Legal Practice

Types of Legal Research

What do you mean by Legal Research?

Legal Research is the process of identifying and retrieving information necessary to support legal decision-making. It begins with an analysis of the facts of a problem and it concludes with the results of the investigation. Legal research skills are of great importance for lawyers to solve any legal case, regardless of area or type of practice. The most basic step in legal research is to find a noteworthy case governing the issues in question. As most legal researchers know, this is far more difficult than it sounds.

Whether you are a Lawyer, a paralegal, or a law student, it is essential that Legal research is done in an effective manner. This is where the methodology comes into play. Different cases must be approached in different ways and this is why it is important to know which type of legal research methodology is suitable for your case and helpful for your client.

Read Also: Here is the Importance of Legal Research in Legal Practice

Different Types of Legal Research

1) descriptive legal research.

Descriptive Legal research is defined as a research method that describes the characteristics of the population or phenomenon that is being studied. This methodology focuses more on the “what” of the research subject rather than the “why” of the research subject. In other words, descriptive legal research primarily focuses on the nature of a demographic segment, without focusing on “why” something happens. In other words, it is a description based which does not cover the “why” aspect of the research subject.

For example, a lawyer that wants to understand the crime trends among Mumbai will conduct a demographic survey of this region, gather population data and then conduct descriptive research on this demographic segment. The research will then give us the details on “what is the crime pattern of Mumbai?”, but not cover any investigative details on “why” the patterns exits. Because for the lawyer trying to understand these crimes patterns, for them, understanding the nature of their crimes is the objective of the study.

2) Quantitative research

Quantitative Legal Research is a characteristic of Descriptive Legal Research Methodology that attempts to collect quantifiable information to be used for statistical analysis of the population sample. It is a popular research tool that allows us to collect and describe the nature of the demographic segment. Quantitative Legal Research collects information from existing and potential data using sampling methods like online surveys, online polls, questionnaires, etc., the results of which can be depicted in numerical form. After careful understanding of these numbers, it is possible to predict the future and make changes to manage the situation.

An example of quantitative research is the survey conducted to understand the turnaround time of cases in the high court and how much time it takes from the time the case is filed until the judgment is passed. A complainant’s satisfaction survey template can be administered to ask questions like how much time did the process take, how often were they called to court, and other such questions.

3) Qualitative Legal Research

Qualitative Legal Research is a subjective form of research that relies on the analysis of controlled observations of the legal researcher. In qualitative research, data is obtained from a relatively small group of subjects. Data is not analyzed with statistical techniques. Usually, narrative data is collected in qualitative research.

Qualitative research can be adopted as a method to study people or systems by interacting with and observing the subjects regularly. The various methods used for collecting data in qualitative research are grounded theory practice, narratology, storytelling, and ethnography.

Grounded theory practice: It is research grounded in the observations or data from which it was developed. Various data sources used in grounded theory are quantitative data, review of records, interviews, observation, and surveys.

Narratology: It refers to the theory and study of narrative and narrative structure. It also shows the way in which the result affects the researcher’s perception.

Storytelling: This is a method by which events are recounted in the form of a story. The method is generally used in the field of organization and management studies.

Ethnography- Ethnography is used for investigating cultures by collecting and describing data intend to help the development of a theory.

4) Analytical Legal Research

Analytical Legal Research is a style of qualitative inquiry. It is a specific type of research that involves critical thinking skills and the evaluation of facts and information relative to the research being conducted. Lawyers often use an analytical approach to their legal research to find the most relevant information. From analytical research, a person finds out critical details to add new ideas to the material being produced.

For example, examining the fluctuations of Crime Rates of India between 2010-2020 is an example of descriptive research; while explaining why and how the Crime rates spiked over time is an example of analytical research.

5) Applied Legal Research

Applied Legal Research is a methodology used to find a solution to a pressing practical problem at hand. It is a straightforward practical approach to the case you are handling. It involves doing full-fledged research on a specific area of law followed by gathering information on all technical legal rules and principles applied and forming an opinion on the prospects for the client in the scenario.

For Example, if your client is an employee of an organization and is fighting against wrongful termination of contract then the practical approach to this would be by carefully evaluating the company policies and finding company policies that were violated and to suing the organization based on those arguments.

6) Pure Legal Research

Pure legal research is also known as basic Legal Research usually focuses on generalization and formulation of a theory. The aim of this type of research methodology is to broaden the understanding of a particular field of investigation. It is a more general form of approach to the case you are handling. The researcher does not focus on the practical utility

For Example, researchers might conduct basic research on illiteracy leads to unemployment. The results of these theoretical explorations might lead to further studies designed to solve specific problems of unemployment.

7) Conceptual Legal Research

Conceptual Legal Research is defined as a methodology wherein research is conducted by observing and analyzing already present information on a given topic. Conceptual research doesn’t involve conducting any practical experiments. It is related to abstract concepts or ideas.

They are generally resorted to by the philosophers and thinkers to develop new concepts or reinterpret the existing concepts but has also proven to be a useful methodology for legal purposes.

For example, many of our ancient laws were influenced by the British Rule. Only later did we improve upon many laws and created new and simplified laws after our Independence. So another way to think of this type of research would be to observe, come up with a concept or theories aligned with previous theories to hopefully derive new theories.

8) Empirical Legal Research

Empirical Legal Research describes how to investigate the roles of legislation, regulation, legal policies, and other legal arrangements at play in society. It acts as a guide to paralegals, lawyers, and law students on how to do empirical legal research, covering history, methods, evidence, growth of knowledge, and links with normativity. This multidisciplinary approach combines insights and approaches from different social sciences, evaluation studies, Big Data analytics, and empirically informed ethics.

For example, Pharmaceutical companies use empirical research to try out a specific drug on controlled groups or random groups to study the effect and cause.

Read Also – How to Do Legal Research?

Other Major Methods of Legal Research.

1) doctrinal legal research.

The central question of inquiry here is ‘what is the law?’ on a particular issue. It is concerned with finding the law, rigorously analyzing it and coming up with logical reasoning behind it. Therefore, it immensely contributes to the continuity, consistency, and certainty of law. The basic information can be found in the statutory material i.e.

primary sources as well in the secondary sources. However, the research has its own limitations, it is subjective, that is limited to the perception of the researcher, away from the actual working of the law, devoid of factors that lie outside the boundaries of the law, and fails to focus on the actual practice of the courts.

2) Non-doctrinal Legal Research

It is also known as socio-legal research and it looks into how the law and legal institutions mold and affects society. It employs methods taken from other disciplines in order to generate empirical data to answer the questions.

3) Comparative Legal Research

This involves a comparison of legal doctrines, legislations, and foreign laws. It highlights the cultural and social character of law and how does it act in different settings. So it is useful in developing and amending, and modifying the law. But a

the cautious approach has to be taken in blindly accepting the law of another social setting as a base because it might not act in the same manner in a different setting.

Read Also – What is Doctrinal and Non-Doctrinal Legal Research?

Legal research is a systematic understanding of the law while keeping in mind it’s advancements. Law usually acts within the society and they both have an impact on each other. Each kind of research methodology has its own value. However, while undertaking research a researcher might face some hurdles but they can be avoided if he/she properly plans the research process.

Legodesk is the best cloud-based legal case management software for law professionals. It also helps Clients find a lawyer. Interested to know more? Sign Up today to start your free trial or contact us if you have any queries.

Try our Debt Resolution solutions today Request a Demo

Very useful and compact information, thank you.

