The ethical case against sex-selective abortion isn’t simple

Lecturer in Global Ethics, Department of Philosophy, University of Birmingham

Disclosure statement

Jeremy Williams does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Birmingham provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

A key theme in public debate over abortion in many countries over the last few years has been the morality and legality of sex-selective terminations. Now the use of an early prenatal testing technique in the UK has led to further concerns.

The Non-Invasive Prenatal Test (NIPT) is being fully introduced on the NHS this year, as a safe method of detecting Down’s Syndrome and other genetic conditions. But it has been internationally available from private providers for a number of years, and, as a 2017 report noted , is often offered as a sex-determination test. This has raised concerns that the test may be used to facilitate sex-selective abortion – particularly within communities where women can be subject to strong cultural and familial pressure not to have girls. The current legal status of this practice in the UK is a matter of some controversy .

The BBC’s Victoria Derbyshire recently reported online discussion among British women about using NIPT to abort female foetuses. In response, the Labour Party announced a policy of banning the use of NIPT for sex determination. Labour’s equality and women’s spokesperson, Naz Shah, described sex-selective abortion as “incredibly unethical”.

Shah’s view – that sex-selective abortion is morally wrong, and that the law ought therefore to prevent it – is widely shared, including among those who otherwise identify as pro-choice. Similar sentiments were expressed by politicians in 2012, when an undercover investigation by the Telegraph found a number of doctors that appeared willing to perform sex-selective terminations.

But if you propose to deprive women of facts about their pregnancies, or interfere with choices they might make about their own bodies and futures, you must do more than allege wrongdoing. Articulation of a clear and compelling moral objection is required.

So: what kind of objections can be made in this case?

Sex discrimination

Sex-selective abortion is often dismissed as an abortion chosen due to a trivial preference, like a preference for one consumer product over another. And it would be natural to infer that it is therefore a classic case of unjust discrimination. What could be more obvious than that it is wrong to treat someone – in this case a foetus - less favourably simply on the arbitrary grounds of sex?

This characterisation of the practice is, however, dubious. Take first the thought that sex-selective abortion cannot be motivated by serious reasons. In fact, women who seek such abortions can have purposes that are just as weighty as those of women seeking non-selective terminations. They may be justifiably afraid, in particular, that the gender of their child may lead to the failure of their marriage, or their being left destitute. Cases described by the organisation Jeena International , for instance, show that it would be a mistake to assume that women in countries like the UK are necessarily immune to these risks. Yet, while Jeena International advocates the prohibition of sex selection, it is precisely when women face precarious circumstances like these that the option of abortion seems most crucial.

Consider next the suggestion that sex-selective abortion constitutes unjust discrimination against the foetus. This casts the foetus as having a right to be treated as our equal. But that idea undermines the case for abortion rights in general, not just sex-selective abortion.

Social impact

In order to avoid providing tacit support for a pro-life position, ethical critics of sex selection often argue that the practice’s victims are not foetuses, but existing persons in society. There are number of versions of this position, pointing to a variety of anticipated bad social consequences. The question is whether any are strong enough to justify abridging choice in an area of such deep personal importance as procreation.

One immediate fear is that, if sex-selective abortion is available, it could lead to harmful unbalancing of the sex ratio. This seems a fairly remote possibility in a country like the UK, at least, where strong son-preference is not widespread.

But another common rationale for prohibiting sex-selective abortion may be more applicable. It appears , for instance, to have been part of the motivation behind an (unsuccessful) attempt to change the law on sex selection by Fiona Bruce MP in 2015. On this view, a ban is needed to protect women from being coerced by their families or spouses into having the procedure.

Domestic coercion is undoubtedly a matter of grave concern. But it is unclear that prohibiting sex-selective abortion is the right remedy. This is because vulnerable women are at risk of being coerced into unwanted abortions generally. In all such cases, the appropriate policy is arguably instead to tackle domestic oppression directly, giving women meaningful exit options, while leaving abortion open to those who need it.

Tackling inequality

Yet another argument focuses on the message that allowing sex-selective abortion allegedly transmits. As one columnist evocatively puts the point : “I don’t want my daughter to learn that a girl’s life is worthless.” The suggestion here is that the existence of the practice vividly expresses the inferior status of women, making the struggle for gender equality still more difficult. But this case for prohibition can also be questioned on an ethical level.

One reason is that it is analogous to an argument that some disability rights advocates have made, to the effect that prenatal testing likewise broadcasts a hurtful, disrespectful message about the value of disabled lives. If someone were to argue, on these grounds, that selective abortion for disability is not only ethically problematic but ought to be banned, pro-choice people would no doubt reply (a) that there is no intention to express any such message, and (b) that in any case preventing women from obtaining needed abortions is not an equitable way of pursuing justice and equality for the disabled. These replies seem applicable in the case of sex selection too.

All this indicates that the ethical case for prohibition is less straightforward than one might expect. We can agree, of course, that much more progress needs to be made towards a world without the pervasive sex inequalities that lead some women to choose sex-selective abortion in the first place. But our problem is what to do here and now, while those inequalities persist. The dilemma is that, while such abortion can plausibly be seen as reinforcing relevant inequalities, prohibiting it arguably involves a perverse shift of the burdens of achieving gender justice onto vulnerable women themselves.

- Sexual selection

- Interdisciplinarity

Program Manager, Scholarly Development (Research)

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- America’s Abortion Quandary

1. Americans’ views on whether, and in what circumstances, abortion should be legal

Table of contents.

- Abortion at various stages of pregnancy

- Abortion and circumstances of pregnancy

- Parental notification for minors seeking abortion

- Penalties for abortions performed illegally

- Public views of what would change the number of abortions in the U.S.

- A majority of Americans say women should have more say in setting abortion policy in the U.S.

- How do certain arguments about abortion resonate with Americans?

- In their own words: How Americans feel about abortion

- Personal connections to abortion

- Religion’s impact on views about abortion

- Acknowledgments

- The American Trends Panel survey methodology

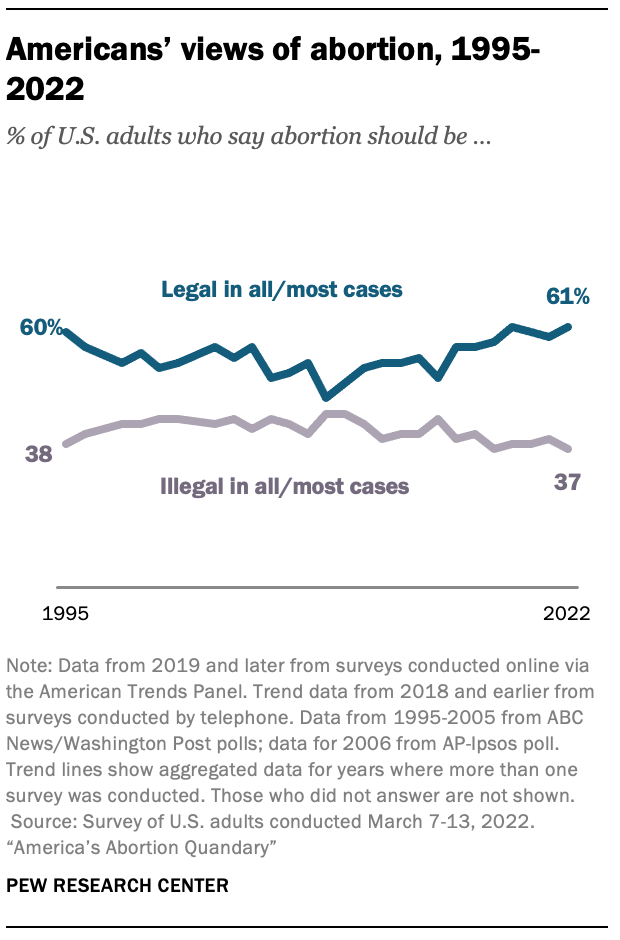

As the long-running debate over abortion reaches another key moment at the Supreme Court and in state legislatures across the country , a majority of U.S. adults continue to say that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. About six-in-ten Americans (61%) say abortion should be legal in “all” or “most” cases, while 37% think abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. These views have changed little over the past several years: In 2019, for example, 61% of adults said abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 38% said it should be illegal in all or most cases. Most respondents in the new survey took one of the middle options when first asked about their views on abortion, saying either that abortion should be legal in most cases (36%) or illegal in most cases (27%).

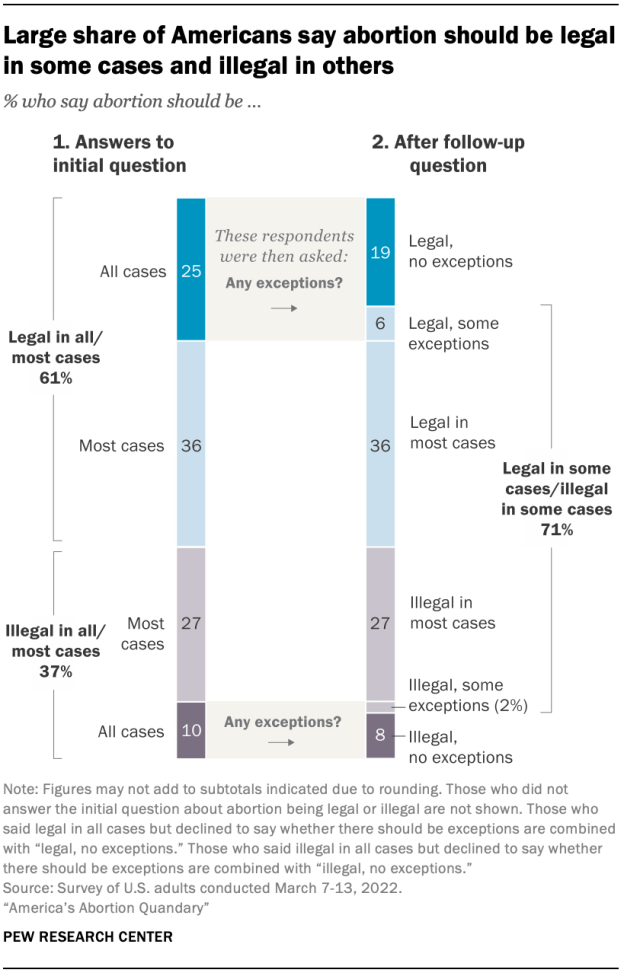

Respondents who said abortion should either be legal in all cases or illegal in all cases received a follow-up question asking whether there should be any exceptions to such laws. Overall, 25% of adults initially said abortion should be legal in all cases, but about a quarter of this group (6% of all U.S. adults) went on to say that there should be some exceptions when abortion should be against the law.

