- Dissertation

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Book Report/Review

- Research Proposal

- Math Problems

- Proofreading

- Movie Review

- Cover Letter Writing

- Personal Statement

- Nursing Paper

- Argumentative Essay

- Research Paper

- Discussion Board Post

How To Write A Strong Obesity Research Paper?

Table of Contents

Obesity is such a disease when the percent of body fat has negative effects on a person’s health. The topic is very serious as obesity poisons the lives of many teens, adults and even children around the whole world.

Can you imagine that according to WHO (World Health Organization) there were 650 million obese adults and 13% of all 18-year-olds were also obese in 2016? And scientists claim that the number of them is continually growing.

There are many reasons behind the problem, but no matter what they are, lots of people suffer from the wide spectrum of consequences of obesity.

Basic guidelines on obesity research paper

Writing any research paper requires sticking to an open-and-shut structure. It has three basic parts: Introduction, Main Body, and Conclusion.

According to the general rules, you start with the introduction where you provide your reader with some background information and give brief definitions of terms used in the text. Next goes the thesis of your paper.

The thesis is the main idea of all the research you’ve done written in a precise and simple manner, usually in one sentence.

The main body is where you present the statements and ideas which disclose the topic of your research.

In conclusion, you sum up all the text and make a derivation.

How to write an obesity thesis statement?

As I’ve already noted, the thesis is the main idea of your work. What is your position? What do you think about the issue? What is that you want to prove in your essay?

Answer one of those questions briefly and precisely.

Here are some examples of how to write a thesis statement for an obesity research paper:

- The main cause of obesity is determined to be surfeit and unhealthy diet.

- Obesity can be prevented no matter what genetic penchants are.

- Except for being a problem itself, obesity may result in diabetes, cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and many others.

- Obesity is a result of fast-growing civilization development.

- Not only do obese people have health issues but also they have troubles when it comes to socialization.

20 top-notch obesity research paper topics

Since the problem of obesity is very multifaceted and has a lot of aspects to discover, you have to define a topic you want to cover in your essay.

How about writing a fast food and obesity research paper or composing a topic in a sphere of fast food? Those issues gain more and more popularity nowadays.

A couple of other decent ideas at your service.

- The consequences of obesity.

- Obesity as a mental problem.

- Obesity and social standards: the problem of proper self-fulfilment.

- Overweight vs obesity: the use of BMI (Body Mass Index).

- The problem of obesity in your country.

- Methods of prevention the obesity.

- Is lack of self-control a principal factor of becoming obese?

- The least obvious reasons for obesity.

- Obesity: the history of the disease.

- The effect of mass media in augmentation of the obesity level.

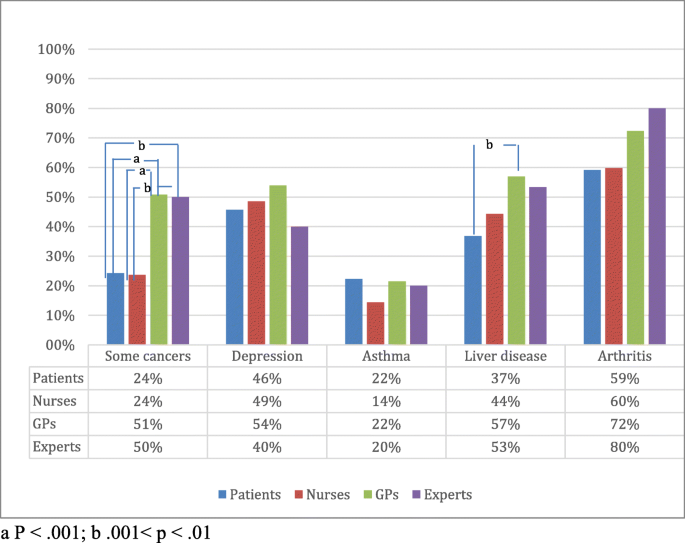

- The connection between depression and obesity.

- The societal stigma of obese people.

- The role of legislation in reducing the level of obesity.

- Obesity and cultural aspect.

- Who has the biggest part of the responsibility for obesity: persons themselves, local authorities, government, mass media or somebody else?

- Why are obesity rates constantly growing?

- Who is more prone to obesity, men or women? Why?

- Correlation between obesity and life expectancy.

- The problem of discrimination of the obese people at the workplace.

- Could it be claimed that such movements as body-positive and feminism encourage obesity to a certain extent?

Best sample of obesity research paper outline

An outline is a table of contents which is made at the very beginning of your writing. It helps structurize your thoughts and create a plan for the whole piece in advance.

…Need a sample?

Here is one! It fits the paper on obesity in the U.S.

Introduction

- Hook sentence.

- Thesis statement.

- Transition to Main Body.

- America’s modern plague: obesity.

- Statistics and obesity rates in America.

- Main reasons of obesity in America.

- Social, cultural and other aspects involved in the problem of obesity.

- Methods of preventing and treating obesity in America.

- Transition to Conclusion.

- Unexpected twist or a final argument.

- Food for thought.

Specifics of childhood obesity research paper

A separate question in the problem of obesity is overweight children.

It is singled out since there are quite a lot of differences in clinical pictures, reasons and ways of treatment of an obese adult and an obese child.

Writing a child obesity research paper requires a more attentive approach to the analysis of its causes and examination of family issues. There’s a need to consider issues like eating habits, daily routine, predispositions and other.

Top 20 childhood obesity research paper topics

We’ve gathered the best ideas for your paper on childhood obesity. Take one of those to complete your best research!

- What are the main causes of childhood obesity in your country?

- Does obesity in childhood increase the chance of obesity in adulthood?

- Examine whether a child’s obesity affects academic performance.

- Are parents always guilty if their child is obese?

- What methods of preventing childhood obesity are used in your school?

- What measures the government can take to prevent children’s obesity?

- Examine how childhood obesity can result in premature development of chronic diseases.

- Are obese or overweight parents more prone to have an obese child?

- Why childhood obesity rates are constantly growing around the whole world?

- How to encourage children to lead a healthy style of life?

- Are there more junk and fast food options for children nowadays? How is that related to childhood obesity rates?

- What is medical treatment for obese children?

- Should fast food chains have age limits for their visitors?

- How should parents bring up their child in order to prevent obesity?

- The problem of socializing in obese children.

- Examine the importance of a proper healthy menu in schools’ cafeterias.

- Should the compulsory treatment of obese children be started up?

- Excess of care as the reason for childhood obesity.

- How can parents understand that their child is obese?

- How can the level of wealth impact the chance of a child’s obesity?

Childhood obesity outline example

As the question of childhood obesity is a specific one, it would differ from the outline on obesity we presented previously.

Here is a sample you might need. The topic covers general research on child obesity.

- The problem of childhood obesity.

- World’s childhood obesity rates.

- How to diagnose the disease.

- Predisposition and other causes of child obesity.

- Methods of treatment for obese children.

- Preventive measures to avoid a child’s obesity.

On balance…

The topic of obesity is a long-standing one. It has numerous aspects to discuss, sides to examine, and data to analyze.

Any topic you choose might result in brilliant work.

How can you achieve that?

Follow the basic requirements, plan the content beforehand, and be genuinely interested in the topic.

Option 2. Choose free time over struggle on the paper. We’ve got dozens of professional writers ready to help you out. Order your best paper within several seconds and enjoy your free time. We’ll cover you up!

How to Write a Cleanliness Essay

Why is a ‘how to write assignment’ request too common among learners.

Steps To Follow While Writing An Essay On Climate Change

Obesity Essay

Last updated on: Feb 9, 2023

Obesity Essay: A Complete Guide and Topics

By: Nova A.

11 min read

Reviewed By: Jacklyn H.

Published on: Aug 31, 2021

Are you assigned to write an essay about obesity? The first step is to define obesity.

The obesity epidemic is a major issue facing our country right now. It's complicated- it could be genetic or due to your environment, but either way, there are ways that you can fix it!

Learn all about what causes weight gain and get tips on how you can get healthy again.

On this Page

What is Obesity

What is obesity? Obesity and BMI (body mass index) are both tools of measurement that are used by doctors to assess body fat according to the height, age, and gender of a person. If the BMI is between 25 to 29.9, that means the person has excess weight and body fat.