Very useful information 👍

I found this information to be stimulating and informative.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the different types of legal research. It’s a great resource for law students and professionals alike!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How to Do Research in International Law? A Basic Guide for Beginners

Jan 25, 2021 | Essays , Online Scholarship

By: Eliav Lieblich *

[Click here for PDF]

Introduction

So, you want to do research in international law? Good choice. But it can be difficult, especially in the very beginning. In this brief guide for students taking their first steps in legal research in international law, I will try to lay down the basics—just enough to nudge you towards the rabbit-hole of research. This guide is about how to think of and frame research questions, primary sources, and secondary sources in the research of international law. Or, to be precise, it is about how I think about these things. It is not about how to write in the technical sense, how to structure your paper, or about research methods (beyond some basic comments). This guide also focuses mostly on questions that are especially pertinent when researching international law. For this reason, it does not address general questions such as how and when to cite authorities, what are relevant academic resources, and so forth.

As you begin your work, you will find that legal research in international law is both similar to and different from legal research in domestic law. Research in international law and domestic law are similar in their basic requirements: 1) you need a research question, 2) you need to understand the problem you are approaching (both in terms of the legal doctrine and its underlying theory), 3) you need a method to answer your question. and 4) you need to rely on primary and secondary sources. Research in international law is different because international law, in its quest to be universal, is practiced everywhere. There is no “single” international law, and for this reason it is an area of law that is almost always contested. Furthermore, international law is not hierarchical unlike most domestic legal systems, and many times, several legal frameworks might apply to one single question ( “ fragmentation ”). [1] Additionally, international law’s sources include customary law, which is notoriously difficult to pinpoint. [2] This makes describing “the law” as an object of research much trickier. This guide attempts to give you the initial tools to navigate this terrain, but rest assured that it is also difficult for experienced researchers.

The guide is structured as follows. Section 2 is about research questions. It first offers a simplified typology of research question, including a few words on theory and method, and then suggests some thoughts about thinking of and framing your question. Section 3 is about secondary and primary sources in the research of international law. It includes some advice about the way to approach international legal scholarship in a world of hegemony and information overflow. The guide then becomes a bit more technical, offering tips about finding primary sources relevant for the research of international law.

A caveat is in order. This guide does not seek to offer the most theoretically robust or comprehensive introduction to international legal research. Rather, it should be viewed as practical advice to help you take your first steps into the field. The guide, of course, reflects my own understanding. Other researchers might approach these issues differently.

I. Research Questions

A. types of research questions: descriptive, normative, and critical.

Finding a research question will be one of the most important and challenging parts of your research. Every research has a question at its foundation. The research question is simply the question that your research seeks to answer. In all fields of legal scholarship, there are basically three families of research questions: 1) descriptive research questions, 2) normative research questions, and 3) critical research questions. Very broadly speaking, descriptive questions seek to tell us something about the legal world as it is . Normative questions ask what ought to be the state of things in relation to law. Critical questions seek to expose the relations between law and power, and, as I explain later, are somewhat in the middle between descriptive and normative questions. In truth, there is a lot of interaction between all three types of questions. But for our sake, we keep it simple, and as a starting point for research, it is better to think about research questions in these terms. Thinking clearly about your research question will help you frame your work, structure your paper, and look for relevant sources.

Descriptive research questions are questions about the state of things as they are. Much of traditional international legal scholarship is descriptive in the sense that it seeks to describe “the law” as it is, whether in abstract (e.g., “what is the content of the Monetary Gold principle in international adjudication?”) or in relation to a specific situation. For instance, in their excellent writing on Yemen , Tom Ruys and Luca Ferro look at the Saudi-led intervention in the Yemeni Civil War and ask whether that intervention is lawful. [3] From a theoretical standpoint, this type of research can be broadly described as positivist , in the sense that it looks only into legally relevant sources (the lex lata ), as autonomous bodies of knowledge. We can call such questions descriptive doctrinal research questions since they seek to analyze and describe the doctrine from an internal point of view. Of course, some doubt whether it is at all possible to describe authoritatively what the law “is,” beyond very basic statements, without making any normative judgments about what “the law” should be. It could even be said that the mere decision to discuss law as an autonomous sphere is a value-laden choice. These and related critiques have been levelled against doctrinal scholarship for over a century by legal realist and critical approaches, both domestically and internationally. [4] This resulted in the gradual marginalization of such research questions, at least in the United States. Yet, from a global perspective, doctrinal research into international law remains a central strand of research.

Doctrinal questions are not the only type of descriptive research questions. Descriptive questions can also follow the tradition of law and society approaches. This type of research looks at the law from the outside and is mostly interested in law’s interaction with society, rather than in legal doctrine per se . Historically, the emergence of this way of thinking relates to the insight, first articulated by legal realists, that law does not exist in an autonomous sphere and gains meaning only with its actual interaction with society. Research questions of this type might ask whether and when law is effective, how people think about the law, or how judges make decisions. For instance, in her recent book , Anthea Roberts asks whether international law is truly “international” by looking at how it is studied in different parts of the world. [5] This type of scholarship can also seek to explain law from a historical point of view. For example, Eyal Benvenisti and Doreen Lustig inquire into the interests that shaped the origins of modern international humanitarian law (“IHL”) and argue that the law was shaped more by the interests of ruling elites than by humanitarian impulses. [6] For the purposes of this guide, these are socio-legal research questions .

Normative research questions , in general, ask what the law ought to be, whether in general or in a specific instance. For example, in “The Dispensable Lives of Soldiers,” Gabriella Blum asks what ought to be the rules for the targeting of combatants in armed conflict. [7] As she suggests, these rules should consider the specific threat they pose and not only their legal status as combatants. The difficulty in normative questions—and from my own experience, this is one of the major challenges for students in their first research papers—is that to answer them, we need external parameters for assessing law . In other words, we need a theory on what is considered “good,” in light of which we can present an argument about what the law should be. Otherwise, we run into a classic problem: we cannot draw from facts alone (what law “is”) what ought to be (what law should be). [8] It is here where theory plays a key role. Normative legal theories are there to help us articulate our benchmarks for assessing what law should be. Returning to Blum’s article as an example, she uses insights from ethics to consolidate her point. She argues from an ethical, extra-legal vantage point, that since soldiers’ lives have moral worth, law should be understood in a manner that best reflects this moral idea.

Now, there is a myriad of normative approaches to international law, which I will not address here. A good place to start on theories of international law, including normative ones, is Andrea Bianchi’s excellent and accessible book on international legal theories. [9] Just to give you a sense of things, older natural law theories would simply identify law with morality and would inquire into morality—either as handed down by God or as exposed by reason—in order to ascertain law. [10] In newer scholarship, it is much more common to use ethics as a way to criticize positive law or to read moral standards into the interpretation of law itself —in accordance with the moral theory to which we subscribe. [11] This, for instance, is Ronald Dworkin’s approach , when he urges to interpret law “in its best light.” [12] In international law, for instance, a notable example for such thinking is Thomas Franck’s theory of legitimacy and international law. [13] Franck—although careful not to frame his theory in explicitly moral terms—argues that legal rules should have certain characteristics, such as clarity and coherence, in order to enjoy a “compliance pull” that induces state compliance. If, for example, we were to adopt Franck’s theory, we would assess law in light of his standards of legitimacy.

Normative theories can also be utilitarian. The best known example for such way of thinking, of course, is law and economics . [14] Another family of instrumental normative theories can be roughly described as policy approaches to international law. In the simplest sense, policy approaches ask what the law should be, in terms of its ability to bring about good policy consequences. The New Haven School of International Law, for instance, analyzed international law from the point of a global standard of human dignity. [15] It is safe to say that almost all current scholarship on international law, especially in the United States, utilizes policy approaches, even if not explicitly. [16] To sum this point, when framing normative research questions, we should be aware that at some point, we will need to commit to a yardstick through which to assess our normative conclusions.