One-in-ten adults initially answered that abortion should be illegal in all cases, but about one-in-five of these respondents (2% of all U.S. adults) followed up by saying that there are some exceptions when abortion should be permitted.

Altogether, seven-in-ten Americans say abortion should be legal in some cases and illegal in others, including 42% who say abortion should be generally legal, but with some exceptions, and 29% who say it should be generally illegal, except in certain cases. Much smaller shares take absolutist views when it comes to the legality of abortion in the U.S., maintaining that abortion should be legal in all cases with no exceptions (19%) or illegal in all circumstances (8%).

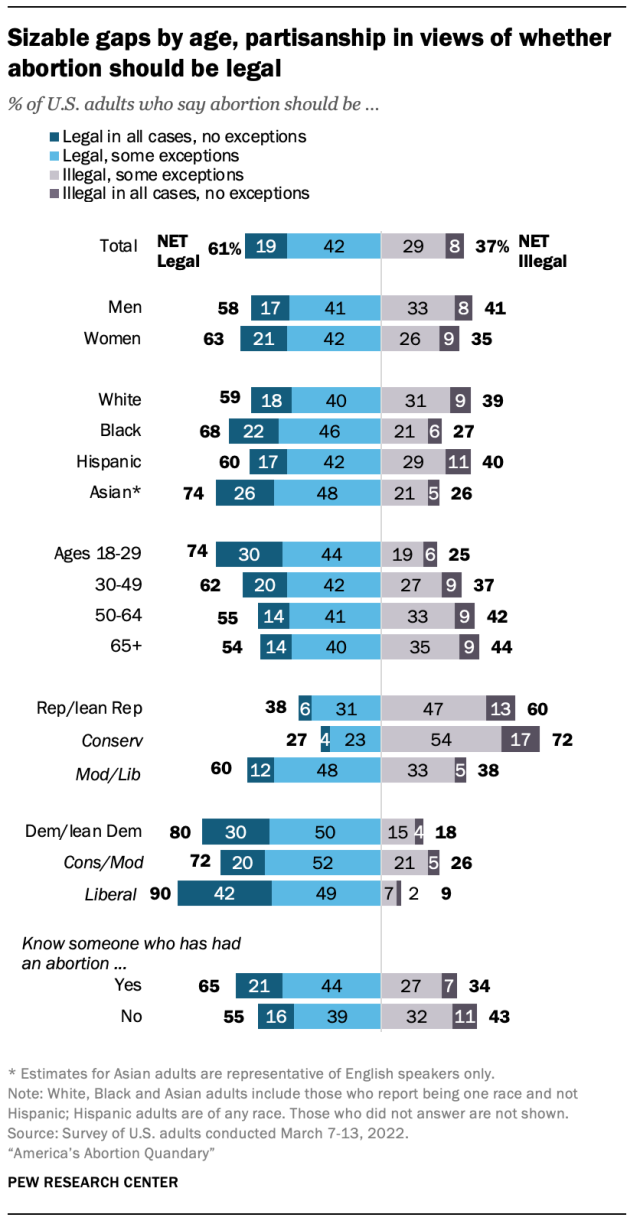

There is a modest gender gap in views of whether abortion should be legal, with women slightly more likely than men to say abortion should be legal in all cases or in all cases but with some exceptions (63% vs. 58%).

Younger adults are considerably more likely than older adults to say abortion should be legal: Three-quarters of adults under 30 (74%) say abortion should be generally legal, including 30% who say it should be legal in all cases without exception.

But there is an even larger gap in views toward abortion by partisanship: 80% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, compared with 38% of Republicans and GOP leaners. Previous Center research has shown this gap widening over the past 15 years.

Still, while partisans diverge in views of whether abortion should mostly be legal or illegal, most Democrats and Republicans do not view abortion in absolutist terms. Just 13% of Republicans say abortion should be against the law in all cases without exception; 47% say it should be illegal with some exceptions. And while three-in-ten Democrats say abortion should be permitted in all circumstances, half say it should mostly be legal – but with some exceptions.

There also are sizable divisions within both partisan coalitions by ideology. For instance, while a majority of moderate and liberal Republicans say abortion should mostly be legal (60%), just 27% of conservative Republicans say the same. Among Democrats, self-described liberals are twice as apt as moderates and conservatives to say abortion should be legal in all cases without exception (42% vs. 20%).

Regardless of partisan affiliation, adults who say they personally know someone who has had an abortion – such as a friend, relative or themselves – are more likely to say abortion should be legal than those who say they do not know anyone who had an abortion.

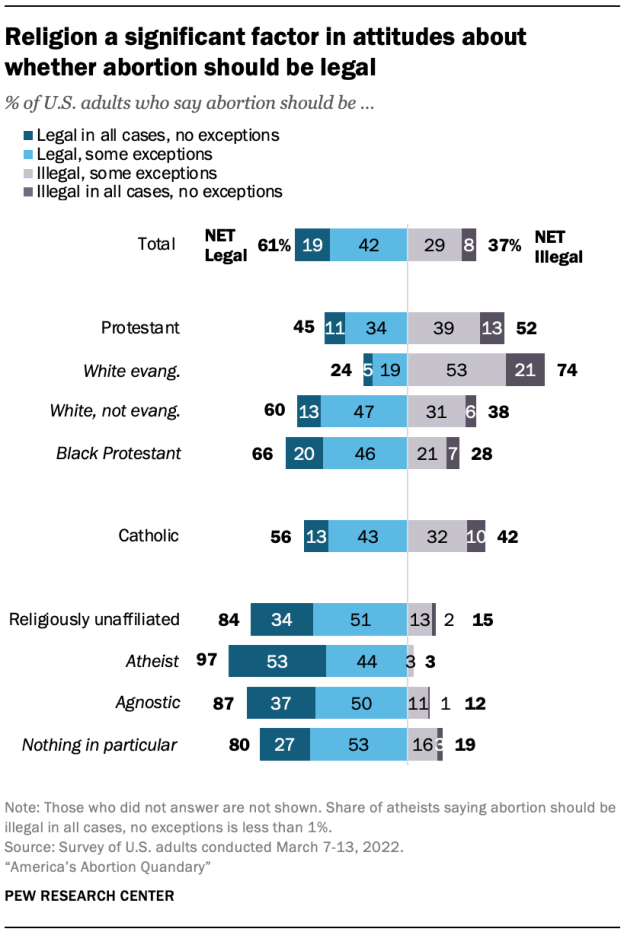

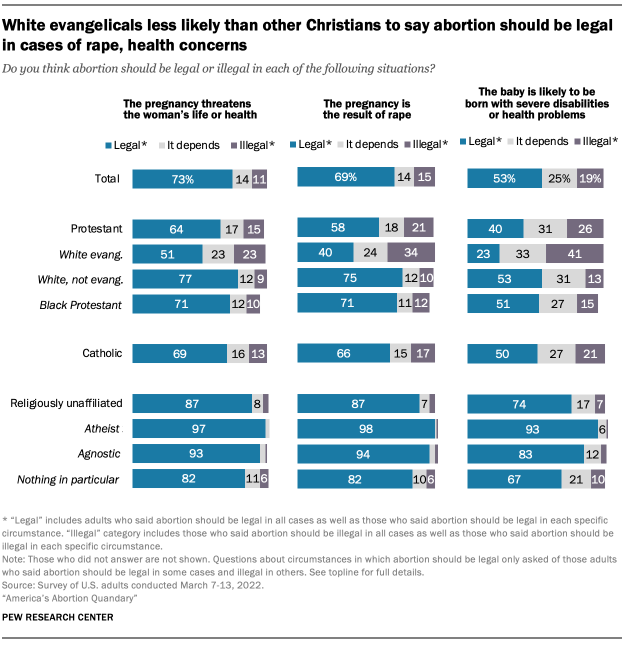

Views toward abortion also vary considerably by religious affiliation – specifically among large Christian subgroups and religiously unaffiliated Americans.

For example, roughly three-quarters of White evangelical Protestants say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. This is far higher than the share of White non-evangelical Protestants (38%) or Black Protestants (28%) who say the same.

Despite Catholic teaching on abortion , a slim majority of U.S. Catholics (56%) say abortion should be legal. This includes 13% who say it should be legal in all cases without exception, and 43% who say it should be legal, but with some exceptions.

Compared with Christians, religiously unaffiliated adults are far more likely to say abortion should be legal overall – and significantly more inclined to say it should be legal in all cases without exception. Within this group, atheists stand out: 97% say abortion should be legal, including 53% who say it should be legal in all cases without exception. Agnostics and those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” also overwhelmingly say that abortion should be legal, but they are more likely than atheists to say there are some circumstances when abortion should be against the law.

Although the survey was conducted among Americans of many religious backgrounds, including Jews, Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus, it did not obtain enough respondents from non-Christian groups to report separately on their responses.

