Chapter 2: Developmental Theories

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Define theory

- Describe Freud’s theory of psychosexual development

- Identify the parts of the self in Freud’s model

- List five defense mechanisms

- Describe five defense mechanisms

- Appraise the strengths and weaknesses of Freud’s theory

- List Erikson’s eight stages of psychosocial development

- Apply Erikson’s stages to examples of people in various stages of the lifespan

- Appraise the strengths and weaknesses of Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development

- Compare and contrast Freud’s and Erikson’s theories of human development

- Describe the principles of classical conditioning

- Identify unconditioned stimulus, conditioned stimulus, unconditioned response, and conditioned response in classical conditioning

- Describe the principles of operant conditioning

- Identify positive and negative reinforcement and primary and secondary reinforcement

- Contrast reinforcement and punishment

- Contrast classical and operant conditioning and the kinds of behaviors learned in each

- Describe social learning theory

- Describe Piaget’s theory of cognitive development

- Define schema, assimilation, accommodation, and cognitive equilibrium

- List Piaget’s stages of cognitive development

- Describe Piaget’s stages of cognitive development

- Critique Piaget’s theory of cognitive development

- Describe Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of cognitive development

- Explain what is meant by the zone of proximal development

- Explain guided participation

- Describe scaffolding

- Compare Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s models of cognitive development

- Describe Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model

What Is a Theory?

Students sometimes feel intimidated by theory; even the phrase, “Now we are going to look at some theories…” is met with blank stares and other indications that the audience is now lost. But theories are valuable tools for understanding human behavior; they are proposed explanations for the “hows” and “whys” of development. Have you ever wondered, “Why is my 3-year-old so inquisitive?” or “Why do their classmates reject some fifth graders?” Theories can help explain these and other occurrences. Developmental theories explain how we develop, why we change over time, and the influences that impact development.

A theory guides and helps us interpret research findings as well. It gives the researcher a blueprint or model to help piece together various studies. Theories are guidelines, like directions with an appliance or other object requiring assembly. The instructions can help one piece together smaller parts more quickly than if trial and error are used.

Theories can be developed using induction in which several single cases are observed, and after patterns or similarities are noted, the theorist generates ideas based on these examples. Established theories are tested through research; however, not all theories are equally suited to scientific investigation. Some theories are complex to try but are still valuable for stimulating debate or providing concepts that have practical applications. Remember that theories are not facts; they are guidelines for investigation and practice, and they gain credibility through research that fails to disprove them.

Psychodynamic Theory

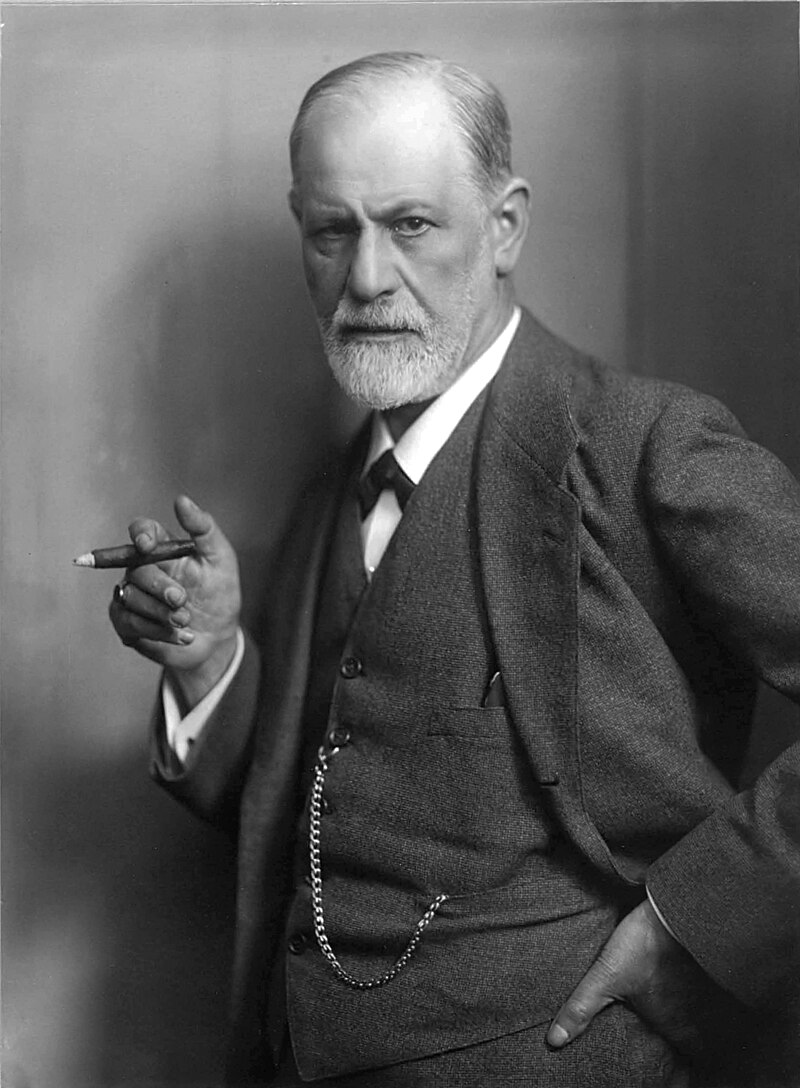

We begin with the often-controversial figure, Sigmund Freud. Freud has been a very influential figure in development; his view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviorism in the 1950s. His assumptions that personality forms during the first few years of life and that how parents or other caregivers interact with children has a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states have guided parents, educators, clinicians, and policy-makers for many years. We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states. A growing body of literature addresses resiliency in children from harsh backgrounds yet develops without damaging emotional scars (O’Grady and Metz, 1987). Freud has stimulated an enormous amount of research and generated many ideas. Agreeing with Freud’s theory in its entirety is hardly necessary for appreciating the contribution he has made to the field of development.

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) was a Viennese M. D. who was trained in neurology and asked to work with patients suffering from hysteria, a condition marked by uncontrollable emotional outbursts, fears, and anxiety that had puzzled physicians for centuries. He was also asked to work with women who suffered from physical symptoms and forms of paralysis that had no organic causes. During that time, many people believed that certain individuals were genetically inferior and thus more susceptible to mental illness. Women were thought to be genetically inferior and therefore prone to diseases such as hysteria (which had previously been attributed to a detached womb that was traveling around in the body).