Critical research questions inquire into the power relations that shape law or into the relations between law and politics in the broad sense of the term. In this sense, they aim to be descriptive: they seek to describe law as a product of power relations and expose the manner in which law conceals and neutralizes political choices. [17] Like normative scholarship, critical research questions also rely on theories (“ critical theories ”). For example, Martti Koskenniemi seeks to describe how the structure of the international legal argument collapses into politics, using insights from Critical Legal Studies (“CLS”). [18] Aeyal Gross inquires whether the application of international human rights law might harm rather than benefit Protected Persons in occupied territories, on the basis of theoretical tools from CLS and Legal Realism. [19] Anthony Anghie asks how colonialism shaped the origins of international law, on the basis of postcolonial theory (and specifically in international law, Third World Approaches to International Law). [20] Ntina Tzouvala considers whether and how the 19th century standards of civilization in international law continue to live on in the international system through its capitalist underpinnings, by applying Marxian analysis. [21] From a feminist approach, Fionnuala Ní Aoláin explores what are the gendered aspects of the law of occupation. [22] It should be emphasized that critical research questions are also normative in the deeper sense: by seeking to expose power relations, they imply that something is wrong with law. Some critical research proceeds, after exposing power dynamics, to offer solutions—and some simply conclude that the project of law is a lost cause.

It is crucial to understand that both normative and critical research questions usually have descriptive sub-questions. For instance, Blum’s normative claim is that the current rule on targeting combatants is no longer tenable and should be changed. But to do so, she first has to give a proper account of the current understanding of law. And that is, of course, a descriptive question. The same applies to critical questions. Good critical scholarship should give a valid account of its object of critique. For example, in Tzouvala’s piece, a significant part offers a description of the standards of civilization, before the main critique is applied.

B. A Note about Theory and Methods

The term theory has been used quite liberally in the previous section. Now, there are several ways to understand this term. Here, theory is used in the sense of the general intellectual framework through which we think about law or a certain legal question. It is our view on the world, if you will—the prism through which we analyze or assess a question. The term theory must be distinguished from method . Methods, in legal research, encompass at least two meanings. The first, more common in descriptive socio-legal research, refers to the way in which we seek to find and arrange the information required to answer our question. For instance, if my question is “do judges in international courts cite scholarship from the Global South,” my method would be the manner in which I gather and arrange the data about judges’ citation practices. Do I search all relevant decisions for citations and create a large dataset (empirical quantitative methods)? Do I conduct interviews with prominent judges and extrapolate from their positions (qualitative methods)? Descriptive doctrinal research, too, has its version of methods in this sense. When we analyze treaties, legislation, state practice, or case law, we apply a method of collecting, analyzing, and categorizing this information.

The second manner in which the term method is used, is more pertinent in normative and critical legal research. For example, in an American Journal of International Law symposium on methods in international legal research, “methods” were defined as “the application of a conceptual apparatus or framework—a theory of international law—to the concrete problems faced by the international community”. [23] Meaning, methods are defined here as the way in which we apply theory to specific instances —or in other words, as applied theory. It is in this sense that you will hear terms like “feminist methods” or “critical methods” used.

In truth, much of legal research—with the exception of certain strands of law and society research—is quite loose in its awareness to methods and in its use of them. This is perhaps because most of us are socialized, in our earliest days as law students, into the general method of doctrinal approaches to law—legal interpretation, case analysis, analogy, and allusions to consideration of “legal policy” in order to solve dilemmas. The extent to which you will be required to be strict about methods in legal research, would probably differ between instructors and their own backgrounds.

C. Framing and Finding Your Research Question

What is expected from a research question, at least in the initial stage of your work? Of course, this differs between instructors and advisors. Here, I offer some insights that I think are generally applicable, with specific reference to international law.

First, a lot depends on the stage of your studies. In most seminars at the J.D. or LL.B. level, instructors do not necessarily require that your question be entirely novel, in the sense that no one has asked it before. Of course, most instructors value originality and would be happy if you come up with a reasonably original question (provided that you can answer it, but more about that in a bit). On the Master’s or Ph.D. levels, this might be very different. Framing a question that would be “an original contribution to the field” is one of the crucial parts of writing a dissertation at that level. But since this is a beginners’ guide, do not worry about that.

Second, a research question must be tailored to the scope of your work, or in other words, it must be a question that you can reasonably answer within the space you have been given. Most seminar papers are around 10,000 words, inclusive of footnotes. This length suits a question like “should the duty to take precautionary measures under IHL require risking soldiers’ lives?” but probably not “the legal history of proxy wars during the Cold War.” The unfortunate nature of seminars is that you will usually have very limited time to think of a research question, and since you are new in the field, you would probably have trouble figuring out whether your question fits the scope of your paper. Most instructors (I hope) would be happy to let you know if your question is too wide.

Third, a research question should be one that you are capable of answering with the skills you have, or with skills—the methodological proficiency –that you have the time to reasonably acquire during your research (whether independently or with the assistance of your instructor). By the time students write seminar papers, most have a reasonable grasp of how to do legal reasoning from an internal-legal point of view and accordingly have the basic skills to answer descriptive doctrinal questions . Concerning most normative and critical research questions, the basic skills required—at least at the level required in seminar papers in most law schools—can be acquired during your research: to me, learning new theories and the ways to apply them is precisely what seminars should be about! The trick is to find the question and the normative or critical approach that you would like to explore. However, things get much trickier if you select a descriptive socio-legal question . These require, sometimes, research methods that most law students do not possess at this stage. If you are thinking about such questions, consult with your instructor to see whether she can or is willing to instruct you about the method you need.

But wait! We said nothing about how to actually find your research question. Here, I might disappoint you: there is no way around some of the difficulties we encounter when looking for a question. Finding a research question is hard, in particular when you are just starting out and have a limited grasp on the field. In truth, there is no one way—if there is even a way—to find a research question. A research question begins from an idea, and we cannot really control how our ideas emerge. Even the most experienced researchers will probably tell you that they get their ideas serendipitously when taking a shower, walking the dog, or folding the laundry. “Eureka” moments rarely pop-up when we summon them. So rather than attempting to give (a futile) account on a sure-shot way to find your research questions, I suggest ways that might be conducive to spark the creative thought process needed to get a good idea.

First, ask yourself what interests you, in the most intuitive way, in terms of specific fields of international law. If you are enrolled in a thematic course, such as International Trade Law, or International Criminal Law, then this narrows your selection of course. But even within fields, there are numerous sub and sub-sub fields and questions. In international criminal law, for example, there is a world of difference between questions of jurisdiction and theories of punishment. Start by opening a general textbook in the field. Scan the contents. See the types of issues and dilemmas that arise. See what direction triggers your interest. Most textbooks will highlight controversial issues. Ask yourself whether any of these issues both interest you and can be phrased as a research question that conforms to the requirements discussed above.

Second, follow blogs in the field. There are many high quality blogs on international law, which offer good analysis on current events and legal dilemmas. These blogs can help you to map burning and interesting questions. Leading blogs such as EJIL: Talk! , Just Security , Legal Form , Opinio Juris , and Lawfare are good places to start. For those of you really willing to take the plunge, there is a very vibrant community of international law scholars on Twitter (although it might lead you to question the general sanity of the field). International legal institutions and organizations also maintain active Twitter profiles, and so do states.

Third, it is ok to begin with a somewhat general or imprecise research question, and narrow it down and refine as you go. For instance, let’s assume that you begin with “should the duty to take precautionary measures under IHL require risking soldiers’ lives.” As you read, you will find that there are several different precautions under IHL. Depending on the scope of your research, you might want to refine your question to something like “should the duty to give advance warning to civilians require exposing soldiers to potential harm?” In other words, it is perfectly fine to make adjustments to your question as you go.

Fourth, be proactive in your communications with your instructor. There are different types of instruction on the seminar level, but most instructors would be happy to participate with you in a ping-pong of ideas on your research question—as long as you have done some thinking and come with ideas to discuss, even if these are half-baked.

