An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Hypothesis testing, p values, confidence intervals, and significance.

Jacob Shreffler ; Martin R. Huecker .

Affiliations

Last Update: March 13, 2023 .

- Definition/Introduction

Medical providers often rely on evidence-based medicine to guide decision-making in practice. Often a research hypothesis is tested with results provided, typically with p values, confidence intervals, or both. Additionally, statistical or research significance is estimated or determined by the investigators. Unfortunately, healthcare providers may have different comfort levels in interpreting these findings, which may affect the adequate application of the data.

- Issues of Concern

Without a foundational understanding of hypothesis testing, p values, confidence intervals, and the difference between statistical and clinical significance, it may affect healthcare providers' ability to make clinical decisions without relying purely on the research investigators deemed level of significance. Therefore, an overview of these concepts is provided to allow medical professionals to use their expertise to determine if results are reported sufficiently and if the study outcomes are clinically appropriate to be applied in healthcare practice.

Hypothesis Testing

Investigators conducting studies need research questions and hypotheses to guide analyses. Starting with broad research questions (RQs), investigators then identify a gap in current clinical practice or research. Any research problem or statement is grounded in a better understanding of relationships between two or more variables. For this article, we will use the following research question example:

Research Question: Is Drug 23 an effective treatment for Disease A?

Research questions do not directly imply specific guesses or predictions; we must formulate research hypotheses. A hypothesis is a predetermined declaration regarding the research question in which the investigator(s) makes a precise, educated guess about a study outcome. This is sometimes called the alternative hypothesis and ultimately allows the researcher to take a stance based on experience or insight from medical literature. An example of a hypothesis is below.

Research Hypothesis: Drug 23 will significantly reduce symptoms associated with Disease A compared to Drug 22.

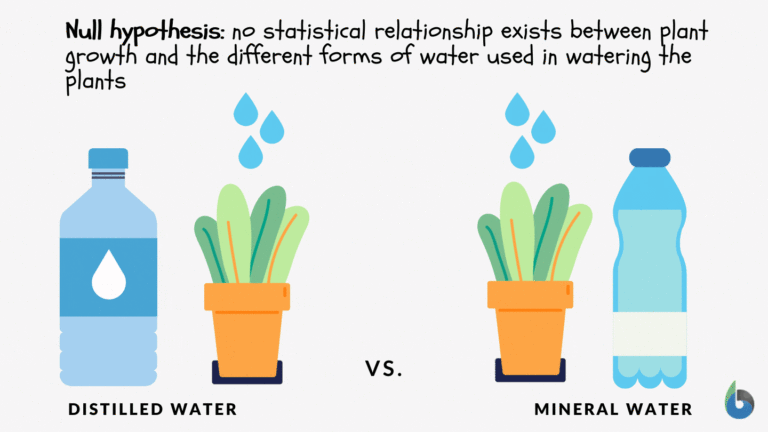

The null hypothesis states that there is no statistical difference between groups based on the stated research hypothesis.

Researchers should be aware of journal recommendations when considering how to report p values, and manuscripts should remain internally consistent.

Regarding p values, as the number of individuals enrolled in a study (the sample size) increases, the likelihood of finding a statistically significant effect increases. With very large sample sizes, the p-value can be very low significant differences in the reduction of symptoms for Disease A between Drug 23 and Drug 22. The null hypothesis is deemed true until a study presents significant data to support rejecting the null hypothesis. Based on the results, the investigators will either reject the null hypothesis (if they found significant differences or associations) or fail to reject the null hypothesis (they could not provide proof that there were significant differences or associations).

To test a hypothesis, researchers obtain data on a representative sample to determine whether to reject or fail to reject a null hypothesis. In most research studies, it is not feasible to obtain data for an entire population. Using a sampling procedure allows for statistical inference, though this involves a certain possibility of error. [1] When determining whether to reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis, mistakes can be made: Type I and Type II errors. Though it is impossible to ensure that these errors have not occurred, researchers should limit the possibilities of these faults. [2]

Significance

Significance is a term to describe the substantive importance of medical research. Statistical significance is the likelihood of results due to chance. [3] Healthcare providers should always delineate statistical significance from clinical significance, a common error when reviewing biomedical research. [4] When conceptualizing findings reported as either significant or not significant, healthcare providers should not simply accept researchers' results or conclusions without considering the clinical significance. Healthcare professionals should consider the clinical importance of findings and understand both p values and confidence intervals so they do not have to rely on the researchers to determine the level of significance. [5] One criterion often used to determine statistical significance is the utilization of p values.

P values are used in research to determine whether the sample estimate is significantly different from a hypothesized value. The p-value is the probability that the observed effect within the study would have occurred by chance if, in reality, there was no true effect. Conventionally, data yielding a p<0.05 or p<0.01 is considered statistically significant. While some have debated that the 0.05 level should be lowered, it is still universally practiced. [6] Hypothesis testing allows us to determine the size of the effect.

An example of findings reported with p values are below:

Statement: Drug 23 reduced patients' symptoms compared to Drug 22. Patients who received Drug 23 (n=100) were 2.1 times less likely than patients who received Drug 22 (n = 100) to experience symptoms of Disease A, p<0.05.

Statement:Individuals who were prescribed Drug 23 experienced fewer symptoms (M = 1.3, SD = 0.7) compared to individuals who were prescribed Drug 22 (M = 5.3, SD = 1.9). This finding was statistically significant, p= 0.02.

For either statement, if the threshold had been set at 0.05, the null hypothesis (that there was no relationship) should be rejected, and we should conclude significant differences. Noticeably, as can be seen in the two statements above, some researchers will report findings with < or > and others will provide an exact p-value (0.000001) but never zero [6] . When examining research, readers should understand how p values are reported. The best practice is to report all p values for all variables within a study design, rather than only providing p values for variables with significant findings. [7] The inclusion of all p values provides evidence for study validity and limits suspicion for selective reporting/data mining.

While researchers have historically used p values, experts who find p values problematic encourage the use of confidence intervals. [8] . P-values alone do not allow us to understand the size or the extent of the differences or associations. [3] In March 2016, the American Statistical Association (ASA) released a statement on p values, noting that scientific decision-making and conclusions should not be based on a fixed p-value threshold (e.g., 0.05). They recommend focusing on the significance of results in the context of study design, quality of measurements, and validity of data. Ultimately, the ASA statement noted that in isolation, a p-value does not provide strong evidence. [9]

When conceptualizing clinical work, healthcare professionals should consider p values with a concurrent appraisal study design validity. For example, a p-value from a double-blinded randomized clinical trial (designed to minimize bias) should be weighted higher than one from a retrospective observational study [7] . The p-value debate has smoldered since the 1950s [10] , and replacement with confidence intervals has been suggested since the 1980s. [11]

Confidence Intervals

A confidence interval provides a range of values within given confidence (e.g., 95%), including the accurate value of the statistical constraint within a targeted population. [12] Most research uses a 95% CI, but investigators can set any level (e.g., 90% CI, 99% CI). [13] A CI provides a range with the lower bound and upper bound limits of a difference or association that would be plausible for a population. [14] Therefore, a CI of 95% indicates that if a study were to be carried out 100 times, the range would contain the true value in 95, [15] confidence intervals provide more evidence regarding the precision of an estimate compared to p-values. [6]

In consideration of the similar research example provided above, one could make the following statement with 95% CI:

Statement: Individuals who were prescribed Drug 23 had no symptoms after three days, which was significantly faster than those prescribed Drug 22; there was a mean difference between the two groups of days to the recovery of 4.2 days (95% CI: 1.9 – 7.8).

