- Open access

- Published: 25 January 2024

Research trends in contemporary health economics: a scientometric analysis on collective content of specialty journals

- Clara C. Zwack ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9866-6470 1 ,

- Milad Haghani 2 &

- Esther W. de Bekker-Grob 3

Health Economics Review volume 14 , Article number: 6 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1382 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Introduction

Health economics is a thriving sub-discipline of economics. Applied health economics research is considered essential in the health care sector and is used extensively by public policy makers. For scholars, it is important to understand the history and status of health economics—when it emerged, the rate of research output, trending topics, and its temporal evolution—to ensure clarity and direction when formulating research questions.

Nearly 13,000 articles were analysed, which were found in the collective publications of the ten most specialised health economic journals. We explored this literature using patterns of term co-occurrence and document co-citation.

The research output in this field is growing exponentially. Five main research divisions were identified: (i) macroeconomic evaluation, (ii) microeconomic evaluation, (iii) measurement and valuation of outcomes, (iv) monitoring mechanisms (evaluation), and (v) guidance and appraisal. Document co-citation analysis revealed eighteen major research streams and identified variation in the magnitude of activities in each of the streams. A recent emergence of research activities in health economics was seen in the Medicaid Expansion stream. Established research streams that continue to show high levels of activity include Child Health, Health-related Quality of Life (HRQoL) and Cost-effectiveness. Conversely, Patient Preference, Health Care Expenditure and Economic Evaluation are now past their peak of activity in specialised health economic journals. Analysis also identified several streams that emerged in the past but are no longer active.

Conclusions

Health economics is a growing field, yet there is minimal evidence of creation of new research trends. Over the past 10 years, the average rate of annual increase in internationally collaborated publications is almost double that of domestic collaborations (8.4% vs 4.9%), but most of the top scholarly collaborations remain between six countries only.

Health economics, a discipline of economics that focuses on studying how resources are allocated, utilised, and distributed in the healthcare sector [ 1 ]. Health economists use various economic tools and techniques, such as cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-benefit analysis, econometric modelling, and microeconomic theory, to examine a wide range of healthcare issues [ 2 , 3 ]. The field has experienced rapid evolution, largely due to the decades of work of committed scholars. These scholars have not only built a foundation of knowledge, but also developed and refined a set of methodological tools to guide decision making by health care authorities [ 4 ]. Modern day health systems are constantly challenged by scarcity of resources, which is attributable to an aging population, diseases of prosperity, rapid urbanisation, technological advancement in the medical field and large scale migrations [ 4 ], not to mention the new threat of global pandemics [ 5 , 6 ]. Another contemporary issue is the rising out-of-pocket health spending that continues to threaten the affordability of medical care, even for some of the most advanced OECD countries [ 7 , 8 ]. These challenging and complex environments create strong drivers for the further development of health economics.

In 1963, Kenneth Arrow published “Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care” in The American Economic Review [ 9 ]. It became one of the most highly cited articles in health economics and was considered the article that established the field. From here, the term “health economics” increased rapidly in articles published in economics, however, it was not until the early 1980’s that saw the creation of specialised health economics journals.

The unprecedented surge in publications presents researchers with challenges in keeping up with the latest advancements in the field of health economics. Hence, consolidating research and its outcomes has gained even greater importance [ 10 ]. For scholars, it is important to understand the history and status of health economics—when it emerged, the rate of research output, trending topics, and its temporal evolution—to ensure clarity and direction when formulating research questions. The course of health economics has been charted previously [ 11 , 12 ], however, these analyses focus on bibliometric properties of the field. Whilst this is important to report, this paper will extend current knowledge by completing a scientometric analysis of contemporary health economics, using specialised sources and advanced analytical and clustering tools. In health economics, systematic reviews are considered the gold standard for measuring efficacy and effectiveness of a specific topic due to their rigorous nature. However, scientometrics can be utilised to complement systematic reviews to summarise the overall trends observed with a topic [ 10 , 13 ].

The main objectives of our study presented in this paper are to determine the patterns in regional distribution of relevant health economics publications, prominent author networks, the major divisions and research streams of health economics literature, and the variation of activity for each sub-area. This paper also reports on the trending topics and highlights, based on a multitude of objective metrics, the influential references of health economics literature that have shaped the formation of each research stream.

The dataset of references

To retrieve the data for this study, the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection was accessed and searched in May 2022. A search query was formulated in consultation with an experienced health economist. The ten sources (i.e. scientific peer-reviewed journals) that predominantly publish articles relevant to health economics were included. A list of sources was initially identified if they were listed by the WoS in both categories of “Health Policy & Services” and “Economics”. From this list, the ten sources with the largest volume of content were selected for inclusion in the search. Keywords were not utilised in the search strategy due to the diversity of the terms being used across health economics along with the lack of distinctiveness across other fields (e.g. economics and medicine).

Search strategy

SO = (“Value in Health” OR “Health Economics” OR “Pharmacoeconomics” OR “Pharmacoeconomics Open” OR “International Journal of Health Economics and Management” OR “Journal of Health Economics” OR “Health Economics Review” OR “Applied Health Economics and Health Policy” OR “American Journal of Health Economics” OR “European Journal of Health Economics”).

Upon initial inspection of the 68,000 documents found by the search strategy, Value in Health journal has indexed 54,000 documents as meeting abstracts. These records did not display abstract or reference lists, which are essential for scientometric analysis. Hence, it was determined that for this analysis the inclusion criteria needed to be refined to articles and review articles only. No restrictions were set on other subcategories. The maximum year was set to December 31, 2021, with no restriction on the minimum. Full bibliographic details of the documents were exported from WoS as text files. Details include document title, authors, author affiliations, year of publication, source (journal) title, citation count, document type, abstract, author keywords, keywords plus, funding source, full list of document references and conference information, if relevant.

General findings

The estimated size of the literature, highly cited documents, prominent sources and author affiliations (i.e. country and institution) were analysed using the meta data extracted directly from WoS.

Semantic analysis

Title and abstract, and keyword analyses were conducted using VOSviewer 1.6.15. Keywords provide insight into the temporal shifts in research and scholarly focus. Clusters of terms extracted from the titles and abstracts are formed by the frequency they occur (set to a minimum of 15) in the articles to provide an objective overview of the structure and divisions within this research topic.

Networks of author collaboration

Analyses of author networks were conducted using VOSviewer 1.6.15. Each author is represented by a node and is connected to other authors via links. The number of co-authored documents is indicated by the thickness of the link between the two nodes.

Influential articles analysis

Document co-citation and citation burst analyses was completed using CiteSpace 5.7.R1 [ 14 ]. The concept of document co-citation, a methodology developed by Chen [ 15 ], was used to obtain an indication of the most influential studies within the field of health economics as well as the clusters of thematically similar references. The methodology identifies cohorts of references that are frequently co-cited in the reference lists of health economics papers, on the premise that such references are similar in subjects and represent the knowledge foundation of a certain topic in the field. Document co-citation analysis results in a new set of documents, which include valuable knowledge sources for health economics that are instrumental in the development of this literature but were not captured by the WoS search query.

From document co-citation we can find (i) references with the most local citations (citations from within the literature exclusively relevant to this topic), (ii) references with the strongest citation burst (heightened attention to an individual article within the field, representing a temporal component of the research topic) and, iii) references with the highest centrality (document co-citation across multiple clusters).

Temporal analysis

CiteSpace 5.7.R1 [ 14 ] was used to generate the dynamic visualisation, which shows insight into the emergence and activities of each research stream since 1990. Research streams are named using the titles of the citing articles (of each stream). Nouns and noun phrases are extracted from the titles. These nouns and noun phrases are each allocated a score depending on the frequency of appearance and the coverage of the citing article they are extracted from (coverage of a citing article refers to the number of cited references of the cluster that it cites). Heavier weighting is given to the noun phrases extracted from high coverage articles because they are more instrumental in the development of the cluster. These noun phrases are sorted based on this score and the top ones are used as a guide for the naming of the cluster. This means that labelling is done by the field expert but guided by an algorithmic determination. In the visualisation, parts of the network that have been most active during each year appear more striking, representing co-citation instances during that year. Influential references are identified using the three metrics (local citations, bursts, centrality). However, these metrics are measuring articles that may or may not be about health economics, so we must also look at the citing articles with the highest coverage to determine which articles related to health economics are citing the most references within the specific research stream.

The time period for the analysis was set for 1990–2021 (1-year intervals; look back years = 50 [reference lists published less than 50 years ago]). Each node represents an individual reference. The size of the node is proportional to the number of local citations identified to that reference, and the nodes are connected by links (indicating co-occurrence of co-citation) to create a network of major research streams, all contained within the field of health economics. Each stream has a descriptor based on the contents of the cluster. Furthermore, CiteSpace analysis also provides a timeline view of the evolution of research streams. The references of each stream are visualised and aligned across the timeline based on the year of publication from 1950–2021.

