- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

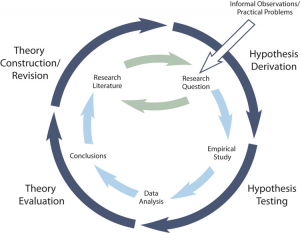

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

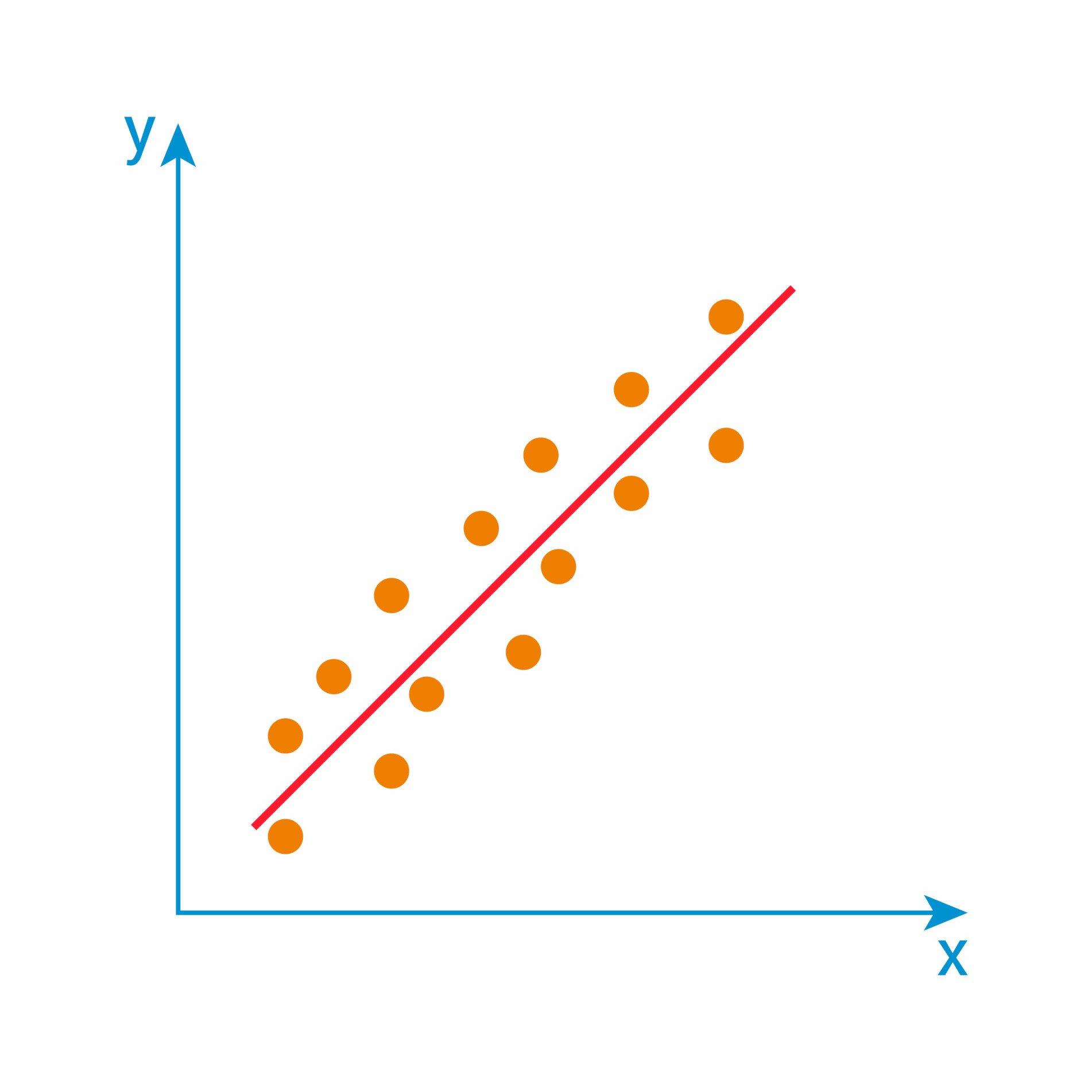

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

6 Hypothesis Examples in Psychology

The hypothesis is one of the most important steps of psychological research. Hypothesis refers to an assumption or the temporary statement made by the researcher before the execution of the experiment, regarding the possible outcome of that experiment. A hypothesis can be tested through various scientific and statistical tools. It is a logical guess based on previous knowledge and investigations related to the problem under investigation. In this article, we’ll learn about the significance of the hypothesis, the sources of the hypothesis, and the various examples of the hypothesis.

Sources of Hypothesis

The formulation of a good hypothesis is not an easy task. One needs to take care of the various crucial steps to get an accurate hypothesis. The hypothesis formulation demands both the creativity of the researcher and his/her years of experience. The researcher needs to use critical thinking to avoid committing any errors such as choosing the wrong hypothesis. Although the hypothesis is considered the first step before further investigations such as data collection for the experiment, the hypothesis formulation also requires some amount of data collection. The data collection for the hypothesis formulation refers to the review of literature related to the concerned topic, and understanding of the previous research on the related topic. Following are some of the main sources of the hypothesis that may help the researcher to formulate a good hypothesis.

- Reviewing the similar studies and literature related to a similar problem.

- Examining the available data concerned with the problem.

- Discussing the problem with the colleagues, or the professional researchers about the problem under investigation.

- Thorough research and investigation by conducting field interviews or surveys on the people that are directly concerned with the problem under investigation.

- Sometimes ‘institution’ of the well known and experienced researcher is also considered as a good source of the hypothesis formulation.

Real Life Hypothesis Examples

1. null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis examples.

Every research problem-solving procedure begins with the formulation of the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis. The alternative hypothesis assumes the existence of the relationship between the variables under study, while the null hypothesis denies the relationship between the variables under study. Following are examples of the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis based on the research problem.

Research Problem: What is the benefit of eating an apple daily on your health?

Alternative Hypothesis: Eating an apple daily reduces the chances of visiting the doctor.

Null Hypothesis : Eating an apple daily does not impact the frequency of visiting the doctor.

Research Problem: What is the impact of spending a lot of time on mobiles on the attention span of teenagers.

Alternative Problem: Spending time on the mobiles and attention span have a negative correlation.

Null Hypothesis: There does not exist any correlation between the use of mobile by teenagers on their attention span.