It is important to note that the width of the CI is affected by the standard error and the sample size; reducing a study sample number will result in less precision of the CI (increase the width). [14] A larger width indicates a smaller sample size or a larger variability. [16] A researcher would want to increase the precision of the CI. For example, a 95% CI of 1.43 – 1.47 is much more precise than the one provided in the example above. In research and clinical practice, CIs provide valuable information on whether the interval includes or excludes any clinically significant values. [14]

Null values are sometimes used for differences with CI (zero for differential comparisons and 1 for ratios). However, CIs provide more information than that. [15] Consider this example: A hospital implements a new protocol that reduced wait time for patients in the emergency department by an average of 25 minutes (95% CI: -2.5 – 41 minutes). Because the range crosses zero, implementing this protocol in different populations could result in longer wait times; however, the range is much higher on the positive side. Thus, while the p-value used to detect statistical significance for this may result in "not significant" findings, individuals should examine this range, consider the study design, and weigh whether or not it is still worth piloting in their workplace.

Similarly to p-values, 95% CIs cannot control for researchers' errors (e.g., study bias or improper data analysis). [14] In consideration of whether to report p-values or CIs, researchers should examine journal preferences. When in doubt, reporting both may be beneficial. [13] An example is below:

Reporting both: Individuals who were prescribed Drug 23 had no symptoms after three days, which was significantly faster than those prescribed Drug 22, p = 0.009. There was a mean difference between the two groups of days to the recovery of 4.2 days (95% CI: 1.9 – 7.8).

- Clinical Significance

Recall that clinical significance and statistical significance are two different concepts. Healthcare providers should remember that a study with statistically significant differences and large sample size may be of no interest to clinicians, whereas a study with smaller sample size and statistically non-significant results could impact clinical practice. [14] Additionally, as previously mentioned, a non-significant finding may reflect the study design itself rather than relationships between variables.

Healthcare providers using evidence-based medicine to inform practice should use clinical judgment to determine the practical importance of studies through careful evaluation of the design, sample size, power, likelihood of type I and type II errors, data analysis, and reporting of statistical findings (p values, 95% CI or both). [4] Interestingly, some experts have called for "statistically significant" or "not significant" to be excluded from work as statistical significance never has and will never be equivalent to clinical significance. [17]

The decision on what is clinically significant can be challenging, depending on the providers' experience and especially the severity of the disease. Providers should use their knowledge and experiences to determine the meaningfulness of study results and make inferences based not only on significant or insignificant results by researchers but through their understanding of study limitations and practical implications.

- Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

All physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals should strive to understand the concepts in this chapter. These individuals should maintain the ability to review and incorporate new literature for evidence-based and safe care.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Jacob Shreffler declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Martin Huecker declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Shreffler J, Huecker MR. Hypothesis Testing, P Values, Confidence Intervals, and Significance. [Updated 2023 Mar 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- The reporting of p values, confidence intervals and statistical significance in Preventive Veterinary Medicine (1997-2017). [PeerJ. 2021] The reporting of p values, confidence intervals and statistical significance in Preventive Veterinary Medicine (1997-2017). Messam LLM, Weng HY, Rosenberger NWY, Tan ZH, Payet SDM, Santbakshsing M. PeerJ. 2021; 9:e12453. Epub 2021 Nov 24.

- Review Clinical versus statistical significance: interpreting P values and confidence intervals related to measures of association to guide decision making. [J Pharm Pract. 2010] Review Clinical versus statistical significance: interpreting P values and confidence intervals related to measures of association to guide decision making. Ferrill MJ, Brown DA, Kyle JA. J Pharm Pract. 2010 Aug; 23(4):344-51. Epub 2010 Apr 13.

- Interpreting "statistical hypothesis testing" results in clinical research. [J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2012] Interpreting "statistical hypothesis testing" results in clinical research. Sarmukaddam SB. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2012 Apr; 3(2):65-9.

- Confidence intervals in procedural dermatology: an intuitive approach to interpreting data. [Dermatol Surg. 2005] Confidence intervals in procedural dermatology: an intuitive approach to interpreting data. Alam M, Barzilai DA, Wrone DA. Dermatol Surg. 2005 Apr; 31(4):462-6.

- Review Is statistical significance testing useful in interpreting data? [Reprod Toxicol. 1993] Review Is statistical significance testing useful in interpreting data? Savitz DA. Reprod Toxicol. 1993; 7(2):95-100.

Recent Activity

- Hypothesis Testing, P Values, Confidence Intervals, and Significance - StatPearl... Hypothesis Testing, P Values, Confidence Intervals, and Significance - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

The P value: What it really means

As nurses, we must administer nursing care based on the best available scientific evidence. But for many nurses, critical appraisal, the process used to determine the best available evidence, can seem intimidating. To make critical appraisal more approachable, let’s examine the P value and make sure we know what it is and what it isn’t.

Defining P value

The P value is the probability that the results of a study are caused by chance alone. To better understand this definition, consider the role of chance.

The concept of chance is illustrated with every flip of a coin. The true probability of obtaining heads in any single flip is 0.5, meaning that heads would come up in half of the flips and tails would come up in half of the flips. But if you were to flip a coin 10 times, you likely would not obtain heads five times and tails five times. You’d be more likely to see a seven-to-three split or a six-to-four split. Chance is responsible for this variation in results.

Just as chance plays a role in determining the flip of a coin, it plays a role in the sampling of a population for a scientific study. When subjects are selected, chance may produce an unequal distribution of a characteristic that can affect the outcome of the study. Statistical inquiry and the P value are designed to help us determine just how large a role chance plays in study results. We begin a study with the assumption that there will be no difference between the experimental and control groups. This assumption is called the null hypothesis. When the results of the study indicate that there is a difference, the P value helps us determine the likelihood that the difference is attributed to chance.

Competing hypotheses

In every study, researchers put forth two kinds of hypotheses: the research or alternative hypothesis and the null hypothesis. The research hypothesis reflects what the researchers hope to show—that there is a difference between the experimental group and the control group. The null hypothesis directly competes with the research hypothesis. It states that there is no difference between the experimental group and the control group.

It may seem logical that researchers would test the research hypothesis—that is, that they would test what they hope to prove. But the probability theory requires that they test the null hypothesis instead. To support the research hypothesis, the data must contradict the null hypothesis. By demonstrating a difference between the two groups, the data contradict the null hypothesis.

Testing the null hypothesis

Now that you know why we test the null hypothesis, let’s look at how we test the null hypothesis.

After formulating the null and research hypotheses, researchers decide on a test statistic they can use to determine whether to accept or reject the null hypothesis. They also propose a fixed-level P value. The fixed level P value is often set at .05 and serves as the value against which the test-generated P value must be compared. (See Why .05?)

A comparison of the two P values determines whether the null hypothesis is rejected or accepted. If the P value associated with the test statistic is less than the fixed-level P value, the null hypothesis is rejected because there’s a statistically significant difference between the two groups. If the P value associated with the test statistic is greater than the fixed-level P value, the null hypothesis is accepted because there’s no statistically significant difference between the groups.

The decision to use .05 as the threshold in testing the null hypothesis is completely arbitrary. The researchers credited with establishing this threshold warned against strictly adhering to it.

Remember that warning when appraising a study in which the test statistic is greater than .05. The savvy reader will consider other important measurements, including effect size, confidence intervals, and power analyses when deciding whether to accept or reject scientific findings that could influence nursing practice.

