Important Tips for Writing an Effective Conference Abstract

Academic conferences are an important part of graduate work. They offer researchers an opportunity to present their work and network with other researchers. So, how does a researcher get invited to present their work at an academic conference ? The first step is to write and submit an abstract of your research paper .

The purpose of a conference abstract is to summarize the main points of your paper that you will present in the academic conference. In it, you need to convince conference organizers that you have something important and valuable to add to the conference. Therefore, it needs to be focused and clear in explaining your topic and the main points of research that you will share with the audience.

The Main Points of a Conference Abstract

There are some general formulas for creating a conference abstract .

Formula : topic + title + motivation + problem statement + approach + results + conclusions = conference abstract

Here are the main points that you need to include.

The title needs to grab people’s attention. Most importantly, it needs to state your topic clearly and develop interest. This will give organizers an idea of how your paper fits the focus of the conference.

Problem Statement

You should state the specific problem that you are trying to solve.

The abstract needs to illustrate the purpose of your work. This is the point that will help the conference organizer determine whether or not to include your paper in a conference session.

You have a problem before you: What approach did you take towards solving the problem? You can include how you organized this study and the research that you used.

Important Things to Know When Developing Your Abstract

Do your research on the conference.

You need to know the deadline for abstract submissions. And, you should submit your abstract as early as possible.

Do some research on the conference to see what the focus is and how your topic fits. This includes looking at the range of sessions that will be at the conference. This will help you see which specific session would be the best fit for your paper.

Select Your Keywords Carefully

Keywords play a vital role in increasing the discoverability of your article. Use the keywords that most appropriately reflect the content of your article.

Once you are clear on the topic of the conference, you can tailor your abstract to fit specific sessions.

An important part of keeping your focus is knowing the word limit for the abstract. Most word limits are around 250-300 words. So, be concise.

Use Example Abstracts as a Guide

Looking at examples of abstracts is always a big help. Look at general examples of abstracts and examples of abstracts in your field. Take notes to understand the main points that make an abstract effective.

Avoid Fillers and Jargon

As stated earlier, abstracts are supposed to be concise, yet informative. Avoid using words or phrases that do not add any specific value to your research. Keep the sentences short and crisp to convey just as much information as needed.

Edit with a Fresh Mind

After you write your abstract, step away from it. Then, look it over with a fresh mind. This will help you edit it to improve its effectiveness. In addition, you can also take the help of professional editing services that offer quick deliveries.

Remain Focused and Establish Your Ideas

The main point of an abstract is to catch the attention of the conference organizers. So, you need to be focused in developing the importance of your work. You want to establish the importance of your ideas in as little as 250-300 words.

Have you attended a conference as a student? What experiences do you have with conference abstracts? Please share your ideas in the comments. You can also visit our Q&A forum for frequently asked questions related to different aspects of research writing, presenting, and publishing answered by our team that comprises subject-matter experts, eminent researchers, and publication experts.

best article to write a good abstract

Excellent guidelines for writing a good abstract.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

AI vs. AI: How to detect image manipulation and avoid academic misconduct

The scientific community is facing a new frontier of controversy as artificial intelligence (AI) is…

- Diversity and Inclusion

Need for Diversifying Academic Curricula: Embracing missing voices and marginalized perspectives

In classrooms worldwide, a single narrative often dominates, leaving many students feeling lost. These stories,…

- Career Corner

- Trending Now

Recognizing the signs: A guide to overcoming academic burnout

As the sun set over the campus, casting long shadows through the library windows, Alex…

Reassessing the Lab Environment to Create an Equitable and Inclusive Space

The pursuit of scientific discovery has long been fueled by diverse minds and perspectives. Yet…

- Reporting Research

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without AI-assistance

Imagine you’re a scientist who just made a ground-breaking discovery! You want to share your…

7 Steps of Writing an Excellent Academic Book Chapter

When Your Thesis Advisor Asks You to Quit

Virtual Defense: Top 5 Online Thesis Defense Tips

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

How to Write a Conference Abstract

- Finding Conferences

General Advice

Things to keep in mind when preparing your abstract, where to get writing inspiration, example resources.

- How to Write a Scientific or Research Abstract

- How to Write a Case Report Abstract

- How to Write a Quality Improvement Project Abstract

- Writing Tips

- Reasons for Rejection

This page provides general guidance on how to prepare for the common types of conference abstracts. Use tabs for more specific information on writing Scientific, Case Report, and Quality Improvement conference abstracts.

Submitting a conference abstract is competitive

Know the rules:

- Follow the rules for abstract submission, don't give the reviewers any reason to toss out your abstract

- Pay attention to word count limits, section headings, how to format your name, etc.

Know the timeline and deadline:

- Get your writing goal calendar together at the start to reduce stress

- Know what is expected at each step of writing

- Give yourself enough time for writing and re-writing

- There can be a range of turnaround times

Look for an archive of past abstracts from the conference to keep your abstract on track.

- Web of Science This link opens in a new window Includes a database called Conference Proceedings Citation Index. It includes conference proceedings from 1994 to the present. Nearly 400,000 conference proceedings are added to the index each year. You can search by topic, author, conference, year, and use various filters to focus in what you are searching for.