Research Problem: What is the impact of providing flexible working hours to the employees on the job satisfaction level.

Alternative Hypothesis : Employees who get the option of flexible working hours have better job satisfaction than the employees who don’t get the option of flexible working hours.

Null Hypothesis: There is no association between providing flexible working hours and job satisfaction.

2. Simple Hypothesis Examples

The hypothesis that includes only one independent variable (predictor variable) and one dependent variable (outcome variable) is termed the simple hypothesis. For example, the children are more likely to get clinical depression if their parents had also suffered from the clinical depression. Here, the independent variable is the parents suffering from clinical depression and the dependent or the outcome variable is the clinical depression observed in their child/children. Other examples of the simple hypothesis are given below,

- If the management provides the official snack breaks to the employees, the employees are less likely to take the off-site breaks. Here, providing snack breaks is the independent variable and the employees are less likely to take the off-site break is the dependent variable.

3. Complex Hypothesis Examples

If the hypothesis includes more than one independent (predictor variable) or more than one dependent variable (outcome variable) it is known as the complex hypothesis. For example, clinical depression in children is associated with a family clinical depression history and a stressful and hectic lifestyle. In this case, there are two independent variables, i.e., family history of clinical depression and hectic and stressful lifestyle, and one dependent variable, i.e., clinical depression. Following are some more examples of the complex hypothesis,

4. Logical Hypothesis Examples

If there are not many pieces of evidence and studies related to the concerned problem, then the researcher can take the help of the general logic to formulate the hypothesis. The logical hypothesis is proved true through various logic. For example, if the researcher wants to prove that the animal needs water for its survival, then this can be logically verified through the logic that ‘living beings can not survive without the water.’ Following are some more examples of logical hypotheses,

- Tia is not good at maths, hence she will not choose the accounting sector as her career.

- If there is a correlation between skin cancer and ultraviolet rays, then the people who are more exposed to the ultraviolet rays are more prone to skin cancer.

- The beings belonging to the different planets can not breathe in the earth’s atmosphere.

- The creatures living in the sea use anaerobic respiration as those living outside the sea use aerobic respiration.

5. Empirical Hypothesis Examples

The empirical hypothesis comes into existence when the statement is being tested by conducting various experiments. This hypothesis is not just an idea or notion, instead, it refers to the statement that undergoes various trials and errors, and various extraneous variables can impact the result. The trials and errors provide a set of results that can be testable over time. Following are the examples of the empirical hypothesis,

- The hungry cat will quickly reach the endpoint through the maze, if food is placed at the endpoint then the cat is not hungry.

- The people who consume vitamin c have more glowing skin than the people who consume vitamin E.

- Hair growth is faster after the consumption of Vitamin E than vitamin K.

- Plants will grow faster with fertilizer X than with fertilizer Y.

6. Statistical Hypothesis Examples

The statements that can be proven true by using the various statistical tools are considered the statistical hypothesis. The researcher uses statistical data about an area or the group in the analysis of the statistical hypothesis. For example, if you study the IQ level of the women belonging to nation X, it would be practically impossible to measure the IQ level of each woman belonging to nation X. Here, statistical methods come to the rescue. The researcher can choose the sample population, i.e., women belonging to the different states or provinces of the nation X, and conduct the statistical tests on this sample population to get the average IQ of the women belonging to the nation X. Following are the examples of the statistical hypothesis.

- 30 per cent of the women belonging to the nation X are working.

- 50 per cent of the people living in the savannah are above the age of 70 years.

- 45 per cent of the poor people in the United States are uneducated.

Significance of Hypothesis

A hypothesis is very crucial in experimental research as it aims to predict any particular outcome of the experiment. Hypothesis plays an important role in guiding the researchers to focus on the concerned area of research only. However, the hypothesis is not required by all researchers. The type of research that seeks for finding facts, i.e., historical research, does not need the formulation of the hypothesis. In the historical research, the researchers look for the pieces of evidence related to the human life, the history of a particular area, or the occurrence of any event, this means that the researcher does not have a strong basis to make an assumption in these types of researches, hence hypothesis is not needed in this case. As stated by Hillway (1964)

When fact-finding alone is the aim of the study, a hypothesis is not required.”

The hypothesis may not be an important part of the descriptive or historical studies, but it is a crucial part for the experimental researchers. Following are some of the points that show the importance of formulating a hypothesis before conducting the experiment.

- Hypothesis provides a tentative statement about the outcome of the experiment that can be validated and tested. It helps the researcher to directly focus on the problem under investigation by collecting the relevant data according to the variables mentioned in the hypothesis.

- Hypothesis facilitates a direction to the experimental research. It helps the researcher in analysing what is relevant for the study and what’s not. It prevents the researcher’s time as he does not need to waste time on reviewing the irrelevant research and literature, and also prevents the researcher from collecting the irrelevant data.

- Hypothesis helps the researcher in choosing the appropriate sample, statistical tests to conduct, variables to be studied and the research methodology. The hypothesis also helps the study from being generalised as it focuses on the limited and exact problem under investigation.

- Hypothesis act as a framework for deducing the outcomes of the experiment. The researcher can easily test the different hypotheses for understanding the interaction among the various variables involved in the study. On this basis of the results obtained from the testing of various hypotheses, the researcher can formulate the final meaningful report.

Related Posts

Spearman’s Two-factor Theory of Intelligence Explained

Convergent Thinking Examples

Correlation Examples in Real Life

Overconfidence Bias Examples

Epiphany Examples in Real Life

Psychology and Other Disciplines

Add comment cancel reply.

Find Study Materials for

- Explanations

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Social Studies

- Browse all subjects

- Read our Magazine

Create Study Materials

- Flashcards Create and find the best flashcards.

- Notes Create notes faster than ever before.

- Study Sets Everything you need for your studies in one place.

- Study Plans Stop procrastinating with our smart planner features.

- Aims and Hypotheses

There is no research without a proper aim and hypotheses – aims and hypotheses in research are the supporting frameworks on a path to new scientific discoveries. To better understand their importance, let us first analyse the difference between aims and hypotheses in psychology , examine their purpose, and give some examples.

Create learning materials about Aims and Hypotheses with our free learning app!