II. Secondary and Primary Sources in International Legal Research

Once we have the research question, we need information to answer it. This information is found in research sources . In academic research, it is common to differentiate between primary and secondary sources. In simple terms, primary sources comprise raw information or first-hand accounts of something. By way of example, these include diary entries, interviews, questionnaires, archival data, and meeting records. In basic legal research, primary sources can include black letter law, rulings, and so forth. Another way to look at primary sources is that they give you direct, unmediated access to the objective of your research. Secondary sources, conversely, are writings about primary sources: they interpret primary sources for you. These include primarily academic books, book chapters, and journal articles. Of course, there are dialectics between primary and secondary sources. Sometimes, secondary sources can become primary sources, depending on our perspective. If, for example, I want to write about the international legal philosophy of Hans Kelsen, then Kelsen’s writings become my primary sources. Other people’s writings about Kelsenwould be my secondary sources. Similarly, a judicial decision can be a primary source when we study what the law “is,” but it can also be secondary source when it describes other things, such as facts, opinions, or ideas.

In international law, there is another idiosyncrasy. If we want to know what the law “is,” secondary sources might be considered primary, to an extent, because according to international law itself, “the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists” are subsidiary means to determine the positive law. [24]

B. The Intricacies of Secondary Sources of International Law: Managing Hegemony and Information Overload

Is there something special that we need to know about secondary sources in international legal research? On its face, secondary sources on international law are not much different from such sources in any other field. For this reason, I will not get into questions that are relevant to all fields of research, such as how to account for newspaper stories, the value of Wikipedia for research (very limited), etc. Rather, I will point out some things that are especially important to consider when approaching secondary sources in international law.

First, since international law presumes to apply everywhere, there might be relevant literature on your question in any language you can imagine. At the seminar paper level, most instructors will expect you to rely on literature in languages reasonably accessible to you. In more advanced levels of research, things might be different. As a rule of thumb, if you cannot access writings in at least English or French, your research will unfortunately be limited. Of course, we can criticize this situation in terms of the hegemony it reflects; [25] however, this is the reality as it stands. A possible exception is if your question focuses on the application of law in a specific jurisdiction. But here, too, you will be limited since without access to literature in other languages, your comparative ability will be diminished.

Second—and this is an understatement—there are differing perceptions of international law, both in general and on specific questions, across different legal cultures. Risking pandering to stereotypes, U.S. scholarship tends to be more inclined towards policy approaches to law, while continental European scholarship might be more positivist. [26] Scholarship from the Global South might view law from postcolonial perspectives. It is crucial to be aware of these differences, in the sense that no single perspective can give you the entire picture. This is not to say that you cannot focus on one specific legal culture—depending on your research question—just be aware that you might be getting a particular point of view.

Third, even within a specific legal culture, there are interpretive “camps” on most questions of international law. Very roughly speaking, writers affiliated with state institutions might interpret law in a manner more permissive of state action, while others might be more suspicious of states and approach law from a more restrictive perspective. For instance, in the field of IHL, David Luban identifies “two cultures” of interpretation—military and “humanitarian” lawyers—that differ almost on every legal question. [27] You will find comparable divisions on international trade, investment arbitration, and international environmental law—and in any other field for that matter. Here, too, it is very important to be aware of the “camp” of the author you are reading. You will not get a complete view if all of your secondary sources belong to this or that camp.

Fourth, be aware and critical of hierarchies. Traditionally, secondary sources of international law were organized around major treatises (which are textbooks that deal systematically with an issue), such as Oppenheim’s international law. [28] This tendency derives from the special status that major scholarship enjoys in the formation of international law, as mentioned above. Of course, major “classic” textbooks are still invaluable tools to get into the field and at least to understand its mainstream at a given moment. However, many canonical treatises—to be blunt—have been written by white western men from major empires, with certain perspectives about the world. Often, these writers went in and out of diplomatic service and might be generally uncritical of their states’ legal policies. Many newer versions of these textbooks internalize these critiques and are much better in terms of incorporating diverse authors and views. Nonetheless, in order to get the fuller picture on your question, diversify your sources.

Fifth, and notwithstanding the need to take into account the problem of hierarchies, it is still important to get a good grasp of the “important” writings on your research question, in order to understand the predominant views on the issue. In an age of information overload, this is particularly difficult to do. There are, however, several (imperfect) ways to mitigate this problem. One way to do so is by using Google Scholar and Google Books as entry portals into your subject. These search engines allow you both to search for titles and specific phrases within titles. They are free, simple and fast, and Google Books even allows you to preview most books. Google Scholar and Books also present a citation count for each source. Citation counts refer to the number of times a work has been cited by other authors, which gives you a rough measure of the centrality of the work. However, Google’s search engines should be taken with a grain of salt. Google is a data-for-profit company, and its effects on academic research have been criticized . [29] The basic problem is that nobody knows how Google arranges its results and what interests it serves by doing so. In other words, Google creates a new hierarchy of sources, and we do not know exactly how to account for it.

Another way to get a sense of the important writings relating to your question is to look at general, introductory works on your subject. These textbooks usually provide a good overview of the major discussions and dilemmas relating to the fields they cover, and when doing so, they present the central views on these questions. See which writings they discuss and cite. A good place to start, in order to gain access to initial secondary (and sometimes primary) sources on a specific question, is the Max Planck Encyclopedias of International Law or the Oxford Bibliographies of International Law .

Still, always be mindful that the “central views” on a question are not necessarily the best views. For instance, many times, citation practices simply reproduce geographic, institutional, racial, or gendered hierarchy. They are not meaningless, but be critical about them. After you get the “central views” on the question go to more “neutral” search engines such as your library’s general database or commercial databases such as Hein and Westlaw that arrange scholarship in a more transparent manner. One radical suggestion is to visit your library physically (!) and go to the relevant shelf. Libraries are nice, and you will often find titles that you missed in your electronic search.

C. Primary Research Sources of International Law: What are They and Where to Find Them

What are the primary sources for research in international law? The answer, of course, flows from the type of your research question. The sources for doctrinal research questions would generally follow material that would be relevant for the study of the legal sources of international law, namely those found in Article 38(1) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice (“ICJ”): 1) treaties, 2) state practice and opinio juris (as elements of customary law), 3) general principles of law, and 4) as subsidiary means, judicial decisions and scholarly work.

However, even when conducting doctrinal research, not everyone subscribes to an exclusively formalist understanding of legal sources. For instance, there are many forms of formal and informal regulation in various global governance frameworks. Non-binding resolutions of international organizations, for example, and instruments of “soft law” can also be viewed as part of the doctrine, broadly speaking. [30] Additionally, legal realists might argue that whatever is perceived by international actors as authoritative and controlling in specific instances can be analyzed as a legally relevant source. [31] The important takeaway is that the primary sources for doctrinal research follow the author’s approach to the sources relevant for international law, and this changes between legal formalists and realists. This complicates your work, but even as a beginner, you would need to decide which way to go in terms of identifying relevant primary sources. If you are confused about this, consulting with your instructor is probably wise here.

As discussed earlier on, normative and critical research questions tend to have descriptive doctrinal sub-questions. For the doctrinal parts in normative and critical research, the above primary sources are relevant also. The normative and critical parts of such research, conversely, would usually rely on the application to the descriptive findings of theory found in secondary sources (and recall the definition of method as applied theory, suggested in the AJIL symposium). [32]

For socio-legal research questions, primary sources can extend much wider, depending on the specific research method selected. Since the challenges of identifying sources for socio-legal research are not unique in the context of international legal research and require treatment beyond this limited guide, I do not address them here.

After clearing that up (hopefully), we now move to a more technical part: where can we find primary sources for doctrinal research in international law (or doctrinal parts within otherwise non-doctrinal research)? Of course, there are virtually endless options. Here, I seek only to give an overview of some of the best ways to look for such sources, or at least, those that I prefer. Note, that I do not get into the nitty-gritty of each search engine or database, such as how to run searches and where to click. They are usually quite easy to get a handle on, and if not, most law school libraries have very capable personnel to assist in the more technical aspects of things. In the same vein, I do not get into the specifics of document indexing systems of various institutions (see, for instance, here ).

