Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Re-assessing causality between energy consumption and economic growth

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Newcastle University, Newcastle, United Kingdom

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Universidad Isabel I. Calle de Fernán González, Burgos, Spain

Affiliation IEI and Universitat Jaume I, Campus del Riu Sec, Castellón, Spain

- Atanu Ghoshray,

- Yurena Mendoza,

- Mercedes Monfort,

- Javier Ordoñez

- Published: November 12, 2018

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205671

- Reader Comments

The energy consumption-growth nexus has been widely studied in the empirical literature, though results have been inconclusive regarding the direction, or even the existence, of causality. These inconsistent results can be explained by two important limitations of the literature. First, the use of bivariate models, which fail to detect more complex causal relations, or the ad hoc approach to selecting variables in a multivariate framework; and, second, the use of linear causal models, which are unable to capture more complex nonlinear causal relationships. In this paper, we aim to overcome both limitations by analysing the energy consumption-growth nexus using a Flexible Fourier form due to Enders and Jones (2016). The analysis focuses on the US over the period 1949 to 2014. From our results we can conclude that, where the linear methodology supports the neutrality hypothesis (no causality between energy consumption and growth), the Flexible Fourier form points to the existence of causality from energy consumption to growth. This is contrary to the linear analysis, suggesting that lowering energy consumption would adversely affect US economic growth. Thus, by employing the Flexible Fourier form we find the conclusions can be quite different.

Citation: Ghoshray A, Mendoza Y, Monfort M, Ordoñez J (2018) Re-assessing causality between energy consumption and economic growth. PLoS ONE 13(11): e0205671. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205671

Editor: María Carmen Díaz Roldán, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, SPAIN

Received: April 8, 2018; Accepted: September 29, 2018; Published: November 12, 2018

Copyright: © 2018 Ghoshray et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are available at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.4h92834 .

Funding: JO acknowledges financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through grant ECO2014-58991-C3-2-R and AEI/FEDER ECO2017-83255-C3-3-P. JO acknowledges financial support from PROMETEO project PROMETEO II/2014/053. AG and JO thank the Generalitat Valenciana project AICO/2016/038. JO and MM are grateful for support from the University Jaume I research project P1.1B2014-7 and UJI-B2017-33. YM is grateful for support from the University Isabel I research project. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

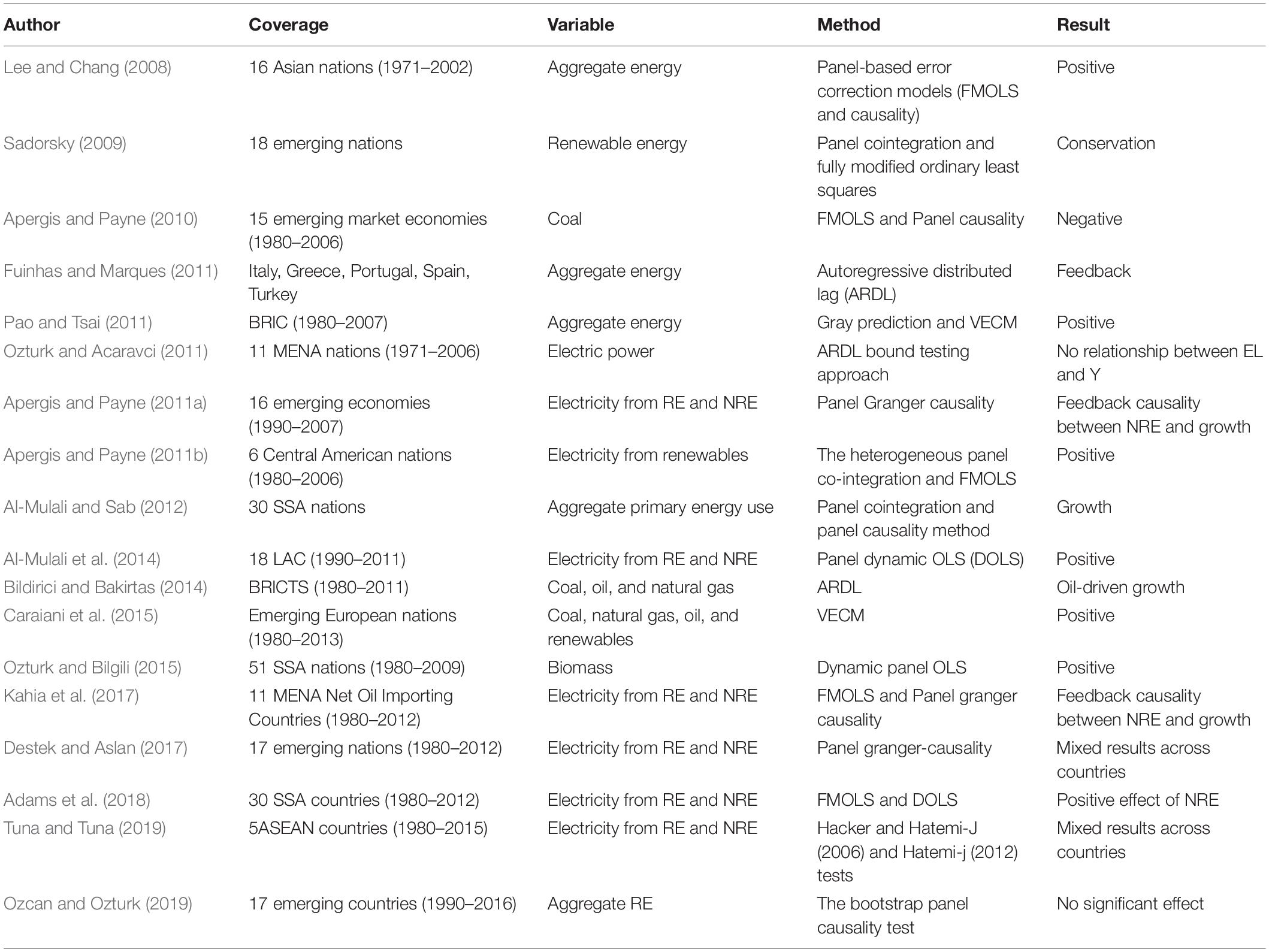

It has been argued that economic growth may exhaust resources and cause environmental degradation [ 1 ], compromising future growth. The fear that today's growth can cause other significant economic problems, especially for future generations, has propelled sustainable growth to the top of the political agenda for the vast majority of developed countries. Sustainability will depend on how the substitutability or complementarity between energy and production factors and the interplay with technical progress and productivity, impact economic growth. Consequently, and with the ultimate aim of assessing whether sustainable growth can be achieved, the causal relationship between economic growth and energy consumption has been widely debated in empirical studies. The energy-growth nexus has important policy implications. If increased energy consumption causes economic growth, sustainability can only be achieved by ensuring access to a cheap, safe, environmentally-friendly energy supply. Alternatively, if economic growth causes increased energy demand, the challenge is to reduce energy demand through market-oriented policies and regulatory instruments. A review of previous studies on growth-energy consumption using vector autoregressive (hereafter VAR) methodology is presented in Table 1 . Till date, from Table 1 , the results are inconsistent on the direction of causality between energy consumption and economic growth and even about the existence of causality [ 2 – 4 ]. Several factors lie behind these conflicting results. First, the data used in previous studies include different countries and time periods. Secondly, there are also differences in the variable selection; for example, most studies use aggregate energy consumption data, whereas a number of others examine various disaggregated measures. Thirdly, the studies also differ in terms of the econometric methodology.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205671.t001

The majority of the early studies confine the analysis to the bivariate causal relationship between energy consumption and real output. A common problem with the bivariate model specification is the possibility of omitted variable bias [ 17 , 18 ], with the consequent loss of information that may be relevant in determining the direction of causality. Over recent years, several authors have attempted to overcome this problem by including additional variables in the causal analysis of the relationship between energy consumption and growth. However, as pointed out by [ 19 ], these additional variables have been selected on a rather ad hoc basis and the results on causality may be influenced by variable selection bias. Related to this problem of selection bias and variable omission, [ 20 ] point out that the absence of a prior theoretical model may cause the causality test to deliver mixed results. To address the lack of statistical motivation when choosing the control variables for the causal analysis, [ 19 ] apply a robust Bayesian probabilistic model to select the explanatory variables to be considered in the causal analysis of the relationship between energy consumption and economic growth. This approach allows for the evaluation of the posterior probability of including in the model a control variable selected from a large group of possible candidates; to the best of our knowledge, it is the first time in the literature that a robust variable selection method has been applied for this purpose. [ 19 ] use this method to select control variables for the analysis of the relationship between energy consumption and growth in the US from 1949 and 2010, for both aggregated and disaggregated data.

Most empirical studies test for causality in a linear framework (for example using Granger-Sims causality tests and/or unit root and cointegration techniques with either time series or panel data), neglecting the possibility of nonlinear causality. However, given the growing evidence of the presence of possible nonlinearity in several macroeconomic time series which could be caused as a result of several structural breaks, there has been an increasing reliance on nonlinear techniques that could capture causal relations between such variables. Some authors argue that the linear approach to causality testing is limited in its capacity to detect certain kinds of nonlinear causal relationships and so recommend the use of nonlinear techniques [ 21 – 23 ].

While the linear VAR model has advantages in incorporating a large number of variables to be analyzed for Granger causality, there remain limitations, particularly relating to the underlying characteristics of the variables chosen in the model. The variables chosen in the present study are subject to structural breaks as documented by various studies. For example, [ 24 ] conclude structural breaks in oil prices, [ 25 ] find evidence of structural breaks in energy consumption and [ 26 ] conclude the presence of breaks in economic growth. Taking account of the recent studies in the area of energy consumption-economic growth nexus, the VAR modelling approach remains popular. However, as shown by [ 27 ] it is not straightforward to control for breaks in a VAR since a break in one variable will manifest itself in other variables of the VAR model, leading to model misspecification [ 28 ]. Accordingly, we propose to adopt a Flexible Fourier Form VAR (FFF-VAR) framework that allows for smooth breaks that increase the power and size properties of the model.

Therefore, our contribution to the extant literature is to add new findings to the energy consumption-economic growth literature using an alternative modelling approach. We test for causality between energy consumption and economic growth in the US in a multivariate framework, including variables such as those with the highest posterior probability of inclusion according to the results reported by [ 19 ], and at the same time, recognise the presence of the variables included in the VAR model to contain structural breaks and thereby choose an appropriate specification, the FFF-VAR to test for causality between the variables. This approach would be more conducive for the type of variables employed given the possibility of several gradual breaks which can be approximated by smooth breaks couched in the FFF-VAR model.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: in the next section, we discuss why it is important to consider nonlinearities when analysing the energy-growth nexus; we explain the econometric methodology in section 3 and present the results of our analysis in section 4. Finally, we outline our conclusions in section 5.