However, after World War I, many soldiers came home with problems similar to hysteria. This called into question the idea of genetic inferiority as a cause of mental illness. Freud began working with hysterical patients and discovered that when they started to talk about some of their life experiences, particularly those that took place in early childhood, their symptoms disappeared. This led him to suggest the first purely psychological explanation for physical problems and mental illness. He proposed that unconscious motives, desires, fears, and anxieties drive our actions. When upsetting memories or thoughts find their way into our consciousness, we develop defenses to shield us from these painful realities. These defense mechanisms include denying a reality, repressing or pushing away sad thoughts, rationalizing or finding a seemingly logical explanation for circumstances, projecting or attributing our feelings to someone else, or outwardly opposing something we inwardly desire (reaction formation). Freud believed that many mental illnesses are a result of a person’s inability to accept reality. Freud emphasized the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping our personality and behavior . In our natural state, we are biological beings. We are driven primarily by instincts. During childhood, however, we become social beings as we learn how to manage our instincts and transform them into socially acceptable behaviors. The parenting the child receives has a powerful impact on the child’s personality development. We will explore this idea further in our discussion of psychosexual development.

Theory of the Mind

Freud believed that most mental processes, motivations, and desires are beyond our awareness. Our consciousness, of which we are aware, represents only the tip of the iceberg that comprises our mental state. The preconscious means that which can easily be called into the conscious mind. During development, our motivations and desires are gradually pushed into the unconscious because raw desires are often unacceptable.

Theory of the Self

As adults, our personality or self consists of three main parts: the id , the ego, and the superego . The id, present at birth, consists of our instincts and drives. It is the part of us that wants immediate gratification. Later in life, it comes to house our deepest, often socially unacceptable desires, such as sex and aggression. It operates under the pleasure principle, which means that the criterion for determining whether something is good or bad is whether it feels good or bad. An infant uses the id self. The ego is the part of the self that develops as we learn that there are limits on what is acceptable and that we often must wait to satisfy our needs. This part of the self is realistic and reasonable. It knows how to make compromises. It operates under the reality principle or the recognition that sometimes gratification must be postponed for practical reasons. It acts as a mediator between the id and the superego and is viewed as the healthiest part of the self.

Defense mechanisms emerge to help a person distort reality so that the truth is less painful. Defense mechanisms include repression, which means pushing the painful thoughts out of consciousness (in other words, thinking about something else). Denial is not accepting the truth or lying to the self. Thoughts such as “It won’t happen to me,” “You’re not leaving,” or “I don’t have a problem with alcohol” are examples. Regression refers to returning to a time when the world felt safer, perhaps reverting to one’s childhood. This is less common than the first two defense mechanisms. Sublimation involves transforming unacceptable urges into more socially acceptable behaviors. For example, a teenager who experiences strong sexual urges uses exercise to redirect those urges into more socially acceptable behavior. Displacement involves taking out frustrations on a safer target. A person who is angry at a boss may take out their frustration on others when driving home or on a spouse upon arrival. Projection is a defense mechanism in which people attribute their unacceptable thoughts to others. If someone is frightened, for example, they accuse someone else of fear. Finally, reaction formation is a defense mechanism in which a person outwardly opposes something they inwardly desire, which they find unacceptable. An example of this might be homophobia or an intense hatred and fear of homosexuality.

This is a partial listing of defense mechanisms suggested by Freud. If the ego is strong, the individual is realistic and accepting of reality and remains more logical, objective, and reasonable. Building ego strength is a significant goal of psychoanalysis (Freudian psychotherapy). So, for Freud, having a big ego is a good thing because it does not refer to being arrogant; it relates to being able to accept reality.

The superego is the part of the self that develops as we learn society’s rules, standards, and values. This part of the self considers the moral guidelines that are a part of our culture. It is a rule-governed part of the self that operates under a sense of guilt (guilt is a social emotion—it is a feeling that others think less of you or believe you to be wrong). If a person violates the superego, they feel guilty. The superego is helpful but can be too strong; in this case, a person might feel overly anxious and guilty about circumstances over which they had no control. Such a person may experience high stress and inhibition levels that keep them from living well. The id is inborn, but the ego and superego develop during our early interactions with others. These interactions occur against a backdrop of learning to resolve early biological and social challenges and play a key role in our personality development.

Psychosexual Stages

Freud believed that development occurs in a series of stages. At each stage, one will either successfully move through that stage and that stage is resolved or will experience challenges and become fixated in that stage. At any of these stages, the child might become “stuck” or fixated if a caregiver either overly indulges or neglects the child’s needs. A fixated adult will continue to try and resolve this later in life. Examples of fixation are given after the presentation of each stage.

From birth through the first year of life, the infant is in the oral stage of psychosexual development. The infant’s needs are met primarily through oral gratification. A baby wishes to suck or chew on any object that comes close to the mouth. Babies explore the world through the mouth and find comfort and stimulation. Psychologically, the infant is in the id. The infant seeks immediate gratification of comfort, warmth, food, and stimulation. If the caregiver meets oral needs consistently, the child will move away from this stage and progress to the next stage. However, if the caregiver is inconsistent or neglectful, the person may stay in the oral stage. As an adult, the person might not feel good unless involved in some oral activity such as eating, drinking, smoking, nail-biting, or compulsive talking. These actions bring comfort and security when the person feels insecure, afraid, or bored.

During the anal stage, which coincides with toddlerhood (ages 1-3) or mobility and potty training, the child is taught that some urges must be contained and some actions postponed. There are rules about certain functions and when and where they will be carried out. The child is learning a sense of self-control. The ego is being developed. If the caregiver is highly controlling about potty training (stands over the child waiting for the slightest indication that the child might need to go to the potty and immediately scoops the child up and places him on the potty chair, for example), the child may grow up fearing losing control. He may become fixated in this stage or “anal retentive”—fearful of letting go. Such a person might be extremely neat and clean, organized, reliable, and controlling of others. If the caregiver neglects to teach the child to control urges, he may grow up to be “anal expulsive” or an adult who is messy, irresponsible, and disorganized.

The phallic stage occurs during preschool (ages 3-5) when the child faces a new biological challenge. Freud believed that the child becomes sexually attracted to their opposite-sexed parent. Boys experience the “Oedipal Complex,” in which they become sexually attracted to their mothers but realize that their father is in the way. He is much more powerful. For a while, the boy fears that if he pursues his mother, his father may castrate him (castration anxiety). So rather than risk losing his penis, he gives up his affection for his mother and instead learns to become more like his father, imitating his actions and mannerisms and thereby retaining the role of males in his society. From this experience, the boy learns a sense of masculinity. He also knows what society thinks he should do and experiences guilt if he does not comply. In this way, the superego develops. If he does not resolve this successfully, he may become a “phallic male” or a man who constantly tries to prove his masculinity (about which he is insecure) by seducing women and beating up men! A little girl experiences the “Electra Complex,” in which she develops an attraction for her father but realizes that she cannot compete with her mother, so she gives up that affection and learns to become more like her mother. This is not without some regret, however. Freud believed that the girl feels inferior because she does not have a penis (experiences “penis envy”). But she must resign herself to the fact that she is female and will have to learn her inferior role in society as a female. However, if she does not resolve this conflict successfully, she may have a weak sense of femininity and grow up to be a “castrating female” who tries to compete with men in the workplace or other areas of life.