Real-world hypothesis testing

How does this play out in real life? Let’s assume that you and a nurse colleague are conducting a study to find out if patients who receive backrubs fall asleep faster than patients who do not receive backrubs.

1. State your null and research hypotheses

Your null hypothesis will be that there will be no difference in the average amount of time it takes patients in each group to fall asleep. Your research hypothesis will be that patients who receive backrubs fall asleep, on average, faster than those who do not receive backrubs. You will be testing the null hypothesis in hopes of supporting your research hypothesis.

2. Propose a fixed-level P value

Although you can choose any value as your fixed-level P value, you and your research colleague decide you’ll stay with the conventional .05. If you were testing a new medical product or a new drug, you would choose a much smaller P value (perhaps as small as .0001). That’s because you would want to be as sure as possible that any difference you see between groups is attributed to the new product or drug and not to chance. A fixed-level P value of .0001 would mean that the difference between the groups was attributed to chance only 1 time out of 10,000. For a study on backrubs, however, .05 seems appropriate.

3. Conduct hypothesis testing to calculate a probability value

You and your research colleague agree that a randomized controlled study will help you best achieve your research goals, and you design the process accordingly. After consenting to participate in the study, patients are randomized to one of two groups:

- the experimental group that receives the intervention—the backrub group

- the control group—the non-backrub group.

After several nights of measuring the number of minutes it takes each participant to fall asleep, you and your research colleague find that on average, the backrub group takes 19 minutes to fall asleep and the non-backrub group takes 24 minutes to fall asleep.

Now the question is: Would you have the same results if you conducted the study using two different groups of people? That is, what role did chance play in helping the backrub group fall asleep 5 minutes faster than the non-backrub group? To answer this, you and your colleague will use an independent samples t-test to calculate a probability value.

An independent samples t-test is a kind of hypothesis test that compares the mean values of two groups (backrub and non-backrub) on a given variable (time to fall asleep).

Hypothesis testing is really nothing more than testing the null hypothesis. In this case, the null hypothesis is that the amount of time needed to fall asleep is the same for the experimental group and the control group. The hypothesis test addresses this question: If there’s really no difference between the groups, what is the probability of observing a difference of 5 minutes or more, say 10 minutes or 15 minutes?

We can define the P value as the probability that the observed time difference resulted from chance. Some find it easier to understand the P value when they think of it in relationship to error. In this case, the P value is defined as the probability of committing a Type 1 error. (Type 1 error occurs when a true null hypothesis is incorrectly rejected.)

4. Compare and interpret the P value

Early on in your study, you and your colleague selected a fixed-level P value of .05, meaning that you were willing to accept that 5% of the time, your results might be caused by chance. Also, you used an independent samples t-test to arrive at a probability value that will help you determine the role chance played in obtaining your results. Let’s assume, for the sake of this example, that the probability value generated by the independent samples t-test is .01 (P = .01). Because this P value associated with the test statistic is less than the fixed-level statistic (.01 < .05), you can reject the null hypothesis. By doing so, you declare that there is a statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups. (See Putting the P value in context.)

In effect, you’re saying that the chance of observing a difference of 5 minutes or more, when in fact there is no difference, is less than 5 in 100. If the P value associated with the test statistic would have been greater than .05, then you would accept the null hypothesis, which would mean that there is no statistically significant difference between the control and experimental groups. Accepting the null hypothesis would mean that a difference of 5 minutes or more between the two groups would occur more than 5 times in 100.

Putting the P value in context

Although the P value helps you interpret study results, keep in mind that many factors can influence the P value—and your decision to accept or reject the null hypothesis. These factors include the following:

- Insufficient power. The study may not have been designed appropriately to detect an effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. Therefore, a change may have occurred without your knowing it, causing you to incorrectly reject your hypothesis.

- Unreliable measures. Instruments that don’t meet consistency or reliability standards may have been used to measure a particular phenomenon.

- Threats to internal validity. Various biases, such as selection of patients, regression, history, and testing bias, may unduly influence study outcomes.

A decision to accept or reject study findings should focus not only on P value but also on other metrics including the following:

- Confidence intervals (an estimated range of values with a high probability of including the true population value of a given parameter)

- Effect size (a value that measures the magnitude of a treatment effect)

Remember, P value tells you only whether a difference exists between groups. It doesn’t tell you the magnitude of the difference.

5. Communicate your findings

The final step in hypothesis testing is communicating your findings. When sharing research findings (hypotheses) in writing or discussion, understand that they are statements of relationships or differences in populations. Your findings are not proved or disproved. Scientific findings are always subject to change. But each study leads to better understanding and, ideally, better outcomes for patients.

Key concepts

The P value isn’t the only concept you need to understand to analyze research findings. But it is a very important one. And chances are that understanding the P value will make it easier to understand other key analytical concepts.

Selected references

Burns N, Grove S: The Practice of Nursing Research: Conduct, Critique, and Utilization. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004.

Glaser DN: The controversy of significance testing: misconceptions and alternatives. Am J Crit Care. 1999;8(5):291-296.

Kenneth J. Rempher, PhD, RN, MBA, CCRN, APRN,BC, is Director, Professional Nursing Practice at Sinai Hospital of Baltimore (Md.). Kathleen Urquico, BSN, RN, is a Direct Care Nurse in the Rubin Institute of Advanced Orthopedics at Sinai Hospital of Baltimore.

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

Interpreting statistical significance in nursing research

Introduction to qualitative nursing research

Navigating statistics for successful project implementation

Nurse research and the institutional review board

Research 101: Descriptive statistics

Research 101: Forest plots

Understanding confidence intervals helps you make better clinical decisions

Differentiating statistical significance and clinical significance

Differentiating research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement

Are you confident about confidence intervals?

Making sense of statistical power

The First Step: Ask; Fundamentals of Evidence-Based Nursing Practice

In this module, we will learn about identifying the problem, start the “Ask” process with developing an answerable clinical question, and learn about purpose statements and hypotheses.

Content includes:

- Identifying the problem

- Determining the Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO)

- Asking a Research/Clinical Question (Based on PICO)

Statements of Purpose

Objectives:

- Describe the process of developing a research/practice problem.

- Describe the components of a PICO.

- Identify different types of PICOs.

- Distinguish function and form of statements of purpose.

- Describe the function and characteristics of hypotheses.

Development of a Research/Practice Problem

Practice questions frequently arise from day-to-day problems that are encountered by providers (Dearholt & Dang, 2012). Often, these problems are very obvious. However, sometimes we need to back up and take a close look at the status quo to see underlying issues. The basis for any research project is indeed the underlying problem or issue. A good problem statement or paragraph is a declaration of what it is that is problematic or what it is that we do not know much about (a gap in knowledge) (Polit & Beck, 2018).

The process of defining the practice/clinical problem begins by seeking answers to clinical concerns. This is the first step in the EBP process: To ask . We start by asking some broad questions to help guide the process of developing our practice problem.

- Is there evidence that the current treatment works?

- Does the current practice help the patient?

- Why are we doing the current practice?

- Should we be doing the current practice this way?

- Is there a way to do this current practice more efficiently?

- Is there a more cost-effective method to do this practice?

Problem Statements:

For our EBP Project, we will need to ask these broad questions and then develop our problem that exists. This establishes the “background” of the issue we want to know more about.