Nonlinearities and the energy-growth nexus

In addition to the selection of relevant variables prior to the study of causality, as stated above, another potential cause of ambiguity in the empirical results on causality is the selection of the functional form of the test. The importance of not neglecting the nonlinearity in energy studies has been widely discussed in the literature. Table 2 summarizes the reasons suggested in the energy literature that motivates the use of a nonlinear framework. Specifically, [ 29 ] conclude that “Due to the influences of economic cycle fluctuations, macroeconomic policies, international oil price fluctuations, technological progress, and industrial adjustment, there may be a nonlinear relationship among economic growth, energy consumption, and CO2 emission” (pp. 1153).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205671.t002

Despite the importance of nonlinearities in energy economics, the visibility of nonlinear econometric methodologies is surprisingly almost non-existent. For example, in a survey of more than fifty studies in the energy literature by [ 35 ] only one paper due to [ 34 ], consider a nonlinear functional form. Similarly, a survey by [ 36 ] cites a single paper by [ 31 ], that uses a nonlinear methodology in the energy-environment-growth nexus analysis. From the extant literature discussed above, both the empirical and the theoretical studies suggest several reasons to expect nonlinear behavior in the relationship between growth and energy consumption. The main arguments are:

a) Energy prices cause different consumption levels

Historical events suggest that a significant and persistent increase in energy prices over time is usually followed by a downward adjustment of economic growth [ 37 ]. However, this adjustment is not instantaneous; there is a delay between the rise in prices and the fall in the level of production. After a time lag, this economic contraction causes a lower level of consumption, which is likely to be maintained until there is a significant change in energy prices, especially the case of oil.

It is important to note that the nonlinear pattern of energy prices could be reflected in the energy consumption-growth ratio, since energy prices may be the cause of certain contractions and expansions in growth, consequently resulting in different levels of energy consumption. The structural breaks in energy prices renders the linear framework unsuitable for capturing the dynamics of this relationship.

b) Pollution haven hypothesis and porter hypothesis

More stringent environmental regulations increase competitive pressure, especially for those firms operating in the most polluting activities. Companies have a number of ways in which to adapt to regulations: first, they can buy emissions rights in order to continue consuming similar levels of energy; second, they can limit their consumption by producing less; a third alternative (called the Porter Hypothesis) is to invest in clean, efficient technologies that enable them to adapt to regulations while simultaneously boosting their competitiveness; or, fourth, they can move to countries with lax environmental regulations. This last strategy is known as the Pollution Haven Hypothesis (PHH), which states that companies in countries forced to comply with strict environmental regulations may eventually relocate to countries with weaker environmental laws.

According to the PHH, emissions in countries subject to regulatory pressure may decrease as a consequence of tightening environmental regulations. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that companies would all of a sudden "migrate" in response to the new regulatory framework. Instead, one would expect to find a gradual change in the deterministic structure of the relationship. On the other hand, the Porter Hypothesis holds that firms will introduce changes in production in order to comply with strict environmental policies and in an attempt to be more efficient and innovative. These changes will in turn affect energy consumption. Structural changes such as these are the result of progressive investment in cleaner, more efficient technologies. Therefore, models that allow for small but several breaks that can be approximated by smooth changes seem more suitable than linear models when it comes to capturing the effects envisaged by the Porter Hypothesis.

c) Changes in sectoral specialization

Changes in the deterministic structure of the energy consumption-growth relationship can also be explained by the changes in the relative contribution different sectors make to GDP as a country experiences economic growth. There is a shift in the early stages of industrialization whereby sectors such as agriculture become less important than manufacturing; while in more advanced stages of development, manufacturing and other consumer goods sectors are replaced by the lower-consumption services sector. This undoubtedly creates a structural change in energy consumption that linear tests may be unable to capture.

d) The environment as a luxury good

The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) describes the change in a country’s emission levels over time as a result of its economic growth. In the early stages of industrialization, energy consumption rises sharply in countries that do not prioritize environmental degradation control. When countries reach a critical income level, their priorities switch to environmental protection, leading to changes in the energy regime.

To sum up, there are several possible reasons for the existence of nonlinearities in the energy consumption-economic growth relationship. Nevertheless, most studies analyze the energy consumption-economic growth relationship using a linear framework, which for reasons discussed earlier, are restrictive. Given the limitations, the most appropriate models for capturing a possible causality relationship between energy consumption and growth would be those that can approximate the small but several structural breaks that are likely to plague the variables chosen in this study. For the sake of comparison, we estimate both linear and non-linear models.

Methodology

It is not unusual to find economic variables that contain multiple structural breaks. A vast plethora of studies have been put forward that test for structural breaks in individual time series variables. However, when the variables are couched in to a VAR model, this leads to a serious problem. For example, if there are structural breaks in just one variable in the VAR model, that can induce structural shifts in the other variables included in the model [ 28 ]. The problem is exacerbated in the VAR model as the breaks in the single variable affect other variables with a lag. [ 28 ] address this problem by building on the FFF-VAR model allowing for the Flexible Fourier Form to deal with possible multiple smooth shifts in the data.

This deterministic form is particularly useful in capturing the nature of the time series process that contains several small structural breaks with the help of low frequency components. In a way, the choice of the appropriate frequencies to include into the Flexible Fourier form controls for the structural breaks in the data. A test for nonlinearity can be conducted by performing a simple F-test for the exclusion restriction that all values of ϕ ik = ψ ik = 0 in (2). This is possible as [ 39 ] show that the ϕ ik and ψ ik in (2) have multivariate normal distributions. An advantage of the Flexible Fourier form is that it can mimic the nature of the breaks without any knowledge of the magnitude, location and the number of break dates. Besides, the Fourier approximation works for structural breaks which can be of either the innovational outlier or the additive outlier type.

The null hypothesis of a unit root is given by H 0 :( θ = 0) and is tested using a Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test statistic given by τ LM . If the null hypothesis is rejected we can conclude that the data series is stationary. In the case of serially correlated errors, lagged values of Δ y t are added to the regression so that the residuals are white noise. Given the limitation of the number of observations that we have, we choose to set n = k = 1. As emphasised by [ 40 ], a fourier form using k = 1 can serve as a reasonable approximation to breaks of unknown form.

The FFF-VAR model has good size and power properties when testing for smooth structural changes in a VAR(1). In particular, with multiple structural breaks not particularly accounted for, the Granger causality tests tend to have poor size properties. The application of the FFF-VAR model to data that may contain multiple structural breaks, obviates these problems leading towards more reliable results.

Data, results and discussion

In this section, we investigate the dynamic relationship between energy consumption and growth in the US. Making use of a Flexible Fourier form due to [ 28 ], we use causality analysis. As mentioned earlier, [ 19 ] develop a Bayesian model to select the variables with the highest posterior probability of explaining US growth; they consequently choose energy consumption (EC), public spending (SPE) and the oil price (OP) as covariates. Growth has been extracted from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis ( http://www.bea.gov/ ) and is measured in million dollars as the ratio between Value Added (VA) and the the Value Added Price Index. Energy Consumption (EC), is measured in billion BTU, and has been obtained from US Energy Information Administration ( http://www.eia.gov/ ). Oil Price (OP) corresponds to real oil prices in dollars per barrel, and has been obtained from InflationData.com ( http://inflationdata.com/ Inflation/Inflation_Rate/ Historical_Oil_Prices_Table.asp), Public Spending (SPE) is measured as total real spending by the Government in million dollars and has been taken from ( http://www.usgovernmentspending.com/spending_chart_1940_2017USk_13s1li011mcn_F0 .

Clearly, excluding the oil price from the analysis of the causal link between energy consumption and growth may cause misleading results, to the extent that energy consumption and oil prices are connected. The inclusion of public spending allows us to control for other demand-side factors in the US growth.

All the data is plotted in Fig 1 . Alongside the graphs of the variables we have the plot of the Flexible Fourier form that approximates the structural breaks in the variables. The data is measured annually and the sample covers the period from 1949 to 2014.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205671.g001

We conduct a unit root test on the variables chosen for this study. To this end, the LM based Flexible Fourier unit root test due to [ 40 ] is applied. The results of the test are shown in Table 3 below.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205671.t003

From the table we find that the null hypothesis of a unit root in all the variables can be rejected at least at the 10% significance level, except for the variable GDP t . The variables EC t energy consumption, OP t oil price and SPE t government spending are all found to be stationary I(0) processes. Since GDP t is found to contain a unit root, the variable is differenced to be made stationary. The variable Δ GDP t is therefore enters the FFF-VAR model in differenced logarithmic form, describing economic growth, and hereafter labelled as GROWTH t

Table 4 presentes the results of the nonlinear causality tests using the FFF-VAR model. The first column lists the possible causality relations, while the second column provides the associated p-values to test the null of Granger non-causality.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205671.t004

The results show that the null hypothesis of Granger non-causality cannot be rejected for almost all possible pairs except for three cases. We can conclude energy consumption Granger causes economic growth; oil prices Granger cause energy consumption and alternatively, energy consumption Granger causes oil prices. This implies a feedback effect between oil prices and energy consumption. The nonlinear causality test provides evidence supporting the growth hypothesis , meaning that policies aimed at limiting energy consumption will in turn diminish economic growth. It is also interesting to note that in the nonlinear framework bidirectional causality is detected between energy consumption and oil prices. The fact that the price of oil causes energy consumption, underlies the fact that the US has not yet managed to divest from one of the most polluting fossil fuels. Also, what we find is that there are no changes in public spending to address the effects of an increase in energy consumption in the case of the US economy.

To test whether the FFF-VAR is a better fit to the data than the standard linear VAR, we conduct an F-test on the trigonometric terms, or in other words, we conduct a test for linearity. We set up the null hypothesis that the trigonometric terms are equal to zero. The results of the test are given in Table 5 below:

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205671.t005

The results show that we can reject the null hypothesis of the trigonometric variable exclusión test. This implies that the trigonometric terms are significant and they do approximate the small but several breaks that may exist in the data. Based on these results we can therefore conclude that the FFF-VAR provides a better fit to the data.