During middle childhood (6-12), the child enters the latent stage, focusing their attention outside the family and toward friendships. The biological drives are temporarily quieted (latent), and the child can direct attention to a larger world of friends. If the child can make friends, they will gain confidence. If not, the child may remain a loner or shy away from others, even as an adult.

The final stage of psychosexual development is referred to as the genital stage . From adolescence through adulthood, a person is preoccupied with sex and reproduction. The adolescent experiences rising hormone levels, and the sex drive and hunger drives become very strong. Ideally, the adolescent will rely on the ego to help think logically through these urges without taking actions that might be damaging. An adolescent might learn to redirect their sexual urges into safer activities such as running, for example. Quieting the id with the superego can lead to feeling overly self-conscious and guilty about these urges. Hopefully, the ego is strengthened during this stage, and the adolescent uses reason to manage urges.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Freud’s Theory

Freud’s theory has been heavily criticized for several reasons. One is that it is tough to test scientifically. How can parenting in infancy be traced to personality in adulthood? Are there other variables that might better explain development? The theory is also considered to be sexist in suggesting that women who do not accept an inferior position in society are somehow psychologically flawed. Freud focuses on the darker side of human nature, meaning that much of what determines our actions is unknown. So why do we study Freud? As mentioned above, despite the criticisms, Freud’s assumptions about the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping our psychological selves have found their way into child development, education, and parenting practices. Freud’s theory has heuristic value in providing a framework to elaborate and modify subsequent development theories. Many later theories, particularly behaviorism and humanism, challenged Freud’s views.

Psychosocial Theory

The ego rules.

Erik Erikson (1902–1994) was a student of Freud who believed that relationships, not sex and aggression, were the motivators of development. Erikson’s psychosocial theory of development emphasizes that we are aware of what motivates us throughout life, and the ego has greater importance in guiding our actions than the id (Erikson, 1950; 1968). We make conscious choices, focusing on meeting specific social and cultural needs rather than purely biological ones. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can contribute to society, and that we have lived meaningful lives. These are all psychosocial problems. Erikson divided the lifespaninto eight stages. In each phase, we have a significant psychosocial task to address. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our lifespanas we face these challenges in living. We will discuss each of these stages in length as we explore each period of the life span, but here is a brief overview:

Psychosocial Stages

- Trust vs. mistrust (0-1): the infant must have basic needs met consistently to feel that the world is a trustworthy place.

- Autonomy vs. shame and doubt (1-2): mobile toddlers have newfound freedom. They like to exercise, and by being allowed to do so, they learn some essential independence.

- Initiative vs. guilt (3-5): preschoolers like to initiate activities and emphasize doing things “all by myself.”

- Industry vs. inferiority (6-11): school-aged children focus on accomplishments and begin making comparisons between themselves and their classmates.

- Identity vs. role confusion (adolescence): teenagers are trying to gain a sense of identity as they experiment with various roles, beliefs, and ideas.

- Intimacy vs. isolation (young adulthood): in our 20s and 30s, we are making some of our first long-term commitments in intimate relationships.

- Generativity vs. stagnation (middle adulthood): from the 40s through the early 60s, we focus on being productive at work and home and are motivated by wanting to feel that we’ve contributed to society.

- Integrity vs. despair (late adulthood): we look back on our lives and hope to like what we see—that we have lived well and have a sense of integrity because we lived according to our beliefs.

These eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the life span. However, remember that these stages or crises can occur more than once. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy under certain circumstances. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that completing one stage is a prerequisite for the subsequent development crisis. His theory also focuses on the social expectations in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States but not as well in cultures where adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices.

Exploring Behavior

Why do we do what we do.

Learning theories focus on how we respond to events or stimuli rather than emphasizing what motivates our actions. These theories explain how experience can change what we can do or feel.

Classical Conditioning and Emotional Responses

Classical conditioning theory helps us to understand how our responses to one situation become attached to new situations. For example, a smell might remind us of when we were kids (elementary school cafeterias smell like milk and mildew!). Going to a new cafeteria with the same smell might evoke feelings you had when you were in school. Or a song on the radio might remind you of a memorable evening you spent with your first true love. Or, if you hear your entire name (John Wilmington Brewer, for instance) called as you walk across the stage to get your diploma, it makes you tense because it reminds you of how your father used to use your full name when he was mad at you, you’ve been classically conditioned!

Classical conditioning explains how we develop many emotional responses to people or events or our “gut-level” reactions to situations. New situations may bring an old response because the two have become connected. Attachments form in this way. Addictions are affected by classical conditioning, as anyone who’s tried to quit smoking can tell you. When you try to stop, everything that is associated with smoking makes you crave a cigarette.

Ivan Pavlov (1880–1937) was a Russian physiologist interested in studying digestion. As he recorded the salivation his laboratory dogs produced as they ate, he noticed that they began to salivate before the food arrived as the researcher walked down the hall and toward the cage. “This,” he thought, “is not natural!” One would expect a dog to salivate when the food hits their palate automatically, but BEFORE the food comes? Of course, what had happened was . . . you tell me. That’s right! The dogs knew the food was coming because they had learned to associate the footsteps with the food. The key word here is “learned.” A learned response is called a “conditioned” response. Pavlov began to experiment with this “psychic” reflex. For instance, he began to ring a bell before introducing the food. Sure enough, after making this connection several times, the dogs could be made to salivate to the sound of a bell.

Once the bell had become an event to which the dogs had learned to salivate, it was called a conditioned stimulus. The act of salivating to a bell was a response that had also been learned, now termed in Pavlov’s jargon, a conditioned response. Notice that the response, salivation, is the same whether it is conditioned or unconditioned (unlearned or natural). What changed is the stimulus to which the dog salivates. One is natural (unconditioned) and learned (conditioned). Well, enough of Pavlov’s dogs. Who cares? Let’s think about how classical conditioning is used on us. One of the most widespread applications of classical conditioning principles was brought to us by the psychologist John B. Watson.

Watson and Behaviorism

John B. Watson believed most fears and other emotional responses are classically conditioned. He had gained popularity in the 1920s with his expert parenting advice offered to the public. He believed that parents could be taught to help shape their children’s behavior. He tried to demonstrate the power of classical conditioning with his famous experiment with an 18-month-old boy named “Little Albert.” Watson sat Albert down and introduced a variety of seemingly scary objects to him: a burning piece of newspaper, a white rat, etc. But Albert remained curious and reached for all of these things. Watson knew that one of our only inborn fears was the fear of loud noises, so he made a loud noise each time he introduced one of Albert’s favorites, a white rat. After hearing the loud noise paired with the rat several times, Albert soon came to fear it and began to cry when it was introduced. Watson filmed this experiment for posterity and used it to demonstrate that he could help parents achieve any desired outcomes if they would only follow his advice. Watson wrote columns in newspapers and magazines, gaining popularity among parents eager to apply science to household order. Parenting advice was not the legacy Watson left us, however. He made his impact in advertising. After Watson left academia, he went into the business world and showed companies how to tie something that brings a natural positive feeling to their products to enhance sales. Thus, the union of sex and advertising! So, let’s use a much more interesting example than Pavlov’s dogs to check and see if you understand the difference between conditioned and unconditioned stimuli and responses. In the experiment with Little Albert, identify the unconditioned stimulus, the unconditioned response, and, after conditioning, the conditioned stimulus and the conditioned response.

