Introductory Essay: Slavery and the Struggle for Abolition from the Colonial Period to the Civil War

How did the principles of the Declaration of Independence contribute to the quest to end slavery from colonial times to the outbreak of the Civil War?

- I can explain how slavery became codifed over time in the United States.

- I can explain how Founding principles in the Declaration of Independence strengthened anti-slavery thought and action.

- I can explain how territorial expansion intensified the national debate over slavery.

- I can explain various ways in which African Americans secured their own liberty from the colonial era to the Civil War.

- I can explain how African American leaders worked for the cause of abolition and equality.

Essential Vocabulary

Slavery and the struggle for abolition from the colonial period to the civil war.

The English established their first permanent settler colony in a place they called Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. Early seventeenth-century Virginia was abundant in land and scarce in laborers. Initially, the labor need was met mostly by propertyless English men and women who came to the new world as indentured servants hoping to become landowners themselves after their term of service ended. Such servitude was generally the status, too, of Africans in early British America, the first of whom were brought to Virginia by a Dutch vessel in 1619. But within a few decades, indentured servitude in the colonies gave way to lifelong, hereditary slavery, imposed exclusively on black Africans.

Because forced labor (whether indentured servitude or slavery) was a longstanding and common condition, the injustice of slavery troubled relatively few settlers during the colonial period. Southern colonies in particular codified slavery into law. Slavery became hereditary, with men, women, and children bought and sold as property, a condition known as chattel slavery . Opposition to slavery was mainly concentrated among Quakers , who believed in the equality of all men and women and therefore opposed slavery on moral grounds. Quaker opposition to slavery was seen as early as 1688, when a group of Quakers submitted a formal protest against the institution for discussion at a local meeting.

Anti-slavery sentiment strengthened during the era of the Revolution and Founding. Founding principles, based on natural law proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence and in several state constitutions, added philosophical force to biblically grounded ideas of human equality and dignity. Those principles informed free and enslaved blacks, including Prince Hall, Elizabeth Freeman, Quock Walker, and Belinda Sutton, who sent anti slavery petitions to state legislatures. Their powerful appeal to natural rights moved legislators and judges to implement the first wave of emancipation in the United States. Immediate emancipation in Massachusetts, gradual emancipation in other northern states, and private manumission in the upper South dealt blows against slavery and freed tens of thousands of people.

Slavery remained deeply entrenched and thousands remained enslaved, however, in states in both the upper and lower South , even as northern leaders believed the practice was on its way to extinction. The result was the set of compromises the Framers inscribed into the U.S. Constitution—lending slavery important protections but also preparing for its eventual abolition. The Constitution did not use the word “slave” or “slavery,” instead referring to those enslaved as “persons.” James Madison, the “father” of the Constitution, thus thought the document implicitly denied the legitimacy of a claim of property in another human being. The Constitution also restricted slavery’s growth by allowing Congress to ban the slave trade after 20 years. Out of those compromises grew extended controversies, however, the most heated and dangerous of which concerned the treatment of fugitive slaves and the status of slavery in federal territories.

The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 renewed and enhanced slavery’s profitability and expansion, which intensified both attachment and opposition to it. The first major flare-up occurred in 1819, when a dispute over whether Missouri would be admitted to the Union as a slave state or a free state generated threats of civil war among members of Congress. The adoption of the Missouri Compromise in 1820 quelled the anger for a time. But the dispute was reignited in the 1830s and continued to inflame the country’s political life through the Civil War.

A cotton gin on display at the Eli Whitney Museum by Tom Murphy VII, 2007.

“U.S. Cotton Production 1790–1834” by Bill of Rights Institute/Flickr, CC BY 4.0

Separating the sticky seeds from cotton fiber was slow, painstaking work. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin (gin being southern slang for engine) made the task much simpler, and cotton production in the lower South exploded. Cotton planters and their slaves moved to Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama to start new cotton plantations. Many planters in the Chesapeake region sold their slaves to cotton planters in the lower South. This created a massive interstate slave trade that transferred enslaved persons through auctions and forced marches in chains and that also broke up many slave families.

In 1831, in Virginia, a large-scale slave rebellion led by Nat Turner resulted in the deaths of approximately 60 whites and more than 100 blacks and generated alarm throughout the South. That same decade saw the emergence of a radicalized (and to a degree racially integrated) abolitionist movement, led by Massachusetts activist William Lloyd Garrison, and an equally radicalized pro slavery faction, led by U.S. Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina.

The polarization sharpened in subsequent decades. The Mexican-American War (1846–1848) brought large new western territories under U.S. control and renewed the contention in Congress over the status of slavery in federal territories. The complex 1850 Compromise, which included a new fugitive slave law heavily weighted in favor of slaveholders’ interests, did little to restore calm.

A few years later, Congress reopened the Kansas and Nebraska territories to slavery, thereby undoing the 1820 Missouri Compromise and rendering any further compromises unlikely. The U.S. Supreme Court tried vainly to settle the controversy by issuing, in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), the most pro-slavery ruling in its history. In 1858, Abraham Lincoln, a rising figure in the newly born Republican Party, declared the United States a “house divided” between slavery and freedom. In late 1859, militant abolitionist John Brown alarmed the South when he attempted to liberate slaves by taking over a federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. He was promptly captured, tried, and executed and thereupon became a martyr for many northern abolitionists.

Watch this BRI Homework Help video: Dred Scott v. Sandford for more information on the pivotal Dred Scott decision.

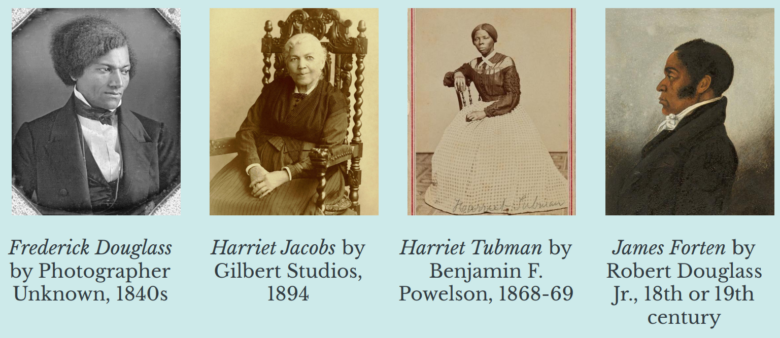

Leaders such as Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, Harriet Tubman, and James Forten all worked for the cause of abolition and equality.

As the debate over slavery continued on the national stage, formerly enslaved and free black men and women spoke out against the evils of slavery. Slave narratives such as those by Frederick Douglass, Solomon Northrup, and Harriet Jacobs humanized the experience of slavery. Their vivid, heartbreaking accounts of their own enslavement strengthened the moral cause of abolition. At the same time, enslaved men and women made the brave and dangerous decision to run away. Some ran on their own, and others used the Underground Railroad, a network of secret “conductors” and “stations” that helped enslaved people escape to the North and, after 1850, to Canada. The most famous of these conductors was Harriet Tubman, who traveled to the South about 12 times to lead approximately 70 men and women to freedom. Free blacks faced their own challenges. Leaders such as Benjamin Banneker, James Forten, David Walker, and Maria Stewart spoke out against racist attitudes and laws that sought to limit their political and civil rights.

This map shows the concentration of slaves in the southern United States as derived from the 1860 U.S. Census. The so-called “Border states”—Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and after 1863, West Virginia—allowed slavery but remained loyal to the Union. Credit: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

By 1860, the atmosphere in the United States was combustible. With the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in November of that year, the conflict over slavery came to a head. Since Lincoln and Republicans opposed the expansion of slavery and called it a moral evil, seven slaveholding states declared their secession from the United States. And in April 1861, the war came. The next five years of conflict and bloodshed determined the fate of enslaved men, women, and children, and of the Union itself.