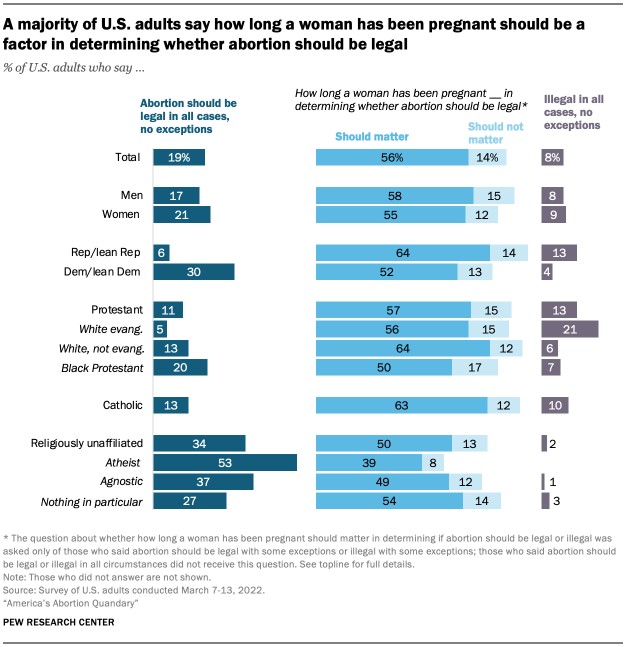

As a growing number of states debate legislation to restrict abortion – often after a certain stage of pregnancy – Americans express complex views about when abortion should generally be legal and when it should be against the law. Overall, a majority of adults (56%) say that how long a woman has been pregnant should matter in determining when abortion should be legal, while far fewer (14%) say that this should not be a factor. An additional one-quarter of the public says that abortion should either be legal (19%) or illegal (8%) in all circumstances without exception; these respondents did not receive this question.

Among men and women, Republicans and Democrats, and Christians and religious “nones” who do not take absolutist positions about abortion on either side of the debate, the prevailing view is that the stage of the pregnancy should be a factor in determining whether abortion should be legal.

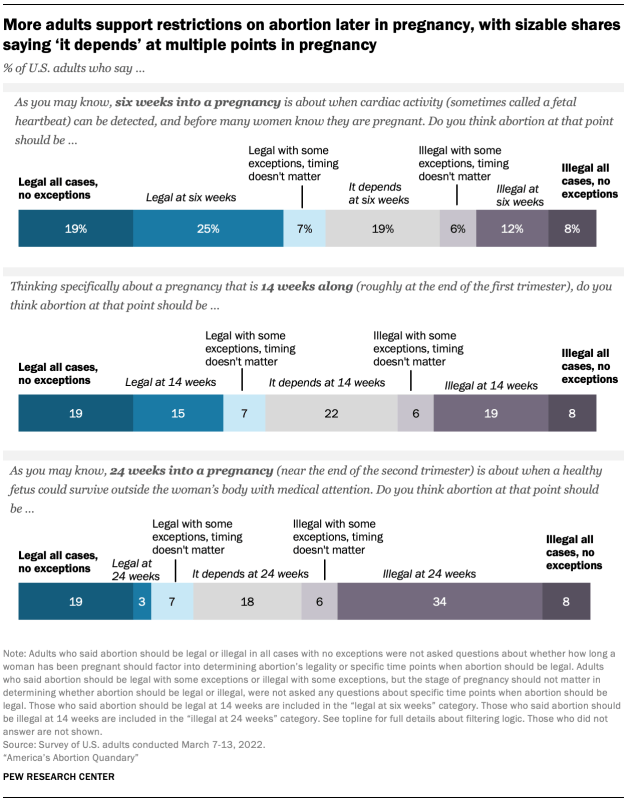

Americans broadly are more likely to favor restrictions on abortion later in pregnancy than earlier in pregnancy. Many adults also say the legality of abortion depends on other factors at every stage of pregnancy.

Overall, a plurality of adults (44%) say that abortion should be legal six weeks into a pregnancy, which is about when cardiac activity (sometimes called a fetal heartbeat) may be detected and before many women know they are pregnant; this includes 19% of adults who say abortion should be legal in all cases without exception, as well as 25% of adults who say it should be legal at that point in a pregnancy. An additional 7% say abortion generally should be legal in most cases, but that the stage of the pregnancy should not matter in determining legality. 1

One-in-five Americans (21%) say abortion should be illegal at six weeks. This includes 8% of adults who say abortion should be illegal in all cases without exception as well as 12% of adults who say that abortion should be illegal at this point. Additionally, 6% say abortion should be illegal in most cases and how long a woman has been pregnant should not matter in determining abortion’s legality. Nearly one-in-five respondents, when asked whether abortion should be legal six weeks into a pregnancy, say “it depends.”

Americans are more divided about what should be permitted 14 weeks into a pregnancy – roughly at the end of the first trimester – although still, more people say abortion should be legal at this stage (34%) than illegal (27%), and about one-in-five say “it depends.”

Fewer adults say abortion should be legal 24 weeks into a pregnancy – about when a healthy fetus could survive outside the womb with medical care. At this stage, 22% of adults say abortion should be legal, while nearly twice as many (43%) say it should be illegal . Again, about one-in-five adults (18%) say whether abortion should be legal at 24 weeks depends on other factors.

Respondents who said that abortion should be illegal 24 weeks into a pregnancy or that “it depends” were asked a follow-up question about whether abortion at that point should be legal if the pregnant woman’s life is in danger or the baby would be born with severe disabilities. Most who received this question say abortion in these circumstances should be legal (54%) or that it depends on other factors (40%). Just 4% of this group maintained that abortion should be illegal in this case.

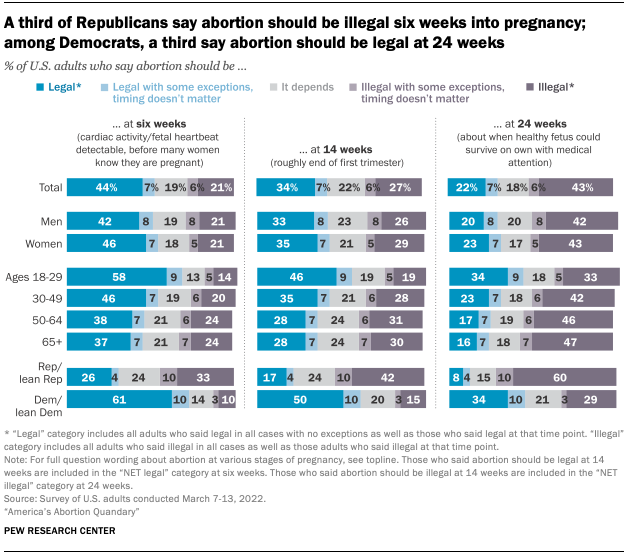

This pattern in views of abortion – whereby more favor greater restrictions on abortion as a pregnancy progresses – is evident across a variety of demographic and political groups.

Democrats are far more likely than Republicans to say that abortion should be legal at each of the three stages of pregnancy asked about on the survey. For example, while 26% of Republicans say abortion should be legal at six weeks of pregnancy, more than twice as many Democrats say the same (61%). Similarly, while about a third of Democrats say abortion should be legal at 24 weeks of pregnancy, just 8% of Republicans say the same.

However, neither Republicans nor Democrats uniformly express absolutist views about abortion throughout a pregnancy. Republicans are divided on abortion at six weeks: Roughly a quarter say it should be legal (26%), while a similar share say it depends (24%). A third say it should be illegal.

Democrats are divided about whether abortion should be legal or illegal at 24 weeks, with 34% saying it should be legal, 29% saying it should be illegal, and 21% saying it depends.

There also is considerable division among each partisan group by ideology. At six weeks of pregnancy, just one-in-five conservative Republicans (19%) say that abortion should be legal; moderate and liberal Republicans are twice as likely as their conservative counterparts to say this (39%).

At the same time, about half of liberal Democrats (48%) say abortion at 24 weeks should be legal, while 17% say it should be illegal. Among conservative and moderate Democrats, the pattern is reversed: A plurality (39%) say abortion at this stage should be illegal, while 24% say it should be legal.

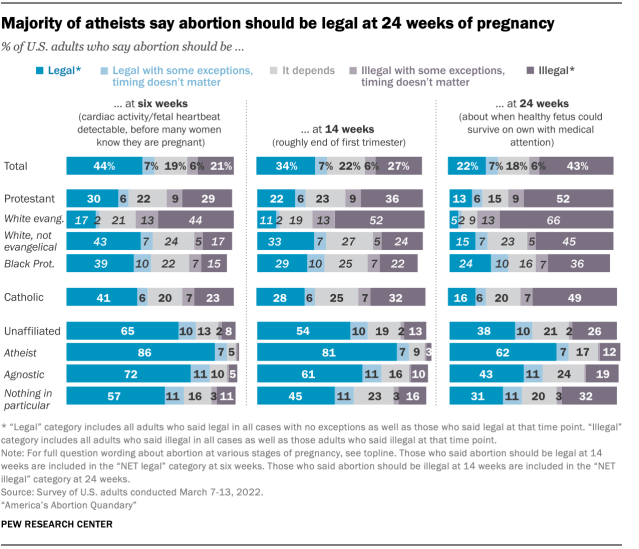

Christian adults are far less likely than religiously unaffiliated Americans to say abortion should be legal at each stage of pregnancy.

Among Protestants, White evangelicals stand out for their opposition to abortion. At six weeks of pregnancy, for example, 44% say abortion should be illegal, compared with 17% of White non-evangelical Protestants and 15% of Black Protestants. This pattern also is evident at 14 and 24 weeks of pregnancy, when half or more of White evangelicals say abortion should be illegal.

At six weeks, a plurality of Catholics (41%) say abortion should be legal, while smaller shares say it depends or it should be illegal. But by 24 weeks, about half of Catholics (49%) say abortion should be illegal.