For example, if we are choosing a clinical question based on wanting to know if adjunct music therapy helps decrease postoperative pain levels than just pharmaceuticals alone, we might consider the underlying problems of:

- Postoperative pain is not adequately managed in greater than 80% of patients in the US, although rates vary depending on such factors as type of surgery performed, analgesic/anesthetic intervention used, and time elapsed after surgery (Gan, 2017).

- Poorly controlled acute postoperative pain is associated with increased morbidity, functional and quality-of-life impairment, delayed recovery time, prolonged duration of opioid use, and higher health-care costs (Gan, 2017).

- Multimodal analgesic techniques are widely used but new evidence is disappointing (Rawal, 2016).

In the above examples, we are establishing that poorly managed postoperative pain is a problem. Thus, looking at evidence about adjunctive music therapy may help to address how we might manage pain more effectively. These are our problem statements. This would be our introduction section on the EBP poster. For the sake of our EBP poster, you do not need to list these on the poster references. A heads up: The sources used to help develop our research/clinical program should not be the same resources that we use to answer our upcoming clinical question. In essence, we will be conducting two literature reviews: One, to establish the underlying problem; and, two: To find published research that helps to answer our developed clinical question.

Here is the introduction to the article titled, “The relationships among pain, depression, and physical activity in patients with heart failure” (Haedtke et al, 2017). You can read that the underlying problem is multifocal: 67% of patient with heart failure (HF) experience pain, depression is a comorbidity that affects 22% to 42% of HF patients, and that little attention has been paid to this relationship in patients with HF. The researchers have established the need for further research and why further research is needed.

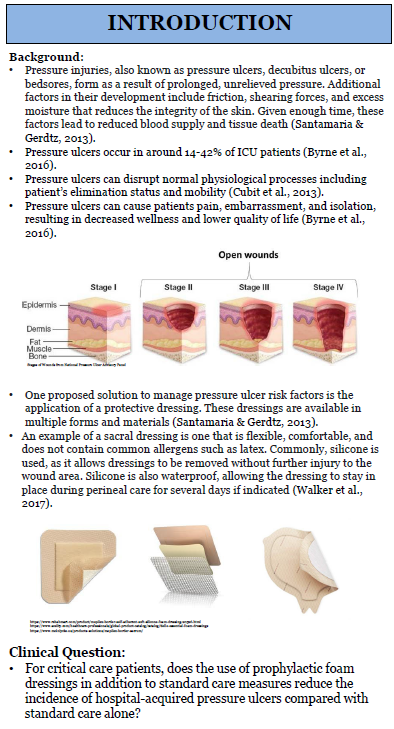

Here is another example of how the clinical problem is addressed in an EBP poster that wants to appraise existing evidence related to dressing choice for decubitus ulcers.

When trying to communicate clinical problems, there are two main sources (Titler et al, 1994, 2001):

- Problem-focused triggers : These are identified by staff during routine monitoring of quality, risk, adverse events, financial, or benchmarking data.

- Knowledge-focused triggers : There are identified through reading published evidence or learning new information at conferences or other professional meetings.

Sources of Evidence-Based Clinical Problems:

Most problem statements have the following components:

- Problem identification: What is wrong with the current situation or action?

- Background: What is the nature of the problem or the context of the situation? (this helps to establish the why)

- Scope of the problem: How many people are affected? Is this a small problem? Big problem? Potential to grow quickly to a large problem? Has been increasing/decreasing recently?

- Consequences of the problem: If we do nothing or leave as the status quo, what is the cost of not fixing the issue?

- Knowledge gaps: What information about the problem is lacking? We need to know what we do not know.

- Proposed solution: How will the information or evidence contribute to the solution of the problem?

If you are stumped on a topic, ask faculty, RNs at local facilities, colleagues, and key stakeholders at local facilities for some ideas! There is usually “something” that the nursing field is concerned about or has questions about.

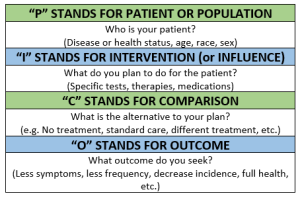

Components of a PICO Question

After we have asked ourselves some background questions, we need to develop a foreground (focused) question. A thoughtful development of a well-structured foreground clinical/practice question is important because the question drives the strategies that you will use to search for the published evidence. The question needs to be very specific, non-ambiguous , and measurable in order to find the relevant evidence needed and also increased the likelihood that you will find what you are looking for.

In developing your clinical/practice question, there is a helpful format to utilize to establish the key component. This format includes the Patient/Population, Intervention/Influence/Exposure, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) (Richardson, Wilson, Nishikawa, & Hayward, 1995).

Let’s dive into each component to better understand.

P atient, population, or problem: We want to describe the patient, the population, or the problem. Get specific. We will want to know exactly who we are wanting to know about. Consider age, gender, setting of the patient (e.g. postoperative), and/or symptoms.

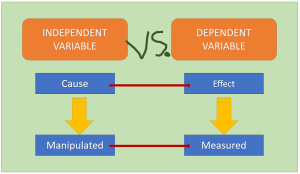

I ntervention: The intervention is the action or, in other words, the treatment, process of care, education given, or assessment approaches. We will come back to this in more depth, but for now remember that the intervention is also called the “Independent Variable”.

C omparison: Here we are comparing with other interventions. A comparison can be standard of care that already exists, current practice, an opposite intervention/action, or a different intervention/action.

O utcome: What is that that we are looking at for a result or consequence of the intervention? The outcome needs to have a metric for actually measuring results. The outcome can include quality of life, patient satisfaction, cost impacts, or treatment results. The outcome is also called the “Dependent Variable”.

The PICO question is a critical aspect of the EBP project to guide the problem identification and create components that can be used to shape the literature search.

Let’s watch a nice YouTube video, “PICO: A Model for Evidence-Based Research”:

“PICO: A Model for Evidence Based Research” by Binghamton University Libraries. Licensed CCY BY .

Great! Okay, let’s move on and discuss the various types of PICOs.

Types of PICOs

Before we start developing our clinical question, let’s go over the various types of PICOs and the clinical question that can result from the components. There are various types of PICOs but we are concerned with the therapy/treatment/intervention format of PICO for our EBP posters.

Let’s take a look at the various types of PICOs:

The first step in developing a research or clinical practice question is developing your PICO. Well, we’ve done that above. You will select each component of your PICO and then turn that into your question. Making the EBP question as specific as possible really helps to identify specific terms and narrow the search, which will result in reducing the time it times searching for relevant evidence.

Once you have your pertinent clinical question, you will use the components to begin your search in published literature for articles that help to answer your question. In class, we will practice with various situations to develop PICOs and clinical questions.

Many articles have the researcher’s statement of purpose (sometimes referred to as “aim”, “goal”, or “objective”) for their research project. This helps to identify what the overarching direction of inquiry may be. You do not need a statement of purpose/aim/goal/objective for your EBP poster. However, knowing what a statement of purpose is will help you when appraising articles to help answer your clinical question.

The following statement of purpose was written as an aim. The population (P) was identified as patients with HF, the interventions (I) included physical activity/exercise, and the outcomes (O) included pain, depression, total activity time, and sitting time as correlated with the interventions.

In the articles above, the authors made it easy and included their statements of purpose within the abstract at the beginning of the article. Most articles do not feature this ease, and you will need to read the introduction or methodology section of the article to find the statement of purpose, much like within article 3.1.

In qualitative studies, the statement of purpose usually indicates the nature of the inquiry, the key concept, the key phenomenon, and the population.

