W. The politics of authoritarian rule . Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Nalepa, Monika. Skeletons in the closet: Transitional justice in post-communist Europe . Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Samuels, David J., and Matthew S. Shugart. Presidents, parties, and prime ministers: How the separation of powers affects party organization and behavior . Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Carey, John M. Legislative voting and accountability . Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan, 1967 “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments,”

- North, Douglass C., and Barry R. Weingast. "Constitutions and commitment: the evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England." The journal of economic history 49.04 (1989): 803-832.

- Elinor, Ostrom. "Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action." (1990).

- Tsebelis, George. "Veto players and law production in parliamentary democracies: An empirical analysis." American Political Science Review 93.03 (1999): 591-608

- Mansfield, Edward D., Helen V. Milner, and B. Peter Rosendorff. "Free to trade: Democracies, autocracies, and international trade." American Political Science Review 94.2 (2000): 305-321.

- Clark, William Roberts, Matt Golder, and Sona Golder. An Exit, Voice, and Loyalty Model of Politics." British Journal of Political Science (2017)

- Nichter, Simeon. "Vote buying or turnout buying? Machine politics and the secret ballot." American Political Science Review 102.01 (2008): 19-31.

- Posner, Daniel N. "The political salience of cultural difference: Why Chewas and Tumbukas are allies in Zambia and adversaries in Malawi." American Political Science Review 98.4 (2004): 529-545.

- Carey, John and Matthew Soberg Shugart. 1995. “Incentives to Cultivate a Personal Vote: a Rank Ordering of Electoral Formulas.” Electoral Studies 14(4):417–439.

- Gandhi, Jennifer, and Adam Przeworski. "Authoritarian institutions and the survival of autocrats." Comparative Political Studies 40.11 (2007): 1279-1301.

- Jones, Mark P., and Wonjae Hwang. 2005. "Party Government in Presidential Democracies: Extending Cartel Theory Beyond the U.S. Congress," American Journal of Political Science

- Crisp, Brian F., Maria C. Escobar-Lemmon, Bradford S. Jones, Mark P. Jones, and Michelle M. Taylor-Robinson. 2004. “Electoral Incentives and Legislative Representation in Six Presidential Democracies.” The Journal of Politics 66(3): 823-46

- Cheibub, J. A., A. Przeworski, and S. M. Saiegh. 2004. “Government coalitions and legislative success under presidentialism and parliamentarism.” British Journal of Political Science 34(04): 565-587.

- Lijphart, A. 1991. “Constitutional choices for new democracies.” Journal of Democracy 2(1): 72-84.

- Heller, William B., and Carol Mershon. “Party Switching in the Italian Chamber of Deputies, 1996-2001.” The Journal of Politics 67, no. 2 (May 1, 2005): 536–559.

- Diermeier, Daniel, and Razvan Vlaicu. “Parties, Coalitions, and the Internal Organization of Legislatures.” American Political Science Review 105, no. 2 (2011): 359–380.

- Strom, Kaare. “A Behavioral Theory of Competitive Political Parties” American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 34, No. 2. (May, 1990), pp. 565-598.

- Harmel, Robert and Ken Janda, (1994) "An Integrated Theory of Party Goals and Party Change," Journal of Theoretical Politics 6: 259-288.

- Wolfgang C. Muller, “Inside the Black Box: A Confrontation of Party Executive Behaviour and Theories of Party Organizational Change,” Party Politics 3, no. 3 (July 1, 1997): 293-313.

- Kitschelt, Herbert. 1989. “The Internal Politics of Parties: The Law of Curvilinear Disparity Revisited.” Political Studies 37(3): 400-421

- Katz, Richard S., and Peter Mair. 1995. “Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party.” Party Politics 1(1): 5-28

- Carles Boix, "Setting the Rules of the Game: The Choice of Electoral Systems in Advanced Democracies." American Political Science Review 93, 3 (September 1999), 609-24.

Nadia Abu El-Haj, Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self- Fashioning in Israel Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001).

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism (London-New York: Verso, 1991).

Etienne Balibar and Immanuel Wallerstein, Race, Nation, Class (London: Verso, 1991).

Homi K. Bhabha (ed.), Nation and Narration (London and New York: Routledge, 1990), chapter one.

Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations , trans. by Harry Zhon and edited by Hannah Arendt (New York: Shocken Books, 1968), 253-264. Theses 9, 13-18.

Lauren Berlant, The Anatomy of National Fantasy: Hawthorne, Utopia, and Everyday Life (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

Rogers Brubaker, Nationalism Reframed: Nationhood and the National Question in the New Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Partha Chatterjee, The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993).

Geoff Eley and Ronald Grigor Suny, Becoming National: A Reader (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

Karl Deutsch, Nationalism and Social Communication (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1966).

Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983).

Manu Goswami, Producing India (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

Leah Greenfeld, Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992).

Anna Grzymala-Busse, Nations Under God: How Churches Use Moral Authority to Influence Policy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

Ghassan Hage, White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society (New York: Routledge, 2000).

Richard Handler, Nationalism and the Politics of Culture in Quebec (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1988).

Russell Hardin, One for All: The Logic of Group Conflict (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995).

Eric Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

David Laitin , Identity in Formation: The Russian Speaking Populations in the Near Abroad (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998).

Claudio Lomnitz, Deep Mexico, Silent Mexico: An Anthropology of Nationalism (Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota 2001).

Anthony W. Marx, Making Race and Nation: A Comparison of South Africa, the United States, and Brazil (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Peter Sahlins, Boundaries: The Making of France and Spain in the Pyrenees (Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989).

Hugh Seton-Watson, Nations and States (London: Methuen, 1977).

William H. Sewell Jr., "The French Revolution and the Emergence of the Nation Form," in Michael A. Morrison and Melinda Zook (eds.), Revolutionary Currents: Nation Building in the Transatlantic World , (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2004) [ON RESERVE].

Ronald Grigor Suny, The Revenge of the Past: Nationalism, Revolution, and the Collapse of the Soviet Union (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1993).

Yael Tamir, Liberal Nationalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995).

Katherine Verdery, What Was Socialism, and What Comes Next? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996).

Lisa Wedeen, Ambiguities of Domination: Politics, Rhetoric and Symbols in Contemporary Syria (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1999).

Lisa Wedeen, Peripheral Visions: Publics, Power, and Performance in Yemen (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008).

Huntington, Samuel P. Political Order in Changing Societies . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968.

Kalyvas, Stathis N. 2006. The Logic of Violence in Civil War . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Scott, James. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

Autesserre, Severine. The Trouble with the Congo: Local Violence and the Failure of International Peacebuilding . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Arjona, Ana, Nelson Kasfir, and Zachariah Mampilly (Eds.). 2015. Rebel Governance in Civil War . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Balcells, Laia. Rivalry and Revenge: The Politics of Violence during Civil War . Cambridge: New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Cederman, Lars-Erik, Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, and Halvard Buhaug. Inequality, Grievances, and Civil War . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Christia, Fotini. 2012. Alliance Formation in Civil Wars . Cam bridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, Dara Kay. 2016. Rape During Civil War . Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Finkel, Evgeny. 2017. Ordinary Jews: Choice and Survival during the Holocaust . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lessing, Benjamin. 2017. Making Peace in Drug Wars. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Petersen, Roger Dale. 2001. Resistance and Rebellion: Lessons from Eastern Europe . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Reno, William. Warfare in Independent Africa . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Roessler, Philip. Ethnic Politics and State Power in Africa: The Logic of the Coup-Civil War Trap . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Scott, James. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia . New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Staniland, Paul. 2014. Networks of Rebellion: Explaining Insurgent Cohesion and Collapse. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Stanton, Jessica A. Violence and Restraint in Civil War: Civilian Targeting in the Shadow of International Law . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Straus, Scott. 2015. Making and Unmaking Nations: War, Leadership, and Genocide in Modern Africa . Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Tilly, Charles. Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990-1992 . Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1992.

Weinstein, Jeremy M. 2006. Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wilkinson, Steven. Votes and Violence: Electoral Competition and Ethnic Riots in India . Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Wood, Elisabeth Jean. Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Fearon, James D., and David D. Laitin. “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War.” The American Political Science Review 97, no. 1 (February 2003): 75–90.

Centeno, Miguel Angel. 1997. “Blood and Debt: War and Taxation in Nineteenth Century Latin America.” American Journal of Sociology 102(6): 1565–1605.

Cunningham, Kathleen Gallagher. 2011. Divide and Conquer or Divide and Concede: How Do States Respond to Internally Divided Separatists? American Political Science Review 105 (02): 275–297.

Darden, Keith. 2008. “The Integrity of Corrupt States: Graft as an Informal State Institution.” Politics & Society 36(1): 35–59.

Fearon, James D. 1995. “Rationalist Explanations for War.” International Organization 49(3): 379–414.

Fujii, Lee Ann. “The Puzzle of Extra-Lethal Violence.” Perspectives on Politics 11, no. 02 (2013): 410–26.

Kalyvas, Stathis N., and Laia Balcells. 2010. “International System and Technologies of Rebellion: How the End of the Cold War Shaped Internal Conflict.” American Political Science Review 104(3): 415–29.

Keen, David. 1998. “The Economic Functions of Violence in Civil Wars.” The Adelphi Papers 38(320): 1–89.

Kuran, Timur. “Now Out of Never: The Element of Surprise in the East European Revolution of 1989.” World Politics 44, no. 1 (October 1991): 7–48.