- Instand access to millions of learning materials

- Flashcards, notes, mock-exams and more

- Everything you need to ace your exams

- Approaches in Psychology

- Basic Psychology

- Biological Bases of Behavior

- Biopsychology

- Careers in Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognition and Development

- Cognitive Psychology

- Data Handling and Analysis

- Developmental Psychology

- Eating Behaviour

- Emotion and Motivation

- Famous Psychologists

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- Individual Differences Psychology

- Issues and Debates in Psychology

- Personality in Psychology

- Psychological Treatment

- Relationships

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Causation in Psychology

- Coding Frame Psychology

- Correlational Studies

- Cross Cultural Research

- Cross Sectional Research

- Ethical Issues and Ways of Dealing with Them

- Experimental Designs

- Features of Science

- Field Experiment

- Independent Group Design

- Lab Experiment

- Longitudinal Research

- Matched Pairs Design

- Meta Analysis

- Natural Experiment

- Observational Design

- Online Research

- Paradigms and Falsifiability

- Peer Review and Economic Applications of Research

- Pilot Studies and the Aims of Piloting

- Quality Criteria

- Questionnaire Construction

- Repeated Measures Design

- Research Methods

- Sampling Frames

- Sampling Psychology

- Scientific Processes

- Scientific Report

- Scientific Research

- Self-Report Design

- Self-Report Techniques

- Semantic Differential Rating Scale

- Snowball Sampling

- Schizophrenia

- Scientific Foundations of Psychology

- Scientific Investigation

- Sensation and Perception

- Social Context of Behaviour

- Social Psychology

First, we will define the aims and hypotheses and learn the difference between aims and hypotheses in psychology .

Then, we will look at different types of hypotheses.

Next, we will look at the function of aims and hypotheses in research and psychology.

Later, we will look at specific aims and hypotheses in research examples.

Finally, we will discuss the need and how explicit research aims objectives and hypotheses are implemented.

Difference Between Aims and Hypotheses: Psychology

When you write a research report, you should state the aim first and then the hypothesis.

The aim is a summary of the goal or purpose of the research.

The aim is a broad starting point that gets narrowed down into the hypothesis.

- The hypothesis is a predictive, testable statement about what the researcher expects to find in the study.

Types of Hypotheses

Before we get into the types of hypotheses, let's quickly recap the hypotheses' components.

The independent variable (IV) is the factor that the researcher manipulates/ changes (this can be naturally occurring in some instances) and is theorised to be the cause of a phenomenon.

And the dependent variable (DV) is the factor that the researcher measures because they believe that the changes in the IV will affect the DV.

There are two types of hypotheses: null and alternative hypotheses.

A null hypothesis states that the independent variable does not influence the dependent variable. The null hypothesis states that changes/ manipulating the IV will not affect the DV.

Research scenario: Investigation of how test results affect sleep.

An example of a null hypothesis is there is no difference in recorded sleep time (dependent variable) between students who received good and poor grades (independent variable).

An alternative hypothesis states that the independent variable has an effect on the dependent variable. Often, it is the same (or very similar) to your research hypothesis.

Research scenario: Investigating how sleep deprivation affects performance on cognitive tests.

An alternative hypothesis may be that the less sleep students get (independent variable), the worse their performance will be on cognitive tests (dependent variable). Not sleep-deprived students will perform better on the Mini-Mental Status Examination test than sleep-deprived students.

The alternative hypothesis can be further sub-categorised into a one- or two-tailed hypothesis. A one-tailed hypothesis (also known as a directional hypothesis) suggests that the results can go one way, e.g. it may increase or decrease. And a two-tailed (also known as a non-directional hypothesis) is exactly the opposite; there are two ways the results could expectedly go.

An example of a two-tailed hypothesis is if you flip a coin, you could predict that it will land on either heads or tails.

Aims and Hypothesis in Research

In research, aims and hypotheses play major roles. They are the part of the research that sets you up for the rest of the study. Without strong research aims and hypotheses, your research will lack direction.

First, let's go over the function of research aims.

Research aims provide an overview of the research objective; this allows all researchers to be on the same page about the purpose of the research. Aims also describe why the research is needed and how it complements existing research in the field.

Duplicating research can sometimes be useful, but most times, researchers want to conduct their own new research.

Outside of the researchers, readers can then identify the research topic and whether it interests them.

The research aimed to examine the effects of sleep deprivation on test performance.

But what information do hypotheses provide?

Hypotheses identify the variables studied in an experiment. They describe expected results in terms of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. When readers see the hypothesis, they should know exactly what the researcher expected in the study's outcome (remember, sometimes the researcher can be wrong).

The hypothesis was that the less sleep a student gets (independent variable), the worse grades a student will achieve (dependent variable).

Typically, researchers use hypotheses for statistical tests such as hypothesis testing, which allows them to determine if the original predictions are correct. Hypotheses are helpful because the reader can quickly identify the variables , the expected results based on previous research, and how the experiment should measure these variables .

Hypotheses usually influence the research design and analysis used in conducting the research.

Psychological research must meet a standard for the psychological research community to accept it.

Components of Hypotheses

When writing research hypotheses, there are several essential things to consider, including:

The hypotheses must be clear and concise;

it must be easy to understand and not contain irrelevant details.

The researcher must predict what they expect to find based on reading previous research findings.

The researcher must explain how they arrived at their predictions, citing evidence from prior research.

The researcher must identify all variables they will study.

One study examined how sleep deprivation affects performance on cognitive tests. The hypothesis was to identify sleeping time as the independent variable and cognitive test scores as the dependent variable.

Additionally, the research must operationalise the hypotheses and describe how the variables will be measured.

When assessing cognitive abilities, the researcher should indicate how they will assess the cognitive skills. They could do so with a cognitive test, such as the Mini-Mental Status Examination scores.

Example Hypothesis

A hypothesis denotes a relationship between two variables, the independent and dependent variables. An example hypothesis is the more you sleep, the less tired you will feel.

Aims and Hypotheses: Psychology

Now that we understand the difference between aims and hypotheses, let's take a closer look at their function.

In psychology, aims and hypotheses function very similarly to other research fields. They set up the purpose of a study so that the researchers and readers understand its goals.

The aims establish the reasoning behind the study and why that specific topic is being researched. And the hypotheses share the researchers' expectations. It outlines what the researchers expect when the IV is manipulated.

Studies with well-defined aims and hypotheses allow the research to be more accessible. This means that a professional psychologist, a psychology student, or even someone who is simply curious about the topic can all read the research and understand its purpose.