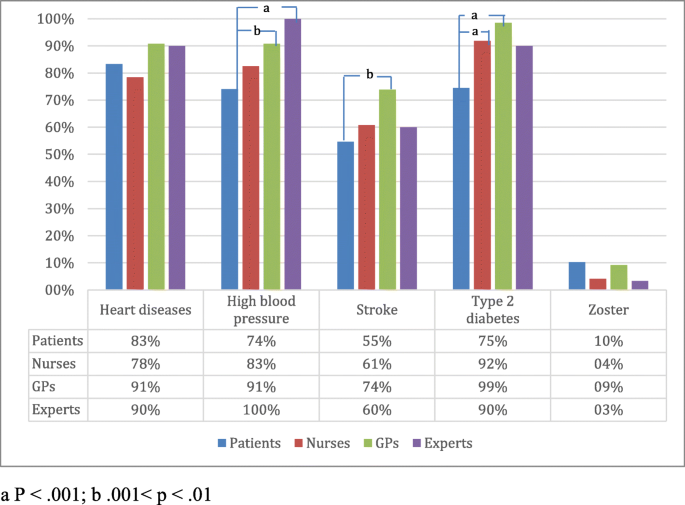

If the BMI exceeds 30, that means the person is obese. Obesity is a condition that increases the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, high blood pressure, and other medical conditions like metabolic syndrome, arthritis, and even some types of cancer.

Obesity Definition

Obesity is defined by the World Health Organization as an accumulation of abnormal and excess body fat that comes with several risk factors. It is measured by the body mass index BMI, body weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of a person’s height (in meters).

Obesity in America

Obesity is on the verge of becoming an epidemic as 1 in every 3 Americans can be categorized as overweight and obese. Currently, America is an obese country, and it continues to get worse.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Causes of obesity

Do you see any obese or overweight people around you?

You likely do.

This is because fast-food chains are becoming more and more common, people are less active, and fruits and vegetables are more expensive than processed foods, thus making them less available to the majority of society. These are the primary causes of obesity.

Obesity is a disease that affects all age groups, including children and elderly people.

Now that you are familiar with the topic of obesity, writing an essay won’t be that difficult for you.

How to Write an Obesity Essay

The format of an obesity essay is similar to writing any other essay. If you need help regarding how to write an obesity essay, it is the same as writing any other essay.

Obesity Essay Introduction

The trick is to start your essay with an interesting and catchy sentence. This will help attract the reader's attention and motivate them to read further. You don’t want to lose the reader’s interest in the beginning and leave a bad impression, especially if the reader is your teacher.

A hook sentence is usually used to open the introductory paragraph of an essay in order to make it interesting. When writing an essay on obesity, the hook sentence can be in the form of an interesting fact or statistic.

Head on to this detailed article on hook examples to get a better idea.

Once you have hooked the reader, the next step is to provide them with relevant background information about the topic. Don’t give away too much at this stage or bombard them with excess information that the reader ends up getting bored with. Only share information that is necessary for the reader to understand your topic.

Next, write a strong thesis statement at the end of your essay, be sure that your thesis identifies the purpose of your essay in a clear and concise manner. Also, keep in mind that the thesis statement should be easy to justify as the body of your essay will revolve around it.

Body Paragraphs

The details related to your topic are to be included in the body paragraphs of your essay. You can use statistics, facts, and figures related to obesity to reinforce your thesis throughout your essay.

If you are writing a cause-and-effect obesity essay, you can mention different causes of obesity and how it can affect a person’s overall health. The number of body paragraphs can increase depending on the parameters of the assignment as set forth by your instructor.

Start each body paragraph with a topic sentence that is the crux of its content. It is necessary to write an engaging topic sentence as it helps grab the reader’s interest. Check out this detailed blog on writing a topic sentence to further understand it.

End your essay with a conclusion by restating your research and tying it to your thesis statement. You can also propose possible solutions to control obesity in your conclusion. Make sure that your conclusion is short yet powerful.

Obesity Essay Examples

Essay about Obesity (PDF)

Childhood Obesity Essay (PDF)

Obesity in America Essay (PDF)

Essay about Obesity Cause and Effects (PDF)

Satire Essay on Obesity (PDF)

Obesity Argumentative Essay (PDF)

Obesity Essay Topics

Choosing a topic might seem an overwhelming task as you may have many ideas for your assignment. Brainstorm different ideas and narrow them down to one, quality topic.

If you need some examples to help you with your essay topic related to obesity, dive into this article and choose from the list of obesity essay topics.

Childhood Obesity

As mentioned earlier, obesity can affect any age group, including children. Obesity can cause several future health problems as children age.

Here are a few topics you can choose from and discuss for your childhood obesity essay:

- What are the causes of increasing obesity in children?

- Obese parents may be at risk for having children with obesity.

- What is the ratio of obesity between adults and children?

- What are the possible treatments for obese children?

- Are there any social programs that can help children with combating obesity?

- Has technology boosted the rate of obesity in children?

- Are children spending more time on gadgets instead of playing outside?

- Schools should encourage regular exercises and sports for children.

- How can sports and other physical activities protect children from becoming obese?

- Can childhood abuse be a cause of obesity among children?

- What is the relationship between neglect in childhood and obesity in adulthood?

- Does obesity have any effect on the psychological condition and well-being of a child?

- Are electronic medical records effective in diagnosing obesity among children?

- Obesity can affect the academic performance of your child.

- Do you believe that children who are raised by a single parent can be vulnerable to obesity?

- You can promote interesting exercises to encourage children.

- What is the main cause of obesity, and why is it increasing with every passing day?

- Schools and colleges should work harder to develop methodologies to decrease childhood obesity.

- The government should not allow schools and colleges to include sweet or fatty snacks as a part of their lunch.

- If a mother is obese, can it affect the health of the child?

- Children who gain weight frequently can develop chronic diseases.

Obesity Argumentative Essay Topics

Do you want to write an argumentative essay on the topic of obesity?

The following list can help you with that!

Here are some examples you can choose from for your argumentative essay about obesity:

- Can vegetables and fruits decrease the chances of obesity?

- Should you go for surgery to overcome obesity?

- Are there any harmful side effects?

- Can obesity be related to the mental condition of an individual?

- Are parents responsible for controlling obesity in childhood?

- What are the most effective measures to prevent the increase in the obesity rate?

- Why is the obesity rate increasing in the United States?

- Can the lifestyle of a person be a cause of obesity?

- Does the economic situation of a country affect the obesity rate?

- How is obesity considered an international health issue?

- Can technology and gadgets affect obesity rates?

- What can be the possible reasons for obesity in a school?

- How can we address the issue of obesity?

- Is obesity a chronic disease?

- Is obesity a major cause of heart attacks?

- Are the junk food chains causing an increase in obesity?

- Do nutritional programs help in reducing the obesity rate?

- How can the right type of diet help with obesity?

- Why should we encourage sports activities in schools and colleges?

- Can obesity affect a person’s behavior?

Health Related Topics for Research Paper

If you are writing a research paper, you can explain the cause and effect of obesity.

Here are a few topics that link to the cause and effects of obesity.Review the literature of previous articles related to obesity. Describe the ideas presented in the previous papers.

- Can family history cause obesity in future generations?

- Can we predict obesity through genetic testing?

- What is the cause of the increasing obesity rate?

- Do you think the increase in fast-food restaurants is a cause of the rising obesity rate?

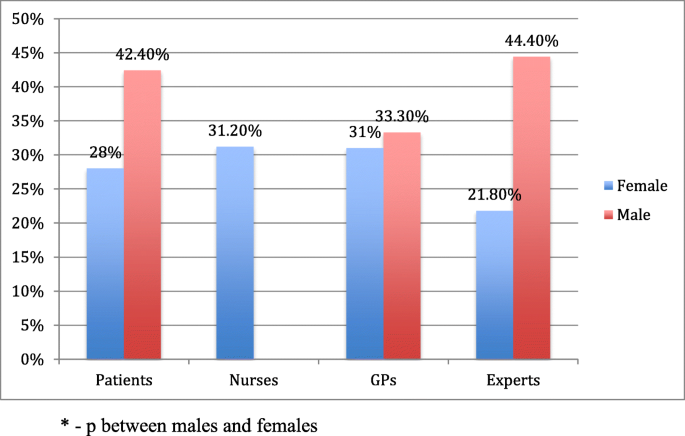

- Is the ratio of obese women greater than obese men?

- Why are women more prone to be obese as compared to men?

- Stress can be a cause of obesity. Mention the reasons how mental health can be related to physical health.

- Is urban life a cause of the increasing obesity rate?

- People from cities are prone to be obese as compared to people from the countryside.

- How obesity affects the life expectancy of people? What are possible solutions to decrease the obesity rate?

- Do family eating habits affect or trigger obesity?

- How do eating habits affect the health of an individual?

- How can obesity affect the future of a child?