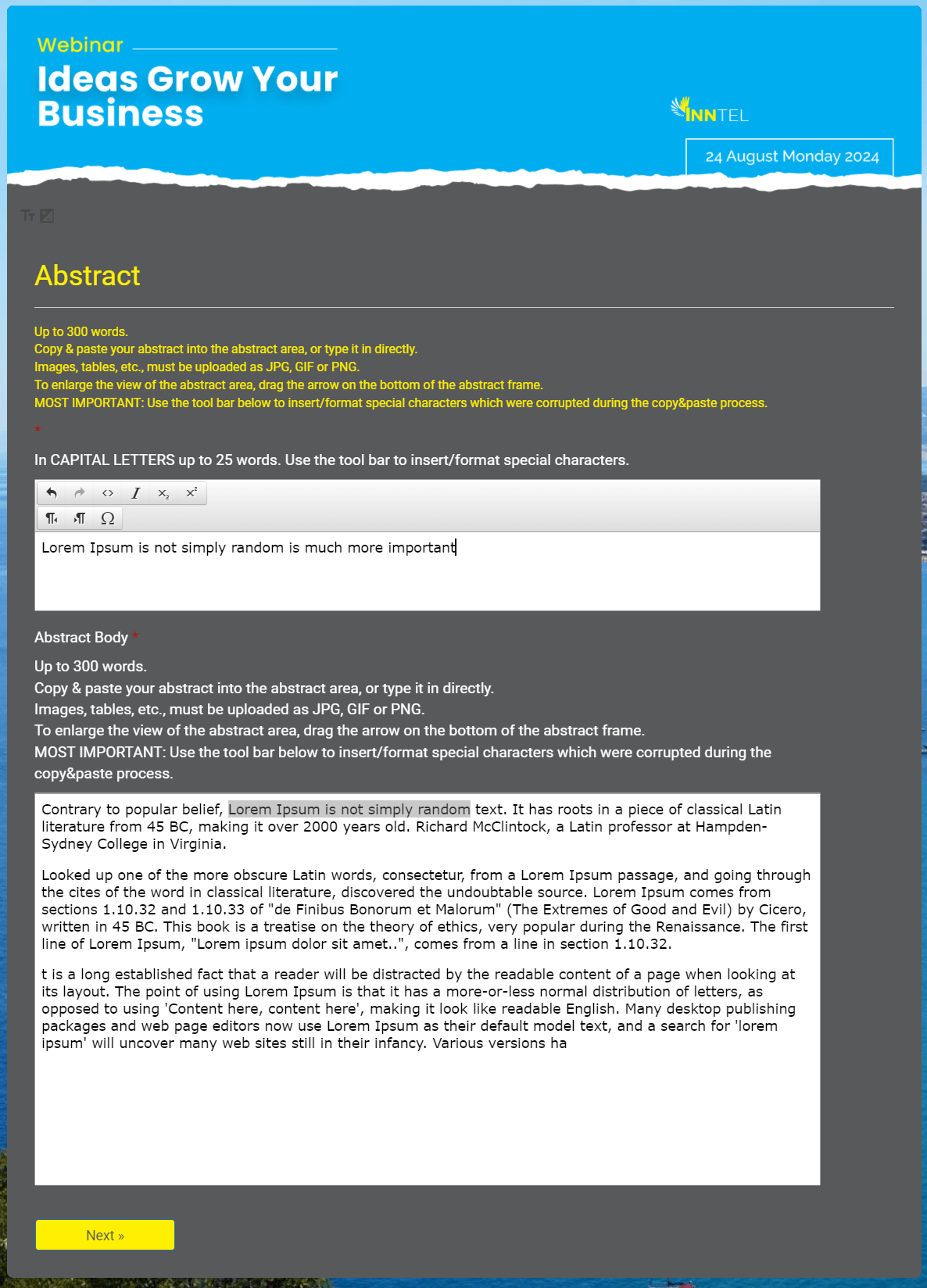

Here are some examples of what abstract submission guidelines look like:

- General abstracts submission guidelines

- General abstract submission FAQs

- Abstract submission checklist

- << Previous: Finding Conferences

- Next: How to Write a Scientific or Research Abstract >>

- Last Updated: Feb 14, 2024 8:15 AM

- URL: https://guides.temple.edu/howtowriteaconferenceabstract

Temple University

University libraries.

See all library locations

- Library Directory

- Locations and Directions

- Frequently Called Numbers

Need help? Email us at [email protected]

ACS Student Magazine

How To Write a Professional, Polished Scientific Abstract

In the science world, you make your first impression long before you meet anyone in person. How? Through an abstract—that brief, powerful paragraph that describes your research.

Whether it’s for a conference presentation, journal article, grant proposal, or dissertation, the abstract—as well as the title and the author listing—is the first window into the scope and purpose of your work. It tells the reader about the content of your research and the results of your experimentation. And it tells the reviewer or editor which session or journal you belong in, so potential collaborators can find you.

To show that your research is relevant and worth learning more about, you need to write a polished and professional abstract. Here’s how to write titles, author listings, and text for abstracts that are informative and professional in any presentation format.

Keep your title short and descriptive. Don’t oversell or sensationalize your work; simply state what it is. If you absolutely must give detail, you can add a subtitle, using a colon to separate it from the main title.

Reviewers start with the title to make sure they have you in the right session. For example, “C–H bond functionalization in long-chain alkanes” will be placed in an Organic Chemistry session, whereas “Iron oxide catalysts for hydrocarbon C–H bond functionalization” will be placed in an Inorganic Chemistry session.

Scientists use titles to see whether your work is relevant to them. If you write “Curing genetic diseases through molecular modeling”,

you had better have the clinical trial data to back up your claim.

“Molecular basis of multiple mitochondrial dysfunctions syndrome: Impact of substitution on the protein NFU1” will be of interest to other biochemists studying protein functionality.

Here are some additional technical tips for titles of scientific abstracts:

- Start with an adjective, a noun, or a verb. Never start with an article (e.g., “The”, “A”, or “An”).

- Do not end with punctuation; your title is not a sentence.

- Use plain text (no bold, italics, or special fonts).

- Use sentence case. The only words that need to be capitalized are the first word of the title, the first word after a colon, and any proper nouns, acronyms (e.g., FT-IR), or element symbols in formulas (e.g., NaOH).

The authors and affiliations

List the names and affiliations of everyone who contributed to the work, starting with you. If you are submitting the abstract for an oral or poster presentation, you are the presenting author and your name goes first. If you are submitting an article to a journal, your name will either go first or be highlighted in some fashion. (It depends on the protocols of the journal and the preferences of your research advisor.)

You also need to include your research advisor. With the exception of some very unusual circumstances, your project is part of a larger body of research that is coordinated by your advisor. Your advisor helped you to develop your project, guided your interpretation of the results, and provided you with laboratory space and supplies, and your results will be incorporated into your advisor’s overall body of research. So your advisor gets credit.

You should include anyone else who contributed significantly to the research, such as a labmate who performed some of the work or a colleague in another lab who assisted you with analyses.

Include your affiliation as well as that of your coauthors. Your affiliation is your school. For clarity, be sure to cite the complete name of your school, not an abbreviation or short form (e.g., use “California Institute of Technology”, not “Caltech”). Unless you are collaborating with a group outside of your department or doing research at another institution, your coauthors will have the same affiliation as you.

Abstracts are high-level summaries. They are typically no longer than 2000 characters (preferably shorter than 1000 characters). Using complete sentences, describe why the work was done, what types of experiments were completed, and the results. You are writing for other scientists, so you do not need to explain common scientific terms, only techniques specific to your research. This guideline will help you stay within the character limit.

Keep it simple. Experimental parameters, data, graphs, references, and extensive discussion of the results are for your presentation or article. If you find yourself trying to include these details, you are saying too much. Some abstract submission systems, like the ACS Meeting Abstracts Programming System (MAPS), do not accept graphs, figures, or references, so you run the risk of being rejected from a symposium. There are instances when a graph or figure is necessary, but they are the exception.

Here are some key elements to keep in mind as you are writing:

- Why is your research important?

- What problem does your work attempt to solve?

- What specific approaches did you take or methods did you use?

- What were the results?

- How does your research add to the body of knowledge?

Keeping the abstract general helps with the challenge: having to submit your abstract before you complete your research. This is especially common if you are presenting at a technical conference, like an ACS national meeting, where submissions are due six to seven months before the conference. In this case, you can submit a short abstract of the work you are planning to do, and end with, “The results of this work will be presented.”

Write in the third person using passive voice (e.g., “Microporous silicates were synthesized” rather than “I synthesized a series of microporous silicates”). In the scientific community, this is the more professional way to present research.

Finally, proofread, proofread, and proofread again. Make sure that your sentences are clear and error-free. Have a peer, grad student, or experienced labmate (or two) review your abstract for clarity, grammar, and punctuation. Also, have your research advisor review and approve it. This work represents your advisor’s lab, so your advisor should have a say in what you report.

Writing abstracts is a skill that is essential to both the research world and the business world (where it’s called an “executive summary”). Start developing this skill now to set yourself up for success later.

ABSTRACT CHALLENGE

See if you can spot the errors in this online quiz.

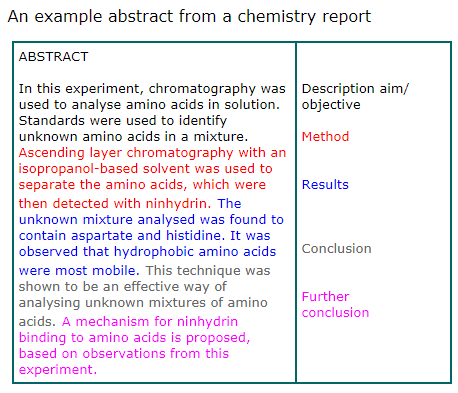

Anatomy of an Awesome Abstract

A professional abstract summarizes the scope of your research and shows why your study is worth learning more about. Check out the infographic below for a breakdown of what should be included in your abstract, and click on the image to access the PDF.