1. Curated Collections of Important Primary Sources

Before delving into specific primary sources and where we can find them, it is good to know that some publications select especially important sources and publish them with commentary. These publications do not include all primary sources, but if you want to search for especially pertinent sources on your subject, they can be helpful. For example, International Legal Materials (“ILM”) is a publication of the American Society of International Law that periodically selects important primary sources, with expert commentary. Although ILM is a very old publication, it is fortunately online, and you can search its database.

2. Treaties and Treaty Bodies

Moving on to treaties. In general, you can access the text of almost every treaty directly from any internet search engine. For comprehensive research, however, the United Nations Treaty Collection (“UN Treaty Collection”) has a sophisticated search page , allowing you to find treaties by title, signatories, dates, and many other categories. When you click on a treaty, you can also find the list of state parties, including reservations, declarations, etc. Take note of that the UN Treaty Collection includes only treaties registered with the United Nations . The most important treaties are indeed registered. Those that are not might be found in secondary sources, in governmental websites, and so forth. Last, Oxford Historical Treaties is a great source for older treaties.

Treaties can also be found in the homepages of relevant international organizations. For instance, the World Trade Organization website includes all of the organization’s founding agreements and other relevant treaties. Regional organizations, also, mostly follow this practice. The International Committee of the Red Cross (“ICRC”) website has an index of all historical and in-force IHL treaties. These are only examples.

For the purpose of your research, you might want to look at the travaux préparatoires —which include the official negotiation records of the treaty, its drafting history, and other preparatory documents. These are important both to interpret and understand the history and rationales of the treaty. There is no single way in which these records are published. Many times, they can be found in official volumes, whether online or in hardcopy. For example, the travaux of the European Conventions of Human Rights can be found online here . You can find more information about finding travaux at the UN Library on this page .

Many treaties establish organs that oversee their execution or interpret their provisions (“treaty bodies”). These organs, in turn, create their own documents, decisions, and comments. This is a particularly important feature of international human rights law treaties. Luckily, the UN keeps a searchable treaty body database in which you can search for virtually any type of document produced by these bodies. For example, you can find various reports submitted to these bodies by states; you can also find decisions (“jurisprudence”) of treaty bodies, as some of them are empowered to decide on individual and interstate claims. For more information about research in human rights law, Georgetown Law produced this great guide (on both secondary and primary sources).

3. Judicial Decisions

Judicial decisions constitute important primary sources in international legal research like in any legal research. However, as opposed to domestic jurisdictions, the terrain of international legal tribunals is heavily fragmented. [33] As you probably know by now, there is no “supreme court of the international community” to which all other courts are subject. Most tribunals are limited in their jurisdiction to a certain subject matter or to a certain group of states or individuals. To make things even more complicated, domestic courts also frequently rule on international legal questions or refer to international law in their decisions. A crucial point when conducting your research is to figure out whether there is an international tribunal that might have jurisdiction over issues relating to your question and whether these issues were addressed in a substantial way by domestic courts.

Fortunately, there are search engines that allow us to search for specific things across many international tribunals and dispute settlement mechanisms. The Oxford Reports on International Law , for instance, allows you to search across virtually all international tribunals and arbitration mechanisms (as well as treaty bodies). It includes not only ICJ rulings, but also rulings and decisions of subject-area specific dispute settlement mechanisms such as the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (“ITLOS”) and others. Furthermore, the search engine allows you also to look for domestic rulings that apply international law in many jurisdictions. Be mindful, however, that the database on domestic rulings is not comprehensive, and many times does not include the newest rulings since it takes time for the regional reporters to report them. The Cambridge Law Reports is another very reputable and established source for international case law and domestic rulings relating to international law.

It should be noted that in addition to these databases, most tribunals have their own websites. Just by way of example, the ICJ , the European Court of Human Rights , the International Criminal Court (“ICC”), and the WTO Dispute Settlement mechanism all have very helpful sites with their own advanced search engines. Similarly, the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (“ICSID”) allows you to search for decisions in investment-state arbitrations. Many other tribunals and dispute settlement arrangements have similar systems. The added value of the tribunals’ own sites is that they usually include not only decisions, but also oral and written proceedings and other documents of interest for in-depth research. Moreover, it might be that they are updated faster with new decisions.

Note, however, that many questions are never resolved by any tribunal. International law is more of an ongoing process than a system of adjudication, [34] and the fact that a dispute or dilemma has not been formally addressed by courts does not mean that it is not important or that there are no highly relevant primary sources on the issue. Ironically, often the opposite is true: some important questions do not come up for adjudication precisely because actors do not want to risk losing in adjudication.

4. United Nations Documents

Documents produced by the different organs of the UN—as well as by states when interacting in and with the UN—are of special importance for international legal research. Resolutions by the UN Security Council (“UNSC”) can be binding; resolutions by the UN General Assembly might reflect the international consensus, can be declarative of customary international law, or crystallize into binding law as time passes. Reports by the UN Secretary General and by Special Rapporteurs are also important in this sense, not to mention the work of the UN International Law Commission (“ILC”). Letters by states and their statements in various UN fora are also crucial as sources for state practice and opinio juris. Fortunately, The UN’s Official Document System allows you to run searches into the majority of publicly available UN documents. Additionally, the UN Library provides another, more guided, entry point to the universe of UN documents.

Sometimes, if you know the specific type of document you need, it can be helpful to head to the website of the relevant UN organ. For example, the UNSC ’s site has all of the UNSC’s resolutions, presidential statements, reports and meeting records by year (as well as documents relating to sub-organs such as Sanctions Committees). You can find, for instance, a specific meeting and its full verbatim records (what states said). The same holds for the UN General Assembly , Human Rights Council and other organs of interest. These websites are generally self-explanatory, although they might be clunky sometimes, and the UN tends to move pages around for mysterious reasons. Explore a bit, and you will usually find what you need.

Last, sometimes you would want to get a general picture about how a specific incident, event, or issue was dealt with across the UN in a specific time. The best place to get this information is the Yearbook of the United Nations . Just look in the specific yearbook for the year in which your event of interest took place, and you will find summaries of the discussion of the issue across the UN. A huge bonus is that the yearbooks include an index of documents for each issue or event that you can then retrieve—using the document’s symbol—from the UN’s Official Document System. Note, however, that unfortunately the Yearbook is only published several years after the relevant year. As of 2020, the 2015 Yearbook hasn’t been released yet.

5. Practice and Statements

State practice and statements are important in order to ascertain customary international law, but also to understand general international approaches towards your question. At least for the latter purpose, the same holds with regard to practice and statements by international organizations and NGOs. Now, since state practice and statements can manifest in endless forms—from Twitter rants to official statements by heads of states (which are, nowadays, sometimes one and the same)—there is no one-stop shop for this type of primary source. Much can be found in UN documents, but this is by no means a comprehensive source because a lot of relevant interactions take place outside of the UN.

Nevertheless, some publications and other databases collect important pieces of (mainly state) practice. Just by way of example, each issue of the American Journal of International Law has a section on contemporary U.S. practice on international law. The U.S. State Department compiles an annual digest on U.S. State Practice, accessible here . German practice in international law can be found here (in English). Some other digests of state practice are listed by the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies library.

Additionally, after you select a research question, it is helpful to run a search and see if there is a subject-matter digest of practice relating to your question. For example, the Journal on the Use of Force and International Law includes, in each issue, a digest of practice on the use of force, divided by regions. The ICRC Customary Law Study website contains an updating database of practice on IHL. But again, these are only examples.

Unfortunately, a lot of relevant material is not compiled or indexed anywhere, and you will have to look for it in other places. Beyond the UN databases, you can find states’ positions in their governmental websites (typically the ministry of foreign affairs). NGO reports can be found in the specific organization’s website. A lot of information can be found in trustworthy media outlets (and we leave the discussion of what is “trustworthy” for another day). The New York Times’ searchable archive is a formidable tool for finding different positions of various actors in relation to current and historical events. For delving deeper, access into institutional archives might be needed.