Operant Conditioning and Repeating Actions

Operant conditioning is another learning theory emphasizing a more conscious type of learning than classical conditioning. A person (or animal) does something (operates something) to see what effect it might bring. Simply said, operant conditioning describes how we repeat behaviors because they pay off for us. It is based on a principle authored by a psychologist named Thorndike (1874–1949) called the law of effect. The law of effect suggests that we will repeat an action if a sound effect follows it.

Skinner and Reinforcement

Watch how a pigeon learns through reinforcement:

B. F. Skinner (1904–1990) expanded on Thorndike’s principle and outlined the principles of operant conditioning. Skinner believed that we know best when our actions are reinforced. For example, a child who cleans his room and is supported (rewarded) with a big hug and words of praise is more likely to clean it again than a child whose deed goes unnoticed. Skinner believed that almost anything could be reinforcing. A reinforcer is anything following a behavior that makes it more likely to occur again. It can be something intrinsically rewarding (intrinsic or primary reinforcers), such as food or praise, or rewarding because it can be exchanged for what one wants (such as using money to buy a cookie). Such reinforcers are referred to as secondary reinforcers or extrinsic reinforcers.

Positive and Negative Reinforcement

Sometimes, adding something to the situation reinforces, as in the cases we described above, with cookies, praise, and money. Positive reinforcement involves adding something to the situation to encourage a behavior. Other times, taking something away from a problem can be reinforcing. For example, the loud, annoying buzzer on your alarm clock enables you to get up to turn it off and eliminate the noise. Children whine to get their parents to do something, and often, parents give in to stop the whining. In these instances, negative reinforcement has been used.

Operant conditioning tends to work best if you focus on encouraging a behavior or moving a person in the direction you want them to rather than telling them what not to do. Reinforcers are used to promote a behavior; punishers are used to stop the behavior. A punisher is anything that follows an act and decreases the chance it will reoccur. But often, a punished behavior doesn’t go away. It is suppressed and may reoccur whenever the threat of punishment is removed. For example, a child may not cuss around you because you’ve washed his mouth out with soap, but he may curse around his friends. Or a motorist may only slow down when the trooper is on the side of the freeway. Another problem with punishment is that when a person focuses on punishment, they may find it hard to see what the other does right or well. Punishment is stigmatizing; when punished, some start to see themselves as bad and give up trying to change.

Reinforcement can occur predictably, such as after every desired action is performed, intermittently after the behavior is performed several times, or the first time after a certain amount of time. The schedule of reinforcement has an impact on how long a behavior continues after reinforcement is discontinued. So, a parent who has rewarded a child’s actions each time may find that the child gives up very quickly if a reward is not immediately forthcoming. A lover warmly regarded now and then may continue seeking their partner’s attention long after the partner has tried to break up. Think about the behaviors you may have learned through classical and operant conditioning. You may have learned many things in this way. But sometimes, we learn very complex behaviors quickly and without direct reinforcement. Bandura explains how.

Social Learning Theory

Albert Bandura is a leading contributor to social learning theory. He calls our attention to how many of our actions are not learned through conditioning but learned by watching others (1977). Young children frequently learn behaviors through imitation. Sometimes, particularly when we do not know what else to do, we learn by modeling or copying the behavior of others. On their first day of a new job, an employee might eagerly look at how others are acting and try to act the same way to fit in more quickly. Adolescents struggling with their identity rely heavily on their peers to serve as role models. Newly married couples often rely on roles they may have learned from their parents and begin to act in ways they did not while dating and then wonder why their relationship has changed. Sometimes, we do things because we’ve seen it pay off for someone else. They were operantly conditioned, but we engage in the behavior because we hope it will also pay off for us. This is vicarious reinforcement (Bandura, Ross, and Ross, 1963).

Do Parents Socialize Children, or Do Children Socialize Parents?

Bandura (1986) suggests an interplay between the environment and the individual. We are not just the product of our surroundings; we influence our surroundings. There is an interplay between our personality, how we interpret events, and how they influence us. This concept is called reciprocal determinism. An example of this might be the interplay between parents and children. Parents not only influence their child’s environment, perhaps intentionally through reinforcement, etc., but children influence parents as well. Parents may respond differently with their first child than with their fourth. Perhaps they try to be the perfect parents with their firstborn, but by the time their last child comes along, they have very different expectations of themselves and their child. Our environment creates us, and we make our environment. Other social influences: TV or not TV? Bandura (et al. 1963) began a series of studies examining the impact of television, particularly commercials, on children’s behavior.

Are children more likely to act aggressively when this behavior is modeled? What if they see it being reinforced? Bandura began with an experiment showing children a film of a woman hitting an inflatable clown or “Bobo” doll. Then, the children were allowed into the room where they found the doll and immediately began to hit it. This was without any reinforcement whatsoever. Later, they viewed a woman hitting a real clown, and sure enough, when allowed in the room, they too began to hit the clown! Not only that, but they found new ways to behave aggressively. It’s as if they learned an aggressive role.

Watch Bandura’s Bobo-doll experiment:

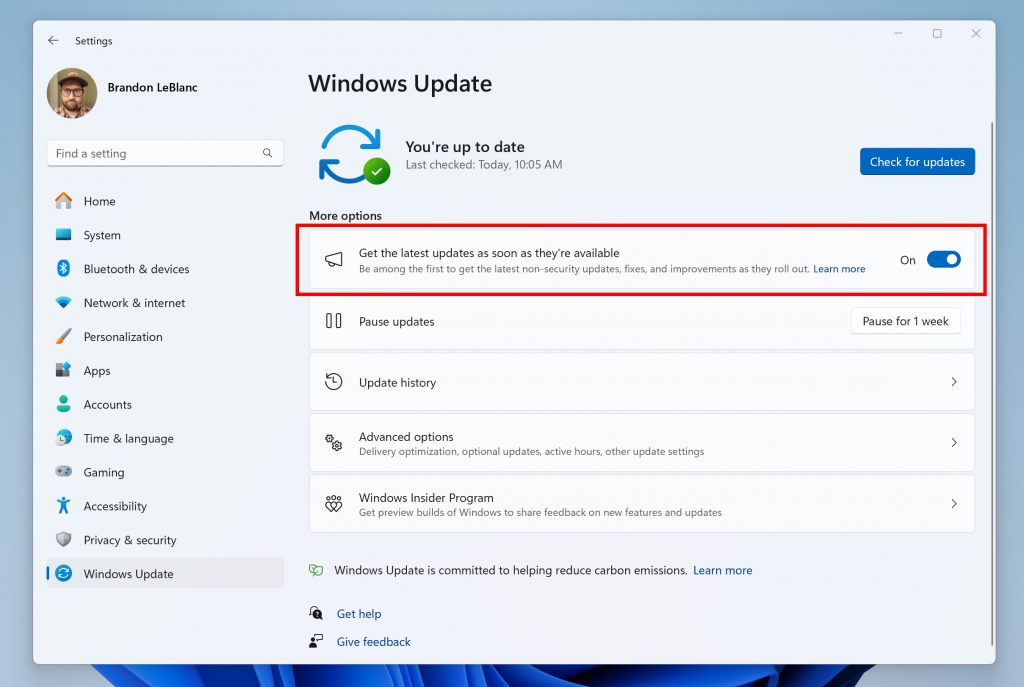

Children view far more television today than in the 1960s, so much so that they have been referred to as Generation M (media). Based on a study of a nationally representative sample of over 7,000 8-18-year-olds, the Kaiser Foundation reports that children spend just over 8 hours a day involved with media outside of schoolwork. This includes almost 4 hours of television viewing and over an hour on the computer. Two-thirds have television in their room, and those children watch an average of 1.27 hours more per day than those who do not have television in their bedroom (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2005). The prevalence of violence, sexual content, and messages promoting foods high in fat and sugar in the media are certainly cause for concern and the subjects of ongoing research and policy review. Many children spend even more time on the computer viewing content from the Internet. And the amount of time spent connected to the Internet continues to increase with smartphones that essentially serve as mini-computers. What are the implications of this?

Exploring Cognition

What do we think.

Cognitive theories focus on how our mental processes or cognitions change over time. We will examine the ideas of two cognitive theorists: Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky.

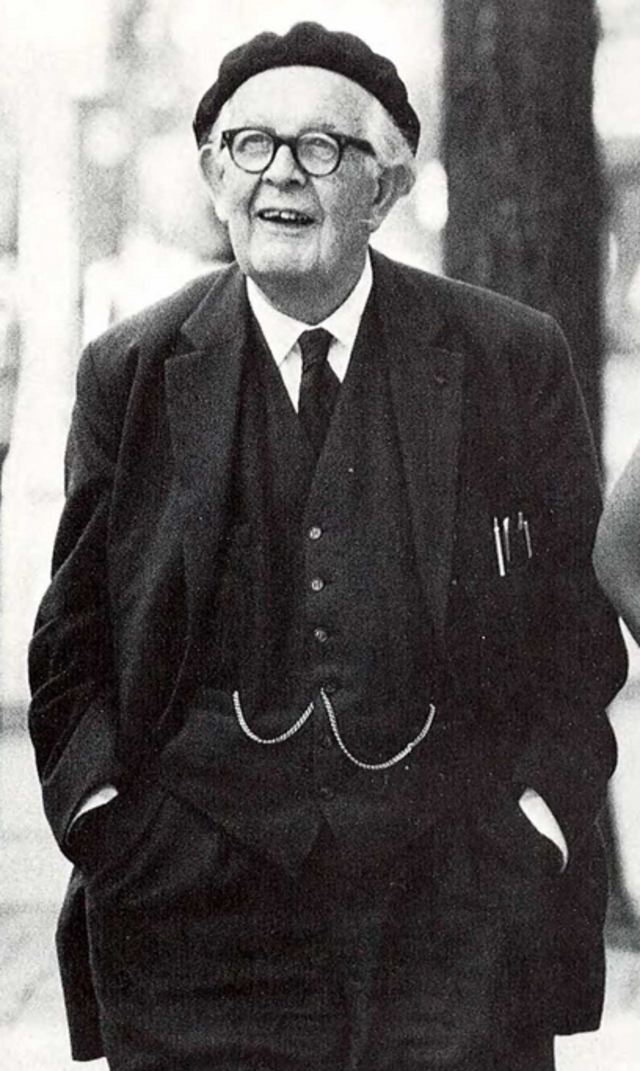

Piaget: Changes in Thought with Maturation

Jean Piaget (1896–1980) is one of the most influential cognitive theorists in development. He was inspired to explore children’s ability to think and reason by watching his own children’s development. He was one of the first to recognize and map out how children’s intelligence differs from that of adults. When asked to test children’s IQ, he became interested in this area and began noticing a pattern in their wrong answers! He believed that children’s intellectual skills change over time and that maturation rather than training brings about that change. Children of differing ages interpret the world differently.

Making Sense of the World

Piaget believed we continuously try to maintain cognitive equilibrium, balance, or cohesiveness in what we see and know. Children are more challenged in maintaining this balance because they are constantly confronted with new situations, words, objects, etc. When faced with something new, a child may either fit it into an existing framework ( schema ) and match it with something known ( assimilation ), such as calling all animals with four legs “doggies” because they see the word doggie, or expand the framework of knowledge to accommodate the new situation ( accommodation ) by learning a new word to name the animal more accurately. This is the underlying dynamic in our cognition. Even as adults, we try to “make sense” of new situations by determining whether they fit into our old thinking or need to modify our thoughts.

Stages of Cognitive Development

Piaget outlined four significant stages of cognitive development. Let me briefly mention them here. We will discuss them in detail throughout the course. For about the first two years of life, the child experiences the world primarily through their senses and motor skills. Piaget referred to this type of intelligence as sensorimotor intelligence. During preschool, the child begins to master symbols or words and can think of the world symbolically but not logically. This stage is the preoperational stage of development. The concrete operational stage in middle childhood is marked by an ability to use logic to understand the physical world. In the final formal operational stage, the adolescent learns to think abstractly and use logic in concrete and abstract ways.

Criticisms of Piaget’s Theory

Piaget has been criticized for overemphasizing physical maturation’s role in cognitive development and underestimating the role of culture and interaction (or experience) in cognitive development. Looking across cultures reveals considerable variation in what children can do at various ages. Piaget may have underestimated what children are capable of given the right circumstances.

Vygotsky: Changes in Thought with Guidance

Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) was a Russian psychologist who wrote in the early 1900s but whose work was discovered in the United States in the 1960s but became more widely known in the 1980s. Vygotsky differed from Piaget in that he believed that a person not only has a set of abilities but also a set of potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. His sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and interaction in developing cognitive skills. He believed that through guided participation, known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child can learn cognitive skills within a specific range, known as the zone of proximal development. Have you ever taught a child to perform a task? Maybe it was brushing their teeth or preparing food. Chances are you spoke to them and described what you were doing while you demonstrated the skill and let them work with you all through the process. You assisted them when they seemed to need it, but once they knew what to do, you stood back and let them go. This is scaffolding and can be seen demonstrated throughout the world. Educators have also adopted this approach to teaching. Rather than assessing students on what they are doing, they should be understood in terms of what they can do with the proper guidance. You can see how Vygotsky would be very popular with modern-day educators. We will discuss Vygotsky in greater depth in upcoming lessons.

