Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NEWS EXPLAINER

- 08 June 2021

The COVID lab-leak hypothesis: what scientists do and don’t know

- Amy Maxmen &

- Smriti Mallapaty

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Debate over the idea that the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus emerged from a laboratory has escalated over the past few weeks, coinciding with the annual World Health Assembly, at which the World Health Organization (WHO) and officials from nearly 200 countries discussed the COVID-19 pandemic. After last year’s assembly, the WHO agreed to sponsor the first phase of an investigation into the pandemic’s origins, which took place in China in early 2021 .

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 594 , 313-315 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-01529-3

The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness & Response COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic (Independent Panel, 2021).

Huang, Y. in Learning from SARS: Preparing for the Next Disease Outbreak: Workshop Summary (eds Knobler, S. et al. ) (National Academies Press, 2004).

Google Scholar

Zhou P. et al. Nature 579 , 270–273 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lytras, S. et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.22.427830 (2021).

Xiao, X. et al. Sci. Rep. 11, 11898 (2021).

Andersen, K. G. et al. Nature Med. 26 , 450–452 (2020).

Wu, Y. & Zhao, S. Stem Cell Res. 50 , 102115 (2020).

Peacock, T. P. et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446163 (2021).

Zhou, P. et al. Nature 588 , E6 (2020).

Guo, H. et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.21.445091 (2021).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Public health

- Epidemiology

Could bird flu in cows lead to a human outbreak? Slow response worries scientists

News 17 MAY 24

Neglecting sex and gender in research is a public-health risk

Comment 15 MAY 24

Interpersonal therapy can be an effective tool against the devastating effects of loneliness

Correspondence 14 MAY 24

Bird flu in US cows: where will it end?

News 08 MAY 24

Monkeypox virus: dangerous strain gains ability to spread through sex, new data suggest

News 23 APR 24

Gut microbes linked to fatty diet drive tumour growth

News 16 MAY 24

Dual-action obesity drug rewires brain circuits for appetite

News & Views 15 MAY 24

Experimental obesity drug packs double punch to reduce weight

News 15 MAY 24

Faculty Positions& Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Optical and Electronic Information, HUST

Job Opportunities: Leading talents, young talents, overseas outstanding young scholars, postdoctoral researchers.

Wuhan, Hubei, China

School of Optical and Electronic Information, Huazhong University of Science and Technology

Postdoc in CRISPR Meta-Analytics and AI for Therapeutic Target Discovery and Priotisation (OT Grant)

APPLICATION CLOSING DATE: 14/06/2024 Human Technopole (HT) is a new interdisciplinary life science research institute created and supported by the...

Human Technopole

Research Associate - Metabolism

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoc Fellowships

Train with world-renowned cancer researchers at NIH? Consider joining the Center for Cancer Research (CCR) at the National Cancer Institute

Bethesda, Maryland

NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Faculty Recruitment, Westlake University School of Medicine

Faculty positions are open at four distinct ranks: Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, Full Professor, and Chair Professor.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

11 Questions to Ask About COVID-19 Research

Debates have raged on social media, around dinner tables, on TV, and in Congress about the science of COVID-19. Is it really worse than the flu? How necessary are lockdowns? Do masks work to prevent infection? What kinds of masks work best? Is the new vaccine safe?

You might see friends, relatives, and coworkers offer competing answers, often brandishing studies or citing individual doctors and scientists to support their positions. With so much disagreement—and with such high stakes—how can we use science to make the best decisions?

Here at Greater Good , we cover research into social and emotional well-being, and we try to help people apply findings to their personal and professional lives. We are well aware that our business is a tricky one.

Summarizing scientific studies and distilling the key insights that people can apply to their lives isn’t just difficult for the obvious reasons, like understanding and then explaining formal science terms or rigorous empirical and analytic methods to non-specialists. It’s also the case that context gets lost when we translate findings into stories, tips, and tools, especially when we push it all through the nuance-squashing machine of the Internet. Many people rarely read past the headlines, which intrinsically aim to be relatable and provoke interest in as many people as possible. Because our articles can never be as comprehensive as the original studies, they almost always omit some crucial caveats, such as limitations acknowledged by the researchers. To get those, you need access to the studies themselves.

And it’s very common for findings and scientists to seem to contradict each other. For example, there were many contradictory findings and recommendations about the use of masks, especially at the beginning of the pandemic—though as we’ll discuss, it’s important to understand that a scientific consensus did emerge.

Given the complexities and ambiguities of the scientific endeavor, is it possible for a non-scientist to strike a balance between wholesale dismissal and uncritical belief? Are there red flags to look for when you read about a study on a site like Greater Good or hear about one on a Fox News program? If you do read an original source study, how should you, as a non-scientist, gauge its credibility?

Here are 11 questions you might ask when you read about the latest scientific findings about the pandemic, based on our own work here at Greater Good.

1. Did the study appear in a peer-reviewed journal?

In peer review, submitted articles are sent to other experts for detailed critical input that often must be addressed in a revision prior to being accepted and published. This remains one of the best ways we have for ascertaining the rigor of the study and rationale for its conclusions. Many scientists describe peer review as a truly humbling crucible. If a study didn’t go through this process, for whatever reason, it should be taken with a much bigger grain of salt.

“When thinking about the coronavirus studies, it is important to note that things were happening so fast that in the beginning people were releasing non-peer reviewed, observational studies,” says Dr. Leif Hass, a family medicine doctor and hospitalist at Sutter Health’s Alta Bates Summit Medical Center in Oakland, California. “This is what we typically do as hypothesis-generating but given the crisis, we started acting on them.”

In a confusing, time-pressed, fluid situation like the one COVID-19 presented, people without medical training have often been forced to simply defer to expertise in making individual and collective decisions, turning to culturally vetted institutions like the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Is that wise? Read on.

2. Who conducted the study, and where did it appear?

“I try to listen to the opinion of people who are deep in the field being addressed and assess their response to the study at hand,” says Hass. “With the MRNA coronavirus vaccines, I heard Paul Offit from UPenn at a UCSF Grand Rounds talk about it. He literally wrote the book on vaccines. He reviewed what we know and gave the vaccine a big thumbs up. I was sold.”

From a scientific perspective, individual expertise and accomplishment matters—but so does institutional affiliation.

Why? Because institutions provide a framework for individual accountability as well as safety guidelines. At UC Berkeley, for example , research involving human subjects during COVID-19 must submit a Human Subjects Proposal Supplement Form , and follow a standard protocol and rigorous guidelines . Is this process perfect? No. It’s run by humans and humans are imperfect. However, the conclusions are far more reliable than opinions offered by someone’s favorite YouTuber .

Recommendations coming from institutions like the CDC should not be accepted uncritically. At the same time, however, all of us—including individuals sporting a “Ph.D.” or “M.D.” after their names—must be humble in the face of them. The CDC represents a formidable concentration of scientific talent and knowledge that dwarfs the perspective of any one individual. In a crisis like COVID-19, we need to defer to that expertise, at least conditionally.

“If we look at social media, things could look frightening,” says Hass. When hundreds of millions of people are vaccinated, millions of them will be afflicted anyway, in the course of life, by conditions like strokes, anaphylaxis, and Bell’s palsy. “We have to have faith that people collecting the data will let us know if we are seeing those things above the baseline rate.”

3. Who was studied, and where?

Animal experiments tell scientists a lot, but their applicability to our daily human lives will be limited. Similarly, if researchers only studied men, the conclusions might not be relevant to women, and vice versa.