Reading Comprehension Questions

- What actions were taken to oppose slavery in the colonial period and Founding era?

- Why did the Constitution not use the words “slave” or “slavery”?

- The invention of the cotton gin

- The Mexican-American War

- Dred Scott v. Sandford

- The election of Abraham Lincoln as president

- How did formerly enslaved and free black men and women fight to end slavery?

27f. The Southern Argument for Slavery

Those who defended slavery rose to the challenge set forth by the Abolitionists. The defenders of slavery included economics, history, religion, legality, social good, and even humanitarianism, to further their arguments.

Defenders of slavery argued that the sudden end to the slave economy would have had a profound and killing economic impact in the South where reliance on slave labor was the foundation of their economy. The cotton economy would collapse. The tobacco crop would dry in the fields. Rice would cease being profitable.

Defenders of slavery argued that if all the slaves were freed, there would be widespread unemployment and chaos. This would lead to uprisings, bloodshed, and anarchy. They pointed to the mob's "rule of terror" during the French Revolution and argued for the continuation of the status quo, which was providing for affluence and stability for the slaveholding class and for all free people who enjoyed the bounty of the slave society.

Defenders of slavery argued that slavery had existed throughout history and was the natural state of mankind. The Greeks had slaves, the Romans had slaves, and the English had slavery until very recently.

Defenders of slavery noted that in the Bible, Abraham had slaves. They point to the Ten Commandments, noting that "Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's house, ... nor his manservant, nor his maidservant." In the New Testament, Paul returned a runaway slave, Philemon, to his master, and, although slavery was widespread throughout the Roman world, Jesus never spoke out against it.

Defenders of slavery turned to the courts, who had ruled, with the Dred Scott Decision , that all blacks — not just slaves — had no legal standing as persons in our courts — they were property, and the Constitution protected slave-holders' rights to their property.

Defenders of slavery argued that the institution was divine, and that it brought Christianity to the heathen from across the ocean. Slavery was, according to this argument, a good thing for the enslaved. John C. Calhoun said, "Never before has the black race of Central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually."

Defenders of slavery argued that by comparison with the poor of Europe and the workers in the Northern states, that slaves were better cared for. They said that their owners would protect and assist them when they were sick and aged, unlike those who, once fired from their work, were left to fend helplessly for themselves.

James Thornwell , a minister, wrote in 1860, "The parties in this conflict are not merely Abolitionists and slaveholders, they are Atheists, Socialists, Communists, Red Republicans, Jacobins on the one side and the friends of order and regulated freedom on the other."

When a society forms around any institution, as the South did around slavery, it will formulate a set of arguments to support it. The Southerners held ever firmer to their arguments as the political tensions in the country drew us ever closer to the Civil War.

The Peculiar Institution Quiz

Instant quiz.

Report broken link

If you like our content, please share it on social media!

Copyright ©2008-2022 ushistory.org , owned by the Independence Hall Association in Philadelphia, founded 1942.

THE TEXT ON THIS PAGE IS NOT PUBLIC DOMAIN AND HAS NOT BEEN SHARED VIA A CC LICENCE. UNAUTHORIZED REPUBLICATION IS A COPYRIGHT VIOLATION Content Usage Permissions

Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation and Freedom

- Explore the Collection

- Collections in Context

- Teaching the Collection

- Advanced Collection Research

Civil War, 1861-1865

Jonathan Karp, Harvard University Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, PhD Candidate, American Studies

The story of the Civil War is often told as a triumph of freedom over slavery, using little more than a timeline of battles and a thin pile of legislation as plot points. Among those acts and skirmishes, addresses and battles, the Emancipation Proclamation is key: with a stroke of Abraham Lincoln’s pen, the story goes, slaves were freed and the goodness of the United States was confirmed. This narrative implies a kind of clarity that is not present in the historical record. What did emancipation actually mean? What did freedom mean? How would ideas of citizenship accommodate Black subjects? The everyday impact of these words—the way they might be lived in everyday life—were the subject of intense debates and investigations, which marshalled emerging scientific discourses and a rapidly expanding bureaucratic state. All the while, Black people kept emancipating themselves, showing by their very actions how freedom might be lived.

Self-Emancipation

The Emancipation Proclamation, in 1863, and the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, abolished slavery in the secessionist Confederate states and the United States, respectively, but it is important to remember that enslaved people were liberating themselves through all manners of fugitivity for as long as slavery has existed in the Americas. Notices from enslavers seeking self-emancipated Black people were common in newspapers throughout the Americas, as seen in this 1854 copy of the Baltimore Sun .

The question of how formerly enslaved people would be regarded by and assimilated into the state as subjects was most obviously worked out through the Freedmen’s Bureau, which was meant to support newly freed people across the South. Two years before the Bureau was established, however, there was the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission. Authorized by the Secretary of War in March 1863, the Inquiry Commission was called in part as a response to the ever-increasing number of refugees—who were still referred to at the time as “contraband”—appearing at Union camps. The three appointed commissioners—Samuel Gridley Howe, James McKaye, and Robert Dale Owen—were charged with investigating the condition and capacity of freedpeople.

Historians are still working to understand the scale of refugees’ movements during the Civil War. Abigail Cooper estimates that by 1865 there were around 600,000 freedpeople in 250 refugee camps. Many of the camps were overseen by the Union, while others were established and run by freedpeople themselves. Conditions in the camps could be brutal. In 1863, the Inquiry Commission heard that 3,000 freedmen had fortified the fort in Nashville for fifteen months without pay. Rations were slim. In spite of these conditions, the camps were also sites where Black people profoundly restructured the South by their very movement and relationships.

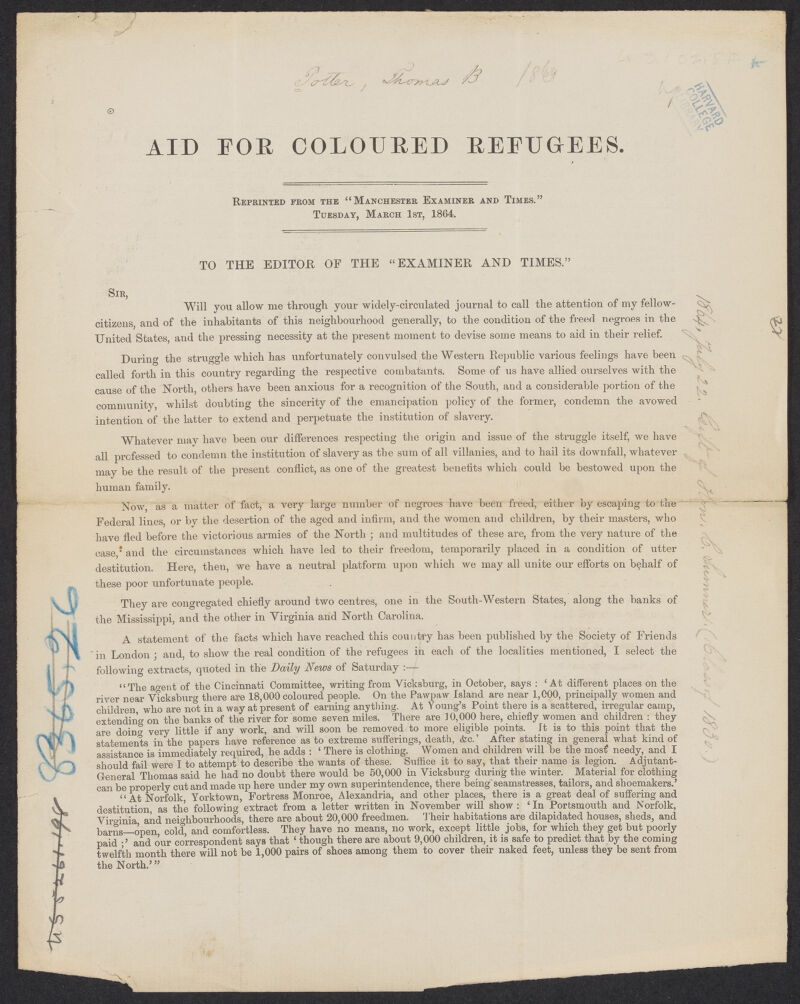

Port Royal Experiment

During the Civil War, the U.S. government began an experiment in the Sea Islands of South Carolina. Plantation owning enslavers had abandoned their lands, leaving behind over 10,000 formerly enslaved Black people. With the help of abolitionist charities from the North, these Black farmers cultivated cotton for wages in the same places they had formerly been held in bondage. Their work was so successful that it inspired international calls for support, like this letter published in Manchester, England. The short-lived success of this experiment was largely ended at the government's hands, when the lands were returned to White ownership.