- Obese children are more prone to get bullied in high school and college.

- Why should schools encourage more sports and exercise for children?

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Topics for Essay on Obesity as a Problem

Do you think a rise in obesity rate can affect the economy of a country?

Here are some topics for your assistance regarding your economics related obesity essay.

- Does socioeconomic status affect the possibility of obesity in an individual?

- Analyze the film and write a review on “Fed Up” – an obesity epidemic.

- Share your reviews on the movie “The Weight of The Nation.”

- Should we increase the prices of fast food and decrease the prices of fruits and vegetables to decrease obesity?

- Do you think healthy food prices can be a cause of obesity?

- Describe what measures other countries have taken in order to control obesity?

- The government should play an important role in controlling obesity. What precautions should they take?

- Do you think obesity can be one of the reasons children get bullied?

- Do obese people experience any sort of discrimination or inappropriate behavior due to their weight?

- Are there any legal protections for people who suffer from discrimination due to their weight?

- Which communities have a higher percentage of obesity in the United States?

- Discuss the side effects of the fast-food industry and their advertisements on children.

- Describe how the increasing obesity rate has affected the economic condition of the United States.

- What is the current percentage of obesity all over the world? Is the obesity rate increasing with every passing day?

- Why is the obesity rate higher in the United States as compared to other countries?

- Do Asians have a greater percentage of obese people as compared to Europe?

- Does the cultural difference affect the eating habits of an individual?

- Obesity and body shaming.

- Why is a skinny body considered to be ideal? Is it an effective way to reduce the obesity rate?

Obesity Solution Essay Topics

With all the developments in medicine and technology, we still don’t have exact measures to treat obesity.

Here are some insights you can discuss in your essay:

- How do obese people suffer from metabolic complications?

- Describe the fat distribution in obese people.

- Is type 2 diabetes related to obesity?

- Are obese people more prone to suffer from diabetes in the future?

- How are cardiac diseases related to obesity?

- Can obesity affect a woman’s childbearing time phase?

- Describe the digestive diseases related to obesity.

- Obesity may be genetic.

- Obesity can cause a higher risk of suffering a heart attack.

- What are the causes of obesity? What health problems can be caused if an individual suffers from obesity?

- What are the side effects of surgery to overcome obesity?

- Which drugs are effective when it comes to the treatment of obesity?

- Is there a difference between being obese and overweight?

- Can obesity affect the sociological perspective of an individual?

- Explain how an obesity treatment works.

- How can the government help people to lose weight and improve public health?

Writing an essay is a challenging yet rewarding task. All you need is to be organized and clear when it comes to academic writing.

- Choose a topic you would like to write on.

- Organize your thoughts.

- Pen down your ideas.

- Compose a perfect essay that will help you ace your subject.

- Proofread and revise your paper.

Were the topics useful for you? We hope so!

However, if you are still struggling to write your paper, you can pick any of the topics from this list, and our essay writer will help you craft a perfect essay.

Are you struggling to write an effective essay?

If writing an essay is the actual problem and not just the topic, you can always hire an essay writing service for your help. Essay experts at 5StarEssays can help compose an impressive essay within your deadline.

All you have to do is contact us. We will get started on your paper while you can sit back and relax.

Place your order now to get an A-worthy essay.

Marketing, Thesis

As a Digital Content Strategist, Nova Allison has eight years of experience in writing both technical and scientific content. With a focus on developing online content plans that engage audiences, Nova strives to write pieces that are not only informative but captivating as well.

Was This Blog Helpful?

Keep reading.

- How to Write A Bio – Professional Tips and Examples

- Learn How to Write an Article Review with Examples

- How to Write a Poem Step-by-Step Like a Pro

- How To Write Poetry - 7 Fundamentals and Tips

- Know About Appendix Writing With the Help of Examples

- List of Social Issues Faced By the World

- How To Write A Case Study - Easy Guide

- Learn How to Avoid Plagiarism in 7 Simple Steps

- Writing Guide of Visual Analysis Essay for Beginners

- Learn How to Write a Personal Essay by Experts

- Character Analysis - A Step By Step Guide

- Thematic Statement: Writing Tips and Examples

- Expert Guide on How to Write a Summary

- How to Write an Opinion Essay - Structure, Topics & Examples

- How to Write a Synopsis - Easy Steps and Format Guide

- Learn How To Write An Editorial By Experts

- How to Get Better at Math - Easy Tips and Tricks

- How to Write a Movie Review - Steps and Examples

- Creative Writing - Easy Tips For Beginners

- Types of Plagiarism Every Student Should Know

People Also Read

- writing reflective essay

- 10essential essay writing techniques for students

- reflective essay topics

- essay writing skills

- analytical essay writing

Burdened With Assignments?

Advertisement

- Homework Services: Essay Topics Generator

© 2024 - All rights reserved

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 07 May 2024

Epidemiology and Population Health

Obesity: a 100 year perspective

- George A. Bray ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9945-8772 1

International Journal of Obesity ( 2024 ) Cite this article

737 Accesses

23 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Biological techniques

- Health care

- Weight management

This review has examined the scientific basis for our current understanding of obesity that has developed over the past 100 plus years. Obesity was defined as an excess of body fat. Methods of establishing population and individual changes in levels of excess fat are discussed. Fat cells are important storage site for excess nutrients and their size and number affect the response to insulin and other hormones. Obesity as a reflection of a positive fat balance is influenced by a number of genetic and environmental factors and phenotypes of obesity can be developed from several perspectives, some of which have been elaborated here. Food intake is essential for maintenance of human health and for the storage of fat, both in normal amounts and in obesity in excess amounts. Treatment approaches have taken several forms. There have been numerous diets, behavioral approaches, along with the development of medications.. Bariatric/metabolic surgery provides the standard for successful weight loss and has been shown to have important effects on future health. Because so many people are classified with obesity, the problem has taken on important public health dimensions. In addition to the scientific background, obesity through publications and organizations has developed its own identity. While studying the problem of obesity this reviewer developed several aphorisms about the problem that are elaborated in the final section of this paper.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

251,40 € per year

only 20,95 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Obesity and the risk of cardiometabolic diseases

Obesity-induced and weight-loss-induced physiological factors affecting weight regain

Normal weight obesity and unaddressed cardiometabolic health risk—a narrative review

Quetelet, Adolphe Sur l’homme et le developpement de ses facultes, ou essai de physique sociale ; Paris: Bachelier, 1835 (Transl of L-A-J. A Treatise on Man and the Development of His Faculties. IN: Bray GA. The Battle of the Bulge: A History of Obesity Research . Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing, 2007 pp 423-36.

Bray GA. Quetelet: quantitative medicine. Obes Res. 1994;2:68–71.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bray GA. Beyond BMI. Nutrients. 2023;15:2254.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Flegal KM. Use and misuse of BMI categories. AMA J Ethics. 2023;25:E550–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Keys A, Fidanza F, Karvonen MJ, Kimura N, Taylor HL. Indices of relative weight and obesity. J Chr Diseases. 1972;25:329–43.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bray GA. Definition, measurement, and classification of the syndromes of obesity. Int J Obes. 1978;2:99–112.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Garrow JS. Treat Obesity Seriouslv-A Clinical Manual . Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1981.

Rodgers A, Woodward A, Swinburn B, Dietz WH. Prevalence trends tell us what did not precipitate the US obesity epidemic. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3:e162–3.

Bray GA. Body fat distribution and the distribution of scientific knowledge. Obes Res. 1996;4:189–92.

Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:379–84.

Weeks RW. An experiment with the specialized investigation. Actuar Soc Am Trans. 1904;8:17–23.

Google Scholar

Vague J. La differenciation sexuelle facteur determinant des formes de l’obesite, Presse Medicale. 1947;55:339 340. [Translated. IN: Bray GA. The Battle of the Bulge: A History of Obesity Research . Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing, 2007 pp 693–5].

Vague J. The degree of masculine differentiation of obesities: a factor determining predisposition to diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout, and uric calculous disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1956;4:20–34.

Larsson B, Svardsudd K, Welin L, Wihelmsen L, Bjorntorp P, Tibbllne G. Abdominal adipose tissue distribution, obesity and risk of cardiovascular disease and death: 13 year follow up of participants in the study of 792 men born in 1913. BMJ 1984;288:1401–4.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bjorntorp P. Visceral obesity: a “civilization syndrome. Obes Res. 1993;1:206–22.

Behnke AR, Feen BG, Welham WC. The specific gravity of healthy men. JAMA 1942;118:495–8.