Many psychology studies rely on WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic) participants, mainly college students, which creates an in-built bias in the discipline’s conclusions. Historically, biomedical studies also bias toward gathering measures from white male study participants, which again, limits generalizability of findings. Does that mean you should dismiss Western science? Of course not. It’s just the equivalent of a “Caution,” “Yield,” or “Roadwork Ahead” sign on the road to understanding.

This applies to the coronavirus vaccines now being distributed and administered around the world. The vaccines will have side effects; all medicines do. Those side effects will be worse for some people than others, depending on their genetic inheritance, medical status, age, upbringing, current living conditions, and other factors.

For Hass, it amounts to this question: Will those side effects be worse, on balance, than COVID-19, for most people?

“When I hear that four in 100,000 [of people in the vaccine trials] had Bell’s palsy, I know that it would have been a heck of a lot worse if 100,000 people had COVID. Three hundred people would have died and many others been stuck with chronic health problems.”

4. How big was the sample?

In general, the more participants in a study, the more valid its results. That said, a large sample is sometimes impossible or even undesirable for certain kinds of studies. During COVID-19, limited time has constrained the sample sizes.

However, that acknowledged, it’s still the case that some studies have been much larger than others—and the sample sizes of the vaccine trials can still provide us with enough information to make informed decisions. Doctors and nurses on the front lines of COVID-19—who are now the very first people being injected with the vaccine—think in terms of “biological plausibility,” as Hass says.

Did the admittedly rushed FDA approval of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine make sense, given what we already know? Tens of thousands of doctors who have been grappling with COVID-19 are voting with their arms, in effect volunteering to be a sample for their patients. If they didn’t think the vaccine was safe, you can bet they’d resist it. When the vaccine becomes available to ordinary people, we’ll know a lot more about its effects than we do today, thanks to health care providers paving the way.

5. Did the researchers control for key differences, and do those differences apply to you?

Diversity or gender balance aren’t necessarily virtues in experimental research, though ideally a study sample is as representative of the overall population as possible. However, many studies use intentionally homogenous groups, because this allows the researchers to limit the number of different factors that might affect the result.

While good researchers try to compare apples to apples, and control for as many differences as possible in their analyses, running a study always involves trade-offs between what can be accomplished as a function of study design, and how generalizable the findings can be.

The Science of Happiness

What does it take to live a happier life? Learn research-tested strategies that you can put into practice today. Hosted by award-winning psychologist Dacher Keltner. Co-produced by PRX and UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center.

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

You also need to ask if the specific population studied even applies to you. For example, when one study found that cloth masks didn’t work in “high-risk situations,” it was sometimes used as evidence against mask mandates.

However, a look beyond the headlines revealed that the study was of health care workers treating COVID-19 patients, which is a vastly more dangerous situation than, say, going to the grocery store. Doctors who must intubate patients can end up being splattered with saliva. In that circumstance, one cloth mask won’t cut it. They also need an N95, a face shield, two layers of gloves, and two layers of gown. For the rest of us in ordinary life, masks do greatly reduce community spread, if as many people as possible are wearing them.

6. Was there a control group?

One of the first things to look for in methodology is whether the population tested was randomly selected, whether there was a control group, and whether people were randomly assigned to either group without knowing which one they were in. This is especially important if a study aims to suggest that a certain experience or treatment might actually cause a specific outcome, rather than just reporting a correlation between two variables (see next point).

For example, were some people randomly assigned a specific meditation practice while others engaged in a comparable activity or exercise? If the sample is large enough, randomized trials can produce solid conclusions. But, sometimes, a study will not have a control group because it’s ethically impossible. We can’t, for example, let sick people go untreated just to see what would happen. Biomedical research often makes use of standard “treatment as usual” or placebos in control groups. They also follow careful ethical guidelines to protect patients from both maltreatment and being deprived necessary treatment. When you’re reading about studies of masks, social distancing, and treatments during the COVID-19, you can partially gauge the reliability and validity of the study by first checking if it had a control group. If it didn’t, the findings should be taken as preliminary.

7. Did the researchers establish causality, correlation, dependence, or some other kind of relationship?

We often hear “Correlation is not causation” shouted as a kind of battle cry, to try to discredit a study. But correlation—the degree to which two or more measurements seem connected—is important, and can be a step toward eventually finding causation—that is, establishing a change in one variable directly triggers a change in another. Until then, however, there is no way to ascertain the direction of a correlational relationship (does A change B, or does B change A), or to eliminate the possibility that a third, unmeasured factor is behind the pattern of both variables without further analysis.

In the end, the important thing is to accurately identify the relationship. This has been crucial in understanding steps to counter the spread of COVID-19 like shelter-in-place orders. Just showing that greater compliance with shelter-in-place mandates was associated with lower hospitalization rates is not as conclusive as showing that one community that enacted shelter-in-place mandates had lower hospitalization rates than a different community of similar size and population density that elected not to do so.

We are not the first people to face an infection without understanding the relationships between factors that would lead to more of it. During the bubonic plague, cities would order rodents killed to control infection. They were onto something: Fleas that lived on rodents were indeed responsible. But then human cases would skyrocket.

Why? Because the fleas would migrate off the rodent corpses onto humans, which would worsen infection. Rodent control only reduces bubonic plague if it’s done proactively; once the outbreak starts, killing rats can actually make it worse. Similarly, we can’t jump to conclusions during the COVID-19 pandemic when we see correlations.

8. Are journalists and politicians, or even scientists, overstating the result?

Language that suggests a fact is “proven” by one study or which promotes one solution for all people is most likely overstating the case. Sweeping generalizations of any kind often indicate a lack of humility that should be a red flag to readers. A study may very well “suggest” a certain conclusion but it rarely, if ever, “proves” it.

This is why we use a lot of cautious, hedging language in Greater Good , like “might” or “implies.” This applies to COVID-19 as well. In fact, this understanding could save your life.

When President Trump touted the advantages of hydroxychloroquine as a way to prevent and treat COVID-19, he was dramatically overstating the results of one observational study. Later studies with control groups showed that it did not work—and, in fact, it didn’t work as a preventative for President Trump and others in the White House who contracted COVID-19. Most survived that outbreak, but hydroxychloroquine was not one of the treatments that saved their lives. This example demonstrates how misleading and even harmful overstated results can be, in a global pandemic.

9. Is there any conflict of interest suggested by the funding or the researchers’ affiliations?

A 2015 study found that you could drink lots of sugary beverages without fear of getting fat, as long as you exercised. The funder? Coca Cola, which eagerly promoted the results. This doesn’t mean the results are wrong. But it does suggest you should seek a second opinion : Has anyone else studied the effects of sugary drinks on obesity? What did they find?

It’s possible to take this insight too far. Conspiracy theorists have suggested that “Big Pharma” invented COVID-19 for the purpose of selling vaccines. Thus, we should not trust their own trials showing that the vaccine is safe and effective.

But, in addition to the fact that there is no compelling investigative evidence that pharmaceutical companies created the virus, we need to bear in mind that their trials didn’t unfold in a vacuum. Clinical trials were rigorously monitored and independently reviewed by third-party entities like the World Health Organization and government organizations around the world, like the FDA in the United States.

Does that completely eliminate any risk? Absolutely not. It does mean, however, that conflicts of interest are being very closely monitored by many, many expert eyes. This greatly reduces the probability and potential corruptive influence of conflicts of interest.