Function and Characteristics of Hypotheses.

A hypothesis (plural: hypothes es ) is a statement of predicted outcome. Meaning, it is an educated and formulated guess as to how the intervention (independent variable – more on that soon!) impacts the outcome (dependent variable). It is not always a cause and effect. Sometimes there can be just a simple association or correlation. We will come back to that in a few modules.

In your PICO statement, you can think of the “I” as the independent variable and the “O” as the dependent variable . Variables will begin making more sense as we go. But for now, remember this:

Independent Variable (IV): This is a measure that can be manipulated by the researcher. Perhaps it is a medication, an educational program, or a survey. The independent variable enacts change (or not) onto the independent variable.

Dependent Variable (DV): This is the result of the independent variable. This is the variable that we utilize statistical analyses to measure. For instance, if we are intervening with a blood pressure medication (our IV), then our DV would be the measurement of the actual blood pressure.

Most of the time, a hypothesis results from a well-worded research question. Here is an example:

Research Question : “Does sexual abuse in childhood affect the development of irritable bowel syndrome in women?”

Research Hypothesis : Women (P) who were sexually abused in childhood (I) have a higher incidence of irritable bowel syndrome (O) than women who were not abused (C).

You may note in that hypothesis that there is a predicted direction of outcome. One thing leads to something.

But, why do we need a hypothesis? First, they help to promote critical thinking. Second, it gives the researcher a way to measure a relationship. Suppose we conducted a study guided only by a research question. Take the above question, for example. Without a hypothesis, the researcher is seemingly prepared to accept any result (Polit & Beck, 2021). The problem with that is that it is almost always possible to explain something superficially after the fact, even if the findings are inconclusive. A hypothesis reduces the possibility that spurious results will be misconstrued (Polit & Beck, 2021).

Not all research articles will list a hypothesis. This makes it more difficult to critically appraise the results. That is not to say that the results would be invalidated, but it should ignite a spirit of further inquiry as to if the results are valid.

Hypotheses (also called alternative hypothesis) can be stated as:

- Directional or nondirectional

- Simple or complex

- Research or Null

Simple hypothesis : Statement of causal (cause and effect) relationship – one independent variable (intervention) and one dependent variable (outcome).

Example : If you stay up late, then you feel tired the next day.

Complex hypothesis : Statement of causal (cause and effect) or associative (not causal) between two or more independent variables (interventions) and/or two or more dependent variables (outcomes).

Example : Higher the poverty, higher the illiteracy in society, higher will be the rate of crime (three variables – two independent variables and one dependent variable).

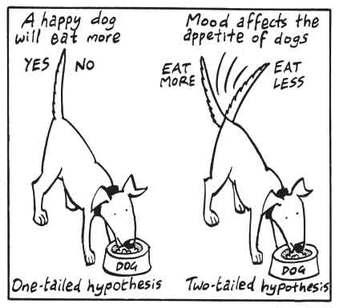

Directional hypothesis : Specifies not only the existence but also the expected direction of the relationship between the dependent (outcome) and the independent (intervention) variables. You will also see this called “One-tailed hypothesis”.

Example : Depression scores will decrease following a 6-week intervention.

Nondirectional hypothesis : Does not specify the direction of relationship between the variables. You will also see this called “Two-tailed hypothesis”.

Example : College students will perform differently from elementary school students on a memory task (without predicting which group of students will perform better).

Null hypothesis : The null hypothesis assumes that any kind of difference between the chosen characteristics that you see in a set of data is due to chance. Now, the null hypothesis is why the plain old hypothesis is also called alternative hypothesis. We don’t just assume that the hypothesis is true. So, it is considered an alternative to something just happening by chance (null).

Example : Let’s say our research question is, “Do teens use cell phones to access the internet more than adults?” – our null hypothesis could state: Age has no effect on how cell phones are used for internet access.

And then, further develop the problem and background through finding existing literature to help answer the following questions:

- Knowledge gaps: What information about the problem is lacking? We need to know what we do not know.

With the previous example of pain in the pediatric population, here is an example of an Introduction section from a past student poster:

- What was the research problem? Was the problem statement easy to locate and was it clearly stated? Did the problem statement build a coherent and persuasive argument for the new study?

- Does the problem have significance for nursing?

- Was there a good fit between the research problem and the paradigm (and tradition) within which the research was conducted?

- Did the report formally present a statement of purpose, research question, and/or hypotheses? Was this information communicated clearly and concisely, and was it placed in a logical and useful location?

- Were purpose statements or research questions worded appropriately (e.g., were key concepts/variables identified and the population specified?

- If there were no formal hypotheses, was their absence justified? Were statistical tests used in analyzing the data despite the absence of stated hypotheses?

- Were hypotheses (if any) properly worded—did they state a predicted relationship between two or more variables? Were they presented as research or as null hypotheses?

References & Attribution

“ Green check mark ” by rawpixel licensed CC0 .

“ Light bulb doodle ” by rawpixel licensed CC0 .

“ Magnifying glass ” by rawpixel licensed CC0

“ Orange flame ” by rawpixel licensed CC0 .

Chen, P., Nunez-Smith, M., Bernheim, S… (2010). Professional experiences of international medical graduates practicing primary care in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25 (9), 947-53.

Dearholt, S.L., & Dang, D. (2012). Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice: Model and guidelines (2nd Ed.). Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International.

Gan, T. (2017). Poorly controlled postoperative pain: Prevalence, consequences, and prevention. Journal of Pain Research, 10, 2287-2298.

Genc, A., Can, G., Aydiner, A. (2012). The efficiency of the acupressure in prevention of the chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Support Care Cancer, 21 , 253-261.

Haedtke, C., Smith, M., VanBuren, J., Kein, D., Turvey, C. (2017). The relationships among pain, depression, and physical activity in patients with heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 32 (5), E21-E25.

Pankong, O., Pothiban, L., Sucamvang, K., Khampolsiri, T. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of enhancing positive aspects of caregiving in Thai dementia caregivers for dementia. Pacific Rim Internal Journal of Nursing Res, 22 (2), 131-143.

Polit, D. & Beck, C. (2021). Lippincott CoursePoint Enhanced for Polit’s Essentials of Nursing Research (10th ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health.

Rawal, N. (2016). Current issues in postoperative pain management. European Journal of Anaesthesiology, 33 , 160-171.

Richardson, W.W., Wilson, M.C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R.S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. American College of Physicians, 123 (3), A12-A13.

Titler, M. G., Kleiber, C., Steelman, V.J. Rakel, B. A. Budreau, G., Everett,…Goode, C.J. (2001). The Iowa model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 13 (4), 497-509.

Evidence-Based Practice & Research Methodologies Copyright © by Tracy Fawns is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 21, Issue 4

- How to appraise quantitative research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

This article has a correction. Please see:

- Correction: How to appraise quantitative research - April 01, 2019

- Xabi Cathala 1 ,

- Calvin Moorley 2

- 1 Institute of Vocational Learning , School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University , London , UK

- 2 Nursing Research and Diversity in Care , School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University , London , UK

- Correspondence to Mr Xabi Cathala, Institute of Vocational Learning, School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University London UK ; cathalax{at}lsbu.ac.uk and Dr Calvin Moorley, Nursing Research and Diversity in Care, School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University, London SE1 0AA, UK; Moorleyc{at}lsbu.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2018-102996

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Some nurses feel that they lack the necessary skills to read a research paper and to then decide if they should implement the findings into their practice. This is particularly the case when considering the results of quantitative research, which often contains the results of statistical testing. However, nurses have a professional responsibility to critique research to improve their practice, care and patient safety. 1 This article provides a step by step guide on how to critically appraise a quantitative paper.