Among adults who are religiously unaffiliated, atheists stand out for their views. They are the only group in which a sizable majority says abortion should be legal at each point in a pregnancy. Even at 24 weeks, 62% of self-described atheists say abortion should be legal, compared with smaller shares of agnostics (43%) and those who say their religion is “nothing in particular” (31%).

As is the case with adults overall, most religiously affiliated and religiously unaffiliated adults who originally say that abortion should be illegal or “it depends” at 24 weeks go on to say either it should be legal or it depends if the pregnant woman’s life is in danger or the baby would be born with severe disabilities. Few (4% and 5%, respectively) say abortion should be illegal at 24 weeks in these situations.

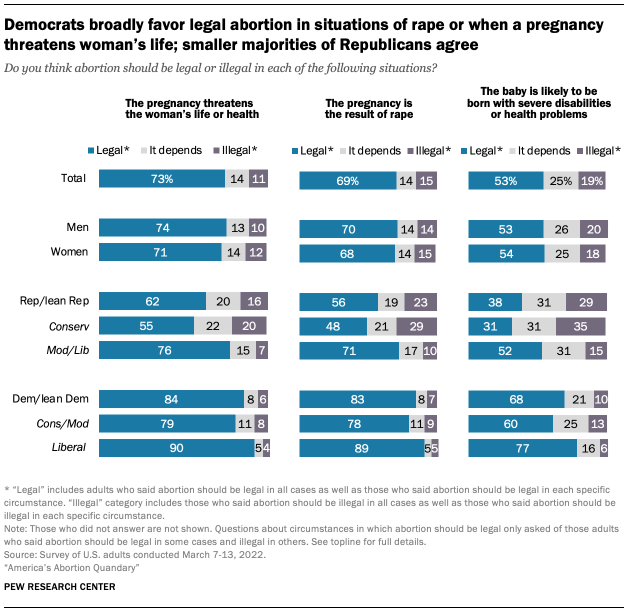

The stage of the pregnancy is not the only factor that shapes people’s views of when abortion should be legal. Sizable majorities of U.S. adults say that abortion should be legal if the pregnancy threatens the life or health of the pregnant woman (73%) or if pregnancy is the result of rape (69%).

There is less consensus when it comes to circumstances in which a baby may be born with severe disabilities or health problems: 53% of Americans overall say abortion should be legal in such circumstances, including 19% who say abortion should be legal in all cases and 35% who say there are some situations where abortions should be illegal, but that it should be legal in this specific type of case. A quarter of adults say “it depends” in this situation, and about one-in-five say it should be illegal (10% who say illegal in this specific circumstance and 8% who say illegal in all circumstances).

There are sizable divides between and among partisans when it comes to views of abortion in these situations. Overall, Republicans are less likely than Democrats to say abortion should be legal in each of the three circumstances outlined in the survey. However, both partisan groups are less likely to say abortion should be legal when the baby may be born with severe disabilities or health problems than when the woman’s life is in danger or the pregnancy is the result of rape.

Just as there are wide gaps among Republicans by ideology on whether how long a woman has been pregnant should be a factor in determining abortion’s legality, there are large gaps when it comes to circumstances in which abortions should be legal. For example, while a clear majority of moderate and liberal Republicans (71%) say abortion should be permitted when the pregnancy is the result of rape, conservative Republicans are more divided. About half (48%) say it should be legal in this situation, while 29% say it should be illegal and 21% say it depends.

The ideological gaps among Democrats are slightly less pronounced. Most Democrats say abortion should be legal in each of the three circumstances – just to varying degrees. While 77% of liberal Democrats say abortion should be legal if a baby will be born with severe disabilities or health problems, for example, a smaller majority of conservative and moderate Democrats (60%) say the same.

White evangelical Protestants again stand out for their views on abortion in various circumstances; they are far less likely than White non-evangelical or Black Protestants to say abortion should be legal across each of the three circumstances described in the survey.

While about half of White evangelical Protestants (51%) say abortion should be legal if a pregnancy threatens the woman’s life or health, clear majorities of other Protestant groups and Catholics say this should be the case. The same pattern holds in views of whether abortion should be legal if the pregnancy is the result of rape. Most White non-evangelical Protestants (75%), Black Protestants (71%) and Catholics (66%) say abortion should be permitted in this instance, while White evangelicals are more divided: 40% say it should be legal, while 34% say it should be illegal and about a quarter say it depends.

Mirroring the pattern seen among adults overall, opinions are more varied about a situation where a baby might be born with severe disabilities or health issues. For instance, half of Catholics say abortion should be legal in such cases, while 21% say it should be illegal and 27% say it depends on the situation.

Most religiously unaffiliated adults – including overwhelming majorities of self-described atheists – say abortion should be legal in each of the three circumstances.

Seven-in-ten U.S. adults say that doctors or other health care providers should be required to notify a parent or legal guardian if the pregnant woman seeking an abortion is under 18, while 28% say they should not be required to do so.

Women are slightly less likely than men to say this should be a requirement (67% vs. 74%). And younger adults are far less likely than those who are older to say a parent or guardian should be notified before a doctor performs an abortion on a pregnant woman who is under 18. In fact, about half of adults ages 18 to 24 (53%) say a doctor should not be required to notify a parent. By contrast, 64% of adults ages 25 to 29 say doctors should be required to notify parents of minors seeking an abortion, as do 68% of adults ages 30 to 49 and 78% of those 50 and older.

A large majority of Republicans (85%) say that a doctor should be required to notify the parents of a minor before an abortion, though conservative Republicans are somewhat more likely than moderate and liberal Republicans to take this position (90% vs. 77%).

The ideological divide is even more pronounced among Democrats. Overall, a slim majority of Democrats (57%) say a parent should be notified in this circumstance, but while 72% of conservative and moderate Democrats hold this view, just 39% of liberal Democrats agree.

By and large, most Protestant (81%) and Catholic (78%) adults say doctors should be required to notify parents of minors before an abortion. But religiously unaffiliated Americans are more divided. Majorities of both atheists (71%) and agnostics (58%) say doctors should not be required to notify parents of minors seeking an abortion, while six-in-ten of those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” say such notification should be required.

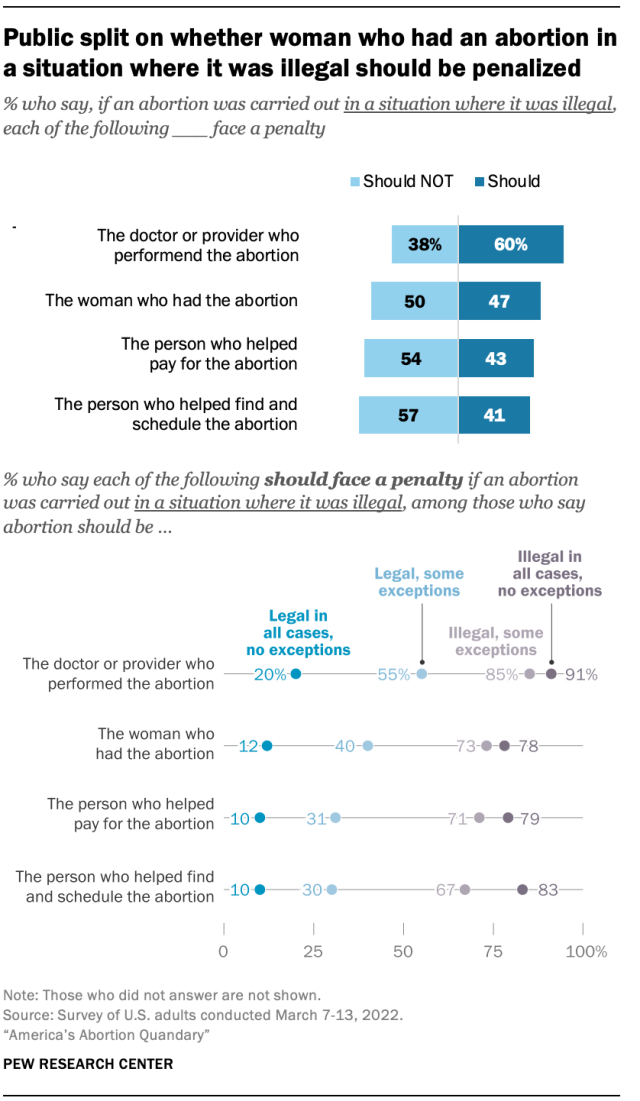

Americans are divided over who should be penalized – and what that penalty should be – in a situation where an abortion occurs illegally.

Overall, a 60% majority of adults say that if a doctor or provider performs an abortion in a situation where it is illegal, they should face a penalty. But there is less agreement when it comes to others who may have been involved in the procedure.

While about half of the public (47%) says a woman who has an illegal abortion should face a penalty, a nearly identical share (50%) says she should not. And adults are more likely to say people who help find and schedule or pay for an abortion in a situation where it is illegal should not face a penalty than they are to say they should.

Views about penalties are closely correlated with overall attitudes about whether abortion should be legal or illegal. For example, just 20% of adults who say abortion should be legal in all cases without exception think doctors or providers should face a penalty if an abortion were carried out in a situation where it was illegal. This compares with 91% of those who think abortion should be illegal in all cases without exceptions. Still, regardless of how they feel about whether abortion should be legal or not, Americans are more likely to say a doctor or provider should face a penalty compared with others involved in the procedure.