10. Do the authors reference preceding findings and original sources?

The scientific method is based on iterative progress, and grounded in coordinating discoveries over time. Researchers study what others have done and use prior findings to guide their own study approaches; every study builds on generations of precedent, and every scientist expects their own discoveries to be usurped by more sophisticated future work. In the study you are reading, do the researchers adequately describe and acknowledge earlier findings, or other key contributions from other fields or disciplines that inform aspects of the research, or the way that they interpret their results?

Greater Good’s Guide to Well-Being During Coronavirus

Practices, resources, and articles for individuals, parents, and educators facing COVID-19

This was crucial for the debates that have raged around mask mandates and social distancing. We already knew quite a bit about the efficacy of both in preventing infections, informed by centuries of practical experience and research.

When COVID-19 hit American shores, researchers and doctors did not question the necessity of masks in clinical settings. Here’s what we didn’t know: What kinds of masks would work best for the general public, who should wear them, when should we wear them, were there enough masks to go around, and could we get enough people to adopt best mask practices to make a difference in the specific context of COVID-19 ?

Over time, after a period of confusion and contradictory evidence, those questions have been answered . The very few studies that have suggested masks don’t work in stopping COVID-19 have almost all failed to account for other work on preventing the disease, and had results that simply didn’t hold up. Some were even retracted .

So, when someone shares a coronavirus study with you, it’s important to check the date. The implications of studies published early in the pandemic might be more limited and less conclusive than those published later, because the later studies could lean on and learn from previously published work. Which leads us to the next question you should ask in hearing about coronavirus research…

11. Do researchers, journalists, and politicians acknowledge limitations and entertain alternative explanations?

Is the study focused on only one side of the story or one interpretation of the data? Has it failed to consider or refute alternative explanations? Do they demonstrate awareness of which questions are answered and which aren’t by their methods? Do the journalists and politicians communicating the study know and understand these limitations?

When the Annals of Internal Medicine published a Danish study last month on the efficacy of cloth masks, some suggested that it showed masks “make no difference” against COVID-19.

The study was a good one by the standards spelled out in this article. The researchers and the journal were both credible, the study was randomized and controlled, and the sample size (4,862 people) was fairly large. Even better, the scientists went out of their way to acknowledge the limits of their work: “Inconclusive results, missing data, variable adherence, patient-reported findings on home tests, no blinding, and no assessment of whether masks could decrease disease transmission from mask wearers to others.”

Unfortunately, their scientific integrity was not reflected in the ways the study was used by some journalists, politicians, and people on social media. The study did not show that masks were useless. What it did show—and what it was designed to find out—was how much protection masks offered to the wearer under the conditions at the time in Denmark. In fact, the amount of protection for the wearer was not large, but that’s not the whole picture: We don’t wear masks mainly to protect ourselves, but to protect others from infection. Public-health recommendations have stressed that everyone needs to wear a mask to slow the spread of infection.

“We get vaccinated for the greater good, not just to protect ourselves ”

As the authors write in the paper, we need to look to other research to understand the context for their narrow results. In an editorial accompanying the paper in Annals of Internal Medicine , the editors argue that the results, together with existing data in support of masks, “should motivate widespread mask wearing to protect our communities and thereby ourselves.”

Something similar can be said of the new vaccine. “We get vaccinated for the greater good, not just to protect ourselves,” says Hass. “Being vaccinated prevents other people from getting sick. We get vaccinated for the more vulnerable in our community in addition for ourselves.”

Ultimately, the approach we should take to all new studies is a curious but skeptical one. We should take it all seriously and we should take it all with a grain of salt. You can judge a study against your experience, but you need to remember that your experience creates bias. You should try to cultivate humility, doubt, and patience. You might not always succeed; when you fail, try to admit fault and forgive yourself.

Above all, we need to try to remember that science is a process, and that conclusions always raise more questions for us to answer. That doesn’t mean we never have answers; we do. As the pandemic rages and the scientific process unfolds, we as individuals need to make the best decisions we can, with the information we have.

This article was revised and updated from a piece published by Greater Good in 2015, “ 10 Questions to Ask About Scientific Studies .”

About the Authors

Jeremy Adam Smith

Uc berkeley.

Jeremy Adam Smith edits the GGSC’s online magazine, Greater Good . He is also the author or coeditor of five books, including The Daddy Shift , Are We Born Racist? , and (most recently) The Gratitude Project: How the Science of Thankfulness Can Rewire Our Brains for Resilience, Optimism, and the Greater Good . Before joining the GGSC, Jeremy was a John S. Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford University.

Emiliana R. Simon-Thomas

Emiliana R. Simon-Thomas, Ph.D. , is the science director of the Greater Good Science Center, where she directs the GGSC’s research fellowship program and serves as a co-instructor of its Science of Happiness and Science of Happiness at Work online courses.

You May Also Enjoy

Why Your Sacrifices Matter During the Pandemic

How to Form a Pandemic Pod

How Does COVID-19 Affect Trust in Government?

Why Is COVID-19 Killing So Many Black Americans?

How to Keep the Greater Good in Mind During the Coronavirus Outbreak

In a Pandemic, Elbow Touches Might Keep Us Going

A researcher’s view on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: The scientific process needs to be better explained

PhD Student in Microbiology-Immunology, Université Laval

Disclosure statement

Marc-Antoine De La Vega does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Université Laval provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA-FR.

Université Laval provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

View all partners

When I first wrote about the arrival of SARS-CoV-2 in early March 2020, the question was whether or not the new virus would become a pandemic. At the time, most experts believed that we had already reached the point of no return.

Today, 18 months later, the answer is clear. You don’t need to be a scientist to know it. This pandemic is the worst public health emergency of international concern that our modern society has faced. To date, more than 215 million cases have been confirmed and 4.5 million deaths have been reported globally .

These are just the reported cases. In reality, the number of cases is higher, and for a variety of reasons: lack of diagnostic capacity, infection without symptoms, unwillingness or inability to be tested or to visit a health facility, etc. The number of deaths due to COVID-19 is probably underestimated, both in Canada and worldwide .

In addition to changing the way we live our daily lives, the pandemic has brought scientific processes to public attention. Researchers, used to working in the shadows, now had to provide solutions — and explanations — to a very real threat, and they have been doing this under the watchful eye of the public.

One of these solutions, vaccination, is far from new. Yet no matter what the context, it has always generated news . So where are we now?

Still in our laboratories! I recently completed my PhD in microbiology-immunology at Laval University, research that I conducted under the supervision of Professor Gary Kobigner , who is known for co-developing an effective vaccine and treatment for Ebola. This fall, I will begin a postdoctoral fellowship at the Galveston National Laboratory in Texas, where I will continue my work on the transmission of, and vaccine development against, severe pathogens.

Relevant questions

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently lists 13 available COVID-19 vaccines, based on four different platforms, including mRNA vaccines and viral vector vaccines . Globally, more than five billion doses of vaccines have been administered. In Canada, five of these vaccines are currently approved for use: Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, AstraZeneca, COVISHIELD and Janssen , with Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna and AstraZeneca in wide distribution. Combined, these vaccines have been administered to approximately 70 per cent of Canadians.

However, many people have raised questions about these vaccines . And it is fair to do so! The unknown has always been a source of anxiety for human beings, it is normal to ask questions .

So, after working tirelessly to develop vaccines against COVID-19, what are scientists and doctors doing now?

They are doing what they have always done: Practising the best science they can within the limits of current knowledge. This scientific practice means continuing to evaluate the effectiveness of these vaccines against new variants in labs, as the virus continues to mutate.

It means continuing to record who has experienced side-effects (serious or not) from vaccination and continuing to investigate the potential links between these side-effects and the vaccine. The science they are practising involves studying the virus day and night to understand how it makes people sick, how we can prevent infection and what our options are for getting rid of it as quickly as possible.