Title, keywords and the authors

The authors’ names may not mean much, but knowing the following will be helpful:

Their position, for example, academic, researcher or healthcare practitioner.

Their qualification, both professional, for example, a nurse or physiotherapist and academic (eg, degree, masters, doctorate).

This can indicate how the research has been conducted and the authors’ competence on the subject. Basically, do you want to read a paper on quantum physics written by a plumber?

The abstract is a resume of the article and should contain:

Introduction.

Research question/hypothesis.

Methods including sample design, tests used and the statistical analysis (of course! Remember we love numbers).

Main findings.

Conclusion.

The subheadings in the abstract will vary depending on the journal. An abstract should not usually be more than 300 words but this varies depending on specific journal requirements. If the above information is contained in the abstract, it can give you an idea about whether the study is relevant to your area of practice. However, before deciding if the results of a research paper are relevant to your practice, it is important to review the overall quality of the article. This can only be done by reading and critically appraising the entire article.

The introduction

Example: the effect of paracetamol on levels of pain.

My hypothesis is that A has an effect on B, for example, paracetamol has an effect on levels of pain.

My null hypothesis is that A has no effect on B, for example, paracetamol has no effect on pain.

My study will test the null hypothesis and if the null hypothesis is validated then the hypothesis is false (A has no effect on B). This means paracetamol has no effect on the level of pain. If the null hypothesis is rejected then the hypothesis is true (A has an effect on B). This means that paracetamol has an effect on the level of pain.

Background/literature review

The literature review should include reference to recent and relevant research in the area. It should summarise what is already known about the topic and why the research study is needed and state what the study will contribute to new knowledge. 5 The literature review should be up to date, usually 5–8 years, but it will depend on the topic and sometimes it is acceptable to include older (seminal) studies.

Methodology

In quantitative studies, the data analysis varies between studies depending on the type of design used. For example, descriptive, correlative or experimental studies all vary. A descriptive study will describe the pattern of a topic related to one or more variable. 6 A correlational study examines the link (correlation) between two variables 7 and focuses on how a variable will react to a change of another variable. In experimental studies, the researchers manipulate variables looking at outcomes 8 and the sample is commonly assigned into different groups (known as randomisation) to determine the effect (causal) of a condition (independent variable) on a certain outcome. This is a common method used in clinical trials.

There should be sufficient detail provided in the methods section for you to replicate the study (should you want to). To enable you to do this, the following sections are normally included:

Overview and rationale for the methodology.

Participants or sample.

Data collection tools.

Methods of data analysis.

Ethical issues.

Data collection should be clearly explained and the article should discuss how this process was undertaken. Data collection should be systematic, objective, precise, repeatable, valid and reliable. Any tool (eg, a questionnaire) used for data collection should have been piloted (or pretested and/or adjusted) to ensure the quality, validity and reliability of the tool. 9 The participants (the sample) and any randomisation technique used should be identified. The sample size is central in quantitative research, as the findings should be able to be generalised for the wider population. 10 The data analysis can be done manually or more complex analyses performed using computer software sometimes with advice of a statistician. From this analysis, results like mode, mean, median, p value, CI and so on are always presented in a numerical format.

The author(s) should present the results clearly. These may be presented in graphs, charts or tables alongside some text. You should perform your own critique of the data analysis process; just because a paper has been published, it does not mean it is perfect. Your findings may be different from the author’s. Through critical analysis the reader may find an error in the study process that authors have not seen or highlighted. These errors can change the study result or change a study you thought was strong to weak. To help you critique a quantitative research paper, some guidance on understanding statistical terminology is provided in table 1 .

- View inline

Some basic guidance for understanding statistics

Quantitative studies examine the relationship between variables, and the p value illustrates this objectively. 11 If the p value is less than 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected and the hypothesis is accepted and the study will say there is a significant difference. If the p value is more than 0.05, the null hypothesis is accepted then the hypothesis is rejected. The study will say there is no significant difference. As a general rule, a p value of less than 0.05 means, the hypothesis is accepted and if it is more than 0.05 the hypothesis is rejected.

The CI is a number between 0 and 1 or is written as a per cent, demonstrating the level of confidence the reader can have in the result. 12 The CI is calculated by subtracting the p value to 1 (1–p). If there is a p value of 0.05, the CI will be 1–0.05=0.95=95%. A CI over 95% means, we can be confident the result is statistically significant. A CI below 95% means, the result is not statistically significant. The p values and CI highlight the confidence and robustness of a result.

Discussion, recommendations and conclusion

The final section of the paper is where the authors discuss their results and link them to other literature in the area (some of which may have been included in the literature review at the start of the paper). This reminds the reader of what is already known, what the study has found and what new information it adds. The discussion should demonstrate how the authors interpreted their results and how they contribute to new knowledge in the area. Implications for practice and future research should also be highlighted in this section of the paper.

A few other areas you may find helpful are:

Limitations of the study.

Conflicts of interest.

Table 2 provides a useful tool to help you apply the learning in this paper to the critiquing of quantitative research papers.

Quantitative paper appraisal checklist

- 1. ↵ Nursing and Midwifery Council , 2015 . The code: standard of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/nmc-code.pdf ( accessed 21.8.18 ).

- Gerrish K ,

- Moorley C ,

- Tunariu A , et al

- Shorten A ,

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Correction notice This article has been updated since its original publication to update p values from 0.5 to 0.05 throughout.

Linked Articles

- Miscellaneous Correction: How to appraise quantitative research BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and RCN Publishing Company Ltd Evidence-Based Nursing 2019; 22 62-62 Published Online First: 31 Jan 2019. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102996corr1

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Physician Physician Board Reviews Physician Associate Board Reviews CME Lifetime CME Free CME

- Student USMLE Step 1 USMLE Step 2 USMLE Step 3 COMLEX Level 1 COMLEX Level 2 COMLEX Level 3 96 Medical School Exams Student Resource Center NCLEX - RN NCLEX - LPN/LVN/PN 24 Nursing Exams

- Nurse Practitioner APRN/NP Board Reviews CNS Certification Reviews CE - Nurse Practitioner FREE CE

- Nurse RN Certification Reviews CE - Nurse FREE CE

- Pharmacist Pharmacy Board Exam Prep CE - Pharmacist

- Allied Allied Health Exam Prep Dentist Exams CE - Social Worker CE - Dentist

- Point of Care

- Free CME/CE

Hypothesis Testing, P Values, Confidence Intervals, and Significance

Definition/introduction.

Medical providers often rely on evidence-based medicine to guide decision-making in practice. Often a research hypothesis is tested with results provided, typically with p values, confidence intervals, or both. Additionally, statistical or research significance is estimated or determined by the investigators. Unfortunately, healthcare providers may have different comfort levels in interpreting these findings, which may affect the adequate application of the data.

Issues of Concern

Register for free and read the full article, learn more about a subscription to statpearls point-of-care.

Without a foundational understanding of hypothesis testing, p values, confidence intervals, and the difference between statistical and clinical significance, it may affect healthcare providers' ability to make clinical decisions without relying purely on the research investigators deemed level of significance. Therefore, an overview of these concepts is provided to allow medical professionals to use their expertise to determine if results are reported sufficiently and if the study outcomes are clinically appropriate to be applied in healthcare practice.