Putting It All Together: Ecological Systems Model

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917–2005) provides a model of human development that addresses its many influences. Bronfenbrenner recognized that larger social forces influence human interaction and that understanding those forces is essential for understanding an individual. The individual is impacted by microsystems such as parents or siblings who have direct, significant contact with the person. The cognitive and biological state of the individual also modifies the input of those. These influence the person’s actions, which affect systems operating on them. The mesosystem includes larger organizational structures such as school, family, or religion. These institutions impact the microsystems just described. For example, religious teachings and traditions may guide the child’s family’s actions or create a climate that makes the family feel stigmatized, indirectly impacting the child’s view of self and others. The philosophy of the school system, daily routine, assessment methods, and other characteristics can affect the child’s self-image, growth, sense of accomplishment, and schedule, impacting the child physically, cognitively, and emotionally. These mesosystems both influence and are influenced by the larger contexts of community referred to as the ecosystem . A community’s values, history, and economy can impact its organizational structures. The community is influenced by macrosystems and cultural elements such as global economic conditions, war, technological trends, values, philosophies, and a society’s responses to the worldwide community. In sum, a child’s experiences are shaped by larger forces such as the family, schools, religion, and culture. All of this occurs in a historical context or chronosystem. Bronfenbrenner’s model helps us combine each of the other theories described above and gives us a perspective that brings it all together.

Research Designs

Observational studies involve watching and recording the actions of participants. This may occur in a natural setting, such as observing children playing at a park or behind a one-way glass while children play in a laboratory playroom. The researcher may follow a checklist and record the frequency and duration of events (perhaps how many conflicts occur among 2-year-olds) or may observe and register as much as possible about an event as a participant (such as attending an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting and recording the slogans on the walls, the structure of the meeting, the expressions commonly used, etc.). The researcher may be a participant or a non-participant. What would be the strengths of being a participant? What would be the weaknesses? Consider the strengths and weaknesses of not participating. In general, observational studies have the strength of allowing the researcher to see how people behave rather than relying on self-reporting. What people do and what they say they do are often very different. A significant weakness of observational studies is that they do not allow the researcher to explain causal relationships. Yet, observational studies are helpful and widely used when studying children. Children tend to change their behavior when they know they are being watched (the Hawthorne effect ) and may not survey well.

Experiments are designed to test hypotheses (or specific statements about the relationship between variables ) in a controlled setting to explain how certain factors or events produce outcomes. A variable is anything that changes in value. Concepts are operationalized or transformed into variables in research, meaning that the researcher must specify precisely what will be measured in the study. For example, suppose we are interested in studying marital satisfaction. In that case, we have to specify what marital satisfaction means or what we will use as an indicator of marital satisfaction. What is something measurable that would indicate some level of marital satisfaction? Would it be the amount of time couples spend together each day? Or eye contact during a discussion about money? Or maybe a subject’s score on a marital satisfaction scale? Each of these is measurable but may not be equally valid or accurate indicators of marital satisfaction. What do you think? These are the kinds of considerations researchers must make when working through the design.

Three conditions must be met to establish cause and effect. Experimental designs help meet these conditions.

The independent and dependent variables must be related. In other words, the other changes in response when one is altered. (The independent variable is something altered or introduced by the researcher. The dependent variable is the outcome or the factor affected by the introduction of the independent variable. For example, if we are looking at the impact of exercise on stress levels, the independent variable would be exercise; the dependent variable would be stress.)

The cause must come before the effect. Experiments involve measuring subjects on the dependent variable before exposing them to the independent variable (establishing a baseline). So, we would measure the subjects’ stress levels before introducing the exercise and then again after the exercise to see if there was a change in stress levels. (Observational and survey research does not always allow us to look at the timing of these events, making understanding causality problematic with these designs.)

The cause must be isolated. The researcher must ensure that no outside, perhaps unknown, variables are causing the effect we see. The experimental design helps make this possible. In an experiment, we would ensure that our subjects’ diets were constant throughout the exercise program. Otherwise, diet rather than exercise might create a change in stress levels.

A basic experimental design involves beginning with a sample (or population subset) and randomly assigning subjects to one of two experimental or control groups . The experimental group will be exposed to an independent variable or condition the researcher introduces as a potential cause of an event. The control group is going to be used for comparison. It will have the same experience as the experimental group but will not be exposed to the independent variable. After exposing the experimental group to the independent variable, the two groups are measured again to see if a change has occurred. If so, we are better positioned to suggest that the independent variable caused the shift in the dependent variable . The basic experimental model looks like this:

The experimental design’s primary advantage is that it helps establish cause-and-effect relationships. A disadvantage of this design is the difficulty translating much of what concerns us about human behavior into a laboratory setting. I hope this brief description of experimental design helps you appreciate the difficulty and the rigor of experimenting.

Case studies involve exploring a single case or situation in great detail. Information may be gathered using observation, interviews, testing, or other methods to uncover as much as possible about a person or situation. Case studies are helpful when investigating unusual situations such as brain trauma or children reared in isolation. They are often used by clinicians who conduct case studies as part of their regular practice when gathering information about a client or patient coming in for treatment. Case studies can be used to explore areas about which little is known and can provide rich detail about situations or conditions. However, the findings from case studies cannot be generalized or applied to larger populations because cases are not randomly selected, and no control group is used for comparison. (Read “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” by Dr. Oliver Sacks as an excellent example of the case study approach.)

Surveys are familiar to most people because they are so widely used. Surveys enhance accessibility to subjects because they can be conducted in person, over the phone, through the mail, or online. A survey involves asking a standard set of questions to subjects. In a highly structured survey, subjects must choose from a response set such as “strongly disagree, disagree, undecided, agree, strongly agree” or “0, 1-5, 6-10, etc.” Surveys are commonly used by sociologists, marketing researchers, political scientists, therapists, and others to gather information on many independent and dependent variables in a relatively short period. Surveys typically yield surface information on various factors but may not allow for an in-depth understanding of human behavior. Of course, surveys can be designed in several ways. They may include forced choice and semi-structured questions in which the researcher allows the respondent to describe or give details about specific events. One of the most challenging aspects of designing a good survey is wording questions unbiasedly and asking the right questions so that respondents can give a clear response rather than choosing “undecided” each time. Knowing that 30% of respondents are undecided is of little use! So, much time and effort should be spent constructing survey items. One of the benefits of having forced-choice items is that each response is coded so that the results can be quickly entered and analyzed using statistical software. Analysis takes much longer when respondents give lengthy responses that must be interpreted differently. Surveys help examine stated values, attitudes, and opinions and report on practices. However, they are based on self-report or what people say they do rather than on observation, which can limit accuracy.