Given the results of the FFF-VAR we proceed to compare the causality results with those of a linear VAR. To determine how our results would compare if we had ignored the possibility of multiple structural breaks that could be gradual, we conduct a bootstrap versión of the [ 41 ] tests by implementing a procedure due to [ 42 ]. This model, in contrast to the FFF-VAR, is linear and takes in to account the order of integration of the variables. Accordingly, as a prelude to the Granger causality tests in a linear VAR framework, we conduct a comprehensive set of unit root tests to determine the order of integration of the variables. The results are shown in Table 6 below:

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205671.t006

In the first two columns we conduct the standard ADF tests in levels and differences. We cannot reject the unit root null in levels, but we can reject in first differences, thereby concluding that the data is I(1). It is well known that the ADF tests suffer from low power and accordingly we conduct a battery of unit root tests being the GLS detrended ADF tests (ADF-GLS) due to [ 43 ], M-type test due to [ 44 ] and the KPSS unit root test where the null is of stationary against the alternative of non-stationarity based on the procedure of [ 45 ]. The results broadly conclude that the data is I(1). The only exception is that of oil prices ( OP t ) where we cannot reject the null of stationarity using the KPSS test. However, in general, we can conclude that all the variables are I(1). We also carried out panel unit root tests, due to [ 46 ] and [ 47 ] for a common unit root, as well as [ 48 ] and [ 49 ] for individual unit roots. The results are the same. The results are not reported for brevity, but are available from the authors on request.

The results of no-break unit root tests stand in stark contrast to the unit root tests using flexible fourier form to approximate smooth breaks. This is not surprising as we know the unit root tests have low power to reject the null, especially in the case where structural breaks are present in the data (e.g. [ 50 ]). This is also true when there are multiple breaks in the data and the breaks can be gradual [ 40 ]. Our results shown in Table 3 where we can reject the unit root null using the Enders and Lee (ibid) method, underscores that we are using more powerful tests where we reject the unit root null taking into account the unknown nature of breaks. The results emphasise that ignoring the possible presence of multiple and gradual structural breaks in the data can lead to under-rejection of the unit root null hypothesis.

Nonetheless, based on our finding that the variables are I(1) in this particular linear form case, we proceed to carry out the [ 42 ] procedure to tests for Granger causality (We thank an anonymous referee for this comment). This procedure extends the [ 41 ] methodology. Since the [ 41 ] procedure includes non-stationary I(1) variables in the VAR making adjustments to the chosen lag length, the variables appear in the VAR in level form. The results are in Table 7 below:

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205671.t007

The modified Wald (MWALD) tests are given in the second column of Table 2 and alongside in the three adjacent columns we tabulate the boostrapped critical values at the 1%, 5% and 10% significance levels respectively. In all the possible pairwise combinations, we find the MWALD test is lower than the bootstrapped critical values, except for the null hypothesis that oil prices ( OP t ) do not Granger cause energy consumption ( EC t ). This implies that except for oil prices causing energy consumption we cannot find any evidence of causality in all the possible pairwise combinations. The results in general show fewer rejections of the null of Granger non-causality in comparison to the results we find using the FFF-VAR. Caution needs to be exercised though, as the GDP data in this case is in levels, whereas in the FFF-VAR model the GDP data was in growth form.

Conclusions

There is extensive literature that analyzes the causality between growth and energy consumption; however, most such studies use a bivariate approach and thus face the problem of the omission of relevant variables. Such an omission could explain the inconclusive results on the relationship between energy and growth. In addition, the studies that use multivariate models in an attempt to overcome this limitation have selected the additional variables on an ad hoc basis, thus introducing bias into the results. What is more, most studies have analyzed the existence of causality between energy and growth in a linear context, despite a broad body of literature that highlights the importance of taking into account the nonlinear dynamics in the variables associated with studies on energy consumption and economic growth.

In this paper, we overcome the limitations in the literature and analyze the relationship between energy consumption and growth in a multivariate context, choosing variables according to the probability of inclusion reported in [ 19 ]. The variables used in the model are growth, energy consumption, public spending and oil prices for the US. Besides, the existence of causality between these variables is analysed using a FFF- VAR, which approximates possible structural breaks in the variables, thereby overcoming the limitations in linear studies.

The linear causality test results indicate that there is no causality between GDP and energy consumption, and therefore a prescriptive policy measure would be to reduce energy consumption in the US without affecting the country’s economic growth. This is referred to in the literature as the ‘neutrality hypothesis’. In contrast, the nonlinear model supports the so-called ‘growth hypothesis’, since causation is found running from energy consumption to growth. This implies that a reduction in energy consumption would in fact adversely affect growth. In light of the above, it can be argued that since linear tests are unable to identify certain causal relationships, they can lead to erroneous conclusions which can have consequences for economic policy. The nonlinear methodology allows us to capture causal relationships between the other variables of the system that the linear approach fails to detect. Thus, based on the results of the linear model we would be inclined to draw the conclusion that the price of oil causes energy consumption; however, the nonlinear procedure indicates more to this relationship that there is mutual causality between the two variables. To sum up, we find the FFF-VAR results depart from those of the linear VAR. Given the evidence of nonlinearity in the data, we would be inclined to rely on the results obtained from the FFF-VAR since the Fourier form has better size and power properties; in which case there is support for the growth hypothesis, rather than the neutrality hypothesis leading to a different set of policy prescriptions.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 21. Péguin-Feissolle, A., & Terasvirta, T. (1999) A general framework for testing the Granger noncausality hypothesis, Working Paper Series in Economics and Finance, Stockholm School of Economics, 343.

- 46. Breitung J. The local power of some unit root tests for panel data. Berlin: Humboldt-Universität; 1999.

- Open access

- Published: 10 June 2016

Causality between bank’s major activities and economic growth: evidences from Pakistan

- Saba Mushtaq 1

Financial Innovation volume 2 , Article number: 7 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

5882 Accesses

6 Citations

Metrics details

Banking is an important sector of Pakistan’s economy. It is general consideration that bank’s major activities saving and lending have positive impact on economic growth. So the aim of this study is to investigate this consideration and also investigate that either growth led deposits and credits, or deposit and credits led growth means the purpose of this study is to investigate the direction of this relationship.

Johansen test of Co-integration and Granger Causality is employed by using time series data of Pakistan from 1961 to 2013.

The results show that two major activities of banking sector that are saving and lending don’t have any long run or short run causality towards economic growth so the general consideration of positive impact of these activities proved wrong in case of Pakistan. However there is unidirectional causality running from GDP growth to credit provided by banking sector which shows that economic prosperity or economic growth will have a major impact on lending activities of banks meaning that demand following hypothesis is true for Pakistan in case of GDP and Bank’s credit or we can say that growth led Bank’s credit in Pakistan.

Conclusions

Hence Government and central bank should make policies by keeping this fact in consideration that bank’s two major activities that are saving and lending does not have impact on GDP growth. There might be other factors which influence economic growth of Pakistan more than banking sector these activities, which can be bank’s profitability, human resource, technology, infrastructure and other sectors of the economy. However GDP growth affects bank’s lending activities so during high economic growth year central bank and private bank’s management should introduce easy loans for businesses and industries and during poor economic growth years personal loan’s new schemes should be introduce by banks.

Banking sector is considered an important sector for economic growth there are two basic activities done by banks one is attract customer to save their savings (by giving certain amount called interest) and it is known as bank deposits and other is lending activities that is to provide loans for investment or personal uses and take interest on them. Government of Pakistan and Central bank make different rules and regulations for banks with the aim to increase economic growth in long run. These rules and instructions also include increase in deposits with banks and provide loans on easy terms and condition. Central bank instructs and orders banks to introduce different types of accounts to attract savers to open and keep their savings in bank accounts with the perception that in long run it will contribute to enhance economic growth.

Banks uses these deposits to further lend money so it is compulsory for Government to know the fact that which activity of banking sector has cointegration with economic growth so Government can make effective policies in future for the prosperity of country.

Banking sector is considered as one of the major industry of Pakistan’s economy and in government policies government always tries to make policies in order to accelerate banking sector’s activities.

But Pakistan is a country in which most of the banks are private and only few banks are owned by government. So if private banks will earn profit then this will not be beneficial for government. In this case only bank’s activities are the part of private banks that can be part of interest for government because it is considered to have effect on economic growth so because of this reason I select Pakistan as a country for my study.

Lack of data availability was a big limitation for this study so I tried to include the time period in which data was available for all three variables.

Bank’s activities (that are deposits and lending) are the key things that will not only affect economy but also will affect the population and government of the country so the purpose of this study is to investigate the direction between these two activities and economic growth and to know the fact that either this relationship is unidirectional or bidirectional.

There has been done a lot of work in economic literature about banking sector but there are very few studies that considered specifically deposits or credits side of banking sector and there causal directional relationship with economic growth but In Pakistan no one considered causal relationship specifically between pooling and lending activities of bank and economic growth but combine studies have been done by using bank deposit and bank’s credit as a determinant of GDP or by keeping credits or deposits of banks as proxy of financial development with other additional variables. So this study will provide a guideline to policy makers that whether it is realistic to consider bank deposit and bank’s provided loans to increase the economic growth in Pakistan and also this study will tell to bank managements that either GDP growth has any short run or long run impact on banking sector’s these activities. Secondly according to general consideration bank deposits and lending activities have positive impact on economic growth but this study concludes opposite results so the purpose is to investigate the real scenario that is also the base for narrow selection of bank’s these two activities.

The paper is organized as Introduction this section, section 2 presents review of literature, sections 3 presents data, methodology and results and section 4 concludes the paper.

Review of literature

Patrick ( 1966 ) first discussed the causality direction as demand-following and supply leading hypothesis. In 1988 Mckinnon buttressed this statement.

Demand-following hypothesis (growth led finance):

When because of economic growth, demand for financial services will increase and will result financial development. It is Demand-following hypothesis.

Supply-Leading hypothesis (finance led growth)

According to this hypothesis if there will be more activities of financial institutions then this will lead towards increase in productive capacity of a particular economy. And in this hypothesis causal relationship runs from financial development to growth.

Studies related to bank’s deposits and economic growth

Researchers concluded different result for different countries. Some researchers concluded that there is no relationship between bank’s deposits and economic growth such as Kumar and Chauhan ( 2015 ) did study in India by using cointegration and granger causality and concluded that saving deposits with commercial bank does not granger cause GDP of India.

However according to some researcher there is unidirectional causal relationship running from economic growth to bank’s saving.

Liang and Reichert ( 2006 ) found causal relationship between financial sector development and economic growth of developing and advance countries. They concluded that causality run from economic development to financial sector development. However this causal relationship is strong in case of developing countries as compare to advance countries.