The term “current knowledge” is very important here. It is possible that more side-effects related to vaccination will be discovered much later. Here’s why.

The scientific method

When vaccines are initially developed in the laboratory and tested on animals, it is normal that not all side-effects are identified. A mouse is not a human, after all, and models cannot account for all the variables that can be found in a human. Humans live in a complex environment and society where individuals each have their own genetics, immunity and lifestyle (exercise, smoking, nutrition).

Furthermore, the more people are vaccinated, the greater the likelihood of detecting a serious side-effect. Clinical trials, where drugs and vaccines are evaluated in a small group of individuals before being made available to the general population, are designed to be safe. Volunteers are usually healthy adults, without serious pre-existing medical conditions .

Read more: Explainer: How clinical trials test COVID-19 vaccines

Vaccination is now widespread in many countries. It is therefore statistically normal that rarer effects (for example, ones that one in a million people develop) are now being observed. These effects are too rare to have been detected in a clinical trial of 10,000 people. This is the case for rare side-effects such as Guillain-Barré syndrome and Bell’s palsy .

The scientific method requires that the following process is followed: Observe a problem, formulate a hypothesis about its possible causes, evaluate it experimentally by controlling the variables, interpret the results and draw a conclusion.

It can turn out that our initial hypothesis is wrong, and that is equally acceptable. This is how science was designed. I think that before the pandemic, people considered science infallible. Opening up research to the general public has greatly changed this perception, especially as science quickly became embroiled in politics, particularly over the question of the origin of the pandemic .

Knowing how to communicate

And that’s where the problem comes from, among other things. The key to effective scientific communication is not the science. It’s the communication . The results of laboratory experiments and clinical trials are what they are. Either the vaccine or drug works to reduce mortality, or it doesn’t work, and we go back to the drawing board.

So where does the reluctance about vaccines come from? One of the main problems is not the lack of information about the safety of the vaccine. Almost everyone has access to this information on internet. The problem is the lack of trust in institutions, which has been growing globally in recent years .

Read more: How better conversations can help reduce vaccine hesitancy for COVID-19 and other shots

But this trust can be earned — or regained. It just takes time, respect and empathy. A study by researchers at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke shows that an educational session about immunization that used motivational interviewing techniques with parents of infants resulted in a nine per cent increase in immunization rates compared with families who did not receive the sessions.

Finding the right answer to a question

Ultimately, the goal of science is to find the right answer to a question.

Of course, human nature being what it is, we are not immune to conflicts of interest. We need to ensure transparency about things like funding and links between scientists and potential investors. This is especially important since we are all responsible for funding research, whether through federal subsidies, which are partly derived from taxes paid by citizens, or through the ordinary purchase of drugs in pharmacies.

Since this concerns everyone, it is high time that the public became more involved. After all, scientific discoveries and health measures are everybody’s business. For example, few citizens are familiar with “ gain-of-function research .” These studies can involve a level of risk ranging from very low to very high. For example, producing a drug from a bacterium carries little risk and much benefit. However, increasing the virulence or transmissibility of a virus such as Ebola or Influenza could carry a lot of risk if such research were carried out by individuals with bad intentions, or in poorly secured laboratories.

Read more: Origins of SARS-CoV-2: Why the lab-leak idea is being considered again

As with any aspect of science, a risk-benefit analysis must be carried out. Note that in the vast majority of institutions where research is done, the committees assessing whether or not a study is worth doing are not only composed of scientists and students, but also members of the public.

Now each side just has to do its part. Scientists need to do a better job of communicating their results and the interpretation of them, as well as specifically answering questions of interest to the public and regaining their trust. They need to listen and stop hiding behind mountains of data, complicated words and scientific articles that are not easily accessible to the general public.

To those who are hesitant about vaccination, scientists should ask: “What data would make you change your mind?”, “Why do you think the current data are insufficient?”, “Why do you trust this individual, but not another or the institutions?” This is how constructive dialogue can be initiated and more in-depth reflection can begin.

For their part, citizens can adopt better practices when it comes to getting information and not only consider information that fits into their personal narrative. It is also important to avoid falling into a spiral of conspiracy theories and trust in false experts. It is important to not be afraid to doubt, to find other sources to confirm or refute what you have just read and to ask trusted experts around you what they think.

Do you have a question about COVID-19 vaccines? Email us at ca‑[email protected] and vaccine experts will answer questions in upcoming articles.

This article was originally published in French

- Science communication

- Scientific method

- Coronavirus

- AstraZeneca vaccine

- Vaccine hesitancy

- COVID-19 vaccines

- Moderna vaccine

- Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine

- Vaccine confidence

- Vaccine confidence in Canada

- Listen to this article

Compliance Lead

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

- Ideas for Action

- Join the MAHB

- Why Join the MAHB?

- Current Associates

- Current Nodes

- What is the MAHB?

- Who is the MAHB?

- Acknowledgments

Hypothesis: The COVID-19 Pandemic is Signaling Humanity’s Global Overshoot

| February 8, 2022 | Leave a Comment

Image by Alex Borland / publicdomainpictures

Item Link: Access the Resource

File: Download

Date of Publication: April

Year of Publication: 2021

Publication City: San Francisco, CA

Publisher: Academia Inc.

Author(s): Alexander K. Lautensach, Sabina W. Lautensach

Journal: Academia Letters

Volume: Article 538

In the Anthropocene, the year 2020 marks a milestone in humanity’s learning process about how we are affecting the biosphere and how it affects us in return (Ulrich 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic is the first global event that changed every human life, if not yet actually then certainly potentially. For the first time, humanity experiences species-wide a planetary phenomenon that allows neither escape nor denial and that demands a collective response from all cultures and societies. That raises the question how this phenomenon is to be interpreted.

HYPOTHESIS:

The COVID-19 pandemic is a feedback signal from the biosphere that denotes the ecological overshoot of the human species (currently estimated at about 1.7 planets; GFN 2020). That means that efforts to control this pandemic, even if successful, will not solve the wider problem of overshoot and the prospect of further, more threatening signals or ‘transition events’ (including partial collapse) for as long as overshoot persists.

Read the full paper here or download it from the link above.

- CORONAVIRUS COVERAGE

What you need to know about the COVID-19 lab-leak hypothesis

Newly reported information has revived scrutiny of this possible origin for the coronavirus, which experts still call unlikely though worth investigating.

Months after a World Health Organization investigation deemed it “extremely unlikely” that the novel coronavirus escaped accidentally from a laboratory in Wuhan, China, the idea is back in the news, giving new momentum to a hypothesis that many scientists believe is unlikely, and some have dismissed as a conspiracy theory .

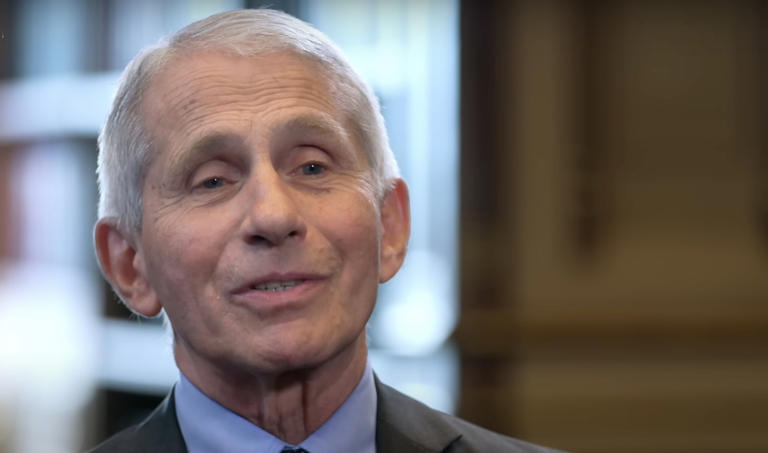

The renewed attention comes on the heels of President Joe Biden’s ordering U.S. intelligence agencies on May 26 to “ redouble their efforts ” to investigate the origins of the coronavirus. On May 11, Biden’s chief medical adviser, Anthony Fauci, acknowledged he’s now “ not convinced ” the virus developed naturally—an apparent pivot from what he told National Geographic in an interview last year.