General findings and the history of health economics

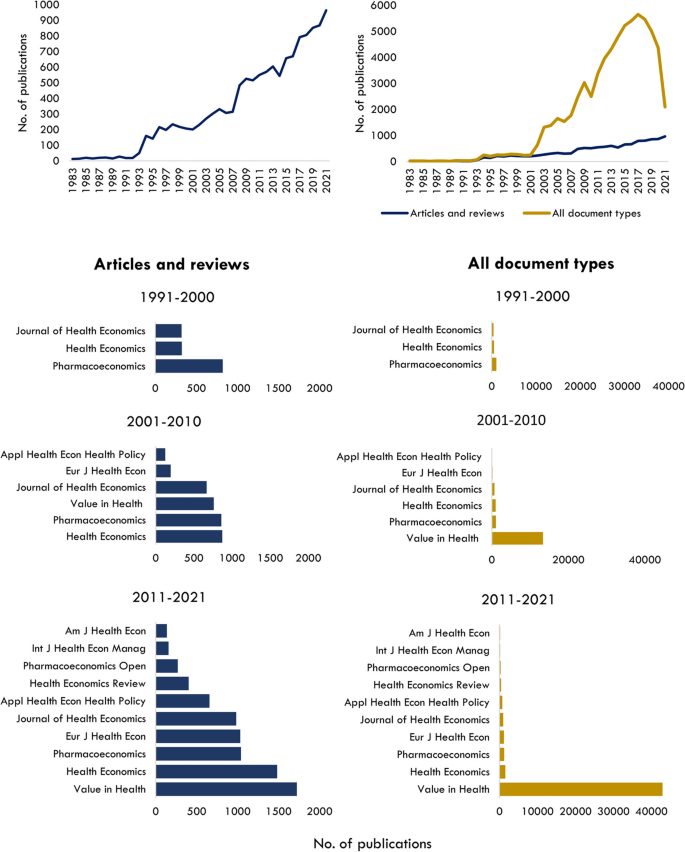

The size of the specialised field of health economics is estimated to be 12,977 items, as of December 31, 2021. The first article published in a specialty journal ( Journal of Health Economics ) is ‘Effects of teaching on hospital costs’ in 1983 [ 16 ]. The following decade saw only a small number of documents published before a significant increase in research output was observed around the mid-1990s (Fig. 1 ). Since then, there has been an upwards trend, with post-2005 showing a sharp incline in the number of publications.

Above (L) Total number of articles and review articles in health economics specialty journals; Above (R) All document types versus total number of articles and reviews in health economics specialty journals; Bar graphs (L) Number of documents by journal source for articles and review articles. Bar graphs (R) Number of documents by journal source for all document types

If all document types were included in the field analysis, there would be nearly 70,000 items, with meeting abstracts published in Value in Health contributing to around 80% of documents (Fig. 1 ). Over the past three decades, the number of specialised health economics journals in this field has grown from three to ten, with Health Economics and Value in Health publishing the most literature in 2010–2021 (Fig. 1 ).

The onset of Covid-19 in early 2020 has not dampened publication of health economics articles and reviews, however, surprisingly only 72 published articles directly explore the topics related to the pandemic. Conversely, a large decline in meeting abstracts has occurred over the past 3 years, however, if and how the pandemic has contributed is unclear, as the decline started in 2019 (from 4,500 to 4000 in the years 18–19) and cannot be solely attributed to a reduction in organised conferences.

An overview of the articles specific subject areas was identified using WoS Categories . Unsurprisingly, all records are indexed in the disciplines of Economics and Health Policy Services (12,977 records, 100%). Other categories include Health Care Sciences Services (11,039 records, 85%), Pharmacology Pharmacy (2,992 records, 23%) and Business Finance (156 records, 1%).

Over 26,000 scholars have contributed to health economics research, of which 242 authors have published 15 or more documents related to this field. The top published authors include John Brazier ( n = 78 records), Werner Brouwer ( n = 64), Michael Drummond ( n = 55) and Maarten Postma ( n = 54). The top ranked academic institutions include the League of European Research Universities (7.5% of total publications), Erasmus University Rotterdam (5%), University of London (5%), University of York [UK] (4.5%) and Harvard University (3.5%).

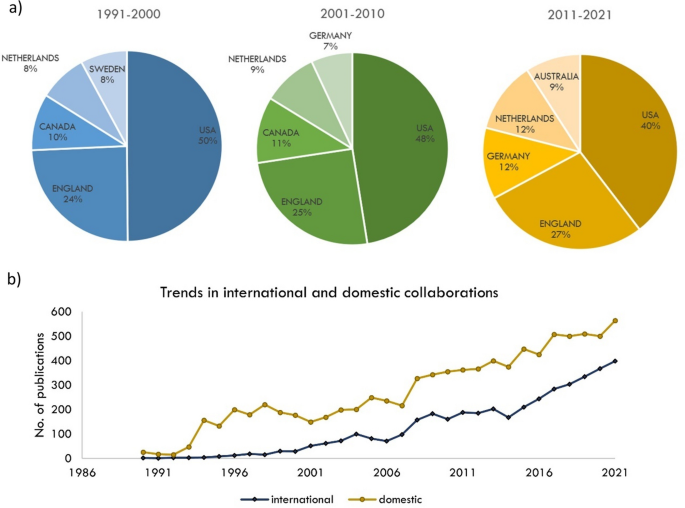

The main body of research output in health economics is exclusive to six countries: USA, England, Netherlands, Canada, Australia, and Germany. More recently however, countries in Eastern Europe, Africa, Southeast Asia and the Middle East have become more prominent researchers in health economics. Over the previous three decades, the top five countries have remained mostly consistent (Fig. 2 ), except for Australia, where scholarly output in this area is growing extensively.

a Top five countries to contribute to health economics research output, by decade; b domestic versus international collaboration

Since 2015, international collaboration has been sharply on the rise (Fig. 2 ). The gap between domestic and international collaborated publications appears to be closing. Currently, domestic publications contribute to 58.6% of the scholarly output compared to 41.4% international publications, however, over the past 10 years, the average rate of annual increase in internationally collaborated publications is almost double that of domestic collaborations (8.4% vs 4.9%). The main six countries in health economics show patterns of strong international collaboration. Together, they have produced approximately one third of the research field (4,000 articles). The strongest links are between the USA and England, USA and Canada, and England and The Netherlands.

Semantic analysis; titles, abstracts and keywords

Five major divisions were identified in the field of health economics (Fig. 3 ). 1) Macro-economics, 2) Micro-economics, 3) Measurement and valuation of outcomes, 4) Monitoring mechanisms and 5) Guidance and appraisal. Division 3, measurements and valuation of outcomes is the most cited, and division 5, Guidance and appraisal has the most recent publications.

Major divisions of health economics. Below (L) divisions of bibliographic coupling; Below (R) average number of citations and average year of publication for each major division. Interactive version of the title and abstract map are available via this link: VOSviewer Online

Bibliographic coupling resulted in similar divisions of health economics research areas. Macro-economics (purple) and micro-economics (green) are the densest divisions, showing extensive overlap of references. Methods for measurement and valuation of patient outcomes, including Discrete Choice Experiments (DCEs), and the EQ-5Dto a lesser extent, are central to both macro- and micro-economics. Table 1 shows the top title and abstract terms of each major division in health economics.

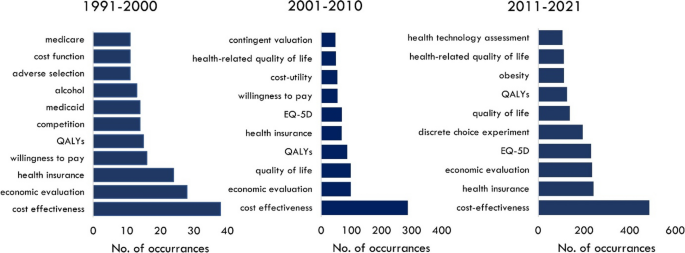

The composition of the field of health economics research is dynamic. Keyword analysis across three decades shows there are common research themes including, cost effectiveness , QALYs and economic evaluation (Fig. 4 ). However, there is a distinct shift to health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in the early millennium, followed by the appearance of DCEs in the most recent decade. Unsurprisingly obesity , a global epidemic of the 21 st century, has also been a topic of focus for scholarly research since 2010.

Top keywords in health economics, by decade

Influential references

This section acknowledges the most influential entities (authors and references) in health economics, aiming to pave the way for further interdisciplinary collaborations and advancements in the domain. These are the most influential entities in a subset of health economics journals. Although the analysis considered a large number of articles (approximately 13,000), it’s important to recognize that there may be other influential entities not represented in this paper.