Secondary/content analysis involves analyzing information that has already been collected or examining documents or media to uncover attitudes, practices, or preferences. Several data sets are available to those who wish to conduct this type of research. For example, the U.S. Census Data is known and widely used to look at trends and changes taking place in the United States (go to the US Census and check it out). Several other agencies collect data on family life, sexuality, and many other areas of interest in human development (for example, go to the KFF Foundation and see what you find on healthcare, insurance, statistics, and policy). The researcher conducting secondary analysis does not have to recruit subjects but does need to know the quality of the information collected in the original study.

Content analysis involves looking at media such as old texts, pictures, commercials, lyrics, or other materials to explore cultural patterns or themes. An example of content analysis is Aries’s classic history of childhood (1962) called “Centuries of Childhood,” or the analysis of television commercials for sexual or violent content. Passages in text or programs that air can also be randomly selected for analysis. Again, one advantage of analyzing such work is that the researcher does not have to go through the time and expense of finding respondents. Still, the researcher cannot know how accurately the media reflects the actions and sentiments of the population.

Developmental designs are techniques used in lifespan research (and other areas). These techniques examine how age, cohort, gender, and social class impact development. Cross-sectional research begins with a sample representing a cross-section of the population. Respondents who vary in age, gender, ethnicity, and social class might be asked to complete a survey about television program preferences or attitudes toward Internet use. The attitudes of males and females could then be compared to attitudes based on age. In cross-sectional research, respondents are measured only once. This method is much less expensive than longitudinal research but does not allow the researcher to distinguish between the impact of age and the cohort effect. Different attitudes about the Internet, for example, might not be altered by a person’s biological age as much as their life experiences as cohort members.

Longitudinal research involves beginning with a group of people who may be of the same age and background and measuring them repeatedly over a long period. One of the benefits of this type of research is that people can be followed through time and be compared with them when they were younger. A problem with this type of research is that it is costly, and subjects may drop out over time. (The film 49 Up is an example of following individuals over time. You see how people change physically, emotionally, and socially through time.) What would be the drawbacks of being in a longitudinal study? What about 49 Up? Would you want to be filmed every seven years? What would be the advantages and disadvantages? Can you imagine why some would continue and others would drop out of the project?

Cross-sequential research combines aspects of the previous two techniques, beginning with a cross-sectional sample and measuring them over time. This is the perfect model for looking at age, gender, social class, and ethnicity. However, the drawbacks of high costs and attrition are here as well.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action; A social-cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A, Ross, D. &. Ross S. (1963). Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 66:3-11.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth, and crisis. New York: Norton.

O’Grady, D. & Metz, J. (1987). Resilience in children at high risk for psychological disorder. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 12(1):3-23.

Piaget, J. (1929). The child’s conception of the world. NY: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich.

Attribution

From Developmental Psychology by Bill Pelz, CC-BY. Materials adapted from the course PSYC 200–Lifespan Psychology. Authored by : Laura Overstreet. Located at : http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/ . License : CC BY: Attribution.

Media Attributions

- isaac-quesada-dZYI4ga2eUA-unsplash © Isaac Quesada is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Sigmund_Freud,_by_Max_Halberstadt_(cropped) © Max Halberstadt is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pavlov is licensed under a Public Domain license

- B.F._Skinner_at_Harvard_circa_1950_(cropped) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Jean_Piaget_in_Ann_Arbor is licensed under a Public Domain license

Lifespan Development Copyright © 2024 by LOUIS: The Louisiana Library Network is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

2.4 Developing a Hypothesis

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis it is imporant to distinguish betwee a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition. He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observation before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [1] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Theory Testing

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). A researcher begins with a set of phenomena and either constructs a theory to explain or interpret them or chooses an existing theory to work with. He or she then makes a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researcher then conducts an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, he or she reevaluates the theory in light of the new results and revises it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researcher can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.2 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

Figure 2.2 Hypothetico-Deductive Method Combined With the General Model of Scientific Research in Psychology Together they form a model of theoretically motivated research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [2] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans (Zajonc & Sales, 1966) [3] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that really it does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

Key Takeaways

- A theory is broad in nature and explains larger bodies of data. A hypothesis is more specific and makes a prediction about the outcome of a particular study.

- Working with theories is not “icing on the cake.” It is a basic ingredient of psychological research.

- Like other scientists, psychologists use the hypothetico-deductive method. They construct theories to explain or interpret phenomena (or work with existing theories), derive hypotheses from their theories, test the hypotheses, and then reevaluate the theories in light of the new results.

- Practice: Find a recent empirical research report in a professional journal. Read the introduction and highlight in different colors descriptions of theories and hypotheses.

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Developmental Psychology

- Read this journal

- Read free articles

- Journal snapshot

- Advertising information

Journal scope statement

Developmental Psychology ® publishes articles that significantly advance knowledge and theory about development across the life span. The journal focuses on seminal empirical contributions. The journal occasionally publishes exceptionally strong scholarly reviews and theoretical or methodological articles. Studies of any aspect of psychological development are appropriate, as are studies of the biological, social, and cultural factors that affect development.

The journal welcomes not only laboratory-based experimental studies but studies employing other rigorous methodologies, such as ethnographies, field research, and secondary analyses of large data sets. We especially seek submissions in new areas of inquiry and submissions that will address contradictory findings or controversies in the field as well as the generalizability of extant findings in new populations.

Although most articles in this journal address human development, studies of other species are appropriate if they have important implications for human development.

Submissions can consist of single manuscripts, proposed sections, or short reports.

Disclaimer: APA and the editors of Developmental Psychology ® assume no responsibility for statements and opinions advanced by the authors of its articles.

Equity, diversity, and inclusion

Developmental Psychology supports equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in its practices. More information on these initiatives is available under EDI Efforts .

Open science

The APA Journals Program is committed to publishing transparent, rigorous research; improving reproducibility in science; and aiding research discovery. Open science practices vary per editor discretion. View the initiatives implemented by this journal .

Editor’s Choice

Each issue of Developmental Psychology will highlight one manuscript with the designation as an “ Editor’s Choice ” paper. Selection is based on the recommendations of the associate editors, based on the paper’s potential impact to the field, the distinction of expanding the contributors to, or the focus of, our science, or its discussion of an important future direction for science.

Call for papers

- Living in a digital ecology

Author and editor spotlights

Explore journal highlights : free article summaries, editor interviews and editorials, journal awards, mentorship opportunities, and more.

Prior to submission, please carefully read and follow the submission guidelines detailed below. Manuscripts that do not conform to the submission guidelines may be returned without review.