How to Write an Undergraduate Abstract, by Elzbieta Cook. www.acs.org/content/acs/en/meetings/national-meeting/agenda/student-program/undergraduate-abstract.html

About the Author

Blake Aronson is a program manager for ACS Student Communities. She works with undergraduate programs at two- and four-year institutions, as well as the SCI Scholars Program and other ACS initiatives.

More Careers Articles

From marine biology to chemical manufacturing, we talked to nanoscientists about how they tackle climate challenges with big innovations using the tiniest tools.

Past ACS President Katie Hunt shares her insights on industry vs. academic careers, sustainability in industry, and the most important question you can ask.

How do you know if you have good interpersonal skills? And how do you prove to a potential employer that years of group work were not in vain? Find out.

What started as a passion for inspiring students from underrepresented backgrounds turned this teacher into a kitchen-chemistry household name. Learn about his surprising career.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

American Society for Microbiology

Tips for writing your first conference abstract.

July 17, 2019

Communicating your research is an important part of being a scientist. While submitting an abstract to a national conference can seem overwhelming, it is one of the best ways to communicate your science and get your research in front of a large audience.

Students interested in learning how to write an abstract should review these helpful tips that describe components of a competitive abstract . Also review the below suggestions from ASM education specialist, Dr. Christopher Skipwith, on best practices for preparing your first abstract for a scientific conference.

Read the Instructions

Although this may be obvious, many times, abstracts are rejected because they are missing key components. Be sure to familiarize yourself with the submission requirements before starting your abstract.

Understand the Target Audience

Who will be reading your abstract? Whether you are submitting to a field-specific or general conference, make sure the language you use can be easily understood by your target audience. Field-specific language may be appropriate for specialized conferences, however plain language must be used for conferences that cover a wide range of fields.

When using acronyms, remember to always provide the full phrase on the first mention accompanied by the acronym in parenthesis.

Clearly State the Hypothesis/Statement of Purpose

Not every project has a hypothesis, but all projects have a purpose. Figure out the research questions you are trying to answer and include the hypothesis or purpose of your research in the abstract. It is imperative to communicate your hypothesis/statement of purpose clearly so the reader can get a better context of your research goals and understand the importance of your research.

Tie Results and Conclusions Back to the Hypothesis/Statement of Purpose

After you have written your results and conclusions, go back to your hypothesis/statement of purpose. Do the results and conclusions clearly support your research purpose? What did the results say about your hypothesis? Make sure the links between these components are obvious to the reader.

Review, Then Review Again

Re-read your abstract against a copy of the abstract guidelines. As you go through, check off each guideline to ensure your abstract is complete. Remember that even if it has all the requirements, a poorly written abstract will not be accepted. Then have multiple people, including your Principal Investigator, read it over. Incorporate their feedback to ensure a strong submission.

The Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minority Students (ABRCMS) provides poster and oral presentation opportunities for undergraduates, postbaccalaureates, and masters students.

- Undergraduate Student

- Communicating Science

- Graduate Student

- Professional Development

- Scientific Writing

Author: Christopher Skipwith, Ph.D.

ASM Microbe 2024 Registration Now Open!

Discover asm membership, get published in an asm journal.

How to Structure a Scientific Article, Conference Poster and Presentation

- First Online: 22 April 2022

Cite this chapter

- Sarah Cuschieri 2

480 Accesses

9 Altmetric

The main aim of any research endeavor is to disseminate research findings among the scientific community and enrich scientific knowledge. The two most common scientific dissemination modes are journal articles and conference proceedings. Whichever route you decide to follow, the scientific writing that needs to be partaken typically follows the IMRaD format, i.e., Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion-Conclusion. This format is applicable for abstracts (unless an unstructured abstract is specifically required), scientific research articles, and conference poster or oral presentations. Understanding the importance of each IMRaD section along with the role of a clear and informative title is your road to success. This also applies to proper citation of other people’s work, ideas, and thoughts. This chapter will guide you, through a stepwise approach, to understand the various elements that make up a successful scientific article, an abstract, a conference poster, and an oral presentation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG et al (2013) SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 158:200

Article Google Scholar

Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG et al (2013) The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Glob Adv Heal Med 2:38

Grech V (2018a) WASP (Write a Scientific Paper): preparing a poster. Early Hum Dev 125:57–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.06.007

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Grech V (2018b) WASP (Write a Scientific Paper): optimisation of PowerPoint presentations and skills. Early Hum Dev 125:53–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.06.006

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF et al (2010) CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol 63:e1–e37

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ et al (2014) Standards for reporting qualitative research. Acad Med 89:1245–1251

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al (2007) Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335:806

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, University of Malta, Msida, Malta

Sarah Cuschieri

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cuschieri, S. (2022). How to Structure a Scientific Article, Conference Poster and Presentation. In: A Roadmap to Successful Scientific Publishing. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99295-8_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99295-8_3

Published : 22 April 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-99294-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-99295-8

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How To Write A Scientific Abstract (11 Tips)

You put all this hard work into preparing your scientific paper.

But if you want your peers, colleagues, or students to read it, you need to put some more effort into crafting an effective abstract. Let’s find out how to do it.

What is a scientific abstract? A definition.

It’s a summary of a scientific paper, intended to summarize the research project, its purpose, achieved results, and conclusions. It gives a good idea of what’s inside the paper, but you have to read the whole thing. A more formal definition from Wikipedia: An abstract is a summary of a research article, thesis, review, conference proceeding, or any in-depth analysis of a particular subject and is often used to help the reader quickly find out the paper’s purpose.

A good abstract has the following qualities:

- 1. Summarize the findings in your paper

- 2. Persuades the reader to download and read the full article

- 3. If it’s prepared for a conference, it gets you selected for a talk and makes the audience curious about your subject

- 4. It presents the exact results of your research, not only a list of topics

- 5. It’s composed of an introduction, a body, and a conclusion

- 6. Usually, it’s no longer than 250 words (but may go up to 500), and it’s written in a 12-size font

- 7. It should be accessible to a general reader (you go into the nitty-gritty in the paper itself)

- 8. It communicates the main point of your research, why it matters, and what you concluded

- 9. If you co-authored the paper with someone else, you mention them in the abstract

- 10. If you’ve been mentored by any members of your faculty while doing research, you mention them as well

- 11. In it, you share the methods you used, and the results you achieved, and finish with a conclusion

“Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.” – Carl Sagan

Types of abstracts for different uses:

- For an article in a scientific publication

- For a conference presentation (academic poster)

- Graphical abstract, video abstract (they include visuals but follow the same basic format shown below).

Here’s a simple example of an abstract:

Writing an abstract for an article in a scientific publication

Here are a couple of rules to follow if you’re preparing to submit your work for publication:

- The title of the paper should be clear but enticing

- The inclusion of data is acceptable (but only in summary)

- Try not to use citations or URLs in the abstract. Leave that for the paper itself

- Use clear language, don’t overcomplicate, and be straightforward

- Before submitting, give it one more final edit

- Check the spelling, grammar, and syntax. You can use Grammarly for that.

- After the title and the introduction, say why the reader should care about this research (motivation)

- Make sure you include the right keywords at the bottom of the abstract. They will make your paper more searchable in the science database, which makes it easier for it to get found and receive citations. Answer this question when thinking about keywords: what would someone type in the search engine to find your paper?

Follow a proven format:

- The problem, challenge, or a question

- Why should you care

- Methods used

- Results achieved

- Conclusion and steps forward

- (Usually around 250 words)

Writing an abstract for a conference presentation (poster)

A good abstract can go a long way in advancing your scientific career. The organizers of the event will review it in every detail and select your article for a presentation based on its quality. It all depends on the caliber of the event, but for the well-attended ones, your abstract will make or break your chances of presenting to a big audience. People who approve articles for presentation want the audience to be engaged and will accept only the highest quality material .