Hypothesis Testing

Investigators conducting studies need research questions and hypotheses to guide analyses. Starting with broad research questions (RQs), investigators then identify a gap in current clinical practice or research. Any research problem or statement is grounded in a better understanding of relationships between two or more variables. For this article, we will use the following research question example:

Research Question: Is Drug 23 an effective treatment for Disease A?

Research questions do not directly imply specific guesses or predictions; we must formulate research hypotheses. A hypothesis is a predetermined declaration regarding the research question in which the investigator(s) makes a precise, educated guess about a study outcome. This is sometimes called the alternative hypothesis and ultimately allows the researcher to take a stance based on experience or insight from medical literature. An example of a hypothesis is below.

Research Hypothesis: Drug 23 will significantly reduce symptoms associated with Disease A compared to Drug 22.

The null hypothesis states that there is no statistical difference between groups based on the stated research hypothesis.

Researchers should be aware of journal recommendations when considering how to report p values, and manuscripts should remain internally consistent.

Regarding p values, as the number of individuals enrolled in a study (the sample size) increases, the likelihood of finding a statistically significant effect increases. With very large sample sizes, the p-value can be very low significant differences in the reduction of symptoms for Disease A between Drug 23 and Drug 22. The null hypothesis is deemed true until a study presents significant data to support rejecting the null hypothesis. Based on the results, the investigators will either reject the null hypothesis (if they found significant differences or associations) or fail to reject the null hypothesis (they could not provide proof that there were significant differences or associations).

To test a hypothesis, researchers obtain data on a representative sample to determine whether to reject or fail to reject a null hypothesis. In most research studies, it is not feasible to obtain data for an entire population. Using a sampling procedure allows for statistical inference, though this involves a certain possibility of error. [1] When determining whether to reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis, mistakes can be made: Type I and Type II errors. Though it is impossible to ensure that these errors have not occurred, researchers should limit the possibilities of these faults. [2]

Significance

Significance is a term to describe the substantive importance of medical research. Statistical significance is the likelihood of results due to chance. [3] Healthcare providers should always delineate statistical significance from clinical significance, a common error when reviewing biomedical research. [4] When conceptualizing findings reported as either significant or not significant, healthcare providers should not simply accept researchers' results or conclusions without considering the clinical significance. Healthcare professionals should consider the clinical importance of findings and understand both p values and confidence intervals so they do not have to rely on the researchers to determine the level of significance. [5] One criterion often used to determine statistical significance is the utilization of p values.

P values are used in research to determine whether the sample estimate is significantly different from a hypothesized value. The p-value is the probability that the observed effect within the study would have occurred by chance if, in reality, there was no true effect. Conventionally, data yielding a p<0.05 or p<0.01 is considered statistically significant. While some have debated that the 0.05 level should be lowered, it is still universally practiced. [6] Hypothesis testing allows us to determine the size of the effect.

An example of findings reported with p values are below:

Statement: Drug 23 reduced patients' symptoms compared to Drug 22. Patients who received Drug 23 (n=100) were 2.1 times less likely than patients who received Drug 22 (n = 100) to experience symptoms of Disease A, p<0.05.

Statement:Individuals who were prescribed Drug 23 experienced fewer symptoms (M = 1.3, SD = 0.7) compared to individuals who were prescribed Drug 22 (M = 5.3, SD = 1.9). This finding was statistically significant, p= 0.02.

For either statement, if the threshold had been set at 0.05, the null hypothesis (that there was no relationship) should be rejected, and we should conclude significant differences. Noticeably, as can be seen in the two statements above, some researchers will report findings with < or > and others will provide an exact p-value (0.000001) but never zero [6] . When examining research, readers should understand how p values are reported. The best practice is to report all p values for all variables within a study design, rather than only providing p values for variables with significant findings. [7] The inclusion of all p values provides evidence for study validity and limits suspicion for selective reporting/data mining.

While researchers have historically used p values, experts who find p values problematic encourage the use of confidence intervals. [8] . P-values alone do not allow us to understand the size or the extent of the differences or associations. [3] In March 2016, the American Statistical Association (ASA) released a statement on p values, noting that scientific decision-making and conclusions should not be based on a fixed p-value threshold (e.g., 0.05). They recommend focusing on the significance of results in the context of study design, quality of measurements, and validity of data. Ultimately, the ASA statement noted that in isolation, a p-value does not provide strong evidence. [9]

When conceptualizing clinical work, healthcare professionals should consider p values with a concurrent appraisal study design validity. For example, a p-value from a double-blinded randomized clinical trial (designed to minimize bias) should be weighted higher than one from a retrospective observational study [7] . The p-value debate has smoldered since the 1950s [10] , and replacement with confidence intervals has been suggested since the 1980s. [11]

Confidence Intervals

A confidence interval provides a range of values within given confidence (e.g., 95%), including the accurate value of the statistical constraint within a targeted population. [12] Most research uses a 95% CI, but investigators can set any level (e.g., 90% CI, 99% CI). [13] A CI provides a range with the lower bound and upper bound limits of a difference or association that would be plausible for a population. [14] Therefore, a CI of 95% indicates that if a study were to be carried out 100 times, the range would contain the true value in 95, [15] confidence intervals provide more evidence regarding the precision of an estimate compared to p-values. [6]

In consideration of the similar research example provided above, one could make the following statement with 95% CI:

Statement: Individuals who were prescribed Drug 23 had no symptoms after three days, which was significantly faster than those prescribed Drug 22; there was a mean difference between the two groups of days to the recovery of 4.2 days (95% CI: 1.9 – 7.8).

It is important to note that the width of the CI is affected by the standard error and the sample size; reducing a study sample number will result in less precision of the CI (increase the width). [14] A larger width indicates a smaller sample size or a larger variability. [16] A researcher would want to increase the precision of the CI. For example, a 95% CI of 1.43 – 1.47 is much more precise than the one provided in the example above. In research and clinical practice, CIs provide valuable information on whether the interval includes or excludes any clinically significant values. [14]

Null values are sometimes used for differences with CI (zero for differential comparisons and 1 for ratios). However, CIs provide more information than that. [15] Consider this example: A hospital implements a new protocol that reduced wait time for patients in the emergency department by an average of 25 minutes (95% CI: -2.5 – 41 minutes). Because the range crosses zero, implementing this protocol in different populations could result in longer wait times; however, the range is much higher on the positive side. Thus, while the p-value used to detect statistical significance for this may result in "not significant" findings, individuals should examine this range, consider the study design, and weigh whether or not it is still worth piloting in their workplace.

Similarly to p-values, 95% CIs cannot control for researchers' errors (e.g., study bias or improper data analysis). [14] In consideration of whether to report p-values or CIs, researchers should examine journal preferences. When in doubt, reporting both may be beneficial. [13] An example is below:

Reporting both: Individuals who were prescribed Drug 23 had no symptoms after three days, which was significantly faster than those prescribed Drug 22, p = 0.009. There was a mean difference between the two groups of days to the recovery of 4.2 days (95% CI: 1.9 – 7.8).

Clinical Significance

Recall that clinical significance and statistical significance are two different concepts. Healthcare providers should remember that a study with statistically significant differences and large sample size may be of no interest to clinicians, whereas a study with smaller sample size and statistically non-significant results could impact clinical practice. [14] Additionally, as previously mentioned, a non-significant finding may reflect the study design itself rather than relationships between variables.