Tahir ( 2008 ) did study in Pakistan and concluded that there is unidirectional causality running from economic development to financial development both in short run and long run. Real per capita GDP was used as a proxy of economic development while ratio of domestic credit to GDP, total capital formation to GDP, weighted average savings interest rate minus current GDP deflator and GDP deflator were used for financial development.

Awdeh ( 2012 ) did study in Lebanon and concluded that there is one way causality running from economic growth to banking or financial sector so this study supports demand following or growth led finance hypothesis.

Some researchers believe that there is bidirectional relationship between bank’s deposits and economic growth.

Aurangzeb ( 2012 ) concluded that banking sector does a significant contribution in the economic growth of Pakistan by using regression and granger causality method. Regression result indicates that deposit, investment, advances, profitability and interest earnings have positive significant impact on economic growth of Pakistan. He further found that there is bidirectional causality between deposits, advances and profitability with economic growth while unidirectional causality running from investment and interest earning to economic growth of Pakistan.

Following studies concluded that bank’s deposits have significant positive impact on economic growth.

Babatunde et al. ( 2013 ) did study in Malaysia and concluded that profitability loan and advances have positive significant impact on economic development while deposits and assets of banks does not have any impact on economic development in Malaysia.

Sharma and Ranga ( 2014 ) did study in India and concluded that saving deposits with commercial banks have positive significant impact on GDP of India.

Studies related to bank’s credit and economic growth

According to some researchers there is positive significant impact of bank’s credit on economic growth.

Korkmaz ( 2015 ) did study on 10 European countries and concluded that domestic credit provided by banking sector have effect on economic growth.

Iwedi Marshal et al. ( 2015 ) did study in Nigeria and found strong positive correlation between bank;s credit and GDP.

Nwakanma et al. ( 2014 ) concluded that there is significant long run relationship between bank’s credit to private sector and economic growth in Nigeria but without significant level of causality.

Osman ( 2014 ) investigated the impact of private sector credit on the economic growth of Saudi Arabia using ARDL model and concluded that there is long run and short run relationship between private sector credit and economic growth of Saudi Arabia. Moreover commercial bank’s credit to private sector will contribute in the economic growth of Saudi Arabia.

Emecheta and Ibe ( 2014 ) did study in Nigeria using Vector Autoregressive technique and concluded that there is positive and significant relationship between bank credit to private sector, broad money and economic growth.

However following studies concluded that there is unidirectional causality running from economic growth to bank’s credit.

Onuorah and Ozurumba ( 2013 ) did study in Nigeria and concluded that Banks credits does not granger cause GDP but GDP have effect on Bank’s credit. He further concluded that there is short run relationship between Bank credits and GDP.

Marshal et al. ( 2015 ) found the causal relationship between banking sector credit and economic growth in Nigeria and concluded that there is unidirectional relationship running from GDP to banking sector credit.

These studies found unidirectional causal relationship running from bank’s credit to economic growth.

Caporale et al. ( 2009 ) did study about ten new EU member countries by using granger causality test and concluded that there is unidirectional causal relationship running from financial development to economic growth in ten new EU member countries. Credit to private sector and interest rate margin to economic growth variable have been used as a proxy of financial development.

According to Obradovic and Grbic ( 2015 ) economic growth contributes to financial deepening process. They concluded that there is unidirectional causality running from private enterprise credit to GDP and household credit to GDP, to economic growth of Serbia. Moreover according to them there is bidirectional causal relationship between the share of bank credit to non-financial private sector in total domestic credit and growth rate of economy.

Alkhuzaim ( 2014 ) used cointegration and granger causality techniques and concluded that there is positive long run relationship between financial development indicators and GDP growth rate in Qatar. According to him in long run there is unidirectional causal relationship running from domestic credit provided by the bank sector to GDP growth while in short run direction of causality is opposite. Further he concluded that there is no causal relationships exist between bank credits to private sector and GDP growth rate in long run or short run.

Data, methodology and results

The basic purpose of this study was to investigate the causal relationship between banking sector two main activities (that is bank deposits and credits provided by banking sector) and GDP growth of Pakistan. The data was collected from World Bank development indicator's various issues. Annual time series data of Pakistan was used from the period 1961 to 2013.

Johansen and Juselius ( 1990 ) maximum likelihood estimation model is used to determine the cointegration between the variables. This model only describes the existence of cointegration between the variables but unable to describe the direction of causality. For this purpose Granger causality and VECM models have been use to determine direction of causality in short and long run. The mathematical form of the basic model is as under

Bank deposits % of GDP, GDP growth (annual %) and Bank credit to private sector with GDP (annual %) has been used as a proxy of Bank deposit, Economic growth and Bank’s credit respectively. Coefficient β1 in both models is expected to have positive sign in short run and long run.

Unit root test (Augmented Dickey Fuller test)

In order to use cointegration model the first condition is that all the variables must be integrated at the same order, for this purpose Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) unit root test is employed.

The equation of ADF test can be presented as under. By adding lagged values this test checks the serial correlation.

Where ε t is white noise error term and Δ Y t = Y t − Y t − 1

The results of both models, Model 1 and Model 2 are presented in the Table 1 . From the results we can conclude that all the variables are non-stationary or have unit root at their levels but after first difference they became stationary.

So this result directs us towards the test of cointegration because condition of cointegration has been fulfilled because variables are integrated at the same order for both models.

Lag length selection

For lag selection in both models all crieteria that are LR test statistics,Final Prediction error,A/C Akaike information criterion and Hannan-Quinn information criterion suggested lag 4 for model 1 and lag 2 for model no 2. Results for Model no 1 is in Table 2 and results for Model no 2 is in Table 3 .

This lag length selection will use for both cointegration and granger causality.

Cointegration test

For cointegrtion following unrestricted VAR model have to estimate:

Where Y t is n × 1 vector of variable having unit root that is GDP growth and Bank deposit for Model one and GDP growth and Bank credit in second model.

A 0 is vector of contant, n is lag no, Ai is estimated parameter’s 3 × 3 matrix and \( Et \) is error term.

If variables are cointegrated then VECM model will be employed to find the short run and long run causality instead of unrestricted VAR model.

Where I is identity matrix (n × n) and ∆ is difference operator.

Trace test and Maximum Eigen value test of Johansen and Juselius ( 1990 ) have been used.

Null hypothesis = no cointegration between bank deposit and economic growth

Alternative hypothesis = existence of cointegration between bank deposit and economic growth

Null hypothesis = no cointegration between bank’s credit and economic growth

Alternative hypothesis = existence of cointegration between bank’s credit and economic growth

Results of cointegration for both models are in Table 4 .

Cointegration result for model no 1 shows that trace statistics and Max Eigen statistics are less than their corresponding 5 % critical values and p value is more than 5 % so we can reject Alternative and can accept null hypothesis that no cointegration exist between bank deposit and economic growth.

Cointegration results for model no 2 shows that trace statistics and Max Eigen statistics are more than their corresponding 5 % critical values and p values are less than 5 % so we can reject null hypothesis and can accept alternative hypothesis that there is cointegration between bank’s credit and economic growth.

Granger causality test

In order to find the direction of causality, granger causality (1960) test has been employed because cointegration test does not tell about direction. Granger causality test used past value of a variable X in order to forecast second variable Y and shows result in a form X ganger cause Y.

Where I and j is lag lengths

Model no 1: Granger Test Pairwise

- Note: GDPG economic growth, BD bank deposits

Model no 2: Granger Test Pairwise

- Note: GDPG economic growth, BCPS Bank’s credit

Vector Error Correction Model (VECM)

According to Engel and Granger ( 1969 ) if variables are cointegrated then to analyze causality VECM vector error correction model will be use. This will analyze both long and short term causality with direction. The following VAR framework will be used to estimate VECM.

Where ε t − 1 is error correction term.

The short term causality will be analyzed using WALD test and long run causality using Granger Error correction models.

From both cointegration test and Granger causality test it is confirm that there is no relationship between Bank deposits and economic growth but bank’s credit and economic growth is integrated and from pairwise granger causality test it is concluded that causality runs from GDP or economic growth to Bank’s credits so in order to see long term and short term effect of causality VECM model will be used for model no 2 because in that model variables are cointegrated.

The result of long run causality in Table 5 describes that both coefficients have negative sign which is good however result of GDPG cause BCPS shows that corresponding probability is significant at 5 % level of significance which shows that there is long run causality running from economic growth to Bank’s credit.

However the result of BCPS cause GDPG shows that corresponding probability is insignificant at 5 % level of significance which shows that there is no long run causality running from Bank’s credit to economic growth.

WALD test has been used to test short run causality between Bank’s credit and GDP. Results are in Table 6 .

The result shows that there is short run causality running from GDP to Bank’s credit because p value is less than 5 %. However, there is no short run causality running from Bank’s credit to GDP as p value is more than 5 %.

The estimated results accuracy has been validated by different diagnostic tests that are Test of serial correlation (LM), Heteroskedasticity Test and Normality Test (Jarque bera). All tests validated the estimated results and showed that there is no serial correlation in residuals, no heteroskedasticity and residuals are normally distributed.

Test for structural break

Quandt-Andrews unknown breakpoint test has been used in order to test structural breaks within models, probabilities were calculated using Hansen’s (1997) method. Results are in Table 7 which confirmed that there is no breakpoint within the data.

This study concludes that in Pakistan which is a developing country, two major activities of banking sector that are saving and lending don’t have any long run or short run causality towards economic growth so the general consideration of positive impact of these activities on economic growth proved wrong in case of Pakistan however there is unidirectional causality running from GDP growth to credit provided by banking sector which shows that economic prosperity or economic growth will have a major impact on lending activities of banks meaning that demand following hypothesis is true for Pakistan in case of GDP and Bank’s credit or we can say that growth led Bank’s credit in Pakistan. There can be two reasons of this causal relationship.

Economic prosperity of the country will determine that whether country is good for investment so if goods will produce in country mean increase in GDP then small and medium enterprises and investor will take loans from banks for investment purpose so causality will run from GDP to bank’s credit.

Second reason can be that if GDP growth will slow so people will be poor that’s why they will take loans from banks for their personal use and not for investment purpose this can also be a reason of unidirectional causality from GDP growth to bank’s lending activities rather than bidirectional relationship.

There might be other factors which influence economic growth of Pakistan more than banking sector these activities, which can be bank’s profitability, human resource, technology, infrastructure and other sectors of the economy.

Government should make policies by considering the fact that there is no short term or long term causality running from banking activities to GDP growth however in short run and long run GDP growth affects bank’s lending activities in Pakistan. So during high economic growth year central bank and private bank’s management should introduce easy loans for businesses and industries and during poor economic growth years personal loan’s new schemes should be introduce by banks.