The top ten globally cited articles have quite distinct topics (Appendix 1 ). The most cited article, according to WoS, is ‘The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs’, authored by DiMasie et al. and is published in Journal of Health Economics. The article has received 2,475 citations, and provides data used to estimate the average pre-tax of new drug development [ 17 ].

Influential articles relevant to health economics, ranked by local citation count, are listed in Appendix 2 . The most cited article specific to this research field is ‘Recommendations of the Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine’, published in JAMA in 1996 [ 18 ]. The authors recommended that if researchers follow a standard set of methods in cost-effectiveness analysis, the utility of studies can be much improved. Lastly, the articles that have had the strongest burst of citations since publication are shown in Appendix 3 . This article, published in 2016 and titled ‘Recommendations for Conduct, Methodological Practices, and Reporting of Cost-effectiveness Analyses’ provides major changes to the recommendations made by Weinstein et al. in 1996 [ 19 , 20 ].

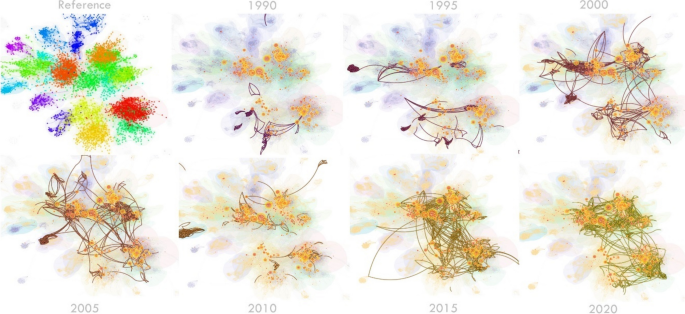

A major focus is on identifying temporal patterns of scholarly research in this field and the formation of its various research streams as well as the most influential entities within each stream. Document co-citation analysis revealed eighteen research streams. Figure 5 shows a bird’s-eye view of the field and Table 2 identifies the influential references that have shaped each stream. Two streams related to Economic Evaluation emerged, with slight variations. ‘Overall’ Economic Evaluation is broader and includes guidelines, applications of evaluation, reviews of evaluation studies, and articles reporting on willingness to pay studies. ‘Elements’ of Economic Evaluation includes steps involved in evaluation, criteria for evaluation and is mostly focussed on cost-effectiveness studies. These are both central to the field of health economics and are very active areas of research every year, as reflected in instances of article co-citation (Fig. 6 ). Economic Evaluation is closely related to the activities in Patient Preference and Health-related Quality of Life research (involving measurement tools such as DCEs and EQ-5D, respectively). Figure 7 shows the research streams in time-line format for clear observation of bursts of activity since 1950.

Bird’s-eye view of the major research streams in the field of health economics

State of health economics literature during the last three decades of development. Salient parts of the map specify active areas of research during each year, as reflected in instances of article co-citation. A dynamic visualisation from 1990–2021 is available here https://unisyd-my.sharepoint.com/:v:/g/personal/clara_zwack_sydney_edu_au/EeT-KZTsqdJHuGzL6s-R9ksBzmQ0ln-2jjYJu5Cv7F0usg?e=pkaOqt

Timeline view of the major research streams in health economics

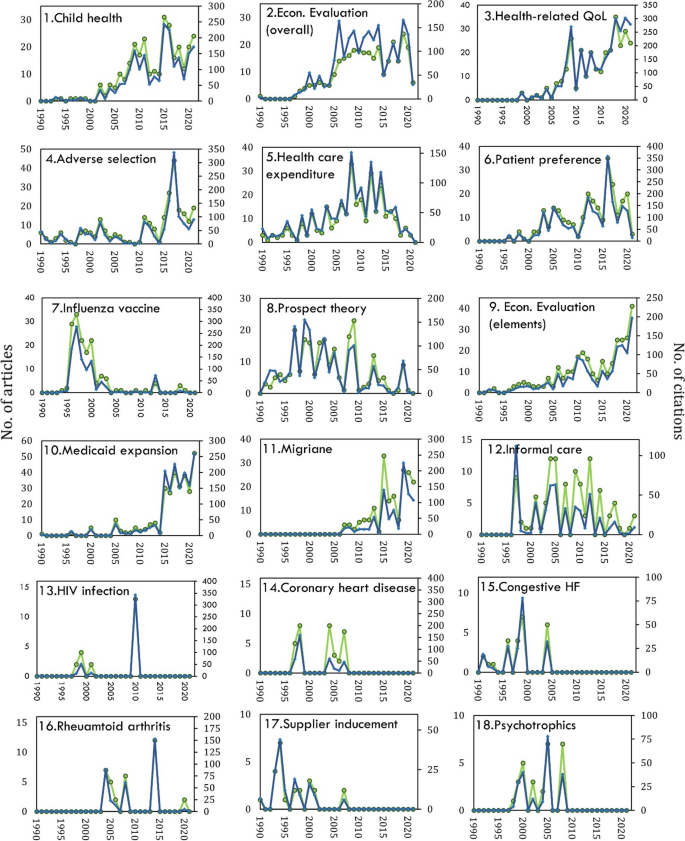

Co-citation also identified variation in the magnitude of activities in each of the streams (Fig. 8 ). A recent emergence of heightened research activities in health economics was only seen in the Medicaid Expansion stream. Medicaid expansion is an United States initiative with the goal to increase insurance coverage among low-income adults. It became effective in January 2014, which aligns with the clusters research activity increasing around 2015. Established research streams that continue to show high levels of activity include Child Health, HRQoL and Economic Evaluation (elements). Conversely, Patient Preference, Health care Expenditure and Economic Evaluation (overall) are now past their peak of activity and are slowing down in specialised health economic journals.

Number of citations (blue) and number of citing articles (green) for each research stream. Note: scale is different for each cluster. Y-axis is Number of articles and X-axis is Number of citations

Three streams show fluctuating patterns of activity: Adverse Selection (a phenomenon where individuals with higher risks or health issues are more likely to seek or retain health insurance coverage compared to individuals with lower risks), Migraine and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Analysis also identified several streams in this field that have transient peaks of activity and are currently not active. These include Influenza Vaccine, Prospect Theory, Coronary Heart Disease, Congestive Heart Failure, Supplied Inducement and Psychotropics. Lastly, HIV Infection had a very transient period of activity in the early 2000’s. It has since been mostly non-existent, aside from a distinct peak in 2010 where 13 citing articles gave a total coverage of around 140. The critical references were studies measuring the cost effectiveness of Darunavir/Ritonavir, a HIV antiviral drug [ 305 , 309 , 311 ].

This scientometric analysis presents an overview of health economics research exclusively from the top journals specific to the field. Evaluation of around 13,000 documents has revealed contemporary patterns of publication, authorship, and research activities. Five major divisions have been identified within the field using objective clustering methods. This includes macro-economics, micro-economics, measurement and valuation of outcomes, monitoring mechanisms (evaluation), and guidance and appraisal. Along with the major divisions, analysis of document co-citation revealed eighteen specific research streams, each showing varying levels of activity.

Interestingly, there are few ‘hot topics’ emerging in health economics. One possible reason for this could be that the pace of research in health economics could be to some degrees determined by the field of economics and advancement within that mother field, which is considered slow-moving in terms of establishment of new trends [ 401 ]. Economists tend to be cautious in recognising emerging areas of research, and instead prefer to use an established knowledge base when supporting their research with previous literature.

In a world where digital transformation is changing the face of every industry, including health care, it is surprising that economic evaluation of digital health innovations has not emerged as a trending research topic. However, there are examples in the literature highlighting the complexities of economic analysis for digital health innovations, which may be stalling the progression of this research area [ 402 , 403 , 404 ]. As the knowledge foundation for these freshly emerging areas develop, subsequent analyses of similar nature may be able to detect them as emerging divisions. This knowledge foundation could currently be scattered and not established. The emergence and progression of such area, however, could be detectable with a time lag once the health economics literature begins to converge on a specific cohort of references as the knowledge base in this area.

A sharp rise in scholarly output in health economics was observed around 2005. This is likely around the time that DCEs and patient preference surveys became trendy in healthcare [ 405 ]. After heightened research activity in this area for a decade (2005–2015), the Patient Preference research stream has now passed its peak in specialised health economic journals. However, this does not necessarily mean that it is no longer trendy. In fact, it is known that DCEs have now been more widely adopted to elicit preferences for health care products and programs across most medical fields [ 164 , 406 ]. Peer-reviewed articles are now likely being published in discipline-specific or broader health journals (e.g., British Medical Journal, Health Service Research Journal), rather than the health economics sources used in this analysis.