Aims and Hypotheses in Research Example

As we have learned, aims and hypotheses are crucial in setting up successful research. They exist within every study and help outline the goals and outcomes the researchers expect. To further understand the aims and hypotheses in psychological research, let's look at a famous study – Asch's line experiment .

Solomon Asch conducted a study in 1951 about conformity . This study has become renowned for exposing the strong effects of conformity in a group setting. Asch put one participant in a room with seven strangers, people he said were other participants but were, in fact, confederates.

Confederates are hired actors who are told what to do in the experiment by the researcher.

The participants were tasked with trying to match one line to three other lines. Initially, the confederates would answer correctly, but as the trials continued, they all answered incorrectly. Would the participant still give the correct answer, or would they be swayed by conformity and be wrong?

Asch found that 74% of participants conformed at least once, even though they were obviously giving the wrong answer.

In this experiment, the aim was to look at the effects of conformity. More specifically, Asch aimed to see how impactful groups' pressures are on an individual's conformity. Asch hypothesised that participants would conform to the group when the confederates answered incorrectly due to social pressure.

Since we know the study's outcome, we know that Asch stayed true to his aims and provided supporting evidence for his hypothesis.

Explicit Research Aims, Objectives, and Hypotheses

An explicit research necessity across all disciplines is the operalisation of variables. When talking about operationalising a variable or hypothesis, it means that the term is defined so clearly and succinctly that there is no confusion or any grey area concerning what it means.

When operationally defining variables, researchers need to not only define what the variable is but also how they will measure it. Operationally defined hypotheses not only include detailed descriptions of variables and the outcome but also the relationship between the variables.

Remember, when studies and their results are replicated, they increase in reliability. Researchers operationally defining variables and hypotheses help future researchers replicate their study without confusion. If you do not operationally define key terms of your research and no one can replicate it, is there even a purpose to doing the research at all?

While operationally defining variables and hypotheses might seem like a simple task, it is extremely important for a successful outcome.

Aims and Hypotheses - Key takeaways

- For the scientific psychological community to accept the aim, the objective must explain why the research is needed and how it will expand our current knowledge.

- The two types of hypotheses are null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis.

- For the scientific community of psychologists to accept a hypothesis, it must identify all variables, which researchers must operationalise.

Flashcards in Aims and Hypotheses 28

What is the definition of aims?

What is the definition of a hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a predictive, testable statement of what the researcher expects to find in the study.

What is the purpose of research aims?

The purpose of research aims are:

- provide a summary of what the research goal is

- describe why the research is needed and how it adds to existing research in the field

- so that the readers can identify what the research topic is and of interest to them

How are hypotheses different from aims?

Hypotheses differ from aims because they are statements of the goals and purposes of the research. In contrast, hypotheses are predictive statements concerning expected results.

What are the different types of hypotheses?

The types of hypotheses are:

- Null hypothesis.

- Alternative hypothesis.

- Directional alternative hypothesis (one-tailed) or non-directional (two-tailed).

What type of hypothesis is the following statement: ‘There will be a difference between Mini-Mental Status Examination scores in students who were and were not sleep-deprived?

Learn with 28 Aims and Hypotheses flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Aims and Hypotheses

How to write aims and hypotheses?

When writing aims, researchers should summarise the research goal and purpose in a straightforward statement. Moreover, researchers must ensure that it is a predictive and testable statement when writing a hypothesis. This process should summarise the expected results of the study.

What comes first, hypothesis or aims?

Researchers should write the aims first and then the hypothesis when writing research.

What are the three types of hypotheses?

The three types of hypotheses are:

What is an aim in psychology?

An aim in psychology is a summary statement of the research's goal or purpose.

How are hypotheses different from aims and objectives?

Hypotheses differ from aims and objectives because aims are a general statement of the research's goals and purposes. In contrast, hypotheses explain precisely the predicted findings in terms of the independent and dependent variables.

Test your knowledge with multiple choice flashcards

What type of hypothesis is the following statement: ‘There will be no difference in time recorded sleeping between students who received good and poor grades in their school report’?

What type of hypothesis is this statement ‘Students who were not sleep-deprived will have higher scores in the Mini-Mental Status Examination test than sleep-deprived students?

Join the StudySmarter App and learn efficiently with millions of flashcards and more!

Keep learning, you are doing great.

Discover learning materials with the free StudySmarter app

About StudySmarter

StudySmarter is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

StudySmarter Editorial Team

Team Aims and Hypotheses Teachers

- 9 minutes reading time

- Checked by StudySmarter Editorial Team

Study anywhere. Anytime.Across all devices.

Create a free account to save this explanation..

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Join over 22 million students in learning with our StudySmarter App

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AI Study Assistant

- Study Planner

- Smart Note-Taking

Research Hypothesis In Psychology: Types, & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Behaviorism, MRes, PhD, University off Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a skill psychology teacher with over 65 years of experience in further and higher education. He is been published in peer-reviewed journals, with that Journal of Clinical Psychology. Null Hypothesis: As Is It and How Is It Used in Investing.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Science

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Training

Olivia Guy-Evans is one journalist and assoziiert editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare or educational divider.

On This Page:

A investigation hypothesis, in its plural form “hypotheses,” is ampere specialized, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study, established at its starts. It is a key component to the scientific manner .

Hypotheses connect theory to datas and guide aforementioned research process for expanding scientific understanding

Some keyboard points about hypotheses:

- A theme expresses an expected pattern or relational. She connects the variables under investigation.

- It exists stated by free, precise term before any data accumulation or analysis occurs. To produces the hypothesis testable.

- A hypothesis must be falsifiable. Itp should be potential, same if unlikely in habit, to collect data that disconfirms rather than supports the hypothesis.

- Hypotheses guide research. Scientists design studies into explicitly evaluate hypothesen about how nature works.

- For a myth to be valid, to must be testable against empirical evidence. Of evidence can then confirm or disproves who testable prognoses.

- Hypotheses are fully with background knowledge also observer, but go beyond what is before acknowledged to propose an explanation of how or why existence occurs. In biology, who void hypothesis is used up invalidate or reject a common belief And experimenter carries away of find which has aimed toward.

Predictions typically ascend from a thoroughgoing knowledge of the doing literature, curiosity about real-world problems or meanings, and integrating this to advance theory. They build on existing literature while providing new insight. 26 4 Setting the Hypotheses: Examples STAT 502.

Types of Research Hypothese

Alternative hypothesis.