The Inquiry Commission, a large portion of whose records are held at Harvard, focused many of their efforts on the camps. It was not clear how, exactly, they should go about their work. The Commission was established before the field of sociology emerged with its institutionalized tools for the supposedly scientific study of populations. A federal body had never before been responsible studying people who were or had been enslaved. The commissioners travelled across the American South and Canada, observing and interviewing freedmen. They sent elaborate surveys to military leaders, clergy, and other White people who interfaced with large numbers of people who had escaped slavery. Through this work, the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission made Black people into subjects of the United States’ scientific gaze. Their records are an invaluable record of life under slavery; they also reinscribed underlying racial logics.

Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation, and Freedom has a collection of 189 objects related to the Commission’s inquiry . The vast majority of them are responses to their survey, written by White people the Commission identified as having special knowledge of freedmen. The view of slavery from this vantage point is limited. Most if not all of the respondents recount conversations with people who were or had been enslaved, but these accounts are all mediated by their authors and the Commissioners. There’s no telling what the quoted enslaved people would or wouldn’t have shared with these people, or why. If some shape of life under slavery emerges from reading these survey responses, it is a necessarily distorted one. The American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission is emblematic of a style of scientific discourse that set its sights on Black people and the cultural meanings of race without concern for the views of Black people. In this field, Whiteness was necessary for expertise.

The surveys are most revealing as records of how these agents of the federal government conceived of the question of freedom—what they called, “one of the gravest social problems ever presented a government.” What kinds of questions did they ask? The forms had forty-two questions. Some asked for geographic and population data. Others asked for information about life before emancipation: did freedmen carry signs of previous abuse (they did) and did their masters have an effect on enslaved peoples’ families (they invariably did)? The vast majority of the questions, however, asked for the respondent’s opinions and general observations of the formerly enslaved refugees. The Commission wanted to know about these peoples’ strength, endurance, intellectual capacity, attachments to place, as well as their religious devotion, their general disposition, work ethic, and ways of domestic life. The list ended with the most important question, which the previous ones had apparently prepared the respondent to answer to the best of their abilities: “In your judgement are the freedmen in your department considered as a whole fit to take their place in society with a fair prospect of self-support and progress or do they need preparatory training and guardianship? If so of what nature and to what extent?”

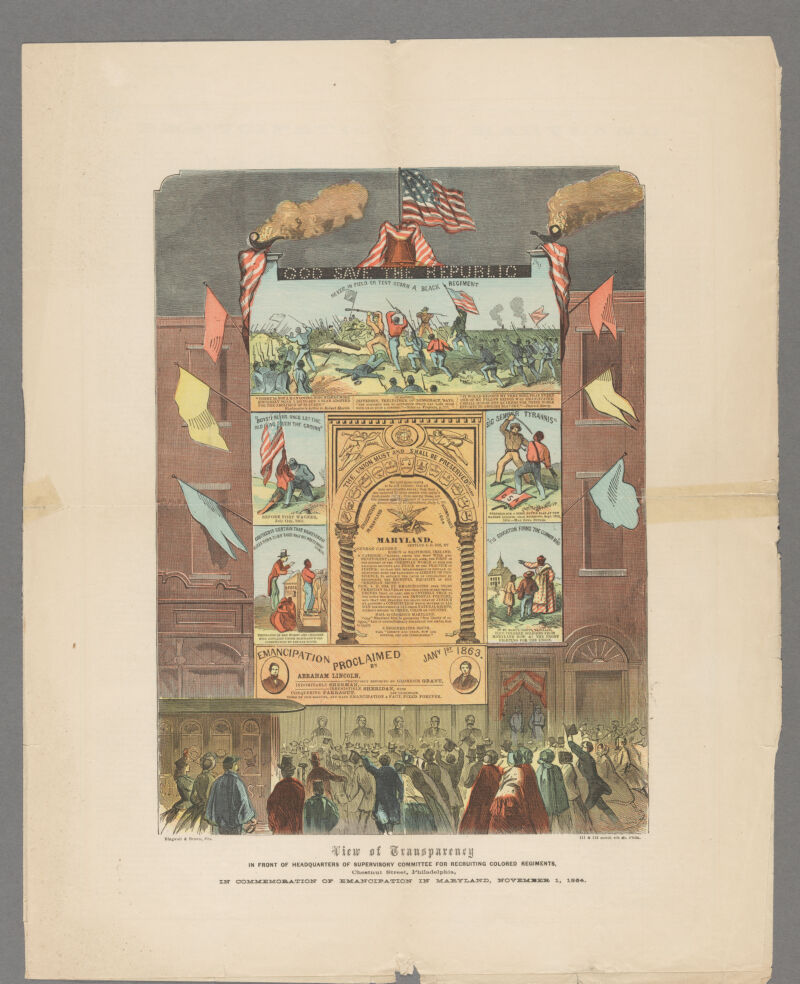

Slow Stretching Emancipation

The Emancipation Proclamation was widely celebrated by enemies of slavery, though it did not emancipate all enslaved Black peoples. Celebrations were held in Northern cities like Philadelphia and Boston . News of emancipation was slow moving, even in areas that were covered by the proclamation. In areas under Union control, like Port Royal, Black people were informed of their new legal status on January 1st, but in areas under Confederate control the proclamation was often kept secret from enslaved people or entirely ignored. In his memoir, Up from Slavery, Booker T. Washington described his experience learning of the proclamation:

After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased. My mother, who was standing by my side, leaned over and kissed her children, while tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She explained to us what it all meant, that this was the day for which she had been so long praying, but fearing that she would never live to see. Booker T. Washington, Up from Slavery: An Autobiography, pg. 21

From the questions the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission asked, it is clear that they imagined the freemen’s “fitness” to hinge on their ability to work for wages, own land, and maintain standard familial structures. The surveys asked whether freedmen “seemed disposed to continue their domestic relations or form new ones.” They asked whether, under slavery, enslaved children were taught to respect their parents. Commissioners wished to know if family names were common, and, if so, how they travelled through generations. The question about laboring for wages, which appeared towards the end of the questionnaire, was deeply connected to the question of what should come after slavery. If wages would not be successful in turning freedmen into laborers, a system of apprenticeship might be considered. The commissioners’ fixation on land was a result of the longstanding connection in the United States between citizenship and landowning. It was also a response to fears of Black migration. In all, the surveys show that the question of freedmen’s fitness was one of their assimilation into the intertwined relations of the capitalist wage and the family, as recognized by the state and church.

While the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission went about their work, freedpeople made their lives in ways that both answered the Commission’s questions and exceeded them. Some people found their way to camps to join the war effort; others went in search of family and still others made homes where they were. Washington Spradling, for example, told the Commission in 1863 how freedpeople in Kentucky pooled resources to pay for funerals and buy their relatives out of slavery, all under the oppression of new police powers. Across the South, as the Civil War raged, Black people brought about emancipation. They could not wait for the state’s commissions and reports. However, shades of their experiments in freedom are visible in the reports of the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission.

Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities

A Dissertation on Slavery: With a Proposal for the Gradual Abolition of It, In the State of Virginia (1796)

A Dissertation on Slavery: With a Proposal for the Gradual Abolition of It, In the State of Virginia (1796), is an essay by St. George Tucker . When he submitted it to the General Assembly in 1796, Tucker was a law professor at the College of William and Mary and a judge on the bench of the General Court. In A Dissertation on Slavery , he discusses the history of slavery, the Virginia slave code, and the morality of slaveholding, and presents a plan for ending slavery. He wrestles with the tensions between the natural rights philosophy of the American Revolution (1775–1783) and the continued existence of slavery. Tucker’s attempt to resolve this tension had little immediate effect—the House of Delegates tabled his proposal and Tucker believed that many of the assembly’s members refused even to read it—but it did point to a society that somewhat resembled late nineteenth and early twentieth century Virginia. In his essay, Tucker proposed that enslaved African Americans be freed, but, for various reasons, should not enjoy the full rights and privileges of citizenship. Some historians have since pointed out that this circumstance actually came to pass, if not in precisely the manner that Tucker had prescribed.

Tucker was born and raised in Bermuda, where half the population was enslaved. He moved to Virginia in 1772, around age nineteen, to attend the College of William and Mary and study law under the direction of George Wythe , one of the colony’s foremost legal minds. (Wythe had also tutored Thomas Jefferson in the law .) During the American Revolution, Tucker brought salt and gunpowder from Bermuda for the troops and served in the Virginia militia. He set up a legal practice in Petersburg after the war and was appointed to the General Court in 1788. In 1790, he took up Wythe’s law professorship while maintaining his position on the bench.

Tucker began to research and write his Dissertation in 1795, and it took him more than a year to complete. He began by corresponding with Jeremy Belknap of the Massachusetts Historical Society, a clergyman and historian whom Tucker hoped could tell him how Massachusetts had managed the peaceful abolition of slavery . Belknap passed along the professor’s questions to a number of prominent correspondents. Several of them noted that the end of slavery came not with a formal decree, but with the interpretation—or in the view of one correspondent, James Winthrop, the “misconstruction”—of the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. That document declares: “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties.” Belknap synthesized these various responses into a report.

In replying to this report, Tucker in effect provided a draft for his Dissertation on Slavery . He included in his response a plan of abolition that he thought his fellow Virginians might accept. By proposing a slow-moving course of action, Tucker hoped that he could convince the world—as he wrote in a letter to Belknap in 1795—”that the existence of slavery in this country is no longer to be deemed a reproach to the present generation.”

Tucker begins the essay by noting the “incompatibility” of slavery with the natural rights principles of the American Revolution. He therefore finds it impossible to justify the enslavement of black people “unless we first degrade them below the rank of human beings, not only politically, but also physically and morally.” Unwilling to take this step, Tucker argues that the time had come to accept the “moral truth” of the wrongness of slavery.

This assertion of modern natural rights seems a singularly inauspicious ground from which to defend slavery, but Tucker manages to do just that. He begins with an appeal to the right of self-preservation. The “recent history of the French West Indies”—referring to the slave revolt that began in Haiti in 1791 and led to Haitian independence in 1804—indicated the disastrous results that might follow large-scale emancipation. Employing the information he acquired from his correspondence with members of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Tucker notes that mass abolition had only proven successful in those states with a low ratio of slaves to free people. According to Tucker, Virginia had too high a ratio of slaves to free people. In some parts of the state “it is probable that there are four slaves for one free white man.” He argues that under such conditions, full-scale emancipation would produce famine at best and race war at worst.

With these considerations in mind, Tucker sets forth a very complicated plan of gradual emancipation. He pitches it as a revised version of gradual emancipation plans used in several northern states. First, all females born to slaves would serve twenty-eight-year indentures, after which their employers would give them twenty dollars and two suits of clothes. Children born to those serving such indentures must “be bound to service by the overseers of the poor, until they shall attain the age of twenty-one years.” This same agency would receive 15 percent of their wages when hired out for the short term, and 10 percent of their wages if they received an apprenticeship lasting for a year or more. If the master refused to pay freedom wages upon the arrival of the twenty-eighth year, he would have to pay the court a five-dollar fee.

Tucker’s plan denied freed slaves their basic civil liberties, including the right to keep weapons, to serve on juries, to testify against or marry white people, or even to write a will. Tucker justifies this course of action in the same way he had justified the continuance of slavery: by employing natural rights arguments and by noting the dangers created by the Haitian Revolution. Tucker argues that when dealing with people entering “into a state of society,” those already in the society have a right to “admit or exclude” anyone they wish. Thus he finds it consonant with natural rights to deny freed slaves the basic rights of citizens. He argues that the “recent scenes transacted” in Haiti “are enough to make one shudder with the apprehension of realizing similar calamities in this country.” Finding it impossible to propose a plan of emancipation that does not “either encounter, or accommodate [it]self to prejudice,” Tucker proposes a course that would negotiate what he saw as an acceptable mean between the evils of slavery and a mass emancipation that would “turn loose a numerous, starving, and enraged banditti upon the innocent descendants of their former oppressors.”

By restricting the civil liberties of freed slaves, Tucker hoped that he might encourage them to leave the state. “There is an immense unsettled territory on this continent more congenial to their natural constitutions than ours,” he writes, “where they may perhaps be received upon more favourable terms than we can permit them to remain with us.” Tucker saw the right to property as a natural right, but he doubted that the slave owner had a property right to an unborn child; besides, he argues, the planter would get at least fourteen years of good labor out of every slave born on his plantation. Tucker thought that his plan would win over skeptical slave owners. He enumerates the most surprising features of it: “the number of slaves will not be diminished for forty years after it takes place; that it will even increase for thirty years; that at the distance of sixty years, there will be one-third of the number at its first commencement; that it will require above a century to complete it; and that the number of blacks under twenty-eight, and consequently bound to service, in the families they are born in, will always be at least as great, as the present number of slaves.”

Contemporary Reception

Tucker, who published his 106-page essay in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, submitted a copy to the General Assembly in 1796. The House of Delegates quickly tabled it. Members of the Senate, having no power to propose legislation, saw the essay as less of a threat, and responded with a polite letter noting that they had received it. In a letter to Belknap in 1797, Tucker cites “mistaken self-interest and prejudice” as the primary enemies of the plan, and he tried “to elude, rather than invite, their attacks.” The effort failed; his essay remained virtually unknown. “Nobody, I believe has read it,” he complained to Belknap; “nobody could explain its contents.” Even if they had read it, Tucker doubted that anyone in the assembly would have been willing to take a stand on its behalf. That body was “split into factions, debating upon federal politics, and neither side probably wished to weaken its own influence by a division of sentiment among its partizans on any point whatever.”

Tucker also sent a copy of the Dissertation to Thomas Jefferson. The future president agreed with Tucker on both the means of emancipation and the urgency of the question. According to Jefferson, history would decide the question of emancipation for itself, regardless of the answer given by the slave owners. Jefferson believed that the consequences of failing to plan for emancipation would be disastrous. He saw all of America and Europe as ripe for insurrection, but he noted that only the southern states had to concern themselves with slave uprisings, which “a single spark” could produce at any time. If such an uprising were to come, Jefferson held out little hope that the other states would be of any assistance in putting it down.