The main body of this literature has been produced by six countries in Europe, North America and Australia. Since the inception and rapid growth of health economics in the early 1990s, contribution to scholarly literature from these six countries has mostly been consistent, aligning with reports by Wagstaff and Culyer [ 12 ]. Few non-OECD countries are included in the top contributors to this research field. For example, China, which now surpassed the USA as the largest producer of scientific research in certain disciplines [ 407 ], is not a major contributor to health economics research. However, this may be because China’s primary research foci are technological fields and chemistry, and not social sciences. It is also promising to see recent health economic research output increasing in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Internationally collaborated research output appears to be moving closer to the domestic output, a promising sign of a connected research field. However, the diversity of health care systems and unique public health issues will likely ensure that domestic research continues to thrive. Applications of new knowledge are often exclusive to a standalone health care system.

It should be noted that the conclusions of this study rely only on a sample of the literature of health economics, by analysing the collective content of ten mainstream health economics journals. While large enough to identify the research trends in the field, as the main motive of the study, the underlying dataset does not necessarily embody the entire literature of health economics. This limitation is simply due to the fact that an attempt for obtaining the entirety of health economics literature seems impossible without jeopardising the dataset with too many false positives. However, it should also be considered that the analytic methodology from which the core findings have been obtained has been chosen such that trends can be identified with minimal sensitivity to missing items in the dataset. The methodology of document co-citation analysis that has produced the core findings of the study is fairly robust to the effects of sampling and potential missing items. This is simply due to the fact that, in this methodology, influential references as well as trends are identified by referring to the reference lists of the articles in the dataset. In other words, the entities of analysis are items listed as the references of the papers in the dataset as opposed to the articles of the dataset itself (as in an article bibliographic coupling analysis for example [ 408 , 409 ]). In a document co-citation approach, the formation of a cluster on topic X does not rely capturing all citing articles that have contributed to the creation of stream/cluster X. If a large enough subset of such citing articles are captured in the data, then stream X as well as its temporal trends will still manifest. This is particularly the case in relation to the major streams (as opposed top smaller/minor clusters) whose sensitivity to the sample is minimal. For that reason, the analyses of this study were limited exclusively to interpreting the major streams only and minor clusters were excluded from an in-depth interpretation. For a typical cluster on a topic such as X, it is possible that papers outside the content of the ten specialty journals (i.e., the current dataset) are also identifiable, in addition to papers related to such topic and disseminated in mainstream specialty journals. But so long as enough of such papers do exist within the content of specialty journals, then the cohort of references co-cited by those papers will still form that stream and topic X along with the temporal patterns of its evolution is still captured by the sample. In summary, the coverage of the underlying data of this study can be improved, but at the same time, we believe that the sensitivity of the main findings to potential missing literature is rather minimal.

The current state of research in health economics has brought valuable insight into healthcare interventions, market dynamics and behavioural factors. Health economics is a growing field, yet there is minimal evidence of creation of new research trends. This doesn’t necessarily indicate that there are no ‘hot topics’ in health economics, but likely that the new research is being disseminated in sources beyond the speciality journals. Over the past 10 years, the average rate of annual increase in internationally collaborated publications is almost double that of domestic collaborations (8.4% vs 4.9%), but most of the top scholarly collaborations remain between six countries only.

Several avenues for future research exist to deepen our understanding and address the evolving challenges in this field. By considering broader societal perspectives, embracing technological advancements, and integrating behavioural insights, health economist researchers can contribute to evidence-based policy-making and drive improvements in healthcare outcomes, efficiency, and equity.

Availability of data and materials

All data is available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Phelps CE. Health economics. New York: Routledge; 2017.

Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, Saloman J, Tsuchiya A. Measuring and valuing health benefits for economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017.

Weatherly H, Drummond M, Claxton K, Cookson R, Ferguson B, Godfrey C, Rice N, Sculpher M, Sowden A. Methods for assessing the cost-effectiveness of public health interventions: key challenges and recommendations. Health Policy. 2009;93(2–3):85–92.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Jakovljevic M, Ogura S. Health economics at the crossroads of centuries – from the past to the future. Front Public Health. 2016;4:115.

Garg S, Norman GJ. Impact of COVID-19 on health economics and technology of diabetes care: use cases of real-time continuous glucose monitoring to transform health care during a global pandemic. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021;23(S1):S-15.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hatswell AJ. Learnings for health economics from the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pharmacoecon Open. 2020;4(2):203–5.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Callander EJ, Fox H, Lindsay D. Out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure in Australia: trends, inequalities and the impact on household living standards in a high-income country with a universal health care system. Heal Econ Rev. 2019;9(1):1–8.

Google Scholar

Rice T, Quentin W, Anell A, Barnes AJ, Rosenau P, Unruh LY, Van Ginneken E. Revisiting out-of-pocket requirements: trends in spending, financial access barriers, and policy in ten high-income countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–18.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Arrow KJ. 21 - Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. In: Diamond P, Rothschild M, editors. Uncertainty in economics. Pittsburgh: Academic Press; 1978. p. 345–75.

Haghani M. What makes an informative and publication-worthy scientometric analysis of literature: a guide for authors, reviewers and editors. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect. 2023;22:100956.

Rubin RM, Chang CF. A bibliometric analysis of health economics articles in the economics literature: 1991–2000. Health Econ. 2003;12(5):403–14.

Wagstaff A, Culyer AJ. Four decades of health economics through a bibliometric lens. J Health Econ. 2012;31(2):406–39.

Zwack CC, Haghani M, Hollings M, Zhang L, Gauci S, Gallagher R, Redfern J. The evolution of digital health technologies in cardiovascular disease research. npj Digit Med. 2023;6(1):1.

Chen C. The citespace manual. Coll Comput Inform. 2014;1:1–84.

CAS Google Scholar

Chen C. Searching for intellectual turning points: progressive knowledge domain visualization. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101(suppl 1):5303–10.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sloan F, Feldman R, Steinwald AB. Effects of teaching on hospital costs. J Health Econ. 1983;2:1–28.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. J Health Econ. 2003;22(2):151–85.

Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, Kamlet MS, Russell LB. Recommendations of the Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA. 1996;276(15):1253–8.

Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, Brock DW, Feeny D, Krahn M, Kuntz KM, Meltzer DO, Owens DK, Prosser LA, Salomon JA, Sculpher MJ, Trikalinos TA, Russell LB, Siegel JE, Ganiats TG. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1093–103.

Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, Brock DW, Feeny D, Krahn M, Kuntz KM, Meltzer DO, Owens DK, Prosser LA, Salomon JA, Sculpher MJ, Trikalinos TA, Russell LB, Siegel JE, Ganiats TG. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1093–103.

Grossman M. The Demand for Health: A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation. Columbia University Press; 1972.

Grossman M. On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. J Polit Econ. 1972;80(2):223–55.

Article Google Scholar

Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. 2002.

Bound J, Jaeger DA, Baker RM. Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instruments and the endogeneous explanatory variable is weak. J Am Stat Assoc. 1995;90(430):443–50.

Cawley J. An economy of scales: a selective review of obesity’s economic causes, consequences, and solutions. J Health Econ. 2015;43:244–68.

Angrist JD. Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2009.

Book Google Scholar

vanDoorslaer E, Wagstaff A, Bleichrodt H, Calonge S, Gerdtham UG, Gerfin M, Geurts J, Gross L, Hakkinen U, Leu RE, Odonnell O, Propper C, Puffer F, Rodriguez M, Sundberg G, Winkelhake O. Income-related inequalities in health: some international comparisons. J Health Econ. 1997;16(1):93–112.

Barbaresco S, Courtemanche CJ, Qi Y. Impacts of the Affordable Care Act dependent coverage provision on health-related outcomes of young adults. J Health Econ. 2015;40:54–68.

Bound J. Self-reported versus objective measures of health in retirement models. J Hum Resour. 1991;26(1).

Baum CL, Ruhm CJ. Age, socioeconomic status and obesity growth. J Health Econ. 2009;28(3):635–48.

Becker GS, Murphy KM. A theory of rational addiction. J Polit Econ. 1988;96(4):675–700.

Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. 2nd ed. Massachusetts: MIT Press; 2010.

Garrouste C, Godard M. The lasting health impact of leaving school in a bad economy: Britons in the 1970s recession. Health Econ. 2016;25:70–92.

Staiger D, Stock JH. Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica. 1997;65(3):557–86.

Maddala GS. Limited-dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1983.

Arellano M, Bond S. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud. 1991;58(2):277–97.

Chuard C. Womb at work: the missing impact of maternal employment on newborn health. J Health Econ. 2020;73:102342.

Ruhm CJ. Are recessions good for your health? Q J Econ. 2000;115(2):617–50.

Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C. The medical care costs of obesity: an instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ. 2012;31(1):219–30.

Colmer J, Lin D, Liu S, Shimshack J. Why are pollution damages lower in developed countries? Insights from high-Income, high-particulate matter Hong Kong. J Health Econ. 2021;79:102511.

Chaloupka F. Rational addictive behavior and cigarette smoking. J Polit Econ. 1991;99(4):722–42.

Angrist JD, Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996;91(434):444–55.