Furthermore, sometimes, to gain access to relevant practice, you will need to search domestic legislation and rulings, beyond those found in the general databases mentioned above (such as the Oxford databases). Domestic legislation and rulings are especially pertinent when looking for “ general principles of law ,” which form a part of the sources of international law. [35] There is no single way to look for sources in domestic jurisdictions: each jurisdiction has its own system and databases. For instance, for English-speaking jurisdictions, Westlaw and Lexis are leading databases.

Last, nowadays, it is important not to neglect social media. For better or for worse, states and other international actors often share positions (and, ahem, insults) on Twitter. [36] These might also be relevant for your research.

III. Conclusion

All in all, there is no single way to think about any of the issues discussed in this guide. Some researchers will contest many of the definitions and suggestions offered here. This just serves to emphasize that determining the “best” way to approach research has a strong individual component. At least in legal research, beyond strict methodological requirements that might apply in socio-legal research, each researcher develops her own way and understandings as she gains knowledge and experience. I hope that this guide helps you to begin to find your own.

* Associate Professor, Tel Aviv University Buchmann Faculty of Law.

[1] See, e.g. , Martti Koskenniemi & Päivi Leino, Fragmentation of International Law? Postmodern Anxieties , 15 Leiden J. Int’l L. 553 (2002).

[2] Compare Monica Hakimi, Making Sense of Customary International Law , 118 Mich. L. Rev. 1487 (2020) with Kevin Jon Heller, Customary International Law Symposium: The Stubborn Tenacity of Secondary Rules , Opinio Juris (Jul. 7, 2020).

[3] Tom Ruys & Luca Ferro, Weathering the Storm: Legality and Legal Implications of the Saudi-Led Military Intervention in Yemen , 65 Int’l & Comp. L.Q. 61 (2016).

[4] Felix S. Cohen, Transcendental Nonsense and the Functional Approach , 35 Colum. L. Rev. 809 (1935).

[5] Anthea Roberts, Is International Law International? (2017).

[6] Eyal Benvenisti & Doreen Lustig, Monopolizing War: Codifying the Laws of War to Reassert Governmental Authority, 1856–1874 , 31 Eur. J. Int’l L. 127 (2020).

[7] Gabriella Blum, The Dispensable Lives of Soldiers , 2 J. Leg. Analysis 115 (2010).

[8] For an explanation, see Scott J. Shapiro, Legality 47–49 (2011).

[9] Andrea Bianchi, International Law Theories: An Inquiry into Different Ways of Thinking (2016).

[10] See Emmerich de Vattel, The Law of Nations, bk. I, ch. IV, §§38–39 (Béla Kapossy & Richard Whatmore eds., 2008) (1758).

[11] See, e.g. , Adil Ahmad Haque, Law and Morality at War (2017).

[12] Ronald Dworkin, Law’s Empire (1986).

[13] Thomas M. Franck, Legitimacy in the International System, 82 Am. J. Int’l L. 705 (1988)

[14] Jeffrey L. Dunoff & Joel P. Trachtman, Economic Analysis of International Law , 24 Yale J. Int’l L. 1 (1999).

[15] W. Michael Reisman, The View from the New Haven School of International Law , 86 Am. Soc’y Int’l L. Proc. 118 (1992).

[16] See Harlan Grant Cohen, Are We (Americans) All International Legal Realists Now?, in Concepts on International Law in Europe and the United States (Chiara Giorgetti & Guglielmo Verdirame, eds., forthcoming), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3025616.

[17] Martti Koskenniemi, What Is Critical Research in International Law? Celebrating Structuralism , 29 Leiden J. Int’l L. 727 (2016).

[18] Martti Koskenniemi, The Politics of International Law , 1 Eur. J. Int’l L. 4 (1999).

[19] Aeyal M. Gross, Human Proportions: Are Human Rights the Emperor’s New Clothes of the International Law of Occupation?, 18 Eur. J. Int’l L. 1 (2007).

[20] Antony Anghie, Francisco de Vitoria and the Colonial Origins of International Law , 5 Soc. & Leg. Stud. 321 (1996); see also Sundhya Pahuja, The Postcoloniality of International Law , 46 Harv. J. Int’l L. 459 (2005).

[21] Ntina Tzouvala, Civilization, in Concepts for International Law: Contributions to Disciplinary Thought 83 (Jean d’Aspremont & Sahib Singh eds., 2019).

[22] Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, The Gender of Occupation , 45 Yale J. Int’l L. 335 (2020).

[23] Steven R. Ratner & Anne-Marie Slaughter, Appraising the Methods of International Law: A Prospectus for Readers , 93 Am. J. Int’l L. 291, 292 (1999).

[24] Statute of the International Court of Justice, Art. 38(1)(d), June 26, 1945, 59 Stat. 1055, 33 U.N.T.S. 933.

[25] See Justina Uriburu, Between Elitist Conversations and Local Clusters: How Should we Address English-centrism in International Law?, Opinio Juris (Nov. 2, 2020), https://opiniojuris.org/2020/11/02/between-elitist-conversations-and-local-clusters-how-should-we-address-english-centrism-in-international-law/.

[26] See Cohen, supra note 15. See also William C. Banks & Evan J. Criddle, Customary Constraints on the Use of Force: Article 51 with an American Accent, 29 Leiden J. Int’l L. 67 (2016).

[27] David Luban, Military Necessity and the Cultures of Military Law , 26 Leiden J. Int’l L. 315 (2013); see also Eyal Benvenisti, The Legal Battle to Define the Law on Transnational Asymmetric Warfare , 20 Duke J. Comp. & Int’l L. 339, 348 (2010).

[28] 1 Lassa Oppenheim, International Law: A Treatise (1912).

[29] Jake Goldenfein, Sebastian Benthall, Daniel Griffin & Eran Toch, Private Companies and Scholarly Infrastructure — Google Scholar and Academic Autonomy (Oct. 28, 2019), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3476911.

[30] See, e.g. , Kenneth W. Abbott & Duncan Snidal, Hard and Soft Law in International Governance , 54 Int’l Org. 421 (2000).

[31] For this type of thinking, see Hakimi, supra note 2.

[32] See Ratner, supra note 23.

[33] See Koskenniemi, supra note 1.

[34] Harold Hongju Koh, Is there a “New” New Haven School of International Law? , 32 Yale J. Int’l L. 559 (2007).

[35] See, e.g. , M. Cherif Bassiouni, A Functional Approach to “General Principles of International Law” , 11 Mich J. Int’l L. 768 (1990).

[36] Francis Grimal, Twitter and the jus ad bellum: threats of force and other implications , 6 J. Use of Force & Int’l L. 183 (2019).

Dr. Eliav Lieblich is an Associate Professor at Tel-Aviv University’s Buchmann Faculty of Law. He teaches and researches public international law, with a focus on the laws on the use of force, just war theory, international humanitarian law, and the history and theory of international law. Dr. Lieblich has been awarded two Israel Science Foundations grants, as well as the Alon Fellowship for Outstanding young faculty, awarded by the Council of Higher Education. His scholarship was published, among others, in the European Journal of International Law, the British Yearbook of International Law, and the Hastings Law Journal.

Subscribe to Updates From HILJ

Type your email…

Legal Research Strategy

Preliminary analysis, organization, secondary sources, primary sources, updating research, identifying an end point, getting help, about this guide.

This guide will walk a beginning researcher though the legal research process step-by-step. These materials are created with the 1L Legal Research & Writing course in mind. However, these resources will also assist upper-level students engaged in any legal research project.

How to Strategize

Legal research must be comprehensive and precise. One contrary source that you miss may invalidate other sources you plan to rely on. Sticking to a strategy will save you time, ensure completeness, and improve your work product.