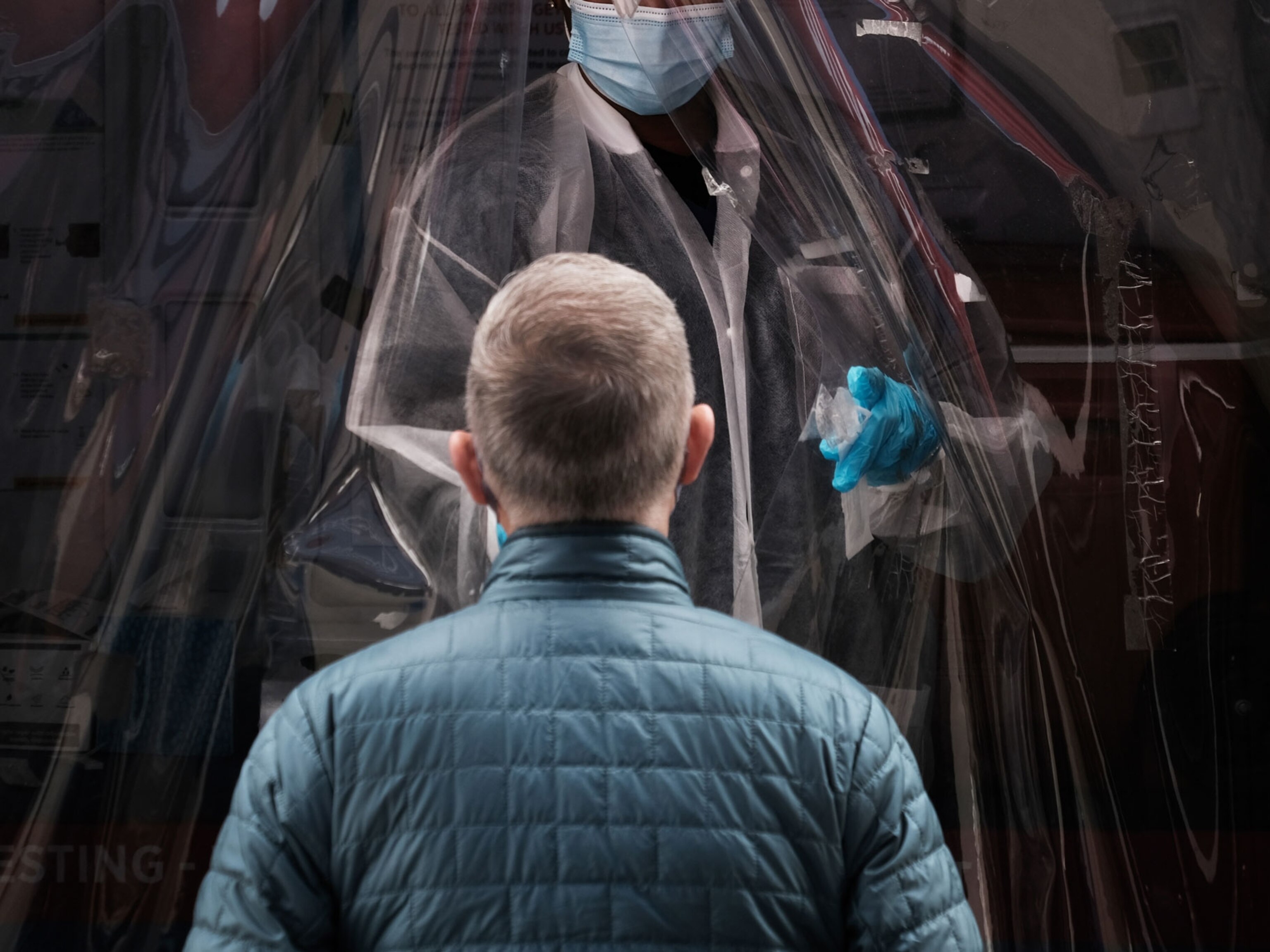

Also last month, more than a dozen scientists—top epidemiologists, immunologists, and biologists—wrote a letter published in the journal Science calling for a thorough investigation into two viable origin stories: natural spillover from animal to human, or an accident in which a wild laboratory sample containing SARS-CoV-2 was accidentally released. They urged that both hypotheses “be taken seriously until we have sufficient data,” writing that a proper investigation would be “transparent, objective, data-driven, inclusive of broad expertise, subject to independent oversight,” with conflicts of interest minimized, if possible.

“Anytime there is an infectious disease outbreak it is important to investigate its origin,” says Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security who did not contribute to the letter in Science . “The lab-leak hypothesis is possible—as is an animal spillover,” he says, “and I think that a thorough, independent investigation of its origins should be conducted.”

Unanswered questions

The origins of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 and has infected more than 171 million people, killing close to 3.7 million worldwide as of June 4, remain unclear. Many scientists, including those that participated in the WHO’s months-long investigation, believe the most likely explanation is that that it jumped from an animal to a person—potentially from a bat directly to a human, or through an intermediate host. Animal-to-human transmission is a common route for many viruses; at least two other coronaviruses, SARS and MERS , were spread through such zoonotic spillover.

Other scientists insist it’s worth investigating whether SARS-CoV-2 escaped from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, a laboratory that has studied coronaviruses in bats for more than a decade.

For Hungry Minds

The WHO investigation —a joint effort between WHO-appointed scientists and Chinese officials—concluded it was “extremely unlikely” the highly transmissible virus escaped from a laboratory. But the WHO team suffered roadblocks that led some to question its conclusions; the scientists were not permitted to conduct an independent investigation and were denied access to any raw data. ( We still don’t know the origins of the coronavirus. Here are 4 scenarios .)

On March 30, when the WHO released its report, its director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, called for further studies . “All hypotheses remain on the table,” he said at the time.

Then on May 11, Fauci told PolitiFact that while the virus most likely emerged via animal-to-human transmission, “it could have been something else, and we need to find that out.”

Recently disclosed evidence, first reported by the Wall Street Journal , has added fuel to the fire: Three researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology fell sick in November 2019 and sought hospital care, according to a U.S. intelligence report. In the final days of the Trump administration, the State Department released a statement that researchers at the institute had become ill with “symptoms consistent with both COVID-19 and common seasonal illness.”

You May Also Like

What is white lung syndrome? Here's what to know about pneumonia

COVID-19 is more widespread in animals than we thought

A deer may have passed COVID-19 to a person, study suggests

Most epidemiologists and virologists who have studied the novel coronavirus believe that it began spreading in November 2019. China says the first confirmed case was on December 8, 2019. During a briefing in Beijing this week, China’s foreign ministry spokesperson, Zhao Lijian, accused the U.S. of “ hyping up the theory of a lab leak ,” and asked, “does it really care about the study of origin tracing, or is it trying to divert attention?” Zhao also denied the Wall Street Journal report that three people had gotten sick.