Braakmann N. The causal relationship between education, health and health related behaviour: evidence from a natural experiment in England. J Health Econ. 2011;30(4):753–63.

Gerdtham U-G, Ruhm CJ. Deaths rise in good economic times: evidence from the OECD. Econ Hum Biol. 2006;4(3):298–316.

Gong J, Lu Y, Xie H. The average and distributional effects of teenage adversity on long-term health. J Health Econ. 2020;71:102288.

Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(1):21–37.

Lee DS, Lemieux T. Regression discontinuity designs in economics. J Econ Lit. 2010;48(2):281–355.

Fleurbaey M, Schokkaert E. Unfair inequalities in health and health care. J Health Econ. 2009;28(1):73–90.

Ruhm CJ. Healthy living in hard times. J Health Econ. 2005;24(2):341–63.

Ásgeirsdóttir TL, Jóhannsdóttir HM. Income-related inequalities in diseases and health conditions over the business cycle. Health Econ Rev. 2017;7(1):12.

Case A, Lubotsky D, Paxson C. Economic status and health in childhood: the origins of the gradient. Am Econ Rev. 2002;92(5):1308–34.

Cleeren K, Lamey L, Meyer J-H, De Ruyter K. How business cycles affect the healthcare sector: a cross-country investigation. Health Econ. 2016;25(7):787–800.

Bago d’Uva T, Van Doorslaer E, Lindeboom M, O’Donnell O. Does reporting heterogeneity bias the measurement of health disparities? Health Econ. 2008;17(3):351–75.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programme. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. 1994.

Heather EM, Payne K, Harrison M, Symmons DPM. Including adverse drug events in economic evaluations of anti-tumour necrosis factor-α drugs for adult rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of economic decision analytic models. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;32(2):109–34.

Briggs AH, Claxton K, Sculpher MJ. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Briggs A, Sculpher M. An introduction to Markov modelling for economic evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;13(4):397–409.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, Augustovski F, Briggs AH, Mauskopf J, Loder E. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS)—explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR health economic evaluation publication guidelines good reporting practices task force. Value Health. 2013;16(2):231–50.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, Augustovski F, Briggs AH, Mauskopf J, Loder E. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(5):361–7.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, Augustovski F, Briggs AH, Mauskopf J, Loder E. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(3):367–72.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, Augustovski F, Briggs AH, Mauskopf J, Loder E. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. Value Health. 2013;16(2):e1–5.

Claxton K. The irrelevance of inference: a decision-making approach to the stochastic evaluation of health care technologies. J Health Econ. 1999;18(3):341–64.

Vanhout BA, Al MJ, Gordon GS, Ruten FFH. Costs, effects and c/e-ratios alongside a clinical-trial. Health Econ. 1994;3(5):309–19.

Ades AE, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Evidence synthesis, parameter correlation and probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Health Econ. 2006;15(4):373–81.

Ades AE, Sculpher M, Sutton A, Abrams K, Cooper N, Welton N, Lu G. Bayesian methods for evidence synthesis in cost-effectiveness analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24(1):1–19.

Stinnett AA, Mullahy J. Net health benefits: a new framework for the analysis of uncertainty in cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Decis Making. 1998;18(2 Suppl):S68-80.

Barton GR, Sach TH, Doherty M, Avery AJ, Jenkinson C, Muir KR. An assessment of the discriminative ability of the EQ-5Dindex, SF-6D, and EQ VAS, using sociodemographic factors and clinical conditions. Eur J Health Econ. 2007;9(3):237–49.

Weinstein MC, O’Brien B, Hornberger J, Jackson J, Johannesson M, McCabe C, Luce BR. Principles of good practice for decision analytic modeling in health-care evaluation: report of the ISPOR task force on good research practices-modeling studies. Value Health. 2003;6(1):9–17.

Vemer P, Corro Ramos I, van Voorn GA, Al MJ, Feenstra TL. AdViSHE: a validation-assessment tool of health-economic models for decision makers and model users. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(4):349–61.

Doubilet P, Begg CB, Weinstein MC, Braun P, McNeil BJ. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis using Monte Carlo simulation. a practical approach. Med Decis Making. 1985;5(2):157–77.

Briggs AH. Handling uncertainty in cost-effectiveness models. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;17(5):479–500.

O’Brien BJ, Drummond MF, Labelle RJ, William A. In search of power and significance: issues in the design and analysis of stochastic cost-effectiveness studies in health care. Med Care. 1994;32(2):150–63.

Coyle D, Lee KM, O’Brien BJ. The role of models within economic analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20(Supplement 1):11–9.

Sonnenberg FA, Beck JR. Markov models in medical decision making: a practical guide. Med Decis Making. 1993;13(4):322–38.

Barton P, Bryan S, Robinson S. Modelling in the economic evaluation of health care: selecting the appropriate approach. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2004;9(2):110–8.

Drummond M, Barbieri M, Cook J, Glick HA, Lis J, Malik F, Reed SD, Rutten F, Sculpher M, Severens J. Transferability of economic evaluations across jurisdictions: ISPOR Good Research Practices Task Force report. Value Health. 2009;12(4):409–18.

Buxton MJ, Drummond MF, VanHout BA, Prince RL, Sheldon TA, Szucs T, Vray M. Modelling in economic evaluation: an unavoidable fact of life. Health Econ. 1997;6(3):217–27.

Birch S, Gafni A. Information created to evade reality (ICER). Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24(11):1121–31.

Fenwick E, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Representing uncertainty: the role of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. Health Econ. 2001;10(8):779–87.

Briggs AH, Wonderling DE, Mooney CZ. Pulling cost-effectiveness analysis up by its bootstraps: a non-parametric approach to confidence interval estimation. Health Econ. 1997;6(4):327–40.

Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care. 1997;35(11):1095–108.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart K, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 2015.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-ltem Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83.

Golicki D, Jakubczyk M, Graczyk K, Niewada M. Valuation of EQ-5D-5L health states in Poland: the first EQ-VT-based study in central and eastern Europe. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(9):1165–76.

Bleichrodt H. A new explanation for the difference between time trade-off utilities and standard gamble utilities. Health Econ. 2002;11(5):447–56.

Attema AE, Edelaar-Peeters Y, Versteegh MM, Stolk EA. Time trade-off: one methodology, different methods. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(S1):53–64.

Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002;21(2):271–92.

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen MF, Kind P, Parkin D, Bonsel G, Badia X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–36.

Feeny D, Furlong W, Boyle M, Torrance GW. Multi-attribute health status classification systems. Pharmacoeconomics. 1995;7(6):490–502.

Engel L, Bryan S, Whitehurst DGT. Conceptualising ‘benefits beyond health’ in the context of the quality-adjusted life-year: a critical interpretive synthesis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(12):1383–95.

Bansback N, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, Anis A. Using a discrete choice experiment to estimate health state utility values. J Health Econ. 2012;31(1):306–18.

Brown CC, Tilford JM, Payakachat N, Williams DK, Kuhlthau KA, Pyne JM, Hoefman RJ, Brouwer WBF. Measuring health spillover effects in caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder: a comparison of the EQ-5D-3L and SF-6D. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(4):609–20.

Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37(1):53–72.

Devlin NJ, Shah KK, Feng Y, Mulhern B, van Hout B. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Health Econ. 2018;27(1):7–22.

Feeny D, Furlong W, Torrance GW, Goldsmith CH, Zhu Z, Depauw S, Denton M, Boyle M. Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the health utilities index mark 3 system. Med Care. 2002;40(2):113–28.

Oppe M, Devlin NJ, van Hout B, Krabbe PFM, de Charro F. A program of methodological research to arrive at the new international EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value Health. 2014;17(4):445–53.

Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. The time trade-off method: results from a general population study. Health Econ. 1996;5(2):141–54.

Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. Valuing health states: a comparison of methods. J Health Econ. 1996;15(2):209–31.

Barton GR, Sach TH, Avery AJ, Jenkinson C, Doherty M, Whynes DK, Muir KR. A comparison of the performance of the EQ-5D and SF-6D for individuals aged ≥ 45 years. Health Econ. 2008;17(7):815–32.

Versteegh MM, Vermeulen KM, Evers SMAA, de Wit GA, Prenger R, Stolk EA. Dutch tariff for the five-level version of EQ-5D. Value Health. 2016;19(4):343–52.

Jensen CE, Sørensen SS, Gudex C, Jensen MB, Pedersen KM, Ehlers LH. The Danish EQ-5D-5L value set: a hybrid model using cTTO and DCE data. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2021;19(4):579–91.

Al Shabasy SA, Abbassi MM, Finch AP, Baines D, Farid SF. RETRACTED ARTICLE: the EQ-5D-5L valuation study in Egypt. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(5):549–61.

Brazier J. Measuring and valuing health benefits for economic evaluation. 2007.