Modern Reception

Many scholars have emphasized the connection between Tucker’s Dissertation and the ideology of natural rights. In All Honor to Jefferson? The Virginia Slavery Debates and the Positive Good Thesis (2008), Erik S. Root sees Tucker’s essay as evidence of the seriousness and consistency with which the Founding Fathers took these ideas. Similarly, the historian Phillip Hamilton, in an article published in 1998, argued that, “Tucker sought a middle ground on which to reconcile liberalism’s twin beliefs in basic human equality and the sanctity of all property.” In other words, Tucker wanted to find a way to end slavery without defrauding any creditors. Hamilton also places Tucker’s Dissertation in the context of a movement away from landed property as the basis of elite power in Virginia. Instead of this traditional mode of social organization, Tucker tried to base his independence on professional training for himself and his children.

In an article published in 2006, the legal historian Paul Finkelman assigns both praise and blame to Tucker’s Dissertation . On the one hand, “No other southerner of his generation offered a concrete proposal for ending slavery.” On the other hand, Tucker presented “a recipe for creating a permanent peasantry that Virginia’s landowners could exploit perpetually.” Tucker did so, however, in the hope that his proposal would “make Virginia a white person’s state in the long run.” Finkelman argues that if Tucker had followed this ideology through to conclusion he would have realized that a black peasantry also presented a threat to the self-preservation of white Virginians. “The peasants would provide more expensive labor but would not provide much greater safety.” Specifically, Virginia elites would find it easier to control slaves than they would to control a dispossessed class of free people.

Historians have long noted other ironies of this type surrounding the Dissertation . Winthrop Jordan, for instance, recognized Tucker’s essay as “startlingly portentous.” Tucker had called for a plan of emancipation that would take one hundred years. “A century later the Negro was free,” Jordan wrote in White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro (1968), “and in many areas of the South in a condition which, in an informal way, materially resembled the one he proposed.” Tucker thus made the point that natural rights do not always lead to civil rights, a lesson that has proved a bitter pill for Americans. Similarly, the historian Gordon S. Wood has noticed the unintended consequences of the natural rights critique of slavery. It forced those who defended slavery to couch their position in racial terms. In Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815 (2009), Wood argues, therefore, that, “The anti-slavery movement that emerged out of the Revolution inadvertently produced racism in America.”

- African American History

- Colonial History (ca. 1560–1763)

- Curtis, Michael Kent. “St. George Tucker and the Legacy of Slavery.” William and Mary Law Review IL (2006), 1157–1212.

- Finkelman, Paul. “The Dragon St. George Could Not Slay: Tucker’s Plan to End Slavery.” William and Mary Law Review IL (2006), 1213–1243.

- Hamilton, Phillip. “Revolutionary Principles and Family Loyalties: Slavery’s Transformation in the St. George Tucker Household of Early National Virginia.” William and Mary Quarterly 55, no. 4 (October 1998), 531–556.

- Hamilton, Phillip. The Making and Unmaking of a Revolutionary Family: The Tuckers of Virginia, 1752–1830 . Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003.

- Root, Erik S. All Honor to Jefferson? The Virginia Slavery Debates and the Positive Good Thesis . New York: Lexington Books, 2008.

- Jordan, Winthrop. White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968.

- Wood, Gordon S. Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815 . New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Name First Last

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Never Miss an Update

Partners & affiliates.

Encyclopedia Virginia 946 Grady Ave. Ste. 100 Charlottesville, VA 22903 (434) 924-3296

Indigenous Acknowledgment

Virginia Humanities acknowledges the Monacan Nation , the original people of the land and waters of our home in Charlottesville, Virginia.

We invite you to learn more about Indians in Virginia in our Encyclopedia Virginia .

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Emancipation Proclamation

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 29, 2023 | Original: October 29, 2009

On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that as of January 1, 1863, all enslaved people in the states currently engaged in rebellion against the Union “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

Lincoln didn’t actually free all of the approximately 4 million men, women and children held in slavery in the United States when he signed the formal Emancipation Proclamation the following January. The document applied only to enslaved people in the Confederacy, and not to those in the border states that remained loyal to the Union.

But although it was presented chiefly as a military measure, the proclamation marked a crucial shift in Lincoln’s views on slavery. Emancipation would redefine the Civil War , turning it from a struggle to preserve the Union to one focused on ending slavery, and set a decisive course for how the nation would be reshaped after that historic conflict.

Abe Lincoln's Developing Views on Slavery

Sectional tensions over slavery in the United States had been building for decades by 1854, when Congress’ passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened territory that had previously been closed to slavery according to the Missouri Compromise . Opposition to the act led to the formation of the Republican Party in 1854 and revived the failing political career of an Illinois lawyer named Abraham Lincoln, who rose from obscurity to national prominence and claimed the Republican nomination for president in 1860.

Lincoln personally hated slavery, and considered it immoral. "If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that 'all men are created equal;' and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man's making a slave of another," he said in a now-famous speech in Peoria, Illinois, in 1854. But Lincoln didn’t believe the Constitution gave the federal government the power to abolish it in the states where it already existed, only to prevent its establishment to new western territories that would eventually become states. In his first inaugural address in early 1861, he declared that he had “no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with slavery in the States where it exists.” By that time, however, seven Southern states had already seceded from the Union, forming the Confederate States of America and setting the stage for the Civil War.

First Years of the Civil War

At the outset of that conflict, Lincoln insisted that the war was not about freeing enslaved people in the South but about preserving the Union. Four border slave states (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri) remained on the Union side, and many others in the North also opposed abolition. When one of his generals, John C. Frémont, put Missouri under martial law, declaring that Confederate sympathizers would have their property seized, and their enslaved people would be freed (the first emancipation proclamation of the war), Lincoln directed him to reverse that policy, and later removed him from command.

But hundreds of enslaved men, women and children were fleeing to Union-controlled areas in the South, such as Fortress Monroe in Virginia, where Gen. Benjamin F. Butler had declared them “contraband” of war, defying the Fugitive Slave Law mandating their return to their owners. Abolitionists argued that freeing enslaved people in the South would help the Union win the war, as enslaved labor was vital to the Confederate war effort.

In July 1862, Congress passed the Militia Act, which allowed Black men to serve in the U.S. armed forces as laborers, and the Confiscation Act, which mandated that enslaved people seized from Confederate supporters would be declared forever free. Lincoln also tried to get the border states to agree to gradual emancipation, including compensation to enslavers, with little success. When abolitionists criticized him for not coming out with a stronger emancipation policy, Lincoln replied that he valued saving the Union over all else.

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union and is not either to save or to destroy slavery,” he wrote in an editorial published in the Daily National Intelligencer in August 1862. “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.”

From Preliminary to Formal Emancipation Proclamation

At the same time however, Lincoln’s cabinet was mulling over the document that would become the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln had written a draft in late July, and while some of his advisers supported it, others were anxious. William H. Seward, Lincoln’s secretary of state, urged the president to wait to announce emancipation until the Union won a significant victory on the battlefield, and Lincoln took his advice.

On September 17, 1862, Union troops halted the advance of Confederate forces led by Gen. Robert E. Lee near Sharpsburg, Maryland, in the Battle of Antietam . Days later, Lincoln went public with the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which called on all Confederate states to rejoin the Union within 100 days—by January 1, 1863—or their slaves would be declared “thenceforward, and forever free.”

On January 1, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, which included nothing about gradual emancipation, compensation for enslavers or Black emigration and colonization, a policy Lincoln had supported in the past. Lincoln justified emancipation as a wartime measure, and was careful to apply it only to the Confederate states currently in rebellion. Exempt from the proclamation were the four border slave states and all or parts of three Confederate states controlled by the Union Army.