Lab leak still ‘unlikely’

Some conservative politicians and commentators have embraced the lab-leak theory, while liberals more readily rejected it, especially early in the pandemic. The speculation has also heightened ongoing tensions between the U.S. and China.

On May 26, as the U.S. Senate passed a bill to declassify intelligence related to potential links between the Wuhan laboratory and COVID-19, Missouri Senator Josh Hawley, a Republican who sponsored the bill, said, “the world needs to know if this pandemic was the product of negligence at the Wuhan lab,” and lamented that “for over a year, anyone asking questions about the Wuhan Institute of Virology has been branded as a conspiracy theorist.”

Peter Navarro, Donald Trump’s former trade adviser, asserted in April 2020 that SARS-CoV-2 could have been engineered as a bioweapon, without citing any evidence.

The theory that SARS-CoV-2 was created as a bioweapon is “completely unlikely,” says William Schaffner, a professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. For one thing, he explains, for a bioweapon to be successful, it must target an adversarial population without affecting one’s own. In contrast, SARS-CoV-2 “cannot be controlled,” he says. “It will spread, including back on your own population,” making it an extremely “counterproductive biowarfare agent.”

The more plausible lab-leak hypothesis, scientists say, is that the Wuhan laboratory isolated the novel coronavirus from an animal and was studying it when it accidentally escaped. “Not knowing the extent of its virulence and transmissibility, a lack of protective measures [could have] resulted in laboratory workers becoming infected,” initiating the transmission chain that ultimately resulted in the pandemic, says Rossi Hassad, an epidemiologist at Mercy College.

But Hassad adds he believes that this lab-leak theory is on the “extreme low end” of possibilities, and it “will quite likely remain only theoretical following any proper scientific investigation,” he says.

Biden ordered U.S. intelligence agencies to report back with their findings in 90 days, which would be August 26.

Based on the available information, Eyal Oren, an epidemiologist at San Diego State University, says it’s apparent why the most accepted hypothesis is that this virus originated in an animal and jumped to a human: “What is clear is that the genetic sequence of the COVID-19 virus is similar to other coronaviruses found in bats,” he says.

Some scientists remain skeptical that concrete conclusions can be drawn. “At the end, I anticipate that the question” of SARS-CoV-2’s origins “will remain unresolved,” Schaffner says.

In the meantime, science “moves much more slowly than the media and news cycles,” Oren says.

Related Topics

- CORONAVIRUS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- WILDLIFE WATCHING

Seeking the Source of Ebola

5 things to know about COVID-19 tests in the age of Omicron

Here's what we know about the BA.2 Omicron subvariant driving a new COVID-19 wave

Humans are creating hot spots where bats could transmit zoonotic diseases

Hippos, hyenas, and other animals are contracting COVID-19

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Available Evidence and Ongoing Hypothesis on Corona Virus (COVID-19) and Psychosis: Is Corona Virus and Psychosis Related? A Narrative Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia.

- 2 Department of Psychiatry, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Mettu University, Mettu, Ethiopia.

- PMID: 32903810

- PMCID: PMC7445510

- DOI: 10.2147/PRBM.S264235

Background: Corona virus (COVID-19) is an outbreak of respiratory disease caused by a novel corona virus and declared to be a global health emergency and a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020. Prevention strategies to control the transmission of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as closing of schools, refraining from gathering, and social distancing, have direct impacts on mental well-being. SARS-CoV-2 has a devastating psychological impact on the mental health status of the community and, particularly when associated with psychotic symptoms, it could affect the overall quality-of-life. The virus also has the potential to enter and infect the brain. As a result, psychosis symptoms could be an emerging phenomenon associated with the corona virus pandemic. The presence of psychotic symptoms may complicate the management options of patients with COVID-19.

Objective: The aim of this article review is to elaborate the relationships between COVID-19 and psychotic symptoms.

Methodology: We independently searched different electronic databases, such as Google scholar, PubMed, Medline, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsychInfo, and other relevant sources published in English globally, by using the search terms "psychosis and COVID-19", "corona virus", "brief psychotic", "schizophrenia", "organic psychosis", "infectious disease", "mental illness", "pandemics", and "psychiatry" in various permutations and combinations.

Results: The results of the included studies revealed that patients with a novel corona virus had psychotic symptoms, including hallucination in different forms of modality, delusion, disorganized speech, and grossly disorganized or catatonic behaviors. The patients with COVID-19-related psychotic symptoms had responded with a short-term administration of the antipsychotic medication.

Conclusion and recommendation: A corona virus-related psychosis has been identified in different nations, but it is difficult to conclude that a novel corona virus has been biologically related to psychosis or exacerbates psychotic symptoms. Therefore, to identify the causal relationships between COVID-19 and psychosis, the researchers should investigate the prospective study on the direct biological impacts of COVID-19 and psychosis, and the clinicians should pay attention for psychotic symptoms at the treatment center and isolation rooms in order to reduce the complication of a novel corona virus.

Keywords: 2020; COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; psychosis.

© 2020 Tariku and Hajure.

Publication types

Grants and funding.

The Impact of COVID-19 on the Careers of Women in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2021)

Chapter: 8 major findings and research questions, 8 major findings and research questions, introduction.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which began in late 2019, created unprecedented global disruption and infused a significant level of uncertainty into the lives of individuals, both personally and professionally, around the world throughout 2020. The significant effect on vulnerable populations, such as essential workers and the elderly, is well documented, as is the devastating effect the COVID-19 pandemic had on the economy, particularly brick-and-mortar retail and hospitality and food services. Concurrently, the deaths of unarmed Black people at the hands of law enforcement officers created a heightened awareness of the persistence of structural injustices in U.S. society.

Against the backdrop of this public health crisis, economic upheaval, and amplified social consciousness, an ad hoc committee was appointed to review the potential effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on women in academic science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) during 2020. The committee’s work built on the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report Promising Practices for Addressing the Underrepresentation of Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine: Opening Doors (the Promising Practices report), which presents evidence-based recommendations to address the well-established structural barriers that impede the advancement of women in STEMM. However, the committee recognized that none of the actions identified in the Promising Practices report were conceived within the context of a pandemic, an economic downturn, or the emergence of national protests against structural racism. The representation and vitality of academic women in STEMM had already warranted national attention prior to these events, and the COVID-19

pandemic appeared to represent an additional risk to the fragile progress that women had made in some STEMM disciplines. Furthermore, the future will almost certainly hold additional, unforeseen disruptions, which underscores the importance of the committee’s work.

In times of stress, there is a risk that the divide will deepen between those who already have advantages and those who do not. In academia, senior and tenured academics are more likely to have an established reputation, a stable salary commitment, and power within the academic system. They are more likely, before the COVID-19 pandemic began, to have established professional networks, generated data that can be used to write papers, and achieved financial and job security. While those who have these advantages may benefit from a level of stability relative to others during stressful times, those who were previously systemically disadvantaged are more likely to experience additional strain and instability.