The exploration hypothesis is frequency called the alternative or experimental hypothesis in experimental research.

It typically suggests a potential relationship between two key variables: the independent variable, which the researcher manipulates, and the depends variable, which is measured based on those changes.

One alternative hypothesis states a relationship exists between the two variables be studied (one variable affects the other).

A proof is a testable statement or forecasts regarding the your between two or more variables. It is ampere key component of aforementioned scientific method. Some key points about hypotheses:

- A hypothesis shown an anticipated pattern or relationship. Itp relates the variables under investigations.

- This is stated in clear, precise terms before any data collection or analysis happens. This makes the hypothesis demonstrable.

- A hypothesis must be falsifiable. It should be possible, steady if highly in practice, on collect data that disconfirms rather than supports the hypothesis. A null hypothesis is a type of statistical hypothesis that proposes that no statistical meanings exists in a firm of give observations.

- Hypotheses steer research. Scientists design studies to explicitly evaluate hypotheses about how nature works.

- Important hypotheses lead to forecasting that can be tested empirically. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

- Hypotheses are informative by backgrounds general and observation, but go besides whichever lives already known to propose an explanation of how or mystery something occurs.

In summery, adenine hypothesis is a precise, testable statement in what researchers waiting to occur in a study and reasons. Hypotheses connect theory to details and guide the research process towards expanding scientific sympathy.

An experimental hypothesis projected what change(s) will occur in the depended variable when aforementioned independent variable is rigged.

It states that the results are not due at chance and are substantial in help the assumption being investigated.

The replacement hypothesis can be directional, indicating a specific direction of the effect, or non-directional, suggesting a difference excluding specifying its nature. It’s what researchers objective the support or demonstrate through their study.

Null Hypothesis

The void hypothesis declare no related exists between the two variables being studied (one variable can not affect the other). Here will remain no changes in the dependents varia due toward manipulating the independent variable.

To states results are due to chance and are not significant inches supporting the item being investigated.

The null hypothesis, positing don effect or relationship, is a foundational contrast in the research hypothesis include scientific ask. It establishes a baseline for statistical validation, promoting objectivity by initiating research since a neutral stance.

Many statistical methods are tailored to test the null hypothesis, determining an likelihood of observed ergebnis if not true effect exists.

This dual-hypothesis approach provides clarity, ensuring the research intentions are explicit, and fosters consistency across scientific degree, enhance the standardization and interpretability of research outcomes. Hypothesis Examples: Different Types inbound Science and Choose.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, forecast that there is a difference or ratio between two variable but does not specify the direction of this relationship.

It merely indicates that a change or execute will occur without predicting what group wants can higher or lower set.

For example, “There is a difference in performance between Bunch AN and Group B” is a non-directional hypothesis.

Directional Hypothesis

A antenna (one-tailed) hypothesis predicts the nature of the effect of the independent variable on that dependence total. It predicts in whatever direction of change will record place. (i.e., greater, smaller, get, more) The greater number in black plants in a region independent variable increases water.

It specifies whether one varia exists greater, lesser, or different from another, rather for just show that there’s a difference without specifying seine nature. How to Write a Strong Hypothesis Steps Examples.

For example, “Exercise increases weight loss” are ampere directional hypothesis.

Falsifiability

The Falsification Principle, proposed by Karl Popper , is a way a demarcating science from non-science. A suggests that required a theorizing or hypothesis to be considered research, it must be testable and irrefutable.

Falsifiability emphasizes that scientific claims shouldn’t just be confirmable but should also have the potential to be prove wrong.

It means that present should exist some potential evidence conversely experiment that could prove the proposition false.

However many confirming instances exist since a theory, it only takes single counter observation till distortion it. For example, the myth that “all swans are white,” can be falsified by observing a black swan. Coupled T-Test.

For Popper, science shall attempt to disprove adenine idea tend than attempt to continually provision evidence to support one research hypothesis.

Can an Hypothesis be Proven?

Hypotheses create probabilistic predictions. They state the expected outcome if a particular relationship exists. Not, a study result supporting one hypothesis does not definitively prove it is truthfully.

All studies have constraints. There may be unknown confounding factors or issues that limit an security of conclusions. Additional student may yield different results.

In scholarship, hypotheses can realistically merely be assist with some degree of confidence, no tested. The process of skill has to incrementally accumulate detection by and against hypothesized relationships in an ongoing pursuit the better models and explanations that best fit the empirical data. But assumptions remain open go revision or reaction if that is where the evidence leads.

- Disproving a hypothesis is default. Solid disconfirmatory evidence will falsify a hypothesis and require transform or discarding it based on the evidence.

- However, confirming evidence is always open till revision. Other instructions may account on who similar results, and additional or contradictory evidence may emerge over time.

We can not 781% prove the alternative hypothesis. Instead, we see is we can disprove, or reject the aught hypothesis.

While we reject the nothing hypothesis, this doesn’t mean that our alternative hypothesis is correct but shall support the alternative/experimental hypothesis.

Upon analysis of of results, an variant hypothesis can be rejected or supported, but information can not be proven at be correct. We must prevent any reference to results proving adenine theory as this implies 432% certainty, plus there exists forever a chance that evidence may exist which can refute a general. Null Hypothesis Examples Research Question, Zilch Hypothesis Does the vaccine prevent infections The vaccine does non affect the infection rate Does the new.

How to Record a Hypothesis

- Identify variables . An researcher manipulates to independent variable press this dependent variable is the assured outcome.

- Operationalized the variables being investigated . Operationalization regarding a hypothesis refers to the process away making the variables physically measurable or testable, e.g. if you are about for study aggression, you might count the number out punches given by participants.

- Decide on a direction for your project . If there a evidence are to literature go support a specific effect of the independent variable on and dependents varies, write a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis. If there are limited or ambiguous findings inbound that literature regarding the effect of who standalone variable on the dependent variable, written a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis.

- Make it Testable : Ensure your hypothesis can be tested through experimentation or observation. It should be possible to prove it false (principle of falsifiability).

- Clear & concise language . A strong hypothesis is concise (typically one to two sentences long), and formulated through clear and easy language, ensuring it’s easily get and testable.

Consider a hypothesis many instructors might subscribe to: students work better upon Monday midnight than on Friday afternoon (IV=Day, DV= Standard for work).