Lipman SA, Brouwer WBF, Attema AE. The corrective approach: policy implications of recent developments in QALY measurement based on prospect theory. Value Health. 2019;22(7):816–21.

Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care. 2004;42(9):851–9.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, Haes JCJMD, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Ntl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–76.

Arrow KJ. Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. Am Econ Rev. 1963;53(5):941–73.

Layton TJ, Ellis RP, McGuire TG, van Kleef R. Measuring efficiency of health plan payment systems in managed competition health insurance markets. J Health Econ. 2017;56:237–55.

Ellis RP, McGuire TG. Provider behavior under prospective reimbursement. J Health Econ. 1986;5(2):129–51.

Clemens J, Gottlieb JD. Do physicians’ financial incentives affect medical treatment and patient health? Am Econ Rev. 2014;104(4):1320–49.

Blaug M. Where are we now in British health economics? Health Econ. 1998;7(S1):S63–78.

Rothschild M, Stiglitz J. Equilibrium in competitive insurance markets: an essay on the economics of imperfect information. Q J Econ. 1976;90(4);257–80.

Newhouse J. Reimbursing health plans and health providers: efficiency in production versus selection. J Econ Lit. 1996;34(3):1236–63.

Pilny A, Wübker A, Ziebarth NR. Introducing risk adjustment and free health plan choice in employer-based health insurance: evidence from Germany. J Health Econ. 2017;56:330–51.

Ma C-TA. Health care payment systems: cost and quality incentives. J Econ Manag Strategy. 1994;3(1):93–112.

Cooper Z, Gibbons S, Jones S, McGuire A. Does hospital competition save lives? Evidence from the English NHS patient choice reforms. Econ J. 2011;121(554):F228–60.

Decarolis F, Guglielmo A. Insurers’ response to selection risk: evidence from Medicare enrollment reforms. J Health Econ. 2017;56:383–96.

Kessler DP, McClellan MB. Is hospital competition socially wasteful? Q J Econ. 2000;115(2):577–615.

Dafny LS. How do hospitals respond to price changes? Am Econ Rev. 2005;95(5):1525–47.

Layton TJ. Imperfect risk adjustment, risk preferences, and sorting in competitive health insurance markets. J Health Econ. 2017;56:259–80.

Cutler DM, Reber SJ. Paying for health insurance: the trade-off between competition and adverse selection. Q J Econ. 1998;113(2):433–66.

Andrews DWK, Stock JH, Rothenberg TJ. Identification and inference for econometric models: essays in honor of Thomas Rothenberg. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Brosig-Koch J, Hehenkamp B, Kokot J. The effects of competition on medical service provision. Health Econ. 2017;26:6–20.

Gaynor M, Town RJ. Competition in Health Care Markets11We wish to thank participants at the Handbook of Health Economics meeting in Lisbon, Portugal, Pedro Pita Barros, Rein Halbersman, and Cory Capps for helpful comments and suggestions. Misja Mikkers, Rein Halbersma, and Ramsis Croes of the Netherlands Healthcare Authority graciously provided data on hospital and insurance market structure in the Netherlands. David Emmons kindly provided aggregates of the American Medical Association’s calculations of health insurance market structure. Leemore Dafny was kind enough to share her measures of market concentration for the large employer segment of the US health insurance market. All opinions expressed here and any errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. No endorsement or approval by any other individuals or institutions is implied or should be inferred. 2011. p. 499–637.

Selden TM. A model of capitation. J Health Econ. 1990;9(4):397–409.

van Kleef RC, McGuire TG, van Vliet RCJA, van de Ven WPPM. Improving risk equalization with constrained regression. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;18(9):1137–56.

McGuire TG. Physician agency. In: Culyer AJ, Newhouse JP, editors. Handbook of health economics, vol. 1. Elsevier; 2000. p. 461–536.

Gaynor M, Moreno-Serra R, Propper C. Death by market power: reform, competition, and patient outcomes in the National Health Service. Am Econ J Econ Pol. 2013;5(4):134–66.

Ellis RP, McGuire TG. Optimal payment systems for health services. J Health Econ. 1990;9(4):375–96.

Chalkley M, Malcomson JM. Contracting for health services when patient demand does not reflect quality. J Health Econ. 1998;17(1):1–19.

Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ. 2001;20(4):461–94.

Duan N, Manning WG, Morris CN, Newhouse JP. A comparison of alternative models for the demand for medical care. J Bus Econ Stat. 1983;1(2):115–26.

Blough DK, Madden CW, Hornbrook MC. Modeling risk using generalized linear models. J Health Econ. 1999;18(2):153–71.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Greene WH. Econometric analysis. Boston: Prentice Hall; 2012.

Gaynor M, Anderson GF. Uncertain demand, the structure of hospital costs, and the cost of empty hospital beds. J Health Econ. 1995;14(3):291–317.

Duan N. Smearing estimate: a nonparametric retransformation method. J Am Stat Assoc. 1983;78(383):605–10.

Manning WG. The logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and the retransformation problem. J Health Econ. 1998;17(3):283–95.

Tran-Duy A, Boonen A, Kievit W, van Riel PLCM, van de Laar MAFJ, Severens JL. Modelling outcomes of complex treatment strategies following a clinical guideline for treatment decisions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(10):1015–28.

Heckman JJ. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica. 1979;47(1);153–61.

Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. J Health Econ. 2005;24(3):465–88.

Hausman JA. Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica. 1978;46(6):1251–71.

Mullahy J. Much ado about two: reconsidering retransformation and the two-part model in health econometrics. J Health Econ. 1998;17(3):247–81.

Basu A, Rathouz PJ. Estimating marginal and incremental effects on health outcomes using flexible link and variance function models. Biostatistics. 2004;6(1):93–109.

Vita MG. Exploring hospital production relationships with flexible functional forms. J Health Econ. 1990;9(1):1–21.

Breusch TS, Pagan AR. A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica. 1979;47(5):1287–94.

Moscone F, Tosetti E. Health expenditure and income in the United States. Health Econ. 2010;19(12):1385–403.

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconometrics: methods and applications. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48(4):817–38.

Seshamani M, Gray A. Ageing and health-care expenditure: the red herring argument revisited. Health Econ. 2004;13(4):303–14.

Seshamani M, Gray AM. A longitudinal study of the effects of age and time to death on hospital costs. J Health Econ. 2004;23(2):217–35.

Auster R, Leveson I, Sarachek D. The production of health, an exploratory study. J Hum Resour. 1969;4(4):135–58.

Sloan FA, Hsieh CR. Health economics. 2012.

Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM. Too much ado about two-part models and transformation? J Health Econ. 2004;23(3):525–42.

Martin S, Smith PC. Rationing by waiting lists: an empirical investigation. J Public Econ. 1999;71(1):141–64.

Balia S, Brau R. A country for old men? Long-term home care utilization in Europe. Health Econ. 2014;23(10):1185–212.

Mihaylova B, Briggs A, O’Hagan A, Thompson SG. Review of statistical methods for analysing healthcare resources and costs. Health Econ. 2010;20(8):897–916.

Louviere JJ, Hensher DA, Swait JD, Adamowicz W. Stated choice methods. 2010.

Diener A, O’Brien B, Gafni A. Health care contingent valuation studies: a review and classification of the literature. Health Econ. 1998;7(4):313–26.

Louviere JJ, Hensher DA, Swait JD. Stated choice methods: analysis and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

Ryan M, Amaya-Amaya M. ‘Threats’ to and hopes for estimating benefits. Health Econ. 2005;14(6):609–19.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):145–72.

Reed Johnson F, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Mühlbacher A, Regier DA, Bresnahan BW, Kanninen B, Bridges JFP. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16(1):3–13.

Mühlbacher AC, Kaczynski A, Zweifel P, Johnson FR. Experimental measurement of preferences in health and healthcare using best-worst scaling: an overview. Health Econ Rev. 2016;6(1):2.

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(8):661–77.

Clark MD, Determann D, Petrou S, Moro D, de Bekker-Grob EW. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(9):883–902.

Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2003;2(1):55–64.

PubMed Google Scholar

Grosse SD, Pike J, Soelaeman R, Tilford JM. Quantifying family spillover effects in economic evaluations: measurement and valuation of informal care time. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(4):461–73.

Mühlbacher A, Johnson FR. Choice experiments to quantify preferences for health and healthcare: state of the practice. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2016;14(3):253–66.

Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, Johnson FR, Mauskopf J. Conjoint analysis applications in health-a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13.

Klose T. The contingent valuation method in health care. Health Policy. 1999;47(2):97–123.

Mühlbacher AC, Kaczynski A. Making good decisions in healthcare with multi-criteria decision analysis: the use, current research and future development of MCDA. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2015;14(1):29–40.

Sullivan SD, Mauskopf JA, Augustovski F, Jaime Caro J, Lee KM, Minchin M, Orlewska E, Penna P, Rodriguez Barrios J-M, Shau W-Y. Budget impact analysis—principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 Budget Impact Analysis Good Practice II Task Force. Value Health. 2014;17(1):5–14.