Follow These Steps

Running Time: 3 minutes, 13 seconds.

Make sure that you don't miss any steps by using our:

- Legal Research Strategy Checklist

If you get stuck at any time during the process, check this out:

- Ten Tips for Moving Beyond the Brick Wall in the Legal Research Process, by Marsha L. Baum

Understanding the Legal Questions

A legal question often originates as a problem or story about a series of events. In law school, these stories are called fact patterns. In practice, facts may arise from a manager or an interview with a potential client. Start by doing the following:

- Read anything you have been given

- Analyze the facts and frame the legal issues

- Assess what you know and need to learn

- Note the jurisdiction and any primary law you have been given

- Generate potential search terms

Jurisdiction

Legal rules will vary depending on where geographically your legal question will be answered. You must determine the jurisdiction in which your claim will be heard. These resources can help you learn more about jurisdiction and how it is determined:

- Legal Treatises on Jurisdiction

- LII Wex Entry on Jurisdiction

This map indicates which states are in each federal appellate circuit:

Getting Started

Once you have begun your research, you will need to keep track of your work. Logging your research will help you to avoid missing sources and explain your research strategy. You will likely be asked to explain your research process when in practice. Researchers can keep paper logs, folders on Westlaw or Lexis, or online citation management platforms.

Organizational Methods

Tracking with paper or excel.

Many researchers create their own tracking charts. Be sure to include:

- Search Date

- Topics/Keywords/Search Strategy

- Citation to Relevant Source Found

- Save Locations

- Follow Up Needed

Consider using the following research log as a starting place:

- Sample Research Log

Tracking with Folders

Westlaw and Lexis offer options to create folders, then save and organize your materials there.

- Lexis Advance Folders

- Westlaw Edge Folders

Tracking with Citation Management Software

For long term projects, platforms such as Zotero, EndNote, Mendeley, or Refworks might be useful. These are good tools to keep your research well organized. Note, however, that none of these platforms substitute for doing your own proper Bluebook citations. Learn more about citation management software on our other research guides:

- Guide to Zotero for Harvard Law Students by Harvard Law School Library Research Services Last Updated Sep 12, 2023 266 views this year

Types of Sources

There are three different types of sources: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary. When doing legal research you will be using mostly primary and secondary sources. We will explore these different types of sources in the sections below.

Secondary sources often explain legal principles more thoroughly than a single case or statute. Starting with them can help you save time.

Secondary sources are particularly useful for:

- Learning the basics of a particular area of law

- Understanding key terms of art in an area

- Identifying essential cases and statutes

Consider the following when deciding which type of secondary source is right for you:

- Scope/Breadth

- Depth of Treatment

- Currentness/Reliability

For a deep dive into secondary sources visit:

- Secondary Sources: ALRs, Encyclopedias, Law Reviews, Restatements, & Treatises by Catherine Biondo Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 4574 views this year

Legal Dictionaries & Encyclopedias

Legal dictionaries.

Legal dictionaries are similar to other dictionaries that you have likely used before.

- Black's Law Dictionary

- Ballentine's Law Dictionary

Legal Encyclopedias

Legal encyclopedias contain brief, broad summaries of legal topics, providing introductions and explaining terms of art. They also provide citations to primary law and relevant major law review articles.

Here are the two major national encyclopedias:

- American Jurisprudence (AmJur) This resource is also available in Westlaw & Lexis .

- Corpus Juris Secundum (CJS)

Treatises are books on legal topics. These books are a good place to begin your research. They provide explanation, analysis, and citations to the most relevant primary sources. Treatises range from single subject overviews to deep treatments of broad subject areas.

It is important to check the date when the treatise was published. Many are either not updated, or are updated through the release of newer editions.

To find a relevant treatise explore:

- Legal Treatises by Subject by Catherine Biondo Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 3590 views this year

American Law Reports (ALR)

American Law Reports (ALR) contains in-depth articles on narrow topics of the law. ALR articles, are often called annotations. They provide background, analysis, and citations to relevant cases, statutes, articles, and other annotations. ALR annotations are invaluable tools to quickly find primary law on narrow legal questions.

This resource is available in both Westlaw and Lexis:

- American Law Reports on Westlaw (includes index)

- American Law Reports on Lexis

Law Reviews & Journals

Law reviews are scholarly publications, usually edited by law students in conjunction with faculty members. They contain both lengthy articles and shorter essays by professors and lawyers. They also contain comments, notes, or developments in the law written by law students. Articles often focus on new or emerging areas of law and may offer critical commentary. Some law reviews are dedicated to a particular topic while others are general. Occasionally, law reviews will include issues devoted to proceedings of panels and symposia.

Law review and journal articles are extremely narrow and deep with extensive references.

To find law review articles visit:

- Law Journal Library on HeinOnline

- Law Reviews & Journals on LexisNexis

- Law Reviews & Journals on Westlaw

Restatements

Restatements are highly regarded distillations of common law, prepared by the American Law Institute (ALI). ALI is a prestigious organization comprised of judges, professors, and lawyers. They distill the "black letter law" from cases to indicate trends in common law. Resulting in a “restatement” of existing common law into a series of principles or rules. Occasionally, they make recommendations on what a rule of law should be.

Restatements are not primary law. However, they are considered persuasive authority by many courts.

Restatements are organized into chapters, titles, and sections. Sections contain the following:

- a concisely stated rule of law,

- comments to clarify the rule,

- hypothetical examples,

- explanation of purpose, and

- exceptions to the rule

To access restatements visit:

- American Law Institute Library on HeinOnline

- Restatements & Principles of the Law on LexisNexis

- Restatements & Principles of Law on Westlaw

Primary Authority

Primary authority is "authority that issues directly from a law-making body." Authority , Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). Sources of primary authority include:

- Constitutions

- Statutes

Regulations

Access to primary legal sources is available through:

- Bloomberg Law

- Free & Low Cost Alternatives

Statutes (also called legislation) are "laws enacted by legislative bodies", such as Congress and state legislatures. Statute , Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

We typically start primary law research here. If there is a controlling statute, cases you look for later will interpret that law. There are two types of statutes, annotated and unannotated.

Annotated codes are a great place to start your research. They combine statutory language with citations to cases, regulations, secondary sources, and other relevant statutes. This can quickly connect you to the most relevant cases related to a particular law. Unannotated Codes provide only the text of the statute without editorial additions. Unannotated codes, however, are more often considered official and used for citation purposes.

For a deep dive on federal and state statutes, visit:

- Statutes: US and State Codes by Mindy Kent Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 2958 views this year

- 50 State Surveys

Want to learn more about the history or legislative intent of a law? Learn how to get started here:

- Legislative History Get an introduction to legislative histories in less than 5 minutes.

- Federal Legislative History Research Guide

Regulations are rules made by executive departments and agencies. Not every legal question will require you to search regulations. However, many areas of law are affected by regulations. So make sure not to skip this step if they are relevant to your question.

To learn more about working with regulations, visit:

- Administrative Law Research by AJ Blechner Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 572 views this year

Case Basics

In many areas, finding relevant caselaw will comprise a significant part of your research. This Is particularly true in legal areas that rely heavily on common law principles.

Running Time: 3 minutes, 10 seconds.

Unpublished Cases

Up to 86% of federal case opinions are unpublished. You must determine whether your jurisdiction will consider these unpublished cases as persuasive authority. The Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure have an overarching rule, Rule 32.1 Each circuit also has local rules regarding citations to unpublished opinions. You must understand both the Federal Rule and the rule in your jurisdiction.

- Federal and Local Rules of Appellate Procedure 32.1 (Dec. 2021).

- Type of Opinion or Order Filed in Cases Terminated on the Merits, by Circuit (Sept. 2021).