Article Google Scholar

Roentgen WC. Ueber eine neue Art von Strahlen. S.B. Phys-med Ges Wurzburg. 1895;132–41.

Wong MC, Bennett JP, Leong LT, Tian IY, Liu YE, Kelly NN, et al. Monitoring body composition change for intervention studies with advancing 3D optical imaging technology in comparison to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Am J Clin Nutr. 2023:S0002-9165(23)04152-7

Church TS, Thomas DM, Tudor-Locke C, Katzmarzyk PT, Earnest CP, Rodarte RQ, et al. Trends over 5 decades in U.S. occupation-related physical activity and their associations with obesity. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19657 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019657 .

Schwann TH; Smith H, Trans. Microsccopical researches into the accordance in the structure and growth of animals and plants . London: Sydenham Society 1847

Hassall A. Observations on the development of the fat vesicle. Lancet. 1849;1:163–4.

Hirsch J, Knittle JL. Cellularity of human obese and nonobese adipose tissue. Fed Proc. 1970;29:1516–21.

Garvey WT. New Horizons. A new paradigm for treating to target with second-generation obesity medications. JCEM. 2022;107:e1339–47.

Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372:425–32.

Lavoisier AL, DeLaPlace PS. Memoir on Heat. Read to the Royal Academy of Sciences 28 June 1783 [IN: Bray GA. The Battle of the Bulge: A History of Obesity Research . Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing, 2007 pp 498–512].

Bray GA. Lavoisier and Scientific Revolution: The oxygen theory displaces air, fire, earth and water. Obes Res. 1994;2:183–8.

Helmholtz, Hermann von. Uber die Erhaltung der Kraft, ein physikalische Abhandlung, vorgetragen in der Sitzung der physicalischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin am 23sten Juli 1847. Berlin: G. Reimer, 1847.

Bray GA. Commentary on Atwater classic. Obes Res. 1993;1:223–7.

Bray GA. Energy expenditure using doubly labeled water: the unveiling of objective truth. Obes Res. 1997;5:71–7.

Lifson N, Gordon GB, McClintock R. Measurement of total carbon dioxide production by means of D 2 0 18 . J Appl Physiol. 1955;7:704–10.

Lichtman SW, Pisarska K, Berman ER, Pestone M, Dowling H, Offenbacher E, et al. Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(Dec):1893–8.

Bray GA. Commentary on classics of obesity 4. Hypothalamic obesity. Obes Res. 1993;1:325–8.

Bruch H. The froehlich syndrome: report of the original case. Am J Dis Child. 1939;58:1281–90.

Babinski JP. Tumeur du corps pituitaire sans acromegalie et arret de development des organs genitaux. Rev Neurol. 1900;8:531–3. [Translation IN: Bray GA. The Battle of the Bulge: A History of Obesity Research . Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing, 2007 pp 740–1]

Cushing H. The Pituitary Body and Its Disorders . Philadelphia. PA: JB Lippincott; 1912.

Bray GA. Laurence, moon, Bardet Biedl: reflect a syndrome. Obes Res. 1995;3:383–6.

Laurence JZ, Moon RC. Four cases of “Retinitis Pigmentosa,” Occurring in the same family, and accompanied by general imperfections of development. Opthalmol Rev. 1866;2:32–41.

Bardet G. Sur un Syndrome d’Obesity Conginitale avec Polydactylie et Retinite Pigmentaire (Contribution a l’etude des formes clinique de 1 ’Obesite hypophysaire) . Paris: 1920. Thesis [Translation IN: Bray GA. The Battle of the Bulge: A History of Obesity Research . Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing, 2007 pp 740–1].

Biedl A. Geschwisterpaar mit adiposo-genitaler Dystrophie. Dtsch Med Woche. 1922;48:1630.

Cuenot L. Pure strains and their combinations in the mouse. Arch Zoot Exptl Gen. 1905;122:123.

Ingalls AM, Dickie MM, Snell GD. Obese, new mutation in the mouse. J Hered. 1950;41:317–8.

Coleman DL. Obesity and diabetes: two mutant genescausing obesity-obesity syndromes in mice. Diabetalogia. 1978;14:141–8.

Zucker TF, Zucker LM. Fat accretion and growth in the rat. J Nutr. 1963;80:6–20.

Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Zeltser LM, Drewnowski A, Ravussin E, Redman LM, et al. Obesity pathogenesis: an endocrine society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2017;38:267–96.

Oral EA, Simha V, Ruiz E, Andewelt A, Premkumar A, Snell P, et al. Leptin-replacement therapy for lipodystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:570–8.

Loos RJF, Yeo GSH. The genetics of obesity: from discovery to biology. Nat Rev Genet. 2022;23:120–33.

Blüher M. Metabolically healthy obesity. Endocr Rev. 2020;41:405–20.

Acosta A, Camilleri M, Abu Dayyeh B, Calderon G, Gonzalez D, McRae A, et al. Selection of antiobesity medications based on phenotypes enhances weight loss: a pragmatic trial in an obesity clinic. Obes. 2021;29:662–71.

Bray GA. Commentary on classics in obesity. 6. Science and politics of hunger. Obes Res. 1993;19:489–93.

Cannon WB, Washburn AL. An explanation of hunger. Am J Physiol. 1912;29:441–54.

Carlson AJ. Contributions to the physiology of the stomach -II. the relation between the concentrations of the empty stomach and the sensation of hunger. Am J Physiol. 1912;31:175–92.

Carlson AJ. Control of Hunger in Health and Disease . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1916.

Flint A, Raben A, Astrup A, Holst JJ. Glucagon-like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:515–20.

Bray GA. Eat slowly - From laboratory to clinic; behavioral control of eating. Obes Res. 1996;4:397–400.

Pavlov IP; Thompson WH, trans. The Work of the Digestive Glands . London: Charles Griffin and Co.; 1910.

Skinner BF. Contingencies of Reinforcement: A Theoretical Analysis . New York: Meredith Corporation; 1969.

Ferster CB, Nurenberger JI, Levitt EG. The Control of Eating. J. Math 1964;1:87-109.

Stuart RB. Behavioral control of overeating. Behav Res Ther. 1967;5:357–65. [Also IN: Bray GA. The Battle of the Bulge: A History of Obesity Research . Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing, 2007 pp 793–9]

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM. et a; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(Feb):393–403.

The Look AHEAD Research Group, Wadden TA, Bantle JP, Blackburn GL, Bolin P, Brancati FL, Bray GA, et al. Eight-year weight losses with an intensive lifestyle intervention: the look AHEAD study. Obesity. 2014;22:5–13.

Bray GA, Suminska M. From Hippocrates to the Obesity Society: A Brief History. IN Handbook of Obesity (Bray GA, Bouchard C, Katzmarzyk P, Kirwan JP, Redman LM, Schauer PL eds). Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis 2024. Vol 2, pp 3–16.

Bray GA. Commentary on Banting Letter. Obes Res. 1993;1:148–52.

Banting W. Letter on Corpulence, Addressed to the Public . London: Harrison and Sons 1863. pp 1–21.

Harvey W. On corpulence in relation to disease” With some remarks of diet . London” Henry Renshaw, 1872.

Schwartz, H. Never Satisfied. A Cultural History of Diets, Fantasies and Fat . 1977.

Foxcroft, Louise. Calories and Corsets. A history of dieting over 2000 years . London: Profile Books, 2011.

Gilman, Sander L. Obesity. The Biography . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Linn R Stuart SL. The Last Chance Diet . A Revolutionary New Approach to Weight Loss 1977.

Magendie F. Rapport fait a l’Academie des Sciences au le nom de la Commission diet la gelatine. C.R. Academie Sci (Paris) 1841:237-83.

Bray GA. “The Science of Hunger: Revisiting Two Theories of Feeding. IN Bray GA. The Battle of the Bulge. A History of Obesity Research . Pittsburgh, Dorrance Publishing 1977 p. 238.

Sours HE, Frattalli VP, Brand CD, et al. Sudden death associated with very low calorie weight regimes. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:453–61.

Bray GA. From very-low-energy diets to fasting and back. Obes Res. 1995;3:207–9.

Benedict, F.G. A Study of prolonged fasting . Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington (Publ No 203), 1915.

Keys A, Brozek J, Henschel A, Mickelsen O,Taylor HL. The biology of human starvation . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1950.

Cahill GF Jr, Herrera MG, Morgan AP, Soeldner JS, Steinke J, Levy PL, et al. Hormone-fuel interrelationships during fasting. J Clin Invest. 1966;45:1751–69.