Healthcare providers using evidence-based medicine to inform practice should use clinical judgment to determine the practical importance of studies through careful evaluation of the design, sample size, power, likelihood of type I and type II errors, data analysis, and reporting of statistical findings (p values, 95% CI or both). [4] Interestingly, some experts have called for "statistically significant" or "not significant" to be excluded from work as statistical significance never has and will never be equivalent to clinical significance. [17]

The decision on what is clinically significant can be challenging, depending on the providers' experience and especially the severity of the disease. Providers should use their knowledge and experiences to determine the meaningfulness of study results and make inferences based not only on significant or insignificant results by researchers but through their understanding of study limitations and practical implications.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

All physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals should strive to understand the concepts in this chapter. These individuals should maintain the ability to review and incorporate new literature for evidence-based and safe care.

Jones M, Gebski V, Onslow M, Packman A. Statistical power in stuttering research: a tutorial. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research : JSLHR. 2002 Apr:45(2):243-55 [PubMed PMID: 12003508]

Sedgwick P. Pitfalls of statistical hypothesis testing: type I and type II errors. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2014 Jul 3:349():g4287. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4287. Epub 2014 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 24994622]

Fethney J. Statistical and clinical significance, and how to use confidence intervals to help interpret both. Australian critical care : official journal of the Confederation of Australian Critical Care Nurses. 2010 May:23(2):93-7. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2010.03.001. Epub 2010 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 20347326]

Hayat MJ. Understanding statistical significance. Nursing research. 2010 May-Jun:59(3):219-23. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181dbb2cc. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20445438]

Ferrill MJ, Brown DA, Kyle JA. Clinical versus statistical significance: interpreting P values and confidence intervals related to measures of association to guide decision making. Journal of pharmacy practice. 2010 Aug:23(4):344-51. doi: 10.1177/0897190009358774. Epub 2010 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 21507834]

Infanger D, Schmidt-Trucksäss A. P value functions: An underused method to present research results and to promote quantitative reasoning. Statistics in medicine. 2019 Sep 20:38(21):4189-4197. doi: 10.1002/sim.8293. Epub 2019 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 31270842]

Dorey F. Statistics in brief: Interpretation and use of p values: all p values are not equal. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2011 Nov:469(11):3259-61. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2053-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21918804]

Liu XS. Implications of statistical power for confidence intervals. The British journal of mathematical and statistical psychology. 2012 Nov:65(3):427-37. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.2011.02035.x. Epub 2011 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 22026811]

Tijssen JG, Kolm P. Demystifying the New Statistical Recommendations: The Use and Reporting of p Values. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016 Jul 12:68(2):231-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.026. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27386779]

Spanos A. Recurring controversies about P values and confidence intervals revisited. Ecology. 2014 Mar:95(3):645-51 [PubMed PMID: 24804448]

Freire APCF, Elkins MR, Ramos EMC, Moseley AM. Use of 95% confidence intervals in the reporting of between-group differences in randomized controlled trials: analysis of a representative sample of 200 physical therapy trials. Brazilian journal of physical therapy. 2019 Jul-Aug:23(4):302-310. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2018.10.004. Epub 2018 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 30366845]

Dorey FJ. In brief: statistics in brief: Confidence intervals: what is the real result in the target population? Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2010 Nov:468(11):3137-8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1407-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20532716]

Porcher R. Reporting results of orthopaedic research: confidence intervals and p values. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2009 Oct:467(10):2736-7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0952-1. Epub 2009 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 19565303]

Gardner MJ, Altman DG. Confidence intervals rather than P values: estimation rather than hypothesis testing. British medical journal (Clinical research ed.). 1986 Mar 15:292(6522):746-50 [PubMed PMID: 3082422]

Cooper RJ, Wears RL, Schriger DL. Reporting research results: recommendations for improving communication. Annals of emergency medicine. 2003 Apr:41(4):561-4 [PubMed PMID: 12658257]

Doll H, Carney S. Statistical approaches to uncertainty: P values and confidence intervals unpacked. Equine veterinary journal. 2007 May:39(3):275-6 [PubMed PMID: 17520981]

Colquhoun D. The reproducibility of research and the misinterpretation of p-values. Royal Society open science. 2017 Dec:4(12):171085. doi: 10.1098/rsos.171085. Epub 2017 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 29308247]

Use the mouse wheel to zoom in and out, click and drag to pan the image

Nursing Research

- First Online: 24 January 2019

Cite this chapter

- Lars-Petter Jelsness-Jørgensen 3 , 4

1631 Accesses

Nurses play an increasingly active role in clinical research in IBD. By reviewing existing literature on the topic, this chapter provides a brief overview of some main concepts related to research in nursing. In addition, the chapter provides some general advice in relation to implementing evidence-based practice, as well as carrying out independent research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Abrandt Dahlgren M, Higgs J, Richardson B (2004) Developing practice knowledge for health professionals. Butterworth-Heinemann, Edinburgh

Google Scholar

Bager P, Befrits R, Wikman O, Lindgren S, Moum B, Hjortswang H et al (2011) The prevalence of anemia and iron deficiency in IBD outpatients in Scandinavia. Scand J Gastroenterol 46(3):304–309

Article Google Scholar

Bager P, Befrits R, Wikman O, Lindgren S, Moum B, Hjortswang H et al (2012) Fatigue in out-patients with inflammatory bowel disease is common and multifactorial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 35(1):133–141

Article CAS Google Scholar

Coenen S, Weyts E, Vermeire S, Ferrante M, Noman M, Ballet V et al (2017) Effects of introduction of an inflammatory bowel disease nurse position on the quality of delivered care. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 29(6):646–650

Czuber-Dochan W, Ream E, Norton C (2013a) Review article: description and management of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 37(5):505–516

Czuber-Dochan W, Dibley LB, Terry H, Ream E, Norton C (2013b) The experience of fatigue in people with inflammatory bowel disease: an exploratory study. J Adv Nurs 69(9):1987–1999

Czuber-Dochan W, Norton C, Bassett P, Berliner S, Bredin F, Darvell M et al (2014a) Development and psychometric testing of inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) patient self-assessment scale. J Crohns Colitis 8(11):1398–1406

Czuber-Dochan W, Norton C, Bredin F, Darvell M, Nathan I, Terry H (2014b) Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of fatigue experienced by people with IBD. J Crohns Colitis 8(8):835–844

Dibley L, Norton C (2013) Experiences of fecal incontinence in people with inflammatory bowel disease: self-reported experiences among a community sample. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19(7):1450–1462

Dibley L, Bager P, Czuber-Dochan W, Farrell D, Jelsness-Jorgensen LP, Kemp K et al (2017) Identification of research priorities for inflammatory bowel disease nursing in Europe: a Nurses-European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation Delphi Survey. J Crohns Colitis 11(3):353–359

PubMed Google Scholar

Dicenso A, Bayley L, Haynes RB (2009) Accessing pre-appraised evidence: fine-tuning the 5S model into a 6S model. Evid Based Nurs 12(4):99–101

Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, Wang Z, Nabhan M, Shippee N et al (2014) Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 14:89

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Thompson R (2016) Shared decision making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Book Google Scholar

Jaghult S, Larson J, Wredling R, Kapraali M (2007) A multiprofessional education programme for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol 42(12):1452–1459

Jaghult S, Saboonchi F, Johansson UB, Wredling R, Kapraali M (2011) Identifying predictors of low health-related quality of life among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: comparison between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis with disease duration. J Clin Nurs 20(11–12):1578–1587