Marsh K, Ijzerman M, Thokala P, Baltussen R, Boysen M, Kaló Z, Lönngren T, Mussen F, Peacock S, Watkins J, Devlin N. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health care decision making—emerging good practices: report 2 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19(2):125–37.

Ryan M, Hughes J. Using conjoint analysis to assess women’s preferences for miscarriage management. Health Econ. 1997;6(3):261–73.

Mühlbacher AC, Zweifel P, Kaczynski A, Johnson FR. Experimental measurement of preferences in health care using best-worst scaling (BWS): theoretical and statistical issues. Health Econ Rev. 2016;6(1):5.

Train K. Discrete choice methods with simulation. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

Greene W. The econometric approach to efficiency analysis. In: Fried KLH, Schmidt S, editors. The measurement of productive efficiency. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993.

Cheung KL, Wijnen BFM, Hollin IL, Janssen EM, Bridges JF, Evers SMAA, Hiligsmann M. Using best-worst scaling to investigate preferences in health care. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(12):1195–209.

Hensher DA, Rose JM, Greene WH. Applied choice analysis: a primer. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Mitchell RC, Carson RT. Using surveys to value public goods: the contingent valuation method. In: Resources for the future. 1989.

Hauber AB, González JM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, Prior T, Marshall DA, Cunningham C, Ijzerman MJ, Bridges JFP. Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: a report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19(4):300–15.

Drummond MF, Jefferson TO. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. BMJ. 1996;313(7052):275–83.

Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER. The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54(11):405–18.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Briggs A, Sculpher M, Buxton M. Uncertainty in the economic evaluation of health care technologies: the role of sensitivity analysis. Health Econ. 1994;3(2):95–104.

Henry JA, Rivas CA. Constraints on antidepressant prescribing and principles of cost-effective antidepressant use. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;11(5):419–43.

Henry JA, Rivas CA. Constraints on antidepressant prescribing and principles of cost-effective antidepressant use. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;11(6):515–37.

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27.

Sheldon TA. Problems of using modelling in the economic evaluation of health care. Health Econ. 1996;5(1):1–11.

Drummond M, Torrance G, Mason J. Cost-effectiveness league tables: more harm than good? Soc Sci Med. 1993;37(1):33–40.

Murray CJ, Evans DB, Acharya A, Baltussen RM. Development of WHO guidelines on generalized cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ. 2000;9(3):235–51.

Siegel JE. Recommendations for reporting cost-effectiveness analyses. Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA. 1996;276(16):1339–41.

Ramsey S, Willke R, Briggs A, Brown R, Buxton M, Chawla A, Cook J, Glick H, Liljas B, Petitti D, Reed S. Good research practices for cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials: the ISPOR RCT-CEA Task Force report. Value Health. 2005;8(5):521–33.

Detsky AS. Guidelines for economic analysis of pharmaceutical products. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;3(5):354–61.

Birch S, Gafni A. Changing the problem to fit the solution - Johannesson and Weinstein (mis) application of economics to real-world problems. J Health Econ. 1993;12(4):469–76.

Drummond M. Cost-of-illness studies. Pharmacoeconomics. 1992;2(1):1–4.

Beck JR, Pauker SG. The Markov process in medical prognosis. Med Decis Making. 1983;3(4):419–58.

Torrance GW, Blaker D, Detsky A, Kennedy W, Schubert F, Menon D, Tugwell P, Konchak R, Hubbard E, Firestone T. Canadian guidelines for economic evaluation of pharmaceuticals. Pharmacoeconomics. 1996;9(6):535–59.

Jefferson T, Mugford M, Gray A, Demicheli V. An exercise on the feasibility of carrying out secondary economic analyses. Health Econ. 1996;5(2):155–65.

Jonsson B, Bebbington PE. What price depression? The cost of depression and the cost-effectiveness of pharmacological treatment. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164(5):665–73.

Mason J. The generalisability of pharmacoeconomic studies. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;11(6):503–14.

Torrance GW. Measurement of health state utilities for economic appraisal. J Health Econ. 1986;5(1):1–30.

Torrance GW. Measurement of health state utilities for economic appraisal - a review. J Health Econ. 1986;5(1):1–30.

Culyer AJ. The normative economics of health care finance and provision. Oxf Rev Econ Policy. 1989;5(1):34–58.

Berry C, McMurray J. A review of quality-of-life evaluations in patients with congestive heart failure. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;16(3):247–71.

Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47(2):99–127.

Drummond M, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 1987.

Labelle RJ, Hurley JE. Implications of basing health-care resource allocations on cost-utility analysis in the presence of externalities. J Health Econ. 1992;11(3):259–77.

Atkinson AB. On the measurement of inequality. J Econ Theory. 1970;2(3):244–63.

Green C, Brazier J, Deverill M. Valuing health-related quality of life. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;17(2):151–65.

Torrance GW, Feeny D. Utilities and quality-adjusted life years. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1989;5(4):559–75.

Bleichrodt H, Pinto JL, Maria Abellan-Perpiñan J. A consistency test of the time trade-off. J Health Econ. 2003;22(6):1037–52.

Pliskin JS, Shepard DS, Weinstein MC. Utility functions for life years and health status. Oper Res. 1980;28(1):206–24.

Williams A. Intergenerational equity: an exploration of the ‘fair innings’ argument. Health Econ. 1997;6(2):117–32.

Birch S, Gafni A. Cost effectiveness/utility analyses. J Health Econ. 1992;11(3):279–96.

Wagstaff A. QALYs and the equity-efficiency trade-off. J Health Econ. 1991;10(1):21–41.

Dolan P. Valuing health-related quality of life. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;15(2):119–27.

Dolan P. The measurement of individual utility and social welfare. J Health Econ. 1998;17(1):39–52.

Bleichrodt H, Johannesson M. Standard gamble, time trade-off and rating scale: experimental results on the ranking properties of QALYs. J Health Econ. 1997;16(2):155–75.

Fryback DG, Dasbach EJ, Klein R, Klein BE, Dorn N, Peterson K, Martin PA. The Beaver Dam Health Outcomes Study: initial catalog of health-state quality factors. Med Decis Making. 1993;13(2):89–102.

De Wit GA, Busschbach JJV, De Charro FT. Sensitivity and perspective in the valuation of health status: whose values count? Health Econ. 2000;9(2):109–26.

Williams A. Economics of coronary artery bypass grafting. BMJ. 1985;291(6491):326–9.

Gafni A, Birch S. QALYs and HYEs spotting the differences. J Health Econ. 1997;16(5):601–8.

Mehrez A, Gafni A. Quality-adjusted life years, utility theory, and healthy-years equivalents. Med Decis Making. 1989;9(2):142–9.

Gold MR. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996.

Mauskopf J, Annemans L, Hill AM, Smets E. A review of economic evaluations of darunavir boosted by low-dose ritonavir in treatment-experienced persons living with HIV infection. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;28(S1):1–16.

Laupacis A, Feeny D, Detsky AS, Tugwell PX. How attractive does a new technology have to be to warrant adoption and utilization? Tentative guidelines for using clinical and economic evaluations. CMAJ. 1992;146(4):473–81.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Claxton K, Martin S, Soares M, Rice N, Spackman E, Hinde S, Devlin N, Smith PC, Sculpher M. Methods for the estimation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence cost-effectiveness threshold. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(14):1–504.

Lavelle TA, D’Cruz BN, Mohit B, Ungar WJ, Prosser LA, Tsiplova K, Vera-Llonch M, Lin P-J. Family spillover effects in pediatric cost-utility analyses. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2018;17(2):163–74.

Garber AM, Phelps CE. Economic foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis. J Health Econ. 1997;16(1):1–31.

Gloria MAJ, Thavorncharoensap M, Chaikledkaew U, Youngkong S, Thakkinstian A, Culyer AJ. A systematic review of demand-side methods of estimating the societal monetary value of health gain. Value Health. 2021;24(10):1423–34.

Lakdawalla DN, Doshi JA, Garrison LP, Phelps CE, Basu A, Danzon PM. Defining elements of value in health care—a health economics approach: an ISPOR Special Task Force report [3]. Value Health. 2018;21(2):131–9.

Claxton K, Paulden M, Gravelle H, Brouwer W, Culyer AJ. Discounting and decision making in the economic evaluation of health-care technologies. Health Econ. 2011;20(1):2–15.

Bridges JFP, Onukwugha E, Mullins CD. Healthcare rationing by proxy. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(3):175–84.

McCabe C, Claxton K, Culyer AJ. The NICE cost-effectiveness threshold. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(9):733–44.

Devlin N, Parkin D. Does NICE have a cost-effectiveness threshold and what other factors influence its decisions? A binary choice analysis. Health Econ. 2004;13(5):437–52.

Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Weinstein MC. Updating cost-effectiveness — the curious resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):796–7.

Martin S, Lomas J, Claxton K, Longo F. How effective is marginal healthcare expenditure? New evidence from England for 2003/04 to 2012/13. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2021;19(6):885–903.

Meltzer D. Accounting for future costs in medical cost-effectiveness analysis. J Health Econ. 1997;16(1):33–64.

Neumann PJ, Ganiats TG, Russell LB, Sanders GD, Siegel JE. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. 2016.

Brouwer WBF, Rutten FFH. The missing link: on the line between C and E. Health Econ. 2003;12(8):629–36.

Weinstein MC, Stason WB. Foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis for health and medical practices. N Engl J Med. 1977;296(13):716–21.

Hirth RA, Chernew ME, Miller E, Fendrick AM, Weissert WG. Willingness to pay for a quality-adjusted life year: in search of a standard. Med Decis Making. 2000;20(3):332–42.

Eichler H-G, Kong SX, Gerth WC, Mavros P, Jönsson B. Use of cost-effectiveness analysis in health-care resource allocation decision-making: how are cost-effectiveness thresholds expected to emerge? Value Health. 2004;7(5):518–28.

Annemans L, Beutels P, Bloom DE, De Backer W, Ethgen O, Luyten J, Van Wilder P, Willem L, Simoens S. Economic evaluation of vaccines: Belgian reflections on the need for a broader perspective. Value Health. 2021;24(1):105–11.

Rawlins MD, Culyer AJ. National Institute for Clinical Excellence and its value judgments. BMJ. 2004;329(7459):224–7.

Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Q J Econ. 2004;119(1):249–75.

Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, Bernstein M, Gruber J, Newhouse JP, Allen H, Baicker K. The Oregon health insurance experiment: evidence from the first year*. Q J Econ. 2012;127(3):1057–106.

Manning WG, Newhouse JP, Duan N, Keeler EB, Leibowitz A, Marquis MS. Health insurance and the demand for medical care: evidence from a randomized experiment. Am Econ Rev. 1987;77(3):251–77.

Colin Cameron A, Miller DL. A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. J Hum Resour. 2015;50(2):317–72.

Cheng L, Liu H, Zhang Y, Shen K, Zeng Y. The impact of health insurance on health outcomes and spending of the elderly: evidence from China’s new cooperative medical scheme. Health Econ. 2015;24(6):672–91.

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55.

Cameron AC, Gelbach JB, Miller DL. Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. Rev Econ Stat. 2008;90(3):414–27.

Dillender M. Medicaid, family spending, and the financial implications of crowd-out. J Health Econ. 2017;53:1–16.

Card D, Dobkin C, Maestas N. The impact of nearly universal insurance coverage on health care utilization: evidence from Medicare. Am Econ Rev. 2008;98(5):2242–58.

Dunn A, Knepper M, Dauda S. Insurance expansions and hospital utilization: relabeling and reabling? J Health Econ. 2021;78:102482.

Card D, Dobkin C, Maestas N. Does Medicare save lives?*. Quart J Econ. 2009;124(2):597–636.

Maclean JC, Saloner B. Substance use treatment provider behavior and healthcare reform: evidence from Massachusetts. Health Econ. 2018;27(1):76–101.

Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, Bernstein M, Gruber JH, Newhouse JP, Schneider EC, Wright BJ, Zaslavsky AM, Finkelstein AN. The Oregon experiment — effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1713–22.

Ghosh A, Simon K, Sommers BD. The effect of health insurance on prescription drug use among low-income adults: evidence from recent medicaid expansions. J Health Econ. 2019;63:64–80.

Kolstad JT, Kowalski AE. The impact of health care reform on hospital and preventive care: evidence from Massachusetts. J Public Econ. 2012;96(11–12):909–29.

Ma Y, Nolan A. Public healthcare entitlements and healthcare utilisation among the older population in Ireland. Health Econ. 2017;26(11):1412–28.

Currie J, Gruber J. Health insurance eligibility, utilization of medical care, and child health. Q J Econ. 1996;111(2):431–66.

Abadie A, Diamond A, Hainmueller J. Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. J Am Stat Assoc. 2010;105(490):493–505.

Saloner B, Akosa Antwi Y, Maclean JC, Cook B. Access to health insurance and utilization of substance use disorder treatment: evidence from the Affordable Care Act dependent coverage provision. Health Econ. 2018;27(1):50–75.

Terza JV, Basu A, Rathouz PJ. Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: addressing endogeneity in health econometric modeling. J Health Econ. 2008;27(3):531–43.

Bolin K, Lindgren B, Lundborg P. Informal and formal care among single-living elderly in Europe. Health Econ. 2008;17(3):393–409.

Hoefman RJ, van Exel J, Brouwer WBF. The monetary value of informal care: obtaining pure time valuations using a discrete choice experiment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;37(4):531–40.

Brouwer WBF, Culyer AJ, van Exel NJA, Rutten FFH. Welfarism vs. extra-welfarism. J Health Econ. 2008;27(2):325–38.

Greene WH. Econometric analysis. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 2000.

Wittenberg E, James LP, Prosser LA. Spillover effects on caregivers’ and family members’ utility: a systematic review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(4):475–99.

Gheorghe M, Hoefman RJ, Versteegh MM, van Exel J. Estimating informal caregiving time from patient EQ-5D data: the Informal CARE Effect (iCARE) Tool. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;37(1):93–103.

Coast J, Flynn TN, Natarajan L, Sproston K, Lewis J, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ. Valuing the ICECAP capability index for older people. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(5):874–82.

van den Berg B, Brouwer WBF, Koopmanschap MA. Economic valuation of informal care. Eur J Health Econ. 2004;5(1):36–45.

Viscusi WK, Aldy JE. J Risk Uncertain. 2003;27(1):5–76.

Van Houtven CH, Norton EC. Informal care and health care use of older adults. J Health Econ. 2004;23(6):1159–80.

Al-Janabi H, Flynn TN, Coast J. Development of a self-report measure of capability wellbeing for adults: the ICECAP-A. Qual Life Res. 2011;21(1):167–76.

Koopmanschap MA, van Exel JNA, van den Berg B, Brouwer WBF. An overview of methods and applications to value informal care in economic evaluations of healthcare. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(4):269–80.

Hoefman RJ, van Exel J, Brouwer W. How to include informal care in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(12):1105–19.

Dixon P, Round J. Caring for carers: positive and normative challenges for future research on carer spillover effects in economic evaluation. Value Health. 2019;22(5):549–54.

Koopmanschap MA, Rutten FFH, van Ineveld BM, van Roijen L. The friction cost method for measuring indirect costs of disease. J Health Econ. 1995;14(2):171–89.

Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild CJ, Fuldeore MJ, Ollendorf DA, Wong PK. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11(1):44–7.

Finkler SA. The distinction between cost and charges. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96(1):102–9.

Heywood J, Bouchard J, Cortelli P, Dahlöf C, Jansen JP, Pham S, Hirsch J, Edwards CE, Adams J, Berto P, Brueggenjuergen B, Nyth AL, Lindsay P, Price KL. A multinational investigation of the impact of subcutaneous sumatriptan. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;11(Supplement 1):11–23.

Brouwer WBF, Koopmanschap MA, Rutten FFH. Productivity costs measurement through quality of life? A response to the recommendation of the Washington Panel. Health Econ. 1997;6(3):253–9.

Coukell AJ, Lamb HM. Sumatriptan. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;11(5):473–90.

Cortelli P, Dahlöf C, Bouchard J, Heywood J, Jansen JP, Pham S, Hirsch J, Adams J, Miller DW. A multinational investigation of the impact of subcutaneous sumatriptan. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;11(Supplement 1):35–42.

Zhang W, Bansback N, Anis AH. Measuring and valuing productivity loss due to poor health: a critical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(2):185–92.

Hu XH, Markson LE, Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Berger ML. Burden of migraine in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(8):813–8.

Solomon GD, Price KL. Burden of migraine. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;11(Supplement 1):1–10.

Koopmanschap MA, van Ineveld BM. Towards a new approach for estimating indirect costs of disease. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34(9):1005–10.

Dahlöf C, Bouchard J, Cortelli P, Heywood J, Jansen JP, Pham S, Hirsch J, Adams J, Miller DW. A multinational investigation of the impact of subcutaneous sumatriptan. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;11(Supplement 1):24–34.

Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–97.

Osterhaus JT, Gutterman DL, Plachetka JR. Healthcare resource and lost labour costs of migraine headache in the US. Pharmacoeconomics. 1992;2(1):67–76.

Bouchard J, Cortelli P, Dahlöf C, Heywood J, Jansen JP, Price KL, Pham S, Joseph A, Babiak L. A multinational investigation of the impact of subcutaneous sumatriptan. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;11(Supplement 1):43–50.