Olson, Mancur. 1993. “Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development.” American Political Science Review 87(3): 567–76.

Skarbek, David. 2011. “Governance and Prison Gangs.” American Political Science Review 105(4): 702–16.

Staniland, Paul. 2012. “States, Insurgents, and Wartime Political Orders.” Perspectives on Politics 10(2): 243–64.

Trejo, Guillermo, and Sandra Ley. 2017. “Why Did Drug Cartels Go to War in Mexico? Subnational Party Alternation, the Breakdown of Criminal Protection, and the Onset of Large-Scale Violence.” Comparative Political Studies : 1041401772070.

Varshney, Ashutosh. “Ethnic Conflict and Civil Society: India and Beyond.” World Politics 53, no. 3 (April 2001): 362–98.

Walter, Barbara F. 2009. “Bargaining Failures and Civil War.” Annual Review of Political Science 12: 243–61.

Wickham-Crowley, Timothy P. 1990. “Terror and Guerrilla Warfare in Latin America , 1956-1970.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 32(2): 201–37.

Acemoglu, Daron, and James Robinson. 2006. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Albertus, Michael. 2015. Autocracy and Redistribution . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Albertus, Michael, and Victor Menaldo. 2018. Authoritarianism and the Elite Origins of Democracy . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ansell, Ben, and David Samuels. 2014. Inequality and Democratization: An Elite-Competition Approach . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Boix, Carles. 2003. Democracy and Redistribution . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, Alastair Smith, Randolph Silverson and James Morrow. 2003. The Logic of Political Survival . MIT Press.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, Steven Fish, Allen Hicken, Matthew Kroenig, Staffan I. Lindberg, Kelly McMann, Pamela Paxton, Holli A. Semetko, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, and Jan Teorell. 2011. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: A New Approach.” Perspectives on Politics 9(2): 247-67.

Dahl, Robert. 1971. Polyarchy . New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gandhi, Jennifer. 2008. Political Institutions Under Dictatorship. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Geddes, Barbara. "What do we know about democratization after twenty years?" Annual Review of Political Science 2, no. 1 (1999): 115-144.

Haber, Stephen. 2006. “Authoritarian Government.” In Barry Weingast and Donald Wittman, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Political Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 693-707.

Haggard, Stephan, and Robert Kaufman. 2016. Dictators and democrats: Masses, elites, and regime change . Princeton University Press.

Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan Way. 2010. Competitive authoritarianism: Hybrid regimes after the cold war . Cambridge University Press.

Linz, Juan, and Alfred Stepan. 1996. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Magaloni, Beatriz. 2006. Voting for Autocracy: Hegemonic Party Survival and Its Demise in Mexico. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Moore Jr., Barrington. 1966. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World . Boston: Beacon.

Nalepa, Monika. 2010. Skeletons in the Closet: Transitional Justice in Post-Communist Europe . New York: Cambridge University Press.

O’Donnell, Guillermo, Philippe C. Schmitter, and Laurence Whitehead. 1986. Transitions from authoritarian rule: Tentative conclusions about uncertain democracies . Johns Hopkins University Press.

Przeworski, Adam, Michael E. Alvarez, Jose Antonio Cheibub, and Fernando Limongi. 2000. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950–1990 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schedler, Andreas. "What is democratic consolidation?" Journal of Democracy 9.2 (1998): 91-107.

Slater, Dan. 2010. Ordering power: Contentious politics and authoritarian leviathans in Southeast Asia . New York: Cambridge University Press. Chapters 1 and 2, pp. 3-52.

Svolik, Milan. 2012. The Politics of Authoritarian Rule . Cambridge University Press.

Wedeen, Lisa. 1999. Ambiguities of Domination: Politics, Rhetoric, and Symbols in Contemporary Syria . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Weingast, Barry. 1997. “The Political Foundations of Democracy and the Rule of Law.” American Political Science Review 91(2): 245-63.

Wood, Elisabeth. 2000. Forging Democracy from Below: Insurgent Transitions in South Africa and El Salvador . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ziblatt, Daniel. 2017. Conservative Political Parties and the Birth of Modern Democracy in Europe . New York: Cambridge University Press.

This Website Uses Cookies.

This website uses cookies to improve user experience. By using our website you consent to all cookies in accordance with our Cookie Policy.

Department of Political Science

Comparative Politics Old Exams

Home — Essay Samples — Business — Comparative Analysis — Comparative Politics Approaches

Comparative Politics Approaches

- Categories: Comparative Analysis

About this sample

Words: 1297 |

Published: Feb 13, 2024

Words: 1297 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Business

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 912 words

4 pages / 1705 words

3 pages / 1343 words

3 pages / 1359 words

Remember! This is just a sample.