Benedict FG, Miles WR, Roth P, Smith HM. Human vitality and efficiency under prolonged restricted diet. Carnegie Instit Wash, Pub. No. 280. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington; 1919.

Evans FA, Strang JM. The treatment of obesity with low-calorie diets. JAMA 1931;97:1063–8.

Bloom WL. Fasting as an introduction to the treatment of obesity. Metabolism 1959;8:2 14–220.

CAS Google Scholar

Bray GA, Purnell JQ. An historical review of steps and missteps in the discovery of anti-obesity drugs. IN: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, et al. editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2022.

Lesses MF, Myerson A. Human autonomic pharmacology. NEJM 1938;218:119-24.

Cohen PA, Goday A, Swann JP. The return of rainbow diet pills. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1676–86.

Bray GA. Nutrient intake is modulated by peripheral peptide administration. Obes Res. 1995;3:569S–572S.

Kissileff HR, Pi-Sunyer FX, Thornton J, Smith GP. C-terminal octapeptide of cholecystokinin decreases food intake in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:154–60.

Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, Davies M, Van Gaal LF, Lingvay I, et al. STEP 1 study group. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:989–1002.

Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, Eliaschewitz FG, Jódar E, Leiter LA, et al. SUSTAIN-6 investigators. semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1834–44.

Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, Wharton S, Connery L, Alves B, et al. SURMOUNT-1 investigators. tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N. Engl J Med. 2022;387:205–16.

Jastreboff AM, Kaplan LM, Frías JP, Wu Q, Du Y, Gurbuz S, et al. Retatrutide phase 2 obesity trial investigators. Triple-hormone-receptor agonist retatrutide for obesity - a phase 2 trial. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:514–26.

Bray GA. Obesity and surgery for a chronic disease. Obes Res. 1996;4:301–3.

Kremen AJ, Linner JH, Nelson CH. An experimental evaluation of the nutritional importance of proximal and distal small intestine. Ann Surg. 1954;140:439–48.

Payne JH, DeWind LT, Commons RR. Metabolic observations in patients with jejuno-colic shunts. Am J Surg. 1963;106:273–89.

Payne JH, DeWind LT. Surgical treatment of obesity. Am J Surg. 1969;118:141–6.

Buchwald H, Varco RL. Partial ileal bypass for hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1967;124:1231.

Mason EE, Ito C. Gastric bypass in obesity. Surg Clin North Am. 1967;47:1345–135.

O’Brien PE, MacDonald L, Anderson M, Brennan L, Brown WA. Long-term outcomes after bariatric surgery: fifteen-year follow-up of adjustable gastric banding and a systematic review of the bariatric surgical literature. Ann Surg. 2013;257:87–94.

Arterburn D, Wellman R, Emiliano A, Smith SR, Odegaard AO, Murali S, et al. PCORnet bariatric study collaborative. Comparative effectiveness and safety of bariatric procedures for weight loss: a PCORnet cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:741–50.

Picot J, Jones J, Colquitt JL, Gospodarevskaya E, Loveman E, Baxter L, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bariatric (weight loss) surgery for obesity: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:1–190.

Christou NV, Sampalis JS, Liberman M, et al. Surgery decreases long-term mortality, morbidity, and health care use in morbidly obese patients. Ann Surg. 2004;240:416–23.

Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273:219–34.

Sjöström L. Swedish Obese Subjects, SOS: A review of results from a prospective controlled intervention trial. In: Bray GA, Bochard C, eds. Handbook of Obesity, Volume 2: Clinical Applications. New York: Informa; 2014.

Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish Obese Subjects. N. Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–52.

Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, Sjöström CD, Karason K, Wedel H, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA 2012;307:56–65.

Carlsson LM, Peltonen M, Ahlin S, Anveden Å, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Bariatric surgery and prevention of type 2 diabetes in Swedish Obese Subjects. The New England. J Med. 2012;367:695–704.

Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, Long SB, Morris PG, Brown BM, et al. Who would have thought it? an operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset. Diabetes Mellit Ann Surg. 1995;222:339–52.

Bray GA. Life insurance and overweight. Obes Res. 1995;3:97–99.

The Association of Life Insurance Medical Directors and The Actuarial Society of America. Medico- Actuarial Mortality Investigation . New York: The Association of Life Insurance Medical Directors and ‘The Actuarial Society of America; 1913.

Keys A. Seven Countries: A Multivariate Analysis of Death and Coronary Heart Disease . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1980.

Dawber TR. The Framingham Study: The Epidemiology of Atherosclerotic Disease . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1980.

Bray, G.A. (Ed), Obesity in Perspective . Fogarty International Center Series on Preventive Med. Vol 2, parts 1 and 2, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Govt Prtg Office, 1976, DHEW Publication #75-708.

Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Afful J. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and severe obesity among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 1960–1962 through 2017–2018. NCHS Health E-Stats. 2020.

Bray GA. Obesity: Historical development of scientific and cultural ideas. Int J Obes. 1990;14:909–26.

Bray GA. The Battle of the Bulge: A History of Obesity Research . Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing, 2007 p 30.

Short, T. A Discourse Concerning the Causes and Effects of Corpulency Together with the Method for Its Prevention and Cure , J. Robert, London, 1727.

Flemyng, M. A Discourse on the Nature, Causes and Cure of Corpulency , L Davis and C Reymers, London, 1760.

Wadd, W. Comments on corpulency lineaments of leanness mems on diet and dietetics. London: John Ebers and Co, 1829.

Chambers, TK. Corpulence, or excess fat in the human body. London: Longman, 1850.

Rony HR. Obesity and Leanness . Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger, 1940.

Rynearson EH, Gastineau CF. Obesity . Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1949.

Bray, G.A. The Obese Patient. Major Problems in Internal Medicine , Vol 9, Philadelphia, Pa.: W.B. Saunders Company, 1976, pp. 1-450.

Bray G.A. A Guide to Obesity and the Metabolic Syndrome: Origins and Treatment . New York: CRC Press: Taylor and Francis Group. 2011.

Howard AN. The history of the association for the study of obesity. Intern J Obes. 1992;16:S1–8.

Bray GA, Greenwood MRC, Hansen BC. The obesity society is turning 40: a history of the early years. Obesity. 2021;29(Dec):1978–81.

McLean Baird I, Howard AN. Obesity: Medical and Scientific Aspects : Proceedings of the First Symposium of the Obesity Association of Great Britain held in London , October 1968. Edinburgh & London: E. S. Livingston, 1968.

Bray GA, Howard AN. Founding of the international journal of obesity: a journey in medical journalism. Int J Obes. 2015;39:75–9.

Bray G. The founding of obesity research/obesity: a brief history. Obes. 2022;30:2100–2.

Ziman J. The Force of Knowledge. The Scientific Dimension of Society . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process: a position paper of world obesity. Obes Rev. 2017;18:715–23.

Bray GA. Obesity is a chronic, relapsing neurochemical disease. Intern J Obes. 2004;28:34–8.

Allison DB, Downey M, Atkinson RL, Billington CJ, Bray GA, Eckel RH, et al. Obesity as a disease: a white paper on evidence and arguments commissioned by the Council of the Obesity Society. Obes. 2008;16:1161–77.

Garvey WT, Garber AJ, Mechanick JI, Bray GA, Dagogo-Jack S, Einhorn D, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology position statement on the 2014 advanced framework for a new diagnosis of obesity as a chronic disease. Endocr Pr. 2014;20:977–89.

Bray GA, Ryan DH. Evidence-based weight loss interventions: individualized treatment options to maximize patient outcomes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23:50–62.

Ge L, Sadeghirad B, Ball GDC, da Costa BR, Hitchcock CL, Svendrovski A, et al. Comparison of dietary macronutrient patterns of 14 popular named dietary programmes for weight and cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2020;369:m696.

Sjöström L, Rissanen A, Andersen T, Boldrin M, Golay A, Koppeschaar HP, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of orlistat for weight loss and prevention of weight regain in obese patients. European Multicentre Orlistat Study Group. Lancet 1998;352:167–72.

Pi-Sunyer FX, Aronne LJ, Heshmati HM, Devin J, Rosenstock J. Effect of rimonabant, a cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker, on weight and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight or obese patients: RIO-North America: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006;295:761–75.

Foster GD, Wadden TA, Vogt RA, Brewer G. What is a reasonable weight loss? Patients’ expectations and evaluations of obesity treatment outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:79–85.

DiFeliceantonio AG, Coppin G, Rigoux L, Thanarajah ES, Dagher A, Tittgemeyer M, et al. Supra-additive effects of combining fat and carbohydrate on food reward. Cell Metab. 2018;28:33–44.e3.