Submissions

Please submit manuscripts electronically through the Manuscript Submission Portal in Microsoft Word (.docx) or LaTex (.tex) as a zip file with an accompanied Portable Document Format (.pdf) of the manuscript file.

Prepare manuscripts according to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association using the 7 th edition. Manuscripts may be copyedited for bias-free language (see Chapter 5 of the Publication Manual ). APA Style and Grammar Guidelines for the 7 th edition are available.

Submit Manuscript

Koraly Pérez-Edgar The Pennsylvania State University

General correspondence may be directed to the editor's office .

Manuscripts should be the appropriate length for the material being presented. Manuscripts can vary from a maximum of 4,500 words for a brief report to 10,500 words for a larger research report to 15,000 words for a report containing multiple studies or comprehensive longitudinal studies. Please note that the total length includes the cover page, abstract, main manuscript text, references section, tables, and figures. Editors will decide on the appropriate length and may return a manuscript for revision before reviews if they think the paper is too long. Please make manuscripts as brief as possible. We have a strong preference for shorter papers.

Author contribution statements using CRediT

The APA Publication Manual (7th ed.) stipulates that “authorship encompasses…not only persons who do the writing but also those who have made substantial scientific contributions to a study.” In the spirit of transparency and openness, Developmental Psychology has adopted the Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT) to describe each author's individual contributions to the work. CRediT offers authors the opportunity to share an accurate and detailed description of their diverse contributions to a manuscript.

Submitting authors will be asked to identify the contributions of all authors at initial submission according to this taxonomy. If the manuscript is accepted for publication, the CRediT designations will be published as an author contributions statement in the author note of the final article. All authors should have reviewed and agreed to their individual contribution(s) before submission.

CRediT includes 14 contributor roles, as described below:

- Conceptualization: Ideas; formulation or evolution of overarching research goals and aims.

- Data curation: Management activities to annotate (produce metadata), scrub data, and maintain research data (including software code, where it is necessary for interpreting the data itself) for initial use and later reuse.

- Formal analysis: Application of statistical, mathematical, computational, or other formal techniques to analyze or synthesize study data.

- Funding acquisition: Acquisition of the financial support for the project leading to this publication.

- Investigation: Conducting a research and investigation process, specifically performing the experiments, or data/evidence collection.

- Methodology: Development or design of methodology; creation of models.

- Project administration: Management and coordination responsibility for the research activity planning and execution.

- Resources: Provision of study materials, reagents, materials, patients, laboratory samples, animals, instrumentation, computing resources, or other analysis tools.

- Software: Programming, software development; designing computer programs; implementation of the computer code and supporting algorithms; testing of existing code components.

- Supervision: Oversight and leadership responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, including mentorship external to the core team.

- Validation: Verification, whether as a part of the activity or separate, of the overall replication/reproducibility of results/experiments and other research outputs.

- Visualization: Preparation, creation, and/or presentation of the published work, specifically visualization/data presentation.

- Writing—original draft: Preparation, creation, and/or presentation of the published work, specifically writing the initial draft (including substantive translation).

- Writing—review and editing: Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work by those from the original research group, specifically critical review, commentary, or revision—including pre- or post-publication stages.

Authors can claim credit for more than one contributor role, and the same role can be attributed to more than one author.

Public significance statements

Authors submitting manuscripts to the journal Developmental Psychology are now required to provide 2–3 brief sentences regarding the relevance or public health significance of their study or review described in their manuscript. This description should be included within the manuscript on the abstract/keywords page.

The public significance statement (similar to the Relevance section of NIH grant submissions) summarizes the significance of the study's findings for a public audience in one to three sentences (approximately 30–70 words long). It should be written in language that is easily understood by both professionals and members of the lay public. Please refer to the Guidance for Translational Abstracts and Public Significance Statements page to help you write these statements. This statement supports efforts to increase dissemination and usage of research findings by larger and more diverse audiences.

When an accepted paper is published, these sentences will be boxed beneath the abstract for easy accessibility. All such descriptions will also be published as part of the table of contents, as well as on the journal's web page. This policy is in keeping with efforts to increase dissemination and usage by larger and diverse audiences.

Facilitating manuscript review

In addition to email addresses, please supply mailing addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers. Most correspondence will be handled by email. Keep a copy of the manuscript to guard against loss.

Masked review policy

This journal uses masked review for all submissions. Make every effort to see that the manuscript itself contains no clues to the authors' identity, including grant numbers, names of institutions providing IRB approval, self-citations, and links to online repositories for data, materials, code, or preregistrations (e.g., Create a View-only Link for a Project ). The submission letter should indicate the title of the manuscript, the authors' names and institutional affiliations, and the date the manuscript is submitted.

The first page of the manuscript should omit the authors' names and affiliations but should include the title of the manuscript and the date it is submitted. Author notes, acknowledgments, and footnotes containing information pertaining to the authors' identity or affiliations may be added on acceptance.

Methodology

Description of sample.

Authors should be sure to report the procedures for sample selection and recruitment. Major demographic characteristics should be reported, such as sex, age, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and, when possible and appropriate, disability status and sexual orientation. Even when such demographic characteristics are not analytic variables, they provide a more complete understanding of the sample and of the generalizability of the findings and are useful in future meta-analytic studies.

Authors should provide a justification that their sample size is appropriate beyond just citing convention in the literature. Justification could include a power analysis, a stopping rule, and/or some other type of valid justification.

Significance

For all study results, measures of both practical and statistical significance should be reported. The latter can involve either a standard error or an appropriate confidence interval. Practical significance can be reported using an effect size, a standardized regression coefficient, a factor loading, or an odds ratio.

Reliability

Manuscripts should include information regarding the establishment of interrater reliability when relevant, including the mechanisms used to establish reliability and the statistical verification of rater agreement and excluding the names of the trainers and the amount of personal contact with such individuals.

Journal Article Reporting Standards

Authors must adhere to the APA Style Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS) for quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. The standards offer ways to improve transparency in reporting to ensure that readers have the information necessary to evaluate the quality of the research and to facilitate collaboration and replication.

Transparency and openness

APA endorses the Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines developed by a community working group in conjunction with the Center for Open Science ( Nosek et al. 2015 ). Empirical research, including meta-analyses, submitted to Developmental Psychology must at least meet the “requirement” level for all aspects of research planning and reporting. Authors should include a subsection in the method section titled “Transparency and Openness.” This subsection should detail the efforts the authors have made to comply with the TOP Guidelines.

For example:

- We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures in the study, and we follow JARS (Appelbaum et al., 2018). All data, analysis code, and research materials are available at [stable link to repository]. Data were analyzed using R, version 4.0.0 (R Core Team, 2020) and the package ggplot , version 3.2.1 (Wickham, 2016). This study’s design and its analysis were not pre-registered.