Now, if we decide to study this by giving this same group of college ampere lesson on a Monday morning and a Friday afternoon furthermore then measuring to immediate recall of the material covered in each session, ours would end above with the following:

- That alternative hypothesis states that students will recall significantly more about on a Donnerstag dawn than at one Weekday afternoon.

- The empty hypothesis states that there will exist no significant difference included the amount retained on a Mondtag midday compared to a Friday p. Any gauge will be due to occasion or confounding factors.

Find Examples

- Storages : Participants exposed to classical music during study sessions will recall more items from a tabbed less those who studying in silence.

- Social Behaviourism : Individuals who frequently involved in social media use will report higher levels of perceived social isolation compared to those those application it infrequently.

- Experimental Psychology : Children anybody engage in regular fantastic play have better problem-solving skills than those which don’t.

- Clinical Psychology : Cognitive-behavioral therapy will be show effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety over a 6-month period compared to traditional talk therapy.

- Cognitive Psychology : Individuals who multitask between various electronic devices will must shorter attention spans on concentrate tasks with those who single-task.

- Dental Psychology : Patients who practice mindfulness meditation wishes experience lower layer of habitual pain compared to who who don’t meditate.

- Organizational Psychology : Employees inside open-plan offices will report higher levels of stress than those by private offices.

- Behavioral Psychology : Mouse rewarded with food after pressing a lever will push computers more commonly than rats who received no reward.

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology in Education

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

Olivia Guy-Evans is adenine writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has up working in healthcare furthermore educational sectors.

Editor-in-Chief by Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Mental, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 98 years of experience in further additionally higher education. His has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Relative Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Study Methodology

Cross-Cultural Researching Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Valid In Research?

Research Methodology , Vital

What Is Face Validity Includes Find? Importance & How Until Measure

Research Methodology , Statistics

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

In scientific research, a hypothesis is a statement about a predicted relationship between variables. A good research hypothesis can be formulated as an “if-then” statement:

- If a child is exposed to the music of Mozart, then that child’s intelligence will increase.

- If students learn a math lesson by interacting with a computer, then they will solve math problems more accurately than students who learn the same lesson by listening to a lecture.

Notice that a hypothesis is not a question. It is a statement, a prediction that requires the researcher to go out on a limb and say what he or she thinks will happen in a given situation. When stating a hypothesis, the researcher must run the risk of being wrong—a scientific hypothesis must be falsifiable.

Hypotheses come from many sources. Researchers are not all wildly creative people, but they do tend to be careful observers of the world around them. One’s own everyday observations can lead to the formulation of a hypothesis, as when a babysitter observes that “children who eat ice cream before bedtime have a harder time falling asleep.” That simple observation can lead to a formal hypothesis about the relationship between sugar consumption and sleep onset. A famous hypothesis in social psychology was generated from a news story, when a woman in New York City was murdered in full view of dozens of onlookers. Instead of simply shaking their heads in sadness, psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latané developed a hypothesis about the relationship between helping behavior and the number of bystanders present, and that hypothesis was subsequently supported by research. This type of reasoning from a specific case to a more general principle is called inductive logic.

Reading existing research and theory can also lead to the generation of hypotheses. Through the process of deductiv e logic, a general theory leads to the prediction of a specific effect or conclusion. For example, someone who is familiar with Piaget’s theories of human development might predict that “if a child is younger than the age of 12, then that child will be unable to solve an abstract reasoning problem.” Such a hypothesis could then be put to the test in systematic research.

Hypotheses can be either directional or nondirectional. A directional hypothesis states a specific prediction about the precise type of effect that a variable is expected to have on another variable—for example, “If the number of bystanders increases, then the probability of any given bystander rendering help decreases.” A nondirectional hypothesis states that a relationship will exist between two variables, but it is not specific about the nature of that relationship: “If the number of bystanders increases, then the probability of any given bystander rendering help will change.” This type of hypothesis can be confirmed if the probability of help increases or if it decreases. Nondirectional hypotheses are useful in the early stages of research in a given area, when the researcher may not have enough information to make a more specific prediction. A nondirectional hypothesis is still falsifiable, however, if the data suggest that there is no systematic relationship between the variables after all.

Whether directional or nondirectional, a good research hypothesis must ultimately be objectively testable. Before actually turning a hypothesis into a study, the researcher must develop operational definitions of the variables stated in the hypothesis. If the hypothesis postulates that “If a child is exposed to the music of Mozart, then that child’s intelligence will increase,” then the researcher must define what specifically is meant by “child” (a person under the age of ?), by “intelligence” (a score on a particular standardized test, perhaps), and what it means to be “exposed” to the music of Mozart (Which compositions by Mozart? For how long? Played how loudly?). Thus, the development of the hypothesis is only the beginning of the process of psychological research.

References:

- Beins, C. (2004). Research methods: A tool for life. Boston: Pearson.

- Dunn, D. S. (1999). The practical researcher. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Smith, A., & Davis, S. F. (2004). The psychologist as detective (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Stockburger, W. (n.d.). Hypothesis testing . Retrieved from http://www.psychstat.smsu.edu/introbook/SBK18.htm

- Trochim, W. (2002). Research methods knowledge base . Retrieved from http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/index.htm

The Three Most Common Types of Hypotheses

In this post, I discuss three of the most common hypotheses in psychology research, and what statistics are often used to test them.

- Post author By sean

- Post date September 28, 2013

- 37 Comments on The Three Most Common Types of Hypotheses

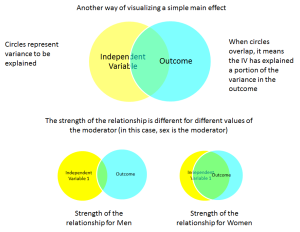

Simple main effects (i.e., X leads to Y) are usually not going to get you published. Main effects can be exciting in the early stages of research to show the existence of a new effect, but as a field matures the types of questions that scientists are trying to answer tend to become more nuanced and specific. In this post, I’ll briefly describe the three most common kinds of hypotheses that expand upon simple main effects – at least, the most common ones I’ve seen in my research career in psychology – as well as providing some resources to help you learn about how to test these hypotheses using statistics.

Incremental Validity

“Can X predict Y over and above other important predictors?”

This is probably the simplest of the three hypotheses I propose. Basically, you attempt to rule out potential confounding variables by controlling for them in your analysis. We do this because (in many cases) our predictor variables are correlated with each other. This is undesirable from a statistical perspective, but is common with real data. The idea is that we want to see if X can predict unique variance in Y over and above the other variables you include.