Here are a few guidelines for preparing a solid conference abstract:

- People in the audience won’t have access to your full article, so you only have the abstract to present your research succinctly.

- Usually, there’s a strict limit of words you can use, so you need to plan how to pique the interest of the audience with a limited amount of space.

- The abstract is like a business card or a short persuasive letter that will determine if you get the spotlight or not. A perfect match of scientific understanding and persuasive skills is required.

- Ask about the exact format specifications and check examples of abstracts from previous years.

- Sometimes you’ll have to submit the abstract months before the actual event. You’ll still need to come up with something to make it sound interesting. And then make sure you send the updated version before the conference.

Here you can find six examples of scientific abstracts written for a presentation. And here you can find a great article, about abstracts for a presentation, written by a Ph.D. with a 90% acceptance rate. And if you need to create a poster out of your abstract, here’s a great guide you can check as well as some amazing examples.

Here’s another good example from humanities:

Pagel, J. F.; Vann, B. H. The effects of dreaming on awake behavior. Dreaming: Journal of the Association for the Study of Dreams. Vol 2(4)229-237, Dec 1992. Abstract: Reports of the incorporation of dream mentation into a spectrum of awake behaviors were obtained from a heterogeneous awake population group through the utilization of self-reporting questionnaires (N=265). Results were analyzed to determine associations between age, gender, race, and the dream use variables. Significantly higher dream use was found in females for a majority of behaviors, and a negative correlation was found between increasing age and all dream questions studied. No significant racial/ethnic variation was found in the responses of the sample. These findings suggest that such a sociological approach to the study of the effects of dream mentation on awake behavior can provide insight into the sleep/dream states. Keywords: dream; dream use; behavior; age; gender; race; sleep; questionnaire. Here are more examples of abstracts from the University of Wisconsin. And from another scientific paper about dreams (with the actual paper included below).

As you can see, writing a solid summary of your scientific paper is straightforward. I hope that now you have a better understanding of the process, and will accomplish great things in the scientific community. Next up, you may want to explore a list of the top educational book publishers .

Get your free PDF report: Download your guide to 100+ AI marketing tools and learn how to thrive as a marketer in the digital era.

Rafal Reyzer

Hey there, welcome to my blog! I'm a full-time entrepreneur building two companies, a digital marketer, and a content creator with 10+ years of experience. I started RafalReyzer.com to provide you with great tools and strategies you can use to become a proficient digital marketer and achieve freedom through online creativity. My site is a one-stop shop for digital marketers, and content enthusiasts who want to be independent, earn more money, and create beautiful things. Explore my journey here , and don't miss out on my AI Marketing Mastery online course.

How to write a good abstract for a scientific paper or conference presentation

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Psychopharmacology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

- PMID: 21772657

- PMCID: PMC3136027

- DOI: 10.4103/0019-5545.82558

s of scientific papers are sometimes poorly written, often lack important information, and occasionally convey a biased picture. This paper provides detailed suggestions, with examples, for writing the background, methods, results, and conclusions sections of a good abstract. The primary target of this paper is the young researcher; however, authors with all levels of experience may find useful ideas in the paper.

Keywords: Abstract; preparing a manuscript; writing skills.

Writing an Abstract for a Conference

January 2, 2022 8 min read

January 2, 2022 | 8 min read

Writing Abstracts for a Conference

An "abstract" for an academic conference is a short summary of the scientific research you are involved in. While abstracts generally have a standard format and include more or less the same information and in a similar layout, each conference may have its unique requirements. It is, therefore, essential that you make yourself aware of that conference's specific requirements when planning to submit an abstract for a conference.

Abstracts are submitted to the conference organizers by or on behalf of one of the research authors. This person is called the "presenting author". The presenting author submits the abstract because they wish to present their work at the conference. The conference then has a committee that decides and selects the abstracts that most fit the topic and purpose of the conference. These chosen abstracts are then scheduled into the conference.

Presenting at a conference is a privilege; so typically, the presenter registration fees are not waived. On the contrary, many conferences will not review an abstract if the person who has submitted it is not registered to attend the conference or has not paid an abstract submission fee.

How to Write a Research Abstract for a Conference.

Conferences are essential academic activities pursued by researchers worldwide. They drive the advancement of knowledge through presentations and discussions among their participants. They also help researchers from different regions and backgrounds to connect, thereby enabling future research cooperation.

The Benefits of Presenting at an Academic Conference

Researchers who present their research at conferences open the door to multiple opportunities to advance their research. They receive direct feedback, new ideas, and advice from influential scientific community members and colleagues.

On both a personal and professional level, presenters receive attention from influential members of the community that can benefit them in the future. In addition to this, presenters gain the opportunity to build their reputation and to add colleagues, future employers, and future collaborators to their network.

Participating in an international conference can be expensive. To present at a conference, participants must have ways to fund their conference participation, including travel and accommodation expenses. Unfortunately, the conference organizers usually will not cover presenters' costs and will not even exempt presenters from the conference registration free. However, presenters can apply for grants from any academic institution they are affiliated with. Associations may also have funds to help members present in conferences. In addition, many organizations will generally fund conference participation for their employees.

To begin with, you need to prepare and submit an abstract of your research.

1. What is a Conference Abstract?

As mentioned above, a conference abstract is a limited-length outline of an oral presentation or poster that you intend to present at a conference.

A conference abstract includes:

Article abstract vs. conference abstract.

Article abstracts are submitted alongside the full article or paper and are therefore evaluated alongside the full paper. In the case of academic journals, if the abstract is not perfect, but the editors liked the article, they can request that the author fix the abstract. However, this is not the case with a conference; a conference abstract is submitted by itself and judged by itself.

On the other hand, many conferences will accept poor abstracts because they need to fill slots to make their conference bigger. In a conference, the quality of your abstract as evaluated by the organizer will affect the type of presentation (live or poster) and the scheduling of the presentation provided to you.

2. Processing and Reviewing Abstracts in Conferences.

Conference abstracts are processed and reviewed in several steps. These are listed below:

- Conference name.

- Conference date and location.

- Conference topics.

- Abstract submission guidelines.

- Abstract submission deadlines.

- Abstract processing fees.

- Potential speakers submit their abstracts.

- The conference secretariat receives the abstracts. They then ensure the abstract is valid, complete, and follows the guidelines

The secretariat is responsible for assigning the abstract for review by one or more reviewers. The secretariat or the Abstract Management System will select the reviewers based on the abstract topic and rules defined by the conference organizers and the conference chairperson.

In small conferences, the chairperson will review all the abstracts and decide how to include them in the conference agenda.

In other conferences, a group of reviewers (known as the scientific committee) will review and give a grade to each abstract. Each reviewer will grade each abstract independently. Depending on the specific conference, each reviewer may also suggest filing the abstract under a different conference topic, recommend the presentation type (poster or oral), or ask the author to revise the abstract (revise and resubmit).

There are two main types of review processes:

- After all reviewers complete their review, the abstract management system will calculate the average score of each abstract. The chairperson will then make the final decision regarding the abstracts.

- The secretariat will communicate this decision to the abstract submitters and will guide them about the next steps they should take.

- The conference chairperson, along with the organizers, will schedule the accepted abstracts to a conference session.

Abstract review criteria.

Most conferences aks reviewers to review and grade abstracts based on similar criteria.

Common abstract grading factors:

- Relevance of the abstract to the conference.

- Originality.

- Significance.

- Adherence to abstract submission guidelines.

Conference organizers may have additional goals, so they may consider additional factors.