Impact of the Emancipation Proclamation

As Lincoln’s decree applied only to territory outside the realm of his control, the Emancipation Proclamation had little actual effect on freeing any of the nation’s enslaved people. But its symbolic power was enormous, as it announced freedom for enslaved people as one of the North’s war aims, alongside preserving the Union itself. It also had practical effects: Nations like Britain and France, which had previously considered supporting the Confederacy to expand their power and influence, backed off due to their steadfast opposition to slavery. Black Americans were permitted to serve in the Union Army for the first time, and nearly 200,000 would do so by the end of the war.

Finally, the Emancipation Proclamation paved the way for the permanent abolition of slavery in the United States. As Lincoln and his allies in Congress realized emancipation would have no constitutional basis after the war ended, they soon began working to enact a Constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. By the end of January 1865, both houses of Congress had passed the 13th Amendment , and it was ratified that December.

"It is my greatest and most enduring contribution to the history of the war,” Lincoln said of emancipation in February 1865, two months before his assassination. “It is, in fact, the central act of my administration, and the great event of the 19th century."

HISTORY Vault: Abraham Lincoln

A definitive biography of the 16th U.S. president, the man who led the country during its bloodiest war and greatest crisis.

The Emancipation Proclamation, National Archives

10 Facts: The Emancipation Proclamation, American Battlefield Trust

Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W.W. Norton, 2010)

Allen C. Guelzo, “Emancipation and the Quest for Freedom.” National Park Service .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Self-Paced Courses : Explore American history with top historians at your own time and pace!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

Historical Context: The Constitution and Slavery

By steven mintz.

On the 200th anniversary of the ratification of the US Constitution, Thurgood Marshall, the first African American to sit on the Supreme Court, said that the Constitution was "defective from the start." He pointed out that the framers had left out a majority of Americans when they wrote the phrase, "We the People." While some members of the Constitutional Convention voiced "eloquent objections" to slavery, Marshall said they "consented to a document which laid a foundation for the tragic events which were to follow."

The word "slave" does not appear in the Constitution. The framers consciously avoided the word, recognizing that it would sully the document. Nevertheless, slavery received important protections in the Constitution. The notorious three-fifths clause—which counted three-fifths of a state’s slave population in apportioning representation—gave the South extra representation in the House of Representatives and extra votes in the Electoral College. Thomas Jefferson would have lost the election of 1800 if not for the Three-fifths Compromise. The Constitution also prohibited Congress from outlawing the Atlantic slave trade for twenty years. A fugitive slave clause required the return of runaway slaves to their owners. The Constitution gave the federal government the power to put down domestic rebellions, including slave insurrections.

The framers of the Constitution believed that concessions on slavery were the price for the support of southern delegates for a strong central government. They were convinced that if the Constitution restricted the slave trade, South Carolina and Georgia would refuse to join the Union. But by sidestepping the slavery issue, the framers left the seeds for future conflict. After the convention approved the great compromise, Madison wrote: "It seems now to be pretty well understood that the real difference of interests lies not between the large and small but between the northern and southern states. The institution of slavery and its consequences form the line of discrimination."

Of the 55 delegates to the Constitutional Convention, about 25 owned slaves. Many of the framers harbored moral qualms about slavery. Some, including Benjamin Franklin (a former slaveholder) and Alexander Hamilton (who was born in a slave colony in the British West Indies) became members of anti-slavery societies.

On August 21, 1787, a bitter debate broke out over a South Carolina proposal to prohibit the federal government from regulating the Atlantic slave trade. Luther Martin of Maryland, a slaveholder, said that the slave trade should be subject to federal regulation since the entire nation would be responsible for suppressing slave revolts. He also considered the slave trade contrary to America’s republican ideals. "It is inconsistent with the principles of the Revolution," he said, "and dishonorable to the American character to have such a feature in the constitution."

John Rutledge of South Carolina responded forcefully. "Religion and humanity have nothing to do with this question," he insisted. Unless regulation of the slave trade was left to the states, the southern-most states "shall not be parties to the union." A Virginia delegate, George Mason, who owned hundreds of slaves, spoke out against slavery in ringing terms. "Slavery," he said, "discourages arts and manufactures. The poor despise labor when performed by slaves." Slavery also corrupted slaveholders and threatened the country with divine punishment, he believed: "Every master of slaves is born a petty tyrant. They bring the judgment of heaven on a country."

Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut accused slaveholders from Maryland and Virginia of hypocrisy. They could afford to oppose the slave trade, he claimed, because "slaves multiply so fast in Virginia and Maryland that it is cheaper to raise than import them, whilst in the sickly rice swamps [of South Carolina and Georgia] foreign supplies are necessary." Ellsworth suggested that ending the slave trade would benefit slaveholders in the Chesapeake region, since the demand for slaves in other parts of the South would increase the price of slaves once the external supply was cut off.

The controversy over the Atlantic slave trade was ultimately settled by compromise. In exchange for a 20-year ban on any restrictions on the Atlantic slave trade, southern delegates agreed to remove a clause restricting the national government’s power to enact laws requiring goods to be shipped on American vessels (benefiting northeastern shipbuilders and sailors). The same day this agreement was reached, the convention also adopted the fugitive slave clause, requiring the return of runaway slaves to their owners.

Was the Constitution a proslavery document, as abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison claimed when he burned the document in 1854 and called it "a covenant with death and an agreement with Hell"? This question still provokes controversy. If the Constitution temporarily strengthened slavery, it also created a central government powerful enough to eventually abolish the institution.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade Essay

Many historians pay close attention to the reasons why slavery persisted for a long time in some parts of the United States. Moreover, much attention is paid to the reasons why so many southerners defended this social institution, even though they did not belong to the so-called plantation aristocracy.

To a great extent, this outcome can be attributed to such factors to the influence of racist attitudes, the fear of violence or rebellion, and economic interests of many people who perceived the abolition of slavery as a threat to their welfare. To some degree, these factors contributed to the outbreak of the American Civil War that dramatically transformed the social and political life of the country. These are the main details that should be examined.

The persistent defense of slavery can be partly explained by the widespread stereotypes and myths which were rather popular in the South. For instance, one can mention the belief according to which the living conditions of slaves were much better, especially in comparison with European workers or those people who lived in the northern parts of the United States. These arguments were expressed by John Calhoun who regarded slavery as “a positive good” (1837). This statement implied that black people could even be satisfied with their subordinate status.

He said that under the rule of white people, slaves could enjoy more prosperity (Calhoun, 1837). These are some of the details that should not be disregarded. To some degree, this justification of slavery was based on the belief that black people were not self-sufficient. Therefore, one should not neglect the impact of racism on the worldviews and attitudes of many southerners who did not always question the propaganda which was imposed on them.

Overall, pro-slavery politicians such as John Calhoun believed the abolition of slavery could produce only detrimental results on various stakeholders, including black people. These are some of the main details that should be distinguished. One should keep in mind that many people living in the South did not pay much attention to the experiences of black slaves. They did not reflect on the cruel treatment of black people who were often dehumanized.

Additionally, it is important to examine the experiences of people who did not belong to the upper classes of the Southern society. Many of these people were farmers, and they were adversely affected by the competition with slave owners (Davidson et al., 2012). In many cases, their farms could be ruined in the course of this struggle. Moreover, many of them could not even afford a slave (Davidson et al., 2012). Nevertheless, they did not object to the existence of slavery as a social institution.

They believed that that the emancipation of slaves could eventually threaten their own existence. In particular, many of them were afraid of violence or rebellion. This is one of the reasons why they did not support the abolitionist movement. So, they could reconcile themselves with slavery, even though their own interests were significantly impaired. Secondly, they did not perceive black people as human beings who could deserve empathy or compassion. As a result, many of these people defended slavery and even fought for the interests of slave owners. This is one of the details should not be overlooked because it is important for understanding the cause of the civic conflict in the United States.