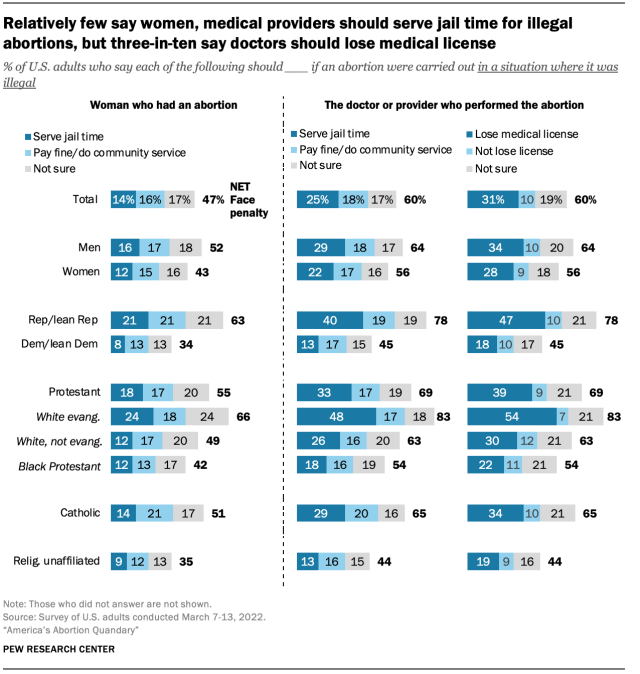

Among those who say medical providers and/or women should face penalties for illegal abortions, there is no consensus about whether they should get jail time or a less severe punishment. Among U.S. adults overall, 14% say women should serve jail time if they have an abortion in a situation where it is illegal, while 16% say they should receive a fine or community service and 17% say they are not sure what the penalty should be.

A somewhat larger share of Americans (25%) say doctors or other medical providers should face jail time for providing illegal abortion services, while 18% say they should face fines or community service and 17% are not sure. About three-in-ten U.S. adults (31%) say doctors should lose their medical license if they perform an abortion in a situation where it is illegal.

Men are more likely than women to favor penalties for the woman or doctor in situations where abortion is illegal. About half of men (52%) say women should face a penalty, while just 43% of women say the same. Similarly, about two-thirds of men (64%) say a doctor should face a penalty, while 56% of women agree.

Republicans are considerably more likely than Democrats to say both women and doctors should face penalties – including jail time. For example, 21% of Republicans say the woman who had the abortion should face jail time, and 40% say this about the doctor who performed the abortion. Among Democrats, far smaller shares say the woman (8%) or doctor (13%) should serve jail time.

White evangelical Protestants are more likely than other Protestant groups to favor penalties for abortions in situations where they are illegal. Fully 24% say the woman who had the abortion should serve time in jail, compared with just 12% of White non-evangelical Protestants or Black Protestants. And while about half of White evangelicals (48%) say doctors who perform illegal abortions should serve jail time, just 26% of White non-evangelical Protestants and 18% of Black Protestants share this view.

- Only respondents who said that abortion should be legal in some cases but not others and that how long a woman has been pregnant should matter in determining whether abortion should be legal received questions about abortion’s legality at specific points in the pregnancy. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Christianity

- Evangelicalism

- Political Issues

- Politics & Policy

- Protestantism

- Religion & Abortion

- Religion & Politics

- Religion & Social Values

Support for legal abortion is widespread in many places, especially in Europe

Public opinion on abortion, americans overwhelmingly say access to ivf is a good thing, broad public support for legal abortion persists 2 years after dobbs, americans are less likely than others around the world to feel close to people in their country or community, most popular, report materials.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

There’s a Better Way to Debate Abortion

Caution and epistemic humility can guide our approach.

If Justice Samuel Alito’s draft majority opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization becomes law, we will enter a post– Roe v. Wade world in which the laws governing abortion will be legislatively decided in 50 states.

In the short term, at least, the abortion debate will become even more inflamed than it has been. Overturning Roe , after all, would be a profound change not just in the law but in many people’s lives, shattering the assumption of millions of Americans that they have a constitutional right to an abortion.

This doesn’t mean Roe was correct. For the reasons Alito lays out, I believe that Roe was a terribly misguided decision, and that a wiser course would have been for the issue of abortion to have been given a democratic outlet, allowing even the losers “the satisfaction of a fair hearing and an honest fight,” in the words of the late Justice Antonin Scalia. Instead, for nearly half a century, Roe has been the law of the land. But even those who would welcome its undoing should acknowledge that its reversal could convulse the nation.

From the December 2019 issue: The dishonesty of the abortion debate

If we are going to debate abortion in every state, given how fractured and angry America is today, we need caution and epistemic humility to guide our approach.

We can start by acknowledging the inescapable ambiguities in this staggeringly complicated moral question. No matter one’s position on abortion, each of us should recognize that those who hold views different from our own have some valid points, and that the positions we embrace raise complicated issues. That realization alone should lead us to engage in this debate with a little more tolerance and a bit less certitude.

Many of those on the pro-life side exhibit a gap between the rhetoric they employ and the conclusions they actually seem to draw. In the 1990s, I had an exchange, via fax, with a pro-life thinker. During our dialogue, I pressed him on what he believed, morally speaking , should be the legal penalty for a woman who has an abortion and a doctor who performs one.

My point was a simple one: If he believed, as he claimed, that an abortion even moments after conception is the killing of an innocent child—that the fetus, from the instant of conception, is a human being deserving of all the moral and political rights granted to your neighbor next door—then the act ought to be treated, if not as murder, at least as manslaughter. Surely, given what my interlocutor considered to be the gravity of the offense, fining the doctor and taking no action against the mother would be morally incongruent. He was understandably uncomfortable with this line of questioning, unwilling to go to the places his premises led. When it comes to abortion, few people are.

Humane pro-life advocates respond that while an abortion is the taking of a human life, the woman having the abortion has been misled by our degraded culture into denying the humanity of the child. She is a victim of misinformation; she can’t be held accountable for what she doesn’t know. I’m not unsympathetic to this argument, but I think it ultimately falls short. In other contexts, insisting that people who committed atrocities because they truly believed the people against whom they were committing atrocities were less than human should be let off the hook doesn’t carry the day. I’m struggling to understand why it would in this context.

There are other complicating matters. For example, about half of all fertilized eggs are aborted spontaneously —that is, result in miscarriage—usually before the woman knows she is pregnant. Focus on the Family, an influential Christian ministry, is emphatic : “Human life begins at fertilization.” Does this mean that when a fertilized egg is spontaneously aborted, it is comparable—biologically, morally, ethically, or in any other way—to when a 2-year-old child dies? If not, why not? There’s also the matter of those who are pro-life and contend that abortion is the killing of an innocent human being but allow for exceptions in the case of rape or incest. That is an understandable impulse but I don’t think it’s a logically sustainable one.

The pro-choice side, for its part, seldom focuses on late-term abortions. Let’s grant that late-term abortions are very rare. But the question remains: Is there any point during gestation when pro-choice advocates would say “slow down” or “stop”—and if so, on what grounds? Or do they believe, in principle, that aborting a child up to the point of delivery is a defensible and justifiable act; that an abortion procedure is, ethically speaking, the same as removing an appendix? If not, are those who are pro-choice willing to say, as do most Americans, that the procedure gets more ethically problematic the further along in a pregnancy?

Read: When a right becomes a privilege

Plenty of people who consider themselves pro-choice have over the years put on their refrigerator door sonograms of the baby they are expecting. That tells us something. So does biology. The human embryo is a human organism, with the genetic makeup of a human being. “The argument, in which thoughtful people differ, is about the moral significance and hence the proper legal status of life in its early stages,” as the columnist George Will put it.

These are not “gotcha questions”; they are ones I have struggled with for as long as I’ve thought through where I stand on abortion, and I’ve tried to remain open to corrections in my thinking. I’m not comfortable with those who are unwilling to grant any concessions to the other side or acknowledge difficulties inherent in their own position. But I’m not comfortable with my own position, either—thinking about abortion taking place on a continuum, and troubled by abortions, particularly later in pregnancy, as the child develops.

The question I can’t answer is where the moral inflection point is, when the fetus starts to have claims of its own, including the right to life. Does it depend on fetal development? If so, what aspect of fetal development? Brain waves? Feeling pain? Dreaming? The development of the spine? Viability outside the womb? Something else? Any line I might draw seems to me entirely arbitrary and capricious.

Because of that, I consider myself pro-life, but with caveats. My inability to identify a clear demarcation point—when a fetus becomes a person—argues for erring on the side of protecting the unborn. But it’s a prudential judgment, hardly a certain one.

At the same time, even if one believes that the moral needle ought to lean in the direction of protecting the unborn from abortion, that doesn’t mean one should be indifferent to the enormous burden on the woman who is carrying the child and seeks an abortion, including women who discover that their unborn child has severe birth defects. Nor does it mean that all of us who are disturbed by abortion believe it is the equivalent of killing a child after birth. In this respect, my view is similar to that of some Jewish authorities , who hold that until delivery, a fetus is considered a part of the mother’s body, although it does possess certain characteristics of a person and has value. But an early-term abortion is not equivalent to killing a young child. (Many of those who hold this position base their views in part on Exodus 21, in which a miscarriage that results from men fighting and pushing a pregnant woman is punished by a fine, but the person responsible for the miscarriage is not tried for murder.)

“There is not the slightest recognition on either side that abortion might be at the limits of our empirical and moral knowledge,” the columnist Charles Krauthammer wrote in 1985. “The problem starts with an awesome mystery: the transformation of two soulless cells into a living human being. That leads to an insoluble empirical question: How and exactly when does that occur? On that, in turn, hangs the moral issue: What are the claims of the entity undergoing that transformation?”

That strikes me as right; with abortion, we’re dealing with an awesome mystery and insoluble empirical questions. Which means that rather than hurling invective at one another and caricaturing those with whom we disagree, we should try to understand their views, acknowledge our limitations, and even show a touch of grace and empathy. In this nation, riven and pulsating with hate, that’s not the direction the debate is most likely to take. But that doesn’t excuse us from trying.

Disability rights groups are fighting for abortion access — and against ableism

The conversation about abortion and other reproductive health care in the country is missing something: people with disabilities.

Since it became clear the Supreme Court would overturn Roe v. Wade , disability rights advocates say the uproar over allowing states to ban or restrict abortion has largely overlooked the ways people with disabilities will suffer. At least 12.7% of the U.S. population lives with disabilities — including from speech and limb differences, mobile disabilities and developmental disabilities — as of 2019, according to census data .