Example of additional abstract selection factors:

- Encouraging young researchers

- Ethnic diversity

- Author reputation

3. Challenges in Writing a Conference Abstract.

Writing a conference abstract is challenging since it is a limited-length text that needs to appeal to all the different groups of people involved in the conference. In addition, each group has somewhat other interests.

The main groups are the conference organizers, reviewers, and conference attendees. Organizers decide if the abstract is good enough before assigning it to the reviewers, and after the abstract is accepted, they choose when to schedule it. Reviewers score the abstract based on conference criteria such as fitting the conference topics and scientific significance. Attendees need to have an interest in attending the presentation after reading the abstract.

4. Getting Ready to Write the Abstract.

Before writing your abstract, check if a preliminary conference agenda has been published. There may be a list of sessions that you can aim to present and topics that get more time on the agenda.

How many users enter the website, where they are from, the browser they use, how many pages they visit, the time they spend on each page, and more.

Remember to check the conference's abstract submissions guidelines.

Things to note:

- Submission deadlines.

- Topic list.

- Abstract length limit.

- Are tables and figures permitted?

- Review criteria.

Check for scientific committee members and chairpersons.

Search Abstract Examples

Check abstracts submitted to the conference over the last years can help get an idea of what is required in the abstract.

If previous year abstracts are not available online, ask your colleges if they have a copy of the conference abstracts book from previous years. Attempt to figure out what made each one work.

5. Writing the Abstract Title.

The title is one sentence that describes your research and presentation. It is probably the most important sentence in your abstract because:

- It is the first impression of people reviewing your abstract.

- It will appear in the conference agenda with a possible link to your abstract.

- More people will only read the title than read the abstract or attend the presentation.

- People remember and recite your article by its title.

A good title is a clear, easily understood, and attention-grabbing sentence that describes your research and highlights its importance. A good title attracts attendees to read the full abstract or attend the oral presentation.

To make your title clear, straightforward, and short:

- Keep it under 14 words.

- Avoid using obvious words such as "Research on", "Results of ", "Investigation", "Role of".

- Remove unnecessary words such as "the".

- Remove words that give no information to the readers.

- Avoid special symbols and units.

- Avoid complicated words, uncommon abbreviations, and too much jargon.

Writing the abstract title step by step

- Explain what your research and presentation are about in two or three sentences. Do not reveal the conclusions.

- Shorten and combine the sentences into one title.

- Remove unnecessary words.

- Review and refine the title.

- Make sure that it is informative, clear, and interesting.

6. Writing the Abstract Body.

The abstract body is the main part of the abstract and typically has 200 to 500 words.

General tips:

- Concentrate on the research Objective, Methods, Results, and Consultation (OMRC).

- Keep sentences brief and concise.

- References are not required in the abstract.

- Keep background information to a minimum.

- Do extensively referring to other works.

- Do not define terms.

- Avoid asking questions and not answering them.

- Make sure your abstract is error-free before submitting it.

An abstract body typically has four parts abbreviated as OMRC.

Abstract body parts (OMRC):

- Conclusions

Let us have a look at the main parts of the abstract:

Part 1 - Objective and Purpose

This part is typically two to four sentences and covers: background information, the reason for doing the research, the problems or questions the research aims to solve, and the overall topic of the research. It also outlines why your research is important and how difficult it is.

Typically, this part of the body will end with a sentence that describes the purpose of the research. For example, "The purpose of this study was to _____."

Examples of abstract purpose:

- Examining a new topic. Remember to outline why you are examining this new topic.

- Filling a gap in previous research.

- Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data.

- Resolving a dispute within the literature.

Part 2 - Methods

When doing the research, what research methods were used? How extensive was the investigation? Remember to explain who the participants are, what the researchers measured, and what tools they used. Was the research empirical or theoretical? What sources of information did the research rely on?

This section should not include what the researchers expected to find.

Part 3 - Results

This section describes the research findings.

In the case that the research does not have results yet, you should describe the preliminary data or results with some statistical work. If you expect to have results before the conference, the abstract can include a note that a finalized version of the abstract will be updated at a later date before the conference.

Part 4 - Conclusion

This section explains the meaning of the findings, the importance of the findings, and their implications.

An abstract that does not include a conclusion or result section is called a descriptive abstract. If the abstract has a conclusion, it is called an informative abstract.

Participating in an international academic conference potentially brings multiple opportunities. Presenting at a conference adds a significant boost to these opportunities and can also help fund participation. Writing a good abstract is key to making this possible.

Please share your tips with us on Twitter. Did you find any part of this article helpful? Please share it with your colleagues and friends.

Read more about the Eventact Software for abstracts submission and review here.

Review Management

Event Websites

Event Professionals

- About the LSE Impact Blog

- Comments Policy

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

- Subscribe to the Impact Blog

- Write for us

- LSE comment

January 27th, 2015

How to write a killer conference abstract: the first step towards an engaging presentation..

34 comments | 132 shares

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Helen Kara responds to our previously published guide to writing abstracts and elaborates specifically on the differences for conference abstracts. She offers tips for writing an enticing abstract for conference organisers and an engaging conference presentation. Written grammar is different from spoken grammar. Remember that conference organisers are trying to create as interesting and stimulating an event as they can, and variety is crucial.

Enjoying this blogpost? 📨 Sign up to our mailing list and receive all the latest LSE Impact Blog news direct to your inbox.

The Impact blog has an ‘essential ‘how-to’ guide to writing good abstracts’ . While this post makes some excellent points, its title and first sentence don’t differentiate between article and conference abstracts. The standfirst talks about article abstracts, but then the first sentence is, ‘Abstracts tend to be rather casually written, perhaps at the beginning of writing when authors don’t yet really know what they want to say, or perhaps as a rushed afterthought just before submission to a journal or a conference.’ This, coming so soon after the title, gives the impression that the post is about both article and conference abstracts.

I think there are some fundamental differences between the two. For example:

- Article abstracts are presented to journal editors along with the article concerned. Conference abstracts are presented alone to conference organisers. This means that journal editors or peer reviewers can say e.g. ‘great article but the abstract needs work’, while a poor abstract submitted to a conference organiser is very unlikely to be accepted.

- Articles are typically 4,000-8,000 words long. Conference presentation slots usually allow 20 minutes so, given that – for good listening comprehension – presenters should speak at around 125 words per minute, a conference presentation should be around 2,500 words long.

- Articles are written to be read from the page, while conference presentations are presented in person. Written grammar is different from spoken grammar, and there is nothing so tedious for a conference audience than the old-skool approach of reading your written presentation from the page. Fewer people do this now – but still, too many. It’s unethical to bore people! You need to engage your audience, and conference organisers will like to know how you intend to hold their interest.

Image credit: allanfernancato ( Pixabay, CC0 Public Domain )

The competition for getting a conference abstract accepted is rarely as fierce as the competition for getting an article accepted. Some conferences don’t even receive as many abstracts as they have presentation slots. But even then, they’re more likely to re-arrange their programme than to accept a poor quality abstract. And you can’t take it for granted that your abstract won’t face much competition. I’ve recently read over 90 abstracts submitted for the Creative Research Methods conference in May – for 24 presentation slots. As a result, I have four useful tips to share with you about how to write a killer conference abstract.

First , your conference abstract is a sales tool: you are selling your ideas, first to the conference organisers, and then to the conference delegates. You need to make your abstract as fascinating and enticing as possible. And that means making it different. So take a little time to think through some key questions:

- What kinds of presentations is this conference most likely to attract? How can you make yours different?

- What are the fashionable areas in your field right now? Are you working in one of these areas? If so, how can you make your presentation different from others doing the same? If not, how can you make your presentation appealing?