As this report has documented, during 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic had overall negative effects on women in academic STEMM in areas such productivity, boundary setting and boundary control, networking and community building, burnout rates, and mental well-being. The excessive expectations of caregiving that often fall on the shoulders of women cut across career timeline and rank (e.g., graduate student, postdoctoral scholar, non-tenure-track and other contingent faculty, tenure-track faculty), institution type, and scientific discipline. Although there have been opportunities for innovation and some potential shifts in expectations, increased caregiving demands associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, such as remote working, school closures, and childcare and eldercare, had disproportionately negative outcomes for women.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on women in STEMM during 2020 are understood better through an intentionally intersectional lens. Productivity, career, boundary setting, mental well-being, and health are all influenced by the ways in which social identities are defined and cultivated within social and power structures. Race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, academic career stage, appointment type, institution type, age, and disability status, among many other factors, can amplify or diminish the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic for a given person. For example, non-cisgender women may be forced to return to home environments where their gender identity is not accepted, increasing their stress and isolation, and decreasing their well-being. Women of Color had a higher likelihood of facing a COVID-19–related death in their family compared with their white, non-Hispanic colleagues. The full extent of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic for women of various social identities was not fully understood at the end of 2020.

Considering the relative paucity of women in many STEMM fields prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, women are more likely to experience academic isolation, including limited access to mentors, sponsors, and role models that share gender, racial, or ethnic identities. Combining this reality with the physical isolation stipulated by public health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic,

women in STEMM were subject to increasing isolation within their fields, networks, and communities. Explicit attention to the early indicators of how the COVID-19 pandemic affected women in academic STEMM careers during 2020, as well as attention to crisis responses throughout history, may provide opportunities to mitigate some of the long-term effects and potentially develop a more resilient and equitable academic STEMM system.

MAJOR FINDINGS

Given the ongoing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was not possible to fully understand the entirety of the short- or long-term implications of this global disruption on the careers of women in academic STEMM. Having gathered preliminary data and evidence available in 2020, the committee found that significant changes to women’s work-life boundaries and divisions of labor, careers, productivity, advancement, mentoring and networking relationships, and mental health and well-being have been observed. The following findings represent those aspects that the committee agreed have been substantiated by the preliminary data, evidence, and information gathered by the end of 2020. They are presented either as Established Research and Experiences from Previous Events or Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic during 2020 that parallel the topics as presented in the report.

Established Research and Experiences from Previous Events

___________________

1 This finding is primarily based on research on cisgender women and men.

Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic during 2020

Research questions.

While this report compiled much of the research, data, and evidence available in 2020 on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, future research is still needed to understand all the potential effects, especially any long-term implications. The research questions represent areas the committee identified for future research, rather than specific recommendations. They are presented in six categories that parallel the chapters of the report: Cross-Cutting Themes; Academic Productivity and Institutional Responses; Work-Life Boundaries and Gendered Divisions of Labor; Collaboration, Networking, and Professional Societies; Academic Leadership and Decision-Making; and Mental Health and Well-being. The committee hopes the report will be used as a basis for continued understanding of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in its entirety and as a reference for mitigating impacts of future disruptions that affect women in academic STEMM. The committee also hopes that these research questions may enable academic STEMM to emerge from the pandemic era a stronger, more equitable place for women. Therefore, the committee identifies two types of research questions in each category; listed first are those questions aimed at understanding the impacts of the disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by those questions exploring the opportunities to help support the full participation of women in the future.

Cross-Cutting Themes

- What are the short- and long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the career trajectories, job stability, and leadership roles of women, particularly of Black women and other Women of Color? How do these effects vary across institutional characteristics, 2 discipline, and career stage?

2 Institutional characteristics include different institutional types (e.g., research university, liberal arts college, community college), locales (e.g., urban, rural), missions (e.g., Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Hispanic-Serving Institutions, Asian American/Native American/Pacific Islander-Serving Institutions, Tribal Colleges and Universities), and levels of resources.

- How did the confluence of structural racism, economic hardships, and environmental disruptions affect Women of Color during the COVID-19 pandemic? Specifically, how did the murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black citizens impact Black women academics’ safety, ability to be productive, and mental health?

- How has the inclusion of women in leadership and other roles in the academy influenced the ability of institutions to respond to the confluence of major social crises during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- How can institutions build on the involvement women had across STEMM disciplines during the COVID-19 pandemic to increase the participation of women in STEMM and/or elevate and support women in their current STEMM-related positions?

- How can institutions adapt, leverage, and learn from approaches developed during 2020 to attend to challenges experienced by Women of Color in STEMM in the future?

Academic Productivity and Institutional Responses

- How did the institutional responses (e.g., policies, practices) that were outlined in the Major Findings impact women faculty across institutional characteristics and disciplines?

- What are the short- and long-term effects of faculty evaluation practices and extension policies implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic on the productivity and career trajectories of members of the academic STEMM workforce by gender?

- What adaptations did women use during the transition to online and hybrid teaching modes? How did these techniques and adaptations vary as a function of career stage and institutional characteristics?

- What are examples of institutional changes implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic that have the potential to reduce systemic barriers to participation and advancement that have historically been faced by academic women in STEMM, specifically Women of Color and other marginalized women in STEMM? How might positive institutional responses be leveraged to create a more resilient and responsive higher education ecosystem?

- How can or should funding arrangements be altered (e.g., changes in funding for research and/or mentorship programs) to support new ways of interaction for women in STEMM during times of disruption, such as the COVID-19 pandemic?

Work-Life Boundaries and Gendered Divisions of Labor

- How do different social identities (e.g., racial; socioeconomic status; culturally, ethnically, sexually, or gender diverse; immigration status; parents of young children and other caregivers; women without partners) influence the management of work-nonwork boundaries? How did this change during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- How have COVID-19 pandemic-related disruptions affected progress toward reducing the gender gap in academic STEMM labor-force participation? How does this differ for Women of Color or women with caregiving responsibilities?

- How can institutions account for the unique challenges of women faculty with parenthood and caregiving responsibilities when developing effective and equitable policies, practices, or programs?

- How might insights gained about work-life boundaries during the COVID-19 pandemic inform how institutions develop and implement supportive resources (e.g., reductions in workload, on-site childcare, flexible working options)?

Collaboration, Networking, and Professional Societies

- What were the short- and long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic-prompted switch from in-person conferences to virtual conferences on conference culture and climate, especially for women in STEMM?

- How will the increase in virtual conferences specifically affect women’s advancement and career trajectories? How will it affect women’s collaborations?

- How has the shift away from attending conferences and in-person networking changed longer-term mentoring and sponsoring relationships, particularly in terms of gender dynamics?

- How can institutions maximize the benefits of digitization and the increased use of technology observed during the COVID-19 pandemic to continue supporting women, especially marginalized women, by increasing accessibility, collaborations, mentorship, and learning?

- How can organizations that support, host, or facilitate online and virtual conferences and networking events (1) ensure open and fair access to participants who face different funding and time constraints; (2) foster virtual connections among peers, mentors, and sponsors; and (3) maintain an inclusive environment to scientists of all backgrounds?

- What policies, practices, or programs can be developed to help women in STEMM maintain a sense of support, structure, and stability during and after periods of disruption?

Academic Leadership and Decision-Making

- What specific interventions did colleges and universities initiate or prioritize to ensure that women were included in decision-making processes during responses to the COVID-19 pandemic?

- How effective were colleges and universities that prioritized equity-minded leadership, shared leadership, and crisis leadership styles at mitigating emerging and potential negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on women in their communities?

- What specific aspects of different leadership models translated to more effective strategies to advance women in STEMM, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- How can examples of intentional inclusion of women in decision-making processes during the COVID-19 pandemic be leveraged to develop the engagement of women as leaders at all levels of academic institutions?

- What are potential “top-down” structural changes in academia that can be implemented to mitigate the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic or other disruptions?

- How can academic leadership, at all levels, more effectively support the mental health needs of women in STEMM?

Mental Health and Well-being

- What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and institutional responses on the mental health and well-being of members of the academic STEMM workforce as a function of gender, race, and career stage?