“I think one of the reasons that disabled people are not centered in these conversations, even though we should be, is that typically disabled people are de-sexualized,” said Maria Town, president and CEO of the American Association of People With Disabilities (AAPD). “We are not seen as sexual beings. In fact, the assumption is that we just don’t have sex when, in reality, disabled people do have sex. We need and deserve accessible, affordable reproductive and informed reproductive health care, and that includes abortion.”

Even after years of highlighting the longstanding lack of access to reproductive care, people with disabilities are still less likely to have health care providers and routine check-ups, and are more likely to have unmet health care needs because of the cost, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Access to reproductive services is even slimmer.

“You may need an additional support person for physical access or to provide mental health support,” said Town, who has cerebral palsy and uses mobility devices. “For states that have banned abortion and people are talking about needing to travel out of state or use telehealth services, many telehealth platforms are not accessible to people with disabilities. These are all barriers to health care. Accessibility of reproductive health care can be a huge challenge.”

People with disabilities are more likely to live in poverty than those without and often rely on state insurance programs like Medicaid to meet health care needs, according to the DC Abortion Fund , a nonprofit group that helps low-income people pay for abortions. However, only 15 states and Washington, D.C., cover abortions through Medicaid , a significant financial barrier to abortion access for people with disabilities.

For example, West Virginia, which has the largest population of disabled people in the country, according to census data, solely provides state funds for abortions in cases of life endangerment and fetal impairment. An analysis by the National Partnership for Women and Families found that abortion bans in the 26 states that are certain or likely to ban abortion could affect up to 2.8 million women with disabilities (53 percent of all such women in the U.S.).

Since the Supreme Court’s ruling, disability rights groups like the AAPD and the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund have condemned the Supreme Court’s action, detailing the myriad ways people with disabilities will be affected by the decision and calling out ableism in the national conversation about reproductive justice. Black people bear the brunt of this injustice. About 1 in 4 Black adults in the country have a disability, compared with 1 in 5 white Americans, according to the CDC . And about 36% of Black people with disabilities live in poverty, compared with 26% of America’s overall disabled population.

“Abortion advocates need to stop saying that the main reason to want abortion is to not have a disabled child,” disability rights advocate Imani Barbarin said. “There’s nothing like entering a space and the only reason they want access to this medical procedure is to not have somebody like you in their life. This is turning away tons of pro-abortion advocates who have disabilities.”

People with disabilities across the country have reported experiences with health care providers that left them feeling discriminated against and concerned about the quality of care they’d receive. In a study by the National Research Center for Parents with Disabilities , one doctor jokingly asked a woman with a physical disability if she “used a turkey baster” to get pregnant, another refused to touch a pregnant woman’s amputated leg to help her push during labor, and one nurse remarked to another woman that “it was wonderful that somebody like [her] would still want to have a kid.”

And the marginalized group fares no better when it comes to terminating a pregnancy. A New York woman recently told The New York Times that Planned Parenthood of Greater New York canceled her abortion appointment, telling her, “We don’t do procedures for people in a wheelchair.” (Planned Parenthood officials later apologized and said the woman’s appointment had been “mismanaged.”)

But the challenges of reproductive care don’t start at pregnancy, Town said people with disabilities experience unfair treatment from the time they are young.

“Procedures like pap smears are not inherently accessible to me,” Town said. “In the broader reproductive health care space, many disabled people are sterilized forcibly. And if they’re not sterilized, they’re placed on birth control or other forms of contraception without their consent. That happened to me as a young girl. Not for any health-related reasons, but so I was easier to care for.”

Stefanie Lyn Kaufman-Mthimkhulu, founder of the disability rights grassroots organization Project LETS, who is nonbinary and uses they and she pronouns, said they had an abortion in 2020 months after giving birth to a daughter. Kaufman-Mthimkhulu has Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome (CMS), a disorder that has an underlying defect in the transmission of signals from nerve cells to muscles. Kaufman-Mthimkhulu said they sometimes use a wheelchair. They also have autism and endure chronic pain in their ankle and spine as a result of multiple surgeries, they said.

As a result, their body had “negative reactions” to being pregnant and their pregnancy was labeled high risk as a result of their disabilities — “Pregnancy exacerbated my current pain and health issues, and created new issues. I was constantly in severe pain, and former tools like medical marijuana were no longer accessible to me,” Kaufman-Mthimkhulu said.

Research shows that people with disabilities get pregnant at similar rates to those without, but are more likely to experience blood clotting, hemorrhaging and infection during pregnancy, according to research published in the Disability and Health Journal . They also often receive inadequate health care and are at significantly higher risk of dying from pregnancy and childbirth, the research showed.

Kaufman-Mthimkhulu said in the wake of Roe being overturnedruling, Project LETS is working to develop political education sessions to both teach the public about the connection between reproductive and disability rights and strengthen mutual aid networks to support people with disabilities who need access to abortion, medication and other reproductive necessities. She said one key to fighting back against abortion restrictions for people with disabilities will be to strengthen systems that allow people with disabilities to give birth outside of traditional medical environments.

For instance, the organization is working with doulas and birth workers to create care networks for people outside of the traditional health care system, she said. This is important as people with disabilities navigate a system that doesn’t always tend to their needs. “Pregnancy put my physical body through hell, and mental, spiritual and emotional stability was significantly destabilized — to a point that I don’t believe has recovered.”

But harshly restricted access to care won’t be the only consequence of overturning Roe. Barbarin said organizations must prioritize making sure people with disabilities have access to their necessary medications moving forward.

“So many disabled people’s medications have ended because they’re abortifacients,” Barbarin said, referring to substances that induce abortion. “So people who are on certain lupus and cancer drugs have had them stopped immediately.”

One example of this is the drug Methotrexate, which is used to treat several types of cancer — like leukemia and lymphoma — and various diseases like lupus and Crohn’s disease. It is also an abortifacient , often used to treat ectopic pregnancies . The Lupus Foundation of America this month acknowledged reports of people having trouble accessing the drug since the Supreme Court ruling.

“We need not just people who are reproductive advocates, we need people who are medical advocates for people with disabilities. I really want people to understand that, if you want to talk about intersectionality, you need to get disabled people their meds.”

Barbarin, Town and Kaufman-Mthimkhulu agree that proper sex education is necessary for a future where people with disabilities have unlimited access to reproductive care. Up to 36 states don’t include the needs and challenges of youth with disabilities in their sex education requirements or provide resources for accessible sex education, according to a 2021 report from the nonprofit Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States . And of those that do, only three explicitly include the group in their sex education mandates.

As the nation gears up for life without federal abortion protection, disability rights groups are prioritizing community care, medication and education for people with disabilities. Even with all these efforts, they say, it’s important to move away from ableist rhetoric that only further marginalizes people with disabilities.

“Often times, disabled folks are used as scapegoats for pro-life arguments. Like, ‘Look at all of these babies labeled with prenatal abnormalities that are aborted!’” Kaufman-Mthimkhulu said.

“While it’s true that we must interrogate the ableism that leads to many disabled fetuses being aborted, disabled folks are not to be used as props to support harmful pro-life policies. We are not your pro-life scapegoats, and eugenics has no place in abortion access.”

CORRECTION (July 25, 2022, 10:57 a.m. ET) : A previous version of this article misstated the diagnosis of Stefanie Lyn Kaufman-Mthimkhulu. She has been diagnosed with Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome, not Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome.

Char Adams is a reporter for NBC BLK who writes about race.

Abortion as an Instrument of Eugenics

- Michael Stokes Paulsen

Response To:

- Race-ing Roe : Reproductive Justice, Racial Justice, and the Battle for Roe v. Wade by Melissa Murray

- See full issue

I. Throwing Down a Gauntlet

Professor Melissa Murray is right about one thing. Laws banning trait-selection abortion — prohibitions on abortion when had solely because of the race, sex, or specific disability of the child that otherwise would be born — pose a direct challenge to the Supreme Court’s constitutional abortion-law doctrine under Roe v. Wade 1 and Planned Parenthood v. Casey . 2 Such laws prohibit abortion based on a specific reason for having an abortion. And under current judicial doctrine, the state can’t do that: Roe and Casey held that a pregnant woman has a constitutional right to obtain an abortion; that that right may be exercised for essentially whatever reason the woman sees fit; and that the state may not make or enforce laws that have the purpose or effect of inhibiting the woman’s abortion choice. 3 The state may not forbid a reason — any reason at all — for which an abortion is committed or obtained.

There is a little more to it than that. But not much. The Court’s cases make the right to abortion plenary — explicitly so, pre-viability, and essentially so, as the result of a sweeping “health exception” even post-viability. 4 As a result, under Roe and Casey , abortion must be permitted as a matter of constitutional right, to be exercised for virtually any reason, throughout all nine months of pregnancy, right up to the point of live birth.

If Roe and Casey are right, then, abortion constitutionally must be allowed for any reason. This includes the race of the child to be born, the fact that she is a girl, or the fact that the child would be born with a disability. Under Roe and Casey , trait-selection abortion bans are “unconstitutional” (to accede for the moment to a familiar but improper use of the term). For the Court to uphold such bans would require it to repudiate, or greatly revise, the premises and substance of its current abortion-law doctrine. 5

Professor Murray is right about another, related thing: that that is at least part of the point of enacting such trait-selection abortion bans. Surely, part of the purpose of laws banning abortion when had for such eugenics reasons is to pose a more or less head-on challenge to the legal premises and deadly logic of Roe and Casey . If those decisions do indeed yield a constitutional right to kill Black human fetuses for being Black, girls for being girls, and the disabled for their disabilities, that result is truly monstrous and rightly discrediting. The ultimate goal of trait-selection bans is — probably just as Murray fears — to lay the groundwork for (or to attain straightaway) the overruling of Roe and Casey , by attacking their constitutional reasoning in a particularly sympathetic and persuasive context that lays bare where their logic leads.