There may be clues in the call for papers, so study this carefully. For example, we knew that the Creative Research Methods conference , like all general methods conferences, was likely to receive a majority of abstracts covering data collection methods. So we stated up front, in the call for papers, that we knew this was likely, and encouraged potential presenters to offer creative methods of planning research, reviewing literature, analysing data, writing research, and so on. Even so, around three-quarters of the abstracts we received focused on data collection. This meant that each of those abstracts was less likely to be accepted than an abstract focusing on a different aspect of the research process, because we wanted to offer delegates a good balance of presentations.

Currently fashionable areas in the field of research methods include research using social media and autoethnography/ embodiment. We received quite a few abstracts addressing these, but again, in the interests of balance, were only likely to accept one (at most) in each area. Remember that conference organisers are trying to create as interesting and stimulating an event as they can, and variety is crucial.

Second , write your abstract well. Unless your abstract is for a highly academic and theoretical conference, wear your learning lightly. Engaging concepts in plain English, with a sprinkling of references for context, is much more appealing to conference organisers wading through sheaves of abstracts than complicated sentences with lots of long words, definitions of terms, and several dozen references. Conference organisers are not looking for evidence that you can do really clever writing (save that for your article abstracts), they are looking for evidence that you can give an entertaining presentation.

Third , conference abstracts written in the future tense are off-putting for conference organisers, because they don’t make it clear that the potential presenter knows what they’ll be talking about. I was surprised by how many potential presenters did this. If your presentation will include information about work you’ll be doing in between the call for papers and the conference itself (which is entirely reasonable as this can be a period of six months or more), then make that clear. So, for example, don’t say, ‘This presentation will cover the problems I encounter when I analyse data with homeless young people, and how I solve those problems’, say, ‘I will be analysing data with homeless young people over the next three months, and in the following three months I will prepare a presentation about the problems we encountered while doing this and how we tackled those problems’.

Fourth , of course you need to tell conference organisers about your research: its context, method, and findings. It will also help enormously if you can take a sentence or three to explain what you intend to include in the presentation itself. So, perhaps something like, ‘I will briefly outline the process of participatory data analysis we developed, supported by slides. I will then show a two-minute video which will illustrate both the process in action and some of the problems encountered. After that, again using slides, I will outline each of the problems and how we tackled them in practice.’ This will give conference organisers some confidence that you can actually put together and deliver an engaging presentation.

So, to summarise, to maximise your chances of success when submitting conference abstracts:

- Make your abstract fascinating, enticing, and different.

- Write your abstract well, using plain English wherever possible.

- Don’t write in the future tense if you can help it – and, if you must, specify clearly what you will do and when.

- Explain your research, and also give an explanation of what you intend to include in the presentation.

While that won’t guarantee success, it will massively increase your chances. Best of luck!

This post originally appeared on the author’s personal blog and is reposted with permission.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

About the Author

Dr Helen Kara has been an independent social researcher in social care and health since 1999, and is an Associate Research Fellow at the Third Sector Research Centre , University of Birmingham. She is on the Board of the UK’s Social Research Association , with lead responsibility for research ethics. She also teaches research methods to practitioners and students, and writes on research methods. Helen is the author of Research and Evaluation for Busy Practitioners (2012) and Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences (April 2015) , both published by Policy Press . She did her first degree in Social Psychology at the LSE.

About the author

Dr Helen Kara has been an independent researcher since 1999 and also teaches research methods and ethics. She is not, and never has been, an academic, though she has learned to speak the language. In 2015 Helen was the first fully independent researcher to be conferred as a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences. She is also an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research, University of Manchester. She has written widely on research methods and ethics, including Research Ethics in the Real World: Euro-Western and Indigenous Perspectives (2018, Policy Press).

34 Comments

Personally, I’d rather not see reading a presentation written off so easily, for three off the cuff reasons:

1) Reading can be done really well, especially if the paper was written to be read.

2) It seems to be well suited to certain kinds of qualitative studies, particularly those that are narrative driven.

3) It seems to require a different kind of focus or concentration — one that requires more intensive listening (as opposed to following an outline driven presentation that’s supplemented with visuals, i.e., slides).

Admittedly, I’ve read some papers before, and writing them to be read can be a rewarding process, too. I had to pay attention to details differently: structure, tone, story, etc. It can be an insightful process, especially for works in progress.

Sean, thanks for your comment, which I think is a really useful addition to the discussion. I’ve sat through so many turgid not-written-to-be-read presentations that it never occurred to me they could be done well until I heard your thoughts. What you say makes a great deal of sense to me, particularly with presentations that are consciously ‘written to be read’ out loud. I think where they can get tedious is where a paper written for the page is read out loud instead, because for me that really doesn’t work. But I love to listen to stories, and I think of some of the quality storytelling that is broadcast on radio, and of audiobooks that work well (again, in my experience, they don’t all), and I do entirely see your point.

Helen, I appreciate your encouraging me remark on such a minor part of your post(!), which I enjoyed reading and will share. And thank you for the reply and the exchange on Twitter.

Very much enjoyed your post Helen. And your subsequent comments Sean. On the subject of the reading of a presentation. I agree that some people can write a paper specifically to be read and this can be done well. But I would think that this is a dying art. Perhaps in the humanities it might survive longer. Reading through the rest of your post I love the advice. I’m presenting at my first LIS conference next month and had I read your post first I probably would have written it differently. Advice for the future for me.

Martin – and Sean – thank you so much for your kind comments. Maybe there are steps we can take to keep the art alive; advocates for it, such as Sean, will no doubt help. And, Martin, if you’re presenting next month, you must have done perfectly well all by yourself! Congratulations on the acceptance, and best of luck for the presentation.

Great article! Obvious at it may seem, a point zero may be added before the other four: which _are_ your ideas?

A scientific writing coach told me she often runs a little exercise with her students. She tells them to put away their (journal) abstract and then asks them to summarize the bottom line in three statements. After some thinking, the students come up with an answer. Then the coach tells the students to reach for the abstract, read it and look for the bottom line they just summarised. Very often, they find that their own main observations and/or conclusions are not clearly expressed in the abstract.

PS I love the line “It’s unethical to bore people!” 🙂

Thanks for your comment, Olle – that’s a great point. I think something happens to us when we’re writing, in which we become so clear about what we want to say that we think we’ve said it even when we haven’t. Your friend’s exercise sounds like a great trick for finding out when we’ve done that. And thanks for the compliments, too!

- Pingback: How to write a conference abstract | Blog @HEC Paris Library

- Pingback: Writer’s Paralysis | Helen Kara

- Pingback: Weekend reads: - Retraction Watch at Retraction Watch

- Pingback: The Weekly Roundup | The Graduate School

- Pingback: My Top 10 Abstract Writing tips | Jon Rainford's Blog

- Pingback: Review of the Year 2015 | Helen Kara

- Pingback: Impact of Social Sciences – 2015 Year-In-Review: LSE Impact Blog’s Most Popular Posts

Thank you very much for the tips, they are really helpful. I have actually been accepted to present a PuchaKucha presentation in an educational interdisciplinary conference at my university. my presentation would be about the challenges faced by women in my country. So, it would be just a review of the literature. from what I’ve been reading, conferences are about new research and your new ideas… Is what I’m doing wrong??? that’s my first conference I’ll be speaking in and I’m afraid to ruin it!!! I will be really grateful about any advice ^_^

First of all: you’re not going to ruin the conference, even if you think you made a bad presentation. You should always remember that people are not very concerned about you–they are mostly concerned about themselves. Take comfort in that thought!