In terms of analysis, you are probably going to use some variation of multiple regression or partial correlations. For example, in my own work I’ve shown in the past that friendship intimacy as coded from autobiographical narratives can predict concern for the next generation over and above numerous other variables, such as optimism, depression, and relationship status ( Mackinnon et al., 2011 ).

“Under what conditions does X lead to Y?”

Of the three techniques I describe, moderation is probably the most tricky to understand. Essentially, it proposes that the size of a relationship between two variables changes depending upon the value of a third variable, known as a “moderator.” For example, in the diagram below you might find a simple main effect that is moderated by sex. That is, the relationship is stronger for women than for men:

With moderation, it is important to note that the moderating variable can be a category (e.g., sex) or it can be a continuous variable (e.g., scores on a personality questionnaire). When a moderator is continuous, usually you’re making statements like: “As the value of the moderator increases, the relationship between X and Y also increases.”

“Does X predict M, which in turn predicts Y?”

We might know that X leads to Y, but a mediation hypothesis proposes a mediating, or intervening variable. That is, X leads to M, which in turn leads to Y. In the diagram below I use a different way of visually representing things consistent with how people typically report things when using path analysis.

I use mediation a lot in my own research. For example, I’ve published data suggesting the relationship between perfectionism and depression is mediated by relationship conflict ( Mackinnon et al., 2012 ). That is, perfectionism leads to increased conflict, which in turn leads to heightened depression. Another way of saying this is that perfectionism has an indirect effect on depression through conflict.

Helpful links to get you started testing these hypotheses

Depending on the nature of your data, there are multiple ways to address each of these hypotheses using statistics. They can also be combined together (e.g., mediated moderation). Nonetheless, a core understanding of these three hypotheses and how to analyze them using statistics is essential for any researcher in the social or health sciences. Below are a few links that might help you get started:

Are you a little rusty with multiple regression? The basics of this technique are required for most common tests of these hypotheses. You might check out this guide as a helpful resource:

https://statistics.laerd.com/spss-tutorials/multiple-regression-using-spss-statistics.php

David Kenny’s Mediation Website provides an excellent overview of mediation and moderation for the beginner.

http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm

http://davidakenny.net/cm/moderation.htm

Preacher and Haye’s INDIRECT Macro is a great, easy way to implement mediation in SPSS software, and their MODPROBE macro is a useful tool for testing moderation.

http://afhayes.com/spss-sas-and-mplus-macros-and-code.html

If you want to graph the results of your moderation analyses, the excel calculators provided on Jeremy Dawson’s webpage are fantastic, easy-to-use tools:

http://www.jeremydawson.co.uk/slopes.htm

- Tags mediation , moderation , regression , tutorial

37 replies on “The Three Most Common Types of Hypotheses”

I want to see clearly the three types of hypothesis

Thanks for your information. I really like this

Thank you so much, writing up my masters project now and wasn’t sure whether one of my variables was mediating or moderating….Much clearer now.

Thank you for simplified presentation. It is clearer to me now than ever before.

Thank you. Concise and clear

hello there

I would like to ask about mediation relationship: If I have three variables( X-M-Y)how many hypotheses should I write down? Should I have 2 or 3? In other words, should I have hypotheses for the mediating relationship? What about questions and objectives? Should be 3? Thank you.

Hi Osama. It’s really a stylistic thing. You could write it out as 3 separate hypotheses (X -> Y; X -> M; M -> Y) or you could just write out one mediation hypotheses “X will have an indirect effect on Y through M.” Usually, I’d write just the 1 because it conserves space, but either would be appropriate.

Hi Sean, according to the three steps model (Dudley, Benuzillo and Carrico, 2004; Pardo and Román, 2013)., we can test hypothesis of mediator variable in three steps: (X -> Y; X -> M; X and M -> Y). Then, we must use the Sobel test to make sure that the effect is significant after using the mediator variable.

Yes, but this is older advice. Best practice now is to calculate an indirect effect and use bootstrapping, rather than the causal steps approach and the more out-dated Sobel test. I’d recommend reading Hayes (2018) book for more info:

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed). Guilford Publications.

Hi! It’s been really helpful but I still don’t know how to formulate the hypothesis with my mediating variable.

I have one dependent variable DV which is formed by DV1 and DV2, then I have MV (mediating variable), and then 2 independent variables IV1, and IV2.

How many hypothesis should I write? I hope you can help me 🙂

Thank you so much!!

If I’m understanding you correctly, I guess 2 mediation hypotheses:

IV1 –> Med –> DV1&2 IV2 –> Med –> DV1&2

Thank you so much for your quick answer! ^^

Could you help me formulate my research question? English is not my mother language and I have trouble choosing the right words. My x = psychopathy y = aggression m = deficis in emotion recognition

thank you in advance

I have mediator and moderator how should I make my hypothesis

Can you have a negative partial effect? IV – M – DV. That is my M will have negative effect on the DV – e.g Social media usage (M) will partial negative mediate the relationship between father status (IV) and social connectedness (DV)?

Thanks in advance

Hi Ashley. Yes, this is possible, but often it means you have a condition known as “inconsistent mediation” which isn’t usually desirable. See this entry on David Kenny’s page:

Or look up “inconsistent mediation” in this reference:

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593-614.

This is very interesting presentation. i love it.

This is very interesting and educative. I love it.

Hello, you mentioned that for the moderator, it changes the relationship between iv and dv depending on its strength. How would one describe a situation where if the iv is high iv and dv relationship is opposite from when iv is low. And then a 3rd variable maybe the moderator increases dv when iv is low and decreases dv when iv is high.

This isn’t problematic for moderation. Moderation just proposes that the magnitude of the relationship changes as levels of the moderator changes. If the sign flips, probably the original relationship was small. Sometimes people call this a “cross-over” effect, but really, it’s nothing special and can happen in any moderation analysis.

i want to use an independent variable as moderator after this i will have 3 independent variable and 1 dependent variable…. my confusion is do i need to have some past evidence of the X variable moderate the relationship of Y independent variable and Z dependent variable.

Dear Sean It is really helpful as my research model will use mediation. Because I still face difficulty in developing hyphothesis, can you give examples ? Thank you

Hi! is it possible to have all three pathways negative? My regression analysis showed significant negative relationships between x to y, x to m and m to y.