Thanarajah SE, Backes H, DiFeliceantonio AG, Albus K, Cremer AL, Hanssen R, et al. Food intake recruits orosensory and post-ingestive dopaminergic circuits to affect eating desire in humans. Cell Metab. 2019;29:695–706.e4.

Bray GA. Is sugar addictive? Diabetes 2016;65:1797–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Dr. Jennifer Lyn Baker for her helpful comments during the early stage of preparing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Pennington Biomedical Research Center/LSU, Baton Rouge, LA, 70808, USA

George A. Bray

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All contributions were made by the single author.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to George A. Bray .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

MSS # 2023IJO01171.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bray, G.A. Obesity: a 100 year perspective. Int J Obes (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01530-6

Download citation

Received : 13 November 2023

Revised : 23 April 2024

Accepted : 26 April 2024

Published : 07 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01530-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Prevention and Management of Childhood Obesity and its Psychological and Health Comorbidities

Justin d. smith.

1 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Preventive Medicine, and Department of Pediatrics, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, 750 N. Lake Shore Drive, Illinois, 60611, USA

2 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 750 N. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois, 60611, USA

Marissa Kobayashi

3 Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, 1120 NW 14th Street, Suite 1009, Miami, FL 33136. Phone: (305) 972-9961

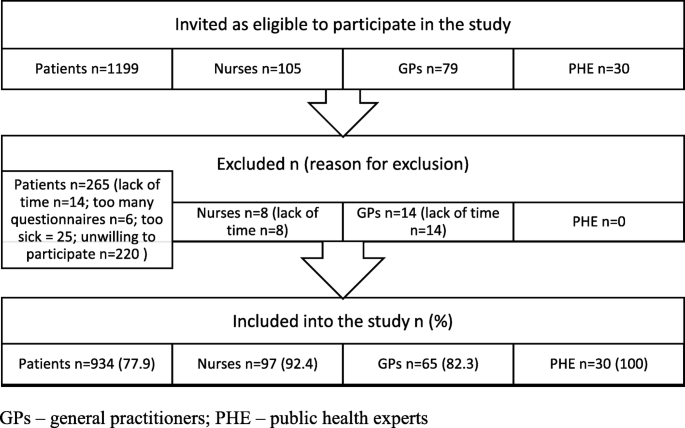

Childhood obesity has become a global pandemic in developed countries, leading to a host of medical conditions that contribute to increased morbidity and premature death. The causes of obesity in childhood and adolescence are complex and multifaceted, presenting researchers and clinicians with myriad challenges in preventing and managing the problem. This chapter reviews the state-of-the-science for understanding the etiology of childhood obesity, the preventive interventions and treatment options for overweight and obesity, and the medical complications and co-occurring psychological conditions that result from excess adiposity, such as hypertension, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and depression. Interventions across the developmental span, varying risk levels, and service contexts (e.g., community, school, home, and healthcare systems) are reviewed. Future directions for research are offered with an emphasis on translational issues for taking evidence-based interventions to scale in a manner that reduce the public health burden of the childhood obesity pandemic.

1.0. INTRODUCTION

Influenced by genetics, biology, psychosocial factors, and health behaviors, overweight and obesity (OW/OB) in childhood is a complex public health problem affecting the majority of developed countries worldwide. Additionally, the key contributors to obesity—poor diet and physical inactivity—are among the leading causes of preventable youth deaths, chronic disease, and economic health burden ( Friedemann et al 2012 , Hamilton et al 2018 ). Despite the remarkable need to prevent childhood obesity and to intervene earlier to prevent excess weight gain in later developmental periods, few interventions have demonstrated long-lasting effects or been implemented at such a scale to have an appreciable public health impact ( Hales et al 2018 ).

In this review, we describe the extent and nature of the childhood obesity pandemic, present conceptual and theoretical models for understanding its etiology, and take a translational-developmental perspective in reviewing intervention approaches within and across developmental stages and in the various contexts in which childhood OW/OB interventions are delivered. We pay particular attention to co-occurring psychological conditions intertwined with OW/OB for children, adolescents, and their families as they relate to both development/etiology and to intervention. For this reason, our review begins with interventions aimed at prevention and moves to management and treatment options for obesity and its psychological and medical comorbidities. Then, we discuss the state-of-the-science and expert recommendations for interventions to prevent and manage childhood OW/OB and what it would take to implement current evidence-based programs at scale. Last, we end by discussing identified gaps in the literature to inform future directions for research and the translation of research findings to real-world practice that can curb the pandemic. For readability, we use the term “interventions for the prevention and management of childhood OW/OB” to capture an array of approaches referred to by a variety of monikers in the literature, including primary prevention, prevention of excess weight gain, weight loss intervention, weight management, and treatment of obesity. More specific labels are used when needed.

2.0. EPIDEMIOLOGY OF CHILDHOOD OBESITY

Childhood OW/OB is determined by the child’s height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI), which is adjusted according to norms based on the child’s age and gender. BMI between the 85th and 94th percentile is in the “overweight” range, whereas BMI ≥ 95 th percentile for age and gender is in the “obese” range ( Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2018 ). Rates of obesity among children and adolescents in developed countries worldwide, collected in 2013, were 12.9% for boys and 13.4% for girls ( Ng et al 2014 ). In the United States (US) from 1999–2016, 18.4% of children ages 2–19 years had obesity, and 5.2% had severe obesity, defined as BMI ≥120% of the 95th percentile for age and gender ( Skinner et al 2018 ). The prevalence of obesity has increased between 2011–2012 and 2015–2016 in children ages 2–5 and 16–19 years ( Hales et al 2018 ). Being in the obese range during childhood or adolescence makes the youth five times more likely to be obese in adulthood compared to peers who maintain a healthy weight ( Simmonds et al 2016 ). Compared to obesity, severe obesity is strongly linked with greater cardiometabolic risk, adult obesity, and premature death ( Skinner et al 2015 ).

OW/OB and its health consequences are disproportionately distributed across the US, with a higher prevalence among children of disadvantaged racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. Rates of OW/OB are significantly higher among Non-Hispanic black and Hispanic children compared to Non-Hispanic White children (e.g., Hales et al 2018 ). Such disparities are particularly pronounced among severe obesity, where 12.8% of African American children, and 12.4% of Hispanic children have severe obesity compared to 5.0% of Non-Hispanic White children ( Hales et al 2018 ). Youth in low socioeconomic households are more likely to develop OW/OB compared to their counterparts in high socioeconomic households. In 2011–2014, 18.9% of children ages 2–19 living in the lowest income group (≤130% of Federal Poverty Line) had obesity, whereas 10.9% of children in the highest income group (>350% Federal Poverty Line) had obesity ( Ogden et al 2018 ). Influences on multiple socioecological levels put racially diverse children of low socioeconomic status (SES) at higher risk of developing OW/OB, which is further exacerbated by limited access to health services that can prevent excess weight gain and its sequelae.