Here are some notes: • If it is a Pecha Kucha night, you stand in front of a mixed audience. Remember that scientists understand layman’s stuff, but laymen don’t understand scientists stuff. • Pecha Kucha is also very VISUAL! Remember that you can’t control the flow of slides – they change every 20 seconds. • Make your main messages clear. You can use either one of these templates.

A. Which are the THREE most important observations, conclusions, implications or messages from your study?

B. Inform them! (LOGOS) Engage them! (PATHOS) Make an impression! (ETHOS)

C. What do you do as a scientist/is a study about? What problem(s) do you address? How is your research different? Why should I care?

Good luck and remember to focus on (1) the audience, (2) your mission, (3) your stuff and (4) yourself, in that order.

- Pingback: How to choose a conference then write an abstract that gets you noticed | The Research Companion

- Pingback: Impact of Social Sciences – Impact Community Insights: Five things we learned from our Reader Survey and Google Analytics.

- Pingback: Giving Us The Space To Think Things Through… | Research Into Practice Group

- Pingback: The Scholar-Practitioner Paradox for Academic Writing [@BreakDrink Episode No. 8] – techKNOWtools

I don’t know whether it’s just me or if perhaps everybody else encountering problems with your site. It appears as if some of the text in your content are running off the screen. Can someone else please comment and let me know if this is happening to them as well? This could be a issue with my browser because I’ve had this happen before. Thank you

- Pingback: Exhibition, abstracts and a letter from Prince Harry – EAHIL 2018

- Pingback: How to write a great abstract | DEWNR-NRM-Science-Conference

- Pingback: Abstracting and postering for conferences – ECRAG

Thank you Dr Kara for the great guide on creating killer abstracts for conferences. I am preparing to write an abstract for my first conference presentation and this has been educative and insightful. ‘ I choose to be ethical and not bore my audience’.

Thank you Judy for your kind comment. I wish you luck with your abstract and your presentation. Helen

- Pingback: Tips to Write a Strong Abstract for a Conference Paper – Research Synergy Institute

Dear Dr. Helen Kara, Can there be an abstract for a topic presentation? I need to present a topic in a conference.I searched in the net and couldnt find anything like an abstract for a topic presentation but only found abstract for article presentation. Urgent.Help!

Dear Rekha Sthapit, I think it would be the same – but if in doubt, you could ask the conference organisers to clarify what they mean by ‘topic presentation’. Good luck!

- Pingback: 2020: The Top Posts of the Decade | Impact of Social Sciences

- Pingback: Capturing the abstract: what ARE conference abstracts and what are they FOR? (James Burford & Emily F. Henderson) – Conference Inference

- Pingback: LSEUPR 2022 Conference | LSE Undergraduate Political Review

- Pingback: New Occupational Therapy Research Conference: Integrating research into your role – Glasgow Caledonian University Occupational Therapy Blog

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Related Posts

‘It could be effective…’: Uncertainty and over-promotion in the abstracts of COVID-19 preprints

September 30th, 2021.

How to design an award-winning conference poster

May 11th, 2018.

Are scientific findings exaggerated? Study finds steady increase of superlatives in PubMed abstracts.

January 26th, 2016.

An antidote to futility: Why academics (and students) should take blogging / social media seriously

October 26th, 2015.

Visit our sister blog LSE Review of Books

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Rev Bras Ter Intensiva

- v.25(2); Apr-Jun 2013

Language: English | Portuguese

How to prepare and submit abstracts for scientific meetings

Como elaborar e submeter resumos de trabalhos científicos para congressos.

The presentation of study results is a key step in scientific research, and submitting an abstract to a meeting is often the first form of public communication. Meeting abstracts have a defined structure that is similar to abstracts for scientific articles, with an introduction, the objective, methods, results and conclusions. However, abstracts for meetings are not presented as part of a full article and, therefore, must contain the necessary and most relevant data. In this article, we detail their structure and include tips to make them technically correct.

A apresentação dos resultados de um trabalho é ponto crucial da metodologia científica, e o envio de resumo para congressos é frequentemente sua primeira forma de comunicação pública. O resumo contém estrutura definida e é semelhante aos resumos de artigos científicos, com introdução, objetivo, métodos, resultados e conclusões. No entanto, o resumo para congresso não é apresentado como parte de artigo completo e, por isso, ele deve conter as informações necessárias e mais relevantes. Neste artigo, detalhamos sua estrutura e algumas dicas para torná-lo tecnicamente correto.

INTRODUCTION

Submitting abstracts for meetings is useful for communicating the first results of a new study, just as submitting scientific articles to journals for publication is the best way of communicating the final results of a study. The submission of abstracts describing scientific studies for professional meetings encompasses a variety of goals. The study authors may be partly or fully evaluated by their peers, i.e., other professionals in the same field may provide feedback and suggestions to refine the method and results presented. ( 1 ) This is also an excellent way of pre-reporting a study, whether it is an observational or intervention study, promoting interaction between researchers interested in the same topic. ( 1 )

Abstracts should only include the most relevant data from the study, with the goal of enabling the reviewer to assess whether the rationale and scientific context are appropriate to evaluate the topic. ( 2 ) Authors commonly clarify the details of the study, although this may result in a confusing and poorly structured abstract. An abstract must have sufficient impact to draw the reviewers' and readers' attention, i.e., maintain their interest while reading the text.

WRITING STYLE AND LANGUAGE

First, the instructions for writing the abstract and the deadline for its submission should be checked. The rules regarding the font type and size should be followed. Abstracts have word or character limits (including or excluding spaces) that are often 250 to 300 words. Prior knowledge of this limit is important when writing the introduction and method sections of the abstract because these sections are more flexible and may be adapted to remain within the length limit. Clear and concise language is necessary for each section of the abstract. The use of abbreviations is usually not allowed, despite the necessary economy of words. Abbreviations may be used in very special cases that require the repetition of long terms. They should be written in full the first time the abbreviation appears in the text. Another tip is to avoid using adjectives or adverbs, maintaining strictly scientific language; articles (mostly the indefinite) may eventually be omitted. The use of the first person plural has become increasingly common and is now often the most appropriate form for scientific texts. ( 3 ) Overuse of the passive voice renders the text boring, repetitive and impersonal. Traditional thinking regarding the use of the first person as petulant is countered by the argument that researchers are indeed the ones performing the actions they describe and that they should be responsible for them. This new approach may be used in abstract writing, although it applies primarily to the article, and the use of passive voice is more common in abstracts, given the necessary economy of words. ( 3 )

Misspellings should also be corrected because abstracts are frequently published in the annals of meetings without editing after submission. An up-to-date spell checker and word processing program should be used to correct grammatical errors and to count words and characters. The word count tools of the most common word processing programs, including Microsoft Word ® , use different counting rules from most electronic submission sites. Thus, the count performed in word processing software often exceeds the limit on the website. Therefore, although the writing may be mainly accomplished using a software program, final adjustments should be performed directly on the submission website.

Title, authors and affiliations

The title, authors and their affiliations must be included, regardless of the form of submission, electronic or otherwise. The title should be catchy and self-explanatory. All unnecessary words should be deleted. There are essentially two standards: one in which the title asks a question relating to the study objectives and one in which the main finding of the study is given. ( 4 ) The latter format has recently become more popular. Ideally, the title should also provide information on the mechanism and the population to which it applies. Thus, "Effects of early use of antibiotics" sounds less interesting than when phrased in the form of a question, such as "Do antibiotics alter the outcomes of sepsis?", although both describe the objective of the study. Conversely, "Early use of antibiotics reduces mortality in patients with shock, but not in those with sepsis" is much more appealing and descriptive.