Trait-selection bans throw down a gauntlet: Does the Constitution really confer a right to abortion when the sole reason is the race, or sex, or disability of the unborn human child? Is there a constitutional right to kill a living human fetus because he or she is a child of color, because he or she has Down syndrome, or because (in a perverse reversal of a traditional expression of joy) “it’s a girl!”?

If the answer to these questions is yes , Roe is perhaps revealed in new ways, to fresh eyes, for the legally radical, extremist decision its critics have long claimed it to be: Roe and Casey recognize a constitutional right to abortion even when had for eugenics purposes. And if the answer is no , the Court — eyes wide open, feet to the fire — might well feel compelled to reevaluate, revise, or even repudiate Roe .

At a simple doctrinal level, trait-selection bans thus present a square challenge to the Court’s abortion decisions. And at a deeper level, trait-selection bans tend to undermine both the legal and moral assumptions underlying the judicially created constitutional right to abortion in a unique way: they refute the “ it ”-ness of the human fetus. The unborn human fetus has human traits, qualities, capacities — in short, a distinctive human identity. Trait-selection abortion bans force fair-minded people (including judges) to confront and wrestle with the assumed “ it ”-ness of the human fetus in light of its — his or her — undeniable human characteristics. And that wrestling tends to produce a moral intuition: that the unborn human fetus is part of our common humanity. The moral intuition is a powerful one, uniting the otherwise sometimes differing moral instincts of the traditionalist right and the progressive and feminist left. 6

This is potentially game changing. If the intuition of the wrongness of trait-selection abortion has moral salience — the intuition that it is simply wrong to kill a fetus for reasons of race, sex, or disability — it is because of the implicit recognition of the humanity of the fetus. If killing a fetus because she is female (or Black, or disabled) is thought horrible, it can only be because the human fetus is thought to possess moral status as human — because “ it ” is a baby girl or a baby boy, a member of the human family. Constitutional law tends to follow moral intuitions. And the legal intuition that tends to follow from recognizing that the fetus has human characteristics — a distinctive, individual human identity — is that it should not be legal to kill a fetus on the basis of such human qualities. 7

This in turn can have further implications — producing something like an “aha!” moment: If it’s wrong to kill a girl because she is a girl, isn’t it wrong to kill a girl for some other reason? Isn’t the girl still a girl , irrespective of the reason for which an abortion is had? Whatever makes it intuitively wrong — and not a matter of constitutional entitlement — to kill a human fetus because of his or her race, sex, or disability strongly suggests that it is also wrong to kill that same human fetus for most other reasons. 8

Trait-selection abortion bans thus pose hugely important, stark, and seemingly unavoidable legal and moral challenges to the constitutional legal regime of Roe . These are the fundamental questions posed in the Box v. Planned Parenthood 9 case and that are discussed in Justice Clarence Thomas’s important concurrence in denial of certiorari in that case — the opinion that is the topic of Murray’s article. And yet these are the questions that Murray avoids entirely.

Instead, Murray trains her energies on a specific feature of Justice Thomas’s opinion — its discussion of race specifically as among eugenicist justifications for abortion. Thomas noted, as relevant background to modern efforts to ban abortion when had specifically for eugenics purposes, the disturbing history of racist and disability-eugenics arguments for abortion made in the (disturbingly recent) past. 10 Murray’s article proposes to “contextualize[]” 11 and provide a more “nuanced” 12 view of this historical evidence. Yet, as we shall see, much of Murray’s evidence supports Thomas’s conclusion. 13

Murray’s main point, however, is to criticize — to warn against — what she sees as the dangerous rhetorical and legal implications of Justice Thomas’s efforts to draw a connection between the abortion-rights legal regime and abortion-as-an-instrument-of-eugenics arguments and outcomes. Such an attempted connection, Murray argues, uses race to undermine Roe — a consequence she finds objectionable and dangerous. Moreover, she fears, racial justice arguments might supply the “special justification” needed to overrule prior precedent. 14 She believes that this is the project afoot in Thomas’s Box concurrence.

This Response offers a straightforward but harsh critique of Murray’s opus: it misses the point. For all of its analysis, Murray’s article simply fails to address the central legal questions posed by trait-selection abortion bans: Are they constitutional or not? Does the Roe right really embrace the freedom to kill a fetus because it is Black, female, or disabled? And if trait-selection bans are constitutional, why — and doesn’t the answer to that question deservedly undermine the legitimacy of Roe and Casey ?

This Response proceeds in three Parts.

Part II discusses Murray’s claim that Justice Thomas’s concurrence in Box v. Planned Parenthood is somehow misguided or mistaken in suggesting a historical relationship between abortion rights and racial eugenics arguments. (Murray gives far less attention to disability-based abortion and essentially none at all to sex-selection abortion.)

My contention is that Justice Thomas has it mostly right and that Murray’s critique falls wide of the mark. While abortion is not a eugenics conspiracy — a deliberate plot to reduce the size of the African American, female, or disabled populations — it remains an undeniable fact that the aborted are disproportionately racial minorities, female, and those with disabilities. 15 Abortion, in short, has a markedly disparate impact along lines of race, sex, and disability. This in itself is troubling, even if it is not proof of deliberate design — which Thomas never claims it is. Thomas does fairly highlight, however, the disturbing history of eugenics arguments for the desirability of liberalized abortion.

More to the point, it is undoubtedly the case that abortions are sometimes had, today, for eugenics reasons — fairly often, even, for sex-selection and disability-elimination. 16 In short, abortion is used as an instrument of eugenics. In some or many instances, this is the result of deliberately eugenic motivations of individuals exercising the abortion choice. In other instances, it is simply the incidental — though perhaps predictable — consequence of patterns of exercise of the abortion right due to other motivations.

Part III builds on this discussion to return to the critical substantive question: Where abortion is shown to be motivated by race, sex, or disability, may it constitutionally be prohibited on that ground? My position is that the constitutionally correct answer is yes and that this answer does indeed undermine Roe ’s and Casey ’s core legal premises, exactly as Murray worries. While trait-selection bans indeed conflict with current doctrine, I offer a road map as to how the Court nonetheless might sustain them — a route that inevitably would undermine or repudiate current doctrine in one or more important respects.

Part IV concludes with a word about stare decisis. As noted, Murray regrets Justice Thomas’s invocation of the racial-eugenics history of the right recognized in Roe because she fears that considerations of racial justice might provide the “special justification” she presumes is needed to warrant overruling Roe . The short answer (which I have developed elsewhere and will not rehearse at length in this essay) is that the premise is wrong: the doctrine of stare decisis — in the strong sense of deliberate adherence to a decision a court is otherwise fully persuaded is an erroneous, unfaithful interpretation of the Constitution — is simply incompatible with written constitutionalism. 17 Murray’s only mildly contrived theory of racial justice–necessitated exceptions to stare decisis — and her fear of its introduction into the abortion field — presumes the need for a special exception to an otherwise strict rule of stare decisis, entrenching Roe . That need does not exist. Moreover, even if one recognizes the force of precedent in constitutional cases as a general rule, most everyone agrees that decisions that are seriously wrong on enormously important questions can and should be overruled. That category certainly includes serious errors on racial justice matters. But it is not limited to such cases.

II. Abortion for Eugenics: Conspiracy or Simple Consequence?

How one answers the question whether abortion is a tool of racial, gender, or disability eugenics depends very much on how the question is asked. Is legalized abortion a eugenicist conspiracy — a deliberate plot on the part of those favoring abortion rights to reduce the number of people of a given race, sex, or disability? Surely not. At the very least, such motivations form no part of the modern argument for abortion rights. Does unrestricted legal abortion-choice produce a disparate impact resulting in disproportionate numbers of abortions ending the lives of minority, female, and disabled fetuses? Undeniably. The aborted are disproportionately Black, female, and disabled. Is the right to abortion sometimes used , by those exercising the abortion-choice, for eugenics purposes — specifically for the purpose of aborting on the basis of race, sex, or disability? Unquestionably. Some — but not all — of the abortion–disparate impact is attributable to intentional decisions to abort based on a trait of the baby that otherwise would be born.

These are three different questions. Justice Thomas’s concurrence in Box keeps them distinct. Murray’s article, in attempting to critique Thomas, tends to smush these separate questions together in a mildly confusing way.

Begin with Justice Thomas’s Box concurrence itself. Thomas’s opinion compiles an impressive and rightly disturbing narrative of evidence that family planning and abortion advocates in the past embraced the desirability of abortion as an instrument for achieving racial eugenics and for culling persons with disabilities from the population. (There appears to be no evidence that early abortion advocates ever favored abortion for gender -eugenics purposes — aborting girls because they are girls. 18 )

“Many eugenicists . . . supported legalizing abortion,” Justice Thomas writes, “and abortion advocates — including future Planned Parenthood President Alan Guttmacher — endorsed the use of abortion for eugenic reasons.” 19 Thomas notes how recent some of these eugenics-as-a-reason-for-abortion observations are, extending to the late 1960s and early 1970s. 20

But Justice Thomas stopped short of claiming that legal abortion is a racist plot to reduce the African American population — even while noting that some prominent African American leaders have so argued over the years. 21 Thomas’s point was narrower: Abortion “is an act rife with the potential for eugenic manipulation,” he wrote. 22 Moreover, “[t]he use of abortion to achieve eugenic goals is not merely hypothetical,” he observed, 23 with considerable history on his side. And more to the present-day point, “[t]echnological advances have only heightened the eugenic potential for abortion, as abortion can now be used to eliminate children with unwanted characteristics, such as a particular sex or disability.” 24 Thus, abortion is now capable of being used as “a disturbingly effective tool for implementing the discriminatory preferences that undergird eugenics.” 25

The right to abortion at one time had eugenicist proponents (among others). The right to abortion can be employed for eugenicist purposes (among others). Indiana’s trait-selection law was a response in part to this history and this reality. That is all Justice Thomas was saying.