Alkhuzaim W (2014) Degree of Financial Development and Economic Growth in Qatar: Cointegration and Causality Analysis. Int J Econ Finance 6(6):57–69

Aurangzeb (2012) Contribution of banking sector in economic growth: a case of Pakistan. Econ Finance Rev 2(6):45–54

Google Scholar

A Awdeh (2012) Banking sector development and economic growth in Lebanon. Int Res J Finance Econ (100):53–62

Babatunde JH et al (2013) The impact of commercial banks on Malaysian economic development. Int J Mod Bus 1(3):20–31

Caporale GM et al (2009) Financial Development and Economic Growth: Evidence from Ten new EU members. German Inst Econ Res discussion paper no 940.

Emecheta BC, Ibe RC (2014) Impact of bank credit on economic growth in Nigeria: application of reduced vector autoregressive (VAR) technique. Eur J Account Auditing Finance Res 2(9):11–21

Granger CW (1969) Investigating causal relationships by economic models and cross spectral models. Econometrica 37:424–438

Article Google Scholar

Iwedi M et al (2015) Bank domestic credits and economic growth nexus in Nigeria (1980–2013). Int J Finance Accounting 4(5):236–244

Johansen S, Juselius K (1990) Maximum likelihood estimation and inference on cointegration with applications to the demand for money. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 52(2):169–210

Korkmaz S (2015) Impact of bank credits on Economic growth and inflation”. J Appl Finance Banking 5(01):57–69

Kumar S, Chauhan S (2015) Impact of Commercial Deposit in Banks with GDP in context with Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojna. BVIMSR’s J Manage Res 7(1):53–59

Liang H-Y, Reichert A (2006) The Relationship between economic growth and Banking sector development. Banks Bank Syst 1(2):19–35

Marshal I et al (2015) Causality modeling of the banking sector credits and economic growth in Nigeria. IIARD Int J Banking Finace Res 1(7):1–12

Nwakanma PC et al (2014) Bank credits to Private sector : Potency and Relevance in Nigeria’s Economic Growth Process. Account Finance Res 3(02):23–35

Obradovic S, Grbic M (2015) Causality relationship between financial intermediation by banks and economic growth: Evidence from Serbia. Prague Econ Pap 24(01):60–72

Onuorah, AC-C, Ozurumba BA (2013) Bank Credits: An Aid to Economic Growth in Nigeria. Inf Know Manage 3(3):41–51

Osman E GA (2014) The impact of private sector credit on Saudi Arabia Economic Growth (GDP): An Econometrics model using (ARDL) Approach to Cointegration. Am Int J Soc Sci 3(6):109–117

Patrick H (1966) Financial Development and Economic Growth in Underdeveloped Countries. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 174–189

Sharma D, Ranga M (2014) Impact of saving deposits of commercial banks on GDP. Indian J Appl Res 4(9):95–97

Tahir M (2008) An investigation of the effectiveness of financial development in Pakistan. Lahore J Econ 13(2(winter)):27–44

World development indicators(WDI), World Bank

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to her Father Rana Mushtaq Ahmed, Mother Rukhsana Begum and siblings (Zohaib, Rida, Saqlain and Faiza) for their cooperation, support and encouragement.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Karachi University Business School, University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan

Saba Mushtaq

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Saba Mushtaq .

Additional information

Competing interests.

Author of the paper understand “Financial Innovation” Journal Policy on declaration of interests and declare that she has no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

I am the only author of this research Paper.

Authors’ information

Saba Mushtaq is PhD scholar at Department of Business Administration (Karachi University Business School), University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mushtaq, S. Causality between bank’s major activities and economic growth: evidences from Pakistan. Financ Innov 2 , 7 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-016-0024-y

Download citation

Received : 08 February 2016

Accepted : 27 April 2016

Published : 10 June 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-016-0024-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Granger Causality

- Cointegration

- Economic Growth

- Bank deposits

- Bank’s credit

JEL classification

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, energy diversification and economic development in emergent countries: evidence from fourier function-driven bootstrap panel causality test.

- 1 Department of Econometrics, Sakarya University, Sakarya, Turkey

- 2 College of Business Administration, Abu Dhabi University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

- 3 Department of Economics, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Ankara, Turkey