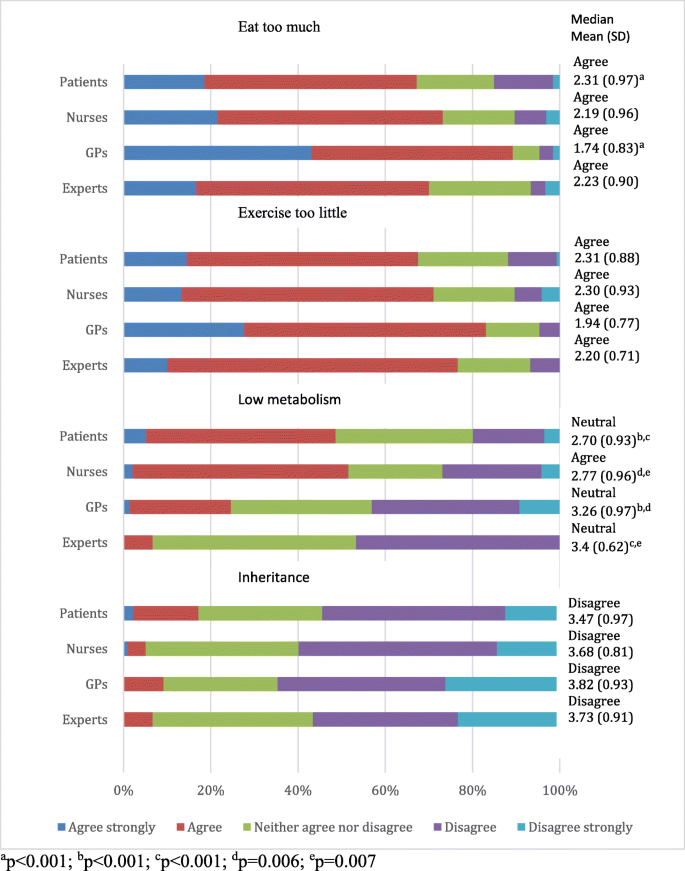

3.0. ETIOLOGY OF CHILDHOOD OBESITY

At the most basic level, childhood OW/OB emerges from consuming more calories than expended, resulting in excess weight gain and an excess body fat. Caloric imbalance is the result of, and can be further exacerbated by, a range of obesogenic behaviors. That is, behaviors that are highly correlated with excess weight gain. The most common obesogenic behaviors are high consumption of sugar sweetened beverages and low-nutrient, high saturated fat foods, low levels of physical activity and high levels of sedentary behaviors, and shortened sleep duration (e.g., Sisson et al 2016 ). Diet, physical activity, screen time, and sleep patterns are influenced by a myriad of factors and interactions involving genetics, interpersonal relationships, environment, and community (e.g., Russell & Russell 2019 , Smith et al 2018d ). Children living in the United States commonly consume the “Western Diet,” known as a diet high in calories, rich in sugars, trans and saturated fats, salt and food additives, and low in complex carbohydrates, and vitamins. Poor sleep patterns, defined as short duration and late timing, can contribute to obesity through changing levels of appetite-regulating hormones, and irregular eating patterns including late night snacking and eating ( Miller et al 2015 ). Children who experience shortened night time sleep from infancy to school age are at increased risk of developing OW/OB compared to same-aged children sleeping average, age-specific hours (e.g., Taveras et al 2014 ). Research indicates that children with higher rates of screen time also consume high levels of energy-dense snacks, beverages, and fast food, and fewer fruits and vegetables, and screen time is hypothesized to affect food and beverage consumption through distracted eating, reducing feelings of satiety or fullness, and exposure to advertisements for junk food (sweet and salty, calorically-dense foods) ( Robinson et al 2017 ). Screen time can also negatively affect children’s sleeping patterns, and is correlated with sedentary behaviors (e.g., watching television, playing video games) ( Hale & Guan 2015 ).

3.1. Conceptual Models for Understanding and Addressing Childhood OW/OB

Conceptualizing development of childhood OW/OB requires consideration of interplay of genetic, biological, psychological, behavioral, interpersonal, and environment factors ( Kumar & Kelly 2017 ). OW/OB interventions are typically designed to account for these multilevel factors to assist children in achieving expert recommendations for physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption, while limiting sugar sweetened beverages intake and screen time, and regulating sleep patterns ( Kakinami et al 2019 ). Creating behavioral change requires understanding of the multi-level interactions to identify opportunities for intervention to prevent excess weight gain long-term. A variety of conceptual models exist to explain potential interactions and individual influences leading to obesogenic behaviors and development of childhood OW/OB, and targets for improving health behaviors and routines. Importantly, basic science and conceptual models can be translated to develop effective, targeted intervention programs for prevention of excess weight gain.

3.1.1. Biopsychosocial model

The biopsychosocial model combines biological foundations in child development with environmental and psychosocial influences to identify and address mechanisms and processes to prevent and manage development of childhood OW/OB ( Russell & Russell 2019 ). This model features biological factors, such as genetics, alongside environmental, psychosocial, and behavioral risk factors (e.g., family disorganization, parenting skills, feeding practices, child appetite, temperament), and the development of self-regulation. Such an approach can illustrate developmental processes interacting with biological underpinnings that can be targeted in prevention and management interventions for OW/OB. Intervening from a biopsychosocial model involves cognitive behavioral and behavioral therapy to reframe thoughts and replace unhealthy eating behaviors with new habits.

3.1.2. Ecological systems theory (EST)

EST embeds individual development and change within multiple proximal and distal contexts and emphasizes the need to understand how an “ecological niche” can contribute to the development of specific characteristics, and how such niches are embedded in more distal contexts ( Davison & Birch 2001 ). For example, a child’s ecological niche can be the family or school, which are embedded in larger social contexts, such as the community and society. Individual child characteristics, such as gender and age, interact within and between the family and community context levels, which all influence development of OW/OB. The EST model presents various predictors of childhood OW/OB through identifying risk factors moderated by intraindividual child characteristics. The structure of the EST is present in various studies examining influences of community exposures and children’s individual attributes on weight outcomes.

3.1.3. The Six C’s Model

The Six-C’s is a developmental ecological model that includes environmental (family, community, country, societal), personal, behavioral, and hereditary influences, and a system for categorizing environmental influences, all of which can be adapted to each stage of child development from infancy to adolescence ( Harrison et al 2011 ). The Six C’s stand for: cell, child, clan, community, country, and culture, which represent biology/genetics, personal behaviors, family characteristics, factors outside of the home including peers and school, state and national-level institutions, and culture-specific norms, respectively. Each C includes factors that contribute to child obesity that occur and interact simultaneously throughout child development. For example, among preschool age children, obesity-predisposing genes (cell), excessive media exposure (child), parent dietary intake (clan), unhealthful peer food choices (community), national economic recession, (country) and oversized portions (culture), are all factors associated with obesity that can occur simultaneously and interact during this developmental stage.

3.1.3. The developmental cascade model of pediatric obesity

The model described in the Smith et al. (2018b) article offers a longitudinal framework to elucidate the way cumulative consequences and spreading effects of multiple risk and protective factors, across and within biopsychosocial spheres and phases of development, can propel children towards OW/OB outcomes. The cascade model of pediatric obesity ( Figure 1 ) was developed using a theory-driven model-building approach and a search of the literature to identify paths and relationships in the model that were empirically based. The model allows for different pathways and interactions between different combinations of variables and constructs that contribute to pediatric obesity (equifinality), identifying multi-level risk and protective factors spanning from the prenatal stage to adolescence stage. The complete model can, but has yet to, be tested. The model focuses on intra- and inter-individual child processes and mechanisms (e.g., parenting practices), while acknowledging that individuals are embedded within the broader ecological systems. St. George et al (in press) then conducted a systematic review of the intervention literature to elucidate the ways in which the developmental cascade model of childhood obesity can inform and is informed by intervention approaches for childhood OW/OB.

Note. Bold text indicates strongest support based on our review of the literature. Reprinted with permission from Taylor and Francis Group: Originally published in Smith JD, Egan KN, Montaño Z, Dawson-McClure S, Jake-Schoffman DE, et al. 2018. A developmental cascade perspective of paediatric obesity: Conceptual model and scoping review. Health Psychology Review 12: 271–293.

3.2. Psychosocial Contributors

3.2.1. maternal mental and physical health.

An emerging body of literature has shown a significant relationship between higher levels of parental stress and youths’ higher weight status and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors ( Tate et al 2015 ). In a prospective study, Stout et al (2015) found that fetal exposure to stress, as evidenced by elevated maternal cortisol and corticotropin-releasing hormone, was related to patterns of increasing BMI over the first 24 months of life. Children of mothers experiencing psychological distress and anxiety during pregnancy had higher fat mass, BMI, subcutaneous and visceral fat indices, liver fat fraction, and risk of obesity at age 10 years compared to those whose mothers did not ( Vehmeijer et al 2019 ). Early stress can have long-lasting effects, and studies from a nationally-representative cohort study have shown that postnatal maternal stress during the first year has a positive longitudinal relationship with the child’s BMI up to age 5 ( Leppert et al 2018 ), and psychological distress at age 5 was associated with risk of obesity at age 11 in another nationally-representative cohort ( Hope et al 2019 ). Among Hispanic children and adolescents whose caregivers reported ≥ 3 chronic stressors, Isasi et al (2017) found an increased likelihood of childhood obesity when compared to those whose parents reported no chronic stressors. In a systematic review assessing the impact of maternal stress on children’s weight-related behaviors, O’Connor et al (2017) found mixed evidence for the relationship specific to dietary intake; however, researchers found consistent evidence for the detrimental impact on youths’ physical activity and sedentary behavior, which was often conceptualized as screen time. Understandably, highly stressed parents may have an increased reliance on convenient fast-food options versus grocery shopping and preparing fresh and healthy meals for their children and may not have the energy or wherewithal to support their youths’ physical activity, nor engage in limit-setting behaviors specific to their children’s screen time.