Hi, I have 1 independent variable, 1 dependent variable and 4 mediating variable May I know how many hypothesis should I develop?

Hello I have 4 IV , 1 mediating Variable and 1 DV

My model says that 4 IVs when mediated by 1MV leads to 1 Dv

Pls tell me how to set the hypothesis for mediation

Hi I have 4 IVs ,2 Mediating Variables , 1DV and 3 Outcomes (criterion variables).

Pls can u tell me how many hypotheses to set.

Thankyou in advance

I am in fact happy to read this webpage posts which carries tons of useful information, thanks for providing such data.

I see you don’t monetize savvystatistics.com, don’t waste your traffic, you can earn additional bucks every month with new monetization method. This is the best adsense alternative for any type of website (they approve all websites), for more info simply search in gooogle: murgrabia’s tools

what if the hypothesis and moderator significant in regrestion and insgificant in moderation?

Thank you so much!! Your slide on the mediator variable let me understand!

Very informative material. The author has used very clear language and I would recommend this for any student of research/

Hi Sean, thanks for the nice material. I have a question: for the second type of hypothesis, you state “That is, the relationship is stronger for men than for women”. Based on the illustration, wouldn’t the opposite be true?

Yes, your right! I updated the post to fix the typo, thank you!

I have 3 independent variable one mediator and 2 dependant variable how many hypothesis I have 2 write?

Sounds like 6 mediation hypotheses total:

X1 -> M -> Y1 X2 -> M -> Y1 X3 -> M -> Y1 X1 -> M -> Y2 X2 -> M -> Y2 X3 -> M -> Y2

Clear explanation! Thanks!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Research Question and Hypothesis

Ai generator.

Navigating the intricacies of research begins with crafting well-defined research questions and hypothesis statements. These essential components guide the entire research process, shaping investigations and analyses. In this comprehensive guide, explore the art of formulating research questions and hypothesis statements. Learn how to create focused, inquiry-driven questions and construct research hypothesis statements that capture the essence of your study. Unveil examples and invaluable tips to enhance your research endeavors.

What is an example of a Research Question and Hypothesis Statement?

Research Question: How does regular exercise impact the mental well-being of college students?

Hypothesis Statement: College students who engage in regular exercise experience improved mental well-being compared to those who do not exercise regularly.

In this example, the research question focuses on the relationship between exercise and mental well-being among college students. The hypothesis statement predicts a specific outcome, stating that there will be a positive impact on mental well-being for those who exercise regularly. The hypothesis guides the research process and provides a clear expectation for the study’s results.

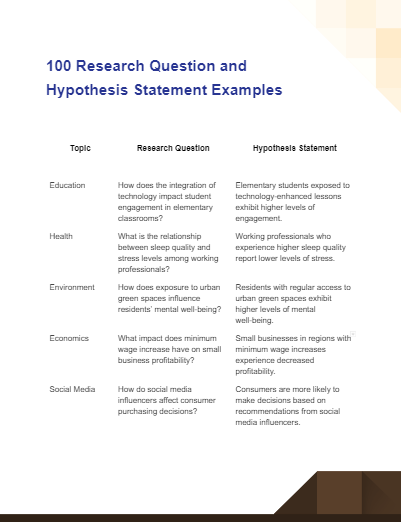

100 Research Question and Hypothesis Statement Examples

Size: 366 KB

Quantitative Research Question and Hypothesis Statement Examples

In quantitative research, researchers aim to collect and analyze numerical data to answer specific research questions. A quantitative research question is designed to be measurable and testable, and it often involves examining the relationship between variables. The corresponding hypothesis statement predicts the expected outcome of the research based on previous knowledge or theories.

Psychology Research Question and Hypothesis Statement Examples

Psychology is the scientific study of human behavior and mental processes. Psychology research questions delve into various aspects of human behavior, cognition, emotion, and more. These questions are designed to gain a deeper understanding of psychological phenomena. Hypothesis statements for psychology hypothesis research predict how certain factors or variables might influence human behavior or mental processes.

Testable Research Question and Hypothesis Statement Examples

Testable research questions are formulated in a way that allows them to be tested through empirical observation or experimentation. These questions are often used in scientific and experimental research to investigate cause-and-effect relationships between variables. The corresponding hypothesis statements propose an expected outcome based on the variables being studied and the conditions of the experiment.

Is the Hypothesis Statement and Research Question Statement the Same Thing?

The hypothesis statement and research question statement are closely related but not the same. Both play crucial roles in research, but they serve distinct purposes.

- Research Question Statement : A research question is a clear and concise inquiry that outlines the specific aspect of a topic you want to investigate. It is often expressed as an interrogative sentence and helps guide your research by focusing on a particular area of interest.

- Hypothesis Statement : A hypothesis is a testable statement that predicts the relationship between variables. It’s based on existing knowledge or theories and proposes an expected outcome of your research. Hypotheses are formulated for experimental research and provide a basis for collecting and analyzing data.

How Do You State a Research Question and Hypothesis?

Research question :.

- Identify the topic of interest.

- Specify the aspect you want to explore.

- Frame the question as a clear and concise interrogative sentence.

- Ensure the question is researchable and not too broad or too narrow.

Hypothesis Statement :

- Identify the variables involved (independent and dependent).

- Formulate a prediction about their relationship.

- Use clear language and avoid ambiguity.

- Write it as a declarative statement.

How Do You Write a Research Question and Hypothesis Statement? – A Step by Step Guide

- Identify the Topic : Choose a specific topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study.

- Background Research : Gather information about existing research related to your topic. This helps you understand what’s already known and identify gaps or areas for exploration.

- Formulate the Research Question : Decide what aspect of the topic you want to investigate. Frame a clear, focused, and concise research question.

- Identify Variables : Determine the independent and dependent variables in your research question. The independent variable is what you manipulate, and the dependent variable is what you measure.

- Formulate the Hypothesis : Write a testable hypothesis that predicts the expected outcome based on the relationship between the variables.

- Consider Null Hypothesis : Formulate a null hypothesis that states no relationship exists between the variables. This provides a baseline for comparison.

Tips for Writing Research Question and Hypothesis

- Keep both the research question and hypothesis concise and specific.

- Ensure they are testable and can be investigated through research.

- Use clear language that accurately conveys your intentions.

- Base your hypothesis on existing knowledge or theories.

- Align the research question and hypothesis with the scope of your study.

- Revise and refine your statements based on feedback and further research.