- 4 Nord University Business School, Bodø, Norway

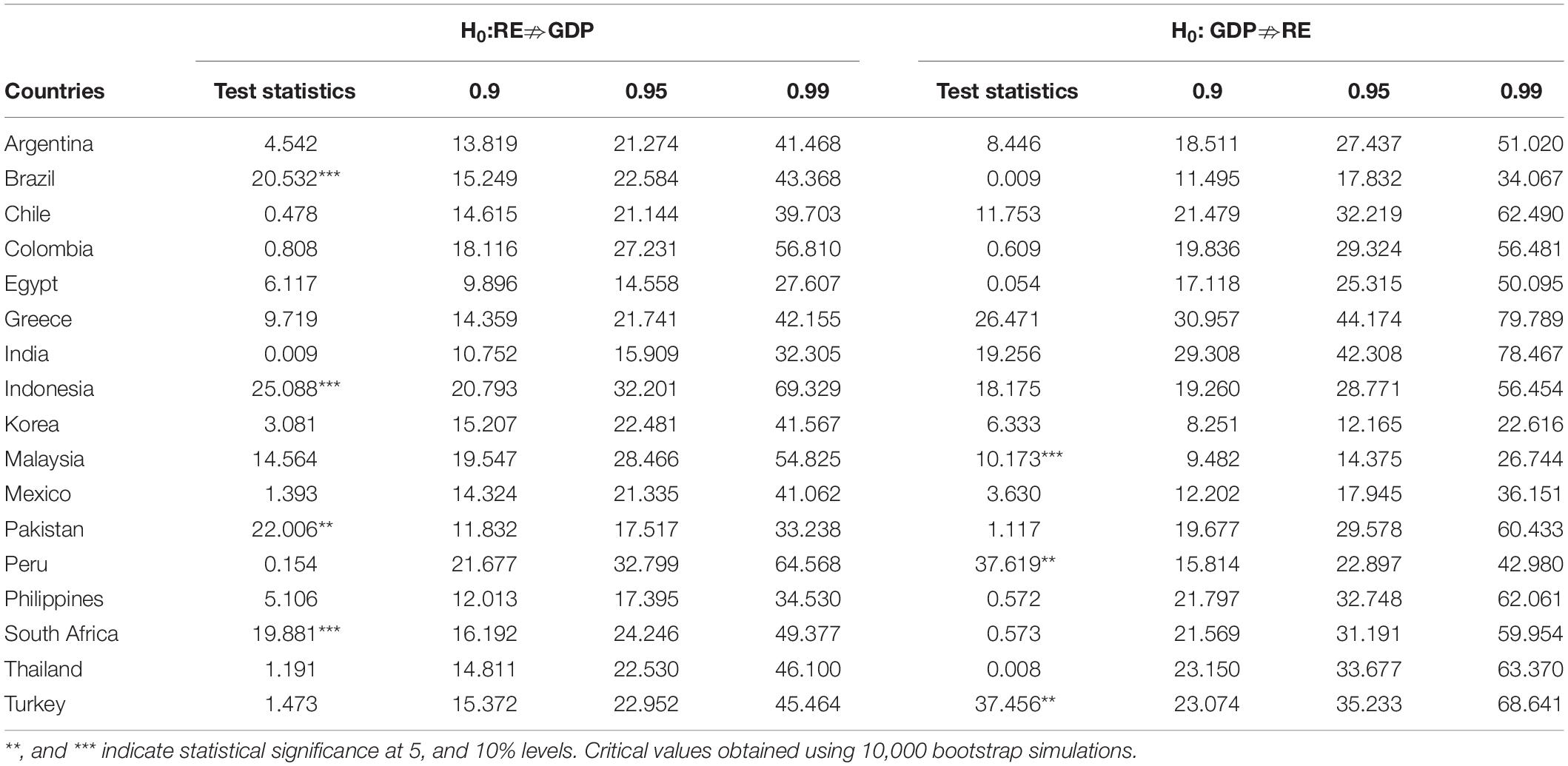

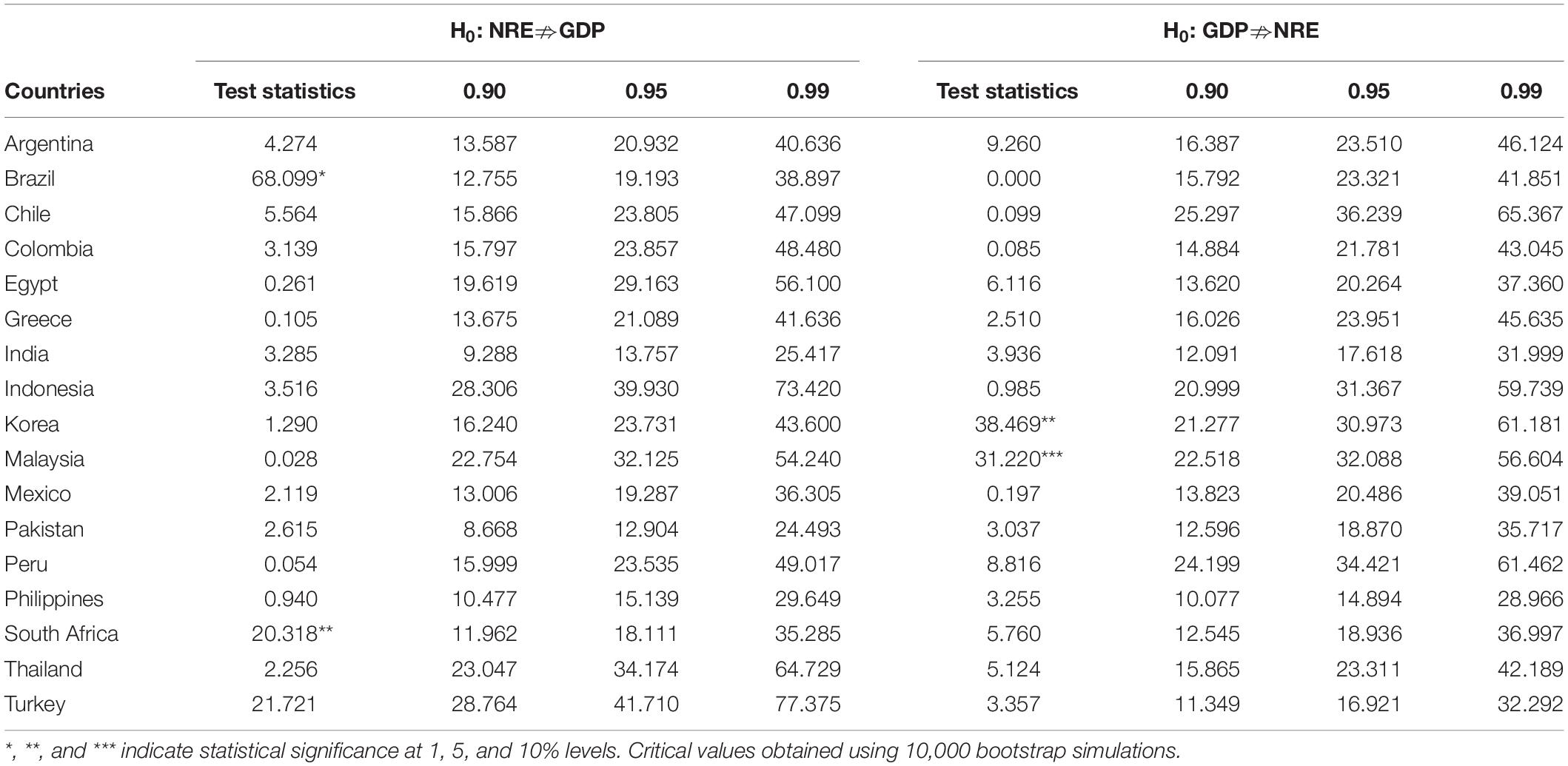

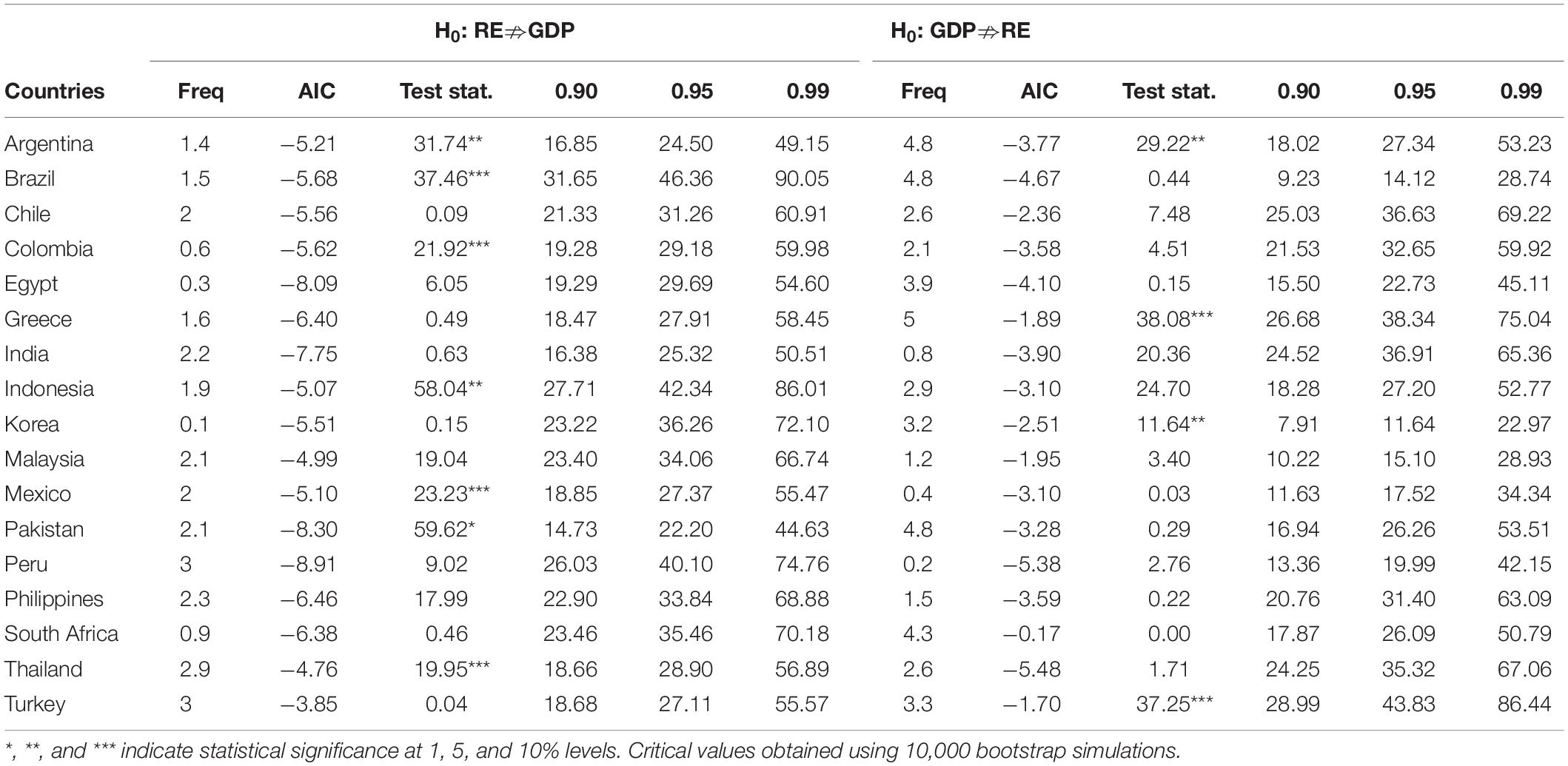

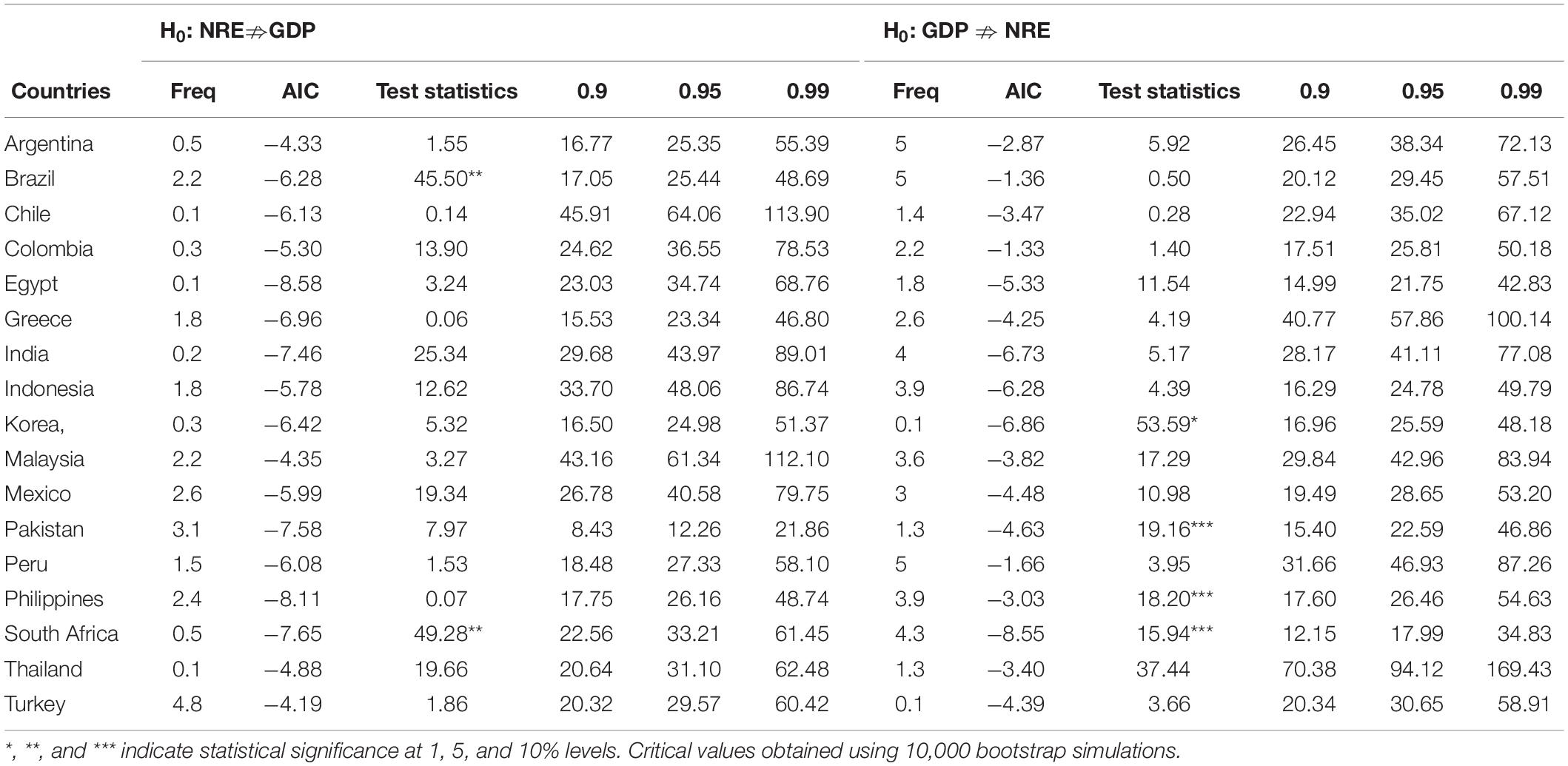

Energy is a crucial development indicator of production, consumption, and nation-building. However, energy diversification highlighting renewables remains salient in economic development across developing economies. This study explores the economic impact of renewables (RE) and fossil fuel (NRE) utilization in 17 emerging nations. We use annual data with timeframe between 1980 and 2016 and propose a bootstrap panel causality approach with a Fourier function. This allows the examination of multiple structural breaks, cross-section dependence, and heterogeneity across countries. We validate four main hypotheses on the causal links attached to the energy consumption (EC)-growth nexus namely neutrality, conservation, growth, and feedback hypotheses. The findings reveal a causal relationship running from RE to GDP for Brazil, Egypt, Indonesia, Korea, Pakistan, and the Philippines, confirming the growth hypothesis. Besides, the results validate the conservation hypothesis with causality from GDP to RE for China, Colombia, Egypt, Greece, India, Korea, South Africa, and Turkey. We identify causality from NRE to GDP for Pakistan, Mexico, Malaysia, Korea, India, Greece, Egypt, and Brazil; and from GDP to NRE for Thailand, Peru, Malaysia, India, Greece, Egypt, and Colombia. We demonstrate that wealth creation can be achieved through energy diversification rather than relying solely on conventional energy sources.