One of the few studies using a longitudinal design did not replicate the relationship between high parental stress and lower levels of youth physical activity, but the relationship held for high levels of parental stress and increased fast food consumption ( Baskind et al 2019 ). Interestingly, this study observed an interaction effect on the relationship of high parental stress and childhood obesity by only low-income households and among ethnic minority children, specifically non-Hispanic black children—explaining one of the factors that contributes to healthy disparities for childhood obesity rates in the US. In another study using a large, prospective cohort, Shankardass et al (2014) found a significant effect of parental stress on BMI. The researchers also observed a significantly larger effect among Hispanics versus the total sample population, further noting that the relationship was weaker and not statistically significant among non-Hispanic children. Due to the salient role of caregiver stress on child health behaviors, it seems that interventions for childhood OW/OB should incorporate stress reduction strategies for parents while simultaneously focusing efforts on reaching racial/ethnic minority families and the economically disadvantaged.

Maternal mental health, most commonly operationalized as depressive symptoms and diagnosis, relate to children’s risk for OW/OB. The longitudinal effects of postnatal maternal depressive symptoms predicted obesity risk in preschool-age children, and unhealthier lifestyle behaviors, such as high TV viewing time and low levels of physical activity ( Benton et al 2015 ). Children of mothers with severe depression were more likely to be obese compared to children of mothers with fewer symptoms ( Marshall et al 2018 ). Maternal mental health could negatively affect child feeding behaviors such that elevated depressive symptoms in low-income mothers have been associated with increased use of feeding to soothe children ( Savage & Birch 2017 ). Few interventions for childhood obesity to date specifically target caregiver depression, but some protocols provide guidance to engage caregivers in services to manage depression and related stressors ( Smith et al 2018c ).

3.2.2. Child mental health

Poor self-regulation and related constructs such as reactivity and impulsivity, are prospective obesogenic risk factors ( Bergmeier et al 2014 , Smith et al 2018d ). A child’s temperament describes behavioral tendencies in reactivity and self-regulation. Negative reactivity is characterized by a quick response with intense negative affect, and is difficult to soothe. Infants and children with negative reactivity are at high risk of excess weight gain, and developing obesity later on and toddlers with low self-regulation and inability to control impulses or behavior are at increased risk for obesity and rapid weight over the subsequent nine years compared to toddlers with higher self-regulation abilities ( Graziano et al 2013 ). Poorer emotional self-regulation at age 3 is an independent predictor of obesity at age 11 ( Anderson et al 2017 ). On the other hand, the ability to delay gratification at age 4 is associated with lower BMI 30 years later ( Schlam et al 2013 ). It is possible that parents of children with difficult temperament experience challenges effectively managing children’s behaviors and setting limits, leading to irregular health routines and increased obesity risk ( Bergmeier et al 2014 , Smith et al 2018d ). Further, parents could overuse food and feeding to soothe children ( Anzman-Frasca et al 2012 ). Throughout childhood, emotional regulation deficits and other mental health disorders continue to predict obesity and weight gain. Emotional regulation in conjunction with stress during childhood is highly linked to low physical activity, emotional eating, irregular and disrupted sleep, and later development of obesity ( Aparicio et al 2016 ). A longitudinal study examining emotional psychopathology in preadolescence saw that boys diagnosed with a social phobia, panic disorder or dysthymia (persistent depressive disorder) had higher waist circumference and/or BMI, and girls diagnosed with dysthymia had increased waist circumference at the three-year follow-up ( Aparicio et al 2013 ). In a prospective study, overweight children who reported binge eating at ages 6–12 years gained 15% more fat mass over a period of four years compared to overweight children with no binge eating ( Tanofsky-Kraff et al 2006 ). The predictive role of mental health on physical health conditions and subsequent comorbidities can be costly and burdensome. Children with obesity-related health conditions (e.g., type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome) and a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis (e.g., depressive mood disorder, bipolar disorder, attachment disorder) have higher healthcare utilization and costs per year compared to children without a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis ( Janicke et al 2009a )

There is an association between OW/OB and depression in childhood and adolescence, but there is mixed evidence of the directionality of this effect among children and adolescents. A review of high quality studies by Mühlig et al (2016) saw that among nine studies examining the influence of depression on weight status, six found no significant influence. Of the studies that reported significant associations, one study saw effects only among female adolescents, another only for male adolescents, and a third showed effects of adolescent depressive symptoms on adult obesity at age 53 years only in women. Conversely, OW/OB status can have significant influences on risk of low self-esteem and depressive symptoms/diagnosis in adolescence, as discussed later in this paper.

3.2.3. Stigma/bullying

Weight-related stigma, defined as subtly or overtly having discriminatory actions against individuals with obesity, toward children with obesity can impair quality of life, and contributes to unhealthy behaviors that can worsen obesity such as social isolation, decreased physical activity, and avoidance of health care services ( Pont et al 2017 ). Unfortunately, stigma is widespread and tolerated in society, furthering the reach of negative harm. Children with obesity face explicit weight bias and stigma from multiple environments including from parents, obesity researchers, clinical settings, and school. Parents not only demonstrate implicit bias against childhood obesity, but also implicit and explicit biases against children with obesity ( Lydecker et al 2018 ). Even among obesity researchers and health professionals, significant implicit and explicit anti-fat bias, and explicit anti-fat attitudes increased between 2001–2013 ( Tomiyama et al 2015 ). Exposure to stigma and weight bias can have damaging psychosocial effects on children, such that stigma can mediate the relationship between BMI, depression, and body dissatisfaction ( Stevens et al 2017 ).

Weight stigma can also initiate bullying and weight related teasing, which can have serious psychological consequences such as depression among children, further weight gain and lessen motivation to change. A nationally representative sample of children ages 10–17 years saw that OW/OB adolescents were at higher odds of being a victim of bullying, and also higher odds of perpetrating bullying and victimizing others ( Rupp & McCoy 2019 ). The children at higher odds of engaging in bullying, or being bullied were also at significantly higher odds of having depression, difficulty making friends, and conduct problems compared to OW/OB adolescents who were not bullies or victims of bullying. The relationship between obesity and bullying needs to be addressed through bullying engagement, and coping skills for victimization to prevent and manage associated behavioral and depressive symptoms.

3.2.4. Family functioning and home environment

Evidence suggests a link between general family functioning, parent–child relationships, communication, and use of positive behavior support strategies and childhood OW/OB (see Smith et al 2017a ). Influence of general parenting styles, as opposed to the more specific feeding styles, have been extensively studied and linked to children’s diet, physical activity, and weight ( Shloim et al 2015 ). Children raised with an authoritative (warm and demanding) parenting style had healthier diet, higher physical activity levels, and lower BMI’s than those raised with the other styles ( Sleddens et al 2011 ). Parents proactively structuring home environments to support and positively reinforce healthy dietary and physical activity behaviors also play a key role in children’s healthy lifestyles ( Smith et al 2017b ). Children exposed to less supportive environments consisting of family stress, father absence, maternal depression, confinement, and unclean home environments at 1 year of age has been associated with high BMI at age 21 ( Bates et al 2018 ). Taken together, family participation and building parenting skills can play a salient role in the prevention of childhood OW/OB ( Pratt & Skelton 2018 , Wen et al 2011 ).

4.0. PREVENTION AND MANAGEMENT OF OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY

This section discusses the state-of-the-science in childhood OW/OB prevention and management along with salient factors related to their implementation in varied healthcare delivery systems. The current climate is being shaped by the position of the American Medical Association. In 2013, the Board voted to classify obesity as a disease that requires medical attention. This classification aimed to emphasize health risks of obesity, remove individual blame, and create new implications and opportunities for intervention. This classification can help to further: 1) a broader public understanding of the obesity condition and associated stigma; 2) prevention efforts; 3) research for treatment and management; 4) insurance reimbursement for intervention; and 5) medical education ( Kyle et al 2016 ). In primary healthcare settings specifically, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) gave childhood obesity screening and family-based intervention a “B” grade for evidence of effectiveness ( US Preventive Services Task Force 2017 ), which is sufficient to open insurance reimbursement streams for activities related to the prevention and management of childhood OW/OB that did not exist before. Reimbursement has been a significant barrier to uptake of effective interventions and the impact of the USPSTF in removing this impediment is not yet fully known.

A number of high-quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been published in recent years, which provide the most contemporary perspective of the effectiveness of interventions for prevention and management, as well as revealing wide variability and inconsistent findings. For example, Peirson et al (2015a) saw that prevention interventions were associated with slightly improved weight outcomes compared to control groups in mixed-weight children and adolescents. However, intervention effects were not consistent among each intervention strategy tested, suggesting that specific characteristics of the interventions, such as setting, participants, dose, and tailoring, should be examined to determine what is and is not effective in achieving desired outcomes.