Each state also has its own local rules which can often be accessed through:

- State Bar Associations

- State Courts Websites

First Circuit

- First Circuit Court Rule 32.1.0

Second Circuit

- Second Circuit Court Rule 32.1.1

Third Circuit

- Third Circuit Court Rule 5.7

Fourth Circuit

- Fourth Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Fifth Circuit

- Fifth Circuit Court Rule 47.5

Sixth Circuit

- Sixth Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Seventh Circuit

- Seventh Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Eighth Circuit

- Eighth Circuit Court Rule 32.1A

Ninth Circuit

- Ninth Circuit Court Rule 36-3

Tenth Circuit

- Tenth Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Eleventh Circuit

- Eleventh Circuit Court Rule 32.1

D.C. Circuit

- D.C. Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Federal Circuit

- Federal Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Finding Cases

Headnotes show the key legal points in a case. Legal databases use these headnotes to guide researchers to other cases on the same topic. They also use them to organize concepts explored in cases by subject. Publishers, like Westlaw and Lexis, create headnotes, so they are not consistent across databases.

Headnotes are organized by subject into an outline that allows you to search by subject. This outline is known as a "digest of cases." By browsing or searching the digest you can retrieve all headnotes covering a particular topic. This can help you identify particularly important cases on the relevant subject.

Running Time: 4 minutes, 43 seconds.

Each major legal database has its own digest:

- Topic Navigator (Lexis)

- Key Digest System (Westlaw)

Start by identifying a relevant topic in a digest. Then you can limit those results to your jurisdiction for more relevant results. Sometimes, you can keyword search within only the results on your topic in your jurisdiction. This is a particularly powerful research method.

One Good Case Method

After following the steps above, you will have identified some relevant cases on your topic. You can use good cases you find to locate other cases addressing the same topic. These other cases often apply similar rules to a range of diverse fact patterns.

- in Lexis click "More Like This Headnote"

- in Westlaw click "Cases that Cite This Headnote"

to focus on the terms of art or key words in a particular headnote. You can use this feature to find more cases with similar language and concepts.

Ways to Use Citators

A citator is "a catalogued list of cases, statutes, and other legal sources showing the subsequent history and current precedential value of those sources. Citators allow researchers to verify the authority of a precedent and to find additional sources relating to a given subject." Citator , Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

Each major legal database has its own citator. The two most popular are Keycite on Westlaw and Shepard's on Lexis.

- Keycite Information Page

- Shepard's Information Page

Making Sure Your Case is Still Good Law

This video answers common questions about citators:

For step-by-step instructions on how to use Keycite and Shepard's see the following:

- Shepard's Video Tutorial

- Shepard's Handout

- Shepard's Editorial Phrase Dictionary

- KeyCite Video Tutorial

- KeyCite Handout

- KeyCite Editorial Phrase Dictionary

Using Citators For

Citators serve three purposes: (1) case validation, (2) better understanding, and (3) additional research.

Case Validation

Is my case or statute good law?

- Parallel citations

- Prior and subsequent history

- Negative treatment suggesting you should no longer cite to holding.

Better Understanding

Has the law in this area changed?

- Later cases on the same point of law

- Positive treatment, explaining or expanding the law.

- Negative Treatment, narrowing or distinguishing the law.

Track Research

Who is citing and writing about my case or statute?

- Secondary sources that discuss your case or statute.

- Cases in other jurisdictions that discuss your case or statute.

Knowing When to Start Writing

For more guidance on when to stop your research see:

- Terminating Research, by Christina L. Kunz

Automated Services

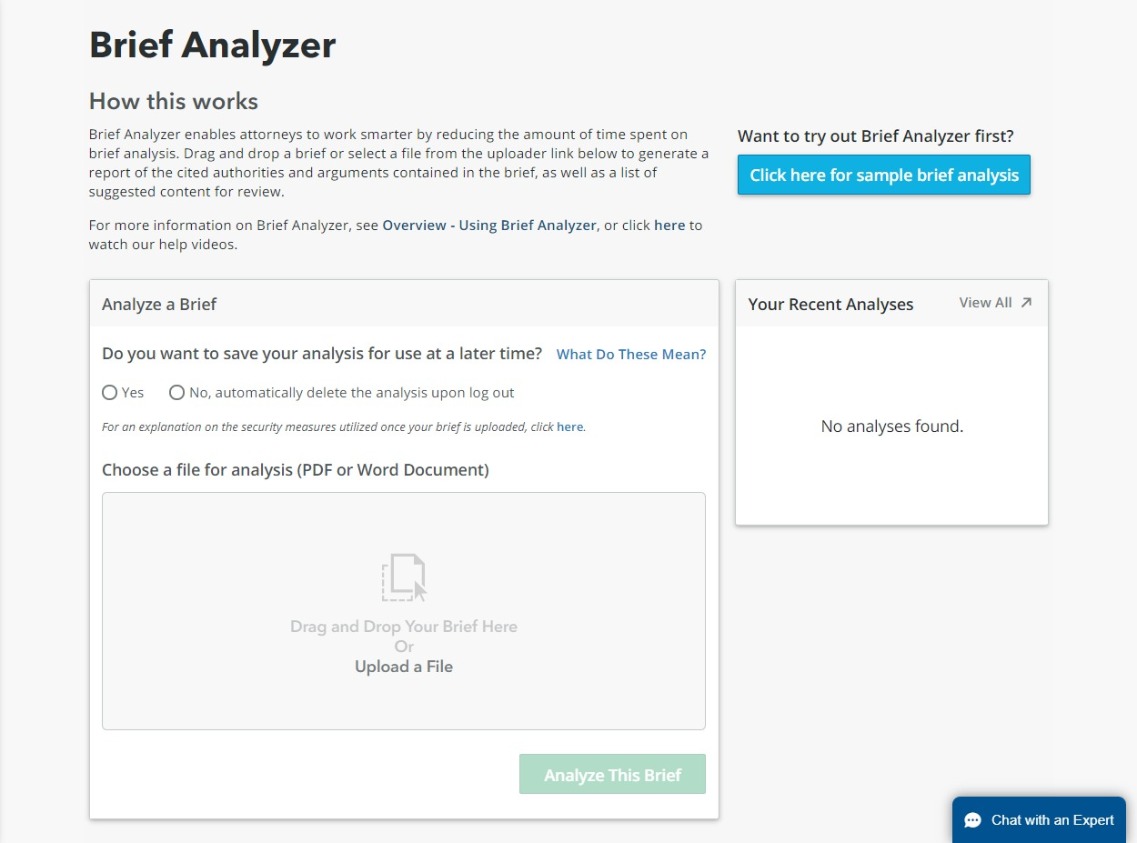

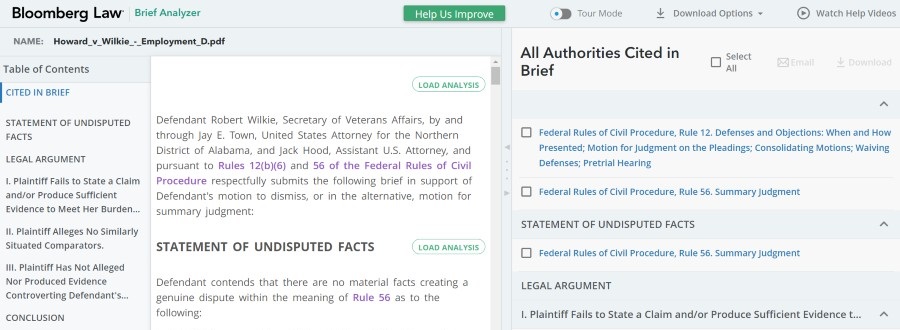

Automated services can check your work and ensure that you are not missing important resources. You can learn more about several automated brief check services. However, these services are not a replacement for conducting your own diligent research .

- Automated Brief Check Instructional Video

Contact Us!

Ask Us! Submit a question or search our knowledge base.

Chat with us! Chat with a librarian (HLS only)

Email: [email protected]

Contact Historical & Special Collections at [email protected]

Meet with Us Schedule an online consult with a Librarian