Introduction

Energy has long been considered a substantial driver of economic growth, and traditional energy demand, following an upward trend for many decades ( Sadorsky, 2009 ; Ellabban et al., 2014 ). However, from the beginning of the century, countries have been exposed to different energy-connected issues worldwide, and the reliance on conventional energy has generated grave international concerns ( Owusu and Asumadu, 2016 ). It has become common knowledge that increasing use of conventional energy sources such as oil, petroleum, and coal, to achieve economic growth—is associated with severe environmental degradation that affects both environment and human health. Nevertheless, emerging nations consider restrictions on carbon-intensive energy as harmful to actions targeted toward development ( Edenhofer et al., 2014 ). Thus, industrial states are forced to create and finance schemes to deal with climate change primarily driven by industrial operations. These problems propelled international communities and institutions to search for regular energy alternatives ( Ozturk and Bilgili, 2015 ). Besides, specialists highlight that cleaner energy sources can actively mitigate carbon emissions and preserve environmental quality ( Yildirim, 2014 ; Owusu and Asumadu, 2016 ; Danish et al., 2017 ). Therefore, a vast literature that unpacks the story of complex energy (EC)–growth nexus exists ( Wolde-Rufael, 2009 ; Sarkodie et al., 2020 ).

A broad array of scholars has explored the dynamic nexus between clean energy and development for various countries via regional panel data sets using various methodologies and documented mixed empirical findings. For example, some scholars demonstrate a positive relationship between energy consumption (either renewable or non-renewable) and economic growth, such as Apergis and Payne (2011b) , Al-Mulali et al. (2014) , Pao et al. (2014) , Cetin (2016) , Destek (2016) , Afonso et al. (2017) , Adams et al. (2018) , Venkatraja (2019) , Le and Sarkodie (2020) , among others. By contrast, other scholars reveal a negative relationship between energy consumption and economic growth. Higher consumption of energy, viz. energy intensity imposes negative consequences on economic development, as demonstrated by Apergis and Payne (2010) ; Ocal and Aslan (2013) , Maji (2015) ; Venkatraja (2019) , Awodumi and Adewuyi, 2020 . Between positive and negative impact, some studies demonstrate a neutral effect between energy consumption and growth —which means that higher or lower energy consumption has no impact on economic growth, as demonstrated by Ozturk and Acaravci (2011) ; Aïssa et al. (2014) , Ozcan and Ozturk (2019) ; Razmi et al. (2020) , among others.

The mixed empirical findings that examine the causality between energy and economy can be categorized into four main hypotheses namely the neutrality, conservation, growth, and feedback theories ( Ozturk, 2010 ; Payne, 2010 ). The neutrality hypothesis highlights no causal link between energy and growth such that structural changes in economic and energy portfolio have no impact on economic and energy growth trajectory ( Apergis and Payne, 2009 ). The conservation hypothesis confirms a causal link from growth to energy—revealing that the implementation of energy conservation and management policies has no economic effect ( Jakovac, 2018 ). The growth hypothesis underlines a causal link from energy to growth. Thus, efforts to decrease energy consumption will hamper economic growth ( Yildirim et al., 2012 ). The feedback hypothesis indicates a mutualistic connection between energy and growth—implying that the institutionalization of economic and energy policies targeted at reducing either energy, growth, or both may backfire in the face of economic prosperity and energy security ( Ayres, 2001 ). The non-existence of consensus on the causal relationship between energy and growth indicates a gap in the literature that continuously requires further studies to confirm such findings. These mixed findings signal an ongoing debate that future studies are invited to participate.

This study contributes to the ongoing debate by expanding the extant literature by analyzing the role of energy diversification in wealth creation in developing economies. The specific novel contribution that this study presents can be observed from three aspects: variables used, scope of the sample, and method employed. From the variable perspective, most studies argue that environmental degradation is driven by using non-renewable energy (NRE) for economic growth, but the implications of environmental damage cannot be ignored. This study contributes to the literature by not only focusing on the role of fossil fuels but also renewable energy. Another effort of this study is the inclusion of labor and capital into the analysis to create a multivariate system that analyzes the causal connection between energy consumption and economic growth. In this sense, our study proposes a panel bootstrap causality test to explore the linkage in emerging countries. Thus, from the sampled perspective, we utilize both renewables (RE) and fossil fuel utilization (NRE) in economic growth function. We assess the performance of both and establish the coherence of investing in renewables from 1990 to 2016 across 17 emerging countries including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Egypt, Greece, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, South Africa, Thailand, and Turkey. These countries are adopted based on the newest 2020 Morgan Stanley Capital International classification (MSCI 2020) and data completeness. To the best of our knowledge, no study has used this set of countries. Hence, involving this set of countries as a sample can supply new information regarding the EC-growth nexus in MSCI’s group of emerging countries. There are mainly two reasons for selecting emerging countries. First, emerging countries require high energy needs namely fossil fuels to boost economic development ( Waheed et al., 2019 ). Second, the main reason for the outgrowth in CO 2 emissions during the twenty-first century was mainly attributed to a surge in CO 2 emissions from developing countries ( Crippa et al., 2020 ). Thus, emerging countries may tend to renewable energy sources to induce economic growth. From a methodological perspective, contrary to existing studies that utilize Granger causality technique, we apply a bootstrap panel causality methodology with a Fourier function. The novel effort of this study is to handle an econometric model that is superior to its counterparts in the available literature. In this way, structural breaks, cross-section dependence, and cross-country heterogeneity can be controlled.

Incorporating structural breaks into the analysis reveals mixed results across the sample of emerging countries. First, most sample countries have no significant causal relationship between energy utilization and economic growth, even after structural breaks are controlled. This finding suggests the dominance of the neutrality hypothesis, which indicates that energy utilization and economic growth are mutually independent. Second, in terms of causal relationship between GDP and RE, the study found that six emerging economies, namely, Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, and Thailand demonstrate a significant causal relationship from GDP to RE consumption—which supports the conservation hypothesis. Contrary, Greece, Korea, and Turkey are in support of the growth hypothesis where a significant causal relationship is found from RE to GDP. In terms of the relationship between NRE and GDP by controlling for structural breaks, only Brazil exhibits unidirectional causality from NRE to GDP. A causal relationship running from GDP to NRE is confirmed in Korea, Pakistan, and the Philippines. Besides, South Africa is the only country where the two causality-links are present.

Overall, the findings from this study are in support of past literature such as Ozturk and Acaravci (2011) ; Destek and Aslan (2017) , which found unidirectional causal links in MENA countries. This study also differs from Kahia et al. (2017) , which illustrates a bi-directional causal relationship between both energy sources and economic growth—demonstrating the substitutability of energy sources to boost economic growth in MENA countries. In the context of fossil energy consumption, our results demonstrate significant inconsistency with Pao and Tsai (2011) . Their findings offer significant unidirectional and bi-directional causality between energy utilization and economic growth in Brazil and India. We deduce that the current study contributes to the literature and provides a significant heterogeneity across emerging countries and demonstrates the role of considering a structural break in the causal relationship between energy and economic growth.

This study is organized as follows: literature review, description of data underlying the analysis and methodology, detail empirical results, and highlights from the study with policy implications.

Literature Review

Efforts to achieve stable growth and preserve environmental quality are fast transforming into a hot topic across the globe among governments, academics, international institutions, and various stakeholders involved. Despite the extensive literature on the EC-economic growth link since the influential study of Kraft and Kraft (1978) , there has been no consensus among scholars about the direction of causality ( Ozcan and Ozturk, 2019 ). Scholars have also extensively examined the link between aggregate NRE/RE and economic growth. For example, based on the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) technique and its variations, Afonso et al. (2017) indicated that NRE actively promotes growth in Turkey. Using the same methodology, Dogan (2016) obtained similar outcomes for a panel of 28 countries. By applying fully modified ordinary least square (FMOLS), dynamic ordinary least squares, and Granger causality in the context of Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), Al-Mulali et al. (2014) , Adams et al. (2018) , offered argument in favor of the growth effects of NRE consumption. Ozturk and Bilgili (2015) confirmed such findings for biomass energy in SSA via dynamic panel OLS analysis.

Given the relationship between aggregate energy consumption and growth, scholarly evidence points out the positive impact of the latter on the former, regardless of the methodology used [e.g., Lee and Chang (2008) in the case of Asia and Pao and Tsai (2011) for BRIC countries]. Considering total RE, based on OLS analysis applied for China, Fang (2011) noted similar results. This is in line with Apergis and Payne (2011b) , who applied FMOLS for six states in Central America and documented that RE consumption enhances growth. In contrast, ARDL-supported findings of Razmi et al. (2020) show no substantial long-run effect of RE on development in Iran, despite some positive short-run impact. Using the bootstrap panel causality, Ozcan and Ozturk (2019) highlighted similar outcomes for RE in emerging countries.

Using various causality analyses, many authors highlight that NRE Granger causes growth ( Aydin (2019) / OECD members; Kahia et al. (2016) /MENA net oil-exporters; Kahia et al. (2017) /MENA net oil-importers). Similar outcomes are also underlined for emerging nations by Apergis and Payne (2011a) ; Destek and Aslan (2017) . In contrast to common evidence, using the ARDL bound testing approach, Ozturk and Acaravci (2011) showed an insignificant impact of electric power on growth in the MENA region.

A few authors focus on specific non-renewable energy sources such as oil, natural gas, and coal and provide support for their persuasive power to enable economic growth. For example, Bloch et al. (2015) applied ARDL and Granger methodologies to show the positive implications of oil and coal for growth in China. This dovetails research by Caraiani et al. (2015) in the context of emerging European countries for oil, gas, coal, and RE. Although the ARDL model of Bildirici and Bakirtas (2014) revealed a Granger causality between oil and growth in the context of Brazil, Russian, India, China, Turkey, and South Africa, mixed outcomes are presented for natural gas and coal. However, Apergis and Payne (2010) used FMOLS and panel causality specifications to emphasize that coal use adversely affects development in emerging economies.

The impact of NRE on growth among leading oil producers in Africa between 1980 and 2015 revealed an asymmetric effect of the former on economic growth and CO 2 emission in all nations under analysis, except Algeria ( Awodumi and Adewuyi, 2020 ). Findings from the study emphasized that in Nigeria, positive changes in NRE consumption hinders growth and dilutes CO 2 emissions. In Gabon, an increase in NRE consumption sustains growth and environmental health. In the case of Egypt, the consumption of NRE types has no substantial inferences on environmental quality as it enables higher rates of growth. For Angola, positive changes in NRE use lead to better economic growth, although the impact on emissions is mixed across time and fuel type. Thus, it seems imperative for policy-making in African oil-producing states to examine ways to promote RE technologies in the quest for growth—if they maintain the use of their rich resources-petroleum and natural gas. Mechanisms for the reward and sanctions should be put in place to enhance compliance with environmental rules.