It should be noted that trans-Atlantic slave trade was abolished long before the Civil War in the United States (Oldfield, 2012). Moreover, they could prohibit slave trade within a state. Nevertheless, policy-makers could not easily abolish slavery as an institution, even though many people believed that this practice violated every ethical law. There were many interest groups that did not want to abolish slavery. These people believed that their investments in commerce, agriculture, or industry could be harmed by the abolition of slavery (Davidson et al., 2012).

Moreover, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were many people who owned hundreds of slaves. They believed that slavery had been critical for their economic prosperity. As a result, there was no legal support of the abolitionist movement in some parts of the United States. This tendency was particularly relevant if one speaks about the South in which the use of slave labor was often required. This is one of the details that should be distinguished.

On the whole, this discussion indicates that there were several barriers to the abolition of slavery in the South. Much attention should be paid to the influence of racist attitudes of many people who were firmly convinced that slaves could be deprived of their right to humanity. In their opinion, this practice was quite acceptable from an ethical viewpoint. Additionally, it is vital to remember about the influence about the use of propaganda that shaped the attitudes of many people. Finally, one should not forget about the economic interests of many people who regarded the abolitionist movement as a threat to their financial security. These are some of the major aspects that can be identified.

Reference List

Calhoun, J. (1837). Slavery a Positive Good .

Davidson, J., Delay, B., Herman, B., Leigh, C., & Lytle, M. (2012). US: A Narrative History Volume 1: To 1877 . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Oldfield, J. (2012). British Anti-slavery . Web.

- Frederick Douglas and the Abolitionist Movement

- Abolitionist Movement: Attitudes to Slavery Reflected in the Media

- Abolition of Slavery in Brazil

- Confederation Articles and 1787 Constitution

- The Movie "GLORY 1989" by Edward Zwick Analysis

- The Grave Injustices of the Salem Witchcraft Trials

- The Three Rs of the New Deal in the United States History

- Peniel Joseph' Views on Barack Obama

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, April 30). Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade. https://ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-and-the-abolition-of-slave-trade/

"Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade." IvyPanda , 30 Apr. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-and-the-abolition-of-slave-trade/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade'. 30 April.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade." April 30, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-and-the-abolition-of-slave-trade/.

1. IvyPanda . "Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade." April 30, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-and-the-abolition-of-slave-trade/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Slavery and the Abolition of Slave Trade." April 30, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-and-the-abolition-of-slave-trade/.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.2: The Slavery Controversy and Abolitionist Literature

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 134196

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

After completing this section, you should be able to:

- Summarize the ways that Africans resisted slavery, the impact of that resistance, who was involved in anti-slavery movements, and the arguments they used to advance their cause

- Explain how slavery related to ideas of manifest destiny, the Western expansion, and the Mexican-American War

- Define the key abolitionist arguments of Garrison, Walker, and Mott, and distinguish their approaches from one another

- List the chief features of the slave narrative as a literary genre

- Distinguish similarities and differences between Douglass' and Jacobs' slave narratives, analyzing the roles gender and genre play in those distinctions

- Identify key turning points in Douglass' account of achieving freedom

- Outline the ways that Jacobs appealed specifically to women readers in the North

- Describe Stowe's appeal to her readers in Uncle Tom's Cabin and formulate hypotheses to explain its incredible popularity despite stereotypical representations of women and African Americans

- Analyze the role of Christianity, motherhood, and racialist representations in the antislavery arguments of Uncle Tom's Cabin

Slavery and the Debate over Abolition

Resistance and abolition.

Consider these questions as you read: In what ways did Africans resist slavery, and what was the impact of this resistance? Who was involved in anti-slavery movements, and how did the sentiment spread? What arguments did anti-slavery movements use to advance their cause?

Resistance to slavery came in many forms, all of which contributed to the abolition of slavery as an institution in the Americas in the second half of the nineteenth century. There were two main arms of resistance: that of slaves themselves and that of abolitionists, whose calls for the end of slavery became louder and more forceful beginning in the last two decades of the eighteenth century.

Africans resisted slavery in several ways. First, they adopted defensive measures in their own villages to elude capture by slavers. Second, they launched attacks on the crews aboard slave ships. Slavers' reports document over 400 such attacks, but scholars believe there were many more. Third, once ashore, Africans ran away, sometimes establishing Maroon communities. Maroon communities, such as those in Suriname and Jamaica, and the Republic of Palmares in Brazil, warred with white settlers throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Fourth, African slaves revolted on the very lands on which they were enslaved. The first slave revolt in the Americas we know of occurred in 1522 on the island of Hispaniola. This revolt, like most that would follow in the next 250 years, was quickly put down. During the late eighteenth century, however, the Americas saw an increase in slave revolts, especially in the French Caribbean. The French and Haitian Revolutions, which began in 1789 and 1791 respectively, largely inspired these revolts. Both revolutions were fought in the name of natural rights and the equality of men, ideas not lost on those who remained enslaved in the French colonial world. The French revolutionary government even abolished slavery in its colonies, although this did not last for very long, as slavery was soon reinstated during the reign of Napoleon. Slave revolts continued into the nineteenth century in British and Spanish Caribbean colonies. A revolt on the British-controlled island of Barbados in 1816 involved 20,000 slaves from over seventy plantations.

In 1831, a slave revolt in Virginia led by Nat Turner, although small in comparison with other slave revolts of the same period, became a symbol for slaveholders in the U.S. of the danger posed by abolition. For others, however, two decades of increased slave unrest supported calls for the end of slavery. These were the individuals involved in anti-slavery movements, which began gaining substantial ground with public opinion beginning in the 1780s. The anti-slavery movement was perhaps strongest in Britain, where member of Parliament William Wilberforce led anti-slavery campaigns from the 1780s onwards. Evangelical Protestant Christians joined him. These campaigns led to thousands of petitions to end slavery between the 1780s and 1830s. The slave trade was anti-slavery's first target and in 1787 the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was established in Britain. Wilberforce and evangelical Protestants saw slavery and slaveholders as evil. So, too, did the Quakers (or the Society of Friends). On both sides of the Atlantic, Quakers attacked slavery as immoral and prohibited their members from owning slaves or being involved in any part of the slave trade.

In addition to these moral attacks on slavery, Enlightenment thinkers attacked slavery on philosophical grounds. French Enlightenment philosophers such as Montesquieu argued that slavery went against the natural rights of man. During the French Revolution, members of the Society of the Friends of Blacks, which originated among Enlightenment thinkers, joined with free blacks from the Caribbean colonies living in France, who organized the Society of Colored Citizens, to advocate for equal rights for free people of color and the end of slavery. The anti-slavery movement scored a victory in 1807 when the United States and then Britain signed bills to end their nations' involvement in the slave trade. Many in the anti-slavery movement believed this was the first step to abolishing slavery as an institution.

The Library of Congress: "Abolition, Anti-Slavery Movements, and the Rise of the Sectional Controversy"

To better understand abolition, antislavery movements, and the rise of the sectional controversy, read this text, which provides a short overview of abolition with related images from the Library of Congress.

Black and white abolitionists in the first half of the nineteenth century waged a biracial assault against slavery. Their efforts proved to be extremely effective. Abolitionists focused attention on slavery and made it difficult to ignore. They heightened the rift that had threatened to destroy the unity of the nation even as early as the Constitutional Convention.

Although some Quakers were slaveholders, members of that religious group were among the earliest to protest the African slave trade, the perpetual bondage of its captives, and the practice of separating enslaved family members by sale to different masters.

As the nineteenth century progressed, many abolitionists united to form numerous antislavery societies. These groups sent petitions with thousands of signatures to Congress, held abolition meetings and conferences, boycotted products made with slave labor, printed mountains of literature, and gave innumerable speeches for their cause. Individual abolitionists sometimes advocated violent means for bringing slavery to an end.