Nothing in Murray’s article refutes Justice Thomas on these points. Murray demonstrates that, historically, different parties have acted from different motives and expressed different reasons for supporting abortion rights. This is an important but not a particularly surprising observation. It does not seriously impeach Thomas’s analysis. In fact, much of Murray’s historical discussion of race and abortion actually supports Thomas’s position. 26

Justice Thomas never claimed that abortion is a eugenicist conspiracy. Nor did Thomas claim that evidence of the disparate racial incidence of abortion proves a racially discriminatory purpose behind the abortion-rights position. Indeed, Thomas was careful to disclaim any such argument, maintaining consistency with his disparate-impact-does-not-establish-discriminatory-intent position in other discrimination law contexts. 27 Murray’s critique of Thomas here is badly off the mark. She charges Thomas with being “opportunistic and inconsistent” because — supposedly — “Justice Thomas had no trouble associating disproportionately high rates of abortion in the Black community with eugenics and the desire to limit Black reproduction” even though “he rejects the notion that racism is to blame for racially imbalanced outcomes.” 28 This simply misrepresents and mischaracterizes Thomas’s position, which is almost exactly the opposite of Murray’s characterization. 29

But what is one to make of the glaring evidence of a shockingly disparate impact of abortion? Even if abortion is not designed for eugenics purposes, it unquestionably has disproportionately eugenicist effects. The abortion right is not a racial, or gender, or disability classification, in terms. It does not depend on eugenicist intentions and is not the product of a eugenics conspiracy. But those possessing the abortion right exercise it in a fashion so as to abort more Black babies, more girls, and more “defective” children.

There is no blinking this reality. Consider race: The abortion rate is nearly three-and-a-half times higher among Black women than among white women. 30 (The abortion rate is 1.7 times higher for Hispanic women than it is for white women. 31 ) Black babies are aborted alarmingly more frequently than white babies — a point Justice Thomas made dramatically in his Box opinion. 32 This is almost certainly not attributable to a pattern of deliberate decisions to abort a child because of his or her race, but to socioeconomic factors. Some such factors may be statistically correlated with race, but that does not mean that such abortions are had because of the race of the child. (One suspects that few, if any, pregnancies are aborted specifically because the baby to be born is Black. 33 ) That does not alter the reality of a significant disparate racial impact to abortion, but it might suggest that something other than racism is the cause of racial disparities in abortion rates. 34

Consider sex: In 1990, Nobel Prize–winning Harvard economist Amartya Sen, in an arrestingly titled article, documented the statistical reality that, worldwide, More than 100 Million Women Are Missing 35 — a result, Sen argued, so far from the baseline norm expected in nature as to be statistically explainable only on the premise of some form of culpable human intervention, likely including severe medical neglect, deliberate female infanticide, and the predictable impact of China’s “one-child family” policy given a strong cultural preference for boys. 36 In 2011, journalist Mara Hvistendahl, in her book Unnatural Selection , reported that the number of missing (and presumed dead) women and girls in Asia alone had reached 160 million and counting. 37 This didn’t just happen. Hvistendahl convincingly demonstrates that the reason for the large demographic disparity in the male-female birth ratio is sex-selection abortion. 38 Women have abortions of female fetuses because the technology has become widely and inexpensively available to learn the sex of an unborn baby and then to kill her if she is a girl. As Justice Thomas’s Box opinion detailed, the United States is not exempt from the phenomenon of sex-selection abortion. 39 Unlike the situation of racial disparities in abortion, there is no way to explain the statistical reality of grossly disparate sex-differential birth rates, at least in some nations or among certain groups, other than by the hypothesis of abortions specifically being obtained because of the female sex of the child.

Consider disability: As Justice Thomas set forth in his Box concurrence, the abortion rate for children diagnosed with Down syndrome approaches 100% in Iceland, exceeds 90% in several other European nations, and is 67% in the United States. 40 There is no question but that this is the deliberate killing of children with a disability because of their disability.

Swallow hard and acknowledge the truth of what these numbers reveal, particularly for abortions predicated on sex or disability. Abortion is often employed for eugenics purposes — especially for sex selection and disability elimination. Abortion is used by women and men to kill girls because they are girls. Abortions are obtained in substantial numbers in order to cull the disabled, before birth, because they are disabled. And, while it seems unlikely that an abortion would be obtained specifically because the child is Black, the exercise of the right to legal abortion definitely has a racially disparate eugenic impact.

Is that not disturbing? Might it not supply a judicially recognized “compelling interest” qualifying, or overriding, the judicially fashioned constitutional right to abortion — the point of Justice Thomas’s opinion in Box ? Might it not rightly furnish a (further) critique of the validity of Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey and thereby serve to undermine these decisions’ legal and moral premises? Where race, sex, or disability can be shown to be the reason for a particular abortion, can such an abortion constitutionally be prohibited? Is the Court irrevocably committed to a doctrine that would compel toleration of eugenics-motivated abortion as a constitutional right? Or is there a sensible road back?

III. Thinking Outside the Box : A Roadmap for Upholding Trait-Selection Bans and Reforming Current Abortion Doctrine

As noted at the outset of this Response, laws prohibiting trait-selection abortion conflict in principle with Roe and Casey ’s establishment of a constitutional right to abortion for any reason the woman chooses. Is there nonetheless a plausible route for sustaining such prohibitions, even under current constitutional doctrine? I believe there is. But that route requires rereading Roe and Casey , limiting their holdings and narrowing their reasoning fairly substantially, and embracing premises that undermine the doctrinal foundations of those decisions at critical junctures. A thorough doctrinal analysis of these points would require an article of its own. 41 But the broad outlines of the argument can be sketched briskly.

First , rights have reasons . Even unwritten , judicially fashioned rights have reasons. For a right whose origins derive from common law–like judicial decisions rather than constitutional text, the rationale of judicial decisions in effect supply the relevant legal “text” and should permit subsequent common law–like adjustments to better conform rule to rationale. Where the formulation of a right — and especially of an unwritten right — outruns the reasons proffered for that right, there is good reason to limit or narrow it. Roe offers reasons for the abortion right. None of those reasons supports the extension of such a right to situations of deliberately eugenics-motivated abortion.

Central to the reasoning underlying the recognition of an abortion right in Roe was the premise, building on Eisenstadt v. Baird 42 the year before, that the decision “ whether to bear or beget a child ” is an aspect of the assumed constitutional “right of privacy.” 43 The implication, but by no means a clear one, is that what Roe seeks to protect is the decision whether to have a child at all . It is the freedom to be, or not to be, a parent. In the case of an abortion had solely because of the race, sex, or disability of the child that would be born, there is no interference with that choice. Rather, an abortion chosen for those reasons would implicate the different decision of whether to have a particular kind of child. To ban sex-selection (or race-motivated, or disability-based) abortion is not to interfere with the choice of whether or not to have a child — the right Roe and Casey seem to have in view — but to interfere with the choice to abort where continued pregnancy and childbirth otherwise would be chosen , but for reasons of the traits of the child to be born.

Similarly, Roe refers to “the distress, for all concerned, associated with the unwanted child.” 44 But, with trait-selection abortion bans, it is not the child that is unwanted; it is a child of a particular type that is “unwanted.” It is an unwanted girl . Or a child unwanted because of his race or disability. That is a materially different situation from the one contemplated in Roe .

The same point can be made with respect to “autonomy” or “bodily intrusion” or “burdens of pregnancy” or “physical constraints” arguments for the right to abortion, prominent in both Roe 45 id . (stating that “[t]he detriment that the State would impose upon the pregnant woman by denying this choice altogether is apparent” and listing medical and psychological burdens of pregnancy generally; the possible “distressful life and future” occasioned by “[m]aternity, or additional offspring;” the “distress, for all concerned, associated with the unwanted childhood;” and in some cases the “stigma of unwed motherhood”). and Casey . 46 Whatever the intrusions or burdens occasioned by pregnancy and childbirth, they are burdens that exist independently of the race, sex, or disability of the child. The very real burdens of pregnancy do not justify eugenics abortions specifically. In short, the right to abortion as formulated in Roe (and in Casey ) overshoots the reasons the Court offers in support of the right.

Second, the “undue burden” standard of Casey can be understood in a similar sense, as limited by the scope of what is thought the relevant right. Casey ’s holding was that the abortion right is violated, pre-viability, by any law that imposes an “undue burden” 47 on the right to choose abortion — that is, by any law that has the “purpose or effect” of placing a “substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus” so as to interfere with the “woman’s right to make the ultimate decision” as to whether or not to have any particular abortion. 48 Taken literally, this language would forbid trait-selection bans on the abortion choice. Such bans directly prohibit the ultimate decision, for abortions had for certain reasons. Such laws literally impose a direct legal obstacle to that particular abortion choice.

It seems fair to observe, however, that the “undue burden” formula is vague, amorphous, malleable, and adjustable. In a scheme of judicial development of an unwritten right, it should be open to the Court to conclude that prohibitions on trait-specific abortions do not burden in a relevant way the right to abortion itself , but only the right to trait selection of born children through the means of abortion. Such laws do not directly burden the decision to have an abortion, but only one reason for having an abortion. Just as employment antidiscrimination laws do not forbid hiring and firing, but only certain illegitimate reasons for a particular employment decision, trait-selection abortion bans do not “strike at the right [to abortion] itself.” 49 Thus, while Casey ’s specific doctrinal formulation would appear to preclude trait-selection bans, Casey does not appear to be all about the doctrine. More realistically, it is a case concerned with a supposed “balancing” of interests, as Roe also purported to be. Where that balance needs to be adjusted, the Court should adjust it. 50