Based on heterogeneous panel data analysis, other studies explored the nexus of RE consumption and growth for E-7 (China, India, Brazil, Mexico, Russia, Indonesia, and Turkey) countries between 1992 and 2012 and pointed out a long-run connection among GDP, RE use, and other variables. In other words, RE consumption facilitates real economic growth in E-7 countries.

The implications of both RE and NRE on growth in 17 emerging nations using bootstrap panel causality revealed that the growth hypothesis holds only for Peru in the RE scenario ( Destek and Aslan, 2017 ). The conservation hypothesis is confirmed for Thailand and Colombia (unidirectional causality spanning from growth to EC); the feedback hypothesis is confirmed for South Korea and Greece, and the neutrality hypothesis is valid for the remaining 12 selected states (no link between energy consumption and growth). In the case of NRE consumption, there is unidirectional causality from energy consumption to growth in the case of China, Colombia, Mexico, and the Philippines (the growth hypothesis). Besides, unidirectional causality is observed from growth to NRE in the context of Egypt, Peru, and Portugal; bi-directional causality between NRE use and economic growth for Turkey (the feedback hypothesis); and no relationship between energy consumption and growth (the neutrality hypothesis) for the remaining emerging markets.

Economic growth, the main target of all states, has led to considerable academic research exploring the impact of RE on the former. The study of Maji (2015) , based on the ARDL method found a negative link between RE and growth in the long-term and a non-substantial relationship in the short-term. This confirms previous findings by Ocal and Aslan (2013) , who underlined adverse effects of RE on economic development in Turkey, South Africa, and Mexico. By contrast, Destek (2016) found a positive nexus between the two variables for India. By using panel cointegration approaches, Aïssa et al. (2014) found no causality between RE and growth in the short-term (neutrality hypothesis). Based on a similar methodology, Pao et al. (2014) examined RE and NRE-growth nexus for a panel of four emerging countries (Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea, and Turkey). They confirmed the growth hypothesis for RE and growth in the long-term, accompanied by the feedback hypothesis in the short-term.

Using a panel regression model applied to Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC) for the 1990–2015 timeframe, Venkatraja (2019) provides arguments supporting the growth hypothesis. Hence, the decrease of RE to the total energy use may have allowed faster growth in BRIC states. Shakouri and Yazdi (2017) investigated the link between various variables, inter alia, growth, RE, and energy consumption in South Africa during 1971–2015 and documented a long-run link among them and bi-directional causality between RE and growth (the feedback hypothesis). Thus, the empirical findings revealed that RE facilitates economic growth, and in parallel, growth promotes the use of clean energy sources.

Zafar et al. (2019) disaggregated energy, e.g., RE and NRE consumption, and used a second-generation panel unit root test applied to Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation states during 1990–2015 to inspect the long-term nexus between EC and growth. The findings showed the positive effect of EC, both RE, and NRE, on economic growth. Besides, the time-series individual country analysis also indicated a stimulating role of RE on growth. Moreover, the heterogeneous causality analysis identified a feedback effect among growth, RE, and NRE use. This empirical evidence highlights more investments in RE sectors and encourages the development of renewable energy to achieve energy growth. These empirical studies are summed in Table 1 .

Table 1. Extant literature on energy and economic growth nexus.

Materials and Methods

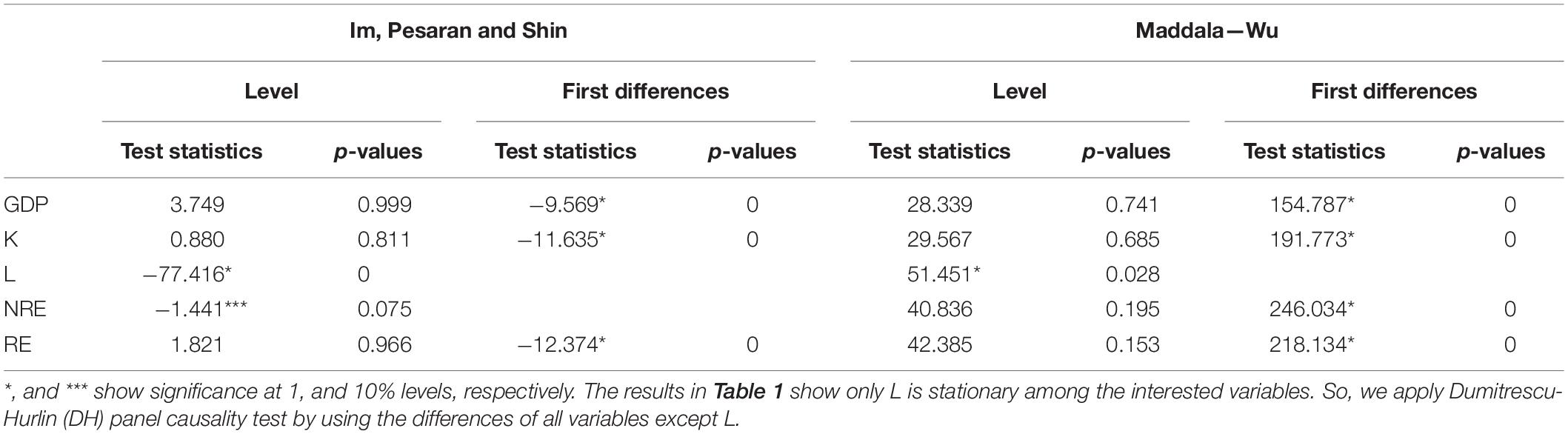

Many empirical studies that use Granger causality test have examined the causal relationship in a two-variable context, but Granger has stated that ignoring other related variables may cause spurious causality. Besides, neglected variables in a bivariate system can result in non-causality, as indicated by Lütkepohl (1982) . To remedy the omitted variable bias, this study follows Payne (2009) ; Apergis and Payne (2010) , and Ozcan and Ozturk (2019) , and test the causality between RE, NRE, and economic growth (GDP- real gross domestic product) by including measures of capital and labor. Both data on the RE and NRE are defined in billion kWh while GDP, and real gross fixed capital formation (K) in constant 2010 US$, and labor force (L) in millions. We take logarithms of all variables and use population data to convert them into per capita. We used annual data from 1990 to 2017 that was retrieved from WDI database of the World Bank and Energy Information Administration for 17 emerging countries 1 determined by Morgan Stanley Capital International classification and data completeness.

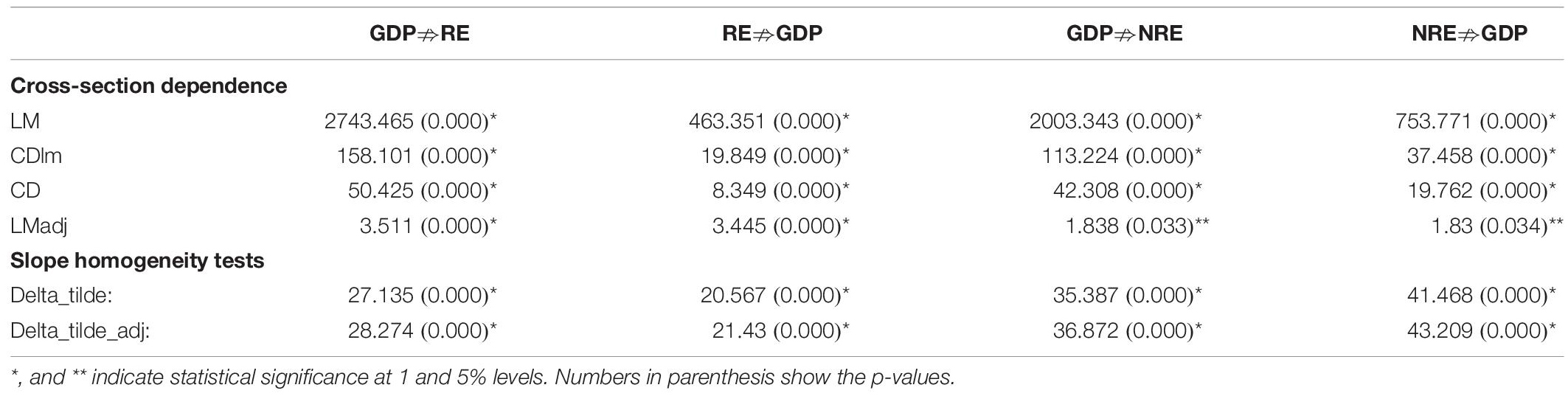

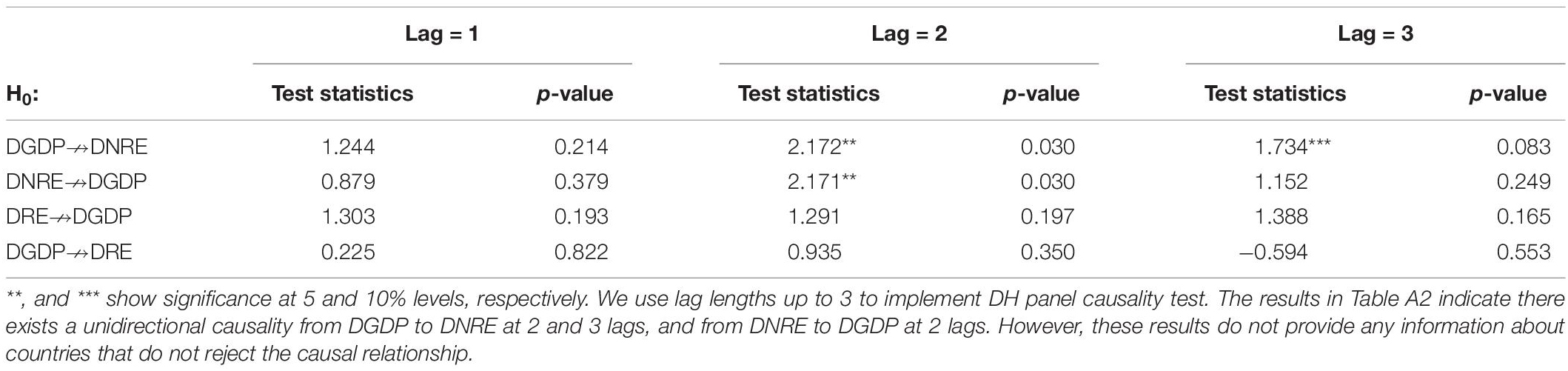

Bootstrap Panel Causality Test With Fourier Function