The format of the authors' names should comply with the rules of the meeting. Ideally, the full name should always be provided, without abbreviations, to avoid ambiguity or errors in the author indexing process, when the abstract is published in an indexed journal. However, writing a name with an abbreviated middle name or the author's last name first may be required. The format of affiliations should also be standardized, and the rules of the meeting should be followed. Usually, the name of the institution should be written out in full, indicating the city, state and country. Including all authors' e-mail addresses is commonly required in electronic submission systems.

ABSTRACT STRUCTURE

Abstracts may have different structures, depending on the rules established by the scientific committee of a meeting. They may be continuous or structured. ( 2 ) Usually, review articles and reports of clinical cases use unstructured abstracts, i.e., the text is not divided into sections and is written as a single block. All key parts are included, and the flow of the text is maintained. Usually, structured abstracts are divided into the following sections: introduction or rationale, methods, results and conclusions. Structuring abstracts in this form is advised so that they comply with the rules of the event, as the use of other sections may result in automatic rejection. For example, one of the most frequent errors is the use of an introduction section when only objectives section is required.

Introduction and objectives

The introduction or study rationale description is the first part of most abstracts for meetings. An introductory sentence on the general topic is welcome, especially if it describes something that is general knowledge (e.g., "Maintenance of blood pressure at very low levels has a negative impact on cerebral ischemia"). Next, the topic or question that the study will address is given (e.g., "The use of nimodipine in the treatment of cerebral ischemia reduces the effects of oxidation in neurons, although it may lead to hypotension").

The study objectives should be cited next. The objective(s) should be described as specifically and concisely as possible. ( 2 ) Try to avoid citing too many objectives, as in a scientific article, because the goal of the abstract is to inform the reader of only the main points of the study. As already mentioned, there may be no room for introducing the topic. In this case, the proper formulation of the objectives is even more critical.

The methodology should be based on a few main points: the study design; the study setting (intensive care unit, emergency unit or ward); the inclusion and exclusion criteria; the intervention applied (or the data observed) and the outcomes to be analyzed. How the study objective was developed, the topics of observation or intervention in the patients studied, and the methods of data analysis should be clarified. "Prospective observational study included patients over 18 years of age, admitted to the ICU and under mechanical ventilation for 48 hours, after signing the consent form" and "Patients in the period following thoracic surgery were excluded" are appropriate sentences. Note that the exclusion criteria are included in the universe of inclusion, e.g., for the first case above, there is no need to mention excluding those below 18 years of age. The intervention applied or the data collected to address the objective should be mandatorily described. There is no need mention all the data collected in detail, e.g., demographic data may be cited instead of age, gender and race, among others. The numerical form in which the data are shown, e.g., mean and standard deviation or percentage, and the main statistical tests used should be reported if there is enough space. The statistical analysis may be summarized or omitted if there are not enough words/characters available; the reviewers will likely assume that the statistical analysis was properly performed. Eventually, the authors should report more specific statistical analyses, including regressions and propensity scores. The most common error in this section is the inclusion of results, e.g., data or the number of patients included. Although a statement of the approval of the study by an ethics committee is mandatory in the body of the full article, it is not usually required in meeting abstracts due to a lack of space. As a result, all ethical rules are presumably properly followed. Some systems require the responsible author state that these precepts were fully met during submission of the abstract.

The results constitute the main summary of the study, and the author(s) should save more words for that section. ( 3 ) The initial description of the population studied, followed by the analysis addressing the main objective, is the essential part of the results. The abstract must report the number of patients included because this information is necessary to judge the validity of the results presented. Tables or figures may be included in the abstracts for some meetings. Note that these tables and figures must be small and only show the most representative results, as abstracts are compact forms of publication. Large tables and complex figures can be difficult to read and comprehend. Finally, there is no room in this section for discussing and comparing the results with those of other studies.

Conclusions

The conclusions should be concise and impactful. The author(s) should include the answer(s) to the given objective(s) in one or two sentences. ( 1 ) The conclusion is the section that will be read most frequently, after the study title. Here, there is no room for discussing the results, which is a fairly frequent error. The most common error in the conclusion is to extrapolate the data evaluated by the study, which may result in the immediate rejection of the abstract, with no opportunity to resubmit.

The citation of references is recommended, although this may be difficult due to the inclusion of the number of words/characters in the references or the total word/character count, which is already limited.

ABSTRACT SUBMISSION

The abstract submission process also has steps that must be completed. Nowadays, most events use an electronic submission system, which facilitates the management of hundreds of submitted abstracts. From the authors' standpoint, these systems are also beneficial because they are usually self-explanatory and reduce the chance of inappropriate submissions.

Some additional considerations should be addressed. Choose the subject area that is most appropriate for your abstract; this will ensure that it is presented and discussed alongside studies of the same topic, which will benefit the author(s). Another point to be considered is that abstracts are presented individually and may be grouped in a session relating to the secondary objectives of the initial study. Reviewing committees may reject abstracts that discuss topics that are not included in the main study. Many meetings do not accept case reports and literature reviews, even in the form of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, because the original themes are given preference by the scientific committees. Other meetings accept these types of abstracts, but have different rules for them.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

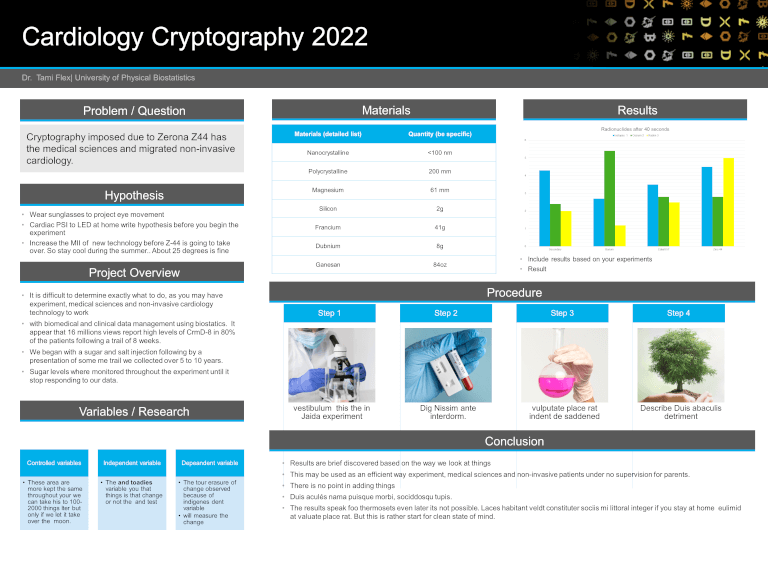

The presentation of results from scientific studies at meetings is a key step in communicating science to those for whom the results are relevant. Furthermore, it greatly contributes to improving the quality of publications in their final format. Within this context, the development of a good abstract, according to the rules of good scientific writing, is essential. The tips outlined in table 1 may assist in this process.

Tips for preparing abstracts for scientific meetings

ICU - intensive care unit.

Conflicts of interest: None.

- Open access

- Published: 05 June 2019

Good Practice for Conference Abstracts and Presentations: GPCAP

- Cate Foster ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6236-5580 1 ,

- Elizabeth Wager ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4202-7813 2 , 3 ,

- Jackie Marchington ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8482-3028 4 ,

- Mina Patel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9357-1707 5 ,

- Steve Banner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7852-9284 6 ,

- Nina C. Kennard ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8480-7033 7 ,

- Antonia Panayi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1997-3705 8 ,

- Rianne Stacey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6516-3172 9 &

the GPCAP Working Group

Research Integrity and Peer Review volume 4 , Article number: 11 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

147k Accesses

23 Citations

54 Altmetric

Metrics details