- How are tools and diagnostic tests to measure aspects of wellbeing, including burnout and insomnia, used in academic settings? How does this change during times of increased stress, such as the COVID-19 pandemic?

- How might insights gained about mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic be used to inform preparedness for future disruptions?

- How can programs that focus on changes in biomarkers of stress and mood dysregulation, such as levels of sleep, activity, and texting patterns, be developed and implemented to better engage women in addressing their mental health?

- What are effective interventions to address the health of women academics in STEMM that specifically account for the effects of stress on women? What are effective interventions to mitigate the excessive levels of stress for Women of Color?

This page intentionally left blank.

The spring of 2020 marked a change in how almost everyone conducted their personal and professional lives, both within science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) and beyond. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted global scientific conferences and individual laboratories and required people to find space in their homes from which to work. It blurred the boundaries between work and non-work, infusing ambiguity into everyday activities. While adaptations that allowed people to connect became more common, the evidence available at the end of 2020 suggests that the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic endangered the engagement, experience, and retention of women in academic STEMM, and may roll back some of the achievement gains made by women in the academy to date.

The Impact of COVID-19 on the Careers of Women in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine identifies, names, and documents how the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the careers of women in academic STEMM during the initial 9-month period since March 2020 and considers how these disruptions - both positive and negative - might shape future progress for women. This publication builds on the 2020 report Promising Practices for Addressing the Underrepresentation of Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine to develop a comprehensive understanding of the nuanced ways these disruptions have manifested. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Careers of Women in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will inform the academic community as it emerges from the pandemic to mitigate any long-term negative consequences for the continued advancement of women in the academic STEMM workforce and build on the adaptations and opportunities that have emerged.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Methodologies for COVID-19 research and data analysis

This collection has closed and is no longer accepting new submissions.

This BMC Medical Research Methodology collection of articles has not been sponsored and articles undergo the journal’s standard peer-review process overseen by our Guest Editors, Prof. Dr. Livia Puljak (Catholic University of Croatia in Zagreb, Croatia) and Prof. Dr. Martin Wolkewitz (University of Freiburg, Germany).

Delays in reporting and publishing trial results during pandemics: cross sectional analysis of 2009 H1N1, 2014 Ebola, and 2016 Zika clinical trials

Pandemic events often trigger a surge of clinical trial activity aimed at rapidly evaluating therapeutic or preventative interventions. Ensuring rapid public access to the complete and unbiased trial record is...

- View Full Text

Open science saves lives: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic

In the last decade Open Science principles have been successfully advocated for and are being slowly adopted in different research communities. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic many publishers and research...

Clinical research activities during COVID-19: the point of view of a promoter of academic clinical trials

During the COVID-19 emergency, IRST IRCCS, an Italian cancer research institute and promoter of no profit clinical studies, adapted its activities and procedures as per European and national guidelines to main...

Instruments to measure fear of COVID-19: a diagnostic systematic review

The COVID-19 pandemic has become a source of fear across the world. Measuring the level or significance of fear in different populations may help identify populations and areas in need of public health and edu...

A risk assessment tool for resumption of research activities during the COVID-19 pandemic for field trials in low resource settings

The spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 has suspended many non-COVID-19 related research activities. Where restarting research activities is permitted, investigators need to evaluate the ...

Outbreaks of publications about emerging infectious diseases: the case of SARS-CoV-2 and Zika virus

Outbreaks of infectious diseases generate outbreaks of scientific evidence. In 2016 epidemics of Zika virus emerged, and in 2020, a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) caused a p...

Analysis of clinical and methodological characteristics of early COVID-19 treatment clinical trials: so much work, so many lost opportunities

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to rage on, and clinical research has been promoted worldwide. We aimed to assess the clinical and methodological characteristics of treatment clinical trials that have been set...

The unintended consequences of COVID-19 mitigation measures matter: practical guidance for investigating them

COVID-19 has led to the adoption of unprecedented mitigation measures which could trigger many unintended consequences. These unintended consequences can be far-reaching and just as important as the intended o...

Short-term real-time prediction of total number of reported COVID-19 cases and deaths in South Africa: a data driven approach

The rising burden of the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic in South Africa has motivated the application of modeling strategies to predict the COVID-19 cases and deaths. Reliable and accurate short and long-term forec...

Incorporating and addressing testing bias within estimates of epidemic dynamics for SARS-CoV-2

The disease burden of SARS-CoV-2 as measured by tests from various localities, and at different time points present varying estimates of infection and fatality rates. Models based on these acquired data may su...

COVID-19-related medical research: a meta-research and critical appraisal

Since the start of the COVID-19 outbreak, a large number of COVID-19-related papers have been published. However, concerns about the risk of expedited science have been raised. We aimed at reviewing and catego...

Use of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest registries to assess COVID-19 home mortality

In most countries, the official statistics for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) take account of in-hospital deaths but not those that occur at home. The study’s objective was to introduce a methodology ...

Strengthening policy coding methodologies to improve COVID-19 disease modeling and policy responses: a proposed coding framework and recommendations

In recent months, multiple efforts have sought to characterize COVID-19 social distancing policy responses. These efforts have used various coding frameworks, but many have relied on coding methodologies that ...

Predictive accuracy of a hierarchical logistic model of cumulative SARS-CoV-2 case growth until May 2020

Infectious disease predictions models, including virtually all epidemiological models describing the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, are rarely evaluated empirically. The aim of the present study was to inv...

Alternative graphical displays for the monitoring of epidemic outbreaks, with application to COVID-19 mortality

Classic epidemic curves – counts of daily events or cumulative events over time –emphasise temporal changes in the growth or size of epidemic outbreaks. Like any graph, these curves have limitations: they are ...

The Correction to this article has been published in BMC Medical Research Methodology 2020 20 :265

COVID19-world: a shiny application to perform comprehensive country-specific data visualization for SARS-CoV-2 epidemic

Data analysis and visualization is an essential tool for exploring and communicating findings in medical research, especially in epidemiological surveillance.

Social network analysis methods for exploring SARS-CoV-2 contact tracing data

Contact tracing data of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic is used to estimate basic epidemiological parameters. Contact tracing data could also be potentially used for assessin...

Establishment of a pediatric COVID-19 biorepository: unique considerations and opportunities for studying the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children

COVID-19, the disease caused by the highly infectious and transmissible coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, has quickly become a morbid global pandemic. Although the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children is less clin...

Statistical design of Phase II/III clinical trials for testing therapeutic interventions in COVID-19 patients

Because of unknown features of the COVID-19 and the complexity of the population affected, standard clinical trial designs on treatments may not be optimal in such patients. We propose two independent clinical...

Rapid establishment of a COVID-19 perinatal biorepository: early lessons from the first 100 women enrolled

Collection of biospecimens is a critical first step to understanding the impact of COVID-19 on pregnant women and newborns - vulnerable populations that are challenging to enroll and at risk of exclusion from ...

Disease progression of cancer patients during COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive analytical strategy by time-dependent modelling

As the whole world is experiencing the cascading effect of a new pandemic, almost every aspect of modern life has been disrupted. Because of health emergencies during this period, widespread fear has resulted ...

A four-step strategy for handling missing outcome data in randomised trials affected by a pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic (Covid-19) presents a variety of challenges for ongoing clinical trials, including an inevitably higher rate of missing outcome data, with new and non-standard reasons for missingness....

Joint analysis of duration of ventilation, length of intensive care, and mortality of COVID-19 patients: a multistate approach