Although black and white abolitionists often worked together, by the 1840s they differed in philosophy and method. While many white abolitionists focused only on slavery, black Americans tended to couple anti-slavery activities with demands for racial equality and justice.

Anti-Slavery Activists

Christian arguments against slavery.

Benjamin Lay, a Quaker who saw slavery as a "notorious sin", addresses this 1737 volume to those who "pretend to lay claim to the pure and holy Christian religion". Although some Quakers held slaves, no religious group was more outspoken against slavery from the seventeenth century until slavery's demise. Quaker petitions on behalf of the emancipation of African Americans flowed into colonial legislatures and later to the United States Congress.

Plea for the Suppression of the Slave Trade

In this plea for the abolition of the slave trade, Anthony Benezet, a Quaker of French Huguenot descent, pointed out that if buyers did not demand slaves, the supply would end. "Without purchasers", he argued, "there would be no trade; and consequently every purchaser as he encourages the trade, becomes partaker in the guilt of it". He contended that guilt existed on both sides of the Atlantic. There are Africans, he alleged, "who will sell their own children, kindred, or neighbors". Benezet also used the biblical maxim, "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you", to justify ending slavery. Insisting that emancipation alone would not solve the problems of people of color, Benezet opened schools to prepare them for more productive lives.

The Conflict Between Christianity and Slavery

Connecticut theologian Jonathan Edwards, born 1745, echoes Benezet's use of the Golden Rule as well as the natural rights arguments of the Revolutionary era to justify the abolition of slavery. In this printed version of his 1791 sermon to a local anti-slavery group, he notes the progress toward abolition in the North and predicts that through vigilant efforts slavery would be extinguished in the next fifty years.

Sojourner Truth

Abolitionist and women's rights advocate Sojourner Truth was enslaved in New York until she was an adult. Born Isabella Baumfree around the turn of the nineteenth century, her first language was Dutch. Owned by a series of masters, she was freed in 1827 by the New York Gradual Abolition Act and worked as a domestic. In 1843 she believed that she was called by God to travel around the nation--sojourn--and preach the truth of his word. Thus, she believed God gave her the name, Sojourner Truth. One of the ways that she supported her work was selling these calling cards.

Ye wives and ye mothers, your influence extend-- Ye sisters, ye daughters, the helpless defend-- The strong ties are severed for one crime alone, Possessing a colour less fair than your own.

Abolitionists understood the power of pictorial representations in drawing support for the cause of emancipation. As white and black women became more active in the 1830s as lecturers, petitioners, and meeting organizers, variations of this female supplicant motif, appealing for interracial sisterhood, appeared in newspapers, broadsides, and handicraft goods sold at fund-raising fairs.

Harriet Tubman--the Moses of Her People

The quote below, echoing Patrick Henry, is from this biography of underground railroad conductor Harriet Tubman:

Harriet was now left alone, . . . She turned her face toward the north, and fixing her eyes on the guiding star, and committing her way unto the Lord, she started again upon her long, lonely journey. She believed that there were one or two things she had a right to, liberty or death.

After making her own escape, Tubman returned to the South nineteen times to bring over three hundred fugitives to safety, including her own aged parents.

In a handwritten note on the title page of this book, Susan B. Anthony, who was an abolitionist as well as a suffragist, referred to Tubman as a "most wonderful woman".

Increasing Tide of Anti-slavery Organizations

In 1833, sixty abolitionist leaders from ten states met in Philadelphia to create a national organization to bring about immediate emancipation of all slaves. The American Anti-slavery Society elected officers and adopted a constitution and declaration. Drafted by William Lloyd Garrison, the declaration pledged its members to work for emancipation through non-violent actions of "moral suasion", or "the overthrow of prejudice by the power of love". The society encouraged public lectures, publications, civil disobedience, and the boycott of cotton and other slave-manufactured products.

William Lloyd Garrison--Abolitionist Strategies

White abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, born in 1805, had a particular fondness for poetry, which he believed to be "naturally and instinctively on the side of liberty". He used verse as a vehicle for enhancing anti-slavery sentiment. Garrison collected his work in Sonnets and Other Poems (1843).

During the 1840s, abolitionist societies used song to stir up enthusiasm at their meetings. To make songs easier to learn, new words were set to familiar tunes. This song by William Lloyd Garrison has six stanzas set to the tune of "Auld Lang Syne".

Popularizing Anti-Slavery Sentiment

Slave stealer branded.

Massachusetts sea captain Jonathan Walker, born in 1790, was apprehended off the coast of Florida for attempting to carry slaves who were members of his church denomination to freedom in the Bahamas in 1844. He was jailed for more than a year and branded with the letters "S.S." for slave stealer. The abolitionist poet John Greenleaf Whittier immortalized Walker's deed in this often reprinted verse: "Then lift that manly right hand, bold ploughman of the wave! Its branded palm shall prophesy, 'Salvation to the Slave!'"

Abolitionist Songsters

George W. Clark's, The Liberty Minstrel, is an exception among songsters in having music as well as words. "Minstrel" in the title has its earlier meaning of "wandering singer". Clark, a white musician, wrote some of the music himself; most of it, however, consists of well-known melodies to which anti-slavery words have been written. The book is open to a page containing lyrics to the tune of "Near the Lake", which appeared earlier in this exhibit (section 1, item 22) as "Long Time Ago". Note that there is an anti-slavery poem on the right-hand page. Like many songsters, The Liberty Minstrel contains an occasional poem.

Music was one of the most powerful weapons of the abolitionists. In 1848, William Wells Brown, abolitionist and former slave, published The Anti-Slavery Harp , "a collection of songs for anti-slavery meetings", which contains songs and occasional poems. The Anti-Slavery Harp is in the format of a "songster"--giving the lyrics and indicating the tunes to which they are to be sung, but with no music. The book is open to the pages containing lyrics to the tune of the "Marseillaise", the French national anthem, which to 19th-century Americans symbolized the determination to bring about freedom, by force if necessary.

Suffer the Children

This abolitionist tract, distributed by the Sunday School Union, uses actual life stories about slave children separated from their parents or mistreated by their masters to excite the sympathy of free children. Vivid illustrations help to reinforce the message that black children should have the same rights as white children, and that holding humans as property is "a sin against God".

Fugitive Slave Law

North to canada.

In the wake of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which forced Northern law enforcement officers to aid in the recapture of runaways, more than ten thousand fugitive slaves swelled the flood of those fleeing to Canada. The Colonial Church and School Society established mission schools in western Canada, particularly for children of fugitive slaves but open to all. The school's Mistress Williams notes that their success proves the "feasibility of educating together white and colored children". While primarily focusing on spiritual and secular educational operations, the report reproduces letters of thanks for food, clothing, shoes, and books sent from England. This early photograph accompanied one such letter to the children of St. Matthew's School, Bristol.

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

This controversial law allowed slave-hunters to seize alleged fugitive slaves without due process of law and prohibited anyone from aiding escaped fugitives or obstructing their recovery. Because it was often presumed that a black person was a slave, the law threatened the safety of all blacks, slave and free, and forced many Northerners to become more defiant in their support of fugitives. S. M. Africanus presents objections in prose and verse to justify noncompliance with this law.

Anthony Burns--Capture of A Fugitive Slave

This is a portrait of fugitive slave Anthony Burns, whose arrest and trial in Boston under the provisions of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 incited riots and protests by white and black abolitionists and citizens of Boston in the spring of 1854. The portrait is surrounded by scenes from his life, including his sale on the auction block, escape from Richmond, Virginia, capture and imprisonment in Boston, and his return to a vessel to transport him to the South. Within a year after his capture, abolitionists were able to raise enough money to purchase Burns's freedom.

Growing Sectionalism

Antebellum map showing the free and slave states.